Abstract

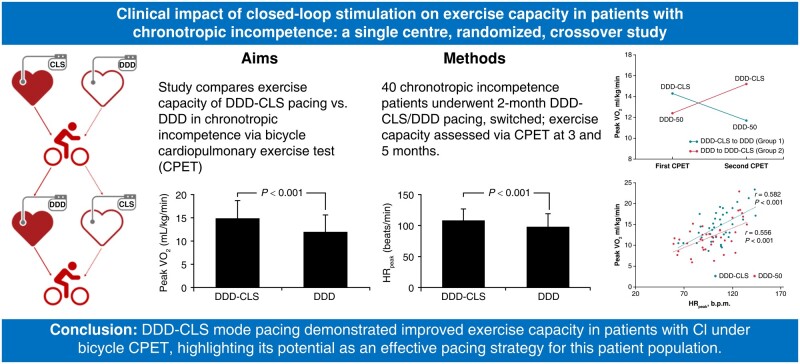

Aims

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of closed-loop stimulation (CLS) pacing compared with the traditional DDD mode in patients with chronotropic incompetence (CI) using bicycle-based cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET).

Methods and results

This single-centre, randomized crossover trial involved 40 patients with CI. Patients were randomized to receive either DDD-CLS or DDD mode pacing for 2 months, followed by a crossover to the alternative mode for an additional 2 months. Bicycling-based CPET was conducted at the 3- and 5-month follow-up visits to assess exercise capacity. Other cardiopulmonary exercise outcome measures and health-related quality of life (QoL) were also assessed. DDD-CLS mode pacing significantly improved exercise capacity, resulting in a peak oxygen uptake (14.8 ± 4.0 vs. 12.0 ± 3.6 mL/kg/min, P < 0.001) and oxygen uptake at the ventilatory threshold (10.0 ± 2.2 vs. 8.7 ± 1.8 mL/kg/min, P < 0.001) higher than those of the DDD mode. However, there were no significant differences in other cardiopulmonary exercise outcome measures such as ventilatory efficiency of carbon dioxide production slope, oxygen uptake efficiency slope, and end-tidal carbon dioxide between the two modes. Patients in the DDD-CLS group reported a better QoL, and 97.5% expressed a preference for the DDD-CLS mode.

Conclusion

DDD-CLS mode pacing demonstrated improved exercise capacity and QoL in patients with CI, highlighting its potential as an effective pacing strategy for this patient population.

Keywords: Chronotropic incompetence, Closed-loop stimulation, Cardiopulmonary exercise testing, Peak oxygen uptake, Exercise capacity

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

What’s new?

Modern pacemaker therapy employs rate-adaptive systems with accelerometer sensors to increase pacing rate based on thoracic motion but closed-loop stimulation (CLS) addresses limitations for activities like bicycling by monitoring ventricular contractility for more precise pacing rate adjustments.

The study conducted a comparison between DDD-CLS mode and DDD mode pacing in patients with chronotropic incompetence (CI) while performing bicycle-based cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET).

DDD-CLS mode pacing resulted in significantly higher peak oxygen uptake, peak heart rate at end of exercise, and oxygen uptake at the ventilatory threshold, indicating improved exercise capacity compared with the DDD mode in bicycle-based CPET.

Closed-loop stimulation pacing is particularly beneficial for activities like cycling where there is minimal thoracic motion, as patients who received DDD-CLS pacing reported improved quality of life (QoL) and a strong preference for this mode.

This study provides valuable insights into the development of more effective pacing strategies tailored to patients with CI to enhance their QoL and physical performance.

Introduction

Chronotropic incompetence (CI) refers to the impaired ability of the heart to increase its rate in response to physical activity or demand.1 Chronotropic incompetence leads to exercise intolerance and significantly affects the quality of life (QoL) of affected individuals. Moreover, it is an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular events and mortality.2

Modern pacemakers often use accelerometer-based rate-adaptive systems, increasing pacing rates with anterior-to-posterior thoracic motion.3,4 However, activities like bicycling, with limited thoracic movement, may not effectively engage the sensor despite inducing significant heart rate (HR) increases in healthy individuals. Closed-loop stimulation (CLS) addresses rate-adaptive pacing limitations in activities like bicycling with minimal thoracic motion. Closed-loop stimulation uses a comprehensive approach to monitor changes in ventricular contractility and adjusts the pacing rate accordingly and provides a more physiologically adaptive response by considering both exercise- and non-exercise-related factors such as postural changes, mental stress, and emotional arousal.5–8 However, the specific impact of CLS pacing on exercise capacity in patients with CI, particularly during cycling, remains unknown.

The expert consensus guidelines recommend considering pacing for patients with CI, but the available evidence is limited.9,10 The study aimed to fill this gap by investigating the effectiveness of CLS pacing compared with a control group without rate-adaptive pacing (DDD mode) in patients with CI, using bicycle-based cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET).11 This study focused on assessing changes in peak oxygen uptake (peak VO2) and ventilatory efficiency slope (VE/VCO2 slope) as indicators of exercise capacity during a cycling test, providing valuable insights into the benefits of CLS pacing in enhancing exercise capacity in patients with CI. Notably, this study may be the first to explore the effect of CLS on the exercise performance in patients with CI using CPET through a bicycle test, as no previous research on this topic has been published.

Methods

Study design

This study was a single-centre, single-blind, randomized crossover trial aimed at examining the effects of rate-adaptive atrial pacing using DDD-CLS in patients with CI. The study employed a randomized crossover design with two sequence options: DDD-CLS mode to DDD mode (without rate accelerated) or DDD mode to DDD-CLS mode, each implemented for a period of 2 months. Throughout the study, both patients and experts conducting symptom-limited bicycle-based CPET evaluations were blinded to the programmed mode used. The study received ethical approval from the relevant national and local ethics committees and adhered to good clinical practice guidelines and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital (reference number: 20190508D).

Consent

All participating patients provided written informed consent before their involvement in the study.

Patients

This study enrolled patients with Class I or II recommendations for dual-chamber pacing due to sinus node dysfunction with CI, with or without atrioventricular block, who were candidates for an implantable pulse generator (IPG). Two enrolled patients received intracardial defibrillator. The devices utilized in this study were Biotronik Evia DR, Eluna 8 DR-T, Enitra 8 DR-T, and Rivacor (Biotronik SE Co. KG, Berlin, Germany). A summary of these devices is provided in Supplementary material online, Table S1.

Patients who met the following criteria were excluded from the study: age <20 years, presence of permanent atrial fibrillation (AF), New York Heart Association Class IV heart failure, Stage V kidney dysfunction, indication for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), life expectancy <1 year, pregnancy or breastfeeding, AF ablation or other cardiac surgery within the past 3 months, inability to perform a bicycle test or any study procedure, or participation in another interventional trial. Patients who were taking β-blockers or other HR-slowing medications continued with their current dosages without any reduction or discontinuation.

Chronotropic incompetence

Upon patient enrolment, a comprehensive assessment of chronotropic function was performed using a treadmill exercise test. In accordance with criteria chosen based on previous studies, CI was defined as a maximum HR < 75% of the age-predicted maximum HR (APMHR = 220—age, applicable to healthy populations) during the exercise test.7,9,12 Patients who did not meet the criteria for CI were subsequently excluded from further participation in the study.

Study protocol

The study protocol is available in Supplementary material online, Figure S1. During the enrolment visit, chronotropic impairment was evaluated using a treadmill exercise test. The IPG device was programmed in DDD mode with a basic pacing rate of 50 pulses/min (DDD mode). The treadmill workload was started at 20 W and increased by 20 W every minute until the patient could no longer sustain running. Heart rate and maximum workload were recorded during the test.

Before randomization, the echocardiographic parameters were assessed as part of the baseline evaluation. At the baseline visit, which took place 1–4 weeks after enrolment, patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either the DDD-CLS or DDD mode. The assigned mode was maintained for 2 months, after which a crossover occurred, with patients switching to the alternative mode for another 2 months. This design allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of the effects of both pacing modes on patients with CI. At the 3- and 5-month follow-up visits, patients underwent bicycle-based CPET to evaluate their exercise capacity. Health-related QoL was assessed using the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire. These assessments were conducted to monitor changes in exercise performance and overall well-being over the course of the study period.

The study was terminated after a 6-month follow-up period. Before termination, each patient was asked to indicate the period during which they felt better in terms of well-being (the second or fourth month of follow-up). The corresponding pacing mode during the preferred period was then considered as the preferred mode by the patient.

Device programming

Following the implantation of the IPG, follow-up visits were scheduled at 1, 3, and 5 months after randomization. Once the diagnosis of CI was confirmed, the patients were randomly allocated to either the DDD without rate-adaptive mode or DDD-CLS rate-adaptive mode. The detailed settings of these two modes are listed in Supplementary material online, Table S2.

After IPG implantation, follow-up visits were scheduled 1, 3, and 5 months after randomization. After confirmation of CI, the patients were randomly assigned to either the DDD or DDD-CLS rate-adaptive mode. Three months after the initial randomization, the sensors were crossed over, indicating that patients who were initially in the DDD mode were switched to the DDD-CLS mode, and vice versa. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing with cycling was conducted at the 3- and 5-month follow-up visits. During these tests, patients were evaluated either DDD or DDD-CLS mode, depending on the specific time point in the study. These evaluations aimed to assess the exercise capacity of the patients and their response to the respective rate-adaptive pacing mode implemented at each follow-up visit.

At the end of the follow-up period, patients were allowed to choose their preferred sensors based on their personal experiences throughout the study. This allowed patients to express their individual preferences and select the sensor that they found to be most beneficial or comfortable based on their unique circumstances and feedback gathered during the study.

Evaluation of cardiopulmonary exercise testing and derived variables

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing was conducted using a spiroergometric system (Metalyzer 3 B, Cortex Biophysik, Leipzig, Germany) with a lower extremity ergometer during a bicycle test. A structured protocol was followed to evaluate the cardiovascular and pulmonary functions of each individual during exercise. More comprehensive insights can be found in the Supplementary material online. After obtaining informed consent and assessing the medical history of individuals, the equipment was set up, including a spiroergometric system for metabolic analysis and an electrocardiogram (ECG) for HR monitoring. The individual began the test by cycling on a stationary bicycle with a ramp protocol of 10 W/min and the spiroergometric system measured key parameters such as peak VO2, VO2 level at the ventilatory threshold (VO2 at VT), VE/VCO2 slope, oxygen uptake efficiency slope (OUES), pressure of end-tidal CO2 pressure (PET CO2), O2 pulse peak, peak respiratory exchange ratio (RER), and minute ventilation (VE). The system interfaced with the ECG monitor to continuously monitor the HR and rhythm. The exercise protocol typically involved incremental stages with increasing workload or resistance tailored to the fitness level and goals of an individual. Throughout the test, respiratory and metabolic data were recorded and analysed to provide real-time feedback on the physiological responses of individuals. Vital signs, ECG, Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE, 6–20), and symptoms were closely monitored, and the test was terminated, if necessary, based on predefined termination criteria. After the test, the data were analysed to determine parameters such as peak VO2, ventilatory efficiency, and anaerobic threshold. The CPET was conducted under the supervision of trained healthcare professionals (W.-L.C.) who were blinded to the pacing mode, ensuring accurate data acquisition and interpretation, and optimizing the diagnostic value of the test.

Outcome measures

The peak VO2 was the primary outcome. Secondary outcome measures included the VO2 at VT, VE/VCO2 slope, OUES, PET CO2, O2 pulse peak, peak RER, resting HR (HRrest), and peak HR (HRpeak) during bicycle-based CPET. Additional secondary outcome measures included the assessment of health-related QoL using the European Quality of Life 5-Dimensions 3-Level (EQ-5D-3L) questionnaire and the preferred pacing mode of patients.

Statistical methods

The study was designed to detect a 2.4% absolute reduction in the incidence of the primary endpoint over 6 months, with a power of 80% and a bilateral Type I error (alpha) of 0.05. Forty patients (20 per study arm) were enrolled, accounting for potential early dropouts, crossovers, and power loss due to interim analyses.

Descriptive statistics, such as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical data, were used to present the clinical and baseline characteristics of the patients. Complete data sets of peak VO2 were obtained from at least 40 patients.

For patients with complete data sets on peak VO2, all outcome measures were analysed by considering a crossover design. Means and standard deviations were reported for each randomization group and programmed mode as well as for within-group differences and the treatment effect of CLS on the outcome measure. The unpaired exact Wilcoxon test was used to analyse the treatment effect of CLS and assess the presence of carry-over or period effects.

Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, with statistical significance determined in an exploratory sense without adjusting for multiple testing. Data analysis was performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

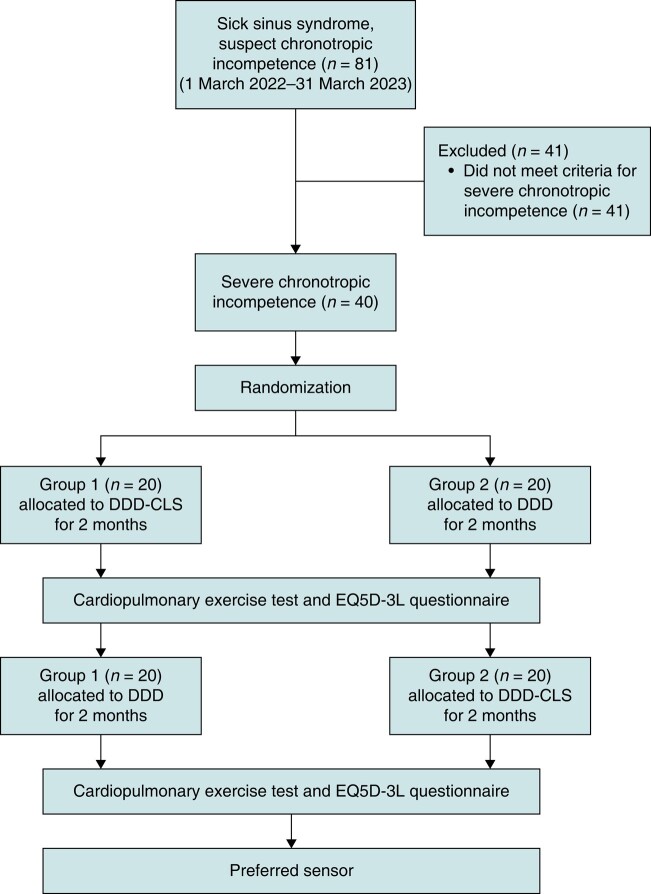

Between March 2019 and April 2023, the Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital performed IPG implantation for 81 patients diagnosed with sick sinus syndrome. After eliminating 41 patients who did not meet the criteria for CI, a final cohort of 40 patients (49%) was selected for the study. These patients were then randomly assigned to two groups. Group 1 underwent a transition from the DDD-CLS mode to the DDD mode, whereas Group 2 transitioned from the DDD mode to the DDD-CLS mode, as depicted in Figure 1. Tables 1 and 2 provide the baseline characteristics and treadmill exercise data at enrolment. The study was terminated in March 2023 after the last patient completed the follow-up period.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the trial process.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients

| All, n = 40 | Group 1 (DDD-CLS first), n = 20 | Group 2 (DDD first), n = 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72.2 ± 13.1 | 74.1 ± 7.6 | 70.2 ± 16.9 |

| Male gender | 14 (35.0) | 7 (35.0) | 7 (35.0) |

| Body height, cm | 159.3 ± 8.5 | 15.7 ± 9.2 | 161 ± 7.4 |

| Body weight, kg | 62.6 ± 10.8 | 60.7 ± 13.4 | 64.6 ± 7.4 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.6 ± 3.7 | 24.2 ± 4.1 | 25.0 ± 3.3 |

| Body fat, % | 33.1 ± 6.7 | 32.2 ± 5.8 | 33.9 ± 7.6 |

| Hypertension | 30 (75.0) | 17 (85.0) | 13 (65.0) |

| Diabetes | 10 (25.0) | 6 (30.0) | 4 (20.0) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 19 (47.5) | 11 (55.0) | 8 (40.0) |

| Coronary arteries disease | 15 (37.5) | 9 (45.0) | 6 (30.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 15 (37.5) | 9 (45.0) | 6 (30.0) |

| Echocardiographic parameter | |||

| LVEF (%) | 68.5 ± 8.8 | 69.4 ± 9.1 | 67.6 ± 8.6 |

| Left atrial diameter (mm) | 42.2 ± 6.4 | 42.8 ± 7.5 | 41.6 ± 5.1 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 47.8 ± 4.3 | 48.2 ± 3.5 | 47.5 ± 5.0 |

| LVESD (mm) | 29.3 ± 4.8 | 28.9 ± 4.4 | 29.7 ± 5.2 |

| Medication | |||

| ACEi or ARB | 27 (67.5) | 14 (70.0) | 13 (65.0) |

| Beta-blocker | 24 (60.0) | 9 (45.0) | 15 (75.0) |

| Dihydropyridine CCB | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.0) |

| MRA | 3 (7.5) | 2 (10.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Amiodarone | 5 (12.5) | 2 (10.0) | 3 (12.5) |

Data are shown as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockage; CCB, calcium channel blockers; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic diameter; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

Table 2.

Data of treadmill exercise test in randomized patients

| All patients, n = 40 | Group 1 (DDD-CLS first), n = 20 | Group 2 (DDD first), n = 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR at rest, b.p.m. | 67.0 ± 9.7 | 65.9 ± 9.0 | 68.3 ± 10.6 |

| HR at end of exercise, b.p.m. | 101.2 ± 14.1 | 100.6 ± 14.9 | 101.9 ± 13.8 |

| Maximum workload reached, METs | 4.2 ± 1.8 | 4.3 ± 1.6 | 4.1 ± 2.1 |

| %APMHR achieved | 68.4 ± 8.1 | 66.8 ± 7.5 | 70.1 ± 8.7 |

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation.

APMHR, age-predicted maximum heart rate; HR, heart rate; MET, metabolic equivalent of task.

Assessment of peak VO2 and other cardiopulmonary exercise outcome measures

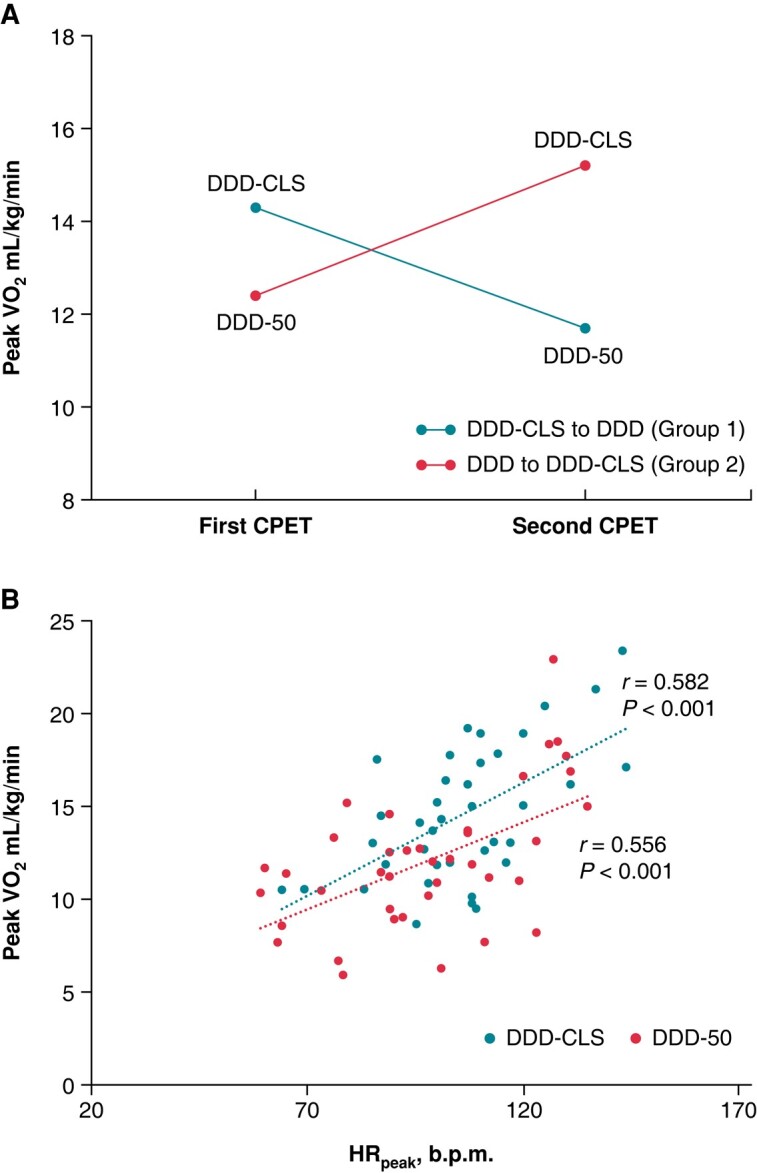

Forty patients were included in the CPET analysis (Figure 1). The difference in peak VO2 between patients with the DDD-CLS and DDD modes was 2.7 ± 1.7 mL/kg/min or 0.9 ± 0.6 METs, indicating a tendency towards improved peak VO2 with the CLS mode (Figure 2A and Table 3). Peak VO2 had a significant positive correlation with maximum HR (HRpeak) at the end of the exercise for patients with the DDD-CLS (r = 0.582, P < 0.001) and DDD modes (r = 0.556, P < 0.001), as depicted in Figure 2B. Peak VO2 values were found to be higher for patients with the DDD-CLS mode (14.8 ± 4.0 mL/kg/min or 4.5 ± 1.2 METs) than for those with the DDD mode (12.0 ± 3.6 mL/kg/min or 3.6 ± 1.1 METs) with a significant difference (P < 0.001, Table 4). Additionally, VO2 at VT was significantly higher in patients with the DDD-CLS mode (10.0 ± 2.2 mL/kg/min) than in those with the DDD mode (8.7 ± 1.8 mL/kg/min) (P < 0.001). Moreover, the double product (18 193.7 ± 5155.5 vs. 16 480.1 ± 5302.4 mmHg b.p.m., P < 0.001) and maximal workload (68.0 ± 21.9 vs. 59.8 ± 21.9 W, P < 0.001) were also notably higher in the DDD-CLS group compared with the DDD group. Parameters such as the VE/VCO2 slope, OUES, PET CO2, and O2 pulse peak did not show significant differences between the two groups. Concurrently, the peak RER (1.07 ± 0.06 vs. 1.05 ± 0.07, P = 0.02) and HRpeak (107.5 ± 19.8 vs. 97.6 ± 21.6 b.p.m., P = 0.02) were significantly improved in patients in the DDD-CLS mode compared with those in the DDD mode. These findings collectively suggest enhanced exercise capacity in patients with CI when using the DDD-CLS mode.

Figure 2.

Exercise capacity and heart rate correlation analysis. (A) Peak VO2 results are presented for the two groups. Higher values are indicative of better performance. (B) The correlation between peak VO2 and peak HR (HRpeak) is displayed. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) is provided to quantify the strength of the correlation. HRpeak, peak heart rate.

Table 3.

Values derived from cardiopulmonary exercise and change in DDD-CLS and DDD mode

| DDD-CLS mode | DDD mode | Change in DDD-CLS | Total change in DDD-CLS (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak VO2, mL/kg/min | ||||

| Group 1 | 14.3 ± 3.9 | 11.7 ± 3.6 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 2.7 ± 1.7, P < 0.001 |

| Group 2 | 15.2 ± 4.2 | 12.4 ± 3.7 | 2.9 ± 2.0 | |

| Peak VO2, METs | ||||

| Group 1 | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.6, P < 0.001 |

| Group 2 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | |

| VO2 at VT, mL/kg/min | ||||

| Group 1 | 9.7 ± 1.9 | 8.8 ± 1.8 | 0.9 ± 1.5 | 1.2 ± 1.9, P < 0.001 |

| Group 2 | 10.2 ± 2.5 | 8.7 ± 1.8 | 1.5 ± 2.2 | |

| VE/VCO2 slope | ||||

| Group 1 | 31.9 ± 5.6 | 33.2 ± 5.3 | −1.3 ± 6.8 | −0.6 ± 7.5, P = 0.63 |

| Group 2 | 31.4 ± 6.7 | 31.3 ± 5.6 | 0.1 ± 8.3 | |

| OUES, mL/min | ||||

| Group 1 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | −0.1 ± 0.6 | 0.03 ± 0.51, P = 0.3 |

| Group 2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | |

| PET CO2, mmHg | ||||

| Group 1 | 36.5 ± 4.4 | 36.4 ± 5.2 | 0.1 ± 2.8 | 0.8 ± 2.9, P = 0.1 |

| Group 2 | 39.2 ± 9.8 | 37.7 ± 3.9 | 1.5 ± 2.9 | |

| O2 pulse peak, mL | ||||

| Group 1 | 8.8 ± 2.2 | 8.4 ± 2.9 | 0.7 ± 2.2 | 0.65 ± 1.97, P = 0.1 |

| Group 2 | 9.2 ± 2.0 | 8.6 ± 2.5 | 0.6 ± 2.5 | |

| Peak RER | ||||

| Group 1 | 1.06 ± 0.06 | 1.05 ± 0.08 | 0.02 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.06, P = 0.02 |

| Group 2 | 1.08 ± 0.06 | 1.05 ± 0.06 | 0.03 ± 0.05 | |

| HRrest, b.p.m. | ||||

| Group 1 | 75.4 ± 11.7 | 73.5 ± 13.2 | 3.4 ± 12.1 | 3.7 ± 14.5, P = 0.1 |

| Group 2 | 72.3 ± 12.6 | 68.5 ± 11.5 | 3.9 ± 16.7 | |

| HRpeak, b.p.m. | ||||

| Group 1 | 108.9 ± 24.1 | 100.7 ± 21.9 | 8.2 ± 17.9 | 9.9 ± 18.3, P = 0.02 |

| Group 2 | 106.1 ± 14.8 | 94.6 ± 21.5 | 11.5 ± 19.0 | |

| Double product, mmHg × b.p.m. | ||||

| Group 1 | 19 023.6 ± 5771.8 | 16 498.2 ± 5702.5 | 2525.4 ± 3386.5 | 2433.1 ± 4054.2, P = 0.001 |

| Group 2 | 18 803.8 ± 4606.4 | 16 462.9 ± 5019.1 | 2340 ± 4717.2 | |

| Maximal workload, W | ||||

| Group 1 | 65.7 ± 24.0 | 54.0 ± 25.0 | 10.2 ± 27.2 | 7.6 ± 20.0, P = 0.02 |

| Group 2 | 70.4 ± 19.8 | 65.0 ± 17.4 | 5.0 ± 9.2 | |

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Group 1, DDD-CLS first, n = 20; Group 2, DDD first, n = 20.

CLS, closed-loop stimulation; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test; PET CO2, end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure; HRpeak, peak HR; HRrest, resting heart rate; OUES, oxygen uptake efficiency slope; Peak VO2, maximum oxygen uptake; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; VE/VO2, ventilatory efficiency; VO2 at VT, VO2 level at the ventilatory threshold.

Table 4.

Values derived from cardiopulmonary exercise and change in DDD-CLS mode and DDD mode

| DDD-CLS mode | DDD mode | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak VO2, mL/kg/min | 14.8 ± 4.0 | 12.0 ± 3.6 | <0.001 |

| Peak VO2, METs | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| VO2 at VT, mL/kg/min | 10.0 ± 2.2 | 8.7 ± 1.8 | <0.001 |

| VE/VCO2 slope | 31.7 ± 6.1 | 32.2 ± 5.5 | 0.63 |

| OUES, mL/min | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.3 |

| PET CO2, mmHg | 37.8 ± 4.2 | 37.1 ± 4.6 | 0.1 |

| O2 pulse peak, mL | 9.0 ± 2.1 | 8.5 ± 2.6 | 0.1 |

| Peak RER | 1.07 ± 0.06 | 1.05 ± 0.07 | 0.02 |

| HRrest, b.p.m. | 73.8 ± 12.1 | 70.9 ± 12.5 | 0.1 |

| HRpeak, b.p.m. | 107.5 ± 19.8 | 97.6 ± 21.6 | 0.02 |

| Double product, mmHg b.p.m. | 18 193.7 ± 5155.5 | 16 480.1 ± 5302.4 | <0.001 |

| Maximal workload, W | 68.0 ± 21.9 | 59.8 ± 21.9 | 0.02 |

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation.

CLS, closed-loop stimulation; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test; PET CO2, end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure; HR, heart rate; OUES, oxygen uptake efficiency slope; Peak VO2, maximum oxygen uptake; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; VE/VO2, ventilatory efficiency; VO2 at VT, VO2 level at the ventilatory threshold.

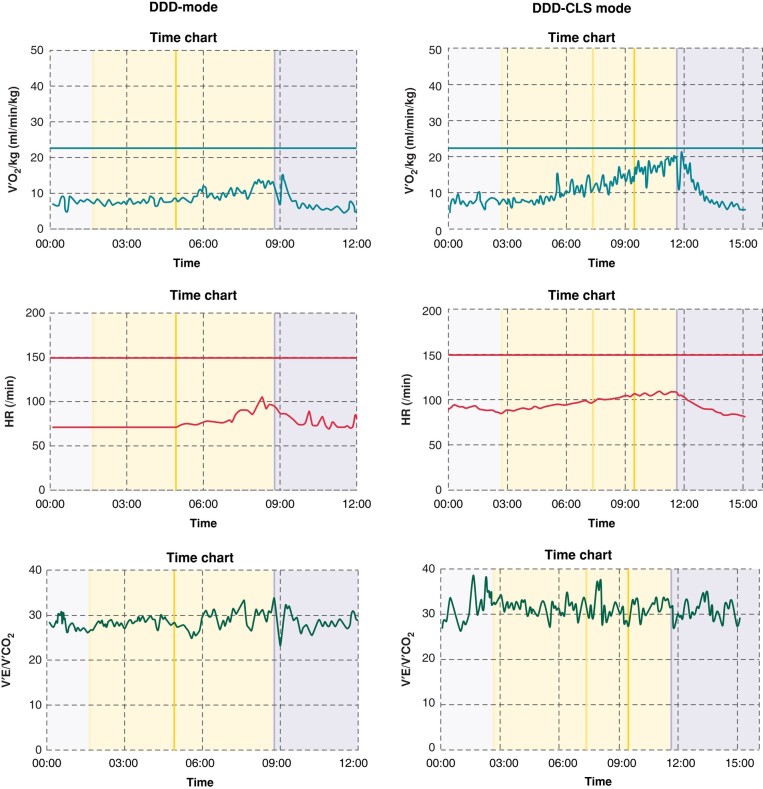

Figure 3 presents the exercise performance of an individual under both DDD and DDD-CLS modes. It highlights peak VO2 values of 12.72 mg/kg/min for DDD mode and 19.18 mg/kg/min for DDD-CLS mode, peak HRs of 96 b.p.m. for DDD mode and 107 b.p.m. for DDD-CLS mode, as well as VE/VCO2 slopes of 34.4 for DDD mode and 33.5 for DDD-CLS mode.

Figure 3.

Individual exercise performance comparison under DDD and DDD-CLS modes. This figure presents the data of 1 individual among the 40 study patients, showcasing the exercise performance under both DDD (dual-chamber pacing) and DDD-CLS (closed-loop stimulation) modes.

Other assessments and observations

The study compared the effects of settings between DDD-CLS and DDD on the QoL. The results from the EQ-5D-3L indicated a more favourable trend in the activity-related items for DDD-CLS, particularly in the aspect of mobility, where 85% of DDD-CLS patients reported better mobility compared with 66% in the DDD group (P < 0.05), reaching statistical significance (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2). Furthermore, the assessment of the visual scale in the EQ-5D-3L revealed that DDD-CLS also outperformed DDD in terms of overall QoL (73.5 ± 9.8 vs. 69.3 ± 12.0, P = 0.03). Throughout the study, only one case of non-cardiogenic mortality was reported, and no other serious adverse events were observed. At the end of the study, 39 of 40 patients (97.5%) expressed a preference for the DDD-CLS mode.

Discussion

Enhanced exercise capacity with closed-loop stimulation in patients with chronotropic incompetence

The capacity to engage in physical activity significantly impacts the QoL of an individual, as it involves an increase in VO2.1 In healthy individuals, maximal aerobic exercise leads to a roughly four-fold increase in VO2. This is achieved through a 2.2-fold increase in HR, a 0.3-fold increase in stroke volume, and a 1.5-fold increase in arteriovenous oxygen difference.13 The increase in HR plays a crucial role in sustaining aerobic exercise. However, patients with CI experience an impaired HR response during exercise, leading to severe exercise intolerance.14 Our study revealed that the DDD-CLS mode effectively up-regulated ∼10% of the maximal HR compared with the DDD mode in patients with CI, resulting in a significant improvement in exercise performance, with peak VO2 increasing by ∼20%, VO2 at VT increasing by 2%, and RER increasing by 10%. The effects of the DDD-CLS mode on peak VO2 yielded positive outcomes in patients with CI. Additionally, there was a significant improvement in health-related QoL in patients with DDD-CLS, supported by the fact that more than 95% of the study patients preferred the DDD-CLS mode after the completion of the study. These findings demonstrate the beneficial impact of the DDD-CLS mode on both the physical performance and overall well-being of individuals with CI, highlighting its potential as an effective therapeutic approach to enhance the QoL.

Closed-loop stimulation activation and VE/VCO2 slope in patients with chronotropic incompetence

In our study, patients with CI undergoing DDD-CLS mode rate adaptation showed significant improvement in peak VO2 but no significant enhancement in VE/VCO2, OUES, or PET CO2 when compared with the DDD mode. This could be attributed to the inclusion of patients with good left ventricular systolic function. Previous studies in heart failure patients undergoing CRT and CI have shown that the CLS mode can improve VE/VCO2 and the QoL.7,15,16 Notably, patients with CRT with improved ejection fraction were more likely to respond positively to CLS-based rate-adaptive pacing, whereas those with reduced ejection fraction were less likely to respond.7,16

In contrast, a recent study by Reddy et al.17 using treadmill-based CPET in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and CI demonstrated that accelerometer-based rate-adaptive atrial pacing aimed at enhancing exercise HR did not result in improvements in exercise capacity or symptoms. The lack of improvement in cardiac output was attributed to inadequate time for relaxation during shorter diastolic periods as HR increased, despite the increase in exercise HR with pacing. This suggests that an increase in HR alone may not be the sole determining factor for improving exercise capacity during CPET in patients with HFpEF and CI. Other factors such as diastolic function and ventricular relaxation may play a critical role in influencing exercise performance in this particular patient population. In a study by Coenen et al.5 utilizing the 6 min walking test, it was observed that CLS resulted in a slightly lower exercise HR compared with the accelerometer sensor; however, both sensors showed similar distances covered during the walk. This suggests that CLS may be able to identify patients who rely less on higher exercise HR for adequate cardiac output. In contrast, the accelerometer was shown to increase the HR similarly in all study patients, despite some requiring less chronotropic support.5 These findings collectively offer valuable insights into the advantages of CLS-based rate-adaptive pacing and its impact on exercise capacity and cardiovascular function in specific patient populations.

Clinical implications

The present study focus on CPET assessment during cycling highlights the practicality and relevance of CLS in real-world scenarios, particularly in patients with CI. Our findings demonstrate that CLS effectively regulates HR during cycling, offering a promising solution for this patient population. Given the global popularity of cycling, our research underscores the potential impact of CLS in meeting the specific demands of patients with CI engaging in this form of physical activity.

Limitations

This study emphasized the positive impact of DDD-CLS pacing on exercise capacity but did not compare it with traditional DDDR pacing mode relying on thoracic movement. Future research could explore differences and benefits between these approaches in individuals engaging in bicycle-based exercise, providing a potential avenue for further investigation.

The study observed small benefit of DDD-CLS mode over DDD mode in certain parameters and the limited symptomatic improvement. The achieved HR of 107.5 ± 19.8 b.p.m. in the DDD-CLS mode falls short of the anticipated target. This discrepancy is indeed attributed to the predefined fixed programming of CLS parameters in the present study. A tailored programming might have been more effective in reaching the desired goal.

Conclusions

The present study suggests that activating the CLS may improve exercise capacity in patients with CI, as indicated by the higher peak VO2 during bicycle-based CPET. Patients also preferred the DDD-CLS mode, suggesting its potential benefits in improving their QoL. Nevertheless, the use of CLS-based rate-adaptive pacing shows promise, particularly during activities like cycling in patients with CI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr Hsien-Chun Wang, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, Taiwan, for his contribution in the study.

Contributor Information

Su-Kiat Chua, School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Fu Jen Catholic University, 510 Zhongzheng Road, Xinzhuang District, New Taipei City 24205, Taiwan; Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Wen-Ling Chen, School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Fu Jen Catholic University, 510 Zhongzheng Road, Xinzhuang District, New Taipei City 24205, Taiwan; Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Lung-Ching Chen, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Kou-Gi Shyu, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Huei-Fong Hung, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Shih-Huang Lee, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Tzu-Lin Wang, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Wei-Ting Lai, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Kuan-Jen Chen, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Zhen-Yu Liao, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Cheng-Yen Chuang, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Ching-Yao Chou, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, No. 95, Wen Chang Road, Shih-Lin District, Taipei 11101, Taiwan.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Funding

This study was supported by Biotronik SE & Co. KG (Woermannkehre 1, Berlin, Germany).

Data availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supplementary material files.

References

- 1. Brubaker PH, Kitzman DW. Chronotropic incompetence: causes, consequences, and management. Circulation 2011;123:1010–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ho PM, Maddox TM, Ross C, Rumsfeld JS, Magid DJ. Impaired chronotropic response to exercise stress testing in patients with diabetes predicts future cardiovascular events. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1531–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leung SK, Lau CP. Developments in sensor-driven pacing. Cardiol Clin 2000;18:113–55, ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Candinas R, Jakob M, Buckingham TA, Mattmann H, Amann FW. Vibration, acceleration, gravitation, and movement: activity controlled rate adaptive pacing during treadmill exercise testing and daily life activities. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1997;20:1777–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coenen M, Malinowski K, Spitzer W, Schuchert A, Schmitz D, Anelli-Monti M et al. Closed loop stimulation and accelerometer-based rate adaptation: results of the PROVIDE study. Europace 2008;10:327–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Palmisano P, Zaccaria M, Luzzi G, Nacci F, Anaclerio M, Favale S. Closed-loop cardiac pacing vs. conventional dual-chamber pacing with specialized sensing and pacing algorithms for syncope prevention in patients with refractory vasovagal syncope: results of a long-term follow-up. Europace 2012;14:1038–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Proff J, Merkely B, Papp R, Lenz C, Nordbeck P, Butter C et al. Impact of closed loop stimulation on prognostic cardiopulmonary variables in patients with chronic heart failure and severe chronotropic incompetence: a pilot, randomized, crossover study. Europace 2021;23:1777–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Proietti R, Manzoni G, Di Biase L, Castelnuovo G, Lombardi L, Fundaro C et al. Closed loop stimulation is effective in improving heart rate and blood pressure response to mental stress: report of a single-chamber pacemaker study in patients with chronotropic incompetent atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2012;35:990–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, Michowitz Y, Auricchio A, Barbash IM et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3427–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Writing Committee Members; Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Barrett C, Edgerton JR, Ellenbogen KA et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm 2019;16:e128–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guazzi M, Arena R, Halle M, Piepoli MF, Myers J, Lavie CJ. 2016 focused update: clinical recommendations for cardiopulmonary exercise testing data assessment in specific patient populations. Eur Heart J 2018;39:1144–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dobre D, Zannad F, Keteyian SJ, Stevens SR, Rossignol P, Kitzman DW et al. Association between resting heart rate, chronotropic index, and long-term outcomes in patients with heart failure receiving beta-blocker therapy: data from the HF-ACTION trial. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2271–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higginbotham MB, Morris KG, Williams RS, McHale PA, Coleman RE, Cobb FR. Regulation of stroke volume during submaximal and maximal upright exercise in normal man. Circ Res 1986;58:281–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Higginbotham MB, Morris KG, Williams RS, Coleman RE, Cobb FR. Physiologic basis for the age-related decline in aerobic work capacity. Am J Cardiol 1986;57:1374–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hsu JC, Darden D, Alegre M, Birgersdotter-Green U, Feld GK, Hoffmayer KS et al. Effect of closed loop stimulation versus accelerometer on outcomes with cardiac resynchronization therapy: the CLASS trial. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2021;61:479–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Proff J, Merkely B, Papp R, Lenz C, Nordbeck P, Butter C et al. Closed loop stimulation in patients with chronic heart failure and severe chronotropic incompetence: responders versus non-responders. Int J Cardiol 2023;370:222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reddy YNV, Koepp KE, Carter R, Win S, Jain CC, Olson TP et al. Rate-adaptive atrial pacing for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the RAPID-HF randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2023;329:801–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supplementary material files.