Abstract

Objectives

Deslorelin 4.7 mg and melatonin 18 mg subcutaneous implants were studied in purebred male and female cats, via questionnaires sent to French cat breeders, to assess breed, age, duration of the contraceptive effect, fertility after use, changes in behaviour and side effects.

Methods

Reproductive data were collected in 57 tom cats and 41 queens implanted with deslorelin 4.7 mg, and 42 queens implanted with melatonin 18 mg, for a total of 140 purebred cats, from 38 different catteries, representing 18 breeds.

Results

Using deslorelin (Suprelorin 4.7 mg; Virbac), sexual behaviour in males was inhibited for a mean ± SD of 13.4 ± 3.2 (range 8–21) months in 37/57 cats. Of these, 24/37 mated successfully and produced litters at a mean of 15.5 ± 3.6 (range 9–20) months. Inhibition lasted 11 ± 1.1 (range 9–12; n = 6), 13.2 ± 2.4 (range 12–18; n = 6) and 15 ± 3.5 (range 9–18; n = 6) months in Norwegian Forest Cat, Singapura and Ragdoll males, respectively. In 26/41 females implanted with deslorelin 4.7 mg, oestrus was inhibited for a mean of 16.0 ± 5.7 (8–38) months; 12/26 went on to produce a litter. Of the side effects specific to females: two presented persistent oestrus, leading to the removal of the implant; two developed lactation; one had fibroadenomatosis; and one was sterilised owing to cystic endometrial hyperplasia. Using melatonin (Melovine 18 mg; Ceva), 33/42 females had oestrus inhibited for a mean of 86 ± 50 (range 21–277) days after implantation with a peak return to oestrus in March, and 12/33 had a subsequent litter. No side effects were reported.

Conclusions and relevance

This study is the first to collect a large amount of field data, in 140 purebred male and female cats where a deslorelin 4.7 mg or a melatonin 18 mg implant was used. These field results may allow for more accurate clinical advice and open up new avenues of research.

Keywords: Implant, contraception, deslorelin, melatonin, fertility, breed, seasonal, seasonality, oestrus, oestrous suppression

Introduction

Medical contraception in cats is a subject of great interest, not just regarding the control of overpopulation.1,2 There is increasing clinical demand, not only from breeders for a safe temporary contraceptive solution and easier breeding management to avoid several queens being bred at the same time, but also from private owners who are increasingly rejecting surgical neutering of their cats. In France, the only available labelled treatment for medical contraception in cats is progestins in females. Evidence suggests that progestin-based treatments may increase the risk of occurrence of mammary tumours,3–9 fibroadenomatosis,10,11 cystic endometrial hyperplasia,12–14 pyometra 15 and diabetes mellitus.16–20 In recent literature, other off-label contraceptive options have been tested, such as subcutaneous (SC) implants containing 4.7 mg gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) superagonist deslorelin (Suprelorin 4.7 mg; Virbac),21–40 and 18 mg melatonin (Melovine; Ceva).41–45

Deslorelin acetate is a decapeptide that differs from GnRH by only two amino acids. It acts as an analogue of GnRH, with a higher potency at GnRH receptors.46,47 After an initial ‘flare-up’ effect, where sexual activity may be increased, a period of full sexual inhibition is observed. 48 In males, the inhibition of steroidogenesis after implantation with deslorelin 4.7 mg was studied in seven domestic shorthair (DSH) cats, for a mean ± SD duration of 19.7 ± 3 months (range 15–25 months), based on basal testosterone values. 27 Full recovery of normal mating behaviour and libido was observed at 18.2 months and normal testicular size was recovered at 20.8 months. 27 Another study described sexual inhibition for a duration of 22.7 ± 5.8 months (range 16–30 months) in nine privately owned cats 32 of three different breeds (seven DSH cats, two Van cats and one Siamese), based on the alteration of urine odour, urine marking, libido and aggressive behaviour towards the owners or other cats. In queens, deslorelin 4.7 mg was described to suppress oestrous behaviour for 22.7 ± 2.1 months (range 16–37 months) in 19 European Shorthair cats. 49

Melatonin is an essential hormone regulating seasonality; it is secreted by the pineal gland during the night. 50 In the cat, being considered a long day breeder, melatonin acts as an inhibitor of the hypothalamo–pituitary axis,44,45,51 although some cats express oestrous behaviour even in winter in temperate climates.52,53 Off-label 18 mg SC implants have been shown to suppress oestrous behaviour for a shorter period of time than deslorelin implants, with variations depending on the time of implantation. Females implanted during seasonal anoestrus, interoestrus or oestrus were inhibited, on average, for 5 months (n = 6), 41 113 ± 6.2 days (n = 9) 42 and 61 ± 6.9 days, 42 respectively. Independently of the presence or absence of ovulation, the mean duration of oestrous suppression was 90 ± 60 days (range 56–156 days; n = 19). 44 In male cats, it has been shown to temporarily decrease semen concentration, although not induction of azoospermia. 43

This study aimed to compile data collected from cat breeders who have been using deslorelin or melatonin SC implants off-label, as a reversible contraceptive method in their cats.

Materials and methods

Animals

Two hundred and twenty cat breeders who were in the database of the Centre d’Étude en Reproduction des Carnivores (CERCA, École Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort) were asked to give feedback on their use of contraceptive implants in breeding cats by completing a questionnaire (see the supplementary material). No ethical committee approval was needed, as the study was based on the free will of owners to provide information on implant use in their cattery. Data were collected via separate tables on deslorelin 4.7 mg in males and females, and on melatonin 18 mg in females. Breed, age, duration of contraceptive effect, fertility before and after use, changes in behaviour and side effects were evaluated. Owing to the presence of deslorelin 9.4 mg on the market, the type of implant and peculiarities during administration were specifically recorded. The site of implantation and eventual sedation before administration were not specifically recorded, as information on this was not asked for in the questionnaire. In France, only veterinarians are allowed to buy these implants and to perform SC implantations. Therefore, all cats in this study were implanted by veterinarians. Whenever information on animals was missing or was unclear, the owners were contacted by telephone to complete the data.

Results

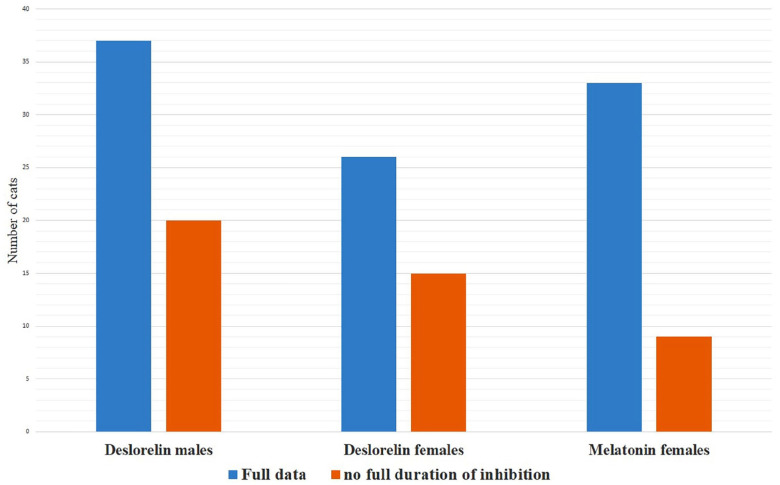

Thirty-eight of 220 (17%) breeders answered the questionnaire. Data were reported for 57 males (belonging to 32 different breeders, representing 15 breeds) and 41 females (belonging to 22 different breeders, representing 15 breeds), using deslorelin 4.7 mg. Melatonin 18 mg was used in 42 females belonging to 19 breeders, representing 11 breeds (Figure 1). Overall, 18 different breeds were represented. All cats were implanted after puberty and were living in multi-cat households. All breeders were living in France, except one who was living in Switzerland. Time of implantation occurred between April 2012 and March 2018.

Figure 1.

Total number of males and females implanted with deslorelin 4.7 mg and melatonin 18 mg with full data on the duration of inhibition period and total number of animals without full duration of inhibition (due to secondary effects, removal of the implant, specific uses or implant still inhibiting the animal at the time of questionnaire retrieval)

Deslorelin 4.7 mg in males

The duration of male sexual behaviour inhibition (ie, urine odour, urinary marking and attraction to females) was recorded in 37/57 (65%) cats (Figure 1) for a mean duration of 13.4 ± 3.2 (range 8–21 months). The end of the initial ‘flare-up’ effect was recorded at a mean of 1.7 ± 1 months (range 0.3–4 months) in 22 cats. British Shorthairs (n = 3), Ragdolls (n = 6) and Siberians (n = 3) showed the longest mean inhibition of sexual behaviour (16.7, 15 and 14.3 months, respectively). Singapuras (n = 6), a lightweight breed, had a mean inhibition period of 13.2 months; Maine Coons (n = 3) and Norwegian Forest Cats (n = 6) had the lowest mean duration (11.7 and 11 months, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean duration of male sexual behaviour inhibition and first fertile mating after implantation with deslorelin 4.7 mg, classified by breed, from the longest to the shortest duration

| Duration of inhibition of sexual behaviour, urinary marking, odour and aggression with deslorelin 4.7 mg |

First fertile mating after implantation with deslorelin 4.7 mg |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Breed | Efficacy (months) | Breed | Efficacy (months) |

| British Shorthair | 16.7 ± 4.5 (12–21) (n = 3) | British Shorthair | 19.5 (16–23) (n = 2) |

| Ragdoll | 15 ± 3.5 (9–18) (n = 6) | Somali and Abyssinian | 19.3 ± 1.1 (18–20) (n = 3) |

| Siberian | 14.3 ± 4.7 (9–18) (n = 3) | Ragdoll | 15.8 ± 3.1 (10–18) (n = 6) |

| Somali and Abyssinian | 14.2 ± 4.5 (8–18) (n = 5) | Siberian | 15.3 ± 5.5 (9–19) (n = 3) |

| Siamese | 14 (14–14) (n = 2) | Norwegian Forest Cat | 14.4 ± 2.2 (13–18) (n = 5) |

| Singapura | 13.2 ± 2.4 (12–18) (n = 6) | Sphynx | 14 (n = 1) |

| Sphynx | 12 (n = 1) | Maine Coon | 12.3 ± 1.5 (11–14) (n = 3) |

| Maine Coon | 11.7 ± 1.1 (11–13) (n = 3) | Russian Blue | 11 (n = 1) |

| Norwegian Forest Cat | 11 ± 1.3 (9–12) (n = 6) | Siamese | – |

| Russian Blue | 11 (n = 1) | Singapura | – |

| Total | 13.4 ± 3.2 (8–21) (n = 37) | Total | 15.5 ± 3.5 (9–20) (n = 24) |

Data are mean ± SD (range), but with SD calculated only when n (number of cats) ⩾ 3

Of the 37/57 cats with full duration of sexual behaviour inhibition, 24 were subsequently presented to females and all 24 (100%) mated successfully at a mean of 15.5 ± 3.5 months (range 9–20 months) after implantation, leading to litters of 2–7 kittens. First fertile mating after implantation was longer in British Shorthairs (19.5 months [range 16–23 months]; n = 2), Abyssinians and Somalis (19.3 ± 1.1 months [range 18–20 months]; n = 3), and Ragdolls (15.8 ± 3.1 months [range 10–18 months]; n = 6) vs a shorter time in Norwegian Forest Cats (14.4 ± 2.2 months [range 13–18 months]; n = 5) or Maine Coons (12.3 ± 1.5 months [range 11–14 months]; n = 3) (Table 1). Of the males that mated successfully, 4/24 (17%) started to mate after recovery of apparent normal sexual behaviour but seemed to be infertile for 1–2 months before producing a normal litter. Of the 37 recorded males, 13 (35%) were re-implanted up to three consecutive times. Nine of the 13 tom cats were allowed to mate between two implantations and all the matings resulted in pregnancy with the number of kittens, when recorded, being between one and four.

Data on the month of implantation and the month of the end of inhibition were recorded. Peak implantation periods were observed between June and September, and in January. Return to sexual behaviour was detected throughout the year, except in April, with peaks in January, June, July and August. Mean age at implantation was 27.4 ± 22.5 months (range 5–99 months), with high variations: the shortest inhibition periods post-implantation – between 8 and 9 months – were observed in a Norwegian Forest Cat as young as 9 months old, as well as a 99-month-old Somali cat. The longest durations – between 18 and 21 months – were observed in cats aged between 11 and 96 months.

Some side effects were recorded, with weight gain being the main one (n = 13/57). This side effect was sometimes sought by breeders and was once reported to be associated with increased haircoat quality. One breeder reported a completely reversible weight gain after the end of action of the implant, without changing any food habits at any time. Soon after implantation, four cats successfully mated 2, 2.5, 3 and 3.5 months (81 days maximum) post-implantation, resulting in unwanted pregnancies. Two other cats mated at 3 and 5 months after implantation, but no litter was produced. Finally, one Maine Coon with reduced libido, aggression, marking behaviour and odorous urine still mated females in oestrus without any pregnancy throughout the whole period of implantation.

Of the 20/57 (35%) remaining males without full data on the duration of sexual behaviour inhibition, 11/20 were still inhibited at the time of data collection with a mean duration of inhibition of 8.5 ± 6.2 months (range 1–20 months), with three cats that were still inhibited long after implantation (one British Shorthair, one Somali and one Abyssinian male were still inhibited 20, 15 and 13 months, respectively, after implantation at the time of data collection). Four of the 20 cats had been implanted with ‘cut-in-half’ implants, as previously reported in dogs, 54 and were excluded. Inhibition of male sexual behaviour in these four cats was highly variable: 14, 16 and 24 months for a Ragdoll and two Birmans, respectively; one Sphynx was still inhibited 3 months after implantation at the time of data collection. Two of 20 tom cats (one Oriental and one Siberian) had their implant removed at 4 months, as previously suggested; 23 sexual behaviour was recovered 5 months and 23 months after implantation, respectively. One of the 20 cats (an Oriental) had the implant removed at 5 months and was inhibited for 6 months after implantation. One of the 20 cats (a Somali) was castrated surgically 3 months after implantation, and 1/20 cats (a Somali) died as a result of urethral obstructive disease, while in the 15th month of implantation, before it could recover sexual behaviour.

Deslorelin 4.7 mg in females

The duration of oestrus suppression was recorded in 26/41 (63%) queens (Figure 1), with a mean duration of suppression of oestrus after implantation of 16.0 ± 5.7 months (range 8–38 months). Twelve breeds were represented in this group (Table 2). Of the 26 females with a fully recorded inhibition period, 12/26 produced litters at the end of efficacy of the implant, at a mean of 18.7 ± 5.8 months (12–27 months), with 3–7 kittens per litter. From this group, caesarean section was performed in one Singapura; the kittens did not survive and the reason for the surgery was unknown. Mean age at implantation was 28 ± 20 months (range 6–108 months). The longest period of inhibition (38 months) was observed in a 19-month-old Persian female. This female lived in a breeding facility with several other males and females. The shortest inhibition period of 8 months was found in a 14-month-old Persian and in an 18-month-old British Shorthair.

Table 2.

Mean duration of inhibition of oestrus after implantation with deslorelin 4.7 mg, classified by breed

| Breed | Duration of oestrus suppression in months |

|---|---|

| Egyptian Mau | 19 (13–25) (n = 2) |

| Persian | 17.8 ± 9.5 (8–38) (n = 7) |

| Birman | 17 (n = 1) |

| Bengal | 17 (n = 1) |

| Ragdoll | 16 (n = 1) |

| Abyssinian | 16 (n = 2) |

| Norwegian Forest Cat | 15 ± 3.7 (12–20) (n = 6) |

| Sphynx | 15 (12–18) (n = 2) |

| Balinais | 15 (n = 1) |

| Singapura | 15 (n = 1) |

| Oriental | 14 (n = 1) |

| British Shorthair | 8 (n = 1) |

| Total | 16.0 ± 5.7 (range 8–38) (n = 26) |

Data are mean ± SD (range), but with SD calculated only when n (number of cats) ⩾ 3

The main reported side effect was reversible weight gain. Two cats had their implants removed for persistent oestrus and one owing to an apparent fibroadenomatosis. One Maine Coon and one Persian developed lactation, 1 and 2 months after implantation, respectively.

Of the 15/41 (37%) remaining females without full data on the duration of oestrus suppression, two females were still inhibited at the time of data collection, at their 12th (a Sphynx) and 15th month (a Persian) of implantation. Three of the 15 females had their implant removed at 4 months, with an oestrus suppression of 8 months (a Norwegian Forest Cat), 10 months (a Norwegian Forest Cat) and 14 months (a Maine Coon) from the time of implantation. Two of the 15 females (both Maine Coons) had their implant removed 5 months after implantation and were both inhibited for 8 months. One of the 15 females (a Maine Coon) had the implant removed 6 months after implantation and was still inhibited 12 months after implantation at the time of data collection. Two of the 15 females (a Russian Blue and a European Shorthair) were in permanent oestrus after implantation, leading to the removal of the implant; 2/15 females (both Sphynxes) were implanted with ‘cut-in-half’ implants, 54 with a duration of 2 months’ oestrus suppression for one and with the other still inhibited at the time of data collection, 3 months after implantation. One of the 15 females (a Norwegian Forest Cat) was sterilised owing to the development of cystic endometrial hyperplasia 6 months after implantation. One of the 15 females (a Maine Coon) had the implant removed after an excessive development of a mammary gland, which may be attributed to fibroadenomatosis. One of the 15 females (a Somali) died for unknown reasons 6 months after implantation.

Melatonin 18 mg in females

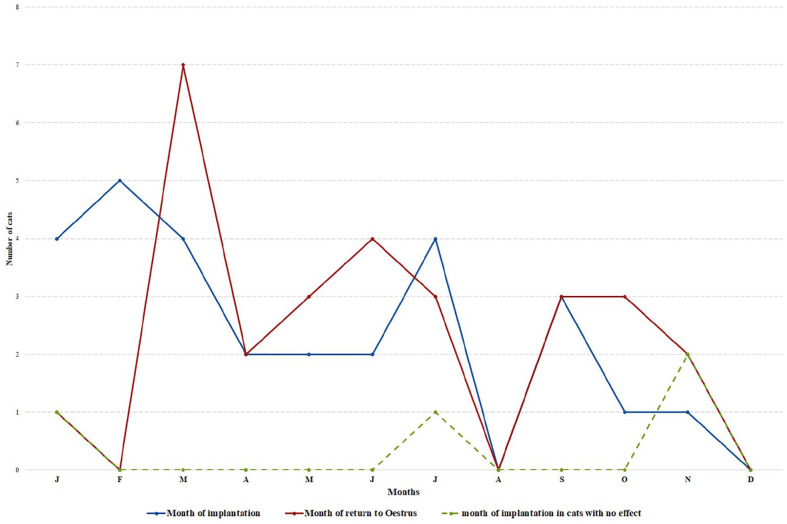

The melatonin 18 mg implant had a mean efficacy of preventing oestrus for 86.4 ± 50.3 days (range 21–277 days) in 33/42 (79%) cats (Table 3), in 11 different breeds. Of the 33/42 fully recorded inhibited females, 12 were allowed to mate after the end of action of the implant and all had a litter of 2–6 kittens. No side effects were reported. All were implanted during interoestrus, except two, which were in permanent oestrus. Data on the month of implantation and month of sexual recovery was recorded in 28 females. Females were implanted throughout the year, although only five cats were implanted between the months of August to December. A peak return to oestrus was observed in March, with only three cats returning into oestrus within the period of November to February (Figure 2). Mean age at implantation was 23.2 ± 16 months (range 6–71 months).

Table 3.

Female oestrus intervals, depending on the stage of the cycle at the time of implantation with 18 mg melatonin

| Reference | During oestrus | During interoestrus | During anoestrus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gulyuz et al 41 (n = 6) | – | – | December–April |

| Gimenez et al 42 (n = 9) | 61 ± 6.9 days | 113 ± 6.2 days* | – |

| Faya et al 53 (n = 17) | – | 63.8 ± 5.4 days* | – |

| Schäfer-Somi 44 (n = 19) | – | 90 days (range 56–156 days, n = 13/19)

†

6 oestruses 1–10 days after implantation (n = 6/19) |

– |

| Present study (n = 42) | – | 86.4 ± 50.3 days (range 21–277 days, n = 33/42)

†

7 oestruses 1–10 days after implantation (n = 7/42) |

– |

Females that ovulated were removed from the study

No determination of ovulation was performed

Figure 2.

Number of implanted queens with melatonin 18 mg, depending on the month of implantation (blue), and the month of return to oestrus (red). The month of implantation in cats with no reported effect is also shown (green)

Of the 9/42 (21%) remaining females without full data on the duration of oestrus suppression, seven cats exhibited an oestrous behaviour within 10 days after implantation. Data on the month of implantation was recorded in four (Figure 2). Two of the nine remaining females were still inhibited 1–2 weeks after implantation at the time of data collection.

Discussion

This is the first study to document the use of deslorelin and melatonin implants in different purebred cats in field conditions. Although the number of answers from the 220 breeders in the database was only 38 (17%), the response rate was similar to other studies that used a convenience sampling technique. 52 It is likely that some breeders did not have any experience with feline contraceptive implants, thus reducing the response rate: some breeders may not be aware of the possibility of using contraceptive implants in cats; some may fear using an off-label, relatively new contraceptive implant; others may not have yet used implants owing to the lack of availability in small animal practices (melatonin 18 mg implants are available in packages of 50 implants, which may restrict some private practices from using it). As there are very few available data on the recent use of contraceptive implants in cats, it justifies the interest of collecting information on these 140 breeding animals, which were implanted with either deslorelin 4.7 mg or melatonin 18 mg implants. This suggests that some French breeders have been actively searching for new means of contraception, such as these two off-label implants.

The duration of inhibition of sexual behaviour after implantation with deslorelin 4.7 mg in male breeding cats was surprisingly low (13.4 ± 3.2 months [range 8–21 months]; n = 37) vs previously described means of 19.7 ± 3 months (range 15–25 months; n = 7) 27 and 22.7 ± 6 months (range 6–30 months; n = 9). 32 The first study to evaluate the inhibition of deslorelin 4.7 mg was based on one cattery in Bulgaria, under natural light (n = 7). 27 The other study was based on nine privately owned cats that were presented to the Turkish University of Ondokuz. 32 This information raises multiple questions. Is the length of sexual behaviour inhibition of deslorelin 4.7 mg in males linked to the location of the cattery, the temperate climate found in France, the number of social contacts, the lighting, the weight or the breed of the animal? All cats lived in multi-cat households, and frequent intraspecies social contact with other males and females may affect the speed of sexual recovery. The amount of sexual solicitation, the environment and the stress factors may also be differences found between breeding and experimental catteries.

Concerning the hypothesis of weight-dependent individual variation between animals, this is contradicted by results found with Singapuras, a very small and light breed of 2–3 kg average adult weight. Mean duration found in Singapuras was 13.2 months (n = 6), while in heavy weight breeds such as Siberians and British Shorthairs, mean duration was longer (14.3 [n = 3] and 16.7 [n = 3] months, respectively) and shorter in Norwegian Forest Cats and Maine Coons (with 11 [n = 6] and 11.7 [n = 3] months, respectively) (Table 1), although the number of animals would need to be 13 per group using the common SD found here in order to achieve statistical significance. Nevertheless, weight does not seem to play as important a role as breed on the time to recovery of sexual behaviour in our studied group, in contrast to what has been described in dogs. 55

Concerning the influence of age, highly variable ages were observed in very short acting, as well as long acting, implanted cats. Therefore, the age at implantation did not appear to influence the individual variation found with the deslorelin 4.7 mg implant in the studied males.

The initial downregulation of sexual behaviour was observed at a mean of 1.6 ± 1 months (range 0.3–4 months) after implantation, but one Siberian cat mated and produced a litter of four kittens 81 days after implantation, a very late fertile mating after implantation, although all the other behavioural parameters were already downregulated. This suggests that there is an individual variation, as previously suspected, 27 which may be breed specific, on the delay between implantation and the occurrence of infertility; a Norwegian Forest Cat also mated successfully at 3 months but did not produce a litter.

Mating behaviour may persist throughout the time of full inhibition by the deslorelin 4.7 mg implant (observed in some Maine Coons and Norwegian Forest Cats), suggesting that there is a risk of female cats living with implanted males ovulating and having a pseudopregnancy induced. Compared with dogs, where males may remain fertile for 2 months after implantation, 56 tom cats appear to have a more variable downregulation.23,27 Based on this reported 81 days’ fertile mating, owners should be aware that tom cats may remain fertile after 3 months.

Reported use of ‘cut-in-half’ implants may be considered as mishandling of the product, since the implant has been tampered with before administration. Extremely high variations of inhibition were observed (14–24 months of inhibition in males and 2 months of oestrus suppression in one Sphynx female cat), indicating that this methodology should not be performed.

It has been determined that deslorelin 4.7 mg remains effective regardless of the implantation site in zoo animals. 57 The site of implantation was not specifically asked in the questionnaire and therefore this could not be assessed here in cats.

From a statistical point of view, using the common SD found in this study, a minimum of 50 cases per group would have been necessary to compare the shorter duration of action of deslorelin 4.7 mg found in males (13.4 ± 3.2 months [range 8–21 months]; n = 37) with that in females (16.0 ± 5.7 months [range 8–38 months]; n = 26). This tendency was also found at a breed level with male Norwegian Forest Cats (11 ± 1.3 months [range 9–12 months]; n = 6) and female Norwegian Forest Cats (15 ± 3.7 months [range 12–20 months]; n = 6), although a minimal number of eight animals per group would have been necessary to achieve statistical significance. This sex difference is in accordance with previous studies from Goericke-Pesch in DSH cats, but owing to our statistical limitations, other studies on a larger scale are needed in order to give more accurate scientific data on individual variations.

In females, 4.7 mg deslorelin implants suppressed oestrous behaviour for 16.0 ± 5.7 months (range 8–38 months) in 26 females. It was previously described to be suppressed for 22.7 ± 2.1 months (range 16–37 months) in 19 European Shorthair cats from the same household. 49 Individual variation appears to be higher in females than in males, with extremes observed in the same breed: 8- and 38-month inhibition periods were observed in two 14- and 19-month-old Persian females. There were more unwanted side effects in females, such as permanent oestrus, similarly to what is observed in some bitches. 24 A 4-year-old female Norwegian Forest Cat was ovariohysterectomised owing to cystic endometrial hyperplasia, but whether this disease appeared because of, or prior to, implantation is not known. One Maine Coon queen apparently developed a mammary fibroadenomatosis 3 weeks after implantation, suggesting a progesterone secretion, either prior to or post-implantation. A Maine Coon queen and a Persian queen developed lactation 1 month after implantation. To our knowledge, this is the first published study reporting this side effect in the cat, although it has already been described in 5/47 dogs. 58

The melatonin 18 mg implant had a mean efficacy of 86.4 ± 50.3 days (range 21–277 days) in 33/42 reports, from 12 different breeds. These data are in accordance with a previous report. 44 These variations appear to be related to season, with peak returns to oestrus in March vs the period of November–February (Figure 2). With melatonin input being directly linked to seasonality, the duration of inhibition and individual variations are probably somewhat associated with the French climate and seasonality. Spontaneous ovulation, which was not studied here, may affect the efficacy of the implant,42,59 and may explain the higher individual variation of efficacy similarly found in a previous study (Table 3). 44 One female Russian Blue cat had an inhibition of 277 days following implantation. An inhibition lasting longer than 9 months seems extremely rare. This cat may have developed subsequent silent heats, the breeder may not have detected an oestrus, or other pathological and environmental conditions may have influenced the interoestrus interval. The second longest reported duration was 180 days after implantation in a Sphynx female. Seven queens exhibited an oestrous behaviour between 1 and 10 days after implantation and three of these owners thought that the implant was not active. There may be a residual effect of the implant affecting the length of the next interoestrus, which would explain why the four other breeders considered the implant to be effective. Seventeen of the 33 queens were mated successfully after the end of action of melatonin implants. No side effects were reported.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first report assessing the duration of efficacy of implants in field conditions in 140 cats, based on the breeders’ information. This study may allow more accurate clinical advice for owners who are seeking safe contraceptive measures to avoid having multiple litters at the same time. These data open new perspectives on research to determine reproductive specificities of feline breeds.

Supplemental Material

Cat contraception questionnaire

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the breeders who sent their feedback. We give our thanks to K Reynaud, S Thoumire, V Piquerel and C Meurine, who helped us organise conferences for breeders.

Footnotes

Accepted: 23 December 2019

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore ethical approval was not required.

Informed consent: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore informed consent was not required. No animals or humans are identifiable within this publication, and therefore additional informed consent for publication was not required.

ORCID iD: Etienne Furthner  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3869-9614

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3869-9614

Supplementary material: The following file is available online:

Cat contraception questionnaire.

References

- 1. Romagnoli S. Progestins to control feline reproduction: historical abuse of high doses and potentially safe use of low doses. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 17: 743–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnston S, Rhodes L. No surgery required: the future of feline sterilization: an overview of the Michelson Prize & Grants in Reproductive Biology. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 17: 777–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hayden DW, Barnes DM, Johnson KH. Morphologic changes in the mammary gland of megestrol acetate-treated and untreated cats: a retrospective study. Vet Pathol 1989; 26: 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tomlinson MJ, Barteaux L, Ferns LE, et al. Feline mammary carcinoma: a retrospective evaluation of 17 cases. Can Vet J 1984; 25: 435–439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pérez-Alenza MD, Jiménez Á, Nieto AI, et al. First description of feline inflammatory mammary carcinoma: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics of three cases. Breast Cancer Res 2004; 6: R300–R307. DOI: 10.1186/ber790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mol JA, van Garderen E, Selman PJ, et al. Growth hormone mRNA in mammary gland tumors of dogs and cats. J Clin Invest 1995; 95: 2028–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Misdorp W, Romijn A, Hart AA. Feline mammary tumors: a case-control study of hormonal factors. Anticancer Res 1991; 11: 1793–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. MacDougall LD. Mammary fibroadenomatous hyperplasia in a young cat attributed to treatment with megestrol acetate. Can Vet J 2003; 44: 227–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hernandez FJ, Fernandez BB, Chertack M, et al. Feline mammary carcinoma and progestogens. Feline Pract 1975; 5: 45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Görlinger S, Kooistra HS, van den Broek A, et al. Treatment of fibroadenomatous hyperplasia in cats with aglépristone. J Vet Intern Med 2002; 16: 710–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wehrend A, Hospes R, Gruber AD. Treatment of feline mammary fibroadenomatous hyperplasia with a progesterone-antagonist. Vet Rec 2001; 148: 346–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thornton DA, Kear M. Uterine cystic hyperplasia in a Siamese cat following treatment with medroxyprogesterone. Vet Rec 1967; 80: 380–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bulman-Fleming J. A rare case of uterine adenomyosis in a Siamese cat. Can Vet J 2008; 49: 709–712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bellenger CR, Chen JC. Effect of megestrol acetate on the endometrium of the prepubertally ovariectomised kitten. Res Vet Sci 1990; 48: 112–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Keskin A, Yilmazbas G, Yilmaz R, et al. Pathological abnormalities after long-term administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate in a queen. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 518–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Watson AD, Church DB, Emslie DR, et al. Comparative effects of proligestone and megestrol acetate on basal plasma glucose concentrations and cortisol responses to exogenous adrenocorticotrophic hormone in cats. Res Vet Sci 1989; 47: 374–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pukay BP. A hyperglycemia-glucosuria syndrome in cats following megestrol acetate therapy. Can Vet J 1979; 20: 117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peterson ME. Effects of megestrol acetate on glucose tolerance and growth hormone secretion in the cat. Res Vet Sci 1987; 42: 354–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Middleton DJ, Watson AD. Glucose intolerance in cats given short-term therapies of prednisolone and megestrol acetate. Am J Vet Res 1985; 46: 2623–2625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCann TM, Simpson KE, Shaw DJ, et al. Feline diabetes mellitus in the UK: the prevalence within an insured cat population and a questionnaire-based putative risk factor analysis. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 289–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goericke-Pesch S, Georgiev P, Antonov A, et al. Clinical efficacy of a GnRH-agonist implant containing 4.7 mg deslorelin, Suprelorin, regarding suppression of reproductive function in tomcats. Theriogenology 2011; 75: 803–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ackermann CL, Volpato R, Destro FC, et al. Ovarian activity reversibility after the use of deslorelin acetate as a short-term contraceptive in domestic queens. Theriogenology 2012; 78: 817–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Novotny R, Cizek P, Vitasek R, et al. Reversible suppression of sexual activity in tomcats with deslorelin implant. Theriogenology 2012; 78: 848–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maenhoudt C, Santos NR, Fontaine E, et al. Results of GnRH agonist implants in oestrous induction and oestrous suppression in bitches and queens. Reprod Domest Anim 2012; 47 Suppl 6: 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goericke-Pesch S, Georgiev P, Atanasov A, et al. Treatment with Suprelorin in a pregnant cat. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 357–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goericke-Pesch S, Georgiev P, Fasulkov I, et al. Basal testosterone concentrations after the application of a slow-release GnRH agonist implant are associated with a loss of response to buserelin, a short-term GnRH agonist, in the tom cat. Theriogenology 2013; 80: 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goericke-Pesch S, Georgiev P, Antonov A, et al. Reversibility of germinative and endocrine testicular function after long-term contraception with a GnRH-agonist implant in the tom – a follow-up study. Theriogenology 2014; 81: 941–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goericke-Pesch S, Wehrend A, Georgiev P. Suppression of fertility in adult cats. Reprod Domest Anim 2014; 49 Suppl 2: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Novotny R, Vitasek R, Bartoskova A, et al. Azoospermia with variable testicular histology after 7 months of treatment with a deslorelin implant in toms. Theriogenology 2015; 83: 1188–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fontaine C. Long-term contraception in a small implant: a review of Suprelorin (deslorelin) studies in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 17: 766–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zambelli D, Bini C, Küster DG, et al. First deliveries after estrus induction using deslorelin and endoscopic transcervical insemination in the queen. Theriogenology 2015; 84: 773–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gültiken N, Aslan S, Ay SS, et al. Effect of deslorelin on testicular function, serum dihydrotestosterone and oestradiol concentrations during and after suppression of sexual activity in tom cats. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goericke-Pesch S. Long-term effects of GnRH agonists on fertility and behaviour. Reprod Domest Anim 2017; 52 Suppl 2: 336–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rhodes L. New approaches to non-surgical sterilization for dogs and cats: opportunities and challenges. Reprod Domest Anim 2017; 52 Suppl 2: 327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nuñez Favre R, García MF, García Mitacek MC, et al. Reestablishment of sperm quality after long-term deslorelin suppression in tomcats. Anim Reprod Sci 2008; 195: 302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cecchetto M, Salata P, Baldan A, et al. Postponement of puberty in queens treated with deslorelin. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 1224–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Risso A, Corrada Y, Barbeito C, et al. Long-term-release GnRH agonists postpone puberty in domestic cats. Reprod Domest Anim 2012; 47: 936–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carranza A, Faya M, Merlo ML, et al. Effect of GnRH analogs in postnatal domestic cats. Theriogenology 2014; 82: 138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carranza A, Faya M, Fernandez P, et al. Histologic effect of a postnatal slow-release GnRH agonist on feline gonads. Theriogenology 2015; 83: 1368–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mehl NS, Khalid M, Srisuwatanasagul S, et al. GnRH-agonist implantation of prepubertal male cats affects their reproductive performance and testicular LH receptor and FSH receptor expression. Theriogenology 2016; 85: 841–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gulyuz F, Tasal I, Uslu BA. Effects of melatonin on the onset of ovarian activity in Turkish Van cats. J Anim Vet Adv 2009; 8: 2033–2037. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gimenez F, Stornelli MC, Tittarelli CM, et al. Suppression of estrus in cats with melatonin implants. Theriogenology 2009; 72: 493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Favre RN, Bonaura MC, Praderio R, et al. Effect of melatonin implants on spermatogenesis in the domestic cat (Felis silvestris catus). Theriogenology 2014; 82: 851–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schäfer-Somi S. Effect of melatonin on the reproductive cycle in female cats: a review of clinical experiences and previous studies. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 5–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kutzler MA. Alternative methods for feline fertility control: use of melatonin to suppress reproduction. J Feline Med Surg 2015; 17: 753–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Padula AM. GnRH analogues – agonists and antagonists. Anim Reprod Sci 2005; 88: 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Coy DH, Schally AV. Gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogues. Ann Clin Res 1978; 10: 139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wright PJ, Verstegen JP, Onclin K, et al. The suppression of the oestrous responses of bitches to the GnRH analogue deslorelin by progestin. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl 2001; Suppl 57: 263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Goericke-Pesch S, Georgiev P, Atanasov A, et al. Treatment of queens in estrus and after estrus with a GnRH-agonist implant containing 4.7 mg deslorelin; hormonal response, duration of efficacy, and reversibility. Theriogenology 2013; 79: 640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sallanon M, Claustrat B, Touret M. Presence of melatonin in various cat brainstem nuclei determined by radioimmunoassay. Acta Endocrinol 1982; 101: 161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Axnér E. Updates on reproductive physiology, genital diseases and artificial insemination in the domestic cat. Reprod Domest Anim 2008; 43 Suppl 2: 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Romagnoli S, Bensaia C, Ferré-Dolcet L, et al. Fertility parameters and reproductive management of Norwegian Forest Cats, Maine Coon, Persian and Bengal cats raised in Italy: a questionnaire-based study. J Feline Med Surg 2019; 21: 1188–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Faya M, Carranza A, Priotto M, et al. Domestic queens under natural temperate photoperiod do not manifest seasonal anestrus. Anim Reprod Sci 2011; 129: 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grellet A, Mila H, Fontaine E, et al. Use of deslorelin implants to schedule canine breeding activity: a study on 442 bitches. 7th International Symposium on Canine and Feline Reproduction (ISCFR); 2012. July 29; Whistler, BC, Canada. p 77. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Trigg TE, Doyle AG, Walsh JD, et al. A review of advances in the use of the GnRH agonist deslorelin in control of reproduction. Theriogenology 2006; 66: 1507–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Romagnoli S, Siminica A, Sontas BH, et al. Semen quality and onset of sterility following administration of a 4.7-mg deslorelin implant in adult male dogs. Reprod Domest Anim 2012; 47 Suppl 6: 389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cowl VB, Walker SL, Rambaud YF. Assessing the efficacy of deslorelin acetate implants (Suprelorin) in alternative placement sites. J Zoo Wildl Med 2018; 49. DOI: 10.1638/2017-0153R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maenhoudt C, Santos NR, Fontbonne A. Suppression of fertility in adult dogs. Reprod Domest Anim 2014; 49 Suppl 2: 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Faya M, Carranza A, Priotto M, et al. Long-term melatonin treatment prolongs interestrus, but does not delay puberty, in domestic cats. Theriogenology 2011; 75: 1750–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cat contraception questionnaire