Abstract

Significant debate persists about the obligations of nonprofit hospitals toward low-income patients. Many issues pertaining to this subject were discussed during the rulemaking process following the passage of the Affordable Care Act of 2010, which set forth rules for hospital billing and collection. In public comments, hospitals, debt collectors, and patient advocates debated what constituted “reasonable efforts” to determine whether a patient qualified for hospital financial assistance before resorting to extraordinary collection actions including lawsuits, wage garnishments, and adverse credit reporting. This study analyzes public comments to the proposed Internal Revenue Service rule on section 501(r)(6). After an initial review of the data, 5 commonly mentioned issues were identified. Respondents were organized into commenter types, and the opinion of each respondent to each issue was coded by 2 separate reviewers. Discrepancies between reviewer determinations were resolved by consensus during follow-up discussions. This analysis revealed a set of common concerns: whether reporting delinquent medical debt to credit bureaus and selling debt to third party buyers should be considered extraordinary collection actions; whether hospitals should be able to use presumptive eligibility to rule patients either eligible or ineligible for financial assistance; and whether hospitals should be held legally liable for the actions of third-party debt collectors. Hospitals and debt collection agencies were allied on most issues, particularly in their shared belief that reporting debt to credit bureaus and selling debt to third parties should not be tightly regulated. Patient advocacy organizations and hospitals had divergent opinions on most issues. The alliance of hospitals and debt collectors in advocating for fewer regulations around collections is part of a history of hospital lobbying to maintain tax-exemption with fewer charity care mandates. This alignment helps explain why third-party debt collection agencies, and aggressive collection tactics, have become commonplace in hospital billing.

Keywords: medical debt collection, hospital financing, charity care, community benefit, extraordinary collection action, Internal Revenue Service

What do we already know about this topic?

Federal law allows tax-exempt nonprofit hospitals in the United States to engage in extraordinary collection actions against patients with unpaid debts; these actions include wage garnishment, credit reporting, and the sale of debt to third parties.

How does your research contribute to the field?

Our research demonstrates that hospitals joined with debt collection agencies in arguing against regulations intended to protect low-income patients who qualified for financial assistance from extraordinary collection actions.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

The Internal Revenue Service has the ability to protect low-income patients from aggressive medical debt collection practices, but this power has been restrained by regulatory capture.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the aggressive collection tactics of nonprofit hospitals against low-income patients who are not able to pay their medical debts. Journalists and health policy investigators have documented the widespread use of adverse credit reporting, lawsuits, wage garnishment, property liens, foreclosures, and the denial of care. 1 These tactics, known as “extraordinary collection actions,” threaten a huge swath of the American public, as a recent estimate placed number of Americans who carry medical debt at 100 million. 1

In response to criticism, hospitals have defended themselves by referencing their “community benefits,” including their financial assistance policies (FAPs), which detail eligibility criteria for free or discounted care for low-income patients. 2 Yet although these policies are required by law of all tax-exempt hospitals, federal regulations set no minimum amount of spending on financial assistance nor minimum income criteria for patient eligibility. Low-income patients, including patients who qualify for hospital financial assistance, continue to be sent bills and subjected to collection actions. In 2018, 38% of households with children and with an annual income below $40 000 had at least one medical bill in collections on their credit reports. 3 The following year, in annual reports to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), 45% of private nonprofit hospitals admitted that they routinely sent medical bills to patients whose incomes were low enough to qualify for charity care. 4

Hospital billing departments already use presumptive eligibility software that can determine, within minutes and without any paperwork from patients, whether they are likely to qualify for free or reduced-cost care under the hospital’s own financial assistance policy. These hospitals use information such as the patient’s zip code, enrollment in public assistance programs such as food stamps, a soft pull on a credit report, and proprietary machine learning algorithms licensed by private companies to determine whether the patient’s income is likely to be low enough to qualify for free or reduced-cost care according to a hospital’s own financial assistance program. Software for these presumptive eligibility determinations are sold by a number of private companies, and can be tailored to the specifications of individual health systems. 5 Despite the widespread availability of such software, hospitals are not required by federal law to attempt to determine presumptive eligibility at the point of care. This article seeks to explain how hospitals have been able to continue pursuing low-income patients for their debts without imperiling their tax-exempt status, in part due to their advocacy in defining important terms in federal regulations.

Many of the federal rules governing the financial assistance policies and the billing and collection practices of tax-exempt nonprofit hospitals are laid out in a section of the IRS tax code known as 501(r)(6). This section of the code was a provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010. The text of that law stated that a tax-exempt hospital could not “engage in extraordinary collection actions before the organization has made reasonable efforts to determine whether the individual is eligible for assistance under the financial assistance policy.” However, the law left it to the Secretary of the Treasury to define “what constitutes reasonable efforts to determine the eligibility of a patient under a financial assistance policy.” 6

A 2010 report by the Joint Committee on Taxation stated that “‘reasonable efforts’ includes notification by the hospital of its financial assistance policy upon admission and in written and oral communications with the patient regarding the patient’s bill. . .before collection action or reporting to credit rating agencies is initiated.” 7 But it remained to the Treasury to fully define “reasonable efforts.” The IRS, a bureau of the Treasury, released proposed rules in June 2012 and requested public comments by September of that year. 8 Any person or organization can submit a comment, and when agencies publish final regulations, they must discuss significant issues presented in comments as well as changes made in response to them. 9 The purpose of this study was to understand which groups or institutions submitted public comments on 501(r)(6) regulations and the positions they took. We sought to examine what kinds of tactics they thought should constitute “extraordinary collection actions” (ECAs), and what they believed hospital billing departments had to do to fulfill their “reasonable efforts” to determine whether a patient was eligible for financial assistance before they could take such actions.

Understanding the power of lobbying to shape hospital charity care obligations requires some knowledge of its history. In its first ruling on charity care in 1956, the IRS decided that in exchange for tax exemption, a nonprofit hospital had to provide charity care “to the extent of its financial ability for those not able to pay for service rendered.”10,11 After the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, hospitals pushed for a new standard of tax exemption. One of their main contentions was that with the rise of private insurance and the enactment of government insurance for the poor and the elderly, there was no longer much need for hospital-funded charity care. 12

In response Robert Bromberg, a staff attorney at the IRS, worked to develop a new standard. Released in 1969 without public comment, this new rule replaced the “charity care standard” with what became known as a “community benefit standard.” This rule asserted that even if the indigent were excluded from care, hospitals could justify their charitable purpose through other contributions to the health of the community. Bromberg echoed hospital executives’ claims when he argued that the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid and the spread of private health insurance “diminished the amount of free care needed.” 13 Bromberg’s rule allowed hospitals to demonstrate fitness for tax exemption by having a community board and by treating Medicare and Medicaid patients. A subsequent ruling did require tax-exempt hospitals to do more than simply treat paying patients; spending surplus funds on medical research, teaching, and new patient care facilities could also demonstrate community benefit. 14 Thus, following the 1969 ruling, care of the poor was no longer the main criterion by which tax exemption would be determined. Because the IRS has long been the arbiter of sweeping changes in nonprofit hospitals’ responsibility to provide financial assistance to low-income patients, the history of medical debt in the United States inevitably runs through the offices of little-known tax officials.

Methods

A total of 224 comments were submitted to the US Federal Register in response to the proposed rule in 2012. Each of the comments was downloaded onto a Google Drive. These comments were examined, and duplicate comments were removed, as were comments that did not express any opinions or make any recommendations. The remaining comments were grouped into 1 of 8 commenter types: patient advocacy group; debt collector or debt buyer; hospital or hospital association; professional association or union; legal or consultancy firm for hospitals; predictive eligibility company; private individual; or public official. Institutional Review Board approval was not required, as the US Federal Register is a publicly available database whose submitters are notified before comments are uploaded that they will be placed on a publicly accessible website.

The public comments were analyzed by means of a modified thematic content analysis, a method that allows researchers to examine and record patterns based on themes that emerge from qualitative data. The codebook was developed through an inductive process that has been used in analyzing public comments in other areas of federal regulation.9,15 The principal investigator (LM) first developed familiarity with the data by examining a sample of 20 of the comments and searching for common themes pertaining to the 501(r)(6) regulations. Five issues were mentioned frequently. The first 2 pertain to whether a credit reporting and selling debt to third parties should be included in the definition of ECAs. The third issue involved whether presumptive eligibility software should be used to determine whether patients were eligible for financial assistance, without the standard application process. The fourth issue also pertained to presumptive eligibility, and involved whether software could also be used to determine whether patients were ineligible for free care (either because they qualified only for discounted care or because they did not qualify for financial assistance at all). The final issue involved whether hospitals should be held liable for violations by third party debt collectors to which they had sold or assigned their debts.

After review of these issues with the entire team, these 5 issues were included in the codebook, which was then applied to all comments. If the commenter stated an opinion on one of these issues, they were listed as “for” or “against” the measure. If they stated no opinion, they were coded as “no opinion stated.” No additional themes were added after the initial review by the PI.

Two coding pairs were formed, and the coders were trained by the principal investigator (PI) regarding the codebook and coding procedures. The first coding pair independently coded 78 comments, while the second pair independently coded the remaining 78 comments. Coding discrepancies were discussed and were resolved by consensus within each coding pair. These reports were used to determine code frequencies for each comment. Responses that were typical of a given interest group for a given issue were excerpted.

Results

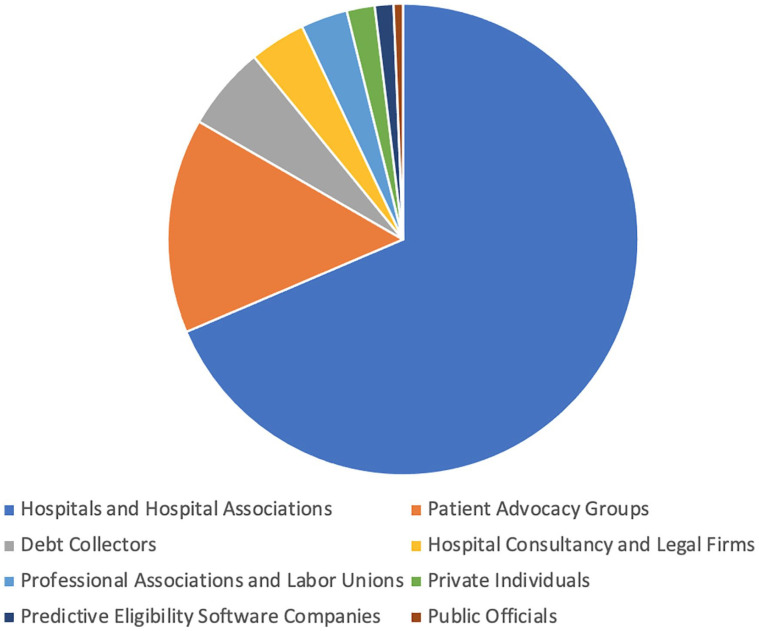

After the removal of 68 duplicates and comments that did not express opinions, there were 156 qualifying comments for analysis. Figure 1 displays the share of commenters by type. The majority of comments came from hospitals or hospital associations (110/156; 70.5%); among these were state and national hospital associations and large nonprofit hospitals and hospital systems. Patient advocacy organizations, which include legal aid organizations as well as consumer advocates, submitted 14.1% (22/156) of public comments, followed by debt collection and debt buying firms (9/156; 5.8%); consultancy and legal firms working for hospitals (5/156; 3.2%); professional associations and labor unions (4/156; 2.6%); private individuals (3/156; 1.9%); companies selling predictive eligibility software (2/156; 1.3%); and public officials (1/156; 0.6%).

Figure 1.

Distribution of commenter type.

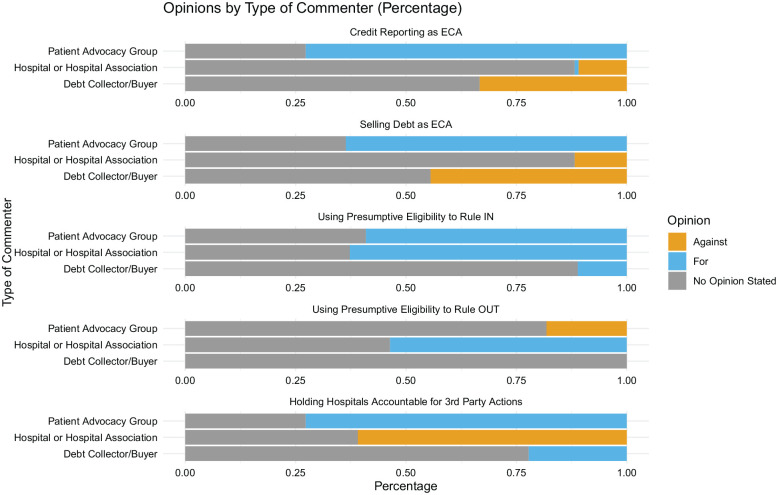

Figure 2 displays the responses to major issues pertaining to 501(r)(6) regulations among the 3 most common types of commenters (hospitals, patient advocacy groups, and debt collectors). The first of the 5 issues pertaining to 501(r)(6) regulations related to whether credit reporting should be considered an ECA, and thereby subject to certain limitations. In the IRS rule, ECAs could only be taken after the hospital had taken what IRS deemed to be “reasonable efforts” to determine if the patient qualified for financial assistance. The regulations required the hospital to wait at least 120 days after issuing the first billing statement to take such action, and before doing so the hospital had to provide written notice informing the patient about the hospital’s financial assistance policies.

Figure 2.

Opinions by type of commenter.

Among hospitals and hospital associations, 11.8% (13/110) rendered an opinion on whether reporting hospital debt to credit agencies should not be considered an ECA subject to the regulations stipulated by the IRS. Of these, almost all (12/13; 92.3%) were against it. Only one hospital explicitly stated that it would prefer to wait the proposed 120 days after the first billing statement to report delinquent patient-debtors to credit bureaus. 33.3% (3/9) of debt collectors and debt buyers expressed an opinion on this issue. Of these, 100% were against making adverse credit reporting an ECA. Among patient advocacy groups, 72.7% (16/22) rendered an opinion on this issue, and among these, 100% argued that reporting delinquent debt to credit bureaus should be an ECA.

The second argument related to whether the sale of debt should be considered an ECA. Among hospitals, 11.8% (13/110) stated an opinion on this issue; of these, all argued that the sale of debt should not be considered an ECA. Their opinions were aligned with those of debt collection and debt buying firms; of the 4 firms (4/9; 44.4%) that stated an opinion, 100% stated that selling debt should not be an ECA. The opinion of patient advocacy groups was, again, diametrically opposed to that of hospitals and debt collectors. Among the 63.6% (14/22) of patient advocacy groups that stated an opinion on this issue, all argued that the sale of debt should be considered an ECA.

Hospitals argued that credit reporting and selling debt should not be considered ECAs because these actions were normal tools of consumer debt collection. As the California Children’s Hospital Association explained in its public comment, “These are widely and commonly used debt collection practices in most industries.” 16 The Association of American Medical Colleges echoed this claim, stating, “It is not unusual for individuals who do not pay their bill to be reported to credit bureaus; hospitals should not be held to a different standard.” 17 Medical debt was, in these formulations, not to be treated any differently than other kinds of consumer debt.

For their part, patient advocacy organizations argued that medical debt was different from other kinds of consumer debt, and therefore should be regulated differently. In its public comment, Families USA stated: “Medical debt is not like other forms of debt: patients incur the debt involuntarily when they are sick or injured and do not have the means to pay for care.” 18 They lamented the harms done to patients when credit reports were adversely affected, or when they were aggressively pursued by debt buyers. Some consumer advocacy groups argued the sale of patient debt to third-party buyers should be outlawed entirely.

The third point was about whether presumptive eligibility software should be used to rule patients eligible for hospital financial assistance. In its notice, the IRS had stated that presumptive eligibility could be used to rule a patient eligible “for the most generous assistance (including free care) available under the FAP,” but the hospital would have to solicit applications for any patients not already found to be eligible for the highest level of aid. 8

Among the hospitals who filed public comments, 62.7% (69/110) stated an opinion on the use of presumptive eligibility to rule patients eligible for financial assistance. None of them claimed hospitals should be required to investigate for presumptive eligibility, but all hospitals that stated an opinion were in favor of allowing its use to determine eligibility for assistance.

The fourth point—related to the third—was about whether presumptive eligibility software could be used to rule that patients were ineligible for financial assistance, thereby eliminating the requirement to allow time for patients to submit financial assistance applications. The IRS’ concern was that the algorithms underlying presumptive eligibility software might not be entirely accurate and might deem some patients ineligible for financial assistance when they actually qualified. 19

Among hospitals, 53.6% (59/110) stated an opinion on this issue, and all were in favor of allowing presumptive eligibility to rule that patients were ineligible for financial assistance. A smaller proportion of patient advocacy groups stated an opinion, but of the 18.2% (4/22) who did, all were opposed. Many hospitals argued that they should be able to use the presumptive eligibility to determine whether patients were eligible for only discounted care (and not free care) or ineligible for financial assistance altogether. They argued that these kinds of determinations would allow hospitals to proceed to billing the patients and then to an ECA without the months-long notification period. The Cleveland Clinic argued that the rule, as written, “effectively requires hospitals to initially treat every person as eligible for assistance, and, therefore, comply with the extensive and detailed record-keeping requirements. . .This is likely the most costly aspect of the reasonable efforts requirements.” 20

The final issue involved whether hospitals should be held accountable for the actions of third-party debt collectors and debt buyers. Hospitals worried about being liable for the actions of debt collectors if they pursued ECAs without meeting the criteria for “reasonable efforts” to determine eligibility for financial assistance. Of the 60.9% (67/110) that stated an opinion, all were opposed to such liability. Many of them stated that hospitals should be held responsible for the actions of third parties only if hospital staff knew of a material violation and failed to take remedial steps.

On this issue, too, patient advocacy organizations disagreed with hospitals. Of the 72.7% (16/22) of patient advocacy groups that stated an opinion, all were in favor of holding hospitals liable for the actions of third parties. As the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative argued, “Only if hospitals remain financially or otherwise responsible will there be sufficient deterrence of inappropriate behavior by third parties.” 21

Discussion

This analysis demonstrates that hospitals were often allied with debt collectors and against patient advocacy organizations in their policy positions on medical debt collection. Hospitals and debt collectors were nearly unanimous in arguing that debt sales and adverse credit reporting should not constitute ECAs. On the other side, patient advocacy organizations argued unanimously that these should constitute ECAs. Patient advocacy organizations and hospitals shared the opinion that presumptive eligibility software could be used to rule patients eligible for financial assistance, but they diverged on the issue of whether such software could be used to rule a patient ineligible for such assistance (hospitals thought it could be used for this purpose, while patient advocacy organizations thought it should not). Hospitals and patient advocacy organizations also held divergent opinions about whether hospitals should be held liable for the practices of third party debt collectors; hospitals thought they should not be held liable, while patient advocacy organizations argued that they should.

In 2014, the Treasury promulgated the final rule. At first glance, it appears that hospitals did not secure the concessions they sought in their public comments. The term “extraordinary collection actions” was defined to include selling an individual’s debt to a third party as well as reporting adverse information to credit bureaus. In addition, hospitals could not deem patients to be ineligible for financial assistance without first allowing them to apply. Hospital facilities were held liable for the ECAs of third parties to which the debts had been sold or assigned. 22

There were, however, aspects of the rule that favored the hospitals’ positions. Hospitals might not be liable for the actions of third-party debt collectors if the violation was neither willful nor egregious, and if the hospital facility “acts reasonably and in good faith to supervise and enforce the 501(r)(6) obligations” and “corrects any contractual violations it discovers.” 22 Hospitals were not required to use presumptive eligibility software or enrollment in another public benefit program to presumptively determine whether patients were eligible for financial assistance, though they were allowed to do so.

While these rules afford some measure of protection to patients, the regulations provide a minimalist definition of “reasonable efforts” to determine eligibility for financial assistance. After all, what does a “reasonable effort” entail? In the final rule, a hospital can be said to have made such efforts if it has notified the patient that there is an FAP, given the patient an opportunity to remedy an incomplete application, and processed any complete application to determine eligibility. 22 In other words, federal regulations allow a hospital to sue a patient even if the patient qualifies for assistance, as long as the patient has not successfully completed the application for charity care. There is no positive obligation to turn to presumptive eligibility for patients who have not completed a financial assistance application before billing patients or resorting to ECAs. As a result, low-income patients face persistent collection efforts as well as legal action and adverse action on credit reports arising from medical debts. 23

Some states have enacted laws to help patients who qualify for financial assistance to receive it. In 2020, Maryland enacted a new law that required hospitals to offer free medically necessary care to patients with family incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level (the ACA had left it up to hospitals to decide at which income levels patients will qualify for free and discounted care). The Maryland law also required hospitals to provide free medically necessary care without the need to send in an application to patients living in a household that received certain public benefits such as SNAP, the Energy Assistance Program, WIC, or free and reduced-cost school meals. 24

Some hospitals have also gone beyond federal requirements to rule patients eligible for financial assistance before they are ever sent a bill. Since 2017, the billing department at Oregon Health and Sciences University in Portland, Oregon has used software sold by Experian to assess a patient’s presumptive eligibility for charity care. Kristi Cushman, the Director of Patient Access Services, stated that before they began using their presumptive eligibility software, applying for financial assistance could be difficult for patients. 19 More than half who applied for charity care submitted an incomplete application. Since the change, whenever a patient presents to the ED or an outpatient office and tells the registration staff that they are either uninsured or that they will have difficulty affording their copayment or deductible, the hospital offers to screen them for financial assistance and Medicaid eligibility. If the patient agrees, the hospital uses the software to determine whether the patient is likely to qualify for charity care, and actively offers it to eligible patients. 19

Similar software has been available for decades. In 2005, Modern Healthcare reported that hospital financial counselors could use software to proactively determine if a patient would likely qualify for charity care or a state assistance program such as Medicaid. Journalist Vince Galloro noted that it could “avoid traumatizing low-income patients with medical bills that they can’t afford to pay.” 25

Making the use of presumptive eligibility software at the point of care standard practice could limit the toll of medical debt on low-income patients. The IRS did not seriously entertain this possibility in defining “reasonable efforts” during the regulatory process after the passage of the Affordable Care Act. Partly as a result, since the announcement of the 501(r)(6) regulations, low-income patients who should have qualified for charity care continue to face extraordinary collection actions. 26 Federal agencies have, of late, revisited and criticized long-standing but harmful practices related to medical debt. After the CFPB issued a report on the harms of credit reporting in 2022, the 3 major credit agencies announced they would remove a large portion of medical debt from credit reports. 27 The anemic nature of hospital efforts to determine whether patients qualify for charity care before pursuing them aggressively for unpaid debts is a ripe subject for a similar critique.

Conclusions

Public comments provide a window into the process of interest group lobbying for more favorable federal regulations. The letter of the law is, in many cases, not the end of the story. Even after the passage of the ACA, hospitals worked to minimize the costs and administrative burdens of regulations pertaining to financial assistance, billing, and collections. In the process, they helped define the effects of the law in such a way that low-income patients could legally be pursued, and even taken to court, over debts that they should not have had to pay according to hospitals’ financial assistance policies. With presumptive eligibility software so readily available, the case for revisiting these regulations, and reconsidering the definition of “reasonable efforts” to determine financial eligibility, has become overwhelming. In the past, hospitals have worked to ensure that IRS regulations were rewritten to decrease their obligations to care for impoverished patients. Today, most hospitals still require low-income patients to submit onerous applications to prove their eligibility for free or discounted care. With an estimated 100 million Americans carrying medical debt in some form, the time has come to relieve patients of the burden of proving their worthiness for assistance.

Acknowledgments

No acknowledgments.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement: The data for this study is already publicly available online, as it involves public comments on IRS/Treasury Regulations.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Statement: This study involved analysis of publicly available comments on a government website, so did not require IRB approval.

Informed Consent/Patient consent: This study involved analysis of publicly available comments, so did not require informed consent.

Trial Registration Number/Date: This study was not a clinical trial.

Other Journal Specific Statements as Applicable: N/A

ORCID iD: Luke Messac  https://orcid.org/0009-0005-8790-2967

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-8790-2967

References

- 1. Levey N. Investigation: Many US hospitals sue patients for debts or threaten their credit. NPR, December 21, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pollack RICK. Article on Charity Care Shortsighted. American Hospital Association Blog; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carare O, Singer S, Wilson E. Exploring the Connection Between Financial Assistance for Medical Care and Medical Collections. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, August 24, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rau J. Patients eligible for charity care instead get big bills. Kaiser Health News, October 14, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stahl EM. What you need to know about presumptive eligibility for hospital financial assistance. Medium, June 20, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Public Law 111-148, Section 9007. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation. Technical Explanation of the Revenue Provisions of the ‘Reconciliation Act of 2010’ As Amended, In Combination with the ‘Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. March 21, 2010, JCX-18-10:82. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Internal Revenue Service. Additional requirements. https://www.regulations.gov/document/IRS-2012-0036-0001 Accessed January 23, 2023.

- 9. Haynes-Maslow L, Andress L, Jilcott Pitts S, et al. Arguments used in public comments to support or oppose the US Department of Agriculture's minimum stocking requirements: a content analysis. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:1664-1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Internal Revenue Service. Rev. Rul. 56–185, 1956–1 C.B. 202, 1956. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/rr56-185.pdf.

- 11. Everson M. Internal Revenue Service, in US House of Representatives Committee, in US House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means, The Tax-Exempt Hospital Sector. Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Colombo J. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means, the Tax-Exempt Hospital Sector. Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bromberg R. The charitable hospital. Cathol Univ Law Rev. 1970;20:243. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bai G, Hyman D. Tax exemptions for nonprofit hospitals: it’s time taxpayers get their money’s worth. STATNews, April 5, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lucinda Ehnes to Internal Revenue Service. Letter Re: Notice of Proposed Rulemaking: Additional Requirements for Charitable Hospitals. September 20, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Joanne Conroy to Internal Revenue Service. Letter re: Additional Requirements for Charitable Hospitals, IRS Reg-130266-11. September 24, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cheryl Fish-Parcham and Michelle Gady to Internal Revenue Service, FamiliesUSA, September 24, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Personal interview with Kristi Cushman and Desember Terry, September 28, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Robert Waikus and Stephanie Switzer to Internal Revenue Service, Letter Re: Notice of Proposed Rulemaking RIN 1545-BK57, October 4, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Colorado Consumer Health Initiative, Public Comment, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Internal Revenue Service. Additional Requirements for Charitable Hospitals; Community Health Needs Assessments for Charitable Hospitals; Requirements of a Section 4959 Excise Tax Return and Time for Filing the Return. December 31, 2014. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2014/12/31/2014-30525/additional-requirements-for-charitable-hospitals-community-health-needs-assessments-for-charitable [PubMed]

- 23. Mathews AW, Fuller A, Evans M. Hospitals often don’t help needy patients, even those who qualify. Wall Street Journal, November 17, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maryland State Bill HB 1420. Hospitals: financial assistance policies and bill collections. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Galloro V. Making the best of a bad (debt) situation; healthcare organizations shake up their policies in light of increased scrutiny of charity care. Mod Healthc. 2005;35:40-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. North Carolina Office of State Treasurer. Hospital lawsuits. August 2023. https://www.shpnc.org/hospital-lawsuits-interviews-defendants/download?attachment

- 27. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Medical Debt Burden in the United States. February 2022. [Google Scholar]