Abstract

Dermacentor nuttalli, a member of family Ixodidae and genus Dermacentor, is predominantly found in North Asia. It transmits various pathogens of human and animal diseases, such as Lymphocytic choriomeningitis mammarenavirus and Brucella ovis, leading to severe symptoms in patients and posing serious hazards to livestock husbandry. To profile pathogen abundances of wild D. nuttalli, metagenomic sequencing was performed of four field-collected tick samples, revealing that Rickettsia, Streptomyces, and Pseudomonas were the most abundant bacterial genera in D. nuttalli. Specifically, four nearly complete Rickettsia genomes were assembled, closely relative to Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii. Then, a comprehensive meta-analysis was performed to evaluate its potential threats based on detected pathogens and geographical distribution positions reported in literature, reference books, related websites, and field surveys. At least 48 pathogens were identified, including 20 species of bacteria, seven species of eukaryota, and 21 species of virus. Notably, Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii, Coxiella burnetii, and Brucella ovis displayed remarkably high positivity rates, which were known to cause infectious diseases in both humans and livestock. Currently, the primary distribution of D. nuttalli spans China, Mongolia, and Russia. However, an additional 14 countries in Asia and America that may also be affected by D. nuttalli were identified in our niche model, despite no previous reports of its presence in these areas. This study provides comprehensive data and analysis on the pathogens carried by D. nuttalli, along with documented and potential distribution, suggesting an emerging threat to public health and animal husbandry. Therefore, there is a need for heightened surveillance and thorough investigation of D. nuttalli.

Keywords: Dermacentor nuttalli, Pathogens, Meta-analysis, Global distribution, Niche modeling

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Assembled four near-complete Rickettsia genomes.

-

•

Meta-Analysis of D. nuttalli's threats based on detected pathogens and distribution.

-

•

Detected at least 48 pathogens in D. nuttalli.

-

•

D. nuttalli may impact 14 additional countries.

1. Introduction

Dermacentor nuttalli, belonging to the family Ixodidae and genus Dermacentor, is one of the most widely distributed Dermacentor tick species in North Asia. D. nuttalli is commonly found in grasslands, forests, and shrublands and carries a variety of pathogens that can be transmitted to humans and animals. Studies have shown that it carries and transmits pathogens such as Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Brucella spp., and tick-borne encephalitis virus (Chen et al., 2010; Javkhlan G et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2020; Gui et al., 2021). These pathogens can cause diseases such as tick-borne lymphadenopathy, anaplasmosis, brucellosis, and tick-borne encephalitis, which can be severe and fatal in some cases. Moreover, D. nuttalli also carries multiple pathogenic pathogens to animals, like Theileria Orientalis, an economically important parasite of cattle (Watts et al., 2016; Fischer et al., 2020). Infected animals may experience reduced productivity, weight loss, and reproductive issues, causing substantial economic losses in the livestock industry (Schnittger et al., 2022; Iduu et al., 2023). Given the substantial risks posed by D. nuttalli to human and animal health, comprehensive research into its pathogen carriage and global distribution is imperative.

Ecological niche modeling (ENM), a method for reconstructing species-environment relationships, is instrumental in identifying potential geographical habitats of species (Valencia-Rodríguez et al., 2021). Maximum Entropy Modeling (Maxent) is one of the best ENMs, based on a comprehensive review of 17 different methods (Elith et al., 2010). Maxent has been widely used in predicting the distribution and associated vector-borne diseases of many species including birds, mosquitoes, as well as ticks (Peterson and Pape, 2007; Foley et al., 2008; Larson et al., 2010; St John et al., 2016; Martin et al., 2022). Climate change might affect the distribution range of hosts and further impact the transmission of tick-borne diseases (Bouchard et al., 2019; Ogden and Lindsay, 2016; Gilbert, 2021). Therefore, it is feasible to predict the distribution of ticks according to environmental factors.

To evaluate the potential public health threats of D. nuttalli, this study first performed metagenome sequencing of field-collected samples to investigate the pathogen it carried. Then, we conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis to investigate associated pathogens and known geographic distributions. Finally, we predicted its potential habitats using the ENM model based on meteorology, land cover type, and other environmental factors to unveil its potential distribution.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection

Our group conducted field surveys in provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities of mainland China. All ticks were collected in Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Qinghai, Xinjiang and Liaoning (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Table S1). During the field survey, ticks were collected by dragging a white flannel flag horizontally through grass or shrubs. The flag surface was checked every 20 m, and ticks attached to the flag surface were collected. Parasitic ticks were collected from the body surface of Ovis aries using curved tweezers. The ticks were classified based on the characteristics of cornua of basis capituli, dorsal spur of trochanter Ⅰ, and palp article Ⅲ (Sun). Morphological identification and categorization of the ticks were conducted under a stereomicroscope. After identification, the ticks were stored at −80 °C.

2.2. Metagenomic library construction, sequencing and taxonomy profiling

Four adult ticks were selected for metagenome sequencing and they were all from the same region in Xinjiang to capture variability of the local microbe profile. The four adult ticks (three males and one female) were thoroughly surface sterilized with 0.1% neosporin for 15 min, 75% alcohol for 10 min, and PBS (twice) for 5 min, respectively. And then genomic DNA was extracted using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, USA). Libraries were prepared using the NEBNext UltraTM DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA) following the manufacturer's recommendations, and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Upon acquiring the metagenomic sequencing data of D. nuttalli, a series of bioinformatics tools were employed to process and analyze the data. Initially, Kraken v2.0.7-beta (Wood et al., 2019) was used to categorize the reads in samples. The sequencing data were assembled using SPAdes v3.13.0 (Bankevich et al., 2012) followed by binning using the MetaBAT v2.15 (Kang et al., 2019) to assemble the pathogen genome. Subsequently, CheckM (Parks et al., 2015) was used to assess the binning results. Busco v4.1.2 (Simão et al., 2015) was used to evaluate the completeness of the assembly with parameters -l rickettsiales_odb10. Then, Prokka v1.14.6 (Seemann, 2014) was used to annotate the genome, and OrthoFinder v2.5.5 (Emms and Kelly, 2019) was used to get single-copy orthologue sequences. Finally, MAFFT v7.520 (Katoh et al., 2002) and IQ-TREE v2.2.2.7 (Minh et al., 2020) were used to generate a phylogenomic tree.

2.3. Data collection

To gain a deeper understanding of D. nuttalli, we conducted separate meta-analyses on its associated pathogens and its current distribution. The database of D. nuttalli was constructed from four sources, including field surveys, literature review, a reference book, and an online biodiversity database (Global Biodiversity Information Facility, GBIF, https://www.gbif.org). The field surveys were previously described in Section 2.1. Three online databases were used to search for literature. “Dermacentor nuttalli” was used to search for relative literature in PubMed, while its Chinese equivalent was used in China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and the WanFang Database. The published articles we collected spanned from 1983 to 2022. Articles reporting the exact collection locations (at the county-level or prefecture-level) of D. nuttalli were included while review articles and articles focusing on experimental research without exact locations of ticks were excluded. Then those articles with duplicate data were removed. All final articles included in meta-analysis were listed in Supplementary Text S1. The reference book utilized was Fauna Sinica-Arachnida Ixodida by YS (in the process of being published in Chinese) (Sun), from which the exact locations of D. nuttalli were extracted. The locations of D. nuttalli were also extracted in GBIF.

2.4. Associated pathogens and positive rates

To find out what other pathogens this tick carried, we conducted a meta-analysis to estimate the positive rate and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of D. nuttalli-associated pathogens. From the initial literature pool, 367 articles were included. Articles lacking specific pathogen detection data in D. nuttalli or the exact number of detected and total ticks were excluded, resulting in a final count of 85 articles. All those articles were listed in Supplementary Text S1. Data extracted included the number of D. nuttalli detected, the species of related pathogens D. nuttalli carried, and the positive number or positive rate of each pathogen. Incidence data from pooled tick studies and individual tick studies were organized into total test numbers and positive numbers. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 statistics. The fixed effects model was applied if I2 was less than 50%. Otherwise, the random effect model was used. If a pathogen was only reported in one study, its positive rate was calculated by dividing the positive number by the total number. Otherwise, the combined positive rate and 95% CI were calculated. The above calculations were carried out by the meta package in R 3.6.3 (Balduzzi et al., 2019).

2.5. Distribution status and potential distribution of D. nuttalli

The exact locations (longitude and latitude coordinates) of the collection points and the collection time of D. nuttalli were extracted from the database mentioned above. In instances where specific coordinates were not provided in the literature, the centroid of the administrative region was utilized as a proxy. ArcMap v10.7 was used to visualize the geographical distribution of D. nuttalli and unify the layer format.

To predict potential distributions of D. nuttalli, environmental and meteorological factors were obtained from the WorldClim database (https://worldclim.org). This included the average minimum temperature (°C), average maximum temperature (°C), and total precipitation (mm) post-2005. These parameters were chosen as over 97% of the samples were collected after 2005. Using R (version 3.6.3, dismo package) (Hijmans et al., 2022), these data were employed to generate the standard 19 WorldClim Bioclimatic variables (BIO1–BIO19). The elevation data were also obtained and used by the Spatial Analyst Tool of ArcMap v10.7 to generate the slope degree and slope aspect. Besides, the global land cover data were collected from The Global Land Cover by National Mapping Organizations (GLCNMO) (version 1) (Kobayashi et al., 2017).

Then an ecological niche model was applied to predict potential distributions of D. nuttalli, and the maximum entropy approach was applied to optimize models through Maxent v3.4.4 (Phillips et al., 2017). For predicting the distribution of D. nuttalli, the environmental and meteorological factors mentioned above were used to fit the model. To avoid model overfitting, duplicated distribution points were removed using the trimming duplicate occurrence function, and highly correlated factors were screened out by the correlation function in ENMTools v1.4.4 (Warren et al., 2010). Parameters calibration, evaluation, and selection of candidate models were made by R (version 3.6.3, kuenm package) to select the best model (Cobos et al., 2019).

3. Results

3.1. Pathogen abundance profile based on metagenomic sequencing

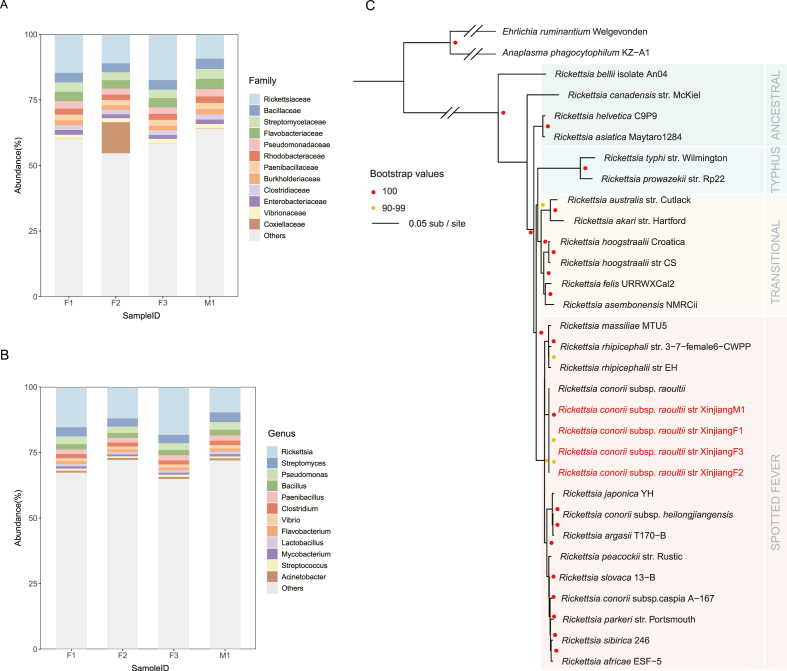

To systematically profile the pathogens in D. nuttalli, four metagenomic libraries were constructed and sequenced, generating 539.4–1370.31 million reads per library. Taxonomic classification based on sequencing reads revealed that the bacterial genus of highest abundance was Rickettsia (9.74%–18.28%), followed by Streptomyces (3.05%–3.69%), Pseudomonas (2.45%–2.98%), and Bacillus (1.92%–2.16%) (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Table S2). Although the Coxiellaceae family was detected only in F2, with an abundance of 11.83%, pathogens in this family could cause severe diseases, such as Q fever (Marrie, 1995). The high abundance of Rickettsia in each of the four libraries suggested persistent infection in D. nuttalli and potential risk for humans. We further tried to assemble the genomes of these pathogens, and obtained four Rickettsia genomes from the four tick samples (Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangF1, Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangF2, Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangF3, and Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangM1). The length of the assembled genomes of the four Rickettsiae was 1.26–1.27 Mb and all of them had BUSCO completeness greater than 97% with less than 5% contamination as assessed by CheckM (Parks et al., 2015) (Table 1). Then we constructed a phylogenetic tree, and all those four Rickettsia genomes were clustered together, showing 99.96%–100% genome identity to each other. The obtained Rickettsia assemblies showed 99.64%–99.70% identity to the closest species Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii (Fig. 1C), which is the causative agent of human lymphadenopathy (Husin et al., 2021). The presence and high abundance of Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii in each of the four libraries suggested persistent pathogen infection in D. nuttalli and potential threats to humans.

Fig. 1.

Relative pathogen abundance of four D. nuttalli samples and the phylogenomic analysis of four Rickettsia genomes.

(A) Pathogen abundance at the family level. (B) Pathogen abundance at the genus level. (C) The phylogenetic tree of four Rickettsia assemblies. The phylogenetic tree of four Rickettsia assemblies (Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangF1, Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangF2, Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangF3, and Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangM1) was built with 28 other publicly available established or proposed Rickettsiales species. The tree was inferred by IQ-TREE based on 277 single-copy orthologs identified by OrthoFinder. Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Ehrlichia ruminantium were two outgroup species.

Table 1.

Genome characteristics of the four Rickettsia genome assemblies.

| Characteristic | Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangF1 | Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangF2 | Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangF3 | Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii str XinjiangM1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (Mb) | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.26 |

| BUSCO | 95.60% | 95.90% | 95.90% | 95.60% |

| GC content | 32.45% | 32.44% | 32.45% | 32.46% |

| CDSa | 1424 | 1428 | 1428 | 1416 |

| tRNAs | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| No. of contigs | 29 | 32 | 27 | 29 |

| N50 (bp) | 52,044 | 73,402 | 73,428 | 51,928 |

| N90 (bp) | 24,687 | 19,843 | 24,687 | 24,687 |

| rRNAs | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

CDS, coding sequence.

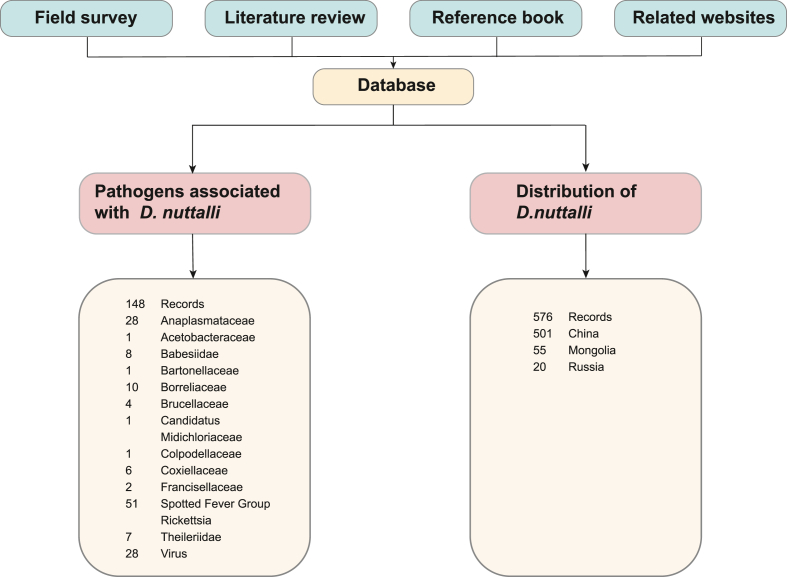

3.2. Pathogens associated with D. nuttalli identified by meta-analysis

To comprehensively investigate the pathogens associated with D. nuttalli, we conducted a meta-analysis of pathogens based on published databases. As shown in Fig. 2, 148 records were included in the integrated database for meta-analysis of pathogens. The meta-analysis showed that 48 pathogens were detected in D. nuttalli, of which 22 were pathogenic to humans, eight to animals and 18 had unknown pathogenic risks. These pathogens included 20 identified bacteria, seven identified eukaryotes, and 21 identified viruses (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S3).

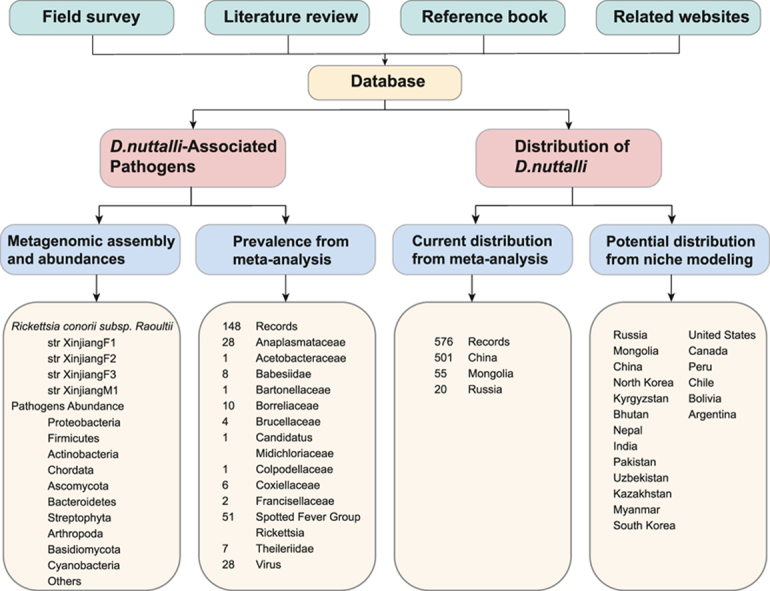

Fig. 2.

Study design and data sources of the meta-analysis.

A comprehensive meta-analysis was performed to evaluate D. nuttalli's potential threats based on detected pathogens and geographical distribution positions. The database of D. nuttalli was constructed from four sources, including field surveys, literature review, a reference book, and an online biodiversity database (Global Biodiversity Information Facility, GBIF, https://www.gbif.org).

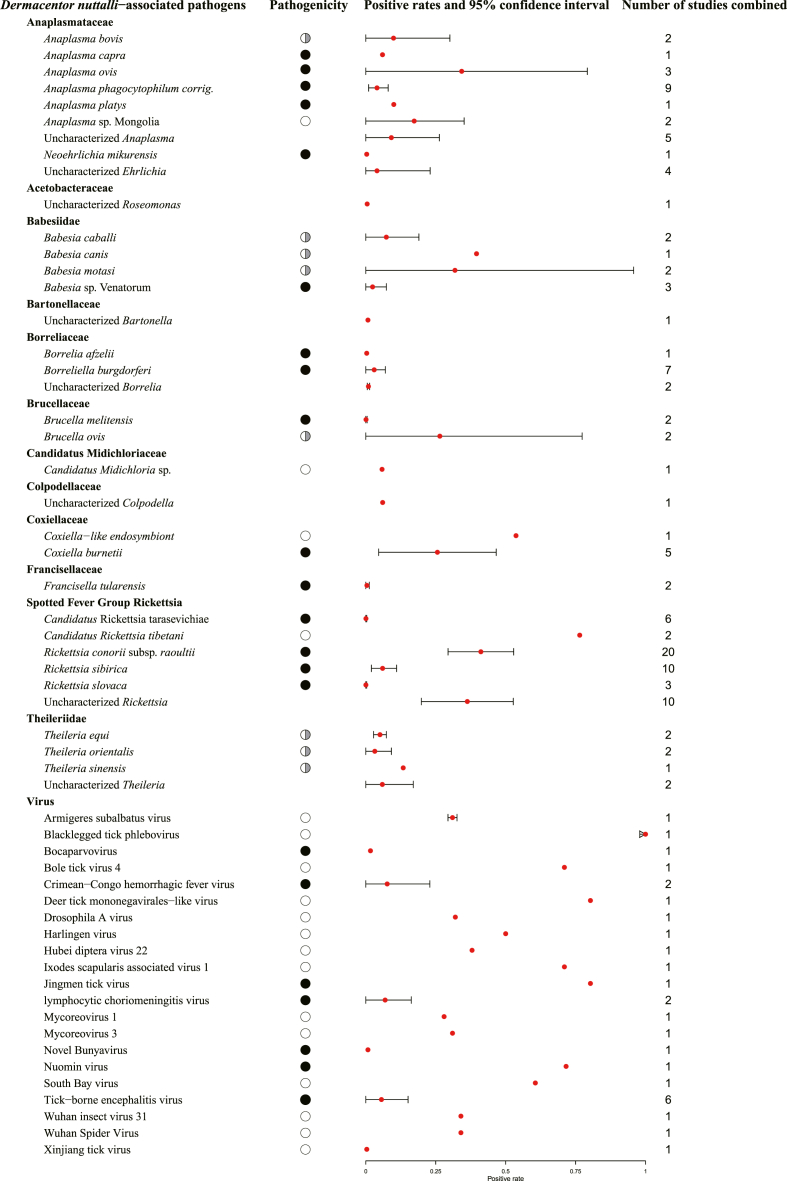

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of pathogens associated with D. nuttalli.

If there was only one study included in a certain pathogen, the positive rate would be calculated by the positive number of ticks divided by the total number of detected ticks, and without the 95% confidence interval. If there were more studies, the positive rate and 95% confidence interval would be calculated by meta-analysis.

Among those 20 identified bacteria, Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii had a high pooled positivity rate (41.13%, 95% CI: 0.29–0.53), concordant with our metagenomic analysis of field-collected ticks. Rickettsia sibirica, another human pathogenic Rickettsia, had a pooled positivity rate of 6.00% (95% CI: 0.02–0.11), which could cause human lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis (LAR) (Echevarría-Zubero et al., 2021; Vázquez-Pérez et al., 2022). Besides, Coxiella burnetii was also detected, which had a 25.60% pooled positive rate (95% CI: 0.05–0.47) and could cause Q fever (Eldin et al., 2017). In addition, some eukaryotes in those 7 identified eukaryotes were pathogenic to humans. For example, Anaplasma ovis had the highest pooled positive rate (34.28%) and Anaplasma phagocytophilum corrig. had 4.71%, which could cause human granulocytic anaplasmosis (Kahlon et al., 2013; Hosseini-Vasoukolaei et al., 2014). As well as Babesia sp. Venatorum, which had a 2.42% positive rate and caused human babesiosis (Sun et al., 2014). In the viral category, Tick-borne encephalitis virus and Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus were noted for their pathogenicity to humans, with positivity rates of 5.59% (95% CI: 0–0.15) and 6.91% (95% CI: 0.09–0.14), respectively. In addition to human pathogens, several pathogens in D. nuttalli were identified as particularly harmful to animals. For example, Brucella ovis (42.59%; 95% CI: 0.33–0.53), a gram-negative bacterium, is a serious hazard to sheep and leads to severe economic loss (Muñoz et al., 2022).

3.3. Distribution of D. nuttalli

To explore the distribution of D. nuttalli, 576 records in total were included for the subsequent analysis, including 501 records in China, 55 records in Mongolia, and 20 records in Russia (Fig. 2). Our data showed that D. nuttalli mainly lived in 23°–53°N latitude in the Northern hemisphere, and was distributed only in China, Russia, and Mongolia (Fig. 4). The southernmost position was at 23°N in China while the northernmost position was 53°N in Russia. The westernmost point of D. nuttalli was at 76°E while the easternmost was at 132.94°W in China. The main land cover types of its habitat were herbaceous (23.61%), cropland (19.97%), and shrub (13.37%).

Fig. 4.

Geographical distribution of D. nuttalli.

D. nuttalli lived mainly between 23°–53° latitude and 76°–133° longitude in the Northern Hemisphere. Triangles represent the locations in prefecture-level regions, while circles represent the distribution locations in county-level regions. The green circles represent points from GBIF, the yellow circles are points from literature, the purple circles represent the points from the field survey and the blue points are points from a reference book. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

In Mongolia, D. nuttalli was found mainly in Hentiy (25 records), Selenge (13 records), Dornogovi (six records), and Tov (five records) provinces (aimags). Those provinces share a temperate continental climate and live on agriculture and animal husbandry. In Russia, it was primarily distributed in Altay (11 records), Irkutsk (five records) and Tuva (three records), and these areas were mainly covered by forests. In China, D. nuttalli were generally distributed in the northern regions, and a majority of them were found near the Great Khingan Mountains and Qilian Mountains. It had been documented in 13 provinces, with a higher number of records from Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Qinghai compared with other provinces, accounting for 68% (343/501) of the total records. Before 2010, D. nuttalli was predominantly reported in Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and three northeastern provinces. However, recent reports gradually included records from inland provinces, including Qinghai, Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Yunnan (Supplementary Text S1).

3.4. Potential distribution of D. nuttalli

To systematically identify suitable habitats for D. nuttalli, ecological niche modeling was used to predict its global distribution. After trimming duplicate occurrences, there were 301 known distribution points, of which 266 points were randomly selected as the training set for Maxent model training, and the remaining 75 points were used as the test set for validation. The model input features included the standard 19 WorldClim Bioclimatic variables (BIO1–BIO19), land cover, elevation, slope degree, and slope aspect. Eleven independent variables were finally selected to train the model, including BIO1, BIO2, BIO7, BIO12, BIO17, BIO18, BIO19, land cover, elevation, slope aspect, and slope degree (Table 2). The best model corresponded to the combination of quadratic (Q), product (P), and threshold (T) features and a regularization multiplier of 1.8, with the smallest Akaike information criterion value. The model's performance was further evaluated in terms of Area Under the Curve (AUC), which stood at 0.96 ± 0.02 across 25 replicates. This high AUC value signified a robust model fitting, reflecting the model's accuracy in predicting the suitable habitats for D. nuttalli.

Table 2.

Relative contributions of environmental and meteorological variables to the Maxent model.

| Variable | Percent Contribution | Permutation Importance |

|---|---|---|

| BIO19 (precipitation of coldest quarter) | 38.3 | 20.4 |

| BIO1 (annual mean temperature) | 35.7 | 44.4 |

| BIO7 (temperature annual range) | 13 | 16.3 |

| BIO2 (mean diurnal range) | 5.6 | 1.6 |

| Land Cover | 2.9 | 1.7 |

| BIO17 (precipitation of driest quarter) | 2 | 6.9 |

| Elevation | 1.1 | 3.3 |

| BIO18 (precipitation of warmest quarter) | 0.9 | 4.8 |

| BIO12 (annual precipitation) | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Slope Degree | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Slope Aspect | 0.1 | 0 |

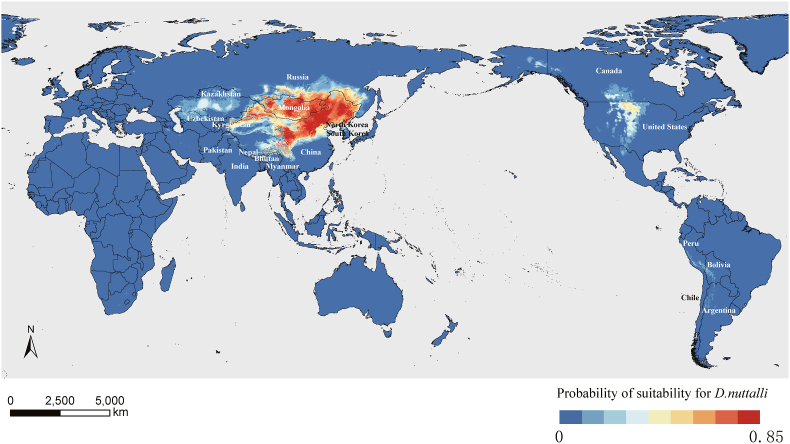

Based on the variable contributions, temperature and precipitation were the most important factors influencing the distribution of D. nuttalli (Supplementary Fig. S2). Specifically, the most suitable habitat for D. nuttalli was characterized by an average annual temperature of 3.9 °C, a temperature annual range of 58.5 °C, and a mean diurnal range of 11.9 °C In addition, the precipitation of the coldest quarter was 12 mm, and the precipitation of the driest quarter was seven mm.

The model suggested that D. nuttalli could have a wider distribution than previous records, including areas where it had never been recorded (Fig. 5). The most suitable areas for D. nuttalli were primarily China, Mongolia, Russia, and North Korea. Notably, North Korea had a probability of suitability greater than 0.8. However, the occurrence of D. nuttalli had not been reported in the investigated databases of this study. Furthermore, five countries on the Eurasian continent processed potential habitats with a predicted probability above 0.5, including Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Bhutan, Pakistan, and India. Notably, in both Canada and the United States, there were also potentially suitable areas with a predicted probability exceeding 0.4.

Fig. 5.

Global potential distribution of D. nuttalli.

The red area indicates greater possibilities of suitability for D. nuttalli, while the blue area is less likely to be suitable for D. nuttalli.

4. Discussion

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive investigation of the pathogens carried by collected D. nuttalli and assembled four Rickettsia genome assemblies closely relative to Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii. Our meta-analysis revealed that D. nuttalli carried at least forty-eight pathogens, some of which pose significant health risks to humans and animals. Geographically, D. nuttalli was found between 22.6°N and 53.18°N in China, Mongolia, and Russia, and the ecological niche model suggested a potentially broader habitat for this species. Above results underscore the importance of monitoring D. nuttalli's impact on public health and animal husbandry.

Our study reported up to 48 pathogens identified in D. nuttalli, many of which were virulent pathogens with high pooled positive rates in D. nuttalli, suggesting the emerging threat to public health and the livestock industry in related countries. For example, Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii, first detected in D. nuttalli from the former Soviet Union in 1999, was identified as a novel Rickettsia species in 2008 (Jia et al., 2014). Some studies investigated serological evidence of Rickettsia raoultii infection in humans (Sekeyova et al., 2012; Dubourg et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018), demonstrating the pathogen's direct impact on human health. Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii is a causative agent of lymphadenopathy. Humans infected by it can present with symptoms including fever, malaise, myalgia, lymphadenopathy, and nausea, and in a few cases, a rash, eschar. In severe cases, complications such as pulmonary edema, confusion, and lethargy can occur (Li et al., 2018). Besides, Wölfel and colleagues conducted a study revealing a high seroprevalence of R. raoultii among forestry workers in Eastern Germany, indicating the occupational exposure risks of humans (Wölfel et al., 2017). Another pathogen that could cause serious disease in humans was the Coxiella burnetii. It is an obligate intracellular pathogen with high pathogenicity, which can infect a wide range of animals (Mori et al., 2017; España et al., 2020). The most common infection way of humans is by inhaling pathogenic aerosol, so rural people who are often in contact with animals infected by Coxiella burnetii are frequently infected (España et al., 2020). If Coxiella burnetii infects pregnant women, it may result in abortion, premature delivery, and stillbirth (Kazar, 2005). It is worth noting that the positive rates in our article did not separate the detection rates for pathogens in ticks from the environment or from livestock, as it was difficult to define the source of the ticks in much of the literature in the database. However, the detection rates of pathogens in ticks are different between ticks collected from the environment and ticks collected from livestock, which may have some influence on the positive rate results (von Fricken et al., 2020). Besides, one study reported that R. raoultii demonstrated a high prevalence exceeding 50% in Mongolia, which was slightly higher than 41.13% in our study (Altantogtokh et al., 2022). This discrepancy can be attributed to the broader geographic scope of our study, which highlights the importance of considering geographic variability in pathogen prevalence studies. Furthermore, a pathogen with a high pooled positive rate is not always the dominant pathogen detected in D. nuttalli. For instance, Blacklegged tick phlebovirus had a 100% positive rate, but only one study reported this virus detected in D. nuttalli and all the ticks in the studies were from the same place. Therefore, the vector competence of D. nuttalli in transmitting human and animal diseases should be taken into consideration when interpreting the pathogen prevalence results.

Interestingly, although Dermacentor nuttalli and Dermacentor silvarum are species belonging to the same genus Dermacentor (Acari: Ixodidae) and are distributed in similar areas, the type of reported pathogens identified in Dermacentor nuttalli is different from that of Dermacentor silvarum (Guo et al., 2021). For instance, the prevalence of Anaplasma ovis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum was less than 10% in D. silvarum, compared to more than 34% and 19% in D. nuttalli, respectively. Besides, Brucella ovis was not detected in D. silvarum but had a pooled positive rate of 26.47% in D. nuttalli. Nevertheless, Bartonella and Hepatozoon were not found in D. nuttalli but were found in D. silvarum. Furthermore, compared with another hard tick, Ixodes persulcatus, D. nuttalli carried more Coxiellaceae and Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia (Wang et al., 2023).

Our study showed that D. nuttalli was primarily distributed in inland areas between 22.6°–53.18°N in the Northern Hemisphere. For ticks that are more host-specific, such as D. nuttalli, host availability in time and space is important for tick bionomics (Emms and Kelly, 2019). The dominant hosts of this tick are Ovis aries and Capra aegagrus, mainly living in inland areas such as grasslands, which may be the reason for the distribution of D. nuttalli.

According to our model, the most important feature for the distribution of D. nuttalli was temperature-related variables, such as annual mean temperature (BIO1), mean diurnal range (BIO2), temperature annual range (BIO7), which explained over 54.3% of contribution to the model. The next group of key factors included precipitation-related variables, such as precipitation of coldest quarter (BIO19), which could explain over 41.5% of contributions to the model. Temperature and humidity play important roles in shaping insect distribution and life history (Gerstengarbe and Werner, 2008; Wellenreuther et al., 2012). Ticks in the questing and diapausing stages are highly sensitive to dramatic changes in temperature and humidity, and the hatchability and hatching time of eggs will vary according to relative humidity and temperature (Estrada-Peña, 2008). Our results were also in line with previous studies that precipitation and temperature played important roles (30.8% and 25.5% of contribution) in D. nuttalli distribution (Sun et al., 2014).

Our model suggested a broader distribution of D. nuttalli, especially in North Korea and some regions outside Asia. According to our model, regions where the probability of suitability exceeds 0.6 were mainly in some Asian countries and Russia. In particular, North Korea had a distribution probability exceeding 0.8, indicating the neglected threat from D. nuttalli. Interestingly, a few suitable habitat areas for D. nuttalli were identified in North America. This observation could be attributed to comparable temperature, humidity, and other meteorological factors in these areas as compared to North Asia. However, it is crucial to note that our niche modeling did not account for several pivotal factors determining tick habitat, such as host availability, competitors, and predators.

This study has some limitations. First, only articles published in English or Chinese were included in the data collection stage, so some articles in other languages may have been missed. Second, the positive rate of pathogens may be affected by detection methods, detection reagents, sensitivities and tick sources in different research. Finally, some factors that are not easy to quantify, such as human activities, are not included, which may affect the accuracy of the results.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, D. nuttalli carries multiple important pathogens, such as Rickettsia conorii subsp. raoultii, is widely distributed, especially in pastoral areas, suggesting an emerging threat to public health and animal husbandry. There is a pressing need to strengthen the surveillance and investigation of D. nuttalli.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

HW and TX organized the database. HW performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. WS and ZL reviewed and edited the manuscript. Supervision was done by WS, ZL and WC. All authors listed provide approval for publication of the content.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China [81621005, 31900492, 72071207, 82103897]; the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China [ZR2020QH299], and Cheeloo Young Scholar Program of Shandong University; the National key research and development program of China [2022YFC260280005, 2021YFC2302001]; and State Key Research Development Program of China [2019YFC1200501].

Availability of data and materials

The genome assemblies in this study are available in GenBank under the accession JAWONN000000000, JAWONP000000000, JAWONO000000000, JAWONQ000000000. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its additional files.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2024.100907.

Contributor Information

Wenqiang Shi, Email: wqshi_mail@163.com.

Lin Zhao, Email: zhaolin1989@sdu.edu.cn.

Wu-Chun Cao, Email: caowuchun@126.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Altantogtokh D., Lilak A.A., Takhampunya R., Sakolvaree J., Chanarat N., Matulis G., Poole-Smith B.K., Boldbaatar B., Davidson S., Hertz J., Bolorchimeg B., Tsogbadrakh N., Fiorenzano J.M., Lindroth E.J., von Fricken M.E. Metagenomic profiles of Dermacentor tick pathogens from across Mongolia, using next generation sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.946631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balduzzi S., Rücker G., Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid. Base Ment. Health. 2019;22:153–160. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., Pyshkin A.V., Sirotkin A.V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G., Alekseyev M.A., Pevzner P.A. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard C., Dibernardo A., Koffi J., Wood H., Leighton P.A., Lindsay L.R. N Increased risk of tick-borne diseases with climate and environmental changes. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2019;45:83–89. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v45i04a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Yang X., Bu F., Yang X., Yang X., Liu J. Ticks (acari: ixodoidea: argasidae, ixodidae) of China. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2010;51:393–404. doi: 10.1007/s10493-010-9335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos M.E., Peterson A.T., Barve N., Osorio-Olvera L. kuenm: an R package for detailed development of ecological niche models using Maxent. PeerJ. 2019;7 doi: 10.7717/peerj.6281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubourg G., Socolovschi C., Del Giudice P., Fournier P.E., Raoult D. Scalp eschar and neck lymphadenopathy after tick bite: an emerging syndrome with multiple causes. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014;33:1449–1456. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarría-Zubero R., Porras-López E., Campelo-Gutiérrez C., Rivas-Crespo J.C., Lucas A.M., Cobo-Vázquez E. Lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis by Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae. J. Pediatric Infect. Dis. Soc. 2021;10:797–799. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piab018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldin C., Mélenotte C., Mediannikov O., Ghigo E., Million M., Edouard S., Mege J.L., Maurin M., Raoult D. From Q fever to Coxiella burnetii infection: a Paradigm change. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017;30:115–190. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00045-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elith J., Graham C.H., Anderson R.P., Dudík M., Ferrier S., Guisan A., Hijmans R.J., Huettmann F., Leathwick J.R., Lehmann A. Novel methods improve prediction of species' distributions from occurrence data. Ecography. 2010;29:129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Emms D.M., Kelly S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019;20:238. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España P.P., Uranga A., Cillóniz C., Torres A. Q fever (Coxiella burnetii) Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020;41:509–521. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Peña A. Climate, niche, ticks, and models: what they are and how we should interpret them. Parasitol. Res. 2008;103(Suppl. 1):S87–S95. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer T., Myalkhaa M., Krücken J., Battsetseg G., Batsukh Z., Baumann M.P.O., Clausen P.H., Nijhof A.M. Molecular detection of tick-borne pathogens in bovine blood and ticks from Khentii, Mongolia. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2020;67(Suppl. 2):111–118. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley D.H., Rueda L.M., Peterson A.T., Wilkerson R.C. Potential distribution of two species in the medically important Anopheles minimus complex (Diptera: Culicidae) J. Med. Entomol. 2008;45:852–860. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[852:pdotsi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstengarbe F.W., Werner P.C. Climate development in the last century – global and regional. Int. J. Med. Microbiol.: IJMM. 2008;298:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L. The impacts of climate change on ticks and tick-borne disease risk. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021;66:373–388. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-052720-094533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui Z., Wu L., Cai H., Mu L., Yu J.F., Fu S.Y., Si X.Y. Genetic diversity analysis of Dermacentor nuttalli within Inner Mongolia, China. Parasites Vectors. 2021;14:131. doi: 10.1186/s13071-021-04625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W.B., Shi W.Q., Wang Q., Pan Y.S., Chang Q.C., Jiang B.G., Cheng J.X., Cui X.M., Zhou Y.H., Wei J.T., Sun Y., Jiang J.F., Jia N., Cao W.C. Distribution of Dermacentor silvarum and associated pathogens: meta-analysis of global published data and a field survey in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans Robert J., Steven Phillips, Leathwick John, Jane Elith dismo: Species Distribution Modeling. R package version 1.3-9. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dismo

- Hosseini-Vasoukolaei N., Oshaghi M.A., Shayan P., Vatandoost H., Babamahmoudi F., Yaghoobi-Ershadi M.R., Telmadarraiy Z., Mohtarami F. Anaplasma infection in ticks, livestock and human in Ghaemshahr, Mazandaran province, Iran. J. Arthropod Borne Dis. 2014;8:204–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T., Zhang J., Sun C., Liu Z., He H., Wu J., Geriletu A novel arthropod host of brucellosis in the arid steppe ecosystem. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.566253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husin N.A., Khoo J.J., Zulkifli M.M.S., Bell-Sakyi L., AbuBakar S. Replication kinetics of Rickettsia raoultii in tick cell lines. Microorganisms. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9071370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iduu N., Barua S., Falkenberg S., Armstrong C., Stockler J.W., Moye A., Walz P.H., Wang C. Theileria orientalis Ikeda in cattle, Alabama, USA. Vet. Sci. 2023;10 doi: 10.3390/vetsci10110638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javkhlan G E.B., Baigal B., Myagmarsuren P., Battur B., Battsetseg B. Natural Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection in ticks from a forest area of Selenge province, Mongolia. Western Pac. Surveill. Response J. 2014;5:21–24. doi: 10.5365/WPSAR.2013.4.3.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia N., Zheng Y.C., Ma L., Huo Q.B., Ni X.B., Jiang B.G., Chu Y.L., Jiang R.R., Jiang J.F., Cao W.C. Human infections with Rickettsia raoultii, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:866–868. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.130995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlon A., Ojogun N., Ragland S.A., Seidman D., Troese M.J., Ottens A.K., Mastronunzio J.E., Truchan H.K., Walker N.J., Borjesson D.L., Fikrig E., Carlyon J.A. Anaplasma phagocytophilum Asp14 is an invasin that interacts with mammalian host cells via its C terminus to facilitate infection. Infect. Immun. 2013;81:65–79. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00932-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D.D., Li F., Kirton E., Thomas A., Egan R., An H., Wang Z. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ. 2019;7 doi: 10.7717/peerj.7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Misawa K., Kuma K., Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazar J. Coxiella burnetii infection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1063:105–114. doi: 10.1196/annals.1355.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Tateishi R., Alsaaideh B., Sharma R.C., Wakaizumi T., Miyamoto D., Bai X., Long B.D., Gegentana G., Maitiniyazi A. Production of Global Land Cover Data - GLCNMO2013. J. Geograph. Geol. 2017;9(3):1–15. doi: 10.5539/jgg.v9n3p1. 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larson S.R., DeGroote J.P., Bartholomay L.C., Sugumaran R. Ecological niche modeling of potential West Nile virus vector mosquito species in Iowa. J. Insect. Sci. 2010;10:110. doi: 10.1673/031.010.11001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Zhang P.H., Huang Y., Du J., Cui N., Yang Z.D., Tang F., Fu F.X., Li X.M., Cui X.M., Fan Y.D., Xing B., Li X.K., Tong Y.G., Cao W.C., Liu W. Isolation and identification of Rickettsia raoultii in human cases: a surveillance study in 3 medical centers in China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;66:1109–1115. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrie T.J. Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995;21(Suppl. 3):S253–S264. doi: 10.1093/clind/21.supplement_3.s253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J.T., Fischhoff I.R., Castellanos A.A., Han B.A. Ecological predictors of zoonotic vector status among dermacentor ticks (Acari: ixodidae): a trait-based approach. J. Med. Entomol. 2022;59:2158–2166. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjac125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minh B.Q., Schmidt H.A., Chernomor O., Schrempf D., Woodhams M.D., von Haeseler A., Lanfear R. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020;37:1530–1534. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M., Mertens K., Cutler S.J., Santos A.S. Critical aspects for detection of Coxiella burnetii. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17:33–41. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz P.M., Conde-Álvarez R., Andrés-Barranco S., de Miguel M.J., Zúñiga-Ripa A., Aragón-Aranda B., Salvador-Bescós M., Martínez-Gómez E., Iriarte M., Barberán M., Vizcaíno N., Moriyón I., Blasco J.M. A Brucella melitensis H38ΔwbkF rough mutant protects against Brucella ovis in rams. Vet. Res. 2022;53:16. doi: 10.1186/s13567-022-01034-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden N.H., Lindsay L.R. Effects of climate and climate change on vectors and vector-borne diseases: ticks are different. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:646–656. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks D.H., Imelfort M., Skennerton C.T., Hugenholtz P., Tyson G.W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015;25:1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A.T., Pape M. Potential geographic distribution of the Bugun Liocichla. Indian Birds. 2007;2:146–149. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips S., Dudik M., Schapire R. 2017. A Brief Tutorial on Maxent.https://biodiversityinformatics.amnh.org/open_source/maxent/Maxent_tutorial2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger L., Ganzinelli S., Bhoora R., Omondi D., Nijhof A.M., Florin-Christensen M. The Piroplasmida Babesia, Cytauxzoon, and Theileria in farm and companion animals: species compilation, molecular phylogeny, and evolutionary insights. Parasitol. Res. 2022;121:1207–1245. doi: 10.1007/s00436-022-07424-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekeyova Z., Subramanian G., Mediannikov O., Diaz M.Q., Nyitray A., Blaskovicova H., Raoult D. Evaluation of clinical specimens for Rickettsia, Bartonella, Borrelia, Coxiella, Anaplasma, Franciscella and Diplorickettsia positivity using serological and molecular biology methods. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012;64:82–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simão F.A., Waterhouse R.M., Ioannidis P., Kriventseva E.V., Zdobnov E.M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John H.K., Adams M.L., Masuoka P.M., Flyer-Adams J.G., Jiang J., Rozmajzl P.J., Stromdahl E.Y., Richards A.L. Prevalence, distribution, and development of an ecological niche model of dermacentor variabilis ticks positive for Rickettsia montanensis. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016;16:253–263. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2015.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Li S.G., Jiang J.F., Wang X., Zhang Y., Wang H., Cao W.C. Babesia venatorum infection in child, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:896–897. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.121034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.X., R. M, Fauna Sinica-Arachnida Ixodida. Science Press: Beijing, China.

- Valencia-Rodríguez D., Jiménez-Segura L., Rogéliz C.A., Parra J.L. Ecological niche modeling as an effective tool to predict the distribution of freshwater organisms: the case of the Sabaleta Brycon henni (Eigenmann, 1913) PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Pérez Á., Rodríguez-Granger J., Calatrava-Hernández E., Santos-Pérez J.L. Pediatric tubular acute lymphangitis caused by Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae: case report and literature review. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clín. 2022;40:218–219. doi: 10.1016/j.eimce.2021.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Fricken M.E., Qurollo B.A., Boldbaatar B., Wang Y.W., Jiang R.R., Lkhagvatseren S., Koehler J.W., Moore T.C., Nymadawa P., Anderson B.D., Matulis G., Jiang J.F., Gray G.C. Genetic diversity of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia bacteria found in dermacentor and Ixodes ticks in Mongolia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020;11 doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.101316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.S., Liu J.Y., Wang B.Y., Wang W.J., Cui X.M., Jiang J.F., Sun Y., Guo W.B., Pan Y.S., Zhou Y.H., Lin Z.T., Jiang B.G., Zhao L., Cao W.C. Geographical distribution of Ixodes persulcatus and associated pathogens: analysis of integrated data from a China field survey and global published data. One Health. 2023;16 doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren D.L., Glor R.E., Turelli M. ENMTools: a toolbox for comparative studies of environmental niche models. Ecography. 2010;33:607–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06142.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watts J.G., Playford M.C., Hickey K.L. Theileria orientalis: a review. N. Z. Vet. J. 2016;64:3–9. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2015.1064792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellenreuther M., Larson K.W., Svensson E.I. Climatic niche divergence or conservatism? Environmental niches and range limits in ecologically similar damselflies. Ecology. 2012;93:1353–1366. doi: 10.1890/11-1181.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood D.E., Lu J., Langmead B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019;20:257. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wölfel S., Speck S., Essbauer S., Thoma B.R., Mertens M., Werdermann S., Niederstrasser O., Petri E., Ulrich R.G., Wölfel R., Dobler G. High seroprevalence for indigenous spotted fever group rickettsiae in forestry workers from the federal state of Brandenburg, Eastern Germany. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017;8:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The genome assemblies in this study are available in GenBank under the accession JAWONN000000000, JAWONP000000000, JAWONO000000000, JAWONQ000000000. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its additional files.