Abstract

Objectives:

To synthesize published research exploring emergency department (ED) communication strategies and decision-making with persons living with dementia (PLWD) and their care partners as the basis for a multistakeholder consensus conference to prioritize future research.

Design:

Systematic scoping review.

Settings and Participants:

PLWD and their care partners in the ED setting.

Methods:

Informed by 2 Patient-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome (PICO) questions, we conducted systematic electronic searches of medical research databases for relevant publications following standardized methodological guidelines. The results were presented to interdisciplinary stakeholders, including dementia researchers, clinicians, PLWD, care partners, and advocacy organizations. The PICO questions included: How does communication differ for PLWD compared with persons without dementia? Are there specific communication strategies that improve the outcomes of ED care? Future research areas were prioritized.

Results:

From 5451 studies identified for PICO-1, 21 were abstracted. From 2687 studies identified for PICO-2, 3 were abstracted. None of the included studies directly evaluated communication differences between PLWD and other populations, nor the effectiveness of specific communication strategies. General themes emerging from the scoping review included perceptions by PLWD/care partners of rushed ED communication, often exacerbated by inconsistent messages between providers. Care partners consistently reported limited engagement in medical decision-making. In order, the research priorities identified included: (1) Barriers/facilitators of effective communication; (2) valid outcome measures of effective communication; (3) best practices for care partner engagement; (4) defining how individual-, provider-, and system-level factors influence communication; and (5) understanding how each member of ED team can ensure high-quality communication.

Conclusions and Implications:

Research exploring ED communication with PLWD is sparse and does not directly evaluate specific communication strategies. Defining barriers and facilitators of effective communication was the highest-ranked research priority, followed by validating outcome measures associated with improved information exchange.

Keywords: Dementia, emergency medicine, communication, decision making, patient participation

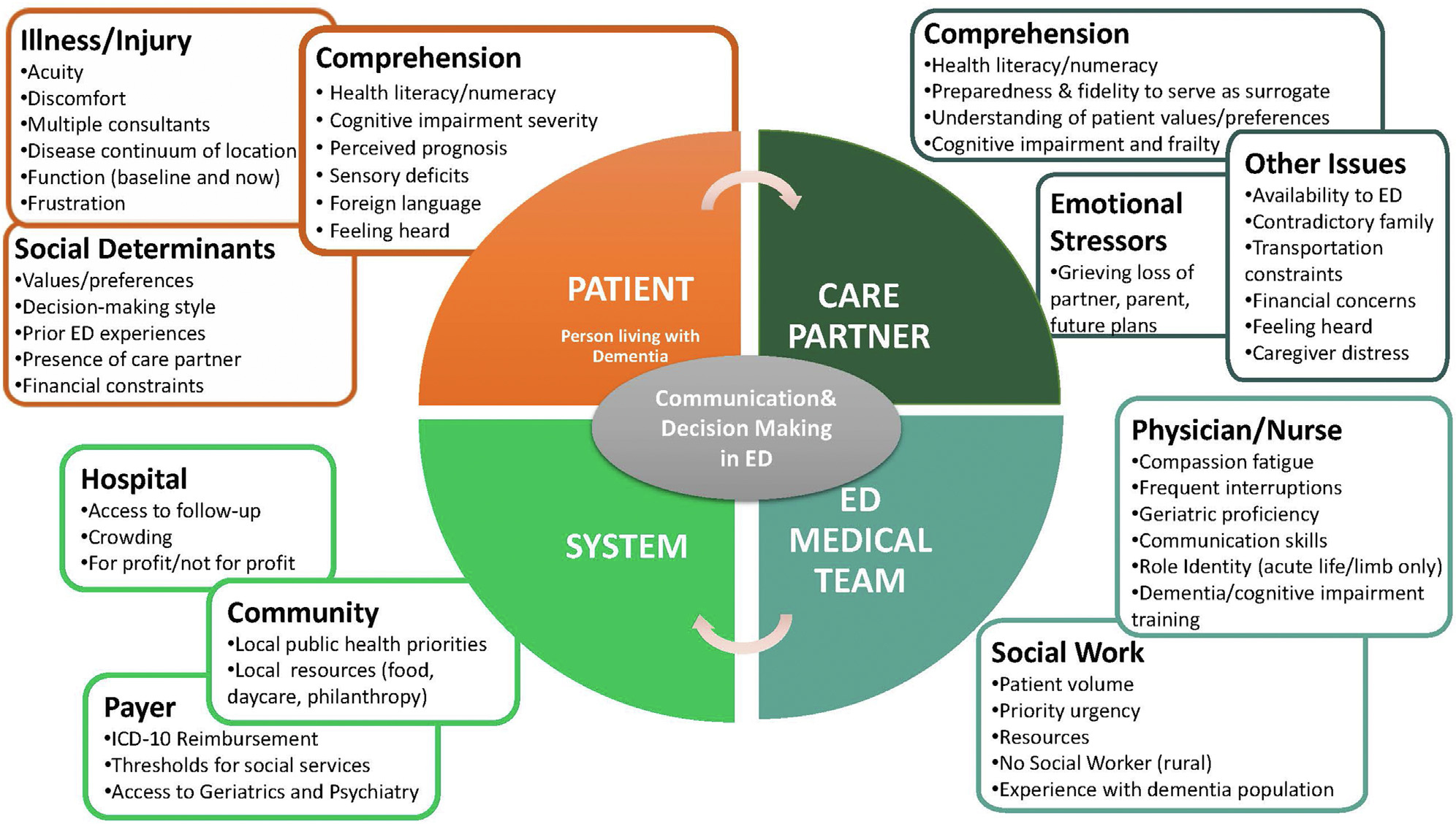

Conveying medical information and weighing various diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in the emergency department (ED) is difficult for all aging adults. As depicted in Figure 1, the process of medical communications is complicated by the distractions of an often chaotic environment, diagnostic uncertainties amidst an evolving stream of laboratory and imaging data, patient and family emotions associated with acute illness or injury, and health literacy among many other contextual and interprofessional factors.1 In ED populations without dementia, communication is imperfect with incomplete recollection of test results, presumptive diagnoses, prescriptions, and follow-up recommendations.2,3 Approximately 75% of a patient’s ED time is spent not interacting with healthcare teams, and older adults identify poor communication as a problematic aspect of emergency care.4–7 Communication strategies striving to improve ED nurse/physician-to-patient information exchange such as TeachBack are inconsistently effective in nondementia populations and untested in subsets with dementia and their care partners.8 Increasingly, healthcare disparities associated with dementia are acknowledged.9 For example, limited health literacy is a source of healthcare disparity, interacts with the severity of dementia, is a communication barrier, and yet is not routinely evaluated in ED settings.10,11 Shared Decision Making (SDM) is an evolving approach to engage patients and families of all health literacy levels in complex medical conversations, but emergency medicine research often excludes individuals with dementia.12–14 Amidst layers of communication complexity, recognized dementia is independently associated with ED returns within 1-month, so improving communication strategies may improve operational efficiencies and patient satisfaction.15,16

Fig. 1.

Multi-level Complexities of Emergency Department Cmunication and Decision-Making with Persons Living with Dementia.

ED-based observational studies using validated cognitive screening instruments suggest a dementia prevalence ranging from 12% to 43% with a weighted mean prevalence of 31%.17 The Geriatric Emergency care Applied Research 2.0-Advancing Dementia Care (GEAR 2.0-ADC) Network is an interdisciplinary group of dementia researchers, clinicians, patients, and care partners focused on 4 components of ED dementia care: communication/decision-making, detection, best practices, and care transitions.18 The primary objective of this manuscript was to prioritize research questions for ED communication/decision-making with persons living with dementia (PLWD) and/or their care partners. A secondary objective was to describe the current state of reporting around health disparities in the ED communication/decision-making published research.

Methods

Study Design

This study was designed to select and prioritize the research questions for ED communication/decision-making with PLWD and their care partners. Based on recommendations from the 2017 Dementia Care Summit, we use the term care partner to denote both traditional caregivers and other engaged individuals sharing a reciprocal relationship with PLWD.19 We conducted a scoping review of articles related to communication and decision-making involving PLWD and their care partners in the ED. The scoping review was subsequently used for Consensus Conference stakeholders to prioritize future research questions exploring ED communication for PLWD and their care partners. Our protocol was registered with Open Science Framework Registries (Registration DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/VXPRS) and adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guidelines.20

Search Strategy

In collaboration with a medical librarian in partnership with several librarians and project team members from the GEAR 2.0-ADC Task Force, a comprehensive search of the literature was created. All searches were performed in March 2021. The search was adapted from a GEAR 2.0-ADC Task Force baseline search to fit the needs of the specific project question and translated for the following databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase (Embase.com), CINAHL (Ebsco), PsycINFO (Ebsco), PubMed Central, Web of Science (Clarivate), and Proquest Global Theses and Dissertations. Full details of the search terms are provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Study Selection and Abstraction

A priori exclusion criteria for individual articles included non-ED settings, failure to evaluate communication or decision-making strategies, lack of inclusion of PLWD or suspected dementia, no comparison of strategies between patients with dementia and patients without dementia, or lack of original research data. During the first phase of screening, 2 authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts identified from the search strategy for both Patient-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome (PICO) questions for inclusion using Covidence. In the second phase, the same 2 authors independently reviewed the full text documents for inclusion. Unpublished abstracts presented at scientific meetings were not included. No publication date or language exclusions were applied. Unweighted Cohen kappa was used to quantify interrater agreement. Another author adjudicated any disagreements.

Data abstraction forms were developed, tested, and refined. Data extracted from each individual study was summarized in standardized tables. Two authors independently abstracted study setting and timeframe, inclusion/exclusion criteria, study design, primary outcomes, health equity factors reported, communication-related outcomes, and study limitations.

Results

GEAR 2.0-ADC participants were identified by their active membership in geriatric emergency medicine interest groups with the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, Gerontological Society of America, and Alzheimer’s Association, as well as prior publications in the domains of geriatric emergency medicine and cognitive dysfunction. The GEAR 2.0-ADC Communication/Decision-making Work Group included 6 emergency medicine physicians, a geriatrician, 1 nurse, 2 social workers, a pharmacist, 1 care partner, 2 PLWD, and a research coordinator. The Work Group participated in monthly teleconferences to derive pertinent PICO questions, prioritize those PICO questions, derive a reproducible search strategy, independently filter the results of the electronic search, abstract key results from the original studies that met inclusion criteria, and synthesize the research findings into best practices and knowledge gaps.

PICO Questions

The GEAR 2.0-ADC Communication/Decision-Making Work Group derived and refined 16 potential key questions summarized in Table 1. The 53 members of the GEAR 2.0-ADC Task Force then prioritized these questions by an online survey. PICO questions were developed based on these stem questions and are described in Supplementary Material 1.

How does “communication and decision-making” differ for persons with dementia compared with persons without dementia?

Are there specific medical communication strategies (such as “Teach Back” or next day telephone follow-up) that improve the process or outcomes of ED care in persons with dementia?

Table 1.

GEAR 2.0-ADC Communication and Decision-Making Questions Developed

| 1. What are the modifiable barriers to effective communication or facilitators of effective communication with persons living with dementia (or their care partners) during an episode of ED care? |

| 2. What dementia severity threshold (if any) should trigger engagement of care partner in ED decision-making? |

| 3. Do ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic factors (patient characteristics) or unconscious biases (provider factors) influence communication for ED patients living with dementia (or their care partners)? |

| 4. In the ED that includes social work, nurses, physicians, technicians, case managers and pharmacists, who is best suited to provide medical communication to patients with dementia (or their care partners)? |

| 5. Who are the essential participants in the stream of ED communication with patients with dementia (or their care partners)? |

| 6. What are the most accurate and reliable measures or outcomes of “effective communication” in patients with dementia? |

| 7. What outcome measures are associated with “ineffective communication” for patients with dementia? |

| 8. What are the essential elements of information to communicate to persons with dementia during an episode of ED care? |

| 9. When during an episode of ED care is communication most safe, effective, and efficient for persons with dementia and their care partners? |

| 10. What unintended consequences or harms are associated with attempts to adapt communication between ED healthcare providers and persons with dementia (and the remainder of the ED patient population)? |

| 11. What are the costs of inadequate dementia communication strategies? |

| 12. How and when should the communication strategy adjust based on dementia severity and presenting illness acuity/severity? |

| 13. How does the ED team identify a dementia patient’s preferred “care partner” for communication? |

| 14. How does ED infrastructure and resources support communication with dementia patients and their care partners? |

| 15. Which communication strategies are worth evaluating in ED settings (Teach Back, healthcare coaching, etc.)? |

| 16. What non-verbal signs (like anxiety) can ED providers recognize to identify inadequate communication during an episode of care? |

PICO-1: Communication Differences Between Patients with Dementia and Patients without Dementia/Care Partners

The literature search identified 145 manuscripts and abstracts for full-text review, with 21 ultimately meeting inclusion criteria after adjudication. The interrater agreement for inclusion or exclusion during the initial screening of abstracts and titles was poor (κ = 0.16) and did not improve during the full-text reviews (κ = 0). Most disagreements revolved around whether a communication strategy was being evaluated or described comparatively between dementia and non-dementia populations. Supplementary Material 2 provides details of the inclusion and exclusion decisions, and Table 2 summarizes the included studies.

Table 2.

PICO-1 Evidentiary Table: Dementia/Nondementia Differences

| Study, Location, Timeframe | No. patients (Median or Mean Age) | Inclusion Criteria/Exclusion Criteria | Study Design | Factors Assessed or Primary Outcome | Healthcare Equity Factors Assessed or Reported | Prevalence of Communication-Related Outcomes | Comments and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Baraff 1992, older adult (≥65 y) focus groups in Boston, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Youngstown, and Norwalk, unreported period of time | The number of participants per group ranged from 5 to 13, but neither the total number nor the mean age of participants were reported | Participating older adults identified by ED logs or by contacting senior citizen groups and centers. One or two family members were also included in each group. Participants were not paid No exclusion criteria reported |

Qualitative focus group with 1–2 moderators per group and tape-recorded sessions using open-ended questions. Moderators were mostly emergency physicians or clinical social workers. | Factors for which focus group participant commentary sought included quality of medical care, time in ED, staff interactions, patient anxiety, clinical care environment, knowledge of emergency care, transportation, billing, and “fears of the elderly”. | None | • Participants reported “The staff do not listen” • ED staff are too rushed and “...we need a little time. Because our thoughts do not always come as quickly as we’d like, and we speak and sometimes we might forget some of the things we might say...” |

• Early qualitative research without quantitative or comparative reporting • No assessment of dementia/nondementia communication differences |

| Benjenk 2020, older adults recruited from 3 academic medical center EDs from Madison, WI (1) or Rochester, New York (2) | 699 eligible for analysis in at least 1 of 3 care transition pillars mean age not reported but ages 60–64 y (23%), 65–69 y (26%), 70–74 y (18%), 75–79 y (13%), 80–84 y (11%), ≥85 y (9%) | Age ≥ 60, English-speaking, primary care physician within the recruiting ED healthcare system, community-dwelling, working phone. Excluded if admitted, in ED > 24 h, discharged to hospice or long-term care, homeless, involved with transitional care team, or behavioral health visit. |

Secondary analysis of data collected from control arm of randomized controlled trial assessing ED-to-home care transition intervention. Research assistants surveyed patients in ED and 4 d after ED discharge. The presence/absence of cognitive impairment was assessed with the Short Blessed Test (>10 threshold for abnormal). Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression modeling reported to identify independent factors associated with adherence |

Care transition management pillars assessed: medication self-management; primary care/specialist follow-up; knowledge of “red flags”. | 92.5% of enrollees were white, 46% male, 32.5% lived alone, 39% had less than college education, and 10.6% had inadequate health literacy. | • Higher proportions of cognitive impairment noted with medication nonadherence (22% nonadherent had cognitive impairment vs 16% adherent), follow-up nonadherent (25% vs 17%), and inadequate knowledge of red flags (22% vs 12%). • Bivariate regression analyses demonstrated no independent association between cognitive impairment and medication or follow-up adherence, or knowledge of red flags (aOR 1.16, 95% CI 0.69–1.95). |

• Results are not stratified by presence/absence of cognitive impairment. • No specific communication strategy was evaluated. • None of the factors assessed were independently associated with medication adherence. • Only poor health status was independently associated with follow-up adherence. • Older age, depressive symptoms, and having ≥1 functional limitation associated with less knowledge of red flags. • Health equity factors (race, sex, health literacy) not independently associated with adherence to any of the 3 pillars. |

| Cooper 2016, panel synthesis of best communication practices to facilitate goal concordant care in seriously ill older patients with surgical emergencies | Interdisciplinary panel of 23 national leaders in acute care: [surgery (5), general surgery (1), vascular surgery (1), surgical oncology (3), palliative medicine (5), critical care (4), emergency medicine (2), anesthesia (1), and health care innovation (2)] | No inclusion or exclusion criteria since no patient-individuals | 1-d conference at Harvard Medical School led by a professional moderator to explore the concept, content, format, and usability of a communication framework. Participants evaluated communication between the resident, patient, and surrogate from 3 perspectives—surgeon, surrogate, and patient—in small groups to share their expertise and outline strengths and weaknesses of the conversation. |

9 key elements of a framework: (1) formulating prognosis; (2) creating a personal connection; (3) disclosing information regarding the acute problem in the context of the underlying illness; (4) establishing a shared understanding of the patient’s condition; (5) allowing silence and dealing with emotion; (6) describing surgical and palliative treatment options; (7) eliciting patient’s goals and priorities; (8) making a treatment recommendation; and (9) affirming ongoing support for the patient and family. | None | • The advisory panel recommendations included (1) a delineation of the key elements of a communication framework, and (2) identification of core communication techniques that should run through the entire surgeon—patient conversation. | • Barriers to shared decision making identified including symptom severity, inadequate decisional capacity and care partner preparedness to serve as surrogate decision-maker. • No strategies for enhancing communication with dementia patients evaluated or summarized. |

| Dunnion 2008, purposeful sampling survey of medical and nursing staff at single ED at a regional hospital and the surrounding primary care area in Ireland exploring documentation issues when discharged older adults home from the ED | 222 medical and nursing staff in the ED primary care area. Surveys distributed to all grades of qualified nurses (clinical nurse managers, staff nurses) (n = 27) and all grades of medical staff (consultants, registrars, senior house officers) (n = 34) in ED; all public health nurses (n = 59), all practice nurses (n = 34) and general practitioners (n = 68) in the primary care area. | Some members of the primary care team were excluded | Exploratory descriptive design Two precoded questionnaires were constructed, one for administration to ED staff and the other to primary care staff in a number of settings |

None | Responses from 135 of those surveyed. The primary care sector respondents included: public health nurses: n = 55; general practitioners: n = 32 and practice nurses: n = 18. Respondents from the ED included 11 doctors from various grades (intern, senior house officer, registrar and consultant) and 19 nurses from various grades (staff nurse, clinical nurse manager 2 & 3). | Current communication between ED and the primary care professionals is disjointed. There is a need to develop an effective referral criteria, accurate documentation and prompt referrals. |

• Neither the survey nor the responses highlight unique communication barriers of persons with dementia or comparisons with non-dementia populations. • ED documentation appears to be handwritten scribble on “cards” which may have limited applicability in sites with contemporary electronic medical records. |

| Gettel 2019, chart review exploring the completeness of NH transfer documentation according to expected core components against the INTERACT 4.0 quality improvement tool in 3 of Rhode Island’s (RI) largest EDs from September 2015 to September 2016. | 474 NH-to-ED transfers to 1 of 3 EDs, mean patient age 76 y | Eligible for inclusion if they were 18 or older, residing at a NH within RI, and had been transferred to one of the 3 EDs within the given time frame. Exclusions included patients transferred from assisted living, retirement communities, or independent living communities as well as patients transferred to another hospital after their ED visit and patients who left before care was complete. |

Retrospective study using two abstractors blinded to the study aims. Study data were abstracted from the EHR. The EHR contained the record of the ED visit and NH-ED transfer documentation. |

NH-ED transfer documents were present for 97% of visits, and an average 11.9 of 15 INTERACT core items were complete. Usual mental status and reason for transfer were absent for 75% of patients, whereas functional status was absent for 80%. The multivariable model showed that a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score (coefficient 0.08, standard error 0.04, P = .03) was associated with more complete documentation. | 43% were male, 14% were nonwhite, and 34% had dementia. | • 34% of patients known to have dementia. • Usual mental status was missing for 72% of patients and 23% of patients for whom the EHR listed dementia as a diagnosis did not list dementia in the NH-ED transfer documentation. • Compared with those without dementia, study participants with dementia had higher Charlson Comobidity Index and were older, but had similar 72-h revisit rates and 30-d unplanned readmissions and were less likely to be admitted (63% vs 73%, P = .04) |

• Analysis included ED visits of a large health system in 1 state—results may not be generalizable to other states and healthcare systems. • Additional transfer paperwork may not be included in the EHR if lost in the ambulance or at the receiving ED and not uploaded. • It was beyond the scope of this work to categorize patient’s chief complaints as requiring admission or not |

| Gettel 2020, characterize patient- and caregiver-specific perspectives about care transitions after a fall in two different Rhode Island EDs: an academic community hospital and a Level 1 trauma center within the same health system from June 2018 to January 2019. | A total of 22 interviews were completed with 10 patients, 8 caregivers, and 4 patient/caregiver dyads within 6-mo after the initial ED visit, patient average age 83 y | Patients age ≥65 y who presented to ED within 7 d of a fall, if they primarily spoke English or Spanish, and if their ED clinician determined they were likely to be discharged from the ED. Also included patients enrolled in the Geriatric Acute and Post-acute Fall Prevention Intervention trial. |

A semistructured interview guide was developed based on prior qualitative research on falls and the expertise of the study authors. One interview guide was tailored to the patient and another to the caregiver. Domains assessed included the post fall recovery period, the SNF placement decision-making process, and the ease of obtaining outpatient follow-up. Presence/absence of cognitive impairment assessed using Six Item Screener with <4 considered abnormal Interviews lasted a mean of 43 min, with a range of 14 to 109 min. |

Four main themes identified: (1) the fall as a trigger for psychological and physiological changes, (2) SNF placement decision-making process, (3) direct effects of fall on caregivers, and (4) barriers to receipt of recommended follow-up. | Nine of 14 interviewees were female, and 2 of 14 had cognitive impairment. Six of 12 caregivers were interviewed in reference to a patient with cognitive impairment. | • No communication or decision-making factors unique to patients with dementia or differing between dementia/nondementia patients were sought or identified. • Interviewed patients noted discordant recommendations between physicians in the ED, hospital, and primary care office. |

• Study was conducted at two EDs within one health system in the Northeast United States, therefore potentially restricting generalizability. • Women were over-represented as both patients and caregivers, reflecting that women are more likely to experience nonfatal falls and are more likely to be caregivers. |

| Han 2011, determine how delirium and dementia affect (1) the accuracy of the presenting illness and (2) discharge instruction comprehension in older ED patients 65 y and older at an academic ED from May 2008 to July 2008 | 202 patients completed presenting illness analysis. 85 patients did not complete presenting illness analysis. Median age for enrolled patients was 74 y |

ED patients age 65 y and older were included. Patients were excluded if they were present in the ED for greater than 12 h at enrollment, non-English speaking, were previously enrolled, did not complete the CAM-ICU, were nonverbal or unable to follow simple commands at baseline, were unarousable to verbal stimuli, or were from a nursing home. |

Cross-sectional convenience sampling conducted in a tertiary care, academic ED with 55,000 patient visits annually. Presence or absence of dementia determined by MMSE <24, IQCODE >3.38, or dementia documented in the medical record. Patients were interviewed and surrogates independently completed a written form after the ED nurse discharged the patient to capture comprehension of instructions |

Compared with patients without cognitive impairment, those with DSD had lower odds of agreeing with their surrogates with regard to why they were in the ED (adjusted POR = 0.20; 95% CI: 0.09 – 0.43). | 58.4% female, 16.3% nonwhite, 48% hearing impaired. Significant health literacy differences noted with higher dependence reading hospital materials in those who did not complete the presenting illness analysis. |

• Of the 287 patients studied, 25.8% had delirium and 46.7% dementia. • Dementia patients were less likely than noncognitive impairment patients to have concordance with discharge diagnosis (81% dementia vs. 87% no CI), ED return instructions (27% vs. 49%), and follow-up instructions (73% vs 81%) and delirium superimposed on dementia was even lower for all 3. |

• In multivariable analysis dementia alone was not associated with decreased recall of discharge diagnosis (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.33–1.60), ED return instructions (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.26–1.32), or follow-up instructions (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.26–1.21). • Small sample size from single urban academic ED limiting external validity. |

| Harwood 2018a, identify teachable, effective strategies for communication between healthcare professionals and people living with dementia, and to develop and evaluate a communication skills training course | Develop educational intervention to improve communication between healthcare teams and persons with dementia | Healthcare team members identified as good communicators by their peers were targeted. | An “intervention development team” of speech and language therapists, nurses, doctors, patient, and public representatives developed a dementia communication skills course after a systematic review. | Two day training attended by 45 healthcare personnel (8 doctors, 19 nurses, 17 allied health providers, one coordinator) | 89% of trainees were white | • Confidence in Dementia Scale scores improved after the course, but post-training communication was more controlling and dominating by the Emotional Tone Rating Scale | • Hospital-based, not ED-based, so uncertain applicability to the more chaotic and decision-dense ED setting. • SR identified 26 studies evaluating dementia communication training interventions, but none in ED. |

| Harwood 2018b, understand how healthcare professionals communicate with people living with dementia admitted to geriatric wards at one UK teaching hospital between Sep-Dec 2015 | Video recording of 41 hospital encounters between 26 people with dementia and 26 professionals using the sociolinguistic method of conversation analysis to study patterns of real-life communication. | Healthcare team members identified as good communicators by their peers were targeted | Routine daily encounters on the ward were recorded with a wide angle lens camera and microphone worn by the healthcare provider. Dementia severity ranged from mild (27%) to moderate (54%) and severe (19%) and the average recording length was 9.5 minutes. |

Patterns between communication and patient cooperation or responsiveness were synthesized | None | • When initially reluctant to comply, patients were more likely to proceed with task achievement when the tone or the request was elevated move from “I was wondering if...” to (“Let’s...”) or when being more specific with the duration or location of an action. | • Closing with open-ended questions tended to extend the interaction “in a problematic way”. • Mixed messaging confuses or irritates patients, such as “I’m leaving now” but then asking another question. • Nonspecific language like “I’ll see you soon” can be confusing. |

| Le Guen 2016, 15 hospitals around Paris France, November 2004 to January 2006. | 2115 patients, mean age 87 y. | Patients ≥80 y old presenting to ED in a condition potentially requiring intensive care Exclusion criteria: comatose on admission or those deemed unable to express an opinion regarding their disposition |

Standardized questionnaire completed by the emergency physician provided individual and organizational characteristics general, social and medical data, mobility, falls, hospitalizations, nutritional status, comorbidities and treatments, reason for consultation an initial severity according to the MPM II score. | The primary outcome is not clearly defined, but the authors report whether the presence of dementia is associated with physicians asking critically ill patients their preference whether or not to admit to ICU | None | • Dementia reduced the probability of seeking patient’s opinion (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.25–0.83). • Patients’ opinion was more often sought when their functional autonomy was conserved (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.39–3.21) or when a relative questioned (OR 5.46, 95% CI 3.8–7.88). |

• The methods used by investigators to determine whether physician-patient communication occurred is unclear (physician self-report vs patient query vs direct observation). • More senior physicians were less likely to ask for patient opinion (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.35–0.66). |

| Marr 2018, large urban hospital in Hamilton, Ontario, October 2014 to March 2015. | 264 patients and 116 caregivers; ED patients mean age 79.5 and caregivers’ ages ranged 32–88 with mean age 60. | Inclusion criteria for patients: ≥65 y; able to read, write, and speak English: cognitively intact as determined by medical staff; living independently in the community (own home, retirement home); and were to be discharged home Inclusion criteria for caregivers: had to be the primary caregiver of the ED patient; had to be present in the ED and able to read, write, and speak English Exclusion criteria: seriously or terminally ill, or living in long-term care |

Two-stage methodology. Phase 1: participants completed a brief survey prior to ED discharge. Phase 2: telephone follow-up two to four weeks after ED visit. |

Identification of factors affecting the ability of older adults to self-manage their health following an ED visit | 53% of patients were female and 33% lived alone Survey noted communication with non-English native speakers as too fast and unclear |

• At discharge 90% of patients and 95% of caregivers “definitely understood” the information received at discharge. • In contrast at 4-week follow-up only 66% of patients indicated that they “definitely understood”. • Both patients and caregivers perceived (1) a lack of attention to concerns about how patients would manage at home, (2) limited understanding of communication with ED staff (3) difficulty recalling details of the visit, and (4) perceived lack of support in cases where English is not the patients’ first language. • Patients and caregivers also noted poor understanding of causation of symptoms, factors related to decision to discharge, and confusion generated by inconsistent messaging between healthcare providers. • Other factors identified including inadequate contemplation of capacity of caregiver to provide support, caregiver stress, and social determinants of health. |

• Cognitively impaired patients excluded so no comparison of dementia to non-dementia patients. • No specific communication strategy assessed. • Single Canadian ED setting, potentially limiting external validity. • Exclusion of critically ill and non-English language patients limits external validity. • Patients and caregivers were not required to participate in dyads |

| McCusker 2018, 4 Quebec EDs, July 2014 to February 2016. | 843 eligible patients were contacted by a research assistant and 481 (57%) provided written consent to participate, and 412 completed the 1-wk follow-up interview. | Inclusion criteria: ≥75 y, resident of Quebec, discharged to the community after an unplanned ED visit, either the patient had the capacity to be interviewed or there was an accompanying family member who was able to respond, ability to answer questions in English or French. Exclusion criteria: patients expected to be discharged but later admitted. |

Twenty-six questions based on 6 domains of care found in the literature were developed: 16 questions were administered to all patients; 10 questions were administered to bed patients only. The six domains of care were overall perceptions of communication, interpersonal attributes of care (respect), waiting times, family needs, physical requirements, and transitional care needs (patient-centered discharge information & communication with the primary physician). Regression analyses were used to validate the scales, using 2 validation criteria: perceived overall quality of care and willingness to return to the same ED. |

The primary objective was to develop and validate measures of ED visit experiences of an of patients ≥75 y as reported by patients or family Two questions used for validation purposes: 1) “How do you evaluate the quality of care you received in the ED, not counting the waiting time?”; 2) Willingness to return to the same ED was elicited with the question “If you had the same or another health problem requiring emergency care, would you return to the same hospital?” | The study sample with follow-up was 67% women, 82% born in Canada, and 82% French speaking. 13.7% completed some elementary school, 38.5% completed some high school and 47.8% completed high school. |

• Prevalence of dementia or suspected cognitive impairment or lack of capacity is not reported. • Communication problems were associated with English-speaking, separated or divorced/single marital status, or educated beyond elementary school. • Communication problems were associated with lower perceived quality of care and less willingness to return to the same ED. |

• Only 57% of eligible patients consented. • Canadian setting and selective attrition of non-Canadian citizens may limit external validity • Patients refusing to participate were older than participants (mean 85 vs 83 y). • Patients lost to follow-up were more often older, bedbound, and had ED length of stay >12 hours. |

| Ní Shé 2020, Dublin Ireland. | Face-to-face interviews with health and social care professionals, persons living with dementia, and care partners. | None | Interviews and validation groups conducted with family carers (n = 5) and older people with a diagnosis of dementia (n = 8) in 2 acute hospitals. In addition, interviews were conducted with health and social care professionals (n = 26) Interviews focused on contextual characteristics as well as barriers and enablers of assisted decision making |

Barriers and enablers associated with communication were identified. Time and timing were consistently identified as a critical factor. |

None | • Factors (barriers and enablers) associated with communication included supporting capacity by adopting a functional approach, adapting the decision-making physical environment, enhancing decision/support resources, optimizing communication methods, upholding patient preferences, and sustaining trust in physidan-patient relationship. | • Interviews conducted in large urban hospitals and may not reflect rural or community/non-academic settings |

| Nielsen 2019, ED of a 1150-bed university hospital in Denmark | 11 older adult interviewees | Inclusion criteria: acutely admitted patient ≥65 y, discharged directly to their own home from an ED short-stay unit, and living in a larger municipality in Denmark (335,000 inhabitants). Exclusion criteria: terminal illness, severe dementia or unable to speak and understand Danish. |

Qualitative research design involving semi-structured interviews Eleven qualitative interviews with older adults conducted 2 wk after their discharge. The transcribed interviews were analyzed using systematic text condensation. |

The primary objective was to reduce risk of readmission by improving current discharge practice of older adults | None | • Four themes emerged as central to the participants’ experience of return to their everyday lives and their experiences of being discharged: (1) “pain and fatigue limited performance of daily activities”, (2) “frustrations and concerns”, (3) “the importance of being involved and listened to during admission”, and (4) “the importance of being prepared for being discharged” | • Interviews conducted in a single hospital with participants involved in a clinical trial receiving a specific intervention, so may lack external validity. • Severe dementia excluded. • Participants emphasized that it was important to be involved in decision-making and be listened to during admission, especially during the medical interview. Some experienced that the various doctors did not know what each other had said or done. |

| Nilsson 2012, 12 medically oriented wards at one Swedish university hospital, September-October 2009 | 391 assistant nurses (33%), registered nurses (55%), allied health (4%), and physicians (7%) working in acute care units with a mean age of 35.7 y | All acute care staff who worked with patients aged 70 y or older were considered eligible for inclusion: assistant nurses, registered nurses, allied health and physicians | Cross-sectional survey | The primary objective was to explore attitudes held by staff working in acute care units towards patients aged ≥70 y with cognitive impairment, and to explore factors associated with negative attitudes | None | • Only 27% report that cognitive status is formally assessed on wards. • The majority (86%) of respondents enjoy caring for older patients. • Respondents did not report clearly positive or negative attitudes towards older patients with cognitive impairment. • Being younger and working as an assistant nurse were associated with negative attitudes toward patients with cognitive impairment. • Staff reporting low strain in working with cognitive impairment patients also had more positive attitudes. |

• Dementia patient behaviors identified as most difficult were aggression and anguished behaviors. • Ward survey, not necessarily representative of ED. • Small sample from a single university hospital in Sweden and convenience sampling may limit external validity. • Half (52%) of participants had <10 y experience. • No communication strategies or differences between non-dementia patients were evaluated. |

| Parke 2013, 2 Canadian EDs, November 2010 to June 2011 | 10 dyads were recruited (10 older adults and 10 family caregivers), mean age 87 y. Researchers also interviewed 10 ED nurses (RNs) and four geriatric consult service nurse practitioners | Patient inclusion criteria: community-dwelling adults ≥60 y who had visited an area ED at least once in the 6 mo prior to the interview: could read, write, and speak English; were considered to have mild to moderate cognitive impairment associated with ADor mixed dementia diagnosis; had a MMSE score between 18 and 23; could give consent or have a proxy decision maker (caregiver) who could give consent; and had a caregiver willing to participate. Patient exclusion criteria: nursing home resident, other types of dementia, and caregiver not willing to participate. Care partner inclusion criteria: community-dwelling family or other volunteer caregiver of the older adult participants who were willing to be interviewed, English speaking; and visited the ED in a caregiving role for the adult ≥1 time in the 6 mo prior to the interview Care partner exclusion criteria: being in a caregiving role <1 y. | Interpretive, descriptive exploratory design with 3 iterative, interrelated phases: Phase 1 audio-recorded semi-structured interviews by trained research assistant lasting 1.5 h; phase 2 created a photographic narrative journal using staged scenes and story boards to empower participants to articulate their own stories; Phase 3 photo elicitation focus groups to audio-record responses and personal stories stemming from the photographic narrative journal. | The primary objective was to identify factors that facilitate or impede safe transitional care for community-dwelling older adults with dementia and to identify practice solutions for nurses. Four negative reinforcing consequences of a “cascade of vulnerability” were identified: (1) being under-triaged; (2) waiting and worrying about what was wrong; (3) time pressure with lack of attention to basic needs; and, (4) relationships and interactions leading to feeling ignored, forgotten and unimportant. | None | • In an aging population where dementia is becoming more prevalent, the unit of care in the ED must include both the older person and their family caregiver. • Negative reinforcing consequences can be interrupted when nurses communicate and engage more regularly with the older adult-caregiver dyad to build trust. |

• Two Canadian EDs and small sampling of dyads and nurses without physician voice limit external validity. • No nondementia comparator or communication strategy evaluated. • Efforts to “hear the voices” of individuals with dementia were hampered by the effect of the disease on the older adults’ stamina and their ability to participate in interviews and focus. • Nurses and dyads were drawing from separate experiences. • Caregivers in our study described their particular experiences emphasizing problems rather than positive encounters |

| Petry 2019, 2 Swiss urban, university-affiliated tertiary care hospitals, May-October 2017 | Eighteen families, represented by 7 older persons with cognitive impairment and 20 family members, median patient age 63 y | Inclusion criteria: older persons with a diagnosis of dementia, mild cognitive impairment or those who presented with self-reported or nurse-observed cognitive impairment. Exclusion criteria: older persons with delirium or severe hearing limitation. At least one family member or someone close as indicated by the older, hospitalized person, or as designated in the patient record was invited to participate | Qualitative design using inductive content analysis The unit of analysis were families | The primary objective was to generate an in-depth understanding of the experiences of acute care processes and the needs of older, hospitalized, older persons with cognitive impairment and their family members Seven core dimensions were identified as constituting the acute care experience from participants’ perspective. In relation to care for persons with cognitive impairment, caring attentiveness and responsiveness were important, whereas family members valued access to staff and information, participation in care, and support over time. | None | • Participants reported encounters that lacked such attributes of caring attentiveness, as one family member explained about a nurse: “She came in, no hello, no good-bye, she said nothing” • Such encounters instilled doubts about health professionals’ aptitude for the profession, but also about staffs’ empathy in caring for persons with cognitive impairment: “They apply good dressings, personal hygiene is all is very good, really, nothing to complain there. They do their job, but nothing more. The humane, the extra mile you could go, that’s more difficult” |

• Swiss setting and small sample limit external validity • 18 families recruited but only 7 individuals with cognitive impairment participated, so these perspectives are primarily those of care partners. • While this study attempted to include persons with mild cognitive impairment and dementia, it is likely that the voices of those with more advanced forms of cognitive impairment, who are at high risk for poor care experiences, are not, or only indirectly represented in this study. |

| Pilotto 2011, Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza Hospital (IRCCS, San Giovanni Rotondo, Italy), in the Andalusian Centre of Innovation, ICT (CITIC Foundation, Malaga, Spain), in the CETEMMSA Technological Centre (Barcelona — Spain), and in the KMOP nonprofit Organization (Athens, Greece), June-August 2009 | 223 patients: 115 were from Italy (M = 45, F = 70, mean age 79 y), 85 patients from Spain (M = 42, F = 43, mean age 78 y), and 23 patients from Greece (M = 8, F = 15, mean age 81 y). | Inclusion criteria for patients with AD: age ≥65 y; diagnosis of AD according to the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-AD and Related Disorders Association Work Group; and ability to provide an informed consent or availability of a proxy for informed consent. Exclusion criteria: serious comorbidity, tumors and other diseases that could be causally related to cognitive impairment (infections, vitamin B12 deficiency, anemia, disorders of the thyroid, kidneys or liver), history of alcohol or drug abuse, head trauma, psychoactive substance use and other causes of memory impairment. No specific inclusion/exclusion criteria for caregivers. | Systematic Interview study design All relatives/caregivers of patients with AD were shown a 5-minute video on the technological devices and the functions that can be installed within the homes of AD patients by Smart Home for Elderly People (HOPE) Project After the video relatives/caregivers completed a questionnaire (HOPE Questionnaire) to evaluate the needs and preferences of relatives, care partners, and pateints with AD. | The primary objective was to improve the quality of life and safety of patients with AD in the Geriatrics Unit using Information and Communication Technology systems | None | • Over 90% of relatives/caregivers of patients with patients with AD noted that the following components of geriatric unit care could be improved by incorporating Information and Technology systems into geriatric units: (1) patient quality of life, quality of care, and overall safety; (2) monitoring of bed-rest and movements, medication use, and ambient environmental conditions; and (3) emergency communications. • Less than 50% of care partners felt that Information and Technology systems would be useful to reduce risks at home. • Care partners felt patients with AD ages 75–84 y were more likely to benefit from these technologies than AD patients >85 y. • Care partners also felt that patient safety was more likely to improve for moderate dementia patients than for mild dementia patients. |

• The impetus for this research was to address the market potential for these products, so potential health inequities were not explored or contemplated. |

| Shankar 2014, systematic review exploring older adults’ views of their ED care | The original research manuscripts were published from the UK (8), US (7), Sweden (6), Canada (3), Australia (2), and 1 each from New Zealand and Spain. One of those included populations from Sweden and the UK. | Inclusion criteria: exploration of older patient populations using qualitative methods or surveys focusing on hospital-based emergency care with outcomes pertaining to one of the IOM’s 6 dimensions of patient-centered care. Exclusion criteria: studies that excluded older adults, did not use qualitative or survey methods, were not hospital-based emergency care, or that lacked outcomes pertaining to IOM’s 6 dimensions. |

Systematic review with electronic search of PUBMED and CINAHL through March 2013 | IOM’s 6 dimensions of patient-centered care: (1) role of healthcare providers; (2) content of communication and patient education; (3) barriers to communication; (4) wait times; (5) physical needs in the emergency care setting; and (6) general elder care needs. | None | • Key conclusions included roles for ED staff to (1) assume leadership roles with medical and social needs; (2) initiate and sustain communication; (3) minimize communication barriers; (4) check on patients during prolonged periods of waiting; (5) attend to distress caused by the physical discomforts of the ED; (6) address general older adult needs including engagement of care partners when necessary. • Barriers to communication entail the staff’s acknowledgement of educational and cultural differences, as well as physical and mental disabilities, which may impede effective communication. • Older patients have increased needs for communication and accommodations from ED staff and that is accentuated when the language requirements are different from the usual language used in the ED setting. |

• Focus was not on dementia or communication but a more global assessment of patient-centered care. • Qualitative and survey methods synthesized do not necessarily provide representative samplings of the population and may neglect underrepresented populations and health inequities. • Meta-ethnography used to synthesize qualitative data is heavily dependent on the reviewer because it fails to offer a robust guide to sample studies for inclusion. |

| Suffoletto 2013, 2 academic EDs in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, June-August, 2012 [Abstract] | 89 respondents, mean age 77 y | Inclusion criteria: age ≥65 y Exclusion criteria: patients who lived in a nursing home or assisted living center, critically ill, or could not follow basic commands | Prospective observational design. Participants completed the Short Blessed Test, the Geriatric Depression Screen, and Snellen vision assessment during ED visit. Structured telephone interviews were conducted within 72 h of ED discharge assessing 4 domains of comprehension: diagnosis, expected course of illness, self-care instructions, and return precautions. Univariate logistic regressions quantified strength of association of various factors with poor comprehension. | The primary objective was to assess patients’ comprehension of their ED care and post-care instructions | 64% female; 25% Black race; 40% living alone | • 30% do not understand their diagnosis, 20% do not understand self-care instructions, 55% do not understand the expected course of illness, and 38% do not understand return precautions. • Patients screening “positive” (higher risk for dementia) on the Short Blessed Test were at increased risk of poor understanding for at least one of those domains of comprehension (OR 8.8, 95% CI 1.1–74.1) |

• Small sample size from one city and academic setting limit external validity. • No communication strategy evaluated. • Many community-dwelling older ED patients do not understand their care or their discharge instructions or return precautions. • Strategies incorporating dementia screens are needed to improve identification of older patients at higher risk for poor comprehension. |

| Watkins 2019, Ireland, February 2017—March 2018. | 15 family members were interviewed 12 ED nurses were observed |

Semi-structured individual interviews using Appreciative Inquiry methods with purposive sampling of family members and ED nurses. Interviews ranged from 30–75 min and were audio-taped and transcribed. |

The primary objectives were (1) to generate insights about what family members of older people with dementia value during episodes of ED care and (2) explore emergency nurses’ experiences caring for older people with dementia in the ED. | None | • Two themes emerged (1) Four components of care matter most to families (quick triage, cubicle space for privacy, frequent contact with ED nurses, and compassion overrides technical skills) and (2) 2 consistent challenges recur for family and ED nurses (vulnerability and maintaining vigil). • Respondents believe that older person with dementia must be triaged and evaluated by the ED physician within 1-h of arrival. • Further education is needed to assist emergency nurses to establish rapport and incorporate family member insights as part of care planning and assessment of older patients with dementia. |

• Single-center setting and small sample size limit external validity to other sites. • Researchers originally intended to invite older people with dementia to participate. However, older people with dementia presenting to ED were in an advanced stage of the disease or were too ill to participate. • A high proportion of nurses in this study were newly qualified or had less than 2 y of ED experience (41%). Junior nurses may have felt obliged to participate since the researcher was a clinical facilitator in ED. • Physicians and ancillary staff were not included as the emphasis was on nursing perspectives and interventions. |

|

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CAM-ICU, confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit; CI, confidence interval; DEI, diversity, equity, inclusion; DSD, delirium superimposed on dementia; ED, emergency department; EHR, electronic health record; F, female; IQCODE, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly; INTERACT, Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers; IOM, Institute of Medicine; M, male; MPM II, Mortality Probability Model II; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NH, nursing home; OR, odds ratio; PI, presenting illness; POR, adjusted proportional odds ratio; SNF, skilled nursing facility; SR, systematic review; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

None of the studies evaluated a communication strategy. Some researchers surveyed PLWD or dyads of PLWD-care partners about barriers or facilitators of effective communication in the medical setting. Others surveyed older adults without stratifying responses by the presence or absence of dementia. Few studies occurred in the ED setting, but instead incorporated the ED as part of the overall hospital communication experience. Some studies excluded individuals from nursing homes, and none of the studies evaluated the severity of dementia in association with the effectiveness of communication. Evaluating health equity was not the focus of any of these studies and some intentionally excluded individuals with severe dementia or sensory impairments. Most of the included studies were from the United States (8)5,21–26 with the remainder of the studies from the Canada (3),27–29 United Kingdom (1),30 Ireland (2),31,32 France (1), Denmark (1), Sweden (1), and Switzerland (1). The UK study was a government report published as an online book, and 2 separate textbook chapters were included.30 One study included multiple mainland European sites,33 and another was a systematic review of older adult views around ED care processes.34

ED-Based Research

Twelve studies evaluated elements of communication in the ED setting.5,21,24–29,31,34–36 Baraff et al conducted a patient focus group to understand older adults’ perspectives on the ED experience. Patient participants noted that ED staff communication is usually lacking and often rushed.5 Benjenk et al reported a multivariable regression analysis in which cognitive impairment was not independently associated with medication knowledge, follow-up adherence or awareness of “red flag” symptoms.21 Gettel et al interviewed patients after an ED evaluation for a fall, noting that a prevalent communication problem was discordant messaging between physicians in the ED, hospital, and primary care office.24 Han et al noted an association between dementia and patient misunderstanding of ED diagnosis, return precautions, or follow-up instructions.25 Suffoletto et al also noted an association between cognitive impairment and poor comprehension of ED diagnosis, anticipated course of illness, and return precautions.26 Similarly, Marr et al noted decreased retention of ED discharge instruction knowledge at 66% for PLWD.27 Marr et al also noted poor ED provider-to-PLWD communication, exacerbated by inconsistent messaging between providers and inadequate support for non-English speaking individuals.27 Dunnion et al surveyed ED nurses and physicians, as well as outpatient consultants noting that interprofessional communication is disjointed with substantial opportunities to improve older adult care with improved information exchange and consistency of messaging with patients.31 McCusker et al surveyed ED patients and noted an association between communication problems and perceptions of lower quality care with corresponding unwillingness to return to the same ED for subsequent care.28

Parke et al surveyed 10 PLWD-care partner dyads along with 10 ED nurses and noted 4 themes around a “negative reinforcing consequences of a cascade of vulnerability”: under-triage, waiting/worrying about what was wrong, provider time pressures while ignoring basic needs (food, toileting, comfort), and interactions leading to feelings of being forgotten and unimportant.29 Similarly, Watkins et al interviewed 15 families of PLWD about their ED experience with the following priorities identified: quick triage, privacy, sufficiently frequent contact with ED healthcare team, and compassion.36 Nielsen et al interviewed 11 older adults discharged from the ED noting that attention to pain and activity limitations and frustrations/concerns, while being involved and listened to during the ED visit were central to their satisfaction with care.35 Shankar et al published a systematic review focusing on patient-centered care for older adults in the ED that was not focused on either PLWD or communication, but recommended that physicians and nurses minimize barriers to effective communication by acknowledging that some older adults (such as PLWD) may require accommodations for reliable information exchange and retention.34

Prehospital and Hospital-Based Research

Gettel et al reported that baseline mental status was missing in 75% of nursing home-to-ED transfers.23 Nilsson et al surveyed nurses (88%) and physicians (7%) from a geriatric acute care unit who noted that only 27% formally assessed cognitive impairment, and that younger aged healthcare providers and assistant nurse status were associated with negative attitudes toward PLWD.37 Harwood et al describe a hospital training course to improve communication with PLWD. After the course, providers’ confidence to communicate with PLWD improved, but communication became more controlling/domineering.30 The same government report from Harwood et al described video recordings of 41 hospital encounters between inpatient nurses/physicians and PLWD noting that mixed messaging or vague/nonspecific language was irritating for the patient, but closing a conversation with an open-ended question was sometimes problematic for the healthcare team with multiple responsibilities.30 Petry et al interviewed 18 families of PLWD and care-partner dyads after a hospitalization, noting that encounters lacking attributes of caring attentiveness or empathy were frequent and associated with doubts about health professional’s aptitude to provide healing care.38 Pilotto et al hypothesized about the potential for “information and communication technology systems” to improve PLWD patient safety and quality of life after a hospitalization via monitoring of ambulation and medication use, while providing an easily accessible emergency communication device.33 Surveyed PLWD care partners believed that this technology was more likely to promote patient safety and communication for persons living with moderate dementia than for those with mild or severe dementia.33

PICO-2: Dementia Communication Strategies

The literature search identified 2687 titles, and 43 were reviewed as full texts. A total of 3 articles were included in the evidence synthesis of this question (Supplementary Material 3). The interrater agreement for inclusion or exclusion during the initial screening of abstracts and titles was poor (k = 0.19) and fair during the full-text reviews (k = 0.36). The 3 included studies were a systematic review,39 a scoping review40 and 1 large National Health Service Foundation Trust in the North of England.41 A summary of the findings from each included article is in Table 3.

Table 3.

PICO-2 Evidentiary Table: Dementia Communication Strategies

| Study, Location, Timeframe | No. patients (Median or Mean Age) | Inclusion Criteria/Exclusion Criteria | Study Design/Communication Strategy Assessed | Factors Assessed or Primary Outcome | Healthcare Equity Factors Assessed or Reported | Prevalence of Communication-Related Outcomes | Comments/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Geddis-Regan 2021, Systematic Review thru July 2020 | Eight studies included but neither the age ranges nor mean/median age of populations are reported | Inclusion criteria: manuscripts assessing effectiveness of interventions to support shared or surrogate decision-making for persons living with dementia, or examining decisions about healthcare interventions, or evaluation of actual decisions made as opposed to hypothetical decisions. Exclusion criteria: studies of interventions that had not been evaluated, isolated CPR decisions, non-healthcare decisions, non-dementia populations, focus only on clinician’s role in decision-making, or non-English language. |

Systematic review with medical librarian-assisted electronic search of Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. The grey literature was also searched via OpenGrey. Citations from included studies and systematic reviews were also reviewed to identify additional relevant studies. | Fixed outcomes not specified due to range of measures and lack of standardized assessment. Heterogeneous interventions evaluated across individual studies including feeding option decision aid in advanced dementia (2), advanced care planning following education initiative (2), WeDECide workshop to assist patients’ SDM (1), Goals of Care decision-aid (1), dementia-specific trigger for palliative care (1), Support-Health-Activities-Resources-Education (SHARE) program (1). Range of outcomes assessed included knowledge acquisition, decisional conflict, frequency of discussions about options, degree of engagement (OPTION-12), level of SDM, perceived competence/importance of SDM, quality of communication, completion of medical orders for scope of treatment, care preferences, emotional disruption, positive/negative affect |

None | • WeDECide RCT demonstrated increased advanced care planning SDM sustainability at 6-mo. • The Goals of Care Decision Aid intervention slightly improved communication quality at 3-mo and family concordance with physician at 9-mo or death. • SHARE intervention does not affect incorporation of patient’s values and preferences into advanced care planning. |

• No study occurred in ED setting and none of these studies describe scenarios where time or resources are typically available during emergency care. • Studies reported from US, UK, or Belgium, which limits external validity to other settings. • Only 1 study occurred in participants living with early-stage dementia; others were later stage dementia paired with caregiver dyads. • Thirteen additional studies described that evaluated hypothetical scenario decision-making, some of which could be feasible in ED (Fact Boxes, Talking Mats, compassion intervention, and video decision aid). |

| Pecanac 2018, scoping review thru May 2017 | 28 studies included in the review from US (13), UK (5) Japan (2), Australia (2), Belgium (1), Canada (1), Israel (1), and one from both the Netherlands and Australia | Inclusion criteria: published research that contained primary data from a quantitative or qualitative study involving treatment decision-making in the acute care setting for persons with AD or other dementias, examined the process of decision-making or factors effecting decisions, published in English. Exclusion criteria: only reported outcomes of decisions, used a hypothetical vignette, examined decision-making solely in settings outside of the hospital, such as in long-term care; or studied patients with acute or sudden cognitive impairment. |

6-step framework for a scoping review followed: (1) Identifying the research question, (2) Identifying relevant studies, (3) Study selection, (4) Charting the data, (5) Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results and (6) Consultation. Four databases searched in consultation with a medical librarian (PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, & PsychINfo) |

The primary objective was to synthesis current state knowledge about treatment decision making involving persons living with dementia during episodes of acute care Identified 5 categories of factors that influence the decision-making process: knowing the patient, culture and systems, role clarity, appropriateness of palliative care in dementia, and caregiver need for support |

Patient race identified as a factor in some decisions with Black or Hispanic patients more likely to receive feeding tubes, while white patients were more likely to avoid aggressive care. | • Caregivers consistently reported limited involvement in planning the hospital care, and they did not receive the communication they felt was necessary to fulfill their role • Nurses took on the roles of conversation initiator, go-betweens, and facilitators to enhance physician-family communication • Being involved in treatment discussions with the healthcare team was very important to caregivers, although many reported this communication and caregiver involvement was “largely absent” in hospitals. |

• Scoping review without assessing quality of individual studies or risk of bias. • Physicians expressed concerns about lack of palliative care resources as barrier to accepting more dementia patients. • Physicians’ self-defined role in communication was a barrier. Primary care physicians relied on ED and hospital physicians to provide care partners updated information about dementia patient’s health status, while ED physician choose not to initiate palliative care consult in deference to inpatient physicians and primary care. • Some members of the healthcare team viewed dementia as a normal part of aging rather than a disease process and wanted more information about dementia treatment options once educated. |

| Prato 2019, one large National Health Service Foundation Trust in the North of England, June 2015-June 2017. | 6 patients (mean age 80) | Inclusion criteria: age > 55 y, identified as “confused” by health care staff. Exclusion criteria: patients admitted following a stroke or diagnosed with a learning disability |

Ethnographic, nonparticipant observations of older patients with either dementia or delirium (or both) and semi-structured interviews with their relatives and the health care staff involved in their care. One interview was also carried out with a member of staff who was involved in dementia care in the Trust. |

The primary objective was to identify the factors that contribute to a positive or negative hospital stay for older patients with cognitive impairment Three themes were identified: (1) Value of the person (through staffactions, interactions and person-centered care); (2) Activities of empowerment and disempowerment (family as agents of empowerment and nursing staff decision-making and empowerment); and (3) the interactions of environment with patent well-being (physical environment, social and organizational environment, and being bored). |

None | • Relatives and participants stressed the importance of robust communication between ward-based staff, patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners and/or relatives to ensure a positive hospital experience. | • Limited sample size and geographic region limits external validity • Surveyed patients are biased towards healthier subset of adults with cognitive impairment who are able to vocalize and mobilize, either with assistance or independently. • Researchers were only able to recruit participants with an available family member so responses may differ for dementia patients who do not have family. • The authors opine that prior research has demonstrated “that ward staff often ration communication and can even ignore patients with cognitive impairment”. |

ACP, advanced care planning; ED, emergency department; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases; SDM, shared decision-making.

One of those 3 reports was a systematic review that synthesized 8 studies evaluated several heterogeneous interventions including a feeding option decision aid in advanced dementia, advanced care planning following education initiative, WeDECide workshop to assist patients’ SDM,42,43 Goals of Care decision-aid,44 dementia-specific trigger for palliative care, and Support-Health-Activities-Resources-Education (SHARE) program.45 WeDECide demonstrated increased advanced care planning SDM sustainability at 6 months; a Goals of Care Decision Aid intervention slightly improved communication quality at 3 months and family concordance with physician at 9 months or death; and SHARE intervention did not affect incorporation of patient’s values and preferences into advanced care planning. Hypothetical scenarios of decision-making, some of which could be feasible in ED like Fact Boxes, Talking Mats, compassion intervention, and video decision aid were described.39

Pecanac et al included 28 articles on a scoping review on treatment decision making involving PLWD during episodes of acute care and identified 5 factors that influence the decision-making process: knowing the patient, culture and systems, role clarity, appropriateness of palliative care in dementia, and care partner need for support. Caregivers consistently reported limited involvement in planning the hospital care, and they did not receive the communication they felt was necessary to fulfill their role. Being involved in treatment discussions with the healthcare team was very important to care partners, although many reported this communication and care partner involvement was “largely absent” in hospitals. The communication role was largely performed by nurses, who took on the roles of conversation initiator, go-betweens, and facilitators to enhance physician-family communication.40

Prato et al reported factors that contribute to a positive hospital stay, including (1) value of the person through staff actions, interactions, and person-centered care; (2) activities of empowerment (family as agents of empowerment and nursing staff decision-making and empowerment); and (3) the interactions of environment with patent well-being (physical environment, social and organizational). Participants stressed the importance of robust communication between hospital staff, PLWD and their care partners to ensure a positive hospital experience.41

Only 1 included study addressed healthcare equity factors and described that patient’s race was identified as a factor in some decisions with Black or Hispanic patients more likely to receive feeding tubes, while white patients were more likely to avoid aggressive care.40

Consensus Conference

Based on this scoping review and prior to the Consensus Conference the GEAR 2.0-ADC Communication/Decision-Making Work Group attained agreement on 5 research questions summarized in Supplementary Material 3. During the Consensus Conference, attendees reworded and ranked these 5 questions. The GEAR 2.0-ADC work group included 61 participating stakeholders (expanded from the 53 stakeholders at the onset and including 25 ED physicians/nurses/social workers/pharmacists, 29 non-ED healthcare providers, and 7 PLWD or care partners). There was 100% voting participation by all 61 GEAR 2.0-ADC members.

When pooled together, Consensus Conference stakeholders prioritized ED communication/decision-making research priorities as demonstrated in Table 4. Identifying barriers and facilitators to effective communication between ED healthcare teams and PLWD/care partners was the highest priority across all stakeholders. As demonstrated in Supplementary Material 3, subsequent ratings of priorities differed, with PLWD and care partners next prioritized understanding of communication roles for the entire ED team (social work, nurses, technicians, pharmacists, physicians), whereas ED providers prioritized identifying measures of effective communication as the next most important research focus. Non-ED providers placed identification of effective communication measures as the least important priority, while ED providers ranked the role of the communication for the ED team (the second highest priority for PLWD/care partners) as the least important priority.

Table 4.

Consensus Conference Ranking of Communication/Decision-Making Question Priority

| Research Priority Rank |

|---|

|

|

| (1) What are the barriers and facilitators of effective communication with PLWD (or their care partners) during an episode of ED care, with attention to actionable elements/ideas? |

| (2) What are valid and reliable measures or outcomes of “effective (short- and long-term) communication” in patients with dementia? |

| (3) What are the best practices (when/how) for engagement of care partners in care decision-making in the ED? |

| (4) How do individual, provider, and system-level factors that influence communication for ED patients living with dementia (or their care partners)? Examples: ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic factors or conscious or unconscious biases. |

| (5) How can each member of the ED care team (eg, social work, physician, tech, nurses, etc.) ensure high-quality communication with PLWD, care partners, and other team members? |

Discussion

Patient-healthcare team communication in the context of the ED is multidimensional. At the most basic level, communication entails the exchange of essential details about the medical care delivered, including the suspected diagnoses, testing recommendations or interpretations, management options, and anticipated illness or injury trajectory with the corresponding recommendations for subsequent inpatient or outpatient care. Communication also includes nonverbal cues and perceptions of empathy that patients and families sometimes value more than the aptitude of medical care decision-making. In general adult populations of younger and older patients without dementia, the effectiveness with which ED nurses and physicians convey medical information like diagnosis, prescriptions, follow-up instructions, and return precautions is overall poor.2,46 Communication with older adults is further complicated by sensory deficits such as hearing loss or visual impairments that are frequently unrecognized by ED providers, but when recognized provide reasonably simple opportunities to simultaneously improve information exchange and patient satisfaction.16,47

We identified no research directly comparing ED-based communication strategies between PLWD and persons without dementia. Furthermore, similar to prior reviews of dementia-appropriate ED care, we found scant evidence to guide communication with PLWD.48 We explored communication differences between PLWD/care partners and other older adults and were largely limited to exploratory surveys of patient, care partner, or healthcare teams and no direct comparators. With one exception, ED communication with PLWD was associated with less effective ability to recall key details such as the diagnosis, medical management recommendations, or concerning symptoms mandating return visits. Inconsistent information provided to patients by nurses or different physician teams was repeatedly identified as a barrier to effective communication for PLWD and their care partners. Empathy and sufficient time-to-communicate were also identified by multiple stakeholder surveys as attainable, high-priority barriers to overcome. Unfortunately, educational initiatives to improve communication with PLWD did not consistently improve the situation and demonstrated the possibility of a shift towards a more authoritarian tone.30

Our scoping review for communication strategies identified interventions like WeDECide42 and a Goals of Care Decision Aid44 as effective tools for improving communication quality and family concordance for PLWD in very specific decisional scenarios. In studies outside the ED, the factors that influence the decision-making process in PLWD include knowing the patient, culture and systems, role clarity, appropriateness of palliative care in dementia, and care partner need for support. Care partners consistently reported limited involvement in planning the hospital care, and they did not receive the communication they felt was necessary to fulfill their role.29,40,41 Being involved in treatment discussions with the healthcare team was very important to care partners. Communication factors that influence satisfaction with the hospital experience for PLWD included valuing of the person through staff actions, interactions, and person-centered care; activities of empowerment; and interactions of the environment with patient well-being (physical environment, social and organizational). Robust communication between hospital staff, PLWD and their care partners improves the hospital experience.41