Significance

Many sub-Neptune exoplanets are believed to have thick atmospheres dominated by hydrogen, surrounding the interiors with mainly silicates and oxides, assuming no reaction between them. From high-pressure experiments on molten magnesium oxide in a dense hydrogen liquid, we found that the reaction between hydrogen and the oxide melt results in the formation of hydride and water under the pressure–temperature conditions expected for the atmosphere–interior boundary of sub-Neptunes. At higher pressures, we found enhanced chemical mixing between magnesium and hydrogen. The experiments suggest that sub-Neptune exoplanets likely have a mineralogy different from that of rocky planets, and the chemical reaction between the atmosphere and interior can impact the size of sub-Neptunes and the compositions of their atmospheres.

Keywords: hydride, sub-Neptunes, exoplanets, hydrogen, magma

Abstract

Many sub-Neptune exoplanets have been believed to be composed of a thick hydrogen-dominated atmosphere and a high-temperature heavier-element-dominant core. From an assumption that there is no chemical reaction between hydrogen and silicates/metals at the atmosphere–interior boundary, the cores of sub-Neptunes have been modeled with molten silicates and metals (magma) in previous studies. In large sub-Neptunes, pressure at the atmosphere–magma boundary can reach tens of gigapascals where hydrogen is a dense liquid. A recent experiment showed that hydrogen can induce the reduction of Fe in (Mg,Fe)O to Fe metal at the pressure–temperature conditions relevant to the atmosphere–interior boundary. However, it is unclear whether Mg, one of the abundant heavy elements in the planetary interiors, remains oxidized or can be reduced by H. Our experiments in the laser-heated diamond-anvil cell found that heating of MgO + Fe to 3,500 to 4,900 K (close to or above their melting temperatures) in an H medium leads to the formation of MgFeH and HO at 8 to 13 GPa. At 26 to 29 GPa, the behavior of the system changes, and Mg–H in an H fluid and HO were detected with separate FeH. The observations indicate the dissociation of the Mg–O bond by H and subsequent production of hydride and water. Therefore, the atmosphere–magma interaction can lead to a fundamentally different mineralogy for sub-Neptune exoplanets compared with rocky planets. The change in the chemical reaction at the higher pressures can also affect the size demographics (i.e., “radius cliff”) and the atmosphere chemistry of sub-Neptune exoplanets.

Thick hydrogen-rich atmosphere is likely common in early rocky planets and among large low-density planets. In the early stage of planet formation, the accretion of planetesimals forms a core comprised of Mg-rich silicates/oxides and Fe-rich metal alloys (1). As the core becomes sufficiently large (0.5 to 0.75 , Earth mass unit), it can accrete the nebular gas (mostly hydrogen), and therefore, planets can develop hydrogen-rich primary atmospheres (2, 3). Earth and Venus in our solar system and the larger versions of them, such as super-Earth exoplanets (1.7 to 1.8 , Earth radius unit), have sufficient core masses to retain a hydrogen-rich atmosphere at least early in their geological history (4). In such a setting, chemical processes at the boundary between the atmosphere and magma ocean can impact the properties and dynamics of the planets.

The exoplanet surveys for the past 2 to 3 decades have accumulated mass-radius data for a large number of exoplanets. Such data have revealed previously unknown features in the demographics of the exoplanets, providing a new opportunity to advance our knowledge of their origin and evolution. One of the significant discoveries from the surveys so far is that planets with sizes between Earth and Neptune are common in our galaxy. Among these planets, sub-Neptunes at 1.8 to 3 have lower densities relative to rocky planets, suggesting a significant mass of atmosphere for sub-Neptunes. Sub-Neptunes likely have sufficient core masses to retain hydrogen-rich atmospheres (4). Therefore, models involving the rocky/metallic core with the hydrogen-rich atmosphere have been widely accepted for sub-Neptunes (5). In those planets, particularly larger ones, the atmosphere is likely thick enough that the pressure reaches tens of GPa at the boundary between the atmosphere and the interior. A thick atmosphere acts as a thermal blanket for the core to maintain a molten state (i.e., magma) for billions of years (6–8). Therefore, the physical and chemical interaction between dense hydrogen and molten silicates/oxides at high pressure–temperature (-) is the key to understand the interiors and atmospheres of sub-Neptunes.

Until recently, however, most models for these planets assumed that dense hydrogen and magma do not react with each other. Some recent models have considered the ingassing of hydrogen in magma in the form of H (9) and redox reactions involving Fe and Si (10) based on low pressure data. Recent models for sub-Neptunes have shown that the reactions between the hydrogen-rich atmosphere and magma can produce water and alter the composition of the atmosphere and interior (10, 11). For large low-density planets, the endogenic production in the interior can be an important source for water (11). It was proposed that such endogenic production may be important for Earth’s water as well (12). It is also possible that potential hydrogen–magma interaction may impact the exoplanet demographics. For example, the occurrence of sub-Neptunes shows a precipitous drop at , i.e., known as the radius cliff (13). It was proposed that high pressure expected under the thick atmosphere of a sub-Neptune may promote efficient physical ingassing of hydrogen to the magma, preventing further growth of the planet beyond the radius cliff (14).

Horn et al. (11) showed experimentally that hydrogen can reduce Fe in (Mg,Fe)O to Fe metal when the material is partially molten up to 4,000 K at 20 to 40 GPa. The reduced Fe metal subsequently reacts with H and forms Fe-H alloy. The reaction releases O atoms to an H medium, which then react with H to form HO. Therefore, the reaction allows for H ingassing as an alloy component in Fe metal (H) and hydroxyl ((OH) or HO) dissolved in magma. Shinozaki et al. (15) showed the dissolution of SiO in an H liquid at 2 to 3 GPa and 1,500 to 1,700 K, forming Si–H. The reaction also produces HO. Despite these important developments, the stability of MgO, one of the dominant components of planetary silicates and oxides, in an H-rich environment is still not well known for the range of - conditions expected for the atmosphere–interior boundary of sub-Neptunes (0.1 to 30 GPa and 2,000 K) (8, 16). Therefore, the persistence of MgO after heating documented in the experiments could be because of the kinetics of the solid–liquid reaction instead of the stability of MgO. In this study, we report experiments on MgO + Fe metal mixtures in a pure hydrogen medium at 3,500 to 4,900 K and 8 to 29 GPa, conditions close to the melting of MgO (17) (Fig. 1). We will discuss implications of the experimental results for sub-Neptune exoplanets.

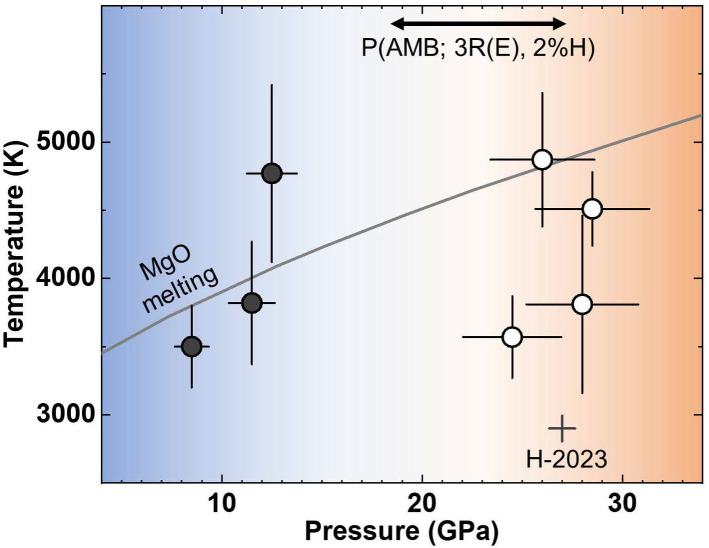

Fig. 1.

Pressure and temperature conditions (circles) of the experimental runs (SI Appendix, Table S1). Black and white circles represent the presence and absence of MgFeH, respectively. A color gradient in the background indicates a possible change in the chemical behavior of the system at 15 to 25 GPa. The arrow at the top shows the estimated range for the pressure at the atmosphere–magma boundary in sub-Neptunes with masses of 9.2 to 13.6 for a radius of and 2% hydrogen (SI Appendix, Text 5). : Earth radius. : Earth mass. The MgO melting curve is from ref. 17. H-2023: a data point for MgO + Fe in a pure H medium from ref. 11.

Methods

Thin foils of an MgO + Fe metal mixture were loaded in diamond-anvil cells (DACs). The foils were propped by MgO grains, as spacers, and pure H gas was loaded in the DACs (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Text 1). Experiments were conducted at beamline 13-IDD of GeoSoilEnviroCARS (GSECARS) at the Advanced Photon Source (APS). A double-sided laser-heating setup was combined with X-ray diffraction for measurements at high - (18). Because of the diamond embrittlement by H, we conducted pulsed laser heating (19–21) (SI Appendix, Text 2) to reach temperatures close to the melting of MgO. While the pulse heating method enables us to reach temperatures above 2,000 K for the H-rich sample, the heating duration is 0.1 to 0.2 s, which is not sufficient for measuring X-ray diffraction patterns with low noise. Furthermore, our heating targets melting. When a crystalline sample undergoes melting, its sharp and intense diffraction lines disappear, and broad diffraction features from melt appear. In a DAC, such broad diffraction features are difficult to separate from the strong background caused by Compton scattering from diamond anvils. Furthermore, melting in an H fluid can result in the removal of materials at the heating center therefore a lack of diffraction at the heating center (22); also found in our experiments as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S2A. Therefore, we focus on analyzing the diffraction patterns measured before and after laser heating at high pressures in this study.

Thermal radiation spectra were measured for both sides of the sample for temperature measurements. Pressures at high temperatures were calculated from the measured MgO volumes combined with its equation of state (23). Diffraction measurements (a beamsize of 3 2 m) were performed at the center of the heated area as well as its adjacent areas. Diffraction images were measured for 0.1 to 0.2 s at high temperatures and 30 s after heating at 300 K. Raman spectroscopy was conducted at GSECARS (24) and ASU using a 532-nm laser as an excitation source (SI Appendix, Text 3). The samples were recovered and prepared in a focused ion beam (FIB) instrument (Helios 5 UX, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) at ASU. The recovered samples were analyzed in scanning transmission electron microscopy (ARM-200F, JEOL co., at ASU) for chemical composition and imaging (SI Appendix, Text 4). A detailed description of our methods can be found in SI Appendix.

Results

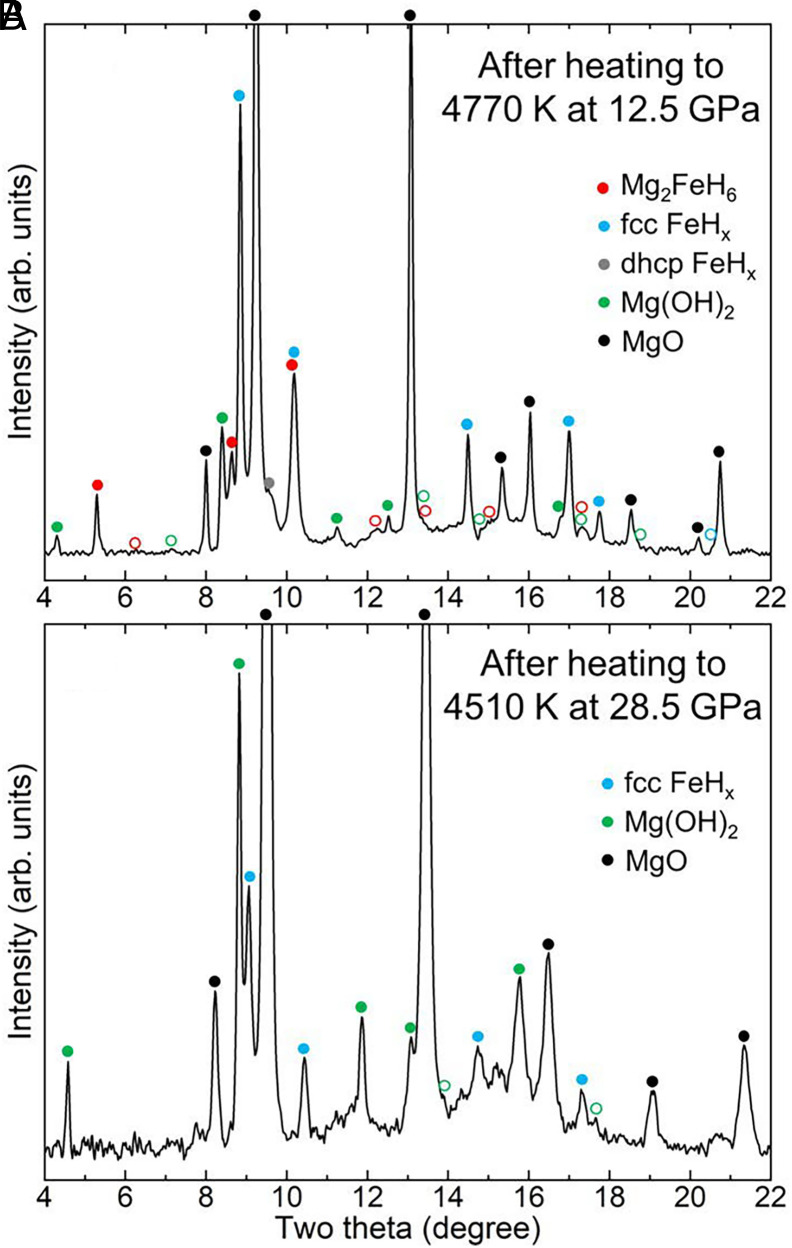

At 8 to 13 GPa after heating, XRD patterns showed the peaks from MgFeH, Mg(OH), face-centered cubic (fcc) FeH, and MgO (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4A). As shown in previous high-pressure studies, hydrogen alloys with liquid Fe metal at high - and form FeH, , which is also confirmed here (21, 25, 26) (in our experiments, ; SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Cubic MgFeH perovskite phase appeared after an MgO + Fe mixture was heated to temperatures above 3,500 K, which is close to or above the melting temperatures of MgO (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4A). Three intense peaks of MgFeH were clearly identified in diffraction images (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

X-ray diffraction patterns measured after the melting of MgO + Fe in H at (A) 4,770 K and 12.5 GPa and (B) 4,510 K and 28.5 GPa. The colored circles above the peaks indicate the peak positions of the observed phases in the legend. If peaks are either weak or not observed, we used open circles. The Le Bail analysis of pattern (A) is presented in SI Appendix, Fig. S6. The wavelength of the X-ray beam is 0.3344 Å. SEM analysis of the recovered sample for (A) is presented in SI Appendix, Fig. S2.

In the recovered samples, we often found a hole at the heating center (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). As shown in a previous study (22), convecting H fluid can remove some melt from the hottest spot, and in case the hole becomes sufficiently large, it can be observed in the LHDAC samples with hydrogen. Therefore, the observation of the holes in some samples can indicate melting. Horn et al. (11) studied the same system but only at pressures above 20 GPa. Shinozaki et al. (27) found MgO does not decompose in H at 1,500 K and 15 GPa. Therefore, the formation of MgFeH from MgO + Fe + H, which implies the dissociation of the Mg–O bond, likely requires heating to sufficiently high temperatures at pressures lower than 15 GPa (Fig. 1):

| [1] |

Reaching to the melting temperature of MgO (4,000 to 5,500 K) in an H medium at high pressure is extremely challenging (11). In this study, the experimental setup was optimized for achieving temperature as close to the melting of MgO in the presence of H, although this heating method makes it challenging to measure diffraction patterns at simultaneously high - (SI Appendix, Text 2). Previous studies have shown that the breakdown of the Fe–O bond (11, 28) and the Si–O bond (15) in the presence of hydrogen. However, to our knowledge, none of the previous studies have reported the breakdown of the Mg–O bond and the formation of Mg-Fe hydrides at the - conditions relevant to the atmosphere–magma boundary of sub-Neptunes.

Because of the Mg–O bond break, some O atoms can be released from MgO and react with either Fe or H in the system. The XRD patterns do not show any peaks of FeO and FeO (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4A). Under an H-rich environment, iron oxides (FeO and FeO) can be easily reduced to Fe metal by H at 2,000 to 3,000 K and 25 GPa (11), which explains no observation of iron oxides in our experiments. The diffraction peaks of HO are difficult to identify because of the peak overlap with fcc FeH expected at this pressure range. In addition, HO peaks have much weaker diffraction intensity. Related to HO, however, Mg(OH) peaks were observed (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4A). Mg(OH) can form through a reaction between MgO and HO during temperature quench at lower temperatures: MgO + HO (from Eq. 1) Mg(OH). Therefore, its appearance indicates the formation of HO as predicted in Eq. 1. In the laser-heated area, the O–H vibrational modes of HO-ice VII were detected in Raman spectroscopy at high pressure and 300 K after temperature quench (Fig. 3 A and B). Raman spectroscopy also detected the O–H vibration from Mg(OH).

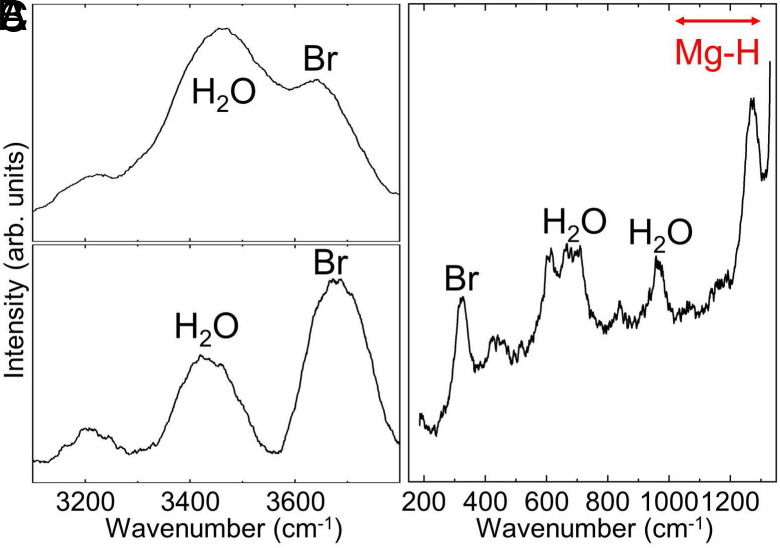

Fig. 3.

Raman spectra measured at (A) 7.0 GPa for the sample heated at 12.5 GPa and 4,770 K (#31-005), and (B) 11.5 GPa and 3,820 K (#31-003), and (C) 22.0 GPa for the sample heated at 26.0 GPa and 4,870 K (#26-009) (SI Appendix, Table S1). SEM data for the sample in (C) is presented in SI Appendix, Fig. S12. HO: HO-VII and Br: Mg(OH).

At 26 to 29 GPa, XRD patterns showed the formation of fcc FeH and Mg(OH), whereas MgFeH peaks were not found (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Figs. S4 B and C). As discussed above, the appearance of Mg(OH) requires HO formation and therefore the release of O from MgO through the breakage of some Mg–O bond (Eq. 1). Similar to the case of Fe in (Mg,Fe)O (11), it can be hypothesized that O is released by Mg reduction to Mg metal. It is also possible that Mg–O bond breaks down, but Mg remains as Mg. Diffraction lines of Mg metal or its alloy forms were not observed at high pressures after heating, thus Mg was unlikely reduced to Mg metal. If Mg dissolves in H liquid during melting, it would not create any diffraction peaks. Related to the system we study here, a recent study showed that MgO can dissolve into HO fluid at 30 GPa and above 1,500 K (29). Similarly, Mg and H may form an Mg–H bond. In our experiments, when the sample was decompressed to 1 GPa, several diffraction spots appeared in XRD images. Those spots were detected at the same two theta angle at different azimuthal angles (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). The two-theta angle does not match with any diffraction peaks expected for Mg(OH), MgO, Fe metal, and fcc FeH. The observed peak is possibly from the crystallization of a component dissolved in H liquid at high pressures during decompression. However, no more clear diffraction features were observed, and therefore, we could not identify the phase with XRD alone.

After heating at 26 to 29 GPa, an intense O–H vibration from Mg(OH) and HO was observed at 2,800 to 3,700 cm as well as the lattice modes of Mg(OH) (30) and HO (31) at 200 to 1,300 cm (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Figs. S8 and S9). Upon decompression, the peak shifts to lower wavenumbers but remains in the range (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). The Mg–H stretching vibration exists between 900 and 1,300 cm at 1 bar (32) (SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10). At 1 GPa, some additional Raman peaks appeared. The mode frequencies of these peaks agree well with those expected for the lattice vibrational modes of -MgH (33) (SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10B), although some level of intensity contribution from weak HO Raman modes cannot be ruled out (31). From these observations, we interpret that some Mg may dissolve into H fluid (i.e., Mg–H) at pressures above 25 GPa and 3,500 K:

| [2] |

The dissolved Mg–H precipitates with decompression because of its lowering solubility in H at lower pressures.

In our experiments, a complete conversion of MgO to MgH was not observed. The total heating duration was 0.1 to 0.2 s, and it could not be extended any further because of the possible mechanical failure of diamond anvils by H (SI Appendix, Text 2). The heating duration may not be sufficient for the completion of the reaction (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4). It is also possible that HO, produced from the reaction, makes the condition more oxidizing than the initial redox condition from a pure H medium. Therefore, the reaction (Eq. 2) may not proceed any further.

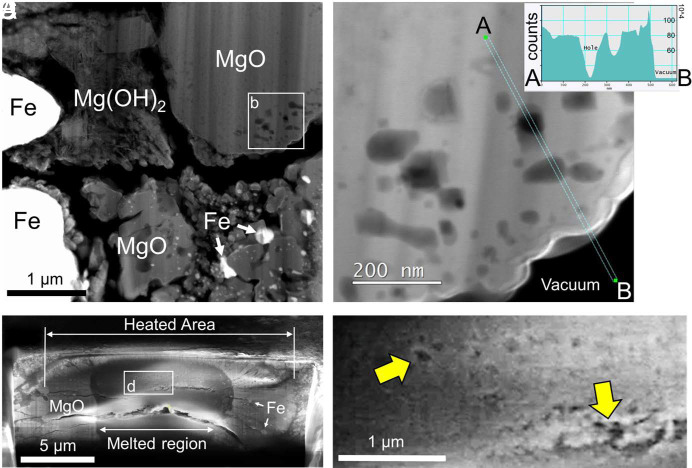

The recovered samples were analyzed in STEM (scanning transmission electron microscopy) and SEM (scanning electron microscopy). The samples are fractured and mechanically weak because of the O release, melting in a fluid H medium, and hydrogen transition from solid/liquid to gas during decompression (Fig. 4 A and C and SI Appendix, Figs. S2, S11, and S12). Therefore, it was difficult to recover all the samples studied at the synchrotron. For the sample recovered from 11.5 GPa, bubble-shaped structures were observed near the edge of MgO grains (Fig. 4B). The size of the structure ranges between 50 and 100 nm. Inside the bubble-shaped area, intensity was found to be as low as that found at the vacuum (Fig. 4B). The intensity in an STEM annular dark-field (ADF) image is proportional to , where is the atomic numbers and is the empirical parameters (35). Therefore, the bubble-like structures are either empty or filled with low elements, most likely H in this experiment.

Fig. 4.

STEM (A and B) and SEM (C and D) images of the heated areas in the samples recovered from run #31-003 (11.5 GPa and 3,820 K) and #26-009 (26 GPa and 4,870 K), respectively (SI Appendix, Table S1). (A) An FIB section shows some of the phases found in XRD. The small bright grains are bcc Fe metal (labeled as Fe) converted from fcc FeH during decompression (34). The diffraction pattern for the converted Fe metal can be found in SI Appendix, Fig. S7. The Fe grains in the left side are not heated. (B) Bubble-shaped structures are found along the edge of MgO grans (a white box in A). An intensity line profile between point A and point B is shown in the inset. (C) A cross-section of the laser-heated area in the sample foil was made in FIB to reveal the structures. The center of the heated area contains more MgO and the surrounding area contains more Fe metal. Some Fe metal may migrate during melting along the radial thermal gradients. (D) A magnified image (a white box in C) reveals the bubble-shaped structures (highlighted by yellow arrows) within the heated area, similar to the ones observed in (B) but in larger sizes (note the scale difference).

In a sample recovered from 26 GPa, similar bubble-shaped structures are observed with larger sizes, ranging between 100 and 300 nm (Fig. 4 C and D). It is possible that such bubble-shaped structures were formed from the mechanical capturing of H or HO (formed by the reactions) fluid in the melt during temperature quench.

Alternatively, such structures can form from the separation of two components that were once miscible at high temperature. In this case, because of the much lower mutual solubility at lower temperatures, the two components can separate into different phases during temperature quenching, resulting in the formation of the bubble-shaped structure. In the case of the albite–HO system, they become miscible with each other at 0.73 GPa and 1,673 K (36). During temperature quench, because of the low solubility of HO in albite at lower temperatures, the exsolved HO can form bubble-shaped structures in the albite crystal. Therefore, if the same process occurs for the MgO–H system studied here, H once mixed with MgO melt may form the bubble-shaped structures during temperature quench.

At 25 GPa, the size of the bubble-shaped structure is larger and Mg–H mode is observed in H, indicating that the mutual solubility during heating is much greater at the higher pressures (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Fig. S12B).

Horn et al. (11) conducted experiments on (Mg,Fe)O in H at a similar - range. They reported the reduction of Fe and the formation of Mg(OH), but did not report the Mg–H mixing. However, they did not conduct TEM, SEM, and Raman spectroscopy measurements which are critical for detecting the Mg–H mixing in our study.

Implications

In recent studies, possible chemical reactions between hydrogen and silicates/metals have been drawn interest for their potential impacts on planetary processes (11, 12, 21). A high-pressure study (11) showed that H can induce the reduction of Fe in (Mg,Fe)O to Fe metal. Because of the electron transfer from H to Fe (the first two reactions in Eq. 3 below), O atoms released from (Mg,Fe)O (the first reaction in Eq. 3) react with H, resulting in the formation of HO (the third reaction in Eq. 3, which can be obtained by combining first two reactions).

| [3] |

The endogenically produced water can partition into both magma and atmosphere (“atm” in Eq. 3).

We found that MgO reacts with H at higher temperatures, breaking Mg–O bonds and forming Mg–H bonds (hydride, H), leading to the formation of MgFeH at pressures below 13 GPa and the possible dissolution of Mg in H fluid (i.e., Mg–H) at pressures above 24 GPa. Our Raman measurements showed the formation of HO (and therefore proton, H). From these observations, the following chemical reactions with electron transfer can be inferred (the fourth reaction can be obtained by combining first three reactions; note that we are talking about a general case here for the Mg-related components which can be applied to both Eqs. 1 and 2):

| [4] |

The key differences from the Fe case (11) include: 1) Mg remains oxidized (the first reaction in Eq. 4), 2) Mg forms bonding directly with H (hydride) (the second reaction in Eq. 4), and 3) electron transfer occurs between hydrogen atoms to form protons which react with O to form water (the third reaction in Eq. 4). As Mg is one of the dominant heavy elements in the planetary interiors, the chemical process we identified here can add a significant amount of HO to the total endogenic HO in addition to the HO from the Fe reduction found in ref. 11. An important difference between Fe and Mg in the reaction with H in a planetary setting is that after the reduction Fe metal would sink toward the center (because of its high density), and therefore be separated from the atmosphere and magma. However, Mg, by forming hydride bonding, would likely remain in the atmosphere and/or magma, possibly contributing to radial compositional gradients at the shallower depths in the planets together with endogenic HO.

At the - conditions (8 to 13 GPa and 3,500 to 4,800 K) relevant for the interface between the atmosphere and the magma ocean in H-rich sub-Neptunes, we observed the formation of MgFeH from the reaction between MgO + Fe and H. For example, for GJ1214b ( and ), 8 GPa and 3,000 K were estimated for the atmosphere–magma boundary (37). MgFeH, the material formed under the planetary conditions in our experiments below 13 GPa has been extensively studied in condensed matter physics and materials science because of its importance for H storage applications (38). Our experiments show that MgFeH can exist in a H-rich planet, i.e., the atmosphere–magma boundary (AMB) of sub-Neptune exoplanets, potentially important for the H storage in a natural setting as well (Fig. 5).

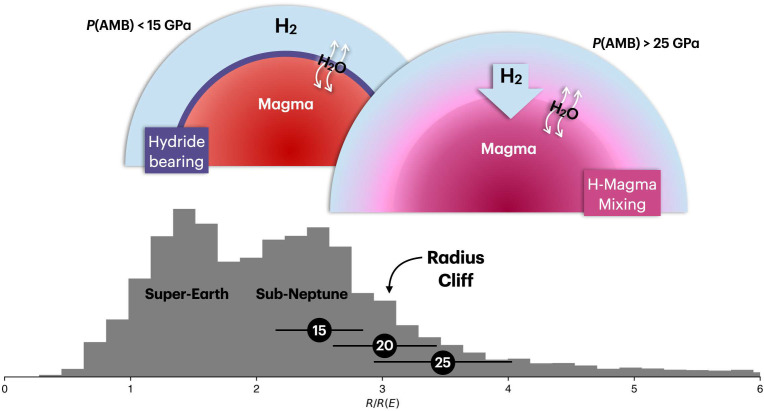

Fig. 5.

An exoplanet size demographics histogram up to (: radius, : Earth’s radius; Bottom) shown together with the implications of our experiments on the radius cliff (Top). Schematic diagrams for the structures of sub-Neptunes with GPa and GPa are shown (AMB: atmosphere–magma boundary). In the histogram, three horizontal bars show the estimated radii of sub-Neptunes (2 wt% H atmosphere with an Earth-like interior composition) for different pressures (in GPa) at the atmosphere–magma boundary (see SI Appendix, Text 5 for method).

Spectroscopy studies have shown that the valence states of Mg and [FeH] in MgFeH are and , respectively (39, 40). Therefore, reduction to metal does not occur for Mg under H, as we found no evidence for Mg metal or alloy in the experiment. However, our experiments show that by breaking the Mg–O bond MgO + H reaction can still produce HO (Eqs. 1 and 4). The valence state of Fe in the [FeH] complex has been debated: Fe (39) or Fe (40). A computational study (41) showed that the bonding between Fe and H is partially covalent. Because of Mg in MgFeH and the higher electronegativity of H than Fe, [FeH] should have some degree of ionic bonding, therefore a negative charge for H. This means hydride bonding should exist regardless of whether the valence state of Fe is 2+ or 0. Therefore, our experiments reveal an intriguing possibility of co-ingassing of H (in MgFeH hydride) and H (in HO) in a planetary setting.

Our measurements combined with the existing data (38, 42) found that MgFeH has a substantially lower density than MgSiO and MgO, which are representative silicate/oxide for the rocky part of planets (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). MgFeH has a perovskite-type structure, similar to the crystal structure of MgSiO above 24 GPa (orthorhombic perovskite structure; bridgmanite). However, MgFeH has a vacancy-ordered double perovskite structure (43). Bridgmanite, with a normal perovskite structure, has no vacant site between the SiO octahedra which are connected with each other by the corner sharing. However, in the crystal structure of MgFeH (space group: , #225), the FeH octahedra, positioned at the lattice points of face-centered cubic, are isolated with each other because of the ordered vacancies (40). Therefore, the crystal structure of MgFeH and its high H content can explain its low density. Given as much as 15 to 30% lower density than MgSiO between 1 bar and 20 GPa (we compare to MgSiO enstatite, a phase stable at the pressure range), MgFeH likely remains less dense than silicate even at the high temperatures of planetary interiors. Therefore, MgFeH can be buoyant when it crystallizes in the magma ocean or in the solidified silicate rocky layer. Such buoyant MgFeH at the interface between the atmosphere and the interior can be an important agent for maintaining very reducing conditions for the underlying interior. It is also feasible that other hydrides may form at the interface (15). If dense hydrides can be formed, and ingassing of hydride (H) could be extended to much greater depths combined with the convective flow of the interior.

In ref. 11, from the higher melting temperature of MgO, it was postulated that MgO may crystallize first from the magma ocean beneath a thick H-rich atmosphere and form a crust. They further hypothesized that the MgO-rich crust could regulate the interaction between H-rich atmosphere and the magma ocean. According to our experiments, Mg-Fe hydrides may form at the interface and therefore such an MgO-rich crust unlikely forms.

MgFeH does not form at pressures above 25 GPa. Instead, the Raman data, together with the electron microscopy data, indicate that Mg may dissolve into an H fluid at this pressure range. In other words, MgO (possibly in a liquid form) may become (at least partially) miscible with an H liquid.

According to the Kepler data, planet occurrence drops sharply at dividing sub-Neptune exoplanets and Neptune-size exoplanets (i.e., radius cliff; Fig. 5) (13, 14, 44). Kite et al. (14) proposed that a sudden increase in the H solubility in magma by pressure effects may ingas much more H at the radius cliff, rather than leave much hydrogen for building the atmosphere. Because of the significant ingassing of H and much smaller molar volume of H expected for the ingassed states compared with pure H, the atmosphere does not increase as much and therefore the radius of a planet does not increase as much near , leading to a low population of planets with radius greater than .

For a sub-Neptune with 2 wt% H atmosphere and an Earth-like interior composition, the pressure at the atmosphere–magma boundary () can be estimated for a planet radius using the equations in refs. 8 and 45 (SI Appendix, Text 5 for detail). From the calculation, we found that sub-Neptunes with radii of , , and can have pressures of 15, 20, and 25 GPa at the AMB, respectively. We observed the formation of MgFeH below 15 GPa. Therefore, for a smaller sub-Neptune , MgFeH may crystallize at the AMB and remain there, because of its lower density than silicate melt (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Its high concentration at the AMB could regulate the H ingassing to the magma ocean beneath. At pressures higher than 25 GPa, our experiments found that MgFeH is no longer stable. Instead, the detection of the Mg–H vibration and the bubble-shaped structures found in the recovered samples point toward much-enhanced chemical mixing between Mg and H at the higher pressure range (Fig. 5B). Therefore, if a sub-Neptune type planet can grow large enough to , the pressure at the AMB can become sufficiently high for the effective chemical mixing between Mg and H, and therefore efficient H ingassing. If such a process indeed occurs, similar to the proposed process in ref. 14, a large sub-Neptune type planet may not grow efficiently beyond a certain size, i.e., , as more H is added to the interior where its molar volume is much smaller than that for H in the atmosphere. Therefore, it is feasible that the sharp decrease in the planets’ occurrence at (i.e., radius cliff) is related to the chemical process we identified in this study. An important difference from Kite et al. (14) is that they assumed the physical mixing between H and magma for the radius cliff. It is, however, important to note that they extrapolated experimental results measured below 3 GPa (46), accuracy of which is debatable (10). Our experiments conducted directly at the pressure conditions relevant to the larger sub-Neptunes’ interiors show that the chemical mixing through the Mg–H bond formation could be an important process to consider for the possible enhancement of the H ingassing at the radius cliff.

If the reaction we identified in this study also occurs at lower pressures, it would be important to consider such chemical interactions in early rocky planets with H-rich primary atmosphere (12). It is of particular interest how the potential formation of hydride minerals on the surface can impact the habitability of the early rocky planets.

The on-going space telescope (e.g., JWST) and large ground-based telescope missions aim to measure the atmosphere chemistry of exoplanets (including sub-Neptunes) which will be an important step toward answering a fundamental question: Are we alone in the universe (47)? Because hydrogen-rich atmosphere should be reactive particularly with refractory materials (silicates and oxides) underneath, the atmosphere–interior interaction is key to understand such astrophysical measurements. However, models so far considered mostly physical mixing of H (or H) in silicate magma (9, 46). Latest experiments begin to reveal other important interactions between hydrogen-rich atmosphere and magma: HO formation through the Fe reduction (11), and H alloying with Fe metal (21). Here, we demonstrated that anionic hydrogen, H (or hydride), can exist in the setting expected for sub-Neptune exoplanets. Furthermore, our experiments reveal that hydride can form together with water, both of which can partition to the atmosphere and the interior of sub-Neptunes (Fig. 5). Therefore, it is important to consider these reactions in the interpretation of exoplanet atmosphere spectra.

In fact, a recent astrophysical study detected CrH in the H-rich atmosphere of hot Jupiter WASP-31b together with HO (48), demonstrating the importance of understanding the type of chemical interaction we report here even for the less abundant heavy elements.

Hydrides have been important materials to study in condensed matter physics for hydrogen storage (49) and high-temperature superconductivity (50). Our study demonstrates that such studies of hydrides can also impact our understanding of the evolution and dynamics of sub-Neptune exoplanets, which are common in our galaxy (5).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism and helpful comments, which improved our paper. This work was supported by NSF grants AST2108129 (T.K. and S.-H.S.) and AST2005567 (X.W. and S.-H.S). This work was performed at GeoSoilEnviroCARS (GSECARS) (The University of Chicago, Sector 13), Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory (ANL). GSECARS is supported by the NSF–Earth Sciences (EAR-1634415). This research used resources of the APS, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by ANL under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the GSECARS Raman Lab System was supported by the NSF Major Research Instrumentation (MRI) Proposal (EAR-1531583). We also acknowledge the use of facilities at the Eyring Materials Center at Arizona State University (ASU) supported in part by NNCI-ECCS-1542160.

Author contributions

T.K. and S.-H.S. designed research; T.K., X.W., S.C., V.B.P., Y.-J.R., S.Y., and S.-H.S. performed research; T.K., X.W., S.C., V.B.P., Y.-J.R., S.Y., and S.-H.S. participated in the revision stage; T.K. and S.-H.S. analyzed data; and T.K. and S.-H.S. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Taehyun Kim, Email: tkim95@asu.edu.

Sang-Heon Shim, Email: sshim5@asu.edu.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the main article and supporting information.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Lambrechts M., Johansen A., Rapid growth of gas-giant cores by pebble accretion. A&A 544, A32 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lammer H., et al. , Origin and evolution of the atmospheres of early Venus, Earth and Mars. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 26, 2 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venturini J., Ronco M. P., Guilera O. M., Setting the Stage: Planet Formation and Volatile Delivery. Space Sci. Rev. 216, 86 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen J. E., Shaikhislamov I. F., Lammer H., Fossati L., Khodachenko M. L., Hydrogen dominated atmospheres on terrestrial mass planets: Evidence origin and evolution. Space Sci. Rev. 216, 129 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bean J. L., Raymond S. N., Owen J. E., The nature and origins of sub-Neptune size planets. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 126, e2020JE006639 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vazan A., Ormel C. W., Noack L., Dominik C., Contribution of the core to the thermal evolution of sub-Neptunes. ApJ 869, 163 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kite E. S., Fegley B. Jr., Schaefer L., Ford E. B., Atmosphere origins for exoplanet sub-Neptunes. ApJ 891, 111 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng L., et al. , New perspectives on the exoplanet radius gap from a mathematica tool and visualized water equation of state. ApJ 923, 247 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson P., Sharp Z. D., Hydrogen and helium ingassing during terrestrial planet accretion. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 498, 418–426 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlichting H. E., Young E. D., Chemical equilibrium between cores, mantles, and atmospheres of super-earths and sub-Neptunes and implications for their compositions, interiors, and evolution. Planet. Sci. J. 3, 127 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horn H. W., Prakapenka V., Chariton S., Speziale S., Shim S. H., Reaction between hydrogen and ferrous/ferric oxides at high pressures and high temperatures-implications for sub-Neptunes and super-earths. Planet. Sci. J. 4, 30 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young E. D., Shahar A., Schlichting H. E., Earth shaped by primordial H atmospheres. Nature 616, 306–311 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulton B. J., Petigura E. A., The California- Kepler survey. VII. Precise planet radii leveraging Gaia DR2 reveal the stellar mass dependence of the planet radius gap. AJ 156, 264 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kite E. S., Jr B. F., Schaefer L., Ford E. B., Superabundance of Exoplanet Sub-Neptunes Explained by Fugacity Crisis. ApJ 887, L33 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shinozaki A., et al. , Formation of SiH and HO by the dissolution of quartz in H fluid under high pressure and temperature. Am. Miner. 99, 1265–1269 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stökl A., Dorfi E. A., Johnstone C. P., Lammer H., Dynamical accretion of primordial atmospheres around planets with masses between 0.1 and 5 in the habitable zone. Astrophys. J. 825, 86 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura T., Ohfuji H., Nishi M., Irifune T., Melting temperatures of MgO under high pressure by micro-texture analysis. Nat. Commun. 8, 15735 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prakapenka V. B., et al. , Advanced flat top laser heating system for high pressure research at GSECARS: Application to the melting behavior of germanium. High Pressure Res. 28, 225–235 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goncharov A. F., et al. , X-ray diffraction in the pulsed laser heated diamond anvil cell. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 81, 113902 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu S., Chariton S., Prakapenka V. B., Shim S. H., Core origin of seismic velocity anomalies at Earth’s core- mantle boundary. Nature 615, 646–651 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piet H., et al. , Superstoichiometric alloying of H and close-packed Fe-Ni metal under high pressures: Implications for hydrogen storage in planetary core. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101155 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu S., Chariton S., Prakapenka V. B., Chizmeshya A., Shim S. H., Stable hexagonal ternary alloy phase in Fe-Si-H at 28.6-42.2 GPa and 3000 K. Phys. Rev. B 105, 104111 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorogokupets P. I., Dewaele A., Equations of state of MgO, Au, Pt, NaCl-B1, and NaCl-B2: Internally consistent high-temperature pressure scales. High Pressure Res. 27, 431–446 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holtgrewe N., Greenberg E., Prescher C., Prakapenka V. B., Goncharov A. F., Advanced integrated optical spectroscopy system for diamond anvil cell studies at GSECARS. High Pressure Res. 39, 457–470 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okuchi T., Hydrogen partitioning into molten iron at high pressure: Implications for earth’s core. Science 278, 1781–1784 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakamaki K., et al. , Melting phase relation of FeH up to 20 GPa: Implication for the temperature of the Earth’s core. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 174, 192–201 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinozaki A., et al. , Influence of H fluid on the stability and dissolution of MgSiO forsterite under high pressure and high temperature. Am. Miner. 98, 1604–1609 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Efimchenko V. S., et al. , Destruction of fayalite and formation of iron and iron hydride at high hydrogen pressures. Phys. Chem. Minerals 46, 743–749 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim T., et al. , Atomic-scale mixing between MgO and HO in the deep interiors of water-rich planets. Nat. Astron. 5, 815–821 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 30.T. S. Duffy, R. J. Hemley, H. K. Mao, “Structure and bonding in hydrous minerals at high pressure: Raman spectroscopy of alkaline earth hydroxides” in AIP Conference Proceedings (AIP, Pasadena, California, USA, 1995), vol. 341, pp. 211–220.

- 31.Zha C. S., Tse J. S., Bassett W. A., New Raman measurements for HO ice VII in the range of 300 cm to 4000 cm at pressures up to 120 GPa. J. Chem. Phys. 145, 124315 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shantilal Gangrade A., Aditya Varma A., Kishor Gor N., Shriniwasan S., Tatiparti S. S. V., The dehydrogenation mechanism during the incubation period in nanocrystalline MgH. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 6677–6687 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuzovnikov M., et al. , Raman scattering study of -MgH and -MgH. Solid State Commun. 154, 77–80 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badding J., Hemley R., Mao H., High-pressure chemistry of hydrogen in metals: In situ study of iron hydride. Science 253, 421–424 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang S. Z., et al. , Direct cation exchange in monolayer MoS via recombination-enhanced migration. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 106101 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paillat O., Elphick S. C., Brown W. L., The solubility of water in NaAlSiO melts: A re-examination of Ab-HO phase relationships and critical behaviour at high pressures. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 112, 490–500 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nettelmann N., Fortney J. J., Kramm U., Redmer R., Thermal evolution and structure models of the transiting super-Earth GJ 1214b. ApJ 733, 2 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 38.George L., Drozd V., Durygin A., Chen J., Saxena S. K., Bulk modulus and thermal expansion coefficient of mechano-chemically synthesized MgFeH from high temperature and high pressure studies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 34, 3410–3416 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Didisheim J. J., et al. , Dimagnesium iron(II) hydride, MgFeH, containing octahedral FeH- anions. Inorg. Chem. 23, 1953–1957 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Retuerto M., et al. , Neutron powder diffraction, x-ray absorption and Mössbauer spectroscopy on MgFeH. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 40, 9306–9313 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zareii S. M., Sarhaddi R., Structural, electronic properties and heat of formation of MgFeH complex hydride: An ab initio study. Phys. Scr. 86, 015701 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson J. M., Sinogeikin S. V., Bass J. D., Elasticity of MgSiO orthoenstatite. Am. Miner. 84, 677–680 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahim W., et al. , Geometric analysis and formability of the cubic ABX vacancy-ordered double perovskite structure. Chem. Mater. 32, 9573–9583 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsu D. C., Ford E. B., Ragozzine D., Ashby K., Occurrence rates of planets orbiting FGK stars: Combining Kepler DR25, Gaia DR2, and Bayesian inference. AJ 158, 109 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otegi J., Bouchy F., Helled R., Revisited mass-radius relations for exoplanets below 120 m(e). Astron. Astrophys. 634, A43 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirschmann M., Withers A., Ardia P., Foley N., Solubility of molecular hydrogen in silicate melts and consequences for volatile evolution of terrestrial planets. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 345–348, 38–48 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics (Astro2020), Space Studies Board, Board on Physics and Astronomy, Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2021). Pathways to Discovery in Astronomy and Astrophysics for the 2020s (National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2020), p. 26141.

- 48.Braam M., van der Tak F. F., Chubb K. L., Min M., Evidence for chromium hydride in the atmosphere of hot Jupiter WASP-31b. Astron. Astrophys. 646, A17 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakintuna B., Lamaridarkrim F., Hirscher M., Metal hydride materials for solid hydrogen storage: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 32, 1121–1140 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duan D., et al. , Structure and superconductivity of hydrides at high pressures. Natl. Sci. Rev. 4, 121–135 (2017). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the main article and supporting information.