Abstract

Background

Decision-making in palliative care usually involves both patients and family caregivers. However, how concordance and discordance in decision-making manifest and function between patients and family caregivers in palliative care is not well understood.

Objectives

To identify key factors and/or processes which underpin concordance and/or discordance between patients and family caregivers with respect to their preferences for and decisions about palliative care; and ascertain how patients and family caregivers manage discordance in decision-making in palliative care.

Methods

A systematic review and narrative synthesis of original studies published in full between January 2000 and June 2021 was conducted using the following databases: Embase; Medline; CINAHL; AMED; Web of Science; PsycINFO; PsycARTICLES; and Social Sciences Full Text.

Results

After full-text review, 39 studies were included in the synthesis. Studies focused primarily on end-of-life care and on patient and family caregiver preferences for patient care. We found that discordance between patients and family caregivers in palliative care can manifest in relational conflict and can result from a lack of awareness of and communication about each other’s preferences for care. Patients’ advancing illness and impending death together with open dialogue about future care including advance care planning can foster consensus between patients and family caregivers.

Conclusions

Patients and family caregivers in palliative care can accommodate each other’s preferences for care. Further research is needed to fully understand how patients and family caregivers move towards consensus in the context of advancing illness.

Keywords: methodological research, supportive care, terminal care, symptoms and symptom management, communication, family management

Key messages.

What was already known?

Family caregivers provide high levels of informal care.

Patients and family caregivers can differ in their preferences for care.

What are the new findings?

Discordance can be underpinned by relational conflict.

Advancing patient illness and impending death foster consensus.

What is their significance?

Clinical

Open communication can reduce discordance between patients and family caregivers.

Research

Consensus through advance care planning warrants further investigation.

Introduction

Family caregivers have significant caregiving roles in palliative care, providing important support to the person they care for.1 Family caregivers provide a combination of physical, psychological, emotional, social and financial support to the person with a life-limiting illness. Care is an inherently relational activity which widens the focus of palliative care to family.2 Assuming caregiving responsibilities for a significant other with palliative care needs often means that family caregivers are, by choice or circumstance, involved in decision-making in palliative care.3 4

Decision-making among patients and family caregivers in palliative care is complex. Patient and family caregiver preferences for care are shaped by one another because how patients and family caregivers navigate the illness journey is rarely independent of each other. Patients face difficult decisions about multiple domains of care (eg, symptom management, advance care planning and end-of-life care),5 and engage with a range of healthcare professionals who deliver formal care.6 In some cases, healthcare professionals situate the patient’s perspective central to care plans, but patients also become dependent on their family caregivers.7 Family caregivers in palliative care provide the majority of caregiving which their relative or friend receives8 9 and often function as key advocators and care coordinators.10 Family caregivers in palliative care make decisions with patients or sometimes for patients in situations where decision-making has been delegated.3 Indeed, family caregiver perceived burden can be a function of increasing family caregiver responsibility for decision-making.4 Family caregivers in palliative care themselves also have care needs that are addressed by formal services including, for example, psychosocial support and respite services,11 but there has been less focus on how patients impact on the decision-making process pertaining to formal care and support accessed by family caregivers. Lastly, while the palliative care approach recognises the needs of both patients and family caregivers,12 not all patients seek to involve significant others when making decisions about care, even when a significant other is available.

We know that patients and family caregivers in palliative care can have similar and different preferences for care, and that patient and family caregiver preferences and needs can diverge with illness progression.13 Moreover, patients and family caregivers can have different perceptions of treatment decision-making processes.14 However, prior to this review, it was unclear how concordance or discordance manifests and functions between patients and family caregivers in palliative care, with respect to their preferences for care and the decisions they make about care. Moreover, little was known about how patients and family caregivers manage their discordance when making decisions about care. Hence, the aims of this systematic review were to, first, identify key factors and/or processes which underpin concordance and/or discordance between patients and family caregivers in decision-making in palliative care and, second, determine how patients and family caregivers manage their discordance in decision-making in palliative care.

Methods

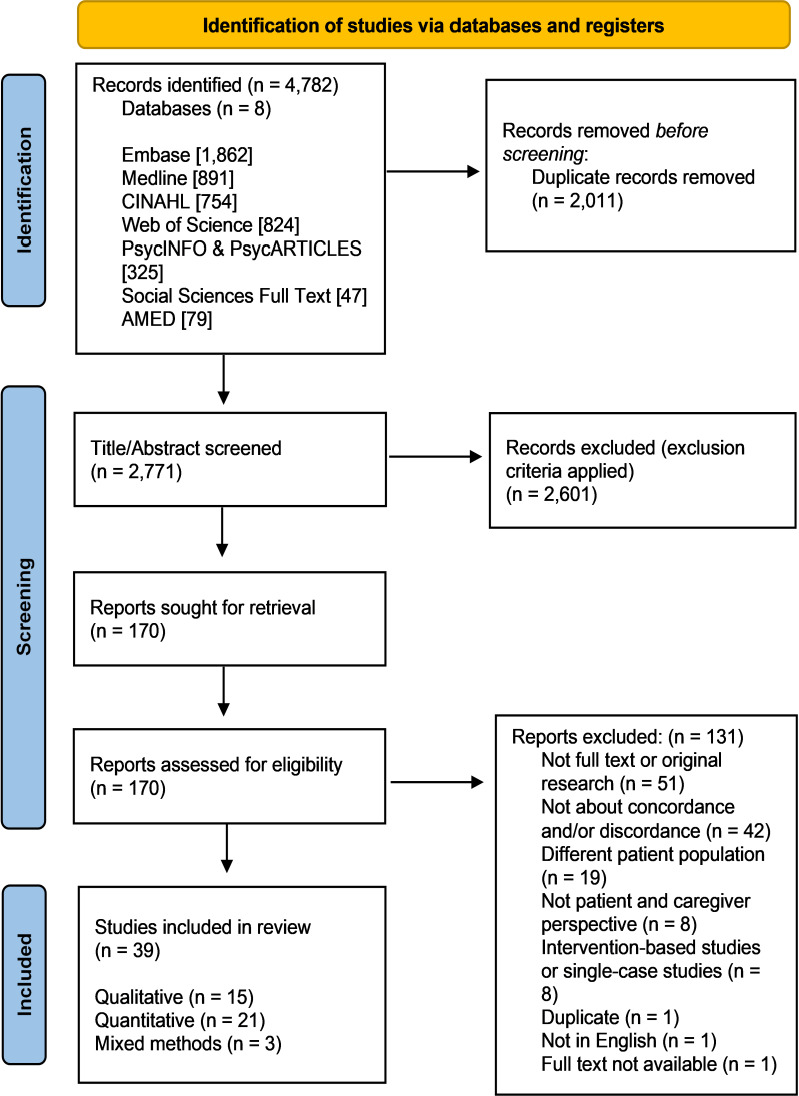

We conducted a systematic review with narrative synthesis15 of original evidence on concordance and discordance between patients and family caregivers in palliative care, pertaining to their preferences for care and decision-making in care. The review was conducted between June and September 2021 and the full search was run in June 2021. We carried out the search in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)16 to detail the number of records found, included and excluded and the reasons for exclusion.

Search strategy

The search was conducted using the following databases: Embase; Medline; CINAHL; AMED; Web of Science; PsycINFO; PsycARTICLES; and Social Sciences Full Text. A Boolean search strategy was first devised by authors SMS and DM in Embase and reviewed and approved by GF. The search terms were agreed through multiple rounds of discussion between SMS, DM and GF, to ensure that all terms were relevant and comprehensive. The search strategy was then tailored to the other databases searched. All search terms and the full search strategy are detailed in the online supplemental appendix 1.

bmjspcare-2022-003525supp002.pdf (113.5KB, pdf)

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included original peer-reviewed research, published in full and in English between January 2000 and June 2021. We limited our search to this period because more historical data may not be as relevant to current practice in the context of social change over time. We took the definition of palliative care as active holistic care of individuals with serious health-related suffering due to severe illness.17 Only studies in which data had been captured from the patient and family caregiver were included. This was because the focus of the review lay in the context of the relationship between patients and family caregivers. Studies were included if they reported on dimensions of (or any factors associated with) concordance and discordance between patients and their family caregivers, which pertained to their preferences for care and/or decision-making in care. The term ‘family’ in palliative care includes formalised or familial-based relationships, and those that are patient defined or self defined as significant. Our definition of family caregiver extended beyond familial-based relationships, and we included studies where family caregivers were family members, friends or any other form of significant other once they had been recruited as participants who had provided and/or were providing informal care and/or support to the patient. The review was limited to studies where patient participants were ≥18 years.

We did not limit the review to specialist palliative care or to end-of-life care, but we did exclude studies where patient participants did not have clearly advancing and non-curable conditions. In addition, although our inclusion was aimed at original peer-reviewed studies, we excluded intervention-based studies including randomised controlled trials as their focus was on acceptability or effectiveness of a given intervention rather than on explaining concordance or discordance in decision-making. We also excluded single-case studies. Studies which reported only on the patient or only on the family caregiver were excluded.

Extraction

The full search found 4782 records in total. The full set of records was uploaded to Covidence18 and 2011 duplicates were removed. SMS and GF screened all remaining records by title and abstract following the inclusion/exclusion criteria. A total of 2601 records were deemed not relevant. The remaining 170 records were then sought for full retrieval by SMS and assessed for eligibility. Any uncertainty regarding inclusion or exclusion of studies from this point was resolved by a collective review of the full text by SMS and GF. Figure 1 outlines the PRISMA flow diagram of the conducted review and the number of studies that met the criteria for inclusion.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Quality assessment

We used the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers19 and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)20 to assess the quality of the included studies.21–59 Twenty-one quantitative,21–41 15 qualitative42–56 and 3 mixed-methods57–59 studies were included in the review. The Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers was used to appraise the quantitative and qualitative studies because it allows for a replicable method of assessing the quality of a quantitative or qualitative study. Quality rating or summary scores range from 0 to 1.0 for each study. SMS appraised these studies, and GF independently scored a subset for internal consistency. The summary scores across the studies ranged from good to strong scores, with no study scoring below 0.7. The quality of the mixed-methods studies was assessed using the MMAT, chosen because it includes the option for assessing the quality of a mixed-methods study and accounts for the characteristics specific to each component (ie, qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods) of a mixed-methods study. The mixed-methods studies were appraised to be of moderate to high quality. We tabulated all of the 39 included studies into a table (see online supplemental table 1) under the standard domains of authors, location/setting, participants, aims, methods and key findings. Tables 1–3 outline the quality assessment of the included studies.

Table 1.

Quantitative studies. Quality assessed using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a variety of fields

| Authors | Question/objective sufficiently described? | Study design evident and appropriate? | Method of subject/comparison group selection or source of information/input variables described and appropriate? | Subject (and comparison group, if applicable) characteristics sufficiently described? |

If interventional and random allocation was possible, was it described? | If interventional and blinding of investigators was possible, was it reported? | If interventional and blinding of subjects was possible, was it reported? | Outcome and (if applicable) exposure measure(s) well defined and robust to measurement/misclassification bias? Means of assessment reported? |

Sample size appropriate? | Analytical methods described/justified and appropriate? | Some estimate of variance is reported for the main results? | Controlled for confounding? | Results reported in sufficient detail? | Conclusions supported by the results? | Summary score | ||

| An et al 21 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.86 | Yes | 2 |

| Bükki et al 22 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.86 | Partial | 1 |

| Davies et al 23 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.82 | No | 0 |

| Engelberg et al 24 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.86 | N/A | |

| Gao et al 25 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.91 | ||

| Hauke et al 26 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.77 | ||

| Heyland et al 27 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.91 | ||

| Heyland et al 28 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.73 | ||

| Hwang et al 29 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.82 | ||

| Kim et al 30 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.86 | ||

| Ozdemir et al 31 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.91 | ||

| Pruchno et al 32 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.86 | ||

| Sharma et al 33 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.91 | ||

| Shin et al 34 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.86 | ||

| Stajduhar et al 35 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.82 | ||

| Tang et al 36 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.95 | ||

| Tobin et al 37 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.91 | ||

| Wen et al 38 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.91 | ||

| Yoo et al 39 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.86 | ||

| Yun et al 40 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.91 | ||

| Zhang et al 41 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.91 |

The summary score for each study is derived by calculating the total score of relevant items (ie, all items except those ‘not applicable’) and dividing it by the total possible score when excluding ‘not applicable’ items.

N/A, not applicable.

Table 2.

Qualitative studies. Quality assessed using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a variety of fields

| Authors | Question/objective sufficiently described? | Study design evident and appropriate? | Context for the study clear? | Connection to a theoretical framework/wider body of knowledge? | Sampling strategy described, relevant and justified? | Data collection methods clearly described and systematic? | Data analysis clearly described and systematic? | Use of verification procedure(s) to establish credibility? (Yes or No only) |

Conclusions supported by the results? | Reflexivity of the account? | Summary score | ||

| Cheung et al 42 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.85 | Yes | 2 |

| Clarke et al 43 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.8 | Partial | 1 |

| de Graaff et al 44 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.9 | No | 0 |

| Dees et al 45 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.85 | NA | |

| Gerber et al 46 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.9 | ||

| Gerber et al 47 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | ||

| Holdsworth and King48 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.7 | ||

| Luijkx and Schols49 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.7 | ||

| Piil et al 50 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| Preisler et al 51 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.85 | ||

| Sellars et al 52 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.95 | ||

| Simon et al 53 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.9 | ||

| Thomas et al 54 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.85 | ||

| Yurk et al 55 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.85 | ||

| Zhang and Siminoff56 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.85 |

The summary score for each study is derived by calculating the total score obtained across the 10 items and dividing by 20 (the total possible score).

Table 3.

Mixed-methods studies. Quality assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)

| Criteria for mixed-methods characteristics of mixed-methods studies | |||||||

| Authors | S1. Are there clear research questions? | S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | 5.1. Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed-methods design to address the research question? | 5.2. Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | 5.3. Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | 5.4. Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | 5.5. Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? |

| Kim et al 57 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial |

| Nolan et al 58 | Yes | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial |

| Puts et al 59 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial | Partial | Yes | Partial |

| Criteria for qualitative component of mixed-methods studies | |||||||

| 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | |||

| Kim et al 57 | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Nolan et al 58 | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Puts et al 59 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Criteria for quantitative component of mixed-methods studies | |||||||

| 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? | 4.4. Is the risk of non-response bias low? | 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | |||

| Kim et al 57 | Yes | Partial | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| Nolan et al 58 | Yes | Partial | Yes | Partial | Yes | ||

| Puts et al 59 | Yes | Partial | Can't tell | No | Partial | ||

Rating mixed-methods studies using MMAT involves scoring criteria 1.1–1.5 (qualitative dimension) plus (criteria 2.1–2.5 (quantitative—RCTs) or criteria 3.1–3.5 (quantitative—non-randomised trials) or criteria 4.1–4.5 (quantitative descriptive)) plus criteria 5.1–5.5 (mixed methods).

Criteria 2.1–2.5 or criteria 3.1–3.5 of the MMAT are not listed here because none of these studies are intervention studies.

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

bmjspcare-2022-003525supp001.pdf (143KB, pdf)

Synthesis

We conducted a narrative synthesis15 of the selected studies. A narrative synthesis is commonly used to synthesise studies in a review when studies are heterogenous in design. First, we looked at all evidence in each study which reported on concordance and/or discordance between patients and family caregivers with respect to the focus of the review. We then undertook a preliminary synthesis of the studies. This comprised an exhaustive search in each study for factors and/or processes which related to or helped explain concordance and/or discordance between patients and family caregivers in terms of their preferences for care and/or decision-making in care. Here, we undertook a short textual description for each study and tabulated the findings from each study.15

We then explored relationships in the data by comparing the above findings between and across studies.15 We looked for both similarities and differences in the findings and documented these frequently by engaging in qualitative descriptions of the data.15 We proceeded with expansion of the synthesis via clustering or grouping the findings into categories that best accounted for relationships between the findings and helped answer the aims of the review. The grouping of findings into categories was done collectively by SMS and GF, and the naming of categories was agreed between SMS and GF. The robustness in the synthesis was underpinned by the quality of the studies included in the review and by each study having clearly met the criteria for inclusion.15

Results

Summary of studies

Studies were conducted in Australia,46 47 52 the USA,24 25 32 33 41 55 56 58 Canada,27 28 35 53 59 Denmark,50 UK,23 43 48 54 Ireland,37 South Korea,21 29 30 34 39 40 57 Taiwan,36 38 Singapore,31 Germany,22 26 51 Hong Kong42 and the Netherlands.44 45 49 Quantitative studies reported more on factors associated with concordance and/or discordance while qualitative studies reported on reasons for and/or processes underpinning concordance and discordance. None of the studies aimed from the outset to investigate how patients and family caregivers manage discordance in decision-making.

The studies investigated a range of palliative and end-of-life care domains and contexts, including place of death,23 24 35 36 46 48 54 advance care planning and advance directives,30 39 42 52 53 57 euthanasia,45 artificial nutrition and hydration,22 43 cardiopulmonary resuscitation,27 29 hospice care,21 49 end-of-life care in general (including life-sustaining treatment, life-extending treatment and treatment approaching death)23 25 38 47 and, more broadly, care over the disease trajectory.50 51 Other studies focused more specifically on patients and family caregivers’ preferences, values and judgements with respect to care,28 32–34 37 40 55 and on the family caregiver and the broader family role in the decision-making process.26 31 41 44 56 58 59 Although many studies examined concordance in care preferences and decision-making between patients and family caregivers, only nine studies explicitly focused on discordance, disagreement and/or conflict between patients and family caregivers.26 28 29 31 37 40 41 44 56

Just over half of the studies included had a cancer-only patient population,21–23 25 26 29 30 34 36 38–41 44 50 51 54 56 57 59 while other studies included patient populations for specific diseases including end-stage kidney disease31 32 52 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,33 37 58 or a patient population comprising different progressive neurological diseases.43 The remaining studies recruited patient populations across a spectrum of advanced illness and disease. Care settings included specialist cancer centres, inpatient and outpatient hospital care, specialist palliative care (including hospice care), a nursing home and home care. In a minority of studies, patient participants were recruited through hospice or other dedicated and/or specialist palliative care settings.23 24 42 44–49 54 Family caregivers were primarily spouses or partners, but also included parents, adult children, siblings and friends. Overall, family caregiver participants comprised a combination of significant others and varied both within and across studies. The sample in some studies was limited to patient–caregiver dyads only.21 23–25 29–36 38 40 57 58 The narrative synthesis resulted in the following categorisation of the findings.

Aligned and misaligned preferences and priorities

Several studies investigated patient and family caregiver preferences for care which were focused primarily on patient care, and for the most part, patient end-of-life care.21–25 28 29 34–36 38–41 46–48 53–55 57 Both patients and family caregivers prioritised pain and symptom management.23 24 55 57 However, patients and family caregivers differed with respect to other preferences for care. For example, patients had a strong preference for information to be provided,37 while family caregivers wanted more information about end-of-life care than patients.27 Family caregivers also wished for more healthcare professional engagement and support (including bereavement support) than did patients.37 55 However, patients’ preferences to avoid family caregiver burden and have their personal affairs in order before death could be underestimated by family caregivers.23 24 57

Life-prolonging care versus conservative care was an area of potential conflict between patients and family caregivers. Family caregivers tended to favour more active and life-sustaining treatment options than did patients.29 31 51 52 56 57 59 Some patients preferred a lesser role in decision-making,23 and trusted their family caregivers to make decisions about their care.42 47 However, family caregiver judgements about patient preferences were in some cases incorrect32 33 and related more to family caregiver preferences for care than to the patient’s preferences for care.32 Agreement between patients and family caregivers manifested when patients and family caregivers had knowledge of the disease39 and of treatment and end-of-life care options available to the patient,30 57 and when family caregivers were aware of patients’ preferences for end-of-life care.23 24 43 48 Conversely, discordance was associated with poor communication between patients and family caregivers34 and manifested when patients and family caregivers had insufficient knowledge of the disease and treatment options.28

The familial context to concordance and discordance

Conflict between patients and family caregivers and within the wider family could limit reaching agreement in decision-making about care.40 44 45 47 51 56 Family conflict was in some cases more stressful for patients than the experience of receiving formal care and treatment.51 Nonetheless, patients who preferred a more independent decision-making style were more likely to have their families report that decisions were made in the style that the patient preferred.58 Family caregivers’ family roles shaped concordance and/or discordance between patients and family caregivers.34 36 59 Concordance was higher if family caregivers were spouses,36 and spouse caregivers tended to leave final decisions up to the patient.59 Adult children caregivers, however, preferred a more shared decision-making style and sought more information than spouse caregivers.59 Of note, being an adult child caregiver was associated with concordance with patients for end-of-life care and being a parent caregiver was associated with concordance with patients for disclosure of terminal illness.34

Caregiver commitment versus caregiver burden

Tension between family caregiver commitment to the patient and perceived burden of family caregiving featured in a number of studies.42 46 49 50 54 Dependency on their family caregivers troubled some patients because patients wished not to be a burden on their family caregivers.42 46 49 50 54 57 58 However, family caregivers were committed to providing care to alleviate distress for patients despite the burden of care46 49 50 54 and even desired to limit information to patients to reduce psychological burden for patients.42 Some patients and family caregivers distanced themselves from each other in decision-making to maintain a sense of normality and avoid conflict,46 but such action could limit patient and family caregivers in sharing their concerns with each other.46 50 Indeed, a lack of family caregiver involvement in care could lead to negative experiences for the family caregiver surrounding patient death.55 In many cases, family caregivers wanted to be actively involved in decision-making26 27 47 49 50 54 and supported patients by advocating on their behalf47 and respecting patient autonomy.45 49

Planning end-of-life care and place of death

Discussion surrounding end-of-life care was challenging for both patients and family caregivers.43 45 47 48 56 However, planning ahead for end-of-life care was a useful coping strategy for patients and family caregivers.46 50 Denial of or not engaging in conversation about the impending death acted as a barrier to making decisions about care including end-of-life care.47 51 52 Preference with respect to place of death featured across studies.23 24 35 36 40 46 48 54 Patients and family caregivers were generally consistent on place of death, apart from one study which reported that half of patient–family caregiver dyads disagreed on place of death.35 Higher agreement on place of death was associated with the family caregiver being a spouse,36 the patient having high levels of functional dependency,36 patients and family caregivers having had discussed preferences24 and patients’ own assessment of family caregivers’ knowledge of patient preferences.24 Patient and family caregiver concordance was also more likely if patients and family caregivers agreed on other aspects of end-of-life care.36 Discordance on place of death was more common in situations where family caregiver burden was high23 36 46 and where patients were aware of their prognosis.36 Family caregivers’ lack of knowledge of patient preference for place for death could lead to uncertainty surrounding final decisions48 and some family caregivers regretted when death at home was not possible.54

Managing discordance

No study aimed from the outset to investigate how patients and family caregivers manage discordance in decision-making in care, but some studies did report ways in which patients attempted to manage discordance.42 54 59 In one study, patients chose to forego their own preferences for care in favour of their family caregivers’ preferences for care.59 In another study,42 patients did not consider advance care planning to avoid potential decisional conflict with family caregivers. However, progression of the patient’s illness meant that patients and family caregivers became attuned to the benefit of reaching consensus with respect to end-of-life care decisions.49 50 54 Indeed, negotiation featured when patients and family caregivers jointly decided to move to conservative care or hospice care.49 50

Family caregiver lack of knowledge of patient preferences could foster uncertainty surrounding decisions.48 However, advance care planning and advance directives opened dialogue between patients and family caregivers and in turn facilitated consensus among patients and family caregivers.30 39 52 55 Although prior communication did not necessarily improve family caregivers’ substituted judgement on patients’ own preferences for care,32 advance care planning enabled family caregivers to follow patient wishes even if family caregivers differed in their preferences for care.52 Discussing death and end-of-life care was difficult and could instigate conflict in the family, particularly when there were pre-existing tensions. However, having healthcare professionals to initiate end-of-life care conversations assisted patients and family caregivers in the decision-making process.52 55

Discussion

The focus of this review was to identify key factors and/or processes which underpin or help explain concordance and/or discordance between patients and family caregivers in palliative care with respect to their preferences for care and the decisions they make about care, and to ascertain how they manage their discordance in decision-making pertaining to care. In this review, we found that concordance and/or discordance between patients and family caregivers is shaped by multiple factors, including patient and family caregiver perceptions of caregiver burden,42 46 49 50 54 57 58 patient resistance to burdening family caregivers,42 46 49 50 54 57 58 family roles and relations,34 36 40 44 45 47 51 56 59 family caregiver awareness of patient preference,23 24 32 33 43 48 57 quality of communication between the patient and family caregiver,34 42 46 50 51 patient and family caregiver knowledge of disease and treatment options,28 39 patient and family caregiver coping strategies in the context of advanced illness,46 50 patient and family caregiver judgements about life-prolonging treatment versus end-of-life care29 31 51 52 56 57 59 and by how accepting or not the patient and family caregiver feel towards end-of-life care and the impending death.47–49 52 While discordance between patients and family caregivers is often associated with relational conflict,40 44 45 47 51 56 open discussion and dialogue about patient future care can help move patients and family caregivers towards consensus.30 39 49 50 52 55 All studies were conducted in economically developed countries and so the findings of the review are rooted in this context.

Some key findings in our review resonate with non-palliative care literature on how concordance and discordance manifest between patients and family caregivers in decision-making about care. For example, patients with generic healthcare needs and their family caregivers also feel conflicted about caregiver burden.60 People with non-life-limiting illness and their family caregivers also make decisions in the context of knowledge about disease and treatment options,61 and the strain and demands of living with debilitating illness.62 Open communication between patients with non-life-limiting illness and family caregivers can also promote consensus in decision-making.63 In the context of palliative care, the findings of our review resonate with literature on patient and family caregiver decisional conflict.64 65 Patients and family caregivers in palliative care have capacity to move from periods of decisional conflict to a mutual understanding, in the context of advancing illness and the impending death.64 65 Moreover, patients and family caregivers can accommodate changes in one another’s decision-making roles in end-of-life care.66

Clinical implications

The findings of our review have implications for clinical care and practice. First, the evidence confirms that patients and family caregivers in palliative care have both similar and different preferences for care. However, of key importance is the fact that patients and family caregivers may not necessarily be attuned to one another’s preferences. Attention to patient and family caregiver knowledge of one another’s preferences and to strategies to increase patient and family caregiver mutual understanding could help optimise the decision-making process for both patients and family caregivers. Family caregivers in some cases may favour life-prolonging interventions more than patients, but increased knowledge about patient disease and treatment options can aid discussion about end-of-life care.

Second, the evidence signals that patients and family caregivers in palliative care do have capacity to approximate to one another’s preferences for care, particularly when patients approach end-of-life care, and even when both patients and family caregivers are conflicted about the burden of care. In addition to the provision of formal support to the family caregiver, open discussion between patients, family caregivers and healthcare professionals about concerns in relation to caregiver burden could prove highly beneficial for both patients and family caregivers.

Third, the review highlights the wider impact of family on patients' and family caregivers’ approach to decision-making in palliative care and how the familial relationship between the patient and family caregiver shapes preferences for both patients and family caregivers. Healthcare professionals should consider the impact of the wider family on concordance and/or discordance between patients and family caregivers and the expectations of both patients and family caregivers in the context of their family roles.

Recommendations for research

We identified that patient illness progression and patient and family caregiver recognition of end-of-life care and impending death were key contexts that fostered consensus between patients and family caregivers. Moreover, engaging in dialogue about future care was a key factor that facilitated patients and family caregivers to accommodate to differences in their preferences for care. Systematic reviews have already focused on the effects of advance care planning for people with life-limiting illness.67 68 Research focused on how best to facilitate consensus between patients and family caregivers through advance care planning could prove effective for both patients and family caregivers.

As stated, we did not include intervention-based studies in our review because the focus was on factors related to and/or processes underpinning concordance and/or discordance between patients and family caregivers as opposed to how effective or acceptable interventions were to patients and family caregivers or whether patients and family caregivers differed or not on acceptability of interventions. However, from the evidence reviewed, developing interventions which focus on helping patients and family caregivers understand and accommodate each other’s preferences for care could prove beneficial in alleviating concerns for both patients and family caregivers.

Only in a minority of the studies synthesised were patient participants recruited directly from designated or specialist palliative care facilities, even though this review was limited in its focus to care preferences and decision-making among patients with clearly advancing illness and their family caregivers. Patient recruitment for research can be challenging in palliative care.69 70 Health status of patients can alter suddenly, and the severity of patient illness can in some cases limit patient participation. Nevertheless, more studies that recruit patients and family caregivers from designated or specialist palliative services including hospice care could help pinpoint more clearly how and why patients and family caregivers approximate to each other’s preferences in the context of advancing illness.

Lastly, we found few studies which reported on patient and family caregiver concordance and/or discordance pertaining to formal support and care for family caregivers themselves. Although caregiver burden influenced how both family caregivers and patients approached decision-making, studies focused from the outset on patient care as opposed to formal supports for family caregivers aimed at alleviating burden of care. Family caregivers in palliative care can and do identify their own supportive and care needs,71 72 but few studies have focused on agreement or disagreement between patients and family caregivers on formal support and care available to or used by the family caregiver. Studies focused on patient and family caregiver concordance and/or discordance pertaining to formal support for family caregivers (eg, respite care and counselling) would further our understanding of what underpins concordance and/or discordance in decision-making between patients and family caregivers in palliative care.

Strengths and limitations

This review was limited to original peer-reviewed and full-text published studies between 2000 and 2021. However, including only original full-text studies allowed us to critically appraise the methodological quality of each piece of evidence included. We undertook an exhaustive search of multiple databases using a comprehensive and rigorous search strategy. We did limit the review to patients with clearly advancing illness and disease and our findings might not be transferrable to concordance and/or discordance between patients and family caregivers along the full illness trajectory. Systematic reviews on concordance and discordance between patients and family caregivers in palliative care along the full illness trajectory, or more specifically at key points prior to the advanced stages of patient illness, would further our understanding of relational decision-making between patients and family caregivers in palliative care. More longitudinal qualitative studies on concordance and discordance in decision-making between patients and family caregivers would also illuminate further how patients and family caregivers in palliative care accommodate each other’s preferences for and decisions about care.

Conclusions

Multiple studies in the last two decades have reported on factors associated with concordance and/or discordance in decision-making between patients and family caregivers in palliative care. Concordance and discordance between patients and family caregivers are shaped by multiple factors including family caregiver burden, pre-existing familial roles and relations, quality of communication between patients and family caregivers, patient and family caregiver knowledge of and judgements about care, patient and family caregiver awareness of each other’s preferences for care and how accepting (or not) patients and family caregivers are of end-of-life care. Few studies have focused on how patients and family caregivers manage discordance, but there is evidence that planning future care or simply discussion about patient future care can foster consensus between patients and family caregivers. Further investigation of how patients and family caregivers manage discordance in decision-making and how healthcare professionals can best support or facilitate this is needed. We have identified key factors and/or processes which help explain how concordance and discordance manifest and function between patients and family caregivers in decision-making in palliative care. The findings of the review serve to focus future research on patient and family caregiver interdependence in decision-making in palliative care.

Footnotes

Twitter: @suzie_guerin, @foleyg31

Correction notice: This article has been made open access since it was first published.

Contributors: GF conceived the work and design. SMS and DM formulated the search strategy which was approved by GF. SMS conducted the search and screened studies. GF assisted with screening. SMS extracted the data and both SMS and GF appraised the studies. SMS conducted the synthesis and GF contributed to the synthesis. GF wrote the manuscript with substantial contribution from SMS for methods and findings sections. KR, SMA, LES, AND, NC, JL, RM and SG commented on the design and/or interpretation of the data and made critical contributions to the manuscript. NO’L, MC and MR reviewed the drafts for intellectual content. All authors approved the final draft. GF is responsible for the overall content of the manuscript and acts as guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by an Irish Research Council New Foundations Award awarded to GF (Grant No: IRC/NewFoundations2020). Publication of the work is supported by a Trinity College Dublin MED Research Award awarded to GF.

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in the work conducted.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Not applicable.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Ateş G, Ebenau AF, Busa C, et al. "Never at ease" - family carers within integrated palliative care: a multinational, mixed method study. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:39. 10.1186/s12904-018-0291-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Borgstrom E. Advance care planning: between tools and relational end-of-life care? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:216–7. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dionne-Odom JN, Ejem D, Wells R, et al. How family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer assist with upstream healthcare decision-making: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0212967. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stajduhar KI, Davies B. Variations in and factors influencing family members' decisions for palliative home care. Palliat Med 2005;19:21–32. 10.1191/0269216305pm963oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuosmanen L, Hupli M, Ahtiluoto S, et al. Patient participation in shared decision-making in palliative care - an integrative review. J Clin Nurs 2021;30:3415–28. 10.1111/jocn.15866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C, et al. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:356–76. 10.3322/caac.21490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gudat H, Ohnsorge K, Streeck N, et al. How palliative care patients' feelings of being a burden to others can motivate a wish to die. moral challenges in clinics and families. Bioethics 2019;33:421–30. 10.1111/bioe.12590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hulme C, Carmichael F, Meads D. What about informal carers and families? In: Round J, ed. Care at the end of life: An economic perspective. London: Springer, 2016: 167–76. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burns CM, Abernethy AP, Dal Grande E, et al. Uncovering an invisible network of direct caregivers at the end of life: a population study. Palliat Med 2013;27:608–15. 10.1177/0269216313483664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wiles J, Moeke-Maxwell T, Williams L, et al. Caregivers for people at end of life in advanced age: knowing, doing and negotiating care. Age Ageing 2018;47:887–95. 10.1093/ageing/afy129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alam S, Hannon B, Zimmermann C. Palliative care for family caregivers. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:926–36. 10.1200/JCO.19.00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hudson P, Payne S. Family caregivers and palliative care: current status and agenda for the future. J Palliat Med 2011;14:864–9. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:81–93. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. LeBlanc TW, Bloom N, Wolf SP, et al. Triadic treatment decision-making in advanced cancer: a pilot study of the roles and perceptions of patients, caregivers, and oncologists. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:1197–205. 10.1007/s00520-017-3942-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product of the ESRC methods programme. Lancaster, UK: Lancaster University, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, et al. Redefining palliative Care-A new consensus-based definition. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:754–64. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Covidence systematic review software, veritas health innovation. Melbourne, Australia. Available: www.covidence.org

- 19. Kmet L, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hong QN, Pluye P, bregues S F. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 18 User guide. Montreal, Que: McGill University, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21. An AR, Lee J-K, Yun YH, et al. Terminal cancer patients' and their primary caregivers' attitudes toward hospice/palliative care and their effects on actual utilization: a prospective cohort study. Palliat Med 2014;28:976–85. 10.1177/0269216314531312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bükki J, Unterpaul T, Nübling G, et al. Decision making at the end of life--cancer patients' and their caregivers' views on artificial nutrition and hydration. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:3287–99. 10.1007/s00520-014-2337-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Davies A, Todd J, Bailey F, et al. Good concordance between patients and their non-professional carers about factors associated with a 'good death' and other important end-of-life decisions. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019;9:340–5. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Correspondence between patients' preferences and surrogates' understandings for dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;30:498–509. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gao X, Prigerson HG, Diamond EL, et al. Minor cognitive impairments in cancer patients magnify the effect of caregiver preferences on end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:650–9. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hauke D, Reiter-Theil S, Hoster E, et al. The role of relatives in decisions concerning life-prolonging treatment in patients with end-stage malignant disorders: informants, advocates or surrogate decision-makers? Ann Oncol 2011;22:2667–74. 10.1093/annonc/mdr019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heyland DK, Frank C, Groll D, et al. Understanding cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making: perspectives of seriously ill hospitalized patients and family members. Chest 2006;130:419–28. 10.1378/chest.130.2.419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heyland DK, Heyland R, Dodek P, et al. Discordance between patients' stated values and treatment preferences for end-of-life care: results of a multicentre survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:292–9. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hwang IC, Keam B, Kim YA, et al. Factors related to the differential preference for cardiopulmonary resuscitation between patients with terminal cancer and that of their respective family caregivers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2016;33:20–6. 10.1177/1049909114546546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim J, Park J, Lee MO, et al. Modifiable factors associated with the completion of advance treatment directives in hematologic malignancy: a patient-caregiver dyadic analysis. J Palliat Med 2020;23:611–8. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ozdemir S, Jafar TH, Choong LHL, et al. Family dynamics in a multi-ethnic Asian Society: comparison of elderly CKD patients and their family caregivers experience with medical decision making for managing end stage kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 2019;20:73. 10.1186/s12882-019-1259-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pruchno RA, Lemay EP, Feild L, et al. Spouse as health care proxy for dialysis patients: whose preferences matter? Gerontologist 2005;45:812–9. 10.1093/geront/45.6.812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sharma RK, Hughes MT, Nolan MT, et al. Family understanding of seriously-ill patient preferences for family involvement in healthcare decision making. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:881–6. 10.1007/s11606-011-1717-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shin DW, Cho J, Kim SY, et al. Discordance among patient preferences, caregiver preferences, and caregiver predictions of patient preferences regarding disclosure of terminal status and end-of-life choices. Psychooncology 2015;24:212–9. 10.1002/pon.3631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stajduhar KI, Allan DE, Cohen SR, et al. Preferences for location of death of seriously ill hospitalized patients: perspectives from Canadian patients and their family caregivers. Palliat Med 2008;22:85–8. 10.1177/0269216307084612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tang ST, Chen CC-H, Tang W-R, et al. Determinants of patient-family caregiver congruence on preferred place of death in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:235–45. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tobin K, Maguire S, Corr B, et al. Discrete choice experiment for eliciting preference for health services for patients with ALS and their informal caregivers. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:213. 10.1186/s12913-021-06191-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wen F-H, Chou W-C, Chen J-S, et al. Evolution and predictors of patient-caregiver concordance on states of life-sustaining treatment preferences over terminally ill cancer patients' last six months of life. J Palliat Med 2019;22:25–33. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yoo SH, Lee J, Kang JH, et al. Association of illness understanding with advance care planning and end-of-life care preferences for advanced cancer patients and their family members. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:2959–67. 10.1007/s00520-019-05174-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yun YH, You CH, Lee JS, et al. Understanding disparities in aggressive care preferences between patients with terminal illness and their family members. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;31:513–21. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang AY, Zyzanski SJ, Siminoff LA. Differential patient-caregiver opinions of treatment and care for advanced lung cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1155–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cheung JTK, Au D, Ip AHF, et al. Barriers to advance care planning: a qualitative study of seriously ill Chinese patients and their families. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:80. 10.1186/s12904-020-00587-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Clarke G, Fistein E, Holland A, et al. Planning for an uncertain future in progressive neurological disease: a qualitative study of patient and family decision-making with a focus on eating and drinking. BMC Neurol 2018;18:115. 10.1186/s12883-018-1112-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. de Graaff FM, Francke AL, van den Muijsenbergh METC, et al. Understanding and improving communication and decision-making in palliative care for Turkish and Moroccan immigrants: a multiperspective study. Ethn Health 2012;17:363–84. 10.1080/13557858.2011.645152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dees MK, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekkers WJ, et al. Perspectives of decision-making in requests for euthanasia: a qualitative research among patients, relatives and treating physicians in the Netherlands. Palliat Med 2013;27:27–37. 10.1177/0269216312463259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gerber K, Hayes B, Bryant C. 'It all depends!': a qualitative study of preferences for place of care and place of death in terminally ill patients and their family caregivers. Palliat Med 2019;33:802–11. 10.1177/0269216319845794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gerber K, Lemmon C, Williams S, et al. ‘There for me’: A qualitative study of family communication and decision-making in end-of-life care for older people. Prog Palliat Care 2020;28:354–61. 10.1080/09699260.2020.1767437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Holdsworth L, King A. Preferences for end of life: views of hospice patients, family carers, and community nurse specialists. Int J Palliat Nurs 2011;17:251–5. 10.12968/ijpn.2011.17.5.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Luijkx KG, Schols JMGA. Perceptions of terminally ill patients and family members regarding home and hospice as places of care at the end of life. Eur J Cancer Care 2011;20:577–84. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01228.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Piil K, Juhler M, Jakobsen J, et al. Daily life experiences of patients with a high-grade glioma and their caregivers: a longitudinal exploration of rehabilitation and supportive care needs. J Neurosci Nurs 2015;47:271–84. 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Preisler M, Heuse S, Riemer M, et al. Early integration of palliative cancer care: patients' and caregivers' challenges, treatment preferences, and knowledge of illness and treatment throughout the cancer trajectory. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:921–31. 10.1007/s00520-017-3911-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sellars M, Clayton JM, Morton RL, et al. An interview study of patient and caregiver perspectives on advance care planning in ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;71:216–24. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Simon J, Porterfield P, Bouchal SR, et al. 'Not yet' and 'Just ask': barriers and facilitators to advance care planning--a qualitative descriptive study of the perspectives of seriously ill, older patients and their families. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:54–62. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Thomas C, Morris SM, Clark D. Place of death: preferences among cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:2431–44. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yurk R, Morgan D, Franey S, et al. Understanding the continuum of palliative care for patients and their caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:459–70. 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00503-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang AY, Siminoff LA. The role of the family in treatment decision making by patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2003;30:1022–8. 10.1188/03.ONF.1022-1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kim S, Koh S, Park K, et al. End-Of-Life care decisions using a Korean advance Directive among cancer patient-caregiver dyads. Palliat Support Care 2017;15:77–87. 10.1017/S1478951516000808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nolan MT, Kub J, Hughes MT, et al. Family health care decision making and self-efficacy with patients with ALS at the end of life. Palliat Support Care 2008;6:273–80. 10.1017/S1478951508000412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Puts MTE, Sattar S, McWatters K, et al. Chemotherapy treatment decision-making experiences of older adults with cancer, their family members, oncologists and family physicians: a mixed methods study. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:879–86. 10.1007/s00520-016-3476-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lilleheie I, Debesay J, Bye A, et al. The tension between carrying a burden and feeling like a burden: a qualitative study of informal caregivers' and care recipients' experiences after patient discharge from hospital. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2021;16:1855751. 10.1080/17482631.2020.1855751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Horton DB, Salas J, Wec A, et al. Making decisions about stopping medicines for well-controlled juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a mixed-methods study of patients and caregivers. Arthritis Care Res 2021;73:374–85. 10.1002/acr.24129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brignon M, Vioulac C, Boujut E, et al. Patients and relatives coping with inflammatory arthritis: care teamwork. Health Expect 2020;23:137–47. 10.1111/hex.12982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jeyathevan G, Cameron JI, Craven BC, et al. Re-building relationships after a spinal cord injury: experiences of family caregivers and care recipients. BMC Neurol 2019;19:117. 10.1186/s12883-019-1347-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sulmasy DP, Hughes MT, Yenokyan G, et al. The trial of ascertaining individual preferences for Loved ones' role in end-of-life decisions (tailored) study: a randomized controlled trial to improve surrogate decision making. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;54:455–65. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McCauley R, McQuillan R, Ryan K, et al. Mutual support between patients and family caregivers in palliative care: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2021;35:875–85. 10.1177/0269216321999962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Edwards SB, Olson K, Koop PM, et al. Patient and family caregiver decision making in the context of advanced cancer. Cancer Nurs 2012;35:178–86. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822786f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nishikawa Y, Hiroyama N, Fukahori H, et al. Advance care planning for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;2:CD013022. 10.1002/14651858.CD013022.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zwakman M, Jabbarian LJ, van Delden J, et al. Advance care planning: a systematic review about experiences of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness. Palliat Med 2018;32:1305–21. 10.1177/0269216318784474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hanson LC, Bull J, Wessell K, et al. Strategies to support recruitment of patients with life-limiting illness for research: the palliative care research cooperative group. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:1021–30. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Aoun SM, Nekolaichuk C. Improving the evidence base in palliative care to inform practice and policy: thinking outside the box. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:1222–35. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ullrich A, Marx G, Bergelt C, et al. Supportive care needs and service use during palliative care in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: a prospective longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 2021;29:1303–15. 10.1007/s00520-020-05565-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Aoun S, Deas K, Toye C, et al. Supporting family caregivers to identify their own needs in end-of-life care: qualitative findings from a stepped wedge cluster trial. Palliat Med 2015;29:508–17. 10.1177/0269216314566061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjspcare-2022-003525supp002.pdf (113.5KB, pdf)

bmjspcare-2022-003525supp001.pdf (143KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Not applicable.