Abstract

The structure–activity relationships (SAR) of alkylxanthine derivatives as antagonists at the recombinant human adenosine receptors were explored in order to identify selective antagonists of A2B receptors. The effects of lengthening alkyl substituents from methyl to butyl at 1- and 3-positions and additional substitution at the 7- and 8-positions were probed. Ki values, determined in competition binding in membranes of HEK-293 cells expressing A2B receptors using 125I-ABOPX (125I-3-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)-8-(phenyl-4-oxyacetate)-1-propylxanthine), were approximately 10 to 100 nM for 8-phenylxanthine functionalized congeners. Xanthines containing 8-aryl, 8-alkyl, and 8-cycloalkyl substituents, derivatives of XCC (8-[4-[[[carboxy]methyl]oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthine) and XAC (8-[4-[[[[(2-aminoethyl)amino]carbonyl]methyl]-oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthine), containing various ester and amide groups, including L- and D-amino acid conjugates, were included. Enprofylline was 2-fold more potent than theophylline in A2B receptor binding, and the 2-thio modification was not tolerated. Among the most potent derivatives examined were XCC, its hydrazide and aminoethyl and fluoroethyl amide derivatives, XAC, N-hydroxyethyl-XAC, and the L-citrulline and D-p-aminophenylalanine conjugates of XAC. An N-hydroxysuccinimide ester of XCC (XCC-NHS, MRS 1204) bound to A2B receptors with a Ki of 9.75 nM and was the most selective (at least 20-fold) in this series. In a functional assay of recombinant human A2B receptors, four of these potent xanthines were shown to fully antagonize the effects of NECA-induced stimulation of cyclic AMP accumulation.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptors, radioligand, alkylxanthines, structure–activity relationships, purines, cyclic AMP

INTRODUCTION

Adenosine receptors (ARs) are G protein-coupled receptors that have regulatory functions in the cardiovascular, renal, and immune systems and in the central nervous system, and four subtypes have been cloned [Linden and Jacobson, 1998]. The A2B AR subtype [Daly et al., 1983; Stehle et al., 1992; see review, Feoktistov and Biaggioni, 1997] has been found to be involved in the control of cell growth and gene expression [Neary et al., 1996], vasodilatation [Martin et al., 1993] and fluid secretion from intestinal epithelia [Strohmeier et al., 1995].

Until recently, it was not possible to measure A2BARs by radioligand binding. The structure–activity relationships (SAR) of adenosine derivatives as A2B receptor agonists were explored by functional assays of cyclic AMP accumulation. In COS cell expressing recombinant human A2B receptors, the most potent agonist out of 109 derivatives examined was NECA, a nonselective receptor probe [de Zwart et al., 1998]. Among antagonists examined in functional assays, the non-xanthine enprofylline is approximately 10-fold selective for A2B vs. A1 and A2A ARs [Brackett and Daly, 1994]. Alkylxanthines are the classical antagonists for ARs and have considerable potency at the A2B subtype [Bruns, 1981; Jacobson et al., 1985a; Brackett and Daly, 1994], although the absence of radioligand binding assays has precluded a detailed investigation of the SAR of xanthines.

Since adenosine evokes mast cell degranulation in the lungs of asthmatics [Cushley and Holgate, 1985], enprofylline is a selective antagonist of A2BARs in functional assays [Brackett and Daly, 1994], and enprofylline is used therapeutically to treat asthma [Clarke et al., 1989], it was suggested that activation of A2BARs by adenosine might be responsible for triggering mast cell degranulation. However, the A3AR was identified as the AR subtype that mediates the degranulation of rat RBL mast-like cells [Ramkumar et al., 1993], and recombinant human A3ARs were found to be weakly blocked by enprofylline [Salvatore et al., 1993]. However, it has recently been shown that some mast cells do express A2BARs. In canine BR mastocytoma cells, A2BARs appear to be responsible for triggering acute Ca2+ mobilization and degranulation [Auchampach et al., 1997]. A2BARs also participate in a delayed IL8 release from human HMC-1 mast cells [Feoktistov and Biaggioni, 1995].

As in other cell types, A2BARs in mast cells are coupled to Gs and cyclic AMP accumulation. However, recent studies indicate that A2BARs also mobilize calcium and activate MAP kinase by dual signaling through Gs and Gq. The latter pathway is probably involved in the degranulation and cytokine release responses of mast cells [Gao et al., 1998].

A possible role for mast cell A2BARs in asthma is consistent with the therapeutic efficacy of theophylline and enprofylline. In radioligand binding assays, both of these xanthines were confirmed to block human A2BARs in the therapeutic dose range, and enprofylline was found to be a weak (Ki = 7 μM), partially selective antagonist of human A2BARs [Robeva et al., 1996b]. In order to identify AR subtype-selective antagonists that are more potent than enprofylline, we utilized in this study a radioligand binding assay based on the use of membranes derived from HEK-293 cells that overexpress recombinant human A2BARs and the potent, nonselective radioligand, 125I-ABOPX (125I-3-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)-8-(phenyl-4-oxyacetate)-1-propylxanthine).

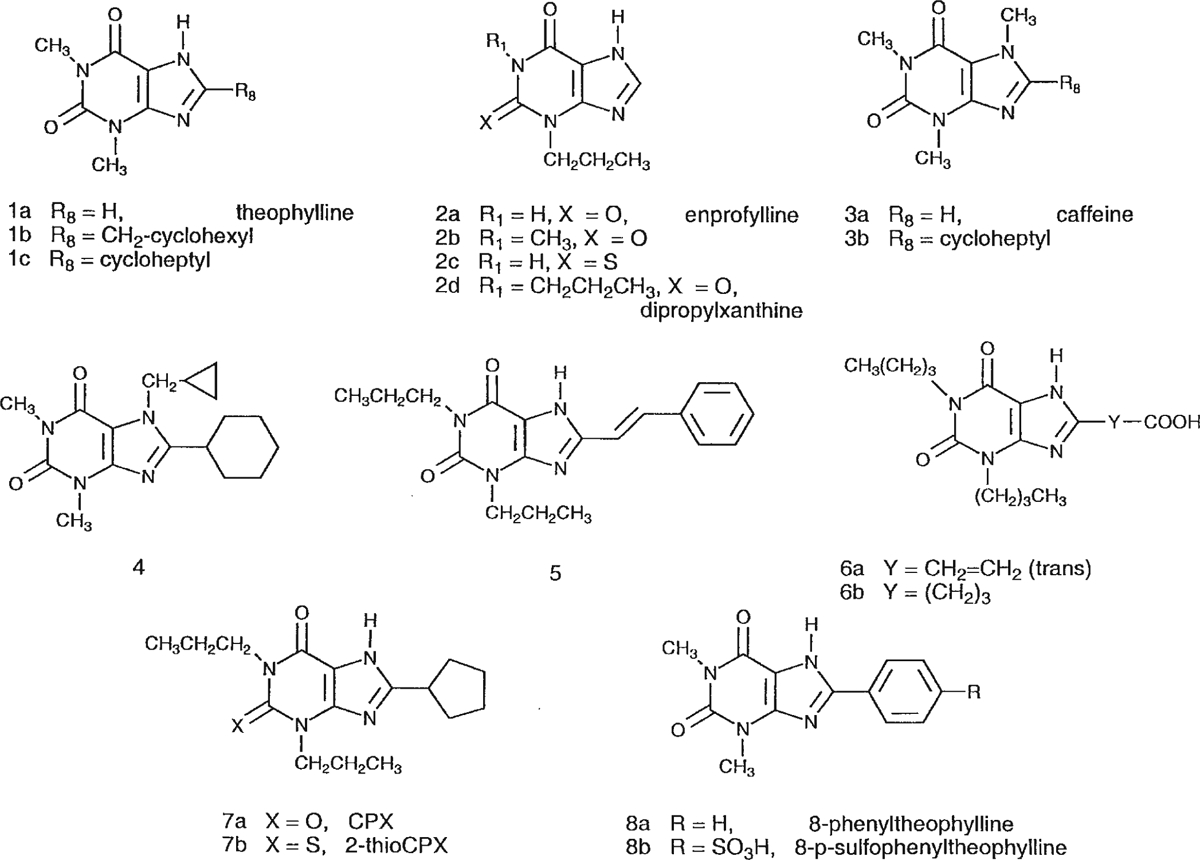

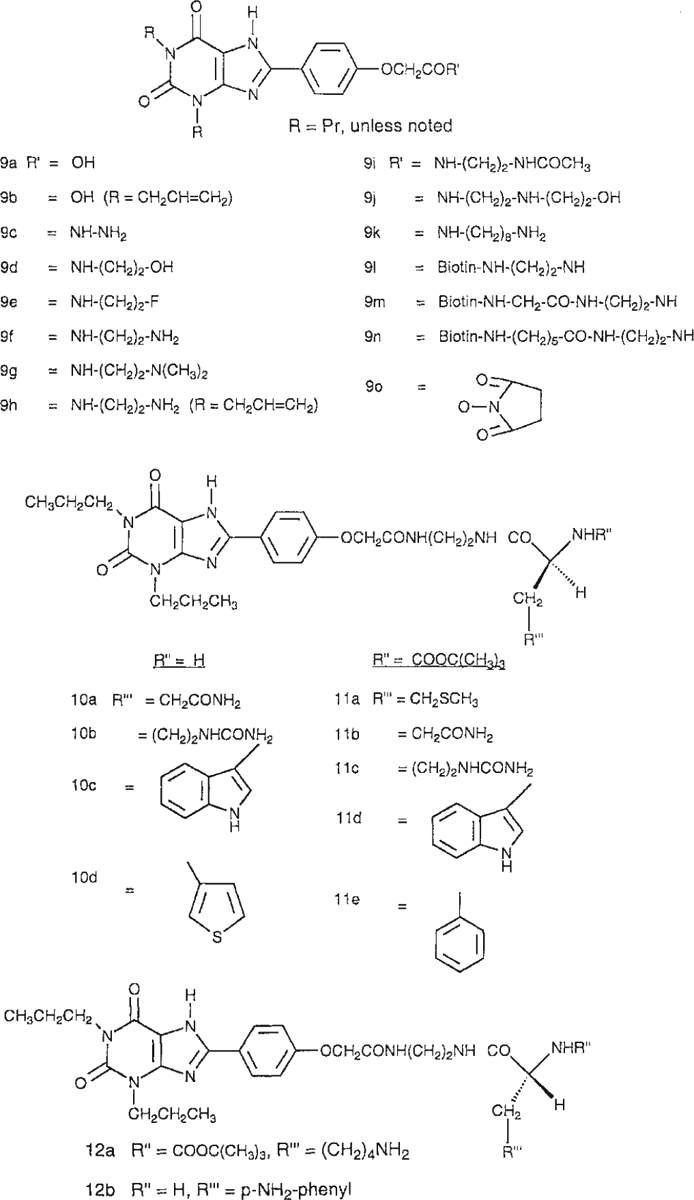

AR subtype-selective probes are available for the A1, A2A, and A3 ARs [Jacobson and van Rhee, 1997]. As an approach to finding selective antagonists for the A2B receptor, we screened a series of known xanthines for binding to the recombinant human A2B receptor and, in some cases, to the other AR subtypes. The derivatives screened ranged from simple alkyl-substituted xanthines (Fig. 1) to functionalized congeners [Jacobson et al., 1986] of larger molecular weight, derived from 1,3-dipropyl-8-phenylxanthines, and their amino acid conjugates (Fig. 2). Leads for achieving moderate selectivity (at least 20-fold vs. A1, A2A, and A3 ARs) have been found in the category of complex 8-phenylxanthine derivatives.

Fig. 1.

Structures of simple xanthines screened as A2B receptor antagonists.

Fig. 2.

Structures of xanthine functionalized congeners derived from 1,3-dipropyl-8-phenylxanthine and their amino acid conjugates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

NECA, R-PIA, XAC, theophylline, caffeine, enprofylline, and 2-chloroadenosine were purchased from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA). Other xanthine derivatives have been synthesized as reported [Jacobson et al., 1985a,b, 1986, 1988, 1989, 1993, 1995; Kim et al., 1994; Shamim et al., 1989].

Pharmacology

The human A2B receptor cDNA was subcloned into the expression plasmid pDoubleTrouble [Robeva et al., 1996a]. The plasmid was amplified in competent JM109 cells and plasmid DNA isolated using Wizard Megaprep columns (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). A2B ARs were introduced into HEK-293 cells by means of lipofectin [Felgner et al., 1987]. Colonies were selected by growth of cells in 0.6 mg/ml G418. Transfected cells were maintained in DMEM/F12 medium with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 0.3 mg/ml G418.

Radioligand binding studies

Confluent monolayers of HEK-A2B cells were washed with PBS followed by ice-cold buffer A (10 mM Hepes, 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) with protease inhibitors (10 mg/ml benzamidine, 100 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, and 2 mg/ml each of aprotinin, pepstatin, and leupeptin). The cells were homogenized in a Polytron (Brinkmann) for 20 sec, centrifuged at 30,000g, and the pellets washed twice with buffer HE (10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 with protease inhibitors). The final pellet was resuspended in buffer HE, supplemented with 10% sucrose, and frozen in aliquots at −808C. For binding assays, membranes were thawed and diluted 5–10-fold with HE to a final protein concentration of approximately 1 mg/ml. To determine protein concentrations, membranes, and bovine serum albumin standards were dissolved in 0.2% NaOH/0.01% SDS and protein determined using fluorescamine fluorescence [Stowell et al., 1978]. Saturation binding assays for human A2B ARs were performed with 125I-ABOPX (2,200 Ci/mmol). To prepare 125I-ABOPX, 10 μl of 1 mM ABOPX in methanol/1 M NaOH (20:1) was added to 50 μl of 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.3. One or 2 mCi of Na125I was added, followed by 10 μl of 1 mg/ml chloramine T in water. After incubating for 20 min at room temperature, 50 μl of 10 mg/ml Na-metabisulfite in water was added the quench the reaction. The reaction products were applied to a C18 HPLC column using 4 mM phosphate, pH 6.0/methanol. After 5 min in 35% methanol, the methanol concentration was ramped to 100% over 15 min. Unreacted ABOPX eluted in 11–12 min; 125I-ABOPX eluted at 18–19 min in a yield of 50–60% of the initial 125I. In equilibrium binding assays, the ratio of 127I/125I-ABOPX was 10–20/1. Radioligand binding experiments were performed in triplicate with 20–25 μg membrane protein in a total volume of 0.1 ml HE buffer supplemented with 1 U/ml adenosine deaminase and 5 mM MgCl2. The incubation time was 3 h at 21°C. Nonspecific binding was measured in the presence of 100 mM NECA. Competition experiments were carried out using 0.6 nM 125I-ABOPX. Membranes were filtered on Whatman GF/C filters using a Brandel cell harvester (Gaithersburg, MD) and washed three times over 15–20 sec with ice-cold buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4). Bmax and KD values were calculated by Marquardt’s [1963] nonlinear least-squares interpolation for single site binding models. Ki values for different compounds were derived from IC50 values as described previously [Linden, 1982]. Data from replicate experiments are tabulated as means ± SEM.

[3H]CPX, 125I-ZM241385, and 125I-ABA were utilized in radioligand binding assays to membranes derived from HEK-293 cells expressing recombinant human A1, A2A, and A3 ARs, respectively. Binding of [3H]R-N6-phenylisopropyladenosine ([3H]R-PIA, Amersham, Chicago, IL) to A1 receptors from rat cerebral cortical membranes and of [3H]CGS 21680 (Dupont NEN, Boston, MA) to A2A receptors from rat striatal membranes was performed as described previously [Schwabe and Trost, 1980; Jarvis et al., 1989]. Adenosine deaminase (3 units/mL) was present during the preparation of the brain membranes, in a preincubation of 30 min at 30°C, and during the incubation with the radioligands. All nonradioactive compounds were initially dissolved in DMSO and diluted with buffer to the final concentration, where the amount of DMSO never exceeded 2%. Incubations were terminated by rapid filtration over Whatman GF/B filters using a Brandell cell harvester (Brandell). The tubes were rinsed three times with 3 mL buffer each.

At least six different concentrations of competitor, spanning 3 orders of magnitude adjusted appropriately for the IC50 of each compound, were used. IC50 values, calculated with the nonlinear regression method implemented in Prism (Graph-Pad, San Diego, CA), were converted to apparent Ki values as described previously [Linden, 1982]. Hill coefficients of the tested compounds were in the range of 0.8–1.1.

Cell Culture

Transfected CHO and HEK cells were grown under 5% CO2 / 95% O2 humidified atmosphere at a temperature of 37°C in DMEM supplemented with Hams F12 nutrient mixture (1/1), 10% newborn calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, and containing 50 IU/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.2 mg/mL geneticin (G418, Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). Cells were cultured in 10-cm round plates and subcultured when grown confluent (approximately after 72 h). PBS/EDTA containing 0.25% trypsin (CHO cells only) was used for detaching the cells from the plates. Experimental cultures were grown overnight as a monolayer in 24-well tissue culture plates (400 μL/well; 0.8 × 106 cells/well). CHO-A2B cells were kindly provided by Dr. K.-N. Klotz (University of Würzburg, Germany).

Cyclic AMP Accumulation

Cyclic AMP generation was performed in DMEM/HEPES buffer (DMEM containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 37°C). Each well of cells was washed twice with DMEM/HEPES buffer, then 100 μL adenosine deaminase (final concentration 10 IU/mL) and 100 μL of solutions of rolipram and cilostamide (each at a final concentration of 10 μM) were added, followed by 50 μL of the test compound (appropriate concentration) or buffer. After incubation for 40 min at 37°C, 100 μL NECA was added (final concentration 50 μM for compound screening and IC50 determination, appropriate concentrations for recording dose–response curves for pA2 calculations). After 15 min, incubation at 37°C was terminated by removing the medium and adding 200 μL of 0.1 M HCl. Wells were stored at −20°C until assay. The amounts of cyclic AMP were determined following a protocol which utilized a cAMP binding protein (PKA) [van der Wenden et al., 1995], with the following minor modifications. The assay buffer consisted of 150 mM K2HPO4 / 10 mM EDTA / 0.2% BSA FV at pH 7.5. Samples (20 μL) were incubated for 90 min at 0°C. Incubates were filtered over GF/C glass microfiber filters in a Brandel M-24 Cell Harvester. The filters were additionally rinsed with 4 × 2 mL 150 mM K2HPO4/10 mM EDTA (pH 7.5, 4°C). Punched filters were counted in Packard Emulsifier Safe scintillation fluid after 2 h of extraction.

RESULTS

The structures of the xanthine derivatives tested for affinity in radioligand binding assays at ARs are shown in Figures 1 and 2. Simple xanthines (unsubstituted at the 8-position, compounds 1a, 2, and 3a) and various 8-alkyl (1b, 6b), 8-cycloalkyl (1c, 3b, 4, and 7), 8-vinyl (5, 6a), and 8-phenyl derivatives (8) were included. XCC (8-[4-[[[carboxy]methyl]oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthine) [Jacobson et al., 1985], 9a, various amide derivatives, 9c–9n, and an ester derivative, 9o, were also evaluated in binding to the human A2B receptor. Among the amide derivatives are XAC (8-[4-[[[[(2-aminoethyl)amino]carbonyl]methyl]oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthine), 9f, and its conjugates [Jacobson et al., 1986], including those containing L-amino acids (10), Nα-t-Boc-protected L-amino acids (11), and Nα-t-Boc-protected D-amino acids (12).

At A2B receptors, both a binding assay (Table 1) and a functional assay were used. Ki values of xanthine derivatives in displacement of membrane binding of 125I-ABOPX at human A2B receptors expressed in HEK-293 cells were determined [Linden, 1998]. [3H]CPX, 7a, has also been used as a radioligand for human A2B receptors in binding experiments [IJzerman, 1998] using whole cells, but we used 125I-ABOPX due to its higher affinity and specific radioactivity.

TABLE 1.

Affinity of Xanthine Derivatives at Human A2B Receptors Expressed in HEK-293 Cells*

| Compound | hA2B Ki (nM) |

Other subtypes | Methods | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2A | A3 | |||

| 1a | 9,070 ± 1500 | 8740 | 25,300 | a | |

| 6,920 ± 160 | 6,700 ± 320 | 22,300 ± 1,100 | c | ||

| 1b | 13,000 ± 3,700 | 610 | 5,470 | b | |

| 1c | 8,500 ± 1,800 | 65.9 | 1,050 | b | |

| 2a | 4,730 ± 270 | 81,000 | a | ||

| 42,000 ± 4,200 | 81,300 ± 10,700 | 92,600 ± 3,400 | c | ||

| 2b | 1,810 ± 120 | ||||

| 2c | >100,000 | ||||

| 2d | 609 ± 119 | 450 | 5,160 | a | |

| 607 ± 299 | 1,670 ± 110 | 1,940 ± 150 | c | ||

| 3a | 10,400 ± 1,800 | 29,000 | 48,000 | b | |

| 10,700 ± 4,900 | 9,560 ± 670 | 13,300 ± 4,700 | c | ||

| 3b | >100,000 | 19,500 | 3,270 | b | |

| 4 | >10,000 | 8,230 | 4,530 | b | |

| 5 | 340 ±150 | 55 | 44 | b | |

| 6a | 1,960 ± 240 | 3,370 | 16,500 | b | |

| 6b | 24,000 ± 1,600 | 14,200 | 113,000 | b | |

| 7a | 56 ± 8 | 0.9 | a | ||

| 7b | 2,800 ± 1,400 | 0.66 | 314 | a | |

| 8a | 415 ± 219 | 760 | a | ||

| 1,340 ± 290 | 454 ± 52 | 1,250 ± 80 | c | ||

| 8b | 1,330 ± 216 | 1,000 | a | ||

| 4,200 ± 440 | 7,050 ± 1,110 | 5,890 ± 1,050 | c | ||

| 9a | 13.6 ± 1.2 | 58 | 2,200 | d | |

| 9b | 99.7 ± 8.8 | ||||

| 9c | 14.0 ± 3.3 | 323 | 20.9 | 217 | c |

| 9d | 11.1 ± 2.8 | 10.2 | a | ||

| 9e | 9.93 ± 2.23 | 23.4 | a | ||

| 9f | 7.80 ± 0.14 | 1.2 | 63 | d | |

| 9 g | 68 ± 9 | 2.8 | 5.0 | d | |

| 9h | 81.9 ± 5.0 | ||||

| 9i | 27.2 ± 7.3 | 24 | 530 | d | |

| 9j | 19.3 ± 2.3 | 1.16 | a | ||

| 9k | 53.0 ± 4.0 | 255 | 23.9 | 169 | c |

| 9l | 173 ± 25 | 54 | e | ||

| 9m | 784 ± 258 | e | |||

| 9n | 1,060 ± 190 | 50 | e | ||

| 9o | 9.75 ± 4.70 | 153 | 127 | 227 | c |

| 10a | 104 ± 12 | 8.5f | e | ||

| 10b | 18.3 ± 2.6 | 127 | 44.3 | 76.0 | c |

| 10c | 20.8 ± 3.3 | 12.7f | e | ||

| 10d | 6.87 ± 2.60 | 2.6f | e | ||

| 20.6 | 18.4 | 92.7 | c | ||

| 11a | 392 ± 50 | 44f | e | ||

| 11b | 178 ± 55 | 13.2f | e | ||

| 11c | 153 ± 25 | 104f | e | ||

| 11d | 347 ± 44 | 118f | e | ||

| 11e | 1,510 ± 180 | 92f | e | ||

| 12a | 153 ± 84 | ||||

| 12b | 19.9 ± 0.8 | ||||

As determined in a binding assay using [125I]-ABOPX as radioligand and at A1, A2A, and A3 adenosine receptors, as determined in previousa,b and in the presentc study (radioligands and species used are given in footnotes, and error values for archival data are in the references provided). Ki values, unless noted, are given in nM.

Ki values were determined in radioligand binding assays at rat cortical A1 receptors vs. [3H]R-PIA [Jacobson et al., 1988, 1989; Shamim et al., 1989].

Ki values were determined in radioligand binding assays at rat cortical A1 receptors vs. [3H]R-PIA and at rat striatal A2A receptors vs. [3H]CGS 21680 [Jacobson et al., 1993, 1995; Kim et al., 1994].

Ki values were determined in radioligand binding assays at recombinant human A1 and A2A receptors expressed in HEK-293 cells vs. [3H]CPX and [125I]ZM241385, respectively. Affinity at recombinant human A3 receptors expressed in HEK-293 cells was determined using [125I]ABA.

Ki values were determined in radioligand binding assays at rat cortical A1 receptors vs. [3H]R-PIA and at rat striatal A2A receptors vs. [3H]NECA [Daly and Jacobson, 1989].

Ki or IC50 values were determined in radioligand binding assays at rat cortical A1 receptors vs. [3H]CHA [Jacobson et al., 1985b, 1986].

IC50 value.

Affinity of 2b, 2c, 9b, 9h, 9m, 12a, and 12b at non-A2B receptors was not determined.

The naturally occurring xanthine antagonists theophylline and caffeine, 1a and 3a, respectively, displaced radioligand binding at A2B receptors, with Ki values of 9.07 and 10.4 μM, consistent with previous functional studies [Brackett and Daly, 1994]. Extension of the 1,3-methyl groups of theophylline, in 1,3-dipropylxanthine, 2d, enhanced affinity 15-fold. Substitution of xanthine with a propyl group only at the 3-position in enprofylline, 2a, resulted in 2-fold greater A2B receptor affinity (Ki value 4.73 μM) than theophylline. 1-Methyl-enprofylline, 2b, was more potent in binding (Ki value 1.8 μM) than enprofylline, while 2-thioenprofylline, 2c, did not bind to A2B receptors.

At the 8-position, a cycloheptyl or cyclohexyl group, only in the absence of N-7 substitution, was tolerated in A2B receptor binding (cf. 1c and 3b, 4). The 8-cyclopentyl analog CPX, 7a, was very potent in A2B receptor binding, with a Ki value of 56 nM, while the corresponding 2-thio derivative, 7b, was 50-fold less potent. The 8-styryl group was well tolerated at A2B receptors (cf. 1,3-dipropyl analogs, 2d and 5). The 8-phenyl group present in the theophylline analog 8a resulted in a 22-fold enhancement of affinity at A2B receptors.

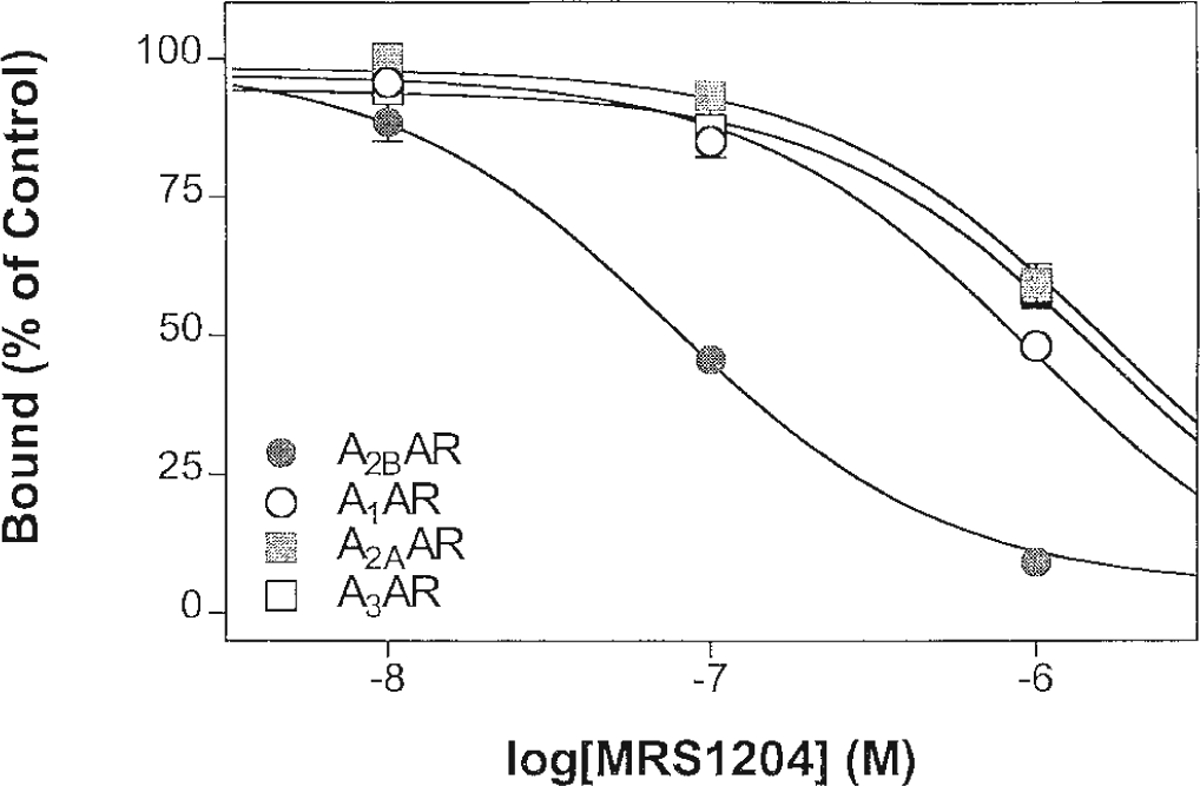

Among anionic derivatives, both carboxylic acids, 6a and 6b, and a sulfonate, 8b (8-SPT), were examined for A2B receptor affinity. Compounds 6a and 8b displayed micromolar affinity, while 6b was less potent. In the series of 8-phenylxanthine functionalized congeners (Fig. 2), several carboxylic acid (9a, 9b) and amine derivatives (9f–h, 9k) were included, in addition to amino acid conjugates (10 and 12). The charged 1,3-dipropyl derivatives, 9a and 9f, were approximately one order of magnitude more potent in binding at A2B receptors than the corresponding 1,3-diallylxanthines (9b and 9h). There was no clear pattern of preference for amino vs. carboxylic acid vs. neutral derivatives at A2B receptors. Among the most potent derivatives examined (compound numbers and Ki values in nM given in parentheses) were XCC (9a, 13.6), its hydrazide (9c, 14.0) and hydroxyethyl (9d, 11.1), and fluoroethyl (9e, 9.93) amide derivatives, XAC (9f, 7.80), N-hydroxyethyl-XAC (9j, 19.3), and the L-citrulline (10b, 18.3), and D-p-aminophenylalanine (12b, 19.9) conjugates of XAC. Acetylation of XAC, in 9i, resulted in a 4-fold loss of affinity. The neutral biotin conjugates, of various chain lengths (9l–9m), were considerably less potent in binding than the parent amine XAC, 9f. The N-hydroxysuccinimide ester of XCC (MRS 1204), 9o, displayed the highest potency in the A2B receptor binding assay among the present xanthine derivatives, with a Ki value of 9.75 nM (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Competition for radioligand binding by compound 9o at recombinant human A1 (●) A2A (○), A2B (■), and A3 (□) receptors.

Among L-amino acid conjugates, 10, differences in affinity at A2B receptors were observed, depending on the amino acid sidechain. XAC conjugates of Cit, 10b, and aromatic amino acids, 10c–10e, were clearly more potent than the conjugate of Gln, 10a, and approximately equipotent to XAC at A2B receptors. The most potent amino acid conjugate was a derivative of L-thienylalanine, 10d, which had a Ki value of 6.9 nM at human A2B receptors. The conjugates of Boc-protected amino acids, 11 and 12a, were considerably less potent than the unprotected analogs.

The p-aminophenylalanyl conjugate, 12b, which had a Ki value of 20 nM at A2B receptors, was included for potential radioiodination for use as a radioligand; however, in preliminary iodination experiments the iodinated product following HPLC purification was not a useful radioligand for the characterization of human A2B receptors.

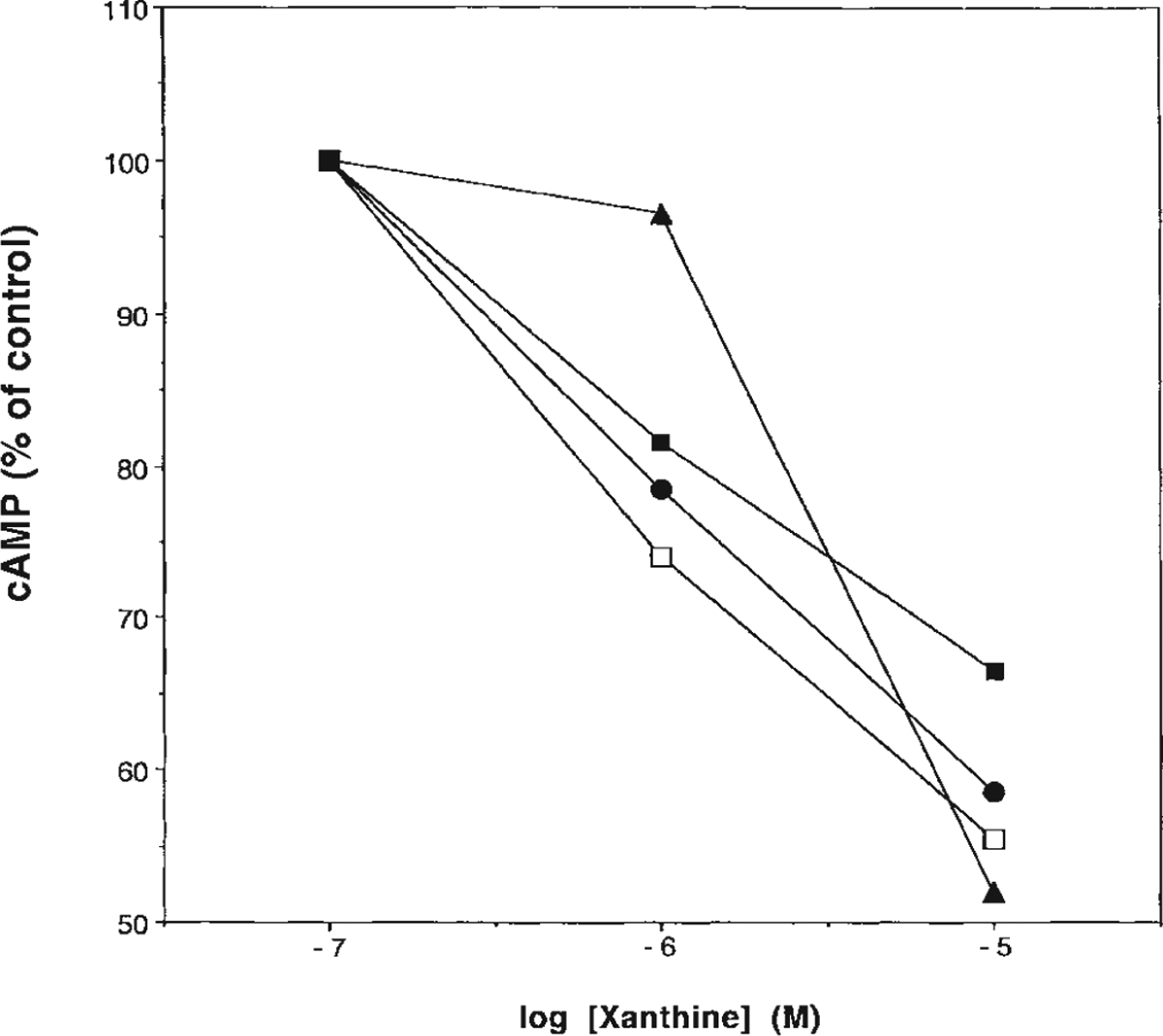

In order to demonstrate functional antagonism via A2B receptors, the effects of selected xanthines on agonist-induced cyclic AMP production in cells expressing the human receptor were determined for several of the most active derivatives, 9c, 9i, 9o, and 10e, and are shown in Figure 4. cAMP stimulation by NECA in a Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line stably transfected with human A2B receptor cDNA was observed in the absence and presence of three increasing concentrations of these antagonists. The analogs were used at concentrations from 0.1–10 μM in the presence of 50 μM 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA). All four analogs inhibited the effects of NECA in a concentration-dependent manner. IC50 values were not determined; however, the most potent analog appeared to be compound 9c, the hydrazide of XCC. The apparent lower potency of 9o may be related to ester hydrolysis.

Fig. 4.

Effects of several of the most potent xanthine derivatives (9c □,; 9i, ●; 9o, ▲; and 12b, ■) on NECA-induced cyclic AMP accumulation in CHO-A2B cells; 100% stimulation refers to cAMP stimulation by 50 μM NECA.

In order to evaluate selectivity, selected derivatives were subjected to standard binding assays at A1, A2A, and A3 receptors. The Ki values at non-A2B receptors, determined in previous studies and in the present study, are shown in Table 1. In the present study, Ki values were determined in radioligand binding assays at recombinant human A1 receptors (vs. [3H]CPX, [3H]8-cyclopentyl-1, 3-dipropylxanthine) and human A2A receptors (vs. 125I-ZM241385, 125I-4-(2-[7-amino-2-[2-furyl][1,2,4]tri-azolo[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-yl-amino]ethyl)phenol) [Palmer et al., 1996]. Affinity at cloned human A3 receptors expressed in HEK-293 cells was determined using 125I-ABA (N6-(4-amino-3-[125I]iodobenzyl)-adenosine).

Among the xanthines found most potent in A2B receptor binding (see above), the degree of selectivity was highly variable. Thus, the highly potent analogs 9e and 9f proved to be nonselective for A2B receptors vs. A1 receptors, while the N-hydroxysuccinimide ester, 9o, proved to be at least 20-fold selective in binding assays.

DISCUSSION

There is a need to develop new tools to study A2B adenosine receptors due to a lack of high affinity radioligands and a lack of selective agonists and antagonists. In this study, we describe the synthesis and characterization of novel antagonists, such as 9o, that are the first potent and selective antagonists of recombinant human A2B adenosine receptors.

The A2BAR has not been investigated carefully due to the absence of useful tools to study it. Thus, until recently, the potency of compounds that bind to A2BARs has been assessed by functional assays such as cyclic AMP accumulation [Brackett and Daly, 1994]. The functional potency of XAC, XCC, and other 8-phenylxanthines such as A2BAR antagonists in brain slices was reported [Jacobson et al., 1985] and is consistent with the present results. In this study, we determined the potency of competitive antagonists in competition for 125I-ABOPX binding to overexpressed recombinant human adenosine receptors. However, it is still not possible to determine the number of A2B adenosine receptor in tissues, where the density of receptors is too low to be detected by 125I-ABOPX or by other currently available radioligands. The need for improved tools to study these receptors has increased with the recent recognition that A2B receptors are involved in the regulation of a number of interesting and important physiological functions. For example, Madara and co-workers [Resnick et al., 1993; Strohmeier et al., 1995] have demonstrated that in bacterial infection of the gut, eosinophils release AMP, which is rapidly converted to adenosine by an ecto-5′-nucleotidase on epithelial cells; the activation of A2BARs on epithelial cells appears to trigger the fluid and electrolyte efflux elicited by bacterial pathogens. A2B adenosine receptors have also been implicated in the etiology of asthma. Although rodent mast cells appear to degranulate in response to adenosine as a result of A3 adenosine receptor activation [Jin et al., 1997; Ramkumar et al., 1993; Shepherd et al., 1996], recent data indicate that A2B adenosine receptor activation is involved in the degranulation of human and canine mast cells [Auchampach et al., 1997; Feoktistov and Biaggioni, 1995]. Adenosine evokes a mast cell-dependent vasoconstriction in asthmatics, but not in nonasthmatics [Cushley and Holgate, 1985]. Enprofylline is a xanthine that blocks asthmatic bronchoconstriction in response to adenosine but was thought not to block adenosine receptors [Lunell et al., 1982]. Hence, it is particularly provocative and interesting that enprofylline has been found to block the human A2B adenosine receptor in the therapeutic concentration range [Robeva et al., 1996b].

In summary, we used radioligand binding to recombinant human A2B adenosine receptors to begin to identify xanthine antagonists that have high affinity and selectivity for A2B adenosine receptors. These compounds, and even more potent and selective compounds that may be developed in the future, will be useful for characterizing low abundance endogenous A2B receptors in tissues, and for helping to evaluate the physiological role of this poorly studied adenosine receptor subtype.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Melissa Marshall for technical assistance with the binding assays.

Abbreviations:

- AR

adenosine receptor

- CGS

21680 2-[4-[(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl]ethyl-amino]-5′-N-ethylcarbamoyl adenosine

- CHA

N6-cyclohexyladenosine

- CHO cells

Chinese hamster ovary cells

- CPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacatate

- HEK cells

human embryonic kidney cells

- [125I]ABA

[125I]N6-(4-aminobenzyl)-adenosine

- [125I]AB-MECA

[125I]N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide

- 125I-ABOPX

125I-3-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)-8-(phenyl-4-oxyacetate)-1-propylxanthine

- Ki

equilibrium inhibition constant

- NECA

5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimide ester

- R-PIA

R-N6-phenylisopropyladenosine

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- 8-SPT

8-sulfophenyltheophylline

- Tris

tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

- XAC

8-[4-[[[[(2-aminoethyl)amino]carbonyl]methyl]oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- XCC

8-[4-[[[carboxy]methyl]oxy]phenyl]-1,3-dipropylxanthine

REFERENCES

- Alexander SPH, Cooper J, Shine J, Hill SJ. 1996. Characterization of the human brain putative A2B adenosine receptor expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO.A2B.4) cells. Br J Pharmacol 119:1286–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchampach JA, Jin J, Wan TC, Caughey GH, Linden J. 1997. Canine mast cell adenosine receptors: cloning and expression of the A3 receptors and evidence that degranulation is mediated by the A2B receptor. Mol Pharmacol 52:846–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackett LE, Daly JW. 1994. Functional characterization of the A2b adenosine receptor in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. Biochem Pharmacol 47:801–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns RF. 1981. Adenosine antagonism by purines, pteridines and benzopteridines in human fibroblasts. Biochem Pharmacol 30: 325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke H, Cushley MJ, Persson CG, Holgate ST. 1989. The protective effects of intravenous theophylline and enprofylline against histamine- and adenosine 5′-monophosphate-provoked bronchoconstriction: implications for the mechanisms of action of xanthine derivatives in asthma. Pulm Pharmacol 2:147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushley MJ, Holgate ST. 1985. Adenosine-induced bronchoconstriction in asthma: role of mast cell-mediator release. J Allergy Clin Immunol 75:272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly JW, Jacobson KA. 1989. Molecular probes for adenosine receptors. In: Ribeiro JA, editor. Adenosine receptors in the nervous system. London: Taylor and Francis. p 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Daly JW, Butts-Lamb P, Padgett W. 1983. Subclasses of adenosine receptors in the central nervous system: interaction with caffeine and related methylxanthines. Cell Mol Neurobiol 3:69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwart M, Link R, von Frijtag Drabbe K,nzel JK, Cristalli G, Jacobson KA, Townsend-Nicholson A, IJzerman AP. 1998. A screening of adenosine analogues on the human adenosine A2B receptor as part of a search for potent and selective agonists. Nucleos Nucleotid 17:969–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I. 1995. Adenosine A2b receptors evoke interleukin-8 secretion in human mast cells — an enprofylline-sensitive mechanism with implications for asthma. J Clin Invest 96:1979–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I. 1997. Adenosine A2B receptors. Pharmacol Rev 49:381–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felgner PL, Gadek TR, Holm M, Roman R, Chan HW, Wenz M, Northrop JP, Ringold GM, Danielsen M. 1987. Lipofection: a highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:7413–7417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Chen T, Weber MJ, Linden J. 1999. A2B adenosine and P2Y2 receptors stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinase in human embryonic kidney-293 cells: cross-talk between cyclic AMP and protein kinase C pathways. J Biol Chem 274:5972–5980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Kirk KL, Padgett WL, Daly JW. 1985a. Functionalized congeners of 1,3-dialkylxanthines: preparation of analogues with high affinity for adenosine receptors. J Med Chem 28:1334–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Kirk KL, Padgett W, Daly JW. 1985b. Probing the adenosine receptor with adenosine and xanthine biotin conjugates. FEBS Lett 184:30–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Kirk KL, Padgett WL, Daly JW. 1986. A functionalized congener approach to adenosine receptor antagonists: amino acid conjugates of 1,3-dipropylxanthine. Mol Pharmacol 29:126–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, de la Cruz R, Schulick R, Kiriasis L, Padgett W, Pfleiderer W, Kirk KL, Neumeyer JL, Daly JW. 1988. 8-Substituted xanthines as antagonists as A1 and A2-adenosine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 37:3653–3661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Kiriasis L, Barone S, Bradbury BJ, Kammula U, Campagne JM, Daly JW, Neumeyer JL, Pfleiderer W. 1989. Sulfur-containing xanthine derivatives as selective antagonists at A1-adenosine receptors. J Med Chem 32:1873–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Melman N, Fischer B, Maillard M, van Bergen A, van Galen PJM, Karton Y. 1993. Structure-activity relationships of 8-styrylxanthines as A2-selective adenosine antagonists. J Med Chem 36:1333–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Guay-Broder C, van Galen PJM, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Melman N, Eidelman O, Pollard HB. 1995. Stimulation by alkylxanthines of chloride efflux in CFPAC-cells does not involve A1-adenosine receptors. Biochemistry 34:9088–9094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MF, Schutz R, Hutchison AJ, Do E, Sills MA, Williams M. 1989. [3H]CGS 21680, an A2 selective adenosine receptor agonist directly labels A2 receptors in rat brain tissue. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 251:888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Shepherd RK, Duling BR, Linden J. 1997. Inosine binds to A3 adenosine receptors and stimulates mast cell degranulation. J Clin Invest 100:2849–2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HO, Ji X-d, Melman N, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 1994. Structure activity relationships of 1,3-dialkylxanthine derivatives at rat A3-adenosine receptors. J Med Chem 37:3373–3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-C, de Zwart M, Chang L, Moro S, von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel JK, Melman N, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA. 1998. Derivatives of the triazoloquinazoline adenosine antagonist (CGS15943) having high potency at the human A2B and A3 receptor subtypes. J Med Chem 41:2835–2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden J 1982. Calculating the dissociation constant of an unlabeled compound from the concentration required to displace radiolabel binding by 50%. J Cycl Nucl Res 8:163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden J 1998. Molecular characterization of A2A and A2B receptors. Drug Devel Res 43:2. [Google Scholar]

- Linden J, Jacobson KA. 1998. Molecular biology of recombinant adenosine receptors. In: Burnstock G, Dobson JG, Liang BT, Linden J, editors. Cardiovascular biology of purines. Norwell, MA: Kluwer. p 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lunell E, Svedmyr N, Andersson KE, Persson CG. 1982. Effects of enprofylline, a xanthine lacking adenosine receptor antagonism, in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 22:395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt DM. 1963. An algorithm for least-squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. J Soc Indust Appl Math 11:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Martin PL, Ueeda M, Olsson RA. 1993. 2-Phenylethoxy-9-methylade-nine: an adenosine receptor antagonist that discriminates between A2 adenosine receptors in the aorta and the coronary vessels from the guinea pig. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 265:248–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary J, Rathbone MP, Cattabeni F, Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G. 1996. Trophic actions of extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides on glial and neuronal cells. Trends Neurosci 19:13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer TM, Poucher SM, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. 1996. 125I-4-(2-[7-Amino-2 {furyl}{1,2,4}triazolo{2,3-a}{1,3,5}triazin-5-ylaminoethyl)-phenol (125I-ZM241385), a high affinity antagonist radioligand selective for the A2a adenosine receptor. Mol Pharmacol 48:970–974. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramkumar V, Stiles GL, Beaven MA, Ali H. 1993. The A3 adenosine receptor is the unique adenosine receptor which facilitates release of allergic mediators in mast cells. J Biol Chem 268: 16887–16890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MB, Colgan SP, Patapoff TW, Mrsny RJ, Awtrey CS, Delp-Archer C, Weller PF, Madara JL. 1993. Activated eosinophils evoke chloride secretion in model intestinal epithelia primarily via regulated release of 5′-AMP. J Immunol 151:5716–5723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robeva A, Woodard R, Luthin DR, Taylor HE, Linden J. 1996a. Double tagging recombinant A1- and A2A-adenosine receptors with hexahistidine and the FLAG epitope — development of an effi cient generic protein purification procedure. Biochem Pharmacol 51:545–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robeva AS, Woodard R, Jin X, Gao Z, Bhattacharya S, Taylor HE, Rosin DL, Linden J. 1996b. Molecular characterization of recombinant human adenosine receptors. Drug Dev Res 39:243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore CA, Jacobson MA, Taylor HE, Linden J, Johnson RG. 1993. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human A3 adenosine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:10365–10369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe U, Trost T. 1980. Characterization of adenosine receptors in rat brain by (−) [3H]N6-phenylisopropyladenosine. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 313:179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamim MT, Ukena D, Padgett W, Daly JW. 1989. Effects of 8-phenyl and 8-cycloalkyl substitutents on the activity of mono-, di-, and trisubstituted alkylxanthines with substitution at the 1-, 3-, and 7-positions. J Med Chem 32:1231–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd RK, Linden J, Duling BR. 1996. Adenosine-induced vasoconstriction in vivo — role of the mast cell and A(3) adenosine receptor. Circ Res 78:627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehle JH, Rivkees SA, Lee JJ, Weaver DR, Deeds JD, Reppert SM. 1992. Molecular cloning and expression of the cDNA for a novel A2-adenosine receptor subtype. Mol Endocrinol 6:384–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell CP, Kuhlenschmidt TG, Hoppe CA. 1978. A fluorescamine assay for submicrogram quantities of protein in the presence of Triton X-100. Anal Biochem 85:572–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohmeier GR, Reppert SM, Lencer WI, Madara JL. 1995. The A2b adenosine receptor mediates cAMP responses to adenosine receptor agonists in human intestinal epithelia. J Biol Chem 270:2387–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wenden EM, Hartog-Witte HR, Roelen HCPF, von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel JK, Pirovano IM, Mathôt RAA, Danhof M, van Aerschot A, Lidaks MJ, IJzerman AP, Soudijn W. 1995. 8-Substituted adenosine and theophylline-7-riboside analogs as potential partial agonists for the adenosine A1 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol Mol Pharmacol Sect 290:189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]