Abstract

Practical relevance:

Many of the changes that occur with aging are not considered pathologic and do not negatively affect overall wellness or quality of life. Ruling out disease is essential, however, when attempting to determine whether an aged cat can be considered ‘healthy’. A clear understanding of the normal and abnormal changes that are associated with aging in cats can help practitioners make decisions regarding medical management, feeding interventions and additional testing procedures for their aged patients.

Clinical challenges:

It can be difficult to determine if a cat is displaying changes that are appropriate for age. For example, healthy aged cats may have hematologic or serum biochemistry changes that differ from those of the general feline population. Assessment of behavioral health and cognitive changes, as well as auditory, olfactory and visual changes, can also be challenging in the aged patient.

Goals:

This is the second of two review articles in a Special Issue devoted to feline healthy aging. The goals of the project culminating in these publications included developing a working definition for healthy aging in feline patients and identifying clinical methods that can be used to accurately classify healthy aged cats. This second review proposes criteria for assessing ‘healthy aged cats’.

Evidence base:

There is a paucity of research in feline aging. The authors draw on expert opinion and available data in both the cat and other species.

Introduction

Aging refers to the natural and progressive series of life stages, beginning with conception and continuing through development, adulthood and finally senescence. Although it is often misconstrued as such, aging is not a pathologic process, but rather comprises the normal time-dependent changes that occur during the life of every living organism. Today, it is generally accepted that healthy aging is achievable in both humans and animals, and should be promoted by effective health and wellness programs. Aging wellness has been defined as ‘the development and maintenance of optimal mental, social and physical wellbeing and function in older adults.’1,2 Important components of healthy aging in humans include a variety of objective and subjective measures of cognitive, physical and psychological health.3,4

Although there is a paucity of research in feline aging, defining the important components of healthy aging in cats is possible, based on expert opinion and available data in both the cat and other species. The goals of this project included developing a working definition for healthy aging in feline patients and identifying clinical methods that can be used to accurately classify healthy aged cats. These tools are useful both for future studies of aging in cats and for use by veterinary practitioners as they differentiate between disease- and non-disease-related effects of aging in their aged patients.

A standard definition for a ‘healthy aged cat’ relies on the assumption that the absence of a disease that clinically impacts the health and wellbeing of an animal defines health as appropriate for age. As referred to in the accompaning article in this Special Issue (see right), a suggested classification for aging cats is to consider them as ‘mature’ or ‘middle-aged’ at 7–10 years, ‘senior’ at 11–14 years, and geriatric at 15+ years. 5 The degree to which aging changes influence a cat’s overall health and quality of life, and the presence (or absence) of clinical disease, must be assessed on an individual basis.

Means for assessing ‘healthy aged cats’ (as defined above) are proposed in this article. As with humans – where successful aging is defined, in part, as low probability of disease and disease-related disability, 6 and low presence of risk factors for disease – the same should apply to cats. Complete assessment criteria for each individual health area of interest are listed in tables within the relevant sections.

General health assessment

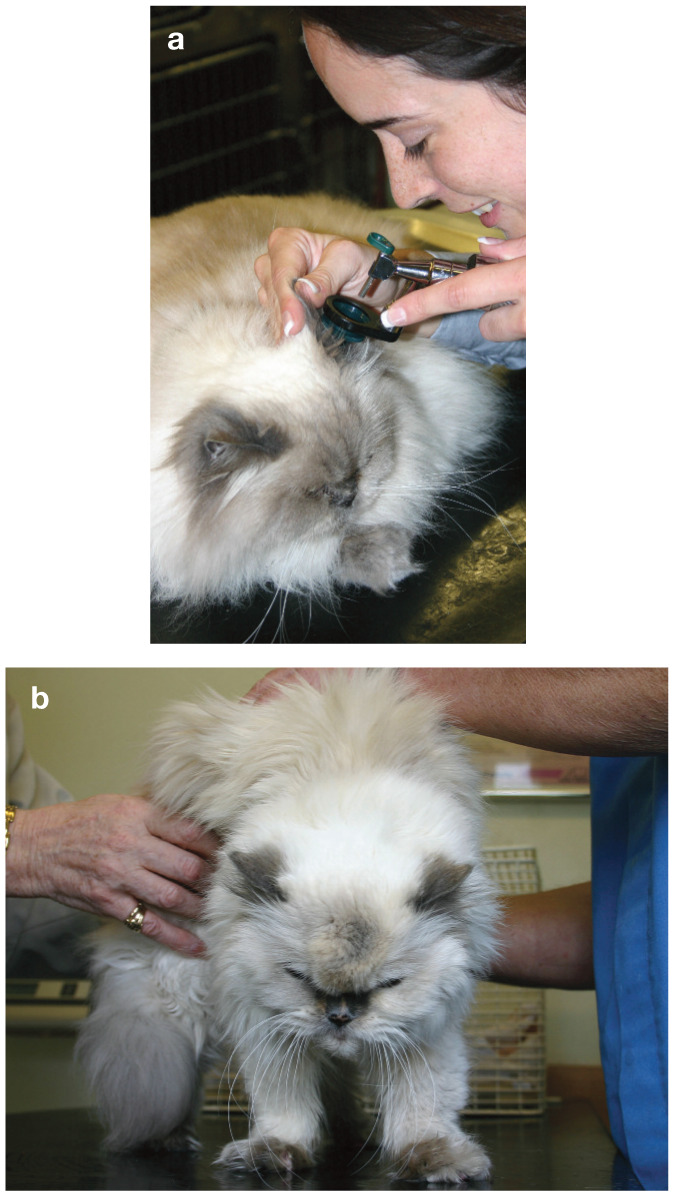

Experts have agreed that even apparently healthy aged cats should be examined at 6 month intervals (Figure 1).7,8 During these visits, a comprehensive history should be obtained by asking the owner open-ended and detailed questions about changes in the cat’s usual behavior patterns, physical activity, eating and drinking, stool quality, hearing and vision, diet, treats, supplements and medications. In addition, a complete physical examination should be performed, starting with observation from a distance of respiration, gait, stance, coordination and visual competence. Physical examination should include assessment of weight and body condition, skin and coat, oral cavity, retinal and musculoskeletal evaluation, thyroid gland palpation, cardiac auscultation and abdominal palpation.

Figure 1.

(a,b) Even apparently healthy aged cats should be assessed at 6 month intervals, incorporating a complete physical examination. Courtesy of Veterinary Record/BMJ Publications

Beginning at 7–10 years of age, collection of a minimum database composed of complete blood count (CBC), serum biochemistry profile (including, as a minimum, measuring total protein, albumin, globulin, alkaline phosphatase [ALP], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], glucose, blood urea nitrogen [BUN], creatinine, potassium, sodium and calcium), urinalysis, thyroxine (total T4) and blood pressure (BP) is recommended at least annually and with increasing frequency as cats age.7,8 Indeed, measurement of BP may be considered part of a comprehensive physical examination at any age rather than an additional test. Trends or progressive changes in the database, even with values considered in the normal range, may be important as early indicators of disease.

Because age-related physiologic changes can result in alterations in laboratory values that may be within population reference intervals, use of specific reference intervals for senior or geriatric cats may be relevant to monitor aging. 8 However, information on such specific ranges is scarce. The Iams Company Pet Health and Nutrition Center maintains a database of results of routine laboratory evaluation of large numbers of healthy cats of various ages. When reference intervals developed for all cats were compared, some important differences were identified for cats 7–10 years and cats ⩾11 years (Table 1). Specific differences compared with cats <7 years that could be clinically important included higher upper reference intervals for serum ALT, ALP, BUN, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatine kinase, creatinine, glucose, free and total T4, and white blood cells (WBCs) and neutrophils. Lower reference intervals for albumin, packed cell volume (PCV), hemoglobin, platelets, red blood cells and lymphocytes were also found. In routine health screenings in 100 apparently healthy middle-aged and old cats, cats >10 years had significantly higher platelet, BUN and bilirubin values, and lower PCV, albumin and calcium values, than 6- to 10-year-old cats, with moderate to substantial overlap between the groups. 8

Table 1.

Reference intervals for healthy aged (mature to geriatric) cats

| Age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7–10 years | 11+ years | ||||

| Parameter | Reference interval (US [conventional] units) | Reference interval (SI units) | Reference interval (US [conventional] units) | Reference interval (SI units) | |

| Serum biochemistry profile | A/G ratio | 0.8–1.8 | Same | 0.6–1.6 | Same |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 36.0–132.0 U/l | Same | 33.0–189.0 U/l | Same | |

| Albumin | 2.9–4.2 g/dl | 29.0–42.0 g/l | 2.7–4.3 g/dl | 27.0–43.0 g/l | |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 12.0–54.0 U/l | Same | 14.0–72.0 U/l | Same | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 16.0–54.0 U/l | Same | 15.0–72.0 U/l | Same | |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) | 15.4–35.0 mg/dl | 5.5–12.5 mmol/l | 16.0–44.8 mg/dl | 5.7–16.0 mmol/l | |

| Calcium | 8.8–11.3 mg/dl | 2.2–2.8 mmol/l | 8.9–11.8 mg/dl | 2.2–3.0 mmol/l | |

| Chloride | 113.0–131.0 mmol/l | Same | 113.0–130.0 mmol/l | Same | |

| Cholesterol | 128.0–335.0 mg/dl | 3.3–8.7 mmol/l | 121.0–335.0 mg/dl | 3.1–8.7 mmol/l | |

| Creatine kinase (CK) | 65.0–1004.0 U/l | Same | 65.0–820.0 U/l | Same | |

| Creatinine | 1.3–3.3 mg/dl | 114.9–291.7 μmol/l | 1.3–3.6 mg/dl | 114.9–318.2 μmol/l | |

| Globulin | 2.1–4.3 g/dl | 21.0–43.0 g/l | 2.2–4.7 g/dl | 22.0–47.0 g/l | |

| Glucose | 66.0–248.0 mg/dl | 3.7–13.8 mmol/l | 66.0–206.0 mg/dl | 3.7–11.4 mmol/l | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | 47.0–371.0 U/l | Same | 46.0–335.0 U/l | Same | |

| Magnesium | 1.7–3.3 mEq/l | 0.85–1.65 mmol/l | 1.5–3.1 mEq/l | 0.75–1.55 mmol/l | |

| Phosphorus | 3.2–6.4 mg/dl | 1.0–2.0 mmol/l | 3.4–6.4 mg/dl | 1.1–2.0 mmol/l | |

| Potassium | 3.4–5.8 mmol/l | Same | 3.3–5.6 mmol/l | Same | |

| Sodium | 146.0–163.0 mmol/l | Same | 147.0–163.0 mmol/l | Same | |

| Total bilirubin | 0.1–0.2 mg/dl | 1.7–3.4 μmol/l | 0.1–0.2 mg/dl | 1.7–3.4 μmol/l | |

| Total protein | 5.5–7.8 g/dl | 55–78 g/l | 5.6–8.0 g/dl | 56–80 g/l | |

| Triglycerides | 13.0–106.0 mg/dl | 0.15–1.2 mmol/l | 11.0–123.0 mg/dl | 0.12–1.4 mmol/l | |

| Thyroid hormone | Free T4 | 0.5–1.5 ng/dl | 6.4–19.3 pmol/l | 0.5–2.0 ng/dl | 6.4–25.7 pmol/l |

| Total T4 (thyroxine) | 0.9–2.5 ng/dl | 11.6–32.0 nmol/l | 0.8–3.5 ng/dl | 10.3–45.0 nmol/l | |

| Complete blood count | Hematocrit (HCT) | 27.8–50.4% | Same | 26.3–49.9% | Same |

| Hemoglobin (Hgb) | 8.5–15.6 g/dl | 85–156 g/l | 7.8–15.8 g/dl | 78–158 g/l | |

| Mean cell volume (MCV) | 39.2–52.0 fl | Same | 37.9–51.4 fl | Same | |

| Mean cell hemoglobin (MCH) | 12.1–15.9 pg | Same | 11.5–16.0 pg | Same | |

| Mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) | 28.5–33.0 g/dl | 285–330 g/l | 28.4–33.2 g/dl | 284–332 g/l | |

| Platelet (PLT) count | 87.5–564.0 × 103/µl | 87.5–564.0 × 109/l | 99.2–505.0 × 103/µl | 99.2–505.0 × 109/l | |

| Red blood cell (RBC) count | 6.3–11.5 × 106/µl | 6.3–11.5 × 1012/l | 5.7–11.6 × 106/µl | 5.7–11.6 × 1012/l | |

| White blood cell (WBC) count | 3.1–16.2 × 103/µl | 3.1–16.2 × 109/l | 3.7–16.4 × 103/µl | 3.7–16.4 × 109/l | |

| Differential blood count | Bands, % | 0.0–0.0% | Same | 0.0–0.0% | Same |

| Bands, absolute | 0.0–0.1 × 103/µl | 0.0–0.1 × 109/l | 0.0–0.1 × 103/µl | 0.0–0.1 × 109/l | |

| Basophils, % | 0.0–1.2% | Same | 0.0–1.5% | Same | |

| Basophils, absolute | 0.0–0.1 × 103/µl | 0.0–0.1 × 109/l | 0.0–0.2 × 103/µl | 0.0–0.2 × 109/l | |

| Eosinophils, % | 0.7–17.0% | Same | 0.0–17.0% | Same | |

| Eosinophils, absolute | 0.0–1.6 × 103/µl | 0.0–1.6 × 109/l | 0.0–1.7 × 103/µl | 0.0–1.7 × 109/l | |

| Lymphocytes, % | 6.0–59.0% | Same | 5.9–51.0% | Same | |

| Lymphocytes, absolute | 0.6–5.1 × 103/µl | 0.6–5.1 × 109/l | 0.5–4.8 × 103/µl | 0.5–4.8 × 109/l | |

| Monocytes, % | 0.0–10.7% | Same | 0.0–11.0% | Same | |

| Monocytes, absolute | 0.0–1.1 × 103/µl | 0.0–1.1 × 109/l | 0.0–1.2 × 103/µl | 0.0–1.2 × 109/l | |

| Neutrophils, % | 31.0–85.0% | Same | 38.0–85.0% | Same | |

| Neutrophils, absolute | 1.5–11.0 × 103/µl | 1.5–11.0 × 109/l | 2.0–11.4 × 103/µl | 2.0–11.4 × 109/l | |

These reference intervals were generated from results for 627 healthy cats, including 211 (7–10 years) and 149 (11+ years) cats, housed at The Iams Company Pet Health and Nutrition Center between 2002 and 2011

Parameters were measured in US (conventional) units and mathematically converted to SI units T4 = thyroxine; A/G ratio = albumin to globulin ratio

These findings suggest that healthy aged cats may have some hematologic or serum biochemistry changes that differ from those for the general population of cats and should be monitored longitudinally in order to detect disease early. Thus, results obtained from commercial laboratories should be interpreted with caution if reference intervals have not been developed by those laboratories for different age groups. Additionally, while reference intervals represent a clinically healthy population, an individual value within a reference interval does not rule out underlying disease. For example, upper reference intervals for creatinine may fall above IRIS classification for stage 2 or 3 renal disease. Therefore, every patient must be evaluated based on the individual history and full diagnostic profile to achieve a complete and accurate assessment.

Cognitive and behavioral health assessment

Assessing behavioral health and cognitive changes can be challenging in the cat. Because cats are often sedentary, it may take some time for owners to recognize that a cognitive-related change has occurred. Laboratory testing has indicated that changes in cognition may begin at between 10 and 12 years of age. Similar to the dog, a cat experiencing cognitive decline is likely to show disorientation, interaction changes, sleep/wake disturbances, house-soiling and changes in activity (the so-called DISHA pattern reported in dogs 9 ). In cats, cognitive dysfunction may also manifest as increased activity, pacing and excessive vocalization. Whether these are signs of anxiety or solely due to cognitive changes is hard to determine. Most vocalizations sound as though the cat is distressed, but pain, loss of vision and other causes are likely contributory.

Vocalization and restlessness are common behavioral signs in aging cats, based on the studies mentioned below. It is especially important to address house-soiling as this behavior may result in euthanasia of the cat. A valuable resource offering practical advice in this area are the recent AAFP and ISFM guidelines on house-soiling behavior in cats. 10 Naturally, many medical problems can present with similar behavioral changes, so the diagnosis of cognitive dysfunction is one of exclusion. 10

Prevalence of cognitive changes and behavior problems

Information on the prevalence of cognitive changes and behavior problems in aged cats is gradually becoming available. Moffat and Landsberg (cited by Gunn-Moore et al 11 ) used a questionnaire to evaluate any changes in behavior in 154 cats aged 11–21 years. Owners were asked a series of questions with particular emphasis on signs related to cognitive changes. Sixty-seven cats (44%) had behavioral signs reported, but 19 cats also had concurrent medical problems. Once the 19 cats were excluded from the analysis, 36% of the remaining 48 cats exhibited behavioral signs not associated with a diagnosed underlying disease. The incidence of behavioral signs increased with age, with 50% of cats >15 years of age and 28% of cats 11–14 years of age being affected. In this study, cats 11–14 years of age were more likely to show alterations in social interactions, while older cats were reported to show alterations in activity and excessive vocalization.

A survey on the Veterinary Information Network (VIN) examined the 100 most recent behavioral complaints of cats 12–22 years of age. 12 The following results were reported: excessive vocalization in 61% (night-time vocalization in 31%), house-soiling (elimination and marking) in 27%, disorientation in 22%, aimless wandering in 19%, restlessness in 18%, irritability/aggression in 6%, fear/hiding in 4% and clingy attachment in 3%.

It appears, therefore, that it is reasonable to assume that a certain proportion of aging cats will suffer from cognitive dysfunction syndrome (CDS).

Assessment methods

Currently, there is no standardized, validated method for evaluating cognitive function in aged cats outside the laboratory. It is assumed based on the aforementioned surveys, case reports and laboratory assessment that cats will exhibit similar behavioral changes associated with both normal aging and the progression of CDS. It is also likely that utilization of the acronym DISHA is appropriate for categorizing the behavioral changes associated with CDS in the cat.

As with dogs, CDS should be diagnosed only when other causes of behavioral changes, including those related to sensory decline, pain, environmental changes and underlying diseases, have been ruled out. The behavioral signs of CDS are also secondary signs of fairly ubiquitous degenerative diseases and normal aging in older cats; however, it is possible for a cat to have both a primary medical problem and cognitive decline. In one study, cats >10 years of age had several laboratory and health changes from what would be considered normal baseline, despite appearing healthy. 8 These findings underscore the need not only for frequent screening but also more information on normal aging in cats. 8 Therefore, wellness examinations in aged cats should include a basic behavioral assessment (Table 2), along with a comprehensive physical and laboratory examination, as described earlier.

Table 2.

Cognitive/behavioral health evaluation*

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy |

|---|---|---|

| Query owner: Recent or sudden changes in behavior or temperament? | No changes or areas of concern | Sudden changes or areas of concern |

| If possible, assess general exam room health and behavior | Normal and responsive | Abnormal and/or non-responsive |

| Apply CDS screening questionnaire (Table 4) | No CDS | CDS suspected or present |

After ruling out vision and hearing loss and other medical issues

CDS = cognitive dysfunction syndrome

Specific screening questions regarding behavioral changes are included in the following sections and in Table 3. The clinician is encouraged to use this chart to detect trends in cognitive changes. Because CDS is progressive, serial evaluations may be necessary to evaluate decline. 10 Questions include those targeting changes in social interactions and activity, as well as night-time vocalization and house-soiling or litter box habits, because these are the most commonly cited problems in aged pets and are related to cognitive decline (Figure 2). 10

Table 3.

| Frequency | Severity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often does your cat: | Never | 1–2 times/month | Once a week to 3–4 times/week | Once a day/most of the time | >Once a day/always | Score 0–3* | |

| Disorientation and memory | Pace, walk in circles and wander with no purpose? | ||||||

| Stare into space? | |||||||

| Show alterations in learning or memory? | |||||||

| Show forgetfulness? | |||||||

| Forget that it has been fed? | |||||||

| Appear to get lost in the house? | |||||||

| Interactions | Walk away or avoid interactions? | ||||||

| Show clingy and irritable behaviors at the same time? | |||||||

| Yowl or vocalize at inappropriate times or locations? | |||||||

| Show altered relationships with other household pets? | |||||||

| Sleep–wake cycles | Sleep more and/or is less active? | ||||||

| Exhibit increased night-time waking/activity? | |||||||

| House-soiling | Eliminate outside of the litterbox? | ||||||

| Activity and anxiety | Show changes in appetite or interest in food? (increase or decrease) | ||||||

| Play less with other animals or toys? | |||||||

| Show changes in grooming habits? | |||||||

| Show changes in ability to move, jump or be agile? | |||||||

| Show changes in exploration or activity? | |||||||

| Show an anxiety/fear/phobia of people? | |||||||

| Show an anxiety/fear/phobia of noises? | |||||||

| Show an anxiety/fear/phobia of places? | |||||||

0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe

It is appropriate to begin screening for cognitive dysfunction when a cat is 8–9 years of age. A change in the frequency or intensity of signs over time in the DISHA categories in the absence of medical disease would likely indicate cognitive dysfunction. In addition, scores of 2 or 3 in the last column in several of the DISHA categories – again in the absence of medical explanations – would point to a diagnosis of cognitive dysfunction syndrome

Figure 2.

Changes in behavior – increased vocalization, and altered social interactions, both with other pets and owners – can suggest cognitive decline in the older cat. This is a diagnosis of exclusion and its recognition requires careful questioning of the owner. © iStock/legna69 (a), © iStock/Konstik (b), © iStock/Vanhop (c)

This chart can be used at routine examinations or in acute situations where an aged cat is exhibiting profound changes in behavior. Excluding treatable diseases before diagnosing CDS is essential, especially when the behavioral changes are unacceptable to the owner. Table 4 lists medical conditions that can have similar, overlapping behavioral signs.

Table 4.

| Medical condition | Associated clinical signs |

|---|---|

| Sensory dysfunction (loss of vision, hearing, smell) | • Increased irritability, fear or aggression • Decreased appetite • Increased vocalization • Changes in sleep–wake cycle • Disorientation • Decrease in greeting behavior • Inattentiveness, decreased responsiveness to verbal interactions |

| Kidney disease | • Polyuria • Polydipsia • Change in litterbox habits and/or house-soiling 9 |

| Lower urinary tract infection | • Dysuria • Stranguria • Pollakiuria • Periuria • Change in litterbox habits and/or house-soiling |

| Osteoarthritis | • Weakness • Reduced mobility and activity • Increased pain and irritability • Change in litterbox habits and/or house-soiling • Reluctance to engage in normal daily activities |

| Hyperthyroidism | • Anxiety • Restlessness • Night-time vocalization • Increased appetite • Hyperactivity • Change in litterbox habits and/or house-soiling |

| Hypothyroidism | • Decrease in activity • Increased irritability or aggression • Reduced tolerance to cold • Mental dullness |

| Hyperadrenocorticism | • Lethargy • Weight loss • Change in litterbox habits and/or house-soiling • Polyphagia • Polydipsia • Polyuria |

| Central neurologic disorders (primary or secondary intracranial neoplasia) | • Changes in sleep patterns • Change in eating habits • Change in litterbox habits and/or house-soiling • Aggression or docility |

| Peripheral neuropathy | • Self-mutilation • Irritability/aggression • Circling • Hyperesthesia • Change in litterbox habits and/or house-soiling |

| Pain | • Altered response to stimuli • Decreased activity • Restlessness (unsettled) • Vocalization • Change in litterbox habits and/or house-soiling • Aggression/irritability • Self-trauma • Waking at night |

| Gastrointestinal disease | • Licking • Polyphagia or decreased appetite • Change in litterbox habits/house-soiling (fecal) • Unsettled sleep • Restlessness • Vocalization |

| Urogenital disease | • Dysuria • House-soiling (urine) • Pollakiuria • Polydipsia • Polyuria • Stranguria • Waking at night |

| Dermatologic disease | • Overgrooming, hair plucking • Nail biting • Hyperesthesia • Other self-trauma (chewing/biting/sucking/scratching) |

| Metabolic disorders (eg, diabetes mellitus) | Signs associated with organ affected: • Anxiety • Irritability • Aggression • Altered sleep • House-soiling • Mental dullness • Decreased activity • Restlessness • Increased sleep • Confusion |

| Systemic hypertension* | • Confusion • Vocalization • Wandering |

May be primary or secondary to hyperthyroidism, chronic kidney disease or, possibly, diabetes mellitus, acromegaly, hyperaldosteronism or hyperadrenocorticism

Skin and coat health assessment

As discussed, a physical examination of aged cats should include thorough assessment of the skin and coat, along with questioning the owner regarding any recent changes in the cat’s skin or coat, the presence of new or rapidly growing skin lesions or growths, and changes in self-grooming behavior (Table 5). 8 Several types of skin tumors are frequently observed in older cats, with benign basal cell tumors and basal cell carcinomas being among the most common. 15

Table 5.

Skin and coat health evaluation

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy |

|---|---|---|

| Query owner: Changes in cat’s grooming activity? Recent hair loss? Sudden growth of skin lesions or bumps? Changes in the shedding cycle? | Normal or slightly reduced self-grooming activity; no recent changes or growths | Major changes in selfgrooming activity; sudden change in coat density, shedding cycle or texture; appearance of new or unusual skin lesions or growths |

| Evaluate coat color | Accumulating white hair in the coat | Not applicable |

| Assess coat quality | Slight thinning; normal to slightly dry or greasy coat; no significant alopecia | Severely dry or greasy, brittle and dull coat; excessive skin flaking (dander); significant alopecia |

| Examine skin and nails | Rare small growths that do not increase in size, ulcerate or inhibit normal activity; less elastic skin; thick, brittle nails; mild chin acne or comedones; mild erythema or crusting around ears, nose and lips on light-colored faces | Presence of lesions or growths rapidly changing in size or with an abnormal appearance; non-healing lesions; markedly less elastic skin; abnormal nails; severe chin acne; marked erythema or crusting around ears, nose and lips on lightcolored faces |

Clinically, chin acne and comedones (Figure 3) are common findings in older cats. In addition, mild erythema, scaling and crusting on and around the ears, nose and lips may be noted in cats with white or light-colored faces from sun exposure. 16 Such signs must be differentiated from solar-induced squamous cell carcinoma, which not only may resemble solar keratosis but can also coexist with non-neoplastic lesions.

Figure 3.

Mild chin acne (a) and comedones (b) are normal findings in the healthy aged cat. Images courtesy of Margie Scherk

Weight and body condition assessment

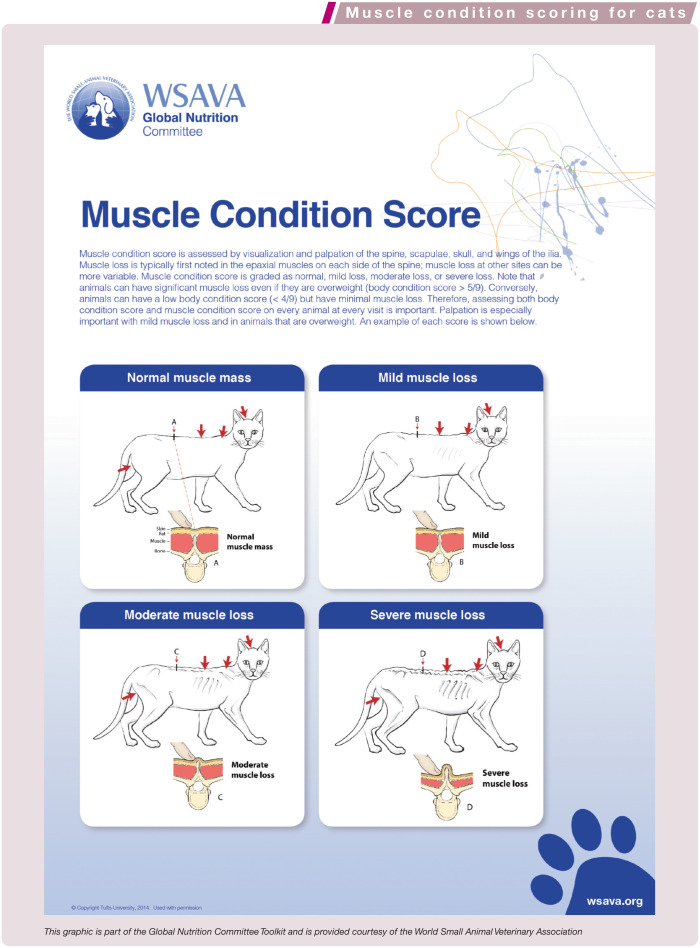

In addition to body weight, body condition score (BCS) and muscle condition score (MCS) are important to assess routinely in aging cats (see Table 6 and boxes on pages 558 and 559). Visual and tactile assessment of body condition helps to evaluate fat component (ie, caloric intake), while assessment of muscle condition helps to assess dietary protein adequacy and possible cachexia due to inflammation. As part of a comprehensive physical examination, these scales provide valuable information at no additional cost for the owner.

Table 6.

Weight and body condition health evaluation

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy |

|---|---|---|

| Query owner: Recent weight change? Change in food intake? | No recent or sudden change | Change in weight and/or food intake |

| Measure BW; compare with cat’s BW during previous examinations and/or estimated ideal BW for size | Appropriate BW; no sudden change | Recent or sudden weight gain or loss |

| Palpate body conformation and body fat | Appropriate for size | Excessively thin or overweight |

| Assess body condition using a 5-point* or 9-point † BCS scale | BCS 2.5–3.5 on a 5-point scale; 4–5 on a 9-point scale | BCS <2.5 or >3.5 on a 5-point scale; <4 or >5 on a 9-point scale |

| Assess MCS (visual examination and palpation) | Normal MCS (no muscle wasting, normal muscle mass) | Moderate to severe decrease in MCS |

| Calculate % weight change: (previous weight – current weight)/previous weight | No change, or ⩽5% | >5% |

5-point BCS scale: 1 = extremely thin, cachectic; 2 = lean, underweight; 3 = ideal weight; 4 = overweight; 5 = obese

9-point BCS scale: 1 = extremely thin; 4–5 = ideal; 9 = obese

BW = body weight; BCS = body condition score; MCS = muscle condition score

Values for BCS and MCS should be compared against standard tables, and changes should be monitored longitudinally over time. Additionally, calculation of percentage weight change can help identify subtle but significant weight loss (or gain). Wellness exams that include these evaluations can provide a method of early detection of weight gain or muscle loss and allow for the appropriate invention to slow the progression and minimize associated potential adverse effects. Obesity in cats is associated with increased risk for reduced mobility and diabetes. 17 As discussed in the accompanying article, both weight loss and sarcopenia are associated with increased risk of death.18–22 Therefore, the importance of monitoring body condition cannot be over-emphasized.

Owner recognition of healthy weight and muscle tone, and understanding of its influence on healthy aging, are integral to successful management of body condition. Practitioners should have this discussion with clients during every wellness visit. Displaying BCS silhouettes and having owners identify the silhouette best representing their cat’s physique can be eye opening. Owners should also be encouraged to provide information regarding their cat’s activity level and quantity of food, treats and supplements eaten, along with brand names.

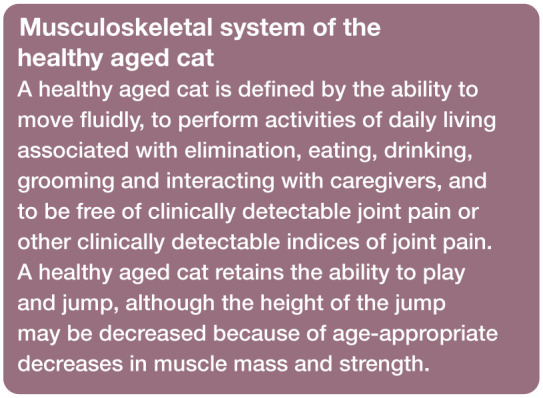

Musculoskeletal health assessment

Evaluation of the musculoskeletal system involves observation of mobility; physical and orthopedic evaluation of muscles and joints; evaluation of somatosensory processing; assessment by the owner of mobility, activity and ability to perform activities; and owner assessment of quality of life (Table 7).

Table 7.

Musculoskeletal health evaluation

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Query owner* | Pain | Absence of pain | Signs of pain |

| Perception of the ability to perform normal daily activities | Able to perform normal daily activities, including jumping, although these may be performed less often, and the height and frequency of jumping may be decreased | Difficulty in performing normal daily activities, such as elimination, jumping and/or moving around the environment | |

| Ease of movement | Moves easily | Awkward or stilted movement | |

| Quality of life | Excellent quality of life | Compromised quality of life | |

| Use of analgesics | None, or nutritional supplements only | Occasional or frequent use of pharmaceutical compounds for pain relief | |

| Observe mobility | Combined limb, muscle and neurologic function | Moves fluidly; slow movement acceptable | Stilted, non-fluid movement |

| Perform physical examination, and orthopedic examination of muscle mass and joints | Joints | No pain on moderate manipulation (flexion, extension and torsion) of joints. (Crepitus, effusion or thickening may be present, or evidence of DJD may be seen radiographically but is not associated with any pain) | Pain on moderate manipulation (flexion, extension and torsion) of joints (with or without crepitus, effusion or thickening, or radiographic evidence of DJD) |

| Muscle mass | Normal, or age-appropriate symmetrical decreases in muscle mass over spine, scapulae, skull, wings of the ilia, triceps and thigh muscles. The spine of the scapula, shaft of the humerus and shaft of the femur, wings of the ilium and transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae should not be readily palpable, although they may be more prominent than in younger animals. No asymmetry of muscle mass loss | Excessive decreases in muscle mass over the spine, scapulae, skull, wings of the ilia, triceps and thigh muscles. Asymmetrical loss of muscle mass | |

| Somatosensory function | No excessive sensitivity on palpation of body structures or on gentle handling of, or touching, the skin | Excessive sensitivity, demonstrated as skin twitching, muscle fasciculations, withdrawal from gentle touch and/or aggressive response to gentle touch | |

Use the available tools23–25 and also the feline musculoskeletal pain index at https://cvm.ncsu.edu/research/labs/clinical-sciences/comparative-pain-research/clinical-metrology-instruments/

DJD = degenerative joint disease

Healthy cats move fluidly, with grace and ease. Older healthy cats may move less quickly but still move fluidly. Muscle mass decreases with age (see box on page 559). This can be assessed by evaluating muscle over the spine, scapulae, skull, wings of the ilia, triceps and thigh muscles. 26 Muscle loss should be age appropriate and not excessive. The spine of the scapula, the shaft of the humerus and shaft of the femur, the wings of the ilium and transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae will be slightly more readily palpated in older healthy cats, but should not be readily palpable and should be surrounded or flanked by at least moderate amounts of muscle mass, with no more than mild muscle loss.

Detectable loss of muscle mass (Figure 4), either regionally involving a limb or more generally, may be an indicator of degenerative joint disease (DJD). Loss of muscle mass may also be indicative of other systemic disease (ie, the result of changes in digestive capacity, insulin-mediated changes in tissue nutrient uptake, renal disease, hyperparathyroidism and cancer-related muscle loss) or inadequate dietary protein.

Figure 4.

Muscle wasting is visually apparent over the thighs in this cat. On palpation, muscle loss was also evident over the scapulae, in the epaxial muscles, and over the ribs and hips. Courtesy of Margie Scherk

DJD is very common in cats.27,28 Clinically detectable signs of this problem include pain, crepitus, effusion and thickening of the affected joint(s). 29 A healthy cat should not respond to manipulation of joints with a pain response. However, these joints may have detectable signs of DJD (crepitus, thickening). The presence of crepitus, effusion and thickening increases the risk of pain being associated with a joint, so the clinician should assess any such joint carefully (Figure 5). 29 It has been shown that clinically significant DJD is associated with a decreased range of motion; 29 a healthy aged cat should have a normal range of motion of each joint. 30

Figure 5.

A healthy aged cat should have normal range of motion for each joint on orthopedic examination. Courtesy of Duncan Lascelles

Although not well defined, chronic musculoskeletal pain can lead to central sensitization and hypersensitivity. 31 A healthy cat should not show excessive sensitivity to touch and manipulation.

Only recently has work been carried out to produce a valid owner-administered clinical metrology instrument for the assessment of musculoskeletal pain in the cat.23,32,33 The first version of a Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Index 23 is now available (https://cvm.ncsu.edu/research/labs/clinical-sciences/comparative-pain-research/clinical-metrology-instruments/) and can be used to assess the impact of musculoskeletal pain, with lower scores indicating lower impairment or normality. This instrument was able to detect the efficacy of low-dose meloxicam treatment, especially when combined with a novel clinical study design. 25

An assessment tool has been produced and evaluated to help gauge the effect of musculoskeletal pain and DJD on a cat’s quality of life. 24

Special senses health assessment

Assessing aged cats for auditory, olfactory and visual changes can be difficult. Because most cats come into the examination room in a carrier, it is not possible to assess their ability to navigate an unfamiliar area when they first enter the room. Additionally, many cats are very frightened in the veterinary clinic and do not move much at all. Blind animals may be reluctant to walk, or may bump into objects, refuse to jump or show an altered gait. Attempts to gauge visual ability may be difficult if the cat is merely ignoring the object or is too stressed to respond. 34

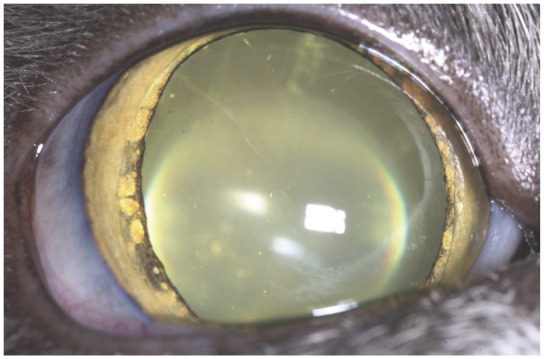

Lenticular (nuclear) sclerosis is common in the aging cat and is considered a normal age-related development (Table 8, Figure 6). Rarely would the changes associated with lenticular sclerosis impair vision and daily function, except perhaps in low light for some individuals. Loss of vision may occur because of retinal degeneration or secondarily to retinal detachment as a result of hypertension, trauma, neoplasia, inflammatory diseases, nutritional deficiency (taurine), toxins, infectious agents and other medical causes. 35

Table 8.

Special senses health evaluation

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy |

|---|---|---|

| Query owner: Sudden changes in vision, hearing or smell? Do visual or hearing losses affect daily activities and quality of life? Does night-time vocalization occur? | No change to moderate change in vision/hearing/ smell; slight to moderate (manageable) changes in daily activities and quality of life | Severe changes that include difficulties navigating, walking into obstacles; increased vocalization at night; decreased response to sound; altered response to diet flavors |

| Perform external examination of the eye and surrounding tissue | Normal results; iris atrophy | Abnormal findings |

| Perform internal examination of the eye lens (tapetal reflection, slit lamp biomicroscope) | Lenticular sclerosis likely present; normal or near-normal vision | Presence of cataracts or other lens abnormality, corneal ulcers, retinal degeneration, blindness |

| Measure intraocular pressure (tonometer) | 14–20 mmHg (normal results) | >20 mmHg indicates glaucoma; <14 mmHg consistent with uveitis |

| Perform external ear and otoscopic examination | Normal results | Abnormal findings or ruptured tympanic membrane |

| Conduct hearing examination (general function tests, BAER if available) | Normal to moderate hearing loss | Severe hearing loss that impacts quality of life |

| Assess olfactory function (alcohol-soaked swab under nose) | Withdrawal of head from aversive smell | No response to aversive smell |

BAER = brainstem auditory evoked response

Figure 6.

Lenticular sclerosis and iris atrophy in an aging cat. Courtesy of David A Wilkie

Hearing loss can be difficult to quantify but may be noted in the behavioral history by lack of response to verbal cues (eg, calling the cat to come at feeding time), and also by persistent vocalization. Acquired hearing loss can occur because of illness, head trauma, ototoxic drugs and exposure to loud noise, including street noise. 36

Loss of smell may be assessed by changes in eating habits since olfaction plays a major role in the feeding behavior and appetite of cats. Information obtained by questioning the owner about changes in appetite and eating may, in the absence of any other medical or dental problems, help identify a decline in or loss of smell as an issue.

Oral and gingival health assessment

Oral cavity disorders (including periodontal disease, gingivitis, tooth resorption, stomatitis and oral cavity tumors) are an often overlooked cause of significant morbidity in older cats. Appropriate treatment for these conditions commonly results in marked improvement in quality of life and activity. 37 Owner intervention in plaque accumulation can have a major impact on the establishment and progression of periodontal disease in cats. If the owner strictly controls plaque, the periodontium remains healthy and the teeth should remain well anchored in their alveoli. Conversely, if the owner does not establish a plaque control regimen, gingival inflammation commonly occurs and may develop into periodontal disease.

Assessment of the oral cavity in the aging cat should start with questioning the client regarding signs of pain, changes in eating habits and bad breath (Table 9). Common signs of oral disease include inappetence, weight loss, halitosis, chattering teeth, abnormal chewing and/or swallowing behavior, decreased grooming, and nasal discharge (usually unilateral). Exam room physical evaluation of aged cats should include thorough visual examination of the oral cavity, including mucosa, gingiva and dental hard tissue. If the patient will allow it, applying a cotton-tipped applicator with moderate pressure to the buccal gingival margins can indicate underlying dental disease if it results in gingival bleeding and/or pain.

Table 9.

Oral and gingival health evaluation

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy |

|---|---|---|

| Query owner: Signs of mouth pain? Changes in chewing/eating habits? Presence of malodorous breath? Presence of nasal discharge? | No signs of pain or changes in eating/chewing habits; no or minimal mouth odor | Frequent pain or refusal to eat; change in chewing habits; moderate to severe mouth odor Unilateral nasal discharge or progression from uni- to bilateral, often sanguineous |

| Evaluate the mouth for fractured teeth ± pulp exposure | No fractured teeth | Fractured enamel, dentin and/or pulp exposure |

| Evaluate the mouth for oral masses | None | Oral masses or abnormal facial swelling |

| Apply cotton-tipped applicator with moderate pressure to buccal gingival margins | No bleeding or pain elicited | Bleeding and/or pain |

| Conduct periodontal probing in cases of gingival recession; the attachment level is measured from the cementoenamel junction to the apical extent of the pocket | Normal (probing depth ⩽1 mm in medium-sized cats) | Abnormal (probing depth >1 mm) |

| Assess tooth surface with dental explorer | Smooth enamel and dentin | Pitted enamel or dentin |

| Perform intraoral Radiography | No abnormalities noted | Loss of enamel or dentin (dental hard tissue) |

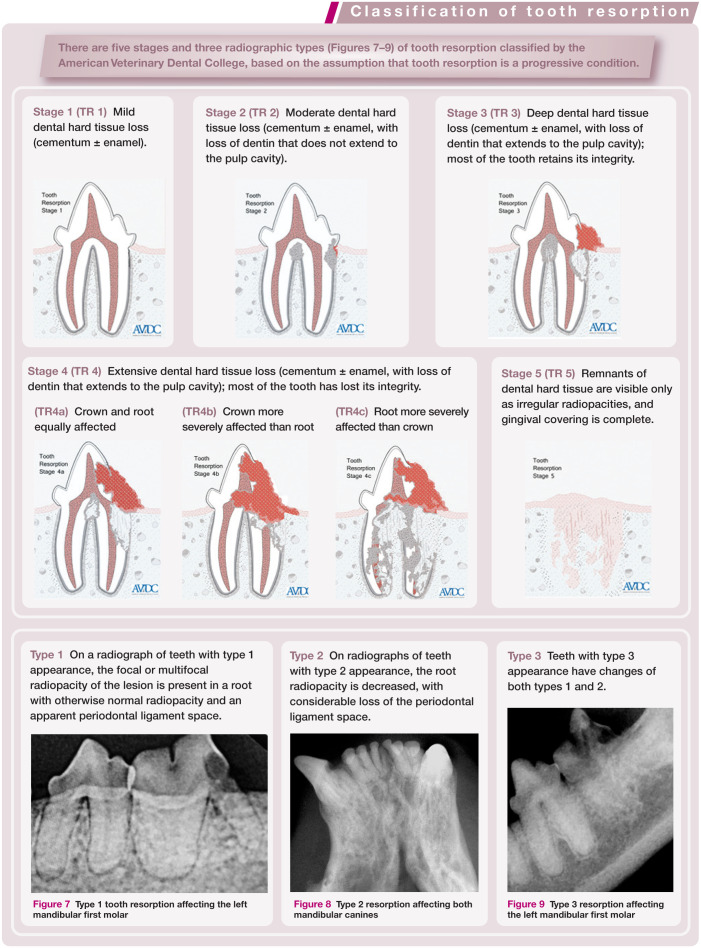

Figure 7.

Type 1 tooth resorption affecting the left mandibular first molar

Figure 8.

Type 2 resorption affecting both mandibular canines

Figure 9.

Type 3 resorption affecting the left mandibular first molar

For a complete oral examination, anesthesia with intubation is necessary to properly immobilize the cat for an in-depth, tooth-by-tooth examination, including dental scaling and polishing, periodontal probing, exploring for tooth resorption and intraoral radiology.

Every professional oral hygiene procedure conducted under general anesthesia should include probing and charting. The clinical or probing depth is the distance between the base of the pocket and the gingival margin. Healthy cats normally have probing depths <1 mm. Greater depths may indicate periodontal disease requiring further evaluation and treatment.

Intraoral radiology is an important diagnostic aid for evaluating dental disease in the aging cat. The lamina dura of each tooth should be inspected to see whether it is continuous or breached. An intact lamina dura generally indicates good periodontal health. In cases of early and established periodontal disease, the coronal lamina dura appears radiographically indistinct, irregular and fuzzy.

Resorption of the alveolar bone at advanced stages of periodontal disease leads to widening of the periodontal ligament space and loss of lamina dura. When viewing the lamina dura and the periodontal ligament space, only the interproximal portions are visible. With disease, the periodontal ligament space may be of variable thickness in appearance, indicating that involvement is not consistent around the entire root. 38

Intraoral radiography is also used to evaluate tooth resorption (see box on page 563).

For a fuller discussion of oral and gingival health assessment techniques, the reader is referred to two Special Issues of this journal devoted to feline dentistry (accessed at cpsi.jfms.com).

Gastrointestinal health assessment

Stool quality and quantity, overall body condition and weight, and the daily quantity of food that is fed can be clinical indicators of normal, healthy gastrointestinal (GI) function in older cats. These factors should be regularly assessed in aged cats via BCS and MCS evaluation; visual oral/dental examinations; visual and tactile abdominal examinations; fecal centrifugation flotation and smear evaluation; and serum biochemistry profile evaluation and CBC (see Table 1). In addition, owners should be asked about changes in defecation frequency, stool quality/quantity, appetite and activity level, and any vomiting and colic (Table 10).

Table 10.

Gastrointestinal health evaluation

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy |

|---|---|---|

| Query owner: Changes in defecation frequency or stool quality/quantity? Presence of vomiting, GI distress or discomfort? Changes in appetite or activity level? | No or minimal change in defecation frequency; normal stool quality/ quantity; no GI discomfort; healthy appetite associated with completion or near-completion of normal rations sufficient to maintain the cat’s MER | Increase or decrease in defecation frequency; poor stool quality; presence of blood in the stool; signs of GI discomfort; history of PU/PD; vomiting or diarrhea; decreased appetite with associated inability to maintain MER |

| Examine mucous membranes and skin color | Normal color | Jaundice; pale mucous membranes and/or skin. Ulceration and petechiae |

| Palpate abdomen (liver, bowel loops) | Normal abdomen/liver/ bowel loops | Pendulous abdomen; abnormal liver or bowel loop size/shape; signs of pain on palpation |

| Evaluate stool appearance and volume | Moist formed; no evidence of blood or increased mucus | Watery to loose; presence of blood or increased mucus; very dry stool in pellets |

| Fecal centrifugation flotation/smear | Negative | Positive for intestinal parasites |

| Serum biochemistry profile and CBC (see Table 1) | All values within reference interval for age | One or more values outside reference interval for age |

CBC = complete blood count; GI = gastrointestinal; MER = maintenance energy requirement; PD = polydipsia; PU = polyuria

Cardiac/respiratory health assessment

In a healthy older cat, it is not uncommon to auscultate a heart murmur even in the absence of underlying cardiac disease. Almost 60% of cats over the age of 9 years have an auscultated murmur. 39 The significance of the murmur, however, can only be determined by evaluating the remainder of the cardiovascular and physical examination in concert with the findings from additional diagnostics.

In a healthy older cat in a clinical setting, a heart rate between 140 and 240 bpm and without any additional gallop sounds would be considered within a normal range. There should be no jugular pulse present, and the heart should sound clear and not muffled. The femoral pulses should be equal in intensity on both hindlimbs, and pulse rate should be the same as the heart rate. BP may be slightly higher in older cats; however, systolic values should remain <150 mmHg to avoid risk of damage to target organs (eyes, brain, heart, kidneys).8,40

Wellness exams of older cats should include a general assessment and auscultation of the heart and lungs (Figure 10), palpation of the cardiac impulse and femoral pulse quality, assessment of mucous membrane color and evaluation for a jugular pulse (Tables 11 and 12). Assessment of systolic BP as well as palpation for a prominent thyroid nodule should also become part of the wellness exam in this population. In addition, historical information from the owner is vitally important, because many cats with cardiac disease will not show the ‘typical signs’ seen in dogs with heart disease – namely tachypnea, dyspnea, coughing or exercise intolerance. Feline patients with heart disease are more likely to have a change in demeanor noticed by the owner, such as changes in activity, becoming less social, hiding more and a decline in appetite.

Figure 10.

Auscultation of the heart and lungs should be incorporated into the routine wellness exam of older cats. Courtesy of Oxford Cat Clinic, UK/International Cat Care

Table 11.

Cardiac health evaluation

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy |

|---|---|---|

| Query owner: Changes in activity level or appetite? Changes in interaction with other pets and people? | Normal activity level, normal social activity, normal appetite | Lethargic, hiding, anorectic |

| Auscultate the heart and lungs | Normal heart rate for clinical scenario | Heart rate >240 bpm ± a heart murmur; muffled heart sounds, arrhythmia or gallop rhythm; heart rate <140 bpm (possible AV block or excessive vagal tone) |

| Assess jugular and peripheral pulses | Jugular vein distends when pressure is placed at thoracic inlet to occlude it, but quickly collapses when pressure is released. Femoral pulses should be palpated simultaneously, and quality should be easily identified and equal in intensity in non-obese, standing cat | Jugular vein collapses slowly when thoracic pressure is released or is distended without pressure applied to the thoracic inlet. Weak or uneven femoral pulse quality (may indicate poor cardiac output or thrombosis). Increased peripheral pulse quality may indicate hyperthyroidism, hypertension, anemia or volume overload (essentially any high output state) |

| Measure systolic BP | <150 mmHg | >150 mmHg |

| Assess mucous membrane color and CRT | Normal color; CRT <2 s | Blue or bluish-gray (cyanosis); pale (anemia, hypotension or pain); prolonged CRT (>2 s) |

bpm = beats per minute; AV = atrioventricular; CRT = capillary refill time; BP = blood pressure

Table 12.

Respiratory health evaluation

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy |

|---|---|---|

| Query owner: Changes in activity level or appetite? Changes in interaction with other pets and people? Any coughing/wheezing? | Normal activity level, normal social activity, normal appetite, no coughing or wheezing | Cough, dyspnea, wheezing, lethargy, inappetence |

| Auscultate the lungs | Normal breath sounds and rate (24–36/min) | Increased breath sounds (crackles, wheezes); decreased breath sounds (pleural fluid line); abnormal sounds (rales, pops, snaps, rhonchi); abnormal rate (tachypneic for given situation) |

| Examine the thorax | Eupneic; thorax not distended; sounds not muffled | Abnormal respiratory effort and rate; cat becomes tachypneic with repositioning and prefers to stand or lie sternally |

| Assess mucous membrane color and CRT | Normal color; CRT <2 s | Blue or bluish-gray (cyanosis); prolonged CRT (>2 s) |

CRT = capillary refill time

Renal/urinary health assessment

Renal and urinary tract health should be assessed during routine wellness examinations of aging cats. Many aging cats have underlying renal changes and will require longitudinal, serial evaluations to evaluate renal function over time and monitor for early indicators of kidney disease.

A recent study documented risk factors associated with the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD) through the evaluation of medical records of cats (median age 14.2 years; range 3.0–22.8 years) up to 12 months before diagnosis, compared with age-matched (14.2 years; 3.1–23 years) controls. 41 Clinical factors associated with an increased risk of CKD included weight loss, thin body condition, dehydration, periodontal disease, cystitis and having undergone anesthesia. Clinical diagnoses of hypertension and undifferentiated heart disease were also overrepresented in the CKD group. At the time of diagnosis, clinical signs reported by the owner and observed by the attending veterinarian included polyuria or polydipsia, decline in appetite, vomiting, decline in activity and halitosis. The median weight loss in CKD cats was 10.8%, compared with a median weight loss of 2.1% in the control group. This finding demonstrated that although reduced body weight may be common in aging cat populations, the presence of significant weight loss is a risk factor that should be closely monitored in aging cats. The decline in appetite reported at the time of diagnosis highlights the importance of taking complete dietary histories and may provide an early signal of underlying kidney disease before significant loss of weight and body condition becomes apparent.

Routine evaluations to assess renal and urinary health should include BP, CBC, serum biochemistry profile and urinalysis. History, including dietary and appetite changes, water consumption and urinary habits, should be collected from owners (Table 13). In addition to the aforementioned reduction in appetite, polyuria/polydipsia is a key clinical sign reported by owners that would indicate possible early CKD, while dysuria, hematuria or pollakiuria could indicate lower urinary tract disease. 41 Renal function can be evaluated using serum biochemistry profile screening and urinalysis, but these tests may be insensitive for detecting early underlying renal disease. Serial assessment of serum creatinine is better than a single assessment because it helps to identify declining renal function when creatinine values may be within the reference interval. For example, a single creatinine concentration of 1.4 mg/dl (123.8 µmol/l) may indicate normal function based on standard reference intervals, but a significant change from previous results could suggest a decline in renal function. Serum creatinine should be interpreted in conjunction with BCS and MCS, as declining muscle mass results in lower serum creatinine values.

Table 13.

Renal/urinary health evaluation

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy |

|---|---|---|

| Query owner: Changes in appetite, water intake, urinary habits? | Normal/good appetite, no changes in water intake or frequency of urination | Reduced appetite, increased water intake, increased frequency of urination, dysuria, hematuria, pollakiuria |

| Physical exam, abdominal palpation (size, shape of kidneys, bladder) | Normal, with slight decrease in skin elasticity and muscle mass | Thin body condition, dehydration, pale mucous membranes, abnormal kidney size or shape; bladder mass |

| Measure systolic BP | <150 mmHg | >150 mmHg |

| CBC | Normal RBC count, RBC morphology, mean cell hemoglobin concentration and mean cell volume | Non-regenerative anemia; microcytic, hypochromic erythrocytes |

| Complete serum biochemistry profile: BUN and creatinine, serum electrolytes and acid–base status | Normal BUN and creatinine values (compare serum creatinine with previous values to detect declining renal function, even if values are within the reference interval, and interpret in conjunction with MCS); normal serum electrolytes; normal acid–base status | Elevated BUN and creatinine values or increases in serum creatinine from previous assessment; abnormal electrolytes and/or acid–base status |

| Urinalysis (color and turbidity, odor, USG, urine dipstick [glucose, bilirubin, ketones, occult blood, protein, pH], urine sediment) | Normal urinalysis results with USG ⩾1.040 | Abnormal urinalysis: isosthenuria or poor urine concentration in the presence of azotemia (compare with previous values to detect declining urine concentrating ability); proteinuria (follow up with UPC if present); changes indicative of UTI (follow up with urine culture if present) |

BP = blood pressure; BUN = blood urea nitrogen; CBC = complete blood count; RBC = red blood cell; UPC = urine protein:creatinine ratio; USG = urine specific gravity; MCS = muscle condition score; UTI = urinary tract infection

Because renal compensatory hypertrophy masks underlying renal changes until they have reached an advanced stage, minimizing risk factors that could contribute to a decline in renal function is important in aging cats. Precautions include avoiding potentially nephrotoxic drugs (such as aminoglycosides and injudicious use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), preventing dehydration and renal hypotension, especially during anesthesia, and controlling proteinuria and hypertension if present. 42

Endocrine system health assessment

Health evaluation of an aged cat should include eliciting information from the owner regarding activity levels, changes in demeanor (indifference vs agitation), urine volume and frequency of urination, and stability of appetite and body weight (Table 14). Constipation may be noted and may indicate dehydration associated with polyuria or decreased water intake. Changes in vocalization (in particular, night-time vocalization) may be indicative of:

Table 14.

Endocrine health evaluation

| Assessment tool | Healthy | Not healthy |

|---|---|---|

| Query owner: Changes in activity, demeanor (agitation), vocalization, appetite, weight, coat, volume or frequency of urination? | Normal, no significant changes observed | Hyperactive or lethargic; night-time yowling; increased appetite; weight loss; poor coat quality; PU/PD; hard, dry stool |

| Physical examination including BP and thyroid palpation (palpation of the ventral neck) | Normal, with slight decrease in skin elasticity and muscle mass | Dry, dull hair coat; reduced skin elasticity; weight loss or gain; muscle wasting; lax carpi or tarsi; firm feces in descending colon; readily palpable mass in ventral cervical (neck) region, suggesting enlarged thyroid or asymmetrical thyroid lobes; persistently elevated BP (>150 mmHg); tachycardia |

| CBC and serum biochemistry profile | Normal based on ageappropriate reference intervals | Stress leukon (mature neutrophilia and lymphopenia); mild non-regenerative anemia; increased SAP, ALT and glucose; altered electrolytes (hypokalemia) |

| Fructosamine | Normal | Elevated, although in cats with concurrent hyperthyroidism and diabetes, fructosamine may not be elevated |

| T4 | Normal | Total T4 elevation; when T4 is in high normal reference interval but cat appears hyperthyroid, measure free T4 by equilibrium dialysis |

| Urinalysis | Normal | Glucosuria, USG <1.040 |

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; BP = blood pressure; CBC = complete blood count; PD = polydipsia; PU = polyuria; SAP = serum alkaline phosphatase; T4 = thyroxine; USG = urine specific gravity

Agitation associated with hyperthyroidism;

Agitation associated with hypertension;

Disorientation because of a decline in special senses;

Pain;

Cognitive dysfunction.

Initial observation of the patient before performing the physical examination may provide important clues. A poor coat, weight loss, muscle wasting or laxity of the hocks or carpi may be indicative of poor glycemic control, whereas a poor coat, loss of weight and muscle mass, along with tachycardia and agitation, may suggest hyperthyroidism.

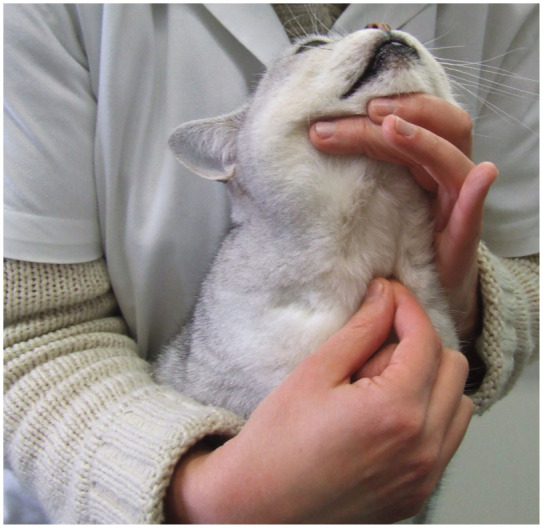

On physical examination, thyroid mass palpation (palpation of the ventral neck) should be performed on every cat (Figure 11).8,43 Free T4 is not a screening test and should be reserved for cases of equivocal hyperthyroidism. Although it may not be possible to draw a reliable conclusion on the functional status of the thyroid based on its size, the likelihood of hyperthyroidism increases with increasing size of the gland.8,43–45 It has also been shown that asymmetry of the thyroid gland usually reflects thyroid disease.43–45 It is important to remember, however, that goiter may be present from non-functional thyroid disease or enlargement of the parathyroid glands or other ventral cervical structures, 46 including an abscess or foreign body granuloma.

Figure 11.

Thyroid palpation should be performed on every cat. The likelihood of thyroid disease increases with increasing size and with asymmetry of the gland. Courtesy of Dominique Paepe, Ghent University

As mentioned earlier (see ‘general health assessment’ section), BP should be routinely assessed in all older cats, 8 as hypertension may be an early marker of disease and/or affect disease progression. Hypertension is a feature of multiple endocrine disorders in cats (eg, hyperthyroidism, hyperaldosteronism), and should be differentiated from other possible etiologies (eg, CKD).

Stress may result in both hyperglycemia and resultant glucosuria. In order to differentiate between stress and diabetes mellitus when these abnormalities are present, serum fructosamine should be measured to verify the existence and determine the duration of inadequate glycemic control, supporting a diagnosis of diabetes. This test may be added after lab results have been received or requested immediately if the history and clinical findings prompt an in-house blood glucose and urine glucose evaluation. One confounding factor that should be considered is that fructosamine levels may be suppressed because hyperthyroidism is a hypermetabolic state. This can make it more difficult to diagnose diabetes in a cat with both conditions.

Immune system health assessment

Determination of immune system function in aged cats can be challenging. Clinicians are often faced with the difficulty of differentiating age-related alterations in immune function from changes secondary to concurrent disease.

The aged cat’s overall health status is often a good reflection of its immune health. Changes in white blood cell counts may be appreciated with sequential CBC evaluations over the patient’s lifetime. These normal changes in immune response of an aged cat (immunosenescence and inflammaging – see accompanying article) could predispose the cat to conditions associated with infectious organisms and/or inflammation within the body. Therefore, these factors sound be considered during routine evaluations and screenings of senior cats.

Key points

As in humans, many of the changes that occur with aging in cats are not considered pathologic and do not negatively affect overall wellness or quality of life. However, ruling out disease is essential when attempting to determine whether an aged cat can be considered ‘healthy’.

Health examinations of aged cats should assess body weight, BCS and MCS, mobility and muscle strength, skin and coat quality, oral and gingival health, visual acuity, hearing and olfactory function, and general behavior and cognitive status. In addition, clinical changes in the GI, immune, hepatic, cardiac, respiratory, renal and endocrine body systems should be evaluated.

CBC, complete serum biochemistry profile, urinalysis, total T4 and BP should be measured as part of every aged cat wellness examination.

Using parameters consistent with current thinking on healthy aging in people, this review outlines a definition of healthy aged cats that can be identified based on an overall healthy assessment of measures, body systems and behavioral/cognitive function. A primary goal is to use these criteria as a rigorous, data-based standard for clinical studies of aging in cats.

By fully understanding healthy aging, veterinarians and pet owners alike may be able to reduce risk factors for developing certain diseases in aging cats.

Veterinarians are a primary education resource for cat caregivers and play a central role in helping owners to best care for their aged cats.

Possessing a clear understanding of the normal and abnormal changes that are associated with aging in cats can help practitioners make decisions regarding medical management, nutritional assessment and feeding interventions, and additional testing procedures for their aged patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to those colleagues who have loaned images for this review.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by Procter & Gamble Pet Care, Mason, Ohio, USA.

JB, SC, AHE, DFH, BDXL and MS all were paid for their contributions by Procter & Gamble Pet Care. LD, EAF, AL, SP and AKS have financial and personal interest in the Procter & Gamble Company; LD and EAF were employees of the company at the time of coauthoring this review. SP is an employee of Royal Canin, Mars Incorporated.

References

- 1. Minnesota Department of Health, Community and Family Health Division, Office of Rural Health and Primary Care and Office of Public Health Practice. Creating healthy communities for an aging population: a report of a Joint Rural Health Advisory Committee and State Community Health Services Advisory ComMittee Work Group. http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/orhpc/pubs/healthyaging/hareportnofs.pdf (2006, accessed May 20, 2015).

- 2. AGE – European older People’s Platform, EuroHealthNet, World Health organization et al. Healthy ageing – a challenge for Europe. http://www.healthyageing.eu/sites/www.healthyageing.eu/files/resources/Healthy%20Ageing%20-%20A%20Challenge%20for%20Europe.pdf. (2006, accessed May 20, 2015).

- 3. Gilmer DF, Aldwin CM. Health, illness, and optimal ageing: biological and psychosocial perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: a comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14: 6–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vogt AH, Rodan I, Brown M, et al. AAFP-AAHA: Feline life stage guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997; 37: 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pitari J, Rodan I, Beekman G, et al. American Association of Feline Practitioners: Senior care guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 763–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paepe D, Verjans G, Duchateau L, et al. Routine health screening: findings in apparently healthy middle-aged and old cats. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 8–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Landsberg GM, Denenberg S, Araujo JA. Cognitive dysfunction in cats: a syndrome we used to dismiss as old age. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 837–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carney HC, Sadek TP, Curtis TM, et al. AAFP and ISFM guidelines for diagnosing and solving house-soiling behavior in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2014; 16: 579–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gunn-Moore D, Moffat K, Christie LA, et al. Cognitive dysfunction and the neurobiology of ageing in cats. J Small Anim Pract 2007; 48: 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Landsberg GM, Nichol J, Araujo JA. Cognitive dysfunction syndrome: a disease of canine and feline brain aging. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2012; 42: 749–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gunn-Moore DA. Cognitive dysfunction in cats: clinical assessment and management. Top Companion Anim Med 2011; 26: 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baral RM, Little SE. Endocrinology. In: Little SE. (ed). The cat: clinical medicine and management. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2012, pp 547–642. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moriello KA, Klei TR, Stiller D, et al. Tumors of the skin in cats. http://www.merckmanuals.com/pethealth/cat_disorders_and_diseases/skin_disorders_of_cats/tumors_of_the_skin_in_cats.html (2011, accessed May 20, 2015).

- 16. Moriello KA. Diseases of the skin. In: Sherding RG. The cat: diseases and clinical management. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1994, pp 1907–1968. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Appleton DJ, Rand JS, Sunvold GD. Feline obesity: pathogenesis and implications for the risk of diabetes. 2000 Iams nutrition symposium proceedings: recent advances in canine and feline nutrition. Vol 3. Wilmington, OH: Orange Frazer Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cupp CJ, Kerr WW, Jean-Philippe C, et al. The role of nutritional interventions in the longevity and maintenance of long-term health in aging cats. Intern J Appl Res Vet Med 2008; 6: 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cupp C, Perez-Camargo G, Patil A, et al. Long-term food consumption and body weight changes in a controlled population of geriatric cats [abstract]. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2004; 26 Suppl 2A: 60. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cupp CJ, Kerr WW. Effect of diet and body composition on life span in aging cats. Proceedings of the Nestle Purina companion animal nutrition summit, focus on Gerontology; 2010 March 26–27; Clearwater Beach, Florida, 2010, pp 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dora-Rose VP, Scarlett JM. Mortality rates and causes of death among emaciated cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000; 216: 347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gulsvik AK, Thelle DS, Mowe M, et al. Increased mortality in the slim elderly: a 42 years follow-up study in a general population. Eur J Epidemiol 2009; 24: 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benito J, Hansen B, Depuy V, et al. Feline musculoskeletal pain index: responsiveness and testing of criterion validity. J Vet Intern Med 2013; 27: 474–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Benito J, Gruen ME, Thomson A, et al. Owner-assessed indices of quality of life in cats and the relationship to the presence of degenerative joint disease. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 14: 863–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gruen M, Griffith E, Thomson A, et al. Detection of clinically relevant pain relief in cats with degenerative joint disease associated pain. J Vet Intern Med 2014; 28: 346–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Michel KE, Anderson W, Cupp C, et al. Correlation of a feline muscle mass score with body composition determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Br J Nutr 2011; 106 Suppl 1: S57–S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lascelles BD, Henry JB, 3rd, Brown J, et al. Cross-sectional study of the prevalence of radiographic degenerative joint disease in domesticated cats. Vet Surg 2010; 39: 535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Slingerland LI, Hazewinkel HA, Meij BP, et al. Cross-sectional study of the prevalence and clinical features of osteoarthritis in 100 cats. Vet J 2011; 187: 304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lascelles BD, Dong YH, Marcellin-Little DJ, et al. Relationship of orthopedic examination, goniometric measurements, and radiographic signs of degenerative joint disease in cats. BMC Vet Res 2012; 8: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jaeger GH, Marcellin-Little DJ, Depuy V, et al. Validity of goniometric joint measurements in cats. Am J Vet Res 2007; 68: 822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guillot M, Moreau M, Heit M, et al. Characterization of osteoarthritis in cats and meloxicam efficacy using objective chronic pain evaluation tools. Vet J 2013; 196: 360–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Benito J, Depuy V, Hardie E, et al. Reliability and discriminatory testing of a client-based metrology instrument, feline musculoskeletal pain index (FMPI) for the evaluation of degenerative joint disease-associated pain in cats. Vet J 2013; 196: 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zamprogno H, Hansen BD, Bondell HD, et al. Item generation and design testing of a questionnaire to assess degenerative joint disease-associated pain in cats. Am J Vet Res 2010; 71: 1417–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brantman KR, Davidson HJ. Blindness. In: Norsworthy GD, Grace SF, Crystal MA, et al. (eds). The feline patient. Ames, OH: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brantman KR, Davidson HJ. Retinal disease. In: Norsworthy GD, Grace SF, Crystal MA, et al. (eds). The feline patient. Ames, OH: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp 462–465. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ryugo DK, Menotti-Raymond M. Feline deafness. In: Bradley NL, Cole LK. (eds). VCNA otology and otic disease. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2012, pp 1179–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harvey CE. Feline dentistry. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1992; 22: 1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bellows JE. Feline dentistry. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell, 2010, p 67. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Payne JR, Brodbelt DC, Fuentes VL. Cardiomyopathy prevalence in 780 apparently healthy cats in rehoming centers (the CatScan study). J Vet Cardiol 2015; 17: S244–S257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brown S, Atkins C, Bagley R, et al. Guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and management of systemic hypertension in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med 2007; 21: 542–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Greene JP, Lefebvre SL, Wang M, et al. Risk factors associated with the development of chronic kidney disease in cats evaluated at primary care veterinary hospitals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2014; 244: 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bartges JW. Chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2012; 42: 669–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Paepe D, Smets P, van Hoek I, et al. Within- and between-examiner agreement for two thyroid palpation techniques in healthy and hyperthyroid cats. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 558–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boretti FS, Sieber-Ruckstuhl NS, Gerber B, et al. Thyroid enlargement and its relationship to clinicopathological parameters and T4 status in suspected hyperthyroid cats. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 286–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Norsworthy GD, Adams VJ, McElhaney MR, et al. Relationship between semi-quantitative thyroid palpation and total thyroxine concentration in cats with and without hyperthyroidism. J Feline Med Surg 2002; 4: 139–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Norsworthy GD, Adams VJ, McElhaney MR, et al. Palpable thyroid and parathyroid nodules in asymptomatic cats. J Feline Med Surg 2002; 4: 145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]