Abstract

Although complement-mediated bactericidal activity in serum has long been known to be very important in host defense against Neisseria meningitidis, recent studies have shown that opsonic phagocytosis by neutrophils is also important. The purpose of this study was to determine if endemic group C N. meningitidis strains were susceptible to nonopsonic (complement- and antibody-independent) phagocytosis by human neutrophils, which is a well-described phenomenon for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Gonococci that possess one or more of a group of heat-modifiable outer membrane proteins (called opacity-associated [Opa] proteins) are phagocytosed by neutrophils in the absence of serum. We found that four serogroup C meningococcal strains bearing the lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) structure on lipooligosaccharide (LOS) were phagocytosed by neutrophils in the absence of antibody and active complement. Confocal microscopy confirmed that the organisms were internalized by neutrophils. This susceptibility was not restricted to carrier isolates, since two of the strains were cultured from blood or cerebrospinal fluid. All four strains expressed Opa protein and had relatively less endogenous LOS and capsule sialylation compared to six strains that were resistant to this type of phagocytosis. Nonopsonic phagocytosis of two of the four strains was inhibited by exogenous sialylation of LOS LNnT and the binding of monoclonal antibody to LNnT. However, an isogenic mutant that lacked the LNnT structure was fully susceptible to nonopsonic phagocytosis. We conclude that group C meningococci can be phagocytosed by neutrophils in the absence of antibody and active complement possibly by two different mechanisms. Expression of Opa protein and downregulation of endogenous surface sialic acids analogous to what is seen for N. gonorrhoeae might be necessary for N. meningitidis as well.

Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B and C strains cause nearly all of the cases of disseminated disease in the United States today. Although complement-mediated bactericidal activity in serum has long been known to be very important in host defense (13), recent studies (10, 37, 38) have shown that meningococci are susceptible to opsonic phagocytosis by neutrophils. The relative importance of this immune effector mechanism, particularly in late-complement-component-deficient individuals and infants, remains to be elucidated.

Most strains of N. meningitidis serogroup B and C express lipooligosaccharide (LOS) molecules that terminate in the lacto-N-neotetraose structure (LNnT; GalB1→4GlcNAcB1→3GalB1→4Glc) that is shared with human paragloboside series glycosphingolipids (16). In particular, human leukocytes bear the N-acetyllactosamine structure (GalB1→4GlcNAcB1→R) (5, 54). LNnT is a major site of sialylation of meningococcal LOS (21, 22). Group B and C N. meningitidis can endogenously sialylate LOS (22) and do so to various degrees. Some strains express LOS with LNnT that is not endogenously sialylated, while others are heavily sialylated (10). The degree of endogenous sialylation was found to be a fairly stable attribute of different strains (10). Serogroup B and C N. meningitidis strains can also add additional sialic acid (exogenous sialylation) when grown in the presence of CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-NANA). Monoclonal antibody (MAb) 1B2 binds to LNnT on the 4.5-kDa component of meningococcal LOS. The binding of this MAb is blocked by the addition of both endogenous and exogenous sialic acid to LNnT, and this loss of binding can serve as a surrogate marker for LOS sialylation (10, 21, 22).

We have previously shown (10) that for endemic group C strains, the degrees of endogenous LOS sialylation and amounts of sialic acid capsule were associated with each other and with resistance to opsonic phagocytosis by human neutrophils. Strains with the least amount of sialic acid were extremely sensitive to opsonic phagocytosis. It was also found that four of the least-sialylated strains were phagocytosed in the presence of antibody but without active complement (heat-inactivated pooled human serum). The purpose of the present study was to determine if these four strains were susceptible to nonopsonic (complement- and antibody-independent) phagocytosis, a well-described phenomenon for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Gonococci that possess one or more of a group of heat-modifiable outer membrane proteins called opacity-associated proteins (Opa proteins) are phagocytosed by neutrophils in the absence of serum (12, 28, 32–35, 48). Most gonococci express LOS with LNnT but cannot endogenously sialylate this structure (23). Exogenous sialylation by growth in CMP-NANA, however, has been shown to markedly reduce nonopsonic interactions of Opa-positive gonococci with neutrophils (33). N. meningitidis strains express opacity-associated proteins Opa and Opc. Opa proteins are closely related to Opa proteins of N. gonorrhoeae, while Opc is unique to meningococci (2).

(This study was presented in part at the 10th International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference, Baltimore, Md. 8 to 13 September 1996, and at the 33rd Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, San Francisco, Calif., 16 to 18 September 1995.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

N. meningitidis strains.

Four endemic, serogroup C meningococcal strains have previously been described (10). Two were isolated from blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and two were carrier isolates. All strains were encapsulated as evidenced by MAb binding to group C polysaccharide, and all of the strains made LOS bearing the LNnT structure (10). These four strains were not only very sensitive to phagocytosis by neutrophils in the presence of antibody and active complement but were also phagocytosed in heat-inactivated serum (10). One additional serogroup Y meningococcal strain (8032) was used in this study and has been described elsewhere (9, 11).

For phagocytosis assays, the bacteria were prepared as follows. Organisms from frozen stock cultures were grown overnight in 5% CO2 on gonococcal complex (GC) agar with 1% supplement and used to inoculate modified Frantz liquid medium (17). They were grown to mid-log phase by end-over-end rotation at 37°C in polystyrene tubes (12 by 75 mm) (10, 19). The bacteria were washed twice in gonococcal buffer (GB) as described by Ross and Densen (36) and suspended in GB to an optical density at 580 nm (OD580) of 0.10 (108 organisms/ml) (37).

MAbs.

MAb 1B2 is an immunoglobulin M (IgM) that was obtained from mice immunized against lacto-N-nor-hexaosylceramide and has been shown to bind to glycoconjugates bearing the terminal N-acetyllactosamine structure (GalB1→4GlcNAcB1→R) on human leukocytes (5, 54) and to neisserial LOSs that bear the LNnT structure (15, 21). MAb 1B2 has binding characteristics similar to those of MAb 3F11 (21). The binding of this MAb is blocked by the addition of sialic acid to LNnT, and this loss of binding can serve as a surrogate marker for LOS sialylation (10, 21, 22, 54). The cell line (1B2-1B7) for production of this MAb was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.).

MAb B306 recognizes the meningococcal Opc protein found in the outer membrane complex (OMC) (2) and was a gift of M. Achtman (Max-Planck-Institut für Molekulare Genetik, Berlin, Germany). MAbs specific for serotype proteins 2a, 2b, and 2c (class 2), 15 (class 3), and p1.2 and p1.16 (class 1) were provided by W. D. Zollinger (Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Washington, D.C.). J. T. Poolman (Rijksinstitut voor Volksgezonheid, Bilthoven, Netherlands) provided an additional MAb directed at a class 1 protein (p1.15). J. Luk (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio) kindly provided a murine MAb IgM supernatant (SN; JL5/2.1) against the rat kidney epithelial chloride ion channel.

MAb 1B2 was purified from cell culture supernatant with the Immunopure IgM Purification kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). The manufacturer’s instructions were followed. The purity of the IgM was checked by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under reducing conditions (7). The IgM concentration was assessed spectrophotometrically at A280 with a Response UV-VIS Spectrophotometer (Gilford, Oberlin, Ohio) (7).

OMC.

OMC antigens were purified from whole organisms as previously described (39, 56).

Whole-cell ELISA.

We used MAbs and the whole-cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method of Abdillahi and Poolman (1) to serotype proteins of the meningococcal strains and to screen the strains for expression of various epitopes. Briefly, meningococci were washed and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) to an OD640 of 0.1. This suspension was used to coat microtiter wells (Immulon 1; Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, Va.) that were then reacted with diluted MAb. After incubation with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody, the wells were developed and the A410 was read with a Dynatech MR5000 Microplate Reader.

SDS-PAGE analysis.

The proteins and LOS in purified OMC or whole cell-lysates (18) were separated by SDS-PAGE by a modification of the method of Laemmli as described elsewhere (10, 40). Purified OMC from meningococcal strain 8032 was included as a molecular mass standard for LOS molecules. This strain makes six LOSs with determined molecular masses of 5.4, 5.1, 4.5, 4.0, 3.6, and 3.2 kDa (10, 18). The LOS molecules were visualized by silver staining (47) and proteins were stained with Coomassie R-250 (Sigma). Heat modifiability of outer membrane proteins in whole-cell lysates or OMC was determined by the method of Poolman et al. (31). This method, which is performed without urea, identifies Opa but not Opc proteins (2).

Serum.

Pooled normal human serum that was depleted of C8 (C8D) was obtained from Quidel Q (San Diego, Calif.). Hypogammaglobulinemic serum (HGS) was obtained from an adult with x-linked agammaglobulinemia who had not received immunoglobulin therapy for 1 year. His serum contained 41-mg/dl IgG (normal range, 620 to 1,400 mg/dl), 7-mg/dl IgM (normal range, 40 to 345 mg/dl), and 2-mg/dl IgA (normal range, 70 to 390 mg/dl).

Isolation of neutrophils.

Neutrophils were isolated from the venous blood of healthy adult volunteers as described elsewhere (10). Purity was >90 to 95%.

Neutrophil phagocytosis assays.

We used the assay described by us (10) to measure opsonic phagocytosis of N. meningitidis. C8D serum was used to allow complement activation through C3 (necessary for complement-dependent phagocytosis) but not through C9 (necessary for complement-mediated bacterial lysis). Heat-inactivated C8D (56°C for 30 min) was used to measure phagocytosis in the absence of C3 deposition on the organisms (36). The opsonic phagocytosis assay consisted of a reaction mixture containing bacteria (1.25 × 106 CFU), neutrophils (1.25 × 106 cells), and 10% C8D; a reaction mixture containing bacteria, neutrophils, and heat-inactivated C8D; and a reaction mixture containing bacteria and 10% C8D. GB was added to each tube to bring the final volume to 250 μl. Survival was expressed as the percentage of organisms at time zero that survived to 60 min.

A modification of the above assay was used to measure nonopsonic phagocytosis of meningococci. The assay consisted of a reaction mixture of bacteria and neutrophils in GB and a reaction mixture of bacteria in GB. Because preliminary experiments showed that some strains survived less well than others in GB alone, 10% heat-inactivated HGS was added to all tubes in all nonopsonic phagocytosis assays, except for one experiment in which strain 15029 was grown without CMP-NANA, with CMP-NANA, or with CMP-NANA followed by treatment with neuraminidase. In some experiments, after a 60-min incubation with bacteria, neutrophils were washed and suspended in 2% paraformaldehyde for analysis by confocal microscopy.

Confocal microscopy.

To determine whether meningococci were intracellular or merely adherent to the neutrophil membrane in the nonopsonic phagocytosis assays, we used the dyes YOYO-1 and DilC18[3] (Molecular Probes, Inc.) with confocal microscopy. YOYO-1 is a fluorescent nucleic acid stain which is excited at 488 nm and emits at 509 nm. When bound to nucleic acid, the fluorescence of this dye is enhanced 500-fold. DilC18[3] is a cationic membrane tracer with excitation at 550 nm and emission at 565 nm. This dye stains plasma and vacuolar membranes with high specificity (Molecular Probes Catalog). The neutrophil samples in paraformaldehyde were mixed with DilC18[3] at a final concentration of 5 μM. After incubation at 37°C for 10 min, the samples were spread onto a microscope slide, dried, and stained with 0.5 μM YOYO-1 (14, 24). Stained samples were viewed by confocal microscopy with an MRC 1024 microscope equipped with a Kr/Ar laser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) The red and green channels were scanned simultaneously.

Inhibition of nonopsonic phagocytosis by exogenous sialylation of LOS.

The effect of exogenous LOS sialylation on sensitivity to nonopsonic phagocytosis was assessed by growing meningococci in broth with 200-μg/ml CMP-NANA (Sigma). The organisms were washed twice and used in phagocytosis assays as described above. In one experiment, organisms that were grown in CMP-NANA were then treated for 1 h with 400 mU of Clostridium perfringens neuraminidase (type V; Sigma) per ml to remove sialic acid from meningococcal LOS. The binding of MAb 1B2 to LOS on these strains as measured by whole-cell ELISA was used to monitor exogenous LOS sialylation, since addition of sialic acid decreases the binding of this MAb (10, 22).

Inhibition of nonopsonic phagocytosis by MAb 1B2.

Meningococci and neutrophils both express the terminal N-acetyllactosamine structure that binds MAb 1B2 (5). The effect of this IgM antibody on the phagocytosis of bacteria in the absence of C3 deposition and other antibodies was examined. Because there is no evidence that neutrophils bear receptors for the Fc portion of IgM analogous to those for IgG, intact IgM molecules rather than Fab fragments were used. MAb 1B2 SN was dialyzed with PBS overnight at 4°C. Various amounts of SN were then added to (i) the reaction tube that contained bacteria, neutrophils, and heat-inactivated HGS and to (ii) the tube that contained bacteria and heat-inactivated HGS. GB was added to bring the final volume to 250 μl. In some experiments, purified 1B2 or a dialyzed murine IgM MAb SN (JL5/2.1) was substituted for MAb 1B2 SN. This MAb bound an epitope on the rat kidney epithelial chloride ion channel and did not bind to meningococci as assessed by whole-cell ELISA. Survival of the bacteria at 60 min was measured.

We then examined the effect of preincubating the bacteria in MAb 1B2 prior to use in the nonopsonic phagocytosis assay. Bacteria (1.25 × 106 CFU) were incubated in GB or GB plus 25 μl of MAb 1B2 SN for 30 min at 37°C. Total volume was kept at 250 μl. The bacteria were then pelleted by centrifugation, washed once, and repelleted. Neutrophils, heat-inactivated HGS, and GB or heat-inactivated HGS and GB were added to the bacteria that were and were not preincubated in MAb 1B2. Survival at 60 min was determined. In some experiments, MAb JL5/2.1 was substituted for MAb 1B2.

The finding of Campos et al. (5) that MAb 1B2 bound to the terminal N-acetyllactosamine structure on human neutrophils was confirmed by standard flow cytometry (FACScan; Becton-Dickinson). Then, 500 μl of 1.25 × 107 neutrophils per ml of GB was incubated with 125 μl of MAb 1B2 SN, 125 μl of MAb JL5/2.1 SN, or 125 μl of GB for 30 min at 4°C. The neutrophils were then washed twice and resuspended in GB to the original concentration of 1.25 × 107 neutrophils per ml. These neutrophils were then used in the nonopsonic phagocytosis assay.

PGM-deficient mutant.

To examine the role of the LNnT LOS structure in nonopsonic phagocytosis, an isogenic mutant (8026-R6) that lacked this LOS structure was made. The Tn916 mutants of meningococcal strain NMB that were generated by Stephens et al. (44) included a mutant designated NMB-R6 that expressed only one LOS of 3.1 to 3.2 kDa, while the parent NMB expressed a 4.5-kDa LOS that contained LNnT and bound MAb 1B2. The defect was identified as a deficiency of phosphoglucomutase (PGM), which converts glucose 6-phosphate to glucose-1-phosphate (44). Mutants were unable to add glucose to heptose. Genomic DNA from the tetracycline-resistant NMB-R6 was used to transform strain 8026 to a pgm-deficient mutant as described elsewhere (44, 55).

Strain 8026 was grown overnight in 5% CO2 on GC agar with 1% supplement, and strain 8026-R6 was grown on identical agar with the addition of 5 μg of tetracycline per ml. For each plate, a stock culture was made and divided into aliquots to be stored at −70°C. Each aliquot was used only once. Mid-log-phase organisms were used in the phagocytosis assays and also resuspended in PBS for whole-cell ELISA as described above. Strains 8026 and 8026-R6 were always analyzed together in the phagocytosis assays.

Statistical analysis.

Data from groups are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Differences before and after experimental modifications were analyzed by the paired-sample, two-tailed t test.

RESULTS

Characterization of endemic serogroup C strains.

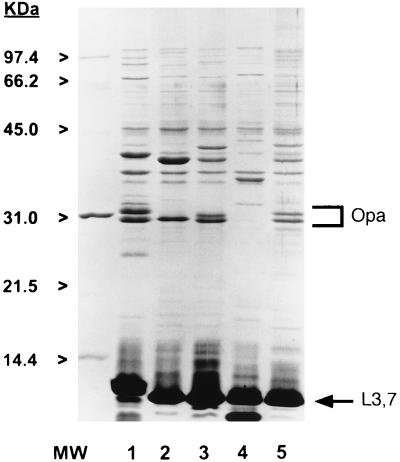

Characteristics of the four serogroup C isolates are shown in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the SDS-PAGE-separated LOS and protein molecules of the strains. All of the strains expressed L3,7 LOS bearing LNnT that bound MAb 1B2 on whole-cell ELISA. All of the strains also made at least one heat-modifiable class 5 protein (Opa) as assessed by SDS-PAGE. MAb B306, which is specific for Opc protein, was used in the whole-cell ELISA to determine if any of the strains expressed this protein. Only one, strain 15031, bound MAb B306. This strain was associated with nasopharyngeal carriage rather than disseminated disease. The whole-cell ELISA was repeated three times for each strain with consistent results. The strains were clearly positive or negative based on MAb B306 binding. Growth phase (mid log versus stationary) and nonselective passage of the strains did not influence the expression of Opc. For comparison, six other group C LNnT bearing strains that were resistant to nonopsonic phagocytosis were also examined for expression of Opa and Opc. All six of these strains were Opa positive, while two were Opc positive. One Opc-positive strain was isolated from CSF, and one was isolated from the middle ear fluid of a child with acute otitis media who did not develop disseminated meningococcal disease.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of four endemic group C N. meningitidis strains that are sensitive to nonopsonic phagocytosis by neutrophils

| Strain | Proteina | Opa | Opc | LNnT (L3,7) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8026 | NT:NT | + | − | + | Case study (15-yr-old patient) |

| 15021 | NT:NT | + | − | + | CSF (5-mo-old patient) |

| 15029 | NT:p1.15 | + | − | + | Throat (10-yr-old patient) |

| 15031 | NT:NT | + | + | + | Throat (10-yr-old patient) |

Class 2 or 3: class 1 (MAbs specific for serotype proteins 2a, 2b, or 2c [class 2], 15 [class 3], and p1.2, p1.16, or p1.15 [class 1]). NT, nontypeable.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE-separated LOS and proteins in purified OMC of group C strains 8032 (lane 1), 8026 (lane 2), 15029 (lane 3), 15021 (lane 4), and 15031 (lane 5). Purified OMC from meningococcal strain 8032 was included as a molecular mass standard for LOS molecules. This strain makes six LOSs with determined molecular masses of 5.4, 5.1, 4.5, 4.0, 3.6, and 3.2 kDa. The LOS molecules were visualized by silver staining, and proteins were stained with Coomassie R-250.

Phagocytosis of N. meningitidis.

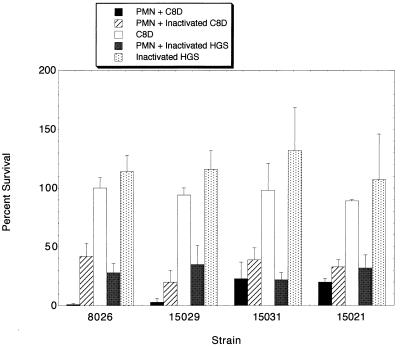

The four serogroup C meningococcal strains were assessed for sensitivity to phagocytosis by neutrophils with and without opsonization. Figure 2 shows that all four strains were phagocytosed when opsonized with C3 and antibody (C8D serum; the C8D pooled human serum contained significant amounts of antibody against meningococci as assessed by whole-cell ELISA). In addition, all four strains were also phagocytosed in the absence of active complement (heat-inactivated C8D) and in the absence of active complement and antibody (heat-inactivated HGS). The control tubes without neutrophils indicated that the bacteria showed excellent survival (even growth) during the 60-min incubation period in C8D-pooled serum and heat-inactivated HGS.

FIG. 2.

Phagocytosis assays of four group C meningococcal strains; mean percentages of organisms at time zero that survived for as long as 60 min in buffer with PMN and (i) C8D (serum with active complement and antibody), (ii) heat-inactivated C8D (serum with antibody but not active complement), or (iii) heat-inactivated HGS (serum without active complement or antibody). Results for control tubes included mean percentages of organisms at time zero that survived for as long as 60 min in buffer (without PMN) and (i) C8D or (ii) heat-inactivated HGS. Error bars denote standard deviations. PMN, neutrophils.

Two of the strains, 8026 and 15029, were nearly completely phagocytosed when incubated with neutrophils in C8D pooled serum. Under conditions without active complement and antibody, survival increased but was still less than 50%. The other two strains, 15031 and 15021, showed rates of survival similar to those of strains 8026 and 15029 in phagocytosis assays with heat-inactivated HGS. Of interest, however, is that the survival rates of these two strains were nearly the same in phagocytosis assays with and without active complement and antibody. This would indicate that opsonization played little role in the phagocytosis of strains 15031 and 15021 while it increased the phagocytosis of strains 8026 and 15029.

In one set of nonopsonic phagocytosis assays, the survival of the strains was determined after 30 min as well as after 60 min of incubation with neutrophils. For strains 8026 and 15029, little phagocytosis occurred by 30 min. In contrast, for strains 15031 and 15021, most of the phagocytosis occurred in the first 30 min. These data indicate that strains 15031 and 15021 are phagocytosed more rapidly than strains 8026 and 15029 under conditions without complement and antibody opsonization.

Evaluation of intracellular status of the bacterium.

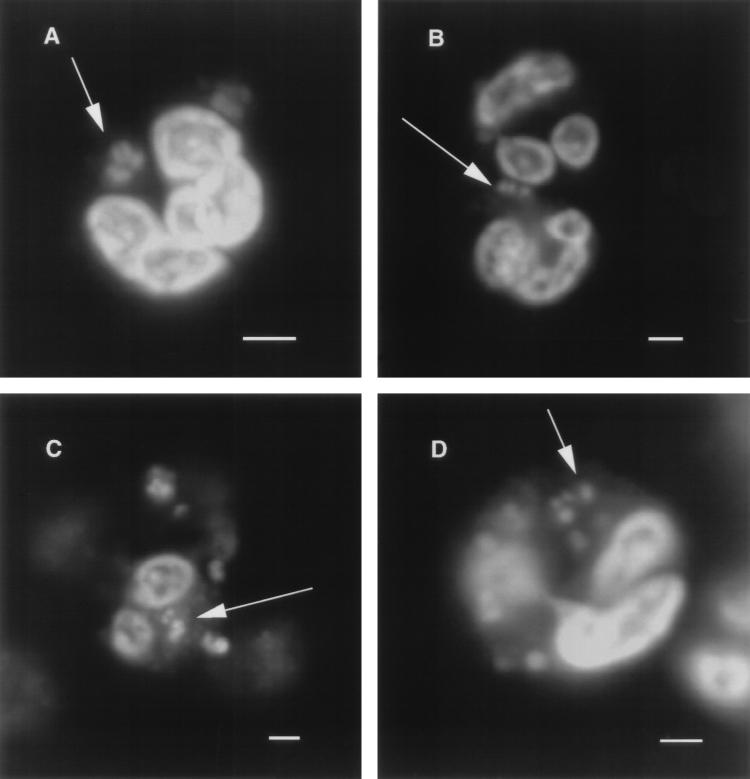

Confocal microscopy was used to determine if the meningococcal strains were internalized by neutrophils in the nonopsonic phagocytosis assays or if the organisms were merely adherent to the neutrophil surface. As can be seen in Fig. 3, all four strains were found inside neutrophils after a 60-min incubation with heat-inactivated HGS.

FIG. 3.

Confocal microscopic analysis of neutrophils from nonopsonic phagocytosis studies with meningococcal strains 8026 (A), 15021 (B), 15029 (C), and 15031 (D). Each panel shows a 1-μm optical section of a neutrophil containing one or more ingested meningococci. The white arrows point to the organism within neutrophils. Scale bars, 2 μm.

Exogenous sialylation of LOS.

The effect of adding sialic acid to the LOS on the sensitivity to nonopsonic phagocytosis was examined by growing the strains in the presence of an exogenous sialylating nucleotide, CMP-NANA (Table 2). While all four strains added sialic acid to LOS bearing LNnT, as evidenced by decreased MAb 1B2 binding upon whole-cell ELISA, only two strains (8026 and 15029) showed a significant increase in survival. Strains 15031 and 15021 showed minimal increases.

TABLE 2.

Survival of group C meningococcal strains grown with and without exogenous CMP-NANA in the presence of neutrophils without complement and antibodya

| Strain | Binding of MAb 1B2

(OD405b) to strains

grown:

|

% Survival of strains grown:

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without CMP-NANA | With CMP-NANA | Without CMP-NANA | With CMP-NANA | ||

| 8026 | 0.87 ± 0.14 | 0.42 ± 0.11 | 30 ± 7 | 65 ± 16 | 0.02 |

| 15029 | 0.78 ± 0.12 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 32 ± 16 | 54 ± 14 | 0.008 |

| 15031 | 0.67 ± 0.07 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 24 ± 6 | 34 ± 10 | 0.07 |

| 15021 | 0.60 ± 0.17 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 30 ± 14 | 37 ± 3 | NS |

Values are means (± standard deviations) for three experiments. The two-tailed paired t test was used to compare results. Decreased binding of MAb 1B2 indicates that more sialic acid bound to LNnT. NS, not significant.

As measured by ELISA.

Strain 15029 was grown in broth without CMP-NANA, with CMP-NANA, and with CMP-NANA followed by treatment with neuraminidase to remove sialic from LOS. The binding of MAb 1B2 to the organisms was used to monitor the sialylation of the LOS, since addition of sialic acid decreases the binding of this MAb. As can be seen in Table 3, exogenous sialylation of LOS enhanced survival, but this effect was lost when the sialic acid was removed with neuraminidase.

TABLE 3.

Survival of strain 15029 in nonopsonic phagocytosis assays under various growth conditionsa

| Condition of growth | MAb 1B2 binding (OD405)b | % Survivalc |

|---|---|---|

| Without CMP-NANA | 0.81 | 15 |

| CMP-NANA | 0.55 | 29 |

| CMP-NANA and neuraminidase | 0.84 | 15 |

Decreased binding of MAb 1B2 indicates that more sialic acid bound to LNnT.

As measured by ELISA.

The phagocytosis assays were serum free. The reaction tubes contained bacteria, neutrophils, and GB. Control tubes contained bacteria, neutrophils, and GB that were incubated at 4°C. Percent survival in control tubes was 98 to 104%.

Inhibition of nonopsonic phagocytosis by MAb 1B2.

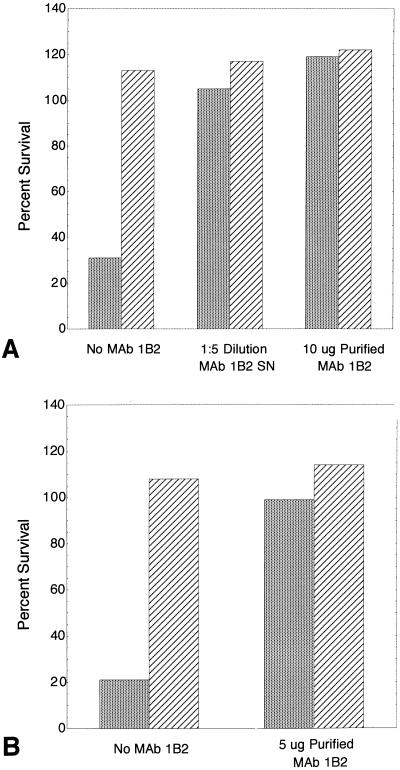

Because sialylation of the LNnT structure on the LOS of two strains inhibited nonopsonic phagocytosis, we sought to determine if the binding of MAb to this structure would inhibit phagocytosis as well. MAb 1B2 was first added directly to the reaction tubes containing bacteria and neutrophils in heat-inactivated HGS and to control tubes containing bacteria in heat-inactivated HGS. Survival was determined after a 60-min incubation. The results of one experiment are shown in Fig. 4A and B. MAb 1B2 SN and 10 μg of purified 1B2 inhibited nonopsonic phagocytosis of strain 15029. The antibody had no effect on the survival of bacteria in the absence of neutrophils (Fig. 4A). Nonopsonic phagocytosis of strain 8026 was also inhibited by the addition of 5 μg of purified MAb 1B2 with survival increasing from 21 to 99% (Fig. 4B). In a separate experiment, the addition of as little as 2.5 μg of purified MAb 1B2 increased the survival of strain 15029 to greater than 100%. In contrast, MAb 1B2 had no effect on the nonopsonic phagocytosis of strains 15031 and 15021.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of nonopsonic phagocytosis of strain 15029 (A) and strain 8026 (B) by MAb 1B2 that binds to the LNnT structure on meningococci and on neutrophils. Values are percentages of organisms at time zero that survived to 60 min in buffer with heat-inactivated HGS with ( ) and without (▨) neutrophils. No MAb 1B2, dialyzed MAb 1B2 SN, or purified MAb 1B2 was added to the reaction tubes at time zero.

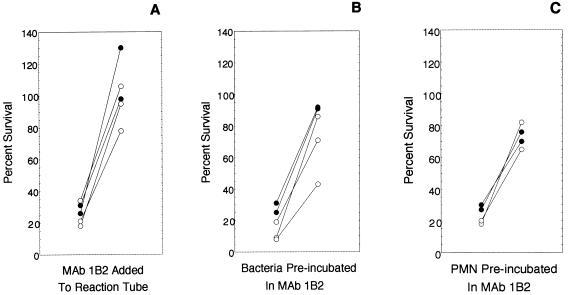

Figure 5A shows in replicate experiments that a 1:10 dilution of dialyzed MAb 1B2 SN added to the reaction tube inhibited nonopsonic phagocytosis of strains 15029 and 8026. In these experiments, MAb 1B2 had no effect on survival of bacteria in the absence of neutrophils. A 1:10 dilution of dialyzed IgM MAb JL5/2.1 SN added to the reaction tubes also had no effect on the survival of bacteria in heat-inactivated HGS with or without neutrophils.

FIG. 5.

Replicate experiments showing the inhibition of nonopsonic phagocytosis of two meningococcal strains (15029 [filled circles] and 8026 [open circles]) by MAb 1B2. Each pair of circles connected by a line denotes one strain in a single assay. Percent survival rates for the strains at 60 min in the presence of neutrophils (PMN) and heat-inactivated HGS were determined. The circle to the left in each pair shows survival without MAb 1B2, and the circle to the right in each pair shows survival with MAb 1B2. (A) Dialyzed MAb 1B2 supernatant added to the reaction tube; (B) preincubation of organisms in MAb 1B2 SN followed by washing; (C) preincubation of neutrophils in MAb 1B2 SN followed by washing.

Because MAb 1B2 binds to both meningococcal LOS and neutrophils, we then sought to determine if MAb 1B2 inhibited phagocytosis by binding to bacteria, neutrophils, or both. Strains 15029 and 8026 were preincubated in MAb 1B2 SN (final dilution, 1:10) washed, and then used in the nonopsonic phagocytosis assays. Figure 5B shows that allowing MAb 1B2 to bind to the LNnT structure of LOS prior to exposure to neutrophils enhanced the survival of these two strains in nonopsonic phagocytosis assays. Preincubation in MAb JL5/2.1 SN had no effect on survival. Preincubation in MAb 1B2 SN had no effect on survival in the absence of neutrophils. Because the assay was performed so that CFU per milliliter at time zero was determined, the effect of preincubation in MAb 1B2 or MAb JL5/2.1 SN on the initial concentration (time zero) of bacteria used in the phagocytosis assays could be monitored. Preincubation either had no effect or slightly increased the concentration of bacteria at time zero. This slight increase did not explain the dramatic increase in survival at 60 min, because preincubation in MAb JL5/2.1 SN also slightly increased the starting inoculum but did not increase survival at 60 min.

Neutrophils were preincubated in MAb 1B2 SN, MAb JL5/2.1 SN, or GB, washed twice, suspended to the original concentration, and used in the nonopsonic phagocytosis assays. Again, strains 8026 and 15029 (but not strains 15021 and 15031) survived much better in assays in which neutrophils were preincubated in MAb 1B2 (Fig. 5C). Preincubation of neutrophils in MAb JL5/2.1 had no effect.

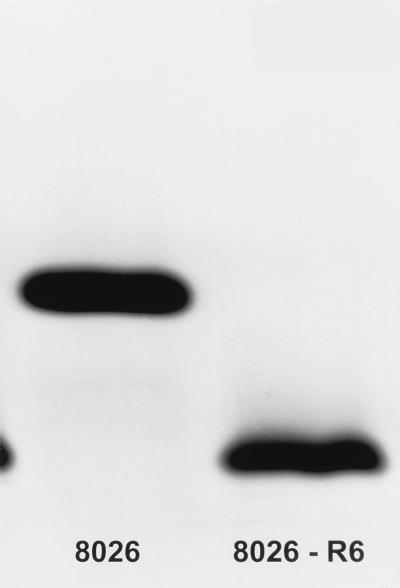

PGM-deficient mutant.

Nonopsonic phagocytosis of two meningococcal strains was inhibited by the binding of sialic acid or MAb 1B2 to the LNnT structure of LOS. To examine the role of the LNnT LOS structure in nonopsonic phagocytosis, an isogenic mutant (8026-R6) that lacked this LOS structure was made. Whole-cell lysates and pk-treated whole-cell lysates of strain 8026 and the PGM-deficient mutant 8026-R6 were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, silver staining of the LOS, and Coomassie R-250 staining of protein molecules. 8026 and 8026-R6 were identical, including previously identified heat-modifiable class 5 proteins, except that 8026-R6 did not express the 4.5-kDa LOS that bears the LNnT structure but did express a new LOS molecule with apparent molecular mass of ≤3.2 kDa (Fig. 6). Immunoblot analysis confirmed that 8026-R6 did not bind MAb 1B2.

FIG. 6.

Proteinase K-treated whole-cell lysates of strain 8026 and the PGM-deficient mutant 8026-R6 were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining of the LOS molecules. 8026-R6 did not express the 4.5 kDa LOS that bears the LNnT structure but did express a new LOS molecule with an apparent molecular mass of ≤3.2 kDa.

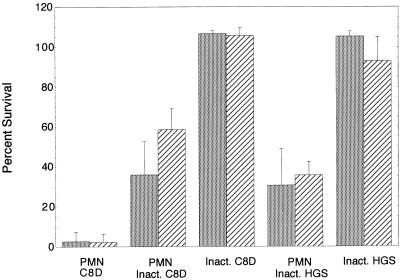

Strains 8026 and 8026-R6 were analyzed together in the phagocytosis assays. The strains grew in broth at similar rates and after washing were suspended in GB to identical OD580s. As determined from the CFU counts at time zero, strain 8026 had an average of 1.5 × 106 ± 0.12 × 106 bacteria per reaction tube, while 8026-R6 had 0.9 × 106 ± 0.088 × 106 bacteria per reaction tube. In numerous phagocytosis assays, variability of time zero inoculum sizes in this range had no influence on percent survival rates. There were no significant differences in percent survival rates for 8026 and 8026-R6 in the opsonic and nonopsonic phagocytosis assays (Fig. 7). Whole-cell ELISA of the organisms used in the phagocytosis assays confirmed that 8026 bound MAb 1B2 strongly while 8026-R6 did not bind this MAb and thus did not make LOS molecules containing LNnT. These data suggest that the loss of the LNnT structure did not interfere with opsonic and nonopsonic phagocytosis of this strain.

FIG. 7.

Percent survival rates for strain 8026 ( ) and the PGM-deficient mutant 8026-R6 (▨) in opsonic and nonopsonic phagocytosis assays. There were no significant differences in percent survival rates for 8026 and 8026-R6 in the opsonic and nonopsonic phagocytosis assays. Error bars denote standard deviations. PMN, neutrophils; inact., heat inactivated.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that four serogroup C meningococcal strains bearing the LNnT structure on LOS were phagocytosed by human neutrophils in the absence of antibody and active complement. This susceptibility was not restricted to carrier isolates, since two of the strains were cultured from blood or CSF. All four were encapsulated and expressed at least one Opa outer membrane protein. However, six additional group C strains that expressed both LNnT and Opa were resistant to nonopsonic phagocytosis (10). These findings suggested that expression of LNnT and/or Opa might be necessary but not sufficient for susceptibility to nonopsonic phagocytosis. Expression of Opc was not associated with this type of neutrophil interaction.

Therefore, the role of LNnT in the nonopsonic interaction of meningococci and neutrophils was further investigated. Exogenous sialylation of LOS LNnT significantly inhibited nonopsonic phagocytosis for two (8026 and 15029) of the four strains, and this inhibition could be reversed by removing LOS sialic acid with neuraminidase. This type of phagocytosis was also inhibited for the same two strains by the binding of an IgM MAb (1B2) specific for the LNnT structure on the bacteria. In contrast, loss of the LNnT structure had no effect on the sensitivity of an isogenic mutant to nonopsonic phagocytosis. Thus, the LNnT structure on meningococcal LOS does not appear to function as a ligand for a neutrophil receptor; rather, the sialylation of LNnT or the binding of an IgM antibody to this structure appears to interfere with another ligand-receptor interaction. Nonopsonic phagocytosis was also effectively blocked by preincubating the neutrophils in MAb 1B2, which binds to the glycosphingolipid LNnT structure on the neutrophil surface.

The other two strains (15021 and 15031) were internalized by neutrophils in the absence of antibody and active complement, but this process was not inhibited by exogenous sialylation of LOS or binding of MAb 1B2 to LNnT on bacteria or neutrophils. In addition, the nonopsonic phagocytosis of these two strains was more rapid than that of 8026 and 15029. These data suggest more than one mechanism for nonopsonic phagocytosis of meningococci. The interaction of strains 15021 and 15031 with neutrophils was also clearly different than that of 8026 and 15029 in that opsonization with complement and antibody enhanced phagocytosis for strains 8026 and 15029 but had little effect on strains 15021 and 15031.

Nonopsonic lectinophagocytosis by human neutrophils of gonococci bearing the outer membrane protein Opa was recently reviewed by Ofek et al. (29). Opa-bearing organisms bind to human granulocytes in the absence of serum, stimulate oxygen burst, and are ingested and killed (8, 27–29, 33, 41). This Opa-mediated interaction with neutrophils can be inhibited by carbohydrates such as glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine and thus is considered to be lectin mediated (29, 41). Sialylation of LNnT on gonococcal LOS interferes with Opa-mediated attachment to neutrophils, inhibits oxidative burst, and delays killing (19, 33).

Meningococcal Opa proteins bear structural similarities to gonococcal Opa proteins (30, 49). The expression of at least one Opa protein by all four of the group C strains suggests a role for this protein in nonopsonic phagocytosis of meningococci as well. This is supported by the work of McNeil et al., who reported that expression of Opa and, to a much greater extent, Opc correlated with nonopsonic phagocytosis of a capsule-deficient group A meningococcal strain by human monocytes (26). They also found that Opa proteins mediated neutrophil interactions with meningococci but that surface sialic acids (of capsule and LOS) needed to be downregulated (25). Piliation had no effect on nonopsonic phagocytosis of meningococci by either monocytes or neutrophils (25, 26). The six other group C strains that we found to be resistant to nonopsonic phagocytosis of neutrophils (10) also expressed Opa proteins. We previously reported that the four sensitive strains had relatively less endogenous LOS and capsule sialylation compared to the six resistant strains (10). These data suggest that nonopsonic phagocytosis of group C strains might be Opa mediated but that increased LOS and capsule sialylation inhibits this interaction.

Evidence that the neisserial Opa interaction with neutrophils is lectin mediated is supported by the work of Blake et al., who found that gonococcal Opa proteins had a strong affinity for the GalB1→4GlcNAc residue of gonococcal LOS LNnT. Furthermore, the carbohydrate structure on gonococcal LOS that bound Opa proteins most avidly was structurally the same as or similar to that for the epitope defined by MAb 1B2 and was also present on eukaryotic cells. This led the authors to postulate that gonococcal Opa proteins might bind to eukaryotic cells expressing this carbohydrate structure (3). Our flow cytometry analysis confirmed very strong binding of MAb 1B2 to the terminal N-acetyllactosamine structure on the surface of human neutrophils, in agreement with a study of Campos et al. (5). This raises the interesting speculation that meningococcal Opa proteins can bind the MAb 1B2-defined carbohydrate structure on neutrophils to mediate nonopsonic interactions.

Recently, a different neutrophil receptor for meningococcal Opa proteins was suggested, i.e., the CD66a adhesion molecule (biliary glycoprotein), which belongs to the carcinoembryonic antigen family (50, 51). The CD66 cluster of antigens includes structurally related glycoproteins that are members of the larger immunoglobulin supergene family and are upregulated by neutrophil activation (43, 52, 53). They have also been found to activate neutrophils and play a role in neutrophil effector function (20, 42, 45, 46). Virji et al. reported an association of meningococcal Opa proteins with CD66a (50, 51). Other carcinoembryonic antigen family glycoproteins have also recently been implicated as receptors for gonococcal Opa proteins (4, 6).

We conclude that group C meningococci can be phagocytosed by human neutrophils in the absence of antibody and active complement, possibly by two different mechanisms. One mechanism, which is analogous to that in gonococci, is inhibited by exogenous LOS sialylation but not loss of the LNnT structure. The second mechanism of rapid, nonopsonic phagocytosis of two of the strains that is not enhanced by opsonization and is not inhibited by exogenous sialylation of LOS remains to be elucidated. The finding that all four meningococcal strains expressed Opa in association with the established role of this protein in nonopsonic phagocytosis of N. gonorrhoeae suggests that the Opa protein plays a role in nonopsonic phagocytosis of N. meningitidis as well. Further investigation will be necessary to confirm this. Downregulation of endogenous surface sialic acid also appears to be necessary. The role of nonopsonic phagocytosis in the pathogenesis of meningococcal disease will require further investigation but is a potentially important host defense. Although young infants bear the burden of meningococcal disease, colonization with N. meningitidis is much more common than dissemination in these nonimmune, relatively complement-deficient hosts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants AI18384 (M.A.A.) and U19AI38515 (M.A.A.).

We thank Ronda Brady for excellent technical assistance and Melvin Berger for thoughtful discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdillahi H, Poolman J T. Whole-cell ELISA for typing Neisseria meningitidiswith monoclonal antibodies. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;48:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Achtman M, Neibert M, Crowe B, et al. Purification and characterization of eight class 5 outer membrane protein variants from a clone of Neisseria meningitidisserogroup A. J Exp Med. 1988;168:507–525. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake M S, Blake C M, Apicella M A, Mandrell R E. Gonococcal opacity: lectin-like interactions between Opa proteins and lipooligosaccharide. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1434–1439. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1434-1439.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos M P, Grunert F, Belland R J. Differential recognition of members of the carcinoembryonic antigen family by Opa variants of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1997;64:2353–2361. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2353-2361.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campos L, Portoukalian J, Bonnier S, et al. Specific binding of anti-N-acetyllactosamine monoclonal antibody 1B2 to acute myeloid leukemia cells. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28:37–41. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90380-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen T, Gotschlich E C. CGM1a antigen of neutrophils, a receptor of gonococcal opacity proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14851–14856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coligan J E, Kruisbeek A M, Margulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W, editors. Current protocols in immunology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1994. pp. 2.7.1–2.10.4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elkins C, Rest R F. Monoclonal antibodies to outer membrane protein PII block interactions of Neisseria gonorrhoeaewith human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1078–1084. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1078-1084.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estabrook M M, Baker C J, Griffiss J M. The immune response of children to meningococcal lipooligosaccharides during disseminated disease is directed primarily against two monoclonal antibody-defined epitopes. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:966–970. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estabrook M M, Christopher N C, Griffiss J M, Baker C J, Mandrell R E. Sialylation and human neutrophil killing of group C Neisseria meningitidis. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1079–1088. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estabrook M M, Mandrell R E, Apicella M A, Griffiss J M. Measurement of the human immune response to meningococcal lipooligosaccharide antigens by using serum to inhibit monoclonal antibody binding to purified lipooligosaccharide. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2204–2213. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2204-2213.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher S H, Rest R F. Gonococci possessing only specific P.II outer membrane proteins interact with human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1574–1579. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.6.1574-1579.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldschneider I, Gotschlich E C, Artenstein M S. Human immunity to the meningococcus. The role of humoral antibodies. J Exp Med. 1969;129:1307–1326. doi: 10.1084/jem.129.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoagland R P. Handbook of fluorescent probes and research chemicals. In: Larison K D, editor. Molecular probes, handbook of fluorescent probes and research chemicals, 1992–1994. 5th ed. Eugene, Oreg: Molecular Probes; 1996. p. 421. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarvis G A. Analysis of C3 deposition and degradation on Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1755–1760. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1755-1760.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jennings H J, Johnson K G, Kenne L. The structure of an R type oligosaccharide core obtained from some lipopolysaccharides of Neisseria meningitidis. Carbohydr Res. 1983;121:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(83)84020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J J, Mandrell R E, Griffiss J M. Neisseria lactamica and Neisseria meningitidisshare lipooligosaccharide epitopes but lack common capsular and class 1, 2, and 3 protein epitopes. Infect Immun. 1989;57:602–608. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.602-608.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J J, Mandrell R E, Hu Z, Westerink M A, Poolman J T, Griffiss J M. Electromorphic characterization and description of conserved epitopes of the lipooligosaccharides of group A Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2631–2638. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2631-2638.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J J, Zhou D, Mandrell R E, Griffiss J M. Effect of exogenous sialylation of the lipooligosaccharide of Neisseria gonorrhoeaeon opsonophagocytosis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4439–4442. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4439-4442.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein M L, McGhee S A, Baranian J, Stevens L, Hefta S A. Role of nonspecific cross-reacting antigen, a CD66 cluster antigen, in activation of human granulocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4574–4579. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4574-4579.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandrell R E, Griffiss J M, Macher B A. Lipooligosaccharides (LOS) of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidishave components that are immunochemically similar to precursors of human blood group antigens. Carbohydrate sequence specificity of the mouse monoclonal antibodies that recognize crossreacting antigens on LOS and human erythrocytes. J Exp Med. 1988;168:107–126. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandrell R E, Kim J J, John C M, et al. Endogenous sialylation of the lipooligosaccharides of Neisseria meningitidis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2823–2832. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2823-2832.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandrell R E, Lesse A J, Sugai J V, et al. In vitro and in vivo modification of Neisseria gonorrhoeaelipooligosaccharide epitope structure by sialylation. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1649–1664. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumoto B. Methods in cell biology: cell applications of confocal microscopy. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1993. p. 379. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNeil G, Virji M. Meningococcal interactions with human phagocytic cells: a study on defined phenotypic variants. In: Zollinger W D, Frasch C E, Deal C D, editors. Abstracts of the 10th International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference. 1996. pp. 320–321. Baltimore, Md. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNeil G, Virji M, Moxon E R. Interactions of Neisseria meningitidiswith human monocytes. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:153–163. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naids F L, Belisle B, Lee N, Rest R F. Interaction of Neisseria gonorrhoeaewith human neutrophils: studies of purified PII (Opa) outer membrane proteins and synthetic Opa peptides. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4628–4635. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4628-4635.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naids F L, Rest R F. Stimulation of human neutrophil oxidative metabolism by nonopsonized Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4383–4390. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4383-4390.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ofek I, Goldhar J, Keisari Y. Nonopsonic phagocytosis of microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:239–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olyhoek A J M, Sarkari J, Bopp M, Morelli G, Achtman M. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of opc, the gene for an unusual class 5 outer membrane protein from Neisseria meningitidis. Microb Pathog. 1991;11:249–257. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90029-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poolman J T, de Marie S, Zanen H C. Variability of low-molecular-weight, heat-modifiable outer membrane proteins of Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun. 1980;30:642–648. doi: 10.1128/iai.30.3.642-648.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rest R F, Fisher S H, Ingham Z Z, Jones J F. Interactions of Neisseria gonorrhoeaewith human neutrophils: effects of serum and gonococcal opacity on phagocytic killing and chemiluminescence. Infect Immun. 1982;36:737–744. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.2.737-744.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rest R F, Frangipane J V. Growth of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid inhibits nonopsonic (opacity-associated outer membrane protein-mediated) interactions with human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1992;60:989–997. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.989-997.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rest R F, Lee N, Bowden C. Stimulation of human leukocytes by P.II gonococci is mediated by lectin-like gonococcal components. Infect Immun. 1985;50:116–122. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.1.116-122.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rest, R. F., and W. M. Shafer. 1989. Interactions of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with human neutrophils. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2(Suppl.):S83–S91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Ross S C, Densen P. Opsonophagocytosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: interaction of local and disseminated isolates with complement and neutrophils. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:33–41. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ross S C, Rosenthal P J, Berberich H M, Densen P. Killing of Neisseria meningitidisby human neutrophils: implications for normal and complement-deficient individuals. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:1266–1275. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.6.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlesinger M, Greenberg R, Levy J, Kayhty H, Levy R. Killing of meningococci by neutrophils: effect of vaccination on patients with complement deficiency. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:449–453. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider H, Griffiss J M, Williams G D, Pier G B. Immunological basis of serum resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:13–22. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schneider H, Hale T L, Zollinger W D, Seid R, Jr, Hammack C A, Griffiss J M. Heterogeneity of molecular size and antigenic expression within lipooligosaccharides of individual strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun. 1984;45:544–549. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.3.544-549.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shafer W M, Rest R F. Interactions of gonococci with phagocytic cells. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1989;43:121–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.43.100189.001005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skubitz K M, Campbell K D, Skubitz A P N. CD66a, CD66b, CD66c, and CD66d each independently stimulate neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:106–117. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stanners C P, DeMarte L, Rojas M, Gold P, Fuchs A. Opposite functions for two classes of the human carcinoembryonic antigen family. Tumor Biol. 1995;16:23–31. doi: 10.1159/000217925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stephens D S, McAllister C F, Zhou D, Lee F K, Apicella M A. Tn916-generated lipooligosaccharide mutants of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2947–2952. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2947-2952.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stocks S C, Kerr M A, Haslett C, Dransfield I. CD66-dependent neutrophil activation: a possible mechanism for vascular selectin-mediated regulation of neutrophil adhesion. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:40–48. doi: 10.1002/jlb.58.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stocks S C, Ruchaud-Sparagano M, Kerr M A, Grunert F, Haslett C, Dransfield I. CD66: role in the regulation of neutrophil effector function. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2924–2932. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai C, Frasch C E. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Virji M, Heckels J E. The effect of protein II and pili on the interaction of Neisseria gonorrhoeaewith human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:503–512. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-2-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Virji M, Makepeace K, Ferguson D J, Achtman M, Moxon E R. Meningococcal Opa and Opc proteins: their role in colonization and invasion of human epithelial and endothelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:499–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Virji M, Makepeace K, Ferguson D J P, Watt S M. Carcinoembryonic antigens (CD66) on epithelial cells and neutrophils are receptors for Opa proteins of pathogenic neisseriae. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:941–950. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Virji M, Watt S M, Barker S, Makepeace K, Doyonnas R. The N-domain of the human CD66a adhesion molecule is a target for Opa proteins of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:929–939. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watt S M, Fawcett J, Murdoch S J, et al. CD66 identifies the biliary glycoprotein (BGP) adhesion molecule; cloning, expression and adhesion functions of the BGPc splice variant. Blood. 1994;84:200–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watt S M, Sala-Newby G, Hoang T, et al. CD66 identifies a neutrophil-specific epitope within the hematopoietic system that is expressed by members of the carcinoembryonic antigen family of adhesion molecules. Blood. 1991;78:63–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Young W W J, Portoukalian J, Hakomori S. Two monoclonal anticarbohydrate antibodies directed to glycosphingolipids with a lacto-N-glycosyl type II chain. J Biol Chem. 1981;21:10967–10972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou D, Stephens D S, Gibson B W, et al. Lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis in pathogenic Neisseria. Cloning, identification, and characterization of the phosphoglucomutase gene. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11162–11169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zollinger W D, Mandrell R E, Griffiss J M, Altieri P, Berman S. Complex of meningococcal group B polysaccharide and type 2 outer membrane protein immunogenic in man. J Clin Invest. 1979;63:836–848. doi: 10.1172/JCI109383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]