Abstract

To address the need for improved biomarkers for kidney transplant rejection, European Society of Organ Transplantation (ESOT) convened a dedicated working group comprised of experts in kidney transplant biomarkers to review literature pertaining to clinical and subclinical acute rejection to develop guidelines in the screening and diagnosis of acute rejection that were subsequently discussed and voted on during the Consensus Conference that took place in person in Prague. The findings and recommendations of the Working Group on Molecular Biomarkers of Kidney Transplant Rejection are presented in this article.

Keywords: biomarkers, kidney transplant, rejection, non-invasive, diagnostics, gene expression, cell-free DNA, urine chemokines

Introduction

The short- and long-term success of kidney transplants relies on the safe and effective prevention of allograft rejection. Monitoring the alloimmune response to the kidney graft has been done for decades by serial measurements of graft function (non-invasive measuring of serum creatinine) and immunosuppressive drug levels and employing both reactive “for-cause” and systematic “surveillance” allograft biopsies. Monitoring serum creatinine has been demonstrated to be an insensitive and lagging indicator of allograft rejection and injury [1–4] and immunosuppressive drug level monitoring may inform efficacy for groups of patients but is not suited to individual rejection monitoring outside the extremes [5]. Thus, there is a significant unmet need for a more sensitive and specific non-invasive monitoring tool for allograft rejection and the adequacy of immunosuppression that can reduce or eliminate the need for surveillance biopsies and inform the need for indicated biopsies.

The target population for improved non-invasive tests for rejection would include all patients with a functioning kidney transplant. While rates of clinical and subclinical rejection are highest in the first 2 years post-transplant, possibly due to detection bias, patients are always at risk of alloimmune graft injury if they are functionally under-immunosuppressed, regardless of the cause. The non-invasive biomarkers addressed in this review have been introduced into clinical practice around the world in various combinations and at various times throughout the transplant patient journey. The goal of this review is to provide a snapshot of the current published evidence for their use and to provide a roadmap for the future development and implementation of these technologies.

To address the need for evidence-based guidelines for the adoption of molecular biomarkers in kidney transplantation, ESOT convened a consensus conference, comprised of a global panel of experts to develop guidelines on key aspects of non-invasive biomarkers of rejection. Summaries of the evidence were presented to the entire group of panelists and juries. The consensus findings and recommendations of the ESOT Consensus guidelines on molecular biology testing for non-invasive diagnosis of kidney allograft rejection are presented in this document. This document, which will be updated to reflect new evidence as it becomes available, is intended for healthcare providers.

Methods

The consensus development process was organized by a dedicated Guidelines Taskforce within ESOT and its sections ELITA, EKITA, EPITA, ECTTA, ETHAP, Education Committee, YPT, Transplant International editorial board members and patient representatives. The detailed description of the methodology used is reported previously [6].

Briefly, key issues related to the topic of non-invasive biomarkers for kidney transplant rejection were identified by each working group and specific clinical questions were formulated according to the PICO methodology (PICO = Population, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome). All PICO questions are listed in subsequent sections of the manuscript. Following the definition of the PICOs, literature searches were developed by expert staff from the CET who have expertise in conducting systematic reviews and subsequently integrated, when needed, by the steering committee experts.

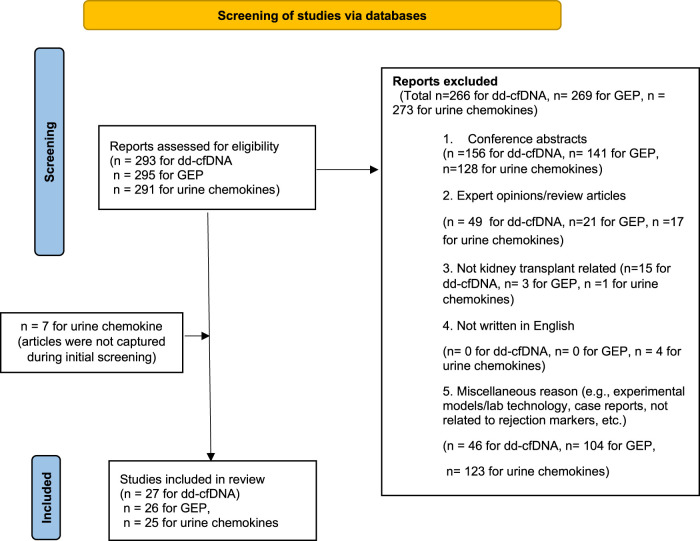

A PRISMA flowchart describing the number of studies identified by the literature search and the number of studies selected for inclusion in the consensus statement appears in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart summarizing the selection process of studies included in the evaluation of biomarkers for rejection in kidney transplantation. Modified figure from: [38]. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

A summary of the key evidence addressing each key question by the included studies was prepared in evidence Tables 1–5. The primary studies are included in these tables. Additional studies reviewed but not included in the manuscript are included in Supplementary Appendix SA. The workgroup proposed a recommendation for each key question based on the quality of evidence rated using the GRADE approach, with high quality rated as A, medium quality as B, and low quality as C; very low quality of evidence was not considered. For evaluation of the quality of evidence according to GRADE [33], the following features were considered: study design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, number of patients, effect, importance, and publication bias. The strength of recommendation was rated as 1 (strong) or 2 (weak).

TABLE 1.

Summary of key literature reviewed on donor-derived cell-free DNA for subclinical rejection.

| Authors | Study design | Number of samples | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | Retrospective analysis on biorepository samples, Single center | 114 biopsies | For any subAR (AUROC 0.89, PPV 0.55, NPV 0.97) |

| 13 rejections | |||

| 101 no rejection | |||

| [7] | Prospective observational (post hoc analysis), Multicenter | 428 biopsies | For any subAR (AUROC 0.72, PPV 0.56, NPV 0.84) |

| 103 rejections | |||

| 325 no rejection | |||

| [8] | Retrospective cross-sectional, Single center | 37 biopsies | For any subAR (sensitivity 0, specificity 0.89, PPV 0, NPV 0.71) |

| 10 rejections | |||

| 27 no rejection |

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; subAR, subclinical rejection; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

TABLE 5.

Summary of literature review on urine chemokines for clinical acute rejection.

| Authors | Study design | Number of samples | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | Retrospective analysis, CXCL10, Single center | 102 biopsies | For TCMR (cAR + subAR, excluding BL) vs. normal (AUROC 0.87) |

| 34 AR | |||

| 22 normal | |||

| [30] | Prospective analysis, CXCL9 and CXCL10, Multicenter | 337 biopsies | For AR (cAR + subAR, excluding BL) versus no rejection |

| 45 AR | (CXCL9 AUROC 0.86; CXCL10 AUROC 0.77) | ||

| 228 no rejection | |||

| [31] | Retrospective analysis, CXCL9 and CXCL10, Single center | 281 biopsies | For clinical AR (excluding subAR and BL) versus no rejection |

| 78 AR | (CXCL9 AUROC 0.71; CXCL10 AUROC 0.76) | ||

| 203 no rejection | |||

| [27] | Prospective analysis, CXCL9 and CXCL10, Single center | 1722 samples | For clinical AR (excluding subAR and BL) versus no rejection |

| 743 biopsies | |||

| 60 AR | (CXCL9 AUROC 0.72; CXCL10 AUROC 0.74) | ||

| 243 no rejection | |||

| [28] | Retrospective analysis, CXCL9 and CXCL10, Multicenter | 373 biopsies | For AR (cAR + subAR, excluding BL) vs. no rejection (multiparametric model including CXCL9 and CXLC10 AUROC 0.85) |

| 90 AR | |||

| 283 no rejection | |||

| [29] | Retrospective analysis, CXCL10, Single center | 151 biopsies | For scTCMR versus normal (ABMR AUROC 0.76; TCMR AUROC 0.72) |

| 52 ABMR | |||

| 36 TCMR | |||

| 99 no ABMR | |||

| 115 no TCMR | |||

| [32] | Retrospective analysis, CXCL10, Single center | 182 biopsies | For late clinical AR (excluding subAR and BL) versus normal (AUROC 0.72) |

| 55 AR | |||

| 98 no rejection |

ABMR, antibody-mediated rejection; AR, acute rejection; AUROC, area under the ROC curve; BL, borderline rejection; cAR, clinical acute rejection; subAR, subclinical acute rejection; TCMR, T cell-mediated rejection.

TABLE 2.

Summary of key literature reviewed on donor-derived cell-free DNA for clinical acute rejection.

| Authors | Study design | Number of samples | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | Prospective observational, Multicenter | 107 biopsies | For any rejection (AUROC 0.74, PPV 0.61, NPV 0.84) |

| 27 rejections | |||

| 80 no rejection | |||

| [10] | Subgroup analysis of prospective observational, Multicenter | 87 patients | For ABMR with + DSA and dd-cfDNA >1%, (AUROC 0.86, PPV 0.81, NPV 0.83] |

| 16 ABMR | |||

| 53 no rejection | |||

| [2] | Retrospective analysis of biorepository samples, Single center | 217 biopsies | For any rejection for cause + SubAR (AUROC 0.87, PPV 0.52, NPV 0.95) |

| 38 rejections | |||

| 179 no rejection | |||

| [11] | Prospective observational, Single center | 63 biopsies | For any rejection (AUROC 0.71, PPV 0.77, NPV 0.75) |

| 34 rejections | |||

| 29 no rejection | |||

| [12] | Prospective observational, Single center | 189 patients | For any rejection (Absolute concentration of dd-cfDNA (AUROC 0.83) is better than dd-cfDNA (%) (AUROC 0.73) |

| 22 rejections | |||

| 395 stable samples | |||

| [13] | Prospective cross-sectional, Multicenter (n = 2) | 61 biopsies | For ABMR (absolute concentration AUROC 0.91 vs. dd-cfDNA (%) 0.89) |

| 13 ABMR | |||

| 48 no rejection | |||

| [14] | Subgroup analysis of prospective observational, Multicenter | 79 patients with TCMR 1A/borderline changes | Subjects with TCMR (1A and borderline) with high dd-cfDNA had worse clinical outcomes compared to those with low dd-cfDNA |

| [15] | Cross-sectional for DSA screening/Retrospective testing of dd-cfDNA on bio-banked samples, Single center | From 2 independent cohort | For ABMR with +DSA |

| 45/30 biopsies | AUROC for dd-cfDNA alone 0.89/0.69 | ||

| 25/17 ABMR | AUROC for DSA alone 0.88/0.77 | ||

| 20/13 no ABMR | |||

| [3] | Prospective observational, multicenter (ADMIRAL) | 219 biopsies | For any rejection dd-cfDNA (AUROC 0.8, PPV 0.5, NPV 0.9) |

| 113 rejections | |||

| 106 no rejection | |||

| [16] | Prospective observational, Single center | 208 biopsies | For any rejection dd-cfDNA and MMDx (AUROC 0.80), dd-cfDNA and histology (AUROC 0.75) |

| 162 rejections by histology | |||

| 46 no rejection by histology | |||

| [17] | Prospective observational, multicenter (TRIFECTA) | 300 biopsies | dd-cfDNA levels are strongly associated with the active molecular rejection phenotype (MMDx), particularly with AMR, mixed, and active TCMR |

| 120 rejections | |||

| 180 no rejection | |||

| [18] | Prospective observational, multicenter (TRIFECTA) | 367 biopsies | Any rejection prediction AUROC in test set by logistic regression model using both dd-cfDNA (%) and absolute concentration |

| 83 (histology test set) rejection | • 0.88 for MMDx | ||

| 71 (MMDx test set) rejection | • 0.82 for histologic rejection |

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; DSA, donor-specific antibody; MMDx, the molecular microscope diagnostic system; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

TABLE 4.

Summary of key literature reviewed on urine chemokines for subclinical acute rejection.

| Authors | Study design | Number of samples | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | Retrospective analysis, CXCL10, Single center | 102 biopsies | For scTCMR (including BL) versus normal (AUROC 0.85; OR 1.41) |

| 30 subAR | |||

| 22 normal | |||

| [26] | Retrospective analysis, CXCL10, Single center | 362 biopsies | For subAR (including BL) versus no rejection (AUROC 0.69) |

| 119 subAR | |||

| 243 no rejection | |||

| [27] | Prospective longitudinal analysis, CXCL9 and CXCL10, Single center | 1722 samples | For subAR (excluding BL) |

| 743 biopsies | versus no rejection | ||

| 50 subAR | (CXCL9 AUROC 0.57; CXCL10 AUROC 0.64) | ||

| 243 no rejection | |||

| [28] | Retrospective analysis, CXCL9 and CXCL10, Multicenter | 373 biopsies | For subAR (excluding BL) |

| 45 subAR | versus no rejection | ||

| 283 no rejection | (multiparametric model including CXCL9 and CXLC10 AUROC 0.81) | ||

| [29] | Retrospective analysis, CXCL10, Single center | 151 biopsies | For scTCMR versus no rejection (scABMR AUROC 0.80; scTCMR AUROC 0.78) |

| 23 scABMR | |||

| 15 scTCMR | |||

| 99 no ABMR | |||

| 115 no TCMR |

AUROC, area under the ROC curve; subAR, subclinical rejection; BL, borderline rejection; scABMR, subclinical antibody-mediated rejection; scTCMR, subclinical; T cell-mediated rejection.

Complete information including the list of consensus conference workgroup domains (and topics noted below), and process regarding consensus conference participant selection, development and refinement of consensus statements, and modified Delphi methodology including consensus polling, are previously reported in beforehand the in-person conference held in Prague, Czech Republic, 13–15 November 2022 [6].

Overarching Statements From the Working Group

1. The majority of reviewed studies were conducted in adult patients; therefore, our recommendations are most applicable to the adult population. Our group acknowledged, however, that noninvasive biomarkers of rejection would be of great value in the care of pediatric kidney transplant recipients. Thus, we strongly encourage further study and development of these tests in the pediatric population. There are initial studies suggesting the potential utility of such monitoring in pediatric patients [34–36].

2. All of these diagnostic tests are not necessarily alloimmune-specific and thus, may be affected by sources of many other non-alloimmune inflammation such as infections and should be interpreted in that context.

3. Cost-benefit analyses were not considered in the forming of these statements but deserve further study.

4. All of these biomarker tests are available on more than one platform, but a paucity of head-to-head comparisons do not permit specific recommendations for one technique or specific test with a given technology (e.g., cell-free DNA) over another.

5. Most of these tests do not have validated cut-offs to interpret their output in a binary manner (high versus low-risk); therefore, the suggested threshold values should be taken with caution and their interpretation as a continuous variable may further help to translate the biological perturbation into a plausible clinical scenario.

Results

Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA (dd-cfDNA)

Question 1

In kidney transplant patients with stable graft function, is plasma dd-cfDNA measurement a reliable diagnostic tool for subclinical acute rejection monitoring when compared with standard of care (eGFR/creatinine monitoring or surveillance biopsy)?

Recommendation 1.1 - We suggest that clinicians consider measuring serial plasma dd-cfDNA in patients with stable graft function to exclude the presence of subclinical antibody-mediated rejection.

Quality of Evidence - Moderate

Strength of Recommendation - Weak in Favor

Comment to Recommendation 1.1

Concomitant testing for donor-specific HLA and non-HLA antibodies along with plasma dd-cfDNA may further increase the ability to detect the presence of antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR). Screening with dd-cfDNA alone does not appear to be a reliable tool for the detection of subclinical T-cell-mediated rejection (TCMR). Combining this test with other non-invasive biomarker technologies (gene expression profiling) may improve the detection of subclinical TCMR. The optimal timing and frequency of screening have not been established.

Question 2

In kidney transplant patients with acute allograft dysfunction, is plasma dd-cfDNA measurement a reliable diagnostic tool for acute rejection monitoring when compared with standard of care (eGFR/creatinine monitoring or for cause biopsy)?

Recommendation 2.1 - We recommend that clinicians measure plasma dd-cfDNA in patients with acute graft dysfunction to exclude the presence of rejection, particularly antibody-mediated rejection.

Quality of Evidence - Moderate.

Strength of Recommendation – Moderate in Favor.

Comment to Recommendation 2.1

Concomitant testing for donor specific HLA and non-HLA antibodies along with plasma dd-cfDNA may further increase the ability to detect the presence of ABMR. Low levels of dd-cfDNA do not necessarily exclude the presence of TCMR in the graft.

Analytical Considerations Regarding dd-cfDNA

Currently, the donor-derived fraction of cell-free DNA is the standard measurement. Some groups have advocated for using both the fraction of dd-cfDNA and the total quantity of dd-cfDNA to improve the detection of clinical acute rejection.

Additionally, all dd-cfDNA assays in the US are currently being run in one of several central/reference labs (currently 3 commercially available assays that vary in the technique and number of single nucleotide polymorphisms analyzed). We recommend further studies to compare the available dd-cfDNA assays head-to-head to better define their performance compared to each other.

Different methodologies involving the assay being run in individual hospital labs used in Europe may require further validation for clinical correlation.

Blood Gene Expression Profiling

Question 3

In kidney transplant patients with stable graft function, is blood gene expression profiling (GEP) a reliable diagnostic tool for subclinical acute rejection monitoring when compared with standard of care (eGFR/creatinine monitoring or surveillance biopsy)?

Recommendation 3.1 - We do not yet recommend implementing the use of blood GEP to diagnose or exclude the presence of sub-clinical rejection.

Quality of Evidence – Low to Moderate.

Strength of Recommendation – Weak against.

Comment to Recommendation 3.1

Most of the published studies reviewed focused on using blood GEP in the setting of screening for subclinical rejection. Multiple GEP tests with differential performance were reviewed and detailed in Table 3. We strongly advocate the need to develop independent, prospective studies using GEP in stable patients to provide more robust evidence of its value to safely avoid surveillance biopsies.

TABLE 3.

Summary of literature review on GEP for clinical and subclinical acute rejection.

| Authors | Study design | Biomarker | Number of samples | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [4] | Multicenter; multiple biorepository retrospective validation sets | 17 gene signatures | 237 | For subAR (including BL) vs. No rejection. AUROC 0.83, NPV 0.89; PPV 0.73 |

| RNA seq (Tuteva) | 46 subAR | For AR (including BL) sets vs. No rejection AUROC 0.81–0.97 (in biorepository validation sets) | ||

| 145 No rejection | ||||

| [1] | Multicenter prospective, internal validation for discovery and validation sets | 57 gene signature Microarray/qPCR (120 genes) (TruGraf) |

382 143 subAR 239 stable |

For subAR (including BL) vs. Stable. AUROC 0.85 NPV 0.88/PPV 0.61 |

| [7] | Post-hoc analysis from a prospective observational | Combined | 408 | For subAR (including BL) vs. Stable AUROC 0.75, NPV 0.82, PPV 0.47 |

| TruGraf + dd-cfDNA | 103 subAR | |||

| 325 stable | ||||

| [19] | Multicenter with external retrospective sample validation | 23 gene signature RNA seq (Clarava) | 155 | For AR (mostly subAR + cAR including BL) vs. No rejection AUROC 0.74, NPV 0.88, PPV 0.70 |

| For discovery set: 32 AR (cAR + subAR) | ||||

| 49 no rejection | ||||

| [20] | Multicenter prospective, internal validation for discovery and validation sets | 13 12-gene signature/RT-PCR fluidigm (kSORT) | 558 | For AR (subAR and cAR including BL) vs. No rejection AUROC 0.95; Sen 0.92, Spec 0.93 |

| 187 AR (cAR + subAR) | ||||

| 371 No rejection | ||||

| [21] | Multicenter validation cohort | 17-gene rt-PCR (kSORT) | 1763 | For AR (cAR +subAR including BL) vs. No rejection AUROC 0.51 |

| 188 AR (cAR +subAR) | ||||

| 1575 No rejection | ||||

| [22] | Multicenter retrospective, internal validation for discovery and validation sets | 5-gene signature RT-PCR/RNAseq (Allomap kidney) | 191 | For AR (cAR +subAR) vs. stable AUROC 0.78 |

| 47 AR (cAR +subAR) | NPV 0.9–0.95, PPV 0.23–0.48 | |||

| 146 stable | ||||

| [23] | Multicenter, prospective validation cohort | 5-gene signature RT-PCR/RNA seq (Allomap kidney) | 235 | For AR (clinical and subclinical) vs. stable Sen 0.7, Spec 0.66 NPV 0.95 |

| 66 AR | ||||

| 169 stable | ||||

| [24] | Multicenter prospective, internal validation for discovery and validation sets | 8-gene signature | 384 | For ABMR (cAR +subAR) vs. no ABMR AUROC 0.80 NPV 0.96, PPV 0.26 |

| RT-PCR/RNAseq | 186 ABMR (cAR +subAR) | |||

| 248 no ABMR |

ABMR, antibody-mediated rejection; AR, acute rejection; AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; BL, borderline; cAR, clinical acute rejection; subAR, subclinical acute rejection; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; Sen, sensitivity; Spec, specificity.

Question 4

In kidney transplant patients with acute allograft dysfunction, is blood gene expression profiling (GEP) a reliable diagnostic tool for clinical acute rejection monitoring when compared with standard of care (eGFR/creatinine monitoring or for cause biopsy)?

Recommendation 4.1 - We do not yet recommend the use of blood GEP to diagnose or exclude the presence of acute graft rejection in patients with acute allograft dysfunction.

Quality of Evidence – Low.

Strength of Recommendation – Weak against.

Comment to Recommendation 4.1

We strongly advocate the need to develop independent, prospective studies using GEP in the setting of graft dysfunction, to provide more robust evidence of its value to safely avoid or inform for-cause biopsies.

Analytical Considerations Regarding Gene Expression Profiling

Multiple research studies have investigated the value of blood GEP in stable patients to diagnose the presence of immune-mediated graft injury, regardless of the type of rejection. The aim of these biomarkers relies on trying to avoid unnecessary kidney allograft biopsies (for cause or for surveillance).

Blood GEP tests are all individual in their performance based on their initial derivation (cohort of patients, context of use), panel of specific genes, and locked classifier algorithm to interpret those genes. Therefore, different gene expression tests cannot be grouped together to analyze their performance.

Some studies have suggested that a combination of biomarkers (GEP with dd-cfDNA or functional cellular assays) may increase their predictive value [7], therefore such studies should be also considered and further validated.

Urinary Chemokines

Question 5

In kidney transplant patients with stable allograft function, is urine chemokine measurement a reliable diagnostic tool for subclinical acute rejection monitoring when compared with standard of care (eGFR/creatinine monitoring or surveillance biopsy)?

Recommendation 5.1 - We suggest the monitoring of a combination of urine CXCL9 and CXCL10 in stable patients to exclude subclinical rejection (TCMR or ABMR).

Quality of Evidence – Moderate.

Strength of Recommendation – Weak in Favor.

Comment to Recommendation 5.1

Use of this test in stable patients may help avoid the need for surveillance biopsies.

Question 6

In kidney transplant patients with acute allograft dysfunction, is urinary chemokine measurement a reliable diagnostic tool for clinical acute rejection monitoring when compared with standard of care (eGFR/creatinine monitoring or for-cause biopsy)?

Recommendation 6.1 - We recommend the measurement of urinary chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10 to inform the presence or absence of clinical acute rejection (TCMR or ABMR) in patients with graft dysfunction.

Quality of Evidence – Moderate.

Strength of Recommendation – Moderate in Favor.

Comment to Recommendation 6.1

None.

Analytical Considerations Regarding Urine Chemokine Profiling

Major strengths for urinary chemokine-based tests are the direct link between the biomarker and the underlying pathological mechanism, the reliance on multiple measurements in some longitudinal studies, and across different populations (American, European, Asian). Additionally, urinary chemokines are highly stable in urine samples.

Similar to dd-cfDNA platforms, some limitations for urinary chemokine-based predictions include the variable cutoffs according to different measurement techniques. We recommend further study to compare these tests across different platforms and to develop standardize thresholds.

A first randomized clinical trial by P. Hirt-Minkowski et al. investigating the clinical utility of renal allograft monitoring by urine CXCL10 chemokine was published in January 2023, after the Consensus Conference was held [37]. This study did not address the diagnostic performance of urinary CXCL10 to detect allograft rejection but if biopsies triggered by a limited number of urinary CXCL10 quantifications (at week-4, -10, -22) would impact on a composite endpoint at 1 year post-transplant (death-censored graft loss, clinical rejection between month 1 and 1 year, acute rejection in 1 year surveillance biopsy, chronic active T-cell–mediated rejection in 1 year surveillance biopsy, development of de novo donor-specific HLA antibodies, or eGFR <25 mL/min). In this landmark study, the primary composite endpoint was not met, underlining the need for further refinement in the methods and timing of posttransplant monitoring. However, the diagnostic performance of urinary CXCL10 to detect allograft rejection defined by the Banff 2019 classification was studied in an ancillary study and confirmed the diagnostic value of uCXCL10 (ROCAUC 0.73, p = 0.002). We believe that this study should provide a positive signal in the field, confirming the feasibility of implementing noninvasive biomarkers and prompting new interventional studies.

Summary and Next Steps

The development and evolution of non-invasive molecular biomarkers of rejection in kidney transplant patients has started and will continue to revolutionize the care and management of patients. Here we provide a thorough review of the literature supporting these different molecular tests through mid-2022. Despite the number of published studies describing the diagnostic utility of these tests, the field still lacks from adequate perspective, interventional clinical trials demonstrating the value of using these biomarkers in prospective patient management.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript and the ESOT Consensus Working Group is a collaborative work product of ESOT and its Sections and Committees. We would like to thank Devi Mey, Justyna Klimek, Irene Garcia, Giovanna Rossi, Daniele Roppolo and the entire ESOT staff for their tireless efforts to support this endeavor. We would also like to thank Liset Pengel, the CET and the YPTs for coordinating and performing the systematic literature searches which were additionally instrumental in this endeavor.

Funding Statement

All costs related to taskforce and workgroup meetings were covered by ESOT, without external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Involved in the conception or design of the work: SP, JS, CT, DA, OB, and JF. Literature screen and review: SP, JS, CT, DA, OB, and JF. Drafted the article: SP, JS, CT, DA, OB, and JF. Critically revised the article: SP, JS, CT, DA, OB, and JF. Finally approved the version to be published: SP, JS, CT, DA, OB, and JF.

Conflict of Interest

JF receives consulting fees from Eurofins - Transplant Genomics and grant support from Eurofins - Viracor. SP receives grant support from Eurofins - Viracor.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ti.2023.12115/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Friedewald JJ, Kurian SM, Heilman RL, Whisenant TC, Poggio ED, Marsh C, et al. Development and Clinical Validity of a Novel Blood-Based Molecular Biomarker for Subclinical Acute Rejection Following Kidney Transplant. Am J Transpl (2019) 19:98–109. 10.1111/ajt.15011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sigdel TK, Archila FA, Constantin T, Prins SA, Liberto J, Damm I, et al. Optimizing Detection of Kidney Transplant Injury by Assessment of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA via Massively Multiplex PCR. J Clin Med (2018) 8:19. 10.3390/jcm8010019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bu L, Gupta G, Pai A, Anand S, Stites E, Moinuddin I, et al. Clinical Outcomes From the Assessing Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Monitoring Insights of Kidney Allografts With Longitudinal Surveillance (ADMIRAL) Study. Kidney Int (2022) 101:793–803. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang W, Yi Z, Keung KL, Shang H, Wei C, Cravedi P, et al. A Peripheral Blood Gene Expression Signature to Diagnose Subclinical Acute Rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol (2019) 30:1481–94. 10.1681/ASN.2018111098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bouamar R, Shuker N, Hesselink DA, Weimar W, Ekberg H, Kaplan B, et al. Tacrolimus Predose Concentrations Do Not Predict the Risk of Acute Rejection After Renal Transplantation: A Pooled Analysis From Three Randomized-Controlled Clinical Trials(†). Am J Transpl (2013) 13:1253–61. 10.1111/ajt.12191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cillo U, Weissenbacher A, Pengel L, Jochmans I, Roppolo D, Amarelli C, et al. ESOT Consensus Platform for Organ Transplantation: Setting the Stage for a Rigorous, Regularly Updated Development Process. Transpl Int (2022) 35:10915. 10.3389/ti.2022.10915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park S, Guo K, Heilman RL, Poggio ED, Taber DJ, Marsh CL, et al. Combining Blood Gene Expression and Cellfree DNA to Diagnose Subclinical Rejection in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (2021) 16:1539–51. 10.2215/CJN.05530421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chang JH, Alvarado Verduzco H, Toma K, Sritharan S, Mohan S, Husain SA. Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA and Renal Allograft Rejection in Surveillance Biopsies and Indication Biopsies. Clin Transpl (2022) 36:e14561. 10.1111/ctr.14561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bloom RD, Bromberg JS, Poggio ED, Bunnapradist S, Langone AJ, Sood P, et al. Cell-Free DNA and Active Rejection in Kidney Allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol (2017) 28:2221–32. 10.1681/ASN.2016091034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jordan SC, Bunnapradist S, Bromberg JS, Langone AJ, Hiller D, Yee JP, et al. Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Identifies Antibody-Mediated Rejection in Donor Specific Antibody Positive Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transpl Direct (2018) 4:e379. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang E, Sethi S, Peng A, Najjar R, Mirocha J, Haas M, et al. Early Clinical Experience Using Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA to Detect Rejection in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am J Transpl (2019) 19:1663–70. 10.1111/ajt.15289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oellerich M, Shipkova M, Asendorf T, Walson PD, Schauerte V, Mettenmeyer N, et al. Absolute Quantification of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA as a Marker of Rejection and Graft Injury in Kidney Transplantation: Results From a Prospective Observational Study. Am J Transpl (2019) 19:3087–99. 10.1111/ajt.15416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Whitlam JB, Ling L, Skene A, Kanellis J, Ierino FL, Slater HR, et al. Diagnostic Application of Kidney Allograft-Derived Absolute Cell-Free DNA Levels During Transplant Dysfunction. Am J Transpl (2019) 19:1037–49. 10.1111/ajt.15142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stites E, Kumar D, Olaitan O, John Swanson S, Leca N, Weir M, et al. High Levels of Dd-cfDNA Identify Patients With TCMR 1A and Borderline Allograft Rejection at Elevated Risk of Graft Injury. Am J Transpl (2020) 20:2491–8. 10.1111/ajt.15822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mayer KA, Doberer K, Tillgren A, Viard T, Haindl S, Krivanec S, et al. Diagnostic Value of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA to Predict Antibody-Mediated Rejection in Donor-Specific Antibody-Positive Renal Allograft Recipients. Transpl Int (2021) 34:1689–702. 10.1111/tri.13970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gupta G, Moinuddin I, Kamal L, King AL, Winstead R, Demehin M, et al. Correlation of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA With Histology and Molecular Diagnoses of Kidney Transplant Biopsies. Transplantation (2022) 106:1061–70. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Halloran PF, Reeve J, Madill-Thomsen KS, Demko Z, Prewett A, Billings P, et al. The Trifecta Study: Comparing Plasma Levels of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA With the Molecular Phenotype of Kidney Transplant Biopsies. J Am Soc Nephrol (2022) 33:387–400. 10.1681/ASN.2021091191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Halloran PF, Reeve J, Madill-Thomsen KS, Kaur N, Ahmed E, Cantos C, et al. Combining Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Fraction and Quantity to Detect Kidney Transplant Rejection Using Molecular Diagnoses and Histology as Confirmation. Transplantation (2022) 106:2435–42. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang W, Yi Z, Wei C, Keung KL, Sun Z, Xi C, et al. Pretransplant Transcriptomic Signature in Peripheral Blood Predicts Early Acute Rejection. JCI Insight (2019) 4:e127543. 10.1172/jci.insight.127543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roedder S, Sigdel T, Salomonis N, Hsieh S, Dai H, Bestard O, et al. The kSORT Assay to Detect Renal Transplant Patients at High Risk for Acute Rejection: Results of the Multicenter AART Study. PLoS Med (2014) 11:e1001759. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Loon E, Giral M, Anglicheau D, Lerut E, Dubois V, Rabeyrin M, et al. Diagnostic Performance of kSORT, a Blood-Based mRNA Assay for Noninvasive Detection of Rejection after Kidney Transplantation: A Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Am J Transpl (2020) 21:740–50. 10.1111/ajt.16179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Akalin E, Weir MR, Bunnapradist S, Brennan DC, Delos Santos R, Langone A, et al. Clinical Validation of an Immune Quiescence Gene Expression Signature in Kidney Transplantation. Kidney 360. (2021) 2:1998–2009. 10.34067/KID.0005062021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheung R, Xu H, Jin X, Tian W, Pinney K, Bu L, et al. Validation of a Gene Expression Signature to Measure Immune Quiescence in Kidney Transplant Recipients in the CLIA Setting. Biomark Med (2022) 16:647–61. 10.2217/bmm-2022-0113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Loon E, Gazut S, Yazdani S, Lerut E, de Loor H, Coemans M, et al. Development and Validation of a Peripheral Blood mRNA Assay for the Assessment of Antibody-Mediated Kidney Allograft Rejection: A Multicentre, Prospective Study. EBioMedicine (2019) 46:463–72. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.07.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ho J, Rush DN, Karpinski M, Storsley L, Gibson IW, Bestland J, et al. Validation of Urinary CXCL10 as a Marker of Borderline, Subclinical, and Clinical Tubulitis. Transplantation (2011) 92:878–82. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31822d4de1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hirt-Minkowski P, Amico P, Ho J, Gao A, Bestland J, Hopfer H, et al. Detection of Clinical and Subclinical Tubulo-Interstitial Inflammation by the Urinary CXCL10 Chemokine in a Real-Life Setting. Am J Transpl (2012) 12:1811–23. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.03999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rabant M, Amrouche L, Morin L, Bonifay R, Lebreton X, Aouni L, et al. Early Low Urinary CXCL9 and CXCL10 Might Predict Immunological Quiescence in Clinically and Histologically Stable Kidney Recipients. Am J Transplant (2016) 16:1868–81. 10.1111/ajt.13677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tinel C, Devresse A, Vermorel A, Sauvaget V, Marx D, Avettand-Fenoel V, et al. Development and Validation of an Optimized Integrative Model Using Urinary Chemokines for Noninvasive Diagnosis of Acute Allograft Rejection. Am J Transplant (2020) 20:3462–76. 10.1111/ajt.15959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arnau A, Benito-Hernandez A, Ramos-Barron MA, García-Unzueta MT, Gómez-Román JJ, Gómez-Ortega JM, et al. Urinary C-X-C Motif Chemokine 10 Is Related to Acute Graft Lesions Secondary to T Cell- and Antibody-Mediated Damage. Ann Transpl (2021) 26:e929491. 10.12659/AOT.929491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hricik DE, Nickerson P, Formica RN, Poggio ED, Rush D, Newell KA, et al. Multicenter Validation of Urinary CXCL9 as a Risk-Stratifying Biomarker for Kidney Transplant Injury. Am J Transpl (2013) 13:2634–44. 10.1111/ajt.12426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rabant M, Amrouche L, Lebreton X, Aulagnon F, Benon A, Sauvaget V, et al. Urinary C-X-C Motif Chemokine 10 Independently Improves the Noninvasive Diagnosis of Antibody-Mediated Kidney Allograft Rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol (2015) 26:2840–51. 10.1681/ASN.2014080797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Handschin J, Wehmeier C, Amico P, Hopfer H, Dickenmann M, Schaub S, et al. Urinary CXCL10 Measurement in Late Renal Allograft Biopsies Predicts Outcome Even in Histologically Quiescent Patients. Transpl Proc (2021) 53:2168–79. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2021.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: An Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. BMJ (2008) 336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feingold B, Rose-Felker K, West SC, Zinn MD, Berman P, Moninger A, et al. Early Findings After Integration of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Into Clinical Care Following Pediatric Heart Transplantation. Pediatr Transpl (2022) 26:e14124. 10.1111/petr.14124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steggerda JA, Pizzo H, Garrison J, Zhang X, Haas M, Kim IK, et al. Use of a Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Assay to Monitor Treatment Response in Pediatric Renal Transplant Recipients With Allograft Rejection. Pediatr Transpl (2022) 26:e14258. 10.1111/petr.14258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao D, Zhou T, Luo Y, Wu C, Xu D, Zhong C, et al. Preliminary Clinical Experience Applying Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA to Discern Rejection in Pediatric Liver Transplant Recipients. Sci Rep (2021) 11:1138. 10.1038/s41598-020-80845-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hirt-Minkowski P, Handschin J, Stampf S, Hopfer H, Menter T, Senn L, et al. Randomized Trial to Assess the Clinical Utility of Renal Allograft Monitoring by Urine CXCL10 Chemokine. J Am Soc Nephrol (2023) 34:1456–69. 10.1681/ASN.0000000000000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ (2021) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.