Abstract

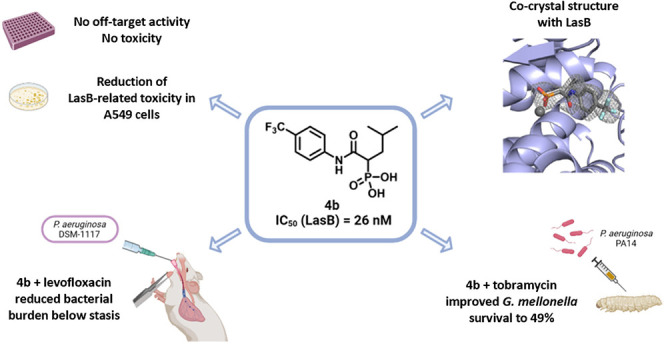

Infections caused by the Gram-negative pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa are emerging worldwide as a major threat to human health. Conventional antibiotic monotherapy suffers from rapid resistance development, underlining urgent need for novel treatment concepts. Here, we report on a nontraditional approach to combat P. aeruginosa-derived infections by targeting its main virulence factor, the elastase LasB. We discovered a new chemical class of phosphonates with an outstanding in vitro ADMET and PK profile, auspicious activity both in vitro and in vivo. We established the mode of action through a cocrystal structure of our lead compound with LasB and in several in vitro and ex vivo models. The proof of concept of a combination of our pathoblocker with levofloxacin in a murine neutropenic lung infection model and the reduction of LasB protein levels in blood as a proof of target engagement demonstrate the great potential for use as an adjunctive treatment of lung infections in humans.

Short abstract

New antivirulence agents targeting LasB demonstrate in vivo proof-of-concept and in vivo target engagement in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections.

Introduction

The silent pandemic of antimicrobial resistance is a global health threat, affecting millions of people worldwide. It is caused by natural mechanisms of pathogen defense, over- as well as misuse of antibiotics in humans as well as in animal husbandry. Consequently, even common infections are becoming increasingly problematic to treat. This leads to augmented costs in the healthcare sector including the necessity for longer treatments, and, despite that, still high mortality rates.1−4Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative bacterium which typically infects lungs, the urinary tract, and wounds, leading to severe infections challenging to treat due to drug-resistance.5 In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a priority list of pathogens raising the topic of an urgent need for novel antibiotics, in particular P. aeruginosa, identified as a top-three critical pathogen devoid of sufficient treatment options for drug-resistant strains.6P. aeruginosa is one of the major pathogens in cystic fibrosis (CF), as well as in noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB) patients, leading to chronic lung infection and poor pulmonary function.7−10 Furthermore, the pathogen plays important roles in hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia, urinary-tract infections,11 keratitis,12 and wound infections.13 Taken together, there is an immediate necessity for the development of new anti-infectives–antibiotics with novel mechanisms of action or nontraditional approaches to fight antibiotic resistance, in particular, against Gram-negative pathogens.14

Recently, significant efforts have been put into the development of “pathoblockers”, agents capable of blocking bacterial virulence by disarming, rather than killing the pathogen. This should reduce the selection pressure and the formation of resistance.15,16 In particular, pathoblocker-antibiotic combinations are expected to have a synergistic effect and result in a more successful treatment.17P. aeruginosa secretes several virulence factors that serve as promising targets for the development of such pathoblockers.18 A central contributor to P. aeruginosa virulence is the elastase LasB, which plays a crucial role in the infection process. This extracellular proteolytic enzyme is responsible for tissue damage and has a destructive effect on various components of the immune system.19 These pathological roles strongly advise the development of drugs against P. aeruginosa by inactivating LasB, as recently thoroughly reviewed by Everett and Davies.20 In addition, one recent study came to the remarkable conclusion that elastase activity appears to be associated with 30-day mortality in intensive care unit patients.21 LasB or pseudolysin is a zinc-dependent metalloenzyme with an additional metal cation (Ca2+) as a cofactor in the active site.22 Therefore, the vast majority of the studied inhibitors contain zinc-binding groups (ZBGs), such as thiols,23,24 hydroxamates,25 carboxylic acids,26 tropolones,27 or 3-hydroxypyridine-4(1H)-thiones.28 We have extensively explored these ZBGs in the past few years and used those findings as the basis for the current work.29−33

Given the instability of thiols due to oxidation, we here present a systematic study of the 15 most common ZBGs as a suitable replacement for the thiol liability present in our inhibitors of LasB. Our ultimate goal is the identification of a stable, active, and safe pathoblocker to fill the dry antibiotic pipeline. In view of the envisioned application of these compounds as novel anti-infectives in vivo, the rationale of the most favorable ZBG was supported by in vitro absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiling. Taken together, these data strongly favored the phosphonic acid derivatives as the most promising class. Pharmacokinetic studies in mice showed that these compounds have an excellent retention in lung tissue and epithelial lining fluid (ELF). In a pharmacodynamics study, the combination of the phosphonic acid inhibitor 4b with levofloxacin reduced the bacterial burden below stasis in mice infected with P. aeruginosa DSM-1117. Additionally, a reduction of LasB protein in blood was observed, demonstrating target attainment of our pathoblockers.

Results and Discussion

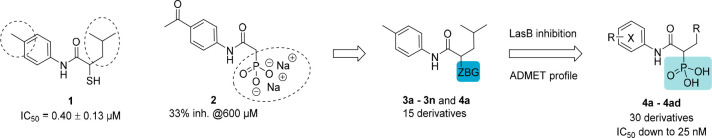

Replacing the Thiol

Previously, we reported on N-aryl-2-isobutylmercaptoacetamides showing submicromolar potencies against P. aeruginosa elastase LasB (thiol 1, Figure 1).29 The approach to inhibit LasB (as a metalloprotease) comes with the intrinsic challenge of target selectivity over biochemically related human off-targets such as the human matrix-metalloproteases (MMPs). Despite being highly potent and selective over MMPs, the potential therapeutic application of N-aryl-2-isobutylmercaptoacetamides is limited due to the poor chemical stability of the free thiol group. Recently, we performed a screening of various ZBGs and investigated their effect on the activity against ColH, a collagenase secreted by Clostridium histolyticum.34 As this target is structurally and mechanistically closely related to LasB, we built on this knowledge and performed a similar screening on LasB. Phosphonate derivative 2 demonstrated modest activity toward LasB (Figure 1, Table S1). Our recent work on N-aryl-2-isobutylmercaptoacetamide 1(29) suggested the importance of an alpha-alkyl substituent for the inhibition of LasB. Therefore, we designed 15 derivatives bearing an alpha-isobutyl side chain and different ZBGs, which yielded sulfonates, triazoles, hydroxamates, and phosphonates as possible alternatives to the thiol. Among them, the most potent turned out to be the hydroxamic acid derivative 3g and the phosphonic acid 4a. Subsequent exploration of their in vitro ADMET properties confirmed phosphonates to be the most promising class (Table 1, Table S2–S4). The detailed synthetic procedures of mentioned inhibitors have been described in Figures S1–S5.

Figure 1.

Optimization of 1 leading to phosphonate derivatives with nanomolar IC50 values against LasB (Table 1, Table S2–S4).

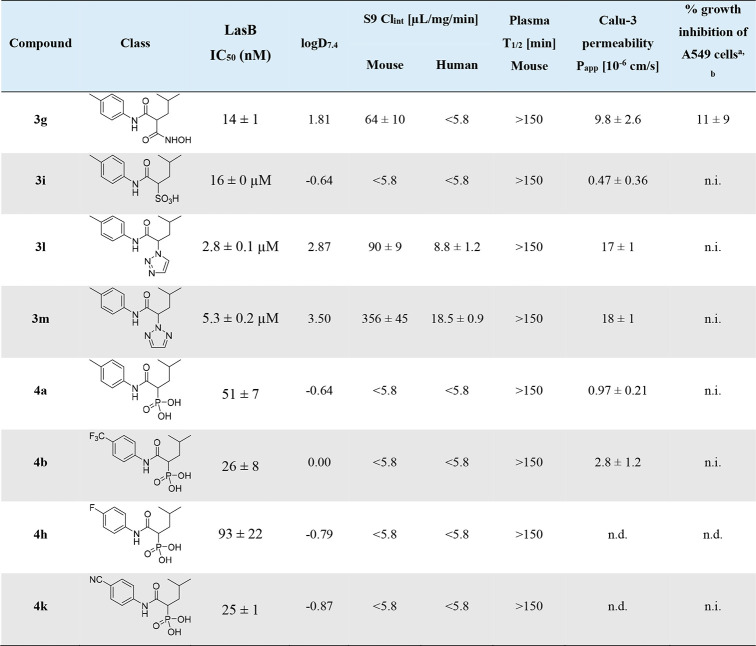

Table 1. LasB Inhibition and Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) Profiling of Selected Compounds Bearing Different Zinc-Binding Groups (ZBGs).

After 48 h at 100 μM.

Further cytotoxicity data using cell lines HEK293 and HepG2 can be found in Table S6; n.d. = not determined; n.i. = < 10% inhibition; kinetic solubility was determined to be >200 μM for all tested compounds.

LasB Inhibition by Compounds with Different ZBGs

We evaluated new derivatives for in vitro inhibition of LasB (Table S2) using a functional FRET-based assay, as established by Nishino et al.35 The corresponding thiol analogue 1 was used as comparator.29 Among 15 derivatives, five compounds showed IC50 values below 20 μM. The sulfonic acid derivative 3i and two triazole derivatives 3l and 3m showed activity in the micromolar range, while the most pronounced activity was observed for the hydroxamic acid 3g (IC50 = 14 ± 1 nM) and the phosphonic acid derivative 4a (IC50 = 51 ± 7 nM). We improved activity by 30-fold and 8-fold, respectively, compared to our previous thiol hit 1. As it has been shown previously that surfactant can impair the activity of drugs targeting the lung,36 we determined IC50 values in the presence of 1% pulmonary surfactant for our frontrunners. 4b did only exhibit a 3-fold increase in IC50, resulting in potency in the nanomolar range (IC50 = 76 ± 23 nM).

Structure–Activity Relationships (SARs) of Phosphonic Acid Derivatives

The SARs were investigated by exploring three major modifications, including the substitution pattern of the aromatic core, replacement of the phenyl ring with 6-membered nitrogen heterocycles, and structural variations of the side chain, yielding in total a library of 30 phosphonic acid derivatives (Tables S3–S4). The most active derivative showed 16-fold improvement in the activity compared to our previous hit 1, showing efficacy against LasB in the nanomolar range.

Among the first group of compounds bearing an α-isobutyl side-chain, we explored a different substitution pattern of the aromatic core, including electron-withdrawing and electron-donating substituents, both polar and lipophilic. From our previous work on α-substituted and nonsubstituted N-arylmercaptoacetamides,29−32 we knew that the para-position is more favorable for the activity compared to ortho and meta. Therefore, we explored the para-position with regard to the nature of the substituents introduced. All derivatives bearing electron-withdrawing substituents proved to be more active than those bearing electron-donating substituents. Among them, those with lipophilic substituents, such as 3,4-dichloro (4c) or 4-trifluoromethyl (4b), were 1.6-fold more active than those with polar electron-withdrawing substituent such as 4-acetyl (4g). Not only did the electronic properties influence the activity but the steric effects did as well, as illustrated by compounds 4h (−F), 4i (−Cl), and 4j (−Br). These compounds all bear lipophilic substituents, only the former one bears fluorine, which turned out to be 2-fold less active than the other compounds bearing chlorine and bromine. The tolerability of sterically even more demanding substituents can be further seen in compounds with 1-naphthyl (4m), 2-naphthyl (4n), and 2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-5-yl (4o) as an aryl ring.

Ortho-substituents have a great impact on the conformation and electronic properties, thus indirectly influencing solubility. To explore the SAR around the aromatic core by not only changing the nature of the para-substituents, we synthesized 2-F-4-Me (4d) and 2,4-diMe derivatives (4e). Both of them demonstrated a ∼2-fold drop in activity compared to the 4-Me derivative (4a), most probably by changing the active conformation, 4d through plausible hydrogen-bonding with the amide functional group and 4e through steric effects.

To assess the importance of the α-isobutyl side-chain, we synthesized two derivatives with an α-benzyl (4x and 4y), two with an α-methylcyclohexyl (4z and 4aa), and three with an α-propyl side chain (4ab–4ad). In our previous work with thiol-containing compounds, we demonstrated that α-benzyl derivatives exhibit similar activities as α-isobutyl, while the methylcyclohexyl ones show up to a 30-fold drop in activity.29−32 To explore the α-substitution pattern in the new phosphonic acid-class, we have chosen 4-Me and 4-CF3 substituents on the left-hand side of the molecule, the former one being a direct comparison to 1, while the latter being one of the most active representatives within the isobutyl class. With regard to the nature of the substituents on the aromatic ring, we noticed the same trend in all three classes: compounds bearing lipophilic trifluoromethyl substituent were more active than their methyl-analogues (4b vs 4a, 4y vs 4x, and 4aa vs 4z). On the other hand, we observed that a benzyl side-chain led to a 3-fold drop in activity, while the methylcyclohexyl derivatives were active in the micromolar range. That the isobutyl side-chain is crucial for the activity is further confirmed with the series of three propyl derivatives (4ab–4ad), all three showing a micromolar potency, with a 20–80-fold drop in activity compared to their isobutyl analogs.

To further expand the SAR, we synthesized a small series of eight derivatives with 6-membered nitrogen-containing heterocycles, including pyridine, pyrimidine, and pyridazine, which might have an influence on the solubility and a metabolic profile (Table S4). In most of the compounds, we kept the 4-halo substituent, as we have shown that it is beneficial for activity. Unfortunately, all eight heterocyclic derivatives showed a drop in activity, from 8-fold (4s, IC50 = 0.19 μM) to 800-fold (4v, IC50 = 18.8 μM) compared to the most active compounds of the isobutyl series (IC50 ∼ 25 nM). That the position of the nitrogen has an impact on the activity is seen from a comparison of the 5-chloropyridin-2-yl- (4p) and 6-chloropyridin-3-yl- (4q) derivative, with the former one being 2-fold more potent. Surprisingly, substituents such as carboxamide and carboxymethyl reversed the activity profile of derivatives containing a nitrogen atom in the meta-position. Among pyrimidine and pyridazine derivatives, bromo-substituents proved more beneficial for activity compared to chloro-substituents, while in cases of both halogens, pyrimidine derivatives (4t and 4u) were significantly more active than the pyridazine (4v and 4w).

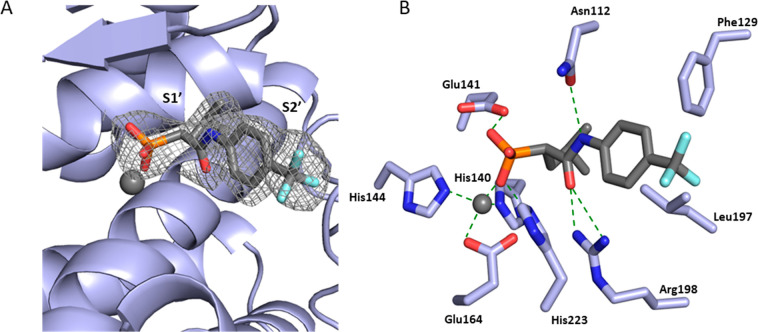

Crystal Structure of 4b

To elucidate the binding mode of phosphonic acid derivatives, we cocrystallized 4b with LasB (Figure 2A). Full details of the data collection and refinement statistics can be found in Table S13. The compound binds in a fashion that is similar to a previously reported α-substituted mercaptoacetamide derivative (PDB code: 7OC7)31 and occupies the S1′-S2′ pockets with the phosphonate group coordinating the active site Zn2+ cation (Figure S13A). In addition, 4b also forms a number of additional H bonds and hydrophobic interactions that can be seen on Figure 2B. This explains the significant improvement in activity over the mercaptoacetamide class. The carbonyl oxygen of 4b forms a bidentate hydrogen bond with Arg198, while the side chains of His223, Glu141, and Asn112 form hydrogen bonds with the phosphonate and amide groups. The aryl group occupies the wide, open, and solvent-accessible entrance of the lipophilic S2′ binding pocket, which rationalizes the tolerance for substitution at this position (Figure S13B). The replacement of the isobutyl group by bulkier substituents is detrimental, likely due to the steric constraints of the S1′ pocket that cannot accommodate such large groups without a steric clash (Figure S13A).

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of LasB in complex with 4b (PDB code: 8CC4). (A) Cartoon representation of LasB (slate) in complex with 4b (gray), with the S1′ and S2′ binding-sites of the enzyme occupied by the compound highlighted. The gray isomesh represents a polder map of 4b contoured at 3 σ. (B) Schematic 2D representation of LasB-4b interactions. Hydrogen bonds are displayed in dotted green lines, while all other residues exhibit hydrophobic interactions with the ligand. The active site Zn2+ cation is shown as a gray sphere.

ADMET Profiling

To select the most suitable ZBG for our LasB inhibitors, we considered their in vitro ADMET profile along with their in vitro potency (Table 1). For this purpose, we compared hydroxamic acid derivative 3g, sulfonic acid 3i, and the two triazoles 3l and 3m, with the phosphonic acids 4a, 4b, 4h, and 4k. A key decision criterion was permeability across Calu-3 monolayers, which constitutes an important feature of antipseudomonal drugs targeting the lung. Since our overall goal was to achieve good lung retention after pulmonary administration, low permeability was desirable to avoid rapid dissemination of the LasB inhibitor into systemic circulation. Sulfonic acid 3i (Papp = 0.47 × 10–6 cm/s) and phosphonic acids 4a and 4b (Papp = 0.97 × 10–6 cm/s and 2.8 × 10–6 cm/s, respectively) showed the lowest Papp values. Additionally, we investigated kinetic solubility and lipophilicity (log D7.4), murine and human metabolic stability, as well as murine plasma stability (Table 1). The results suggest that the phosphonic acid derivatives have the best overall ADMET profile, i.e., high solubility, low lung permeability, and high stability in mouse and human liver S9 fractions and mouse plasma. Further, we profiled three selected phosphonates regarding their metabolism in different species, confirming excellent metabolic and plasma stability in rat and minipig (Table S5).

To rationalize the observed striking differences in cell permeability, we correlated the measured permeabilities Papp with chromatographic lipophilicities log D7.4 (Figure S6). Notably, there is a very good correlation between compound lipophilicity and Calu-3 permeability for our set of LasB inhibitors (R2 = 0.9865). Namely, hydroxamate 3g as well as triazoles 3l and 3m give significantly higher log D7.4 values (>1.8) compared to the phosphonates (log D7.4 ≤ 0). This correlation strengthens our selection of phosphonates as the most promising ZBG, given that their high hydrophilicity and negative charge at physiological pH reduces the permeability across the more lipophilic cell layer, hence favoring lung retention. Furthermore, this good correlation can potentially be applied in the future as a useful tool to rationally design compounds with physicochemical properties favorable for good lung exposure.

Representative derivatives were tested for their cytotoxicity on three human cell-lines: HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma), HEK293 (embryonal kidney), and A549 (lung carcinoma). All measured growth inhibition values were less than 30% at 100 μM, thus all compounds showed an excellent profile and did not bear cytotoxicity potential at concentrations relevant for in vivo assessment (Table 1, Table S6).

Biological Evaluation of Phosphonic Acids in Target Validation Models

To assess the activity of the phosphonic acid class in target–validation models, we tested selected compounds in two different cell-based assays including lung organoids, constituting an increasingly complex matrix close to the physiological setting, as well as in a simple in vivo model based on Galeria mellonella larvae.

Evaluation of LasB Inhibitors in A549 Cells Treated with P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 Supernatants

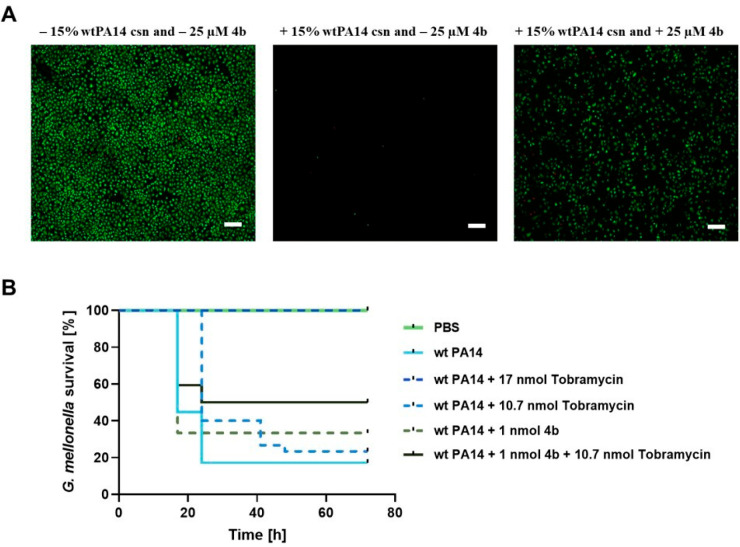

First, we challenged the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 with culture supernatants (csn) derived from wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1 or PA14 (wt PAO1; wt PA14) as well as lasB knockout strains (PAO1 ΔlasB; PA14 ΔlasB) to assess the inhibitory effect of two phosphonate LasB inhibitors, 4a and 4b, on the proteolytic, elastolytic, and cytotoxic properties. Both compounds demonstrated an excellent dose-dependent reduction of LasB-related cytotoxicity in csn-treated cells, comparable to the levels of the knockout strain. This illustrates impressively the relevance of LasB and its inhibition (Figure S7A–B). Interestingly, higher concentrations of 4b were necessary to achieve similar effects against PA14 csn, which could be attributed to the higher amounts of secreted LasB by PA14 (Figure S7D).

Compound 4b sustained viability of cells, even at low concentrations (Figure 3A, Figure S8).29,32,37 LasB targets the extracellular matrix component collagen and leads to its degradation. 4b reduced cleavage of collagen by 20% at a concentration of 3.15 μM (Figure S7C).20,38,39 To exclude that effects of 4b might be attributed to other proteases in PA14 csn, we deployed PA14 ΔlasB csn. No effect on the viability and on collagen was observed using the ΔlasB csn (Figure S7B–C). This demonstrates that 4b selectively inhibited LasB and did not affect other proteases in the csn.

Figure 3.

(A) 4b maintained the viability of lung (A549) cells upon treatment with 15 wt % PA14 csn. Live/dead imaging with A549 cells challenged with 15% (v/v) of PA14 csn with and without 4b. Green signals: living cells; red signals: dead cells. Red signals in some cases were lost because the detached cells were washed away after the rinsing step with PBS. Scale bar: 200 μm for images. (B) Probability of survival of the Galleria mellonella larvae infected with wt PA14: The survival of larvae infected with wt PA14 is shown after treatment with 1 nmol 4b, 10.7 nmol tobramycin, or a combination of both. The survival in the PBS-4b or tobramycin or combination of both treated groups was 100%. The statistical difference between groups treated with 1 nmol 4b + 10.7 nmol tobramycin and treated with only wt PA14 is p = 0.0005 (log-rank). Each curve represents results of three independent experiments. wt PA14: wild-type PA14; ΔPA14: LasB knockout PA14; and csn: culture supernatant.

Lung Organoid Assay

In the past years, lung organoids have been extensively used to study pulmonary diseases due to the high resemblance of their structural features and their functions with the native lung.40,41 We studied the effect of PA14 csn on the viability of 3D lung organoids and the rescue effect by inhibitors 4a and 4b (Figure S9). In this experiment, primary human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) were differentiated to human 3D bronchospheres42 and challenged with 5% PA14 csn. LasB inhibitors 4a and 4b did not have significant toxic effects on the nontreated lung organoids in concentrations tested up to 100 μM. Upon treatment with PA14 csn, viability of the organoids was reduced to 30–60%. By contrast, treatment with LasB inhibitors 4a and 4b resulted in a strong beneficial effect as viability of the organoids was improved in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S9). Therefore, effectiveness of LasB inhibitors was also demonstrated in the 3D model constituting a complex matrix system close to the physiological situation.

Effect of 4b in a G. mellonella Infection Model

Next, we infected G. mellonella larvae, a standard model for evaluation of novel anti-infectives,43 with wt PA14 and treated them with 4b and tobramycin (individually and in combination), a standard-of-care antibiotic in CF.44 For the combination experiments, we chose a lower tobramycin dose (10.7 nmol, corresponding to 0.5 μg/mL in the dosed solution), aiming at the improvement of a subefficacious dose of tobramycin with 4b. A higher tobramycin dose of 17 nmol (0.8 μg/mL) was used as 100% efficacious dose of the antibiotic. While treatment with 4b or tobramycin at a low dose alone only led to a slight increase in survival (33% and 23%, respectively, compared to 17% in the wild type), the combination of 4b and tobramycin significantly improved the survival to 49% (Figure 3B).

Importantly, 4b as well as further selected phosphonates do not possess any antibacterial activity up to 100 μM (Figure S10C). In line with this, the combination with tobramycin did not increase the antibacterial activity of the antibiotic alone in vitro (Figure S10A-B), indicating that the observed improvement of in vivo activity was caused by the antivirulence effect of the LasB inhibitor. Hence, this study reinforced the potential of our compound to boost the efficacy of antibiotics in vivo by targeting the virulence factor LasB.

Selectivity for LasB over Human off-Targets and Other Bacterial Proteases As Well As Advanced off-Target Safety Screening and Zebrafish Embryo Toxicity

Next, we aimed to test selectivity against human off-targets and other bacterial proteases and safety. We assessed four most potent inhibitors (4a, 4b, 4k, and 4l) which showed a significantly improved selectivity profile against human off-targets compared to our previously published hit, compound 1 (Table S7). 4b and 4k had slight effects at 100 μM against MMP-1, -2, and -3 (with shallow, intermediate, and deep binding pockets, respectively), which was negligible when compared to their activity toward LasB (IC50 ∼ 25 nM). On the contrary, the hydroxamic acid 3g, although being 2-fold more potent compared to the best phosphonate inhibitor, exhibited slight effects on MMP-1, -2, and -3 and inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme (TACE) in the micromolar range (Table S7). In contrast, the phosphonic acids did not inhibit TACE, HDAC-3, HDAC-8, and COX-1 (Table S7). We previously reported on a structural similarity between inhibitors of P. aeruginosa elastase LasB and C. histolyticum collagenase ColH.30,33,34 Most of our newly developed inhibitors demonstrated no or only weak inhibition of ColH-PD (4a, 4b, 4c, 4d, and 4f), with the notable exception of 4g. This compound was a more potent ColH inhibitor than the previous “best-in-class” phosphonate inhibitor of ColH, i.e., 1 (see Supporting Information). It might therefore be developed toward a dual inhibitor of both metalloprotease virulence factors LasB and ColH if a medical need for such an agent with dual activity arises (Table S8).

Then, we assessed potential additional safety liabilities of 4a and 4b using the Eurofins SafetyScreen44 panel to identify the most important off-target interactions at an early stage. When tested at a concentration of 10 μM, compound 4a demonstrated an excellent safety profile with no significant inhibition of any of the mentioned targets (Figure S11). Furthermore, to gain a deeper insight into the potential clinical applicability, we investigated the toxicity of compounds in vivo on zebrafish embryos. Compounds 4a and 4b demonstrated a maximum tolerated concentration (MTC) of ≥100 μM (Table S9). In summary, 4a and 4b demonstrated an excellent safety profile qualifying for additional in vivo preclinical testing.

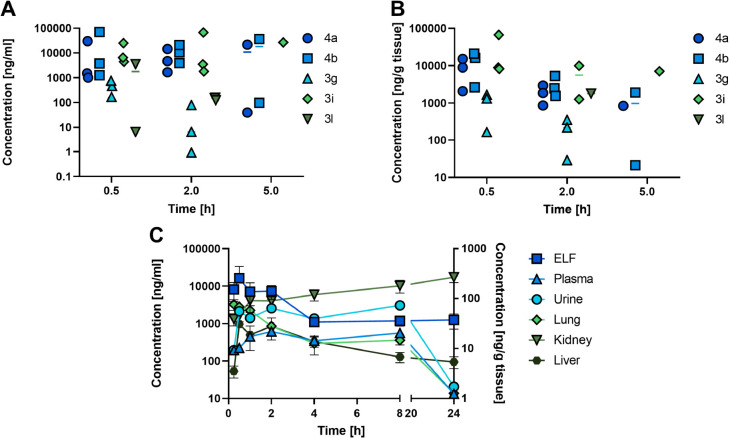

Pharmacokinetic Studies in Mice

To further assess the potential of the new inhibitors for the treatment of lung infections, we subjected five selected compounds (3g, 3i, 3l, 4a, and 4b) to pharmacokinetic studies in mice as a cassette dosing via intratracheal (IT) administration. The selection comprised representatives bearing different ZBGs in order to assess whether the observed differences in their in vitro permeabilities also resulted in different lung retentions in vivo. Hydroxamic acid 3g and triazole derivative 3l were found in ELF and lung tissue at significantly lower concentrations compared to sulfonic acid 3i and phosphonic acids 4a and 4b. Moreover, hydroxamic acid 3g was not detected 2 h after administration, which is perfectly in line with the observed differences in Calu-3 cell permeation. Quite remarkably, the concentrations of both phosphonic acids 4a and 4b were significantly above the IC50 values determined in the FRET-assay in the presence of surfactant (Figure 4A,B, Table S10). The concentration levels of the five selected compounds in BALF, plasma, urine, kidney, and liver tissue are summarized in Figure S12.

Figure 4.

(A) Concentrations of five selected ZBGs in ELF and (B) lung tissue after IT administration at 0.25 mg/kg (cassette dosing). (C) Concentrations of 4b after nebulization of 10 mg/kg in ELF, plasma, urine, lung tissue, kidney tissue, and liver tissue.

Following IT cassette dosing, we performed a more focused PK study with compound 4b at a single dose of 10 mg/kg, administered by nebulization (Figure 4C). Selection of this compound for further in vivo analysis was based on the highest levels reached in ELF. Samples were analyzed for a period of 24 h. The compound rapidly appeared systemically and was detected in plasma, urine, ELF, lung tissue, kidney, and liver already after 15 min (Figure 4B). Still, the compound had high initial ELF levels with a Cmax of about 20 μg/mL (∼770-fold relative to the IC50 value in the presence of surfactant) and remaining in a moderate range until 24 h (Table S11). Lung tissue concentrations followed similar kinetics, although the concentration levels dropped significantly after 8 h. 4b appeared rapidly in plasma with a Tmax of about 4 h and a Cmax of about 633 ng/mL (Figure 4B, Table S12). Nevertheless, 4b exhibited only a moderate to low fractionated plasma clearance (Table S12). Furthermore, low compound levels were observed in the liver tissue, whereas kidney tissue showed increasing levels. In line with the observed absence of liver metabolism in vitro and high concentrations found in urine, these findings suggest primarily renal clearance of the unmodified inhibitors.

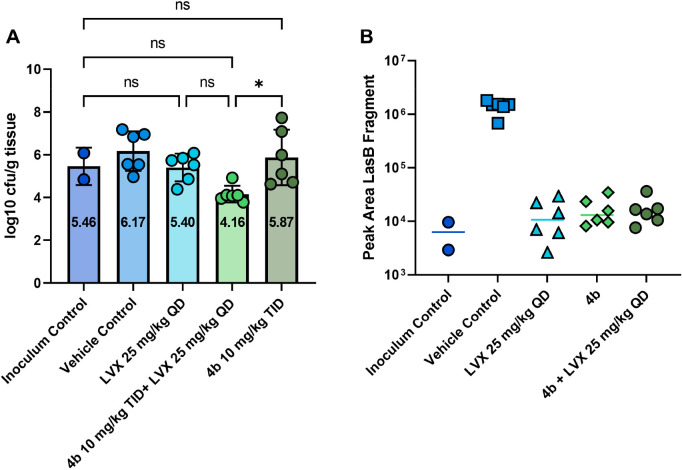

Pharmacodynamic Studies in Mice Infected with P. aeruginosa DSM-1117

Encouraged by the results of 4b in several in vitro and ex vivo assays, its efficacy in the in vivo infection model in G. mellonella, as well as the excellent lung and ELF retention after IT administration (0.25 mg/kg, cassette dosing) and nebulization (10 mg/kg), we performed a pharmacodynamic (PD) study using a neutropenic lung infection model with P. aeruginosa DSM-1117. In this experiment, we evaluated the effect of the antibiotic levofloxacin at 25 mg/kg, 4b at 10 mg/kg TID, and a combination of both on the number of CFU in the lungs of the mice. The bacteria and 4b were applied by nebulization, whereas levofloxacin was administered IP. Figure 5A shows the bacterial growth in lung tissue. A slight growth of bacteria was observed in the vehicle control group compared to the inoculum control. The levofloxacin group reduced the bacterial burden back to stasis, while 4b alone did not show an effect on the number of CFU. For a pathoblocker reducing virulence of a bacterium rather than killing it, this is not necessarily to be expected, especially in a neutropenic model. Adjunctive therapy is further considered a valid strategy in the development of antivirulence agents.14,45−48 Remarkably, the combination of 4b and levofloxacin showed a clear synergistic effect, significantly reducing the bacterial burden below stasis. Moreover, assessment of LasB protein levels in blood as an indicator of dissemination showed a clear reduction for levofloxacin and the combination group compared to the vehicle group and back to the level of the inoculum control group. Remarkably, a strong reduction was also observed for the 4b only group, although no effect on CFU had been detected in lung tissue. This reduction in the presence of the LasB inhibitor, 4b, and in absence of levofloxacin provided the proof of concept and target engagement (Figure 5B) and allows speculation about a possibly, highly desirable, lower bacterial dissemination into the body.

Figure 5.

(A) Bacterial growth in lung tissue given as log 10 cfu/g tissue. Mice in all groups were treated with P. aeruginosa DSM-1117. Inoculum control, the number of colony-forming units (cfu) in the lungs was determined 15 min after infection; all other lungs were taken after 24 h; vehicle control: mice treated with a vehicle; LVX 25 mg/kg: mice treated with levofloxacin; 4b 10 mg/kg TID (3 times per day) + LVX 25 mg/kg: mice treated with a combination of 4b and levofloxacin; 4b 10 mg/kg TID: mice treated with 4b. (B) LasB levels in blood in mice infected with P. aeruginosa DSM-1117.

Conclusions

Targeting bacterial virulence is a compelling approach as it provides a milder selective pressure for the emergence of resistance compared to conventional antibiotics, which are killing the bacteria or preventing their growth. Given its extracellular location, LasB is considered a particularly attractive target in the current antimicrobial resistance crisis. Inhibitors targeting this enzyme are circumventing the permeability challenge as they do not need to cross the Gram-negative cell wall of P. aeruginosa to demonstrate activity. A systematic exploration of ZBGs furnished a new class of phosphonic acid inhibitors showing nanomolar potency toward LasB and an excellent in vitro ADMET profile. We demonstrated that the compounds with the lowest permeability in the Calu-3 assay are at the same time showing the highest levels in ELF and a good lung retention with concentrations several magnitudes above IC50 values in the presence of surfactant. This correlation of Calu-3 in vitro and PK in vivo data supports the use of Calu-3 assays as a predictive tool for the selection of compounds for in vivo studies, thereby increasing the success rate of these animal models while at the same time reducing the number of animals needed for testing. In the G. mellonella infection model, compound 4b in combination with tobramycin demonstrated a significant improvement in survival which was translated into efficacy in a murine neutropenic lung infection model with P. aeruginosa DSM-1117, where the same compound in combination with levofloxacin reduced the bacterial burden significantly below stasis. These results highlight the potential of LasB inhibitors to be combined with different classes of antibiotics. Further in vivo proof of concept and target engagement was demonstrated by significantly reduced LasB levels in the blood even when 4b was used as monotherapy. Without affecting bacterial growth while at the same time clearly demonstrating strong antivirulence effects against LasB in vitro and in several target-validation models, the potential of our inhibitors as a new class to be used in a combination therapy with standard-of-care (SOC) antibiotics for the treatment of lung infections in humans is supported. In conclusion, our study provides novel pathoblockers targeting LasB with high potency, excellent safety, and selectivity profile and demonstrated in vivo proof of concept as well as proof of target engagement, perfectly suited for further development via inhalative administration to enrich treatment options of infections in CF and NCFB patients.49 The results described above represent an important milestone for the development of anti-infective agents targeting LasB. To the best of our knowledge, here we demonstrated for the first time a significant increase of the SOC antibiotics’ efficacy in an adjunctive therapy with a LasB inhibitor. Our future work will focus on further optimization of the presented inhibitors with regard to their potency, pharmacokinetic properties, and in vivo efficacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank S. Wolter, S. Speicher, J. Jung, S. Amann, P. Paul, and T. Trampert for excellent technical support and V. Camberlein and C. Schütz for providing important intermediates. Moreover, the authors thank A. Ahlers, J. Schreiber, K.V. Sander, and J. Wolf for excellent technical assistance. The authors acknowledge DESY (Hamburg, Germany), a member of the Helmholtz Association HGF, for the provision of experimental facilities. Parts of this research was carried out at PETRAIII, and we would like to thank Dr. Johanna Hakanpää for assistance in using the photon beamline. Beamtime was allocated for proposal (Xh-20010236).

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.3c01102.

Experimental procedures for the synthesis of all compounds; NMR spectra of compounds 3g, 3i, 3l, 3m, 4a, 4b, 4h, and 4k; materials and methods; and supplementary text: synthesis of derivatives bearing different ZBGs, ADMET profiling, selectivity against human off-targets, activity against Clostridium histolyticum collagenase ColH, off-target safety screen44 panel, and zebrafish embryo toxicity; and Figures S1–S13, Tables S1–S13, and references (50–74) (PDF)

Author Present Address

● Innovation Campus Berlin (Nuvisan ICB GmbH), Berlin 13353, Germany

Author Present Address

▼ Merck Healthcare KGaA, Darmstadt 64293, Germany

Author Contributions

A.M.K. and A.A. contributed equally. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. Design of the study: J.K., A.M.K., R.W.H., K.R., J.H., A.K.H.H.; project management: J.H. and A.K.H.H.; design and synthesis of inhibitors: J.K., A.S.A., K.V., C.D.; evaluation of LasB activity: J.K.; ADMET profiling: A.M.K.; Calu-3 assay: B.L., C.M.L.; experiments on A549 cells: Al.A., R.S.; Galleria mellonella experiment: Al.A.; lung organoid assay: C.B., R.B., Y.Y.; cytotoxicity and selectivity profile: J.H.; zebrafish embryo toxicity: An.A., R.M.; evaluation of ColH activity: E.S., H.B.; PK and PD studies and LC–MS/MS assays on LasB: K.R.; X-ray: A.S. and R.M.; writing–original draft: J.K.; writing–review and editing: J.K., A.M.K., J.H., K.R., A.K.H.H., with a contribution of all authors.

CARB-X funding ID 05CARB-X0891 (A.K.H.H.); European Research Council, ERC starting grant 757913 (A.K.H.H.); Helmholtz-Association’s Initiative and Networking Fund (A.K.H.H.); Austrian Science Fund (F.W.F.), P 31843 (E.S.); German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), call “Alternative methods to animal experiments” (project 3-REPLACE, 16LW0140K) (C.B., R.M.); and Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (J.K.).

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): J.K., K.V., A.S.A., A.M.K., J.H., C.D., A.K.H.H., and R.W.H. are co-inventors on the international patent application (PCT/EP2021/073381) that incorporates methods outlined in this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- WHO Antibiotic resistance: 31 July 2020 Key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance (accessed 31 January 2023).

- Ventola C. L. The Antibiotic Resistance Crisis, Part 1: Causes and Threats. P T. 2015, 40, 277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators . Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators . Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2022, 400, 2221–2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti M.; Vena A.; Croxatto A.; Righi E.; Guery B. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Drugs Context 2018, 7, 212527. 10.7573/dic.212527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO priority pathogens list. https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed (accessed 31 January 2023).

- Malhotra S.; Hayes D. Jr.; Wozniak D. J. Cystic Fibrosis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the Host-Microbe Interface. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00138-18 10.1128/CMR.00138-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo T. E.; Duong J.; Jervis N. M.; Rabin H. R.; Parkins M. D.; Storey D. G. Virulence adaptations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Microbiology 2016, 162, 2126–2135. 10.1099/mic.0.000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellberg B.; Talbot G. Recommended Design Features of Future Clinical Trials of Antibacterial Agents for Hospital-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia and Ventilator-Associated Bacterial Pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, S150–S170. 10.1086/653065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig S. M.; Truwit J. D. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 637–657. 10.1128/CMR.00051-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas Ferreiro J. L.; Álvarez Otero J.; González González L.; Novoa Lamazares L.; Arca Blanco A.; Bermúdez Sanjurjo J. R.; Rodríguez Conde I.; Fernández Soneira M.; de la Fuente Aguado J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa urinary tract infections in hospitalized patients: Mortality and prognostic factors. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0178178 10.1371/journal.pone.0178178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliam Y.; Kaye S.; Winstanley C. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and microbial keratitis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 69, 3–13. 10.1099/jmm.0.001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirketerp-Møller K.; Jensen P. Ø.; Fazli M.; Madsen K. G.; Pedersen J.; Moser C.; Tolker-Nielsen T.; Høiby N.; Givskov M.; Bjarnsholt T. Distribution, Organization, and Ecology of Bacteria in Chronic Wounds. J. Clin Microbiol. 2008, 46, 2717–2722. 10.1128/JCM.00501-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walesch S.; Birkelbach J.; Jézéquel G.; Haeckl F. P. J.; Hegemann J. D.; Hesterkamp T.; Hirsch A. K. H.; Hammann P.; Müller R. Fighting antibiotic resistance—strategies and (pre)clinical developments to find new antibacterials. EMBO Reports 2023, 24, e56033 10.15252/embr.202256033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S.; Sommer R.; Hinsberger S.; Lu C.; Hartmann R. W.; Empting M.; Titz A. Novel Strategies for the Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 5929–5969. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert M. B.; Jumde V. R.; Titz A. Pathoblockers or antivirulence drugs as a new option for thetreatment of bacterial infections. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 2607–2617. 10.3762/bjoc.14.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezzoagli C.; Archetti M.; Mignot I.; Baumgartner M.; Kümmerli R. Combining antibiotics with antivirulence compounds can have synergistic effects and reverse selection for antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLOS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000805 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Haj Khalifa A.; Moissenet D.; Vu Thien H.; Khedher M. Virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and modes of regulation. Ann. Biol. Clin. 2011, 69, 393–403. 10.1684/abc.2011.0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wretlind B.; Pavlovskis O. R. Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase and its role in pseudomonas infections. Rev. Infect Dis. 1983, 5, S998–S1004. 10.1093/clinids/5.Supplement_5.S998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett M. J.; Davies D. T. Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase (LasB) as a therapeutic target. Drug Discov Today. 2021, 26, 2108–2123. 10.1016/j.drudis.2021.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zupetic J.; Peñaloza H. F.; Bain W.; Hulver M.; Mettus R.; Jorth P.; Doi Y.; Bomberger J.; Pilewski J.; Nouraie M.; Lee J. S. Elastase Activity From Pseudomonas aeruginosa Respiratory Isolates and ICU Mortality. Chest. 2021, 160, 1624–1633. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdino A. C. M.; Viganor L.; de Castro A. A.; da Cunha E. F. F.; Mello T. P.; Mattos L. M.; Pereira M. D.; Hunt M. C.; O’Shaughnessy M.; Howe O.; Devereux M.; McCann M.; Ramalho T. C.; Branquinha M. H.; Santos A. L. S. Disarming Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence by the Inhibitory Action of 1,10-Phenanthroline-5,6-Dione-Based Compounds: Elastase B (LasB) as a Chemotherapeutic Target. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1701. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathcart G. R. A.; Quinn D.; Greer B.; Harriott P.; Lynas J. F.; Gilmore B. F.; Walker B. Novel Inhibitors of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence Factor LasB: a Potential Therapeutic Approach for the Attenuation of Virulence Mechanisms in Pseudomonal Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 2670–2678. 10.1128/AAC.00776-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J.; Cai X.; Harris T. L.; Gooyit M.; Wood M.; Lardy M.; Janda K. D. Disarming Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factor LasB by leveraging a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model. Chem. Biol. 2015, 22, 483–491. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobelny D.; Poncz L.; Galardy R. E. Inhibition of human skin fibroblast collagenase, thermolysin, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase by peptide hydroxamic acids. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 7152–7154. 10.1021/bi00146a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett M. J.; Davies D. T.; Leiris S.; Sprynski N.; Llanos A.; Castandet J. M.; Lozano C.; LaRock C. N.; LaRock D. L.; Corsica G.; Docquier J.-D.; Pallin T. D.; Cridland A.; Blench T.; Zalacain M.; Lemonnier M. Chemical Optimization of Selective Pseudomonas aeruginosa LasB Elastase Inhibitors and Their Impact on LasB-Mediated Activation of IL-1β in Cellular and Animal Infection Models. ACS Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 270–282. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullagar J. L.; Garner A. L.; Struss A. K.; Day J. A.; Martin D. P.; Yu J.; Cai X.; Janda K. D.; Cohen S. M. Antagonism of a Zinc Metalloprotease Using a Unique Metal-Chelating Scaffold: Tropolones as Inhibitors of P. aeruginosa Elastase. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 3197–3199. 10.1039/c3cc41191e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner A. L.; Struss A. K.; Fullagar J. L.; Agrawal A.; Moreno A. Y.; Cohen S. M.; Janda K. D. 3-Hydroxy-1-alkyl-2-methylpyridine-4(1H)-thiones: Inhibition of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence Factor LasB. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 668–672. 10.1021/ml300128f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voos K.; Yahiaoui S.; Konstantinović J.; Schönauer E.; Alhayek A.; Sikandar A.; Chaib K. S.; Ramspoth T.; Rox K.; Haupenthal J.; Köhnke J.; Brandstetter H.; Ducho C.; Hirsch A. K. H. N-Aryl-2-iso-butylmercaptoacetamides: the discovery of highly potent and selective inhibitors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factor LasB and Clostridium histolyticum virulence factor ColH. chemRxiv [Preprint] 2022, 10.26434/chemrxiv-2022-fjrqr. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kany A. M.; Sikandar A.; Haupenthal J.; Yahiaoui S.; Maurer C. K.; Proschak E.; Köhnke J.; Hartmann R. W. Binding Mode Characterization and Early in Vivo Evaluation of Fragment-Like Thiols as Inhibitors of the Virulence Factor LasB from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 988–997. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya C.; Walter I.; Yahiaoui S.; Sikandar A.; Alhayek A.; Konstantinović J.; Kany A. M.; Haupenthal J.; Köhnke J.; Hartmann R. W.; Hirsch A. K. H. Substrate-Inspired Fragment Merging and Growing Affords Efficacious LasB Inhibitors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202112295 10.1002/anie.202112295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya C.; Walter I.; Alhayek A.; Shafiei R.; Jézéquel G.; Andreas A.; Konstantinović J.; Schönauer E.; Sikandar A.; Haupenthal J.; Müller R.; Brandstetter H.; Hartmann R. W.; Hirsch A. K. H. Structure-Based Design of α-Substituted Mercaptoacetamides as Inhibitors of the Virulence Factor LasB from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 1010–1021. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinović J.; Yahiaoui S.; Alhayek A.; Haupenthal J.; Schönauer E.; Andreas A.; Kany A. M.; Müller R.; Koehnke J.; Berger F. K.; Bischoff M.; Hartmann R. W.; Brandstetter H.; Hirsch A. K. H. N-Aryl-3-mercaptosuccinimides as Antivirulence Agents Targeting Pseudomonas aeruginosa Elastase and Clostridium Collagenases. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 8359–8368. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voos K.; Schönauer E.; Alhayek A.; Haupenthal J.; Andreas A.; Müller R.; Hartmann R. W.; Brandstetter H.; Hirsch A. K. H.; Ducho C. Phosphonate as a Stable Zinc-Binding Group for “Pathoblocker” Inhibitors of Clostridial Collagenase H (ColH). ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1257–1267. 10.1002/cmdc.202000994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino N.; Powers J. C. Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase. Development of a new substrate, inhibitors, and an affinity ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 1980, 255, 3482–3486. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)85724-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. A.; Mortin L. I.; Vanpraagh A. D.; Li T.; Alder J. Inhibition of daptomycin by pulmonary surfactant: in vitro modeling and clinical impact. J. Infect Dis. 2005, 191, 2149–2152. 10.1086/430352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluorescence Microscopy of Living Cells in Culture Part B. Quantitative Fluorescence Microscopy—Imaging and Spectroscopy. Methods Cell Biol. 1989, 30, 1–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges L. F.; Taboga S. R.; Gutierrez P. S. Simultaneous observation of collagen and elastin in normal and pathological tissues: analysis of Sirius-red-stained sections by fluorescence microscopy. Cell Tissue Res. 2005, 320, 551–552. 10.1007/s00441-005-1108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhayek A.; Abdelsamie A. S.; Schönauer E.; Camberlein V.; Hutterer E.; Posselt G.; Serwanja J.; Blöchl C.; Huber C. G.; Haupenthal J.; Brandstetter H.; Wessler S.; Hirsch A. K. H. Discovery and Characterization of Synthesized and FDA-Approved Inhibitors of Clostridial and Bacillary Collagenases. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 12933–12955. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J.; Wen S.; Cao W.; Yue P.; Xu X.; Zhang Y.; Luo L.; Chen T.; Li L.; Wang F.; Tao J.; Zhou G.; Luo S.; Liu A.; Bao F. Lung organoids, useful tools for investigating epithelial repair after lung injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 95. 10.1186/s13287-021-02172-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunniff B.; Druso J. E.; van der Velden J. L. Lung organoids: advances in generation and 3D-visualization. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 155, 301–308. 10.1007/s00418-020-01955-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprott R. F.; Ritzmann F.; Langer F.; Yao Y.; Herr C.; Kohl Y.; Tschernig T.; Bals R.; Beisswenger C. Flagellin shifts 3D bronchospheres towards mucus hyperproduction. Respir Res. 2020, 21, 222. 10.1186/s12931-020-01486-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. JY.; Loh J. M. S.; Proft T. Galleria mellonella infection models for the study of bacterial diseases and for antimicrobial drug testing. Virulence 2016, 7, 214–229. 10.1080/21505594.2015.1135289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taccetti G.; Francalanci M.; Pizzamiglio G.; Messore B.; Carnovale V.; Cimino G.; Cipolli M. Cystic Fibrosis: Recent Insights into Inhaled Antibiotic Treatment and Future Perspectives. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 338. 10.3390/antibiotics10030338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatworthy A.; Pierson E.; Hung D. Targeting virulence: a new paradigm for antimicrobial therapy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 541–548. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey S.; Cheung G.; Otto M. Different drugs for bad bugs: antivirulence strategies in the age of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2017, 16, 457–471. 10.1038/nrd.2017.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasko D.; Sperandio V. Anti-virulence strategies to combat bacteria-mediated disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2010, 9, 117–128. 10.1038/nrd3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theuretzbacher U.; Piddock L. J.V. Non-traditional Antibacterial Therapeutic Options and Challenges. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 61–72. 10.1016/j.chom.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M. J.; Dai B. Inhaled antibiotics therapy for stable non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a meta-analysis. Ther Adv. Respir Dis. 2020, 14, 1. 10.1177/1753466620936866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the Supporting Information.