Abstract

Influenza infection and vaccination impart strain-specific immunity that fails to protect against both seasonal antigenic variants and the next pandemic. However, antibodies directed to conserved sites can confer broad protection. We identify and characterize a class of human antibodies that engage a previously undescribed, conserved, epitope on the influenza hemagglutinin protein (HA). Prototype antibody S8V1-157 binds at the normally occluded interface between the HA head and stem. Antibodies to this HA head-stem interface epitope are non-neutralizing in vitro but protect against lethal infection in mice. Their breadth of binding extends across most influenza A serotypes and seasonal human variants. Antibodies to the head-stem interface epitope are present at low frequency in the memory B cell populations of multiple donors. The immunogenicity of the epitope warrants its consideration for inclusion in improved or “universal” influenza vaccines.

INTRODUCTION:

Influenza pandemics arise from antigenically novel animal influenza A viruses transmitted to humans from zoonotic hosts. Historically, pandemic viruses have generally become endemic and have continued to circulate as seasonal viruses. Sustained viral circulation comes from on-going antigenic evolution that leads to escape from population-level immunity elicited by previous exposures 1. Immunity elicited by infection, vaccination, or both is insufficient to confer enduring immunity against seasonal variants or future pandemic viruses. Although antibodies provide the strongest protection against infection, they also drive the antigenic evolution of the viral surface proteins 1. Broadly protective monoclonal antibodies that engage conserved sites have been isolated from human donors 2. Passive transfer of these antibodies to animal models imparts broadly protective immunity. Selective elicitation of similar antibodies by a next generation influenza vaccine is predicted to confer protection less susceptible to escape than protection from current vaccines 3-5.

The influenza hemagglutinin (HA) protein is the major target of protective antibodies 6. HA facilitates cell entry by attaching to cells via an interaction with its receptor, sialic acid, and by acting as a virus-cell membrane fusogen. HA is synthesized as a polyprotein, HA0, which forms homotrimers that are incapable of undergoing the full series of conformational rearrangements required for membrane fusion. A fusion-competent trimer is produced by cleavage of HA0 into HA1 and HA2 domains by cellular proteases often resident on the target cell 7-9. HA1 includes the globular HA head domain that contains the receptor binding site (RBS), while HA2 contains the helical stem regions that undergo a cascade of rearrangements that ultimately fuse viral and cellular membranes. The requirement for HA to transit through multiple conformations during fusion likely accounts for the intrinsic propensity of HA0 or HA1-HA2 to transiently explore states that deviate from the stable prefusion form defined by static structures determined by X-ray crystallography 10-13.

Large genetic and antigenic differences separate influenza A HA proteins. They are classified into two groups comprising 16 sialic acid binding serotypes: group 1 (H1, H2, H5, H6, H8, H9, H11, H12, H13, H16) and group 2 (H3, H4, H7, H10, H14, H15). Using a similar convention for a second glycoprotein, neuraminidase (NA), influenza viruses are named by their HA and NA content (e.g., H2N2, H10N8). Currently, divergent H1N1 and H3N2 viruses circulate as seasonal human influenza viruses. Humans can produce antibodies that engage surfaces conserved between serotypes and thereby provide cross-serotype protection. These epitopic regions include the HA RBS, stem, anchor, head interface, the so-called "long alpha helix", and the HA2 beta-hairpin (PDB 8UDG reported in Finney et al, PNAS in press) 2,14-17

Here, we report a class of human antibodies directed to a previously unreported, widely conserved, site at the base, or neck, of the HA head domain. In the stable prefusion structure of the HA trimer, the epitope for prototype antibody S8V1-157 is at the interface of the head and stem, occluded in the "resting state" prefusion conformation. Biochemical, cellular, and in vivo passive transfer experiments indicate that this HA head-stem interface epitope is sufficiently exposed to allow antibody binding and to confer strong protection against lethal influenza virus infection in murine challenge models. Many humans harbor antibodies directed to this epitope; some of these antibodies bind HAs from divergent influenza serotypes, groups, and >50 years of human seasonal virus antigenic variation. Immunogens that elicit such antibodies might be included in influenza vaccines intended to confer broader protection.

RESULTS:

A class of antibodies engages an epitope at head-stem epitope of the HA head domain.

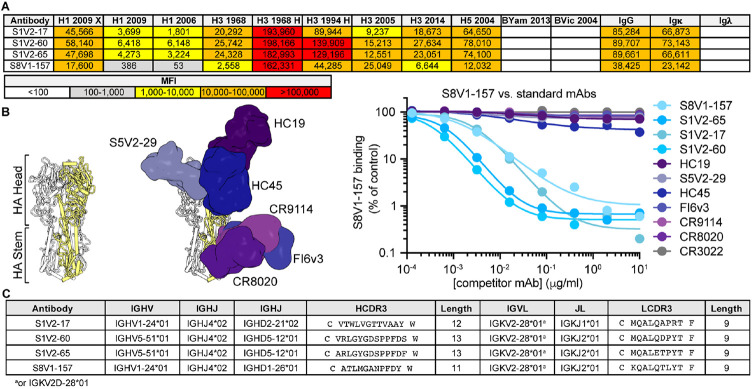

By culturing individual human memory B (Bmem) cells and then screening the culture supernatants containing secreted IgGs, we identified (as reported previously 18) 449 HA-reactive antibodies from four donors (S1, S5, S8 and S9). These antibodies represent the Bmem cells circulating in the blood at the time the donors were immunized with the TIV2015-2016 seasonal influenza vaccine (visit 1; V1), or 7 days later (visit 2; V2). From donors S1 and S8, we found four IgGs (S1V2-17, S1V2-60, S1V2-65 and S8V1-157 that had a novel pattern of HA reactivity (Figure 1A). All bound seasonal H1s and H3s and an H5 HA; they also bound recombinant HA constructs comprising only the HA head domain, indicating the IgGs did not target stem epitopes (Figure 1A). These four antibodies competed with each other for HA-binding, implying overlapping epitopes, but failed to compete with antibodies directed to conserved, broadly protective epitopes in the HA head and stem (Figure 1B).

Figure 1: Identification of a novel, broadly binding, HA head-directed antibody class.

A. Luminex screening of Bmem-cell Nojima culture supernatants identified four antibodies that broadly react with influenza A HA FLsEs and head domains. B. In a Luminex competitive binding assay, the four antibodies from (A) that share a pattern of reactivity did not compete with antibodies that engage known HA epitopes, but compete with each other for HA binding. Structures of Fab-HA complexes were aligned on an HA trimer from A/American black duck/New Brunswick/00464/2010(H4N6) (PDB: 5XL2)19. Fab structures include HC1920 (PDB 2VIR), S5V2-2918 (PDB 6E4X), HC4542 (PDB 1QFU), CR911443 (PDB 4FQY), CR802044 (PDB 3SDY) and FI6v330 (PDB 3ZTJ). SARS-CoV antibody CR302221 was used as an HA non-binding control. C. The cross-competing HA antibodies share genetic signatures.

All four antibodies had light chains encoded by IGKV2-28*01 or IGKV2D-28*01 (Figure 1C), which have identical germline coding sequences. The heavy chains are encoded by either IGHV1-24*01 or IGHV5-51*01 and have short (11-13 amino acid) third complementarity-determining regions (HCDR3s). S1V2-60 and S1V2-65 are clonally related, while S1V2-17 and S8V1-157 share a common IGHV1-24*01-IGKV2-28*01 pairing, despite their derivation from different donors.

We determined the structure of S8V1-157 complexed with a monomeric HA head construct. Crystals were only obtained using an A/American black duck/New Brunswick/00464/2010(H4N6) (H4-NB-2010) HA (Figure 2A and Table S1). S8V1-157 engages an epitope at the base of the head, just where it faces the stem 19. Hence this HA1 epitope is occluded by the association of HA1 with HA2 (Figure 2A). S8V1-157 contacts residues mediating the intra-protomer interaction, which are conserved across divergent HAs (Figure 2B). Evolutionary constraints imposed by the requirement of stable association, at neutral pH, of HA1 and HA2 likely account for the conservation of the head-stem interface epitope and its respective breadth of binding of these antibodies. Antibody or B cell receptor engagement of the HA this epitope, in the context of a prefusion HA molecule, would require displacement of the HA head from the HA2 helical stem.

Figure 2: Human antibodies engage a recessed surface at the head-stem interface of the influenza HA molecule.

A. Structure of antibody S8V1-157 complexed with the HA head domain of A/American black duck/New Brunswick/00464/2010(H4N6) colored in gray. The heavy chain is colored darker blue and the light chain is lighter blue. Engagement of this site is incompatible with the defined prefusion H4 HA trimer19, colored in white (PDB: 5XL2) or with individual HA monomers. B. A surface projection showing the degree of amino acid conservation among HAs engaged by this antibody class (see Figure 3). The head-stem epitope is circumscribed in blue in the rightmost panel. Conservation scores were produced using ConSurf 45,46. C. Key S8V1-157 contacts. The orientation relative to panel A is indicated.

The compact HCDR3 of S8V1-157 packs against the heavy chain CDR and framework regions (FR), HCDR1-FR1 and FR2-HCDR2, to produce a cleft between the heavy and light chains that accommodates the head-stem interface epitope (Figure 2C). Residues N33, Y35 and Y37 within the elongated LCDR1 make extensive contacts with a conserved HA surface. The δ-amide of N33 donates and receives hydrogen bonds from the main chain of HA residue HA-C305. Its main chain amide also donates a hydrogen bond to the carboxyl group of HA-D304. Y35 donates a hydrogen bond to the main chain carbonyl of HA-T291 and participates in van der Walls interactions by stacking upon HA-P293. Y37 receives a hydrogen bond from the main chain residue HA-K307, donates a hydrogen bond to HA-P293, participates in van der Walls contacts with the aryl group of HA-F294 and the aliphatic side chain of HA-K307.

The structure of the S8V1-157-H4-NB-2010 complex provides a rationale for the genetic features common to this antibody class. The LCDR1 NXYXY motif is germline-encoded by a small subset of IGKV-genes. Of these, only IGKV2-28/IGKV2D-28a also encode a hydrophobic residue at position 55. L55 participates in van der Walls contacts with HA-P293 (Figure 2C) and contributes to a hydrophobic surface on S8V1-157 that complements a hydrophobic patch within its epitope on the HA head (Figure S1). Polar residues present at position 55 in otherwise similar light chains are predicted to be less favorable in this local environment. Similar sequence features are not present in the IGLV locus. Additionally, the short HCDR3 (common among these antibodies) creates shallow cavity that accommodates the hydrophobic surfaces that would normally pack against HA2 in the prefusion HA trimer.

Antibodies to the HA head-stem interface epitope are broadly binding.

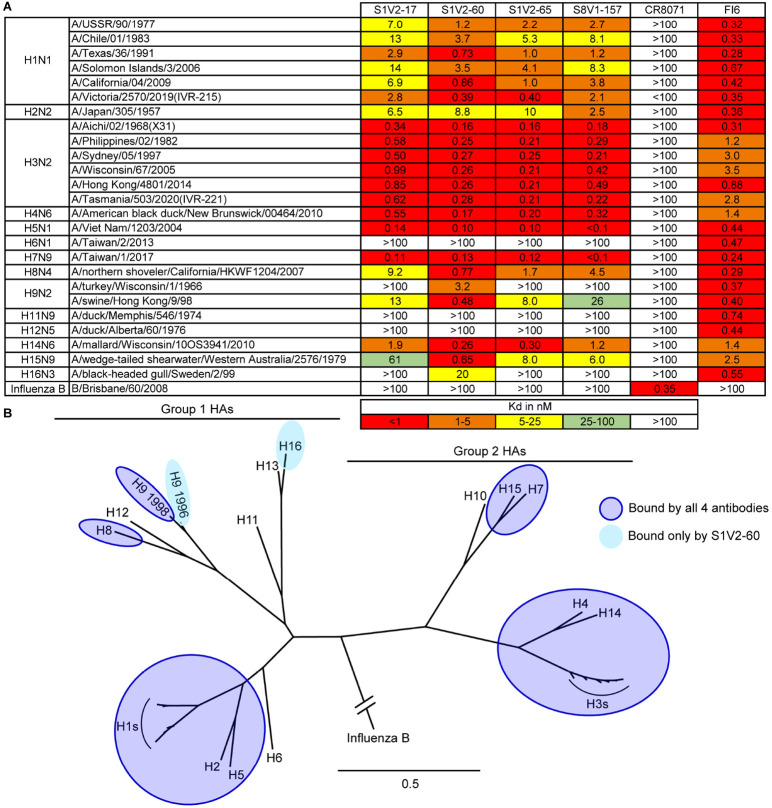

We determined the binding of these antibodies to divergent HA serotypes by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Figures 3A and S2). The HA head-stem epitope antibodies had very similar breadth: each bound all seasonal H1s (1977-2019) and H3s (1968-2020) assayed, and also bound several other HA subtypes within groups 1 and 2. Typically, if an HA was bound by one head-stem epitope antibody it was bound by the remaining three (Figure 3). Affinities and breadth of binding were generally higher for group 2 HAs but extended to group 1 HAs, including seasonal H1, pandemic H2, and pre-pandemic H5 HAs. Overall, these antibodies engaged HAs from 11 of the 16 non-bat influenza A HA serotypes. Failure to engage specific HAs was not due to epitope inaccessibility, since these antibodies also did not bind matched, soluble, HA head domains that present the HA head-stem epitope without steric hindrance (Figures S3 and S4). A truncated HA head domain, lacking the S8V1-157 epitope, was not bound by the four antibodies. All four are likely to engage a common, discrete, epitope comprising the terminal boundaries of the HA head domain.

Figure 3: Breadth of HA binding by HA head-stem epitope antibodies.

A. Equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd), determined by ELISA. Broadly binding influenza A HA antibody FI6v3 30 and influenza B HA antibody CR8071 43 served as binding controls. B. Phylogenetic relationships of HAs used in our panel. HAs bound by HA head-stem epitope antibodies are indicated. Binding data from Figure S3 are incorporated into panel B.

Using a flow cytometry-based assay, we demonstrated that HA head-stem epitope antibodies engage divergent HAs present on the cell surface (Figure 4). HAs were efficiently bound by these antibodies in a pattern consistent with our ELISA data. The intensity of labeling by HA head-stem epitope antibodies was generally lower than for labeling by control antibodies directed to solvent-exposed epitopes on the HA head, but comparable to labeling by the HA head-interface antibody S5V2-29 18. Together, these observations suggest that HA interface epitopes are not as occupied by antibody as are fully exposed epitopes. Epitope accessibility and/or differences in the number of IgG molecules bound per HA may account for these differences. To determine whether S8V1-157 could engage HA0 present on the surface of a cell, cells were transiently transfected with an A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X-31) HA expression vector and assessed for antibody binding using flow cytometry, and HA processing by western blotting cell lysates for its endogenous HA-tag in HA1 (Figure S4 A and B). HA0 was not processed in these cells but was labeled by S8V1-157. The HA head-stem epitope is therefore exposed in biochemical and cellular contexts.

Figure 4: HA head-stem epitope antibodies bind cell surface-anchored HA.

Flow cytometry histograms depict the fluorescence intensities of recombinant IgG binding to K530 cell lines expressing recombinant, native HA on the cell surface. K530 cells were labeled with 400 ng/ml of the four head-stem epitope antibodies or control antibodies targeting the HA receptor binding site (HC1920, K03.1236 and H5.347), the head interface (S5V2-2918), a lateral head epitope (HC45)42, stem (FI6v330), or SARS-CoV spike protein (CR302221). HA abbreviations correspond to: H1/SI06: A/Solomon Islands/3/2006(H1N1), H1/CA09: A/California/04/2009(H1N1), H2/JP57: A/Japan/305/1957(H2N2), H5/VN04: A/Viet Nam/1203/2004(H5N1), H6/TW13: A/Taiwan/2/2013(H6N1), H8/CA07: A/northern shoveler/California/HKWF1204/2007(H8N4),H3/HK68: A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31), H3/TX12: A/Texas/50/2012(H3N2), H4/NB10:A/American black duck/New Brunswick/00464/2010, H7/TW13: A/Taiwan/1/2017(H7N9), H10/JX13: A/Jiangxi/IPB13/2013(H10N8),H14/WI10: A/mallard/Wisconsin/10OS3941/2010(H14N6).

Antibodies to the HA head-stem epitope protect against lethal influenza virus infection.

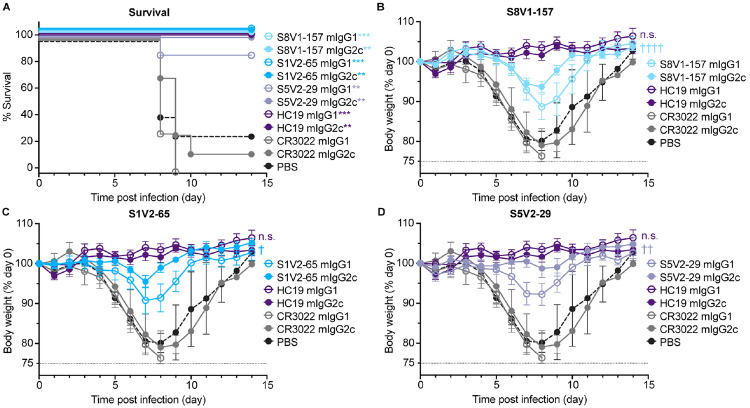

S8V1-157 failed to neutralize influenza virus in vitro (Figure S5). To determine if these antibodies confer protection in vivo we performed a series of prophylactic studies in mice. In a pilot study passive transfer of S8V1-157 antibody conferred moderate protection (Figure S6B). We expanded our studies to include additional control antibodies and to directly assess the impact of antibody IgG subtype on protection. Notably, unlike humans, in mice the antibody IgG2c isotype is capable of directing protective Fc-dependent antibody effector functions, including antibody-dependent-cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement deposition (ADCD). In these experiments we passively transferred 150μg of musinized IgG1 (which has minimal Fc-effector activity) or IgG2c versions of S8V1-157, S5V2-65 (which competes for HA binding with S8V1-157), HC1920 (potently neutralizing A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X-31) specific antibody), S5V2-2918 (an HA-head interface antibody that protects against lethal infection and is enhanced by Fc-dependent mechanisms) and CR302221 (SARS-CoV antibody) to mice prior to challenge with a lethal dose of A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X-31) (Figure S6). The 150μg (~7.5 mg/kg) does is consistent with human monoclonal antibody therapeutics.

HC19 protected mice from any measurable, infection-induced weight loss, while the irrelevant antibody CR3022 offered no protection against weight loss, requiring recipient mice to be ethically euthanized by day 10 post-infection (Figure 5A). Animals administered antibodies to the HA head-stem or head-interface epitope experienced mild weight loss, but nearly all recovered within 10 days post-infection. IgG1 versions of the same antibodies offered slightly less protection than the corresponding IgG2cs. Fc effector functions thus had a role in immune control of the infections (Figure 5B-D). Across our studies, HA head-stem epitope antibodies did not potently inhibit influenza virus infection but did confer strong protection against severe disease and mortality.

Figure 5: HA head-stem epitope antibodies protect against lethal influenza virus infection and severe disease.

C57BL/6 mice (n = 7 per group) were intraperitoneally injected with 150 μg of recombinant antibody via intraperitoneal injection three hours prior to intranasal challenge with 5xLD50 of A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31). Mice were weighed daily and euthanized at a humane endpoint of 25% loss of body weight. Antibodies passively transferred included musinized IgG1 and IgG2c versions of HA head-stem epitope antibodies S8V1-157 and S1V2-65, neutralizing antibody HC1920, head interface antibody S5V2-2918 and SARS-CoV antibody CR302221. Mice injected with PBS were included as an additional control. A. Post-infection survival rate. B-D. Body weight curves for infected mice administered S8V1-157 (B), S1V2-65 (C), or S5V2-29 (D) antibodies, compared with controls. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 compared with isotype control CR3022. Not significant (n.s.), p 0.05; † p < 0.05, †† p < 0.01, and †††† p < 0.0001 IgG2c compared with IgG1.

The HA head-stem epitope is immunogenic in humans.

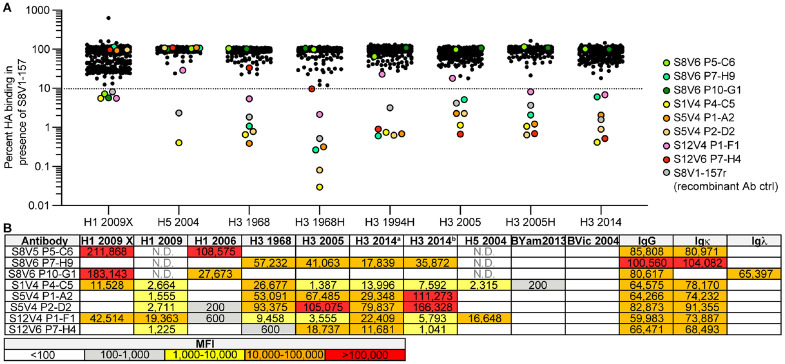

We screened additional human Bmem cell cultures for S8V1-157-competing antibodies (Figure 6). The samples were taken from seven donors, including the same subjects as before (S1, S5, S8, S9), but vaccinated and sampled during subsequent flu seasons (see Materials and Methods for details); subject S12, who was immunized and sampled at the same times; and subjects KEL01 and KEL03, who were sampled after receiving TIV in 2014-2015. From 528 clonal cultures that produced HA-binding IgG, we identified eight additional supernatants that inhibited S8V1-157 binding by >90% (Figure 6A). In a screen of antibody reactivity, five of the eight competing antibodies reacted with group 1 and group 2 HAs.

Figure 6: The HA head-stem epitope epitope is immunogenic in humans.

A. An additional 528 Nojima culture supernatants from donors K01, K03, S1, S5, S8, S9 and S12 were screened for competition with a recombinant musinized S8V1-157 IgG1 for HA binding. Culture supernatants that inhibited S8V1-157 binding by >90% are colored and specified. B. HA reactivity of S8V1-157-competing Nojima culture supernatants, as determined by multiplex Luminex assay. N.D.: not determined.

Paired heavy and light chain sequences were recovered from seven of the eight S8V1-157-competing antibodies (Figure S7). Two antibodies, S1V4-P4-C5 and S12V6-P7-H4, use an IGKV2-28 light chain paired with IGHV1-24*01, like S8V1-157 and S1V2-17. All four antibodies have short, 11-12 amino acid HCDR3s. These features, shared with S8V1-157, likely define a public antibody class present in at least three human donors. The other newly identified S8V1-157 competitors have varied usage of Vh and Vk genes and HCDR3 lengths (10-19 amino acids). These antibodies could either have footprints that overlap the head-stem interface epitope or that prevent its exposure.

DISCUSSION:

We identified and characterized a human antibody response directed to a previously unrecognized, widely conserved, cryptic epitope on the influenza HA head domain. These antibodies bind broadly to divergent HA serotypes found in animals and seasonal antigenic variants of human viruses. Prophylactic passive transfer of these antibodies to mice conferred protection against lethal influenza virus disease. Overall, across our studies we find HA head-stem epitope antibodies comprise ~1% of the circulating, HA-reactive Bmem cell repertoire. Cells with HA head-stem epitope BCRs are present in multiple donors both before and after vaccination against seasonal influenza. These cells have a bias, but not a restriction, for IGKV2-28 usage. Across the 12 known examples we find no additional constraints. Humans are therefore likely to produce similar antibodies and have the capacity to mount polyclonal, poly-epitope, broadly protective antibody responses.

HA head-stem epitope antibodies confer robust protection against lethal influenza challenge, demonstrating that the HA head-stem epitope must be exposed on infected cells and/or virions. Structural, biophysical, and computational approaches indicate that HA trimers transiently adopt conformations that expose epitopes normally occluded in its defined prefusion form10-13. Such transient fluctuations might explain how B cells and antibodies recognize ordinarily occluded epitopes16-18,22-24. A non-mutually exclusive possibility is that head-stem epitope antibodies directly recognize postfusion HA on the surface of infected cells, as has been proposed for some HA stem antibodies, including LAH3117 and m83624 antibodies, whose conformational epitope is present only in the postfusion structure. It is plausible that HA0 is cleaved into HA1/HA2 by proteases and a requisite fraction accumulates in a post-fusion form that would expose this epitope. Nonetheless, in our biochemical assays, and staining of transiently transfected cells, HA head-stem epitope antibodies avidly bound HA0, which cannot fully transition to its stable post fusion structure8.

Humans and mice mount antibody responses directed to seemingly difficult to engage HA epitopes 14-18,22-26. Prevalence of such antibodies in immune repertoires indicates that these epitopes are immunogenic. In this instance, human head-stem interface antibodies typically have ~4-10% V gene mutation frequencies indicating that this epitope is presented, in sufficient abundance, over recurrent influenza exposures. Exposure of the HA head-stem epitope requires large-scale displacement of the HA head that are likely accompanied by other rearrangements of HA protomers. The immunogenicity of the HA head-stem epitope poses a critical question for vaccinology: how does the antigen presented to a B cell in a germinal center reaction relate to its form on infectious virions or to what has been defined in the laboratory in considerable biochemical and structural detail? Antibodies directed to interface/buried epitopes on other unrelated viral glycoproteins demonstrate that our lack of understanding is not specific to HA 27.

The most broadly protective human antibody classes are directed to conserved epitopes with limited antibody accessibility. Adjacent protomers and/or membranes hinder access to stem/anchor epitopes and interface epitopes are normally occluded 2,14,15,28. Nevertheless, antibodies recognizing these epitopes protect against lethal influenza virus disease in small animal models. These antibodies are typically less potently neutralizing than antibodies directed to unhindered sites and their protection is often enhanced by antibody Fc-mediated effector functions 16-18,23,26,29,30. Their resistance to human influenza antigenic evolution and ability to engage emerging, pre-pandemic, and other animal viruses make their selective elicitation a potential strategy to improve current influenza vaccines. Given the promise of these antibodies, a rigorous understanding of their potential to enhance human protective immunity and/or ameliorate disease is needed.

METHODS:

Human subjects.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from human donors KEL01 (male, age 39) and KEL03 (female, age 39), under Duke Institutional Review Board committee guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all three subjects. KEL01 and KEL03 received the trivalent inactivated seasonal influenza vaccine (TIV) 2014-2015 Fluvirin, which contained A/Christchurch/16/2010, NIB-74 (H1N1), A/Texas/50/2012, NYMC X-223 (H3N2), and B/Massachusetts/2/2012, NYMC BX-51B. Blood was drawn on day 14 post-vaccination, and PBMCs isolated by centrifugation over Ficoll density gradients (SepMate-50 tubes, StemCell Tech) were frozen and kept in liquid nitrogen until use.

PBMCs were also obtained from human donors S1 (female, age 51-55), S5 (male, age 21-25), S8 (female, age 26-30), S9 (female, age 51-55), and S12, under Boston University Institutional Review Board committee guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all five subjects. Donors met all of the following inclusion criteria: between 18 and 65 years of age; in good health, as determined by vital signs [heart rate (<100 bpm), blood pressure (systolic ≤ 140 mm Hg and ≥ 90 mm Hg, diastolic ≤ 90 mm Hg), oral temperature (<100.0 °F)] and medical history to ensure existing medical diagnoses/conditions are not clinically significant; can understand and comply with study procedures, and; provided written informed consent prior to initiation of the study. Exclusion criteria included: 1) life-threating allergies, including an allergy to eggs; 2) have ever had a severe reaction after influenza vaccination; 3) a history of Guillain-Barre Syndrome; 4) a history of receiving immunoglobulin or other blood product within the 3 months prior to vaccination in this study; 5) received an experimental agent (vaccine, drug, biologic, device, blood product, or medication) within 1 month prior to vaccination in this study or expect to receive an experimental agent during this study; 6) have received any live licensed vaccines within 4 weeks or inactivated licensed vaccines within 2 weeks prior to the vaccination in this study or plan receipt of such vaccines within 2 weeks following the vaccination; 7) have an acute or chronic medical condition that might render vaccination unsafe, or interfere with the evaluation of humoral responses (includes, but is not limited to, known cardiac disease, chronic liver disease, significant renal disease, unstable or progressive neurological disorders, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disorders and transplant recipients); 8) have an acute illness, including an oral temperature greater than 99.9°F, within 1 week of vaccination; 9) active HIV, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C infection; 10) a history of alcohol or drug abuse in the last 5 years; 11) a history of a coagulation disorder or receiving medications that affect coagulation. Subjects S1, S5, S8, S9, and S12 received seasonal influenza vaccination during three consecutive North American flu seasons (2015-2016, 2016-2017, 2017-2018), and had blood drawn on day 0 (pre-vaccination; visits 1, 3, and 5) and day 7 (post-vaccination, visits 2, 4, and 6) each year. During the 2015-2016 season (visits 1 and 2), the subjects received the TIV Fluvirin, which contained A/reassortant/NYMC X-181 (California/07/2009 x NYMC X-157) (H1N1), A/South Australia/55/2014 IVR-175 (H3N2), and B/Phuket/3073/2013. During the 2016-2017 season (visits 3 and 4), the subjects received the quadrivalent inactivated vaccine Flucelvax, containing A/Brisbane/10/2010 (H1N1), A/Hong Kong /4801/2014 (H3N2), B/Utah/9/2014, and B/Hong Kong/259/2010. During the 2017-2018 season (visits 5 and 6), the subjects received the quadrivalent inactivated vaccine Flucelvax, containing A/Singapore/GP1908/2015 IVR-180 (H1N1), A/Singapore/GP2050/2015 (H3N2), B/Utah/9/2014, and B/Hong Kong/259/2010.

Cell lines.

Human 293F cells were maintained at 37°C with 5-8% CO2 in FreeStyle 293 Expression Medium (ThermoFisher) supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin. HA-expressing K530 cell lines 31 (Homo sapiens) were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 medium plus 10% FBS (Cytiva), 2-mercaptoethanol (55 μM; Gibco), penicillin, streptomycin, HEPES (10 mM; Gibco), sodium pyruvate (1 mM; Gibco), and MEM nonessential amino acids (Gibco). Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) were maintained in Minimum Essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 5 mM L-glutamine and 5 mM penicillin/streptomycin.

Recombinant Fab expression and purification.

The heavy and light chain variable domain genes for Fabs were cloned into a modified pVRC8400 expression vector, as previously described32-34. Fab fragments used in crystallization were produced with a noncleavable 6xhistidine (6xHis) tag on the heavy chain C-terminus. Fab fragments were produced by polyethylenimine (PEI) facilitated, transient transfection of 293F cells. Transfection complexes were prepared in Opti-MEM (Gibco) and added to cells. 5 days post transfection, cell supernatants were harvested and clarified by low-speed centrifugation. Fabs were purified by passage over TALON Metal Affinity Resin (Takara) followed by gel filtration chromatography on Superdex 200 (GE Healthcare) in 10 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (tris), 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.5 (buffer A).

Single B cell Nojima cultures.

Nojima cultures were previously performed18 and in Finney et al., in press at PNAS. Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from four human subjects S1 (female, age range 51-55), S5 (male, age 21-25), S8 (female, age 26-30), and S9 (female, age 51-55). Single human Bmem cells were directly sorted into each well of 96-well plates and cultured with MS40L-low feeder cells in RPMI1640 (Invitrogen) containing 10% HyClone FBS (Thermo scientific), 2-mercaptoethanol (55 μM), penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), HEPES (10 mM), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), and MEM nonessential amino acid (1X; all Invitrogen). Exogenous recombinant human IL-2 (50 ng/ml), IL-4 (10 ng/ml), IL-21 (10 ng/ml) and BAFF (10 ng/ml; all Peprotech) were added to cultures. Cultures were maintained at 37° degrees Celsius with 5% CO2. Half of the culture medium was replaced twice weekly with fresh medium (with fresh cytokines). Rearranged V(D)J gene sequences for human Bmem cells from single-cell cultures were obtained as described18,32,35. Specificity of clonal IgG antibodies in culture supernatants and of rIgG antibodies were determined in a multiplex bead Luminex assay (Luminex Corp.). Culture supernatants and rIgGs were serially diluted in 1 × PBS containing 1% BSA, 0.05% NaN3 and 0.05% Tween20 (assay buffer) with 1% milk and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with the mixture of antigen-coupled microsphere beads in 96-well filter bottom plates (Millipore). After washing three times with assay buffer, beads were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with Phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibodies (Southern Biotech). After three washes, the beads were re-suspended in assay buffer and the plates read on a Bio-Plex 3D Suspension Array System (Bio-Rad).

Recombinant HA expression and purification.

Recombinant HA head domain constructs and Full-length HA ectodomains (FLsE) were expressed by polyethylenimine (PEI) facilitated, transient transfection of 293F cells. To clone HA head domains, synthetic DNA for the domain was subcloned into a pVRC8400 vector encoding a C-terminal rhinovirus 3C protease site and a 6xHis tag. To produce FLsE constructs, synthetic DNA was subcloned into a pVRC8400 vector encoding a T4 fibritin (foldon) trimerization tag and a 6xHis tag. Transfection complexes were prepared in Opti-MEM (Gibco) and added to cells. 5 days post transfection, cell supernatants were harvested and clarified by low-speed centrifugation. HA was purified by passage over TALON Metal Affinity Resin (Takara) followed by gel filtration chromatography on Superdex 200 (GE Healthcare) in buffer A. HA head domains used for crystallography underwent the following additional purification steps. HA heads were cleaved using the Pierce 3C HRV Protease Solution Kit (Ref 88947) and passed over TALON Metal Affinity Resin to capture cleaved tags. Cleaved HA heads were then further purified by gel filtration chromatography on Superdex 200 (GE Healthcare) in buffer A.

ELISA

Five hundred nanograms of rHA FLsE or HA head domain were adhered to high-capacity binding, 96 well-plates (Corning 9018) overnight in PBS pH 7.4 at 4°C. HA coated plates were washed with a PBS-Tween-20 (0.05%v/v) buffer (PBS-T) and then blocked with PBS-T containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Blocking solution was then removed, and 5-fold dilutions of IgGs (in blocking solution) were added to wells. Plates were then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary IgG solution was removed and plates were washed three times with PBS-T. Secondary antibody, anti-human IgG-HRP (Abcam ab97225) diluted 1:10,000 in blocking solution, was added to wells and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Plates were then washed three times with PBS-T. Plates were developed using 150μl 1-Step ABTS substrate (ThermoFisher, Prod#37615). Following a brief incubation at room temperature, HRP reactions were stopped by the addition of 100μl of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution. Plates were read on a Molecular Devices SpectraMax 340PC384 Microplate Reader at 405 nm. KD values for ELISA were obtained as follows. All measurements were performed in technical triplicate. The average background signal (no primary antibody) was subtracted from all absorbance values. Values from multiple plates were normalized to the FI6v330 standard (FluA20 was used for the HA head assays) that was present on each ELISA plate. The average of the three measurements were then graphed using GraphPad Prism (v9.0). KD values were determined by applying a nonlinear fit (One site binding, hyperbola) to these data points. The constraint that Bmax must be greater than 0.1 absorbance units was applied to all KD analysis parameters.

Recombinant IgG expression and purification.

The heavy and light chain variable domains of selected antibodies were cloned into modified pVRC8400 expression vectors to produce full length human IgG1 heavy chains and human lambda or kappa light chains. IgGs were produced by transient transfection of 293F cells as specified above. Five days post-transfection supernatants were harvested, clarified by low-speed centrifugation, and incubated overnight with Protein A Agarose Resin (GoldBio) at 4°C. The resin was collected in a chromatography column and washed with one column volume of buffer A. IgGs were eluted in 0.1M Glycine (pH 2.5) which was immediately neutralized by 1M tris (pH 8.5). Antibodies were then dialyzed against phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4.

Recombinant mIgG expression and endotoxin free purification.

The heavy and light chain variable domains of selected antibodies were cloned into respective modified pVRC8400 expression vector to produce full length murine IgG1 and IgG2C heavy chains and murine lambda or kappa light chains. IgGs were produced by transient transfection of 293F cells as specified above. Five days post-transfection supernatants were harvested, clarified by low-speed centrifugation. 20% volume of 1M 2-morpholin-4-ylethanesulfonic acid (MES) pH 5 and Immobilized Protein G resin (Thermo Scientific Prod#20397) were added to supernatant and sample was incubated overnight at 4°C. The resin was collected in a chromatography column and washed with one column volume of 10mM MES, 150 mM NaCl at pH 5. mIgGs were eluted in 0.1M Glycine (pH 2.5), which was immediately neutralized by 1M tris (pH 8.5). Antibodies were then dialyzed against phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4. All mIgGs administered to mice were purified using buffers made with endotoxin-free water (HyPure Cell Culture Grade Water, Cytiva SH30529.03) and were dialyzed into endotoxin-free Dulbecco’s PBS (EMD Millipore, TMS-012-A). Following dialysis, endotoxins were removed using Pierce High Capacity Endotoxin Removal Spin Columns (Ref 88274).

Virus microneutralization assays.

Two-fold serial dilutions of 50 ug/mL of HC19, S8V1-157 or CR3022 were incubated with 103.3 TCID50 of A/Aichi/02/1968 H3N2 (X-31) influenza virus for 1 hour at room temperature with continuous rocking. Media with TPCK was added to 96-well plates with confluent MDCK cells before the virus:serum mixture was added. After 4 days, CPE was determined and the neutralizing antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum required to completely neutralize the infectivity each virus on MDCK cells. The concentration of antibody required to neutralize 100 TCID50 of virus was calculated based on the neutralizing titer dilution divided by the initial dilution factor, multiplied by the antibody concentration.

Protection:

C57BL/6 female and male mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions at Duke University Animal Care Facility. Eight to 10-week old mice were injected i.p. with 150 μg of recombinant antibody diluted to 200 μl in PBS. Three hours later, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine (85 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) and infected intranasally with 3×LD50 (1.5×104 PFU) of A/Aichi/2/1968 X-31 (H3N2) in 40 μL total volume (20 μL/nostril). Mice were monitored daily for survival and body weight loss until 14 days post-challenge. The humane endpoint was set at 20% body weight loss relative to the initial body weight at the time of infection. All animal experiments were approved by the standards and guidance set forth by Duke University IACUC.

Female C57BL/6J mice at 8 weeks old, purchased from Japan SLC, were i.p. injected with 150 μg of the antibodies in 150 μL PBS. Three hours later, the mice were intranasally infected with 5LD50 of A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31), kindly gifted from Dr. Takeshi Tsubata (Tokyo Medical and Dental University), under anesthesia with medetomidine-midazolam-butorphanol. Survival and body weight were daily assessed for 14 days with a humane endpoint set as 25% weight loss from the initial body weight. The experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan, and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Statistical significance of body weight change and survival of mice after lethal influenza challenge was calculated by Two-way ANOVA test and Mantel-Cox test, respectively, using GraphPad Prism (v10.0) software

Competitive inhibition assay

Competitive binding inhibition was determined by a Luminex assay, essentially as described18,36. Briefly, serially diluted human rIgGs or diluted (1:10) Bmem cell culture supernatants were incubated with HA-conjugated Luminex microspheres for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. S8V1-157 mouse IgG1 was then added at a fixed concentration (100 ng/ml final for competition with rIgGs, or 10 ng/ml final for competition with culture supernatants) to each well, and incubated with the competitor Abs and HA-microspheres for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, bound S8V1-157 was detected by incubating the microspheres with 2 μg/ml PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG1 (SB77e, SouthernBiotech) for 1 hr at room temperature, followed by washing and data collection. Irrelevant rIgG or culture supernatants containing HA-nonbinding IgG were used as non-inhibiting controls.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry analysis of rIgG binding to HA-expressing K530 cell lines was performed essentially as described 31. Briefly, K530 cell lines were thawed from cryopreserved aliquots and expanded in culture for ≥3 days. Pooled K530 cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 min with 0.4 μg/ml recombinant human IgGs diluted in PBS plus 2% fetal bovine serum. After washing, cells were labeled with 2 μg/ml PE-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Southern Biotech) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed and analyzed with a BD FACSymphony A5 flow cytometer. Flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo software (BD).

Flow cytometry analysis of rIgG binding to HA-expressing 293F cells was performed as follows. 293F cells were transfected using PEI with either plasmid encoding full-length HA from A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31) or with empty vector. 36 hours post-transfection, cells were incubated at 4°C for one hour with 0.4 μg/ml recombinant human IgGs diluted in PBS plus 2% fetal bovine serum. After washing, cells were labeled with BB515 mouse anti-human IgG (BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C at the manufacturer’s recommended concentration, followed by washing and fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde. Cells were analyzed with a BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer. Flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo software (BD).

Western blots

293F cells were transfected using PEI with either plasmid encoding full-length HA from A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31) or with empty vector. 24 hours post-transfection, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (25mM Tris pH7.6, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP40 alternative, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS). Cell lysates were clarified of debris and boiled with Laemmli buffer with 2-mercaptoethanol. Samples were run on 4-20% acrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 and probed with anti-HA tag antibody (Thermo-Fisher A01244-100; 0.3 μg/ml), followed by IR800-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (LiCor 926-32210; 0.1 μg/ml) and DyLight680-conjugated mouse anti-rabbit GAPDH antibody (BioRad MCA4739D680; 0.3 μg/ml). Membranes were imaged using a LiCor Odyssey CLx imager.

Crystallization

S1V2-157 Fab fragments were co-concentrated with the HA-head domain of A/American black duck/New Brunswick/00464/2010(H4N6) at a molar ratio of ~1:1.3 (Fab to HA-head) to a final concentration of ~20 mg/ml. Crystals of Fab-head complexes were grown in hanging drops over a reservoir solutions containing 0.1 M Lithium sulfate, 0.1 M Sodium chloride, 0.1 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) pH 6.5 and 30% (v/v) poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) 400. Crystals were cryprotected with 30% (v/v) PEG 400, 0.12 M Lithium sulfate, 0.3 M Sodium chloride, and 0.06 M MES pH 6.5. Cryprotectant was added directly to the drop, crystals were harvested, and flash cooled in liquid nitrogen.

Structure determination and refinement

We recorded diffraction data at the Advanced Photon Source on beamline 24-ID-C. Data were processed and scaled (XSCALE) with XDS37. Molecular replacement was carried out with PHASER38, dividing each complex into four search models (HA-head, Vh, Vl and constant domain). Search models were 5XL2, 6EIK , 5BK5 and 6E56.We carried out refinement calculations with PHENIX39 and model modifications, with COOT40. Refinement of atomic positions and B factors was followed by translation-liberation-screw (TLS) parameterization. All placed residues were supported by electron density maps and subsequent rounds of refinement. Final coordinates were validated with the MolProbity server41. Data collection and refinement statistics are in Table S1. Figures were made with PyMOL (Schrödinger, New York, NY.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Table 1: Data collection and refinement statistics.

Figure S1: Surface hydrophobicity on the HA molecule. Surface hydrophobicity and the head-stem epitope are shown on the HA trimer of A/American black duck/New Brunswick/00464/2010(H4N6) (PDB: 5XL2) 19. Coloring is based on the PyMOL Color h script that utilizes a normalized consensus hydrophobicity scale48. Views and orientations match those in Figure 2. The head-stem epitope is circled in the far right panel.

Figure S2: ELISA titrations of antibodies on HA coated plates. The broadly binding stem antibody FI6v330 was used as a positive control and an influenza B specific head antibody, CR807143, as a negative control for influenza A isolates. Data points represent the average of three technical replicates. The standard error of the mean is shown for each point. KDs were calculated from the curves fit to these data points.

Figure S3: Head-stem epitope antibody binding to HA head-only domains. A. Structures of HA head domains used in these experiments the S8V1-157-HA head complex is shown for reference. A compact head domain33 , is shown for reference (PDB 7TRH). B. HA heads for HAs not bound or not expressed in Figure 3 were produced alongside a positive control A/California/07/2009(H1N1)(X-181) and a compact head version. Sequences of the HA head domains are aligned to the A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X-31) reference sequence and numbered by H3 convention. C. Dissociation constants from ELISA measurements of head-stem epitope antibodies to HA head domains. Head interface antibody FluA-2023 was used as a positive control and influenza B head antibody CR807143 as a negative control.

Figure S4: ELISA titrations of antibodies on HA head coated plates and characterization of cell expressed HA. A. Head interface antibody FluA-2023 was used as a positive control and influenza B head antibody CR807143 as a negative control. Data points represent the average of three technical replicates. The standard error of the mean is shown for each point. KDs were calculated from the curves fit to these data points. B. Lysates from 293F transfected with either HA from A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31) or empty vector were subjected to western blotting with either anti-HA tag antibody, which recognizes an endogenous sequence in the H3 HA head (HA1), or anti-GAPDH antibody. Molecular weights of unprocessed HA0 and processed HA1 are indicated with open or closed arrowheads, respectively. C. 293F transfected with either HA from A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31) or empty vector were stained with the indicated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. Gates denoting cells bound by antibody are shown, with the percent of the total population indicated above.

Figure S5: S8V1-157 is a non-neutralizing antibody. Neutralization IC50 values for S8V1-157, neutralizing antibody HC1920 (positive control) and SARS-CoV antibody CR302221 (negative control).

Figure S6: S8V1-157 protects against lethal influenza virus infection. C57BL/6 mice received a passive transfer of 100μg of recombinant antibody via intraperitoneal injection three hours prior to challenge with a 3xLD50 of A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31) administered intranasally. Mice were monitored for survival (A) and weight loss (B). Mice were sacrificed at a humane endpoint of 25% loss of body weight. Antibodies passively transferred include musinized IgG2c versions of HA head-stem epitope antibody S8V1-157 (n=6), neutralizing antibody HC1920 (n=4), and SARS-CoV antibody CR302221 (n=4).

Figure S7: Antibody genetics of S8V1-157 competing antibodies. Antibody names, gene usage and HCDR3 sequences for S8V1-157 competing antibodies identified in Figure 6.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

We thank the many members of our Program Project Consortium for advice and discussion. X-ray diffraction data were recorded at beamline ID-24-C (operated by the Northeast Collaborative Access team: NE-CAT) at the Advanced Photon Source (APS, Argonne National Laboratory). We thank NE-CAT staff members for advice and assistance in data collection. NE-CAT is funded by NIH grant P30 GM124165. APS is operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. The research was supported by NIAID Program Project Grant P01 AI089618 (to G.H.K.), funds from the University of Pittsburgh Center for Vaccine Research (to K.R.M), and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development grant JP22fk0108141 (to Y.A. and Y.T.)

Footnotes

REFERENCES:

- 1.Knossow M., and Skehel J.J. (2006). Variation and infectivity neutralization in influenza. Immunology 119, 1–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02421.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu N.C., and Wilson I.A. (2020). Influenza Hemagglutinin Structures and Antibody Recognition. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10. 10.1101/cshperspect.a038778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krammer F., Palese P., and Steel J. (2015). Advances in universal influenza virus vaccine design and antibody mediated therapies based on conserved regions of the hemagglutinin. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 386, 301–321. 10.1007/82_2014_408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krammer F., Garcia-Sastre A., and Palese P. (2018). Is It Possible to Develop a "Universal" Influenza Virus Vaccine? Potential Target Antigens and Critical Aspects for a Universal Influenza Vaccine. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10. 10.1101/cshperspect.a028845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erbelding E.J., Post D.J., Stemmy E.J., Roberts P.C., Augustine A.D., Ferguson S., Paules C.I., Graham B.S., and Fauci A.S. (2018). A Universal Influenza Vaccine: The Strategic Plan for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J Infect Dis 218, 347–354. 10.1093/infdis/jiy103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox R.J. (2013). Correlates of protection to influenza virus, where do we go from here? Hum Vaccin Immunother 9, 405–408. 10.4161/hv.22908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skehel J.J., Bizebard T., Bullough P.A., Hughson F.M., Knossow M., Steinhauer D.A., Wharton S.A., and Wiley D.C. (1995). Membrane fusion by influenza hemagglutinin. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 60, 573–580. 10.1101/sqb.1995.060.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skehel J.J., and Wiley D.C. (2000). Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem 69, 531–569. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissenhorn W., Dessen A., Calder L.J., Harrison S.C., Skehel J.J., and Wiley D.C. (1999). Structural basis for membrane fusion by enveloped viruses. Mol Membr Biol 16, 3–9. 10.1080/096876899294706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benton D.J., Gamblin S.J., Rosenthal P.B., and Skehel J.J. (2020). Structural transitions in influenza haemagglutinin at membrane fusion pH. Nature 583, 150–153. 10.1038/s41586-020-2333-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das D.K., Govindan R., Nikic-Spiegel I., Krammer F., Lemke E.A., and Munro J.B. (2018). Direct Visualization of the Conformational Dynamics of Single Influenza Hemagglutinin Trimers. Cell 174, 926–937 e912. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casalino L., Seitz C., Lederhofer J., Tsybovsky Y., Wilson I.A., Kanekiyo M., and Amaro R.E. (2022). Breathing and Tilting: Mesoscale Simulations Illuminate Influenza Glycoprotein Vulnerabilities. ACS Cent Sci 8, 1646–1663. 10.1021/acscentsci.2c00981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia N.K., Kephart S.M., Benhaim M.A., Matsui T., Mileant A., Guttman M., and Lee K.K. (2023). Structural dynamics reveal subtype-specific activation and inhibition of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Biol Chem 299, 104765. 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.104765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guthmiller J.J., Han J., Utset H.A., Li L., Lan L.Y., Henry C., Stamper C.T., McMahon M., O'Dell G., Fernandez-Quintero M.L., et al. (2022). Broadly neutralizing antibodies target a haemagglutinin anchor epitope. Nature 602, 314–320. 10.1038/s41586-021-04356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benton D.J., Nans A., Calder L.J., Turner J., Neu U., Lin Y.P., Ketelaars E., Kallewaard N.L., Corti D., Lanzavecchia A., et al. (2018). Influenza hemagglutinin membrane anchor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 10112–10117. 10.1073/pnas.1810927115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adachi Y., Tonouchi K., Nithichanon A., Kuraoka M., Watanabe A., Shinnakasu R., Asanuma H., Ainai A., Ohmi Y., Yamamoto T., et al. (2019). Exposure of an occluded hemagglutinin epitope drives selection of a class of cross-protective influenza antibodies. Nat Commun 10, 3883. 10.1038/s41467-019-11821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tonouchi K., Adachi Y., Suzuki T., Kuroda D., Nishiyama A., Yumoto K., Takeyama H., Suzuki T., Hashiguchi T., and Takahashi Y. (2023). Structural basis for cross-group recognition of an influenza virus hemagglutinin antibody that targets postfusion stabilized epitope. PLoS Pathog 19, e1011554. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe A., McCarthy K.R., Kuraoka M., Schmidt A.G., Adachi Y., Onodera T., Tonouchi K., Caradonna T.M., Bajic G., Song S., et al. (2019). Antibodies to a Conserved Influenza Head Interface Epitope Protect by an IgG Subtype-Dependent Mechanism. Cell 177, 1124–1135 e1116. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song H., Qi J., Xiao H., Bi Y., Zhang W., Xu Y., Wang F., Shi Y., and Gao G.F. (2017). Avian-to-Human Receptor-Binding Adaptation by Influenza A Virus Hemagglutinin H4. Cell Rep 20, 1201–1214. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleury D., Wharton S.A., Skehel J.J., Knossow M., and Bizebard T. (1998). Antigen distortion allows influenza virus to escape neutralization. Nat Struct Biol 5, 119–123. 10.1038/nsb0298-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ter Meulen J., van den Brink E.N., Poon L.L., Marissen W.E., Leung C.S., Cox F., Cheung C.Y., Bakker A.Q., Bogaards J.A., van Deventer E., et al. (2006). Human monoclonal antibody combination against SARS coronavirus: synergy and coverage of escape mutants. PLoS Med 3, e237. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zost S.J., Dong J., Gilchuk I.M., Gilchuk P., Thornburg N.J., Bangaru S., Kose N., Finn J.A., Bombardi R., Soto C., et al. (2021). Canonical features of human antibodies recognizing the influenza hemagglutinin trimer interface. J Clin Invest 131. 10.1172/JCI146791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bangaru S., Lang S., Schotsaert M., Vanderven H.A., Zhu X., Kose N., Bombardi R., Finn J.A., Kent S.J., Gilchuk P., et al. (2019). A Site of Vulnerability on the Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin Head Domain Trimer Interface. Cell 177, 1136–1152 e1118. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu F., Song H., Wu Y., Chang S.Y., Wang L., Li W., Hong B., Xia S., Wang C., Khurana S., et al. (2017). A Potent Germline-like Human Monoclonal Antibody Targets a pH-Sensitive Epitope on H7N9 Influenza Hemagglutinin. Cell Host Microbe 22, 471–483 e475. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarthy K.R., Lee J., Watanabe A., Kuraoka M., Robinson-McCarthy L.R., Georgiou G., Kelsoe G., and Harrison S.C. (2021). A Prevalent Focused Human Antibody Response to the Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin Head Interface. mBio 12, e0114421. 10.1128/mBio.01144-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bajic G., Maron M.J., Adachi Y., Onodera T., McCarthy K.R., McGee C.E., Sempowski G.D., Takahashi Y., Kelsoe G., Kuraoka M., and Schmidt A.G. (2019). Influenza Antigen Engineering Focuses Immune Responses to a Subdominant but Broadly Protective Viral Epitope. Cell Host Microbe 25, 827–835 e826. 10.1016/j.chom.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y., and Gao G.F. (2019). "Breathing" Hemagglutinin Reveals Cryptic Epitopes for Universal Influenza Vaccine Design. Cell 177, 1086–1088. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otterstrom J.J., Brandenburg B., Koldijk M.H., Juraszek J., Tang C., Mashaghi S., Kwaks T., Goudsmit J., Vogels R., Friesen R.H., and van Oijen A.M. (2014). Relating influenza virus membrane fusion kinetics to stoichiometry of neutralizing antibodies at the single-particle level. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, E5143–5148. 10.1073/pnas.1411755111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiLillo D.J., Tan G.S., Palese P., and Ravetch J.V. (2014). Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcgammaR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med 20, 143–151. 10.1038/nm.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corti D., Voss J., Gamblin S.J., Codoni G., Macagno A., Jarrossay D., Vachieri S.G., Pinna D., Minola A., Vanzetta F., et al. (2011). A neutralizing antibody selected from plasma cells that binds to group 1 and group 2 influenza A hemagglutinins. Science 333, 850–856. 10.1126/science.1205669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song S., Manook M., Kwun J., Jackson A.M., Knechtle S.J., and Kelsoe G. (2021). A cell-based multiplex immunoassay platform using fluorescent protein-barcoded reporter cell lines. Commun Biol 4, 1338. 10.1038/s42003-021-02881-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarthy K.R., Raymond D.D., Do K.T., Schmidt A.G., and Harrison S.C. (2019). Affinity maturation in a human humoral response to influenza hemagglutinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 10.1073/pnas.1915620116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt A.G., Xu H., Khan A.R., O'Donnell T., Khurana S., King L.R., Manischewitz J., Golding H., Suphaphiphat P., Carfi A., et al. (2013). Preconfiguration of the antigen-binding site during affinity maturation of a broadly neutralizing influenza virus antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 264–269. 10.1073/pnas.1218256109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt A.G., Therkelsen M.D., Stewart S., Kepler T.B., Liao H.X., Moody M.A., Haynes B.F., and Harrison S.C. (2015). Viral receptor-binding site antibodies with diverse germline origins. Cell 161, 1026–1034. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuraoka M., Schmidt A.G., Nojima T., Feng F., Watanabe A., Kitamura D., Harrison S.C., Kepler T.B., and Kelsoe G. (2016). Complex Antigens Drive Permissive Clonal Selection in Germinal Centers. Immunity 44, 542–552. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCarthy K.R., Watanabe A., Kuraoka M., Do K.T., McGee C.E., Sempowski G.D., Kepler T.B., Schmidt A.G., Kelsoe G., and Harrison S.C. (2018). Memory B Cells that Cross-React with Group 1 and Group 2 Influenza A Viruses Are Abundant in Adult Human Repertoires. Immunity 48, 174–184 e179. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kabsch W. (2010). Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 125–132. 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCoy A.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Adams P.D., Winn M.D., Storoni L.C., and Read R.J. (2007). Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr 40, 658–674. 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkoczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Hung L.W., Kapral G.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., et al. (2010). PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 213–221. 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P., and Cowtan K. (2004). Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132. 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen V.B., Arendall W.B. 3rd, Headd J.J., Keedy D.A., Immormino R.M., Kapral G.J., Murray L.W., Richardson J.S., and Richardson D.C. (2010). MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 12–21. 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bizebard T., Gigant B., Rigolet P., Rasmussen B., Diat O., Bosecke P., Wharton S.A., Skehel J.J., and Knossow M. (1995). Structure of influenza virus haemagglutinin complexed with a neutralizing antibody. Nature 376, 92–94. 10.1038/376092a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dreyfus C., Laursen N.S., Kwaks T., Zuijdgeest D., Khayat R., Ekiert D.C., Lee J.H., Metlagel Z., Bujny M.V., Jongeneelen M., et al. (2012). Highly conserved protective epitopes on influenza B viruses. Science 337, 1343–1348. 10.1126/science.1222908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ekiert D.C., Friesen R.H., Bhabha G., Kwaks T., Jongeneelen M., Yu W., Ophorst C., Cox F., Korse H.J., Brandenburg B., et al. (2011). A highly conserved neutralizing epitope on group 2 influenza A viruses. Science 333, 843–850. 10.1126/science.1204839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashkenazy H., Abadi S., Martz E., Chay O., Mayrose I., Pupko T., and Ben-Tal N. (2016). ConSurf 2016: an improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res 44, W344–350. 10.1093/nar/gkw408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Celniker G., Nimrod G., Ashkenazy H., Glaser F., Martz E., Mayrose I., Pupko T., and Ben-Tal N. (2013). ConSurf: Using Evolutionary Data to Raise Testable Hypotheses about Protein Function. Israel Journal of Chemistry 53, 199–206. 10.1002/ijch.201200096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winarski K.L., Thornburg N.J., Yu Y., Sapparapu G., Crowe J.E. Jr., and Spiller B.W. (2015). Vaccine-elicited antibody that neutralizes H5N1 influenza and variants binds the receptor site and polymorphic sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 9346–9351. 10.1073/pnas.1502762112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisenberg D., Schwarz E., Komaromy M., and Wall R. (1984). Analysis of membrane and surface protein sequences with the hydrophobic moment plot. J Mol Biol 179, 125–142. 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Table 1: Data collection and refinement statistics.

Figure S1: Surface hydrophobicity on the HA molecule. Surface hydrophobicity and the head-stem epitope are shown on the HA trimer of A/American black duck/New Brunswick/00464/2010(H4N6) (PDB: 5XL2) 19. Coloring is based on the PyMOL Color h script that utilizes a normalized consensus hydrophobicity scale48. Views and orientations match those in Figure 2. The head-stem epitope is circled in the far right panel.

Figure S2: ELISA titrations of antibodies on HA coated plates. The broadly binding stem antibody FI6v330 was used as a positive control and an influenza B specific head antibody, CR807143, as a negative control for influenza A isolates. Data points represent the average of three technical replicates. The standard error of the mean is shown for each point. KDs were calculated from the curves fit to these data points.

Figure S3: Head-stem epitope antibody binding to HA head-only domains. A. Structures of HA head domains used in these experiments the S8V1-157-HA head complex is shown for reference. A compact head domain33 , is shown for reference (PDB 7TRH). B. HA heads for HAs not bound or not expressed in Figure 3 were produced alongside a positive control A/California/07/2009(H1N1)(X-181) and a compact head version. Sequences of the HA head domains are aligned to the A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X-31) reference sequence and numbered by H3 convention. C. Dissociation constants from ELISA measurements of head-stem epitope antibodies to HA head domains. Head interface antibody FluA-2023 was used as a positive control and influenza B head antibody CR807143 as a negative control.

Figure S4: ELISA titrations of antibodies on HA head coated plates and characterization of cell expressed HA. A. Head interface antibody FluA-2023 was used as a positive control and influenza B head antibody CR807143 as a negative control. Data points represent the average of three technical replicates. The standard error of the mean is shown for each point. KDs were calculated from the curves fit to these data points. B. Lysates from 293F transfected with either HA from A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31) or empty vector were subjected to western blotting with either anti-HA tag antibody, which recognizes an endogenous sequence in the H3 HA head (HA1), or anti-GAPDH antibody. Molecular weights of unprocessed HA0 and processed HA1 are indicated with open or closed arrowheads, respectively. C. 293F transfected with either HA from A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31) or empty vector were stained with the indicated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. Gates denoting cells bound by antibody are shown, with the percent of the total population indicated above.

Figure S5: S8V1-157 is a non-neutralizing antibody. Neutralization IC50 values for S8V1-157, neutralizing antibody HC1920 (positive control) and SARS-CoV antibody CR302221 (negative control).

Figure S6: S8V1-157 protects against lethal influenza virus infection. C57BL/6 mice received a passive transfer of 100μg of recombinant antibody via intraperitoneal injection three hours prior to challenge with a 3xLD50 of A/Aichi/02/1968(H3N2)(X31) administered intranasally. Mice were monitored for survival (A) and weight loss (B). Mice were sacrificed at a humane endpoint of 25% loss of body weight. Antibodies passively transferred include musinized IgG2c versions of HA head-stem epitope antibody S8V1-157 (n=6), neutralizing antibody HC1920 (n=4), and SARS-CoV antibody CR302221 (n=4).

Figure S7: Antibody genetics of S8V1-157 competing antibodies. Antibody names, gene usage and HCDR3 sequences for S8V1-157 competing antibodies identified in Figure 6.