Abstract

Background

People with advanced kidney disease treated with dialysis experience mortality rates from cardiovascular disease that are substantially higher than for the general population. Studies that have assessed the benefits of statins (HMG CoA reductase inhibitors) report conflicting conclusions for people on dialysis and existing meta‐analyses have not had sufficient power to determine whether the effects of statins vary with severity of kidney disease. Recently, additional data for the effects of statins in dialysis patients have become available. This is an update of a review first published in 2004 and last updated in 2009.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of statin use in adults who require dialysis (haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Renal Group's Specialised Register to 29 February 2012 through contact with the Trials' Search Co‐ordinator using search terms relevant to this review.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that compared the effects of statins with placebo, no treatment, standard care or other statins on mortality, cardiovascular events and treatment‐related toxicity in adults treated with dialysis were sought for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Two or more authors independently extracted data and assessed study risk of bias. Treatment effects were summarised using a random‐effects model and subgroup analyses were conducted to explore sources of heterogeneity. Treatment effects were expressed as mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes and risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes together with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

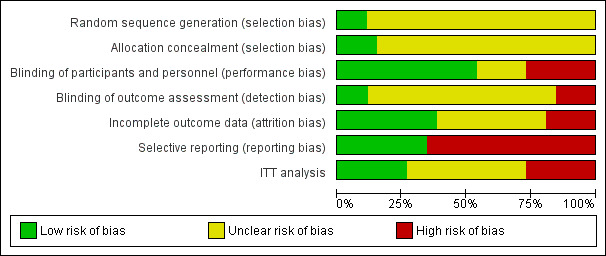

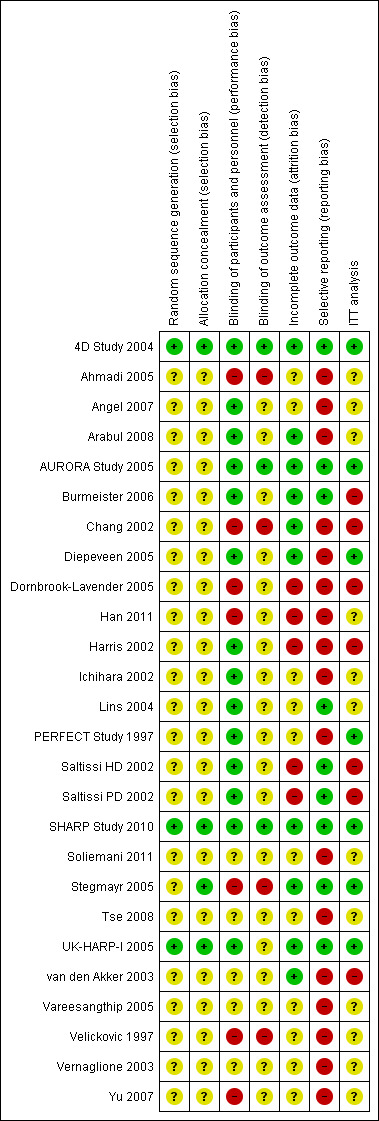

The risk of bias was high in many of the included studies. Random sequence generation and allocation concealment was reported in three (12%) and four studies (16%), respectively. Participants and personnel were blinded in 13 studies (52%), and outcome assessors were blinded in five studies (20%). Complete outcome reporting occurred in nine studies (36%). Adverse events were only reported in nine studies (36%); 11 studies (44%) reported industry funding.

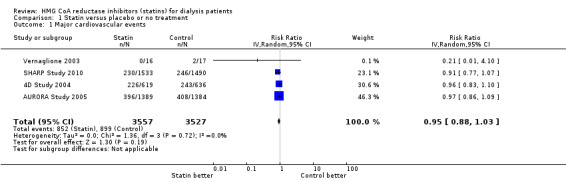

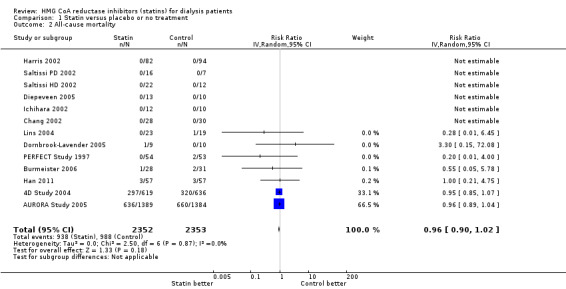

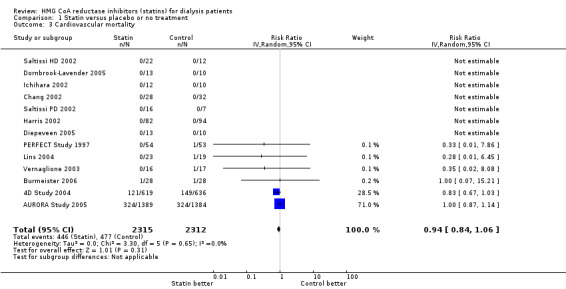

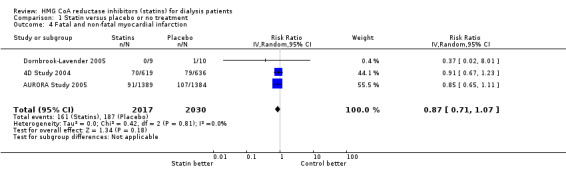

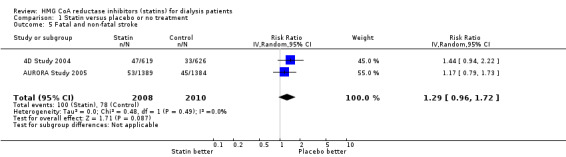

We included 25 studies (8289 participants) in this latest update; 23 studies (24 comparisons, 8166 participants) compared statins with placebo or no treatment, and two studies (123 participants) compared statins directly with one or more other statins. Statins had little or no effect on major cardiovascular events (4 studies, 7084 participants: RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.03), all‐cause mortality (13 studies, 4705 participants: RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.02), cardiovascular mortality (13 studies, 4627 participants: RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.06) and myocardial infarction (3 studies, 4047 participants: RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.07); and uncertain effects on stroke (2 studies, 4018 participants: RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.72).

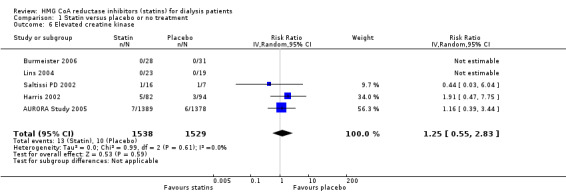

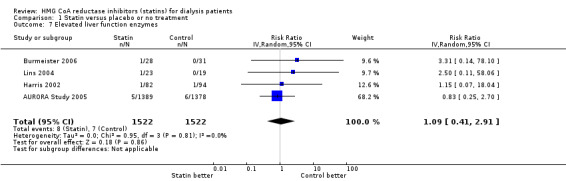

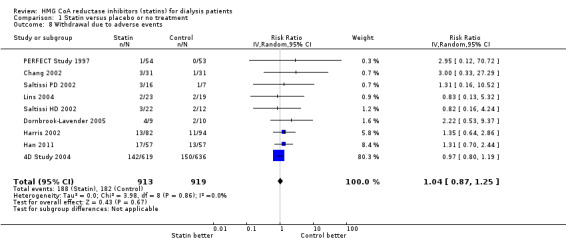

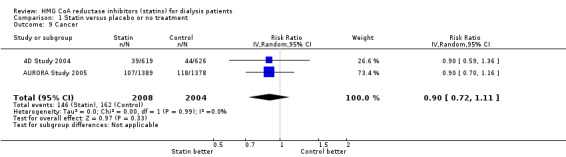

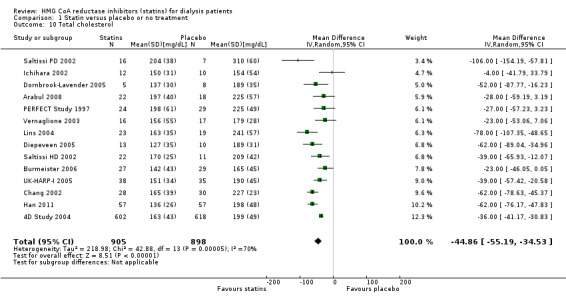

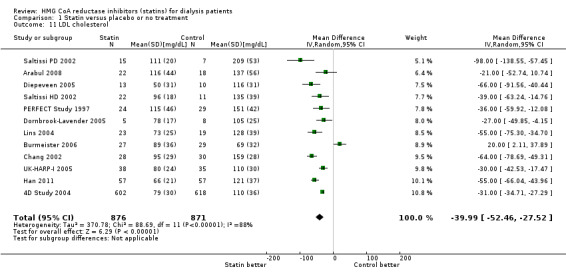

Risks of adverse events from statin therapy were uncertain; these included effects on elevated creatine kinase (5 studies, 3067 participants: RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.55 to 2.83) or liver function enzymes (4 studies, 3044 participants; RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.25), withdrawal due to adverse events (9 studies, 1832 participants: RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.25) or cancer (2 studies, 4012 participants: RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.11). Statins reduced total serum cholesterol (14 studies, 1803 participants; MD ‐44.86 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐55.19 to ‐34.53) and low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (12 studies, 1747 participants: MD ‐39.99 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐52.46 to ‐27.52) levels. Data comparing statin therapy directly with another statin were sparse.

Authors' conclusions

Statins have little or no beneficial effects on mortality or cardiovascular events and uncertain adverse effects in adults treated with dialysis despite clinically relevant reductions in serum cholesterol levels.

Plain language summary

Does statin therapy improve survival or reduce risk of heart disease in people on dialysis?

Adults with severe kidney disease who are treated with dialysis have high risks of developing heart disease. Statin treatment reduces risks of death and complications of heart disease in the general population.

In 2009 we identified 14 studies, enrolling 2086 patients, and found that while statins were generally safe and reduced cholesterol levels, they did not prevent death or clinical cardiac events in people treated with dialysis. This latest update analysed a total or 25 studies (8289 patients), and included the results from two new large studies. We found that statins lowered cholesterol in people treated with dialysis but did not prevent death, heart attack, or stroke.

Evidence for side‐effects was incomplete, and potential harms from statin therapy remain uncertain. Current study data did not address whether statin treatment should be stopped when a person starts dialysis, although the benefits associated with continued treatment are likely to be small. Limited information was available for people treated with peritoneal dialysis, suggesting that more research is needed in this setting.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Statin versus placebo or no treatment for dialysis patients | |||||

|

Patient or population: adults with chronic kidney disease Settings: dialysis Intervention: statin therapy Comparison: placebo or no treatment | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk/year/1000 treated | Corresponding risk/year/1000 treated | ||||

| Placebo or no treatment | Statin | ||||

| Major cardiovascular events | 150 per 1000 | 143 per 1000 (7 fewer) (132 to 155) (18 fewer to 5 more) | RR 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | 7804 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| All‐cause mortality | 200 per 1000 | 192 per 1000 (8 fewer) (176 to 208) (24 fewer to 8 more) | RR 0.96 (0.90 to 1.02) | 4705 (13) | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 100 per 1000 | 94 per 1000 (6 fewer) (82 to 105) (18 fewer to 5 more) | RR 0.94 (0.84 to 1.06) | 4627 (13) | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | |||||

Absolute approximate events rates of outcomes per year were derived from previously observational cohort studies. Absolute numbers of people on dialysis with cardiovascular or mortality events avoided or incurred per 1000 treated were estimated using these assumed risks together with the estimated relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (Herzog 1998; Trivedi 2009; Weiner 2006; Wetmore 2009)

Background

Description of the condition

Although cardiovascular mortality is decreasing, events among dialysis patients remains 20‐ to 30‐times higher than for the general population (Foley 2007; Herzog 2011; USRDS 2011). Elevated circulating lipid levels is one of several factors, that also include hypertension, diabetes, and smoking, that have been implicated in the increased cardiovascular risk associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Ganesh 2001; Jungers 1997; Mallamaci 2002).

How the intervention might work

Clinical studies conducted in the general population, and in people with established cardiovascular disease, have found a strong, consistent and independent association between lipid lowering, primarily low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and the risk of all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality (Law 1994; Rossouw 1990). A linear proportional reduction in the risk of major vascular events equal to approximately 20% per 1 mmol/L (39 mg/dL) reduction in LDL cholesterol has been reported (Baigent 2005). Optimal lowering of serum lipid levels has been anticipated to lower cardiovascular and overall mortality for people treated with dialysis.

Why it is important to do this review

Study data for the benefits of lipid lowering in people on dialysis are increasingly conflicted. Our previous review (Navaneethan 2009a) identified little or no benefit from statin therapy on mortality, although one study reported fewer major cardiovascular events in people with diabetes on dialysis (4D Study 2004). The Study for Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP Study 2010, completed since our last review update), which included 3023 people on dialysis, reported that benefits for lipid‐lowering therapy extended to people with advanced kidney disease on dialysis, whereas the AURORA Study 2005 (A Study to Evaluate the Use of Rosuvastatin in Subjects on Regular Hemodialysis: An Assessment of Survival and Cardiovascular Events) conducted with 2776 adults on haemodialysis, found no clear benefit for statin therapy in this population. An advisory committee to the US Food and Drug Administration that considered SHARP Study 2010 study data did not recommend lipid‐lowering using simvastatin/ezetimibe in people on dialysis, citing insufficient evidence (FDA 2011).

In light of conflicting information on the benefits of statin therapy to inform clinical practice and policy in people on dialysis, together with new study data, we conducted an update of our earlier review (Navaneethan 2009a) to evaluate the benefits and harms of statin therapy in people on dialysis.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits (reductions in all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, major cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction and stroke) and harms (liver or muscle damage, or cancer) of statins compared with placebo, no treatment, or another statin in adults who require dialysis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCT) and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable method) of at least 8 weeks' duration that evaluated the benefits and harms of statins in adults treated with haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis were included. The first periods of randomised cross‐over studies were also included. Studies of fewer than eight weeks' duration were excluded because they were unlikely to enable detection of mortality or cardiovascular outcomes related to statin therapy (Briel 2006).

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Adults treated with dialysis (haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis) irrespective of pre‐existing cardiovascular disease or statin therapy were included.

Exclusion criteria

Studies in children were excluded. Studies including adults with CKD not treated with dialysis and recipients of a kidney transplant are the subject of other related reviews (Navaneethan 2009b; Navaneethan 2009c; updates in press (Palmer 2013a; Palmer 2013b)).

Types of interventions

We included studies that compared statins with placebo, no treatment or standard care, or another statin. We excluded studies that compared a statin with a second non‐statin regimen, including fibrate therapy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Major cardiovascular events

All‐cause mortality

Cardiovascular mortality

Fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction

Fatal and non‐fatal stroke

-

Adverse events attributable to interventions

Elevated creatine kinase

Elevated liver function enzymes

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Cancer.

Secondary outcomes

Lipid parameters (mg/dL)

-

Serum lipid levels

Total cholesterol

LDL cholesterol

Triglycerides

High‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

2013 update

We searched the Cochrane Renal Group's Specialised Register to 29 February 2012 through contact with the Trials' Search Co‐ordinator using search terms relevant to this review.

The Cochrane Renal Group’s Specialised Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of renal‐related journals and the proceedings of major renal conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected renal journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of the Cochrane Renal Group. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts are available in the Specialised Register section of information about the Cochrane Renal Group.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of relevant clinical practice guidelines, review articles and studies.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete RCTs to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently screened all abstracts retrieved by electronic searches to identify potentially relevant citations for detailed study in full text format. Studies that might have included relevant data or information on studies involving HMG Co‐A reductase inhibitors were retained initially. Studies published in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment for inclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two authors independently extracted data from the eligible studies using standard data extraction forms. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was included. Any further information required from the original author was requested and any relevant information obtained was included in the review. Disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third author.

Data entry was carried out by the same two authors. Treatment effects were summarised using the random‐effects model but the fixed effects model was also analysed to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers. For dichotomous outcomes (cardiovascular events, mortality, and adverse events) treatment effects were summarised as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used (lipid parameters), treatment effects were summarised using the mean difference (MD).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011; Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study (detection bias)?

Participants and personnel

Outcome assessors

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcomes (e.g. fatal and non‐fatal heart attack and stroke) were expressed as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Risk differences (RD) with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for adverse effects. Continuous outcomes were calculated as mean differences (MD) with 95% CI.

Dealing with missing data

Where applicable, study authors were contacted for further information or missing data. Data obtained in this manner were included in our analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi² test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I² test (Higgins 2003). I² values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

This update included all studies identified in the Cochrane Renal Group's Specialised Register, which is updated regularly with published and unpublished reports identified in congress proceedings. This reduces the risk of publication bias. All reports of a single study were reviewed to ensure that all outcomes were reported to reduce the risk of selection bias.

Data synthesis

We summarised evidence quality together with absolute treatment effects for mortality and cardiovascular events based on estimated baseline risks using Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines (Table 1; Guyatt 2008). Absolute numbers of people on dialysis with cardiovascular events or adverse events avoided or incurred were estimated using the risk estimate for the outcome (and associated 95% confidence interval) obtained from the corresponding meta‐analysis together with the absolute population risk estimated from previously published observational studies (Herzog 1998; Trivedi 2009; Weiner 2006; Wetmore 2009).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses to explore potential sources of heterogeneity in modifying estimates of the effects of statins in the studies. We planned subgroup analyses according to participant type, intervention, or study‐related characteristics, when subgroups contained four or more independent studies: dialysis type (peritoneal or haemodialysis); statin type; statin dose (equivalent to simvastatin); baseline cholesterol (< 230 mg/dL versus ≥ 230 mg/dL); age (≤ 55 years versus > 56 years); proportion with diabetes (> 20% versus < 20%); adequacy of allocation concealment. Insufficient numbers of studies reporting one or more events were available to explore for publication bias using visual inspection of an inverted funnel plot or formal statistical analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

Where a study's results differed considerably from other studies in a meta‐analysis, exclusion of the study was investigated to determine whether this altered the result of the meta‐analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Initial review (2004) and first update (2009)

The searches identified 88 reports in 2004 and 115 reports in 2009. After title and abstract screening 67 (2004) and 97 (2009) reports were excluded. Full text assessment resulted in six studies (7 reports, 357 participants) included in our initial 2004 review and 14 studies (32 reports, 2086 participants) included in the 2009 update. Two studies reported as ongoing in 2004 and 2009 (AURORA Study 2005; SHARP Study 2010) have been included in our 2013 update.

2013 review update

Electronic searching to February 2012 identified 71 additional records. Of these, 33 were duplicate reports of existing studies and four were ongoing studies. After full‐text assessment, a study by Joy 2008 included in our 2009 review update was considered to be a part of Dornbrook‐Lavender 2005. We also removed Fiorini 1994 because it did not evaluate a statin versus another statin, placebo, or no treatment; and Dogra 2007, because treatment duration was only six weeks. This meant that 11 unique studies were retained from the 2009 published review (Navaneethan 2009a).

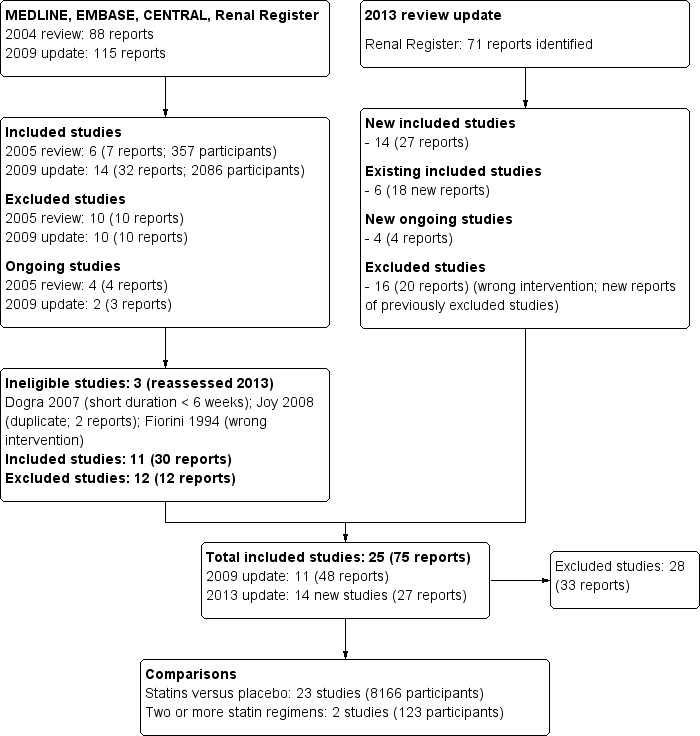

After detailed assessment of the remaining reports, 25 studies (14 new eligible studies) were identified. The flow chart for the review process is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study selection flow diagram

Included studies

This review included 25 studies that involved 8289 participants. One study included relevant subsets of haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patient data and for purpose of the analyses have been identified as Saltissi HD 2002 and Saltissi PD 2002 respectively.

There were 14 new studies included in this update (Ahmadi 2005; Angel 2007; Arabul 2008; AURORA Study 2005; Burmeister 2006; Han 2011; SHARP Study 2010; Soliemani 2011; Tse 2008; van den Akker 2003; Vareesangthip 2005; Velickovic 1997; Vernaglione 2003; Yu 2007). Of these, two (AURORA Study 2005; SHARP Study 2010) were identified as ongoing studies in our 2009 review.

There were 23 studies (8166 participants) that compared statins with placebo or no treatment (4D Study 2004; Ahmadi 2005; Angel 2007; Arabul 2008; AURORA Study 2005; Burmeister 2006; Chang 2002; Diepeveen 2005; Dornbrook‐Lavender 2005; Han 2011; Harris 2002; Ichihara 2002; Lins 2004; PERFECT Study 1997; Saltissi HD 2002‐Saltissi PD 2002; SHARP Study 2010; Stegmayr 2005; Tse 2008; UK‐HARP‐I 2005; Vareesangthip 2005; Velickovic 1997; Vernaglione 2003;Yu 2007), and two (123 participants) directly compared two or more statins (Soliemani 2011; van den Akker 2003).

Study design

All included studies were RCTs; two were two‐by‐two factorial design with aspirin (UK‐HARP‐I 2005) and enalapril (PERFECT Study 1997).

Participants

All participants were undergoing dialysis.

Twelve studies only included participants undergoing haemodialysis (4D Study 2004; Ahmadi 2005; AURORA Study 2005; Burmeister 2006; Chang 2002; Dornbrook‐Lavender 2005; Ichihara 2002; Lins 2004; Soliemani 2011; UK‐HARP‐I 2005; Vareesangthip 2005; Vernaglione 2003);

Eight studies included participants treated with either haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis (Arabul 2008; Diepeveen 2005; UK‐HARP‐I 2005; PERFECT Study 1997; Saltissi HD 2002‐Saltissi PD 2002; SHARP Study 2010; Stegmayr 2005; Yu 2007)

Five studies only included peritoneal dialysis patients (Angel 2007; Harris 2002; Han 2011; Tse 2008; Velickovic 1997).

Median baseline serum LDL cholesterol was 190 mg/dL (range 150 to 254 mg/dL).

Two studies only included participants with diabetes at baseline (4D Study 2004; Ichihara 2002).

Interventions

Five studies reported follow‐up of more than six months (4D Study 2004; AURORA Study 2005; SHARP Study 2010; Stegmayr 2005; UK‐HARP‐I 2005). Generally, studies were small (median 42 participants; range 13 to 3023 participants); three studies enrolled more than 1000 participants undergoing dialysis (4D Study 2004; AURORA Study 2005; SHARP Study 2010).

Doses of statin (equivalent to simvastatin) were generally 20 mg (5 to 80 mg) with a median follow‐up of six months (2 to 59 months) including studies reporting mortality and cardiovascular events. Non‐randomised co‐interventions included diet in three comparisons (Ichihara 2002; Saltissi HD 2002; Saltissi PD 2002).

Excluded studies

We excluded 28 studies: 13 were not randomised; seven did not include an appropriate intervention (other active treatment); one was a discontinued study; five were short durations (< 8 weeks); two were not conducted in dialysis populations (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias in included studies is summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The risk of bias was high in many of the included studies. Random sequence generation and allocation concealment was reported in three (12%) and four studies (16%), respectively. Participants and personnel were blinded in 13 studies (52%), and outcome assessors were blinded in five studies (20%). Complete outcome reporting occurred in nine studies (36%). Adverse events were only reported in nine studies (36%); 11 studies (44%) reported industry funding.The risk of bias was high in many included studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Random sequence generation was only reported in 3/25 studies (4D Study 2004; SHARP Study 2010; UK‐HARP‐I 2005).

Allocation concealment

Allocation to randomised groups was not reported adequately: only 4/25 included studies reported allocation methodology in detail (4D Study 2004; SHARP Study 2010; Stegmayr 2005; UK‐HARP‐I 2005).

Blinding

Blinding methodology was well reported: 13 provided adequate details (4D Study 2004; Angel 2007; Arabul 2008; AURORA Study 2005; Burmeister 2006; Diepeveen 2005; Harris 2002; Ichihara 2002; Lins 2004; PERFECT Study 1997; Saltissi HD 2002‐Saltissi PD 2002; SHARP Study 2010; UK‐HARP‐I 2005); six did not indicate blinding (Han 2011; SHARP Study 2010; Tse 2008; van den Akker 2003; Vareesangthip 2005; Vernaglione 2003); and six did not blind participants (Ahmadi 2005; Chang 2002; Dornbrook‐Lavender 2005; Stegmayr 2005; Velickovic 1997; Yu 2007).

Incomplete outcome data

Drop‐outs and losses to follow‐up ranged for 0% to 32%. Seven studies were judged to be at low risk of bias (4D Study 2004; Arabul 2008; AURORA Study 2005; Diepeveen 2005; SHARP Study 2010; Stegmayr 2005; UK‐HARP‐I 2005), six were at high risk (Burmeister 2006; Chang 2002; Dornbrook‐Lavender 2005; Harris 2002; Saltissi HD 2002‐Saltissi PD 2002; van den Akker 2003), and the remaining 12 studies were unclear.

Selective reporting

Overall, nine studies (36%) reported all expected outcomes (4D Study 2004; Arabul 2008; AURORA Study 2005; Burmeister 2006; Lins 2004; Saltissi HD 2002‐Saltissi PD 2002; SHARP Study 2010; Stegmayr 2005; UK‐HARP‐I 2005).

Other potential sources of bias

Eleven studies (44%) reported industry funding (4D Study 2004; AURORA Study 2005; Burmeister 2006; Chang 2002; Diepeveen 2005; Dornbrook‐Lavender 2005; Lins 2004; PERFECT Study 1997; Saltissi HD 2002‐Saltissi PD 2002; SHARP Study 2010; UK‐HARP‐I 2005)

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Statins versus placebo or no treatment

We found moderate‐to‐high quality evidence to indicate that statin therapy had little or no effect on risks of major cardiovascular events (Analysis 1.1 (4 studies, 7084 participants): RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.03), all‐cause mortality (Analysis 1.2 (13 studies, 4705 participants): RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.02) and cardiovascular mortality (Analysis 1.3 (13 studies, 4627 participants): RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.06) (Table 1). Statins had little or no effect on risks of fatal or non‐fatal myocardial infarction (Analysis 1.4 (3 studies, 4047 participants): RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.07) and had uncertain effects on fatal or non‐fatal stroke (Analysis 1.5 (2 studies, 4018 participants): RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.72). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in these analyses (I² = 0%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 Major cardiovascular events.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 Cardiovascular mortality.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 Fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 5 Fatal and non‐fatal stroke.

Statins had uncertain effects on adverse events, including elevation of creatine kinase (Analysis 1.6 (5 studies, 3067 participants): RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.55 to 2.83), elevated liver enzymes (Analysis 1.7 (4 studies, 3044 participants): RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.41 to 2.91), withdrawal due to adverse events (Analysis 1.8 (9 studies, 1832 participants): RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.25) and cancer (Analysis 1.9 (2 studies, 4012 participants): RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.11) (Table 1). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in these analyses (I² = 0%).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 6 Elevated creatine kinase.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 7 Elevated liver function enzymes.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 8 Withdrawal due to adverse events.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 9 Cancer.

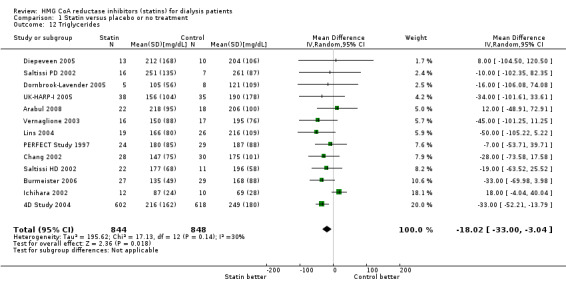

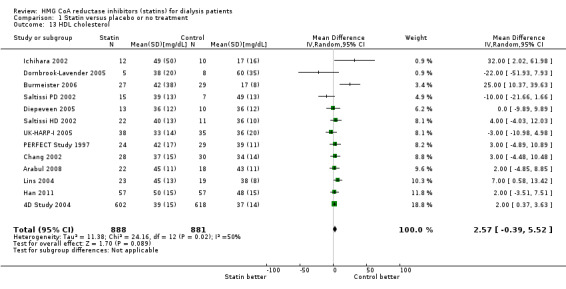

Statins significantly reduced total cholesterol (Analysis 1.10 (14 studies, 1803 participants): MD ‐44.86 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐55.19 to ‐34.53), LDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.11 (12 studies, 1747 participants): MD ‐39.99 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐52.46 to ‐27.52) and triglycerides (Analysis 1.12 (13 studies, 1692 participants): MD ‐18.02 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐33.00 to ‐3.04), but had uncertain effects on HDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.13 (13 studies, 1769 participants): MD 2.57 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.39 to 5.52).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 10 Total cholesterol.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 11 LDL cholesterol.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 12 Triglycerides.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Statin versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 13 HDL cholesterol.

Analysis of heterogeneity

We did not identify any sources of heterogeneity in the analyses for total or LDL cholesterol using prespecified subgroup analyses (dialysis type or statin type or dose, age, proportion with diabetes, baseline serum cholesterol, risk of bias (allocation concealment)). The lack of specific populations with or without cardiovascular disease at baseline in the available studies prevented subgroup analysis for the effect of statins by the presence or absence of cardiovascular disease.

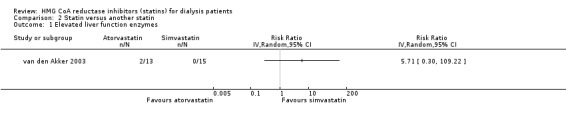

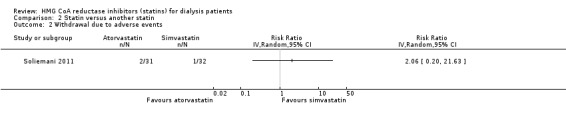

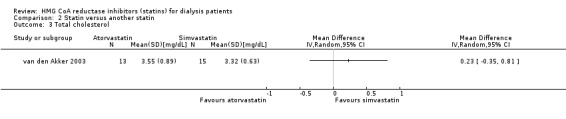

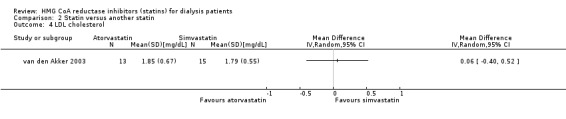

Statin versus other statin

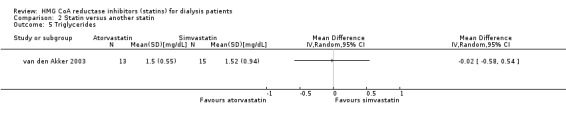

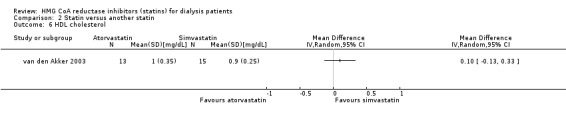

van den Akker 2003 (28 participants) compared atorvastatin (10 to 40 mg/d) with simvastatin (10 to 40 mg/d), and Soliemani 2011 compared atorvastatin, simvastatin and lovastatin directly (95 participants). Compared to simvastatin, atorvastatin treatment had uncertain effects on elevation of liver enzymes (Analysis 2.1 (1 study, 28 participants): RR 5.71, 95% CI 0.30 to 109.22), withdrawal from treatment due to adverse events (Analysis 2.2 (1 study, 63 participants): RR 2.06, 95% CI 0.20 to 21.63), total cholesterol (Analysis 2.3 (1 study, 28 participants): MD 0.23 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.81), LDL cholesterol (Analysis 2.4 (1 study, 28 participants): MD 0.06 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.52), triglycerides (Analysis 2.5 ((1 study, 28 participants): MD ‐0.02 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.58 to 0.54), and HDL cholesterol (Analysis 2.6 (1 study, 28 participants): 0.10 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.33). Data for other outcomes were not available in extractable format.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Statin versus another statin, Outcome 1 Elevated liver function enzymes.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Statin versus another statin, Outcome 2 Withdrawal due to adverse events.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Statin versus another statin, Outcome 3 Total cholesterol.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Statin versus another statin, Outcome 4 LDL cholesterol.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Statin versus another statin, Outcome 5 Triglycerides.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Statin versus another statin, Outcome 6 HDL cholesterol.

Sensitivity analyses

When analyses were restricted to studies in which follow‐up data were provided for six months or more, the results were unchanged (major cardiovascular events, unchanged from primary result; all‐cause mortality (7 studies, 4328 participants): RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.02) (4D Study 2004; AURORA Study 2005; Ichihara 2002; Han 2011; PERFECT Study 1997; Saltissi HD 2002‐Saltissi PD 2002); cardiovascular mortality ((7 studies, 4247 participants): RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.06) (4D Study 2004; AURORA Study 2005; Ichihara 2002; Han 2011; PERFECT Study 1997; Saltissi HD 2002‐Saltissi PD 2002).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review update on the benefits and harms of statins in people treated with dialysis found that data for mortality and cardiovascular events were generally moderate‐to‐high quality. Statin therapy (generally at doses equivalent to 20 mg of simvastatin) reduced total serum cholesterol levels by 46 mg/dL (1.2 mmol/L) in adult dialysis patients, but had little or no effect on major cardiovascular events or mortality. Statins were found to have little or no effect on myocardial infarction and uncertain effects on the risk of stroke. Statins were also found to have uncertain effects on risks of liver dysfunction, muscle damage or cancer in people on dialysis; and toxicity data were limited by a lack of systematic reporting in half the studies. Few data were available for people treated with peritoneal dialysis. Direct head‐to‐head studies of different statin agents were rare and estimated effects of atorvastatin versus simvastatin were imprecise.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Three large and well‐conducted studies provided moderate‐to‐high quality data that showed consistent effects of statins on cardiovascular events in people treated with dialysis (4D Study 2004; AURORA Study 2005; SHARP Study 2010). Mortality data were assessed as moderate quality because information from SHARP Study 2010 could not be included as these were not reported in the published study separately for dialysis patients and could not be obtained from the authors on request.

The strengths of this review include consistent results for primary outcomes among studies (no evidence of heterogeneity), comprehensive systematic searching for eligible studies, rigid inclusion criteria for RCTs, and data extraction and analysis by two independent investigators. Furthermore, the possibility of publication bias was minimised by including both published and unpublished studies (such as abstracts from meetings), although we could not formally test for evidence of publication bias or small study effects due to the small numbers of available studies.

Despite comprehensive inclusion of available studies, the current evidence for statins in people treated with dialysis has some significant limitations. Studies were generally small (median number of participants was 42) and, with the exception of three large well‐conducted studies (4D Study 2004; AURORA Study 2005; SHARP Study 2010), were assessed to be at high risk of bias. Studies were also generally of short duration (six months) and may not have been sufficiently powered to identify the effects of statins on clinical end points such as mortality (Briel 2006) (although the larger studies that dominated analyses provided outcome data for three to five years of treatment).

Limited data were available for adverse events, which were not systematically captured in over half of the included studies, such that potential toxicities of statins in this population remain incompletely characterised. We were unable to determine whether treatment effects were different in people on peritoneal dialysis compared with those on haemodialysis. Eight studies enrolled both haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients and only one presented separate outcome data for these two populations (Saltissi HD 2002‐Saltissi PD 2002). In addition, the small number of available studies meant that we were unable to explore other sources of heterogeneity in the treatment effects among studies on serum cholesterol levels, although this was a secondary (and surrogate) outcome. We could not identify whether treatment effects differed between men and women. Furthermore, we were unable to analyse the relative benefits of primary versus secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in people on dialysis, because there were too few studies specifically designed to address this question. SHARP Study 2010 evaluated a combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe, but it remains unclear whether there was an important difference in treatment effects compared with a statin alone, although it is unlikely because treatment effects were consistent among all studies for major cardiovascular events irrespective of the treatment used.

It was noteworthy that adverse mortality and cardiovascular events were not clearly prevented by statins in the dialysis population, despite clinically significant lowering of serum lipid levels. This finding is inconsistent with data from people with earlier stages of kidney disease not treated with dialysis, for which statins clearly reduce risks of death and major cardiovascular events (Palmer 2013a). It was possible that a lack of power in available studies for dialysis resulted in the small or no effects on all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular events, although the inclusion of nearly 2000 events in each analysis makes this unlikely. It has previously been suggested that the choice of endpoints for major cardiovascular events in AURORA Study 2005 and 4D Study 2004 (both showing no statistical effect on cardiovascular events) were a reason for negative studies of statins in dialysis, because definitions of endpoints included a smaller proportion of modifiable vascular events. While this is possible, even with the inclusion of SHARP Study 2010 (in which cardiovascular events were predominantly occlusive vascular outcomes including revascularisation procedures), statins had little or no effect on cardiovascular outcomes. Finally, data comparing a statin with another statin regimen (different drug or different dose) were sparse for people treated with dialysis.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, data evaluating the effects of statins on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes for dialysis patients is of moderate to high quality and suggests that additional studies are unlikely to change our confidence in the estimates of effect or our confidence in these results. The estimates of treatment effect for mortality, cardiovascular mortality and major cardiovascular events are derived from studies at generally low risks of bias, are consistent between studies, are precise, and are generalisable to dialysis populations outside the RCTs. Direct head‐to‐head data for different statin agents are sparse and inconclusive.

Potential biases in the review process

Although this review was conducted by two or more independent authors, used a comprehensive search of the literature designed by a specialist librarian that included grey literature, and examined all potentially relevant clinical outcomes, potential biases exist in the review process.

We were unable to include data for people treated with dialysis from SHARP Study 2010 or Stegmayr 2005 for all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality because reported data combined results for dialysis with earlier stages of kidney disease not treated with dialysis; separate unpublished data for dialysis populations were not available.

Many studies did not systematically report clinical outcomes: all but two either did not report or reported very few mortality events. Similarly, although meta‐analyses for mortality and cardiovascular events had no discernible heterogeneity, effects of statins on serum cholesterol levels were markedly different among studies. Subgroup analyses did not identify reasons for differences, including type of dialysis or baseline serum cholesterol.

Adverse events and stroke data were limited by wider confidence intervals and treatment effects were uncertain.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review analysed current evidence on statin therapy in adults treated with dialysis, updating evidence from its previous two iterations in 2004 and 2009 (Navaneethan 2004; Navaneethan 2009a). This update included 23 studies of statins versus placebo or no treatment in 8166 participants treated with dialysis and two head‐to‐head studies comparing two different statins.

Data from AURORA Study 2005 were included in analyses for mortality and major cardiovascular events, and data from SHARP Study 2010 informed analyses of major cardiovascular events. The effect estimates for statins on mortality and adverse events in this review were largely similar to our 2009 review (Navaneethan 2009a), finding little or no effect from statins among people treated with dialysis. The possible benefit from statins on non‐fatal cardiovascular events in our 2009 review (which included one study of 1255 participants, 4D Study 2004) was not confirmed following inclusion of three additional studies and more than 5000 participants.

The finding that statins had little or no effect on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in people treated with dialysis contrasts with a similar systematic review and meta‐analysis of studies in people with earlier stages of CKD (Palmer 2013a) and a prospective meta‐analysis of data of more general populations Baigent 2005. Statin therapy in people with less severe kidney disease proportionally reduced major cardiovascular events by 25% (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.79) and all‐cause mortality by 20% (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.91) (Palmer 2013a), and similarly reduced vascular events (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.81) and all‐cause mortality (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.91) in people with or at risk of cardiovascular disease in the general population (Baigent 2005).

In a recent analysis using the current data we showed that treatment effects of statins on mortality and cardiovascular events differ significantly based on stage of kidney disease (data not shown; Palmer 2012). Although it is unclear why, despite equivalent lowering of serum cholesterol, statins have less effect in people treated with dialysis, reasons may relate to the competing causes of cardiovascular morbidity (known and unknown) in people treated with dialysis that cannot be modified significantly by the lipid‐lowering or other pleiotropic effects of statins.

The smaller risk reductions from statins on death and cardiovascular disease in people treated with dialysis may reflect the competing mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients for whom vascular disease is dominated by vascular calcification, cardiomyopathy, hyperkalaemia, and sudden death, which might be modified to a lesser extent by statin therapy (ANZDATA 2009). We note that reductions in mortality were small in this meta‐analysis despite end of treatment LDL cholesterol lowering by 41 mg/dL (1.1 mmol/L) on average. This small relative effect of lipid‐lowering contrasts with a 12% risk reduction (95% CI 9% to 16%) for each 1 mmol/L reduction in LDL cholesterol in a meta‐analysis of studies in the general population (Baigent 2005). However, because few studies in the current meta‐analysis provided data for both all‐cause mortality and end of treatment lipid levels, we could not be certain if larger reductions in cholesterol levels might reduce mortality to a greater extent in the dialysis population or whether more aggressive lipid‐lowering approaches can be safely achieved with statin therapy.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Statins have little or no effect on mortality or major cardiovascular outcomes in adults treated with dialysis and cannot be routinely recommended to prevent cardiovascular events in this population. The body of included evidence did not address whether statin treatment should be stopped when a person commences dialysis, although the benefits associated with continued treatment are likely to be small. Risks of adverse events for statins on muscle and liver dysfunction and cancer with statin treatment remain uncertain. Insufficient data are available to understand whether treatment effects differ in the clinical setting of haemodialysis compared to peritoneal dialysis or the effect of statin therapy in patients with established vascular disease or recent vascular event.

Implications for research.

Statin therapy consistently provides little or no benefit for people treated with dialysis. Despite some limitations, the evidence is generally moderate to high quality according to GRADE recommendations (Guyatt 2008), indicating further large studies may have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect. Additional data for people treated with peritoneal dialysis would improve our confidence in the effects of therapy in this clinical setting. Well‐designed RCTs of other interventions to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and death in people on dialysis are now required.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 May 2014 | Amended | Minor copy edit made to study names |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2003 Review first published: Issue 4, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 July 2013 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | 14 new studies have been included |

| 11 May 2012 | Amended | Author added: Jorgen Hegbrandt; Suetonia Palmer |

| 1 March 2012 | New search has been performed | Updated search to February 2012. Ten new trials added including AURORA and SHARP. Results and conclusions updated. Conclusions generally unchanged. |

| 21 January 2009 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | New studies included, additional outcomes now available. New authors for this update. |

| 1 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of study authors (Drs Wanner, Baigent, Diepeveen, Harris) who provided data about their studies upon request. We also thank Narelle Willis, for her help in coordinating and editing this review and Ruth Mitchell and Gail Higgins for assistance in the development of search strategies. We also acknowledge Dr Rakesh Srivastava who contributed to a previous version of this review.

We wish to thank the referees for their comments and feedback during the preparation of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization (minimization may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available. | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Statin versus placebo or no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Major cardiovascular events | 4 | 7084 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.88, 1.03] |

| 2 All‐cause mortality | 13 | 4705 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.90, 1.02] |

| 3 Cardiovascular mortality | 13 | 4627 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.84, 1.06] |

| 4 Fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction | 3 | 4047 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.71, 1.07] |

| 5 Fatal and non‐fatal stroke | 2 | 4018 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.96, 1.72] |

| 6 Elevated creatine kinase | 5 | 3067 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.55, 2.83] |

| 7 Elevated liver function enzymes | 4 | 3044 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.41, 2.91] |

| 8 Withdrawal due to adverse events | 9 | 1832 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.87, 1.25] |

| 9 Cancer | 2 | 4012 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.72, 1.11] |

| 10 Total cholesterol | 14 | 1803 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐44.86 [‐55.19, ‐34.53] |

| 11 LDL cholesterol | 12 | 1747 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐39.99 [‐52.46, ‐27.52] |

| 12 Triglycerides | 13 | 1692 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐18.02 [‐31.00, ‐3.04] |

| 13 HDL cholesterol | 13 | 1769 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.57 [‐0.39, 5.52] |

Comparison 2. Statin versus another statin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Elevated liver function enzymes | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Withdrawal due to adverse events | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Total cholesterol | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 LDL cholesterol | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Triglycerides | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 HDL cholesterol | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

4D Study 2004.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Industry funding received | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated randomisation code |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation code prepared by a central unit that was independent of local study personnel |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All analyses of primary and secondary endpoints were based on the classification by the endpoint committee that was agreed by consensus or majority vote. All committee members were blinded to treatment assignments until 13 August 2004 |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants included in ITT analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published reports included all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Low risk | ITT |

Ahmadi 2005.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Abstract only | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Unclear risk | NR |

Angel 2007.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Abstract only publication | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Unclear risk | NR |

Arabul 2008.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | None |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Unclear risk | NR |

AURORA Study 2005.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Industry funding received | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All MIs, strokes, and deaths were reviewed and adjudicated by a clinical endpoint committee whose members were unaware of the randomised treatment assignments to ensure consistency of the event diagnosis |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No patients were lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published reports included all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Low risk | Conducted |

Burmeister 2006.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Industry funding received | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 3/59 (5%) lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published reports included all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | High risk | Not conducted |

Chang 2002.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Industry funding received | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 4/62 (6.5%) patients did not complete study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | High risk | Not conducted |

Diepeveen 2005.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

Treatment group 3

Control group

Treatment duration: 3 months |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Study included 4 arms and we compared treatment group 1 and the control group (see interventions) Industry funding received |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Complete follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Low risk | Conducted |

Dornbrook‐Lavender 2005.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Industry funding received | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 6/19 (32%) did not complete study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | High risk | Not conducted |

Han 2011.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 36/114 patients (32%) withdrawn |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Unclear risk | NR |

Harris 2002.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 130/153 (85%) completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | High risk | Not conducted |

Ichihara 2002.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Unclear risk | NR |

Lins 2004.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Industry funding received | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published reports included all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Unclear risk | NR |

PERFECT Study 1997.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group (B)

Control group (D)

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Study had four arms

Industry funding received |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "...the code identifying the treatment received by individual patients was maintained by a person remote from the investigators." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Low risk | Conducted |

Saltissi HD 2002.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes | Lipid parameters (TC, LDL, HDL, TG, Lp (a), Apo A1) | |

| Notes | This is the same study as Saltissi PD 2002 Industry funding received |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 42/57 patients (74%) completed study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published reports included all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | High risk | Not conducted |

Saltissi PD 2002.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes | Lipid parameters (TC, LDL, HDL, TG, Lp (a), Apo A1) | |

| Notes | This is the same study as Saltissi HD 2002 Industry funding received |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 42/57 patients (74%) completed study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published reports included all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | High risk | Not conducted |

SHARP Study 2010.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

Exclusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Only dialysis patients data from the SHARP Study 2010 trial have been included in this review Industry funding received |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocated by local study laptop computer with minimised randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Local laptop computer that was synchronised regularly with central database and double‐dummy treatment to ensure blinding |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐dummy 2 x 2 factorial design |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Central adjudication by trained clinicians who were masked to study treatment allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants included in analyses |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published reports included all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Low risk | Conducted |

Soliemani 2011.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

Treatment group 3

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Double blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Stegmayr 2005.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation by means of a telephone call to the study data centre where sealed envelopes were drawn |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All patients analysed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published reports included all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Low risk | Conducted |

Tse 2008.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Unclear risk | NR |

UK‐HARP‐I 2005.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Minimised randomisation used to balance the treatment groups; 2 x 2 factorial design |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was by telephone to the Clinical Trial Service Unit |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Matching placebo |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | All events were coded centrally according to a standard protocol. Otherwise unclear |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 442/448 (98.7%) patients completed follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published reports included all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | Low risk | Conducted |

van den Akker 2003.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 2/28 patients (7%) discontinued therapy |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Published reports did not include all expected outcomes |

| ITT analysis | High risk | Not conducted |

Vareesangthip 2005.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Abstract only | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | NR |