Abstract

Objective:

MLH1 loss due to MLH1 methylation, detected during Lynch Syndrome screening, is one of the most common molecular changes in endometrial cancer. It is well-established that environmental influences such as nutritional state can impact gene methylation, both in the germline and in a tumor. In colorectal cancer and other cancer types, aging is associated with changes in gene methylation. The objective of this study was to determine if there was an association between aging or body mass index on MLH1 methylation in sporadic endometrial cancer.

Methods:

A retrospective review of endometrial cancer patients was performed. Tumors were screened for Lynch Syndrome via immunohistochemistry, with MLH1 methylation analysis performed when there was loss of MLH1 expression. Clinical information was abstracted from the medical record.

Results:

There were 114 patients with mismatch repair deficient tumors associated with MLH1 methylation, and 349 with mismatch repair proficient tumors. Patients with mismatch repair deficient tumors were older than those whose tumors were proficient. Mismatch repair deficient tumors had higher incidence of lymphatic/vascular space invasion. When stratified by endometrioid grade, associations with body mass index and age became apparent. Patients with endometrioid grades 1 and 2 tumors and somatic mismatch repair deficiency were significantly older, but body mass index was comparable with that of the mismatch repair intact group. For endometrioid grade 3, patient age did not significantly vary comparing the somatic mismatch repair deficient group to the mismatch repair intact group. In contrast, body mass index was significantly higher in the patients with grade 3 tumors with somatic mismatch repair deficiency.

Conclusion:

The relationship of MLH1 methylated endometrial cancer with age and body mass index is complex and somewhat dependent on tumor grade. As body mass index is modifiable, it is possible that weight loss induces a “molecular switch” to alter the histologic characteristics of an endometrial cancer.

INTRODUCTION

One of the most common molecular alterations in endometrial cancer is mismatch repair deficiency secondary to MLH1 methylation and loss of MLH1 protein, occurring in 15–20% of patients, especially those with endometrioid tumors.(1, 2)MLH loss secondary to MLH1 gene methylation (somatic mismatch repair deficiency) is frequently detected clinically, as it has become routine practice to screen all endometrial cancers for the hereditary cancer syndrome Lynch Syndrome. This screening is performed using immunohistochemistry for mismatch repair proteins and/or PCR-based microsatellite instability analysis, with MLH1 methylation analysis employed for endometrial cancers with MLH1 loss by immunohistochemistry. Lynch Syndrome is due to a germline mutation in mismatch repair genes, most commonly MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2.

In addition to identifying women at-risk for Lynch Syndrome, mismatch repair deficiency also has important implications for endometrial cancer patient survival. One large Australian study found that patients with somatic mismatch repair deficient endometrioid endometrial cancers had shorter endometrial cancer-specific survival compared with those with MMR proficient tumors.(3) In another study of patients with advanced stage endometrioid endometrial cancers, patients with somatic mismatch repair deficient tumors were more likely to recur compared to patients with mismatch repair proficient tumors.(4)

Mismatch deficient tumors are often considered a homogenous group irrespective of the mechanism of the deficiency.(5, 6) Even pivotal clinical trials such as the Phase II trial of pembrolizumab in patients with mismatch repair deficient tumors did not stratify the response by type of mismatch repair deficiency.(7) It is noteworthy that in that trial, 48% of patients enrolled had a known germline mismatch repair deficiency.(7) This, however, is not reflective of the epidemiology of endometrial cancer patients. The proportion of patients presenting with colorectal or endometrial cancer who have Lynch Syndrome is close to 3%, with the majority of mismatch repair deficient tumors secondary to MLH1 methylation.(8) Data are becoming increasingly available to support the idea that somatic and germline mismatch repair deficient endometrial cancers are unique entities.(8, 9) Survival outcomes(3) and tumor immune microenvironment (10, 11) may be different between these two populations. Studies also indicate differences in survival outcomes between somatic mismatch repair deficient endometrial cancers and their mismatch repair proficient counterparts, suggesting that these tumors exhibit distinct biology.(3, 4, 12)

It has been reported by a few groups that endometrial cancer patients, especially younger ones, with mismatch repair deficiency consistent with Lynch Syndrome (i.e., germline mutation of a mismatch repair gene, immunohistochemical loss of MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2, or MLH1 loss in the absence of MLH1 gene methylation) have significantly lower BMI compared to patients with mismatch repair intact, sporadic endometrial cancer.(13, 14) Such a relationship with lower BMI has not been reported in other studies employing a population-based methodology for detecting mismatch repair defects in patients of all ages. (15, 16) Thus, the relationship between endometrial cancer, obesity, age, and mismatch repair deficiency may be complex. Given the known causal relationship between obesity and methylation of germline and adipose tissue DNA, we hypothesized that higher patient BMI is associated with endometrial cancer MLH1 gene methylation. The objective of this study was to compare clinical and pathological characteristics of patients with somatic mismatch repair deficient endometrial cancers (MLH1 immunohistochemical loss secondary to MLH1 methylation) to patients with mismatch repair proficient endometrial cancers.

METHODS

Patient population

This study was approved by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (Protocol LAB01–718), and the requirement for written informed consent was waived by the IRB. In this retrospective cohort study, all patients with endometrial cancer who underwent clinical evaluation for mismatch deficiency at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center from January 2013 to March 2017 were considered for inclusion. Clinical and pathologic variables were extracted from pathology reports and the electronic medical record. Light microscopic confirmation of endometrial cancer histology and mismatch repair protein testing were performed by a gynecologic pathologist (RRB) as a component of screening for Lynch Syndrome according to methodology previously described.(16)

Determination of mismatch repair status

Immunohistochemistry of mismatch repair proteins was performed using standard techniques for MLH1 (G168-15 1:25; BD Biosciences Pharmingen), MSH2 (FE11, 1:100; Calbiochem), MSH6 (44, 1:300; BD Biosciences Pharmingen), and PMS2 (Alb-4, 1:125; BD Biosciences Pharmingen). Immunohistochemistry was scored as mismatch repair protein proficient or deficient using light microscopic examination. Endometrial cancers having intact expression of all four mismatch repair proteins were considered mismatch repair proficient. Complete absence of mismatch repair protein expression was required for a case to be designated as mismatch repair deficient. Stromal cells adjacent to the tumor served as an internal positive control. Tumors exhibiting loss of MLH1 and PMS2 were analyzed for MLH1 methylation in a clinical laboratory according to our previously described methodology.(16) Tumors with loss of MLH1 and PMS2 with presence of MLH1 methylation were considered somatic mismatch repair deficient.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were performed to describe the demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of the study population. Characteristics were then compared across the two mismatch repair groups. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges and compared using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. All analyses were performed using Stata version 16.1 (College Station, TX). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Post-hoc power analyses were performed to estimate the smallest patient numbers needed for optimal interpretation of the data. Assuming a two-sided test with alpha = 0.05, and power = 0.8, the required sample size was calculated for variables of interest based of if they’re continuous or categorical variables. In accordance with the journal’s guidelines, we will provide our data for independent analysis by a selected team by the Editorial Team for the purposes of additional data analysis or for the reproducibility of this study in other centers if such is requested.

RESULTS

There were 463 patients included in the analysis, 349 (75%) of whom had tumors that were mismatch repair proficient, and 114 (25%) whose tumors were somatic mismatch repair deficient (Table S1). Patients whose tumors had somatic mismatch repair deficiency were significantly older than patients whose tumors were mismatch repair proficient (65 versus 59 years, p<0.01). Additionally, the tumors that had somatic mismatch repair deficiency had a higher frequency of lymphatic/vascular space invasion (42% versus 27%, p<0.01). Similar to prior studies,(2, 17) the vast majority of the somatic mismatch repair deficient tumors were endometrioid histology (Table S1). There were no statistically significant differences in other clinical or pathological characteristics between the groups (Table S1).

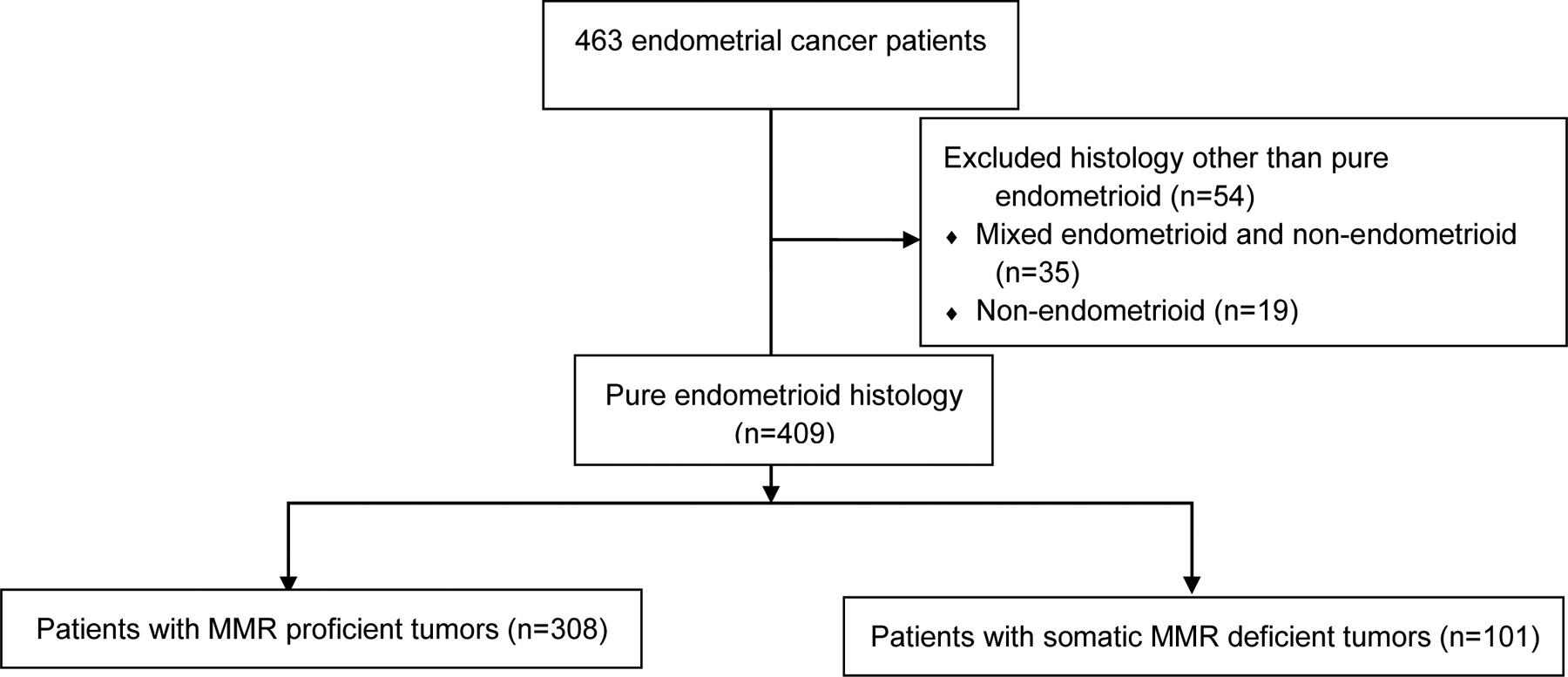

The analysis was then limited to the 409 patients (88%) with endometrioid tumors (Figure 1 and Table 1). Among endometrioid tumors, somatic mismatch repair deficient tumors were more likely to be high grade (grade 3) (14% versus 5%, p<0.01), be FIGO stage III or IV (23% versus 12%, p<0.01), and were more likely to demonstrate lymphatic/vascular space invasion (40% versus 25%, p=0.01) (Table 1). Given the distinct biology, clinical features, and pathological features of low grade (grade 1 or 2) and high grade (grade 3) endometrial endometrioid carcinoma,(18, 19) we then further investigated clinicopathologic differences within each of these subsets separately.

Figure 1.

Flow chart summarizing tumor histology and tumor mismatch repair status of endometrial cancer patients included in this study. MMR, mismatch repair.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with endometrioid endometrial tumors

| MMR proficient (N=308) |

Somatic MMR deficient (N=101) |

p valued | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (IQR) | 58 (15) | 65 (11) | <0.01 |

| Median BMI in kg/m2 (IQR) | 34 (14) | 35 (12) | 0.79 |

| Race, n (%)a | 0.37 | ||

| White | 213 (71) | 74 (73) | |

| Hispanic | 33 (11) | 7 (7) | |

| Black | 21 (7) | 11 (11) | |

| Asian | 17 (6) | 4 (4) | |

| Native Hawaiian | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 14 (5) | 5 (5) | |

| Grade, n (%) | 0.04 | ||

| Low (1 and 2) | 292 (95) () | 87 (86) () | |

| High (3) | 16 (5) | 14 (14) | |

| FIGO stage, n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| Stage I/II | 271 (88) | 78 (77) | |

| Stage III/IV | 37 (12) | 23 (23) | |

| Myometrial invasion, n (%)b | 0.35 | ||

| Superficial | 235 (77) | 70 (72) | |

| Deep | 71 (23) | 27 (28) | |

| LVSI, n (%)c | <0.01 | ||

| Absent | 225 (75) | 57 (60) | |

| Present | 75 (25) | 38 (40) |

MMR, mismatch repair; BMI, body mass index; LVSI, lymphatic/vascular space invasion; IQR, Interquartile range.

Nine patients had missing information about race

Six patients had missing information about myometrial invasion

Fourteen patients had missing information about lymphatic/vascular invasion

P-values less than 0.05 in bold are considered statistically significant

Patients with low grade, somatic mismatch repair deficient endometrioid tumors were significantly older at diagnosis (65 versus 57 years, p<0.01) than patients with low grade, mismatch repair proficient endometrioid tumors. Low grade, mismatch repair deficient tumors also had a higher frequency of lymphatic/vascular space invasion (36% versus 24%, p<0.01). There were no other significant differences between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with low grade (grade 1 or 2) endometrioid endometrial tumors

| MMR proficient (N=292) |

Somatic MMR deficient (N=87) |

p valued | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (IQR) | 58 (15) | 65 (10) | <0.01 |

| Median BMI in kg/m2 (IQR) | 35 (14) | 34 (13) | 0.59 |

| Race, n (%)a | 0.61 | ||

| White | 203 (71) | 63 (72) | |

| Hispanic | 30 (11) | 6 (7) | |

| Black | 21 (7) | 9 (10) | |

| Asian | 16 (6) | 4 (5) | |

| Native Hawaiian | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 13 (5) | 5 (6) | |

| FIGO stage, n (%) | 0.1 | ||

| Stage I/II | 259 (89) | 71 (82) | |

| Stage III/IV | 33 (11) | 16 (18) | |

| Myometrial invasion, n (%)b | 0.53 | ||

| < 50% | 227 (78) | 62 (75) | |

| ≥ 50% | 64 (22) | 21 (25) | |

| LVSI, n (%)c | 0.03 | ||

| Absent | 217 (76) | 52 (64) | |

| Present | 67 (24) | 29 (36) |

MMR, mismatch repair; BMI, body mass index; LVSI, lymphatic/vascular space invasion; IQR, Interquartile range.

Eight patients had missing information about race

Five patients had missing information about myometrial invasion

Fourteen patients had missing information about lymphatic/vascular invasion

P-values less than 0.05 in bold are considered statistically significant

In the high grade endometrial endometrioid cancer cohort, there was no significant difference in age at diagnosis between the two groups. However, patients with grade 3 somatic mismatch repair deficient endometrioid cancers had significantly higher BMI (37 versus 29 kg/m2, p=0.01) than patients with mismatch repair proficient, grade 3 tumors. No other significant differences in clinical or pathological characteristics were identified (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with high grade (grade 3) endometrioid endometrial tumors

| MMR proficient (N=16) |

Somatic MMR deficient (N=14) |

p valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (IQR) | 59 (16) | 58 (12) | 0.83 |

| Median BMI in kg/m2 (IQR) | 29 (8) | 37 (10) | 0.01 |

| Race, n (%)a | 0.38 | ||

| White | 10 (66) | 11 (79) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (20) | 1 (7) | |

| Black | 0 (0) | 2 (14) | |

| Asian | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| Native Hawaiian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| FIGO stage, n (%) | 0.16 | ||

| Early | 12 (75) | 7 (50) | |

| Late | 4 (25) | 7 (50) | |

| Myometrial invasion, n (%)b | 0.84 | ||

| Superficial | 8 (53) | 8 (57) | |

| Deep | 7 (47) | 6 (43) | |

| LVSI, n (%) | 0.43 | ||

| Absent | 8 (50) | 5 (36) | |

| Present | 8 (50) | 9 (64) |

MMR, mismatch repair; BMI, body mass index; LVSI, lymphatic/vascular space invasion; IQR, Interquartile range.

One patient had missing information about race

One patients had missing information about myometrial invasion

P-values less than 0.05 in bold are considered statistically significant

Although our study was not specifically powered to examine for racial disparities due to the relatively small number of Black patients in our population (Table 1), an exploratory analysis evaluating the differences in clinicopathologic features after stratifying by race and somatic mismatch repair status was included (Table 4). No significant differences were identified.

Table 4.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with endometrioid endometrial tumors, stratified by race

| MMR proficient (N=234) |

Somatic MMR deficient (N=85) |

p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White (N=213) |

Black (N=21) |

Non-Hispanic White (N=74) |

Black (N=11) |

||

| Median age in years (IQR) | 59 (12) | 57 (15) | 65 (12) | 62 (13) | 0.33 |

| Median BMI in kg/m2 (IQR) | 35 (14) | 33 (12) | 35 (12) | 37 (12) | 0.95 |

| Grade, n (%) | 0.29 | ||||

| Low (1 and 2) | 203 (95) | 21 (100) | 63 (85) | 9 (82) | |

| High (3) | 10 (5) | 0 (0) | 11 (15) | 2 (18) | |

| FIGO stage, n (%) | 0.83 | ||||

| Stage I/II | 187 (88) | 18 (86) | 56 (76) | 8 (73) | |

| Stage III/IV | 26 (12) | 3 (14) | 18 (24) | 3 (27) | |

| Myometrial invasion, n (%)a | 0.47 | ||||

| Superficial | 161 (76) | 16 (76) | 49 (69) | 9 (90) | |

| Deep | 50 (24) | 5 (24) | 22 (31) | 1 (10) | |

| LVSI, n (%)b | 0.84 | ||||

| Absent | 151 (73) | 16 (76) | 39 (57) | 7 (70) | |

| Present | 56 (27) | 5 (24) | 30 (43) | 3 (30) | |

MMR, mismatch repair; BMI, body mass index; LVSI, lymphatic/vascular space invasion; IQR, Interquartile range.

Six patients had missing information about myometrial invasion

Twelve patients had missing information about lymphatic/vascular invasion

DISCUSSION

Summary of Main Results

These results suggest that the consideration of possible interrelationships between patient factors with endometrial cancer molecular features, such as somatic mismatch repair deficiency (MLH1 loss due to MLH1 gene methylation), are complex. When this large cohort of 463 endometrial cancer patients was considered as one group, limited relationships were found between somatic mismatch repair deficiency and the pathological or clinical variables examined. However, when stratified by endometrioid grade, interesting associations with BMI and age were revealed. Patients with endometrioid grades 1 and 2 cancers with somatic mismatch repair deficiency were significantly older, but body mass index was comparable with that of the mismatch repair proficient group. For patients with endometrioid grade 3 cancers, patient age did not significantly differ between the two mismatch repair groups. In contrast, BMI was significantly higher in the patients with grade 3 somatic mismatch repair deficient tumors. Our study was not powered to adequately examine these relationships by patient race. Given the endometrial cancer survival disparity Black patients suffer,(20) a preliminary analysis of the Black patients compared to the Non-Hispanic White patients was performed. We did not detect any clinical or pathological differences between these patient groups in both mismatch repair groups. These data need to be interpreted with caution, as Black patients represented only 9% of the mismatch repair intact group and 13% of the somatic mismatch repair deficient group (Table 4). We can preliminarily conclude that there are no significant clinical or pathological differences between Black patients and Non-Hispanic White patients in both the mismatch repair proficient and somatic mismatch repair deficient groups.

Results in the Context of Published Literature

Overweight and obesity are growing global health challenges especially in the United States. Increasing body mass index (BMI) is a risk factor for many chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and cancer. Obesity and conditions associated with metabolic syndrome, including type 2 diabetes and polycystic ovarian syndrome, are significant risk factors for developing endometrial cancer.(21–23)In a prospective analysis, the highest relative risk of death from a cancer for an obese individual was death from endometrial cancer (relative risk 6.25 for women with BMI of 40 or higher).(24) The molecular mechanisms responsible for this tight link between obesity and endometrial cancer are unknown. Hormones, particularly increased estrogenic stimulation in the obese state, and excessive inflammation are often cited as mechanisms, but neither have definitively been demonstrated to explain the association between obesity and endometrial cancer development.

DNA methylation is a key regulator of gene expression that is critical for normal development. Methylation of tumor suppressor genes is known to be important in certain cancers as well. Several large-scale genome-wide analyses have demonstrated that increasing BMI is associated with changes in DNA methylation, measured in the germline and normal adipose tissue.(25, 26) Furthermore, it was shown that the altered DNA methylation is predominantly a consequence of adiposity, rather than the cause.(25)

In the present study, our findings highlight the possible impact of patient-specific factors such as age and BMI on the epigenetic modification of MLH1 methylation in endometrial tumors. Most notably, when low grade and high grade endometrioid tumors were considered separately, differences were identified with respect to age and BMI. In low grade tumors, the presence of somatic MLH1 promoter hypermethylation was associated with increasing age whereas in high grade tumors, this methylation was associated with increasing BMI. As both these characteristics are patient factors, this suggests a role of the environment impacting tumor biology. The relationship between age and mismatch repair deficiency in endometrial cancer has been studied by McCourt et al., where the authors noted that in a subset of patients with MSI-high endometrial cancer, MLH1 promoter hypermethylation was associated with older age.(6) The relationship between BMI and mismatch repair deficiency, on the other hand, is less consistent. Prior work examining obesity and endometrial cancer demonstrated lower BMI in patients with MSI-high endometrial and colon cancers respectively.(6, 27) In contrast, Bruegl et al. found no statistically significant difference in BMI when comparing endometrial tumors with and without MLH1 promoter hypermethylation.(2) On initial analysis, our study, too, did not show a difference in BMI. It was not until the subset analysis by tumor grade that a difference was seen. Of particular interest to us was that in the high grade, but not low grade, tumors, patients with somatic mismatch repair deficient tumors had higher BMI than patients with proficient mismatch repair tumors. This effect is not likely driven by the presence of a TP53 gene mutation, as we have previously demonstrated no significant difference in mean BMI between patients with endometrioid-type endometrial cancers with a TP53 mutation versus those with TP53 wildtype cancers.(28) This finding adds some nuance to the well-known relationship between obesity and endometrial cancer. Although low grade tumors are more common, and thus more often associated with obesity,(24, 29) these data highlight that even among high grade endometrial cancers obesity may play an important role. This nuance is further illustrated in Burzawa et al.’s study exploring the role of insulin resistance in endometrial cancers. This study found no significant difference in FIGO stage or histologic grade of endometrial cancer when stratified by insulin resistance status.(30) Thus, obesity and associated metabolic changes, all potentially modifiable risk factors, may not only lead to the development of endometrial cancer in general, but may also alter the tumor biology of the cancer itself, possibly leading to worse patient outcomes. The complex and nuanced relationship between endometrial cancer and obesity can also be seen in melanoma. In patients with metastatic melanoma, obesity is associated with better progression-free and overall survival compared to patients with a normal BMI. This survival benefit of obesity was mainly seen in male patients treated with targeted or immune-based therapies. The survival benefit was not observed in obese women (31).

Significant weight loss via bariatric surgery has been associated with decreased risk of endometrial cancer.(32, 33). Endometrial cancer consistently has the strongest association between bariatric surgery and a decrease in the risk of cancer incidence.(34, 35) Our findings suggest that preventive medicine for endometrial cancer may not only potentially improve non-cancer related mortality for endometrial cancer patients with obesity,(36) but may also alter the tumor biology of higher risk endometrial cancers that we know are often associated with poorer oncologic outcomes.(37) Translational studies also point towards biologic changes in the endometrium after bariatric surgery, including resolution of atypical hyperplasia and downregulation of oncogenic biomarkers(38) and decreased inflammatory markers and upregulation of CD8+ immune cells.(39) Bariatric surgery can also result in hypermethylation and hypomethylation of genes, with resulting alterations in gene expression in a tissue-specific and gene-specific manner.(40, 41)

Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths of this study include the large number of endometrial cancer patients examined (n=463) who had mismatch repair immunohistochemistry and PCR-based MLH1 gene methylation analysis performed in a CLIA-approved clinical laboratory as a component of routine patient care. Another strength of the study was that the endometrial cancer patients were cared for by a small number of dedicated gynecologic oncologists from one group, so clinical and pathological data were accurate and readily accessible in the electronic medical record. A small group of gynecologic pathologists provided the diagnostic pathology work-up for each patient, and a gynecologic pathologist was responsible for interpretation of the mismatch repair immunohistochemistry, MLH1 methylation, and pathology review of the endometrial cancer histology. A limitation of this study is its retrospective design. Another limitation is that BMI measurements were not validated with other techniques, such as measurement of waist circumference or waist-to-hip ratio or more sophisticated measures of obesity, such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Patients in this study were seen at a large, tertiary care cancer center and may not be reflective of patients in other settings. These findings will need to be validated in other patient populations. Finally, there were insufficient Black patients for any definitive conclusions to be drawn regarding associations with somatic mismatch repair deficiency and increased BMI in this patient population. Our post hoc power analysis revealed that, in order to at minimum detect a difference of race between the two groups MMR proficient and somatic MMR deficient, we would need 2048 patients. Similarly, to detect a difference in age between the two groups in the high-grade endometrioid group, we would need 8038 patients, suggesting that a multi-institutional study may be necessary to answer these questions more completely.

Implications for Practice and Future Research

Future mechanistic studies and more comprehensive genomic analyses can further explore the biological differences of somatic mismatch repair deficient tumors compared to mismatch repair proficient tumors to better understand differences in drivers of tumor development between these two groups. Additionally, understanding the fluidity of these somatic changes after modification of environmental factors such as BMI could have relevant implications as well. While we are still far from fully understanding the complex interplay between the epigenome and the genome and how it relates to carcinogenesis, altogether these findings are encouraging as it opens the door for the possibility of environmental modifications such as weight loss to be used in tandem with therapeutic interventions. Such novel combinations could potentially transform how we approach each patient who presents with a new diagnosis of endometrial cancer, incorporating lifestyle interventions as regularly as we do new therapeutic modalities. Since the early 1990’s, annual mortality from ovarian cancer has gradually declined, while endometrial cancer annual mortality has steadily increased. This increase in endometrial cancer mortality is especially evident for Black women, such that their annual mortality is nearly twice the mortality in White patients despite a comparable endometrial cancer annual incidence rate.(20) Future studies of these novel treatment combinations should include adequate numbers of Black patients to better evaluate their efficacy in this patient population.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort

What is already known on this topic:

Somatic mismatch repair deficiency (MLH1 loss due to MLH1 gene methylation) and obesity are both tightly associated with endometrial cancer, but the relationship, if any, between these two variables is not well understood.

What this study adds:

The relationship between body mass index and endometrial cancer was complex and context dependent. In patients with grade 3 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, somatic mismatch repair deficiency was significantly associated with higher body mass index. This relationship is not observed in patients with grades 1 and 2 endometrial endometrioid carcinomas.

How this study might affect research, practice, or policy:

Body mass index is modifiable, and future research should evaluate whether weight loss could potentially induce a molecular switch to alter the histological characteristics of a somatic MMR deficient, high grade endometrial cancer, potentially altering the tumor biology and resulting in a better patient prognosis.

Funding:

NIH SPORE in Uterine Cancer NIH P50 CA098258 (RRB) and NIH Research Training Grant T32 CA101642 (KCK)

REFERENCES

- [1].Esteller M, Levine R, Baylin SB et al. MLH1 promoter hypermethylation is associated with the microsatellite instability phenotype in sporadic endometrial carcinomas. Oncogene. 1998;17: 2413–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bruegl AS, Djordjevic B, Urbauer DL et al. Utility of MLH1 methylation analysis in the clinical evaluation of Lynch Syndrome in women with endometrial cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20: 1655–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nagle CM, O’Mara TA, Tan Y et al. Endometrial cancer risk and survival by tumor MMR status. Journal of gynecologic oncology. 2018;29: e39–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cosgrove CM, Cohn DE, Hampel H et al. Epigenetic silencing of MLH1 in endometrial cancers is associated with larger tumor volume, increased rate of lymph node positivity and reduced recurrence-free survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146: 588–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Doghri R, Houcine Y, Boujelbène N et al. Mismatch Repair Deficiency in Endometrial Cancer: Immunohistochemistry Staining and Clinical Implications. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2019;27: 678–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].McCourt CK, Mutch DG, Gibb RK et al. Body mass index: relationship to clinical, pathologic and features of microsatellite instability in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104: 535–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357: 409–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ryan NAJ, McMahon R, Tobi S et al. The proportion of endometrial tumours associated with Lynch syndrome (PETALS): A prospective cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2020;17: e1003263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ramchander NC, Ryan NAJ, Walker TDJ et al. Distinct Immunological Landscapes Characterize Inherited and Sporadic Mismatch Repair Deficient Endometrial Cancer. Front Immunol. 2019;10: 3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].T Danley K, Schmitz K, Ghai R et al. A Durable Response to Pembrolizumab in a Patient with Uterine Serous Carcinoma and Lynch Syndrome due to the MSH6 Germline Mutation. Oncologist. 2021;26: 811–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pakish JB, Zhang Q, Chen Z et al. Immune microenvironment in microsatellite instable endometrial cancers: Hereditary or sporadic origin matters. Clin Cancer Res. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ávila M, Fellman BM, Broaddus RR. Tumor lymphocytic infiltration impacts recurrence in endometrioid-type endometrial carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lu KH, Schorge JO, Rodabaugh KJ et al. Prospective determination of prevalence of lynch syndrome in young women with endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25: 5158–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Joehlin-Price AS, Perrino CM, Stephens J et al. Mismatch repair protein expression in 1049 endometrial carcinomas, associations with body mass index, and other clinicopathologic variables. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133: 43–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bruegl AS, Djordjevic B, Batte B et al. Evaluation of Clinical Criteria for the Identification of Lynch Syndrome among Unselected Patients with Endometrial Cancer. Cancer Prevention Research. 2014;7: 686–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bruegl AS, Ring KL, Daniels M et al. Clinical Challenges Associated with Universal Screening for Lynch Syndrome-Associated Endometrial Cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2017;10: 108–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Broaddus RR, Lynch HT, Chen LM et al. Pathologic features of endometrial carcinoma associated with HNPCC: a comparison with sporadic endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bokhman JV. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983;15: 10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Santoro A, Angelico G, Travaglino A et al. New Pathological and Clinical Insights in Endometrial Cancer in View of the Updated ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Giaquinto AN, Broaddus RR, Jemal A, Siegel RL. The Changing Landscape of Gynecologic Cancer Mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139: 440–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D et al. Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375: 794–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Saed L, Varse F, Baradaran HR et al. The effect of diabetes on the risk of endometrial Cancer: an updated a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2019;19: 527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Barry JA, Azizia MM, Hardiman PJ. Risk of endometrial, ovarian and breast cancer in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20: 748–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348: 1625–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wahl S, Drong A, Lehne B et al. Epigenome-wide association study of body mass index, and the adverse outcomes of adiposity. Nature. 2017;541: 81–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dick KJ, Nelson CP, Tsaprouni L et al. DNA methylation and body-mass index: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2014;383: 1990–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Slattery ML, Potter JD, Curtin K et al. Estrogens reduce and withdrawal of estrogens increase risk of microsatellite instability-positive colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61: 126–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kurnit KC, Kim GN, Fellman BM et al. CTNNB1 (beta-catenin) mutation identifies low grade, early stage endometrial cancer patients at increased risk of recurrence. Mod Pathol. 2017;30: 1032–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M et al. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371: 569–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Burzawa JK, Schmeler KM, Soliman PT et al. Prospective evaluation of insulin resistance among endometrial cancer patients. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;204: 355.e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McQuade JL, Daniel CR, Hess KR et al. Association of body-mass index and outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or chemotherapy: a retrospective, multicohort analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2018;19: 310–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Winder AA, Kularatna M, MacCormick AD. Does Bariatric Surgery Affect the Incidence of Endometrial Cancer Development? A Systematic Review. Obesity Surgery. 2018;28: 1433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Upala S, Anawin S. Bariatric surgery and risk of postoperative endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11: 949–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Adams TD, Stroup AM, Gress RE et al. Cancer incidence and mortality after gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17: 796–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Aminian A, Wilson R, Al-Kurd A et al. Association of Bariatric Surgery With Cancer Risk and Mortality in Adults With Obesity. Jama. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ward KK, Shah NR, Saenz CC et al. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among endometrial cancer patients. Gynecologic Oncology. 2012;126: 176–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Boruta DM 2nd, Gehrig PA, Groben PA et al. Uterine serous and grade 3 endometrioid carcinomas: is there a survival difference? Cancer. 2004;101: 2214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].MacKintosh ML, Derbyshire AE, McVey RJ et al. The impact of obesity and bariatric surgery on circulating and tissue biomarkers of endometrial cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2019;144: 641–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Naqvi A, MacKintosh ML, Derbyshire AE et al. The impact of obesity and bariatric surgery on the immune microenvironment of the endometrium. International Journal of Obesity. 2022;46: 605–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Barres R, Kirchner H, Rasmussen M et al. Weight loss after gastric bypass surgery in human obesity remodels promoter methylation. Cell Rep. 2013;3: 1020–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Benton MC, Johnstone A, Eccles D et al. An analysis of DNA methylation in human adipose tissue reveals differential modification of obesity genes before and after gastric bypass and weight loss. Genome biology. 2015;16: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort