Abstract

The ‘2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines’ are authored by a Task Force of experts in feline clinical medicine and serve as an update and extension of those published in 2009. They emphasize the individual patient evaluation and the process of aging, with references to other feline practice guidelines for a more complete discussion of specific diseases. Focusing on each cat encourages and empowers the owner to become a part of the cat’s care every step of the way. A comprehensive discussion during the physical examination and history taking allows for tailoring the approach to both the cat and the family involved in the care. Videos and analysis of serial historical measurements are brought into the assessment of each patient. These Guidelines introduce the emerging concept of frailty, with a description and methods of its incorporation into the senior cat assessment. Minimum database diagnostics are discussed, along with recommendations for additional investigative considerations. For example, blood pressure assessment is included as a minimum diagnostic procedure in both apparently healthy and ill cats. Cats age at a much faster rate than humans, so practical timelines for testing frequency are included and suggest an increased frequency of diagnostics with advancing age. The importance of nutrition, as well as senior cat nutritional needs and deficiencies, is considered. Pain is highlighted as its own syndrome, with an emphasis on consideration in every senior cat. The Task Force discusses anesthesia, along with strategies to allow aging cats to be safely anesthetized well into their senior years. The medical concept of quality of life is addressed with the latest information available in veterinary medicine. This includes end of life considerations like palliative and hospice care, as well as recommendations on the establishment of ‘budgets of care’, which greatly influence what can be done for the individual cat. Acknowledgement is given that each cat owner will be different in this regard; and establishing what is reasonable and practical for the individual owner is important. A discussion on euthanasia offers some recommendations to help the owner make a decision that reflects the best interests of the individual cat.

Keywords: Senior, frailty, comorbidities, quality of life, sarcopenia, blood pressure, pain, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, hyperthyroidism, osteoarthritis, degenerative joint disease, diabetes mellitus, anesthesia, gastrointestinal disease, dental disease, cancer, cognitive dysfunction syndrome, end of life, palliative care, hospice care, budgets of care, euthanasia

Introduction

Since the publication of the ‘AAFP Senior Care Guidelines’ in 2009, 1 our knowledge has advanced significantly, and today’s cat owners expect a higher level of care. In human medicine, gerontology has insufficient specialists for multiple reasons. In feline medicine, most of us love caring for older cats; they are often our favorite patients. We could likely fill a feline gerontology specialty with enthusiastic veterinarians. In response to recent advancements and an increased interest in senior feline medicine, we present updated guidance in these ‘2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines’.

We consider ‘senior’ to be a term that describes age. While senior is defined as over 10 years of age in the ‘2021 AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stage Guidelines’, 2 some cats may be more appropriately referred to as senior as early as 8 years of age, possibly sooner for some breeds or those with genetic predispositions.3,4 The Task Force feels that ‘geriatric’ is more a statement of health status, and has no specifically associated age. The Task Force also acknowledges the newer concept of ‘frailty,’ which plays a huge role in the care of older humans and is becoming more significant in feline medicine.

This Guidelines document concentrates on the feline examination and owner consultation, which together provide the best understanding of each cat’s needs. It emphasizes that owner involvement in the assessment of a senior cat is crucial and impacts our interpretation of clinical findings. Although we briefly discuss individual diseases, our focus stays on individual patients and how their aging process influences their wellbeing. We discuss the common occurrence of comorbidities and how they bring complexity to senior care. We also want to emphasize that senior cats are often dealing with one or more sources of chronic pain. The Task Force proposes that pain be thought of as a disease itself that can greatly influence quality of life. Moreover, because teaching cat owners how to improve quality of life for these patients is the number one priority, we offer practical solutions to multifactorial health situations. Challenging scenarios include end of life care with the interactions of hospice, euthanasia, and an acknowledgment of possible burdens on the cat owner.

To best meet these demands, we encourage veterinarians to look more closely at the aging process, not just the individual diagnosis. Ultimately, we hope to augment the knowledge of older cats for both owners and veterinarians, and increase the level of senior cat veterinary care.

The senior cat wellness visit

Information gathering: understanding owner and cat concerns

Many domestic cats have seen an increase in life expectancy due to improved veterinary care, better nutrition and more informed, engaged owners. This gives veterinarians the opportunity to take a comprehensive approach to the assessment and management of senior feline patients. Educating clients to appreciate subtle changes that may point to an underlying disorder can help them partner with the veterinarian to observe their feline companions more closely. Routine assessment facilitates health maintenance and early detection of disease, often resulting in easier disease management and prevention, and may lead to better quality of life; it is less costly and more successful than crisis management.

Ideally, schedule longer appointments for senior cat visits. While we often come from the perspective of advocating for the cat, an understanding of client resources, abilities, behaviors and beliefs ensures we address client concerns. Sending a questionnaire to be completed ahead of time and checking on client goals early during the visit facilitate this understanding. Asking open-ended questions pertaining to all body systems yields more meaningful data. Client observations can help the veterinarian detect subtle changes; however, many clients may be unaware of gradual changes until we ask provocative questions. Client-recorded videos of patient activities at home may provide additional insights into the health status of the cat. Obtaining a systematic and thorough history may take a little longer initially, yet often results in more accurate diagnosis and effective care of the senior cat.

Task Force members consider the following key items when developing a plan to ascertain the status of the cat:

Environment: How the cat’s home is structured; what other people/pets share the space; time the cat spends outside (free roaming, on leash, in outdoor enclosure); whether the cat must traverse stairs; feeding routine and location(s) of feeding stations; sleeping posture, patterns and locations; number of litter boxes, type and location.

Intake: Specific products fed, amount consumed (caloric intake); supplements and/or medications given; intake from prey or other food sources; preventives used; observations of chewing behavior; estimated water intake.

Eliminations: Urination and defecation sites, frequency and quantity (litter ball size, amount of stool passed, fecal score); any sudden onset of unusual behavior (eg, house-soiling) in either the current patient or another cat (may reflect occult disease); a cat may also detect illness in a housemate if the disease changes the smell of a companion cat or its eliminations.

Patterns of activities: Grooming habits (Figure 1), vocalizations, and interactions with other animals/people; sleeping behavior and locations; response to visual cues and sounds; jumping and playing behavior (inviting clients to keep video records from an early age will allow comparisons with current levels of activity).

Figure 1.

This 15-year-old cat shows a decreased pattern of grooming. Courtesy of Sheilah Robertson

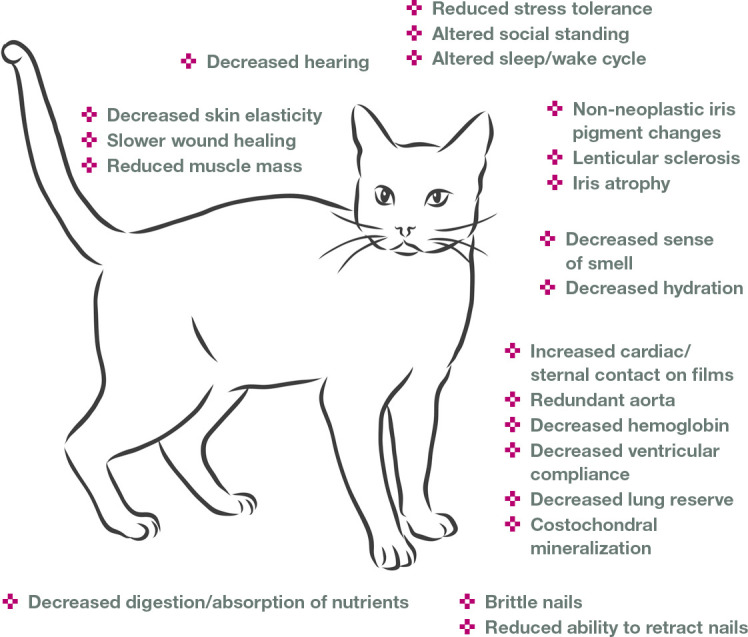

Veterinarians often quote the adage, ‘Old age is not a disease’, but it is a process. As with all species, changes are seen in the aging cat (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Changes associated with aging (and often seen in apparently healthy senior cats)

Muscle wasting in seniors carries important implications for health status. Cachexia refers to weight loss in the face of underlying disease. 5 Sarcopenia refers to loss of muscle mass as a syndrome associated with aging, independent of illness. 5 Sarcopenia includes a loss of both muscle mass and strength (Figure 3). This may manifest itself as decreased jumping and physical strength, as well as reduced activity and interactions. The physical manifestations of sarcopenia intersect with the physiologic manifestations of frailty. Given the association of sarcopenia with poorer outcomes, recognition of signs of feline frailty is especially important. 6 Explore potential pathologic causes when signs of frailty are detected. Even if no diseases are found, early therapeutic interventions may help to restore some function.

Figure 3.

Same cat as in Figure 1, showing signs of frailty, including loss of muscle mass and strength. This senior was diagnosed with sarcopenia, osteoarthritis and hyperthyroidism. Courtesy of Sheilah Robertson

Nutritional manipulation may be beneficial. Highly digestible diets rich in antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids, 7 as well as interactive toys and puzzles and environmental enrich-ment,8,9 may all help to slow the development of sarcopenia.

Unexplained trends in body weight, body condition score (BCS) and/or muscle condition score (MCS) are problems that must be investigated and managed as diseases. Consider weight changes in the context of the cat’s size. Petite cats may not change much in absolute terms, but a proportional change could be significant. Body composition alters even within a constant weight, so concurrent assessment of MCS and BCS is critical. More information on body condition and muscle condition scoring is provided by the International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM; www.bit.ly/ISFMMCS). Overweight and underweight cats have associated health risks.9,10

The senior cat physical examination

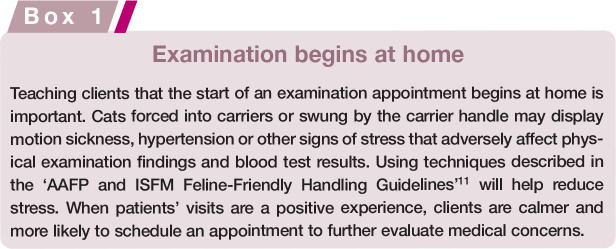

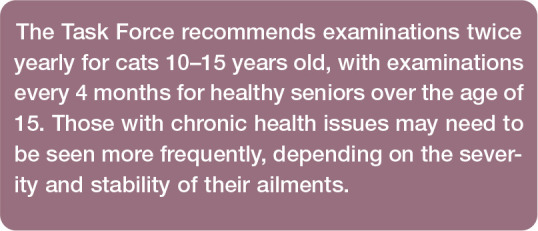

Healthy people are encouraged to have wellness examinations yearly. The life span of a cat is five times shorter than the life span of a human, so an equivalent frequency in a healthy adult cat would be every 10-11 weeks! While this may not be practical, it does emphasize the need for more than one annual examination (see box). The cat’s innate ability to hide ailments makes regular physical examination that much more critical in the elderly cat.

Cats, particularly senior cats, must be handled gently. If it is known beforehand that the cat may be painful or that an examination will be particularly painful, analgesia is appropriate and recommended, as described in the ‘2015 AAHA/AAFP Pain Management Guidelines’. 12 Provide patients that object to handling due to stress or pain with analgesics and/or anxiolytics. If stress or pain cannot be adequately and safely controlled, it may be necessary to abandon and reschedule the examination.

A thorough examination begins by observing from a distance. Simple observation can help detect changes in breathing patterns, gait, stance, strength, coordination and vision. The hands-on physical examination may be conducted in any order, provided it is thorough and painful areas are examined last. To reduce stress, save the most invasive parts of the examination until the end, such as the dental examination, temperature or nail trim, sample collection, and imaging studies. 2

Especially for cats older than 10 years of age, blood pressure (BP) determination at each examination provides essential information. Risk of hypertension increases with age13,14 and is most often recognized in cats 10 years and older. 15 Untreated, hypertension can cause severe target organ damage to the eyes, heart, brain and kidneys,16,17 which may not be reversible. Routine measurements at each examination may help reduce situational hypertension.

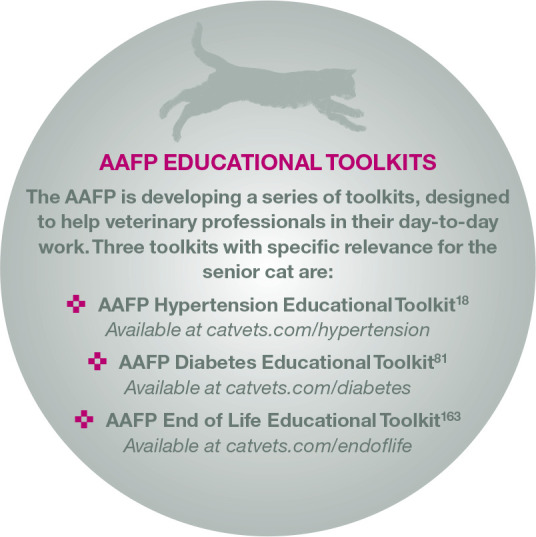

Detailed information on the standard protocol for systemic BP measurement in cats can be found in the AAFP Hypertension Educational Toolkit 18 and ‘ISFM Consensus Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension in Cats’. 17 Blood pressure measurement videos produced by ISFM are available at www.youtube.com/user/iCatCare.

Optimal care can only be planned if a cat’s body weight is measured, and BCS and MCS are determined, at each visit.

For the senior cat, hydration status is extremely important because some of the more common comorbidities, such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) and diabetes mellitus (DM), produce a gradual loss of body fluid. Loss of subcutaneous fat and/or tissue elasticity may influence interpretation of skin tenting results and mucous membrane moisture could be more indicative of hydration status.

Assessment of skin, nails and haircoat includes paying particular attention to the quality of the nails, as they tend to thicken and become ingrown. Offering nurse or technician nail trim appointments provides a resource to owners who are unable to trim nails routinely. Nail quality changes can be particularly problematic for arthritic cats too painful to use a scratching post.

A thorough examination of the nose and mouth includes palpation of the nasal contours, and visualization of the gingiva, pharynx, palate, sublingual area and teeth, carefully noting unusual tooth loss. Additionally, palpation of the area between and under the mandibles may identify tumors or lymphadenopathy. Any asymmetry noted during evaluation of the head warrants closer investigation.

Ophthalmic evaluation includes careful examination of both the anterior and posterior chambers, iris color and shape, as well as the retinal area. Common lesions that progress with aging are lenticular sclerosis, iris atrophy, iris melanosis, focal or linear cataracts19,20 and variable tear production.21,22 Visualization of the retina is especially important for early detection of vascular changes or edema, which are warning signs of hypertension and subsequent retinal detachment.22–24 Sequential evaluations of the eye and concomitant images of lesions, or color and structural changes, will alert a practitioner early on to the possibility of developing neoplasia, and potentially allow lifesaving treatment.

Palpation of the cat’s neck when the cat is sitting with its neck extended or standing with its head elevated and turned to each side will reveal a palpable thyroid gland in 80% or more cases of feline hyperthyroidism (FHT); however, a palpable nodule may also be present in cats with non-thyroidal disease.25–27

Listen to all four quadrants of the thorax during thoracic auscultation to determine heart and respiratory rate, identify heart murmurs or arrhythmias and assess lung sounds. The cranial thorax should be compressible; cranial mediastinal masses can reduce compressibility (ie, absence of cranial rib spring).

Using a gentle technique, attempt to palpate each organ during abdominal palpation, noting evidence of pain or masses, areas of thickened bowel, the amount and consistency of stool, kidney and bladder texture, shape and size, as well as the size and location of identifiable lymph nodes. Palpation of the mammary chain can be incorporated into abdominal examination.

An orthopedic examination can help identify changes in joints, including thickening, fluid, crepitus, pain and range of motion. Gently palpate limbs and joints individually for thickness or tenderness. Some cats may not demonstrate pain nor have crepitus upon palpation. Assess muscle mass and assign an MCS. Pay special attention to areas of muscle atrophy as these can indicate localized painful conditions. Areas of barbering or overgrooming may indicate underlying pain. Overall muscle mass loss seems more indicative of systemic disease.

A myofascial examination is helpful to assess the viscosity, mobility, temperature and comfort of soft tissue structures. If performed correctly, the examination is a soothing, gentle and inquisitive approach to assess pain of multiple origins, including osteoarthritic, spinal, soft tissue and visceral origin. Myofascial examination relies on soft tissue palpation while being attuned to subtle indicators of pain such as changes in body posture, facial expression, strain patterns in muscles or fascia, skin adherence, and heat. Pain detected during a myofascial examination may originate from the surface being palpated or be reflective of pain from internal viscera deeper below the surface.

A video demonstrating myofascial examination is included in the supplementary material (see page 631).

Finally, compare all parameters with those from the last examination to identify trends as early indicators of disease or a degenerative process.

Recommended diagnostics

Regular examinations combined with performing baseline diagnostics can help detect preclinical disease and serve as a reference point to track future trends. Consider performing baseline diagnostics (Table 1) at least annually, starting at age 7-10 years, with frequency increasing with age.

Table 1.

Recommended diagnostics for senior cats

| Baseline tests | Ancillary tests* |

|---|---|

|

Complete blood count: hematocrit, red blood cells, white blood cells, differential count, platelets |

Heartworm antibody/antigen Feline leukemia virus (FeLV)/feline immunodeficiency virus ELISA, FeLV provirus PCR

28

Hematology slide review |

|

Serum biochemistry panel: total protein, albumin, globulin, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, potassium, phosphorus, sodium and calcium as mininum parameters |

Ionized calcium/parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide Cobalamin (B12)/folate Feline pancreatic-specific lipase Fructosamine NT-pro BNP SDMA Trypsin-like immunoreactivity |

|

Optional parameters often included in routinely available commercial panels: aspartate transaminase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, creatine kinase, total bilirubin, chloride, HCO3 or CO2, magnesium |

|

| Urinalysis: specific gravity, sediment, glucose, ketones, bilirubin, protein, urine pH | Urine culture/sensitivity Urine protein:creatinine ratio |

| Total T4 † | Free T4/thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| Blood pressure† | |

| Fecal analysis (centrifugation) | |

| Echocardiogram Electrocardiogram Radiography Ultrasound |

May be indicated by patient health status and/or baseline test results

See discussion in text

The incidence of many diseases increases as cats age, and comorbidities are common. More robust data about disease incidence by age would assist veterinarians in determining the value and desired frequency of testing, but such data are lacking. Veterinarians must therefore rely on clinical judgment and client discussions specific to each individual patient.

Regardless of the cat’s age, more frequent or more expansive diagnostic evaluation (Table 1) is indicated if:

Any abnormalities are noted in the history or physical examination, even if baseline laboratory work appears normal.

Disease is suspected or revealed at routine veterinary visits.

Comorbidities exist that require additional monitoring.

Medications are prescribed.

Assessment and diagnostic evaluation may be necessary every 3-6 months in very elderly patients, those receiving chronic medical management and patients with multiple comorbidities.

When in doubt regarding suspected disease or subtle abnormalities, re-evaluate the patient to establish persistence and/or progression of the abnormality. Biometric data trends in the cat provide invaluable information and are more important than a single data point. Look at the whole patient and view trends in context. For example, progressive increases in BP over time may help differentiate between situational hypertension and true hypertension requiring medical therapy.

Biometric data can also be more powerful when multiple tests are used in conjunction. For example, when evaluating for the presence of CKD, using all available information -physical examination findings, serum creatinine, urine specific gravity (USG), symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA), and diagnostic predictive algorithms, some of which are becoming available as proprietary services (eg, RenalTech; Antech Diagnostics) – is more powerful than simply evaluating serum creatinine concentration alone.

Management tools that optimize health in the aging cat

A healthy senior lifestyle can be supported by the veterinarian through education and conversation with the client. Consideration must be given to making the home environment senior-friendly, guiding the owner in understanding their senior cat’s needs and providing nutritional advice. Where there are no contraindications, preventive care including routine vaccinations, parasite prevention and dental care should be recommended.

Osteoarthritis and spondylosis deformans are the two most common forms of degenerative joint disease (DJD) in cats (Figure 4). 29 Both conditions can cause pain and pain-associated behavioral changes.29,30 Pain can be difficult to identify in cats. With proper guidance, clients can learn to detect changes in their cat’s normal mobility and behavior patterns that are indicative of pain (Table 2). Mobility changes can be subtle, including jumping patterns, house-soiling, changes in sleeping locations, and increased sleeping (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 4.

This 12-year-old cat with DJD is laying with stifle and hock in extension to be more comfortable. Courtesy of Kelly St Denis

Table 2.

Identifying the subtle signs of pain at home and in the practice

| At home | Patterns of behavior | • Changes in interactions with family, visitors, other family pets • Decreased appetite and food intake • Diminished play • Overgrowth of nails signaling decreased scratching behaviors • Changes in normal routines |

| Mobility | • Change in normal resting spaces • Increased sleeping • Decreased jumping • Difficultly climbing stairs, utilizing intermediate surfaces to get to higher surfaces or not going to higher surfaces at all • Sliding down the edge of surfaces to decrease jumping-down height • House-soiling • Lameness (rare) |

|

| Response to touch | • Changes in petting preferences • Sudden dislike of grooming care, perhaps only over one specific physical location • Sudden dislike of being picked up |

|

| In the practice | Personality | • Change in demeanor: less or more approachable • Hiding in carrier when previously came out willingly |

| Mobility | • Altered gait • Changes in jumping (no longer jumping onto examination table, difficulty getting onto examination room chair, etc) • Changes in exploratory behaviors |

|

| Appearance | • Evidence of muscle wasting • Evidence of increased or decreased grooming (alopecia, mats, dull coat) • Nail overgrowth |

|

| Response to touch | • Objects to petting or examination touches | |

| Ability to obtain biologic samples | • Resistant to handling for blood or urine sampling • Changes in behavior compared with previously (eg, no longer comfortable for hindlimb blood draw) |

Figure 5.

When this 11-year-old cat became unwilling to jump up to sit on the cat tree, he was examined and diagnosed with osteoarthritis. Courtesy of Sheilah Robertson

Figure 6.

Subtle increases in sleeping pattern were noted for this 19-year-old cat. Courtesy of Kathleen Neumann

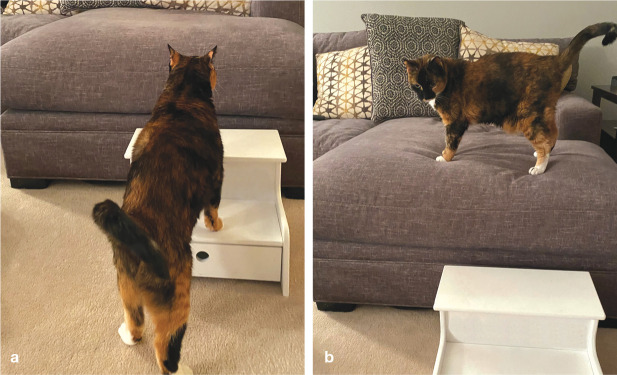

Because age carries an increased risk of DJD 31 and other changes, including cognitive dysfunction, decreased senses, becoming ‘pre-frail’ or frail, and potential health issues, all senior cats will require enhanced care at home. While age alone is not a risk factor for frailty, frailty does become more common as age advances. Tailor care to the individual cat, referencing the five pillars of a healthy feline environment (see later). 8 Educate clients about the importance of providing key resources including litter boxes, food dishes, drinking water, beds, scratching surfaces, hiding spaces and three-dimensional spaces in multiple locations throughout the house.8,9 Encourage clients to provide items that support the aging cat, including night lights for improved visibility in darker areas, ramps and steps for easier access to favorite spaces (Figure 7) and a variety of resting surfaces and spaces. Low-sided, wide-based food and water bowls that do not interfere with the whiskers are ideal for seniors. 32 Senior cats should have safe access to food with minimal distractions and interruptions. Elevation of food bowls may benefit those with DJD, and warmed and/or aromatic foods can entice intake.

Figure 7.

(a,b) This 14-year-old cat with painful DJD uses steps to access a favorite resting place. Courtesy of Heather O’Steen

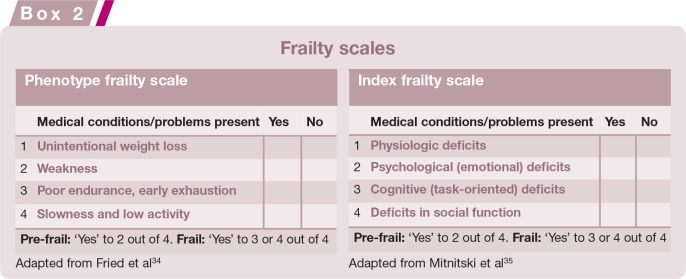

As frailty scales become more well defined (Box 2), interventions to keep the senior cat active and self-sufficient can be taken into the home environment. Although age alone is not a reliable predictor of frailty, many frailty factors become more common with advanced age. 33 As is established for human medicine frailty scales, frailty measurements should be able to identify frail subjects, be supported by a biologic causative theory, and reliably predict adverse clinical outcomes and patient response to therapy and stressors. In an effort to identify frailty factors, readers can utilize the ‘phenotype scale frailty scale’ 34 and ‘index frailty scale’. 35 The former focuses on specific physiologic factors, and the latter allows for incorporation of psychological and social function to identify cognitive decline. Both are resources that are easy to use and repeat with serial assessments. With improved identification of frailty, we can establish corrective actions, physiologically and psychologically. With increased awareness and recognition, predictive factors can be identified.

Obesity in the cat is known to decrease life span; 36 however, with advancing age, weight loss is a more common occurrence. 37 BCSs of <5/9 and of 9/9 are negatively associated with survival and lifespan. 38 Routine nurse or technician visits, and educating clients to monitor body weight, BCS and MCS at home can improve early detection of negative trends.

Gastrointestinal (GI) tract efficiency changes over time in the aging cat. Cats aged 7-11 years will require reduced caloric intake, 39 while cats 12 years of age and older will have increased daily energy requirements (DER).39,40 Food intake can be negatively impacted by cognitive changes, dental disease and systemic disease. 41 Diminished GI tract function in seniors may also lead to consumption of smaller volumes of food at each feeding, with cats over 10 years requiring calorie-dense diets with highly digestible proteins offered in smaller, more frequent meals. 9 Resting energy requirements (RER) can be determined using the following calculation: 42

To determine DER add a factor of 10-20%, although some senior cats may require a factor of 25%. 43 Feeding amounts can be determined based on the energy density and nutrients of the food being fed. Guide clients to record actual intake and report any changes. Slower transit times may predispose senior cats to stool dehydration and constipation. 32 In some cases, use of specific diets 44 or addition of polyethylene glycol 3350 daily to food can be beneficial in promoting good stool consistency. 45

The 2020 AAHA/AAFP Feline Vaccination task force recommended individualized vaccination plans based on five risk assessment variables: age and life stage, health status, agent exposure, history and immunodeficien-cy. 46 Healthy senior cats and senior cats with controlled disease are eligible for vaccination based on these criteria. Although poor health status may increase the risk of side effects, the same cat may be more susceptible to infectious disease and may benefit from vaccination. The veterinarian will need to evaluate these risk variables on a patient-by-patient basis. Refer to the ‘2020 AAHA/AAFP Feline Vaccination Guidelines’ 46 for additional information.

Regular, broad spectrum parasite prevention is recommended by the Companion Animal Parasite Council, regardless of lifestyle. Exposure risks increase when cats spend any time outside, including on patios or in enclosures, or travel for grooming, boarding or other care, and when other household pets have an indoor-outdoor lifestyle. A strictly indoor lifestyle does not eliminate exposure risks, however. Routine protection against common intestinal parasites, heartworm, fleas, and in some cases ticks, is recommended.

Dental disease and associated pain in cats is often unnoticed at home. Clinical signs may include head shaking, pawing at the mouth, tongue thrusting, hypersalivation, or rubbing the head along the ground, 47 but signs are often subtle and not explicitly linked with dental disease. Cats may display vague alterations in activity, appetite and interactions with family, and/or other subtle signs of pain (Table 2). The risk of periodontal disease increases with age, 48 as does the risk of tooth resorption,49,50 making a full dental evaluation an essential component of every senior examination. In the awake patient, this includes extraoral examination of the head as well as intraoral examination. 47 Examination of the entire dental arcade can be difficult in awake cats, and lesions can be missed. For example, tooth resorption is commonly found first in 307 and 407, 49 yet assessing these mandibular premolars can be a challenge in the conscious cat. Cat friendly handling techniques can improve this process. 11 A video showing cat friendly tips for thorough feline dental examinations is included as supplementary material (see page 631).

Complete dental evaluation requires anesthesia and includes thorough extraoral and intraoral examinations as well as dental radiography. 47 Advancing age should not be a limiting factor in proceeding with dental care under anesthesia. 51

Concurrent issues to consider in the aging cat

Anesthesia

Procedures including diagnostic ultrasonography, endoscopy, feeding tube placement and surgery require sedation or anesthesia. Historical data indicate higher mortality rates in cats compared with dogs, as well as in cats over 12 years of age (comparator group 1-5 years). 52 However, risk factors have been identified, and anesthesia practices changed to mitigate adverse outcomes. The ‘AAFP Feline Anesthesia Guidelines’ 53 highlight the importance of stress reduction (eg, previsit gabapentin, cat friendly handling 11 and nursing 54 ) in the perioperative period. Tachycardia is not well tolerated, and diminished cardiac reserve renders the older patient less able to respond to fluid losses or overload. Recommended fluid rates for cats during anesthesia are 3 ml/kg/h to reflect feline blood volume (50-60 ml/kg) and the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; note that this is lower than rates for dogs. 53 The type and volume of fluid used depend on many factors, including the patient’s signalment, physical condition, and the length and type of the procedure. 55

As humans age, the functional capacity of major organs diminishes; the decrease in size of, and blood flow to, the liver and kidneys results in delayed metabolism and excretion of drugs. 56 The decrease in grey matter lowers anesthetic requirements. Loss of muscle mass and diminished thermoregulatory control renders older humans susceptible to hypothermia, which further decreases drug metabolism and prolongs anesthetic recovery. 57 These changes affecting drug metabolism likely occur in cats. If adjustments are not made based on these age-related physiologic changes, the risk of anesthetic overdose dramatically increases.

Hypertension

Hypertension in the cat is well recognized but, due to a paucity of screening, is likely under-diagnosed. 17 Feline hypertension can occur as a primary/idiopathic change, secondary to other disease or secondary to situational stress. 16

Primary/idiopathic hypertension is uncommon in cats and thus detection of hypertension should prompt an investigation for underlying disease. Secondary hypertension may develop in association with CKD, hyperthyroidism, primary hyperaldosteronism, DM, pheochromocytomas and pituitary hyperadrenocorticism. The reader is referred to the AAFP Hypertension Educational Toolkit 18 and the ‘ISFM Consensus Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension in Cats’ 17 for additional details.

Chronic kidney disease

Kidney disease is common in older cats, and often begins in mature adult cats. Diagnosis and management are well documented.58,59 However, a few specifics deserve mention:

Clinical signs of CKD can be overlooked by cat owners, and may include polyuria, polydipsia, inappetence, nausea, constipation, poor haircoat, weight loss and muscle wasting.

Routine laboratory work (screening and evaluation of trends) may reveal early disease. Some patients with serum creatinine concentrations within published reference intervals may actually have CKD. Evaluation of combined data, including creatinine, USG, SDMA, body weight, MCS and hydration status, is important for disease determination. Persistent serum creatinine >1.6 mg/dl (>140 μmol/l), USG <1.035, and SDMA >14 μg/dl are indicative of renal dysfunction.

Interpretation of urinalysis results, particularly USG and protein, is of particular importance in senior cats. Cystocentesis allows for greatest accuracy. If USG is <1.035, then measurement should be repeated on a subsequent sample to confirm persistence. Determine urine protein:creatinine ratio (UPCR) to quantify proteinuria when appropriate (ie, no gross hematuria or inflammation is present).

After diagnosis of CKD is confirmed and the patient is stable and hydrated, International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) staging is performed. Staging is based on repeated assessment of serum creatinine (with consideration for SDMA) and substaging based on BP and UPCR. Staging the patient aids in management of disease, and substaging helps in determining when intervention for hypertension and proteinuria is indicated.

Evaluate nutrition, including a complete dietary history and assessment of caloric intake adequacy. Determine body weight, BCS and MCS. Ask open-ended questions about how the cat is eating. Address poor appetite and optimize caloric intake with anti-nausea and appetite stimulant therapy. 60

Feeding a phosphorus-restricted ‘renal’ diet has been shown to improve CKD-mineral and bone disorder, reduce uremic episodes, and increase survival times. 61 Canned diets provide the benefit of improving hydration. If a cat will not eat a commercial renal diet, a home-cooked diet can be formulated with the help of a nutritionist. Alternatively, a feeding tube can be placed to optimize nutrition and hydration, and assist in medication administration. 61

Address dehydration to promote renal blood flow and prevent constipation. v As CKD is the leading cause of secondary hypertension, BP should be monitored and hypertension should be addressed medically when identified with a goal of returning BP to the normal range.

Investigate and treat electrolyte abnormalities, such as hypokalemia and hyperphosphatemia.

Evaluate for renal proteinuria, which may play a role in disease progression and has been shown to be a negative predictor of survival.62–64 Persistently elevated proteinuria (UPCR >0.4) determined to be renal in origin merits therapeutic intervention.

Monitor for anemia, which is common in CKD and is a negative predictor of survival.63,64 Moderate to severe anemia warrants treatment.

Perform urinalysis and urine culture (when indicated based on urine sediment clinical signs or low USG) to monitor for urinary tract infection (UTI), which is more common in cats with CKD. 65 Low USG is considered a potential factor in increased risk of subclinical UTI even if urine sediment is inactive. 66

When prescribing therapies to CKD patients (eg, oral mirtazapine, gabapentin, fluoroquinolones), keep in mind that renal dysfunction may require dose reduction or alteration of dosing interval.67,68

Once the patient is stabilized, continue monitoring every 3-6 months or more often if indicated depending on individual patient factors.

Balance quality of life with therapeutic interventions to develop a plan that works for clients and patients.

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism affects 10% of cats over 10 years of age. 69 It is treatable, even curable, if detected early. FHT is diagnosed by a combination of clinical signs (eg, weight loss, polyphagia, polyuria, polydipsia, increased vocalization, agitation, increased activity, vomiting, diarrhea, unkempt haircoat, apathy, inappetence and lethargy) 70 and elevated serum thyroid hormone (T4) concentration. Identifying trends in T4 is valuable in establishing an early diagnosis of FHT. Common myths pertaining to the treatment and management of FHT are dispelled in Table 3. For detailed information on treatment options, refer to the ‘2016 AAFP Guidelines for the Management of Feline Hyperthyroidism’. 70

Table 3.

Myths vs facts pertaining to treatment and management of feline hyperthyroidism (FHT)

| MYTH | FACT |

|---|---|

| Treatment of FHT causes kidney disease | Excess T4 increases glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Effective treatment of FHT decreases GFR, unmasking pre-existing CKD |

| Cats with creatinine levels within reference intervals do not have CKD | Increased GFR and muscle loss associated with FHT cause a decrease in creatinine even if a cat has CKD |

| Maintaining T4 slightly above reference intervals will help patients with CKD | Even mild elevations in T4 can cause or exacerbate glomerular damage |

| Post-treatment T4 below the reference interval does not harm cats. The patient is not hypothyroid so long as T4 is in the reference interval | Iatrogenic hypothyroidism can cause progression of CKD and shorten lifespan. Cats can develop clinically significant hypothyroidism even if T4 is within the reference interval |

| Isolation after radioactive iodine (I131) treatment is too stressful on a cat | Although 1 week away from home involves some stress, it is far better than stress associated with the disease itself, plus constant medication and frequent blood testing |

| I 131 is cost-prohibitive | The cost of all treatment options for 1 year is essentially the same. Over the life of the cat the cost of I 131 is significantly less than the cost of disease complications, lifelong medication or prescription diets |

Diabetes mellitus

DM is a common endocrinopathy in senior cats. Most cases are similar to type II diabetes in humans, especially in cats over the age of 10, in which pancreatic beta cell destruction and peripheral insulin resistance are the underlying pathology.71,72 Corticosteroid usage may predispose sensitive individuals.

Nutritional management using low-carbohydrate, high-protein canned food can help these patients if they are receptive. 73 Most diabetic cats are insulin-dependent at the time of diagnosis. The more quickly the cat’s blood glucose normalizes, the greater the likelihood of clinical remission. 74 Other factors found to be associated with an increased likelihood of remission are lower blood glucose at diagnosis, absence of hypercholesterolemia, lower mean 12-h blood glucose at day 17 of treatment and higher insulin-like growth factor at 1-3 weeks post-diagnosis. 75 Long-acting insulins may facilitate reaching this goal. 74 The presence of concurrent diseases, such as pancreatitis, affects clinical remission and glycemic control. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency may occur as a comorbidity in diabetic cats. 76

Monitoring the diabetic cat with in-hospital glucose curves can be difficult in some patients.77–79 Fructosamine evaluates serum glycemic control over longer time intervals and may differentiate between DM and stress hyperglycemia. Recently, continuous glucose monitors have become available and, potentially with feline a1c (glycohemoglobin) monitoring in the future, may facilitate home management.

For more information, see the ‘ISFM Consensus Guidelines on the Practical Management of Diabetes Mellitus in Cats’ 80 and AAFP Diabetes Educational Toolkit. 81

Dental disease

Dental disease is a common but underdiagnosed condition in the feline patient. 51 As many as 70% of cats will experience some form of dental disease by 2 years of age. 51 In patients over the age of 7 years, common forms of dental disease include periodontal disease, tooth resorption, oral tumors and systemic diseases with oral manifestations (eg, CKD, DM). 47 Age correlates significantly with the incidence of periodontal disease 48 and tooth resorption.49,50

The Task Force considers the following to be priorities with respect to dental disease and the senior cat:

Never consider advancing age alone as a barrier to providing optimal dental care.

- Dental radiography is an essential component of dental care in the cat,51,82 including:

- - Full-mouth dental radiography preceding development of a treatment plan.

- - Post-surgical dental radiographs to ensure proper surgical extraction and to document the extraction site (ie, ensure full root extraction, document degree of crown amputation, identify state of alveolar bone secondary to extraction techniques). 51

- - Utilize appropriate analgesia pre-, intra- and postoperatively.

- - Utilize pain scales to assess the success of analgesia (eg, Feline Grimace Scale 83 ).

Gastrointestinal disease

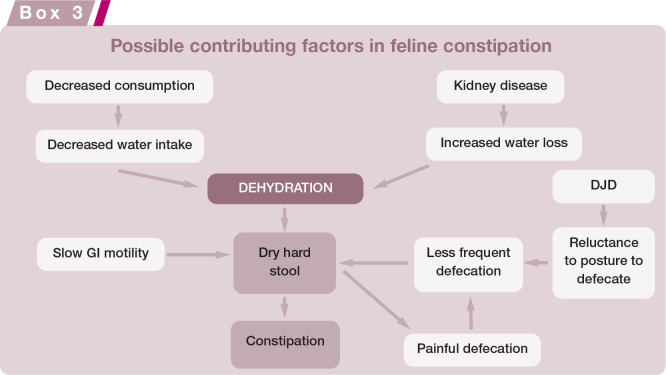

Changes occur in every body system with aging, with some of the more profound changes taking place in the GI tract. Changes in pharyngeal, esophageal and GI motility, and alterations in gastric pH lead to a shift in the GI microbiota, resulting in decreased digestibility and progressive weight loss. 84 Weight loss may be the only sign of digestive system disease in cats. Constipation is also a common GI issue affecting older cats.84,85 Its etiology is likely multifactorial. Hypokalemia can contribute to slow GI motility 85 and constipation may be an indicator of hypercalcemia. 86 The pain of posturing to defecate and passing hard, dry stool potentiates the problem (Box 3). Fecal scoring charts can be utilized for stool assessment.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), neoplasia, pancreatitis ± triaditis, pancreatic insufficiency and parasitism are common considerations for weight loss in the absence of other clinical signs. To obtain a definitive diagnosis, investigation beyond baseline laboratory work is required. Additional diagnostics include abdominal ultra-sonography and serum measurement of feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (fPLI), trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI), cobalamin and folate. A diagnosis of pancreatitis cannot be made by ultrasonography or blood tests alone; but, when performed together, they can increase the likelihood of a correct diagnosis. 87 Similarly, a negative fecal examination for parasites must not be over-interpreted – it only means that none were present in the submitted sample.

Cancer

As cats age, the risk of cancers increases. 88 Signs are often non-specific such as loss of appetite, weight loss or lethargy. Use of cat friendly techniques with gentle and smooth palpation can aid in the quality of information the veterinarian gathers. Be alert for cachexia and paraneoplastic hair loss.

Up to 50 percent of feline cutaneous masses are histologically malignant 89 (commonly mast cell tumors, squamous cell carcinomas, melanomas, fibrosarcomas) and diagnostics should be performed when detected, as delaying diagnosis may lead to a poorer prognosis on account of growth and/or metastasis. Encouraging owners to check all cats monthly for skin masses, documenting location and size, can allow earlier detection.

Many cancers can be treated or ameliorated, especially if detected early. Working with an oncologist will provide up-to-date therapeutic options.

Discussing goals of therapy with owners will help guide recommendations. There has been great progress with chemotherapeutics, radiation and photodynamic therapies, as well as surgical techniques, leading to significant time in remission and increased owner satisfaction. Many cancers can be treated palliatively using less aggressive interventions, slowing growth, and managing pain and nausea to maintain wellbeing. Client education includes discussion about quality of life and available treatments. Route or modality of treatment may be modified in some cases to best suit the patient and/or owner. Providing information on ranges of response to therapy, evaluating the cat’s acceptance of treatment regimens, and estimating costs will help owners make the most appropriate treatment decisions for their cat and themselves.

Ongoing sources of pain

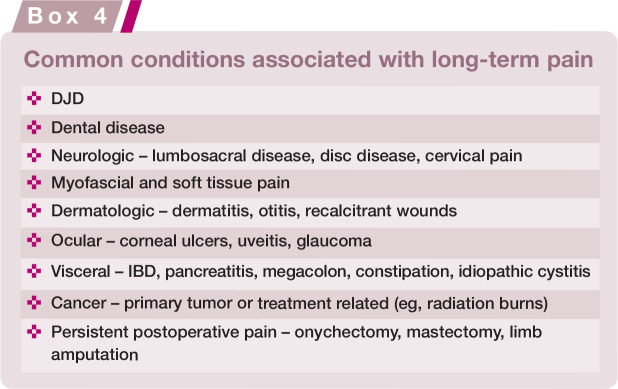

Many of the conditions discussed in these Guidelines involve a component of pain. Pain must be investigated and managed as a disease in itself and treated concomitantly with the primary presenting problem(s). Assessing chronic pain in cats is challenging, but our ability to do so is rapidly improving. 90 There are multiple causes of ongoing pain in senior cats (see Box 4), and the pain experience may escalate when more than one condition is present due to amplification of the pain-sensing system. DJD, soft tissue, inflammatory and neurologic pain are important to discuss as they are a frequent cause of ongoing discomfort in senior cats.

DJD is a chronic degenerative disease affecting the appendicular and axial skeleton. 91 Its prevalence is strongly related to age, affecting up to 74% of cats ≥12 years of age.91,92 The disease is multifaceted; peripheral and central changes result in maladaptive pain. Maladaptive pain serves no purpose (ie, is not protective) and can be further divided into neuropathic pain (direct damage to neurologic tissue) and functional pain (malfunction of the nociceptive system). 93

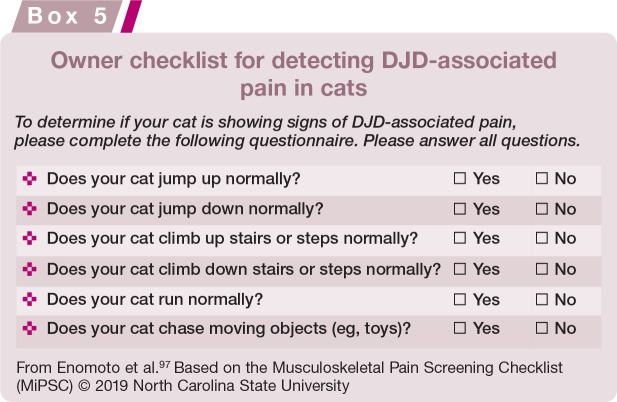

Many cats with DJD are undiagnosed and go untreated. Diagnosis depends on client-based questionnaires,94–96 history, an orthopedic, neurologic and myofascial examination, radiographs, and, in some cases, response to a treatment trial. Clinically expedient screening tools will increase the likelihood of identifying affected cats; one such tool comprises six questions (Box 5). 97 The answer to ‘how is your cat jumping up and down compared with last year?’ can alert a clinician to whether or not they need to pursue a DJD work-up. A comprehensive resource for veterinarians and cat owners is the Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Index (FMPI; painfreecats.org).

DJD is currently incurable and requires lifelong treatment to maintain comfort, mobility and quality of life. With this comes challenges related to owner aversion and poor compliance, adverse effects of long-term medication, drug interactions and the impact of comorbidities. The complex etiology of DJD-related pain demands a multimodal and integrative approach involving pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapies, and environmental modification.

Veterinarians prescribe a wide variety of drugs and supplements for cats with DJD, despite a limited evidence base for many. 93 Drugs with published efficacy include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), 98 gabapentin 99 and tramadol;100,101 however, most studies were designed to look at monotherapy. Approximately 68% of cats with DJD have some degree of CKD, 102 making the use of NSAIDs in this population controversial. Retrospective studies showed no adverse effect on renal function (sequential serum creatinine concentration and USG) or longevity in cats with stable CKD (IRIS stages 1-3) receiving meloxicam at a median daily dose 0.02 mg/kg.103,104 No adverse effects were reported in cats with CKD (IRIS stages 1-2) given robenacoxib 1.0-2.4 mg/kg q24h for 28 days in a prospective study. 105 However, a recent prospective study (meloxicam 0.02 mg/kg q24h for 6 months or placebo) in cats with CKD reported a higher UPCR at 6 months in meloxicam-treated cats. 106

Emerging treatments (eg, feline-specific monoclonal anti-nerve growth factor antibodies) address the neuropathic component of the disease and overcome the problems of daily treatment because they are administered sub-cutaneously once every 4-6 weeks. 107

Soft tissue pain occurs with restriction of tissue mobility related to multiple disease states (eg, DJD, oral and visceral pain states, and direct injury to soft tissue structures). Myofascial palpation assesses tissue viscosity and mobility, and will elicit a response from the cat (eg, vocalization, turning, escape attempt) if pain is present. Soft tissues become restricted when movement is reduced, or inflammation is present. Exercise, massage, acupuncture, shock wave therapy and vibration are the definitive treatments for painful soft tissue restriction.

Neurologic pain is common in aging cats, especially at the lumbosacral and pelvic regions of the spinal cord. This type of pain is often maladaptive and difficult to treat. Neurologic conditions may remain localized or may be accompanied by pain and dysfunction of somatically related visceral structures (eg, colonic dysfunction and megacolon with lumbosacral disease).108,109

Inflammatory pain is a feature of many feline diseases. Aging cats appear to experience amplified changes in their immune system that may predispose them to comorbidities.

Cognitive dysfunction syndrome

Aging cats often exhibit excessive vocalization, altered social interactions or activity patterns, and house-soiling.110–112 In over 25% of cats 11 years or older, these changes have no recognized medical causation.111,113 Because feline motivations can be occult, inter- and intra-cat differences abound; also changes appear gradually and mimic adaptive responses to chronic pain. 114 Owners and veterinarians may, therefore, blame cognitive dysfunction syndrome (CDS) on ‘just being an old cat’. If veterinarians strongly urge owners to record and serially review pictures and videos of their cat’s daily routines, changes for each cat become apparent earlier.

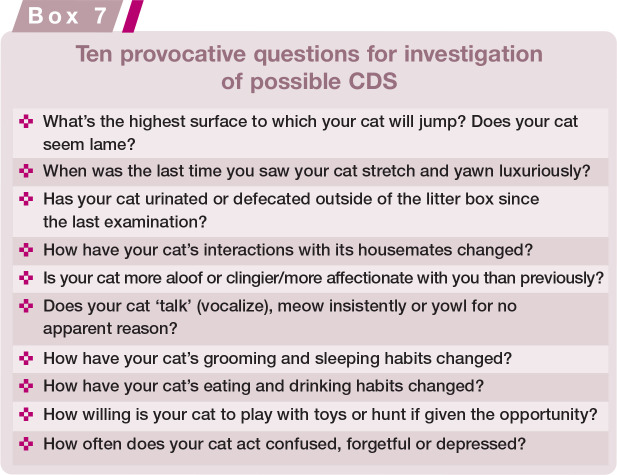

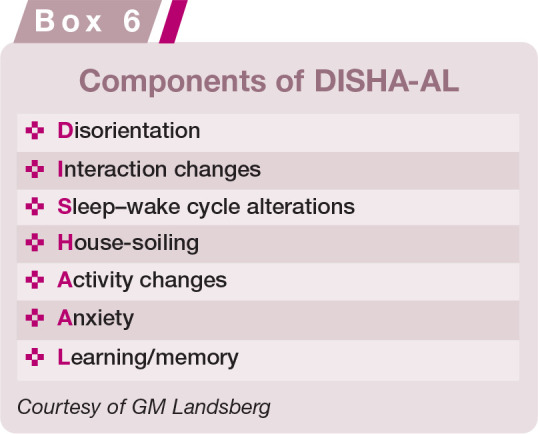

The acronym DISHA-AL (Box 6) has been used to describe clinical signs of cognitive decline. Provocative questions (Box 7) to identify components of DISHA-AL and the subsequent clinical work-up can distinguish medical from cognitive decline. CDS ultimately is a diagnosis of exclusion of medical and environmental causes for the behaviors.9,112

If management that integrates client education, environmental optimization8,9,115 (see later in Table 5), supplements with essential fatty acids, antioxidants and B vitamins,116–118 and pheromones 119 fails to bring improvement, selegiline (0.25-1 mg/kg q24h) may be beneficial.120,121 Individualized combination therapy is most effective and can improve brain function, longevity and owner peace of mind. 9

Table 5.

Environmental changes to make the activities of daily living possible, or easier, for aging cats and those with health-related challenges

| Health issue | Provide | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

|

DJD Sarcopenia |

□ Steps or ramps to access elevated places □ Low entry/easy access litter box □ Assisted grooming □ Raised food and water bowls □ Warm resting sites |

✓Maintains access to a safe place ✓ Maintains toileting habits ✓ Maintains coat hygiene ✓ Easier to reach essential resources, and maintains caloric intake and hydration ✓ Maintains body heat |

|

DM CKD |

□ Multiple, various configuration drinking stations in different locations throughout the home | ✓Provides easy access to water all of the time |

| CDS | □ Stable environment: do not rearrange the cat’s major resources (food, water, litter boxes) | ✓Assists the cat to locate essential resources |

Complex disease management

Comorbidities are common in gerontology, and cats are much like humans in this tendency. 122 Reasons for the high frequency of comorbidities as cats age remain speculative, but this likely relates to a combination of exogenous stress causing oxidative injuries, infectious agent exposure over time, and imbalance of the immune system.123,124 As homeostasis of the immune system falters, immunosenescence (reduced sensitivity to external pathogens) and hypervigilance of autologous tissues can occur together and are sometimes referred to as ‘inflammaging’ changes. 125

While specific inflammaging discussion is largely restricted to the human gerontology literature, the Task Force feels the concept of frailty helps capture a component of the complex conditions that can coalesce in the cat. The concept of a ‘frailty prevention model’ delineates three levels of intervention: 1) primary – ie, minimize risk factors and disease onset; 2) secondary – delay progression of disease; and 3) tertiary – reduce or limit impairments, disabilities and complications that result from disease. By the time cats enter their senior years, the first two levels are behind them. The focus now is on the third category of reduction and limitation of impairment.

The goal of healthy aging has been with us since a time when cats seldom reached old age. Now that substantial progress has been achieved in increasing longevity, focusing on the quality of that longevity is important. Although healthy aging means different things to different people regarding both themselves and their cats, and one’s perspective of healthy aging often changes with time and circumstances, comfort and enjoyment of life are likely to be common targets. It is also important to recognize that that an owner’s expectations for a cat will reflect the owner’s own attitude toward healthy self-aging.

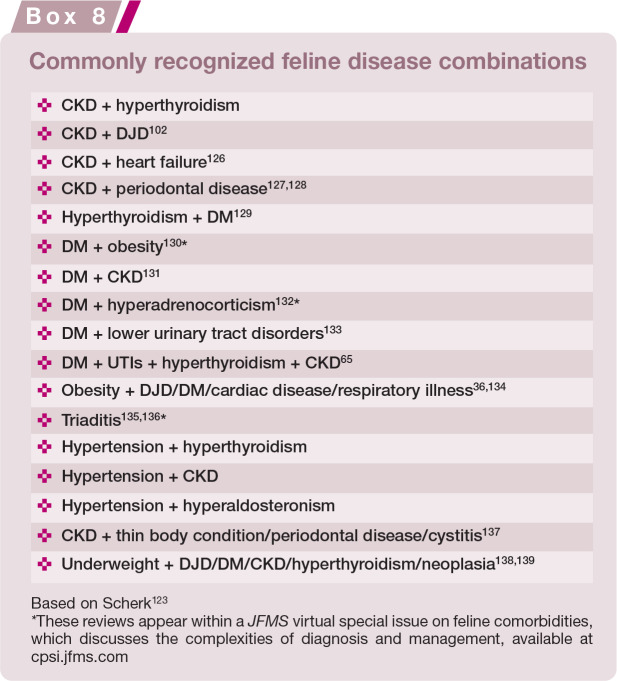

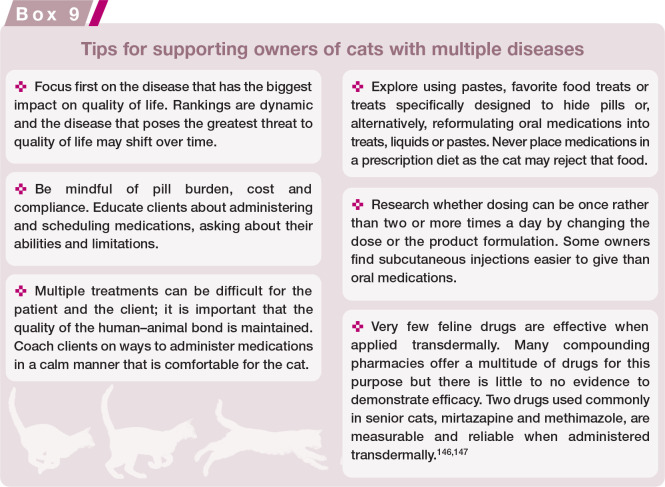

As cats get older, the risk of developing more than one disease increases, often complicating diagnosis and treatment. Diagnosis is aided by a combination of a thorough physical examination, screening diagnostic testing, and attention to the common comorbidities listed in Box 8.

As the number of concurrent disease conditions increases, a related decrease in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) occurs. 140 Some of the issues that arise in senior cats with multiple diseases include:

The effect of polypharmacy and risk of drug interactions. Reduced renal or hepatic clearance can require reduced dosing or increased intervals of medications. 141

Owner aversion and poor compliance to the medical plan, particularly where there is a high medication burden, risking negatively impacting the cat-owner bond.

The effect of diet on body condition, inflammatory homeostasis, GI function, kidney function and overall health.

The cumulative impact of multiple diseases. For example, CKD, DJD, DM, IBD, CDS and behavioral issues, when present in any combination, can compound inappropriate elimination.

Hypertension. This may occur with various disease states (thyroid, cardiac, renal) and is much more common than previously recognized.

- A risk of diagnosing one disease while missing another, or assuming a single disease is severe when signs are actually due to multiple diseases. For example:

- - When cholangitis, pancreatitis and/or IBD occur together, one or more may be missed. 142

- - Hyperthyroidism may be missed in cats with DM due to similarity in signs.

- - The diagnosis of bacteriuria in cats with kidney disease, hyperthyroidism or diabetes can be complicated because signs of lower urinary tract disease, pyuria and/or active urine sediment are not always present. Diagnosis can only be confirmed by performing a urinalysis and bacterial culture. 65

- - Hyperthyroidism and cardiac disease may occur together, with only one being recognized.

- - Most diseases have a component of pain, complicating the assessment of other sources of pain, such as DJD, soft tissue or neurologic, when using standardized pain scales. Myofascial examination is a partial solution to this diagnostic dilemma.

- - The impact of comorbid conditions on quality of life fluctuates (eg, during chemotherapy, nausea may be worse than pain).

- - Pain severity will change throughout the cat’s remaining lifetime depending on the disease and its progression, response to treatment, inflammatory status and lifestyle modifications. Complex disease management may feel overwhelming for a general practitioner; however, they are often best suited to oversee the cat’s care as they see the ‘whole picture,’ have a rapport with the owner, and can consult or refer the cat to specialists when needed. The presence of multiple diseases can likewise be overwhelming for clients, and an important component of the care veterinarians provide includes supporting the owner (see Box 9).

Ancillary therapies include environmental enrichment and modification as well as physical medicine treatments such as physical therapy, acupuncture, massage and electrophysical modalities. Many positive forms of activity can be instituted at home, and regular attendance at physical medicine sessions at a facility can be rewarding for both the cat and their owner. Involving owners as part of the treatment team, and making them feel they are part of the solution, promotes buy-in; it also increases the time the cat and owner spend together. Assigning owners duties that support positive interactions such as grooming or playing will decrease the risk that the cat will only associate the owner with receiving treatment.

Controlled exercise – when performed with appropriate restrictions, continuity and regularity – produces analgesia, similar to a pain medication. 148 Regular physical activity conveys multiple benefits – influencing gastric and colonic motility, balancing immune status, reducing seizure breakthrough, and improving appetite and cognition. 149

As many of the coalescing conditions in senior cats are likely related to imbalances in neuroimmune homeostasis, it is important to prioritize an approach that emphasizes quality of life and use of non-pharmacologic treatments, alongside pharmacologic treatments and appropriate monitoring.

Quality of life

‘How will I know it’s time?’ is one of the most frequently asked questions by owners. Assisting owners in making the decision to euthanize their cat is an essential part of our job. Comorbid diseases and their treatments, as well as physical challenges related to aging, impact quality of life. More therapeutic interventions and radical surgical procedures are now available to prolong life, but we must put the patient’s best interests first despite pressure from owners. 150 Just because we can, does not mean we should, and quality rather than quantity of life is a priority. Cats live in the moment and, unlike people, cannot know that ‘tomorrow may be better’ while going through unpleasant treatments. Our patients do not make choices for themselves; this falls on the owner and we must partner with them to make good, well-informed patient-centric decisions.

Animals, newborns, infants and cognitively impaired people cannot self-report and, therefore, patient-reported outcome instruments cannot be used.151,152 Despite wide usage, the term quality of life (QOL) with respect to animals does not have a universally consistent or accepted definition, which has hampered our ability to measure it. Most people have a general understanding of what is meant by the term QOL, but it is surprisingly difficult to verbalize. 153 One working definition is ‘an individual’s satisfaction with its physical and psychological health, its physical and social environment and its ability to interact with that environment’. 152 ‘Health’ is the state of being free from illness or injury and ‘satisfaction’ is the fulfilment of one’s individual needs or state of positive mood. 152 When the veterinary team shares an understanding of what QOL means, owners are supported with consistent guidance for assessing QOL in their cats.

QOL and HRQOL are different. QOL is a broad term and considers all aspects of a pet’s life, which includes physical and mental health. HRQOL refers to the specific impact of a medical condition on an individual’s health. An HRQOL instrument is able both to detect disease (be discriminative) and measure health changes over time (be evaluative). 154

How do we take something internal, private and uniquely individual and make it accessible, objective and measurable? As observers, we cannot validly report on a cat’s pain intensity, but we can report behavioral changes thought to be a result of pain. Therefore, QOL can only be assessed in cats using proxy reports or direct observations; the proxy may be the owner, a veterinary professional or a combination of the two. These are referred to as observer-related outcomes.

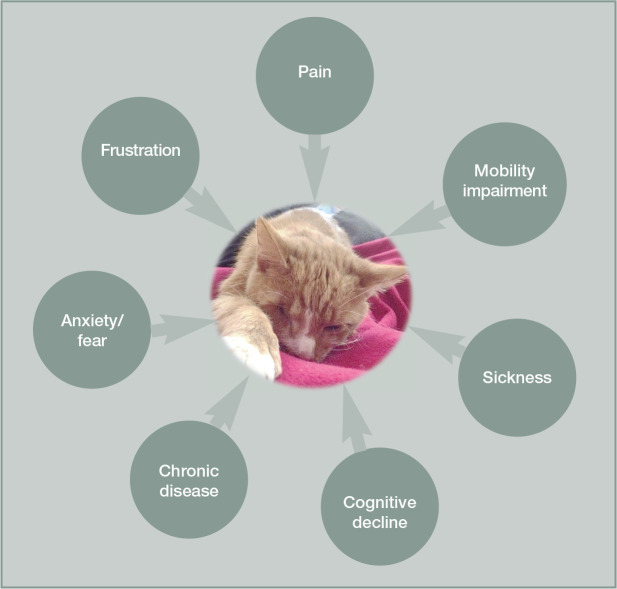

Pain is an affective state (emotion) and is always unpleasant but is not the only unpleasant feeling associated with chronic disease. Other things to consider are shown in Figure 8 and Table 4.

Figure 8.

Quality of life considerations. Courtesy of Sheilah Robertson

Table 4.

Examples of mental/emotional and physical states that contribute to a poor QOL

| Example | |

|---|---|

| Mental/emotional | Anxiety |

| Fear | |

| Isolation and loneliness | |

| Boredom | |

| Frustration | |

| Distress | |

| Physical | Chronic (maladaptive) pain (eg, DJD, dental disease, non-healing wounds) |

| Nausea and vomiting (eg, secondary to CKD) | |

| Breathlessness (eg, respiratory disease, congestive heart failure) | |

| Thirst (eg, uncontrolled DM, CKD) | |

There is some urgency to develop evidence-based assessment tools to inform clinical decision-making. Using expert consensus, feline welfare issues in the UK, both on an individual and population level, have been prioritized. 155 The priority (ranking) of issues was determined by judging their severity and duration. Pertinent to these ‘2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines’ is that out of the top 10 welfare issues identified, diseases of old age were ranked second in priority, and delayed euthanasia was listed second for prevalence. 155

In veterinary medicine, owner questionnaires and clinician-completed observation scales are frequently used to objectify the subjective. 156 Outcome assessment instruments must have specific attributes:

Validity: proven to measure what is intended. This requires an accepted definition of what is being measured.

Reliability: close agreement between different observers

Responsiveness and sensitivity: ability to detect clinical changes over time or after treatment

Developing robust instruments to assess subjective states requires specific psychometric methodologies, which are time-consuming but worthwhile.153,157,158 Which questions we should ask in relation to feline quality of life ultimately depends on knowing what matters to each cat. Detailed information on QOL and HRQOL instruments is provided in the supplementary material (see page 631).

Environmental changes

Maintaining the five pillars of an appropriate environment requires modification to the cat’s home or lifestyle in the face of aging or disease. The five pillars are described in detail in the ‘2013 AAFP and ISFM Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines’, 8 and are summarized in Figure 9. Environmental changes and changes in care that may be required for aging cats are summarized in Tables 5 and 6.

Figure 9.

The five pillars of an appropriate environment

Table 6.

Suggested enhanced care for aging cats

| Enhanced care | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Flavor enhancers Strong smelling food | With age, sensory function declines, including smell |

| Regular nail trimming | Nails are more brittle and scratching behaviors may be decreased due to DJD |

| Assisted grooming | Self-grooming may be inhibited by DJD |

End of life

Palliative and hospice care

In human medicine, when a life-ending diagnosis is made, the conventional default has been to treat and prolong life, but with the growth of palliative care and hospice specialists, there are now options on how ‘the end will be’. Palliative and hospice care are still relatively new specialties in human medicine and even newer in veterinary medicine. 159 The general public often believe hospice is ‘a place’ and means ‘giving up.’ There is a clear need to educate people on what is really the case – for cat owners, a possibility of their cat living well until the end.

Palliative care addresses the treatment of pain, mobility impairment, nutritional deficits, anxiety and other clinical signs such as nausea and vomiting to achieve the best quality of life regardless of disease outcome (eg, ‘comfort care’ with or without curative intent). It applies to curable or chronic conditions as well as end of life care, and it may be provided to patients of any age and at any time during the course of an illness. Palliative care includes supporting owners caring for their pet(s) and helping them make decisions.

Hospice care is a specialized form of palliative care that focuses on caring for patients during the end stages of an illness. In veterinary medicine this can include comfort care without curative intent, either because there are no options, or the owners have chosen not to pursue treatment because the likelihood of success is small, the side effects outweigh the benefits, or it is beyond their financial budget. Hospice care for feline patients does not preclude euthanasia and can be looked at as bridging the gap between a terminal illness and euthanasia; it may constitute a short (days) or longer (weeks to months) period of time. Hospice care also includes supporting the pet’s family.

The budgets of care

Some disease-specific QOL questionnaires consider the cat itself as well as the cat’s owners. 159 A tool developed to examine the impact of skin disease showed that QOL was different between healthy cats and those with allergic dermatitis, and that in the latter group QOL improved with treatment. 160 Disturbed sleep, dislike of treatments, changes in appetite and disrupted daily routines contributed to poor QOL. For owners, the psychologic consequences of caring for cats with skin disease included feelings of sorrow, frustration, guilt and stress related to administration of medication or treatments. Caring for these cats takes time and money, and the human-animal bond may be negatively impacted. The severity of the cat’s disease correlated significantly with the owner’s QOL. 159

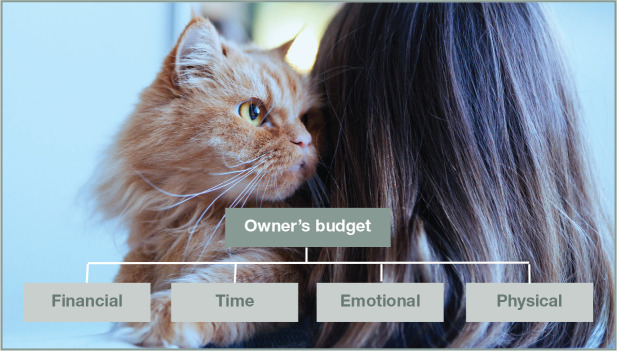

It is important to consider the impact of a cat’s illness on the owner. The Task Force recognizes that cat owners have four budgets that must all be considered when making treatment plans, including euthanasia: financial, time, emotional and physical (Figure 10). The ‘weight’ that each of these carries will vary among different owners and these budgets, combined with the pet’s QOL, will guide clinical decisions.

Figure 10.

The four budgets of care. Courtesy of Sheilah Robertson

Ethical decision-making and difficult conversations

When a serious illness is diagnosed, our duty is to be honest with the client, but many find this type of news difficult to deliver. Owners may request life-prolonging treatments that we feel are futile and harmful, resulting in significant ethical stress.150,161 If the approach to ethical decision-making was less subjective and personal, it might be possible to decrease some stress within our profession. A veterinary working group set up by the European College of Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia has created the ‘Veterinary Ethics Tool (VET)’ to assist in ethical decision-making. It employs a series of checklists and tables, and uses a traffic light system with green (valid reasons for the clinical procedure), orange (reconsider procedure and your responsibilities) and red (consider alternative treatment options) to guide the veterinarian. 162

The ‘Serious Veterinary Illness Conversation Guide’ is another resource based on similar recommendations developed for human physicians dealing with patients at the end of life. 160 Serious illness conversation guidelines and checklists can help keep us on track, navigate complex issues and develop a plan to move forward. A key component of this conversation is to ask the owner what their cat would want given the situation they are in; this helps reframe the owner’s thought process away from what they want. It is important to use the correct gender and name of the cat during these conversations.

Anticipatory grief

Anticipatory grief is a normal process through which those who will be left behind may begin experiencing emotional changes associated with death. Anticipatory grief has many of the hallmarks of grief experienced after a loss, and may lessen the intensity of grief reactions after the actual death. 163 The impact of losing a pet on individuals or families must not be underestimated. Proactively supporting families during this time is important and can include providing resources or referrals to grief counselors. The veterinary team can provide information so owners can prepare for what is to come; for example, explaining the euthanasia process removes elements of the unknown.

Euthanasia

Euthanasia is a humane endpoint; it is a treatment option for a sick cat, not a failure. End of life decisions are among the hardest decisions owners make. How well veterinarians conduct the ‘last appointment’ and support the owners impacts if they obtain another pet and return as clients. The AAFP has created an End of Life Educational Toolkit 164 that contains practical information about decision making, QOL, the euthanasia process, euthanasia experience, final arrangements, FAQs and client resources.

Summary Points

Cats are living longer and may mirror the aging process in their owners’ lives; hence they are often an integral part of their caregivers’ lives, giving hope and emotional support that an owner wants to preserve.

Senior cats deserve the best possible care veterinary professionals can offer. This Guidelines document reflects a knowledge of senior cat care that allows the veterinarian to integrate compassion and dignity with outstanding behavioral, psychological and medical recommendations. It utilizes the greatly increased diagnostic and therapeutic options that are more widely available today.

Discussions with owners throughout a cat’s senior years allow veterinarians to set the stage for optimal feline aging, help the owner to understand what the cat may experience and suggest modifications at home that ease the cat’s transition toward life’s end.

Owners who are aware of what behaviors and activities to observe, and the significance of various changes in these behaviors, can then choose which tests and treatments may be most beneficial to the cat, while causing the fewest burdens.

By building a trusting bond, the veterinarian and owner can ensure that major decisions truly represent an understanding of what is best for each individual cat.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jfm-10.1177_1098612X211021538 for 2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines by Michael Ray, Hazel C Carney, Beth Boynton, Jessica Quimby, Sheilah Robertson, Kelly St Denis, Helen Tuzio and Bonnie Wright in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-jfm-10.1177_1098612X211021538 for 2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines by Michael Ray, Hazel C Carney, Beth Boynton, Jessica Quimby, Sheilah Robertson, Kelly St Denis, Helen Tuzio and Bonnie Wright in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-jfm-10.1177_1098612X211021538 for 2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines by Michael Ray, Hazel C Carney, Beth Boynton, Jessica Quimby, Sheilah Robertson, Kelly St Denis, Helen Tuzio and Bonnie Wright in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-4-jfm-10.1177_1098612X211021538 for 2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines by Michael Ray, Hazel C Carney, Beth Boynton, Jessica Quimby, Sheilah Robertson, Kelly St Denis, Helen Tuzio and Bonnie Wright in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-5-jfm-10.1177_1098612X211021538 for 2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines by Michael Ray, Hazel C Carney, Beth Boynton, Jessica Quimby, Sheilah Robertson, Kelly St Denis, Helen Tuzio and Bonnie Wright in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-6-jfm-10.1177_1098612X211021538 for 2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines by Michael Ray, Hazel C Carney, Beth Boynton, Jessica Quimby, Sheilah Robertson, Kelly St Denis, Helen Tuzio and Bonnie Wright in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-7-jfm-10.1177_1098612X211021538 for 2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines by Michael Ray, Hazel C Carney, Beth Boynton, Jessica Quimby, Sheilah Robertson, Kelly St Denis, Helen Tuzio and Bonnie Wright in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-8-jfm-10.1177_1098612X211021538 for 2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines by Michael Ray, Hazel C Carney, Beth Boynton, Jessica Quimby, Sheilah Robertson, Kelly St Denis, Helen Tuzio and Bonnie Wright in Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery

Acknowledgments

The Task Force gratefully acknowledges the contribution of Dr Kathleen Neumann in the preparation of the Guidelines manuscript.

Appendix: Client brochure

Footnotes

Hazel Carney is a speaker for Royal Canin. Jessica Quimby is a key opinion leader for Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA, Inc., Dechra, Elanco, Gallant Health Care, Heska, Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Inc., IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., Kindred Biosciences, Inc., Purina ProPlan Veterinary Diets, Royal Canin, and Zoetis Petcare. Sheilah Robertson acts variously as a key opinion leader, speaker and consultant for Elanco, Zoetis Petcare, and Jurox. The other members of the Task Force have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: These Guidelines were supported by an educational grant to the AAFP from Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc., IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., Merck Animal Health, Purina Pro Plan Veterinary Diets, Royal Canin, and Zoetis Petcare. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore ethical approval was not specifically required for publication in JFMS.

Informed consent: This work did not involve the use of animals (including cadavers) and therefore informed consent was not required. For any animals or people individually identifiable within this publication, informed consent (verbal or written) for their use in the publication was obtained from the people involved.

- Video demonstrating myofascial examination technique.

- Video showing cat friendly tips for thorough feline dental examinations.

- Information on QOL and HRQOL instruments.

- Client brochure (see Appendix, page 637).

-

Recommended resources.Supplementary materials that can be found at catvets.com/senior-care, in addition to the resources listed above, include ‘Why are comorbidities the “new” norm for cats?’ 123 and a video demonstrating pain when jumping.

Contributor Information

Michael Ray, The Cat Clinic of Roswell, Roswell, GA, USA.

Hazel C Carney, WestVet Emergency and Specialty Center, Garden City, ID, USA.

Beth Boynton, College of Veterinary Medicine, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, CA, USA.

Jessica Quimby, The Ohio State University, Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, Columbus, OH, USA.

Sheilah Robertson, Senior Medical Director, Lap of Love Veterinary Hospice, Lutz, FL, USA.

Kelly St Denis, Brantford, ON, Canada.

Helen Tuzio, Forest Hills Cat Hospital, Middle Village, NY, USA.

Bonnie Wright, Mistralvet, Johnstown, CO, USA.

References

- 1. Pittari J, Rodan I, Beekman G, et al. American Association of Feline Practitioners: senior care guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 763–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Quimby J, Gowland S, Carney HC, et al. 2021. AAHA/AAFP feline life stage guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2021; 23: 211–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Neill DG, Church DB, McGreevy PD, et al. Longevity and mortality of cats attending primary care veterinary practices in England. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 17: 125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Egenvall A, Nødtvedt A, Häggström J, et al. Mortality of life-insured Swedish cats during 1999-2006: age, breed, sex, and diagnosis. J Vet Intern Med 2009; 23: 1175–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ali S, Garcia JM. Sarcopenia, cachexia and aging: diagnosis, mechanisms and therapeutic options – a mini-review. Gerontology 2014; 60: 294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Freeman LM. Cachexia and sarcopenia: emerging syndromes of importance in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med 2012; 26: 3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laflamme DP. Understanding the nutritional needs of healthy cats and those with diet-sensitive conditions. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2020; 50: 905–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ellis SLH, Rodan I, Carney HC, et al. AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 219–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miele A, Sordo L, Gunn-Moore DA. Feline aging: promoting physiologic and emotional well-being. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2020; 50: 719–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scherk M. (ed). Feline practice: integrating medicine and well-being (part 1). Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2020; 50: 653–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodan I, Sundahl E, Carney H, et al. AAFP and ISFM feline-friendly handling guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 364–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]