Abstract

The aim of this research was to study whether and to what extent Chinese cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori isolates differ from those in The Netherlands. Analysis of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD)-PCR-assessed DNA fingerprints of chromosomal DNA of 24 cagA-positive H. pylori isolates from Dutch (n = 12) and Chinese (n = 10) patients yielded the absence of clustering. Based on comparison of the sequence of a 243-nucleotide part of cagA, the Dutch (group I) and Chinese (group II) H. pylori isolates formed two separate branches with high confidence limits in the phylogenetic tree. These two clusters were not observed when the sequence of a 240-bp part of glmM was used in the comparison. The number of nonsynonymous substitutions was much higher in cagA than in glmM, indicating positive selection. The average levels of divergence of cagA at the nucleotide and protein levels between group I and II isolates were found to be high, 13.3 and 17.9%, respectively. Possibly, the pathogenicity island (PAI) that has been integrated into the chromosome of the ancestor of H. pylori now circulating in China contained a different cagA than the PAI that has been integrated into the chromosome of the ancestor of H. pylori now circulating in The Netherlands. We conclude that in China and The Netherlands, two distinct cagA-positive H. pylori populations are circulating.

Helicobacter pylori infection in humans is one of the most widespread infections today, and its cure prevents peptic ulcer recurrence (26, 35). Besides asymptomatic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease (PUD), H. pylori infection is strongly associated with gastric cancer, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), and adenocarcinoma of the stomach (3, 9, 24).

The heterogeneity of the clinical outcome of H. pylori infection may be related either to differences among the hosts or to differences in virulence among H. pylori strains. The latter assumption is supported by the finding that the product of cytotoxin-associated gene A (cagA) has been found to be associated with PUD (7). PUD patients are virtually all infected with cagA-positive H. pylori and have serum antibodies as well as antibodies at the mucosal level against a 120- to 128-kDa protein encoded by this gene (7, 38). In contrast, only 60% of the patients with functional dyspepsia (FD) are positive for this protein. The presence of cagA-positive H. pylori is also related to an increased risk to develop atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (16, 35), or gastric cancer (25).

Recently, the complete genome sequence of H. pylori has become available (30). A 40-kb region of the H. pylori chromosome containing cagA was sequenced earlier by Censini et al. (4). This locus, comprising at least 40 genes, has a GC content different from that of the rest of the chromosome, forms a so-called pathogenicity island (PAI), and is assumed to have been integrated into the H. pylori chromosome only recently (4, 6). The proteins encoded by the PAI genes possess features similar to those of bacterial type II, type III, and most notably type IV secretion systems. It was hypothesized that such proteins may function to export macromolecules that may be involved in the H. pylori-host cell interaction (6).

China is one of the countries with a high prevalence of H. pylori infection and a high incidence of gastroduodenal diseases (39). The prevalence of H. pylori infection increases with age to about 70% of the people over 30 years old (22, 33, 39). The prevalence of cagA-positive H. pylori populations in Chinese patients with PUD and FD is almost universally high (21). Data obtained from this recent study further suggested that H. pylori genotypes distinct from those present in Western Europe may circulate in China.

The aim of this study is to investigate this hypothesis by comparison of the random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD)-PCR-assessed genotype of 24 randomly collected cagA-positive H. pylori isolates from 12 Dutch (14 isolates) and 10 Chinese patients. We used four different primers in each of four amplifications of H. pylori genomic DNA. In addition, part of cagA and glmM of the H. pylori isolates was sequenced. Sequences were analyzed for similarity by a computer-based program by using the neighbor-joining algorithm of Saitou and Nei (27).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and H. pylori isolates.

In this study, 24 cagA-positive H. pylori isolates, 14 from 12 Dutch patients (5 with PUD and 7 with FD) and 10 from 10 Chinese patients (5 with PUD and 5 with FD), were used. Isolates were randomly collected from the collection present in the Department of Medical Microbiology, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. From two Dutch patients, two H. pylori isolates were analyzed. These isolates were cultured from biopsy specimens taken with 6-year (isolates 79A and 79J) and 4-year (isolates 161A and 161L) time intervals, respectively. Culture of the H. pylori isolates and assessment for the presence of cagA by PCR and Western blotting were recently described (21, 38).

Preparation of genomic DNA for PCR.

The chromosomal DNA of H. pylori was prepared as previously described (32). Briefly, stored bacterial suspensions were thawed, inoculated on horse blood agar plates, and cultured at 37°C for 3 days in a microaerobic environment. Bacteria were harvested, and genomic DNA was extracted by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and ethanol precipitation (32).

Genome typing by RAPD-PCR.

PCR-based RAPD fingerprinting was performed by the method of Akopyants et al. (1), with minor modifications (32). Briefly, 20 ng of chromosomal DNA and 5 pmol of one of the primers (Perkin-Elmer Nederland BV, Gouda, The Netherlands) 1254 (5′-CCGCAGCCAA-3′), 1281 (5′-AACGCGCAAC-3′), 1283 (5′-GCGATCCCCA-3′), and 1247 (5′-AAGAGCCCGT-3′) (1) were used in a PCR as previously described (32). The PCR fragments were analyzed by horizontal agarose (1%) gel electrophoresis as described before (32).

Computer-assisted analysis of RAPD patterns.

The RAPD patterns were visualized by UV illumination and imaged with a video camera. Cluster analysis was performed with Gelcompar software version 3.1 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). Patterns were normalized to RAPD patterns from Neisseria meningitidis ET present every five lanes on each gel. The patterns generated by each of the four RAPD primers were combined and compared by using unweighted pair group method for arithmetic averages (UPGMA) clustering with Dice coefficient applied.

Fluorescence-based DNA sequencing and analysis.

PCR products obtained with primer cagA5 (5′-GGCAATGGTGGTCCTGGAGCTAGGC-3′; positions 1495 to 1519, according to Covacci et al. [5]) and primer cagA2 (5′-GGAAATCTTTAATCTCAGTTCGG-3′; positions 1819 to 1797) (21) were subjected to a PCR-based sequencing in both directions by reaction with fluorescent dye-labeled dideoxynucleotide terminators, using Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) and primers cagA5 and cagA2 according to the instructions supplied by Applied Biosystems Incorporated (Foster City, Calif.).

From glmM, an identical region of the gene was sequenced as described by Kansau et al. (14). Primer HP1 (5′-GGATAAGCTTTTAGGGGTGTTAGGGG-3′); positions 1289 to 1314, according to Labigne et al. [18]) and primer HP2 (5′-GCTTACTTTCTAACACTAACGC-3′); positions 1584 to 1563, according to Labigne et al. [18]) were used to amplify a 295-bp fragment. This fragment was sequenced in both directions as described for cagA sequencing. Sequences were analyzed on an automatic sequencer (model 373; Applied Biosystems). From the cagA sequence, the first 42 bp and the last 39 bp, containing the primer sequences, were discarded. From the glmM sequence, the first 37 and last 19 bp were discarded.

glmM and cagA sequences were compared by using a computer program included in the 1993 MEGA (17) program. Trees describing the phylogenetic history of the H. pylori strains in this study were reconstructed by using the neighbor-joining algorithm of Saitou and Nei (27), with the Kimura two-parameter distance measures (15) as implemented in the MEGA program. Bootstrap resampling analyses (1,000 replicates) were performed to assign confidence limits to the estimated phylogenies. The proportions of synonymous substitutions (or silent mutations, i.e., without amino acid substitutions; dS) and nonsynonymous substitutions (mutations resulting in amino acid substitutions; dN) at synonymous and nonsynonymous sites, respectively, were calculated by the method of Nei and Gojobori (20), with the application of the correction of Jukes and Cantor (13) for multiple hits at individual sites as implemented in the MEGA program. The computer program Maximum Chi-Squared for Macintosh (version 1.0, 1995; developed by Nick Ross, Molecular Microbiology Group, School of Biological Sciences, University of Sussex, Brighton, England) from the original implementation of the maximum chi-squared method by Maynard Smith (19) was used to analyze possible recombination events in the sequenced part of cagA.

RESULTS

RAPD-PCR of H. pylori isolates from Dutch and Chinese patients.

Assessment by RAPD-PCR of chromosomal DNA of 22 cagA-positive H. pylori isolates, 12 from 12 Dutch patients and 10 from 10 Chinese patients, showed that each isolate had a unique RAPD pattern. The initial isolate 79A and isolate 79J cultured from sequential biopsy specimens taken from the same patient were identical. Likewise, the initial isolate 161A was identical to isolate 161L. Clustering analysis did not reveal any clusters of isolates on the basis of either clinical manifestations or origin of geographic area.

Comparison of cagA sequences of H. pylori isolates from Dutch and Chinese patients.

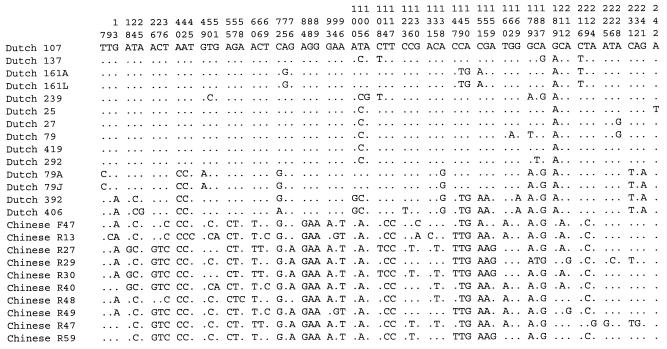

Comparison of a 243-bp part of the cagA sequence region between nucleotides 1537 and 1780 (notation according to Covacci et al. [5]) from the 24 clinical H. pylori isolates showed 21 alleles, with mutations at 67 possible positions (Fig. 1). Both sequentially recovered H. pylori isolates from two Dutch patients (strains 161A and 161L; strains 79A and 79J) and two H. pylori isolates from two Chinese patients (strain R27 and R30) had identical cagA sequences. In Fig. 2, the polymorphic site in the cagA region between nucleotides 1537 and 1780 of cagA is shown. The total number of 67 nucleotide substitutions resulted in 22 possible amino acid substitutions. The dS and dN values were similar in the 12 H. pylori isolates from 12 Dutch patients and the group of H. pylori isolates from 10 Chinese patients (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Polymorphic sites in cagA (positions 1537 to 1780, according to Covacci et al. [5]) of H. pylori. Each site at which the nucleotide sequence of one or more cagA sequences was different from that of H. pylori strain Dutch 107 is shown. The numbers (in vertical format) above the sequences identify positions of the sites; 1 corresponds to position 1537.

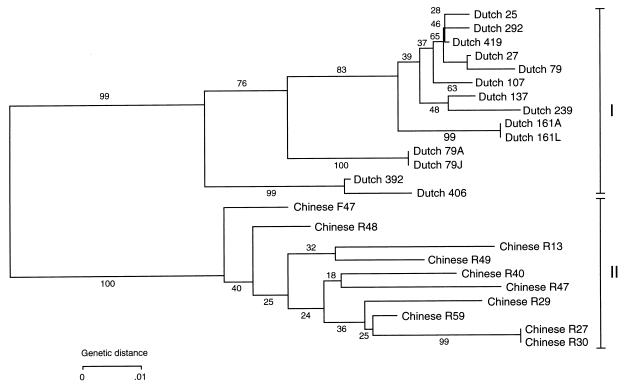

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of 25 cagA sequences of 14 H. pylori isolates from 12 Dutch patients and 10 H. pylori isolates from 10 Chinese patients. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method with the Kimura two-parameter distance measures (15). The designation of each isolate is shown at the right of each branch of the tree.

TABLE 1.

Proportion (Jukes-Cantor corrected) of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions per site among the 243-nucleotide sequenced part of cagA between nucleotides 1573 and 1780 (notation according to Covacci et al. [5]) of 25 H. pylori isolates

| Source of isolates | No. of isolates | Proportion of substitutions (mean ± SE)

|

dS/dN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dS | dN | |||

| Dutch patients | 12a | 0.102 ± 0.071 | 0.027 ± 0.021 | 3.8 |

| Chinese patients | 10 | 0.140 ± 0.053 | 0.025 ± 0.010 | 5.6 |

The cagA sequences of H. pylori isolate 79J (identical to 79A but isolated from the same patient 6 years later) and 161L (identical to 161A but isolated from the same patient 4 years later) were not taken into account.

Clustering analysis revealed two main groups comprising the H. pylori strains from all Dutch patients (group I) and the H. pylori strains from all Chinese patients (group II) (Fig. 2). Bootstrap analysis (1,000 replicates) demonstrated a high confidence (that is, identical branch points occurred in all bootstrap replicates) of the difference between the two main groups comprising the H. pylori isolates from Dutch and Chinese patients. The cagA sequence of group I strains (excluding strains 79J and 161L) showed 3.9% average divergence at the nucleotide level and 6.2% average divergence at the amino acid level. The levels of average divergence of the cagA sequence among the group II strains were similar, 4.8 and 5.8% at the nucleotide and amino acid levels, respectively. Evidently, the difference in the cagA sequence was more extensive (two to three times larger) when the strains of the two groups were compared with each other (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Sequence diversity among a part of 243 nucleotides of the cagA region between 1573 and 1780 (notation according to Covacci et al. [5]) of H. pylori isolates from 12 Dutch and 10 Chinese patients

| Source of isolates | No. of isolates | % Differences (mean ± SD)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | ||

| Group I | 12b | 3.9 ± 2.5 | 6.2 ± 4.7 |

| Group II | 10 | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 2.2 |

| Groups I and II | 22 | 13.3 ± 1.4 | 17.9 ± 2.1 |

Group I, Dutch patients; group II, Chinese patients.

The cagA sequences of H. pylori isolate 79J (identical to 79A but isolated from the same patient 6 years later) and 161L (identical to 161A but isolated from the same patient 4 years later) were not taken into account.

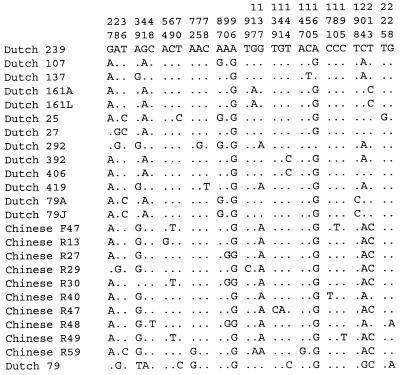

Comparison of glmM sequences of H. pylori isolates from Dutch and Chinese patients.

To compare sequence heterogeneity of cagA, located on the PAI, with that of a gene outside the PAI, part of glmM (formerly called ureC [18]) was sequenced. Of the 24 H. pylori isolates, the same 240-bp part of glmM was sequenced as described by Kansau et al. (14). Twenty-two alleles with mutations at 32 possible positions were found (Fig. 3). The two sequentially recovered H. pylori isolates from each of the two Dutch patients (strains 161A and 161L; strains 79A and 79J) were identical. The total number of 32 nucleotide substitutions resulted in only 3 possible amino acid substitutions. The dS/dN ratio (dS/dN = 0.1103/0.0068 = 16.2) was much higher in glmM than in cagA. In contrast to the cagA sequence, clustering analysis of glmM did not result in any robust cluster formation.

FIG. 3.

Polymorphic sites in glmM (positions 1326 to 1569, according to Labigne et al. [18]) of H. pylori. Each site at which the nucleotide sequence of one or more glmM sequences was different from that of H. pylori isolate Dutch 239 is shown. The numbers (in vertical format) above the sequences identify positions of the sites; 1 corresponds to position 1326.

DISCUSSION

Data obtained from a recent report suggested that H. pylori genotypes circulating in China are distinct from those in Western Europe due to allelic variation in cagA (21). The aim of our study was to provide evidence that Chinese patients and Dutch patients are colonized with distinct cagA-positive H. pylori strains.

RAPD-PCR analysis of 14 H. pylori isolates from 12 Dutch patients and 10 from 10 Chinese patients demonstrated a high level of genetic diversity among the 24 strains. In previous studies using this technique, it was shown that H. pylori comprises a genetically highly heterogeneous group, with patient-to-patient variation (1). In addition, patients can harbor a heterogeneous H. pylori population (12, 31, 33, 37). On the basis of the RAPD-PCR patterns, the 24 H. pylori strains could be clustered according to neither the various clinical entities nor the geographic origin of the patient. Results obtained with multilocus enzyme electrophoresis suggested clustering of 23 H. pylori isolates into four clusters (11). The authors concluded that the genetic diversity in H. pylori may be sufficient to classify H. pylori strains into four or more cryptic species. However, the similarity of strains within a cluster was rather low and varied between 30 and 70%. In addition, a similar analysis revealed that no clustering among 74 H. pylori isolates occurred, and a very high mean genetic diversity was found (10).

The phylogenetic tree based on the cagA sequences showed a robust division between H. pylori isolates from Dutch patients (group I) and H. pylori isolates from Chinese patients (group II). In addition, the cagA sequences previously published by Covacci et al. (5) and Tummuru et al. (31) fit into the branch comprising the Dutch H. pylori strains, while the cagA sequence of the H. pylori isolate from a Japanese patient fit into the branch comprising the Chinese H. pylori strains, without altering the robust division between the Western and Chinese H. pylori isolates in the tree (data not shown). The percentage difference between cagA of groups I and II is larger than the differences between cagA of H. pylori isolates within its appropriate group (Table 2). In contrast both phylogenetic trees based on RAPD patterns and on glmM sequences showed the overall genetic variation without any robust clustering. Therefore, we assume that in the past, the PAI that has been integrated into the genome of the ancestor of H. pylori now circulating in China contained a different cagA than the PAI that has been integrated into the genome of the ancestor of H. pylori now circulating in The Netherlands. Alternatively, the ancestors of H. pylori in Western countries and in China diverted soon after their development, and cagA differences may have evolved due to genetic differences of the hosts or other environmental conditions. The dS/dN ratio was much lower in cagA (dS/dN = 4) than in glmM (dS/dN = 16) and lower than the average dS/dN value of 24 for bacterial genes (28). The high number of nonsynonymous substitutions in cagA was not limited to the sequenced region. In an adjacent part, between positions 1249 and 1519 (according to the notation of Covacci et al. [5]), similar amounts of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions were observed (not shown). Such a bias toward nonsynonymous substitutions is also reported for the genes coding for the P2 porin of Haemophilus influenzae (8) and the P1 porin of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (29). It is known that both the P2 protein of H. influenzae and the P1 protein of N. gonorrhoeae elicit a strong immune response in the host during the course of infection. In general, all patients infected with cagA-positive H. pylori show a strong immune response against the CagA protein (7, 38, 23). Therefore, it may be that upon infection, selection by the host immune response for nonsynonymous substitutions (amino acid substitutions) in cagA, and hence antigenic variation of CagA, had occurred. However, the cagA sequences of the H. pylori isolates 79A and 79J, cultured with a time interval of 6 years from the same patient, were identical. The same holds true for the cagA sequences of H. pylori isolates 161A and 161L, cultured with a time interval of 4 years from another Dutch patient. Thus, in these two patients cagA was invariable during 4 to 6 years, showing no evidence for antigenic variation during this time interval. Most likely, recovery of H. pylori from both patients was done a long time after H. pylori acquisition, and the host-pathogen interaction may have reached its balance. We hypothesize that most cagA variation of H. pylori occurs during the acute phase of infection, in which the incoming H. pylori has to adapt to harsh conditions present in the human stomach, resulting in new H. pylori variants. These so-called sequential bottlenecks might also give an explanation of the finding that patients can carry heterogeneous populations of H. pylori in one patient (12, 32, 34, 37). It may be that the different variants grow out at different sites in the stomach. Recombination within the chromosome of the bacterium and/or between different variants may further increase heterogeneity (2, 10). However, evidence for recombination within the cagA sequences was not found in the set of 25 H. pylori strains analyzed by a computer program using the algorithm of Maynard Smith (19). The many nonsynonymous mutations could also imply that CagA of H. pylori from patients from different geographic areas are antigenically different, especially of H. pylori isolates from Dutch and Chinese patients.

In summary, we conclude that two distinct cagA-positive H. pylori populations are circulating in China and The Netherlands. Most likely, the PAI that has been integrated into the chromosome of the ancestor of the H. pylori now circulating in China contained a different cagA than the PAI that has been integrated into the chromosome of the ancestor of the H. pylori now circulating in The Netherlands.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Dutch Ministry of Education and Science, the Royal Dutch Academy of Science, and the Chinese Ministry of Public Health (1994).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akopyants N, Bukanov N O, Westblom T U, Kresovich S, Berg D E. DNA diversity among clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori detected by PCR-based RAPD fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5137–5142. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.19.5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atherton J C, Cao P, Peek R M, Jr, Tummuru M K, Blaser M J, Cover T L. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17771–17777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaser M J, Perez-Perez G I, Kleanthous H. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2111–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree J E, Ghiara P, Borodovsky M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14648–14653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Covacci A, Censini S, Burroni M, Macchia G, Massone A, Papini E, Xiang Z, Figura N, Rappuoli R. Molecular characterization of the 128 kDa immunodominant antigen of Helicobacter pylori associated with cytotoxicity and duodenal ulcer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5791–5795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Covacci A, Falkow S, Berg D E, Rappuoli R. Did the inheritance of a pathogenicity island modify the virulence of Helicobacter pylori? Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:205–209. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crabtree J E, Taylor J, Wyatt J I, Heatley R V, Shallcross T M, Tompkins D S, Rathbone B J. Mucosal IgA recognition of Helicobacter pylori 120 kDa protein, peptic ulceration, and gastric pathology. Lancet. 1993;338:332–335. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90477-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duim B, van Alphen L, Eijk P, Jansen H M, Dankert J. Antigenic drift of non-encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae major outer membrane protein P2 in patients with chronic bronchitis is caused by point mutations. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:1181–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foreman D Eurogast Study Group. An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Lancet. 1993;341:359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Go M E, Kapur V, Graham D Y, Musser J M. Population genetic analysis of Helicobacter pylori by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis: extensive allelic diversity and recombinational population structure. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3934–3938. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3934-3938.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hazell S L, Andrews R H, Mitchell H M, Daskalopoulos G. Genetic relationship among isolates of Helicobacter pylori: evidence for the existence of a Helicobacter pylori species-complex. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorgensen M, Daskalopoulos G, Warburton V, Mitchell H M, Hazell S L. Multiple strain colonisation and metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori infected patients; identification from sequential and multiple biopsy specimens. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:631–635. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kansau I, Raymanond J, Bingen E. Genotyping of Helicobacter pylori isolates by sequencing of PCR products and comparison with the RAPD technique. Res Microbiol. 1996;147:661–669. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)84023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuipers E J, Perez-Perez G I, Meeuwissen S G, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori and atrophic gastritis: importance of the cagA status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1777–1780. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA, Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis, v 1.01. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University; 1993. . (Distributed by the authors.) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labigne A F, Cussac V, Courcoux P. Shuttle cloning and nucleotide sequences of Helicobacter pylori genes responsible for urease activity. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1920–1931. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.1920-1931.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maynard Smith J. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J Mol Evol. 1992;34:126–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00182389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3:290–300. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan Z-J, van der Hulst R W M, Feller M, Xiao S-D, Tytgat G N J, Dankert J, van der Ende A. Equally high prevalence of infection with cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori in Chinese patients with peptic ulcer disease and chronic gastritis-associated dyspepsia. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1344–1347. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1344-1347.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan Z-J, Xiao S D, Jiang S J, Zhang Z H, Fang G F, Zhang S S, Wang W Q. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in urban and rural areas of Shanghai. Chin J Digest. 1992;12:198–200. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan Z J, Xiao S D. Analysis of immunoglobulin G antibodies to Helicobacter pylori and its clinical application. Chin J Gastroenterol. 1996;1:23–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L, Gelb A B, Warnke R A, Jellum E, Orentreich N, Vogelman J H, Friedman G D. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1267–1271. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405053301803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsonnet J, Friedman G D, Orentreich N, Vogelman H. Risk for gastric cancer in people with cagA positive or cagA negative Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1997;40:297–301. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rauws E A, Tytgat G N J. Cure of duodenal ulcer associated with eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1990;335:1233–1235. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91301-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbour-joining method: a new method for reconstruction phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharp P M. Determinants of DNA sequence divergence between Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: codon usage, map position, and concerted evolution. J Mol Evol. 1991;33:23–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02100192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith N H, Smith J M, Spratt B G. Sequence evolution of the porB gene of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis: evidence for positive Darwinian selection. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:363–370. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomb J-F, White O, Kervage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, Mckenney K, Fitzegerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Hickey E K, Berg D E, Gocayne J D, Utterback T R, Peterson J D, Kelley J M, Cotton M D, Weidman J M, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes W S, Borodovsky M, Karp P D, Smith H O, Fraser C M, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tummuru M K R, Cover T L, Blaser M J. Cloning and expression of a high-molecular-mass major antigen of Helicobacter pylori: evidence of linkage to cytotoxin production. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1799–1809. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1799-1809.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Ende A, Rauws E, Feller M, Mulder C, Tytgat G N J, Dankert J. Heterogeneity of Helicobacter pylori isolates from members of a family with a history of peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:638–647. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8780568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Ende, A., R. W. M. van der Hulst, J. Dankert, and G. N. J. Tytgat. 1997. Reinfection versus recrudescence in Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 11(Suppl. 1):55–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.van der Hulst R W M, Köycü B, Rauws E A J, Keller J J, ten Kate F J W, Dankert J, Tytgat G N J, van der Ende A. H. pylori reinfection is virtually absent after successful eradication analyzed by DNA-fingerprinting. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:196–200. doi: 10.1086/514023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Hulst, R. W. M., and G. N. J. Tytgat. 1996. H. pylori and peptic ulcer disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 31(Suppl. 220):10–18. [PubMed]

- 36.van der Hulst R W M, van der Ende A, Dekker F, Keller J, Kruizinga S, ten Kate F J W, Dankert J, Tytgat G N J. The influence of H. pylori eradication on gastritis, intestinal metaplasia and atrophy in relation to cagA: a prospective one year follow up study. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weel J, van der Hulst R W M, Gerrits Y, Tytgat G N J, van der Ende A, Dankert J. Heterogeneity in susceptibility for metronidazole among Helicobacter pylori from patients with gastritis or peptic ulcer disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2158–2162. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2158-2162.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weel J F L, van der Hulst R W M, Gerrits Y, Roorda P, Feller M, Dankert J, Tytgat G N J, van der Ende A. The interrelation between cytotoxin associated gene A, vacuolating cytotoxin and Helicobacter pylori related diseases. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1171–1175. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.5.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao S D, Pan Z J, Zhang Z H, Jiang S J. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of immunoglobulin G antibody against Helicobacter pylori. Chin Med J. 1991;104:904–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]