Summary

Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) represent a large percentage of overall nuclear protein content. The prevailing dogma is that IDRs engage in non-specific interactions because they are poorly constrained by evolutionary selection. Here, we demonstrate that condensate formation and heterotypic interactions are distinct and separable features of an IDR within the ARID1A/B subunits of the mSWI/SNF chromatin remodeler, cBAF, and establish distinct ‘sequence grammars’ underlying each contribution. Condensation is driven by uniformly distributed tyrosine residues, and partner interactions are mediated by non-random blocks rich in alanine, glycine, and glutamine residues. These features concentrate a specific cBAF protein-protein interaction network and are essential for chromatin localization and activity. Importantly, human disease-associated perturbations in ARID1B IDR sequence grammars disrupt cBAF function in cells. Together, these data identify IDR contributions to chromatin remodeling and explain how phase separation provides a mechanism through which both genomic localization and functional partner recruitment are achieved.

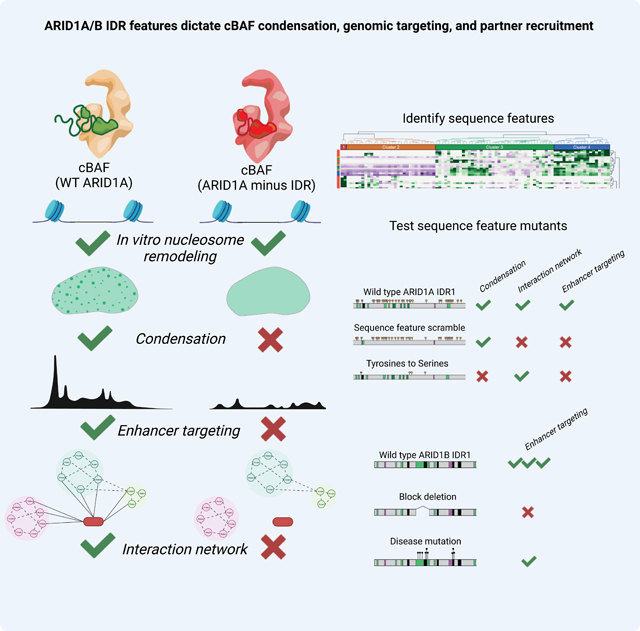

eTOC blurb

Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) together with the ARID DNA-binding domain of ARID1A/B subunits dictate cBAF chromatin remodeler complex condensate formation, chromatin localization, and protein-protein interactions, governed by specific IDR sequence grammars.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) comprise 37–50% of the human proteome1 and are especially enriched in nuclear proteins2. Rather than a singular structure, IDRs are defined by heterogeneous conformational ensembles3,4 which has led to the prevailing view that IDR-mediated interactions are less specific than those mediated by folded domains5. However, associations driven by specific IDRs are known to play important roles in forming biomolecular condensates, which are regions of high local protein concentration formed via the process of phase separation or related phase transitions8. IDRs and their role in driving phase separation are implicated in various aspects of nuclear organization, but much remains unclear, particularly in the context of chromatin remodeling.

The mammalian SWI/SNF (mSWI/SNF or BAF) ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes collectively represent one of the most frequently mutated cellular entities in human cancer, second only to TP539,10. Indeed, mutational frequencies for all 29 human genes that encode for mSWI/SNF complex subunits tally to over 20% across all human cancers9. mSWI/SNF subunit mutations and translocations represent cancer-initiating events in a number of rare cancers11–13 and are among the most frequently perturbed genes in neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs)14–20.

The most frequently mutated genes within the mSWI/SNF family are the ARID1 genes, ARID1A and ARID1B, which encode 250-kDa paralog subunits (ARID1A and ARID1B) that define and assemble into cBAF subcomplexes in a mutually exclusive manner9,21. ARID1A is mutated in over 8% of all human cancers arising from a range of cell lineages, while in neurodevelopmental disorders, ARID1B is the most recurrently mutated chromatin regulatory gene and one of the top five genes associated with autism19,22–24. These human genetic data imply critical functional contributions of the ARID1 subunits as well as differences between the two paralogs. Recent studies21,25–27 have revealed that the large ARID1 subunits (Swi1 in yeast SWI/SNF) connect the cBAF core with the ATPase module via a conserved core-binding region (CBR) containing 6 tandem Armadillo (Arm) repeats21,27 (Fig. 1A, Fig. S1A). Expression of this CBR is sufficient for cBAF complex biochemical assembly, specifically, binding of the ATPase module on to the cBAF core21. Cancer-associated missense mutations in the C-terminal region destabilize ARID1A and/or prevent its assembly into cBAF complexes21,27; disease-associated mutations in both ARID1A and ARID1B are nonsense and frameshift in nature (Fig. S1B). Intriguingly, the role of the remaining two-thirds of these proteins (65.69% of ARID1A, 1501 amino acids; 68.74% of ARID1B, 1537 amino acids) remains uncharacterized. ARID1A/B N-termini contain two IDRs bridged by a structured ARID DNA-binding domain (Fig. 1A-B, Fig. S1C-D). Most cancer-associated mutations in ARID1A/B genes and NDD-associated mutations in ARID1B fall within the IDRs (~58% and ~83%, respectively) (Fig. 1C). Further, the IDRs of the ARID1A/B N-termini make up ~33% of the IDR content of the entire cBAF complex. Disorder scores (using MobiDB-Lite 3.028) for these ARID1A/B regions are similar to those of prion-like domains known to phase separate, including TDP-43, DDX4, FUS, and others29 (Fig. S1E).

Figure 1. The IDRs of ARID1A/B are dispensable for cBAF assembly and in vitro nucleosome remodeling.

A. Human cBAF complex (PDBDEV_00000056) with putative ARID1A N-terminal region of unassigned cryo-EM density and C-terminal CBR highlighted. B. Disease-associated mutations mapped onto ARID1A/B and disorder as PONDR score. C. Distribution of disease-associated missense and indel mutations in ARID1A/B’s N-terminus. D. Schematic of HA-tagged ARID1A expression constructs. E. Immunoblots of nuclear protein input and anti-HA IPs in AN3CA (ARID1A/B-deficient) cells expressing HA-tagged ARID1A WT or mutant variants. F. TMT mass spectrometric signal for cBAF components from anti-HA ARID1A WT or mutant immunoprecipitation. G. Top, restriction enzyme accessibility assay (REAA) time course using 2.5 nM purified cBAF carrying ARID1A WT or mutant variants; Bottom, REAA using 0–5 nM cBAF (t=30min) (n=2 experimental replicates each). H. ATPase (ADP-Glo) measurements for indicated conditions and timepoints. ns, not significant by one-way ANOVA test.

IDRs within chromatin-bound proteins have putative functional roles including influencing dynamics of chromatin-bound proteins30 and transcriptional activation31, creating reaction crucibles32–34, and heterochromatic silencing35–37. Several pathogenic mutations in human cancer and Mendelian diseases map to condensate-forming proteins39. The functions imparted to nuclear proteins by IDRs remain incompletely understood, particularly in the context of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers.

Here, we find that the ARID1A/B IDRs and DNA-binding ARID domain direct genomic targeting of the cBAF complex and subsequent generation of DNA accessibility, enhancer activation and gene expression, through an IDR-encoded specific biomolecular interaction network.

Results

The ARID1A/B N-terminus is dispensable for cBAF assembly and in vitro nucleosome remodeling

To define the role of the IDR-rich ARID1A/B N-termini with respect to complex assembly and ATPase dependent nucleosome remodeling activities, we generated HA-tagged ARID1A full-length (wild-type, WT) or ARID1A mutant variants that lack IDR1 (ΔIDR1), contain mutations in the ARID DNA-binding domain that compromise DNA binding as assayed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (S1086E, S1087E, S1090E) (DBDmut) (Fig. S1F-G), or lack the entire N-terminus, including IDR1, the ARID domain, and IDR2 (CBR only) (Fig. 1D). We introduced these into AN3CA cells derived from a dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma lacking both ARID1A and ARID1B subunits (and hence, lacking functional cBAF complexes) as well as ARID1A/B-deficient HEK293T cells generated using CRISPR/Cas9-based editing21 (Fig. 1E, Fig. S1H). The C-terminal CBR was sufficient to enable assembly of complexes in both cell types (Fig. 1E, S1I). Protein levels across all mutants were similar to WT and unaffected by proteasome inhibition (Fig. S1J). cBAF complexes purified from cells expressing WT or mutant ARID1A contained similar levels of BAF core and ATPase module subunits, by immunoblot and tandem-mass-tag (TMT) mass spectrometric analyses of HA immunoprecipitations (IPs) (Fig. 1E-F, Table S1). As expected, expression of ARID1A in ARID1A/B-null cells restored cBAF assembly, demonstrated by density sedimentation analysis21 (Fig. S1K). Intriguingly, restriction enzyme accessibility assays (REAA) revealed both WT and mutant complexes purified via HA-IP from ΔARID1A/B HEK293T cells have equivalent nucleosome remodeling activities in vitro, and ATPase catalytic activities in solution (Fig. 1G-H, Fig. S1L-M), suggesting the ARID1A C-terminus is sufficient for cBAF complex assembly, nucleosome remodeling, and catalytic activities, underscoring the need to investigate alternate functional contributions of the large N-terminal region.

The ARID1 disordered regions confer phase separation potential to cBAF complexes

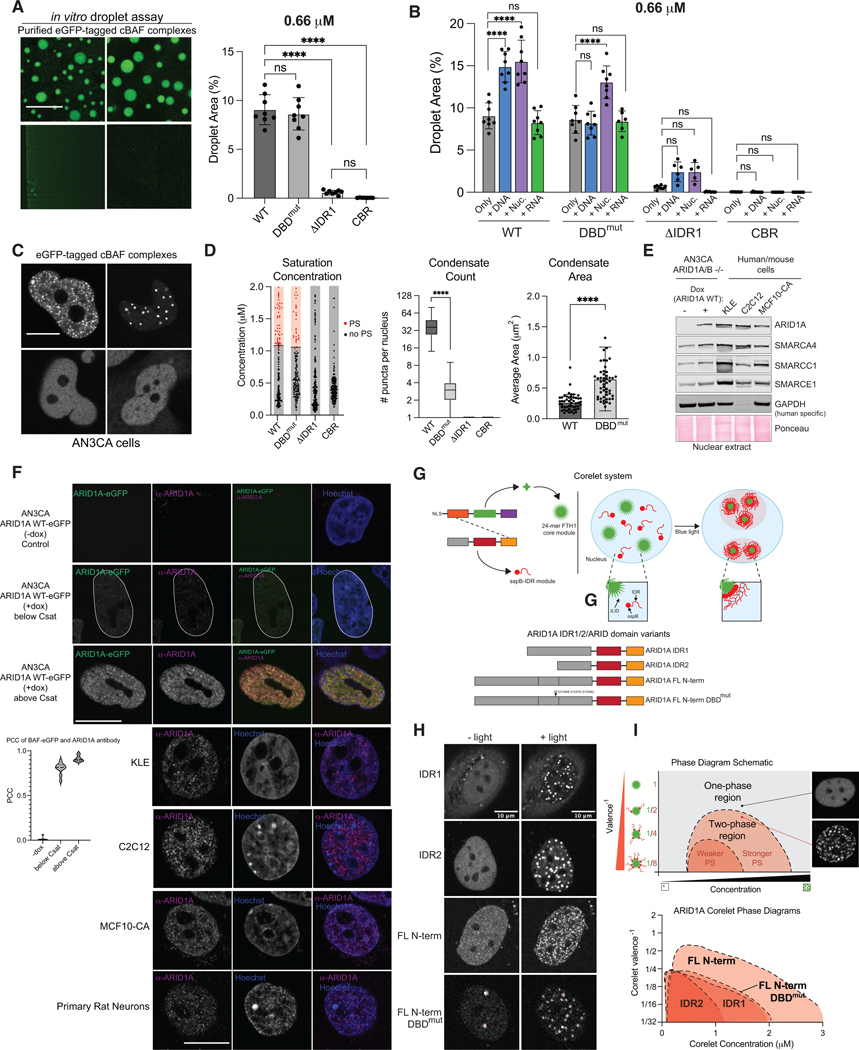

Coupled with the high predictions for disorder and disease relevance of the N-terminal regions, we sought to examine their potential role in cBAF phase separation. We expressed individual C-terminally eGFP-tagged ARID1A WT, DNA-binding mutant, or truncation variants in ΔARID1A/B HEK293T cells, isolated fully assembled cBAF complexes, and performed in vitro condensation (phase separation) assays (Fig. 2A, Fig. S2A-B). Purified protein complexes diluted to 2, 0.66, 0.2, and 0.074 μM in physiological salt buffer with no additional crowding agent (150 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5), were imaged after 30 minutes on a spinning disc confocal microscope to query the presence of condensates. Complexes incorporating WT- or DBDmut-ARID1A formed condensates in solution, while loss of one or both IDRs nearly completely attenuated condensate formation (Fig. 2A, left, S2C). We quantified the presence of condensates using a two-dimensional proxy for volume fraction: percent of the field of view covered by eGFP-positive droplets (Condensate Area, WT 9.05%; DBDmut 8.63%; ΔIDR1 0.59%; CBR 0.04%) (Fig. 2A, right). Addition of 100 nM DNA (linear, dsDNA of random sequence), nucleosomes (mixed mono-, di-, and tri-nucleosomes) or RNA showed that condensate formation was enhanced by DNA and nucleosomes, but not by RNA (Condensate Area WT Only 9.05%; WT + DNA 14.89%, WT + nucleosomes 15.50%, WT + RNA 8.24%), implicating cBAF complex DNA- and nucleosome-binding regions in promoting phase separation (Fig. 2B, Fig. S2D). In addition, WT but not DBDmut samples formed strings of condensates in reactions containing DNA, similar to observations of a pioneer transcription factor40 (Fig. S2E). Of note, cBAF complexes contain several other DNA-binding domains within the core module; so attenuated condensation upon inactivation of the ARID domain alone suggests a prominent role for this domain. Interestingly, while the condensation of cBAF complexes carrying the DBDmut mutant was not enhanced by the addition of DNA, it was enhanced by the addition of nucleosomes, suggesting that bilateral engagement of cBAF at the acidic patch regions27,41 can enhance phase separation independent of ARID domain-mediated DNA binding (Fig. 2B). Addition of either DNA or nucleosomes moderately enhanced condensation of ΔIDR1-containing cBAF complexes presumably via ARID domain-mediated DNA and nucleosome binding, though not significantly relative to complex-only control (Fig. 2B, Fig. S2D). Further, cBAF complexes nucleated by the ARID1A CBR alone failed to form condensates in any of the conditions tested, suggesting that although additional IDRs are present in other cBAF subunits27, they are not sufficient to induce condensation of complexes (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. ARID1A IDRs dictate cBAF complex condensation in vitro and in cells, which is enhanced by DNA binding.

A. Left, in vitro condensation experiments of indicated 0.66 μM eGFP-tagged cBAF complexes; Right, condensate area per field of view. B. Percent condensate-covered area with 100 nM DNA, nucleosomes, or RNA. C. Confocal imaging of eGFP-tagged cBAF complexes containing ARID1A WT or mutant variants in live AN3CA cells. D. Saturation concentration, condensate count and area ARID1A puncta in AN3CA cells. PS: Phase Separation. E. Immunoblot for ARID1A and other cBAF subunits in AN3CA cells −/+ doxycycline alongside human and murine cell types. F. Immunofluorescence of AN3CA cells without or with doxycycline induction of exogenous eGFP-tagged ARID1A. PCC between eGFP-ARID1A and anti-ARID1A immunostaining. Bottom: Immunostain for endogenous ARID1A in KLE (human endometrial), C2C12 myoblast (mouse), MCF10A (human breast cancer), and primary rat neurons. G. Top, schematic of Corelet system used to evaluate self-interaction propensity of IDRs; Bottom, schematic of IDR-containing constructs evaluated. H. Representative images of U2OS cell nuclei without (-light) and with (+light) light-induced oligomerization. I. Top, phase diagram schematic; Bottom, phase diagrams of ARID1A constructs; shaded area indicates two-phase region. In A and B, P-values calculated by one-way ANOVA test. In D, by unpaired student’s t-test.

Next, we evaluated protein dynamics and exchange using Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) in AN3CA cells expressing eGFP-tagged ARID1A/B. Addition of eGFP to ARID1A did not disrupt cBAF complex assembly in AN3CA cells as assayed by IP-immunoblot and density sedimentation analyses (Fig. S2F-H). Indeed, WT ARID1A-carrying cBAF complexes showed a clear punctate pattern by microscopy while disruption of IDRs nearly completely attenuated the presence of nuclear puncta (Fig. 2C-D). ARID1A DBDmut-expressing cells had consistently fewer condensates, each with increased area, likely reflecting enhanced coarsening enabled by loss of targeted interaction with genomic DNA (Fig. 2C-D). Concentration-calibrated fluorescence imaging of eGFP-tagged ARID1A constructs demonstrated a threshold concentration of 1.13 ± 0.11 μM for WT and 1.08 ± 0.16 μM for DBDmut, above which the punctate nuclear pattern is observed (Fig. 2D). Condensation and threshold concentration of all four ARID1A mutants were unaffected by proteasome inhibitor treatment (Fig. S2I). Similar condensation patterns were obtained for the ARID1B paralog subunit (Fig. S2J). Time-lapse imaging showed that individual ARID1A/B nuclear puncta are present over tens of minutes and exhibit fusion and coalescence, which characterizes either purely viscous fluids or viscoelastic materials with terminally viscous properties (Supplemental Movie S1). FRAP experiments in the ARID1A WT condition demonstrated rapid recovery (half time of recovery T1/2 ~5.7 sec and T1/2 ~7 sec for ARID1A and ARID1B, respectively) with low immobile fraction (27%), consistent with viscoelastic materials that feature mobile and immobile species (Fig. S2K). The ARID1A and ARID1B DNA-binding mutants (DBDmut) demonstrated similar dynamics with slight but statistically significant increases in half time of recovery (to T1/2 = 9.4 sec for ARID1A, T1/2 = ~15 seconds for ARID1B) but no change in immobile fraction, indicating that loss of DNA binding activity does not drastically alter protein dynamics (Fig. S2K). By immunoblot, levels of exogenous ARID1A expression in AN3CA cells were comparable to endogenous ARID1A levels across a range of human and murine cell types (Fig. 2E) and immunofluorescence detected punctate nuclear cBAF structures in endogenous contexts (Fig. 2F, Fig. S2L). These data provide the first visual evidence of cBAF condensates under endogenous expression levels.

To further characterize the self-interaction capabilities of the ARID1A/B N-terminal IDRs, we employed the Corelet System42, which makes use of a multivalent ‘Core’ particle (24-mer Ferritin) to act as a scaffold for assembly of phase-separation-prone proteins in a light-dependent manner (Fig. 2G, top). We generated variants of ARID1A containing IDR1, IDR2, or the full N-terminus (IDRs and ARID domain, FL), each lacking the C-terminal BAF-binding CBR region to enable us to study the low-complexity N-terminus in isolation (Fig. 2G, bottom). Notably, the ARID1A N-terminus formed light-dependent condensates over a wide range of concentrations and valences, while IDR alone or DBDmut exhibited significant attenuation in phase separation potential (Fig. 2H-I, Fig. S2M). Again, the DNA-binding domain mutant formed fewer droplets of larger size (Fig. 2H, S2N). Similar results were obtained for ARID1B N-terminus, except that IDR1 more closely mirrored the full-length N-term variant, perhaps suggesting its stronger phase separation propensity (Fig. S2O-P). Repeated on-off light cycles revealed that the specific nuclear localization of ARID1A IDR puncta, observed as high correlation between nuclear positioning in subsequent cycles, was dependent on the ARID domain (Fig. S2Q-R). Together, these data highlight the functionality of the IDRs and ARID DNA-binding domain of ARID1A/B subunits in conferring phase separation and sub-nuclear localization properties to cBAF remodeling complexes.

ARID1A IDRs and ARID domain are required for cBAF targeting, chromatin accessibility and gene expression in cells

To determine the functional contributions of the IDRs and ARID domain of ARID1A/B, we introduced ARID1A WT, ΔIDR1, DBDmut, CBR-only mutant variants (Fig. 1C) or empty vector control into AN3CA cells and performed CUT&Tag43, ATAC-Seq44,45, and RNA-Seq to evaluate chromatin localization of cBAF, DNA accessibility, and gene expression, respectively. We first examined the chromatin occupancy of cBAF complexes, the enhancer mark H3K27ac, and DNA accessibility. Global clustering analyses performed on over 40,964 merged SMARCC1/SMARCA4 sites revealed a set over which only WT ARID1A restored complex occupancy and accessibility, whereas IDR deletion (ΔIDR1, CBR) and ARID domain (DBDmut) mutants were unable to restore these features (Cluster 2: 5042 sites; 12.3%) (Fig. 3A, Fig. S3A). We also identified a cluster that exhibits a similar trend to a lesser extent, with CBR-only mutant being the most deleterious (Cluster 3: 4705 sites; 11.5%) (Fig. 3A, Fig. S3A). Clusters 2 and 3 sites were largely Transcriptional Start Site (TSS)-distal, consistent with an important role for cBAF complexes in enhancer accessibility41,46 (Fig. 3B). Cluster 1 (unaffected by ARID1A expression) contains promoter-proximal sites (Figure 3A-B). Principal component analysis (PCA) of cBAF-occupied enhancer sites demonstrated a distinct clustering pattern, with the DBDmut most similar to WT, and ΔIDR1 and CBR mutants closest to empty vector control (Fig. 3C). These findings are exemplified at intragenic enhancers at the MAP2 and NCAPH loci and an intergenic enhancer within chromosome 2 (Fig. 3D). Consistent with in vitro remodeling data demonstrating that the N-terminus is not required for ATPase activity (Fig. 1G-H), we did not identify sites with intact mutant complex targeting but loss of accessibility, suggesting genomic targeting of the complex, not core enzymatic remodeling activity, is compromised in these mutants (Fig. 3A). The number of sites affected genome-wide (n= 9747 total for Clusters 2 and 3) mirror those affected by complexes containing defects in the ATPase activity itself (i.e., K785R of SMARCA4), or complexes lacking core components such as SMARCB1 or SMARCE112,13,41,46, suggesting that disruption of the IDRs of the ARID1 proteins direct similar consequences for cBAF complex targeting as disruption of these structurally integral subunits.

Figure 3. ARID1A IDRs and DNA-binding functions govern cBAF occupancy, DNA accessibility and gene expression in cells.

A. Chromatin occupancy of cBAF complexes marked by HA (ARID1A), SMARCA4, and SMARCC1, H3K27ac enhancer mark occupancy and DNA accessibility (ATAC) at cBAF-occupied sites in AN3CA cells, divided into 4 clusters using k-means clustering. B. Distance-to-TSS distribution of merged CUT&Tag and ATAC-Seq peaks for all conditions, across Clusters 1–4 from (A). C. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of cBAF-occupied enhancer sites across conditions as assayed by SMARCA4 and SMARCC1 signals. D. Representative CUT&Tag and ATAC-Seq tracks at the MAP2, NCAPH, and intergenic enhancer loci in AN3CA cells across Empty and ARID1A WT or mutant conditions. E. Overlap of accessible sites by ATAC-Seq in empty vector control (Empty) versus ARID1A WT or mutant conditions in AN3CA cells. Gained sites relative to empty condition are highlighted in bold. F. Transcription factor motif enrichment analysis (HOMER) at Clusters 2, 3, and 4 from (A). G. Box and whisker plot for all conditions comparing expression levels of top differentially expressed genes (DEGs) upon ARID1A WT introduction versus empty control.

At a global level, WT ARID1A expression led to a significant increase in accessibility by ATAC-Seq compared to empty vector control (39170 de novo sites) (Fig. 3E). Accessibility gains were reduced upon expression of each mutant variant relative to WT (DBDmut = 20797, ΔIDR1= 9931, CBR= 8539 sites), with CBR mutant resulting in the lowest accessibility, followed by the ΔIDR1 and DBDmut mutants (WT > DBDmut > ΔIDR1 > CBR) (Fig. 3E, Fig. S3B). PCA performed across all ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq conditions similarly revealed the DBDmut clusters closer to WT than ΔIDR1 and CBR mutants (Fig. S3C-D). These data collectively indicate that loss of the ARID1A N-terminal IDR and/or DNA-binding regions of BAF complexes result in substantial changes in targeting and genomic accessibility in cells. Accessible sites in ARID1A-mutant conditions represented a subset of those generated by ARID1A WT (Fig. S3E), with significant overlap among one another, exemplifying the convergent deficits in differentially perturbed cBAF complexes (Fig. S3E-F).

Sites most affected by disruption of the ARID N-terminus were enriched in transcription factor (TF) motifs corresponding to the AP-1, FOS/Jun, NF1, and TEAD factors, several of which have been shown to localize to enhancers via interaction with mSWI/SNF complexes (Fig. 3F)47,48. 72% of accessible sites gained in cells expressing WT ARID1A showed a concordant increase in occupancy of H3K27ac, and were enriched for similar transcription factor motifs as Cluster 2 and 3 sites (Fig. S3G-H, Fig. 3A, Fig. 3E). Intriguingly, sites at which cBAF complex occupancy and DNA accessibility were reduced upon rescue with WT ARID1A but not the mutant variants or empty vector control were significantly enriched for CTCF and CTCFL (BORIS) motifs (Cluster 4: 5915 sites), consistent with recent observations that lack of cBAF assembly and/or function results in increased non-canonical BAF (ncBAF) complex abundance and function at its key target sites (CTCF) (Fig. 3F, Fig. 3A, Cluster 4, Fig. S3A)49,50.

Finally, we found that relative to WT ARID1A, expression of ARID1A N-terminal mutants resulted in attenuation of gene expression (Fig. 3G, Fig. S3I). Globally, we identified a greater number of upregulated and downregulated transcripts in mutant conditions, with the CBR mutant resulting in the fewest upregulated transcripts (Fig. S3J-K). In this AN3CA endometrial cellular context specifically, N-terminal mutants failed to rescue expression of genes involved in endometrial cell differentiation (Fig. S3L), suggesting that condensation of cBAF is essential to its genome-localized nucleosome remodeling function. These data demonstrate that the IDR-rich N-terminus, coupled with the ARID DNA-binding domain, are together required for the stable occupancy of cBAF complexes at distal enhancers over which they establish and maintain accessibility.

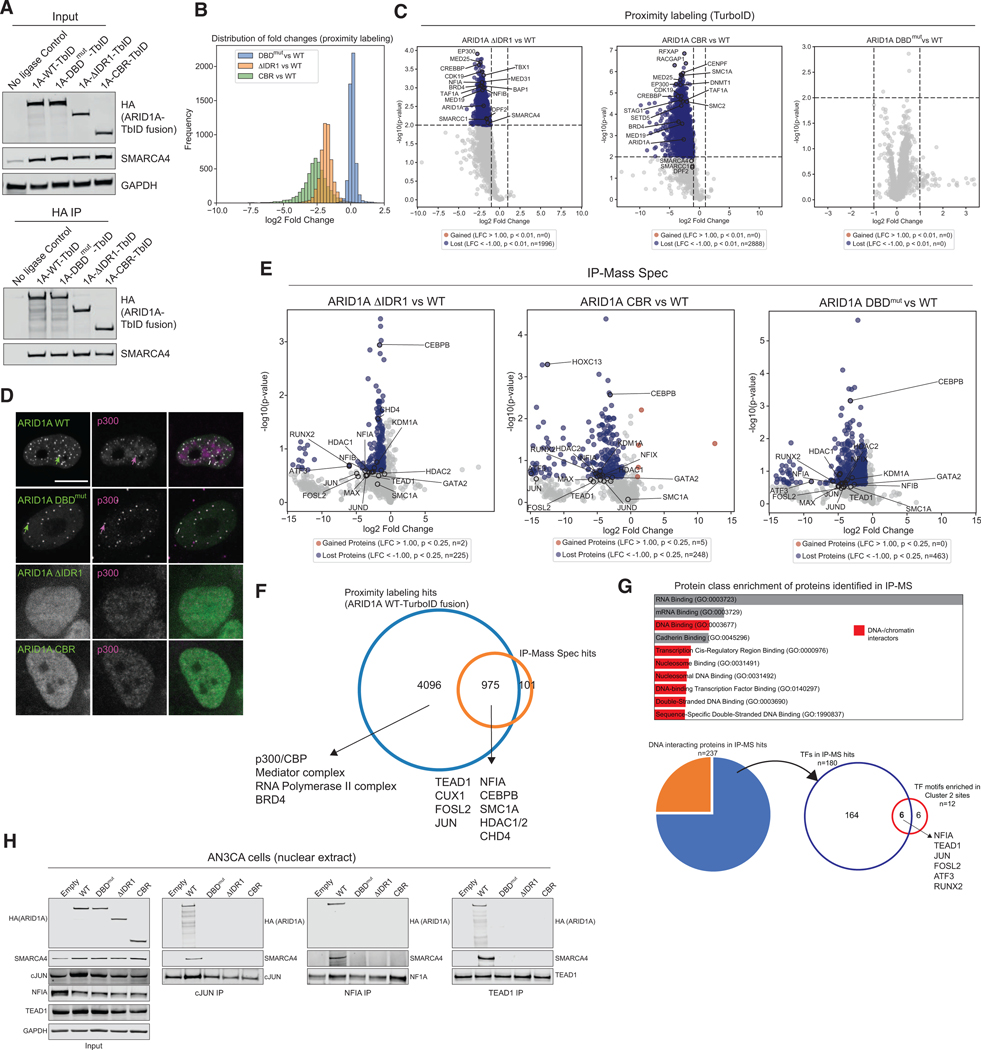

Heterotypic cBAF interactions with transcription factors require IDR sequences and the ARID DNA-binding domain of ARID1A

We sought to define the mechanistic basis underlying the necessity of the ARID1A/B N-termini for cBAF function. We reasoned that proteins localizing into ARID1A/B-containing nuclear condensates could be identified by their proximity, and so performed proximity labeling followed by mass-spectrometry by fusing an engineered biotin ligase TurboID (TbID)51,52 to the C-terminus of ARID1A WT and mutant variants to map changes in the proximal protein repertoire of cBAF complexes (Fig. S4A). TbID fusion did not disrupt nucleation and assembly of cBAF (Fig. 4A). Upon confirmation of self labeling of the bait (ARID1A), non-self labeling with biotin (50μM for 10 minutes), and visualization with streptavidin (Fig. S4B), we performed TMT mass spectrometry to identify proximal proteins for each cBAF complex variant (Fig. S4C). Notably, truncation of the full N-terminal region or IDR1 alone, but not inactivation of the ARID DNA-binding domain (DBDmut), resulted in a significantly depleted repertoire of proximal proteins (Fig. 4B, Table S2). This set of proteins was enriched in factors associated with chromatin organization, histone modification, and transcription (Fig. 4C, Fig. S4D). Losses in associated proteins were IDR-dependent with no significant changes in the DBDmut mutant (relative to WT) (Fig. 4C). We found that mSWI/SNF components themselves (cBAF as well as PBAF and ncBAF) were markedly reduced near cBAF complexes lacking the IDRs of ARID1A (Fig. S4E, left), with no change in total nuclear protein level (Fig. S4E, right), indicative of reduced proximity due to a loss of condensate formation. Furthermore, we measured a marked reduction in the abundance of Mediator complex components, RNA Polymerase II, the p300 acetyl transferase, and selected TFs in proximity of IDR-mutant complexes relative to WT, again, absent changes in corresponding nuclear protein levels (Fig. S4F-G). To validate these data, we performed immunofluorescence colocalization studies of p300 with ARID1A-WT or -mutant cBAF complexes. Consistently, we found altered nuclear distribution of p300 and a loss of co-condensation with cBAF (Fig. 4D, Fig. S4H-I). These findings demonstrate the critical role of the ARID1A N-terminal IDR1 in facilitating localized condensation of cBAF complexes and their association with the transcriptional machinery, TFs, and other factors required for functional chromatin remodelling.

Figure 4. ARID1A IDRs mediate local proximity of cBAF complex with cellular transcriptional machinery, enabling ARID domain-dependent TF binding.

A. Immunoblot for input and anti-HA IP from AN3CA cells expressing HA-ARID1A fused to biotin ligase TurboID (TbID). B. Distribution of biotinylated proteins fold changes. C. Volcano plots comparing biotinylated protein levels. D. Immunofluorescence analysis of ARID1A and p300 in AN3CA cells. E. Volcano plots comparing detected protein levels following IP-Mass Spec. F. Overlap of ARID1A WT-carrying cBAF interactomes measured using proximity labeling or IP-Mass Spec. G. Protein class enrichment of detected cBAF interacting proteins via IP-MS (DNA interactors in red). H. Input and selected transcription factor (cJUN, NFIA, TEAD1) reciprocal IPs using AN3CA cells expressing empty vector or WT- and mutant-ARID1A.

Though the proximal protein repertoire of ARID1A DBDmut carrying cBAF complexes was similar to that of WT cBAF, these complexes were defective in genomic localization (Fig. 3A). To identify the reason behind this observation, we used IP-Mass Spectrometry (IP-MS) to identify high-stringency protein interactors of cBAF complexes and determine whether these interactors are lost upon ARID mutation. We identified 1076 interacting proteins that were dependent on ARID1A WT for association with cBAF, >90% of which overlapped with those identified in the TurboID-based proximity labeling experiments (Fig. 4E-F, Fig. S4J, Table S2). cBAF-interacting factors were particularly enriched for TFs such as FOS/Jun, TEAD1, NFIA, NFIB, RELA, GATA2, ATF3, and CUX1, consistent with the roles of TF-cBAF interactions in genomic navigation53,54 (Table S2). The identified TFs correspond to key cognate DNA motifs that were enriched under ARID1A IDR-dependent sites genome-wide (Fig. 4G, Fig. 3F, Fig. S4K). Of the DNA-interacting IP-MS hits, 75% are transcription factors, of which, six that interact with cBAF by IP-MS also have motifs enriched in Cluster 2/3 sites, including cJUN, NFIA and TEAD1 (Fig. 4G). Importantly, by IP-MS, ARID1A DBDmut-carrying complexes were equally deficient for TF tethering as IDR-mutant complexes (Fig. 4E, Fig. 3A), suggesting that the ARID domain stabilizes a broad set of TF-cBAF interactions. Similarly, transcription initiation machinery components detected by proximity labeling were not enriched by IP-MS, indicating these factors localize near to but do not directly bind cBAF complexes (Fig. 4F, Table S1). Finally, reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblots for selected TFs demonstrated specific binding to WT but not mutant ARID1A-containing cBAF complexes, indicating these interactions are dependent on the N-terminus (Fig. 4H, Fig. S4L). These parallel proximity labeling and IP-MS experiments define the related but distinct sets of proximal and stringent interactions mediated by the ARID1A N-terminus, and the role of the ARID domain in stabilizing functional associations with TFs mediated by disordered regions within ARID1A.

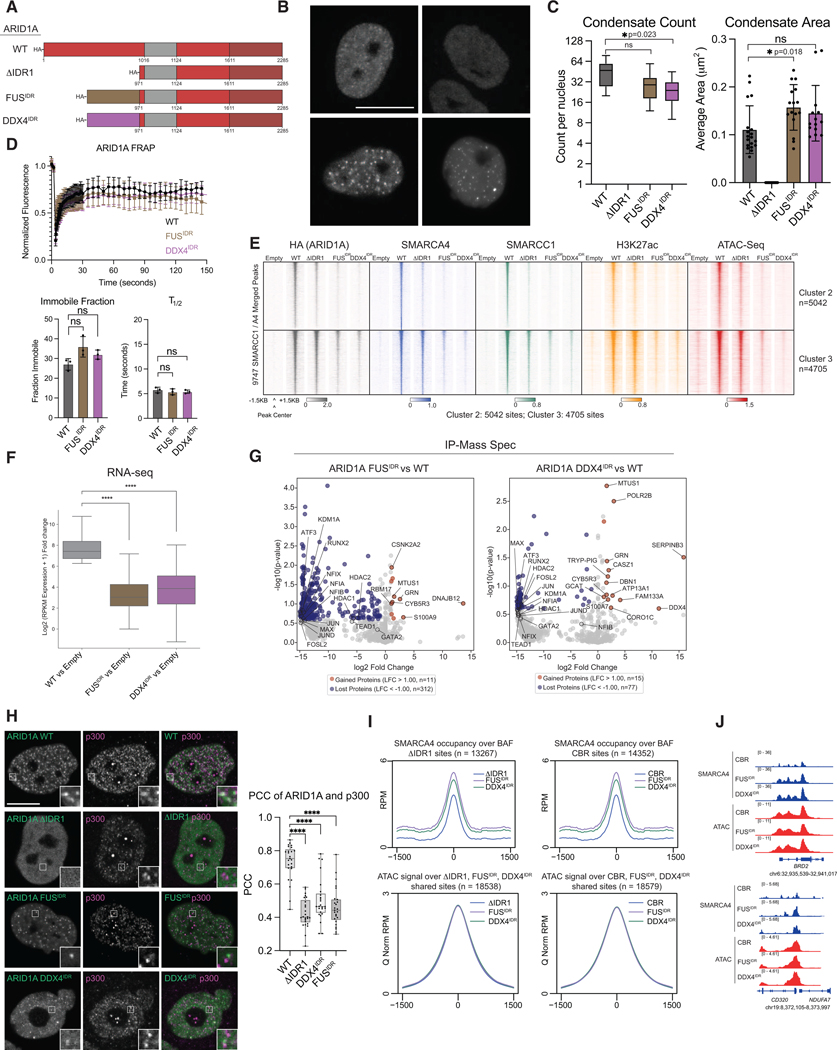

Genomic targeting and protein interactions of cBAF complexes requires the ARID1A-specific IDR

Given the critical role of the ARID1A/B IDRs in driving condensation, protein interactions, and genomic localization of cBAF in cells, we sought to determine whether these functions can be performed by other phase separation-prone IDRs. To evaluate this, we generated constructs replacing IDR1 of ARID1A with alternate well-known self-interacting IDRs from FUS and DDX455 (Fig. 5A). As expected, given the retention of the ARID1A CBR, these fusion constructs were able to nucleate cBAF assembly in AN3CA cells (Fig. S5A). Live-cell microscopy revealed the presence of condensates in FUSIDR- and DDX4IDR-ARID1A mutant expressing cells, comparable in count, area, saturation concentration and FRAP dynamics to those detected in the ARID1A WT condition (Fig. 5B-D, Fig. S5B-C), suggesting that these alternate IDRs are sufficient for condensation of cBAF in living cells.

Figure 5. Sequence-specific heterotypic interactions of ARID1A IDR1 are required for cBAF-mediated chromatin and gene regulation.

A. Schematic of ARID1A FUSIDR and DDX4IDR fusion mutant variants. B. Representative images of eGFP-tagged constructs in live AN3CA cells. C. Count and average area of condensates. Statistical test: one way ANOVA. D. FRAP curves, Immobile fraction, and half time of recovery (T1/2) quantification for indicated constructs. Error bars: standard deviation. n = 3 biological trials, 15 cells each. Statistical test, one way ANOVA. E. Chromatin occupancy of cBAF complexes marked by HA (ARID1A), SMARCA4 and SMARCC1, H3K27ac enhancer mark occupancy and DNA accessibility (ATAC-Seq) at Cluster 2 and 3 sites from Fig. 3A. F. Fold change of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) relative to empty vector. G. Volcano plots comparing detected protein levels by IP-MS. Hits meeting the cut off of log2 fold change <−1 and >1 and p-value <0.25 are blue and red, respectively. H. Immunofluorescence analysis of ARID1A and p300. I. Top, metaplots of SMARCA4 occupancy over cBAF sites (shared SMARCA4/SMARCC1 sites) ΔIDR1 (left) or CBR-only (right) cBAF complex target sites; Bottom, metaplots of ATAC-Seq accessibility. J. Example tracks of SMARCA4 occupancy and DNA accessibility in the ARID1A CBR-only, FUSIDR, and DDX4IDR mutant conditions at the BRD2 and CD320 genomic loci.

To define whether FUSIDR/DDX4IDR-ARID1A can rescue cBAF chromatin-targeting, we profiled complex occupancy, DNA accessibility and gene expression in AN3CA cells. We focused specifically on de novo cBAF-occupied and accessible sites that were specific to the WT ARID1A condition (Fig. 3A, Clusters 2, 3). Importantly, cBAF complexes containing FUSIDR/DDX4IDR-ARID1A were unable to recapitulate WT targeting, indicating sequence-specific functions of ARID1A IDR1 (Fig. 5E, Fig. S5D-E). PCA of ATAC-Seq sites revealed that FUSIDR and DDX4IDR ARID1A mutants clustered more closely with ΔIDR1 than ARID1A WT, suggesting that although they rescue cBAF condensation, they fail to recapitulate genomic targeting, and implicating ARID1A IDR1 in cBAF chromatin occupancy (Fig. S5E). Importantly, FUSIDR/DDX4IDR-ARID1A variants failed to activate gene expression relative to WT ARID1A (Fig. 5F, Fig. S5F).

Next, we investigated the underlying basis for the specificity of ARID1A IDR1 in mediating cBAF activity using IP-MS experiments. Following confirmation that replacement of ARID1A IDR1 with FUS- or DDX4-derived IDRs does not alter cBAF assembly (Fig. S5G), we found that FUSIDR- and DDX4IDR-ARID1A mutant carrying cBAF complexes each failed to capture TFs associating with WT cBAF complexes (Fig. 5G, Table S1). As expected, proximity labeling experiments using a FUSIDR-ARID1A-TbID fusion construct confirmed that FUSIDR-ARID1A failed to restore proximity of cBAF to TFs and the transcriptional machinery relative to ARID1A WT (Fig. S5H-I, Table S2). Instead, the repertoire of proteins nearby FUSIDR-ARID1A containing cBAF complexes were more similar to the ΔIDR1 ARID1A mutant-carrying BAF (Fig. S5J, Fig. S4F). Further, immunofluorescence confirmed that p300 does not colocalize with cBAF complexes carrying FUS/DDX4IDR-ARID1A fusions, without affecting nuclear protein levels of p300 (Fig. 5H, Fig. S5K-L). Finally, FUS/DDX4IDR-ARID1A fusions had increased occupancy over ΔIDR1 or CBR-only ARID1A bound sites, absent any corresponding changes in chromatin accessibility (Fig. 5I), exemplified over the BRD2 and CD320 loci (Fig. 5J), suggesting similar off-target binding in all these mutant conditions. These data indicate that generic condensation of BAF is insufficient for genomic targeting in cells, imparting a marked specificity to the ARID1A N-terminal IDR and indicating that condensate-driving IDRs need not be functionally interoperable with one another.

Analysis of ARID1A IDR1 sequence features enables uncoupling of condensation and heterotypic protein-protein interactions

To decipher the underlying basis of the specificity of ARID1A IDR1, we performed IDR-specific comparative analyses of the “sequence grammar” of ARID1A/B IDRs, including distinctive compositional biases, non-random binary sequence patterns that influence conformational properties of IDRs, and the presence, if any, of short linear motifs56. To uncover these features, we collated all disordered sequences across the entire mSWI/SNF family of protein subunits (within cBAF, PBAF, ncBAF complexes) and analyzed their amino acid compositional and sequence patterning features using the NARDINI+ algorithm6,56,57, which combines the work of Zarin et al., and Cohan et al, and enunciates the findings in terms of sequence feature vectors. These vectors were then hierarchically clustered using Euclidean distance and Ward’s clustering6,56. We found that IDR1 of ARID1A and ARID1B cBAF-defining subunits represents a distinct evolutionary cluster away from all other mSWI/SNF IDRs, including IDR2 of ARID1A/B, indicating that they harbor distinctive non-random sequence features (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. Sequence patterning analysis enabled separation of condensation and heterotypic interaction functions in ARID1A IDR1.

A. Clustering analysis of non-random amino acid sequence features performed across all IDRs within mSWI/SNF proteins. Z-scores for enriched/’blocky’ or depleted/’well-mixed’ sequence features are shown as a green-to-purple color scale. Red arrow: ARID1A/B IDRs. IDR sequence feature key in panel B. B. Left, enrichment of amino acid sequence features across Clusters 1–4 of mSWI/SNF IDR patterns; Right, IDR sequence feature key. C. Schematic for 42YS and AQG scramble ARID1A IDR1 rationally designed mutant variants. D. NARDINI plots of ARID1A IDR1 WT, AQG scramble and 42YS mutant IDRs. Amino acid key on left. E. Immunoblot for input and anti-HA IP from AN3CA cells. F. Live cell imaging of eGFP-tagged cBAF complexes containing WT ARID1A and the 42YS or AQG scramble IDR1 variants. G. Condensation metrics for ARID1A WT and mutants (3 biological trials of n=25 cells each); error bars represent SEM. **p=0.002 by unpaired t-test. H. Clustered heatmap of chromatin occupancy of cBAF complexes marked by HA (ARID1A), SMARCA4 and H3K27ac enhancer mark occupancy and DNA accessibility (ATAC-Seq) across empty, WT ARID1A and the 42YS or AQG scramble IDR1 ARID1A mutants. I. Overlap between Cluster B lost sites from H and Clusters 2,3 lost sites from Figure 3A. J. Top DEGs in WT and 42YS and AQGscram conditions relative to empty control. K. TbID proximity labeling results for the AQG scramble and 42YS mutants compared to ARID1A WT. Hits meeting the cut off log2 fold change < −1 and >1 and p-value <0.2 are labeled in blue. L. Immunofluorescence of p300 and eGFP-tagged cBAF complexes containing WT ARID1A or AQG scramble. M. Nuclear protein input and anti-TF IP-immunoblot studies.

The ARID1A/B IDR1s are uniquely enriched in Alanine-Glutamine-Glycine stretches or “blocks” (Fig. 6B, Fig. S6A). This highly non-random blocky patterning in the ARID1A/B IDR1s was found to be conserved across eukaryotes (at the phyla level) despite divergence in the amino acid sequence across homologs (Fig. S6B). Additionally, we identified a pronounced compositional bias, with more than 40 aromatic residues (Tyrosine, Tryptophan, and Phenylalanine) distributed uniformly across the 1016-amino acid IDR; aromatic residues contribute to pi-pi and cation-pi interactions that have been shown to drive homotypic (self) interactions and phase separation in IDRs from other condensation-prone proteins including FUS58,59. Given these features, we next generated ARID1A IDR1 mutant variants that either disrupt blockiness of AQG patches by scrambling the amino acid content within them (AQGscram), or disrupt aromatic character by mutating 42 Tyrosines to Serines (42YS) (Fig. 6B-C). Both designs maintain the overall IDR length. Disruption of AQG blocks in the AQGscram mutant and preservation in the 42YS mutant were confirmed using NARDINI6 (Fig. 6D). Following confirmation that these mutant variants maintained expression level and complex integration when expressed in AN3CA cells, we performed live condensate imaging. ARID1A 42YS mutant-containing cBAF complexes failed to form condensates in cells, while the AQGscram mutant-containing complexes formed condensates comparable to those carrying WT ARID1A, with slightly increased area and attenuated FRAP recovery times (Fig. 6E-G, Fig. S6C). These data indicate that the 42 Tyrosine residues found in ARID1A IDR1 are the main “stickers”60 that drive phase separation of the 1.04 MDa cBAF complex, and that the evolutionarily conserved, non-random AQG blocks found in this region are not essential for cBAF condensate formation.

Importantly, both the 42YS and AQGscram ARID1A mutant variants show equivalent failure to rescue cBAF localization and DNA accessibility at de novo WT cBAF-occupied sites (n=9159 sites), in a manner similar to the DBDmut, ΔIDR1, and CBR mutants (Fig. 6H, Fig. S6D-H, Fig. 3A). >60% of the sites with reduced occupancy of these two convergent mutants overlapped with reduced occupancy sites in ΔIDR1, CBR, or DBDmut contexts (Fig. 6I, S6F-G, Fig. 3A, Clusters 2 and 3). At the gene expression level, expression of 42YS and AQGscram ARID1A mutants resulted in overall downregulation of genes relative to WT ARID1A (Fig. 6J, S6H).

To further understand the mechanism of action of these two IDR disruptions, we mapped the proximal protein repertoire of complexes containing the 42YS or AQGscram mutant using TbID-based proximity labeling. Intriguingly, we find that complexes carrying the 42YS mutant have a comparable proximal protein repertoire to WT, while complexes containing the AQGscram are severely deficient in their interaction network (Fig. 6K, Table S2). Indeed, we found a significant reduction in p300 colocalization in the setting of the ARID1A AQG scramble variant (Fig. 6L, Fig. S6J). Both mutants are deficient in direct TF tethering, as assayed by coimmunoprecipitation immunoblot analysis of the TFs NFIA and TEAD1 (Fig. 6M). This suggests a sequence-encoded separation of functions for the ARID1A N-terminal IDR1 region, namely condensate formation through Tyrosine residues, and partner protein interactions through specificity imparted by AQG blocks. Both roles together are essential for direct TF tethering and proper genomic localization of cBAF in cells. Of note, FUS and DDX4 IDRs also utilize aromatic residues for pi-pi (FUS) and cation-pi (DDX4) interactions as drivers of condensation though they lack the AQG blocks found in the ARID1A IDR. Therefore, while these orthogonal systems were able to rescue condensation of cBAF in cells, they were unable to recapitulate the network of functionally relevant heterotypic interactions (Fig. S6H, Fig. 6A-C).

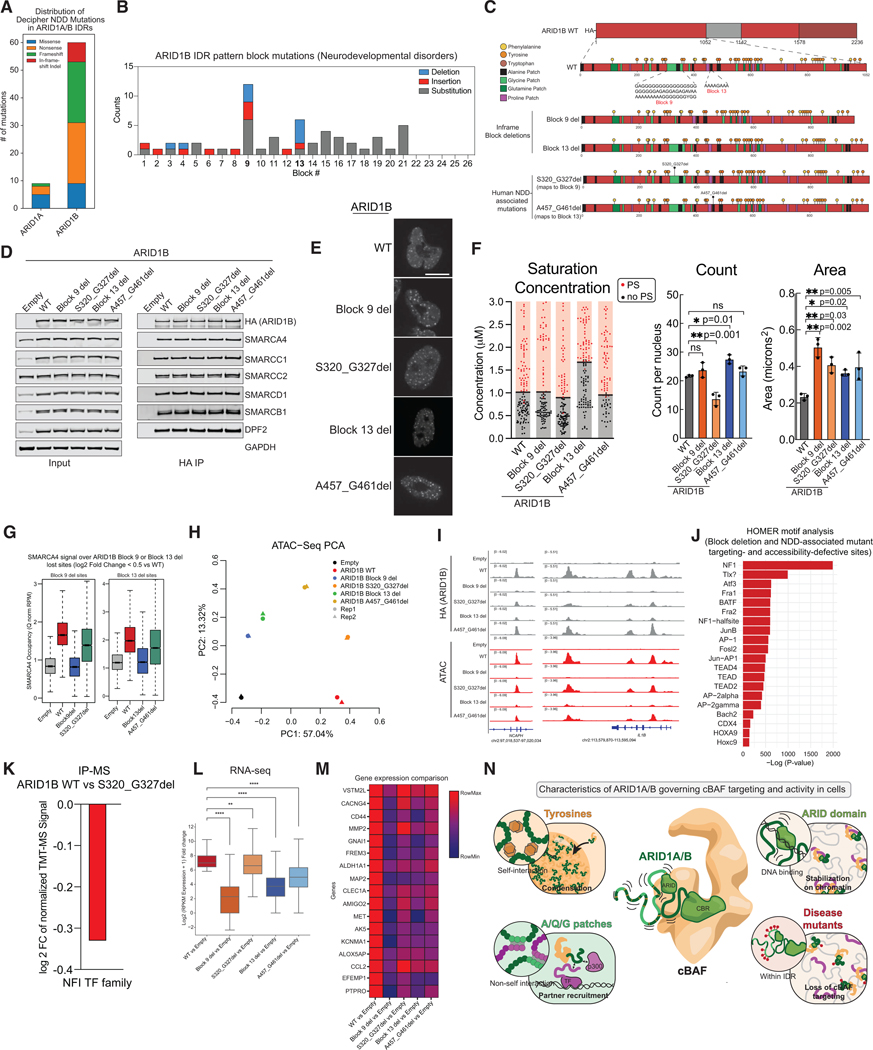

NDD-associated mutations in ARID1B IDR1 sequence blocks disrupt cBAF condensate formation and chromatin localization

Finally, we sought to utilize our understanding of IDR sequence grammar to rationalize human disease-associated missense mutations that localize to the IDRs of ARID1A/B. Referencing a collated list of neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD)-associated mutations from the DECIPHER database, we find that ARID1B is enriched for this category of mutations relative to its paralog, ARID1A (Fig. 7A, Fig. S7A).

Figure 7. Mutations in ARID1B IDR1 sequence pattern disrupt condensation and genomic targeting of cBAF.

A. Mutational frequencies in ARID1A/B IDRs associated with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) from DECIPHER. B. NDD-associated mutations (DECIPHER) plotted across the 26 sequence blocks within IDR1 of ARID1B. C. Schematic of ARID1B WT, block deletion, and NDD mutants. D. Immunoblot for nuclear input and anti-HA IP experiments in AN3CA cells expressing HA-tagged ARID1B WT or mutants. E. Representative images of eGFP-tagged ARID1B in AN3CA cells. F. Condensation metrics of ARID1B in AN3CA cells. G. SMARCA4 genomic localization over severely lost sites in Block 9 deletion (left) and Block 13 deletion (right). H. PCA of ATAC-Seq peaks across ARID1B WT and mutant conditions. I. Example tracks of cBAF localization and ATAC accessibility over NCAPH and IL1B loci in ARID1B WT and mutant conditions. J. Transcription factor motif enrichment analysis (HOMER) of Cluster Y sites (Figure S7). K. Change in NFI TF family TMT-MS signal in the S320_G327del mutant condition relative to WT ARID1B. L. Differential gene expression changes for top upregulated genes in WT versus Block 9 and 13 deletions and mutant conditions. M. Relative gene expression changes of top differential genes across WT and mutant conditions. N. Model highlighting the role of the ARID1A N-terminus.

Mapping the occurrence of NDD-associated mutations within the 26 AQG-rich blocky sequences (Fig. 6) reveals that Block 9, a large A/G-rich block, and Block 13, a shorter polyA-rich sequence, are disproportionately perturbed (Fig. 7B, 7C). We designed and cloned ARID1B in-frame truncation variants lacking these regions (Block 9 or Block 13 deletion) and selected causal NDD-associated mutations falling within these regions (S320_327del within Block 9, and A457_G461del within Block 13) (Fig. 7C) to test for condensation, genomic localization, and accessibility generation in cells. As expected, the ARID1B mutant variants did not affect cBAF complex assembly (Fig. 7D). We found that the block deletions and patient-derived ARID1B mutant-carrying complexes are still capable of condensation (Fig. 7E), and their mobility by FRAP is not significantly different from wild-type (Fig. S7B), in line with the result that scrambling the blocky AQG sequences did not abolish condensation propensity or significantly affect cBAF complex diffusion (Fig. 7E, Fig. 6F). Interestingly, the saturation concentration of Block 13 del mutant is higher than wild type, suggesting that deleting this block disrupts self-interaction, though this phenotype is not significant in the shorter patient derived A457_G461del mutant (Fig. 7E-F). While we do not observe major changes in condensate count (except for the S320_G327del mutant), we notice an overall increase in condensate area (Fig. 7F), similar to that observed for the ARID DNA-binding domain mutant variant (Fig. 2D), suggesting that these mutations may disrupt TF tethering or chromatin-bound stability. To contextualize these results, we measured the effect of the SMARCA2/4 ATPase inhibitor, Compound 14, on the condensation propensity of the complex61,62. ATPase inhibition has been demonstrated to result in destabilized cBAF complexes at distal enhancers at which they interact with key TFs, resulting in accumulation of complexes over open promoters46,63. Consistently, upon ATPase inhibition, we find formation of cBAF condensates, albeit fewer puncta and with greater area per nucleus (Fig. S7C).

We mapped chromatin occupancy of cBAF carrying ARID1B WT or mutants (CUT&RUN) and measured DNA accessibility (ATAC-Seq) as well as gene expression (RNA-Seq) to test the functional impact of deletion and disease-associated IDR perturbations on cBAF function. We found that the Block 9 and Block 13 deletion mutants exhibit substantial loss of localization, while patient-derived mutants S320_G327del and A457_G461del that map to Blocks 9 and 13, respectively, result in partial but significant localization defects, consistent with their compatibility with life in individuals with NDDs (Fig. 7G-H, S7D-F). These findings are exemplified at the NCAPH and IL1B loci on chromosome 2 (Fig. 7I). Importantly, HOMER TF motif enrichment analyses identified motifs corresponding to the AP-1, FOS/Jun, NF1, and TEAD factors to be enriched over sites at which cBAF complexes were defective in targeting and accessibility generation in the mutant conditions relative to WT ARID1B (Fig. 7J). In line with this, by IP-mass spectrometry, we identified a significant reduction in association of the NFI TF family with cBAF complexes carrying the NDD-associated S320_327del ARID1B variant (Fig. 7K, Table S1). Finally, NDD-associated mutations and block deletions resulted in a significant attenuation in gene expression activation relative to ARID1B WT, particularly over key differentiation-associated genes (Fig. 7L-M). These results underscore the impact of in-frame disruptions within the ARID1A/B IDRs on cBAF remodeler function and present a foundation for the mechanistic assignment and characterization of such mutations in human disease.

Discussion

Most studies on chromatin regulatory complexes, including mSWI/SNF complexes, have focused on highly structured domains, characterizing how their physical features dictate chromatin binding and activity. Our findings provide understanding of a unique disordered domain present on a remodeler, the mSWI/SNF family cBAF complex, for which localized condensation and heterotypic interactions are both essential, and independently directed by a distinct set of non-random sequence features encoded within ARID1A/B N-terminal IDRs (Fig. 7N). These features are critical in governing cBAF-mediated genome-wide targeting, accessibility generation, and gene regulatory activities.

Our results reveal that IDR1 of ARID1A/B carries a set of unique sequence features relative to all IDR sequences within the mSWI/SNF family subunits (Fig. 6A). We found that deleting IDR1 alone almost entirely prevents condensate formation of full, >1.5 MDa cBAF complexes in cells. Additionally, within IDR1, short GA/A block deletions or NDD-associated mutations within these blocks maintained condensation but attenuated TF binding and genomic targeting of WT cBAF complexes. Furthermore, our data imply that while other cBAF complex subunits contain IDRs, they do not confer self-interaction properties sufficient for condensation. Beyond cBAF, additional subunits within the mSWI/SNF family contain IDRs, suggesting by extension that IDRs of related chromatin remodelers may serve as critical components of spatial genome organization (Fig. S6A). Further, the protein subunits that comprise human cBAF complexes contain increased intrinsic disorder relative to those of yeast SWI/SNF complexes27. This suggests a model in which additional IDRs evolved to confer condensation properties and highly specific protein-protein interaction networks, to facilitate gene regulation in the mammalian nucleus.

Incubation of cBAF complexes with DNA in vitro potentiates condensation. This can be reversed by inactivation of ARID DNA-binding domain, despite the fact that the core module of cBAF complexes contain several other sequence non-specific DNA-binding domains, highlighting its unique function (Fig. 2A-B). Moreover, the ARID domain is required for cBAF to appropriately interact with TFs in the nucleus (Fig. 4E), implying a distinct role for the ARID1A/B ARID domain. These results begin to provide insights regarding the order of events of nucleation and assembly of cBAF complexes on chromatin, their interactions with DNA, and their association with binding partners.

One notable finding of our study is that alternate low complexity IDRs derived from unrelated proteins cannot rescue cBAF genomic targeting and protein interactions in cells (Fig. 5E, Fig 5G) despite identical condensation properties (Fig. 5C-D), underscoring the key roles for condensation-specific and interaction-specific sequence grammars in IDRs64–75. The integrative approach used here enabled our conclusions; indeed, quantification of condensation alone would have suggested the IDR swap mutants are functionally comparable to WT ARID1A, yet when combined with genomic and biochemical evaluation, we found that condensation alone does not confer cBAF function.

Importantly, condensate formation and heterotypic biomolecular interaction networks can be distinct, each playing critical but separable roles in biological function. We demonstrate here that condensate formation and protein-protein interactions of the ARID1A N-terminal IDR are independent of each other, but they are both required for chromatin targeting of cBAF in cells. Our results suggest that cells may be able to regulate and evolve these features independently to create localized, compositionally defined, and functionalized, high concentration compartments in a modular way.

Our analysis of the non-random sequence features of cBAF IDRs provides a framework upon which to mechanistically assign the extensive number of disease-associated missense and indel mutations that fall within the ARID1A/B IDRs (Fig. 1C). Our data suggest that NDD-associated changes of just a few amino acids within the ARID1B IDR partially alters condensation properties, TF interactions, and chromatin-level targeting in cells (Fig. 7), though expectedly these changes are more subtle than full block deletions or complete IDR deletion (Fig. S7G), in agreement with the knowledge that NDD-associated mutations are live birth compatible. Intellectual disability (Coffin-Siris syndrome)-associated mutations in the C-terminal domain of the SMARCB1 subunit result in similarly subtle live-cell phenotypes41.

Limitations of the Study:

Significant additional investigation will be needed to define the similarities and differences between these frameworks and other nuclear, and even other mSWI/SNF family subunit, IDRs, particularly given that repertoires of TFs and other IDR-interacting factors expressed among different cell types are highly variable. Further, it remains to be determined whether chemical approaches to disrupt the protein interaction network encoded by the ARID1A/B IDRs, inhibit the DNA-binding domain, or affect the biophysical properties leading to condensate formation may represent viable targeted strategies for specific cancers in which BAF complexes represent synthetic lethal dependencies.

STAR Methods

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Cigall Kadoch (cigall_kadoch@dfci.harvard.edu).

Materials Availability

Cell lines generated in this study will be available upon reasonable request from the Lead Contact.

Data and Code Availability

All genomic data have been deposited on the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus via GSE209961.

No original code was created in this study.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental Models and Study Participant Details

Cell lines and culture conditions

All human and mouse cell lines were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2. HEK293T and U2OS cell lines are female human cells. HEK293T ΔARID1A/B and U2OS cells were grown in DMEM media (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco), 1X GlutaMAX (Gibco), 100 U/mL Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco), 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate (Gibco), 1X MEM NEAA (Gibco), and 10 mM HEPES (Gibco). AN3CA endometrial cancer cells are human female cells and were grown in EMEM media (Gibco) supplemented with 15% tetracycline-free FBS (Omega), 1X GlutaMAX (Gibco), 100 U/mL Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco), 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate (Gibco), 1X MEM NEAA (Gibco), and 10 mM HEPES (Gibco). For immunofluorescence data, U2OS and MDA-MB-231 (human female breast-cancer derived) cells were grown in DMEM media with glucose, glutamine and pyruvate (ThermoFisher) supplemented with 10% FBS (Avantor) and 100 U/mL Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco). KLE (ATCC CRL-1622, human female uterine cell line), C2C12 (ATCC CRL-1772, female mouse myoblast cells) and CRL-7250 male human foreskin fibroblast cells were cultured in the same but with 20% FBS. MCF10A and MCF10-CA human female breast cancer cells were cultured in DMEM:F12 (Gibco 21041025) supplemented with 5% Horse serum (Sigma), 20 ng/mL EGF, 1 μg/mL Hydrocortisone, and 10 μg/mL Insulin. U2OS cell lines were authenticated by STR profiling.

Primary rat neuron dissection and culture

The inner 60 wells of 96 well glass bottom plates were treated with 0.01 mg/mL poly-D-lysine at 37 °C overnight and washed x4 in HBSS. The outer 36 wells of the 96 well plate were filled with ultrapure water. 50 μL of neuron media (Gibco Neurobasal Plus with 2% Gibco B27 Plus, 1% penstrep, and 250 ng/mL Amphotericin B) with 2% Gibco CultureOne supplement (antimitotic) was added to each well, and the plates were stored at 37 °C overnight, 5% CO2. Embryos were collected from euthanized Sprague-Dawley rats (Hilltop Lab Animals Inc.) at embryonic day 17 via caesarian section. The embryos in placentas were transferred to HBSS in 10 cm glass plates. The placenta was cut from each embryo, the heads were removed and transferred to a new glass plate with HBSS. Using a dissection microscope, the skull was removed by making a medial cut from caudal to rostral following the central sulcus using small scissors held parallel to the brain, cutting just the skull layer and not into cortex. Closed scissors were used to get under the brain from the caudal side and gently flip brain out, cutting away any remaining attachment. Brains were transferred to a new glass plate with HBSS. Meninges were carefully and thoroughly removed starting with the ventral side, flipping to dorsal side, removing caudal to rostral along the central sulcus, gently unraveling the cortex from the central sulcus. The cortex was cut away from the striatum and other structures and transferred to a 10 mL conical with HBSS.

Worthington papain dissociation kit was used to dissociate cortices into individual cells in a biosafety cabinet using sterile technique. Reagents were prepared as described by the kit. HBSS was carefully removed from the cortices and 5 mL papain solution was added (100 units papain, 1000 units DNase I, 1 mM L-cysteine, 0.5 mM EDTA in HBSS). The conical was inverted thrice and then incubated at 37 °C for 20 minutes, with no agitation or inversion after the incubation. The papain solution was removed, and 3 mL of inhibitor solution (3 mg ovomucoid inhibitor, 3 mg albumin, and 500 units DNase I in HBSS) was added to the cortices, inverted thrice, and sat upright for 5 min. Supernatant was removed and replaced with 3 mL additional inhibitor solution, inverted thrice, and sat upright for 5 min. Supernatant was removed and 1.5 mL neuron media was added. A flame-treated Pasteur pipette was used to slowly triturate up and down ten times, avoiding bubbles. Cells were allowed to settle in the upright tube for 2 min. The top 750 μL of dissociated cells were removed and added to a new 10 mL conical. 750 μL neuron media was added to the original tube, triturated ten times, settled in the upright tube for 2 min, and the top 750 μL of dissociated cells were transferred to the new 10 mL conical. This process was repeated one more time, for a total of three trituration steps, adding all of the media with cells to the new tube after the final trituration. Cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 300 g, supernatant removed, resuspended in 1 mL neuron media, and counted using a hemocytometer. Cells were diluted in additional neuron media to achieve 25,600 cells in 50 μL per well (80,000 cells per cm2 growing area). 50 μL of diluted cells were added to each well of the previously prepared plates to bring the final volume to 100 μL with 1% CultureOne supplement. CultureOne supplement was not used again after this treatment on day in vitro (DIV) 0. Cells were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2. On DIV3 100 μL more neuron media was added. Every 3–4 days after that, 95 μL media was removed from each well and replaced with 100 μL fresh media and 5 μL ultrapure water to counter evaporation. Neurons were fixed and used for immunofluorescence on DIV11.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses on quantified imaging data was performed with Prism. Statistical details, exact values of n and what n represents (individual cells or biological replicates) for each experiment can be found in the figure legends. In general, p values of significance less than 0.05 are denoted with one asterisk ‘*’, less than 0.01 with two asterisks ‘**’, less than 0.001 with three ‘***’ and less than 0.0001 with four asterisks ‘****’. No outlier data was omitted, no samples were excluded from our analyses. To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) or differentially interacting proteins, t-tests were performed on RNA-sequencing and mass spec data respectively. Error bar representation is indicated in the figure legends.

Method Details

Plasmids, cloning and expression

All ARID1A/B constructs used in this study were HA-tagged at the N-terminus and cloned into a piggybac vector downstream of a Doxycycline-inducible promoter. The vector also contains a separate Tet-On 3G gene and Blasticidin or Puromycin resistance gene cassette separated by a P2A sequence, under the human EF1a promoter. All constructs were sequence verified using Sanger sequencing. Piggybac plasmids were co-transfected with a mammalian expression plasmid carrying a transposase gene cassette in AN3CA using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher) and selected with 10 ug/ml Blasticidin or 2 ug/ml Puromycin 24 h post transfection for 3–5 days. Expression of the transgene was induced by addition of 200 ng/ml Doxycyline for 48 hours. All plasmids used in this study are listed in the STAR Methods section.

Coimmunoprecipitation

cBAF complex coimmunoprecipitation

BAF complex immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously21. Cells were washed with cold PBS and resuspended in EB0 hypotonic buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 0.1% NP-40,1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2 supplemented with protease inhibitors. Lysates were pelleted at 5,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were discarded, and nuclei were resuspended in EB300 high salt buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2 supplemented with protease inhibitors. Lysates were incubated on ice for 10 min with occasional vortexing and then spun at 21000 g for 11 min at 4 °C. 0.5–1 mg of nuclear lysate was used for immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-HA antibody (1:200 v/v) (Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4 °C to bind to HA-tagged ARID1A/B (bait). Protein-G Dynabeads (ThermoFisher) were then added for 2 hours and washed five times with EB300. Protein was eluted from beads with 4X LDS buffer by boiling for 7 min and loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels for Western blotting. Antibodies are listed in the STAR Methods section.

Transcription factor-cBAF complex coimmunoprecipitation

Reciprocal immunoprecipitations to validate cBAF Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry results were performed as follows: Cells were washed with cold PBS and resuspended in EB0 hypotonic buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2 supplemented with protease inhibitors. Lysates were pelleted at 5,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were discarded, and nuclei were resuspended in EB150 salt buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2 supplemented with protease inhibitors. Lysates were incubated on ice for 10 min with occasional vortexing and then spun at 21000 g for 11 min at 4 °C. 1–2.2 mg of nuclear lysate was used for immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-NFIA, rabbit anti-TEAD1, or rabbit anti-cJUN antibodies (1:200 v/v) (Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4 °C. Protein-G Dynabeads (ThermoFisher) were then added for 2 hours. The beads were then extremely gently washed on a magnet three times with EB150 supplemented with protease inhibitors to avoid disrupting low affinity interactions, followed by boiling in 4X LDS buffer for 7–10 min and loading onto SDS-PAGE gels for Western blotting. Antibodies are listed in STAR Methods.

Western blotting

Western blot analysis was performed using a standard protocol. Nuclear extracts were separated using a 4%–12% Bis-Tris PAGE gel (Bolt 4%–12%Bis-Tris Protein Gel, Thermo Fisher) and transferred onto 0.2 μm Nitrocellulose membranes (Biorad) at 400 mA for 2 hours on ice. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in 1X TBST for 30 min at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C (1:2000 v/v for Cell Signaling antibodies, 1:1000 v/v for others). They were then washed thrice with 1X TBST and incubated with near-infrared fluorophore-conjugated species-specific secondary antibodies (LI-COR Biosciences) for 1 hour at room temperature (1:10,000 v/v). Following secondary antibody incubation, membranes were washed twice with 1X TBST, once with 1X TBS, and imaged using a Li-Cor Odyssey CLx imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences).

ATAC-seq

Omni-ATAC protocol was used to measure DNA accessibility with slight modifications covered below91. 100,000 cells per sample were trypsinized and washed with cold PBS to remove trypsin. Cell pellets were lysed in 50 μL cold resuspension buffer (RSB) supplemented with fresh NP40 (final 0.1% v/v), Tween-20 (final 0.1% v/v), Digitonin (final 0.01% v/v) (RSB recipe: 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, and 3 mM MgCl2). Lysis step was quenched with 1 mL of RSB supplemented with Tween-20 (final 0.1% v/v) and nuclei were pelleted at 500 g for 10 min at 4 °C after incubating on ice for 3 minutes. Nuclei were then resuspended in 50 μL transposition reaction mix containing 25 μL 2X Tagment DNA buffer (Illumina), 2.5 μL Tn5 transposase (Illumina), 16.5 μL 1X PBS, 0.5 μL 1% digitonin (final 0.01% v/v), 0.5 μL 10% Tween-20 (final 0.1% v/v), and 5 μL nuclease-free water. The transposition reaction was °C for 30 min with constant shaking (1000 rpm) on a thermomixer. Tagmented DNA was purified using the MinElute Reaction Cleanup Kit (Qiagen). Standard ATAC-seq amplification protocol with 7 cycles of amplification was used to amplify tagmented libraries45. Libraries were sequenced on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina) using 37 bp pair-end sequencing.

CUT&Tag

CUT&Tag was performed as described previously62 using a protocol developed by Epicypher (https://www.epicypher.com/content/documents/protocols/cutana-cut&tag-protocol.pdf) in 8-strip PCR tubes with slight modifications as described below. Briefly, Concanavalin A (ConA) coated magnetic beads (Polysciences) were activated with Bead Activation Buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MnCl2; beads were stored on ice until used. 300,000 cells/sample were trypsinized and pelleted by centrifugation at room temperature (600g for 3 min). Cells were lysed using cold Nuclear Extraction Buffer containing 20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 20% Glycerol supplemented with fresh 0.5 mM Spermidine and 1X protease inhibitor (Roche) for 2 min. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation (600 g for 3 min), resuspended in 100 ul/sample Resuspension buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl supplemented with fresh 0.5 mM Spermidine and 1X protease inhibitor) and incubated with activated ConA beads at room temperature for 15 min. The nuclei-ConA bead complexes were then resuspended in Antibody 150 Buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA supplemented with fresh 0.5 mM Spermidine, 1X protease inhibitor, 0.01% Digitonin, and 0.5 ug primary antibody/sample. Following overnight incubation at 4°C on a nutator, supernatant was discarded, and the ConA-nuclei complexes were then incubated with Digitonin 150 buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM Spermidine, 1X protease inhibitor, 0.01% Digitonin) supplemented with 0.5 ug/sample Secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature on a nutator. They were then washed with Digitonin 150 Buffer twice before resuspension in 50 μL cold Digitonin 300 Buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM Spermidine, 1X protease inhibitor, and 0.01% Digitonin. 2 μL CUTANA pAG-Tn5 (Epicypher) was added to each sample and incubated on a nutator for 1 hr at room temperature. Following incubation, beads were washed twice with cold Digitonin 300 Buffer. Targeted chromatin tagmentation and library amplification were carried out according to Epicypher’s protocol mentioned above. Size distribution was measured on a D1000 ScreemTape run on a TapeStation 2200 (Agilent). Equimolar amounts of barcoded libraries were pooled and sequenced on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina) using 37 bp pair-end sequencing with the goal of achieving a minimum of 8–10 million reads per library.

CUT&RUN

CUT&RUN was performed based largely on Epicypher’s protocol (https://www.epicypher.com/content/documents/protocols/cutana-cut&run-protocol.pdf) and the CUT&Tag protocol described above but with key modifications as described below. Briefly, Concanavalin A (ConA) coated magnetic beads (Polysciences) were activated with Bead Activation Buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MnCl2; beads were stored on ice until used. 500,000 cells/sample were trypsinized and pelleted by centrifugation at room temperature (600 g for 3 min). Cells were lysed using cold Nuclear Extraction Buffer containing 20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 20% Glycerol supplemented with fresh 0.5 mM Spermidine and 1X protease inhibitor (Roche) for 2 min. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation (600 g for 3 min), resuspended in 100 ul/sample Resuspension buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl supplemented with fresh 0.5 mM Spermidine and 1X protease inhibitor) and incubated with activated ConA beads at room temperature for 15 min. The nuclei-ConA bead complexes were then resuspended in Antibody 150 Buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA supplemented with fresh 0.5 mM Spermidine, 1X protease inhibitor, 0.01% Digitonin, and 0.5 ug primary antibody/sample. Following overnight incubation at 4 °C on a nutator, the supernatant was discarded, and the ConA-nuclei complexes were then washed twice with Digitonin 150 buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM Spermidine, 1X protease inhibitor, 0.01% Digitonin). They were then resuspended in Digitonin 150 buffer and 2.5 μL of CUTANA pAG-MNase (Epicypher) was added to each sample followed by incubation on a nutator for 30–60 min. The supernatant was then discarded and the ConA-nuclei complexes were washed twice with Digitonin 150 buffer and resuspended in fresh Digitonin 150 buffer supplemented followed by addition of 1 μL of 100 mM CaCl2 to each sample. The samples were then incubated on a nutator for 2 hours at 4 °C, followed by addition of the Stop buffer (340 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 4 mM EGTA, 50 ug/mL RNase A, 50 ug/ml Glycogen). Samples were then incubated at 37 °C for 10 minutes to release MNase-digested DNA fragments. The supernatants were then transferred to a new tube and DNA was purified using the MinElute Reaction Cleanup Kit (Qiagen). Libraries were prepared using the CUTANA CUT&RUN Library Prep Kit (Epicypher). Size distribution was measured on a D1000 ScreemTape run on a TapeStation 2200 (Agilent). Equimolar amounts of barcoded libraries were pooled and sequenced on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina) using 37 bp pair-end sequencing with the goal of achieving a minimum of 8–10 million reads per library.

NGS Data Processing

CUT&Tag, CUT&RUN, ATAC-Seq, and RNA-Seq samples were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq500 instrument. RNA-Seq reads were aligned to the hg19 genome with STAR v2.5.2b77, and tracks were generated using the deepTools v2.5.3 bamCoverage function78 with the normalizeUsingRPKM parameter. Output gene count tables from STAR were used as input into the edgeR v3.12.1 R software package77,80 to evaluate differential gene expression. For ATAC-Seq data, read trimming was carried out by Trimmomatic v0.3681, followed by alignment, duplicate read removal, and read quality filtering using Bowtie282, Picard v2.8.0 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/), and SAMtools v 0.1.1983, respectively, and ATAC-seq peaks were called with MACS2 v2.184 using the BAMPE option and a broad peak cutoff of 0.001. For ATAC-Seq track generation, output BAM files were converted into BigWig files using MACS2 and UCSC utilities92 in order to display coverage throughout the genome in RPM values. For CUT&Tag and CUT&RUN libraries, the CutRunTools pipeline was leveraged to perform read trimming, quality filtering, alignment, peak calling, and track building using default parameters85. All sequencing data analyzed in this study have been deposited at NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE209961.

CUT&Tag, CUT&RUN and ATAC-seq data analyses

Heatmaps and metaplots displaying signals aligned to peak centers were generated using ngsplot v2.6386. RPM values were quantile normalized across samples, and K-means clustering was applied to partition the data into groups. The Bedtools multiIntersectBed and merge functions were used for peak merging79, and distance-to-TSS peak distributions were computed utilizing Ensembl gene coordinates provided by the UCSC genome browser. Principle Component Analysis was performed using the wt.scale and fast.svd functions from the corpcor R package on CUT&Tag/CUT&RUN quantile normalized log2-transformed RPKM values within merged peaks87,88. Transcription factor motif enrichment analyses were carried out by the HOMER v4.9 93 software.

cBAF complex purification

mSW/SNF complex purification was performed essentially as described previously21,41. Briefly, HEK293TARID1A/B knock-out cells stably expressing HA-tagged ARID1A WT or mutants under a doxycycline-inducible promoter created using piggybac transfection (described above) were plated in 50–100 15-cm plates. Expression of the bait (HA-ARID1A) was induced by addition of 200 ng/ml Dox for 48 hours. Cells were then scraped from plates, washed with cold PBS, and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. Pellets were resuspended in hypotonic buffer (HB: 10 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, supplemented with 1 mM DTT and 1 mM PMSF) and incubated for 5 min on ice.

The suspension was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, and pellets were resuspended in 5 volumes of HB containing protease inhibitor cocktail. The suspension was then homogenized using a glass Dounce homogenizer (Kimble Kontes). Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. Nuclear pellets were resuspended in high salt buffer (HSB: 50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2,1mM EDTA, 1% NP40 supplemented with 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, and 1X protease inhibitor cocktail). The homogenate was then incubated on a rotator for 1 hr at 4 °C followed by centrifugation at 20,000 rpm for 1 h at 4 °C using a SW32Ti rotor in an ultracentrifuge. The high salt nuclear extract supernatant was filtered through a 5 μm filter (EMD Millipore) and incubated with Pierce Anti-HA Magnetic Beads (Thermo Fisher) overnight at 4 °C. HA beads were washed 6 times in HSB and eluted with HSB containing 2 mg/mL of HA peptide (GenScript) for four elutions of 2 h each followed by one overnight elution. Eluted proteins were then subjected to dialysis (Slide-A-Lyzer MINI Dialysis Device, 10K MWCO, ThermoFisher) using Dialysis Buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 15% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT) overnight at 4 °C, and finally concentrated using Amicon Ultracentrifugal filters (30kDa MWCO, EMD Millipore). Complexes were aliquoted, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

In vitro condensation assay

Purified cBAF complexes containing C-terminally eGFP-tagged ARID1A WT, DBDmut, ΔIDR1 or CBR were stored in 25 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA, 100 mM KCl,1 mM MgCl2,15% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT, at −80 °C. Reaction chambers for the in vitro assay were prepared by coating the interior glass of a 96-well glass bottom plate (Cellvis, P96–1.5H-N) with 1% w/v PF-127 (Pluronic F-127, ThermoFisher, P3000MP) for 15 minutes. Unused wells were filled with distilled water to maintain humidity in the nearby reaction chambers and prevent sample evaporation. Protein complexes were thawed on ice, then diluted to four concentrations (2, 0.66, 0.22, 0.074 μM) in physiological salt buffer (150 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5) in 4 μL reaction volume. For assays containing DNA, nucleosomes, or RNA, each reaction additionally contained 100 ng/μL DNA, 100 ng/μL nucleosomes, or 100 ng/μL RNA. Source of DNA was a linearized double-stranded 10 kb plasmid of random sequence. Nucleosomes were mono- di- and tri-nucleosomes purified from HeLa cells (Epicypher). Source of RNA was in vitro transcribed 18s rRNA from HEK293T cell cDNA (ThermoFisher). Reactions were allowed to equilibrate at room temperature for 30 min for droplets to form and settle onto the coverslip. Visualization of the reaction chambers was performed on a spinning-disk confocal microscope (Yokogawa CSU-X1) with 100X oil immersion Apo TIRF objective (NA 1.49) and Andor DU-897 EMCCD camera on a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope body. Images were obtained in DIC (Differential Interference Contrast) and GFP (488 nm laser) channels; at least 6 fields of view per sample were gathered. For quantification, images were deidentified, segmented for droplets in the GFP channel using FIJI90, and droplet area measured. ‘Percent Area’ metric was calculated for each image as the area in microns squared covered by droplets over the area in microns square of the entire field of view.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP)

FRAP assays were performed in AN3CA patient-derived endometrial cells with doxycycline-inducible expression of C-terminally eGFP-tagged ARID1A or ARID1B constructs. Cells were plated in 24-well glass bottom plates (Cellvis) 48 hours prior to imaging. Expression was induced 24 hours prior to imaging by exchanging for media with 200 ng/mL doxycycline (Fisher Scientific). Cells were imaged on a Nikon Ti2 microscope equipped with an A1R HD25mm scanhead, with Plan Apo λ 1.4 NA oil lens, maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 with a Tokai Hit Stagetop incubator equipped with a Ti ZWX stage insert. Images were obtained with 0.1–0.8 % laser power 488 nm with 10–70 HU gain at 11.11X zoom, 1 AU pinhole, 256×256 pixels each 0.0625 μm. Three pre-bleach images were acquired, then bleaching was performed with the 488 laser at 10% power. Post-bleach images acquired every 0.25 seconds for the first 10 seconds, every 1 sec for the next 20 sec, then every 5 sec for the next 2 minutes. For each construct, three biological replicates were prepared, and at least 15 cells bleached per replicate. For quantification, movies were registered using StackReg plugin in FIJI94, bleached area recognized by segmentation, then intensity of the bleached area in each frame measured. Measurements were normalized by subtracting the background (nucleoplasmic) intensity, then dividing over the average pre-bleach intensity from three pre-bleach images.

Live time-lapse movies

AN3CA cells expressing ARID1A-WT-eGFP, ARID1A-DBDmut-eGFP, ARID1B-WT-eGFP or ARID1B-DBDmut-eGFP were prepared on the Nikon Ti2 microscope with A1R scanhead and Tokai Hit Stagetop incubator as described above. Images were obtained with 0.1–0.8% laser power 488 nm with 10–70 HU gain at 4X zoom, 1Au pinhole, 512×512 pixels. Images were obtained every 20 seconds for 60 minutes to observe long-term stability of condensates, or every 5 seconds for 10 minutes to observe fusion and coalescence of nuclear puncta.

Immunofluorescence

AN3CA cells were plated in 24-well glass bottom plates at 50% confluency (Cellvis) 48 hours prior to fixation, and expression induced 24 hours prior to fixation by adding 200 ng/mL doxycycline (Fisher Scientific). Cells were washed once with DPBS, then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (diluted in DPBS from 16% paraformaldehyde, Electron Micrsocopy Science #15710) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Fixed cells were washed three times, five minutes each in room temperature DPBS, then permeabilized in 0.2% PBST (Triton X-100, ThermoFisher) for 60 minutes with rocking. Permeabilized cells were washed again three times, five minutes each in room temperature DPBS, then blocked in 0.1% PBST with 5% goat serum (Vector Laboratories S-1000–20) + 5% BSA for 60 minutes with rocking. Cells were stained with primary antibody in block overnight at room temperature with rocking (1:500 rabbit mAb anti-p300; 1:500 rabbit mAb anti-SMARCC1; 1:1000 rabbit mAb anti-ARID1A or 1:1000 rabbit mAb anti-ARID1B). Cells were washed three times, five minutes each with DPBS, then stained with secondary antibody (1:5000 Goat anti-rabbit highly cross-adsorbed 568-conjugated antibody) for 3 hours with rocking at room temperature. This antibody staining protocol was developed to faithfully recognize condensates in exogenous ARID1A WT-eGFP-expressing AN3CA cells, then applied to the additional panel of cell types (KLE, CRL-7250, MDA-MB-231, MCF10A, MCF10-CA, C2C12 mouse myoblasts and primary rat cortex neurons). All antibodies are listed in the STAR Methods.

Saturation Concentration Measurement

Microscope fluorescence intensity to concentration calibration