Abstract

Despite the known benefits of supportive work environments for promoting patient quality and safety and healthcare worker retention, there is no clear mandate for improving work environments within Learning Health Systems (LHS) nor an LHS wellness competency. Striking rises in burnout levels among healthcare workers provide urgency for this topic.

Methods

We brought three experts on moral injury, burnout prevention, and ethics to a recurring, interactive LHS training program “Design Shop” session, harnessing scholars’ ideas prior to the meeting. Generally following SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines, we evaluated the prework and discussion via informal content analysis to develop a set of pathways for developing moral injury and burnout prevention programs. Along these lines, we developed a new competency for moral injury and burnout prevention within LHS training programs.

Results

In preparation for the session, scholars differentiated moral injury from burnout, highlighted the profound impact of COVID‐19 on moral injury, and proposed testable interventions to reduce injury. Scholar and expert input was then merged into developing the new competency in moral injury and burnout prevention. In particular, the competency focuses on preparing scholars to (1) demonstrate knowledge of moral injury and burnout, (2) measure burnout, moral injury, and their remediable predictors, (3) use methods for improving burnout, (4) structure training programs with supportive work environments, and (5) embed burnout and moral injury prevention into LHS structures.

Conclusions

Burnout and moral injury prevention have been largely omitted in LHS training. A competency related to burnout and moral injury reduction can potentially bring sustainable work lives for scholars and their colleagues, better incorporation of their science into clinical practice, and better outcomes for patients.

Keywords: burnout, ethical climate, LHS (learning health system), moral injury

1. INTRODUCTION

Learning Health Systems (LHS) have well‐established competencies 1 for supporting embedded research and encouraging prompt system change based on local findings. LHS researcher core competencies focus upon seven domains: (1) systems science; (2) scientific evidence standards; (3) research methods; (4) informatics; (5) health system research ethics; (6) implementation science; and (7) engagement, leadership, and research management. The Minnesota Learning Health System (MN‐LHS) Center of Excellence within the AHRQ‐PCORI LHS K12 program selects two to three scholars per year to train within the program; scholars are Ph.D. or physician scientists typically 3–5 years into postgraduate careers pursuing LHS science while embedded within their institutions. As a core aspect of training, we established an interactive curriculum format, or “Design Shop,” using a Mayo Clinic model with peer mentoring and new science born via collaborations amongst attendees. Biweekly (every other week) 60–90 min sessions cover topics from LHS competencies and encourage new knowledge creation. Here we report on how a Design Shop session sparked a new focus on burnout and moral injury prevention, with a related LHS competency.

Ethical dilemmas in the workplace may result in “moral injury,” are a source of burnout and distress, 2 , 3 and present barriers to ethical work climates. 4 To address this gap in LHS competencies, we used a self‐study format before a Design Shop to enhance the discussion of “Moral Injury and an Ethical Work Climate.” We now offer a call for an LHS competency in moral injury, burnout prevention, and the creation of an ethical climate for healthcare workers (HCWs) throughout LHS and other institutions.

2. QUESTIONS WE SEEK TO ANSWER WITH THIS PAPER ARE

(1) What are the underlying tenets of burnout and moral injury prevention, (2) how can burnout and moral injury prevention support an ethical work climate in LHS science, and (3) what is the potential “value added” for a new competency in moral injury and burnout reduction?

3. DEFINITIONS, BACKGROUND, AND RELATING WORK LIFE TO LHS CORE VALUES

Burnout and moral injury are overlapping but distinct constructs. 5 , 6 Burnout is emotional exhaustion and depersonalization from work stress, 7 while moral injury is the result of being forced to do something that one believes is ethically unacceptable. 3 , 6 Burnout and stress are in part based upon the demand‐control model of job stress, with stress (and burnout, a long‐term stress reaction) rising in response to work demands or diminishing work control. 8 The MEMO (Minimizing Error Maximizing Outcome) study supported by AHRQ in 2005–2009 7 in 119 primary care practices showed that almost half of the clinicians needed more time for visits, 27% were burning out (this number has risen 2 to 50%), and 30% intended to leave their jobs. Strong relationships linked work environments (control, chaos, time pressure, and culture) to adverse outcomes (stress, burnout, and intent to leave). Patient care quality was lower with adverse work conditions, while quality was higher when culture (such as values congruence with leaders) was favorable. 7 The AHRQ‐funded Healthy Work Place (HWP) randomized trial found three types of workplace interventions favorably affected burnout and/or satisfaction: workflow redesign, communication improvements between provider groups, and quality improvement initiatives sharing work with team members. 9 Thus, there is strong evidence that workplace stress relates to adverse outcomes for clinicians and patients, and evidence‐based interventions can reduce burnout.

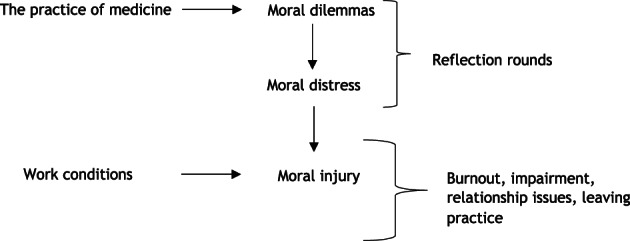

In 2019, Dean and colleagues laid the groundwork for discussing moral distress in medicine. 10 Moral distress, a predecessor of moral injury, occurs when policies or routines conflict with personal beliefs, for example, when clinicians must do things with which they fundamentally disagree. 3 , 6 , 10 LHS scholars might experience moral distress from work overload and system inefficiencies interfering with self‐care and scholarly work; clinicians experience distress when they must give nonbeneficial care to a dying patient. Our conceptual model 11 shows how moral dilemmas can lead to moral distress (Figure 1), which can lead to moral injury. 12 Work conditions contribute to these outcomes, while reflection rounds, a powerful tool for debriefing challenging events, can interrupt injurious processes. Epstein's crescendo effect shows how repeated injury episodes lead to lasting impairment. 13 Compromising one's integrity, a proxy for moral injury, is also linked to adverse outcomes, including burnout and intent to leave the institution, 5 especially in critical care clinicians and nurses. 5 Feeling valued by one's organization attenuated adverse outcomes. A brief moral injury metric for clinical use is in development (LeClaire, manuscript in preparation).

FIGURE 1.

Moral dilemmas leading to moral distress and then moral injury. Based upon work first published in Linzer M, Poplau S. Eliminating burnout and moral injury: Bolder steps required. EClinicalMedicine. 2021 Aug 19;39:101090. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101090. PMID: 34466795; PMCID: PMC8385149.) Reprinted with permission.

The creation of an ethical work climate is an anticipated outcome of reductions in moral injury and burnout. 3 , 10 , 11 This can be important for trainees (eg, not putting ethically meaningful work aside), as well as for clinicians (always acting on behalf of the patient). A virtues‐based approach reduces moral injury by balancing classic ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. 4 , 14 Ethicists propose recalibrating the balance between autonomy and beneficence, allowing actions “directed by the good of the patient”. 15 To link moral injury reduction to more ethical work climates, Savel and Munro 4 introduce the “four A” framework of Ask (is my team suffering?), Affirm (allow for self‐care), Assess (identify sources of distress) and Act (preserve integrity and authenticity). These questions can identify sources of distress and lead to reduced injury; further studies should test these assertions in clinical environments.

These ethical processes relate to LHS Core Values (www.Learninghealth.org). An LHS aspires to improve the health of individuals and populations, generating and sharing knowledge to allow clinicians to apply best practices and make better decisions. Preventing burnout and moral injury is essential to this process, 16 as the ability to sustain as an HCW and make good decisions depend upon the health of the HCW. Burnout and moral injury prevention support LHS frameworks and core values as they:

Nurture individual healthcare providers (person‐focused)

Provide for a diverse workforce with diverse patients (inclusive)

Allow HCWs to respond to urgent needs (adaptability)

Provide substance for trust building (governance‐oriented)

Allow leaders to rise to the top of their capabilities (participatory leadership)

Allow capacity for incorporating rigorous new knowledge (scientific integrity), and

Support HCWs in optimizing quality and moderating costs (value).

Given the benefits of preventing burnout and moral injury, both for health systems and for embedded scholars, we pursued “next steps” via an interactive learning session focused on creating a sustainable and ethical work climate within an LHS, with the result being a call for a new competency in moral injury and burnout reduction.

4. EDUCATIONAL SESSION TO INCORPORATE THOUGHTS OF LHS SCHOLARS

To bring LHS scholars into the process, we planned a session on burnout and moral injury prevention. Four weeks before the session, we distributed two brief articles 3 , 11 and asked scholars to respond to two questions:

How does moral injury differ from burnout as a way of describing work distress?

How might you organize an LHS project to reduce moral injury?

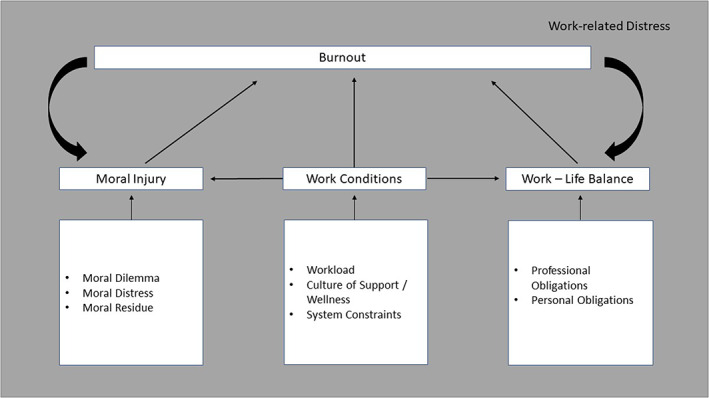

Replies to the prework were collated, reviewed, and used to prompt discussion during the Design Shop. An informal review of themes from LHS scholars’ comments was later performed by one author (M.L.). The LHS scholars (12 surveyed, 4 (33%) responded (2 females, 2 males, 1 MD, 3 Ph.Ds)) provided written comments that were viewed within the lens of SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines for Quality Improvement reporting, with comments addressing HCW burnout, providing the rationale for existing LHS constructs, elaborating on methods to develop these models, and offering a summary of ways forward to address burnout and moral injury reduction. One model by co‐author and LHS scholar W.M. (Figure 2) presented actionable emphases on work conditions and work‐life balance. Among themes identified, LHS scholars included contrasts of burnout versus moral injury, promising methodologies (such as Ecological Momentary Assessment, known for real‐time assessment of physiologic and psychologic variables, 17 , 18 and using a Moral Injury Symptom Scale 19 to study resident burnout), interventions (including self‐care training and revisions in workflows), and acknowledging unique impacts of COVID‐19. New framing of moral injury etiologies included insufficient time with patients, COVID‐related care rationing, inadequate attention to invisible (noncountable) work, and mismatches between scholars’ values and mandates in how they were to practice medicine or perform scholarship (see Table 1). Ecologic Momentary Assessment, in particular, has been used extensively to study wellbeing, capturing the fluid nature of daily emotions. Across studies, ~72% of assessments were completed by participants, with the best engagement in assessment periods of 1–2 weeks. 20

FIGURE 2.

Model linking work conditions, work‐life balance, moral injury, and burnout. Conceptual model by author W.M. linking work conditions, work‐life balance, moral injury, and burnout, demonstrating proposed relationships between these variables and points for interventions to improve the work environment within Learning Health Systems.

TABLE 1.

Recommendations from LHS Scholars pre‐work and attendees at Minnesota LHS Design Shop session 5‐5‐2022 on “Reducing burnout and moral injury.”

| Recommendations |

|---|

| Focus on actionable aspects of moral injury, work conditions, and work‐life balance to reduce burnout |

| Contrast burnout versus moral injury |

| Use targeted methods to pursue learning about burnout and moral injury, including |

|

|

|

| Test interventions (self‐care training, workflow redesign) in using QI methods |

| Develop methods to address unique aspects of workflow surges (due, for example, to COVID‐19) |

| Catalog and study current morally injurious situations, such as |

|

|

|

|

|

| Relate moral injury prevention to high‐impact topics such as |

|

|

During the Design Shop “virtual session” on 5‐5‐22, with approximately 30 regional participants (4 national and regional experts on moral injury and ethics (two were physicians), nine LHS scholars/trainees (four physicians), nine Minnesota LHS program leaders (two physicians), six colleagues from University of Minnesota's Center for LHS Sciences, two PhD students, two PhD visiting scholars, and one VA fellow), leading‐edge scientific issues arose, including an Asset versus Deficit based approach (assessed via Appreciative Inquiry 21 , 22 as a means to learn about successes in creating supportive work climates), the relationship of moral injury to equity (with new instruments to assess negative experiences due to race and gender, 23 ), how professionalism challenges lead to injury, and the need for systems change to promote fairness, inclusion, and sustainability (Table 1). We note that appreciative inquiry has been used to create interventions to reduce burnout in nurses. 24

5. A COMPETENCY IN BURNOUT AND MORAL INJURY PREVENTION

Based on these discussions, we have confidence that burnout and moral injury prevention will be relevant locally and nationally. 25 Burnout and moral injury prevention represent an important educational domain to LHS scholars (Question 1), which can serve to protect LHS scholars and institutional colleagues from burnout and moral injury (Question 2) while providing “value added” by encouraging scholars to include this topic in studies that benefit their institutions (Question 3). In a study in medical faculty in Iran, 26 burnout related to lower interest in incorporating new curricula; thus, burnout reduction holds promise for facilitating the incorporation of new ideas generated in an LHS. While there is some overlap with health systems research ethics, the science of burnout and moral injury has largely been relegated to an “other” category, even while burnout has skyrocketed. 25 The absence of a specific competency has been accompanied by a lack of focus in this aspect of LHS science that has consequently not kept pace with the rising burnout rates. We thus describe and issue a call for a new Competency Domain for LHS programs in burnout and moral injury prevention:

To ensure clinician and researcher wellness (in this case, prevention of burnout and moral injury) is promoted in clinical practice and academic endeavors.

Competencies:

Demonstrate ability to assess burnout and moral injury in an organization using standard metrics while identifying remediable predictors of these outcomes.

Demonstrate knowledge of components of burnout and moral injury and how to address work climates to become more ethical 27 by using a Four A approach (Ask, Affirm, Assess, Act).

Demonstrate knowledge of promising new methods, including Ecologic Momentary Assessment and appreciative inquiry, while explicitly addressing equity as a component of burnout.

Demonstrate ability to structure an LHS training program with a focus on burnout and moral injury prevention leading to enhanced retention.

Demonstrate means of embedding burnout/moral injury prevention into an LHS to benefit researchers, HCWs, and patients.

This conceptualization of a burnout/moral injury prevention competency is limited by the development in one setting with a small number of LHS scholars (nine), experts (four) and discussants (approximately thirty). Thus, this work should be viewed as exploratory. We welcome a conversation on burnout and moral injury prevention as we articulate ways for health systems to create better work environments 28 for their workers, scholars, and patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Linzer is supported through his employer Hennepin Healthcare for burnout reduction studies and training by large health systems (Optum, Essentia, Gillette, California AHEC) and by national organizations (AMA and IHI). His work on this paper was supported by AHRQ. The other authors have no disclosures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Drs. Felicity Enders and Tim Beebe for leadership in the MN‐LHS program and for their contributions to the program content summarized in this manuscript, as well as to the Design Shop construct. We are also very grateful to Mona Rath BA for her support of this project.

Yilmaz S, LeClaire M, Begnaud A, et al. Developing LHS scholars’ competency around reducing burnout and moral injury. Learn Health Sys. 2024;8(1):e10378. doi: 10.1002/lrh2.10378

REFERENCES

- 1. Forrest C, Chesley F, Tregear ML, Mistry KB. Development of LHS researcher core competencies. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(4):2615‐2632. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Prasad K, McLoughlin C, Stillman M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among US healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100879. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dean W, Talbot SG, Caplan A. Clarifying the language of clinician distress. JAMA. 2020;323(10):923‐924. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Savel RH, Munro CL. Moral distress, moral courage. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(4):276‐278. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. LeClaire M, Poplau S, Linzer M, Brown R, Sinsky C. Compromised integrity, burnout and intent to leave the job in critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Explor. 2022;4(2):e0629. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosen A, Cahill JM, Dugdale LS. Moral injury in health care: identification and repair in the COVID‐19 era. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(14):3739‐3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Linzer M, Manwell LB, Williams ES, et al. Working conditions in primary care: physician reactions and care quality. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(1):28‐36, W6‐9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karasek R, Baker D, Marxer F, Albohm A, Theorell T. Job decision latitude, job demands, and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of Swedish men. Am J Pub Health. 1981;71:694‐705. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.7.694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, et al. A cluster randomized trial to improve work conditions and burnout in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1105‐1111. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3235-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400‐402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Linzer M, Poplau S. Eliminating burnout and moral injury: bolder steps required. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101090. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hamric AB, Borchers CT, Epstein EG. Development and testing of an instrument to measure moral distress in healthcare professionals. AJOB Primary Res. 2012;3(2):1‐9. doi: 10.1080/21507716.2011.652337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Epstein EG, Delgado S. Understanding and addressing moral distress. Online J Issues Nurs. 2010;15(3):Manuscript 1. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No03Man01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jameton A. What moral distress in nursing history could suggest about the future of health care. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(6):617‐628. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.6.mhst1-1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pellegrino ED, Thomasma DC. The Virtues of Medical Practice. NY, NY: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Linzer M, Sullivan EE, Olson APJ, Khazen M, Mirica M, Schiff GD. Improving diagnosis: adding context to cognition. Diagnosis (Berl). 2022;10:4‐8. doi: 10.1515/dx-2022-0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dao KP, De Cocker K, Tong HL, Kocaballi AB, Chow C, Laranjo L. Smartphone‐delivered ecological momentary interventions based on ecological momentary assessments to promote health behaviors. JMIR. 2021;9(11):e22890. doi: 10.2196/22890 PMID: 34806995; PMCID: PMC8663593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown AC, Dhingra K, Brown TD, Danquah AN, Taylor PJ. A systematic review of the relationship between momentary emotional states and non‐suicidal self‐injurious thoughts and behaviours. Psychol Psychother. 2022;95(3):754‐780. doi: 10.1111/papt.12397 PMID: 35526112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mantri S, Lawson JM, Wang Z, Koenig HG. Identifying moral injury in healthcare professionals: the moral injury symptom scale‐HP. J Relig Health. 2020;59(5):2323‐2340. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01065-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Vries LP, Baselmans BML, Bartels M. Smartphone‐based ecological momentary assessment of well‐being: a systematic review and recommendations for future studies. J Happiness Stud. 2021;22(5):2361‐2408. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00324-7 Epub 2020 Oct 23. PMID: 34720691; PMCID: PMC8550316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arnold R, Gordon C, van Teijlingen E, Way S, Mahato P. Why use appreciative inquiry? Lessons learned during COVID‐19 in a UK maternity service. Eur J Midwifery. 2022;19(6):28‐27. doi: 10.18332/ejm/147444. PMID: 35633754; PMCID: PMC9118624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Butcher I, Morrison R, Webb S, Duncan H, Balogun O, Shaw R. Understanding what wellbeing means to medical and nursing staff working in paediatric intensive care: an exploratory qualitative study using appreciative inquiry. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e056742. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056742 PMID: 35365529; PMCID: PMC8977799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Audi C, Poplau S, Freese R, Heegaard W, Linzer M, Goelz E. Negative experiences due to gender and/or race: a component of burnout in women providers within a safety‐net hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(3):840‐842. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06144-y Epub 2020 Oct 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guo YF, Wang XX, Yue FY, Sun FY, Ding M, Jia YN. Development of a nurse‐manager dualistic intervention program to alleviate burnout among nurses based on the appreciative inquiry. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1056738. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1056738 PMID: 36562061; PMCID: PMC9763613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Linzer M, Jin J, Shah P, et al. Trends in clinician burnout with associated mitigating and aggravating factors during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(11):e224163. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.4163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arvandi Z, Emami A, Zarghi N, Mohammad Alavinia S, Shirazi M, Parikh SV. Linking medical faculty stress/burnout to willingness to implement medical school curriculum change: a preliminary investigation. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016;22(1):86‐92. doi: 10.1111/jep.12439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parsa‐Parsi RW. The international code of medical ethics of the world medical association. JAMA. 2022;328(20):2018‐2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Giardina TD, Shahid U, Mushtaq U, UpandHyay DK, Marinez A, Singh H. Creating a learning health system for improving diagnostic safety: pragmatic insights from US health care organizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(15):3965‐3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]