SUMMARY

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection, which is almost exclusively sexually transmitted, causes genital herpes. Although this lifelong and incurable infection is extremely widespread, currently there is no readily available diagnostic device that accurately detects HSV-2 antigens to a satisfactory degree. Here, we report an ultrasensitive electrochemical device that detects HSV-2 antigens within 9 min and costs just $1 (USD) to manufacture. The electrochemical biosensor is biofunctionalized with the human cellular receptor nectin-1 and detects the glycoprotein gD2, which is present within the HSV-2 viral envelope. The performance of the device is tested in a guinea pig model that mimics human biofluids, yielding 88.9% sensitivity, 100.0% specificity, and 95.0% accuracy under these conditions, with a limit of detection of 0.019 fg mL−1 for gD2 protein and 0.057 PFU mL−1 for titered viral samples. Importantly, no cross-reactions with other viruses were detected, indicating the adequate robustness and selectivity of the sensor. Our low-cost technology could facilitate more frequent testing for HSV-2.

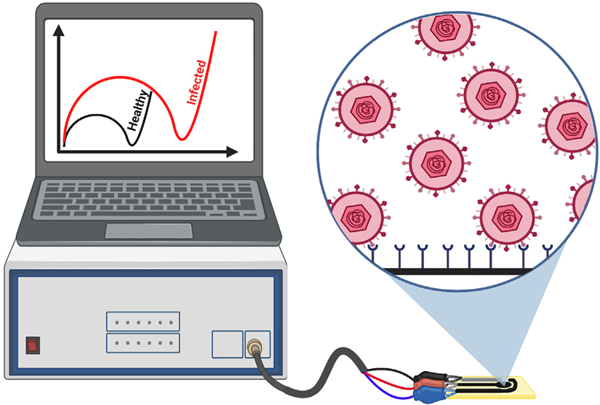

Graphical Abstract

Here, de Lima and Ferreira et al. describe an electrochemical biosensor capable of detecting herpes simplex virus type 2 antigens within 9 min. This low-cost diagnostic test presents excellent analytical performance on animal samples.

INTRODUCTION

Both types of herpes simplex virus (HSV), HSV-1 and HSV-2, are prevalent in humans and cause neonatal infections.1 Furthermore, these viruses can establish lifelong latency in the sensory neuronal ganglia. Subsequent reactivation of latent virus may cause significant health problems and result in viral transmission to healthy individuals. HSV-1, also known as oral herpes, infects the lips, mouth, eyes, and brain; while HSV-2, also known as genital herpes, is associated mainly with genital infections.2

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently estimated the global prevalence of HSV-1 in individuals aged 0–49 years to be 66.6%, or more than 3.7 billion people who have been infected by HSV-1.1 Additionally, the WHO estimates the global prevalence of HSV-2, which is transmitted almost exclusively through sexual contact, to include 13.2% of the world’s population, or 491.6 million people aged 15–49 years. The attachment of the virus to the cell surface initially involves two glycoproteins on the HSV envelope, glycoprotein C (gC), and to a lesser extent, glycoprotein B (gB).3–5 Glycoprotein D (gD), found within the viral envelope, then binds to host cell receptors, initiating a sequence of events that allows HSV to fuse with the host’s cell plasma membrane.6 Studies of the binding of gD to cell surface receptors have led to an understanding of the interaction between human cell receptors and HSV.5,7–9

Despite the prevalence of HSV-2 infections, there are currently no rapid tests available to detect this infectious agent. Historically, viral culturing has been the main test used for HSV detection in the clinic.10 However, recently, molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been widely used in clinical practice due to their increased sensitivity and selectivity compared to viral culture.10,11 Currently, there are very few FDA-cleared molecular tests available for HSV detection. Examples include PCR-based MultiCode-RTx kit, ProbeTec HSV Qx test, and IsoAmp HSV assay with sensitivity and selectivity ranging from 92.4% to 98.4% and 83.7% to 97.0%, respectively. Other commercial serological methods such as immunoblot, ELISA, western blotting, and chemiluminescence immunoassay have also been used to detect HSV.12–14 However, immunoassays rely on the availability of HSV antibodies, and thus, the sensitivity of these tests is influenced by the amount of time since the infection. Indeed, immunoassays display the highest sensitivity when performed at least 21 days after the initial infection and may improve if performed more than 40 days after the primary infection,11 thus clearly hindering early HSV diagnosis. In addition, these diagnostic methods are time-consuming, costly, and laborious, requiring highly trained staff and sophisticated laboratory infrastructure.

Rapid and accessible diagnostic technologies could improve the management of HSV infections, particularly in low-resource settings and in labor and delivery wards.2,15–17 In fact, several portable devices have been reported as alternative methods for the diagnosis of HSV, and electrochemical detection methods are attractive for developing such devices. Electrochemical detection has adequate sensitivity and selectivity and can be associated with accessible and portable instrumentation.18 Generally, these portable diagnostic devices are DNA-based biosensors aiming to detect viral genetic material.18 Detecting viral DNA or RNA present in biofluids can lead to base-pairing mismatches and hybridization problems that compromise the selectivity of the tests. Moreover, these methods commonly require preconcentration or amplification protocols to achieve the desired sensitivity, decreasing the ability to conduct rapid, frequent, and inexpensive tests.18

Rapid and accessible diagnostic technologies constitute promising approaches to help manage HSV-2 infections. Here, we describe an impedimetric biosensor for the rapid, ultrasensitive detection of HSV-2 (Figure 1A). Instead of traditional genosensors and serological tests, we report the use of nectin-1 as a cellular receptor19 for the development of an accurate electrochemical diagnostic for HSV-2. Our simple technology uses carbon screen-printed electrodes functionalized with the conductive polymer polyethyleneimine (PEI), the bioreceptor nectin-1, and a chitosan semipermeable membrane (Figure 1B). In order to develop a sensitive and robust rapid test, in our study, we carefully evaluated each functionalization step, investigating the optimal strategy to biofunctionalize the working electrode. Under optimal conditions, our device detected the virus within 9 min (sample incubation + analysis), displayed a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.057 plaque-forming units (PFU) mL−1, and presented 88.9% sensitivity, 100% specificity, and 95% accuracy when tested on 20 pre-clinical samples from the guinea pig vaginal canal (11 negative samples and 9 positive samples).

Figure 1. Detection and functionalization approach of the herpes virus electrochemical biosensor.

(A) Schematic representation of the HSV sensing using the electrochemical biosensor.

(B) Functionalization and optimization steps of the electrochemical biosensor. This figure was created in BioRender.com.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Development and performance of the HSV-2 biosensor

In our study, we used electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) for the transduction of the biosensor response, i.e., the selective binding between the nectin-1 bioreceptor immobilized on the electrode surface and the gD2 glycoproteins from HSV-2. The binding between nectin-1 and gD2 changes the interfacial electron transfer kinetics between ferricyanide/ferrocyanide (i.e., the redox probe used) and the electrode. The altered kinetics, in turn, can be detected by monitoring the increase in resistance to charge transfer (RCT), indicating a positive diagnostic result for HSV-2 infection (Figure 1A), similar to the previous work.20 We carefully studied each functionalization step to generate a reliable, ultrasensitive, and robust biosensor that presents original functional materials for HSV-2 diagnosis (Figure 1B). The RCT values were extracted by application of the Randles equivalent electrical circuit.21

All data from the optimization studies and analytical curves were plotted using the normalized RCT response, as defined by the following equation:

| (Equation 1) |

where Z is the RCT value obtained after incubating the electrode surface with gD2 or HSV-2 samples, and Z0 is the RCT value of the analytical blank solution (i.e., phosphate buffer saline [PBS] or Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium [DMEM] with 5% fetal bovine serum [FBS]). The normalization process of RCT corrects variations in the sensor response, which may be caused by analyst operation and temperature fluctuations when testing. Thus, normalization facilitates the eventual use of the sensor at decentralized testing sites.20

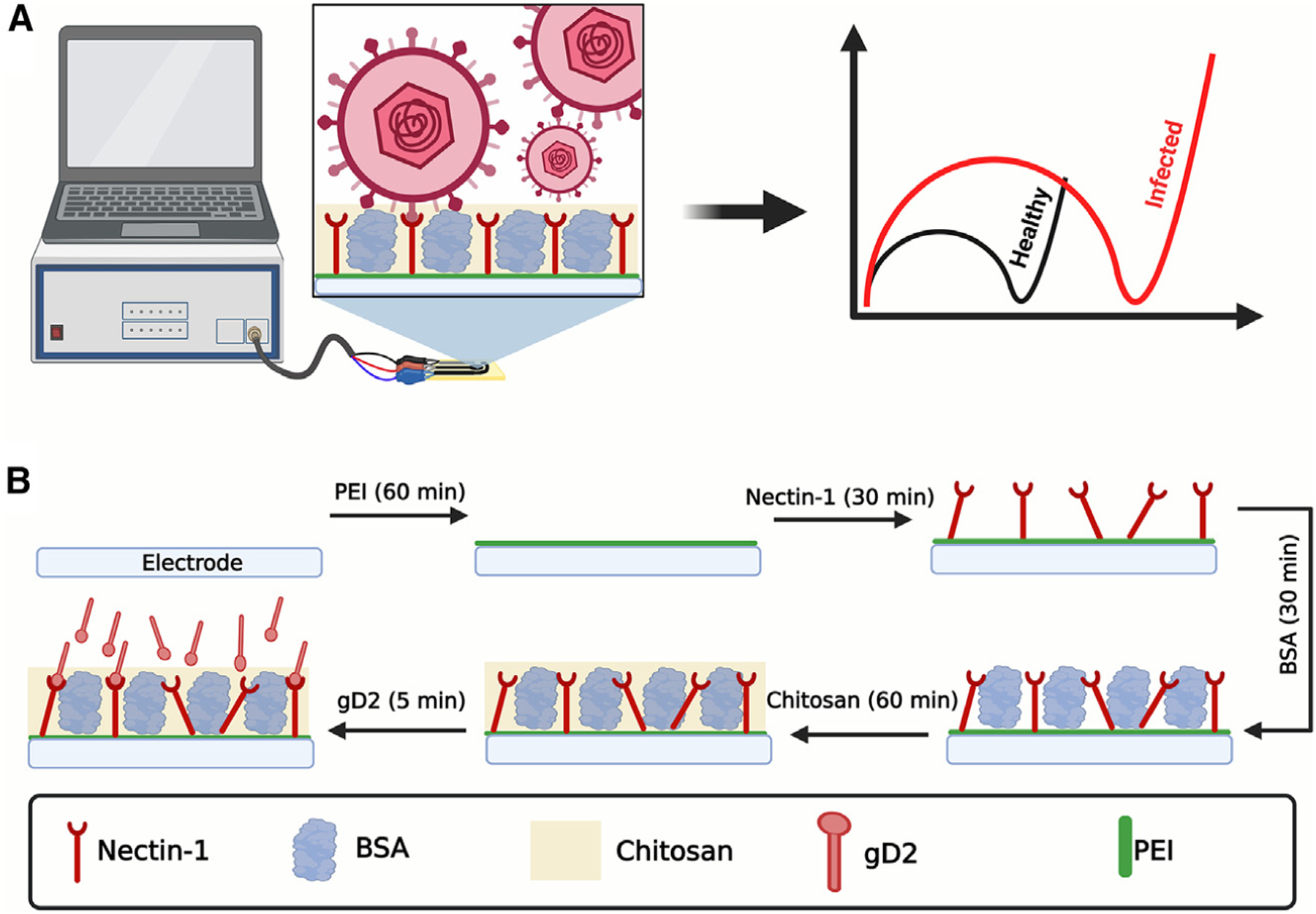

Initially, to generate a robust and sensitive biosensor, two strategies were evaluated to modify the working electrode (WE) and enable the anchoring of the nectin-1 bioreceptor. In the first approach, the WE surface was coated with glutaraldehyde (GA), a dialdehyde widely used to anchor biomolecules through their N-terminal groups22; for the second approach, the WE was modified with PEI, a conductive polymer containing amino functional groups enabling the attachment of biomolecules through their carboxylic acid and ester groups.23,24 Using GA as a modifier did not provide significant discrimination of the analytical signal (RCT) at the concentrations of gD2 tested (10−12–10−9 g mL−1, Figure 2A). This result can be explained by the partial obstruction, or steric effect on the active sites, present in the domain of the receptor when this immobilization strategy was used, which may have hindered the effective interaction with the viral particle. This hypothesis was confirmed by our observation that the PEI modification allowed detection of the binding interactions between nectin-1 and gD2, yielding the high sensitivity seen in the analytical curve (Figure 2A). The binding of the C terminus of nectin-1 to the PEI-modified surface left the –NH groups of the former free for gD2 to interact with.6

Figure 2. Optimization studies of the herpes virus electrochemical biosensor.

(A) Anchoring of nectin-1 using 25% (m/v) GA (black circles) and 1.0 mg mL−1 PEI (red circles). Optimal results were obtained when the substrate was modified with PEI to enable the anchoring of the nectin-1 receptor through the –COOH terminal group.

(B) Analytical response of the biosensor when fabricated without an additional membrane layer (black circles), modified with 0.5% (m/v) chitosan (red circles), and modified with 0.5% (m/v) Nafion (blue circles). The highest sensitivity was obtained when the biosensor was modified with 0.5% (m/v) chitosan.

(C) Effect of chitosan concentration on biosensor sensitivity: 0.0% (black circles), 0.3% (m/v; red circles), 0.5% (m/v; blue circles), 0.7% (m/v; pink circles), and 1.0% (m/v; green circles). Chitosan at 0.5% (m/v) provided the highest detectability maintaining the lowest reagent-to-usage ratio; thus, this condition was selected for subsequent measurements.

(D) Incubation time experiments between gD2 and the modified electrochemical biosensor. Calibration curves were generated using gD2 at concentrations ranging from 1 pg mL−1 to 0.1 ng mL−1 and incubation times ranging from 1 to 7 min. No significantly increased differences in the detectability of gD2 were observed for incubation periods longer than 5 min; thus, this incubation time was selected for subsequent work. All experiments were carried out at room temperature in triplicate (n = 3) and obtained through calibration curves for gD2 at a concentration range between 1.0 pg mL−1 and 0.1 ng mL−1. The error bars correspond to the standard deviation. All EIS measurements were recorded at open circuit potential at the frequency range of 1 3 105 Hz to 0.1 Hz and using an amplitude of 10 mV in the following medium: 5 mmol L−1 [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− in 0.1 mol L−1 KCl solution.

We next optimized the main fabrication, modification, and functionalization steps of the biosensor using PEI. First, the WE was modified with 4.0 µL of 1.0 mg mL−1 PEI solution, by drop-casting, and incubated for 60 min at 37°C. This procedure generates –NH functional groups on the carbon electrode surface.25–27 Then, 4.6 mL of 0.13 mg mL−1 of the nectin-1 receptor, containing a mixture of 25.0 mmol L−1 N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) + 50.0 mmol L−1 N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), was deposited on the surface of the PEI-modified WE, and the biosensor was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The carboxyl groups on nectin-1, when exposed to EDC-NHS, are activated to form a stable ester, which undergoes a nucleophilic addition with the amino groups on the PEI-modified WE, such that a stable amide bond is formed between the PEI-modified carbon electrode and nectin-1.23 Subsequently, the remaining unmodified sites of the electrode surface were blocked with 4.0 µL of a 1.0% (m/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution. In the last step, 4.0 µL of 0.5% (m/v) chitosan was dropped on the surface of the nectin-1-modified WE. Chitosan is a polyelectrolyte semipermeable membrane that presents several advantages as a coating material in the development of biosensors, such as permeability, biocompatibility, hydrophilicity, and the presence of –NH2 and –OH functional groups that enable immobilization of biomolecules through covalent binding or electrostatic interactions. In addition, chitosan forms hydrogel films that provide differential mass transport with preconcentration of some ions and organic molecules, as well as protective features to the transducer/receptor surface, conferring robustness to the biosensors.28–31

After selecting PEI as the optimal immobilization strategy for nectin-1, we evaluated the use of two types of permeable membranes, namely Nafion and chitosan. Analytical curves ranging from 1 × 10−12 to 1 × 10−10 g mL−1 of gD2 in 0.1 mol L−1 of PBS (pH = 7.4) were constructed. Experiments were performed in triplicate to compare three strategies: (1) without a permeable membrane, (2) with 0.5% Nafion, and (3) with 0.5% chitosan (Figure 2B). According to these results, the electrochemical biosensor modified with chitosan 0.5% (m/v) presented a sensitivity of 0.222, which is 1.6-fold higher than the biosensor without any semipermeable membrane (sensitivity of 0.138) and 2.74-fold higher than the biosensor with Nafion (sensitivity of 0.081). The increase in sensitivity is associated with the preconcentration features of the glycoprotein gD2 during the incubation period, which is trapped close to the bioreceptor, enabling a larger number of binding events and enhancing the detectability of our method (Figure 2B). In addition, the positive charges displayed by chitosan in the acidic medium can preconcentrate [Fe(CN)6]3–/4–, i.e., the anionic redox probe, into the polymeric layer, enhancing the electrochemical response.32,33 Given these results, we studied the proportion of chitosan on the modified biosensor since it directly impacts membrane thickness. Our experiments revealed that 0.5% (m/v) of chitosan provided the highest impedimetric responses and analytical sensitivity since higher concentrations provided lower detectability (Figure 2C). Thus, 0.5% (m/v) of chitosan was selected for further studies.

Subsequently, we evaluated the optimal incubation time of either gD2 or viral samples with the surface of the biosensor to obtain the optimal compromise between analytical frequency and sensitivity for HSV-2 detection. The optimization was based on the analytical sensitivity (slope) parameter obtained by analytical curves, determined in triplicate, at concentrations of gD2 ranging from 10−12 to 10−10 g mL−1 (Figure 2D). By balancing detection ability with the sensitivity values of the dose-response curves while maintaining a short testing time, we selected 5 min as the optimal incubation time. These results demonstrate the rapid binding kinetics between gD2 and the immobilized nectin-1 on the electrode surface, underscoring the efficiency of our functionalized biosensor architecture.

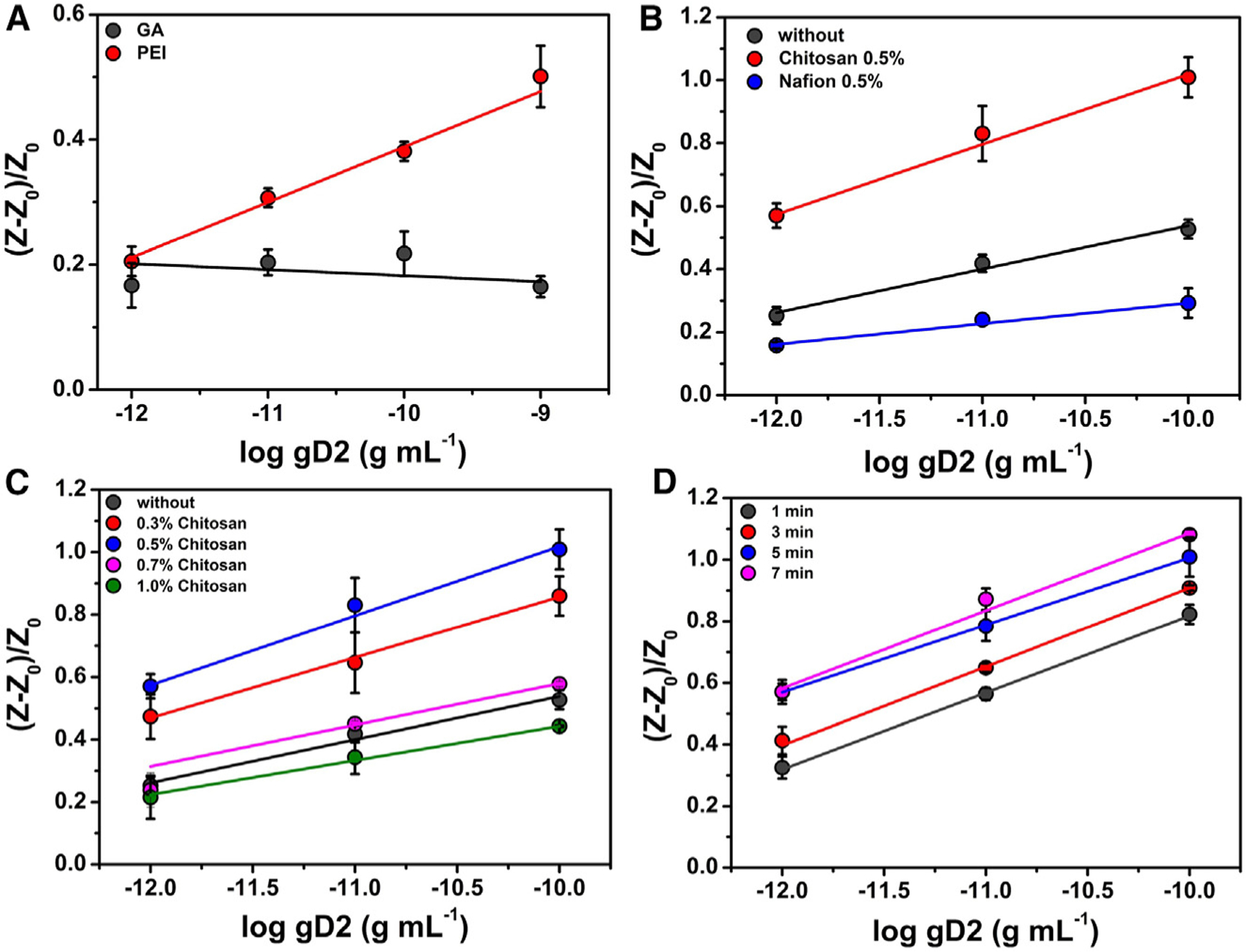

Electrochemical characterization of the biosensor

For each functionalization step (Figure 3A), the electrochemical behavior was characterized by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and EIS (Figures 3B and 3C, respectively). CV (Figure 3B) and Nyquist (Figure 3C) plots show that the bare carbon electrode (black line) presented poorly defined redox processes with peak currents (ip) of 133.1 ± 2.5 μA and RCT of 549.4 ± 24.6 Ω. The electrochemical performance of the sensor was enhanced by modifying the carbon electrode surface with PEI (red line), as well-defined and intense (251.71 ± 3.17 μA) current peaks were observed for the redox probe with an RCT value of 11.1 ± 1.2 Ω. These results were expected, given the high charge transfer generated by the π-electrons of the conductive PEI membrane.34 Next, nectin-1 was anchored to the electrode surface using the EDC-NHS approach (blue line). The receptor was first immobilized through an amide bond between the amine group from the PEI and the carboxyl groups from nectin-1.35 This step led to a small increase in the RCT value, to 17.6 ± 2.1 Ω, and a slight decrease of the ip, to 247.15 ± 2.56 μA (blue line). Any nonspecific sites of the electrode were blocked by using 1.0% (m/v) BSA solution, resulting in an RCT of 26.3 ± 1.2 Ω and ip of 231.2 ± 3.9 μA (magenta line) due to the introduction of a nonconductive layer on the surface of the electrode. Finally, the electrode surface was modified with a 0.5% (m/v) chitosan permeable membrane to enhance the robustness and sensitivity of the biosensor. This step increased the RCT to 47.5 ± 4.0 Ω and decreased the ip to 222.0 ± 3.3 μA (green line).

Figure 3. Functionalization steps and electrochemical characterization of the biosensor.

(A) Schematic representation of the stepwise functionalization of the electrochemical biosensor.

(B) CV experiments were recorded for each modification step made to the biosensor surface in a solution of 5.0 mmol L−1 [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− containing 0.1 mol L−1 KCl as the supporting electrolyte. A potential window from −0.3 V to 0.7 V and a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 were used.

(C) Nyquist plots were obtained using the same conditions as those shown in (A). Inset shows a zoomed-in view of the plots at high-frequency regions. Conditions used were frequency range from 1 × 105 Hz to 0.1 Hz and 10 mV amplitude. Measurements were performed at room temperature. The colors displayed in the CV and Nyquist plots correspond to each modification step outlined in (A). This figure was partially created in BioRender.com.

Analytical performance of the biosensor

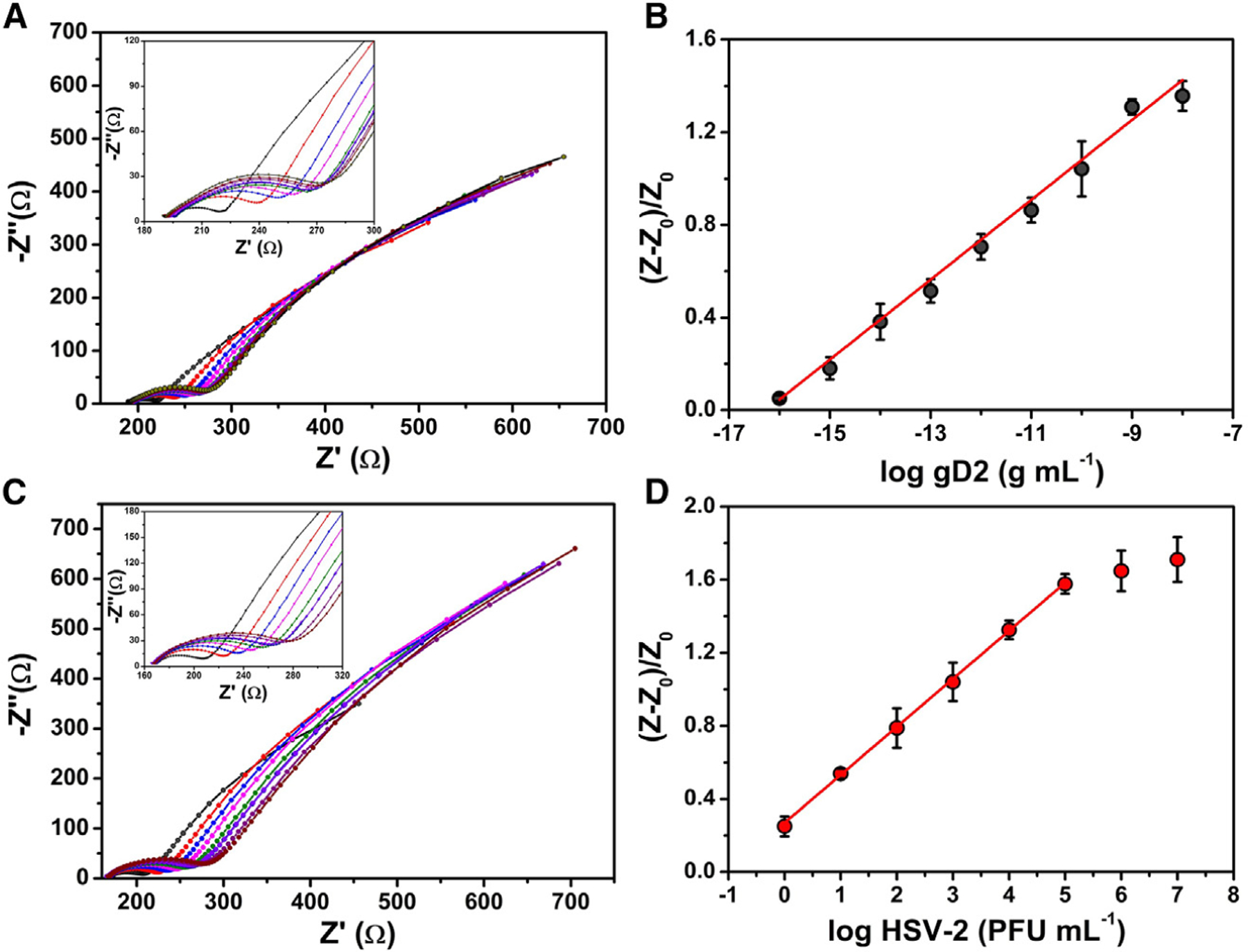

EIS was used to quantify free gD2 and HSV-2 virus in 0.1 mol L−1 PBS (pH = 7.4). Dose-response curves were built with our previously optimized experimental conditions (i.e., 1 mg mL−1 PEI, 0.5% chitosan, and 5 min of incubation time), and the analytical results were normalized according to Equation 1. Figure 4A illustrates Nyquist plots for increased concentrations of gD2 ranging from 0.1 fg mL−1 to 10.0 ng mL−1 in 0.1 mol L−1 PBS (pH = 7.4). A linear correlation was observed over the entire range of concentrations evaluated (0.1 fg mL−1 to 10.0 ng mL−1 gD2), when plotted as a logarithm function (Figure 4B), with a determination coefficient R2 of 0.997. The LOD and limit of quantification (LOQ) were calculated as 0.019 fg mL−1 and 0.089 fg mL−1 gD2, respectively. We also built an analytical curve for a titered HSV-2 sample at concentrations, in a DMEM medium, ranging from 1 × 100 to 1 × 107 PFU mL−1 (Figure 4C). A linear correlation was observed in the concentration range from 1 × 100 PFU mL−1 to 1 × 105 PFU mL−1 with an R2 = 0.999 (Figure 4D). LOD and LOQ were calculated as 0.057 PFU mL−1 and 0.210 PFU mL−1 HSV-2, respectively. Three different biosensors were used per experiment, and concentrations were depicted as the logarithmic function of the dose used for gD2 and HSV-2. The four-parameter logistic curve (Figure S1),36 a method that assesses binding interactions and kinetics,22,37 was used to determine the LOD and LOQ values.

Figure 4. Analytical curves for HSV-2 detection.

(A) Nyquist plots for gD2 at concentrations ranging from 0.1 fg mL−1 to 10.0 ng mL−1 in 0.1 mol L−1 PBS (pH = 7.4).

(B) Dose-response curve obtained from normalized RCT values extracted from Nyquist plots as a function of the logarithm of the gD2 concentration.

(C) Nyquist plots for titered HSV-2 viral solution at levels ranging from 1 × 100 PFU mL−1 to 1 × 107 PFU mL−1.

(D) Dose-response curve obtained from normalized RCT values extracted from Nyquist plots as a function of the logarithm of the HSV-2 viral loads. The EIS measurements were performed in triplicate in 5.0 mmol L−1 [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− and a 0.1 mol L−1 KCl solution applying the open circuit potential at a frequency range of 1 × 105 Hz to 0.1 Hz and using an amplitude of 10 mV. All measurements were recorded in triplicate (n = 3), using 10 μL of gD2 or HSV-2 samples (from 1 × 100 PFU mL−1 to 1 × 107 PFU mL−1), and samples were incubated for 5 min on the biosensor surface. The error bars correspond to the standard deviation.

Collectively, these experiments highlight the excellent sensitivity displayed by our biosensor, which we anticipate can provide an early diagnosis of HSV-2 infection in human clinical samples. Another advantage that our biosensor has for diagnostic purposes is its short testing time, i.e., 9 min, consisting of a 5-min incubation of the sample on the electrode surface and an additional 4 min for the EIS measurements of both the analytical blank and the sample of interest.

In comparison to other methods reported in the literature (Table 1), our method is the first report, to the best of our knowledge, of the use of nectin-1 as a bioreceptor to detect the viral glycoprotein gD2 instead of genosensor technology using genetic material for the recognition of HSV. In addition, our sensor presents the fastest testing time, with a very low LOD and a large interval concentration range to detect HSV-2. Furthermore, our device can be produced inexpensively. Considering the cost of nectin-1 ($800/mg), the final cost to assemble each HSV biosensor was exactly $1.00 (USD): $0.12 for electrode fabrication + $0.40 for all the chemicals used in the functionalization step (PEI + EDC + NHS + BSA + chitosan) + $0.48 for nectin-1. Because our biosensor is low-cost, its production is potentially highly scalable. Potential disadvantages of our method for point-of-care applications are primarily related to the use of a potentiostat that requires some expertise to use, the need for a redox probe solution to obtain the electrochemical response used for diagnostic purposes, and the specific software needed to interpret the results. Altogether, these disadvantages may limit the use of our current setup in testing sites where a trained person ideally would perform the test using multiplexed equipment with implemented routine analysis for frequent testing.

Table 1.

Comparison of the analytical parameters in various methods reported for the detection of herpes viruses

| Method | LOD | Technique | Target | Working concentration range | Time (min) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our method | 0.057 PFU mL−1 | EIS | HSV-2 | 1 × 100 to 1 × 107 PFU mL−1 | 9 | This work |

| 0.019 fg mL−1 | EIS | gD2 | 0.1 fg mL−1 to 10.0 ng mL−1 | |||

| PEGE and MDB/DNA | 14.77 fmol mL−1 | DPV | DNA | 1 to 20 μg mL−1 | 35a | Kara et al.17 |

| Ppy/DNA film | 50.0 fmol mL−1 | Conductivity | DNA | 2.0 to 24.0 pmol mL−1 | – | Tam et al.38 |

| RPA/Au/DNA | 207 copies | Amperometry | DNA | 1 × 101 to 1 × 108 copies | 35 | Toldrà et al.39 |

| Impedimetric immunosensor | 0.66 TCID50 mL−1 | EIS | BHV-1 | 10.0–50.0 TCID50 mL−1 | 10b | Garcia et al.40 |

| Biochip | – | Coulometric | IgG | – | 65 | Loughman et al.41 |

| Smart cup | 100 copies mL−1 | LAMP | DNA | 1 × 100 to 1 × 103 PFU mL−1 | 30 | Nahar et al.42 |

| PP/DNA | 0.61 copies mL−1 | LAMP | DNA | 104 PFU mL−1 to 100 PFU mL−1 | 45 | Narang et al.15 |

| EPAD/Zn-Ag nanoblooms/DNA | 97.0 copies mL−1 | CV | DNA | 113–103 and 3 × 105–1×106 copies mL−1 | 120c | Kessler et al.43 |

| LC/DNA | 1 × 104 copies mL−1 | PCR | DNA | 2 × 103 to 5 × 103 copies mL−1 | 30 | Weidmann et al.2 |

| LC/DNA | 10.0 copies mL−1 | PCR | DNA | – | 150 | Perkins et al.44 |

| LC/DNA | between 1 and 5 copies/reaction | PCR | DNA | 3.5 to 36 × 108 copies mL−1 | – | Burrows et al.45 |

| LC/DNA | 4 copies μL−1 | PCR | DNA | – | <60 | Dominguez et al.46 |

| LC/DNA | 1 copy mL−1 | PCR | DNA | 18.0 to 35.9 Ct | – | Tam et al.38 |

| LC/DNA | 1.2 to 5.8 copies/test | RT-PCR | DNA | – | 90 | Krumbholz et al.47 |

| MultiCode | – | RT-PCR | DNA | – | 240 | MultiCode-RTx Herpes |

| -RTx HSV 1&2 Kit | Simplex Virus 1 & 2 Kit, Real-Time PCR Qualitative Detection and Typing of HSV-1 or HSV-248 | |||||

| BD ProbeTec HSV Qx test | – | RT-PCR | DNA | – | 160 | BD ProbeTec Herpes Simplex Viruses (HSV 1 & 2) Qx Amplified DNA Assays49 |

| IsoAmp HSV assay | 34.1 copies/test | HDA-LFA | DNA | – | 90 | Kim et al.50 |

PEGE, pencil graphite electrodes; MDB, Meldola blue; DPV, differential pulse voltammetry; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; PP, polypropylene; EPAD, electrochemical paper-based analytical device; CV, cyclic voltammetry; LC, LightCycler; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; GE, genome equivalents; OsHV-1, ostreid herpesvirus 1; RPA, isothermal recombinase polymerase amplification; Au, gold electrode; BHV-1, bovine herpesvirus type 1; HDA-LFA, helicase-dependent amplification and lateral-flow analysis.

Testing time considering only hybridization and accumulation processes.

Considering only the sample incubation.

Considering only the hybridization step.

We also studied the effect on the biosensor’s electrochemical response of adjusting the pH of the medium to a pH that is close to physiological conditions (Figure S2). DMEM medium was used to dilute the titered virus samples, and each pH value was adjusted to the range of 7.1–7.7 and tested using the optimized protocol previously described. When the pH of DMEM was 7.1, the biosensor exhibited a high detectability and a sensitivity of 0.212 ± 0.008. At pH 7.4, sensitivity increased to 0.263 ± 0.003. Finally, when the pH of DMEM was 7.7, the analytical sensitivity of the biosensor decreased (0.207 ± 0.008). These data can be explained by conformational changes of the biomolecules induced by differences in pH that, in turn, affect the binding of gD2 to the nectin-1 receptor. These results indicate the importance of adjusting the pH of biofluids for diagnostic purposes, for example, by using a buffered medium, since genital samples are usually acidic.6,51 Our results are consistent with previous studies evaluating the effect of pH changes on the interaction between gD2 and the nectin-1 receptor, which found that the alkalinity of the medium changed the proximity between the viral bilayer and the host cell membrane, likely affecting the interaction between nectin-1 and gD2. These changes influence the ability of the virus to fuse with and infect the cells.6,51

Reproducibility and stability assays

To verify the reproducibility of the proposed method, i.e., to assess whether different batches of biosensors performed similarly, we evaluated six biosensors from different fabrication rounds using the same optimized protocol. Briefly, the RCT measures were recorded by EIS using 5 mmol L−1 [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− after incubating the biosensor with 1 × 10−9 g mL−1 of gD2 prepared in 0.1 mol L−1 of PBS (pH = 7.4) (Figure S3). A relative standard deviation (RSD) of 5.12% was obtained, indicating excellent reproducibility of our manufacturing and biofunctionalization protocol. The experiments were carried out by incubating 10 μL of sample diluted in 0.1 mol L−1 PBS (pH = 7.4) for 5 min before recording each measurement.

The stability of the electrochemical biosensor, stored in sealed Petri plates at various temperatures (−20°C, 4°C, and 25°C), was evaluated over 7 days. Analytical curves were built at concentrations ranging from 1 × 10−12 g mL−1 to 1 × 10−9 g mL−1 gD2 in 0.1 mol L−1 PBS, pH 7.4 (Figure S4). The biosensors did not exhibit stability when stored at room temperature overnight. When stored at −20°C, on the other hand, the biosensors were stable for up to 72 h, but after 120 h, the sensitivity decreased to 48% of the initial value. The freezing of the biosensor for prolonged periods may modify the structuring of the functionalized surface, changing its ability to recognize the virus, i.e., the sensitivity. In this regard, electrodes stored at 4°C, the intermediary condition tested, were stable for 120h (5 days). The mean sensitivity of the device decreased after 7 days, displaying only 40% of the initial performance of the device. These results demonstrate that our biosensor has better stability if it is refrigerated at 4°C; thus, refrigeration would be a convenient way to store our devices for decentralized applications.

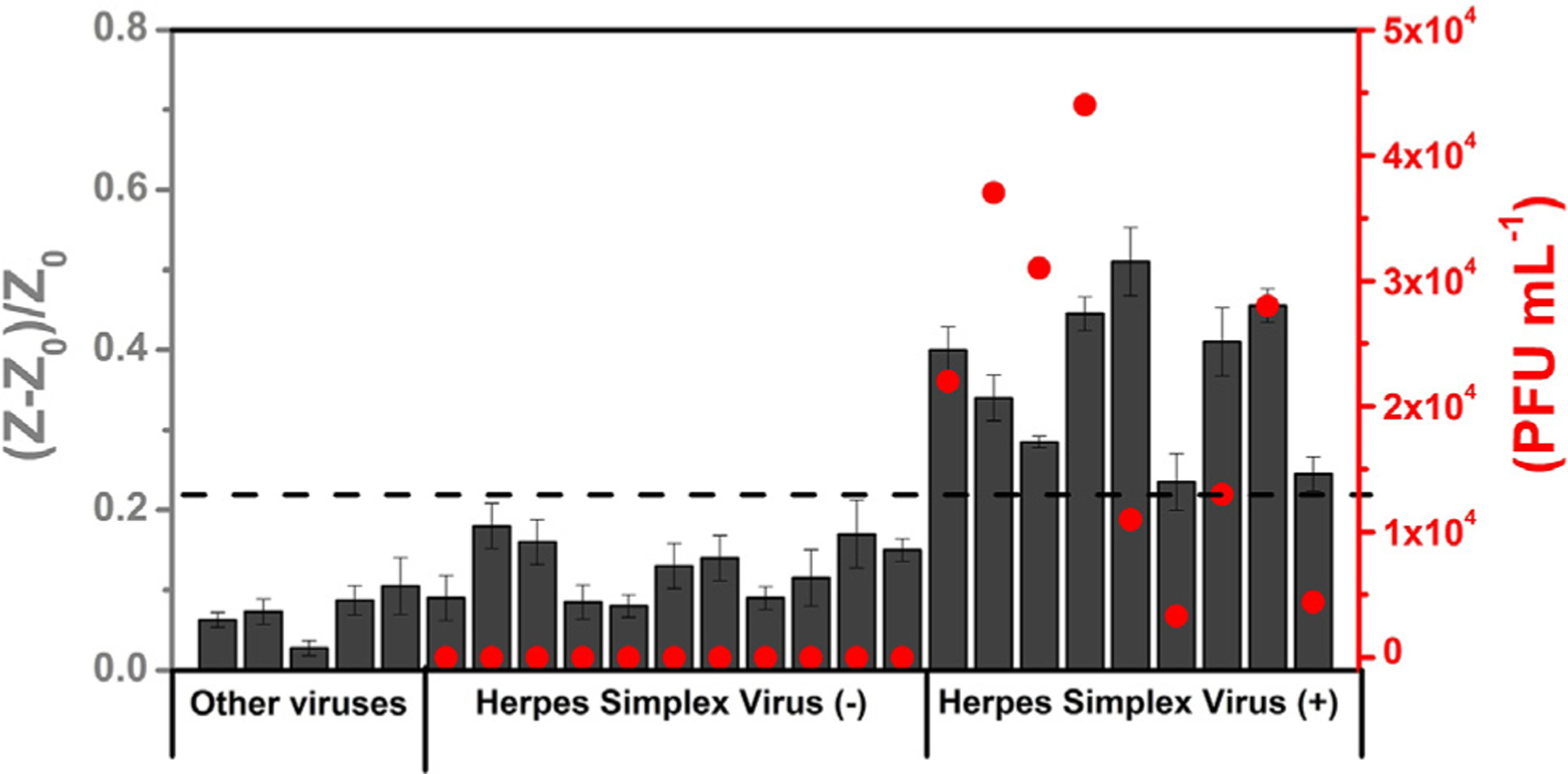

Detection of HSV-2 in a pre-clinical animal model

Next, we assessed the ability of our biosensor to detect HSV-2 in 20 pre-clinical samples. We tested blindly, in triplicate (n = 3), 9 HSV-2-positive and 11 HSV-2-negative biofluid samples collected from the vagina of guinea pigs at the University of Pennsylvania (Figure 5). All samples were heat-inactivated (56°C for 1 h) prior to the electrochemical analysis. All samples were obtained from guinea pigs that had been infected 2 days earlier with HSV-2 or that were uninfected. The biosensor performance is dependent on the cutoff used to discriminate positive and negative samples. A low cutoff can enable the detection of low viral loads but may lead to false positive results. On the other hand, high cutoff values avoid false positive results but limit the detectability of the method, i.e., lead to false negative results.52 For diagnostic purposes, we set the cutoff value of our biosensor as [(Z − Z0)/Z0] > 0.22 to identify a positive HSV-2 result and [(Z − Z0)/Z0] < 0.22 for negative samples. The cutoff value was based on the analytical signal obtained for the lowest quantity of titered virus analyzed (Figure 4D). Our biosensor achieved 88.9% sensitivity, 100% specificity, and 95% accuracy for the set of 20 samples evaluated, i.e., our biosensor correctly diagnosed 19/20 samples tested. However, increasing the number of clinical samples could impact the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the proposed method. We note a response variation between the proposed method and the titrated method for sample analyses (Figure 5). This is likely due to the heat inactivation process prior to performing the electrochemical measurements, since heat inactivation induces viral lysis, generating different amounts of free gD2 or cell fragments containing gD2 that can interact with the nectin-1 present on the surface of the WE. In addition, the heating step needs to be carefully performed to avoid denaturation of the glycoproteins, i.e., structural alterations on viral proteins (gD2).53 Thus, these points prevent an exact correlation between the titrated method and our approach. However, based on the data obtained, we consider that the high diagnostic accuracy (95%) observed for the 20 samples tested suggests that our selective biosensor approach is excellent at detecting HSV-2 viral particles in complex samples and thus constitutes a promising alternative to standard methods.

Figure 5. Detection of HSV-2 in biofluid samples from guinea pigs.

Comparison of the electrochemical biosensor response (normalized RCT values) obtained for the cross-reactivity studies (other viruses) in VTM and the analyses of 20 guinea pig vagina samples in DMEM (11 HSV-2 negative and 9 HSV-2 positive) (dark gray bars) and quantification of the HSV-2-positive samples obtained using the conventional titrated method (red circles) and shown as PFU mL−1. The dotted line indicates the cutoff value of the normalized RCT response established to indicate whether the sample was identified as positive for HSV-2 by our biosensor. All electrochemical measurements were recorded in triplicate (n = 3), and the error bars correspond to the standard deviation.

Cross-reactivity experiments

We performed cross-reactivity experiments to rule out any potential off-target effects of our nectin-1-modified electrode with viruses other than HSV. Selectivity was studied for five viruses: H1N1 (A/California/2009), influenza B (B/Colorado), influenza A H3N2, MHV-mouse hepatitis virus, and SARS-CoV-2. All experiments were performed using the same optimized conditions as those used for HSV-2 detection. No significant cross-reactivity was detected with any of the viruses tested, as revealed by a relative RCT percentage of up to 12%, which is lower than the cutoff value of 22% established for a positive diagnosis of HSV-2 infection in biofluid samples (Figure S5). These results, associated with the selectivity observed in the analysis of pre-clinical samples (guinea pig vaginal biofluids) in which no false positives were detected, highlight the robustness and selectivity of our biosensor. However, the glycoprotein D proteins from HSV-1 and HSV-2 have a high degree of identity, and both viruses can enter the cell through gD binding to the nectin-1 receptor, which could result in the detection of HSV-1 if that virus were present in genital biofluid or the clinical sample tested. Our device can be advantageous to diagnose both HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections. A relevant scenario for the use of such a testing device could be in pregnant women in labor before childbirth if the presence of either HSV-1 or HSV-2 is suspected. Such a diagnosis can help prevent the newborn from acquiring neonatal herpes from an infected mother.

In summary, we have developed an electrochemical biosensor for the ultrasensitive detection of HSV-2 antigen, using nectin-1 as the receptor. In fact, this is the first electrochemical approach that uses nectin-1 as a recognition element instead of the well-established DNA-based strategy. Our approach is substantially less complex than DNA-based methods as the analytical steps do not require amplification or hybridization. With this device, the detection of viral antigen requires only minimal amounts of sample (10 μL). The biosensor can be prepared in less than 3 h, and when stored at 4°C, it remains stable for at least 5 days. Furthermore, the process of detection takes only 9 min. The sample is incubated on the electrode surface for the first 5 min, and the analytical blank and the sample are measured by EIS within 4 min. Our simple manufacturing and biofunctionalization method provides a biosensor with reproducible (RSD = 5.12%) and excellent analytical features for detecting HSV-2 (LODs of 0.019 fg mL−1 for free gD2 in PBS medium and 0.057 PFU mL−1 for titered virus in DMEM). Collectively, our method provides an excellent alternative for HSV diagnosis since it does not require the amplification and hybridization steps that are commonly used in DNA-based methods. Its low cost ($1.00 USD test) and speed of detection can allow frequent tests for screening of the population, mainly in resource-limited settings and labor and delivery wards. In our analysis of 20 guinea pig vaginal biofluid samples, the biosensor accurately detected 8/9 HSV-2 positive samples and 11/11 negative samples, achieving 88.9% sensitivity, 100% specificity, and 95% accuracy. In conclusion, we present an inexpensive, rapid, and accurate technology for diagnosing HSV-2 antigen in relevant biological samples.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Resource availability

Lead contact

C.F.N. is the lead contact; e-mail address: cfuente@upenn.edu.

Materials availability

Sensors generated in this study will be made available upon reasonable request.

Data and code availability

All the data generated in this study will be made available upon reasonable request.

Chemicals and apparatus

Analytical-grade reagents were used for the experiments. Deionized water (resistivity ≥18 MΩ cm at 25°C) was obtained from a Milli-Q Advantage-0.10 purification system (Millipore). Human herpes virus entry mediator (HveC), also called human nectin-1 (residues 31–346), and gD2 strain 333 (residues 1 to 285, gD(285t)) proteins were recombinantly produced by baculoviruses. Their purification from infected insect cells was described previously.54,55 EDC, NHS with a degree of purity ≥98%, BSA, chitosan (molecular weight = ~50,000 Da), PBS solution, pH = 7.4, and glutaraldehyde (25%, v/v) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. PEI was obtained from Polysciences. Carbon and Ag/AgCl conductive inks were obtained from Creative Materials. A six-channel MULTI AUTOLAB M101 potentiostat operated by the NOVA 2.1 software was used for the electrochemical measurements.

Electrochemical measurements

All electrochemical measurements were carried out using a mixture of 5.0 mmol L−1 [Fe(CN)6]3− and [Fe(CN)6]4–, as a redox probe, in 0.1 mol L−1 KCl solution. All functionalization steps of the biosensor were characterized by EIS, which was also used to quantify the HSV-2 and gD2 concentrations. The frequencies used ranged from 1 × 105 Hz to 0.1 Hz, and the open circuit potential was applied with an amplitude of 10 mV (vs. Ag/AgCl). For CV experiments, the potential ranged from −0.3 to 0.7 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) using a scan rate of 50 mV s−1.

Fabrication of electrochemical devices

The electrochemical sensors (three-electrode configuration) were manufactured by a screen-printing technique on phenolic paper circuit board material, as a low-cost and convenient platform.20 Electrically conductive carbon and Ag/AgCl inks (Creative Materials, USA) were employed to construct the working (WE)/auxiliary (AE) and reference (RE) electrodes, respectively. After a curing step of 30 min at 100°C, the material was cut into 2.5 × 2.0 cm pieces, and their geometrical area was delimited using dielectric tape.

Biosensor functionalization assays

To prepare the electrochemical biosensor, the nectin-1 receptor was first immobilized onto the WE through the drop-casting method. Briefly, 4.0 μL of 1.0 mg mL−1 PEI solution prepared in deionized water was gently deposited on the WE and dried for 60 min at 37°C. Next, 4.6 μL of 0.13 mg mL−1 nectin-1 receptor containing 25.0 mmol L−1 EDC and 50.0 mmol L−1 of NHS solution prepared in 0.1 mol L−1 PBS (pH = 7.4) was deposited on the surface of the PEI-modified WE and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Subsequently, the remaining unmodified zones of the WE were blocked with 4.0 μL of 1.0% (m/v) BSA solution prepared in deionized water, and the devices were stored for 30 min at 37°C to dry. This step aims to prevent nonspecific interactions of the sample with the biosensor’s surface. Finally, 4.0 μL of chitosan 0.5% (m/v), prepared in 2% (v/v) acetic acid, was deposited onto the WE. The biosensor was incubated at 37°C for 60 min and then washed with 0.1 mol L−1 PBS (pH = 7.4) before use.

Collection of vaginal swab samples from HSV-2-infected guinea pigs

In guinea pigs, vaginal infection with HSV-2 causes a clinical disease similar to that in humans; this model is described in detail elsewhere.56 Briefly, female guinea pigs were infected intravaginally with HSV-2 MS strain (5 × 105 PFU) in a 50 μL inoculum volume. Mock infections were used as controls. Vaginal swabs, collected on day 2, were stored at −80°C in 1 mL DMEM containing heat-inactivated 5% FBS and an antibiotics/antimycotics cocktail.56 The samples were quantified for the replicating virus by incubating serial 10-fold dilutions of each of the swab samples onto Vero cells for 1 h in an incubator under 5% CO2 at 37°C. Dilutions of the samples were removed after 1 h and overlaid with 1.5% methylcellulose in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and incubated for 72 h in the same incubator. The overlay was removed, and 0.1% crystal violet in 25% methanol was added to the cells. Plaques were counted under the microscope and calculated as PFU mL-1.57

HSV-2 biosensing

For the HSV-2 biosensing, 10.0 μL of 0.1 mol L−1 PBS (pH = 7.4) or DMEM containing either gD2 or HSV-2 samples was applied to the electrochemical cell to cover the surface of the WE. The electrochemical cells were incubated at room temperature for 5 min, and then the electrochemical cell was washed with PBS (0.1 mol L−1; pH = 7.4) to remove unbound components. Then, the redox probe (200 μL of a 5.0 mmol L−1 [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− in 0.1 mol L−1 KCl solution) was used for the EIS measurements. The RCT values were calculated with the use of the Randles equivalent electrical circuit on the Nyquist plots. The HSV-2 samples were heat-inactivated (56°C for 1 h) prior to the analysis.

Reproducibility, stability, and cross-reactivity studies

Reproducibility was studied with six biosensors, each having electrodes manufactured from different batches. Biosensors were exposed to 1.0 ng mL−1 of gD2 and incubated for 5 min. The analytical signals (RCT values) obtained for these six devices were used to calculate the RSD. The stability of the biosensors stored at 25°C, −20°C, or 4°C was evaluated over 7 days by extracting the analytical sensitivity parameter from analytical curves at concentrations of gD2 ranging from 1 × 10−12 to 1 × 10−10 g mL−1. The cross-reactivity studies used the same optimized condition as used for HSV-2 detection, with five viruses, all at 105 PFU mL−1 except for MHV, which was at 108 PFU mL−1: H1N1 (A/California/2009), influenza B (B/Colorado), H3N2, MHV-mouse hepatitis virus, and SARS-CoV-2 prepared in viral transport medium (VTM).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Ultrasensitive electrochemical biosensor for herpes simplex virus (HSV) detection

The biosensor enables rapid and accurate detection of HSV within minutes

The biosensor is inexpensive ($1 USD per test) compared to existing HSV detection methods

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C.F.N. holds a Presidential Professorship at the University of Pennsylvania, is a recipient of the Langer Prize by the AIChE Foundation, and acknowledges funding from the Procter & Gamble Company, United Therapeutics, a BBRF Young Investigator Grant, and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA; HDTRA11810041 and HDTRA1-21-1-0014). Research reported in this publication was supported by the Nemirovsky Prize, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R35GM138201, Penn Health-Tech Accelerator Award, the IADR Innovation in Oral Care Award, and by funds provided by the Dean’s Innovation Fund from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (all to C.F.N.). H.M.F. acknowledges the NIAID RO1 grant 139618. W.R.d.A. acknowledges funding from Brazilian funding agencies CAPES (88887.479793/2020-00), FAPESP (2022/03250-7, and 2018/08782-1), FAEPEX/PRP/UNICAMP (3374/19), and CNPq (438828/2018-6) for supporting the research. Figures 1 and 3 and graphical abstract were prepared in BioRender.com. We thank Dr. Susan Weiss’ Lab for kindly donating the following strains: H1N1 (A/California/2009), influenza B (B/Colorado), H3N2, and MHV-muouse hepatitis virus. We also thank Dr. Ronald Collman for kindly donating SARS-CoV-2 samples. We thank the de la Fuente Lab for insightful discussions, Dr. Karen Pepper for editing the manuscript, and Dr. Jon Epstein for his support.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101513.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

A non-provisional patent application has been filed on the de la Fuente Lab’s related work (ID number 23–10377). C.F.N. provides consulting services to Invaio Sciences and is a member of the Scientific Advisory Boards of Nowture S.L. and Phare Bio. The de la Fuente Lab has received research funding or in-kind donations from United Therapeutics, Strata Manufacturing PJSC, and Procter & Gamble, none of which were used in support of this work. C.F.N. is on the Advisory Board of Cell Reports Physical Science.

INCLUSION AND DIVERSITY

One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as an underrepresented ethnic minority in their field of research or within their geographical location. One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as a gender minority in their field of research. One or more of the authors of this paper received support from a program designed to increase minority representation in their field of research. We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

REFERENCES

- 1.James C, Harfouche M, Welton NJ, Turner KM, Abu-raddad LJ, Gottlieb SL, and Looker KJ (2020). Herpes simplex virus: global infection prevalence and incidence estimates. Bull. World Health Organ 98, 315–329. 10.1086/342104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weidmann M, Meyer-König U, and Hufert FT (2003). Rapid detection of herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus infections by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol 41, 1565–1568. 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1565-1568.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herold BC, Visalli RJ, Susmarski N, Brandt CR, and Spear PG (1994). Glycoprotein C-independent binding of herpes simplex virus to cells requires cell surface heparan sulphate and glycoprotein B. J. Gen. Virol 75, 1211–1222. 10.1099/0022-1317-75-6-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WuDunn D, and Spear PG (1989). Initial interaction of herpes simplex virus with cells is binding to heparan sulfate. J. Virol 63, 52–58. 10.1128/jvi.63.1.52-58.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicola AV, Peng C, Lou H, Cohen GH, and Eisenberg RJ (1997). Antigenic structure of soluble herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D correlates with inhibition of HSV infection. J. Virol 71, 2940–2946. 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2940-2946.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberg RJ, Atanasiu D, Cairns TM, Gallagher JR, Krummenacher C, and Cohen GH (2012). Herpes virus fusion and entry: A story with many characters. Viruses 4, 800–832. 10.3390/v4050800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson RM, and Spear PG (1989). Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D mediates interference with herpes simplex virus infection. J. Virol 63, 819–827. 10.1128/jvi.63.2.819-827.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson DC, Burke RL, and Gregory T (1990). Soluble forms of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D bind to a limited number of cell surface receptors and inhibit virus entry into cells. J. Virol 64, 2569–2576. 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2569-2576.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuller AO, and Lee WC (1992). Herpes simplex virus type 1 entry through a cascade of virus-cell interactions requires different roles of gD and gH in penetration. J. Virol 66, 5002–5012. 10.1128/jvi.66.8.5002-5012.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh A, Preiksaitis J, Ferenczy A, and Romanowski B (2005). The laboratory diagnosis of herpes simplex virus infections. Can. J. Infect Dis. Med. Microbiol 16, 92–98. 10.1155/2005/318294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson NW, Buchan BW, and Ledeboer NA (2014). Light Microscopy, Culture, Molecular, and Serologic Methods for Detection of Herpes Simplex Virus. J. Clin. Microbiol 52, 2–8. 10.1128/JCM.01966-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wald A, and Ashley-Morrow R (2002). Serological testing for herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 and HSV-2 infection. Clin. Infect. Dis 35, S173–S182. 10.1086/342104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson G, Nelson S, Petric M, and Tellier R (2000). Comprehensive PCR-based assay for detection and species identification of human herpesviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol 38, 3274–3279. 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3274-3279.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardella C, Huang ML, Wald A, Magaret A, Selke S, Morrow R, and Corey L (2010). Rapid polymerase chain reaction assay to detect herpes simplex virus in the genital tract of women in labor. Obstet. Gynecol 115, 1209–1216. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e01415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narang J, Singhal C, Mathur A, Sharma S, Singla V, and Pundir CS (2018). Portable bioactive paper based genosensor incorporated with Zn-Ag nanoblooms for herpes detection at the point-of-care. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 107, 2559–2565. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tam PD, Tuan MA, Aarnink T, and Chien ND (2008). Directly immobilized DNA sensor for label-free detection of herpes virus In 2008 International Conference on Technology and Applications in Biomedicine (ITAB), pp. 214–218. 10.1109/ITAB.2008.4570538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kara P, Meric B, Zeytinoglu A, and Ozsoz M (2004). Electrochemical DNA biosensor for the detection and discrimination of herpes simplex Type I and Type II viruses from PCR amplified real samples. Anal. Chim. Acta X 518, 69–76. 10.1016/j.aca.2004.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klunder KJ, Nilsson Z, Sambur JB, and Henry CS (2017). Patternable Solvent-Processed Thermoplastic Graphite Electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 12623–12631. 10.1021/jacs.7b06173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovine P, Settembre EC, Bhargava AK, Luftig MA, Lou H, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Krummenacher C, and Carfi A (2011). Structure of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein d bound to the human receptor nectin-1. PLoS Pathog 7, 1–12. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torres MDT, de Araujo WR, de Lima LF, Ferreira AL, and de la Fuente-Nunez C (2021). Low-cost biosensor for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 at the point of care. Matter 4, 2403–2416. 10.1016/j.matt.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randles JEB (1947). Kinetics of rapid electrode reactions. Faraday Discuss 1, 11–19. 10.1039/DF9470100011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Lima LF, Ferreira AL, Torres MDT, de Araujo WR, and de la Fuente-Nunez C (2021). Minute-scale detection of SARS-CoV-2 using a low-cost biosensor composed of pencil graphite electrodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118. e2106724118–e2106724119. 10.1073/pnas.2106724118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreira AL, de Lima LF, Moraes AS, Rubira RJ, Constantino CJ, Leite FL, Delgado-Silva AO, and Ferreira M (2021). Development of a novel biosensor for Creatine Kinase (CK-MB) using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). Appl. Surf. Sci 554, 149565. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.149565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balint R, Cassidy NJ, and Cartmell SH (2014). Conductive polymers: Towards a smart biomaterial for tissue engineering. Acta Biomater 10, 2341–2353. 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Bai J, Dong L, Yang M, Hu Y, Gao L, and Qian H (2021). A Novel Electrochemical Biosensor based on Layered Hydroxide Nanosheets/DNA Composite for the Determination of Phenformin Hydrochloride. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci 16, 210237. 10.20964/2021.02.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farooq U, Ullah MW, Yang Q, Aziz A, Xu J, Zhou L, and Wang S (2020). High-density phage particles immobilization in surface-modified bacterial cellulose for ultra-sensitive and selective electrochemical detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Biosens. Bioelectron 157, 112163. 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng C, Chen J, Nie Z, and Si S (2010). A sensitive and stable biosensor based on the direct electrochemistry of glucose oxidase assembled layer-by-layer at the multiwall carbon nanotube-modified electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron 26, 213–219. 10.1016/j.bios.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cruz J, Kawasaki M, and Gorski W (2000). Electrode coatings based on chitosan scaffolds. Anal. Chem 72, 680–686. 10.1021/ac990954b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanssen BL, Siraj S, and Wong DK (2016). Recent strategies to minimise fouling in electrochemical detection systems. Rev. Anal. Chem 35, 1–28. 10.1515/revac-2015-0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Annu, and Raja AN (2020). Recent development in chitosan-based electrochemical sensors and its sensing application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 164, 4231–4244. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suginta W, Khunkaewla P, and Schulte A (2013). Electrochemical Biosensor Applications of Polysaccharides Chitin and Chitosan. Chem. Rev 113, 5458–5479. 10.1021/cr300325r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hlavatá L, Vyskočil V, Beníková K, Borbélyová M, and Labuda J (2014). DNA-based biosensors with external Nafion and chitosan membranes for the evaluation of the antioxidant activity of beer, coffee, and tea. Open Chem 12, 604–611. 10.2478/s11532-014-0516-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang L, Ren X, Tang F, and Zhang L (2009). A practical glucose biosensor based on Fe3O4 nanoparticles and chitosan/nafion composite film. Biosens. Bioelectron 25, 889–895. 10.1016/j.bios.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang H, Jung S, Jeong S, Kim G, and Lee K (2015). Polymer-metal hybrid transparent electrodes for flexible electronics. Nat. Commun 6, 6503–6507. 10.1038/ncomms7503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farmani MR, Peyman H, and Roshanfekr H (2020). Blue luminescent graphene quantum dot conjugated cysteamine functionalized-gold nanoparticles (GQD-AuNPs) for sensing hazardous dye. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc 229, 117960. 10.1016/j.saa.2019.117960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottschalk PG, and Dunn JR (2005). The five-parameter logistic: A characterization and comparison with the four-parameter logistic. Anal. Biochem 343, 54–65. 10.1016/j.ab.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holstein CA, Griffin M, Hong J, and Sampson PD (2015). Statistical Method for Determining and Comparing Limits of Detection of Bioassays. Anal. Chem 87, 9795–9801. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tam PD, Tuan MA, Huy TQ, Le AT, and Hieu NV (2010). Facile preparation of a DNA sensor for rapid herpes virus detection. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 30, 1145–1150. 10.1016/j.msec.2010.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toldrà A, Furones MD, O’Sullivan CK, and Campàs M (2020). Detection of isothermally amplified ostreid herpesvirus 1 DNA in Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) using a miniaturised electrochemical biosensor. Talanta 207, 120308. 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia LF, Silvio Batista Rodrigues E, Rocha Lino de Souza G, Jubé Wastowski I, Mota de Oliveira F, Torres Pio dos Santos W, and Souza Gil E (2020). Impedimetric Biosensor for Bovine Herpesvirus Type 1-Antigen Detection. Electroanalysis 32, 1100–1106. 10.1002/elan.201900606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loughman T, Singh B, Seddon B, Noone P, and Santhosh P (2017). Validation of a membrane touch biosensor for the qualitative detection of IgG class antibodies to herpes simplex virus type 2. Analyst 142, 2725–2734. 10.1039/C7AN00666G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nahar S, Ahmed MU, Safavieh M, Rochette A, Toro C, and Zourob M (2015). A flexible and low-cost polypropylene pouch for naked-eye detection of herpes simplex viruses. Analyst 140, 931–937. 10.1039/c4an01701c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kessler HH, Mühlbauer G, Rinner B, Stelzl E, Berger A, Dörr HW, Santner B, Marth E, and Rabenau H (2000). Detection of herpes simplex virus DNA by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol 38, 2638–2642. 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2638-2642.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perkins JD (2007). Detection and Diagnosis of Herpes Simplex Virus Infection in Adults with Acute Liver Failure. Liver Transplant 13, 767–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burrows J, Nitsche A, Bayly B, Walker E, Higgins G, and Kok T (2002). Detection and subtyping of Herpes simplex virus in clinical samples byLightCycler PCR, enzyme immunoassay and cell culture. BMC Microbiol 2, 12–17. 10.1186/1471-2180-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, and Robinson CC (2018). Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates. J. Clin. Microbiol 56, e00632-18–e00635. 10.1128/JCM.00632-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krumbholz A, Schäfer M, Lorentz T, and Sauerbrei A (2019). Quadruplex real-time PCR for rapid detection of human alphaherpesviruses. Med. Microbiol. Immunol 208, 197–204. 10.1007/s00430-019-00580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MultiCode®-RTx Herpes Simplex Virus 1 & 2 Kit, Real-Time PCR Qualitative Detection and Typing of HSV-1 or HSV-2, Luminex Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- 49.BD ProbeTec™ Herpes Simplex Viruses (HSV 1 & 2) Qx Amplified DNA Assays, BD Diagnostic Systems, Becton Dickinson & CO. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim HJ, Tong Y, Tang W, Quimson L, Cope VA, Pan X, Motre A, Kong R, Hong J, Kohn D, et al. (2011). A rapid and simple isothermal nucleic acid amplification test for detection of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. J. Clin. Virol 50, 26–30. 10.1016/J.JCV.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geraghty RJ, Fridberg A, Krummenacher C, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, and Spear PG (2001). Use of chimeric nectin-1(HveC)-related receptors to demonstrate that ability to bind alphaherpesvirus gD is not necessarily sufficient for viral entry. Virology 285, 366–375. 10.1006/viro.2001.0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferreira AL, de Lima LF, Torres MDT, de Araujo WR, and de la Fuente-Nunez C (2021). Low-Cost Optodiagnostic for Minute-Time Scale Detection of SARS-CoV-2. ACS Nano 15, 17453–17462. 10.1021/acsnano.1c03236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elveborg S, Monteil VM, and Mirazimi A (2022). Methods of Inactivation of Highly Pathogenic Viruses for Molecular, Serology or Vaccine Development Purposes. Pathogens 11, 271. 10.3390/pathogens11020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carfí A, Willis SH, Whitbeck JC, Krummenacher C, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, and Wiley DC (2001). Herpes Simplex Virus Glycoprotein D Bound to the Human Receptor. Mol. Cell 8, 169–179. 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krummenacher C, Nicola AV, Whitbeck JC, Lou H, Hou W, Lambris JD, Geraghty RJ, Spear PG, Cohen GH, and Eisenberg RJ (1998). Herpes Simplex Virus Glycoprotein D Can Bind to Poliovirus Receptor-Related Protein 1 or Herpesvirus Entry Mediator, Two Structurally Unrelated Mediators of Virus Entry. J. Virol 72, 7064–7074. 10.1128/JVI.72.9.7064-7074.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hook LM, Harvey M, and Friedman SA (2021). Guinea Pig and Mouse Models for Genital Herpes Infection. Curr Protoc 1, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Awasthi S, Hook LM, Shaw CE, Pahar B, Stagray JA, Liu D, Veazey RS, and Friedman HM (2017). An HSV-2 Trivalent Vaccine Is Immunogenic in Rhesus Macaques and Highly Efficacious in Guinea Pigs. PLoS Pathog 13, e1006141. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated in this study will be made available upon reasonable request.