Abstract

The isotype and epitope specificities of antibodies both contribute to the efficacy of antibodies that mediate immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans, but the relationship between these properties is only partially understood. In this study, we analyzed the efficacy of protection of two sets of immunoglobulin G (IgG) isotype switch variants from two IgG3 monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) which are either not protective or disease enhancing, depending on the mouse model used. The two IgG3 MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 have different epitope specificities. Protection experiments were done with A/JCr mice infected intravenously with C. neoformans and administered with 3E5 IgG3 and its IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b switch variants. These experiments revealed that IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG2a were each more effective than IgG3. For 4H3 IgG3 and its IgG1 and IgG2b switch variants, the relative efficacy was IgG2b > IgG1 >> IgG3. The combination of 3E5 IgG3 and 4H3 IgG3 was more deleterious than either IgG3 alone. All IgG isotypes were opsonic for mouse bronchoalveolar cells, with the relative efficacy being IgG2b > IgG2a > IgG1 > IgG3. These results (i) confirm that a nonprotective IgG3 MAb can be converted to a protective MAb by isotype switching, (ii) indicate that the efficacy of protection of an IgG1 MAb can be increased by isotype switching to another subclass, (iii) show that protective and nonprotective IgG MAbs are opsonic, and (iv) provide additional evidence for the concept that the efficacy of the antibody response to C. neoformans is dependent on the type of MAb elicited.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a fungus which is a frequent cause of life-threatening meningoencephalitis in patients with impaired immunity (22, 25). Cryptococcosis has been reported to occur in 6 to 8% of patients with AIDS (7). In immunocompromised individuals, C. neoformans infections are often incurable with conventional antifungal agents, and these patients frequently require lifelong therapy (45). The difficulties involved in the management of cryptococcosis in immunocompromised individuals have led to a reexamination of the potential of antibody-mediated immunity for prevention and therapy of cryptococcal infections. A polysaccharide-tetanus toxoid (TT) conjugate vaccine which is highly immunogenic and can elicit protective antibodies in mice has been made (3, 8, 9). In addition, several monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) have been shown to modify the course of infection in mice, and these may be useful in therapy of human infection (12, 14, 28, 42, 43).

Cell-mediated immunity is generally acknowledged to provide important host defense against C. neoformans infection (4, 20, 26, 31, 42). In contrast, the role of antibody-mediated immunity in host resistance is less certain (2), but there is considerable evidence that administration of some MAbs can modify the course of infection in mice (8, 12, 14, 16, 28, 33). C. neoformans is unusual among fungal pathogens in that it has a polysaccharide capsule composed primarily of glucuronoxylomannan (GXM) (6), which is important for virulence (5). The capsular polysaccharide has been shown to produce a variety of deleterious effects including inhibition of phagocytosis (21), interference with antigen presentation (39), shedding of adhesion molecules (11), inhibition of leukocyte migration (10), and alterations in cytokine production by host effector cells (24, 40, 41). Antibodies to the C. neoformans capsular polysaccharide may contribute to host defense through multiple effects including enhanced opsonization (13, 18, 23, 30, 44), clearance of polysaccharide antigen (15), promotion of granuloma formation (14), and release of oxygen- and nitrogen-derived oxidants (27, 38).

In previous studies, we demonstrated that immunoglobulin G3 (IgG3) MAbs are not protective in various mouse models of cryptococcal infection (32, 42). When one of these nonprotective IgG3 MAbs was switched to IgG1, the IgG1 significantly prolonged animal survival (32, 42). In the present study, we analyzed two families of IgG switch variants generated in vitro from two nonprotective IgG3 MAbs with different epitope specificities. We found that MAbs with different isotypes have different protective efficacies and that switching of nonprotective IgG3 MAbs to IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG2a significantly increased antibody protective efficacy. These studies demonstrate a complex relationship among efficacy of antibody protection, epitope specificity, and isotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. neoformans.

Strain 24067 (serotype D) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.) and maintained on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) at 4°C. For murine infection, C. neoformans was grown at 37°C in Sabouraud dextrose broth (Difco) for 24 h. Yeast cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the inoculum was determined by counting in a hemocytometer and was confirmed by counting the number of colonies after plating on Sabouraud dextrose agar.

MAbs.

The 3E5 IgG3 MAb was generated in response to immunization with the GXM-TT vaccine (3), and it binds all four serotypes of C. neoformans (3). The 4H3 IgG3 MAb was generated in response to infection with the C. neoformans strain GH (3). The IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b switch variants of MAb 3E5 IgG3 MAb and the IgG1 and IgG2b variants of MAb 4H3 IgG3 were generated by in vitro isotype switching as described elsewhere (35, 42). Ascites fluid containing hybridoma protein was obtained by paracentesis of BALB/c mice injected with 107 hybridoma cells into the peritoneal cavity. Prior to hybridoma injection, the mice were primed with Pristane (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). For in vitro studies, antibodies were purified on protein G-Sepharose columns (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) and their concentrations were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assaying (ELISA) relative to isotype-matched standards of known concentrations. Previous studies had established that the MAb constituted approximately 95% of the immunoglobulin of the relevant isotype in the ascites (28). In previous work, we have shown that ascites induced by the NSO myeloma cell line and ascites containing irrelevant isotype-matched MAbs do not modify infection with C. neoformans (28). In addition, in these experiments the ascites containing the different isotypes served as internal controls for each other, since the switch variants were products of the same hybridoma.

ELISA.

Antibody binding to GXM was studied by ELISAs that have been described elsewhere (3). Briefly, the wells in the ELISA plates were coated overnight with 50 μl of a solution of 1-μg/ml GXM from C. neoformans 24067. The plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with serial dilutions of purified MAbs, washed, and incubated with alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG MAbs (Fisher Scientific, Orangeburg, N.Y.). The plates were then washed and developed by adding substrate and determining absorbance at 405 nm. Competition assays between the 3E5 IgG and 4H3 IgG switch variants were performed by adding a constant amount of one MAb (1 to 5 μg/ml) and varying the concentration of the other isotype (0 to 10 μg/ml).

Animal experiments.

Female C5 complement-deficient A/JCr mice aged 6 to 8 weeks were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Protection experiments were performed as described elsewhere (42). Briefly, 10 mice per group were given 1 mg of IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, or IgG3 MAb or PBS. MAbs were administered via intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) 24 h prior to intravenous (i.v.) challenge with 2 × 106 C. neoformans 24067 cells, and mouse deaths were recorded daily.

Macrophage experiments.

Bronchoalveolar macrophages were obtained from A/JCr mice by lung lavage as described previously (14). For the phagocytosis assay, 105 cells per well were plated in 96-well tissue culture plates (Falcon; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, N.J.) and cultured overnight at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) with or without 500 U of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (Genzyme, Cambridge, Mass.) per ml. Virtually all of the cells attach, spread out, and extend pseudopods. C. neoformans was incubated with purified MAb for 1 h at 37°C and then added to the macrophages. After the addition of C. neoformans, the plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 h and washed three times with sterile PBS to remove nonadherent yeast cells and the occasional cell from the lung lavage that had not attached, and the attached cells were fixed with cold absolute methanol and stained with a 1:20 solution of Giemsa (Sigma). Phagocytic indices were determined with a microscope at a magnification of ×600 (Diaphot; Nikon Inc., Melville, N.Y.). Internalized organisms were distinguished from ones that were attached by their presence in vacuoles. In prior studies, we used Uvitex B dye (CIBA, Summit, N.J.) to confirm that we could distinguish attached organisms from internalized ones (14, 29, 30). The phagocytic index was defined as the number of macrophages that had internalized two or more yeast cells over the number of total macrophages per field. Eight fields were counted for each experiment.

The antifungal efficacies of primary macrophage cells were determined by counting the CFU of C. neoformans after coculturing yeast and macrophages in the presence and absence of MAb as described elsewhere (29). Briefly, C. neoformans was added to the macrophage in the presence or absence of 3 μg of MAb in 300 μl per well as described for the phagocytosis assay, and the mixtures were incubated for 24 h. The cells from each well were lysed with sterile water, and the total contents of each well were vigorously pipetted, diluted in PBS, and plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates. The amounts of antibody used did not have any direct effect on the growth of the organism. Artifactual decreases in CFU due to agglutination by antibody were avoided by using subagglutinating doses of antibody and mechanical disruption to disperse any clumps that may have formed (14, 29, 30).

Statistics.

Data were analyzed with statistical software for MacIntosh (Instat version 2.01; GraphPDA Software for Science, San Diego, Calif.) by the unpaired Student t test for CFUs. The alternative Weltch t test was used for animal survival studies. All results were also analyzed by the unpaired Wilcoxon test, which gave similar results (32).

RESULTS

Binding of isotype switch variants to GXM.

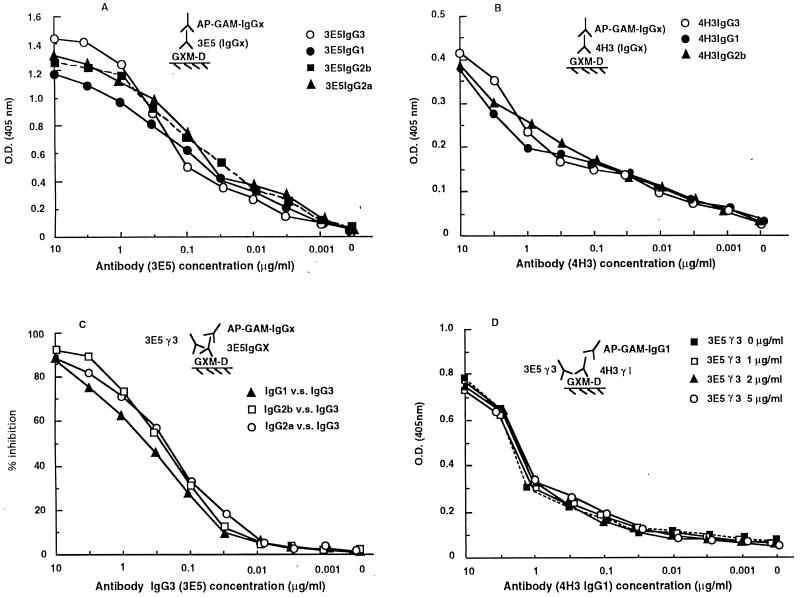

Generation of the IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b switch variants of MAb 3E5 and the IgG1 and IgG2b switch variants of MAb 4H3 has been described elsewhere (36, 42). Several ELISAs were used to test whether the switch variants had similar levels of antigen binding to the parental IgG3 MAbs. At low antibody concentrations, the IgG3 MAb 3E5 and its IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG2a switch variants bind to GXM in a similar fashion (Fig. 1A). However, at higher antibody concentrations, the IgG3 MAb produces higher absorbancy, in agreement with the ability of IgG3 subclass antibodies to bind more strongly as a result of polymerization after binding antigen (17). The 4H3 MAbs bound GXM less strongly than the 3E5 MAbs, and the 4H3 switch variants had similar antigen binding curves (Fig. 1B). Each of the switch variants of 3E5 competed with each other for binding, confirming that switching was not associated with a change in specificity (Fig. 1C). Hence, the levels of binding of each member of a family of switch variants to GXM were similar, as expected for antibodies which have the same antigen binding site but differ in isotype.

FIG. 1.

(A and B) ELISAs of 3E5 IgG (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3) and of 4H3 IgG (IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG3) MAb binding to GXM antigen, respectively; (C and D) competition assays. The details of each ELISA are described in Results and are diagrammed in the insert of each panel.

MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 have different epitope specificities.

In previous studies, we have shown that MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 have different reactivities with C. neoformans strains of the various serotypes, a finding that suggests differences in epitope specificities (28). To more rigorously investigate the epitope specificities of MAbs 3E5 and 4H3, we carried out competition experiments by ELISA. No competition was observed between MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 for binding GXM (Fig. 1D). The inabilities of MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 to inhibit each other in binding GXM confirm that these MAbs bind to different epitopes. Additional evidence for a difference in epitope specificity comes from peptide-binding studies, which show that peptides (37) that bind to the 3E5-binding site do not bind to 4H3. Hence, 3E5 and 4H3 bind to different epitopes on C. neoformans GXM.

Efficacy of protection by IgG3 MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 and their switch variants.

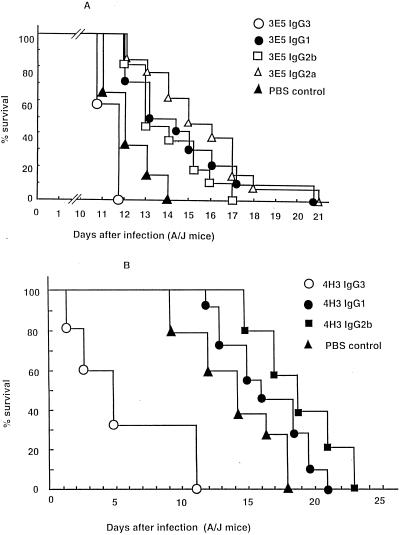

Administration of MAb 3E5 IgG3 to mice prior to i.v. infection did not prolong survival, in agreement with prior findings that this MAb was not protective against C. neoformans (42). Although there appeared to be a reduction in survival compared to controls (Fig. 2A), the difference was not significant (P = 0.05). In contrast, groups of mice given 3E5 IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG2a switch variants each lived significantly longer than the control group given PBS. Mice given 3E5 IgG2a lived longer than those given 3E5 IgG1, but this difference was not significant (P > 0.08). These results confirm prior experiments which show that isotype switching of 3E5 IgG3 to IgG1 converts a nonprotective antibody to a protective antibody (42) and demonstrate that the IgG2a and IgG2b variants of 3E5 can also mediate protection.

FIG. 2.

Survival of A/JCr mice infected with C. neoformans after the administration of IgG3 isotype switch variant MAbs. A dose of 1.0 mg of each antibody was given i.p. 24 h prior to i.v. challenge with 2 × 106 C. neoformans cells. (A) Average survival rates ± standard deviations for the 3E5 IgG3, IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG2a and PBS groups were 11.6 ± 0.5, 14.4 ± 2.6, 14.0 ± 1.7, 15.8 ± 2.6, and 12.1 ± 1.0 days, respectively. IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG2a MAbs prolonged animal survival significantly (P < 0.003), whereas the IgG3 MAbs showed a trend toward decreased survival that was not statistically significant (P > 0.18). (B) Average survival rates ± standard deviations for the 4H3 IgG3, IgG1, and IgG2b and PBS groups were 5.8 ± 3.8, 16.3 ± 3.2, 17.9 ± 2.8, and 14.1 ± 3.1 days, respectively. Administration of 4H3 IgG3 MAb reduced survival significantly (P < 0.0001). However, the 4H3 IgG1 switch variant showed no effects on survival (P > 0.14), and 4H3 IgG2b prolonged animal survival (P < 0.01).

Administration of MAb 4H3 prior to i.v. infection in A/JCr mice has been consistently shown to reduce survival relative to mice given saline alone (28). In the present study, administration of the 4H3 IgG3 MAb was again observed to reduce survival relative to the group receiving PBS (Fig. 2B). However, the 4H3 IgG1 switch variant neither reduced nor prolonged survival relative to PBS controls (P > 0.14), whereas the 4H3 IgG2b switch variant significantly prolonged animal survival relative to the group receiving PBS (P < 0.01; Fig. 2B).

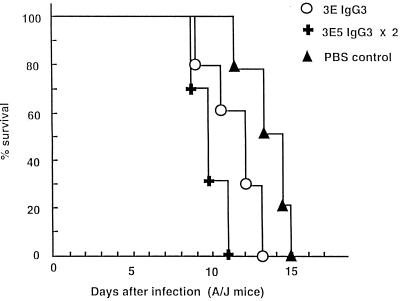

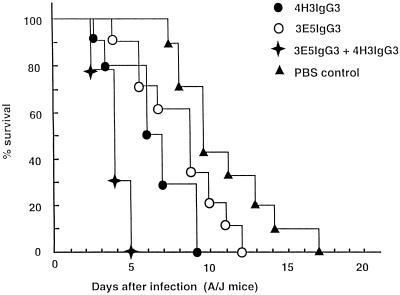

To investigate whether multiple injections of a nonprotective IgG3 MAb would have a different effect than a single injection, 1 mg of IgG3 MAb (3E5) was given 24 h prior to and 3 days after infection. Mice given two injections of IgG3 MAb had significantly reduced survival relative to those which received one dose (P < 0.002) (Fig. 3). To determine the effect of combined administration of the two different nonprotective IgG3 MAbs, mice were given either 1 mg of MAb 3E5 or 4H3 or 0.5 mg of both MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 before challenge with a lethal dose of C. neoformans. Figure 4 shows that mice treated with the combination of IgG3 MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 succumbed to infection faster than those which received either MAb alone. This experiment shows that combinations of nonprotective antibodies differing in epitope specificities can be more detrimental than either antibody alone.

FIG. 3.

Survival of A/JCr mice infected with C. neoformans after two administrations of the 3E5 IgG3 MAb. A dose of 1 mg of the 3E5 MAb was given i.p. 24 h prior to and 3 days after i.v. challenge with 2 × 106 C. neoformans cells. Average survival rates ± standard deviations for the groups given IgG3 once and twice and the PBS group were 11.5 ± 1.1, 9.0 ± 3.3, and 14.1 ± 1.2 days, respectively. Administration of two doses of IgG3 3E5 reduced survival relative to one dose (P < 0.002).

FIG. 4.

Survival of A/JCr mice infected with C. neoformans after administration of IgG3 MAbs 4H3 and 3E5. A dose of 0.5 mg of each antibody was given i.p. 24 h prior to i.v. challenge with 2 × 106 C. neoformans. Average survival rates ± standard deviations for the IgG3 (3E5), IgG3 (4H3), IgG3 (3E5 plus 4H3), and PBS groups were 8.4 ± 2.3, 6.6 ± 2.1, 4.1 ± 0.7, and 11.3 ± 2.6 days, respectively. Administration of IgG3 MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 significantly reduced survival (P < 0.004) compared to IgG3 3E5 or IgG3 4H3 treatment alone.

Macrophage experiments.

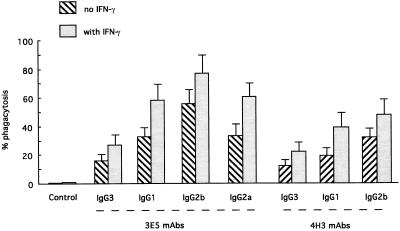

Primary lung macrophages from A/JCr mice were used to study the opsonic efficacies of 3E5 and 4H3 IgG3 MAbs and their switch variants. In the absence of antibody, there was little or no phagocytosis even if the macrophages were stimulated with IFN-γ (Fig. 5). All MAbs promoted phagocytosis, and phagocytosis was significantly greater in cells treated with IFN-γ. For both 3E5 and 4H3, the relative efficacy of the various subclasses in promoting phagocytosis was IgG2b > IgG1 > IgG3. To assess the relative efficacy of the 3E5 IgG3 MAb in enhancing macrophage antifungal activity against C. neoformans, CFUs were determined after 2 and 24 h of macrophage-yeast coculture in the presence or absence of 3E5 MAbs. Table 1 shows that IgG1-, IgG2a-, and IgG2b-mediated phagocytosis led to a decrease in CFU at 2 and 24 h compared to controls. In contrast, in the presence of IgG3 MAb, the number of C. neoformans cells increased after 24 h in culture compared to controls that lacked antibody (P < 0.006).

FIG. 5.

Effects of 3E5 and 4H3 MAb switch variants on phagocytosis by A/JCr bronchoalveolar macrophages in the presence or absence of IFN-γ. All MAbs promoted phagocytosis, and phagocytosis was significantly greater in cells treated with IFN-γ (P < 0.01).

TABLE 1.

Effects of 3E5 IgG MAbs on CFU of C. neoformans after coculture with bronchoalveolar macrophages for 2 or 24 h

| Treatment group | Mean CFU ± SD (103) (P) after coculture for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 2 h | 24 h | |

| IgG1 | 13 ± 3 (0.01a) | 189 ± 13 (0.0001a) |

| IgG2a | 12 ± 2 (0.006a) | 178 ± 21 (0.0001a) |

| IgG2b | 13 ± 3 (0.01a) | 201 ± 27 (0.0001a) |

| IgG3 | 21 ± 5 (0.6b) | 286 ± 20 (0.006b) |

| Control (no MAbs) | 19 ± 4 (0.02c) | 244 ± 22 (0.0005c) |

| Control (no MAbs, no macrophages) | 23 ± 3 (0.13d) | 281 ± 26 (0.03d) |

IgG1-, or IgG2a-, or IgG2b-treated groups versus IgG3-treated groups.

IgG3-treated groups versus controls (no MAbs).

IG3-treated groups versus controls (no MAbs; only macrophages and C. neoformans).

Controls (no macrophages and no MAbs; only C. neoformans) versus control (no MAbs).

DISCUSSION

The specificities of antibody isotype and epitope have previously been shown to be important determinants of the efficacy of antibodies against C. neoformans (28). The importance of the isotype was first suggested by Kozel and collaborators, who showed that IgG2a and IgG2b isotype switch variants of MAb 471 differed in their abilities to reduce organ fungal burden in murine experimental infections (33). The IgG isotype variants also differed in their abilities to promote phagocytosis, with the relative efficacy being IgG2b > IgG2a > IgG1 (33). Mukherjee et al. subsequently demonstrated differences among IgM, IgG1, IgG3, and IgA MAbs (28). Most striking was the fact that IgG3 MAbs did not protect against C. neoformans infection despite the ability of this class to protect against other encapsulated pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (1). Isotype switching of 3E5 IgG3 to IgG1 converted a nonprotective antibody into a protective antibody (42), providing unequivocal evidence for the importance of isotype in antibody-mediated protection against C. neoformans. IgG3 MAbs were subsequently shown to function as blocking antibodies in cryptococcal infections, with the potential to either enhance infection or reduce the efficacy of protective MAbs, depending on the experimental conditions (32). Evidence for specificity as a critical determinant of efficacy against C. neoformans was obtained by comparison of IgM MAbs which differ in their locations of capsular binding. For another fungus, Candida albicans, the efficacy of antibody protection has been shown to depend on epitope specificity (19). Hence, both isotype and specificity are known to contribute to the efficacy of protection, but their relative contributions and mechanisms of action remain obscure.

In this study, we analyzed two families of isotype switch variants derived from the 3E5 and 4H3 nonprotective IgG3 MAbs. MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 differ in heavy- and light-chain variable gene usage. MAb 3E5 is a member of group II anticryptococcal MAbs, which include many protective MAbs, and is assembled from VH441, JH3, V lamda 1, and J lambda 1 gene elements (3). MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 did not compete for binding to capsular polysaccharide and hence must bind to different epitopes. The switch variants reacted with capsular polysaccharide in a manner similar to that of each parental IgG3 MAb, in agreement with the identical epitope specificities expected for isotype switch variants.

In all experiments with immunocompetent mice, the two IgG3 MAbs were either not protective or enhanced infection. Additional evidence for the deleterious effects of this isotype in cryptococcal infection was obtained by showing that two doses of MAb 3E5 shortened survival more than a single dose. Furthermore, the combination of the two IgG3 MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 shortened survival more than either antibody alone. The inability of IgG3 MAbs to mediate protection is intriguing when one considers that IgG3 class antibodies tend to be elicited by type 2 T-cell-independent antigens such as cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide. Hence, it appears that the IgG subclass most likely to be elicited by the capsular polysaccharide antigen is also the least protective. However, it is interesting that a GXM-TT vaccine primarily elicits IgG1 antibodies to GXM (3) and that antibody response is protective (8). Isotype switch variants of both 3E5 and 4H3 IgG3 MAbs were significantly more effective at prolonging survival than the parental IgG3 MAbs. For MAb 3E5, the IgG1 switch variant has previously been shown to be protective (42). Here, the IgG2a and IgG2b switch variants have also been shown to be protective. For MAb 4H3, the IgG1 switch variant was previously shown to be nonprotective (32). Here, the 4H3 IgG2b switch variant is shown to prolong survival, demonstrating that the efficacy of protection of an IgG1 MAb can be increased by subsequent isotype switching to downstream isotypes. This result shows that conclusions regarding the protective potential of antibodies against a given epitope cannot be made from studies with one or even two isotypes.

The relative efficacy of protection of the 3E5 isotype switch family differed from that observed with isotype variants from the IgM MAb 2D10, which followed the order IgG2a > IgG1 > IgG2b (30). In contrast, the relative efficacy of protection of the 3E5 switch family closely paralleled that observed by Schlageter and Kozel (34) with isotype variants of MAb 471, which followed the order IgG2a > IgG2b > IgG1. Furthermore, for 4H3 the efficacy of IgG2b was greater than that of IgG1. MAbs 3E5, 2D10, and 471 are similar to each other but have amino acid differences in their variable regions which may contribute to differences in fine specificity. In this regard, epitope mapping with phage peptide libraries has shown differences between the 3E5 and 2D10 binding sites (37). As demonstrated here, MAb 4H3 clearly binds to a different epitope than does MAb 3E5. Hence, these results suggest that isotype efficacy varies, depending on the specificity of the antibody in question.

All of the IgG classes were opsonic for C. neoformans with bronchoalveolar macrophages. Treatment of bronchoalveolar macrophages with IFN-γ enhanced phagocytosis for all isotypes. This phenomenon may reflect the ability of IFN-γ to increase Fc receptor expression. For both MAbs 3E5 and 4H3, the relative opsonic efficacy for C. neoformans ingestion by mouse bronchoalveolar macrophages was greater for IgG2b and IgG1 than that for IgG3. The opsonic efficacies of the various isotype switch variants of MAbs 3E5 and 4H3 are different from those observed by Schlageter and Kozel (34), who found a relative efficacy of IgG2a > IgG2b > IgG1 for isotype switch variants of MAb 471. Furthermore, this result differs from that of Mukherjee et al. (29), who found the relative efficacy for isotype switch variants of the IgM antibody 2D10 to be IgG1 > IgG2a > Ig2b. Opsonic efficacy is likely to reflect antibody affinity for antigen, surface epitope density on the target cell, and Fc receptor density on the effector cell. These differences may reflect variation in epitope specificity or experimental differences, given the use of different macrophages and C. neoformans strains. For example, Schlageter and Kozel used a serotype A strain with peritoneal macrophages (34), Mukherjee et al. used a serotype D strain with J774.16 cells (30), and the present study used a serotype D strain with bronchoalveolar macrophages. In any case, all IgG subclasses are opsonic for C. neoformans, and it is unclear if the minor differences observed among switch variants of the different MAbs are biologically relevant, given that both protective and nonprotective antibodies were opsonic.

Previous studies have shown that IgG-type MAbs can enhance the antifungal efficacies of murine J774.16 cells (29, 30) and alveolar macrophages (14). However, none of the prior studies has demonstrated qualitative differences between protective and nonprotective MAbs in vitro. In this study, we found that IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b MAbs reduced CFUs when they were added to mixtures of IFN-γ-stimulated alveolar cells and C. neoformans. In contrast, the 3E5 IgG3 MAb was not effective in promoting reduction in CFUs at either 2 or 24 h. This result is different from that observed with IFN-γ- and LPS-stimulated J774.16 cells, in which all of the IgG subclasses, including IgG3, were found to enhance the antifungal efficacy of the macrophage-like cells (30). Presumably, the differences in experimental results reflect differences in the use of primary macrophage cells versus an immortal macrophage-like cell line. This observation suggests that primary macrophage cells may provide a useful system for dissecting MAb isotype differences in vitro. In any case, the findings in this study imply that the interaction of IgG3 with C. neoformans and macrophages is different from that of the other isotypes and suggest a plausible explanation for the lack of efficacy of this IgG subclass.

In summary, the experience with MAb 4H3 indicates that one cannot conclude that an epitope elicits nonprotective antibodies solely on the basis of MAbs of one or two isotypes to that epitope. The results suggest that to make definitive conclusions about the potential of a given epitope to generate protective or nonprotective antibodies, one must evaluate several, if not all, isotype variants of a MAb with that epitope specificity. Protective antibodies can be made more protective by switching their constant regions to other isotypes. The contributions of isotype and epitope specificities to the efficacy of protection appear to be interdependent and provide yet another layer of complexity to the structure-function relationship of anticryptococcal antibodies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA39838 to M.D.S. and AI22774 and AI13342 to A.C.), a Burroughs Welcome Developmental Therapeutics award to A.C., a fellowship from the Aaron Diamond Foundation to R.R.Y., a grant from the U.S. Israel Binational Foundation to G.S., and the Harry Eagle Chair from the Women’s Division of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine to M.D.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Briles D E, Claflin J L, Schroer K, Forman C. Mouse IgG3 antibodies are highly protective against infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nature. 1981;294:88–90. doi: 10.1038/294088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casadevall A. Antibody immunity and invasive fungal infections. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4211–4218. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4211-4218.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casadevall A, Mukherjee J, Devi S J N, Schneerson R, Robbins J B, Scharff M D. Antibodies elicited by a Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine have the same specificity as those elicited in infection. J Infect Dis. 1992;65:1086–1093. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.6.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caulay L K, Murphy J W. Response of congenitally athymic (nude) and phenotypically normal mice to Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Infect Immun. 1979;23:644–651. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.3.644-651.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang Y C, Kwon-Chung K J. Complementation of a capsule-deficient mutation of Cryptococcus neoformans restores its virulence. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4912–4919. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherniak R, Sundstrom J B. Polysaccharide antigens of the capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1507–1512. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1507-1512.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Currie B P, Casadevall A. Estimation of the prevalence of cryptococcal infection among HIV infected individuals in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:1029–1033. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.6.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devi S J N. Preclinical efficacy of a glucuronoxylomannan-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine of Cryptococcus neoformans in a murine model. Vaccine. 1996;14:841–842. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00256-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devi S J N, Schneerson R, Egan W, Ulrich T J, Bryla D, Robbins J B, Bennett J E. Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A glucuronoxylomannan-protein conjugate vaccines: synthesis, characterization, and immunogenicity. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3700–3707. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3700-3707.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong Z M, Murphy J W. Effects of the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans cells and culture filtrate antigens on neutrophil locomotion. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2632–2644. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2632-2644.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong Z M, Murphy J W. Cryptococcal polysaccharides induce L-selectin shedding and tumor necrosis receptor loss from the surface of human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:689–698. doi: 10.1172/JCI118466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dromer F, Charreire J, Contrepois A, Carbon C, Yeni P. Protection of mice against experimental cryptococcosis by anti-Cryptococcus neoformans monoclonal antibody. Infect Immun. 1987;55:749–752. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.3.749-752.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckert T F, Kozel T R. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific for Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1895–1899. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1895-1899.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldmesser M, Casadevall A. Effect of serum IgG1 against murine pulmonary infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 1997;158:790–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman D, Lee S C, Casadevall A. Proceedings of the 34th International Conference of Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Orlando, Fla. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. Pharmacokinetics of cryptococcal polysaccharide clearance. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graybill J R, Hague M, Drutz D LT. Passive immunization in murine cryptococcosis. Sabouraudia. 1981;19:237–244. doi: 10.1080/00362178185380411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenspan N S, Dacek D A, Cooper L J. Fc region-dependence of IgG3 anti-streptococcal group A carbohydrate antibody functional affinity. I. The effect of temperature. J Immunol. 1988;141:4276–4282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin F M. Roles of macrophage Fc and C3b receptors in phagocytosis of immunologically coated Cryptococcus neoformans, Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;78:3853–3857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han Y, Cutler J E. Antibody response that protects against disseminated candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2714–2719. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2714-2719.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huffnagle G B, Yates J L, Lipscomb M F. Immunity to pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection requires both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1991;173:793–800. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozel T R, Pfrommer G S T, Guerlain A S, Highison B A, Highison G J. Role of the capsule in phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:S436–S439. doi: 10.1093/cid/10.supplement_2.s436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levitz S M. The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans and the epidemiology of cryptococcosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:1163–1169. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.6.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levitz S M, Farrell T P, Maziarz R T. Killing of Cryptococcus neoformans by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated in culture. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1108–1113. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.5.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levitz S M, Tabumi A, Kornfeld H, Reardon C C, Goleabock D T. Production of tumor necrosis factor alpha in human leukocytes stimulated by Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1975–1981. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1975-1981.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell T G, Perfect J R. Cryptococcosis in the era of AIDS—100 years after the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:515–548. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mody C H, Lipscomb M F, Street N E, Toews G B. Depletion of CD4+ (L3T4+) lymphocytes in vivo impairs murine host defense to Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 1990;144:1472–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mozaffarian N, Berman T W, Casadevall A. Immune complexes increase nitric oxide production by interferon-gamma-stimulated murine macrophage-like J774.16 cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:657–662. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukherjee J, Scharff M D, Casadevall A. Protective murine monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4534–4541. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4534-4541.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherjee S, Feldmesser M, Casadevall A. J774 Murine macrophage-like cell interactions with Cryptococcus neoformans in the presence and absence of opsonins. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1222–1231. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.5.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherjee S, Lee S C, Casadevall A. Antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan enhance antifungal activity of murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:573–579. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.573-579.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy J A. Mechanisms of natural resistance to human pathogenic fungi. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:509–538. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.002453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nussbaum G, Yuan R, Casadevall A, Scharff M D. Immunoglobulin G3 blocking antibodies to the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1905–1909. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanford J E, Lupan D M, Schlagetter A M, Kozel T R. Passive immunization against Cryptococcus neoformans with an isotype-switch family of monoclonal antibodies reactive with cryptococcal polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1919–1923. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1919-1923.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlageter A M, Kozel T R. Opsonization of Cryptococcus neoformans by a family of isotype-switch variant antibodies specific for the capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1914–1918. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1914-1918.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spira G, Scharff M D. Identification of rare immunoglobulin switch variants using the ELISA spot assay. J Immunol Methods. 1992;148:121–129. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90165-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spira G, Yuan R, Paizi M, Weisendal M, Casadevall A. Simultaneous expression of kappa and lambda light chains in a murine IgG3 anti-Cryptococcus neoformans hybridoma cell line. Hybridoma. 1994;13:531–535. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1994.13.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valadon P, Nussbaum G, Boyd L F, Margulies D H, Scharff M D. Peptide libraries define the fine specificity of anti-polysaccharide antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:11–22. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vazcquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Balish E. Peroxynitrite contributes to the candidacidal activity of nitric oxide-producing macrophages. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3127–3133. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3127-3133.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vecchiarelli A, Pietrella D, Dottorini M, Monari C, Retini C, Todisco T. Encapsulation of Cryptococcus neoformans regulates fungicidal activity and the antigen presentation process in human alveolar macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;98:217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vecchiarelli A, Retini C, Monari C, Tascini C, Bistoni F, Kozel T R. Purified capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans induces interleukin-10 secretion by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2846–2849. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2846-2849.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vecchiarelli A, Retini C, Pietrella D, Monari C, Tascini C, Beacari T, Kozel T R. Downregulation by cryptococcal polysaccharide of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 beta secretion from human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2919–2923. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2919-2923.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan R, Casadevall A, Spira G, Scharff M D. Isotype switching from IgG3 to IgG1 converts a nonprotective murine antibody to Cryptococcus neoformans into a protective antibody. J Immunol. 1995;154:1810–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan R R, Casadevall A, Oh J, Scharff M D. T cells cooperate with passive antibody to modify Cryptococcus neoformans infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2483–2488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhong Z, Pirofski L. Opsonization of Cryptococcus neoformans by human anticryptococcal glucuronoxylomannan antibodies. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3446–3450. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3446-3450.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zuger A, Louie E, Holzman R S, Simberkoff M S, Rahal J L. Cryptococcal disease in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: diagnostic features and outcome of treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:234–240. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-2-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]