Abstract

Objective

Integrated care and digital health technology interventions are promising approaches to coordinate services for people living with chronic conditions, across different care settings and providers. The EU-funded ADLIFE project intends to provide digitally integrated personalized care to improve and maintain patients’ health with advanced chronic conditions. This study conducted a qualitative assessment of contextual factors prior to the implementation of the ADLIFE digital health platforms at the German pilot site. The results of the assessment are then used to derive recommendations for action for the subsequent implementation, and for evaluation of the other pilot sites.

Methods

Qualitative interviews with healthcare professionals and IT experts were conducted at the German pilot site. The interviews followed a semi-structured interview guideline, based on the HOT-fit framework, focusing on organizational, technological, and human factors. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and subsequently analysed following qualitative content analysis.

Results

The results of the 18 interviews show the interviewees’ high openness and motivation to use new innovative digital solutions, as well as an apparent willingness of cooperation between different healthcare professionals. Challenges include limited technical infrastructure and large variability of software to record health data, lacking standards and interfaces.

Conclusions

Considering contextual factors on different levels is critical for the success of implementing innovations in healthcare and the transfer into other settings. In our study, the HOT-fit framework proved suitable for assessing contextual factors, when implementing IT innovations in healthcare. In a next step, the methodological approach will be transferred to the six other European pilot sites, participating in the project, for a cross-national assessment of contextual factors.

Keywords: Integrated care, digital health, IT-evaluation, health information system, implementation assessment, digital healthcare technology

Background

The increasing burden of chronic conditions introduces an important challenge for healthcare systems. Two of the most common chronic conditions worldwide are Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Chronic Heart Failure (CHF), which are both associated with high (re-) hospitalization rates and high mortality. 1 In 2019, the global prevalence of COPD is estimated to be about 10% among people aged 30–79 years old with highest prevalences found in western countries. 2 Also the prevalence of CHF is high, with 1–3% in the general population worldwide, with higher prevalences in central Europe (e.g. Germany: 3.9%). Prevalences are expected to further increase due to ageing of the population. 3 Patients suffering from these long-term conditions often experience impairments and limitations in their daily living and activities, because of symptoms such as shortness of breath or fatigue, which negatively impact their health-related quality of life. 4 In addition, these conditions require complex combinations of medications and non-pharmacological treatment approaches including lifestyle recommendations (e.g. smoking cessation), emphasizing the need for a holistic care approach. 5

To meet the healthcare needs of patients with advanced chronic conditions, integrated care is seen as an effective care model. It aims to enhance the quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare services. A key aspect of integrated care is to overcome fragmentation in the provision of health and social care, by coordinating services across different care settings and providers along the care pathway. Care is organized around the patient, respecting their needs and resources.6,7 Further key elements of integrated care that are relevant in the context of chronic condition management include integrated care programs, self-management support, patient education, case management, and individual patient care plans that consider the needs and preferences of the person, ensuring a tailored approach to chronic disease management. 8 Implementing these key elements, quality of life and health outcomes of people living with chronic conditions can be improved, and the progression of disease can be deaccelerated from its early stages.

Unfortunately, integrated care is not yet a common practice in many European countries. Especially in Germany, sectoral fragmentation is a common problem in health and social care provision. To address this challenge, integrated care networks were established, such as the widely known project Gesundes (“Healthy”) Kinzigtal GmbH. This is one of the leading managed care systems in Germany in which doctors, therapists, and hospitals, as well as pharmacies and other local authorities work together to provide patient-centred care. 9 Following this pioneer project, another integrated care network was established in North Hesse, Germany, in the beginning of 2019, named “Healthy Werra-Meißner-county” (GWMK).

Just like the Gesundes (“Healthy”) Kinzigtal, the GWMK is a managed care system dedicated to improving care provision and overall health of the Werra-Meißner county's population. Their approach involves coordinated care and health management, fostering patient self-management, and fostering a closer collaboration among health and social professionals to deliver patient-centered care. 10

In addition to the positive effect of integrated care, patients with progressive advanced chronic conditions can greatly benefit from digital health technologies or solutions. These can help to improve or maintain their health, avoid exacerbations of disease, extend their independence, optimize health resources utilization, and improve their self-management.11,12

Digital health is often characterized as technologies that improve care delivery in the sense of supporting the planning, organization, and coordination of care within and across organizations. As such, health technologies are seen as a driver to improve clinical outcomes and digital health technology interventions play an essential role to overcome sectoral fragmentation.13,14 Digital health technologies comprise a variety of electronic tools, systems, applications, platforms, and devices that can be used to collect and manage health data, to monitor and track health information, or to enable communication between patients and providers.

With care planning being a key aspect of integrated care, digital solutions, like care management platforms, can support the development and monitoring of care plans and thus improve the delivery and continuity of care. 15 Delivery of care can also be supported by clinical decision support systems that can increase patient safety and clinical management by complementing healthcare providers in patient care and decision-making. 16 Besides these physician-centred solutions, mobile or web-based portals can support the communication between different care providers and between patients and providers. It can also positively influence patient empowerment and health-related quality of life, which can have a positive influence on disease progression. 17

The combined effort of digital health innovations and integrated care to tackle the major health challenges of chronic conditions in the Werra-Meißner-County was the main reason for GWMK to join the EU-funded ADLIFE project. The ADLIFE project (ADLIFE stands for “Integrated personalized care for patients with advanced chronic diseases to improve health and quality of life”) running from 2020 to 2024 focuses on digital health innovations in the context of integrated care for patients with advanced chronic conditions (registered in Clinicalrials.gov with the Identifier: NCT05575336). The main aim of the project is to provide coordinated, anticipated, and personalized integrated care for people with COPD and/or CHF over 55 years of age, in order to increase the patients’ quality of life, reduce suffering and accelerate recovery from exacerbations of the disease. A digital toolbox, containing various digital health solutions, will be implemented and evaluated in seven different pilot sites in Spain, UK, Sweden, Denmark, Israel, and Germany. The toolbox contains novel digital health platforms which include (1) a personalized care plan management platform (PCPMP), (2) a patient empowerment platform (PEP), and (3) clinical decision support services (CDSS) (see Textbox 1).18,19

Text box 1.

Components of the ADLIFE Toolbox.

PCPMP – Personalized Care Plan Management Platform

In the PCPMP, personalized care plans are developed, updated, and managed by multidisciplinary care teams. Care plans detail the type of care the patient needs including health goals, activities/interventions, and education material. They are updated according to patient's changing needs and are informed by the CDSS. The PCMP shares the care plan with the PEP.

PEP – Patient Empowerment Platform

The PEP presents the care plan including the goals and activities to the patients through user friendly interfaces. It provides the opportunity for care plan management directly involving the patient and their caregivers. The PEP also provides mechanisms to enable asynchronous messaging between patients and medical professionals, to collect patient-reported outcomes (PROMs), medical device data, and context information (e.g. stress, mood level) to continuously collect feedback from the patients on their own health and to monitor risks. It also provides educational materials and a patient forum to get in contact with other patients.

CDSS – Clinical Decision Support Services

CDSS will be implemented in the PCPMP for (a) functional status and needs assessment of the patients and the caregivers; (b) offering personalized treatment goals and activities based on clinical guidelines and most recent context of the patient; and (c) predicting changing clinical status and needs of the patient, preventable events such as hospital admissions so that personalized care plan and interventions can be adapted accordingly. Data sources of CDSS include registered information on electronic health records and patient-reported outcomes (PROMs).

The findings of ADLIFE have the potential to be scaled-up from large pilot sites to routine practice. However, it is well known that the transfer from interventions that succeed in one area can fail when applied to other contexts and settings. It has been estimated that as many as two-thirds of change implementation initiatives fail, with barriers manifesting at several levels (e.g. patient, organizational level, and market/policy levels). The reason for this is that contextual factors are often insufficiently integrated into change efforts which negatively impact implementation success and scalability.20–23 Hence, an understanding of the key contextual factors relevant for the translation of the innovation into routine practice is of major importance when implementing digital health innovations. 24

Contextual factors can be defined as “the set of characteristics and circumstances or unique factors that surround a particular implementation effort”. 25 However, definitions of context within healthcare implementation research vary, as well as the methods on how context is assessed. A qualitative assessment approach which is supported by a comprehensive framework is recommended. 26

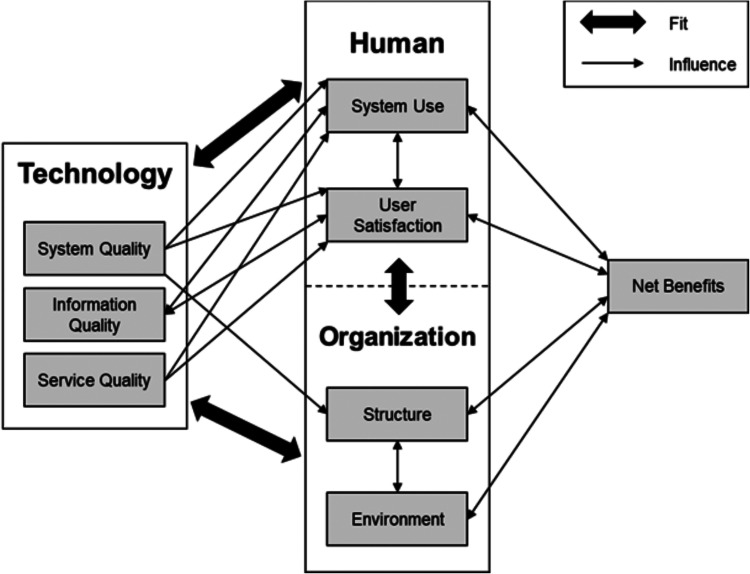

One framework, which captures contextual factors and helps to monitor health technology implementations, is the HOT-fit framework, which is used for this study. 27 The framework allows an assessment of external environmental factors, characteristics of the health organization or health system, characteristics of the innovation or intervention, and the implementation process. It is based on the “information system success model” and “Information Technology (IT) organization Fit models” and addresses three dimensions: human, organization, and technology. A common alignment of these dimensions, the “fit”, is crucial for successful implementation. 28 The three central dimensions of the HOT-fit framework are supplemented by eight subdimensions that are related to successful health information system (HIS) implementation. The impact of an evaluated system, as well as the positive and negative effects of it on the users, are assessed in the dimension “Net benefit”, which could be considered as overall performance. The dimensions and sub-dimensions have different relationships and influences with each other, as shown in Figure 1. The better the three dimensions of humans, organization, and technology are aligned, the higher the achievable potential of the clinical IT application. 27

Figure 1.

HOT-fit framework according to Yusof et al. 27

To obtain an in-depth understanding of contextual factors that are relevant when implementing the ADLIFE digital health platforms into routine practice, this study conducted a qualitative assessment and an analysis of contextual factors prior to the implementation of the ADLIFE digital health platforms at the German pilot site. The study describes the status quo of technological, human, and organizational contextual factors and elicits and contrasts different views, experiences, and requirements of different health care professionals working with digital systems in patient care. The results of the assessment are then used to derive recommendations for action for the subsequent implementation, and for evaluation of the other pilot sites.

Methods

A qualitative data collection approach using semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders involved in the ADLIFE was applied. This qualitative interview study was conducted prior to the implementation of the ADLIFE digital health platforms. For quality assurance, the COREQ checklist for reporting qualitative research was considered [see supplementary material 1 for the COREQ checklist]. 29

Setting and participants

To recruit participants a purposive sampling method was applied at first and supplemented with a snowball sampling method to recruit additional participants. Purposeful sampling is often applied in qualitative research, to recruit subjects who are available to the researcher. One type of purposive sampling is the snowball sampling, where the selected subjects are asked if they can recommend other cases for the study, making it an efficient and cost-effective method to identify interviewees. 30

In this study, different stakeholders were of interest who are relevant for the ADLIFE care concept and the later implementation of the platforms. This included three main groups: (1) healthcare professionals (general practitioners (GPs) working in outpatient practices, physicians/medical doctors, and nurses working in a hospital), (2) managers/the clinic CEO, and (3) the IT staff.

Following the purposive and snowball sampling method, these stakeholders were directly approached and recruited from the local hospital and primary care practices, as well as from the regional integrated care network GWMK in the Werra-Meißner-county in northern Hesse, Germany, which acts as the German pilot region for the ADLIFE project. Stakeholders were included in the study, if they were potential users of the digital platform or if they were important for the process of the implementation and execution of the project and were interacting with patients diagnosed with COPD or CHF, as ADLIFE focuses on these two diseases. Therefore, stakeholders were mainly recruited from pulmonology and the cardiology departments. Also, these stakeholders should be familiar with the IT infrastructure and/or used digital systems in patient care and had to agree to participate in the interviews. People who did not meet these inclusion criteria were excluded from the study. Invitations to participate were sent out via e-mail or stakeholders were invited personally in telephone calls or face-to-face. After gathering the data, participants were asked if they know other people who would be willing to take part in the research.

Data collection

The HOT-fit framework, as a health information system (HIS) evaluation framework, was used to conceptualize this study. 27 Each of the subdimension of the framework is associated with various evaluation measures. For example, “database” and “ease of use” are evaluation measures for the subdimension system quality or “motivation to use” and “attitude” are examples for evaluation measures of the subdimension system use. 27 Based on these measures, questions for the semi-structured interview guidelines were developed. It needs to be noted here that since the assessment was conducted before the implementation of the ADLIFE digital health platforms, not all measures were relevant. In addition to the interview questions derived from the evaluation measures, questions directly focusing on the ADLIFE project were added, to also assess the thoughts, concerns, and expectations in relation to the ADLIFE project. Interview questions were drafted, refined, and finalized in two internal team workshops [see supplementary material 2 for an overview which interview questions derive from which evaluation measure, subdimension and dimension]. Hence, three slightly different interview guidelines were developed to address the different stakeholder groups (Healthcare professionals, managers/the clinic CEO, IT staff). The interview guide started with a short introduction followed by the main questions to find out more about clinical workflows, the existing technical infrastructure, governance, and structure of the organizations as well as the motivation and willingness of participating persons to use the ADLIFE toolbox [see supplementary material 3 for interview guidelines].

The interviews were conducted by a postgraduate research assistant (master's level), trained in qualitative interviews, and were conducted between November 2020 and February 2021 using the web conferencing tool “Zoom”. The tool offers a video and image function, as well as a recording option for later data analysis. 31 Interviews were only conducted if interviewees provided a written informed consent. In preparation for the interviews, participating stakeholders were provided with a brief information sheet about the ADLIFE project and the aim of the interview. Ethical approval for the ADLIFE project was obtained from the University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany, under the application number 23/2/21 in February 2021.

Data analysis

For the analysis, all interviews were transcribed with the help of the transcription program “Trint”. 32 The focus of the transcription was on the spoken content, thus, nonverbal cues (such as sighs, huffs, finger-snaps, sobbing, laughs) were not transcribed. After the transcription was completed, proofreading of each transcript was conducted and possible transcription errors (e.g. missing words) were corrected. Furthermore, all identifiable information such as names, places, etc. were pseudonymized.

The data were analyzed by the same person who conducted the interviews, using qualitative content analysis based on Kuckartz supported by the qualitative analysis program MAXQDA.33,34 Following this approach, a first coding system was deductively established based on the three main dimensions of the HOT-fit framework including the respective subdimensions (see Figure 1) and on one main dimension acknowledging the specific requirements of the ADLIFE project. This coding system was used to analyze all interviews in a first coding round. During the analysis process, further subcodes were developed according to the interview material if needed. These inductively developed subcodes were added to the coding system, resulting in a differentiated coding system with deductive and inductive codes and subcodes. This final coding system was applied to all interviews in a second coding round. The goal of the analysis was to filter out and compile content from the collected data that were relevant to assess the contextual factors.

Reliability of the coding system was assessed with an inter-coder analysis, in which 5 (28%) randomly selected interviews were analyzed by a second coder, using the developed coding system. The second coder was a post-doctoral senior researcher familiar with qualitative research methods. The first result of the inter-coder analysis showed an agreement of 43.72%. A detailed review of the analysis revealed that this low agreement was mainly caused by inconsistencies in coding whole paragraphs or single words, although raters used the same codes. After aligning these, a final agreement score of 93.13% was reached, with 115 codes and subcodes showing an agreement of the code assignment between the two raters, proving the coding system to be reliable.

Results

The sample included 18 stakeholders consisting of physicians, nurses, the hospital CEO, as well as the hospital CIO (Chief Information Officer) from the local hospital, general practitioners from four primary care practices, and social workers from the regional managed care system GWMK. Interviews lasted from 24 to 64 minutes with an average duration of 38 minutes. Five stakeholders refused participation because of lack of interest or time (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample description.

| Stakeholder /Profession | Recruited from/ Setting | Sex | N | ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical pneumologist | Hospital | Male | 1 | C5 |

| Clinical cardiologists | Hospital | Male | 2 | C3, C12 |

| Nurse (pneumology) | Hospital | Female | 1 | N3 |

| Nurses (cardiology) | Hospital | Female | 2 | N1, N2 |

| Cardiologist | Medical care center | Male | 1 | GP5 |

| Hospital CEO | Hospital | Male | 1 | C2 |

| Hospital CIO | Hospital | Male | 1 | C4 |

| Clinical pneumologist | Rehabilitation clinic | Male | 1 | C1 |

| General practitioner | Outpatient practices | Male | 4 | GP1-GP4 |

| Social worker | GWMK | Female | 4 | SW1-SW4 |

The final coding system consisted of 57 codes, including five main dimensions and 52 sub-codes [see supplementary material 4 for the coding system]. The main dimensions human, organization, and technology of the coding system corresponds to the HOT-fit framework and were supplemented with a main dimension of ADLIFE. With this coding system, 882 text paragraphs were coded in the 18 interviews.

The presentation of the results is based on the coding system developed and hence based on the dimensions of the HOT-fit framework. Quotes are presented to underpin the findings. To summarize the results, Table 2 provides a high-level overview of the results per dimension, and the topics that were mentioned, respectively.

Table 2.

High-level overview of results per dimension according to the coding system.

| Dimension | Key themes emerging from the analysis | Theme description |

|---|---|---|

| Technology | ||

| System Quality |

|

|

| Information Quality |

|

|

| Service Quality |

|

|

| Human | ||

| User Satisfaction |

|

|

| System Use |

|

|

| Organization | ||

| Structure |

|

|

| Environment |

|

|

| ADLIFE | ||

| Opinion about ADLIFE |

|

|

| Expected Benefits from the Project / Net Benefits |

|

|

| Requirements for the Project |

|

|

Technological factors

The topics raised in the technology dimension refer mainly to the availability and use of digital systems, such as systems to support patient care or decision support systems, the quality of information provided by HIS, and the existing IT support in the facilities.

System quality

Many processes, such as laboratory diagnostics, radiological reporting, or data archiving, have already been digitized in the participating hospital. The GPs interviewed also work mainly digitally, with all practices having a practice management system (PMS). However, there is a large heterogeneity in terms of the PMS used. Also, only two of the five GPs used PMS that can be connected to HL7 FHIR (Health Level 7 Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources), indicating that comprehensive interoperability does not exist in the German pilot region. HL7 FHIR is a next-generation interoperability standard which enables health data, including clinical and administrative data, to be quickly and efficiently exchanged. Despite the mostly digital way of working, paper-based processes are reported as well by a nurse:

“We work in parallel, yes, (…) because we still have patient records that are handled in paper form” (N2).

The exchange of radiological reports between external institutions and the hospital is one example for digital communication. The interface standard used between the different HIS is HL7. According to the hospital CEO (C2), a connection of further systems via HL7 FHIR is “absolutely no problem”. Hence, a possible connection of the HL7 FHIR-based ADLIFE platforms to the clinic infrastructure can be assumed.

Information quality

In the hospital, external medical records are often available in paper form and are only partially digitized. In connection with the non-digitized fever charts, which are used to document vital signs like blood pressure or to document prescriptions, this results in an inconsistent digital provision of patient information. A clinical cardiologist commented on this as follows:

“The problem is that we don't ‘live’ the fever chart in everyday life because we don't have a digital fever chart yet. This means that what medication is added during the inpatient course is not practically checked online, but only in the discharge process.” (C12)

Service quality

This subdimension refers to the quality of the existing IT support in the facilities. Therefore, a differentiation was made between internal (within the hospital) and external (in the outpatient sector) IT support. Employees of the hospital are satisfied with the internal IT support provided by the IT department in the hospital:

“As far as I can see, IT service is always very obliging, and they also try to ensure that it happens very quickly.” (N3).

Requests to the IT department are managed by a ticket system and their processing is possible through remote maintenance, which makes it easily accessible for all employees.

In the outpatient sector, GPs work together with external, mostly local, providers, especially for the provision of hardware, or with the respective providers for software support. Long waiting times when having acute issues is one reason for dissatisfaction, as a GP reports:

“Let's put it this way: I would say that we need external help with the system once or twice a quarter of a year. But the help sometimes takes one or two days until something comes. That's one point that I would wish for differently, of course.” (GP4)

Human factors

The topics, raised in the human dimension, refer to the general satisfaction with existing HIS and on the use of the system regarding the digital skills of the interviewees, as well as their readiness and willingness to use existing and future HIS. The subdimension system use also includes topics related to views on digitalization and data protection.

User satisfaction

In general, healthcare professionals in the hospital are satisfied with the existing HIS:

“(…) on the whole, I think it's okay. It doesn't run particularly fast, I have to say. Overall, however, it is relatively stable” (C3)

Dissatisfaction with the HIS arises among the GPs primarily regarding acquisition and operating costs:

“They offer support tools, external billing tools, everything again with extra costs. I don't use all that at all and I don't really need it. And that is becoming more and more in the last few years. (…) The costs are rising, the complexity is increasing, but the benefits do not always increase as a result.” (GP1)

Three GPs are fully satisfied with the functionality of their PMS:

“Well, the basic system is good, I would say. So, I am already satisfied. There are definitely worse practice management systems. But I think I have chosen the right one.” (GP2)

System use

All interviewed GPs rate their digital skills as good and feel confident in using the digital systems and the functions they need:

“I would say that using them is not a problem. Most things are self-explanatory, even if sometimes you must search a bit in the depth of the submenus. But at the end of the day, dealing with it is routine somewhere.” (GP1).

Similar statements were made by other healthcare professionals of the hospital. In contrast to that, the social workers partly reported uncertainties in using the digital systems, especially when they are used to communicate with patients:

“I think it's good that you can use it in such a simplified way. But I don't know if I could just initiate it now.” (SW3)

In terms of the willingness of the hospital staff to use existing HIS, the hospitaĺs CIO notes difficulties shortly after implementation of new HIS, with the staff continuing to use paper records instead of the newly implemented digital documentation tool.

“And if I now say that we digitally map a lot or most of it, then that is also theory, a little bit. What is then ultimately practiced on the ward or in the areas looks quite different. That depends on the people.” (C4)

Regarding future potential digital systems that can be implemented, clinicians at the hospital would like to see more intensive data exchange between inpatient and outpatient sectors through a digital portal, as well as through the availability of data collected by the patients themselves. In addition, the clinicians would appreciate a clinical decision support system including therapy schemes, standard medication, and laboratory diagnostics. GPs were similarly positive about a possible clinical decision support system, but pointed out that the associated alarm function should not be too intrusive.

“It always depends on how, let's say, intrusive it is. Our PMS always provides up-to-date information as a pop-up, also based on guidelines. If a diagnosis, e.g. atrial fibrillation, is entered, it calls up risk factors and so on at the bottom of the screen. But that can also be a bit annoying in the long run. So, I think it would be better if you get that on demand, but not constantly pushed on your nose in such a system.” (GP1)

In addition, it was emphasized that healthcare professionals should still be able to actively decide on the medical treatment, to limit the risk that users relay too much on “the digital assistant (…)” (GP3).

Nurses of the hospital raised concern about older colleagues who might be critical of digital health innovations because they “might not want to support changes in their last years of work” (N1). But the nurses are also open minded about future HIS:

“Personally, I would find that good. Then you have everything in one. Now you have it twice - paper and digital” (N1).

However, it was pointed out that the implementation of HIS should not be too time-consuming and that nurses should not be distracted too much from their occupation. This assessment of the willingness of staff to use potential systems is also shared by the hospital's CIO:

“Change is always such a thing. Some are very open to the whole thing. This is always reflected in the projects, if you implement something now. You must have someone who accompanies these things in a relatively sustainable way. That hasn't really been the case with us in the past.” (C4).

According to the CIO, committed and interested key users, as well as a project commitment at the level of the chief physician can facilitate the implementation of a system to improve patient care. However, as also mentioned by the hospital CEO, the implementation process needs guidance and support. Also, other healthcare professionals like nurses and social workers are open minded towards digital health platforms.

The interviews further revealed that in general all employees of the hospital are open-minded towards digitalization in the healthcare sector and consider an improvement of care through the use of HIS as possible.

“I think digitalization is necessary. It also has something to do with networking with other hospitals, with other departments, whatever. It's necessary and it also has advantages.” (N2).

The chief physicians see the advantages of digitalization in improved readability of data, flexible data access, digital archiving, the use of AI-based warning systems, and better possibilities to coordinate with other institutions. Thus, for them digitalization in healthcare offers a high potential for increasing the quality of patient care. In contrast to the positive views on digitalization in the healthcare system reported by clinicians working in the inpatient sector, some of the interviewed GPs working in the outpatient sector are more critical towards digital approaches in the German healthcare system.

“My main concern about digitalization is always that it should actually make the work easier and not complicate it further. And that's a bit of what you unfortunately see (…) in recent years.” (GP1)

Apart from that, data protection is seen by many of the stakeholders interviewed, as a nuisance or obstacle in relation to their work. The data protection regulations are insufficiently practicable and complicate the implementation of digital projects.

“From my point of view, data protection in Germany is perhaps a bit exaggerated. If it goes so far that data protection hinders more than it helps, then at some point it becomes too much.” (GP1).

At the time of the interview, the interviewed stakeholders have confidence in the data protection measures in their respective institutions and see themselves as sufficiently protected. However, they admit that as laypersons they can only judge data security to a limited extent and must trust those responsible for it, the IT department or system provider.

Organizational factors

In terms of organizational factors, the topics raised by the interviewees refer mostly to structural processes and care processes within the respective institutions. Moreover, environmental aspects regarding existing collaborations in the region and the associated communication channels or data exchange methods were raised.

Structure

In the hospital, cardiological and pneumological patients are treated according to internally defined Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), which are based on S3 treatment guidelines. The S3 guidelines have the highest quality level for guideline development, considering both a systematic appraisal of the published evidence as well as the clinical experience of a large group of stakeholders. 35 However, after discharge from the hospital cardiological patients might suffer from inadequate outpatient follow-up in the pilot region.

“It would be cool or good to have a proper interface in terms of outpatient follow-up. And that is not optimal in rural areas, I think. Probably in urban areas it is sometimes a bit problematic too. But in our case - due to the low specialist density and the high proportion of patients - extremely difficult to manage.” (C12)

The integrated care network GWMK, who acts as the German pilot site of ADLIFE, aims to achieve a better outpatient follow-up by improving the cooperation between healthcare professionals in the region and to strengthen the preventive care approach for people with chronic conditions. Members of the network, especially the hospital, hopes that this overall approach will improve patient care pathways and shifts more inpatient processes and treatments to the outpatient sector. This approach also corresponds with the hospital's general strategy on expanding and restructuring the outpatient clinics. The hospital's CEO emphasized that this strategy does not mean that they want to compete with the outpatient sector:

“As long as the GPs also do their part and fill their seats, we would interfere less. They are our most important referrers. We don't really want to interfere. That's not what the GPs want either. But of course, we have to reorganise our outpatient business in the hospital so that we can present it better from an economic point of view.” (C2)

All respondents across all stakeholder groups stated that they were satisfied with the hospital's strategy regarding digital based patient care. At the same time, some employees state that they do not feel sufficiently involved in the selection of digital solutions and would like to be more involved in the decision-making process:

“Well, I personally would say that it would have been desirable for us to have seen something beforehand, how it is planned. (…) It is always a pity when it comes ready-made and then we are presented with it. I'll say it's unpleasant and I would have liked to be asked beforehand. (…) But that was not the case.” (N2)

However, from the CIO's point of view, it was difficult to gain committed users to accompany the implementation of digital platforms in previous projects and that new digital introductions were not used. From the experience of the CIO, the medical management level should be responsible for implementations helping to shape and exemplify the implementation.

Environment

A cooperation in the inpatient sector between the regional hospital and a nearby university hospital in cardiac surgery and pneumology exists. However, there is no cooperation or digital connection between the hospital's cardiological and pneumological department with the outpatient sector. Also, within the outpatient sector, cooperation is not clearly organized. However, the communication and professional exchange between GPs is described as positive and extensive:

“I think this is not so bad here. I don't have the feeling that we have such a huge communication problem. What is missing at the moment in times of COVID-19 is a bit of personal exchange. (…) That's a bit of a disadvantage, but otherwise the communication actually works.” (GP1)

In the outpatient (i.e. primary care practices) and inpatient sector, existing communication channels between the physicians and other providers include phone and postal mail. When communicating by phone, the lack of accessibility is often criticized. Communication, by e-mail, has rarely taken place so far. Patient data or patient medical records are mainly exchanged by letters sent by postal mail or fax. Digital data exchange only takes place within the inter-clinic cooperation, in the inpatient sector.

In the future, the telephone should remain as a means of communication, but according to the interviewees, communication by e-mail should be greatly expanded and communication by fax should be reduced.

“It would be wonderful, of course, or much much better, if you could write an e-mail. It would also be better for the clinical colleague. He would not be disturbed in his work. He could work on it when he has time. But as I said, personal data by e-mail is not possible and that's why we have to do it by phone at the moment” (C1)

In addition, the interviewees would welcome an increased communication by digital platforms, such as asynchronous messengers or web conferences. Communication between healthcare professionals – including social workers – and patients mainly takes place during personal contacts within the respective facility. Outside of the hospital, practices and other facilities, the healthcare professionals and patients communicate by phone.

Based on the limited communication between healthcare professionals, they also mentioned problems with cross-sectoral care in the pilot region which results in a fragmented and no continuous provision of care for patients with chronic conditions. In addition, fragmentation may increase in the future, as practices of specialists and general practitioners are closing because the retiring physicians do not find successors. Thus, the provision of care will become increasingly difficult. To achieve efficient and cross-sectoral patient care, care must be restructured to include all professions. However, the clinic management fears a sectoral mindset and closed-mindedness among the GPs and sees itself in a conflict between the need for restructuring care and maintaining a good relationship with the referring physicians.

Specific topics in relation to the ADLIFE project

The topics coded in relation to specific implementation factors associated with the ADLIFE project address the views of interviewees on the project itself, concerns and worries related to the implementation and use of ADLIFE digital platforms, main requirements for the implementation and expected benefits in patient care, and communication/cooperation between healthcare professionals when using the ADLIFE digital platforms.

Opinion about ADLIFE

Most stakeholders from all interviewed groups – hospital staff, GPs, social workers – consider ADLIFE to be a sensible concept that can be realistically implemented and that is expected to improve patient care in the rural pilot region in the future. From the point of view of interviewees, the prerequisite for this is that the implementation is co-designed, that ambiguities in the process design are clarified in advance, and that a willingness to communicate with other healthcare professionals exists. The hospitaĺs CIO is concerned that thorough the implementation of the project, parallel structures might be set up, which would result in using more than one system:

“Of course, it is a good thing in principle when the partners in the healthcare network work with each other. I see that as very positive. What is important is that you don't set up parallel structures with the matter or the project.” (C4).

This is also related to the concern of most interviewees that the project and the use of the digital health platform might lead to too much additional work. It is important that the benefits for the main users (i.e. healthcare professionals and patients) are greater than the effort of using it, as GP1 explains:

“So if the project actually only makes more work - that was one of the sticking points at the time: what only makes more work but does not really bring relief. Then a whole platform is of no use.” (GP1).

Hence, it is necessary to integrate the ADLIFE digital platforms into the daily work routine as best as possible, to generate a positive added value and to reward the workload accordingly. Also, the handling of the ADLIFE digital platforms should be as easy as possible. In addition, a too detailed administrative effort, a high frequency of use, and a too complex connection of the PCPMP platform to the existing system structure would reduce the users’ trust in the ADLIFE project.

Apart from that, the interviewed healthcare professionals were concerned about the digital skills of the mostly elderly patients in using digital health platforms. The overall opinion was that the older the person, the less pronounced the digital skills.

“I think it becomes difficult with increasing age. But I think that you can still try, because in the end people are actually (…) likely to learn and also capable of doing so. And in the meantime, the hurdle to use something like this is no longer so high. Because I think it has become relatively simple. That it is low-threshold.” (GP4)

However, the experience of the physicians also shows that these prejudices do not apply to all older patients and that some do have sufficient digital skills. Also, this problem will solve over time as future generations are likely to become more digitally affine.

Another possible obstacle to use of the ADLIFE digital platforms is related to the data protection regulations.

“And where I always have a bit of concern in Germany is that data protection is a huge issue. (…) Who is allowed to see what and who is not allowed to see what? That's a big field. (…) I don't know enough about the legal side of it. But I see that as a bug that could make the whole thing more difficult.” (C3)

From the participating stakeholders' opinions, it must be ensured that the treatment of patients via the health platform is legal in the sense of remote treatment and that those providing treatment do not have to expect personal liability. In addition, the collection and exchange of patient data between the physicians could only take place with the patients’ consent. The interviews revealed fears of a complex data regulation process to fulfil this requirement.

According to the management of the hospital, the fragmented supply of healthcare could also lead to problems in implementing and using the ADLIFE digital platforms. Close cooperation with GPs and an active participation of the outpatient sector needs to be key when successfully implementing the digital health platforms.

“Yes, it is important that you get the GPs on board very early and take them along when such a platform comes along. They are always a bit afraid of losing patients, also in terms of patient flows. Understandably, they want to be there for their patients as family doctors and are a bit worried that they will lose them to a purely specialised system and no longer see them.” (C12)

Expected benefits from the project

The independent collection of vital data through wearables is seen as an expected benefit of the ADLIFE project which offers great potential for the treatment of patients with chronic conditions, the improvement of preventive therapy planning, the early detection of deterioration, with a positive impact on patients’ quality of life.

Another expected benefit is related to the new communication possibilities such as asynchronous messaging or videoconferencing via the ADLIFE digital platforms. With these new possibilities, the healthcare professionals expect an increase in communication between different healthcare professionals across different organizations and thus improved networking in the region. A similar effect can be expected in the communication between healthcare professionals and patients.

The goal of the digital ADLIFE digital platforms is a closer cooperation of all parties involved (i.e. providers, caregivers, patients) and improving empowerment and self-management of the patients to be actively involved in their care. According to some healthcare professionals, using the platform can not only facilitate this, but also requires interested patients who are willing to use it and adhere to lifestyle changes to increase or maintain their health status.

Through integrated control and reminder functions in the PEP, patients’ medication intake could be digitally monitored and adherence to the therapy plan could be improved by involving patients in the decision-making process. Also, GPs see a major benefit in facilitating the involvement of patients in their care.

“ I think the approach is quite good, actually, to do something and also to say to the chronically ill: ‘How can we involve you a little better and simply make sure that something doesn't just happen in the 10 min when you're sitting with me,’ but that we can put care on a broader footing.” (GP2).

Another key benefit that the healthcare professionals hope to achieve through ADLIFE is a better-informed patient through the information provided in the PEP. When patients are better informed and understand their disease better, the quality of the treatment is higher and quality of life increases. Nurses and physicians expect that once patients are more aware of their care plans compliance also increases which positively influences the care pathways.

Requirements for the project implementation

A key requirement, of the hospitaĺs physicians and the GPs, is to avoid a flood of generated data though the digital health platforms, which would lead to confusion and prevent reliable data evaluation. A better approach would be to select and collect specific parameters that are relevant for the disease. Otherwise, there is a risk of disinterest from the potential users.

To additionally reduce the effort to interpret the data and the number of alert messages, the interviewees said that it should be possible to define limits for patients’ vital signs, which are monitored by the CDSS and thus assume a kind of triage function. In addition, it should be ensured that the data collected (clinical and self-reported data such as PROMs) are shown in a user-friendly way to allow for a quick assessment of the patient's health status. Further requirements for the CDSS include corrective mechanisms for medication dosing and automatic availability of treatment regimens.

When providing information material to patients about the PEP, the interviewees highlight that it should be additionally ensured that the content is not only formulated in a low-threshold and easy-to-understand way, but also visualized as much as possible, e.g. in the form of videos, to further increase the use of the PEP and patients’ empowerment.

In terms of usability of the digital health platforms, all stakeholders agree that the platforms must be intuitive and easy to use for all users, especially for patients, regardless of their level of education. To facilitate the use of the digital health platforms, the interviewees mentioned that training is needed to become familiar with the digital platforms. Also, relatives or other caregivers should be included in the training to guarantee long-term support.

Defining responsibilities and determining which group of healthcare professionals will take the lead in caring for the patients within the framework of ADLIFE, is also seen as a key requirement. Although it was emphasized that the distribution of responsibilities should be discussed jointly, the GPs or the clinic should ultimately be responsible for the care of patients. In addition, the interviewed healthcare professionals support the idea to also include other healthcare professions in the treatment and that care does not have to be provided exclusively by medical staff, but could also be provided by specially trained non-medical professionals who operate the digital health platforms and communicate with patients:

“(…) So, a kind of heart failure nurse, for example, who provides outpatient follow-up care and digital support. I think that would be a good concept. A doctor doesn't necessarily have to be the first point of contact. (…) But such a platform, which is primarily operated by a heart failure nurse or a nurse who is experienced, I think would work well.” (C12).

In the interviews, the healthcare professionals also mentioned possible ideas for the process design of the project. According to two clinicians (C5 and C1), a mutually defined appointment prioritization could be established based on collected vital signs and the treatment plans to assign patients to inpatient or specialist care according to urgency. In addition, the time intervals or the necessity of medical examinations could also be made dependent on the evaluation of the digitally collected vital parameters. With that, deteriorations can be detected at an early stage and unnecessary visits to the doctor's office could be avoided. In this way, the redesigned processes could relieve the burden on emergency departments and practices:

However, main requirement for a successful implementation remains the integration of ADLIFE digital platforms into the care process to ensure complete patient care:

“You also have to align your daily workflow with the fact that you're still dealing with those platforms. Otherwise, it's going to get lost.” (C12)

Discussion

Based on the view of 18 healthcare professionals and IT experts from the German pilot site, the implementation of the ADLIFE digital platforms will be a complex process that requires organizational, technical, and human changes. However, once conditions are established, the interviewees anticipate the ADLIFE digital platforms to be of great benefit in supporting patient-centred care from the both the patients’ and healthcare professionals’ perspective and are very open-minded towards the digital developments in healthcare. The interaction of organizational processes, technological infrastructure and human actions and the fit between these individual aspects are key for a successful implementation of health technologies.36,37

Technology dimension

A central technological aspect, for the success of digital health platforms, is interoperability. 38 However, infrastructure and processes facilitating comprehensive interoperability seems to be lacking in the pilot region. The results further showed that there is a large heterogeneity in terms of systems and software providers and there are no legal requirements regarding interface standards, which leads to different media being used (e.g. paper and electronic documentation). Hence, for the successful implementation of the ADLIFE digital platforms it should be examined whether a technical interface for integration can be created for practices with PMS without HL7 FHIR capability or whether the creation of parallel structures is accepted. Assuming technical feasibility, the development of a technical interface requires external expertise and is associated high development costs. 39 If this integration cannot be achieved due to technical or financial reasons, ADLIFE digital platforms would in most cases have to be used as a parallel system without information exchange with existing PMS. The request of many interviewees was to prevent this because it would probably decrease the willingness to use the systems and negatively impact the satisfaction of the users.

An increase in interoperability could be achieved in the medium to long term, not only for the ADLIFE project but also for the entire German healthcare sector, through the further development of outdated standards and legally defined technical software and interface standards. 40 Further expansion of a reliable digital infrastructure is also required to improve the low information quality caused by the different media used (i.e. documentation on paper and electronically) which negatively impacts the user satisfaction. To ensure user satisfaction, the advantages of the systems and their functions should be made clear to the GPs.

Human dimension

With one exception, respondents already use digital systems in their daily work and thus reported to have sufficient digital skills to operate digital platforms in healthcare. Therefore, it can be concluded that sufficient skills are available to operate the ADLIFE digital platforms. Furthermore, it is expected, that digital competencies will expand in the future, as more and more new technologies will be used in the health care sector and healthcare professionals will constantly need to adapt their skills to new technologies. 41

However, having the ability to use and operate the platforms, does not necessarily mean that the staff is willing to use these in their daily work. Our results show that willingness to use new digital platforms exists, but the acceptance of these still unknown health platforms can remain difficult in the beginning of the implementation and strongly depends on the people. Concerns were mentioned that especially older colleagues might still use old structures (e.g. paper based). Since individuals are all different, as well as the tasks they need to conduct, a potential new IT system (like the ADLIFE digital platforms) requires flexibility when being implemented in different settings (e.g. outpatient care, different wards in a hospital). Also, the involvement of the potential users from the start of the development to the implementation is important for a successful implementation, to ensure that needs and abilities of different user groups are considered to improve IT adoption. 42 The users should also be offered user training and support throughout the implementation. In the ADLIFE project, the healthcare professionals will receive training before using the ADLIFE digital platforms. This includes group and one-to-one sessions, as well as written information.

Another possibility to facilitate implementation are clinical champions, which is a well proved concept when implementing changes in healthcare. Clinical champions typically drive the implementation effort by promoting the innovation and expressing optimism and confidence in an innovation.43,44 Identifying a clinical champion in the German pilot region will also help in successfully implementing the ADLIFE digital platforms. Also, the CIO of the local hospital in the current study emphasizes the usefulness of the platforms to facilitate uptake.

The interviewees emphasize that digital systems are useful to improve the quality of care by providing the possibility of communication, data exchange between the inpatient and the outpatient sector, and by providing guideline-based care via CDSS. A huge advantage of the ADLIFE digital solutions is that the CDSS is directly incorporated in the PCPMP, which can facilitate uptake and use of a CDSS in patient care, which was reported to be rather low in previous studies. 45 Since these interviews revealed a high acceptance of potential users to use the CDSS, no problems in relation to the uptake of the CDSS are expected in this study.

Data protection is mentioned as a barrier in implementing digital health innovations and the interviewees mentioned to have concerns about the feasibility of implementing ADLIFE with the existing data protection requirements in the context of Germany. However, data protection will always be ensured during the implementation of ADLIFE by a signed data protection agreement, a positive vote of an ethics board, and signed informed consent forms of the participating stakeholders. To encounter these concerns, prior to accessing and using the digital tools, data protection will be a topic in the planned training sessions for persons participating in the ADLIFE pilot.

Organisational dimension

Overall, the degree of cooperation in the pilot region between the inpatient and outpatient sectors can be classified as rather low, although the interest in coordinating care is high. As a result, there is no continuous patient care, especially for patients suffering from chronic conditions.

On a structural level, the role of the integrated care network GWMK facilitates continuous care with a targeted management of patient care pathways, prevention, and cooperation between healthcare professionals. The findings show that a good relationship between the different stakeholders in the pilot region exists, which is an important requirement for the implementation of the ADLIFE digital platforms and suggests a high willingness of communication and cooperation. However, communication channels and exchange of patient data vary between the inpatient and the outpatient sector reaching from personal interactions to e-mails or telephone. The use of informal communication channels, such as WhatsApp, by clinicians is also widespread. This is not only a phenomena in the pilot region, but also has been noted throughout Germany as well and shows the usage potential and acceptance for asynchronous messenger services in the healthcare sector. 46 If the messenger services are designed in accordance with data protection regulations, they could represent a more secure communication option, replace informal communication channels in patient care, and intensify the exchange between the providers as well as between providers and their patients. Once the ADLIFE platforms are implemented, these will provide the possibility to exchange direct messages between providers and between providers and patients.

Another major challenge in the region is the closures of practices, which also affects continuity of care. Due to practice closures and low specialist density in the pilot region, the need for increased efficiency and more intensive cooperation between service providers across sector boundaries has been claimed by the interviewees. The strategy of the hospital board regarding the avoidance of inpatient stays is evidence of an important mindset for improving the care situation in which revenue-relevant aspects are not the leading factor. The views and attitudes of the interviewees are in line with the goals of ADLIFE, so that it can be assumed that there is a willingness to cooperate extensively to relieve the providers in the region through efficient processes, to maintain a good quality of care and to be able to overcome the consequences of a shortage of specialists.

Specific topics in relation to the ADLIFE project

Overall, the interviewed healthcare professionals and IT staff are in favour of the ADLIFE project and consider the implementation of the ADLIFE digital health platforms to be feasible at the German pilot site with the given the technical, human, and organizational current conditions. They expect the digital health platforms to improve patient empowerment, communication, and cooperation between healthcare professionals and patients as well as between healthcare professionals themselves. Main concerns that were mentioned in the interviews relate to a higher amount of work, complicated implementation of the digital health platforms and implementation in daily work routines, complexity in using the platforms, and low willingness of patients to participate in the ADLIFE care concept. Furthermore, if sectoral thinking among care providers is still present it would limit the new cooperation forms between different care providers. These concerns are in line with other study findings, reporting that new IT systems will not be adopted if the system does not fit into the daily workflow of the physicians or if they feel that their professional autonomy is threatened by this. 47

Thus, for a successful implementation of digital technologies in healthcare, like the ADLIFE digital platforms, an active project team in which all key stakeholders are involved is essential. For the ADLIFE project this should include relevant decision-makers, local project coordinators, GPs, clinicians, IT staff, and nurses/nurse coordinators. Especially for the implementation of eHealth technologies in the health care setting, a multitude of stakeholders are often involved which can complicate the implementation and requires the need for an extensive stakeholder analysis and inclusion at an early stage. 48

Clearly describing responsibilities between the different healthcare providers that are involved in the ADLIFE care concepts (i.e. GPs, clinicians, nurses) is also important to ensure a successful implementation and later use of the digital health platforms. The clinicians interviewed in this study seem to be very flexible in their role, supporting the idea of including other healthcare professionals in the patient's care as well and are willing to delegate tasks to other healthcare professionals. With that, new ways of work organization can emerge, and the work will be much more horizontally organized, moving away from the traditional hierarchically organized work. Above that, new work processes and routines need to be developed to support the sustainable use of the new technologies, especially after the project ends. 37

Another barrier the interviewees see are the limited digital skills of older patients which would limit the use of the digital health platforms. However, findings of other studies show that older patients are not per se limited in their digital skills and are already using ICT.49,50 In general, competencies using ICT might differ and to ensure all patients an equal participation in the ADLIFE project a training on the use of the ADLIFE digital platforms should be offered. This can also increase the acceptance and the understanding of the benefits the ADLIFE digital platforms. 51 Beyond that, it should be ensured that all information presented in the ADLIFE digital platforms is shown in a patient-friendly way, facilitating the use of the platform.

Strengths and limitations

Numerous implementation science frameworks have been developed, in order to guide implementation processes. 52 However, these frameworks, which are widely applied to health system innovations, are not sufficiently specific to capture the characteristic challenges associated with information technology (IT) innovations in healthcare. The HOT-fit framework has this IT reference and was used in this study to facilitate data collection, analysis and presentation of the results. 27 It proved to be flexible and applicable for this study context, considering the assessment of contextual factors on different dimensions.

A limitation that needs to be mentioned here is related to the net benefits dimension of the HOT-fit framework, which usually represents the combined benefits of the technological, organizational, and human dimension. Since this study was conducted prior to the implementation of the ADLIFE digital platforms, the net benefits were incorporated in the subdimension “Expected benefits from the ADLIFE project” which represent expectations that are hypothetical in nature and not proven yet. The assessment of the net benefits dimension will become more important at the follow-up assessment after the implementation of the ADLIFE digital platforms. Furthermore, since this analysis was conducted during the software development phase and focused on the pre-assessment, an analysis on usability and practicability of the ADLIFE digital platforms was not feasible.

By interviewing different professional groups, a more differentiated data basis was achieved and views from different perspectives were incorporated in the analysis. Since this study focused only on the viewpoint of the professionals, patients were not considered in the present study. However, including the patient's perspective in the evaluation of digital health innovations is of major importance and will be included in the overall study evaluation.

The 18 interviews do not claim to be exhaustive but provided a suitable amount of data and high data quality, as the participating stakeholders addressed all interview questions in detail and in a targeted manner. After coding 14 interview transcripts, no more adjustments to the coding system were needed as only sporadic new information was gained. Hence, it can be assumed that increasing the number of interviews would not have yielded any new or different results, assuming data saturation was reached. A limiting factor refers to the recruitment of the interviewees, since participating stakeholders were included based on their availability and interest and were not randomly selected which might introduce a selection bias.

The development of a coding system through deductive and inductive category formation is widely used in qualitative research and has also proven to be successful in the present context. 33 The coding system developed within this study can be considered as highly differentiated, as the system has up to five levels of sub-codes which seemed appropriate for the research context. In addition, interrater analysis proved reliability of the coding system. Furthermore, since the coding system is based on the HOT-fit framework which can be applied at different stages of the research circle, it can also be used in the context of a follow-up assessment after the implementation of the ADLIFE digital platforms.

Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that on the technical level, there is a lack of data exchange and interoperability which negatively impacts the implementation of the ADLIFE digital platform. Neither outpatient players nor the community hospital is currently able to provide patient data via standardized processes. In addition, different practice management systems and patient data management systems are used that are not interconnected. The implementation of the ADLIFE digital platforms can be used as a starting point to tackle this because it will provide an interoperability platform based on international standards like HL7 FHIR which ensures compatibility with external practice management systems or electronic patient data management systems. Despite the technical challenges, healthcare professionals see a great benefit in the ADLIFE digital platforms and are highly motivated to use these. However, the successful implementation also requires an entire change management process. For ADLIFE this mainly includes to involve and engage all care providers at all levels from early stages on, to discuss and define roles and responsibilities of all persons involved and to integrate the new processes smoothly into the daily work by providing user trainings and adaptions to the local context. This corresponds with the factors for a successful and sustainable change management in the field of digital innovations in healthcare that have been identified by Hospodkova et al. 53

In addition to report on the status quo of human organizational and technological contextual factors at the German pilot site, this study serves as a pilot for the development of a cross-national approach to assess contextual factors at all other pilot site. In the next steps, the interview guidelines will be slightly revised to be applicable, and then assessed, in all ADLIFE pilot sites. 54 After the one-year pilot implementation of the ADLIFE digital platforms, contextual factors will then again be assessed in all ADLIFE pilot sites to evaluate knowledge, skills, and use of the ADLIFE digital platforms among healthcare professionals. The pre-assessment results will be compared with the post-assessment to derive recommendations for translation into routine practice and to improve scaling-up. This study might serve as an example on how an assessment and analysis of contextual factors can be embedded when designing and piloting digital healthcare innovations. Future research efforts in this field are encouraged to provide capacity for these kind of research activities, as the consideration of contextual factors on different levels is critical for the success of implementing innovations in healthcare and the transfer into other settings.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231222100 for “It depends on the people!” – A qualitative analysis of contextual factors, prior to the implementation of digital health innovations for chronic condition management, in a German integrated care network by Clemens Moll, Fritz Arndt, Theodoros N. Arvanitis, Nerea Gonzàlez, Oliver Groene, Ana Ortega-Gil, Dolores Verdoy, Janika Bloemeke and on behalf of the ADLIFE consortium in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076231222100 for “It depends on the people!” – A qualitative analysis of contextual factors, prior to the implementation of digital health innovations for chronic condition management, in a German integrated care network by Clemens Moll, Fritz Arndt, Theodoros N. Arvanitis, Nerea Gonzàlez, Oliver Groene, Ana Ortega-Gil, Dolores Verdoy, Janika Bloemeke and on behalf of the ADLIFE consortium in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-dhj-10.1177_20552076231222100 for “It depends on the people!” – A qualitative analysis of contextual factors, prior to the implementation of digital health innovations for chronic condition management, in a German integrated care network by Clemens Moll, Fritz Arndt, Theodoros N. Arvanitis, Nerea Gonzàlez, Oliver Groene, Ana Ortega-Gil, Dolores Verdoy, Janika Bloemeke and on behalf of the ADLIFE consortium in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-dhj-10.1177_20552076231222100 for “It depends on the people!” – A qualitative analysis of contextual factors, prior to the implementation of digital health innovations for chronic condition management, in a German integrated care network by Clemens Moll, Fritz Arndt, Theodoros N. Arvanitis, Nerea Gonzàlez, Oliver Groene, Ana Ortega-Gil, Dolores Verdoy, Janika Bloemeke and on behalf of the ADLIFE consortium in DIGITAL HEALTH

Acknowledgements

This work is a part of the ADLIFE project. The authors would like to thank all partners within ADLIFE for their cooperation and valuable contribution. Furthermore, we would like to thank all participating stakeholders for their time and contribution in the interviews. Also, we would like to thank the “Gesunder-Werra-Meißner Kreis GmbH” for providing the opportunity to conduct the interviews within the ADLIFE project.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: CM conducted the interviews and the analysis and was responsible for drafting the manuscript. FA assisted in recruiting the interviewees and assisted in the development of the interview guidelines. TA, NG, AOG, and DV provided important methodological input and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. OG oversaw the study and provided valuable input in developing the methodology and in editing the manuscript. JB led the overall study, assisted in the analysis and was the main contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. OptiMedis is a management company with the key aim to design, implement, and evaluate integrated care networks. GWMK is one of the care networks developed by OptiMedis and site for the pilot implementation of the ADLIFE toolbox. Authors CM, OG, and JB were employed by OptiMedis during the time of the study, author FA was employed by GWMK. The authors declare that they employment did not constitute a conflict of interest regarding the evaluation of the contextual factors associated with the ADLIFE implementation.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the ADLIFE project was obtained from the University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany, under the application number 23/2/21 in February 2021.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The ADLIFE project has received funding from the European Union under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 875209. No extra funding was received to develop this manuscript.

Guarantor: JB.

ORCID iDs: Theodoros N Arvanitis https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5473-135X

Ana Ortega-Gil https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9255-1560

Janika Bloemeke https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9886-9892

Supplementary materials: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 2129–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adeloye D, Song P, Zhu Y, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10: 447–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, et al. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res 2023; 118: 3272–3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogelmeier C, Buhl R, Burghuber O, et al. S2k-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Therapie von Patienten mit chronisch obstruktiver Bronchitis und Lungenemphysem (COPD), https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/020-006l_S2k_COPD_chronisch-obstruktive-Lungenerkrankung_2018-01.pdf (2018, accessed 19 May 2022).

- 5.Herkert C, Kraal JJ, Spee RF, et al. Quality assessment of an integrated care pathway using telemonitoring in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: protocol for a quasi-experimental study. JMIR Res Protoc 2020; 9: e20571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolte E, Pitchforth E. What is the evidence on the economic impacts of integrated care?, https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/251434/What-is-the-evidence-on-the-economic-impacts-of-integrated-care.pdf (2014, accessed 19 May 2022).

- 7.Gröne O, Garcia-Barbero M. Integrated care. Int J Integr Care 2001; 1. Epub ahead of print 2001. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouwens M. Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Qual Health Care 2005; 17: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groene O, Hildebrandt H, et al. Integrated care in Germany: evolution and scaling up of the population-based integrated healthcare system “healthy Kinzigtal”. In: Amelung V, Stein V, Suter E. (eds) Handbook integrated care. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021, pp.1155–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hildebrandt H. Über uns - Gesunder Werra Meißner Kreis, https://gesunder-wmk.de/ueber-uns/#was-wir-machen (2022, accessed 19 May 2022).

- 11.Edelmann F, Knosalla C, Mörike K, et al. Chronic heart failure. Dtsch Ärztebl Int 2018. Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koff PB, Min S, Freitag TJ, et al. Impact of proactive integrated care on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis J COPD Found 2021; 8: 100–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guldemond N, Hercheui MD. Technology and care for patients with chronic conditions: the chronic care model as a framework for the integration of ICT. In: IFIP international conference on human choice and computers, 2012, pp.123–133. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garg AX, Adhikari NKJ, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA 2005; 293: 1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laleci Erturkmen GB, Yuksel M, Sarigul B, et al. A collaborative platform for management of chronic diseases via guideline-driven individualized care plans. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2019; 17: 869–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutton RT, Pincock D, Baumgart DC, et al. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit Med 2020; 3: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]