Abstract

Rosa (Rosaceae) is an important ornamental and medicinal plant genus worldwide, with several species being cultivated in China. Members of Sporocadaceae (pestalotioid fungi) are globally distributed and include endophytes, saprobes but also plant pathogens, infecting a broad range of host plants on which they can cause important plant diseases. Although several Sporocadaceae species were recorded to inhabit Rosa spp., the taxa occurring on Rosa remain largely unresolved. In this study, a total of 295 diseased samples were collected from branches, fruits, leaves and spines of eight Rosa species (R. chinensis, R. helenae, R. laevigata, R. multiflora, R. omeiensis, R. rugosa, R. spinosissima and R. xanthina) in Gansu, Henan, Hunan, Qinghai, Shaanxi Provinces and the Ningxia Autonomous Region of China. Subsequently 126 strains were obtained and identified based on comparisons of DNA sequence data. Based on these results 15 species residing in six genera of Sporocadaceae were delineated, including four known species (Pestalotiopsis chamaeropis, Pes. rhodomyrtus, Sporocadus sorbi and Spo. trimorphus) and 11 new species described here as Monochaetia rosarum, Neopestalotiopsis concentrica, N. subepidermalis, Pestalotiopsis tumida, Seimatosporium centrale, Seim. gracile, Seim. nonappendiculatum, Seim. parvum, Seiridium rosae, Sporocadus brevis, and Spo. spiniger. This study also represents the first report of Pes. chamaeropis, Pes. rhodomyrtus and Spo. sorbi on Rosa. The overall data revealed that Pestalotiopsis was the most prevalent genus, followed by Seimatosporium, while Pes. chamaeropis and Pes. rhodomyrtus were the two most prevalent species. Analysis of Sporocadaceae abundance on Rosa species and plant organs revealed that spines of R. chinensis had the highest species diversity.

Citation: Peng C, Crous PW, Jiang N, et al. 2022. Diversity of Sporocadaceae (pestalotioid fungi) from Rosa in China. Persoonia 49: 201–260. https://doi.org/10.3767/persoonia.2022.49.07.

Keywords: Amphisphaeriales, Ascomycota, new taxa, phylogeny, taxonomy

INTRODUCTION

Sporocadaceae (Xylariales, Sordariomycetes) is a well-known fungal family containing pestalotioid fungi. Traditionally, pestalotioid fungi are circumscribed as a group of coelomycetous fungi having fusoid or nearly fusoid, multi-septate conidia, with appendages at one or both ends (Nag Raj 1993, Maharachchikumbura et al. 2014, Liu et al. 2019).

Pestalotioid fungi were previously classified in Amphisphaeriaceae, Amphisphaeriales (Eriksson 1986, Samuels et al. 1987). Subsequently, several studies suggested that Amphisphaeriales should not be accepted due to the lack of stable phylogenetic support, and hence it was treated as synonym of Xylariales (Eriksson 1987, Kang et al. 1999, Smith et al. 2003). Later, Senanayake et al. (2015) revised Xylariomycetidae and transferred several important genera of pestalotioid fungi from Amphisphaeriaceae to three new families, Bartaliniaceae, Discosiaceae and Pestalotiopsidaceae. Genera such as Bartalinia and Broomella were transferred to Bartaliniaceae, Discosia and Seimatosporium to Discosiaceae, and Neopestalotiopsis, Pestalotiopsis, Pseudopestalotiopsis, Monochaetia and Seiridium to Pestalotiopsidaceae. Crous et al. (2015a) introduced a new family Robillardaceae to accommodate Robillarda. Subsequently, Jaklitsch et al. (2016) grouped the pestalotioid fungi into a single family and revived the older family name Sporocadaceae. Therefore, Bartaliniaceae, Discosiaceae, Pestalotiopsidaceae and Robillardaceae became synonyms of Sporocadaceae. These families were classified in Amphisphaeriales which was resurrected instead of Xylariales (Senanayake et al. 2015). Recently, several studies treated Amphisphaeriales as a distinct order (Senanayake et al. 2015, Samarakoon 2016, Hongsanan et al. 2017, Wijayawardene et al. 2020) . Based on multi-locus phylogenetic analyses with morphological characters, Liu et al. (2019) confirmed the natural taxonomic status of Sporocadaceae, which currently contains 33 genera (Liu et al. 2019, Wijayawardene et al. 2020).

Sporocadaceae contains many important plant pathogens associated with diseases on a wide range of plant hosts worldwide (Maharachchikumbura et al. 2014, Liu et al. 2019, Norphanphoun et al. 2019). Within the family, pestalotiopsis-like taxa (Neopestalotiopsis, Pestalotiopsis and Pseudopestalotiopsis) are the group that has received the most attention (Maharachchikumbura et al. 2014, Wang et al. 2019b, Gualberto et al. 2021) . For example, N. mangiferae and N. palmarum cause leaf diseases on a variety of cash crops in Brazil, South Africa and India, weakening tree vigour, and even reducing yield in severe cases (Spaulding 1949, Mendes et al. 1998, Crous et al. 2000). Pestalotiopsis pini is an emerging pathogen causing shoot blight and stem necrosis on Pinus pinea (Silva et al. 2020), while in Australia, Pes. telopeae causes a serious leaf spot disease of Telopea spp. (Maharachchikumbura et al. 2014). Furthermore, pestalotiopsis-like fungi are widespread, occur on many hosts in Proteaceae, and are generally regarded to be saprobic or weakly pathogenic (Crous et al. 2013). Neopestalotiopsis protearum was recorded as causing leaf spots and blight on several Protea and Leucospermum hosts in Zimbabwe (Swart et al. 1999, Crous et al. 2011b). This species is also reported from Australia and Proteaceae in the Western Cape Province of South Africa (Crous et al. 2013). Neopestalotiopsis protearum is probably only a problem of commercial importance in summer rainfall areas and it has been intercepted at quarantine inspection points (Taylor 2000). Pestalotiopsis montellicoides was isolated from Protea cynaroides leaves from South Africa (Mordue 1986), and a Pestalotiopsis sp. (asexual Pestalosphaeria leucospermi), was described from living leaves of a Leucospermum sp. in New Zealand (Samuels et al. 1987). In Portugal and the Canary Islands, a species of Pestalotiopsis is commonly associated with tip blight and leaf spot symptoms on Protea, Leucospermum and Leucadendron species, although pathogenicity studies have not yet been conducted (Crous et al. 2013). Members of Pseudopestalotiopsis are cosmopolitan in distribution and have often been regarded as leaves spot pathogens occurring on a broad host range, e.g., Pse. elaeidis and Pse. theae cause foliar diseases in more than 60 hosts around the world in tropical and subtropical areas (Maharachchikumbura et al. 2014, Liu et al. 2019). In addition to pestalotiopsis-like species, the diseases caused by other groups of Sporocadaceae cannot be underestimated. Cypress canker is caused by several species of Seiridium (Bonthond et al. 2018), Allelochaeta is an important foliar pathogen of eucalypts (Crous et al. 2019b), and some species of Distononappendiculata and Truncatella cause diseases on a wide range of hosts (Crous et al. 2011a, 2013, Liu et al. 2019).

Sporocadaceae has an extremely rich species diversity in China. The investigation of the biodiversity of plant-associated pestalotioid fungi in China date back as far as 1886, when Patouillard collected and described many species from Yunnan (Patouillard 1886). With subsequent research, a total of 310 species belonging to 22 genera were reported in China, inhabiting many hosts, especially in Juglandaceae, Myrtaceae, Pinaceae, Podocarpaceae, Rhododendronaceae, Rosaceae, Theaceae and Vitaceae (Chen 2003, Ge et al. 2009, Liu et al. 2019). Most of the previous studies on Sporocadaceae in China focused on Pestalotiopsis. Previous investigations on Pestalotiopsis in China were summarised by Tai (1979), in which 38 species from 52 plant hosts were listed. A wider survey included 153 species obtained from at least 406 plant species, 67 of which are endemic to China (Ge et al. 2009). Hitherto 203 species have been reported in China, accounting for more than 65 % of the total records of this family in China. However, the distribution of 11 genera in China is still unknown, i.e., Ciliochorella, Clypeosphaeria, Diploceras, Disaeta, Distononappendiculata, Heterotruncatella, Hyalotiella, Morinia, Nonappendiculata, Parabartalinia and Xenseimatosporium. Furthermore, many species of Sporocadaceae can also cause serious plant diseases in China. Pseudopestalotiopsis camelliae-sinensis is responsible for grey blight of tea plants and causes serious losses in some tea-growing regions of China (Wang et al. 2019b), while Pes. apiculata causes severe top blight of cedar seedlings (Ge et al. 2009). Monochaetia kansensis and M. monochaeta cause leaf spots on a variety of Quercus and Castanea plants (Teng 1996, Chen et al. 2002, Chen 2003), and Truncatella laurocerasi causes grey blight and leaf spot on Eriobotrya in China (Tai 1979). Considering the importance of pestalotioid fungi, it is necessary to clarify the species diversity and distribution of Sporocadaceae in China in a modern taxonomic framework.

Rosa (Rosaceae) is widely distributed in tropical to cold temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, including approximately 200 species (Bruneau et al. 2007, Fougère-Danezan et al. 2015). China is the main distribution area of Rosa plants globally (Wu et al. 2003). There are currently 95 Rosa spp. in China (65 of which are endemic), accounting for about 41 % of the global total (Jin 2020). Rosa species are widely cultivated and are of immense economic importance in China (Liu 2016). As important ornamental plants, Rosa spp. play a key role in Chinese landscaping (Zhang et al. 2009). Furthermore, Rosa species are important raw materials for the spice and food industry, and a rose industry has been established in many parts of China, generating huge income for the local economy (Wang 2021). Most Rosa spp. can be used in traditional Chinese medicines, having great nutritional and medicinal value (Wang 2021). In addition to these, Rosa spp. are important resource species for ecological and vegetation restoration, having great ecological value in China, because many rose species have strong resistance to stress and can survive in harsh environments (Liu 2016).

Many fungal taxa such as Botryosphaeria dothidea, Botrytis cinerea, Chaetomella raphigera, Colletotrichum siamense, Cytospora spp., Diplocarpon rosae, Elsinoe rosarum and Lasiodiplodia theobromae have in the past been identified as the causal agents of various diseases of Rosa spp. in China, and severely limited their production. (Zhang et al. 2014, Bagsic et al. 2016, Chen et al. 2016, Debener 2019, Feng et al. 2019 Jia et al. 2019, Munoz et al. 2019, Pan et al. 2020). Members of Sporocadaceae have also been reported to cause diseases on Rosa spp. Examples include cankers caused by N. rosicola, dieback caused by Ciliochorella mangiferae and Robillarda sessilis, stem lesions caused by N. rosae and R. sessilis, and leaf spots caused by Diploceras discosioides, Discosia artocreas and Truncatella angustata (Weiss 1950, Mathur 1979, Peregrine & Ahmad 1982, Eken et al. 2009, Maharachchikumbura et al. 2014, Jiang et al. 2018). Furthermore, Rosa has proven to represent a rich niche of undescribed species of Sporocadaceae, with many remaining poorly identified, as the generic concepts have been in flux until recently (Liu et al. 2019). Therefore, conducting detailed surveys of pestalotioid fungi from Rosa spp. in China was necessary. The aims of the present study were thus to identify these fungi based on phylogenetic analyses and morphological comparisons, describe the species new to science, and gain a better understanding of the diversity and prevalence of Sporocadaceae associated with Rosa spp. in China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling and isolation

A total of 295 Rosa samples (branches, fruits, leaves and spines) showing disease symptoms (Fig. 1) were collected from five provinces (Gansu, Henan, Hunan, Qinghai and Shaanxi) and the Ningxia Autonomous Region of China, which are the main production areas of Rosa plants in China. The Rosa species sampled include R. chinensis, R. helenae, R. laevigata, R. multiflora, R. omeiensis, R. rugosa, R. spinosissima and R. xanthina.

Fig. 1.

Disease symptoms on Rosa associated with infection by Sporocadaceae. a–c. Leaves spots on Rosa rugosa caused by Pestalotiopsis rhodomyrtus; d–e. lesion developing on the fruits of Rosa laevigata infected by Seimatosporium nonappendiculatum; f. dying bush; g–h. dieback on (g) Rosa rugosa and (h) Rosa xanthina caused by Seiridium rosae and Sporocadus sorbi; i–j. sporocarps of Pestalotiopsis chamaeropis and Seimatosporium centrale on the spines of (i) Rosa rugosa and (j) Rosa chinensis.

A total of 126 strains were obtained by removing the spore mass from conidiomata and generating single spore colonies, or plating superficially sterilised diseased tissue on potato dextrose agar (PDA, 20 % diced potatoes, 2 % agar and 2 % glucose) and incubating Petri dishes at 25 °C in the dark for 2–3 d. When colonies just formed, they were hyphal-tipped and transferred to fresh PDA Petri dishes (Crous et al. 2019a). Type specimens of new species from this study were deposited in the Museum of the Beijing Forestry University (BJFC), and ex-type living cultures were deposited in the China Forestry Culture Collection Centre (CFCC), Beijing, China.

Morphological analyses

Cultures were incubated on PDA at 25 °C in a 12 h day/night regime (Crous et al. 2019a). After 15 d, colony diameters were measured and colony colours were rated according to Rayner (1970). Slide preparations were mounted in lactic acid or water, from colonies sporulating on PDA, autoclaved pine needles on 2 % tap water agar (Smith et al. 1996), and incubated at 25 °C under continuous nuv-light to promote sporulation. Sections through stromata were made by hand. Observations were made with a Leica DM 2500 dissecting microscope (Wetzlar, Germany), and with a Nikon Eclipse 80i compound microscope using differential interference contrast (DIC) illumination and images recorded on a Nis DS-Ri2 camera with the Nikon NisElements F4.30.01 software. Conidial length was measured from the base of the basal cell to the base of the apical appendage, and conidial width was measured at the widest point of the conidium (Bonthond et al. 2018). Taxonomic novelties were deposited in MycoBank (Crous et al. 2004).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from axenic cultures using a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) protocol (Doyle & Doyle 1990). DNA products were stored at -20 °C. The extracted DNA was used as template for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR reaction primers (forward and reverse) of each fungal genus are found in Table 1. PCR parameters were initiated with 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 34 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at a suitable temperature for 30 s (56 °C for ITS and LSU, 52 °C for TEF, 52 °C for RPB2 and 60 °C for TUB), and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, and terminated with a final elongation step at 72 °C for 10 min. The final PCR products were examined by electrophoresis in 2 % agarose gels. The amplified PCR products were sent to a commercial sequencing provider (Tsingke Biotechnology Co. Ltd, Beijing, China).

Table 1.

PCR reaction primers (forward and reverse) for amplification of gene loci of each fungal genus.

| Genus | Loci used for amplification | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | RPB2 | TEF | TUB | ||

| Monochaetia | ITS1/ITS4 | LROR/LR5 | RPB2-5F2/fRPB2-7cR | Liu et al. (2019), Jiang et al. (2021) | ||

| Neopestalotiopsis | ITS1/ITS4 | LROR/LR5 | RPB2-5F2/fRPB2-7cR | EF1-728F/EF-2 | T1/Bt2b | Liu et al. (2019), Norphanphoun et al. (2019), Jiang et al. (2021) |

| Pestalotiopsis | ITS1/ITS4 | LROR/LR5 | RPB2-5F2/fRPB2-7cR | EF1-728F/EF-2 | T1/Bt2b | Liu et al. (2019), Norphanphoun et al. (2019), Jiang et al. (2021) |

| Seimatosporium | ITS1/ITS4 | LROR/LR5 | RPB2-5F2/fRPB2-7cR | Goonasekara et al. (2016), Wijayawardene et al. (2016a), Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Seiridium | ITS1/ITS4 | LROR/LR5 | RPB2-5F2/fRPB2-7cR | EF1-728F/EF-2 | T1/Bt2b | Jiang et al. (2019), Liu et al. (2019), Marin-Felix et al. (2019) |

| Sporocadus | ITS1/ITS4 | LROR/LR5 | RPB2-5F2/fRPB2-7cR | EF1-728F/EF-2 | T1/Bt2b | Liu et al. (2019) |

Phylogenetic analyses

All nucleotide sequences generated from different primer pairs in this study were deposited in GenBank (Table 2). Sequences were BLASTn searched in NCBI to obtain the related sequences from recent publications and were analysed (Table 3). Sequences were aligned in MAFFT v. 7 at the web server (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server) (Katoh & Standley 2013, Katoh et al. 2019) and manually adjusted in MEGA v. 6 (Tamura et al. 2013).

Table 2.

Isolates sequenced and used for phylogenetic analyses in the current study.

| Species1 | Culture no. | Status2 | Host | Tissues | Origin | GenBank accession no. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | RPB2 | TEF | TUB | ||||||

| Monochaetia rosarum | CFCC55172 = ROC 099 | T | Rosa chinensis | branches | Nanyang, Henan | MZ292088 | OK560346 | OL742111 | OL814484 | OM103654 |

| CFCC55173 = ROC 100 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Nanyang, Henan | MZ292089 | OK560347 | OL742112 | OL814485 | OM103655 | ||

| ROC 098 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Nanyang, Henan | MZ292090 | OK560348 | OL742113 | OL814486 | OM103656 | ||

| ROC 101 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Nanyang, Henan | MZ292091 | OK560349 | OL742114 | OL814487 | OM103657 | ||

| Neopestalotiopsis concentrica | CFCC 55162 = ROC 53 | T | Rosa rugosa | spines | Xinyang, Henan | OK560707 | OK560440 | OL742115 | OM622433 | OM117698 |

| CFCC 55163 = ROC 64 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Xinyang, Henan | OK560708 | OK560441 | OL742116 | OM622434 | OM117699 | ||

| ROC 135 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Xinyang, Henan | OK560709 | OK560442 | OL742117 | OM622435 | OM117700 | ||

| ROC 136 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Xinyang, Henan | OK560710 | OK560443 | OL742118 | OM622436 | OM117701 | ||

| ROC 137 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Nanyang, Henan | OK560711 | OK560444 | OL742119 | OM622437 | OM117702 | ||

| ROC 138 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Nanyang, Henan | OK560712 | OK560445 | OL742120 | OM622438 | OM117703 | ||

| ROC 140 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Nanyang, Henan | OK560713 | OK560446 | OL742121 | OM622439 | OM117704 | ||

| ROC 141 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Nanyang, Henan | OK560714 | OK560447 | OL742122 | OM622440 | OM117705 | ||

| ROC 142 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Nanyang, Henan | OK560715 | OK560448 | OL742123 | OM622441 | OM117706 | ||

| N. subepidermalis | CFCC 55160 = ROC 161 | T | Rosa rugosa | spines | Xinyang, Henan | OK560699 | OK560432 | – | OM622425 | OM117690 |

| ROC 162 | Rosa rugosa | spines | Xinyang, Henan | OK560700 | OK560433 | – | OM622426 | OM117691 | ||

| CFCC 55161 = ROC 169 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Xinyang, Henan | OK560701 | OK560434 | – | OM622427 | OM117692 | ||

| ROC 170 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Xinyang, Henan | OK560702 | OK560435 | – | OM622428 | OM117693 | ||

| ROC 171 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Xinyang, Henan | OK560703 | OK560436 | – | OM622429 | OM117694 | ||

| ROC 172 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Xinyang, Henan | OK560704 | OK560437 | – | OM622430 | OM117695 | ||

| ROC 173 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Xinyang, Henan | OK560705 | OK560438 | – | OM622431 | OM117696 | ||

| ROC 174 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Xinyang, Henan | OK560706 | OK560439 | – | OM622432 | OM117697 | ||

| Pestalotiopsis chamaeropis | CFCC 55156 = ROC 23-1 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560574 | OK560306 | OL742124 | OL814488 | OM158138 | |

| ROC 270 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560575 | OK560307 | OL742125 | OL814489 | OM158139 | ||

| ROC 272 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560576 | OK560308 | OL742126 | OL814490 | OM158140 | ||

| ROC 273 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560577 | OK560309 | OL742127 | OL814491 | OM158141 | ||

| ROC 275 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560578 | OK560310 | OL742128 | OL814492 | OM158142 | ||

| CFCC 55157 = ROC 23-2 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560579 | OK560311 | OL742129 | OL814493 | OM158143 | ||

| ROC 276 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560580 | OK560312 | OL742130 | OL814494 | OM158144 | ||

| ROC 278 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560581 | OK560313 | OL742131 | OL814495 | OM158145 | ||

| ROC 279 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560582 | OK560314 | OL742132 | OL814496 | OM158146 | ||

| ROC 280 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560583 | OK560315 | OL742133 | OL814497 | OM158147 | ||

| ROC 281 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560584 | OK560316 | OL742134 | OL814498 | OM158148 | ||

| ROC 282 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560585 | OK560317 | OL742135 | OL814499 | OM158149 | ||

| ROC 283 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560586 | OK560318 | OL742136 | OL814500 | OM158150 | ||

| ROC 286 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560587 | OK560319 | OL742137 | OL814501 | OM158151 | ||

| ROC 289 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560588 | OK560320 | OL742138 | OL814502 | OM158152 | ||

| ROC 290 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560589 | OK560321 | OL742139 | OL814503 | OM158153 | ||

| ROC 292 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560590 | OK560322 | OL742140 | OL814504 | OM158154 | ||

| ROC 293 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560591 | OK560323 | OL742141 | OL814505 | OM158155 | ||

| Pes. rhodomyrtus | ROC 056 | Rosa rugosa | leaves | Nanyang, Henan | OK560592 | – | – | OL814506 | OM158156 | |

| ROC 057 | Rosa rugosa | leaves | Nanyang, Henan | OK560593 | – | – | OL814507 | OM158157 | ||

| ROC 058 | Rosa rugosa | leaves | Nanyang, Henan | OK560594 | – | – | OL814508 | OM158158 | ||

| ROC 059 | Rosa rugosa | leaves | Nanyang, Henan | OK560595 | – | – | OL814509 | OM158159 | ||

| ROC 060 | Rosa rugosa | leaves | Nanyang, Henan | OK560596 | – | – | OL814510 | OM158160 | ||

| ROC 061 | Rosa rugosa | leaves | Nanyang, Henan | OK560597 | – | – | OL814511 | OM158161 | ||

| ROC 062 | Rosa rugosa | leaves | Nanyang, Henan | OK560598 | – | – | OL814512 | OM158162 | ||

| ROC 303 | Rosa multiflora | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK560599 | – | – | OL814513 | OM158163 | ||

| ROC 304 | Rosa multiflora | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK560600 | – | – | OL814514 | OM158164 | ||

| ROC 305 | Rosa multiflora | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK560601 | – | – | OL814515 | OM158165 | ||

| ROC 306 | Rosa multiflora | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK560602 | – | – | OL814516 | OM158166 | ||

| ROC 307 | Rosa multiflora | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK560603 | – | – | OL814517 | OM158167 | ||

| ROC 309 | Rosa multiflora | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK560604 | – | – | OL814518 | OM158168 | ||

| ROC 311 | Rosa multiflora | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK560605 | – | – | OL814519 | OM158169 | ||

| Pes. rhodomyrtus (cont.) | ROC 356 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Changsha, Hunan | OK560606 | – | – | OL814520 | OM158170 | |

| ROC 357 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Changsha, Hunan | OK560607 | – | – | OL814521 | OM158171 | ||

| ROC 358 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Changsha, Hunan | OK560608 | – | – | OL814522 | OM158172 | ||

| ROC 359 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Changsha, Hunan | OK560609 | – | – | OL814523 | OM158173 | ||

| Pes. tumida | CFCC 55158 = ROC 110 | T | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560610 | OK560324 | OL742142 | OL814524 | OM158174 |

| ROC 109 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560611 | OK560325 | OL742143 | OL814525 | OM158175 | ||

| ROC 108 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560612 | OK560326 | OL742144 | OL814526 | OM158176 | ||

| CFCC 55159 = ROC 234 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560613 | OK560327 | OL742145 | OL814527 | OM158177 | ||

| ROC 235 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560614 | OK560328 | OL742146 | OL814528 | OM158178 | ||

| ROC 236 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560615 | OK560329 | OL742147 | OL814529 | OM158179 | ||

| ROC 237 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560616 | OK560330 | OL742148 | OL814530 | OM158180 | ||

| ROC 238 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560617 | OK560331 | OL742149 | OL814531 | OM158181 | ||

| ROC 240 | Rosa chinensis | branches | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560618 | OK560332 | OL742150 | OL814532 | OM158182 | ||

| Seimatosporium centrale | CFCC 55166 = ROC 003 | T | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560629 | OK560399 | ON055447 | OM986918 | OM301641 |

| ROC 001 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560630 | OK560400 | ON055448 | OM986919 | OM301642 | ||

| ROC 002 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560631 | OK560401 | ON055449 | OM986920 | OM301643 | ||

| CFCC 55169 =ROC 014 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Baoji, Shaanxi | OK560632 | OK560402 | ON055450 | OM986921 | OM301644 | ||

| ROC 015 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Baoji, Shaanxi | OK560633 | OK560403 | ON055451 | OM986922 | OM301645 | ||

| ROC 016 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Baoji, Shaanxi | OK560634 | OK560404 | ON055452 | OM986923 | OM301646 | ||

| ROC 145 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560635 | OK560405 | ON055453 | OM986924 | OM301647 | ||

| ROC 146 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560636 | OK560406 | ON055454 | OM986925 | OM301648 | ||

| ROC 147 | Rosa chinensis | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560637 | OK560407 | ON055455 | OM986926 | OM301649 | ||

| Seim, gracile | CFCC 55167 = ROC 004 | T | Rosa xanthina | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560638 | OK560408 | ON055456 | OM986927 | OM301650 |

| ROC 005 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560639 | OK560409 | ON055457 | OM986928 | OM301651 | ||

| ROC 006 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560640 | OK560410 | ON055458 | OM986929 | OM301652 | ||

| ROC 007 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560641 | OK560411 | ON055459 | OM986930 | OM301653 | ||

| ROC 008 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560642 | OK560412 | ON055460 | OM986931 | OM301654 | ||

| ROC 009 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560643 | OK560413 | ON055461 | OM986932 | OM301655 | ||

| ROC 010 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560644 | OK560414 | ON055462 | OM986933 | OM301656 | ||

| ROC 011 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560645 | OK560415 | ON055463 | OM986934 | OM301657 | ||

| ROC 012 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Tianshui, Gansu | OK560646 | OK560416 | ON055464 | OM986935 | OM301658 | ||

| Seim, nonappendiculatum | CFCC 55168 = ROC 377 | T | Rosa laevigata | fruits | Guyuan, Ningxia | OK560657 | OK560427 | ON055475 | OM986946 | OM301669 |

| ROC 378 | Rosa laevigata | fruits | Guyuan, Ningxia | OK560658 | OK560428 | ON055476 | OM986947 | OM301670 | ||

| ROC 379 | Rosa laevigata | fruits | Guyuan, Ningxia | OK560659 | OK560429 | ON055477 | OM986948 | OM301671 | ||

| ROC 380 | Rosa laevigata | fruits | Guyuan, Ningxia | OK560660 | OK560430 | ON055478 | OM986949 | OM301672 | ||

| ROC 381 | Rosa laevigata | fruits | Guyuan, Ningxia | OK560661 | OK560431 | ON055479 | OM986950 | OM301673 | ||

| Seim, parvum | CFCC 55164 = ROC 038 | T | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Huangnan, Qinghai | OK560647 | OK560417 | ON055465 | OM986936 | OM301659 |

| ROC 039 | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Huangnan, Qinghai | OK560648 | OK560418 | ON055466 | OM986937 | OM301660 | ||

| ROC 040 | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Huangnan, Qinghai | OK560649 | OK560419 | ON055467 | OM986938 | OM301661 | ||

| ROC 041 | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Huangnan, Qinghai | OK560650 | OK560420 | ON055468 | OM986939 | OM301662 | ||

| ROC 042 | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Huangnan, Qinghai | OK560651 | OK560421 | ON055469 | OM986940 | OM301663 | ||

| ROC 043 | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Huangnan, Qinghai | OK560652 | OK560422 | ON055470 | OM986941 | OM301664 | ||

| CFCC 55165 =ROC 017 | Rosa helenae | spines | Huangnan, Qinghai | OK560653 | OK560423 | ON055471 | OM986942 | OM301665 | ||

| ROC 018 | Rosa helenae | spines | Huangnan, Qinghai | OK560654 | OK560424 | ON055472 | OM986943 | OM301666 | ||

| ROC 019 | Rosa helenae | spines | Huangnan, Qinghai | OK560655 | OK560425 | ON055473 | OM986944 | OM301667 | ||

| ROC 020 | Rosa helenae | spines | Huangnan, Qinghai | OK560656 | OK560426 | ON055474 | OM986945 | OM301668 | ||

| Seiridium rosae | CFCC 55174 = ROC 208 | T | Rosa rugosa | branches | Guyuan, Ningxia | OK560681 | OK560394 | OL742151 | OL814533 | OM313314 |

| ROC 209 | Rosa rugosa | branches | Guyuan, Ningxia | OK560682 | OK560395 | OL742152 | OL814534 | OM313315 | ||

| CFCC 55175 = ROC 267 | Rosa rugosa | branches | Guyuan, Ningxia | OK560683 | OK560396 | OL742153 | OL814535 | OM313316 | ||

| ROC 268 | Rosa rugosa | branches | Guyuan, Ningxia | OK560684 | OK560397 | OL742154 | OL814536 | OM313317 | ||

| Sporocadus brevis | CFCC 55170 = ROC 091 | T | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK655780 | OK560371 | OL742155 | OL814537 | OM401659 |

| ROC 092 | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK655781 | OK560372 | OL742156 | OL814538 | OM401660 | ||

| ROC 093 | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK655782 | OK560373 | OL742157 | OL814539 | OM401661 | ||

| Sporocadus brevis (cont.) | ROC 094 | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK655783 | OK560374 | OL742158 | OL814540 | OM401662 | |

| ROC 095 | Rosa spinosissima | spines | Gannan, Gansu | OK655784 | OK560375 | OL742159 | OL814541 | OM401663 | ||

| Spo. sorbi | ROC 105 | Rosa xanthina | branches | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655785 | OK560376 | OL742160 | OL814542 | OM401664 | |

| ROC 102 | Rosa xanthina | branches | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655786 | OK560377 | OL742161 | OL814543 | OM401665 | ||

| ROC 103 | Rosa xanthina | branches | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655787 | OK560378 | OL742162 | OL814544 | OM401666 | ||

| ROC 159 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Ganan, Gansu | OK655788 | OK560379 | OL742163 | OL814545 | OM401667 | ||

| ROC 160 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Ganan, Gansu | OK655789 | OK560380 | OL742164 | OL814546 | OM401668 | ||

| ROC 161 | Rosa xanthina | spines | Ganan, Gansu | OK655790 | OK560381 | OL742165 | OL814547 | OM401669 | ||

| Spo. spiniger | ROC 119 | T | Rosa omeiensis | spines | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655791 | OK560382 | OL742166 | OL814548 | OM401670 |

| ROC 120 | Rosa omeiensis | spines | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655792 | OK560383 | OL742167 | OL814549 | OM401671 | ||

| ROC 121 | Rosa omeiensis | spines | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655793 | OK560384 | OL742168 | OL814550 | OM401672 | ||

| ROC 122 | Rosa omeiensis | spines | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655794 | OK560385 | OL742169 | OL814551 | OM401673 | ||

| ROC 123 | Rosa omeiensis | spines | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655795 | OK560386 | OL742170 | OL814552 | OM401674 | ||

| ROC 124 | Rosa omeiensis | spines | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655796 | OK560387 | OL742171 | OL814553 | OM401675 | ||

| ROC 125 | Rosa omeiensis | spines | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655797 | OK560388 | OL742172 | OL814554 | OM401676 | ||

| Spo. trimorphus | CFCC 55171 = ROC 112 | Rosa xanthina | branches | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655798 | OK560389 | OL742173 | OL814555 | OM401677 | |

| ROC 113 | Rosa xanthina | branches | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655799 | OK560390 | OL742174 | OL814556 | OM401678 | ||

| ROC 114 | Rosa xanthina | branches | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655800 | OK560391 | OL742175 | OL814557 | OM401679 | ||

| ROC 115 | Rosa xanthina | branches | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655801 | OK560392 | OL742176 | OL814558 | OM401680 | ||

| ROC 116 | Rosa xanthina | branches | Lanzhou, Gansu | OK655802 | OK560393 | OL742177 | OL814559 | OM401681 | ||

1 Newly described taxa and deposited sequences are in bold.

2 T: ex-type.

Table 3.

Isolates from previous studies used in the phylogenetic analyses in the current study.

| Species | Strain number1 | Status2 | Country | Substrate | GenBank accession no. | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | RPB2 | TEF | TUB | ||||||

| Allelochaeta acuta | CPC 16629 | Australia | Eucalyptus dives | MH554086 | MH554297 | MH555000 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) | |

| All. elegans | CBS 187.81 | ET | Australia | Melaleuca lanceolata | MH554014 | MH554234 | MH554927 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) |

| All. falcata | CPC 13580 | Australia | Eucalyptus alligatrix | MH554073 | MH554284 | MH554985 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) | |

| CBS 131117 | ET | Australia | Eucalyptus alligatrix | MH553999 | MH554217 | MH554907 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) | |

| All. fusispora | CPC 17616 | Australia | Eucalyptus sp. | MH554094 | MH554304 | MH555008 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) | |

| CBS 810.73 | IT | Australia | Eucalyptus polyanthemos | MH554067 | MH554279 | MH554980 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) | |

| All. kriegeriana | CBS 188.81 | Australia | Callistemon sieberi | MH554015 | MH554235 | MH554928 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) | |

| All. neoacuta | CBS 115131 | T | South Africa | Eucalyptus smithii | JN871200 | JN871209 | MH554998 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) |

| CBS 110733 | South Africa | Eucalyptus smithii | JN871201 | JN871210 | MH554999 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) | ||

| All. neodilophospora | CPC 17161 | T | Australia | Callistemon pinifolius | MH554090 | MH554300 | MH555004 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) |

| All. neoorbicularis | CPC 13581 | Australia | Eucalyptus regnans | MH554074 | MH554285 | MH554986 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) | |

| All. obliquae | CPC 20191 | T | Australia | Eucalyptus obliqua | MH554105 | MH554315 | MH555018 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) |

| All. orbicularis | CBS 131118 | ET | Australia | Corymbia henryi | MH554000 | MH554218 | MH554908 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) |

| All. paraelegans | CBS 150.71 | T | Australia | Melaleuca ericifolia | MH554007 | MH554228 | MH554923 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) |

| All. pseudowalkeri | CPC 17043 | T | Australia | Eucalyptus sp. | MH554089 | MH554299 | MH555003 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) |

| All. sparsifoliae | CPC 14529 | Australia | Eucalyptus sparsifolia | MH554083 | MH554294 | MH554995 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) | |

| CPC 14502 | T | Australia | Eucalyptus sparsifolia | MH554082 | MH554293 | MH554994 | – | – | Crous et al. (2018) | |

| Bartalinia bella | CBS 125525 | South Africa | Maytenus abbottii | GU291796 | MH554214 | MH554904 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| CBS 464.61 | T | Brazil | Air | MH554051 | MH554264 | MH554964 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Bar. pini | CBS 143891 | T | Uganda | Pinus patula | MH554125 | MH554330 | MH555033 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| CBS 144141 | USA | Acacia koa | MH554170 | MH554364 | MH555067 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Bar. robillardoides | CBS 122705 | ET | Italy | Leptoglossus occidentalis | LT853104 | KJ710438 | LT853152 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| CBS 122615 | South Africa | Cupressus lusitanica | MH553989 | MH554207 | MH554897 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Beltrania pseudorhombica | CPC 23656 | China | Pinus tabulaeformis | MH554124 | KJ869215 | MH555032 | – | – | Crous et al. (2014a), | |

| Liu et al. (2019) | ||||||||||

| Bel. rhombica | CBS 123.58 | T | Mozambique | Sand near mangrove swamp | MH553990 | MH554209 | MH554899 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Broomella vitalbae | HPC 1154 | – | – | MH554173 | MH554367 | – | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| MFLUCC 13-0798 | ET | Italy | Clematis vitalba | NR 153610 | KP757749 | – | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Ciliochorella phanericola | MFLUCC 12-0310 | Thailand | Dead leaves | KF827444 | KF827445 | KF827479 | – | – | Hyde et al. (2016) | |

| MFLUCC 14-0984 | T | Thailand | Phanera purpurea | KX789680 | KX789681 | – | – | – | Hyde et al. (2016) | |

| Clypeosphaeria uniseptata | CBS 114967 | Hong Kong, China | Wood | MH553979 | MH554197 | MH554878 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Diploceras hypericinum | CBS 109058 | New Zealand | Hypericum sp. | MH553955 | MH554178 | MH554852 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| CBS 492.97 | Netherlands | Hypericum perforatum | MH554054 | MH554267 | MH554967 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| CBS 197.36 | Switzerland | Hypericum sp. | MH554017 | MH554237 | MH554930 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| CBS 143885 | ET | Netherlands | Hypericum perforatum | MH554108 | MH554316 | MH555019 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Disaeta arbuti | CBS 143903 | Australia | Acacia pycnantha | MH554148 | MH554346 | MH555050 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Discosia artocreas | CBS 124848 | ET | Germany | Fagus sylvatica | MH553994 | MH554213 | MH554903 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Dis. brasiliensis | NTCL095 | Thailand | Dead leaf | KF827433 | KF827437 | KF827474 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| NTCL097-2 | Thailand | Dead leaf | KF827434 | KF827438 | KF827475 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| NTCL094-2 | Thailand | Dead leaf | KF827432 | KF827436 | KF827473 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Discosia sp. 6 | CBS 241.66 | South Africa | Acacia karroo | MH554022 | MH554244 | MH554933 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Discosia sp. 7 | CBS 684.70 | Netherlands | Aesculus hippocastanu | MH554064 | MH554277 | MH554978 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Distononappendiculata banksiae | CPC 17658 | Australia | Banksia marginata | MH554097 | MH554307 | MH555011 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| CBS 131308 | T | Australia | Banksia marginata | JQ044422 | JQ044442 | MH554909 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| CPC 20185 | Australia | Banksia marginata | MH554104 | MH554314 | MH555017 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| CBS 143906 | Australia | Banksia marginata | MH554158 | MH554354 | MH555057 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Dist. casuarinae | CBS 143884 | T | Australia | Casuarina sp. | MH554093 | MH554303 | MH555007 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Dist. verruca ta | CBS 144032 | T | Australia | Banksia repens | MH554163 | MH554359 | MH555062 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Diversimediispora humicola | CBS 302.86 | T | USA | Soil | MH554028 | MH554247 | MH554941 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Heterotruncatella lutea | CBS 349.73 | IT | Australia | Acacia pycnantha | LT853099 | DQ414533 | LT853146 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Het. proteicola | CBS 123029 | South Africa | Protea acaulis | MH553993 | MH554212 | MH554902 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Het. restionacearum | CBS 119210 | South Africa | Ischyrolepis cf. gaudichaudiana | DQ278915 | DQ278929 | MH554892 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| CBS 118150 | South Africa | Restio filiformis | DQ278914 | MH554203 | MH554889 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Het. spadicea | CBS 118148 | South Africa | Rhodocoma capensis | DQ278913 | DQ278928 | MH554888 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| CBS 118144 | South Africa | Ischyrolepis sp. | DQ278921 | DQ278926 | MH554886 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Hyalotiella spartii | MFLUCC 13-0397 | T | Italy | Spartium junceum | KP757756 | KP757752 | – | – | – | Li et al. (2015) |

| Hyalotiella transvalensis | CBS 303.65 | T | South Africa | Soil | MH554029 | MH554248 | MH554942 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Hymenopleella austroafricana | CBS 143886 | T | South Africa | Gleditsia triacanthos | MH554115 | MH554320 | MH555023 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| CBS 144027 | Zambia | Combretum hereroense | MH554119 | MH554324 | MH555027 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| CBS 144026 | South Africa | Bridelia mollis | MH554117 | MH554322 | MH555025 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Hym. endophytica | EMLAS5-1 | T | Korea | Abies firma | KX216520 | KX216518 | – | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Hym. hippophaëicola | CBS 113687 | Sweden | Hippophae rhamnoides | MH553969 | MH554188 | MH554863 | – | – | Jaklitsch et al. (2016) | |

| CBS 140410 | ET | Austria | Hippophae rhamnoides | KT949901 | MH554224 | MH554919 | – | – | Jaklitsch et al. (2016) | |

| Hym. lakefuxianensis | HKUCC 7303 | T | China | Submerged wood | – | AF452047 | – | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Hym. polyseptata | CBS 143887 | T | South Africa | Combretum sp. | MH554116 | MH554321 | MH555024 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Hym. subcylindrica | CBS 164.77 | India | Cocos nucifera | MH554009 | MH554230 | MH554925 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| CBS 647.74 | T | India | Gypsophilla seeds | MH554062 | MH554275 | MH554976 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Immersidiscosia eucalypti | MAFF 242781 | Japan | Unknown dead leaves | AB594793 | AB593725 | – | – | – | Tanaka et al. (2011) | |

| NBRC 104197 | Japan | Ardisia japonica | AB594792 | AB593724 | – | – | – | Tanaka et al. (2011) | ||

| Lepteutypa fuckelii | CBS 140409 | NT | Belgium | Tilia cordata | NR 154123 | KT949902 | MH554918 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Lep. sambuci | CBS 131707 | T | UK | Sambucus nigra | NR 154124 | MH554219 | MH554911 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Microdochium lycopodinum | CBS 125585 | T | Austria | Lycopodium annotinum | KP859016 | KP858952 | KP859125 | – | – | Hernandez-Restrepo et al. (2016), |

| Liu et al. (2019) | ||||||||||

| Mic. phragmitis | CBS 285.71 | ET | Poland | Puccinia teleutosorus | KP859013 | KP858949 | KP859122 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Mic. seminicola | CBS 139951 | T | Switzerland | Maize kernels | NR 155375 | KP858974 | KP859147 | – | – | Hernandez-Restrepo et al. (2016), |

| Liu et al. (2019) | ||||||||||

| Monochaetia camelliae | PSH2000I-151 | China | Camellia hongkongensis | AY682948 | – | – | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| PSH2000I-146 | China | Camellia pitardii | AY682947 | – | – | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Μ. castaneae | CFCC 54354 = SM9-1 | T | China | Castanea mollissima | MW166222 | – | – | – | – | Jiang et al. (2021) |

| SM9-2 | China | Castanea mollissima | MW166223 | – | – | – | – | Jiang et al. (2021) | ||

| Μ. dimorphospora | NBRC 9980 | Japan | Castanea pubinervis | LC146750 | – | – | – | – | De Silva et al. (2018) | |

| NNIBRFG396 | Korea | Fresh water | MT271967 | – | – | – | – | De Silva et al. (2018) | ||

| Μ. ilicis | CBS 101009 | Japan | Air | MH553953 | MH554176 | MH554849 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| KUMCC 15-0520 | T | China | llex sp. | KX984153 | – | – | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Μ. junipericola | CBS:143391 | Germany | Juniperus communis | MH107900 | – | – | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Μ. kansensis | ZJLQ468 | China | Pseudotaxus chienii | KC345692 | – | – | – | – | De Silva et al. (2018) | |

| PSHI2004Endo1030 | China | Cyclobalaopsis sp. | DQ534044 | – | – | – | – | De Silva et al. (2018) | ||

| PSHI2004Endo1031 | China | Quercus aliena | DQ534045 | – | – | – | – | De Silva et al. (2018) | ||

| Μ. mochaeta | CBS 315.54 | England | Quercus sp. | MH554030 | MH554249 | MH554943 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| CBS 658.95 | Netherlands | Quercus robur | MH554063 | MH554276 | MH554977 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| CBS 115004 | Netherlands | Quercus robur | AY853243 | MH554198 | MH554879 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| CBS 546.80 | Netherlands | Culture contaminant | MH554056 | MH554270 | MH554969 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| CBS 199.82 | ET | Italy | Quercus pubescens | MH554018 | MH554238 | MH554931 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| M18 | Italy | Unknown plant | JX262802 | – | – | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Μ. quercus | CBS 144034 = CPC 29514 | T | Mexico | Quercus eduardi | MH554171 | MH554365 | MH555068 | – | – | De Silva et al. (2018) |

| CBS 144034 = CPC 29515 | Mexico | Quercus eduardi | NR_161110 | – | – | – | – | De Silva et al. (2018) | ||

| Μ. schimae | SAUCC212201 | T | China | Schima superba | MZ577565 | – | – | OK104874 | OK104867 | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| SAUCC212202 | China | Schima superba | MZ577566 | – | – | OK104875 | OK104868 | Zhang et al. (2022) | ||

| SAUCC212203 | China | Schima superba | MZ577567 | – | – | OK104876 | OK104869 | Zhang et al. (2022) | ||

| Μ. sinensis | HKAS 10065 | China | Quercus sp. | NR_161064 | – | – | – | – | De Silva et al. (2019) | |

| KUMCC 15-0517 | China | Quercus sp. | MH 115996 | – | – | – | – | De Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| Morinia acaciae | CBS 100230 | New Zealand | Prunus salicina cv. ‘Omega’ | MH553950 | MH554174 | MH554847 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| CBS 137994 | T | France | Acacia melanoxylon | MH554002 | MH554221 | MH554914 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | |

| Mor. crini | CBS 143888 | T | South Africa | Crinum bulbispermum | MH554118 | MH554323 | MH555026 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Mor. longiappendiculata | CBS 117603 | T | Spain | Calluna vulgaris | AY929324 | MH554202 | MH554885 | – | – | Collado et al. (2006), |

| Liu et al. (2019) | ||||||||||

| Mor. pestalozzioides | F090354 | ET | Spain | Sedum sediforme | AY929325 | – | – | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Neopestalotiopsis acrostichi | MFLUCC 17-1754 | T | Thailand | Acrostichum aureum | MK764272 | – | – | MK764316 | MK764338 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| MFLUCC 17-1755 | Thailand | Acrostichum aureum | MK764273 | – | – | MK764317 | MK764339 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) | ||

| N. alpapicalis | MFLUCC 17-2544 | T | Thailand | Rhizophora mucronata | MK357772 | – | – | MK463547 | MK463545 | Kumar et al. (2019) |

| MFLUCC 17-2545 | Thailand | Rhizophora apiculata | MK357773 | – | – | MK463548 | MK463546 | Kumar et al. (2019) | ||

| N. aotearoa | CBS 367.54 | T | New Zealand | Canvas | KM 199369 | – | – | KM 199526 | KM 199454 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. asiatica | MFLUCC 12-0286 | T | China | Leaves | JX398983 | – | – | JX399049 | JX399018 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. australis | CBS 114159 | T | Australia | Telopea sp. | KM 199348 | – | – | KM 199537 | KM 199432 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. brachiata | MFLUCC 17-1555 | T | Thailand | Rhizophora apiculata | MK764274 | – | – | MK764318 | MK764340 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| N. brasiliensis | COAD 2166 | T | Brazil | Psidium guajava | MG686469 | – | – | MG692402 | MG692400 | Bezerra et al. (2018) |

| N. camelliae-oleiferae | CSUFTCC81 | T | China | Camellia oleifera | OK493585 | – | – | OK507955 | OK562360 | Li etal. (2021) |

| N. cavernicola | KUMCC 20-0269 | T | China | Cave rock surface | MW545802 | – | – | MW550735 | MW557596 | Liu et al. (2021) |

| N. chiangmaiensis | MFLUCC 18-0113 | Thailand | Dead leaves | – | – | – | MH388404 | MH412725 | Tibpromma et al. (2018) | |

| N. chrysea | MFLUCC 12-0261 | T | China | Pandanus sp. | JX398985 | – | – | JX399051 | JX399020 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. clavispora | MFLUCC 12-0281 | T | China | Magnolia sp. | JX398979 | – | – | JX399045 | JX399014 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. cocoes | MFLUCC 15-0152 | Thailand | Cocos nucifera | KX789687 | – | – | KX789689 | – | Hyde et al. (2016) | |

| N. coffeae-arabicae | HGUP4019 | T | China | Coffea arabica | KF412649 | – | – | KF412646 | KF412643 | Song et al. (2013) |

| N. cubana | CBS 600.96 | T | Cuba | Leaf litter | KM 199347 | KM116253 | MH554973 | KM 199521 | KM 199438 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. dendrobii | MFLUCC 14-0106 | Thailand | Dendrobium cariniferum | MK993571 | – | – | MK975829 | MK975835 | Ma et al. (2019) | |

| N. drenthii | BRIP 72264a | T | Australia | Macadamia integrifolia | MZ303787 | – | – | MZ344172 | MZ312680 | Prasannath et al. (2021) |

| N. egyptiaca | CBS 140162 | T | Egypt | Mangifera indica | KP943747 | – | – | KP943748 | KP943746 | Crous et al. (2015b) |

| N. ellipsospora | CBS 115113 | T | China | Dead plant material | KM 199343 | – | – | KM 199544 | KM 199450 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| MFLUCC 12-0283 | China | Dead plant material | JX398980 | – | – | JX399047 | JX399016 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | ||

| N. eucalypticola | CBS 264.37 | T | – | Eucalyptus globulus | KM 199376 | KM116256 | MH554935 | KM199551 | KM199431 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. eucalyptorum | CBS 147684 | T | Portugal | Eucalyptus globulus | MW794108 | – | – | MW805397 | MW802841 | Diogo et al. (2021) |

| N. foedans | CGMCC 3.9123 | T | China | Mangrove plant | JX398987 | – | – | JX399053 | JX399022 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. formicarum | CBS 362.72 | T | Cuba | Plant debris | MH860500 | – | – | KM199517 | KM 199455 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. guajavae | FMBCC 11.1 | T | Pakistan | Psidium guajava | MF783085 | – | – | MH460868 | MH460871 | Ul Haq et al. (2021) |

| N. guajavicola | FMBCC 11.4 | T | Pakistan | Psidium guajava | MH209245 | – | – | MH460870 | MH460873 | Ul Haq et al. (2021) |

| N. hadrolaeliae | COAD 2637 | T | Brazil | Hadrolaelia jongheana | MK454709 | – | – | MK465122 | MK465120 | Freitas et al. (2019) |

| N. haikouensis | SAUCC212271 | T | China | Ilex chinensis | OK087294 | – | – | OK104877 | OK104870 | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| SAUCC212272 | China | Ilex chinensis | OK087295 | – | – | OK104878 | OK104871 | Zhang et al. (2022) | ||

| N. hispanica | CBS 147686 | T | Portugal | Eucalyptus globulus | MW794107 | – | – | MW805399 | MW802840 | Diogo et al. (2021) |

| N. honoluluana | CBS 114495 | T | USA | Telopea sp. | KM 199364 | – | – | KM 199548 | KM199461 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. hydeana | MFLUCC 20-0132 | T | Thailand | Artocarpus heterophyllus | MW266069 | – | – | MW251129 | MW251119 | Huanluek et al. (2021) |

| N. iberica | CBS 147688 | T | Portugal | Eucalyptus globulus | MW794111 | – | – | MW805402 | MW802844 | Diogo et al. (2021) |

| N. iraniensis | CBS 137768 | Iran | Fragaria x ananassa | KM074045 | – | – | KM074051 | KM074056 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) | |

| N. javaensis | CBS 257.31 | T | Indonesia | Cocos nucifera | KM 199357 | – | – | KM 199543 | KM 199437 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. longiappendiculata | CBS 147690 | T | Portugal | Eucalyptus globulus | MW794112 | – | – | MW805404 | MW802845 | Diogo et al. (2021) |

| N. lusitanica | CBS 147692 | T | Portugal | Eucalyptus globulus | MW794110 | – | – | MW805406 | MW802843 | Diogo et al. (2021) |

| N. macadamiae | BRIP 63737c | T | New South Wales | Macadamia integrifolia | KX186604 | – | – | KX186627 | KX186654 | Akinsanmi et al. (2017) |

| N. maddoxii | BRIP 72266a | T | Australia | Macadamia integrifolia | MZ303782 | – | – | MZ344167 | MZ312675 | Prasannath et al. (2021) |

| N. magna | MFLUCC 12-0652 | T | France | Pteridium sp. | KF582795 | – | – | KF582791 | KF582793 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. mesopotamica | CBS 336.86 | T | Iraq | Pinus brutia | KM 199362 | KM116271 | MH554944 | KM 199555 | KM199441 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. musae | MFLU 16-1279 | T | Thailand | Musa sp. | KX789683 | – | – | KX789685 | KX789686 | Hyde et al. (2016) |

| N. natalensis | CBS 138.41 | T | South Africa | Acacia mollissima | KM199377 | – | – | KM 199552 | KM 199466 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. nebuloides | BRIP 66617 | T | Australia | Sporobolus elongatus | MK966338 | – | – | MK977633 | MK977632 | Crous et al. (2020) |

| N. olumideae | BRIP 72273a | T | Australia | Macadamia integrifolia | MZ303790 | – | – | MZ344175 | MZ312683 | Prasannath et al. (2021) |

| N. palmarum | PSHI2004Endo458 | Cuba | Zalacca wallichiana | DQ813426 | – | – | – | DQ787836 | Liu et al. (2010) | |

| PSHI2004Endo454 | Cuba | Roystonea regia | DQ813427 | – | – | – | DQ787837 | Liu et al. (2010) | ||

| N. pandanicola | KUMCC 17-0175 | – | Pandanus sp. | – | – | – | MH388389 | MH412720 | Tibpromma et al. (2018) | |

| N. pemambucana | URM 7148-01 | T | Brazil | Vismia guianensis | KJ792466 | – | – | KU306739 | – | Silvério et al. (2016) |

| N. perukae | FMBCC 11.3 | T | Pakistan | Psidium guajava | MH209077 | – | – | MH523647 | MH460876 | Ul Haq et al. (2021) |

| N. petila | MFLUCC 17-1738 | T | Thailand | Rhizophora mucronata | MK764275 | – | – | MK764319 | MK764341 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| MFLUCC 17-1737 | Thailand | Rhizophora mucronata | MK764276 | – | – | MK764320 | MK764342 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) | ||

| N. phangngaensis | MFLUCC 18-0119 | – | Pandanus sp. | MH388354 | – | – | MH388390 | MH412721 | Tibpromma et al. (2018) | |

| N. piceana | CBS 394.48 | T | UK | Picea sp. | KM 199368 | – | – | KM199527 | KM 199453 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. protearum | CBS 114178 | T | Zimbabwe | Leucospermum cuneiforme | JN712498 | JN712564 | MH554873 | LT853201 | KM 199463 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. psidii | FMBCC 11.2 | T | Pakistan | Psidium guajava | MF783082 | – | – | MH460874 | MH477870 | Ul Haq et al. (2021) |

| N. rhapidis | GUCC 21501 | T | China | Rhododendron simsii | MW931620 | – | – | MW980442 | MW980441 | Yang et al. (2021) |

| N. rhizophorae | MFLUCC 17-1551 | T | Thailand | Rhizophora mucronata | MK764277 | – | – | MK764321 | MK764343 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| MFLUCC 17-1550 | Thailand | Rhizophora mucronata | MK764278 | – | – | MK764322 | MK764344 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) | ||

| N. rhododendri | GUCC 21504 | T | China | Rhododendron simsii | MW979577 | – | – | MW980444 | MW980443 | Yang et al. (2021) |

| N. rosae | CBS 101057 | T | New Zealand | Rosa sp. | KM 199359 | KM 116245 | MH554850 | KM 199524 | KM 199430 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| CBS 124745 | USA | Paeonia suffruticosa | KM 199360 | – | – | KM 199524 | KM 199430 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | ||

| CRM-FRC | Mexico | Fragaria x ananassa | MN385718 | – | – | MN268532 | MN268529 | Rebollar-Alviter et al. (2020) | ||

| AC50 | Italy | Persea americana | ON117810 | – | – | ON107276 | ON209165 | Alberto et al. (2022) | ||

| N. rosicola | CFCC 51992 | T | China | Rosa chinensis | KY885239 | – | – | KY885243 | KY885245 | Jiang et al. (2018) |

| CFCC 51993 | China | Rosa chinensis | KY885240 | – | – | KY885244 | KY885246 | Jiang et al. (2018) | ||

| N. samaragenensis | MFLUCC 12-0233 | T | Thailand | Syzygium samarangense | KM 199365 | – | – | KM 199556 | KM 199447 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| N. saprophytica | MFLUCC 12-0282 | T | China | Magnolia sp. | KY606286 | – | – | JX399048 | JX399017 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. scalabiensis | CAA1029 | T | Portugal | Vaccinium corymbosum | MW969748 | MW959100 | MW934611 | Santos et al. (2022) | ||

| N. sichuanensis | CFCC 54338 = SM15-1 | T | China | Castanea mollissima | MW166231 | – | – | MW199750 | MW218524 | Jiang et al. (2021) |

| SM15-1C | China | Castanea mollissima | MW166232 | – | – | MW199751 | MW218525 | Jiang et al. (2021) | ||

| N. siciliana | AC46 | Italy | Persea americana | ON117813 | – | – | ON107273 | ON209162 | Alberto et al. (2022) | |

| AC48 | Italy | Persea americana | ON117812 | – | – | ON107274 | ON209163 | Alberto et al. (2022) | ||

| AC49 | Italy | Persea americana | ON117811 | – | – | ON107275 | ON209164 | Alberto et al. (2022) | ||

| N. sonneratae | MFLUCC 17-1744 | T | Thailand | Sonneronata alba | MK764279 | – | – | MK764323 | MK764345 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| MFLUCC 17-1745 | Thailand | Sonneronata alba | MK764280 | – | – | MK764324 | MK764346 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) | ||

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.1 | VRes4 | Colombia | Scab disease of Guava | KR493566 | – | – | KR493638 | – | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.2 | BPca2 | Colombia | Scab disease of Guava | KR493559 | – | – | KR493627 | KR493666 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.3 | VrleP | Colombia | Scab disease of Guava | KR493520 | – | – | KR493660 | KR493719 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.4 | VTman4 | Colombia | Scab disease of Guava | KR493554 | – | – | KR493611 | KR493724 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.5 | BVayr1 | Colombia | Scab disease of Guava | KR493545 | – | – | KR493629 | KR493739 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.6 | BRIP 63740a | Australia | Dry flower | KX186617 | – | – | KX186628 | KX186656 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.7 | BRIP 63745a | Australia | Dry flower | KX186614 | – | – | KX186633 | KX186660 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.8 | CBS 119.75 | India | Achras sapota | KM 199356 | – | – | KM199531 | KM 199439 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.9 | CM M1363 | Brazil | Opuntia stricta | KY549599 | – | – | KY549596 | KY549634 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.10 | LC6489 | China | Camellia sp. | KX895020 | – | – | KX895239 | KX895353 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.11 | MFLUCC 12-0614 | Midi-pyrénées | Unidentified host | KX816919 | – | – | KX816889 | KX816947 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.12 | MMf0011 | Japan | Lilium speciosum | LC184188 | – | – | LC184190 | LC184189 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.13 | SC2A3 | China | Tea plant | KU252210 | – | – | KU252390 | KU252477 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.14 | CBS 164.42 | France | Sand dune | KM 199367 | – | – | KM 199520 | KM 199434 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.15 | CBS 266.80 | India | Vitis vinifera | KM 199352 | – | – | KM 199532 | – | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.16 | CBS 360.61 | Guinea | Cinchona sp. | KM 199346 | – | – | KM 199522 | KM 199440 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| Neopestalotiopsis sp.17 | CBS 361.61 | Netherlands | Cissus sp. | KM 199355 | – | – | KM 199549 | KM 199460 | Kumar et al. (2019) | |

| N. steyaertii | IMI 192475 | Australia | Eucalyptus viminalis | KF582796 | – | – | KF582792 | KF582794 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| N. surinamensis | CBS 450.74 | T | Suriname | Soil | KM 199351 | KM 116258 | MH554962 | KM199518 | KM 199465 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| N. thailandica | MFLUCC 17-1730 | T | Thailand | Rhizophora mucronata | MK764281 | – | – | MK764325 | MK764347 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| N. umbrinospora | MFLUCC 12-0285 | T | China | Dead leaves | JX398984 | – | – | JX399050 | JX399019 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| N. vaccinii | CAA1059 | T | Portugal | Vaccinium corymbosum | MW969747 | – | – | MW959099 | MW934610 | Santos et al. (2022) |

| N. vacciniicola | CAA1055 | T | Portugal | Vaccinium corymbosum | MW969751 | – | – | MW959103 | MW934614 | Santos et al. (2022) |

| N. versicolor | CBS 303.49 | China | Myrica rubra | MH856535 | – | – | – | – | Vu et al. (2019) | |

| N. vheenae | BRIP 72293a | T | Australia | Macadamia integrifolia | MZ303792 | – | – | MZ344177 | MZ312685 | Prasannath et al. (2021) |

| N. vitis | MFLUCC 15-1265 | China | Vitis vinifera | KU140694 | – | – | KU140676 | KU140685 | Jayawardena et al. (2016) | |

| N. zakeelii | BRIP 72282a | T | Australia | Macadamia integrifolia | MZ303789 | – | – | MZ344174 | MZ312682 | Prasannath et al. (2021) |

| N. zimbabwana | CBS H-21769 | Zimbabwe | Leucospermum cunciforme | – | JX556249 | MH554855 | KM 199545 | KM 199456 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| Nonappendiculata quercina | CBS 116061 | T | Italy | Quercus suber | MH553982 | MH554199 | MH554882 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| CBS 270.82 | Italy | Quercus pubescens | MH554025 | MH554246 | MH554937 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) | ||

| Parabartalinia lateralis | CBS 399.71 | T | South Africa | Acacia karroo | MH554043 | MH554256 | MH554954 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Pestalotiopsis abietis | CFCC 53011 | T | China | Abies fargesii | MK397013 | – | – | MK622277 | MK622280 | Gu et al. (2021) |

| CFCC 53012 | China | Abies fargesii | MK397014 | – | – | MK622278 | MK622281 | Gu et al. (2021) | ||

| CFCC 53013 | China | Abies fargesii | MK397015 | – | – | MK622279 | MK622282 | Gu et al. (2021) | ||

| Pes. adusta | ICMP 6088 | T | Fiji | Refrigerator door PVC gasket | JX399006 | – | – | JX399070 | JX399037 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| CBS 263.33 | Netherlands | Rhododendron ponticum | KM199316 | – | – | KM 199489 | KM199414 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) | ||

| Pes. aggestorum | LC6301 | T | China | Camellia sinensis | KX895015 | – | – | KX895234 | KX895348 | Liu et al. (2017) |

| Pes. anacardiacearum | IFRDCC 2397 | T | China | Mangifera indica | KC247154 | – | – | KC247156 | KC247155 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2013b) |

| Pes. arceuthobii | CBS 433.65 | USA | Arceuthobium campylopodum | MH554046 | – | – | MH554481 | MH554722 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| CBS 434.65 | T | USA | Arceuthobium campylopodum | KM 199341 | – | – | KM199516 | KM199427 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| Pes. arengae | CBS 331.92 | T | Singapore | Arenga undulatifolia | KM 199340 | – | – | KM199515 | KM 199426 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. australasiae | CBS 114126 | T | New Zealand | Knightia sp. | KM 199297 | KM116218 | MH554867 | KM 199499 | KM 199409 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| CBS 114141 | Australia | Protea cv. ’Pink Ice’ | KM 199298 | – | – | KM199501 | KM199410 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | ||

| Pes. australis | CBS 114193 | T | Australia | Grevillea sp. | KM 199332 | KM116197 | MH554875 | KM 199475 | KM 199383 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| CBS 119350 | South Africa | Brabejum stellatifolium | KM 199333 | – | – | KM 199476 | KM 199384 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | ||

| MEAN 1096 = CPC 36750 = | Portugal | Pinus pinea | MT374679 | – | – | MT374692 | MT374704 | Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| CBS 146843 | ||||||||||

| MEAN 1109 | Portugal | Pinus pinea | MT374683 | – | – | – | MT374708 | Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| MEAN 1110 | Portugal | Pinus pinea | MT374684 | – | – | MT374696 | MT374709 | Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| MEAN 1111 | Portugal | Pinus pinea | MT374685 | – | – | MT374697 | MT374710 | Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| MEAN 1112 | Portugal | Pinus pinea | MT374686 | – | – | MT374698 | MT374711 | Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| Pes. biciliata | CBS 124463 | T | Slovakia | Platanus x hispanica | KM 199308 | – | – | KM 199505 | KM 199399 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| CBS 236.38 | Italy | Paeonia sp. | KM 199309 | – | – | KM 199506 | KM199401 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | ||

| MEAN 1168 | Portugal | Pinus pinea | MT374690 | – | – | MT374702 | MT374715 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | ||

| Pes. brachiata | LC2988 | T | China | Camellia sp. | KX894933 | – | – | KX895150 | KX895265 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. brassicae | CBS 170.26 | T | New Zealand | Brassica napus | KM 199379 | – | – | KM 199558 | – | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. camelliae | CBS 443.62 | Turkey | Camellia sinensis | KM 199336 | – | – | KM199512 | KM 199424 | Zhang et al. (2012b) | |

| MFLUCC 12-0277 | T | China | Camellia japonica | JX399010 | – | – | JX399074 | JX399041 | Zhang et al. (2012b) | |

| Pes. camelliae-oleiferae | CSUFTCC08 | T | China | Camellia oleifera | OK493593 | OK507963 | OK562368 | Li et al. (2021) | ||

| CSUFTCC09 | China | Camellia oleifera | OK493594 | OK507964 | OK562369 | Li et al. (2021) | ||||

| CSUFTCC10 | China | Camellia oleifera | OK493595 | OK507965 | OK562370 | Li et al. (2021) | ||||

| Pes. chamaeropis | CBS 113607 | – | – | KM 199325 | – | – | KM 199472 | KM 199390 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| CBS 186.71 | T | Italy | Chamaerops humilis | KM 199326 | – | – | KM 199473 | KM199391 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| Pes. chiaroscuro | BRIP 72970 | T | Australia | Sporobolus natalensis | OK422510 | – | – | – | – | Crous et al. (2022) |

| Pes. clavata | MFLUCC 12-0268 | T | China | Buxus sp. | JX398990 | – | – | JX399056 | JX399025 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2012) |

| Pes. colombiensis | CBS 118553 | T | Colombia | Eucalyptus eurograndis | KM 199307 | – | – | KM 199488 | KM 199421 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. digitalis | ICMP 5434 | T | New Zealand | Digitalis purpurea | KP781879 | – | – | – | KP781883 | Liu et al. (2015) |

| Pes. diploclisiae | CBS 115587 | T | Hong Kong, China | Diploclisia glaucescens | KM 199320 | – | – | KM 199486 | KM199419 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. disseminata | CBS 118552 | New Zealand | Eucalyptus botryoides | MH553986 | – | – | MH554410 | MH554652 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| CBS 143904 | New Zealand | Persea americana | MH554152 | – | – | MH554587 | MH554825 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | ||

| MEAN 1165 | Portugal | Pinus pinea, blighted shoot | MT374687 | – | – | MT374699 | MT374712 | Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| MEAN 1166 | Portugal | Pinus pinea, blighted shoot | MT374688 | – | – | MT374700 | MT374713 | Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| Pes. distincta | LC3232 | T | China | Camellia sinensis | KX894961 | – | – | KX895178 | KX895293 | Silva et al. (2020) |

| LC8184 | China | Camellia sinensis | KY464138 | – | – | KY464148 | KY464158 | Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| Pes. diversiseta | MFLUCC 12-0287 | T | China | Rhododendron sp. | JX399009 | – | – | JX399073 | JX399040 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2012) |

| Pes. doitungensis | MFLUCC 14-0115 | T | Thailand | Dendrobium sp. | MK993574 | – | – | MK975832 | MK975837 | Ma et al. (2019) |

| Pes. dracaenicola | MFLUCC 18-0913 | T | Thailand | Dracaena sp. | MN962731 | – | – | MN962732 | MN962733 | Chaiwan et al. (2020) |

| Pes. dracontomelonis | MFLUCC 10-0149 | T | Thailand | Dracontomelon dao | KP781877 | – | – | KP781880 | – | Liu et al. (2015) |

| Pes. ericacearum | IFRDCC 2439 | T | China | Rhododendron delavayi | KC537807 | – | – | KC537814 | KC537821 | Zhang et al. (2013b) |

| Pes. etonensis | BRIP 66615 | T | Australia | Sporobolus jacquemontii | MK966339 | – | – | MK977635 | MK977634 | Crous et al. (2020) |

| Pes. formosana | NTUCC 17-009 | T | Taiwan,China | On dead grass | MH809381 | – | – | MH809389 | MH809385 | Ariyawansa & Hyde (2018) |

| Pes. furcata | MFLUCC 12-0054 | T | Thailand | Camellia sinensis | JQ683724 | – | – | JQ683740 | JQ683708 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2013a) |

| Pes. gaultheriae | IFRD 411-014 | T | China | Gaultheria forrestii | KC537805 | – | – | KC537812 | KC537819 | Zhang et al. (2013) |

| Pes. gibbosa | NOF3175 | T | Canada | Gaultheria shallon | LC311589 | – | – | LC311591 | LC311590 | Watanabe et al. (2018) |

| Pes. grevilleae | CBS 114127 | T | Australia | Grevillea sp. | KM 199300 | KM116212 | MH554868 | KM 199504 | KM 199407 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. hawaiiensis | CBS 114491 | T | USA | Leucospermum cv. ’Coral’ | KM 199339 | – | – | KM199514 | KM 199428 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. hispanica | CBS 115.391 | T | Spain | Protea cv. ’Susara’ | MH553981 | – | – | MH554399 | MH554640 | Liu etal. (2019) |

| Pes. hollandica | CBS 265.33 | T | Netherlands | Sciadopitys verticillata | KM 199328 | KM 116228 | MH554936 | KM199481 | KM 199388 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| MEAN 1091 = CPC 36745 = | Portugal | Pinus pinea, blighted shoot | MT374678 | – | – | MT374691 | MT374703 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | ||

| CBS 146839 | ||||||||||

| Pes. humicola | CBS 115450 | T | Hong Kong, China | Ilex cinerea | KM199319 | KM 116208 | MH554881 | KM 199487 | KM199418 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| CBS 336.97 | Papua New Guinea | Soil | KM 199317 | – | – | KM 199484 | KM 199420 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | ||

| Pes. hunanensis | CSUFTCC15 | T | China | Camellia oleifera | OK493599 | – | – | OK507969 | OK562374 | Li et al. (2021) |

| CSUFTCC18 | China | Camellia oleifera | OK493600 | – | – | OK507970 | OK562375 | Li et al. (2021) | ||

| CSUFTCC19 | China | Camellia oleifera | OK493601 | – | – | OK507971 | OK562376 | Li et al. (2021) | ||

| Pes. hydei | MFLUCC 20-0135 | T | Thailand | Litsea petiolata | NR_172003 | – | – | MW251113 | MW251112 | Huanluek et al. (2021) |

| Pes. inflexa | MFLUCC 12-0270 | T | China | Unidentified tree | JX399008 | – | – | JX399072 | JX399039 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2012) |

| Pes. intermedia | MFLUCC 12-0259 | T | China | Unidentified tree | JX398993 | – | – | JX399059 | JX399028 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2012) |

| Pes. italiana | MFLUCC 12-0657 | T | Italy | Cupressus glabra | KP781878 | – | – | KP781881 | KP781882 | Liu et al. (2015) |

| Pes. jesteri | CBS 109350 | T | Papua New Guinea | Fragraea bodenii | KM 199380 | – | – | KM 199554 | KM 199468 | Strobel et al. (2000) |

| Pes. jiangxiensis | LC4399 | T | China | Camellia sp. | KX895009 | – | – | KX895227 | KX895341 | Liu et al. (2017) |

| Pes. jinchanghens | LC6636 | T | China | Camellia sinensis | KX895028 | – | – | KX895247 | KX895361 | Liu et al. (2017) |

| Pes. kandelicola | NCYUCC 19-0355 | Taiwan,China | Kandelia candel | MT560722 | – | – | MT563101 | MT563099 | Hyde et al. (2020) | |

| NCYUCC 19-0354 | Taiwan,China | Kandelia candel | MT560723 | – | – | MT563102 | MT563100 | Hyde et al. (2020) | ||

| Pes. kenyana | CBS 442.67 | T | Kenya | Coffea sp. | KM 199302 | KM 116234 | MH554958 | KM 199502 | KM 199395 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. knightiae | CBS 114138 | T | New Zealand | Knightia sp. | KM199310 | KM116227 | MH554870 | KM 199497 | KM 199408 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. leucadendri | CBS 121417 | T | South Africa | Leucadendron sp. | MH553987 | – | – | MH554412 | MH554654 | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Pes. licualicola | HGUP 4057 | T | China | Licuala grandis | KC492509 | – | – | KC481684 | KC481683 | Geng et al. (2013) |

| Pes. linearis | MFLUCC 12-0271 | T | China | Trachelospermum sp. | JX398992 | – | – | JX399058 | JX399027 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2012) |

| Pes. longiappendiculata | LC3013 | T | China | Camellia sinensis | KX894939 | – | – | KX895156 | KX895271 | Liu et al. (2017) |

| Pes. lushanensis | LC4344 | T | China | Camellia sp. | KX895005 | – | – | KX895223 | KX895337 | Liu et al. (2017) |

| Pes. macadamiae | BRIP 63738b | T | Australia | Macadamia integrifolia | KX186588 | – | – | KX186621 | KX186680 | Akinsanmi et al. (2017) |

| Pes. malayana | CBS 102220 | T | Malaysia | Macaranga triloba | KM 199306 | – | – | KM 199482 | KM199411 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. monochaeta | CBS 144.97 | T | Netherlands | Quercus robur | KM 199327 | – | – | KM 199479 | KM 199386 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. nanjingensis | CSUFTCC16 | T | China | Camellia oleifera | OK493602 | – | – | OK507972 | OK562377 | Li et al. (2021) |

| CSUFTCC20 | China | Camellia oleifera | OK493603 | – | – | OK507973 | OK562378 | Li et al. (2021) | ||

| CSUFTCC04 | China | Camellia oleifera | OK493604 | – | – | OK507974 | OK562379 | Li et al. (2021) | ||

| Pes. nanningensis | CSUFTCC10 | T | China | Camellia oleifera | OK562371 | – | – | OK507966 | OK562371 | Li et al. (2021) |

| CSUFTCC11 | China | Camellia oleifera | OK562372 | – | – | OK507967 | OK562372 | Li et al. (2021) | ||

| CSUFTCC12 | China | Camellia oleifera | OK562373 | – | – | OK507968 | OK562373 | Li et al. (2021) | ||

| Pes. neolitseae | NTUCC 17-011 | T | Taiwan,China | Neolitsea villosa | MH809383 | – | – | MH809391 | MH809387 | Ariyawansa & Hyde (2018) |

| Pes. novae-hollandiae | CBS 130973 | T | Australia | Banksia grandis | KM 199337 | – | – | KM199511 | KM 199425 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. oryzae | CBS 353.69 | T | Denmark | Oryza sativa | KM 199299 | KM116221 | MH554947 | KM 199496 | KM 199398 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. pallidotheae | MAFF 240993 | T | Japan | Pieris japonica | NR111022 | – | – | LC311585 | LC311584 | Watanabe et al. (2010) |

| Pes. pandanicola | MFLUCC 16-0255 | T | Thailand | Pandanus sp. | MH388361 | – | – | MH388396 | MH412723 | Li etal. (2021) |

| Pes. papuana | CBS 331.96 | T | Papua New Guinea | Soil | KM 199321 | – | – | KM199491 | KM199413 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. parva | CBS 114972 | Hong Kong, China | Leaf | MH553980 | – | – | MH554397 | MH704625 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| CBS 278.35 | T | – | Leucothoe fontanesiana | KM199313 | KM 116205 | MH554939 | KM 199509 | KM 199405 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| Pes. photinicola | GZCC 16-0028 | T | China | Photinia serrulata | KY092404 | – | – | KY047662 | KY047663 | Chen etal. (2017) |

| Pes. pini | MEAN 1092 = CPC 36746 = | Portugal | Pinus pinea | MT374680 | – | – | MT374693 | MT374705 | Silva et al. (2020) | |

| CBS 146840 | ||||||||||

| MEAN 1094 = CPC 36748 = | T | Portugal | Pinus pinea | MT374681 | – | – | MT374694 | MT374706 | Silva et al. (2020) | |

| CBS 146841 | ||||||||||

| MEAN 1095 = CPC 36749 = | Portugal | Pinus pinea | MT374682 | – | – | MT374695 | MT374707 | Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| CBS 146842 | ||||||||||

| MEAN 1167 | Portugal | Pinus pinaster | MT374689 | – | – | MT374701 | MT374714 | Silva et al. (2020) | ||

| Pes. pinicola | KUMCC 19-0183 | T | China | Pinus armandii | MN412636 | – | – | MN417509 | MN417507 | Tibpromma et al. (2019) |

| Pes. portugallica | CBS 684.85 | New Zealand | Camellia japonica | MH554065 | – | – | MH554501 | MH554741 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| CBS 393.48 | T | Portugal | – | KM 199335 | KM 116233 | MH554951 | KM199510 | KM 199422 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| Pes. rhizophorae | MFLUCC 17-0416 | T | Thailand | Rhizophora apiculata | MK764283 | – | – | MK764327 | MK764349 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| Pes. rhododendri | IFRDCC 2399 | T | China | Rhododendron sinogrande | KC537804 | – | – | KC537811 | KC537818 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| CBS 144024 | Zimbabwe | Pinus sp. | MH554109 | – | – | MH554543 | MH554782 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) | ||

| Pes. rhodomyrtus | HGUP 4230 | T | China | Rhodomyrtus tomentosa | KF412648 | – | – | KF412645 | KF412642 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) |

| LC3413 | China | Camellia sinensis | KX894981 | – | – | KX895198 | KX895313 | Norphanphoun et al. (2019) | ||

| Pes. rosea | MFLUCC 12-0258 | T | China | Pinus sp. | JX399005 | – | – | JX399069 | JX399036 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2012) |

| Pes. scoparia | CBS 176.25 | T | – | Chamaecyparis sp. | KM 199330 | – | – | KM 199478 | KM 199393 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. sequoiae | MFLUCC 13-0399 | T | Italy | Sequoia sempervirens | KX572339 | – | – | – | – | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. shorea | MFLUCC 12-0314 | T | Thailand | Shorea obtusa | KJ503811 | – | – | KJ503817 | KJ503814 | Song et al. (2013) |

| Pestalotiopsis 7 FL 2019 | CBS 110326 | USA | Pinus sp. | MH553957 | – | – | MH554375 | MH554616 | Silva et al. (2020) | |

| Pestalotiopsis 7 FL 2019 | CBS 127.80 | Chile | Pinus radiata | MH553995 | – | – | MH554422 | MH554664 | Silva et al. (2020) | |

| Pes. spathulata | CBS 356.86 | T | Chile | Guevina avellana | KM 199338 | – | – | KM199513 | KM 199423 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. spathuliappendiculata | CBS 144035 | T | Australia | Phoenix canariensis | MH554172 | MH554366 | – | MH554607 | MH554845 | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Pes. telopeae | CBS 114137 | Australia | Protea cv. ’Pink Ice’ | KM 199301 | – | – | KM 199559 | KM 199469 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| CBS 114161 | T | Australia | Telopea sp. | KM 199296 | – | – | KM 199500 | KM 199403 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) | |

| Pes. terricola | CBS 141.69 | T | Pacific Islands | Soil | MH554004 | – | – | MH554438 | MH554680 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. thailandica | MFLUCC 17-1616 | T | Thailand | Rhizophora apiculata | MK764285 | – | – | MK764329 | MK764351 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pes. trachycarpicola | IFRDCC 2440 | T | China | Trachycarpus fortunei | JQ845947 | – | – | JQ845946 | JQ845945 | Zhang et al. (2012a) |

| Pes. unicolor | MFLUCC 12-0275 | China | Unidentified tree | JX398998 | – | – | JX399063 | JX399029 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2012) | |

| MFLUCC 12-0276 | T | China | Rhododendron sp. | JX398999 | – | – | – | JX399030 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2012) | |

| Pes. verruculosa | MFLUCC 12-0274 | T | China | Rhododendron sp. | JX398996 | – | – | JX399061 | – | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2012) |

| Pes. cf. verruculosa | CBS 365.54 | Netherlands | Chamaecyparis lawsoniana | MH554037 | – | – | MH554472 | MH554713 | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2012) | |

| Pes. yanglingensis | LC3412 | China | Camellia sinensis | KX894980 | – | – | KX895197 | KX895312 | Liu et al. (2017) | |

| LC4553 | T | China | Camellia sinensis | KX895012 | – | – | KX895231 | KX895345 | Liu et al. (2017) | |

| Pes. yunnanensis | HMAS 96359 | T | China | Podocarpus macrophyllus | AY373375 | – | – | – | – | Wei et al. (2013) |

| Phlogicylindrium eucalypti | CBS 120080 | T | Australia | Eucalyptus globulus | NR_132813 | DQ923534 | MH554893 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Phlogicylindrium eucalyptorum | CBS 120221 | T | Australia | Eucalyptus globus | EU040223 | MH554204 | MH554894 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Phlogicylindrium uniforme | CBS 131312 | T | Australia | Eucalyptus globus | JQ044426 | JQ044445 | MH554910 | – | – | Crous et al. (2011a) |

| Pseudopestalotiopsis cocos | CBS 272.29 | T | Indonesia | Cocos nucifera | KM 199378 | KM 116276 | MH554938 | – | – | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pse. elaeidis | CBS 413.62 | IT | Nigeria | Elaeis guineensis | MH554044 | MH554257 | MH554955 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

| Pse. indica | CBS 459.78 | T | India | Rosa sinensis | KM 199381 | MH554263 | MH554963 | – | – | Maharachchikumbura et al. (2014) |

| Pseudosarcostroma osyridicola | CBS 103.76 | T | France | Osyris alba | MH553954 | MH554177 | MH554851 | – | – | Liu et al. (2019) |

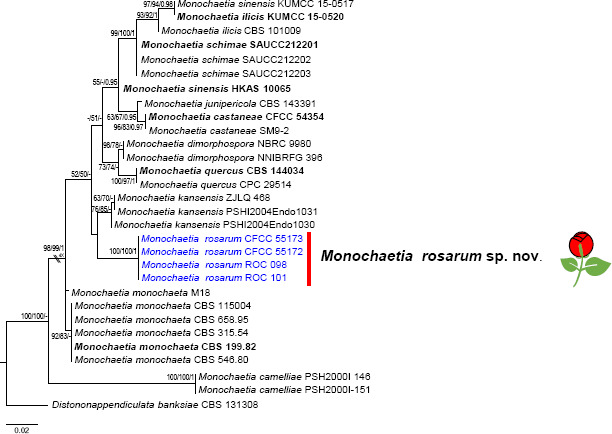

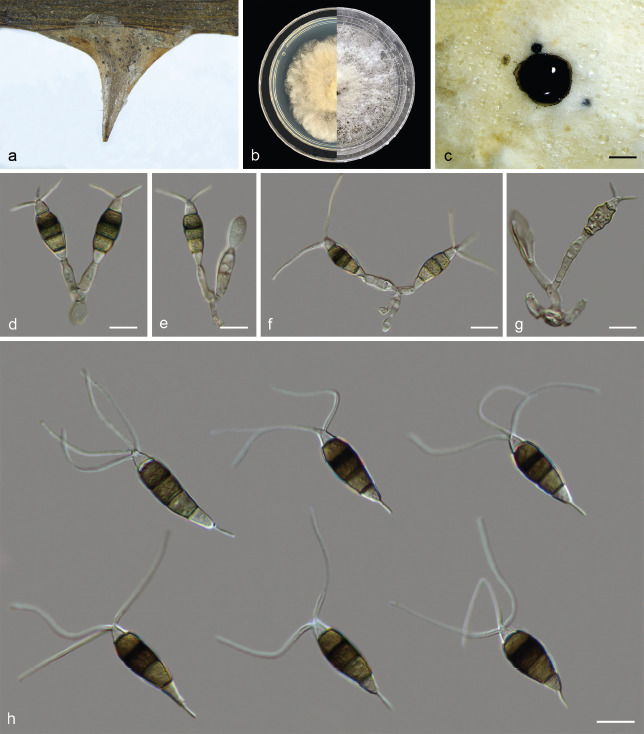

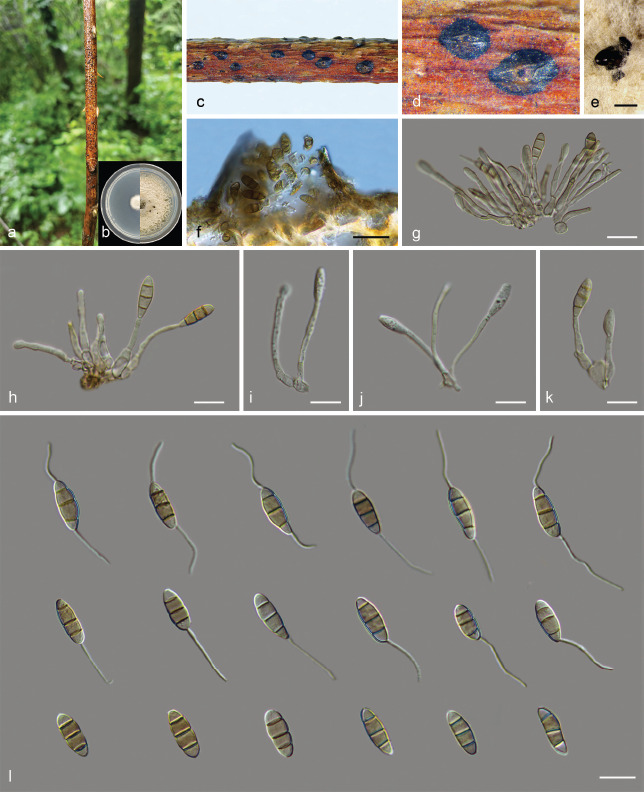

| Robillarda africana | CBS 122.75 | T | South Africa | – | KR873253 | KR873281 | MH554896 | – | – | Crous et al. (2015a) |