Significance

Phages and viruses carrying the ZTGC-DNA (Z-DNA) genome are widely spread on earth. Exploring and evaluating how Z-DNA and Z-RNA function in various living systems will allow us to better understand Darwinian evolution and could help lay the groundwork for building artificial ZTGC genomes and life. Additionally, our investigations into non-Watson–Crick base pairing will be helpful for exploring ways to create a genetic firewall for Z-DNA life and guiding the rational design of improved nucleic acid-based therapies such as CRISPR genome editing by expanding the possible types of nucleotide modifications.

Keywords: genetic alphabet, RNA, CRISPR, Cas9, Cas12a

Abstract

Genomic DNA of the cyanophage S-2L virus is composed of 2-aminoadenine (Z), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C), forming the genetic alphabet ZTGC, which violates Watson–Crick base pairing rules. The Z-base has an extra amino group on the two position that allows the formation of a third hydrogen bond with thymine in DNA strands. Here, we explored and expanded applications of this non-Watson–Crick base pairing in protein expression and gene editing. Both ZTGC-DNA (Z-DNA) and ZUGC-RNA (Z-RNA) produced in vitro show detectable compatibility and can be decoded in mammalian cells, including Homo sapiens cells. Z-crRNA can guide CRISPR-effectors SpCas9 and LbCas12a to cleave specific DNA through non-Watson–Crick base pairing and boost cleavage activities compared to A-crRNA. Z-crRNA can also allow for efficient gene and base editing in human cells. Together, our results help pave the way for potential strategies for optimizing DNA or RNA payloads for gene editing therapeutics and give insights to understanding the natural Z-DNA genome.

Standard ATGC-DNA (A-DNA) and AUGC-RNA (A-RNA) are composed of four standard nucleotides, each with a different nucleobase: adenine (A), thymine (T)/uridine (U), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). These nucleobases form the genetic alphabet, ATGC, which make up the base pairs that follow Watson–Crick base-pairing rules, which are conserved across almost all domains of life. Why nature has evolved to primarily use these two base pair combinations remains one of the greatest mysteries in science. Researchers have described the distribution and evolution of non-conventional nucleobases, such as the Z-base, in biological systems (1–5). The Z-base, also known as 2-aminoadenine, was first discovered in the S-2L cyanophage genome, forming the ZTGC genetic alphabet that violates conventional Watson–Crick base pairing rules (1, 6). Phages and viruses carrying the ZTGC-DNA (Z-DNA) genome are widely spread on earth (2). The natural synthetic pathway of the Z-base and Z-DNA polymerases have been identified (3–5, 7, 8). These findings encourage the use of synthetic biology approaches to develop and manufacture phages or viruses with artificially designed Z-DNA genomes.

Compared to the standard A-base, the Z-base has an extra amino group on the two position that allows it to form a third hydrogen bond with a T-base in strands of DNA (9). When a Z–T pair is introduced in synthetic oligonucleotides, the extra hydrogen bond enhances the thermal stability, sequence specificity, and Type II restriction endonuclease (RE) resistance properties (2, 10, 11). Furthermore, in vitro tube assays have shown that Z-bases can be accepted as potential substrates for several standard RNA and DNA polymerases (12–14). In the field of disease therapeutics, Z-DNA is predicted to have many advantages over A-DNA, including with nucleic acid drugs (5). In recent years, nucleic acid therapies have achieved significant success. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) can deliver DNA or RNA payloads synthesized by chemical or in vitro transcription (IVT) to achieve in vitro and in vivo gene regulation or editing (15). Replacing certain standard nucleotides with modified nucleotides can improve the performance and efficacy of nucleic acid cargoes (16, 17). However, it is considered that these processes all depend on Watson–Crick pairing for binding and targeting. The discovery of the Z-base synthesis pathway further enriches the biodiversity of natural bases. Exploring and evaluating the compatibility of the Z-base in complex biological systems can help us learn about non-Watson–Crick pairing principles present in viruses, develop more potential applications for the ZTGC alphabet, and further contribute to the optimization of nucleic acid drugs. However, many questions regarding the functionality of Z-DNA or ZUGC-RNA(Z-RNA) have not yet been explored. Currently, it is not known whether Z-DNA or Z-RNA constructs are compatible with most of the cellular machinery and enzymes (2, 18).

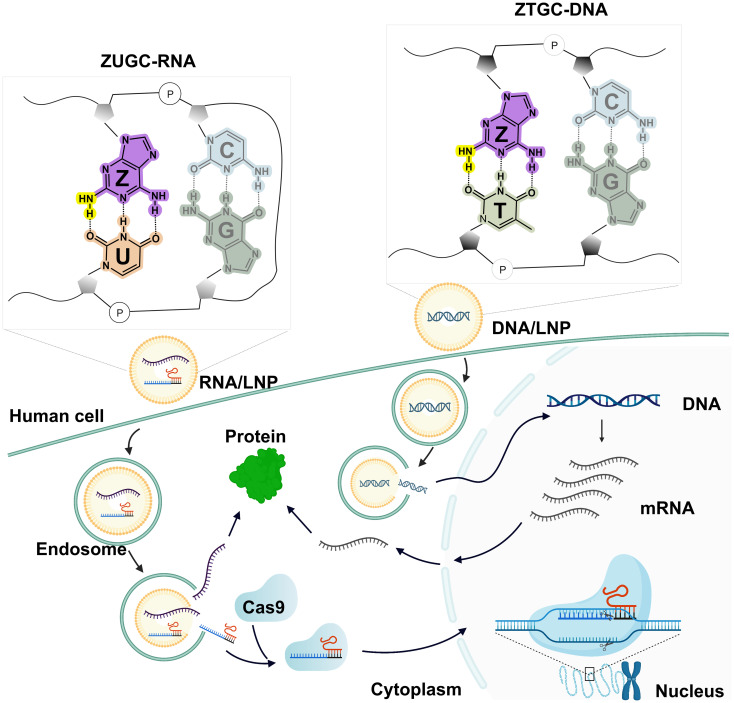

In this research (Fig. 1), we demonstrate that Z-DNA and Z-RNA are compatible in various living systems, including bacteria, yeast, and mammalian cells. Moreover, RNA-guided endonucleases including Cas9 and Cas12a could utilize Z-RNA through non-Watson–Crick base pairing processes to mediate efficient DNA cleavage and achieve precise gene editing in mammalian cells.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of this research. The top left frame shows Z–U and G–C base pairs in RNA written by the ZUGC alphabet. The top right frame shows Z–T and G–C base pairs in DNA written by the ZTGC alphabet. LNP, lipid nanoparticle. ZTGC-DNA base pairs. Hydrogen bonds are marked by dotted lines. The additional amino group is highlighted in yellow.

Results

Z–T Pairing Could Reduce the Melting Temperature and Enhance Resistance to Type II REs.

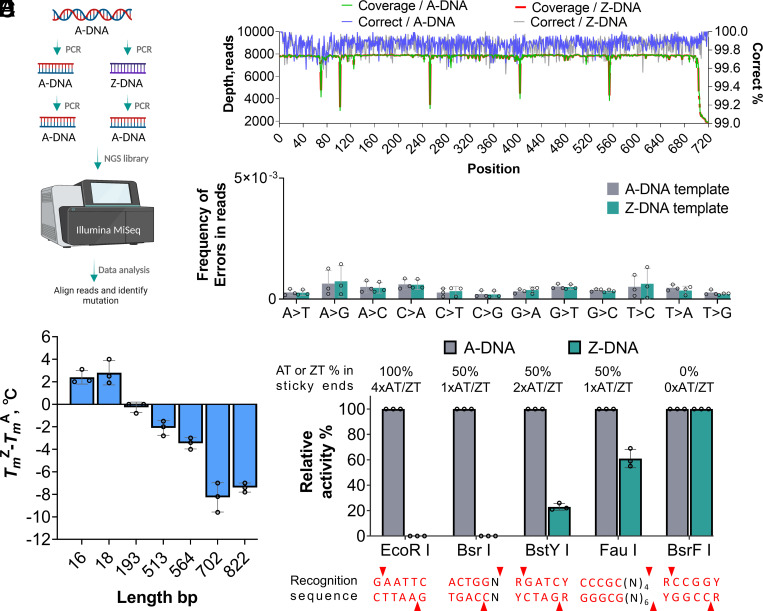

We first screened the ability of different DNA polymerases to prepare Z-DNA via in vitro reactions. Both A-family DNA polymerases, including Taq DNA polymerase from Thermus aquaticus YT-1, and B-family DNA polymerases, including Pfu polymerase from Pyrococcus furiosus, are able to incorporate modified nucleotides into DNA strands (19). We designed an artificial DNA template (DNA1) 720 base pairs (bp) long and with 54.4% AT content (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). We then compared the PCR amplification efficiency of Taq and Pfu on control and Z-substituted DNA1 templates. In this experiment, only Taq succeeded in amplification when dATP was completely replaced with dZTP for PCR. These results indicate that the Taq polymerase is more flexible than Pfu for dZTP incorporation. We then evaluated the yield of PCR amplification using 11 templates (SI Appendix, Table S1). Compared with standard reactions, Z-substitutions achieved 60-100% relative yield of the intended band (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). We then conducted an analysis of the impact of GC% within the PCR amplicon on the PCR yield. As illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C, we observed that an increase in GC% resulted in an increased PCR yield, although some outliers were also noted. Next, we evaluated whether Z-substitutions in the DNA1 template would lead to more mutations than adenine during PCR amplification. Of note, 720-bp PCR amplicons were amplified from A-DNA or Z-DNA templates and sequenced using an Illumina next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform (Fig. 2A) (20, 21). We obtained 1,803 to 7,697 reads for each position of all PCR samples. Sequenced bases were compared to the reference to identify substitution errors. The average percentage of correct reads for each position ranged from 99.82 to 99.84% (Fig. 2B). Then, we analyzed 12 types of base mutations, and results indicated no significant differences between the error rates of PCR products from A-DNA and Z-DNA (Fig. 2C). The further summarization of base mutation errors maintained that there were no significant differences observed between the two templates (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). These results indicate that the non-Watson–Crick Z–T pair did not cause negative impacts on the accuracy of in vitro replication of the DNA1 template.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of A-DNA and Z-DNA properties. (A) Schematic strategy for NGS analysis of DNA amplicons. The artificial DNA1 sequence was used in this investigation. (B) Depth of coverage and the percentage of correct reads at each base pair are summarized. (C) Frequency of errors types in reads from (B). (D) Melting temperature analysis of A-DNA and Z-DNA. (E) The relative activity of different REs on A-DNA and Z-DNA. Relative cleavage activity in each group was normalized to that of the A-DNA [relative activity (%) = 100]. Data are presented as mean values for three replicates. The reaction was carried out according to the instructions of BsrFI, FauI, BstYI, BsrI, and EcoRI. For each reaction, 100 ng PCR products were used. Top, content or amount of AT or ZT in the sticky end of each cleave site. Bottom, Recognition sequences are labeled in red. Cleavage sites are highlighted by red triangles. Error bars represent mean values ± SD, n = 3.

One physical property of DNA, melting temperature (Tm), represents the thermodynamic stability of a DNA double helix (22). Compared with the canonical A–T pairing, the Z–T pair possesses an extra hydrogen bond making it more similar to a G–C pair in regard to its Tm and minor groove width (23, 24). Other works found that short oligonucleotides less than 160 bp exhibited increases in Tm when incorporated with Z-bases (9, 25–27). Because of this, we investigated the effect of Z-substitutions on the Tm of longer DNAs. We first designed two additional artificial templates, DNA2 with a length of 822 bp carrying 39% AT (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) and DNA3 with a length of 564 bp carrying 48% AT (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Then, we detected melting curves of the two natural and Z-substituted DNA templates. Surprisingly, the Tm of both templates decreased after Z-substitution. Specifically, the Tm of Z-DNA decreased 7.4 °C from 72.4 °C to 65 °C for DNA2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). This finding contrasts with results from short dsDNAs in previous works. This discrepancy might be because the longer Z-DNA strands used in our research fail to keep a stable natural structure due to the presence of too many Z–T base pairs (28). We further evaluated another set of five DNA sequences with various lengths (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 B–F). The results revealed an obvious correlation between the length and the Tm of the DNAs tested. For sequences with a length of less than 20 base pairs, the Tm of dsDNA with Z substitutions was 2.4 to 2.8 °C higher than that of the standard. Conversely, for sequences longer than 500 base pairs, Tm decreased 2.1 to 8.3 °C after Z substitution (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Further investigations into how the length or sequence of Z-DNA influences DNA thermal stability will be important.

Z-substituted DNA has demonstrated resistance to digestion by REs, including EcoRI, with recognition sites containing one or more As (5, 11). To investigate the resistance characteristics of Z-DNA to REs with recognition sites containing one or more As or Zs, we chose EcoRI and four other REs (BsrFI, BstYI, BsrI, and FauI) that were not tested in previous studies. BsrFI, BstYI, and EcoRI belong to the class of orthodox REs, while BsrI and FauI belong to IIS REs. These enzymes can generate sticky ends containing A-T pairs from 0 to 100%. Additionally, Type II orthodox REs and Type IIS REs can recognize asymmetric DNA sequences and cleave either inside or outside their recognition sequence, respectively (29). We observed that BsrFI showed 100% relative activity on DNA sticky ends without Z–T base pairs. Conversely, EcoRI and BsrI were completely blocked, and the relative activity of BstYI and FauI decreased by 77% and 39%, respectively, when Z–T base pairs were introduced into the sticky ends. This suggests that the presence of Z–T in both the recognition sequence and the sticky ends weakens the activity of standard REs on Z-DNA, with the latter having a greater impact (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Both the improved base pair stability with the extra H-bond and the formation change of the groove both contributed to RE resistance in Z-substituted DNA strands. We concluded that the introduction of Z-bases into DNA not only leads to significant changes in the physical properties of DNA but also further affects or even blocks the action of certain sequence-dependent enzyme systems. Interestingly, there are also some biological components that can be compatible with Z-DNA.

DNA Written by ZTGC Can Be Decoded to Specific Genetic Information in Mammalian Cells.

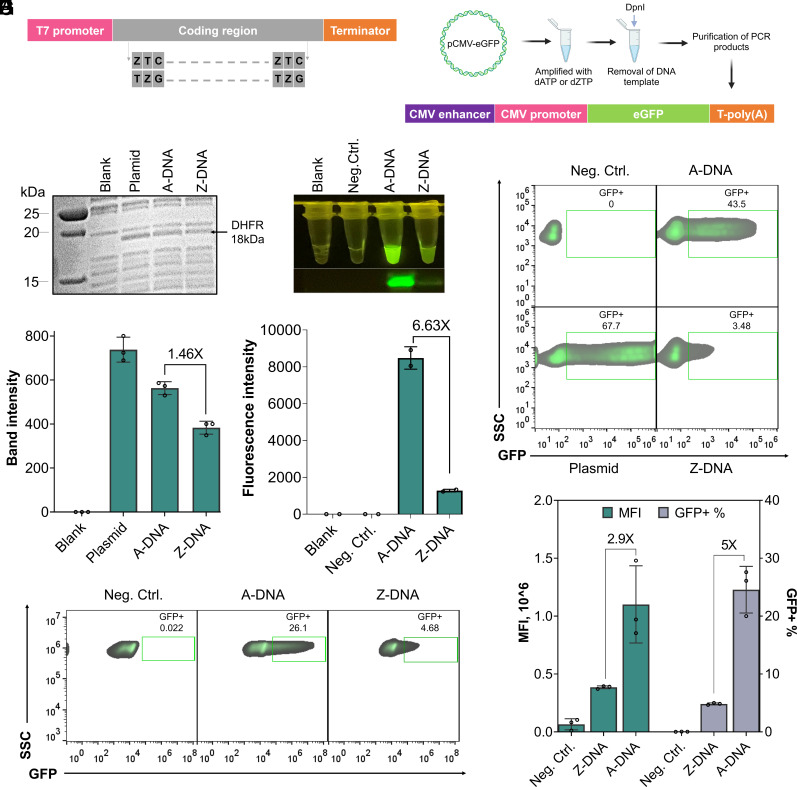

Standard living systems can decode ATGC-DNA and output RNA and proteins according to the central dogma of molecular biology (30). Though it was reported that T7 RNA polymerase and human RNA polymerase II activity could be strongly blocked up to 92% by introducing a single Z-substitution in the region between promoter and coding sequence of standard plasmid DNA (13), it remains unknown whether Z-DNA at the gene-scale or higher levels can still be transcribed and translated into proteins. We reasoned that Z-DNA may be compatible with decoding systems since the Tm of Z-DNA changes at various lengths and further evaluated whether different living systems can read and output genetic information from Z-DNA. First, we reprogrammed the coding region of genes with ZTGC nucleotides (Fig. 3A). Considering that the size of the coding region may affect expression efficiency, we chose the proteins dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) (SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2), which have molecular weights of 18 kDa and 27 kDa, respectively. The two coding sequences were optimized based on codon usage frequency in Escherichia coli and were placed under the control of a T7 promoter. The experiment was carried out in a cell-free system extracted from E. coli. Both DHFR and eGFP were successfully expressed using Z-DNA templates (Fig. 3 B–E), though the Z-DNA protein yield for DHFR and eGFP was significantly reduced when compared to A-DNA templates. Specifically, the yield dropped by 35.4% for DHFR and a substantial 84.9% for eGFP. These results indicate that the transcription and translation system of E. coli is compatible with Z-DNA coding sequences and outputs the correct genetic information. Different species are known to have different codon preferences. For example, Homo sapiens prefer GC-rich codons compared to E. coli (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) (31). Next, we investigated whether Z-DNA templates with codons optimized for eukaryotes (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 and Tables S3 and S4) could express proteins in prokaryotes. Neither Z-DNA nor standard DNA templates carrying coding sequences optimized for H. sapiens led to the eGFP expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). These results demonstrated that codon usage bias still exists for protein expression using Z-DNA templates of eGFP. Then, we replaced all A-bases located in the promoter, coding box, and terminator region of the DNA construct with Z-bases to test its compatibility in living systems. DNA constructs were assembled in the promoter–gene–terminator architecture. For single-cell eukaryotes Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a TEF1p promoter with 300-bp length and 71% AT content, a gene eGFP optimized for S. cerevisiae with 720-bp length and 54% AT content, and a CYC1t terminator with 39 bp length and 77% AT content were selected for cassette assembly (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A and B and Table S5) (32). Excitingly, fluorescent cells were detected in the S. cerevisiae BY4742 cell population transformed with the Z-DNA cassette (SI Appendix, Fig. S11B). Next, we tested whether the Z-DNA could be decoded in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells. Genetic element cytomegalovirus (CMV) enhancer/promoter with 508 bp length and 50% AT content and a terminator with 207 bp and 53% AT content were used to control an eGFP gene optimized for H. sapiens with 720 bp and 38% AT (Fig. 3F and SI Appendix, Table S6). An average of 3.64% GFP+ cells were detected in HEK293T cells transfected with the Z-DNA cassette for eGFP, which was 12.2-fold lower than transfection with A-DNA (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S12). To assess whether mammalian cells could decode longer Z-DNA cargo, we constructed another cassette containing a firefly luciferase (Fluc) gene with a total length of 2.5 kb. Luciferase activity was detected in HEK293T cells transfected with Z-DNA. However, the luciferase activity was reduced by 18.8-fold compared to A-DNA (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Next, we tested Z-DNA in HeLa human cervical cancer cell lines. Interestingly, HeLa cells showed a 2.6-fold increase in compatibility of eGFP compared to HEK293T cells (relative compatibility 20% for HeLa cells versus 7.6% for HEK293T cells, relative compatibility means the ratio of GFP+% with Z-DNA to A-DNA) (Fig. 2 H and I). Together, these results indicate that transcription and translation systems function with Z-substituted DNA in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms.

Fig. 3.

ZTGC-DNA can be decoded in various life systems. (A) Schematic of Z-substituting region in PCR products used in (B–E). Top, design of DNA construct; bottom, region written by ZTGC in Z-DNA. DHFR amplicons were amplified from a NEBExpress DHFR Control Plasmid template using G052/G053 primers. GFP amplicons were amplified from a pIDT-eGFP template using G063/G064 primers. (B) Analysis of in vitro protein expression samples of DHFR using different DNA templates on a gel. Reaction was carried out at 37 °C for 4 h. Note that 5 µL sample of each reaction was loaded for gel analysis. The graph represents one of three independent experiments. (C) Band intensities in (B) were analyzed by GelAnalyzer. (D) Top, Imaging fluorescence of GFP expression by in vitro protein expression in a cell-free system extracted from E. coli using different DNA templates. Bottom, In-gel fluorescence detection of eGFP protein. The graph represents one of two independent experiments. (E) Band intensities in (D) were analyzed by GelAnalyzer. (F) Schematic construct design of DNA template used for eGFP expression in the human cell. DNA was amplified by PCR from pCMV-GFP plasmid using G132/G133 primers. (G) Representative flow cytometry plots of HEK293T cells 48 h post-transfection. About 30,000 cells were used as input for flow cytometry. Top left, negative control; bottom left, transfection with pCMV-GFP plasmid; top right, transfection with A-DNA; bottom right, transfection with Z-DNA. Note that 200 ng DNA was used for each transfection. (H) Hela cells 48 h post-transfection were analyzed by flow cytometry and gated on GFP+ transfected cells. About 30,000 cells were used as input for flow cytometry. Left, negative control; center, transfection with A-DNA; right, transfection with Z-DNA. Note that 200 ng DNA was used for each transfection. The graph represents one of three independent experiments. (I) The graph summarizes the MFI and percent of GFP+ cells. Error bars represent mean values ± SD, n = 2 or 3.

Human Cells Showed High Compatibility with mRNA Written by ZUGC.

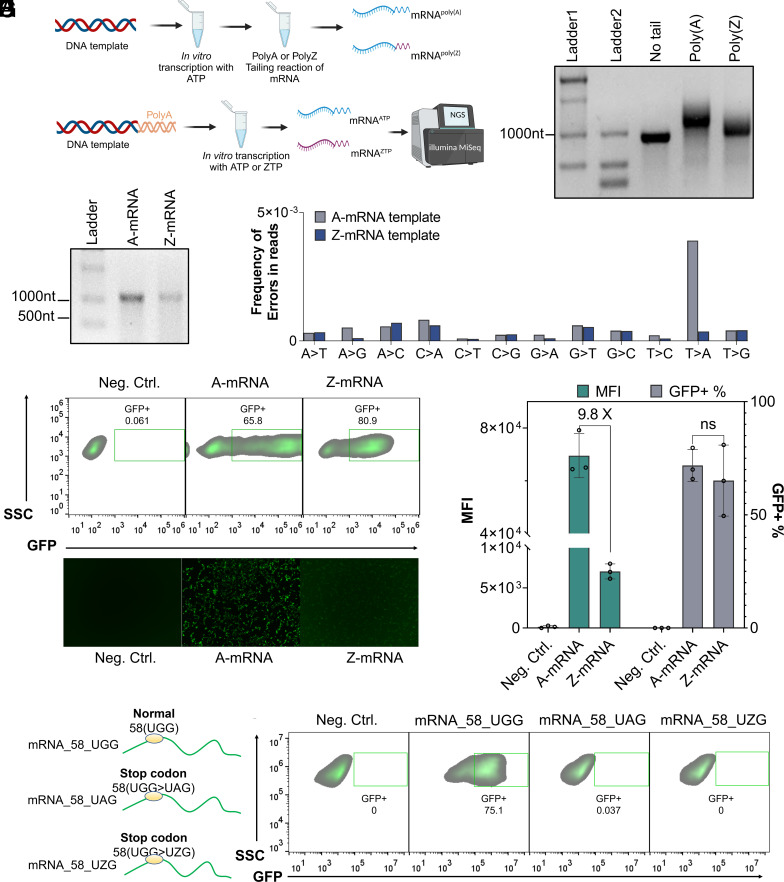

Decoding exogenous DNA in mammalian cells involves a complex process including DNA delivery to the cell’s nucleus, transcription, and translation. Alternatively, mRNA can be directly translated after entering the cytoplasm to complete the expression of the target protein. Indeed, the delivery of standard mRNA shows faster and stronger protein expression than standard DNA (15). From this, we reasoned that mammalian cells may have greater compatibility with ZUGC-written mRNA. We investigated this by first using IVT reactions to produce mRNA both with and without Z substitutions (Fig. 4A). We then explored whether ZTP could replace adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and execute biological functions in the form of a poly(Z) tail. In eukaryotes, poly(A) tails play a key role in enhancing mRNA stability and expression (33). Poly(A) polymerase from E. coli succeeded in tailing ZTP to normal mRNA of eGFP 875 nucleotides (nt) long to generate mRNA-poly(Z) products (Fig. 4B). This result implies that while ZTP-based tailing is achievable, the process is notably less efficient than tailing with ATP. In addition, 24 h after transfection, mRNA-poly(Z) showed 50% more GFP expression than mRNA with no tails (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). Then, ZUGC-mRNA transcripts were produced from a DNA template (SI Appendix, Table S4) carrying a GG start site of transcription using a T7 RNA polymerase reaction using either only ATP or ZTP (Fig. 4C). Negative impacts of Z-substitution on the accuracy of IVT were not observed from NGS analysis (Fig. 4D). Among these, the T-to-A mutations were reduced by 10-fold compared to the standard template. We speculated that the 2-amino substituent in adenosine led lower Z-A mismatch than A-A during the transcription process (SI Appendix, Fig. S15) (34). To test whether non-canonical mRNA could be translated in mammalian cells, we delivered Z-mRNA of eGFP to HEK293T cells in vitro. We observed that the cells transfected with Z-mRNA showed detectable GFP expression (Fig. 4 E and F). Notably, there was no statistical difference in the GFP positive fraction between Z-mRNA- and A-mRNA-transfected HEK293T cells. However, standard mRNA produced an MFI that was 9.13-fold higher than the Z-substituted mRNA. Interestingly, the Z-mRNA resulted in an average of 65.2% GFP+ cells, which was 19-fold higher than Z-DNA transfection (Fig. 4G). These data demonstrate that HEK293T cells have high compatibility with Z-mRNA encoding eGFP. Next, we explored whether Z-mRNA affects the preciseness of protein translation in mammalian cells. To do this, we mutated the 58_UGG codon encoding tryptophan (W) at position 58 of the reporter DNA template to 58_UAG, a stop codon. Then 58_UZG Z-mRNA was produced from this variant template (Fig. 4H). No GFP+ cells were detected in HEK293T cells transfected with 58_UZG-mRNA (Fig. 4I). This demonstrates that the UZG codon was properly read as a stop codon and not tryptophan in HEK293T cells. This is also consistent with high fidelity in vitro amplification and transcription. These results demonstrate that the ZUGC codon system can be compatible and function in mammalian cells, and that HEK293T cells have higher compatibility with Z-RNA than Z-DNA in eGFP expression.

Fig. 4.

ZUGC-mRNA enables specific protein expression in human cells. (A) Schematic strategy of mRNA investigation. Top, DNA template amplified from a pMRNA-eGFP plasmid using G126/G127 paired primers. RNA transcripts were produced by in vitro transcription (IVT) with standard nucleotides. Note that 5 µg RNA substrate was added into tailing reactions with either ATP or ZTP to synthesize mRNApoly(A) and mRNApoly(Z), respectively. Bottom, DNA template amplified from a pMRNA-GFP plasmid using a tail primer mix. This tailing DNA template was added into in vitro transcription reactions with ZTP or ATP to produce full length RNA transcripts. mRNA products were reverse transcribed into cDNA, which were used as templates for PCR. PCR amplicons were sequenced by an Illumina NGS platform. (B) Denaturing gel analysis of mRNA with no tail, a poly(A) tail, or a poly(Z) tail. For gel detection, 360 ng of each mRNA was loaded. ssRNA ladder was used. (C) Denaturing gel analysis of full-length transcript mRNA quality. IVT was performed with either ATP or ZTP. ssRNA ladder was used. Note that 200 ng of each mRNA was loaded. (D) Frequency of errors in reads from mRNA templates. (E) HEK293T cells 24 h post-transfection were analyzed by flow cytometry and gated on GFP+ transfected cells. Cells were transfected with 200 ng of AUGC-mRNA or ZUGC-mRNA. About 9,000 cells were used as input for flow cytometry. (F) Representative fluorescence images of HEK293T cells 24 h post-transfection with 200 ng A-mRNA or Z-mRNA. (G) The graph summarizes the MFI and percent of GFP+ cells. (H) Schematic figure of mRNAs carrying different stop codons. (I) Representative flow cytometry plots of HEK293T cells 24 h post-transfection with 58_UGG_mRNA, 58_UAG_mRNA, and 58_UZG_mRNA, respectively. Error bars represent mean values ± SD, n = 3.

ZUGC-crRNA Enhances In Vitro Cleavage Activity of Cas12a.

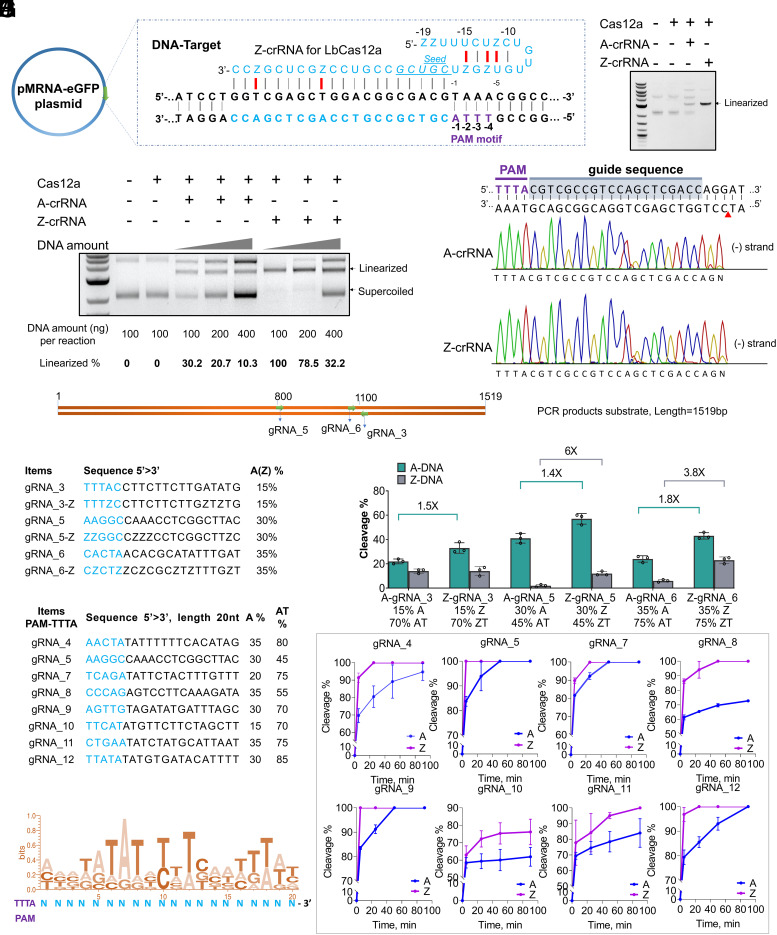

The high compatibility of ZUGC-mRNA in mammalian cells encouraged us to explore more Z-RNA-related applications. Gene editing with RNA-guided endonucleases has been widely used to advance fundamental research and for applications in animals, plants, and humans (35). We speculated that nucleases may have high compatibility with ZUGC-guide-RNA as they often rely on a small sized RNA to function. LbCas12a from Lachnospiraceae bacterium is a Type V CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) effector that prefers a T-rich 5′-TTTN Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) (36, 37). The single guide RNA (gRNA) used for LbCas12a consists only of a 39-nt CRISPR RNA (crRNA) with a single stem loop, making it notably simpler (Fig. 5A). We first tested the cleavage activity of Cas12a programed with ZUGC-crRNA (Z-crRNA) on plasmid DNA substrates. We selected a 20-nt guide sequence containing two A-bases to target a DNA site bearing a 5′-TTTA PAM (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Table S4). The corresponding crRNA was 39-nt in length, where A occupied a total of seven positions. We observed that Z-crRNA was able to efficiently induce Cas12a-mediated cleavage of supercoiled DNA (Fig. 5B). Notably, plasmid cleavage activity was improved up to 3.3-fold when using Z-crRNA compared to A-crRNA (Fig. 5C). We also mapped the Z-crRNA cleavage site using Sanger sequencing of the cleaved DNA ends and found that the cleavage site was same as when using A-crRNA (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

ZUGC-crRNA can guide Cas12a to cleave plasmids and PCR products. (A) Schematic map of plasmid used in (B–D). The frame representation of the Z-crRNA-DNA-targeting complex. Blue, targeted region and crRNA sequence; purple, PAM motif (5′-TTTA); red bonds, non-Watson–Crick base pairs in the pseudoknot structure of Cas12a Z-crRNA; italicized and underlined, seed region; gray bonds, Watson–Crick base pairs. (B) Cleavage assay of plasmid DNA mediated by A-crRNA and Z-crRNA. Reactions incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Note that 200 ng plasmid was used for each reaction. (C) Comparison of cleavage assay of supercoiled DNA. Reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. (D) Sanger sequencing of cleavage products from (C). The non-templated addition of an additional adenine, denoted as N, is an artifact of the polymerase used in sequencing. (E) Schematic locations of guide sequences used in (F) and (G) for this assay. DNA substrates were amplified from a pIDT-DNA4 plasmid using G030/G031 primers. (F) Characteristics of each guide sequence used for (G). Seed regions are in blue. (G) Both Z-crRNA and A-crRNA guide Cas12a to cleave Z-DNA and A-DNA PCR products. The graph shows cleavage % of reaction with each crRNA. Bottom, % A/Z and %AT/ZT in guide sequence. Note that 300 ng DNA was used for each reaction incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. (H) Characteristics of each guide sequence used for (I). Seed regions are in blue. (I) Quantified time-course data of cleavage by Cas12a loaded with A-crRNA or Z-crRNA. SspI linearized pIDT-DNA4 plasmid was used as DNA substrates. (J) Sequence logo for the top eight target sites in (H) and (I). Colored nucleotides match the most common nucleotide at that position. Analysis was done with WebLogo3.7.12. Error bars represent mean values ± SD, n = 3.

To investigate whether Cas12a could mediate cleavage of Z-DNA, PCR products with a ZT-content of 63.5% were amplified from a plasmid carrying an artificial sequence, DNA4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S16 and Table S7), and were used as substrates. Three Cas12a crRNAs containing a 20-nt guide sequence complimentary to target DNA sites with an A/Z content between 15% and 35% and AT/ZT content 45-75% were designed (Fig. 5 E and F). Both Z-crRNA and A-crRNA were able to guide Cas12a to the target and cleave PCR products with and without Z-substitutions. Notably, Z-crRNA showed 1.4-fold to 1.8-fold higher cleavage activity than A-crRNA on standard DNA, and up to sixfold more activity than A-crRNA on Z-DNA substrates (Fig. 5G and SI Appendix, Fig. S17) and showed activity on both 5′-TTTC and 5′-TTTG PAMs as well (SI Appendix, Fig. S18). Previous studies reported that crRNA with chemical modifications on terminal nucleotides could enhance serum stability (38, 39). The Z-substitution did not improve the resistance of crRNA to fetal bovine serum (SI Appendix, Fig. S19).

The first five nucleotides at the 5′-end of the guide sequence which are complimentary to the target DNA is known as the seed region for Cas12a (37, 40). As shown in Fig. 5 F and H, Cas12a efficiently mediated DNA cleavage with gRNAs carrying Z-substitutions in the seed region. Five A-bases are involved in the formation of the pseudoknot structure required for active Cas12a in the 5′-handle of standard crRNA where G(-6)–A(-2) and U(-15)–C(-11) form a stem structure via five Watson–Crick base pairs [G(-6):C(-11)–A(-2):U(-15)] (Fig. 5A) (36, 37). The ability of ZUGC-crRNA to function properly in Cas12a cleavage suggests that Z-base substitutions can also lead to the formation of the functional structure via non-Watson–Crick base pairing. Thus, our data demonstrate that Cas12a has a good tolerance for this non-canonical base pairing structure.

In the standard targeting processes, Cas12a-crRNA complexes with its complementary DNA target to form a DNA-RNA heteroduplex via 20 Watson–Crick base pairs prior to DNA cleavage. This heteroduplex is stabilized by H-bonds between base pairs (41, 42). Because Z-bases allow for a third hydrogen bond between Z and T, we hypothesized that more H-bonds between the DNA and crRNA may benefit the stability of the heteroduplex and lead to increased endonuclease cleavage. To evaluate this, the pIDT-DNA4 plasmid (SI Appendix, Table S7) linearized by SspI was selected for further investigation. Eight gRNAs with AT-contents ranging from 45 to 85% that target 20-nt DNA sites bearing a 5′-TTTA PAM were selected (Fig. 5H). Interestingly, time curves of a cleavage assay revealed that Z-crRNA showed 12 to 41% greater cleavage activity than A-crRNA across all tested crRNAs (Fig. 5I). Then, we conducted sequence logo analysis for the eight guide sequences to understand the sequence features. As shown in Fig. 5J, when T-bases appeared at position 5′-PAM-6, 8, 10, 18, 19-3′, Z-crRNA showed higher activity than A-crRNA. These results can be adapted for the optimal design of Z-crRNA to enhance the cleavage activity of Cas12a on another DNA sequence (SI Appendix, Fig. S20 and Table S8). To our knowledge, no research shows that chemically modified RNA bases could improve target affinity of crRNA-DNA to enhance CRISPR effector cleavage activity. As shown in Fig. 2D, when the DNA length is less than 20 bp, the replacement of A with Z bases increases the melting temperature. We reasoned that improved Cas12a cleavage efficiencies are due to improved binding affinity of crRNA:DNA. Previous studies reported that crRNA or sgRNA with chemical modifications show similar or lower in vitro cleavage activity compared to unmodified guides (43, 44). Here, we demonstrate the non-canonical base that could enhance Cas12a in vitro cleavage activity.

Together, these results show that Cas12a has good compatibility with both Z-DNA and Z-crRNA. This means that Z-crRNA could act as a potentially strategy for in vitro screening highly active guide RNAs for gene manipulation in somatic cells with LNP delivery (45).

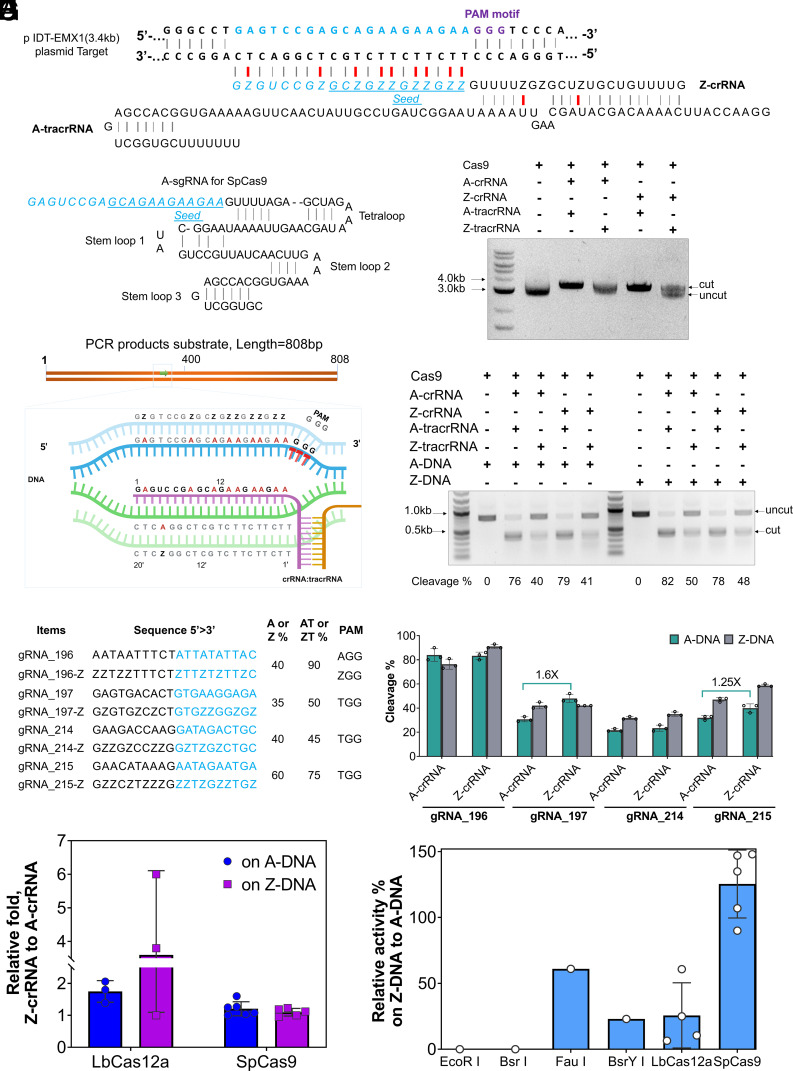

Z-crRNA:tracrRNA Duplex Enables Efficient Cas9-Catalyzed Non-Watson–Crick DNA Cleavage In Vitro.

As a Type II CRISPR/Cas system, SpCas9 is the most widely used tool in the field of gene editing therapies (35, 46). In contrast to Cas12a, the G-rich PAM 5′-NGG is favored by Cas9. Compared to the 39-nt crRNA for Cas12a, SpCas9 guide RNA is comprised of both a 42-nt crRNA and an 80-nt trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) (Fig. 6A). SpCas9 can also be programmed by a ~90-nt single guide RNA (sgRNA) to cleave a target sequence (Fig. 6B) (47). Overall, the gRNAs for SpCas9 are longer and more complex than LbCas12a. This led us to investigate whether Z-crRNA or Z-sgRNA could mediate SpCas9 cleavage of a DNA substrate. We first performed cleavage tests on supercoiled plasmid substrates with different dual-RNAs. Z-crRNA:Z-tracrRNA impeded Cas9 cleavage activity reducing it by ~50%, whereas Z-crRNA:A-tracrRNA led to similar Cas9 cleavage activity as the standard crRNA:tracrRNA (Fig. 6C). Though ZUGC-sgRNA produced by IVT showed the same quality as A-sgRNA, cleavage functionality was not observed for Cas9 loaded with Z-sgRNA (SI Appendix, Fig. S21). The Cas9-Z-sgRNA complexes also showed no detectable activity on other sites bearing a 5’-AGG PAM (SI Appendix, Fig. S22 A and B). A previous study showed that Z-sgRNA could strongly block the cleavage activity of SpCas9 on standard PCR products (14). Our results demonstrated that when employing dual gRNAs (crRNA:tracrRNA) rather than a single guide targeted to A-rich (~35 to 60%) regions, SpCas9 activity can be preserved when Z-crRNA is utilized, with a 50% retention rate when using Z-tracrRNA and a 100% retention rate when using A-tracrRNA. We speculated that pairing of the non-Watson–Crick form of Z–U failed in the formation of the active secondary structure of tracrRNA and sgRNA required for Cas9 (48). Next, we investigated the effect of Z-substituted guide RNAs on Cas9-mediated cleavage of Z-DNA or A-DNA PCR products. Our results indicated that Z-crRNA showed the same activity as standard crRNA when acting on Z-DNA or A-DNA. Like in the plasmid cleavage assay experiments, Z-tracrRNA led to detectable cleavage of PCR products with ~50% lower activity than A-tracRNA (Fig. 6 D and E). However, Z-sgRNAs still failed to cleave Z-DNA or A-DNA PCR products of the DNA5 template (SI Appendix, Figs. S22 C–E and S23). In vitro cleavage activities on AT-rich or ZT-rich DNA were also evaluated (Fig. 6F). We observed that Z-crRNA boosted cleavage activity on PCR products up to 60% more compared to A-crRNA (Fig. 6G and SI Appendix, Fig. S24). This similar improvement was also observed in the cleavage assay of linear plasmid DNA (SI Appendix, Fig. S25). These results indicate that SpCas9 is compatible with both Z-DNA and Z-RNA. Overall, SpCas9 shows higher relative activities than REs and Cas12a on Z-DNA (Fig. 6 H and I). We reasoned that the CRISPR-Cas9 system should be an efficient mechanism in nature to defend against phage or virus carrying the Z-DNA genome.

Fig. 6.

SpCas9 is guided by Z-crRNA to cleave A-DNA and Z-DNA. (A) Schematic of standard crRNA-tracrRNA of SpCas9 paired with target standard DNA. DNA and RNA nucleotides are shown in bold and light, respectively. Red bonds, non-Watson–Crick base pairs; gray bonds, Watson–Crick base pairs. (B) Schematic structure of A-sgRNA for SpCas9. (C) Cleavage assay of plasmid with the use of different crRNA and tracrRNA. Note that 170 ng plasmid pIDT-EMX1 was used for each reaction. Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. (D) Schematic locations of guide sequence used in (E) for this assay. DNA substrates were amplified from a pIDT-EMX1 plasmid using G030/G031 primers. The frame schema shows the comparison between protospacer positions in A-DNA and Z-DNA substrates. Blue, non-target strand in A-DNA; light blue, non-target strand in Z-DNA; green, target strand in A-DNA; light green, target strand in Z-DNA; purple, crRNA for Cas9; orange, tracrRNA; red, PAM motif (GGG). (E) PCR DNA cleavage assay of Cas9 with either A-crRNA or Z-crRNA. Note that 300 ng DNA substrate per reaction was used. Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. (F) Characteristics of each guide sequence used for (G). Seed regions are in blue. (G) Graph shows cleavage % of each crRNA. Error bars represent mean values ± SD, n = 3. (H) Relative activity of Z-crRNA to A-crRNA for Cas12a and Cas9. (I) Relative activity on ZTGC-DNA to ATGC-DNA. Values for EcoRI, BsrI, FauI, and BstY1 were summarized from Fig. 2E. Values for LbCas12a are summarized from Fig. 5G. Values for SpCas9 are summarized from Fig. 6 E and G. Values for LbCas12a and SpCas9 only refer to its cleavage ability with A-crRNA or A-sgRNA.

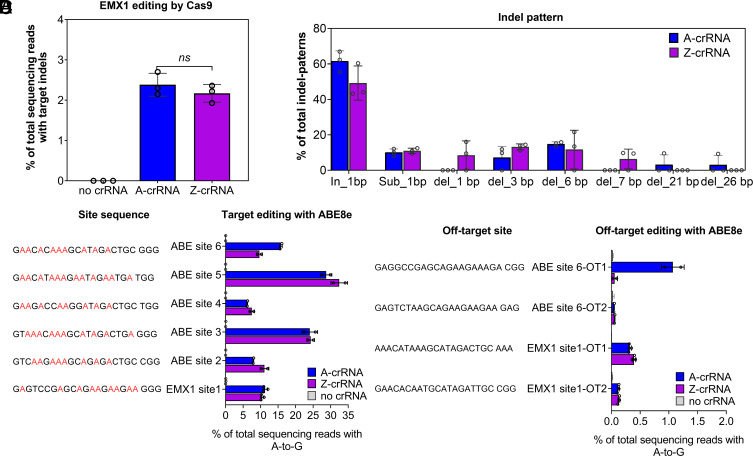

Z-crRNA Guides Cas9 and Base Editor Facilitate Genome Editing in Human Cells.

Considering SpCas9 is used much more widely than Cas12a, we further evaluated whether Z-crRNA could guide Cas9 to achieve specific gene editing in mammalian cells. As a proof of concept, we performed editing on endogenous genomic loci in human cells. First, we tried co-delivering SpCas9 mRNA and crRNA:tracrRNA to HeLa cells. Compared to A-crRNA, Z-crRNA exhibited similar levels of insertion-deletion (indel) efficiency (2.38% versus 2.17% on average) (Fig. 7A). This is also consistent with the relative activity of in vitro cleavage (Fig. 6E). Analyzing indel patterns after editing, deletions did not exceed 7 bp in Z-crRNA editing products, while A-crRNA editing induced larger deletions up to 26 bp (Fig. 7B). As we know, adenine base editor (ABE) is a more powerful and safe tool used for gene editing (49, 50). We then tested whether Z-crRNA could mediate targeted A-to-G nucleotide conversions using an ABE8e. To do this, ABE8e mRNA and crRNA:tracrRNA were co-delivered to HeLa cells. Six endogenous genomic sites reported in previous studies (51) were employed to evaluate the A-to-G editing efficiency. As shown in Fig. 7C, A-crRNA and Z-crRNA induced A-to-G edits with average frequencies of 15.6% (6.19 to 28.71%) and 15.9% (7.48 to 32.44%), respectively. We did not observe dramatic differences of editing distribution in the editing windows between Z-crRNA and A-crRNA (SI Appendix, Fig. S26). We then analyzed four potential off-target sites to evaluate Cas9-dependent off-target editing activities. We found that Z-crRNA and A-crRNA induced off-target editing 0.15% on average (0.05 to 0.39%) and 0.39% (0.02 to 1.07%) at the four sites (Fig. 7D), respectively. Z-crRNA did not induce more off-target editing than A-crRNA in our tested sites. However, a whole genome sequencing analysis is needed to conclude if Z-crRNA is better than A-crRNA. These data demonstrate that Z-crRNA could guide an ABE editor to efficiently generate A-to-G conversions in mammalian cells.

Fig. 7.

Gene editing with ZUGC-crRNA in human cells. (A) EMX1 gene editing efficiency with Cas9. Cells were transfected with a SpCas9 mRNA and its corresponding Z-crRNA:A-tracrRNA and A-crRNA:A-tracrRNA. (B) Indel-pattern % in total indel reads. (C) The A-to-G base editing efficiency of ABE8e with A-crRNA or Z-crRNA. All values are presented as mean ± SD, n = 2 or 3. (D) Cas9-dependent DNA off-target analysis of the indicated sites (EMX1 site 1, ABE site 6). HeLa cells were used for this test. Error bars represent mean values ± SD, n = 2 or 3.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrated that the biological function of ZTGC or ZUGC nucleic acids was explored at a different scale and for applications of protein expression and genome editing. Though Z-DNA shows changes in physical properties compared to A-DNA, it could be transcribed to mRNA and translated to functional proteins in standard prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. Additionally, mammalian cells could also translate Z-mRNA into proteins. Z-mRNA showed greater eGFP expression efficiency than Z-DNA in HEK293T cells. Additionally, both type II CRISPR-Cas9 and type V CRISPR-Cas12a endonucleases can be guided by Z-crRNA to efficiently cleave targeted Z-DNA substrates. Z-substitutions did not change the attribute of PAM, which can be efficiently scanned and recognized by SpCas9 and LbCas12a. RNA-guided endonucleases can also work well with non-Watson–Crick base pairing processes. SpCas9 and base editors carried detectable editing efficiencies with Z-crRNA. Together, our data demonstrate the ability for multiple protein complexes to scan and recognize non-Watson–Crick DNA carrying Z-bases.

Various modified nucleobases and the enzymes responsible for their processing have been discovered in recent years (52–54). Scientists have been pursuing these discoveries to expand the genetic alphabet to have a diverse set of nucleobases for the creation of synthetic organisms (55–57). In the last few decades, more than 20 chemical modifications have been detected in eukaryotic mRNAs (58), but most of them do not alter Watson–Crick pairing. Modified nucleobases can also play critical roles in improving the efficacy of gene therapies and vaccines, including the FDA-approved SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine (59–63). Further work into how Z-substituted mRNA may allow for alternative strategies for optimizing mRNA sequence for therapies is needed. Though Z-substituted DNA worked less efficiently than standard DNA in these typical life systems for promoting transcription and protein expression, our research helps give insights into understanding nucleosides and non-Watson–Crick DNA.

In order to expand the potential applications of gene editing, researchers have used protein engineering to alter the function of Cas nucleases, such as base or prime editors, or modified the PAM requirements of Cas9, such as in ultra-specific Cas9 and PAM-free Cas9 (64–66). Scientists have also proposed various strategies for optimizing guide RNAs to modulate Cas9/Cas12a specificity and activity, including those with unknown mechanisms. Some of these strategies include incorporating 2′-deoxynucleotides (67), chemically modified ribonucleotides into guide RNAs (43, 68), and removing or extending nucleotides from or to the 5′ end of guide RNAs (69–72). Due to its PAM sequence (5′-TTTN PAM), Cas12a allows gene editing in regions of the human genome rich with AT sequences, such as untranslated regions (UTRs) or introns. Of note, 34% of genes are in AT-rich isochores, which represents 62% of the genome (73, 74). However, Cas12a’s editing efficiency drastically decreased when the AT-content in the guide sequences increased (75, 76). For human genome editing, Cas9 guide sequences are most effective with a GC-content between 40% and 70%, and thus sgRNAs targeting 5′ and 3′ UTRs are highly ineffective (77, 78). It would be interesting to explore the contexts in which Z-crRNA is better than A-crRNA in the context of A(Z) percentage in the target sequence in the future work. Using Z-bases may be a potential strategy to improve activities of guide RNA through introducing non-Watson–Crick base pairing.

Our results show that Cas9 has similar or higher compatibility with non-Watson–Crick Z-DNA or Z-RNA, which enables Cas9 to be a potential research model used for exploring mechanism of interaction with Z-DNA or Z-RNA. Analyzing the crystal structure of these complexes will help us elucidate the mechanism by which residues interact with their target. An exploration of how Z-base substitution, at both the RNA and DNA levels, affects the functioning of RNA-guided endonucleases, will be helpful in understanding CRISPR evolution and developing improved gene editing tools. Importantly, the ability for RNA-guided endonucleases to cleave Z-DNA could allow for a strategy to create a biosafety control approach for future synthetic viruses carrying a Z-DNA genome (79, 80).

However, there are still lots of questions to be explored to better evaluate ZTGC. For example, it has yet to be determined why Z-DNA and Z-RNA cannot work well as A-DNA and A-RNA. In addition, because Z-DNA and Z-RNA could block many sequence-dependent and structure-dependent enzymes to play normal functions, the introduction of non-Watson–Crick base pairs may enable payloads more easily escape the immune response and achieve long-term circulation in vivo compared to the standard. Likewise, even though we know that 37 of 64 natural triplet-codons contain A-bases, we do not know whether Z-codons can be misread as other codons, although we did observe that UZG was not read as UGG in mammalian cells. More studies will be helpful for us to understand the functional characteristics of Z-DNA and Z-RNA, and to develop more applications of Z-nucleic acid.

In summary, our investigation helps us better understand the role and functionality of the Z nucleobase. Our insights will allow for the design of genetic elements for gene therapies.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

All reagents are from New England Biolabs, unless otherwise stated.

Construction of Plasmid.

pMRNA-eGFP and pMRNA-Fluc plasmids were constructed as described previously (81). All artificial DNA sequences were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, IDT. Plasmid pCMV-GFP was a gift from Dr. Connie Cepko (Department of Genetics and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) (82). Fragment of Fluc was amplified from pMRNA-Fluc and digested with AgeI/NotI followed by inserting in pCMV-GFP to generate the pCMV-Fluc plasmid.

DNA Amplification.

PCR products were generated by NEB Next High-Fidelity 2X PCR Master Mix (NEB, M0541), unless otherwise stated. All oligonucleotides were synthesized by IDT. Taq DNA Polymerase (NEB, M0320L) was used to make DNA fragments containing dATP or dZTP. For dZTP-DNA, 100 mM dATP was replaced with 100 mM dZTP (Trilink, N-2003-1). Primers were shown in SI Appendix, Table S10. Details are described in SI Appendix.

DNA Melting Curve Analysis.

SYBR™ Green I Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Fisher, S7563) was diluted 1:10,000 in 1X TE pH 8.5 to generate the reaction buffer. Then, 20 µL volume of reaction buffer contained 20 ng double stranded DNA (dsDNA) was added into a 96-well qPCR plate (Bio-Rad, HSP9631). The mixture was stained for 30 min at room temperature. A high-resolution melting curve program was carried out by thermocycling on a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The following program was used: 25 °C for 10 s, melting curve 20.0 °C to 95 °C for 5 s at 0.2 °C or 0.5°C increments.

In Vitro DNA Cleavage Assays.

First, 100 ng dATP or dZTP containing dsDNA PCR products that were purified using a Monarch Gel Purification Kit were subjected to restriction endonuclease digestion in a 20 µL reaction mixture following the manufacture’s protocol. The following restriction endonucleases were used: BsrFI (NEB, R0739S), BstYI (NEB, R0523S), BsrI (NEB, R0527S), FauI (NEB, R0651S), EcoRI (NEB, R0101S). Then, reactions were terminated by adding 5 µL Gel Loading Dye, Purple (6X) and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Imaging was carried out on a G:BOX system (Syngene). Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 nuclease (NEB, M0386) and Lachnospiraceae bacterium Cas12a nuclease (NEB, M0653S) were used for in vitro digestion of DNA. The in vitro reaction was performed as per the manufacture’s protocol. The final mixture was loaded into an agarose gel for analysis.

Illumina MiSeq Library Preparation, Sequencing, and Computational Methods for Determining Error Rates.

The DNA amplicon library was prepared following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Sequencing was carried out Illumina MiSeq instrument. Details are stated in SI Appendix.

Cell-Free Translation and Protein Assay.

In vitro translations were carried out using a PURExpress In Vitro Protein Synthesis Kit (NEB, E6800) following the manufacturer’s protocol. First, 250 ng plasmid DNA template or PCR products were used in a 25 µL reaction. The reaction was then incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. Finally, 5 µL of sample was loaded into 10 to 20% Tris-Glycine Mini Protein Gels (Invitrogen, XP10200BOX) to be examined and visualized by Coomassie staining.

E. coli and Yeast Transformation.

E. coli One Shot™ MAX Efficiency™ DH5α-T1R Competent Cells (Fisher, 12297016) were used to amplify the plasmids in this study. Plasmids were extracted and purified using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, 27104). Yeast transformations were performed as described previously (83) using the Frozen-EZ Yeast Transformation II Kit (ZYMO RESEARCH, T2001). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 13,000×g for 2 min after outgrowth for 3 h at 30 °C and 230 rpm. Cells were then suspended using PBS (pH = 7.2) for flow cytometry analysis.

Cell Culture and Transfection.

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma, D6429) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Gibco™ Penicillin-Streptomycin (10,000 U/mL) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. A day before transfection, HEK293T cells were seeded into 24-well cell culture plates at a density of 50,000 cells per well. Transfection mixtures were prepared by adding 200 ng mRNA or DNA with 1.8 µL Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, 11668027) in 100 µL serum-free Opti-MEM.

Flow Cytometry Detection.

Adherent cells were washed with 250 µL PBS (pH = 7.2). Next, 250 µL of 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, 25200056) was added into the well and cells were incubated for 5 min at 37 °C to completely detach cells. Then, 750 µL of DMEM was used to stop trypsin digestion. Samples were applied to the BD Accuri™ C6 Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences) directly, and GFP fluorescence was measured. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Firefly Luciferase Assay.

A day before transfection, HEK293T cells were seeded into 24-well cell culture plates at a density of 70,000 cells per well and transfected with 200ng DNA. After 72 h post transfection, cell pellets were lysed to quantify luciferase expression with a Luciferase Assay System (Promega, E1500) and a Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (ThermoFisher).

RNA Synthesis by In Vitro Transcription.

All RNA used in study was produced using the HiScribe™ T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (NEB, E2040S). For sgRNA, tracrRNA, and crRNA transcription, 75 ng synthetic Ultramer™ DNA Oligonucleotides (IDT) were used as templates (SI Appendix, Table S11). Details can be found in SI Appendix.

cDNA Synthesis.

cDNA synthesis was performed using the ProtoScript II First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (NEB, E6560) with 200 ng ATP-mRNA or 600 ng ZTP-mRNA in a total reaction volume of 20 µL. Reactions were incubated for 2 h at 42 °C. Then, 2 µL cDNA was added to 50 µL NEBNext High-Fidelity 2X PCR Master Mix (NEB, M0541S) containing specific primers G111 and G112. The target products were purified using a Monarch Gel Purification Kit (NEB, T1020S).

Poly(Z) Tailing of RNA.

First, 5 µg RNA, 1 mM ATP or ZTP, 1× Reaction Buffer, 40U RNase Inhibitor (NEB, M0314L), and 4U E. coli Poly(A) Polymerase (NEB, M0276L) were mixed in a 20 µL reaction volume. Reaction of tailing A was then incubated at 37 °C for 0.5 h, whereas tailing Z was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. RNA was purified using a Monarch RNA Cleanup Kit (NEB, T2040).

In Vitro Cleavage Activity Assay with Different crRNA or sgRNA.

The following assay was modified from Hirano et al. (84). Plasmid pIDT-DNA4 linearized by SspI restriction endonuclease was used as a DNA substrate. A 27 μL mixture containing 1.5 pmol LbCas12a, 2.5 pmol crRNA, and 1× buffer r2.1, was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, 300 ng of DNA substrate in 3 μL was added to the initial reaction. For Cas9, 2 μg of crRNA and 4μg tracrRNA were mixed in 20μL RNase free water. The RNA mixture was incubated for 5 min at 95 °C and cool down to room temperature. A 27 μL mixture containing 1.5 pmol SpCas9, 3 pmol crRNA:tracrRNA, and 1× buffer r3.1 was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, DNA substrate in 3 μL was added to the initial reaction. Then, 6 μL of sample was collected at 5, 25, 50, and 90 min and stopped by adding a 2 μL stop buffer containing 0.5% SDS and 40 mM EDTA. Each sample was subsequently analyzed by gel electrophoresis. The cleavage fraction percent was calculated using band intensities by a formula described previously (36).

Serum Stability Assay of RNA.

The following assay was modified from Park et. al. (85). Briefly, 1 µg RNA produced by in vitro transcription was added to 10 µL of PBS containing 5% Fetal Bovine Serum (Sigma, F2442), and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 5, 15, 30, or 60 min. Next, 10 µL of RNA dye (NEB, B0363S) was added and the mixture was heated at 70 °C for 5 min to denature RNA and proteins. RNA samples were loaded into a 2% agarose gel for analysis. Quantitative analysis was obtained by three independent experiments, and band intensity quantification was conducted using the GelAnalyzer.

In Vitro Cell Genome Editing and NGS Sequencing Analysis.

One day prior to transfection, HEK293T or Hela cells were seeded in a 48-well plate at a cell density of 1 to 2 × 104 cells per well. Medium was changed with 200 μL Opti-MEM on the day of transfection. Cas9 mRNA was purchased from Trilink (L-7206-100). ABE8e mRNA was obtained from Dr. David Liu’s lab at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. Amplicon sequencing data were analyzed with CRISPResso2 or BE-Analyzer (86, 87). Details can be found in SI Appendix.

Statistical Analysis and Graphical Illustrations.

Curve plotting and statistical analysis were performed using Prism 8 (GraphPad). Data are shown as means ± SEM for groups of two or more replicates or as individual values with the mean indicated. Graphical illustrations were created using BioRender (https://www.biorender.com/) and ChemDraw.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the funding support from NIH grant UG3 TR002636-01 and Hopewell Therapeutics Inc. We thank Prof. James A. Van Deventer from Tufts University Chemical and Biological Engineering Department for the gifts of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains BY4741, 4742 and 4743. We thank Prof. David R. Liu from Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT for the gifts of ABE8e mRNA. We thank Dr. Greg Newby from David R. Liu’ Lab for guidance for in vitro of transcription of mRNA.

Author contributions

S.G. and Q.X. designed research; S.G., H.G., J.K., Z.Y., D.S., Y.Z., M.C., C.X., and L.L. performed research; S.G. and Q.X. analyzed data; H.B., D.W., and D.S. revised manuscript; J.K. and Z.Y. assisted with base editing experiments; D.S. and Y.Z. assisted with cell experiments; M.C. assisted with PCR of DNA substrates; C.X. and L.L. assisted with extraction of plasmid; and S.G., H.B., D.W., D.S., and Q.X. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

Q.X. and S.G. are inventors of a pending patent related to this work filed by Tufts University. Q.X. is the founder and has equity in Hopewell Therapeutics Inc.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Kirnos M. D., Khudyakov I. Y., Alexandrushkina N. I., Vanyushin B. F., 2-Aminoadenine is an adenine substituting for a base in S-2L cyanophage DNA. Nature 270, 369–370 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michael W. G., Farren J. I., ZTCG: Viruses expand the genetic alphabet. Science 372, 460–461 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pezo V., et al. , Noncanonical DNA polymerization by aminoadenine-based siphoviruses. Science 372, 520–524 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sleiman D., et al. , A third purine biosynthetic pathway encoded by aminoadenine-based viral DNA genomes. Science 372, 516–520 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Y., et al. , A widespread pathway for substitution of adenine by diaminopurine in phage genomes. Science 372, 512–516 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khudyakov I. Y., Kirnos M. D., Alexandrushkina N. I., Vanyushin B. F., Cyanophage S-2L contains DNA with 2,6-diaminopurine substituted for adenine. Virology 88, 8–18 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czernecki D., Bonhomme F., Kaminski P.-A., Delarue M., Characterization of a triad of genes in cyanophage S-2L sufficient to replace adenine by 2-aminoadenine in bacterial DNA. Nat. Commun. 12, 4710 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czernecki D., Hu H., Romoli F., Delarue M., Structural dynamics and determinants of 2-aminoadenine specificity in DNA polymerase DpoZ of vibriophage ϕVC8. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 11974–11985 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lankaš F., et al. , Critical effect of the N2 amino group on structure, dynamics, and elasticity of DNA polypurine tracts. Biophys. J. 82, 2592–2609 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lebedev Y., et al. , Oligonucleotides containing 2-aminoadenine and 5-methylcytosine are more effective as primers for PCR amplification than their nonmodified counterparts. Genet. Anal. Biomol. Eng. 13, 15–21 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szekeres M., Matveyev A. V., Cleavage and sequence recognition of 2,6-diaminopurine-containing DNA by site-specific endonucleases. FEBS Lett. 222, 89–94 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaminski P. A., Mechanisms supporting aminoadenine-based viral DNA genomes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 79, 51 (2021), 10.1007/s00018-021-04055-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan Y., et al. , Transcriptional Perturbations of 2,6-Diaminopurine and 2-Aminopurine. ACS Chem. Biol. 17, 1672–1676 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang H., et al. , CRISPR-Cas9 recognition of enzymatically synthesized base-modified nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 1501–1511 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paunovska K., Loughrey D., Dahlman J. E., Drug delivery systems for RNA therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 265–280 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Q., Zhang Y., Yin H., Recent advances in chemical modifications of guide RNA, mRNA and donor template for CRISPR-mediated genome editing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 168, 246–258 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mir A., et al. , Heavily and fully modified RNAs guide efficient SpyCas9-mediated genome editing. Nat. Commun. 9, 2641 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beiranvand N., Freindorf M., Kraka E., Hydrogen bonding in natural and unnatural base pairs-A local vibrational mode study. Molecules 26, 2268 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hottin A., Marx A., Structural insights into the processing of nucleobase-modified nucleotides by DNA polymerases. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 418–427 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imashimizu M., Oshima T., Lubkowska L., Kashlev M., Direct assessment of transcription fidelity by high-resolution RNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 9090–9104 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potapov V., et al. , Base modifications affecting RNA polymerase and reverse transcriptase fidelity. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 5753–5763 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber G., et al. , Thermal equivalence of DNA duplexes without calculation of melting temperature. Nature Physics 2, 55–59 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailly C., Waring M. J., The use of diaminopurine to investigate structural properties of nucleic acids and molecular recognition between ligands and DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 4309–4314 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernández-Sierra M., et al. , E. coli gyrase fails to negatively supercoil diaminopurine-substituted DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 2305–2318 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheong C., Tinoco I. Jr., Chollet A., Thermodynamic studies of base pairing involving 2,6-diaminopurine. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 5115–5122 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Virstedt J., Berge T., Henderson R. M., Waring M. J., Travers A. A., The influence of DNA stiffness upon nucleosome formation. J. Struct. Biol. 148, 66–85 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chazin W. J., Rance M., Chollet A., Luepin W., Comparative NMR analysis of the decadeoxynucleotide d-(GCATTAATGC) 2 and an anlogue containing 2-aminoadenine. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 5507–5513 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard F. B., Chen C.-W., Cohen J. S., Miles H. T., Poly(d2NH2A-dT): Effect of 2-amino substituent on the B to Z transition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 118, 848–853 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pingoud A., Jeltsch A., Structure and function of type II restriction endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 3705–3727 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crick F., Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature 227, 561–563 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komar A. A., The Yin and Yang of codon usage. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25, R77–r85 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curran K. A., et al. , Short synthetic terminators for improved heterologous gene expression in yeast. ACS Synth. Biol. 4, 824–832 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Passmore L. A., Coller J., Roles of mRNA poly(A) tails in regulation of eukaryotic gene expression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 93–106 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hassan A. E. A., Sheng J., Zhang W., Huang Z., High fidelity of base pairing by 2-Selenothymidine in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 2120–2121 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J. Y., Doudna J. A., CRISPR technology: A decade of genome editing is only the beginning. Science 379, eadd8643 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zetsche B., et al. , Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a Class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell 163, 759–771 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamano T., et al. , Crystal structure of Cpf1 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell 165, 949–962 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X., et al. , Base editing with a Cpf1–cytidine deaminase fusion. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 324–327 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McMahon M. A., Prakash T. P., Cleveland D. W., Bennett C. F., Rahdar M., Chemically modified Cpf1-CRISPR RNAs mediate efficient genome editing in mammalian cells. Mol. Ther. 26, 1228–1240 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong D., et al. , The crystal structure of Cpf1 in complex with CRISPR RNA. Nature 532, 522–526 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh D., et al. , Real-time observation of DNA target interrogation and product release by the RNA-guided endonuclease CRISPR Cpf1 (Cas12a). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 5444–5449 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh D., et al. , Mechanisms of improved specificity of engineered Cas9s revealed by single-molecule FRET analysis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 347–354 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cromwell C. R., et al. , Incorporation of bridged nucleic acids into CRISPR RNAs improves Cas9 endonuclease specificity. Nat. Commun. 9, 1448 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Reilly D., et al. , Extensive CRISPR RNA modification reveals chemical compatibility and structure-activity relationships for Cas9 biochemical activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 546–558 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karmakar S., Behera D., Baig M. J., Molla K. A., “In vitro Cas9 cleavage assay to check guide RNA efficiency” in CRISPR-Cas Methods, Islam M. T., Molla K. A., Eds. Springer Protocols Handbooks. (Springer, US, New York, NY, 2021), pp. 23–39, 10.1007/978-1-0716-1657-4_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Porto E. M., Komor A. C., Slaymaker I. M., Yeo G. W., Base editing: Advances and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 19, 839–859 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jinek M., et al. , A programmable dual-RNA–guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nishimasu H., et al. , Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell 156, 935–949 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richter M. F., et al. , Phage-assisted evolution of an adenine base editor with improved Cas domain compatibility and activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 883–891 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arbab M., et al. , Base editing rescue of spinal muscular atrophy in cells and in mice. Science 380, eadg6518 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grunewald J., et al. , A dual-deaminase CRISPR base editor enables concurrent adenine and cytosine editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 861–864 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raiber E.-A., Hardisty R., van Delft P., Balasubramanian S., Mapping and elucidating the function of modified bases in DNA. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0069 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bilyard M. K., Becker S., Balasubramanian S., Natural, modified DNA bases. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 57, 1–7 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hutinet G., Lee Y.-J., de Crécy-Lagard V., Weigele Peter R., Hinton D., Hypermodified DNA in viruses of E. coli and Salmonella. EcoSal Plus 9, eESP-0028-2019 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malyshev D. A., et al. , A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet. Nature 509, 385–388 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y., et al. , A semi-synthetic organism that stores and retrieves increased genetic information. Nature 551, 644–647 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoshika S., et al. , Hachimoji DNA and RNA: A genetic system with eight building blocks. Science 363, 884–887 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Franco M. K., Koutmou K. S., Chemical modifications to mRNA nucleobases impact translation elongation and termination. Biophys. Chem. 285, 106780 (2022), 10.1016/j.bpc.2022.106780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hua Y., Vickers T. A., Baker B. F., Bennett C. F., Krainer A. R., Enhancement of SMN2 Exon 7 inclusion by antisense oligonucleotides targeting the exon. PLoS Biol. 5, e73 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown K. M., et al. , Expanding RNAi therapeutics to extrahepatic tissues with lipophilic conjugates. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1500–1508 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu C., et al. , An intranasal ASO therapeutic targeting SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 13, 4503 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mulligan M. J., et al. , Phase I/II study of COVID-19 RNA vaccine BNT162b1 in adults. Nature 586, 589–593 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jackson L. A., et al. , An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1920–1931 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Christie K. A., et al. , Precise DNA cleavage using CRISPR-SpRYgests. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 409–416 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang J., et al. , Engineering a PAM-flexible SpdCas9 variant as a universal gene repressor. Nat. Commun. 12, 6916 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Awwad S. W., Serrano-Benitez A., Thomas J. C., Gupta V., Jackson S. P., Revolutionizing DNA repair research and cancer therapy with CRISPR–Cas screens. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 477–494 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Donohoue P. D., et al. , Conformational control of Cas9 by CRISPR hybrid RNA-DNA guides mitigates off-target activity in T cells. Mol. Cell 81, 3637–3649.e3635 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ryan D. E., et al. , Improving CRISPR–Cas specificity with chemical modifications in single-guide RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 792–803 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fu Y., Sander J. D., Reyon D., Cascio V. M., Joung J. K., Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 279–284 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kocak D. D., et al. , Increasing the specificity of CRISPR systems with engineered RNA secondary structures. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 657–666 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Okafor I. C., et al. , Single molecule analysis of effects of non-canonical guide RNAs and specificity-enhancing mutations on Cas9-induced DNA unwinding. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 11880–11888 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Park H., et al. , Extension of the crRNA enhances Cpf1 gene editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Commun. 9, 3313 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mouchiroud D., et al. , The distribution of genes in the human genome. Gene 100, 181–187 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saccone S., Federico C., Bernardi G., Localization of the gene-richest and the gene-poorest isochores in the interphase nuclei of mammals and birds. Gene 300, 169–178 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim D., et al. , Genome-wide analysis reveals specificities of Cpf1 endonucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 863–868 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kleinstiver B. P., et al. , Genome-wide specificities of CRISPR-Cas Cpf1 nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 869–874 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang T., Wei J. J., Sabatini D. M., Lander E. S., Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science 343, 80–84 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsai S. Q., et al. , GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 187–197 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cui Z., et al. , Cas13d knockdown of lung protease Ctsl prevents and treats SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 1056–1064 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Akbari O. S., et al. , Safeguarding gene drive experiments in the laboratory. Science 349, 927–929 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ye Z., et al. , In vitro engineering chimeric antigen receptor macrophages and T cells by lipid nanoparticle-mediated mRNA delivery. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 8, 722–733 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matsuda T., Cepko C. L., Electroporation and RNA interference in the rodent retina in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 16–22 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gao S., et al. , Iterative integration of multiple-copy pathway genes in Yarrowia lipolytica for heterologous β-carotene production. Metab. Eng. 41, 192–201 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hirano S., et al. , Structural basis for the promiscuous PAM recognition by Corynebacterium diphtheriae Cas9. Nat. Commun. 10, 1968 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Park H. M., et al. , Extension of the crRNA enhances Cpf1 gene editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Commun. 9, 3313 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Clement K., et al. , CRISPResso2 provides accurate and rapid genome editing sequence analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 224–226 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hwang G.-H., et al. , Web-based design and analysis tools for CRISPR base editing. BMC Bioinform. 19, 542 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.