Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Care partners are at the forefront of dementia care, yet little is known about patient portal use in the context of dementia diagnosis.

METHODS:

We conducted an observational cohort study of date/time-stamped patient portal use for a 5-year period (October 3, 2017–October 2, 2022) at an academic health system. The cohort consisted of 3170 patients ages 65+ with diagnosed dementia with 2+ visits within 24 months. Message authorship was determined by manual review of 970 threads involving 3065 messages for 279 patients.

RESULTS:

Most (71.20%) older adults with diagnosed dementia were registered portal users but far fewer (10.41%) had a registered care partner with shared access. Care partners authored most (612/970, 63.09%) message threads, overwhelmingly using patient identity credentials (271/279, 97.13%).

DISCUSSION:

The patient portal is used by persons with dementia and their care partners. Organizational efforts that facilitate shared access may benefit the support of persons with dementia and their care partners.

Keywords: caregiver, dementia, electronic communication, electronic health record, patient portal, patient portal messaging, shared access

1 |. BACKGROUND

Family and unpaid care partners are at the forefront of managing dementia.1 Dementia care partners schedule and attend medical visits, coordinate care, and engage in health-care decisions.2–4 The patient portal has a growing and important role in care delivery by enabling asynchronous patient–provider interaction, facilitating timely access to health information, and affording greater convenience in managing health tasks such as scheduling appointments and filling prescriptions.5,6 Persons living with dementia are less able to perform health management tasks electronically,7–9 and are more reliant on care partners to navigate health system demands.3,10 Care partners cite significant unmet information needs during the time of dementia diagnosis,11–13 and the patient portal is a promising tool for facilitating information access.14–16

Many care delivery organizations allow patients to share access to their portal account by designating a care partner(s) who receives their own identity credentials (login/password, termed “shared” [proxy] access”).17 Through shared access, patients may select whether and who electronically interacts with clinicians on their behalf, thus respecting patient information-sharing preferences while supporting care partners through information about patients’ health and a mechanism to navigate health system demands.17 Shared portal access is particularly relevant in dementia care due to the long disease course,18 high rates of co-occurring medical conditions, and the progressive and profoundly disabling nature of needs that necessitate heavy reliance on assistance from others.19 Although both patients5,6 and care partners14 may derive value from interacting with the patient portal, little is known about whether and how it is being used in the care of persons living with dementia, for which targeted quality improvement initiatives and interventional research could be relevant.20

This observational study examines registration and use of the patient portal among older adults with diagnosed dementia and their care partners within a large academic health system’s network of home health and ambulatory medical group practices. We first identify the prevalence of portal registration and degree of portal use among established patients with diagnosed dementia and their care partners. We then comparatively examine the extent to which shared access registration varies across settings that are important in dementia care—in primary care, specialty dementia care, and home health care. We explore growth in portal use over the 5-year period by shared access status. Finally, we perform a text analysis to examine authorship of portal messages within 12 months before and after dementia diagnosis and identify sender relationship when authored by someone other than the patient.

2 |. METHODS

This is an observational study of adults ages ≥ 65 that links patient-level demographic and health characteristics to patient portal interactions and clinical encounters during a 5-year period (between October 3, 2017 and October 2, 2022) at a large academic health system. Our sample includes patients ≥ 65 years with diagnosed dementia who incurred at least two appointments at a clinical practice offering primary care (inclusive of home-based and geriatric primary care), home health, or specialty care relevant to dementia (memory clinic, neurology, and/or geriatric psychiatry). There were no limitations on the date of diagnosed dementia; persons were included whether the diagnosis of dementia occurred prior to 2017 or in 2022. Age was restricted to 65+ because the vast majority of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are older adults. The clinical practices were chosen to maximize the inclusion of patients with dementia who received care at the health system.

Dementia diagnosis was operationalized following Grodstein et al.,21 which requires two or more claims with dementia International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10) codes at least 7 days apart, or one instance from a home health, hospice, rural health clinic, critical access hospital, or federally qualified health center (see Appendix S1 in supporting information for ICD-10 codes). We adapted this definition to additionally include one instance of a dementia diagnosis listed on a patient’s problem list or one claim with an ICD-10 diagnosis from neurology clinics, memory centers, or geriatric psychiatry. This additional criterion required only one instance of a code for dementia, as the problem list is a central component of a person’s electronic health record22 not available in studies using administrative claims only,20 and clinics specializing in dementia care are better equipped to accurately identify this condition. This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB00303190).

2.1 |. Measures

Demographic characteristics include patient age in years, sex (male/female), race (White, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, or other), ethnicity (Hispanic/non-Hispanic), marital status (married, divorced or legally separated, single, widowed), and whether they identified as preferring English language. This information was extracted from the electronic health record.

Recently diagnosed dementia was defined as the 12 months preceding and after diagnosis, from the “noted” date, which is recorded in the problem list, as operationalized above. This measure was limited to the subsample of patients for whom the diagnoses as recorded in the “noted date” occurred within the 5-year observation period.

Measures of patient portal use were computed from date/time-stamped interactions. A person was defined as being a patient portal user if they logged into the patient portal at least once. A shared access user was defined as a person using the patient portal through proxy credentials. Similarly, a “used” portal account was defined as an account in which any user logged in at least once, with logins and sessions defined as described by Di Tosto et al.23 (see Appendix S2 in supporting information). A session was defined by the patient or care partner conducting at least one portal activity other than logging in. We constructed a Portal Activity Metric, defined as the ratio of logins (either patient or care partner with “shared access” credentials, in the numerator) to clinical visits incurred by the patient for a specified observation period (in the denominator), as described previously.24 We differentiated a Patient-Portal Activity Metric, which captured patient logins, from a Shared Access-Portal Activity Metric, which captured logins using shared access credentials. Finally, average length of portal sessions (in minutes) was computed for each patient and shared access portal account based on date/time-stamped login and logout interactions, or, in cases in which there was no logout and the session instead timed out, the time between login and the last user action taken prior to the next login.

2.2 |. Analytic approach

We first examined differences in sociodemographic characteristics and patient portal use by shared access status. We then describe shared access status by settings of care used across the cohort: primary care (at least two visits in 2 years at a primary care clinic, which included home-based and geriatric primary care clinics), home health (a recorded admission to the home health agency operated by the health system), and specialty care (at least two visits at a memory clinic, neurology clinic, and/or geriatric psychiatry clinic in 2 years). Settings of care were not mutually exclusive. The differences in sociodemographic characteristics and patient portal use by shared access status (Shared Access Registered User and No Shared Access Registered User) was assessed by using a chi-squared test for categorical variables and a t test for continuous variables. Normality was checked for all the continuous variables, and the nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used when data were not normally distributed.

We then examined the Portal Activity Metric among active portal users in each year of the 5-year observation period (from October 3, 2017 through October 2, 2022), by shared access status. We calculated the annual compounded growth rate across active portal users to compare change in the Portal Activity Metric from year 1 of the observation period to year 5.

To assess patient portal messaging before and after dementia diagnosis, following Pecina et al.,25 we identified patient- and care partner–initiated portal messages flagged as “medical advice requests” for the subset of patients with diagnosed dementia receiving care in primary care or dementia specialty clinics (specialty clinics included memory clinics, neurology clinics, and geriatric psychiatry clinics, see Appendix S3 in supporting information). The 3065 patient- and/or care partner–initiated messages from 279 unique patient accounts were grouped by “thread.” Each thread was defined by time (e.g., no more than 7 days between related messages) and topic (messages pertaining to the same issue), beginning with a question, update, or request and ending with an acknowledgement or response from the clinical team, or when no further messaging occurred. A subset of 500 messages from 41 portal accounts was initially coded by two team members blinded to the other’s coding decisions to ensure consistency. As no differences were found in decisions by our key indicator of message authorship (care partner vs. patient), remaining messages were coded by one team member and reviewed/adjudicated by another.

For each thread, we identified the total number of messages and the number of messages until the author identity was revealed. We determined if the author was someone other than the patient based on: (1) whether the patient was referred to in the third person, (2) the message was signed using a name other than the patient, or (3) the message author identified themselves using their name and/or relationship to the patient. For messages authored by persons other than the patient, we identified sender relationship if possible (e.g., child, spouse, grandchild of patient).

3 |. RESULTS

The sample is described in Table 1. The cohort includes 3170 older adults, of whom more than half (63.63%) were female, married (45.39%), and White (62.03%), with an average age of 82.80 (standard deviation 8.27). The majority were registered for the patient portal (71.20%), and 330 (10.41%) had at least one registered shared access user. Most registered patient portal accounts (91.9%, 2075/2257) were used, indicating that a patient logged on at least once during the 5-year observation period.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics by shared access use.

| Total | Shared access user | No shared access user | Chi Sq or Z, P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N; column % | N; column % | N; column % | ||

| Overall sample size | 3170 | 330 | 2840 | N/A |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 82.80 (8.27) | 82.57 (8.31) | 82.83 (8.27) | Z = 0.61, P = 0.54 |

| Female sex | 2017; 63.63% | 205; 62.12% | 1812; 63.80% | Chi2 = 0.36, P = 0.55 |

| Race | Chi2 = 8.73, P = 0.07 | |||

| Black | 957; 30.49% | 88; 26.91% | 869; 30.69% | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 94; 2.99% | 11; 3.36% | 84; 2.99% | |

| Other | 141; 4.49% | 28; 8.48% | 116; 4.08% | |

| White | 1947; 62.03% | 204; 62.39% | 1743; 61.98% | |

| Hispanic | 40; 1.28% | 8; 2.43% | 41; 1.45% | Chi2 = 2.28; P = 0.32 |

| Married/partnered | 1439; 45.39% | 155; 46.97% | 1284; 45.21% | Chi2 = 6.70, P = 0.14 |

| Prefers English | 3055; 96.37% | 318; 96.36% | 2737; 96.37% | Chi2 = 0.00, P = 0.99 |

| Patient portal registration | ||||

| Patient registered | 2257; 71.20% | 330; 100% | 1927; 68.03% | N/A |

| Care partner registered | 330; 10.41% | 330; 100% | 0; 0% | N/A |

| Patient portal use | ||||

| Patient portal userb | 2075; 65.46% | 313; 94.85% | 1895; 66.73% | Chi2 = 110.62 P < 0.001* |

| Portal activity metricc (SD) | 12.45 (16.12) | 19.22 (20.97) | 11.25 (14.82) | Z = −14.70, P < 0.001 |

| Mean number of sessionsd (SD) | 131.17 (319.43) | 341.32 (439.96) | 164.33 (348.46) | Z = −10.25, P < 0.001 |

| Average session length in minutesd (SD) | 3.60 (1.20) | 3.81 (1.13) | 3.57 (1.20) | Z = −11.98, P < 0.001 |

| Average number of messages sente (SD) | 28.77 (57.73) | 47.56 (111.73) | 27.42 (40.29) | Z = −6.64, P < 0.001 |

| Health care use | ||||

| Number of encounters | 75.83 (78.30) | 74.34 (66.00) | 76.00 (79.62) | Z = −0.94, P = 0.35 |

| Primary care patientf | 2326; 73.38% | 287; 86.97% | 2039; 71.80% | Chi Sq = 34.84, P < 0.001 |

| Recorded home health admission | 1758; 55.46% | 146; 44.24% | 1612; 56.76% | Chi Sq = 18.76, P < 0.001 |

| Specialty clinic patientg | 257; 8.12% | 31; 9.42% | 226; 7.26% | Chi Sq = 0.83, P = 0.36 |

Abbreviations: N/A, not applicable; SD, standard deviation.

Tests of statistical significance reflect results from testing the differences in sociodemographic characteristics and patient portal use by shared access status (Shared Access Registered User and No Shared Access Registered User) was assessed by using a chi-squared test for categorical variables and a t test for continuous variables. Normality was checked for all the continuous variables, and the nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used when data were not normally distributed.

A user is defined as logging in at least once to the patient portal over the 5-year time span.

Portal Activity Metric is operationalized as the number of logins (either patient or care partner with “shared access” credentials) divided by number of encounters incurred by each patient over the 5-year period.

Metrics are computed for the 32,501 persons with an active patient portal over the 5-year time span.

Messaging is limited to “medical advice request” category, reflecting those initiated by a patient or their registered proxy.

A primary care patient was defined as someone with two visits in 2 years at a primary care clinic.

A specialty clinic patient was defined as someone with at least two visits in 2 years to a clinic specializing in dementia care (memory clinic, neurology clinic, or geriatric psychiatry).

3.1 |. Patient characteristics and portal use by shared access status

There were not statistically significant differences in age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, or preferred language spoken by shared access status among patients with dementia. Patients with (vs. without) a shared access user had a higher level of patient portal activity, as measured by the Portal Activity Metric (19.22 vs. 11.25, P < 0.001) and were more likely to be a portal user (94.85% vs. 66.73%, P < 0.001). Among patients with a shared access user, the Patient-Portal Activity Metric was 11.73 (15.78), and Shared Access-Portal Activity Metric was 9.58 (14.09). Patients with a shared access user had a higher number of messages originating through portal accounts (47.56 vs. 27.42, P < 0.001). Of patients with a registered care partner, shared access users sent an average of 24.64 messages and patient users sent an average of 31.13 messages (not depicted in Table 1). The average length of portal sessions was slightly longer for patients with (vs. without) a shared access user (3.81 vs. 3.57 minutes, P < 0.001). Shared access users’ sessions were an average of 3.69 minutes (not depicted in Table 1).

Patients with a shared access user had a similar number of clinical encounters (76.00 vs. 74.34, P = 0.35) and a similar likelihood of being a patient at a clinic specializing in dementia care (9.42% vs. 7.97%, P = 0.36). Patients with a shared access user were more likely to be a primary care patient (86.97% vs. 71.80%, P < 0.001) and less likely to have been cared for within home health (44.24% vs. 56.76%, P < 0.001).

3.2 |. Patient portal activity by shared access status over time

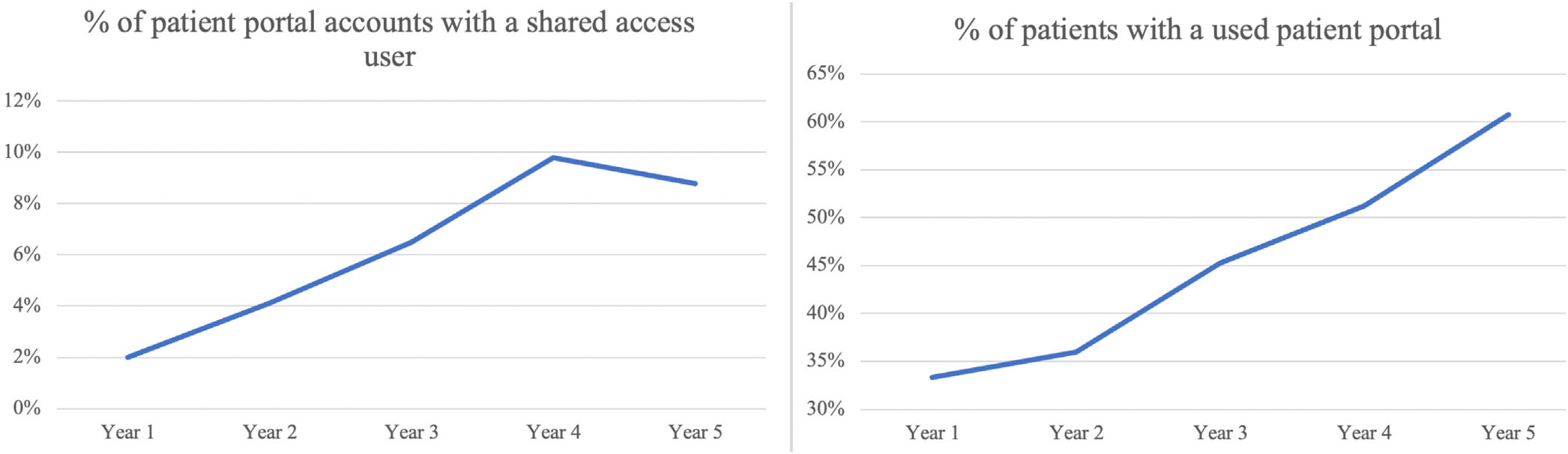

Patient portal activity increased during the observation period among patients with and without a shared access user (Table 2). The pace of increased portal activity was greater for those with (vs. without) a shared access user (24.15% and 15.42% annual compounded growth, respectively). Among patients with a registered shared access user, the annual compounded growth rate was similar for the Shared Access-Portal Activity Metric (11.34%) and Patient-Portal Activity Metric (11.87%). The percentage of portal accounts with a registered care partner user increased 4-fold over the 5-year observation period but remained low at both time points (from 2.4% in Year 1 to 8.8% in Year 5, Figure 1, left panel) while the percentage of patients who used the patient portal at least once in each year increased 2-fold over the 5-year observation period from 33.3% to 60.8% (Figure 1, right panel).

TABLE 2.

Portal activity by year and compounded annual growth rate.

| Patients with a registered shared access user |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Overall cohort | Overall | Patient users | Shared access users | No shared access user |

| Portal activity metrica | Mean, (SD), Nb | ||||

| Year 1c | 3.56 (4.69) N = 949 | 4.05 (4.56) N = 162 | 3.82 N = 142 | 4.17 (5.18) N = 27 | 3.46 (4.72) N = 787 |

| Year 2 | 3.80 (4.73) N = 1131 | 4.43 (5.09) N = 193 | 4.25 (4.84) N = 165 | 3.27 (5.23) N = 47 | 3.68 (4.65) N = 938 |

| Year 3 | 4.99 (6.52) N = 1426 | 5.94 (5.93) N = 234 | 5.07 (5.32) N = 194 | 4.39 (4.98) N = 93 | 4.79 (6.61) N = 1192 |

| Year 4 | 6.37 (7.83) N = 1621 | 8.48 (8.87) N = 251 | 6.14 (7.24) N = 197 | 5.71 (7.83) N = 161 | 5.99 (7.57) N = 1370 |

| Year 5 | 6.68 (9.06) N = 1476 | 9.62 (10.99) N = 226 | 5.87 (7.26) N = 179 | 6.53 (10.00) N = 172 | 6.14 (8.56) N = 1250 |

| Compounded annual growth rate | 17.04% | 24.15% | 11.34% | 11.87% | 15.42% |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Portal Activity Metric is here operationalized as the number of sessions divided by number of encounters incurred by each patient with an active patient portal within a 12-month period.

N refers to the number patient portal users for each cohort year.

Each year is defined by cohort time (i.e., October 3, 2017–October 3, 2018 = Year 1; October 4, 2021–October 3, 2022 = Year 5).

FIGURE 1.

Percent of persons with used shared access accounts and a used patient portal by year among persons with dementia. The percent of used patient portal accounts with a shared access user (right panel) each year, and the percent of persons who used the patient portal each year (left panel) among persons with dementia. Used patient portal accounts are defined as an account with a user (shared access or patient) who logged in at least one time within the year. Each year is categorized by cohort time (i.e., October 3, 2017–October 3, 2018= Year 1; October 4, 2021–October 3, 2022 = Year 5).

3.3 |. Authorship of patient portal messages involving patients with recently diagnosed dementia

From 3065 messages sent from the portal accounts of 279 patients within 12 months of dementia diagnosis, 970 message threads were identified, with an average length of 3.12 messages (range: 1–18 messages; Table 3). More than half (n = 612/970; 63.09%) of message threads were authored by a care partner, most often a son or daughter (n = 393/612; 64.22%). In most threads (n = 885/970; 91.24%), the author (patient or care partner) identified themselves in the first message. In messages authored by a care partner, relationship (n = 441/612; 72.06%) and name (n = 490/612; 80.07%) were less often provided.

TABLE 3.

Patient portal messages authored from accounts of persons with diagnosed dementia.

| Message thread characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Account type | |

| Shared access | 8; 2.87% |

| Patient | 271; 97.13% |

| Sender | |

| Patient | 304; 31.34% |

| Care partner | 612; 63.09% |

| Both | 12; 1.24% |

| Unclear | 40; 4.12% |

| Care partner relationshipa | |

| Spouse | 46; 7.52% |

| Adult child (including significant other of child) | 393; 64.22% |

| Other family | 15; 2.45% |

| Unclear | 153; 25.00% |

| Other | 11; 1.80% |

| Identity of sender (care partner or patient) evident in first message of thread | 885; 91.24% |

| Sender relationship included in first message of threada | 441; 72.06% |

| Sender name identified in threada | 490; 80.07% |

| Average thread length | 3.12 messages |

| Analysis of manually coded portal messages sent within 12 months of dementia diagnosis. The sample includes 970 threads of 3065 messages for 279 patients with diagnosed dementia. |

The denominator is a subset of 612 threads sent from a care partner.

4 |. DISCUSSION

This analysis, involving 5 years of patient portal interactions for older adults with dementia under the care of clinicians practicing at a large academic health system, finds higher portal activity among persons with a shared access user. Importantly, we find that registration for the portal and portal activity are increasing, both for patients and shared access users. That care partners’ portal activity approaches similar levels to that of patients suggests the value of patient portals in meeting the information and communication needs of care partners in this population. Receiving care in a primary care setting was associated with shared access use, but number of encounters, home health admission, and receiving care at a clinic specializing in dementia care was not. Importantly, we found that care partners authored most messages sent from portal accounts of patients with diagnosed dementia, overwhelmingly using patient identity credentials. Collectively, study results portray a compelling need and opportunity to better support persons with dementia and their care partners through consumer-oriented health information technologies such as the patient portal.

Study findings have important implications for systems-level initiatives to improve dementia care quality26,27 and reinforce the need to establish best practices to proactively identify, engage, and support care partners in dementia care.28 As dementia progresses, attending in-person health care visits can become more challenging, and the patient portal may facilitate longitudinal care through telehealth, asynchronous communication, and tailored support.15,29 For example, best practice principles in dementia care call for the provision of educational resources to care partners, and conducting screening for home safety, driving, and pain,27 all of which could be facilitated in part or in full through the portal. Dementia Care Planning26 and the Medicare Annual Wellness Visits30 afford clinician reimbursement opportunities for encounters of longer duration that are relevant to high quality dementia care yet underused,30 that could be supported through portal interactions.5,31,32 For example, care partner identification and support are components of Dementia Care Planning that could be facilitated through portal-mediated questionnaires that proactively identify care partners as well as their dementia knowledge and support needs.20

Our study advances the development of a Portal Activity Metric to standardize analyses of patient engagement in portal-based interactions by reporting activity relative to the intensity of encounters within a given health system. One systematic review found that few analyses of patient portal use have captured whether or to what degree patients have been under active clinical care,33 which is an important factor in contextualizing portal use as well as staff and clinician time.34,35 In this sample, about 71% of patients were portal users but it is difficult to compare this finding to the literature as we examined persons who were under active clinical care. The 5-year observation period encompasses the COVID-19 pandemic when many visits occurred over video and necessitated a patient portal,36,37 which may explain some of the growth observed in portal use. Understanding how high-need subpopulations, such as persons with dementia, engage with the portal is important in driving reimbursement and quality models that recognize and support portal use.38 The development of a Portal Activity Metric enables a more nuanced understanding of portal use that accounts for overall intensity of care delivery interactions with the patient portal, and may prove useful to understanding variability in portal-based activity across subpopulations, service delivery lines, and care delivery initiatives that seek to mobilize patient or family engagement in care.

Our findings reinforce prior reports of low shared (proxy) portal registration,17,25 and care partners’ reliance on patient credentials.14 Low shared access registration persisted across ethnic and racial groups, and those who preferred a language other than English. Little attention has been directed toward identifying organizational best practices for implementing shared portal access functionality: where offered, awareness is low, with cumbersome registration processes that are not well understood.39 A recent scoping review found < 3% of registered adult portal users have registered a care partner with “shared access” to their account, and that as a result, they most often rely on patient identity credentials.14 Sharing credentials can lead to privacy problems by revealing more information than desired by the patient,40 mistakes when clinical care teams do not know with whom they are interacting electronically,17,39,41 and the need to retract portal-mediated legal documents completed by someone other than the patient.42

More deliberative and systematic attention to registering, engaging, and supporting care partners through the patient portal is aligned with the Age-Friendly Health System initiative and the goal of equitable access to health information techologies.43 Efforts to advance dementia care in real-world settings could significantly benefit from formalizing care partner engagement through the patient portal, as care partners play a critical role in monitoring and communicating for the patient from the initial detection of dementia through end-of-life care.44 Adapting organizational strategies directed at increases in patients’ portal registration and use45 for care partners, including staff education on the importance of shared access, administrative support to facilitate proxy registration,14 and provider engagement to encourage shared access, are potential steps to increase patient portal access among shared access users. Novel strategies to automate responses to patient messages through artificial intelligence46,47 are also a potential avenue; for example, artificial intelligence could recognize when a message is sent from a care partner and send a request for the care partner to register for shared access and/or send relevant resources. Such strategies could reduce clinical staff burden. Organizational, vendor, and policy-related efforts directed at awareness and outreach to explicitly engage care partners with shared access identity credentials will be important to improving equitable access to the patient portal48,49 so all patients, including those with complex health needs such as dementia, can benefit.

4.1 |. Limitations

It is important to note the findings of this study in the context of its limitations. Secondary use of electronic medical record data for research is inherently subject to missing and inaccurate data.50 While the study team took steps to ensure the patient portal accounts reflected active clinic patients, it is possible that patients received routine care elsewhere during the observation period and that some patient accounts categorized as unused involved patients using a portal at another health system. The study focuses on the subset of patients with diagnosed dementia, which is known to be misclassified and underdiagnosed.51 Furthermore, this study involves electronic medical record data from a single health system, which limits its generalizability.

5 |. CONCLUSION

Dementia poses complex challenges to treatment and quality of care for not only dementia but also comorbid medical conditions.6 At the same time, health-care communication and coordination increasingly rely on electronic interactions that include the patient portal.12 Although care partners are widely recognized as having a foundational role in facilitating medical care for persons with dementia, our study is the first to examine patient portal activity in this population.1 This study establishes that persons with dementia and their care partners are active users of the patient portal, and that system-level organizational initiatives are needed to identify and better support care partners. Increasing reliance on patient portal-based communication, including as a means of collecting patient-generated health information and legal documents,5,25 reinforce the importance of our findings for health system–level initiatives that promote awareness and use of care partner identity credentials for transparent, secure, and accurate electronic interactions.43,10

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic Review: In a scoping review of the literature, we found that care partners typically access the patient portal using patient identity credentials, including when messaging with clinicians. No studies were identified that reported on patient portal use among patients with dementia and their care partners.

Interpretation: We find that most patients with diagnosed dementia are registered portal users, but few have a registered care partner with shared access. We find that care partner messaging most frequently occurs using the patient credentials, rather than proxy credentials.

Future Directions: Organizational initiatives should recognize and support the needs of persons with dementia and their care partners by encouraging awareness, registration, and use of care partners’ proper identity credentials.

Highlights.

Patient portal registration and use has been increasing among persons with diagnosed dementia.

Two thirds of secure messages from portal accounts of patients with diagnosed dementia were identified as being authored by care partners, primarily using patient login credentials.

Care partners who accessed the patient portal using their own identity credentials through shared access demonstrate similar levels of activity to patients without dementia.

Organizational initiatives should recognize and support the needs of persons with dementia and their care partners by encouraging awareness, registration, and use of proper identity credentials, including shared, or proxy, portal access.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Daniel L. Scerpella, MPH, and Danielle Peereboom, MPH, who both helped coordinate the extraction of data which this study uses. This work was supported by NIH NIA grant R35AG072310, Consumer Health Information Technology to Engage and Support ADRD Caregivers: Research Program to Address ADRD Implementation Milestone 13.I. A. Wec and D. Powell were supported by NIH/NIA T32AG066576 and the Hopkins’ Economics of Alzheimer’s Disease and Services (HEADS) Center of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) award number P30AG066587. H. Amjad was supported by NIH/NIA K23 AG064036. S. Nothelle was supported by NIH/NIA K23 AG073207. A. Green was supported by NIH/NIA R01AG077011. The funder played no role in any aspect of the manuscript, including the review idea, design, analysis, or interpretation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Author disclosures are available in the supporting information.

CONSENT STATEMENT

Informed consent was not necessary as this study involved secondary data. This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB00303190).

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Wolff JL. The disproportionate impact of dementia on family and unpaid caregiving to older adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1642–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedman VA, Patterson SE, Cornman JC, Wolff JL. A day in the life of caregivers to older adults with and without dementia: comparisons of care time and emotional health. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(9):1650–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riffin C, Van Ness PH, Wolff JL. Fried T. family and other unpaid caregivers and older adults with and without dementia and disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1821–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt KL, Lingler JH, Schulz R. Verbal communication among Alzheimer’s disease patients, their caregivers, and primary care physicians during primary care office visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):197–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han HR, Gleason KT, Sun CA, et al. Using patient portals to improve patient outcomes: systematic review. JMIR Hum Factors. 2019;6(4):e15038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otte-Trojel T, de Bont A, Rundall TG, van de Klundert J. How outcomes are achieved through patient portals: a realist review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):751–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osborn CY, Mayberry LS, Wallston KA, Johnson KB, Elasy TA. Understanding patient portal use: implications for medication management. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(7):e133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taha J, Czaja SJ, Sharit J, Morrow DG. Factors affecting usage of a personal health record (PHR) to manage health. Psychol Aging. 2013;28(4):1124–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czaja SJ, Sharit J, Lee CC, et al. Factors influencing use of an e-health website in a community sample of older adults. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(2):277–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff JL, Darer JD, Larsen KL. Family caregivers and consumer health information technology. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):117–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khanassov V, Vedel I. Family physician-case manager collaboration and needs of patients with dementia and their caregivers: a systematic mixed studies review. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):166–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shafir A, Ritchie CS, Garrett SB, et al. Captive by the uncertainty”-experiences with anticipatory guidance for people living with dementia and their caregivers at a specialty dementia clinic. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;86(2):787–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yates J, Stanyon M, Samra R. Challenges in disclosing and receiving a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic review of practice from the perspectives of people with dementia, carers, and healthcare professionals. Int Psychogeriatr. 2021;33(11):1161–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gleason KT, Peereboom D, Wec A, Wolff JL. Patient portals to support care partner engagement in adolescent and adult populations: a scoping review. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(12):e2248696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodgson J, Welch M, Tucker E, Forbes T, Pye J. Utilization of EHR to improve support person engagement in health care for patients with chronic conditions. J Patient Exp. 2022;9:23743735221077528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakaguchi-Tang DK, Bosold AL, Choi YK, Turner AM. Patient portal use and experience among older adults: systematic review. JMIR Med Inform. 2017;5(4):e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff JL, Berger A, Clarke D, et al. Patients, care partners, and shared access to the patient portal: online practices at an integrated health system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(6):1150–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(2):P126–P137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolff JL, DesRoches CM, Amjad H, et al. Catalyzing dementia care through the learning health system and consumer health information technology. Alzheimer Dement: J Alzheimer Assoc. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grodstein F, Chang CH, Capuano AW, et al. Identification of dementia in recent medicare claims data, compared with rigorous clinical assessments. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77(6):1272–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klappe ES, de Keizer NF, Cornet R. Factors influencing problem list use in electronic health records-application of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Appl Clin Inform. 2020;11(3):415–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Tosto G, McAlearney AS, Fareed N, Huerta TR. Metrics for outpatient portal use based on log file analysis: algorithm development. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e16849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gleason KT, Wu M, Wec A, Powell DS, Zhang T, Wolff JL. Patient portal use among older adults with diagnosed dementia: findings from a cohort study of electronic medical record data. JAMA Intern Med. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pecina J, Duvall MJ. North F. frequency of and factors associated with care partner proxy interaction with health care teams using patient portal accounts. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(11):1368–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borson S, Chodosh J, Cordell C, et al. Innovation in care for individuals with cognitive impairment: can reimbursement policy spread best practices? Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(10):1168–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schultz SK, Llorente MD, Sanders AE, et al. Quality improvement in dementia care: dementia management quality measurement set 2018 implementation update. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(2):175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larson EB, Stroud C. Meeting the challenge of caring for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers: a report from the national academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine. JAMA. 2021;325(18):1831–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tieu L, Sarkar U, Schillinger D, et al. Barriers and facilitators to online portal use among patients and caregivers in a safety net health care system: a qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(12):e275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thunell JA, Jacobson M, Joe EB, Zissimopoulos JM. Medicare’s Annual Wellness Visit and diagnoses of dementias and cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;14(1):e12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lum HD, Brungardt A, Jordan SR, et al. Design and implementation of patient portal-based advance care planning tools. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(1):112–117. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyles CR, Nelson EC, Frampton S, Dykes PC, Cemballi AG, Sarkar U. Using electronic health record portals to improve patient engagement: research priorities and best practices. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11 Suppl):S123–S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beal LL, Kolman JM, Jones SL, Khleif A, Menser T. Quantifying patient portal use: systematic review of utilization metrics. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e23493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang M, Fan J, Prigge J, Shah ND, Costello BA, Yao L. Characterizing patient-clinician communication in secure medical messages: retrospective study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(1):e17273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.North F, Luhman KE, Mallmann EA, et al. A retrospective analysis of provider-to-patient secure messages: how much are they increasing, who is doing the work, and is the work happening after hours? JMIR Med Inform. 2020;8(7):e16521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gray SM, Franke T, Sims-Gould J, McKay HA. Rapidly adapting an effective health promoting intervention for older adults-choose to move-for virtual delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang M, Khurana A, Mastorakos G, et al. Patient portal messaging for asynchronous virtual care during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective analysis. JMIR Hum Factors. 2022;9(2):e35187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolitz E, Smith A, Taylor O, Mauskar MM, Goff H. Considerable unreimbursed medical care is delivered through electronic patient portals: a retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(4):1105–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolff JL, Dukhanin V, Burgdorf JG, DesRoches CM. Shared access to patient portals for older adults: implications for privacy and digital health equity. JMIR Aging. 2022;5(2):e34628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latulipe C, Mazumder SF, Wilson RKW, et al. Security and privacy risks associated with adult patient portal accounts in US hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):845–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackson SL, Shucard H, Liao JM, et al. Care partners reading patients’ visit notes via patient portals: characteristics and perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(2):290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DesRoches CM, Walker J, Delbanco T. Care partners and patient portals-faulty access, threats to privacy, and ample opportunity. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):850–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fulmer T, Mate KS, Berman A. The age-friendly health system imperative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):22–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caceres BA, Frank MO, Jun J, Martelly MT, Sadarangani T, de Sales PC. Family caregivers of patients with frontotemporal dementia: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;55:71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grossman LV, Masterson Creber RM, Benda NC, Wright D, Vawdrey DK, Ancker JS. Interventions to increase patient portal use in vulnerable populations: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8–9):855–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chew HSJ. The use of artificial intelligence-based conversational agents (chatbots) for weight loss: scoping review and practical recommendations. JMIR Med Inform. 2022;10(4):e32578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schachner T, Keller R, F VWangenheim. Artificial intelligence-based conversational agents for chronic conditions: systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e20701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mayberry LS, Kripalani S, Rothman RL, Osborn CY. Bridging the digital divide in diabetes: family support and implications for health literacy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(10):1005–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drazich BF, Nyikadzino Y, Gleason KT. A program to improve digital access and literacy among community stakeholders: cohort study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(11):e30605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nair S, Hsu D, Celi LA, Challenges and opportunities in secondary analyses of electronic health record data. In secondary analysis of electronic health records. Cham (CH). Springer; 2016:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amjad H, Roth DL, Sheehan OC, Lyketsos CG, Wolff JL, Samus QM. Underdiagnosis of dementia: an observational study of patterns in diagnosis and awareness in US older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1131–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.