Abstract

Surgical repair or reconstruction of the lateral ligaments for patients with chronic ankle instability (CAI) could, logically, restore the proprioception of ankle through retensing receptors. To validate this hypothesis, seven databases were systematically searched, and thirteen studies comprising a total of 347 patients with CAI were included. Although five studies reported improved proprioceptive outcomes after surgeries, the other five studies with between-limb/group comparisons reported residual deficits at final follow-up, which does not consistently support proprioceptive recovery after existing surgical restabilization for CAI. More controlled studies are needed to provide evidence-based protocols to improve proprioceptive recovery after ankle restabilization for CAI.

Key Terms: Ankle, Ligaments, Orthopedics, Proprioception, Postural balance, Systematic review

1. Introduction

Ankle sprain is the most common sports injury, predominantly affecting the lateral ligaments of the ankle (i.e., anterior talofibular ligament [ATFL] and/or calcaneofibular ligament [CFL]).1,2 Although the initial ankle sprains of most patients can fully resolve without sequelae, about one-third of patients develop chronic ankle instability (CAI), with the persistent symptoms of the ankle “giving way”, repeated sprains, and self-reported feelings of ankle instability.1,2 Sprains may damage not only the mechanical stability of the capsule-ligamentous structures but also the integrity of the ankle sensorimotor functions simultaneously, referred to as mechanical and functional insufficiencies, respectively.1 There is a consensus that both mechanical and functional insufficiencies should be carefully considered during the clinical management of CAI; thus, to obtain satisfying outcomes, multimodal treatments are needed.3,4

Most patients suffering from functional insufficiencies of CAI can be managed by a comprehensive exercise-based physiotherapy program, which not only can retrain sensorimotor ability but can also compensate for slight joint laxity.5,6 However, for patients who fail conservative treatment of longer than 3 months and who are diagnosed with torn ligaments (i.e., severe mechanical insufficiencies), surgical repair or reconstruction of the ATFL and/or CFL are recommended to restore the mechanical deficits and provide stable ankle kinematics for functional retraining.7 Typically, after 3 months of postsurgical management, most patients experience an improvement in self-reported ankle function and return to activities of daily life.8 However, during the postoperative evaluation of CAI, physicians and clinical researchers mainly focus on mechanical insufficiencies and relatively overlook residual functional insufficiencies due to the difficulty of obtaining objective sensorimotor measurements in the clinic.9 Because postsurgically residual functional insufficiencies are significant risk factors for failure to return to sport and even reinjury after the torn ligaments are restabilized, it requires greater attention from both surgeons and patients to achieve better clinical outcomes.10

In the last half-century, numerous studies on CAI have explored its functional deficits.1 Impaired proprioception was the first proposed sensorimotor factor among the functional insufficiencies, which is provided by afferent signals from the joint to allow the individual to perceive the “position/movement” of the body and plays a vital role in maintaining joint stability.11,12 In the 1960s, Freeman et al. innovatively indicated that the proprioceptive nerve endings might be injured along with the torn ligament11, and subsequent theories have further suggested that ankle laxity, deafferentation, inflammation, and pain might altogether lead to disrupted proprioceptive input, contributing to functional insufficiencies.13 Proprioception-related evaluations have mainly included a specific evaluation via sensory-matching tests (e.g., the joint position reproduction [JPR] test) and the nonspecific evaluation through balance tests under static or dynamic single-leg stance.14,15 Nonspecific postural balance tests can be performed in both instrumental ways (e.g., center of pressure (CoP) sway in the force plate, stability index in the Biodex system, reach distance in the Star Excursion Balance Test [SEBT]) and noninstrumental ways (e.g., Romberg test measuring the duration of single-leg stance with eyes closed).14,15 Although nonspecific balance outcomes might also be influenced by several factors besides proprioception, such as muscle strength and range of motion, impaired proprioception remains the main contributing factor in CAI.16,17

Previous reviews have fully presented that patients with CAI would have worse outcomes in both specific proprioception and nonspecific balance tests.1,18, 19, 20 After surgical restabilization, logical supposition suggested that the retensed ligament might restore the normal proprioceptive signals for the receptors as well as restore the functional deficits.21 In addition, the debridement of inflammatory tissues might also theoretically benefit proprioception by reducing regional pain and deafferentation.22,23 However, existing evidence on the postsurgical recovery of proprioception in CAI is conflicting and has not been summarized.24, 25, 26 As a result, there is a need to perform a systematic review to determine whether proprioception-related deficits are restored after surgical restabilization and the corresponding postsurgical care for CAI. In presenting a comprehensive review on this topic, we planned to include both of the aforementioned specific and nonspecific measurements of proprioception as our outcomes of interest.

Thus, in this study, we aimed to determine whether the application of surgical restabilization and postsurgical management significantly affects proprioception-related outcomes of injured ankles in patients with CAI. We hypothesized that the proprioception of injured ankles might be improved but cannot be fully restored after existing surgical treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses in Exercise, Rehabilitation, Sport medicine and SporTs science guidance.27 We prospectively registered the protocol in the International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO; ID No. **).

2.2. Search strategy

We systematically searched seven electronic databases (Web of Science, CINAHL, Embase, PubMed, Scopus, SPORTDiscus, and Cochrane Library) with the time period set from inception to Oct 13, 2023. We followed the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study type (PICOS) suggestion to define our search strategy, which was mixed with four grouped keywords that were connected by “AND,” and the included terms within each grouped keyword were connected with “OR,” including ankle-related and injury-related terms as Population, surgery-related terms as Intervention, and proprioception-related terms as Outcome:

-

(1)

Ankle-related terms: (ankle* OR “lateral ligament” OR “lateral ligaments” OR “Anterior Talofibular Ligament” OR “Anterior Talofibular Ligaments” OR “ATFL” OR “Calcaneofibular Ligament” OR “Calcaneofibular Ligaments” OR “CFL”)

-

(2)

Injury-related terms: (instabilit* OR unstable OR strain* OR sprain* OR rupture* OR tear*)

-

(3)

Surgery-related terms: (therap* OR threat* OR manage* OR surg* OR operat* OR repair* reconstruct* OR stabiliz* OR stabilis* OR proce*)

-

(4)

Proprioception-related terms: (propriocep* OR percept* OR sens* OR feedback* OR match* OR reproduct* OR postur* OR stabil* OR balance*)

We did not restrict Comparison or Study type in the searches. Detailed search strategies for each database are provided in Supplementary Appendix A.

Two authors (** and **) independently selected the articles. During article screening based on title and abstract, if an article was included by either reviewer, its full text was assessed for eligibility, whereas for articles included based on full text, if disagreements were not resolved through discussion, a third reviewer (**) was consulted. We used the following inclusion criteria: peer-reviewed studies written in English, studies that included postsurgical patients of unilateral lateral ligament restabilization for CAI, and studies that measured specific proprioception or nonspecific balance outcomes (static or dynamic single-leg stance) of the injured ankle.14 The study also measured the outcomes of the presurgical state, uninjured contralateral side, or uninjured healthy controls for comparison (control). We also performed a manual search of the reference lists of the included studies. If full text was not available, the corresponding authors were contacted.

2.3. Data extraction

Two authors (** and **) independently reviewed the studies to extract the following information: demographic data and sample size of participants, study design, description of the surgery and postsurgical management (instruction/rehabilitation), duration of follow-up, clinical outcomes, and methodology and scores of the proprioceptive outcomes. Because of the heterogeneity of the proprioceptive outcomes, the priority of the outcome data extraction was based on the sequence decided upon by an experienced orthopedist and kinesiologist. For the specific proprioception test (e.g., the JPR test), the ones in inversion and with a larger target angle were included because the joint proprioceptive receptors in the injured lateral ankle complex were mainly stimulated at the extremes of joint motions.14,28 For the nonspecific balance test, the CoP velocity/length measured by force plate, overall stability index measured by the Biodex Stability System, and posterior–medial reach distance measured by SEBT were extracted due to their popularity and sensitivity in detecting static or dynamic balance deficits in CAI.18,20,29, 30, 31 The authors were contacted when numerical data were unclear or not reported.

2.4. Quality assessment

All authors discussed the standard of each item before issuing a formal rating. Two authors (** and **) rated the included studies independently, and the third reviewer (**) was consulted for disagreements. We used the modified version of the Downs and Black checklist to assess the quality of studies, with the highest score of the checklist being 16 and thresholds for low, moderate, and high quality set as <60 % (≤9), 60%–74 % (10–11), and >75 % (≥12), respectively.32,33 The standardized tool recommended by the Non-Randomized Studies Group of the Cochrane Collaboration was applied to evaluate the risk of bias, which included biases caused by performance, detection, attrition, selection, and confoundings for details of tests and analysis.34 We also judged the level of evidence for each included study and our review from level 1 to 5 according to the Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence (http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653), with level 1 representing the highest quality and level 5 the lowest quality. The quality and level of evidence were not included as selection criteria, as we aimed to provide a comprehensive review of this topic.

To assess the variability of patients with CAI, we applied the recommendation of the International Ankle Consortium (IAC)2, which included the following: (1) sprain history (at least one significant ankle sprain resulting in pain, swelling, and at least 1 interrupted day of desired physical activity), (2) chronicity (that the significant sprain occurred at least 12 months ago), (c) no acute injury (does not have any ankle injury in the past 3 months), and (4) functional insufficiencies (has at least one of the classical CAI symptoms, namely, at least two episodes of “giving way” in the past 6 months, at least two sprains to the same ankle, and self-reported ankle instability confirmed by a validated questionnaire).2 To assess the variability of patients with CAI for surgical treatment, we applied the latest consensus reached by systematic review7, which included the following: (1) failed nonsurgical treatment (exhibits residual symptoms after 3–6 months of nonsurgical treatment), (2) mechanical insufficiencies (physical examination reveals tenderness around the lateral ligaments or a positive anterior drawer test or Talar tilt test), and (3) diagnostic ankle imaging (with the ligament injury confirmed by stress radiography or magnetic resonance imaging). Each criterion was scored as “fully reported and achieved the standard,” “partially reported or not achieved the standard,” or “not reported.”

2.5. Statistical analysis

Due to the heterogeneous treatment strategies, proprioception-related measurements, and postsurgical follow-up length, we did not perform a meta-analysis. Instead, we performed a qualitative analysis based on the proprioceptive difference between postsurgical ankles and presurgical ankles, ankles on the contralateral side, or healthy controls in each follow-up time point. The magnitude of the between-group difference was estimated by standardized mean differences (SMDs) of the Cohen's d effect size with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) calculated in Stata version 16 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The positive SMD represented higher scores in postsurgical ankles than in controls, and an absolute value of SMD ≥0.8 indicated large, 0.5–0.8 moderate, and 0.2–0.5 small effect sizes. Statistically significant between-group differences should have CIs of the SMD that do not cross zero.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection and characteristics

The systematic search retrieved 6759 potentially eligible studies with duplicates removed, and 13 studies were finally included in this review. Fig. 1 presents the selection steps and reasons for exclusion. We included a total of 347 patients with CAI in this study, and the mean age of the patients ranged from 25.5 to 40.8 years. Except for the study from Ayas et al., which enrolled healthy controls who were about 10 years younger than the patients26, the demographic information of the other studies were equalized between patients and healthy controls. To restabilize the loosened lateral ankle ligaments, anatomical ligament repair was applied in 10 studies (nine studies used the modified Broström procedure and one used the all-inside arthroscopic procedure), and three studies used reconstruction (one anatomical reconstruction using suture tape and two nonanatomical hemi-Castaing technique using half of the peroneus brevis tendon). The duration of postsurgical immobilization ranged from 2 to 4 weeks for repair and from 3 to 6 weeks for reconstruction. The entire duration of postsurgical instruction/rehabilitation ranged from 4 to 24 weeks, and eight studies included functional retraining of proprioception and balance. The follow-up length ranged from 3 months to nearly 5 years after operation, and patients in all studies achieved relief of ankle symptoms or dysfunction (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review selection process.

Table 1.

Detailed characteristics of studies included in the systematic review.

| First Author (year) | Study design (evidence level) | Participants with ankle instability | Healthy controls | Surgery strategy |

|

Postsurgical follow-up |

|

Proprioceptive Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. Halasi (2005) | Case-series (level 4) | 10 patients (aged 25.5 ± 7.3 years, 5 females) | 10 patients (aged 23.0 ± 5.8 years, 5 females) | MBP (open) |

|

Retrospectively ∼1.5 months |

|

Specific Proprioception: slope box in inversion |

| K. Iwao (2014) | Case-series/Case-control (level 4) | 10 patients [aged 27.6 (21–30) years,5 female]Para Run-on--> | 20 controls [aged 24.5 (19–29) years, 10 female] | MBP (open) |

|

Prospectively 3/6 months + 1 year |

Karlsson:

|

Specific Proprioception: active JPR in 30° inversion |

| A. L. Baray (2014) | Case-control (level 4) | 21 patients (aged 30.6 ± 12.4 years, 9 female) | – | Hemi-Castaing (open) |

|

Retrospectively ∼1.5 years |

Tegner: 8.7 ± 3.6 Karlsson: 84.2 ± 23.8 AOFAS: 88.1 ± 16.2 |

Specific Proprioception: passive JPR in 20° inversion Non-specific balance: static postural CoP length |

| H. Y. Li (2016) | Case-series (level 4) | 15 patients (aged 29 (18–60) years, 4 female) | – | arthroscopic debridement + MBP (open) |

|

Prospectively 6months |

AOFAS:

|

Non-specific balance: static postural CoP length (with/without vision) |

| A. L. Baray (2016) | Case-control (level 4) | 24 patients (aged 31.8 ± 13.1 years, 12 female) | 15 controls (aged 23.8 ± 8.1 years, 6 female) | Hemi-Castaing (open) |

|

Retrospectively ∼2 years |

Tegner: 8 (6–10) Karlsson: 87.3 ± 23.8 AOFAS: 89.1 ± 16.2 |

Specific Proprioception: passive JPR in 20° inversion Non-specific balance: static postural CoP length |

| B. K. Cho (2019) | Case-series (level 4) | 24 patients [aged 29.2 (18–39) years, 15 female] | – | arthroscopic debridement + suture-tape reconstruction (open) |

|

Prospectively 6 months/∼3 years |

CAIT:

|

Specific Proprioception: passive JPR in 20° inversion Non-specific balance: modified romberg test |

| J. H. Lee (2020) | Non-randomized controlled cohort (level 3) | 30 patients (aged 28.1 ± 8.2 years, 10 female) | – | MBP (?) |

|

Retrospectively 3 months |

|

Non-specific balance: static/dynamic postural biodex stability system OSI |

| B. K. Cho (2022) | Case-series (level 4) | 46 patients [aged 31.6 ± 6.2 years, 19 female] | – | MBP (?) |

|

Prospectively 3/6 months + 1 year |

FAOS:

|

Specific Proprioception: passive JPR in 20° inversion Non-specific balance: modified romberg test |

| Z. C. Hou (2022) | Randomized trial (level 2) | 36 Arthroscopic patients (aged 28.3 ± 5.4 years, 19 female) 34 Open patients (aged 28.6 ± 4.8 years, 17 females) |

– | arthroscopic debridement + MBP (open/arthroscopic) |

|

Prospectively 6 months + 1 year |

AOFAS:

|

Non-specific balance: static postural CoP length (without vision) |

| J. H. Lee (2022) | Case-control (level 4) | 40 patients (aged 27.3 ± 3.6 years, 15 female) | 35 controls (aged 24.8 ± 2.2 years, 14 female) | MBP (?) |

|

Retrospectively 3 months |

|

Non-specific balance: static/dynamic postural biodex stability system OSI |

| S. W. Kim (2022) | Case-series (level 4) | 64 patients [aged 30.3 (21–46) years, 41 female] | – | arthroscopic debridement + MBP augmented with suture-tape (open) |

|

Prospectively 6 months + 1/∼5 years |

FAOS:

|

Non-specific balance: modified romberg test |

| I. H. Ayas (2023) | Case-control (level 4) | 25 patients (aged 39.82 ± 12.45 years, 14 females) | 25 patients (aged 28.16 ± 3.34 years, 9 females) | all-inside anatomic repair (arthroscopic) |

|

Retrospectively ∼3 years |

The anterior drawer test and varus stress test: negative. VAS-activity: 3.12 ± 2.83. AOFAS: 86.26 ± 13.92 |

Non-specific balance: (1) static postural biodex stability system OSI (2) dynamic postural Posterior-medial reach distance of SEBT |

| S. Cao (2023) | Case-control (level 4) | 8 patients (aged 40.8 ± 12.0 years, 4 females) | 8 patients (aged 37.6 ± 8.1 years, 4 females) | arthroscopic debridement + MBP (arthroscopic) |

|

Retrospectively 3 months |

AOFAS:

|

Non-specific balance: dynamic postural Posterior-medial reach distance of SEBT |

ADL, Activities of Daily Living; AOFAS, American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society; CAIT. Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool; COP: Center of pressure; FAAM, Foot and Ankle Ability Measure; FAOS, Foot and Ankle Outcome Score; JPR, Joint Position Reproduction; MBP, Modified Broström Procedure; NR, Not Reported; ROM, range of motion; SEBT, Star Excursion Balance Test.? In surgery strategy means open or arthroscopic surgery not reported.

3.2. Outcomes of quality and risk of bias assessments

The total quality scores ranged from 8 to 12 scores, indicating four low, four moderate, and five high quality studies. All studies clearly described their aims, patient characteristics and principal confounders (low performance bias), and main findings, and they used proper statistical tests for the main outcomes with random variability and a P value provided. The participation rates of all studies were higher than 80 % (low attrition bias). However, none of the studies stated that the healthy controls were recruited from the same population as the patients. Only two studies used blinded investigators when measuring the main outcomes (high detection bias), and none adjusted for confounding in the analyses. Supplementary Appendix B and C presents a full table of the quality and risk of bias assessments, respectively. According to the Oxford level of evidence, there were 11 case-control or case series studies with level 4 evidence, only one nonrandomized controlled cohort study of level 3 evidence, and one randomized trial of level 4 evidence (Table 1). Because we did not include groups with wait-and-see or conservative treatment in this study, the reviewed outcome of treatment benefits could only be judged as level 4 evidence.

With regard to standardized criteria for patients with CAI, although all studies mentioned the patients’ history of ankle sprains, only two mentioned the severity of the sprain as resulting in pain, swelling, or interruption of physical activity for at least 1 day for that significant sprain. Only two studies reported a chronicity lasting longer than 12 months, and only one study excluded recent sprains (i.e., occurring in the past 3 months). When considering the symptoms, nine studies mentioned functional insufficiencies, whereas only five studies met the standard of the IAC. With regard to the criteria for surgical treatment, seven studies reported a criterion of 3–6 months of failed conservative treatment before surgery, and the ligament injuries were validated by physical examination in five studies and by diagnostic imaging in nine studies (Supplementary Appendix D).

3.3. Proprioception-related outcomes

3.3.1. Ligament repair

Three studies applied specific evaluation of proprioception for patients with ligament repair (Fig. 2). In 2005, Halasi et al. initially applied the slope box test (determining different slope angles) for patients with CAI before and at about 1.5 months after surgery.21 Although the postsurgical outcomes were similar to those of the uninjured contralateral side, improvements from the presurgical state were also limited (SMD = 0.41, 95 % CI −0.47 to 1.30).21 Iwao et al. applied the active JPR test and observed significantly less proprioceptive errors from 3 months to 1 year after surgery when compared with both the presurgical state (SMD ranging from −0.97 to −1.57) and healthy controls (SMD ranging from −0.97 to −0.71).25 However, after measuring the passive JPR test, Cho et al. indicated that their patients had residual proprioceptive errors after surgery when compared with the uninjured side (SMD ranging from 0.58 to 1.15).9

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of both specific proprioception and nonspecific balance between the postsurgical ankles (ligament repair) and the postsurgical ankles (row 1), uninjured contralateral side (row 2), and healthy controls (row 3). Results with 95 % confidence intervals that do not encompass the zero line indicate a statistically significant difference. JPR, joint position reproduction; mo, month; y, year; ?, not reported.

When considering the nonspecific balance test (Fig. 2), two studies used the force plate to measure the length or velocity of the CoP trajectory during the static single-leg test, but neither study indicated an improvement at 6 months or 1 year after surgery.23,35 When using the Biodex system, two studies found that the static mode revealed similar postural stability when compared with controls at 3 months after surgery.36,37 However, Ayas et al. found that, at about 3 years, the injured ankle had higher instability when compared with both the contralateral side (SMD = 0.76, 95 % CI 0.18 to 1.33) and healthy controls (SMD = 1.10, 95 % CI 0.50 to 1.70).24 When the dynamic model of the Biodex system was used, higher instability of the injured ankle was also reported by Lee et al. at 3 months when compared with healthy controls (SMD = 0.77, 95 % CI 0.30 to 1.25).36 When the patients were asked for further dynamic posterior–medial reaching in the single-leg stance, the distance reached was still shorter in patients when compared with healthy controls at about 3 years after surgery (SMD = −0.88, 95 % CI −1.46 to −0.30).24 Without using laboratory instruments, some studies found that a longer static single-leg stance time of the Romberg test could be achieved from 6 months to about 5 years after surgery9,38, but this time was still worse than that achieved on the contralateral side at 1 year (SMD ranging from −1.15 to −0.62).9

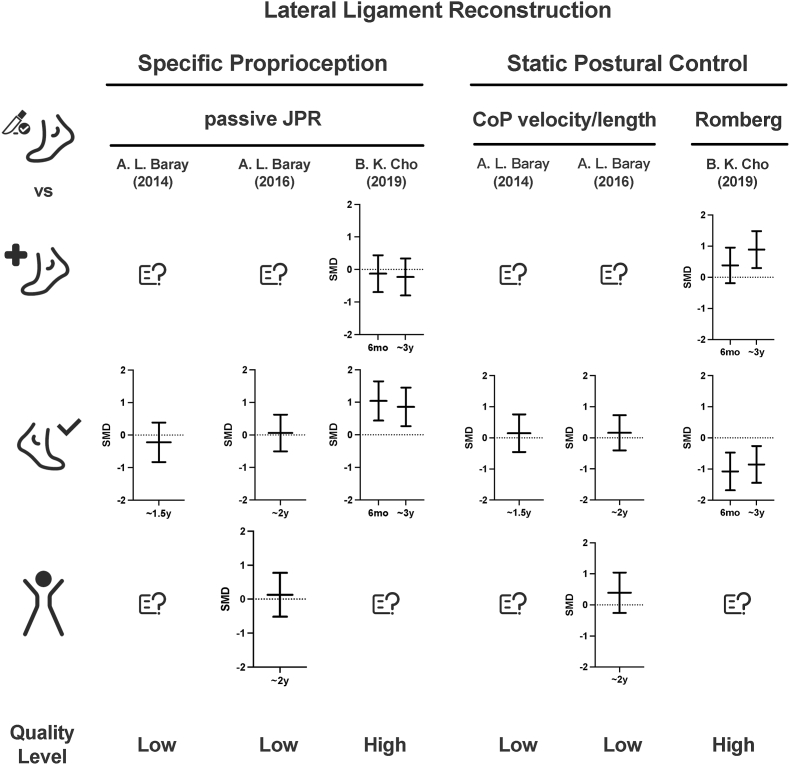

3.3.2. Ligament reconstruction

The two studies with nonanatomic hemi-Castaing and one study with anatomical suture tape reconstruction evaluated both specific proprioception evaluation and nonspecific static postural balance (Fig. 3). The studies conducted by Baray et al. suggested that the patients who underwent the nonanatomic hemi-Castaing procedure showed no significant proprioception deficits in passive JPR or balance deficits in CoP length at 1.5 or 2 years after surgery when compared with the uninjured contralateral side or healthy controls (SMD ranging from −0.22 to 0.39).2639 Cho et al. applied the suture tape for augmentation and followed the patients for about 3 years, and their results suggested that the proprioceptive outcomes were not fully recovered, shown as higher errors in passive JPR (SMD = 0.86, 95 % CI 0.27 to 1.45) and lower scores on the Romberg test (SMD = −0.85, 95 % CI −1.45 to −0.26) when compared with the contralateral side at their final follow-up. All of the extracted data and calculated SMD for outcomes are presented in Supplementary Appendix E.

Fig. 3.

Comparisons of both specific proprioception and nonspecific balance outcomes between the postsurgical ankles (ligament reconstruction) and the controls of the presurgical state (row 1), uninjured contralateral side (row 2), and healthy controls (row 3). Results with 95 % confidence intervals that do not encompass the zero line indicate a statistically significant difference. CoP, center of pressure; JPR, joint position reproduction; mo, month; y, year; ?, not reported.

4. Discussion

The main finding of this systematic review was that although the proprioception-related outcomes might be improved after surgical restabilization and postsurgical management when compared with the presurgical states, they were still insufficiently recovered when compared with the uninjured controls. When delving deeper into the studies that were examined, ranging from ligament repair to reconstruction, this consistent theme of incomplete recovery emerges, regardless of the type of surgical intervention. To the best of our knowledge, there are no similar reviews available in the literature. Proprioception deficits might present potential challenges in day-to-day functional capacities, a concern that both patients and surgeons must be acutely aware of. As a result, we believed that such findings can provide additional considerations of residual proprioception deficits and the other functional insufficiencies with respect to the safe return to sport and avoiding reinjury after surgical restabilization of CAI.

4.1. Considerations for surgical restabilization

Intact ligaments are unquestionably vital for maintaining ankle stability by both providing mechanical support and transforming body information through proprioceptors.4 The anatomic ligament repair technique is the most commonly used technique for CAI, in which the remnant ATFL and/or CFL are retensioned back to the bone using anchors and then augmentation is performed using surrounding tissue or artificial material.10 Previous reviews suggested that several mechanoreceptors have been observed in lateral ankle anatomical components, and thus, surgical restabilization using the remnant ligament might restore proprioception.12,25 With regard to the specific proprioception evaluation, Iwao et al. indicated that their patients had even better proprioception than healthy controls did; however, their positive outcomes might have been caused by both the treatment and the learning effect for repeated active activation of surrounding muscle–tendon mechanoreceptors in the patient group.14,25,40 However, in the study by Cho et al., although the proprioception of the passive angle matching that of biased ligamentous mechanoreceptors might be improved when compared with the presurgical state, postsurgical patients still had deficits as compared with uninjured controls.9 We speculated that during the chronicity of CAI, the mechanoreceptors in the remnant ligament might have degenerated, and thus, benefits provided by simply retensioning might be limited.41 In addition, surgical treatment itself could lead to joint trauma and corresponding functional deficits, thus influencing the functional recovery of CAI. This review observed only the phenomenon of alterations in proprioception after surgery, and more laboratory studies are needed to clarify whether surgical retensioning could lead to clinically meaningful proprioceptive input from the remaining lateral ankle ligaments.

With regard to nonspecific balance outcomes after repair, the static outcomes measured by quantitative CoP sways could not be significantly altered after the surgery.23,35 A previous study suggested that balance deficits in CAI resulted from proprioception deficits17, and the lack of evidence of balance recovery was consistent with the aforementioned residual proprioception deficits.9 In addition, although several studies reported similar outcomes in recovery between the injured and uninjured contralateral side, it should be noticed that the contralateral side of patients with unilateral injury was also impaired in terms of sensorimotor ability, and thus, between-limb equalization only might not be able to indicate full recovery.42 Although the significantly younger controls used in the study by Ayas et al. might require caution when interpreting the between-group comparisons, the study by Lee et al. also supported the residual balance deficits in returning to sports when compared with healthy controls.36 Furthermore, although it was hypothesized that arthroscopic surgery might benefit patients by reducing iatrogenic injuries to the joint capsule and skin when compared with open surgery, the comparison conducted by Hou et al. indicated no significant superiority of minimally invasive surgery on proprioceptive outcomes.35 Until now, no solid conclusion could be drawn that patients with CAI who have undergone ligament repair could obtain sufficient restoration of proprioception and balance.

Ligament reconstruction was required mainly for patients with absorbed remnants (as repair is not possible) and was divided into two main categories: nonanatomic and anatomic.7 Nonanatomic ligamentoplasty was supposed to break the normal environment of the ankle and then disrupt ankle kinematics7, but the pair of studies from Baray et al. indicated that the hemi-Castaing technique did not seem to induce proprioceptive impairment.3926 However, we still cannot explain this simply as the treatment effect of nonanatomic reconstruction, because targeted proprioceptive postoperative rehabilitation could also benefit patients, and the outcomes from a single center might make the evidence unstable.26,39 Anatomic reconstruction better restores the previous mechanical properties of the ankle, but the only study on reconstruction using artificial suture tape indicated insufficient recovery of proprioception43, and we could find no proprioception-related evidence of anatomic reconstruction using auto-/allograft tendon grafts. Notably, dynamic–static tests were not included in the studies with ligament reconstruction, which might hint at the conservative postsurgical evaluation strategy for ligament reconstruction due to the worse presurgical outcomes. Nevertheless, the authors suggested there is still a need for proprioception-oriented evaluation and rehabilitation after ankle ligament reconstruction.26,39,43

4.2. Considerations for postsurgical management

Proper postsurgical management requires special attention equal to that of the surgery itself for a successful outcome during the perioperative period. Typically, the skin wound would be recovered at about 2 weeks postoperatively, and regeneration of ligaments or graft might also require 1 month to avoid early re-rupture or loosening of the restabilized ligaments.7,44 Most of the included studies in this review followed this classical view of immobilization strategies, and no significant variations in proprioceptive recovery were observed between the studies with 2–6 weeks of immobilization. However, there is also evidence that joint immobilization as short as 48 h could lead to deconditioning of neuromuscular functions, and thus, early movement and weight bearing might reduce the deleterious effect of disuse.7,44 A recent guideline further suggested that partial weight bearing with a brace should be encouraged from the second day after surgery for CAI patients who have undergone underwent anatomic lateral ligament repair or reconstruction to realize accelerated rehabilitation program.7 To determine how the length of postsurgical immobilization after lateral ankle restabilization influences the recovery of ankle proprioception deficits, more controlled studies are needed.

Restoring sensorimotor acuity through functional rehabilitation is vital for reducing proprioception deficits, symptoms of giving way, and the risk of reinjury in the management of CAI.44 Nowadays, orthopedic surgeons have become much more active with their postsurgical rehabilitation programs, which not only reduce complications in the intraoperative period (e.g., thromboembolic events) but also provide faster functional recovery and meet the increasing need of returning to play and sports after surgical treatment.10 Several outcomes should be considered when designing the rehabilitation protocol, including the strength of the initial restabilization, ligaments or tendon grafts healing to bone, full preservation of range of motion, and prevention of reinjury by sufficiently recovering sensorimotor acuity.44 However, there is evidence that even for conservatively treated patients with CAI, proprioceptive improvement after traditional exercise therapy could be limited.45,46 After mechanical stability was provided and the symptoms (e.g., pain and swelling) were relieved by surgery, proprioceptive outcomes were still unsatisfactory in our reviewed studies, despite the inclusion of proprioception or balance components in their description of the postsurgical rehabilitation protocol. Unfortunately, there remains a lack of evidence-based postsurgical rehabilitation protocols after lateral ankle ligament restabilization, and in this review, we could only observe the effects of the existing cases instead of providing detailed recommendations for a better postsurgical rehabilitation strategy of proprioception.39,44 Thus, there is still an urgent need for the development of more effective and validated postsurgical rehabilitation protocols for restoring the proprioceptive deficits for a safer return to play.

4.3. Limitations

This review has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, this study only put forward the problem of insufficient proprioception recovery after surgical treatment of CAI, but the existing evidence for its solution is lacking. We hope this review will highlight this problem for both researchers and clinicians, with the aim of facilitating future improvements in reducing residual functional insufficiencies after ligament restabilization. Second, this study was conducted on the basis that proprioception deficits were caused by the ankle injuries, but the low proprioception itself could also be the intrinsic reason for the initial ankle injury (i.e., the difference is already presented before the injury), which might make “proprioceptive recovery” hard to achieve.47 Third, the clinical relevance of the included heterogeneous proprioception-related outcomes were still conflicting because all of them could not reflect the performance of the proprioceptive system in real sports situations.14 Fourth, ankle laxity did not appear to be observed consistently in patients with CAI, and few patients required surgical treatment2, which might limit the applicable population of our results. Fifth, there was no control group who received the same rehabilitation training as the postsurgical patients but without surgical management to clearly demonstrate the effects of surgical restabilization. However, because most of the participants failed rehabilitation training before surgery, the design of such controls might be unethical. Sixth, as common problems among CAI research, the unsatisfactory heterogeneous CAI criteria of the included studies might reduce the reliability of our results. In addition, presurgical CAI patients were supposed to have intra-articular lesions (e.g., tibiofibular syndesmosis or medial ligament tears, synovitis, or osteochondral lesions), and although some of the studies set these lesions as exclusion criteria or treated them properly, others did not report them at all (especially for open surgery without arthroscopic debridement), which might also have led to evaluation bias. Seventh, it should also be mentioned that there is a potential risk of iatrogenic injury on the nerves or musculoskeletal structures not reported during the invasive procedures (e.g., improper surgical portal placement, inappropriate distraction, extensive debridement, and prolonged tourniquet or anesthesia use), which might lead to bias in our conclusion.10 Eighth, the limited studies on this topic made it hard for us to perform the quantitative meta-analysis, or other more detailed subgroup assessments, such as discerning between high and low-quality research. It remains our hope that with the publication of more related studies in the future, an enriched update to this review will be feasible. Last but not least, I addition to the proprioception-related outcomes, patients with CAI also indicated other sensorimotor deficits of residual functional insufficiencies, such as muscle weakness and delayed peroneal reflex.1,48 More comprehensive reviews on the residual functional insufficiencies after surgical restabilization are needed for multimodal treatments in CAI.

5. Conclusion

The existing evidence does not consistently support proprioceptive recovery after existing surgical restabilization and the corresponding postsurgical management of patients with CAI. More controlled studies are needed to provide evidence-based protocols to improve proprioceptive recovery after ankle ligament restabilization for CAI, such as rapid weight bearing and effective functional retraining.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed were extracted from the included studies and provided in Supplementary Appendix E.

Ethics approval and informed consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 81871823, 8207090113], and the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee [No. 22dz1204700]. There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Xiao'ao Xue, Le Yu, and Shanshan Zheng contribute equally to this study as co-first authors.

Yinghui Hua, Ru Wang, and Hongyun Li contribute equally to this study as co-senior authors.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmart.2023.11.005.

Abbreviations

- anterior talofibular ligament

(ATFL)

- calcaneofibular ligament

(CFL)

- chronic ankle instability

(CAI)

- confidence intervals

(CIs)

- center of pressure

(CoP)

- joint position reproduction

(JPR)

- Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study type

(PICOS)

- Star Excursion Balance Test

(SEBT)

- standardized mean differences

(SMDs)

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Hertel J., Corbett R.O. An updated model of chronic ankle instability. J Athl Train. 2019;54(6):572–588. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-344-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gribble P.A., Delahunt E., Bleakley C., et al. Selection criteria for patients with chronic ankle instability in controlled research: a position statement of the International Ankle Consortium. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(13):1014–1018. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doherty C., Bleakley C., Delahunt E., Holden S. Treatment and prevention of acute and recurrent ankle sprain: an overview of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(2):113–125. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubbard T.J., Hertel J. Mechanical contributions to chronic lateral ankle instability. Sports Med. 2006;36(3):263–277. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vuurberg G., Hoorntje A., Wink L.M., et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: update of an evidence-based clinical guideline. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(15):956. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosik K.B., McCann R.S., Terada M., Gribble P.A. Therapeutic interventions for improving self-reported function in patients with chronic ankle instability: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(2):105–112. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song Y., Li H., Sun C., et al. Clinical guidelines for the surgical management of chronic lateral ankle instability: a consensus reached by systematic review of the available data. Orthop J Sport Med. 2019;7(9) doi: 10.1177/2325967119873852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Review A.S., Li Y., Su T., Hu Y., Jiao C., Guo Q. 2021. Return to Sport after Anatomic Lateral Ankle Stabilization Surgery for Chronic Ankle Instability; pp. 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho B.K., Kim S.H., Woo K.J. A quantitative evaluation of the individual components contributing to the functional ankle instability in patients with modified Broström procedure. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2022;61(3):577–582. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2021.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bejarano-Pineda L., Amendola A. Foot and ankle surgery: common problems and solutions. Clin Sports Med. 2018;37(2):331–350. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman M.A., Dean M.R., Hanham I.W. The etiology and prevention of functional instability of the foot. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser B. 1965;47(4):678–685. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.47b4.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takebayashi T., Yamashita T., Minaki Y., Ishii S. Mechanosensitive afferent units in the lateral ligament of the ankle. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser B. 1997;79(3):490–493. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B3.7285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Needle A.R., Lepley A.S., Grooms D.R. Central nervous system adaptation after ligamentous injury: a summary of theories, evidence, and clinical interpretation. Sport Med. 2017;47(7):1271–1288. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0666-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Röijezon U., Clark N.C., Treleaven J. Proprioception in musculoskeletal rehabilitation: Part 1: basic science and principles of assessment and clinical interventions. Man Ther. 2015;20(3):368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark N.C., Röijezon U., Treleaven J. Proprioception in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Part 2: clinical assessment and intervention. Man Ther. 2015;20(3):378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabriner M.L., Houston M.N., Kirby J.L., Hoch M.C. Contributing factors to Star Excursion Balance Test performance in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Gait Posture. 2015;41(4):912–916. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ko K.R., Lee H., Lee W.Y., Sung K.S. Ankle strength is not strongly associated with postural stability in patients awaiting surgery for chronic lateral ankle instability. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):326–333. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-4960-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xue X, Wang Y, Xu X, et al. Postural control deficits during static single-leg stance in chronic ankle instability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sport Heal A Multidiscip Approach. March 2023:194173812311524.doi:10.1177/19417381231152490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Xue X., Ma T., Li Q., Song Y., Hua Y. Chronic ankle instability is associated with proprioception deficits: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sport Heal Sci. 2021;10(2):182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song K., Jang J., Nolte T., Wikstrom E.A. Dynamic reach deficits in those with chronic ankle instability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2022;53:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2021.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halasi T., Kynsburg Á., Tállay A., Berkes I. Changes in joint position sense after surgically treated chronic lateral ankle instability. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(11):818–824. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.016527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua Y. Editorial commentary: repair of lateral ankle ligament: is arthroscopic technique the next station? Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2018;34(8):2504–2505. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H.Y., Zheng J.J., Zhang J., Cai Y.H., Hua Y.H., Chen S.Y. The improvement of postural control in patients with mechanical ankle instability after lateral ankle ligaments reconstruction. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(4):1081–1085. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3660-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayas İ.H., Çiçeklidağ M., Dağlı B.Y., et al. Comparison of balance and function in the long term after all arthroscopic ATFL repair surgery. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s00402-023-04817-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwao K., Masataka D., Kohei F. Surgical reconstruction with the remnant ligament improves joint position sense as well as functional ankle instability: a 1-year follow-up study. Sci World J. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/523902. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed15&AN=600398724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baray A.L., Philippot R., Neri T., Farizon F., Edouard P. The Hemi-Castaing ligamentoplasty for chronic lateral ankle instability does not modify proprioceptive, muscular and posturographic parameters. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(4):1108–1115. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3793-3. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed17&AN=615161343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ardern C.L., Büttner F., Andrade R., et al. Implementing the 27 PRISMA 2020 Statement items for systematic reviews in the sport and exercise medicine, musculoskeletal rehabilitation and sports science fields: the PERSiST (implementing Prisma in Exercise, Rehabilitation, Sport medicine and SporTs sc. Br J Sports Med. 2023:175–195. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-103987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riemann B.L., Lephart S.M. The sensorimotor system, part I: the physiologic basis of functional joint stability. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):71–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nozu S., Takemura M., Sole G. Assessments of sensorimotor deficits used in randomized clinical trials with individuals with ankle sprains and chronic ankle instability: a scoping review. Pharm Manag PM R. 2021;13(8):901–914. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sierra-Guzmán R., Jiménez F., Abián-Vicén J. Predictors of chronic ankle instability: analysis of peroneal reaction time, dynamic balance and isokinetic strength. Clin Biomech. 2018;54(August 2017):28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gribble P.A., Hertel J., Plisky P. Using the star excursion balance test to assess dynamic postural-control deficits and outcomes in lower extremity injury: a literature and systematic review. J Athl Train. 2012;47(3):339–357. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.3.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Downs S.H., Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tayfur B., Charuphongsa C., Morrissey D., Miller S.C. Neuromuscular function of the knee joint following knee injuries: does it ever get back to normal? A systematic review with meta-analyses. Sports Med. 2021;51(2):321–338. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01386-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeves B.C., Deeks J.J.H.J. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Higgins J.P., Green S., editors. Wiley- Blackwell; Chichester. England: 2008. Including non- randomized studies; pp. 391–432. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou Z chen, Su T., Ao Y fang, et al. Arthroscopic modified Broström procedure achieves faster return to sports than open procedure for chronic ankle instability. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2022;30(10):3570–3578. doi: 10.1007/s00167-022-06961-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J.H., Jung H.W., Jang W.Y. Proprioception and neuromuscular control at return to sport after ankle surgery with the modified Broström procedure. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-04567-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee J.H., Lee S.H., Jung H.W., Jang W.Y. Modified Broström procedure in patients with chronic ankle instability is superior to conservative treatment in terms of muscle endurance and postural stability. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(1):93–99. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05582-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S.W., Cho B.K., Kang C., Choi S.M., Bang S.M. Anatomic anterior talofibular ligament repair augmented with suture-tape for chronic ankle instability with poor quality of remnant ligamentous tissue. J Orthop Surg. 2022;30(3) doi: 10.1177/10225536221141477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baray A.L., Philippot R., Farizon F., Boyer B., Edouard P. Assessment of joint position sense deficit, muscular impairment and postural disorder following hemi-Castaing ankle ligamentoplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(6):S271–S274. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witchalls J., Waddington G., Blanch P., Adams R. Ankle instability effects on joint position sense when stepping across the active movement extent discrimination apparatus. J Athl Train. 2012;47(6):627–634. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.6.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kosy J.D., Mandalia V.I. Anterior cruciate ligament mechanoreceptors and their potential importance in remnant-preserving reconstruction: a review of basic science and clinical findings. J Knee Surg. 2018;31(8):736–746. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1608941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wikstrom E.A., Naik S., Lodha N., Cauraugh J.H. Bilateral balance impairments after lateral ankle trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture. 2010;31(4):407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho B.K., Hong S.H., Jeon J.H. Effect of lateral ligament augmentation using suture-tape on functional ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40(4):447–456. doi: 10.1177/1071100718818554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearce C.J., Tourné Y., Zellers J., Terrier R., Toschi P., Silbernagel K.G. Rehabilitation after anatomical ankle ligament repair or reconstruction. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(4):1130–1139. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4051-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han J., Luan L., Adams R., et al. Can therapeutic exercises improve proprioception in chronic ankle instability? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103(11):2232–2244. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2022.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xue X., Tao W., Xu X., et al. Do exercise therapies restore the deficits of joint position sense in patients with chronic ankle instability? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sport Med Heal Sci. 2023;5(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.smhs.2023.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Witchalls J., Blanch P., Waddington G., Adams R. Intrinsic functional deficits associated with increased risk of ankle injuries: a Systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(7):515–523. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson C., Schabrun S., Romero R., Bialocerkowski A., van Dieen J., Marshall P. Factors contributing to chronic ankle instability: a systematic review and meta-analysis of systematic reviews. Sport Med. 2018;48(1):189–205. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed were extracted from the included studies and provided in Supplementary Appendix E.