Abstract

Objectives:

Although cortical midline structures (CMS) are the most commonly identified neural foundations of self-appraisals, research is beginning to implicate the temporal-parietal junction (TPJ) in more interdependent self-construals. The goal of this study was to extend this research in an understudied population by a) examining both direct (first-person) and reflected (third-person) self-appraisals across two domains (social and academics), and b) exploring individual differences in recruitment of TPJ during reflected self-appraisals.

Methods:

The neural correlates of direct and reflected self-appraisals in social and academic domains were examined in 16 Chinese young adults (8M/8F, aged 18–23 years) using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

Results:

As expected, when making reflected self-appraisals (i.e., reporting what they believed others thought about them, regardless of domain) Chinese participants recruited both CMS and TPJ. Similar to previous research in East Asian and interdependent samples, CMS and TPJ were relatively more active during direct self-appraisals in the social than academic domain. We additionally found that, to the extent participants reported that reflected academic self-appraisals differed from direct academic self-appraisals, they demonstrated greater engagement of TPJ during reflected academic self-appraisals. Exploratory cross-national comparisons with previously published data from American participants revealed that Chinese young adults engaged TPJ relatively more during reflected self-appraisals made from peer perspectives.

Conclusions:

In combination with previous research, these findings increase support for a role of TPJ in self-appraisal processes, particularly when Chinese young adults consider peer perspectives. The possible functional contributions provided by TPJ are explored and discussed.

Keywords: self, cultural neuroscience, culture, perspective-taking, medial prefrontal cortex, temporal-parietal junction

Psychologists have identified several contexts in which what we believe people think about us (reflected self-appraisals) is particularly relevant to what we think of ourselves (direct self-appraisals). For example, in childhood and adolescence, self-views may be significantly shaped by the actual and/or perceived views of others (as proposed in symbolic interactionism; Baldwin, 1895; Cooley, 1902; Harter, 1999; Mead, 1934). Cross-cultural work suggests that reflected self-appraisals should remain influential on direct self-appraisals across development for members of collectivist cultures (Gardner, Gabriel, & Lee, 1999; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 1995). Even within these developmental and cultural contexts, however, self-evaluations depend on others’ actual or perceived opinions much more in some domains than others. In particular, the social domain’s relative lack of objective external indicators may make it particularly sensitive to reflected self-appraisals across cultures (Bohrnstedt & Felson, 1983; Hymel, LeMare, Ditner, & Woody, 1999; Li, 2007). In a previous study, we explored how developmental stage (adolescence versus adulthood) impacted the apparent tendency to take others’ perspectives into account in one’s self-evaluations, using neuroimaging methodologies (Pfeifer, Masten, Borofsky, Dapretto, Lieberman, & Fuligni, 2009). In the current neuroimaging study we extend this line of research by asking young adults from Beijing, China to report on their social and academic qualities directly and from reflected viewpoints (in other words, to take first-person and third-person perspectives on the self).

Influences of culture and domain on self-appraisals

The culture in which one is raised has a significant impact on the way that an individual views himself or herself in relation to others (Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001; Triandis, 1995). In particular, seeing oneself as independent from or interdependent upon others – also known as self-construal styles – can affect individuals’ cognitions, emotions, and motivations (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). For example, in one study Japanese college students’ self-concepts were more influenced by the presence of others than those of their American counterparts (Kanagawa, Cross, & Markus, 2001), and more generally East Asian cultures are characterized by thinking about things relationally (Gardner et al., 1999; Masuda & Nisbett, 2006). Furthermore, North Americans tend to self-enhance when given the opportunity (Baumeister, Tice, & Hutton, 1989; Taylor & Brown, 1988), whereas East Asians often show little or no evidence of this self-enhancing bias (Heine & Hamamura, 2007) and may self-criticize. In summary, cultural orientation has the potential to substantially influence not only the formation and valence of people’s self-concept, but also when and how they take others’ perspectives.

In addition to broad cultural differences in self-construal style, much research has indicated that evaluative self-knowledge is organized by content area into domain-specific self-concepts (as reviewed by Harter, 1999). It is important to note that although cultural influences on self-construals were originally conceptualized in a rather broad manner and investigated on a national or ethnic scale, recent research reveals self-construal style across cultures to be dynamic, malleable, and context-sensitive (e.g., Oyserman, Sorensen, Reber, & Chen, 2009). Thus, within both independent and interdependent cultures, self-evaluations vary across domains in content, valence, and importance, as well as the criteria on which they are based (Chan, 1997; Chan, 2002; Watkins, Dong, & Xia, 1997; Yeung & Lee, 1999). In social domains, even within individualistic cultures, the primary “objective” criterion is arguably the perceptions of others – we are only as socially skilled as others perceive us to be. For example, inventories of social skills frequently attempt to assess whether the target is perceived to be socially skilled by relevant others (e.g., Cairns, Leung, Gest, & Cairns, 1996; Riggio, 1986). In contrast, domains like academics and athletics possess many objective, external indicators of success or failure (e.g., grades on tests, report cards, and homework assignments in academics) that help to shape direct self-appraisals of competence and ability at a young age (Denissen, Zarrett, & Eccles, 2007; Eccles et al., 1993; Wigfield et al., 1993). For example, in the academic and athletic domains, preadolescents report using direct sources of information and personal observations of their own performance to inform self-evaluations; however, in the social domain, preadolescents report exclusive reliance on indirect and inferential sources of information – like perceptions of peers’ opinions (Hymel et al., 1999; see also Marsh, 1988; Marsh, Craven, & Debus, 1991). Given that the information available to help form and maintain self-appraisals in the social domain is typically much more ambiguous than in other domains like academics or athletics (Bohrnstedt & Felson, 1983), social self-construals may be highly dependent on reflected self-appraisals.

The previous examples were drawn primarily from independent cultures, but a similar dichotomy in self-evaluative orientations across domains is present in interdependent cultures as well. For instance, in China researchers have demonstrated that regardless of self-construal style, self-concepts in the academic domain are strongly autonomous, which stands out in comparison to the social, interdependent orientation that tends to dominate peer and family contexts (Li, 2001, 2002, 2003a/b, 2005, 2006; Li & Yue, 2004; Wang & Li, 2003). Chinese students are more likely to concentrate on improving their own academic performance over time than comparing with other students, and the strongest reported cause of academic achievement for Chinese students is a factor perceived as internal and individually controllable, effort, rather than external factors (Hau & Salili, 1996). Additionally, Chinese students adopt independent goals and exhibit self-direction in learning to an equal extent as Europeans (Gieve & Clark, 2005). Critically for this study, this observed individualism in Chinese academic self-concept is based on nationality rather than a presumed or assessed collectivistic self-construal style.

Of course, academic competence is seen as an area in which excellence is valued by the family and society (Kim, 1997; Yu, 1996; Yu & Yang, 1994), and Chinese students can exhibit great concern with assisting poorly performing peers (Heyman, Fu, & Lee, 2008). However, interdependent values should be considered distinctly from independent academic self-perceptions, as the latter are the focus of this study and not the former. Li (2001, 2002, 2003a/b, 2005, 2006) has extensively documented how Confucian ideals regarding learning may facilitate greater independence and self-reliance in Chinese children and adults, including more individualistic perceptions and goals in number and type for the academic compared to the social domain. Following elementary school in China, student performance is rigorously tested and tracked (Zhao, 2007) making public evaluations of academic attributes common, clear, and relatively stable. However, social performance may be considered as a work-in-progress of continual importance in China for multiple reasons. Others’ views about one’s social attributes are considered out of respect for them (Triandis, 1995), and because the definition of competence in this area relies on others’ opinions, one will continue to seek their perspective. Therefore, exploring the neural correlates of the social versus academic self is specifically interesting in China because of the previously documented contrast between interdependence in the social domain and independence in the academic domain.

Rationale for Cultural Neuroscience Research

The preceding literature review provides the following working hypothesis about self-evaluative processing in Chinese young adults: the social domain should elicit relatively more interdependent self-construals than the academic domain, and thereby increase the tendency to use reflected appraisal-like processes even when not explicitly asked to think about the opinions of others. We believe it may be particularly informative to take a cultural neuroscience approach to this topic. Cultural neuroscience is a rapidly growing field that has begun to demonstrate how culture and the brain interact (Ames & Fiske, 2010; Chiao & Ambady, 2007; Chiao, Cheon, Pornpattananangkul, Mrazek, & Blizinsky, 2013; Han et al., 2013; Kitayama & Park, 2010; Kitayama & Tompson, 2010; Losin, Dapretto, & Iacoboni, 2010; Malafouris, 2010; Zhou & Cacioppo, 2010), including specifically in the area of self-construals (Han & Northoff, 2008, 2009). Some advantages of using neuroimaging to explore direct and reflected self-appraisals within and across cultures include that it allows us to focus on the cognitive and affective processes involved in each, and supplement self-report data which may be biased in various ways (Pfeifer & Peake, 2012).

Direct self-appraisals.

The pioneering studies in cultural neuroscience have demonstrated both similarities to and differences from the standard patterns associated with self-referential processing. Work conducted predominantly with European and European-American samples suggests that anterior rostral medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and adjacent perigenual anterior cingulate cortex (pACC) support self-referential processing (D’Argembeau et al., 2007; Denny, Kober, Wager, & Ochsner, 2012; Heatherton et al., 2006; Northhoff et al., Panksepp, 2006; Oschner et al., 2005; Pfeifer & Peake, 2012). Many early cultural neuroscience studies explored how varying levels of collectivism and individualism in Western and Asian samples affected self-referential processing. In short, mPFC engagement seems to be influenced by a correspondence between cultural orientation (collectivist or individualistic) and the kind of appraisal being made. Several studies converge on the finding that mPFC activation when appraising the self (relative to a mother) is greater in Western or more individualistic participants (Ma et al., 2014; Ray et al., 2010; Zhu, Zhang, Fan, & Han, 2007), although self-motivated recent immigrants from China also show significant differentiation between self and mother (Chen, Wagner, Kelly, & Heatherton, 2013). Additionally, participants who were naturally more individualistic (as determined by the Self-Construal Scale; Singelis, 1994) or primed with individualistic values showed greater activation in mPFC when retrieving general, decontextualized self-knowledge, while participants who endorsed more collectivist self-construal styles showed greater mPFC activation during context-specific self-referential processing (Chiao et al., 2009; Chiao et al., 2010). That is, cultural priming seemed to facilitate activity in mPFC during prime-congruent self-knowledge retrieval (see also Ng, Han, Mao, & Lai, 2010).

Reflected self-appraisals.

Thus far, cultural neuroscience investigations of self-referential processing have focused on direct appraisals of oneself (and others), and not yet extended to studying reflected self-appraisals. In addition to engaging mPFC due to their self-referential nature, reflected self-appraisals may include other cognitive and affective processes, ranging from perspective-taking (like putting yourself in someone else’s shoes to ascertain what they might think about you) to memory (remembering when they said you were a good listener) and emotion (feeling good about that positively-valenced reflected self-appraisal). A small handful of studies have specifically contrasted direct and reflected self-appraisals. Indeed, the first study of these processes found regions associated with emotion and memory, such as the insula and parahippocampus, were more active during reflected than direct self-appraisals (Ochsner et al., 2005). Another such study suggested that more dorsal mPFC is involved in differentiating one’s own from others’ perspectives on the self (D’Argembeau et al., 2007). We previously observed that during reflected self-appraisals, American adolescents and adults both exhibited activity in brain regions associated with self-referential processing (anterior rostral mPFC) and perspective-taking (including temporal-parietal junction (TPJ), posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), as well as more dorsal aspects of mPFC; Jankowski et al., 2014; Pfeifer et al., 2009; see also Legrand & Ruby, 2009).

Finally, two recent cultural neuroscience studies implicated TPJ in interdependent self-construals, and are thus highly relevant to the current study. Researchers comparing Chinese and Danish individuals making direct self-appraisals in social, mental, and physical domains observed that direct social self-appraisals recruited TPJ more strongly in Chinese than Danish participants, and this was mediated by self-construal style (Ma et al., 2014). Additionally, in a study of Korean young adults, those with a more collectivist orientation showed stronger activation in TPJ during self-referential encoding of personality traits and social identities, compared to those with a more individualistic orientation (Sul, Choi, & Kang, 2012). These results suggest that interdependent self-construal style, operationalized at both national and individual levels, may elicit a high degree of perspective-taking – especially when appraising the self in a domain where others’ evaluations are highly relevant.

The Present Study

Based on the above literature review we hypothesized that in China, a nation which shows significant interdependence in the social domain but substantial independence in academics, young adults would display more anterior rostral mPFC as well as TPJ, pSTS, and dorsal mPFC activations during direct self-appraisals in the social than academic domain. We further expected that TPJ would be particularly active during reflected self-appraisals to the extent those differed from direct self-appraisals, providing greater insight as to the function of TPJ in self-appraisals, representing the primary novel question of interest in this study. The overall goal of the study was to interrogate the neural systems supporting self-appraisal processes from multiple perspectives (direct and reflected) across two domains (social and academic) in a relatively understudied population (Chinese young adults). Our a priori ROIs throughout are derived from our previous work (Pfeifer et al., 2009) and include mPFC (anterior rostral and dorsal aspects), mPPC, TPJ, and pSTS; with primary emphasis on TPJ.

Material and Methods

Participants

Participants were sixteen Chinese young adults (eight male), ranging in age from 18 to 23 years (M = 20.8, SD = 1.8 years), about whom detailed information regarding socioeconomic status and ethnicity was not collected. They were recruited from the undergraduate (age ≤ 22) and graduate student (age 23) population at Beijing Normal University in Beijing, China. All participants provided written informed consent, were right-handed, did not report any neurological or psychological diagnoses, and were screened for any contraindications to completing an MRI scan. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning at Beijing Normal University. New behavioral data and additional analyses of previously reported fMRI data are presented here from our prior study (Pfeifer et al., 2009) of twelve American young adult graduate students (six male), ranging in age from 23 to 30 years (M = 25.7, SD = 2.1 years), about whom detailed information regarding socioeconomic status and ethnicity was likewise not collected.

Procedures

Stimuli.

The task used during the fMRI scan consisted of 40 unique, self-descriptive phrases translated from the stimuli (used in Pfeifer et al., 2009) by a team consisting of Chinese-English bilinguals as well as native English and Chinese speakers (double-checked with forward and backward translation). Translated phrases were then read and recorded by a female Mandarin speaker. These stimuli included an equal number of positively and negatively valenced phrases, and represented two core self-concept domains – social competence and verbal academic ability. We specified verbal academics because a large body of previous literature, including cross-cultural investigations, shows that academic self-concepts can vary by subject area (e.g., Marsh & Craven, 2006). Sample phrases for each category include: “I am popular ( ), I make friends easily, I feel lonely at school” in the social domain or “I read very quickly (

), I make friends easily, I feel lonely at school” in the social domain or “I read very quickly ( ), I get good grades in Chinese, I’m bad at writing” in the academic domain.

), I get good grades in Chinese, I’m bad at writing” in the academic domain.

Appraisal task.

While being scanned, participants heard verbal instructions in Mandarin to make either direct self-appraisals or reflected self-appraisals from the perspectives of their mother, best friend, or classmates.1 Before each set of direct self-appraisals, participants heard the instructional cue: “Do you think the following phrase fits you well…” ( ) followed by a series of 10 phrases (5 positive and 5 negative from a given domain). The valence of stimuli varied across trials in a pseudorandom fashion, to prevent participants from developing a response strategy. Before each set of reflected self-appraisals, participants heard a similar instructional cue indicating which perspective they should take, for example: “Does your mom think the following phrase fits you well…” (

) followed by a series of 10 phrases (5 positive and 5 negative from a given domain). The valence of stimuli varied across trials in a pseudorandom fashion, to prevent participants from developing a response strategy. Before each set of reflected self-appraisals, participants heard a similar instructional cue indicating which perspective they should take, for example: “Does your mom think the following phrase fits you well…” ( ) followed by the same series of 10 phrases. Participants heard each series of 10 phrases 4 times in a row, each time preceded by an instructional cue directing them to take a different perspective. Participants appraised each of the phrases once from each of the 4 possible perspectives (self, mother, best friend, and classmates). Finally, as control conditions presented in a final run, participants also made direct appraisals in each domain about their best (same-gender) friend, as well as direct appraisals in each domain about the valence (good/bad), of the same exact phrases.

) followed by the same series of 10 phrases. Participants heard each series of 10 phrases 4 times in a row, each time preceded by an instructional cue directing them to take a different perspective. Participants appraised each of the phrases once from each of the 4 possible perspectives (self, mother, best friend, and classmates). Finally, as control conditions presented in a final run, participants also made direct appraisals in each domain about their best (same-gender) friend, as well as direct appraisals in each domain about the valence (good/bad), of the same exact phrases.

Participants heard auditory stimuli through headphones and responded yes/no to each phrase using a button box. Stimuli were presented and responses and reaction times were recorded using E-Prime. Each run (out of three total) contained 8 blocks of 10 phrases (2 sets of 10 unique phrases repeated 4 times each), resulting in a total of 160 phrases in 16 blocks. Each block lasted 52.0 seconds and consisted of an initial instruction cue lasting 6.0 seconds as well as 10 phrases, 1 phrase presented every 4.6 seconds. Phrases averaged approximately 1.5 seconds in length, leaving participants approximately 3.0 seconds to respond. Rest periods before each block lasted 12.0 seconds. Because the same 10 stimuli were used in 4 consecutive blocks, each run contained a total of 4 blocks from the social domain and 4 blocks from the academic domain. Order of domains and perspectives appraised within runs were counterbalanced between participants using a Latin Square design. However, the control conditions were always presented in the third run only, while all direct and reflected self-appraisals occurred in the first two runs.

fMRI data acquisition.

Images were acquired using a Siemens Trio 3.0 Tesla scanner at the MRI center of Beijing Normal University. A localizer was acquired to allow for prescription of the slices to be obtained in the remaining scans. Each functional scan lasted 8 min and 48 sec, providing 264 images per scan. (This reflects the additional time needed to present the stimuli in Chinese instead of English.) These 264 images were collected over 33 axial slices covering the whole cerebral volume using a T2*-weighted gradient-echo sequence (TR = 2000 msec, TE = 30 msec, flip angle = 90°, matrix size 64 × 64, FOV = 20 cm; 3.125-mm in-plane resolution, 4-mm thick, 1-mm gap). For each participant, high-resolution structural data were acquired using a T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence (TR = 2530 msec, TE = 3.39 msec, flip angle = 7°, matrix size 256 × 256, FOV = 25.6 cm; 1-mm in-plane resolution, 1.33-mm thick) in sagittal view for 128 slices.

fMRI data analysis.

Imaging data were preprocessed and analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM8; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, Institute of Neurology, London, UK; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), MarsBaR (MARSeille Boîte À Région d’Intérêt; Brett et al., 2002), and NeuroElf (http://neuroelf.net/). Functional images for each participant were: (a) realigned to correct for head motion; (b) spatially normalized into a standard stereotactic space defined by the Montreal Neurological Institute and the International Consortium for Brain Mapping, reslicing to 2×2×2 mm voxels; and (c) smoothed using an 8-mm full-width, half-maximum isotropic Gaussian kernel. No participant demonstrated greater than 1.5 mm of image-to-image motion in any run.

For each participant, condition effects were estimated according to the general linear model, using a canonical hemodynamic response function convolved with the block design described above, high-pass filtering (128 sec) to remove low-frequency noise, and an autoregressive model (AR(1)) to estimate intrinsic autocorrelation of the data. Eight contrast images representing each self-appraisal perspective, relative to direct other-appraisal in the same domain which functioned as a control (e.g., direct social self-appraisals > direct social other-appraisals) were entered into second-level analyses using a random effects model to allow for inferences to be made at the population level (Friston et al., 1999). Note that inclusion of the direct other-appraisals as a control condition made some analyses more conservative (particularly the comparison between direct social and academic self-appraisals), as results were typically more robust without the control condition (greater magnitude and spatial extent). Whole-brain analyses were thresholded at p < .005, and corrected for multiple comparisons at the cluster level (p < .05) using 3dClustSim (k = 57).

To interrogate the role of right TPJ in the Chinese sample closely, we extracted percent signal change using MarsBaR scripts from an 8mm sphere at the peak voxel in two TPJ ROIs identified by recent meta-analyses on self/other-appraisals and theory of mind ([52 −50 22] from Denny et al. (2012), and [56 −56 18] from Schurz, Radua, Aichhorn, Richlan, & Perner (2014)). Results were largely consistent across ROIs, frequently at the same statistical thresholds and always in the same direction, and as such are presented here from Denny et al. (2012). This approach was chosen because the American fMRI data was in Talairach space while the Chinese fMRI data was in MNI space; American data were no longer available in raw form to allow them to be re-analyzed using the exact same processing stream. As such, we transformed the peak voxels from MNI to Talairach space for the American sample, to facilitate exploratory comparisons with the Chinese sample in this ROI. We note that extreme caution is warranted when comparing the two samples, since scanner site is entirely correlated with participant nationality.

Results

Behavioral Data

Due to computer error, responses and latencies were unavailable for one participant. Reaction times were entered into an ANOVA with two within-subject factors: domain (academic or social) and perspective (self, mother, best friend, or classmates). Results revealed no significant main effects or interactions for reaction times due to either perspective or domain (see Table 1 for means and standard deviations of reaction times for each condition). However, a post-hoc paired t-test showed that participants had faster reaction times when making direct self-appraisals in the academic domain, compared to the average of all the other conditions (t(14) = 2.41, p = .05; 95% CI of the difference = 14.32 to 237.01 ms). Furthermore, a post-hoc paired t-test comparing reaction times for direct self-appraisals in the academic and social domains approached significance (t(14) = 1.90, p = .08; 95% CI of the difference = 13.27 to 224.73 ms), which indicated that there tended to be slightly faster responses when making direct self-appraisals in the academic domain than the social domain.

Table 1.

Behavioral Data from Self-Appraisal Paradigm

| RT (in msec) | Agreement | |

|---|---|---|

| Condition | M (SD) | M (SD) |

|

| ||

| Direct Academic | 2593.10 (271.72) | |

| Direct Social | 2704.45 (238.85) | |

| Mother Academic | 2683.80 (217.90) | .82 (.13) |

| Mother Social | 2734.51 (207.15) | .86 (.08) |

| Best Friend Academic | 2704.82 (231.49) | .81 (.11) |

| Best Friend Social | 2746.59 (226.69) | .87 (.09) |

| Classmates Academic | 2689.55 (249.24) | .82 (.12) |

| Classmates Social | 2721.02 (192.06) | .89 (.09) |

Note: n=15 for each condition. There are no agreement scores for direct academic and direct social because agreement was calculated as percentage of matching item responses between direct self-appraisals and reflected self-appraisals made from the perspective of participants’ mother, best friend, or classmates.

We also created a measure of “agreement” from participants’ responses during the task. Agreement was calculated as the percentage of item responses that matched between a given domain-specific reflected self-appraisal condition and its corresponding domain-specific direct self-appraisal (e.g., reporting that you think you make friends easily, and that your best friend thinks you do as well, would be coded as an agreement in the best-friend/social category; while reporting that your mom thinks you do not, would be coded as a disagreement in the mom/social category). This procedure resulted in six agreement values for each participant (two per domain across three target perspectives). A repeated-measures ANOVA conducted on agreement values with the same two within-subject factors (domain and perspective) showed a marginally significant main effect of domain: agreement was greater in the social than academic domain (F(1, 14) = 3.85, p = .07, partial η2 = .22; see Table 1 for means and standard deviations of agreement scores for each reflected appraisal condition). There was no significant effect of perspective, as well as no significant interaction between perspective and domain (F(2, 13) = 0.81, p = .47, partial η2 = .04; and F(2, 13) = 1.72, p = .22, partial η2 = .05; for the main effect and interaction, respectively).

fMRI Data

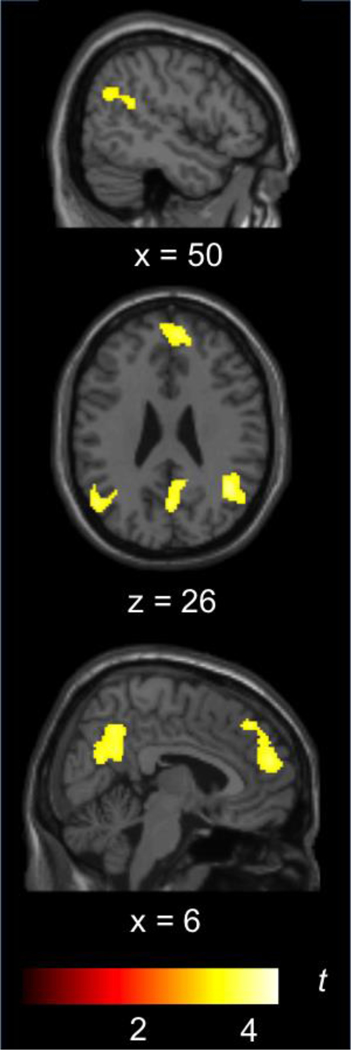

We hypothesized that because of national traditions in China that emphasize interdependence in most forms of social life, but independence in academics and learning, Chinese young adults would engage a similar network of regions for all reflected self-appraisals, and direct appraisals of the social (relative to the academic) self. The critical analysis step was to build a t contrast representing a specific interaction between domain and appraisal perspective, identifying activity that was similarly high in all conditions except during direct self-appraisals in the academic domain, where the least activity was predicted ([AllReflected + DirectSocial] > [DirectAcademic]; i.e., equal positive weightings summing to 1 across all conditions except direct academic evaluations, coded as a −1). In this analysis, mPFC (a large cluster encompassing both dorsal and anterior rostral aspects), mPPC, and bilateral TPJ/pSTS were all significantly more active during direct self-appraisals in the social domain and reflected self-appraisals in both domains, relative to direct self-appraisals in the academic domain (see Figure 1 and Table 2). Examining the social domain for regions more active during reflected self-appraisals than direct self-appraisals resulted in no significant clusters ([SocialReflected > DirectSocial]). In contrast, the same regions were more active during academic reflected self-appraisals than academic direct self-appraisals as in the initial interaction analysis ([AcademicReflected > DirectAcademic]); that is, significant clusters were observed in mPFC (a large cluster encompassing both dorsal and anterior rostral aspects), medial posterior parietal cortex (mPPC), and bilateral TPJ/pSTS. No regions were relatively more active during direct self-appraisals than reflected self-appraisals in the academic domain ([DirectAcademic > AcademicReflected]), although the fusiform gyrus and precuneus in mPPC were more active during direct self-appraisals than reflected self-appraisals in the social domain ([DirectSocial > SocialReflected]).

Figure 1. Clusters Relatively More Active During Direct Social and All Reflected Self-Appraisals than Direct Academic Self-Appraisals.

Bilateral TPJ, anterior rostral and dorsal mPFC, and mPPC regions showed significantly more activity during direct self-appraisals in the social domain as well as reflected self-appraisals in either domain, when compared with direct self-appraisals in the academic domain (note that direct other-appraisals in each domain were used as a control). Results are displayed at p < .005, with a cluster size threshold of k = 57 (achieves correction for multiple comparisons). x and z refer to the MNI coordinates corresponding to the left-right and inferior-superior axes, respectively. TPJ, mPFC, and mPPC refer to temporal-parietal junction, medial prefrontal cortex, and medial posterior parietal cortex, respectively.

Table 2.

Comparisons between Direct and Reflected Self-Appraisals in the Social and Academic Domains

| Region | x | y | z | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

|

All Reflected Self-Appraisals and Direct Social Self-Appraisals

> Direct Academic Self-Appraisals | |||||

|

| |||||

| armPFC BA10 | 14 | 58 | 14 | 4.13 | |

| 8 | 52 | 22 | 3.41 | ||

| dmPFC BA8/9 | 8 | 40 | 46 | 3.31 | |

| mPPC | 0 | −56 | 34 | 3.65 | |

| TPJ | L | −52 | −56 | 28 | 2.83 |

| R | 44 | −56 | 26 | 3.63 | |

| TPJ/pSTS | R | 50 | −46 | 22 | 3.08 |

| aSTS/TP | L | −54 | −16 | −10 | 2.97 |

| rACC BA24 | 6 | 34 | 8 | 3.58 | |

| −10 | 32 | 10 | 3.39 | ||

| DLPFC BA8 | R | 18 | 20 | 46 | 3.03 |

|

| |||||

| Reflected Academic Self-Appraisals > Direct Academic Self-Appraisals | |||||

|

| |||||

| armPFC BA10 | 14 | 60 | 14 | 4.29 | |

| 8 | 54 | 18 | 3.77 | ||

| dmPFC BA8/9 | 6 | 40 | 46 | 3.14 | |

| mPPC BA31/7 | 4 | −66 | 24 | 4.07 | |

| TPJ | L | −48 | −66 | 28 | 3.83 |

| R | 44 | −50 | 26 | 3.53 | |

| pSTS | R | 46 | −40 | 16 | 3.72 |

| R | 62 | −44 | −2 | 3.10 | |

| aSTS | L | −50 | −16 | −6 | 3.73 |

| R | 60 | −6 | −12 | 3.16 | |

| Precentral Gyrus BA6 | L | −58 | −14 | 40 | 3.23 |

| Cerebellum | R | 20 | −82 | −38 | 3.20 |

| L | −16 | −80 | −34 | 3.18 | |

| VLPFC BA47 | L | −40 | 24 | −12 | 3.04 |

| DLPFC BA8 | L | −30 | 16 | 40 | 3.83 |

| R | 44 | 12 | 44 | 2.89 | |

|

| |||||

| Reflected Social Self-Appraisals > Direct Social Self-Appraisals | |||||

|

| |||||

| N/A | |||||

|

| |||||

| Direct Academic Self-Appraisals > Reflected Academic Self-Appraisals | |||||

|

| |||||

| N/A | |||||

|

| |||||

| Direct Social Self-Appraisals > Reflected Social Self-Appraisals | |||||

|

| |||||

| Fusiform Gyrus BA37 | R | 40 | −42 | −18 | 3.94 |

| mPPC BA7 | −16 | 64 | 32 | 3.42 | |

| Parahippocampal Gyrus BA35/36 | R | 22 | −30 | −20 | 3.32 |

| Middle Occipital Gyrus BA19 | R | 44 | −76 | 4 | 3.30 |

Note: This analysis controls for direct other-appraisals. BA refers to putative Brodmann’s Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y, and z refer to the left-right, anterior-posterior, and inferior-superior dimensions, respectively; t refers to the t-score at those coordinates (local maxima or submaxima); and armPFC, dmPFC, mPPC, TPJ, pSTS, aSTS, VLPFC and DLPFC refer to anterior rostral medial prefrontal cortex, dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, medial posterior parietal cortex, temporal-parietal junction, posterior superior temporal sulcus, superior temporal gyrus, anterior superior temporal sulcus, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, respectively.

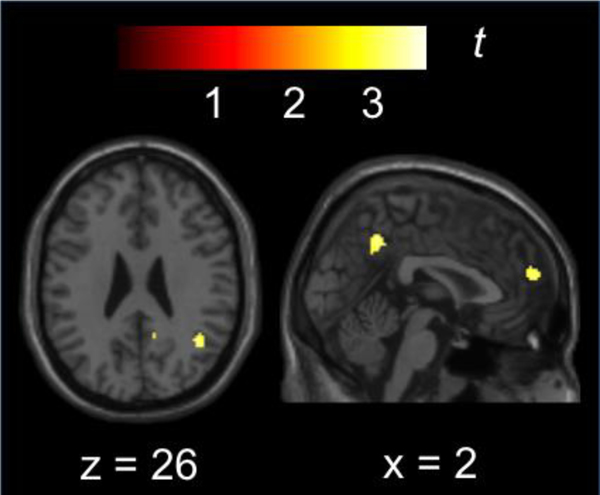

We also specifically compared direct self-appraisals in the social and academic domains ([DirectSocial > DirectAcademic]). In a whole-brain analysis, greater activity was observed in anterior rostral mPFC, mPPC, and right TPJ when directly reporting on one’s social traits compared to one’s academic attributes (see Figure 2 and Table 3). The reverse comparison found no clusters of activity that were greater in academic than social direct self-appraisals ([DirectAcademic > DirectSocial]).

Figure 2. Clusters Relatively More Active During Direct Social Self-Appraisals than Direct Academic Self-Appraisals.

mPFC, mPPC, and right TPJ regions showed significantly more activity during direct self-appraisals in the social domain than the academic domain (note that direct other-appraisals in each domain were used as a control). Results are displayed at p < .005, with a cluster size threshold of k = 27. x and z refer to the MNI coordinates corresponding to the left-right and inferior-superior axes, respectively. TPJ, mPFC, and mPPC refer to temporal-parietal junction, medial prefrontal cortex, and medial posterior parietal cortex, respectively.

Table 3.

Clusters Relatively More Active During Direct Social Self-Appraisals than Direct Academic Self-Appraisals

| Region | x | y | z | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| armPFC BA 10 | 14 | 58 | 12 | 3.46^ | |

| −2 | 60 | 18 | 3.08 | ||

| mPPC | 2 | −52 | 44 | 3.09 | |

| TPJ | R | 44 | −56 | 26 | 2.99^ |

| OFC BA 11 | R | 34 | 40 | −6 | 3.32 |

| Hippocampal Gyrus | L | −36 | −30 | −10 | 3.06^ |

Note: This analysis controls for direct other-appraisals. BA refers to putative Brodmann’s Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y, and z refer to the left-right, anterior-posterior, and inferior-superior dimensions, respectively; t refers to the t-score at those coordinates (local maxima or submaxima); and armPFC, mPPC, TPJ, and OFC refer to anterior rostral medial prefrontal cortex, medial posterior parietal cortex, temporal-parietal junction, and orbitofrontal cortex, respectively.

denotes clusters greater than 27 but less than 57 voxels.

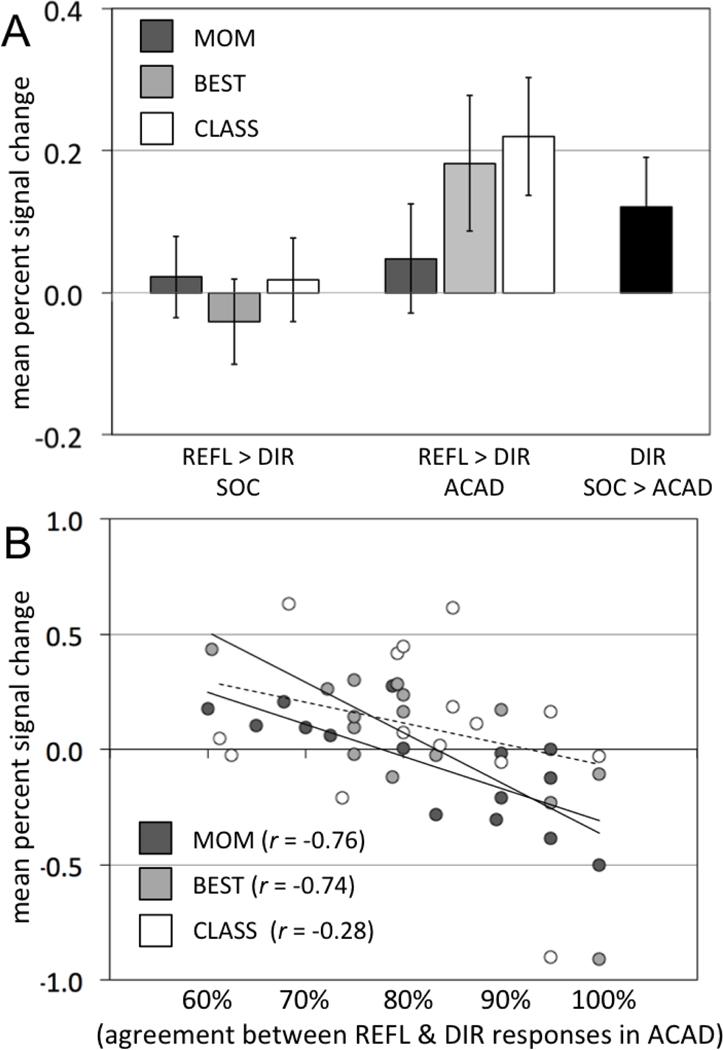

To further clarify these findings and interrogate the role of TPJ in particular, we extracted percent signal change from an independent right TPJ ROI (from the meta-analysis in Denny et al., 2012) to explore by condition. This was useful because the contrasts described above averaged across multiple types of reflected appraisals. Repeated-measures ANOVAs for each domain were followed by post-hoc comparisons. In the social domain there were no significant differences between any reflected self-appraisal perspective (mother, best friend, and classmates) and direct self-appraisals – suggesting right TPJ was recruited relatively equally across all perspectives in the social domain (F (2.095, 31.427) = .638, p = .542, partial η2 = .041, Greenhouse-Geisser corrected). However, in the academic domain there were significant differences across perspectives (F (3, 45) = 4.699, p = .006, partial η2 = .239). Namely, classmate and best friend reflected academic self-appraisals engaged the right TPJ ROI significantly more than direct academic self-appraisals (see Figure 3A). A combined repeated measures ANOVA with two within-subject factors (domain, perspective) exhibited a marginally significant two-way interaction (F (3, 45) = 2.79, p = .051, partial η2 = .157). The specific contrast mirroring that run in the whole-brain analysis was statistically significant (F (1, 15) = 9.678, p = .007, partial η2 = .394).

Figure 3. Functionally Independent ROI Analysis of Right TPJ.

Panel A displays mean percent signal change extracted from one of the two independent ROIs in right TPJ ([52 −50 22], defined by the meta-analysis of self/other processing in Denny et al., 2012). In the social domain, there was no difference in activity between direct self-appraisals and reflected self-appraisals from any perspective (mother, best friend, or classmates). However, in the academic domain, reflected self-appraisals from peer perspectives (best friend and classmates) engaged right TPJ significantly more than direct self-appraisals. Direct self-appraisals trended towards engaging right TPJ more in the social than academic domain. Panel B depicts the correlation between percent signal change extracted from right TPJ and agreement in the academic domain (percentage of answers that matched between a given domain-specific reflected self-appraisal and the direct self-appraisal in that same domain). TPJ refers to the temporal-parietal junction; REFL refers to reflected appraisals; DIR refers to direct appraisals; SOC refers to the social domain; ACAD refers to the academic domain; BEST refers to the best friend perspective; and CLASS refers to the classmates’ perspective.

Next, we considered whether the behavioral data relating to agreement between direct and reflected self-appraisals related to the activity in TPJ. Specifically, we were interested in querying whether lower agreement between direct and reflected self-appraisals (that is, reporting that someone else thinks something different about you than you think about yourself) was associated with increased activity in TPJ – specifically in the academic domain, where agreement was marginally lower and more variable. We correlated agreement with activity during each academic reflected self-appraisal perspective in the same right TPJ ROI. The results showed that to the degree a participant reported less agreement between direct and reflected self-appraisals in the academic domain, they engaged the right TPJ ROI more during reflected self-appraisals, significantly so for close other (mother and best friend) perspectives (r (13) = −.76, −.74, and −.28, p = .001, .002, and .31, 95% CI = −.915 to −.406, −.908 to −.367, and −.692 to .271, for mother, best friend, and classmates, respectively; see Figure 3B). No significant correlations were found in the social domain (r (13) = −.43, −.10, and −.18, p = .11, .72, and .52, 95% CI = −.772 to .105, −.582 to .434, and −.633 to .366, for mother, best friend, and classmates, respectively), and the difference between the academic and social domain was significant for the best friend perspective only (Z = 3.36, p < .001; Lee & Preacher, 2013).

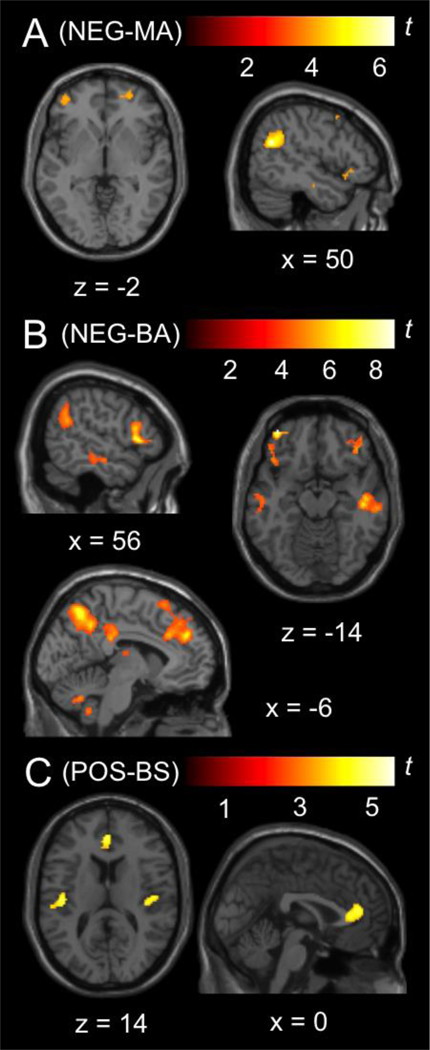

Importantly, whole-brain regression analyses were conducted to independently and more fully characterize the relationship between agreement and activity during reflected self-appraisals from other perspectives, as they would not be limited to the right TPJ. Significant negative correlations between agreement and activity were observed in several notable areas, including in the right TPJ which confirmed the previous ROI findings, as well as dorsal mPFC and bilateral VLPFC (see Figure 4 and Table 4 for results of all whole-brain regression analyses).

Figure 4. Whole-Brain Regressions and Agreement Between Direct and Reflected Self-Appraisals.

Panel A (NEG-MA) depicts activity in right TPJ and left VLPFC that was negatively correlated with mother-academic agreement in a whole-brain regression analysis, controlling for direct other-appraisals. Panel B (NEG-BA) depicts activity in right TPJ, mPPC, dorsal mPFC, and bilateral VLPFC that was negatively correlated with best friend-academic agreement in a whole-brain regression analysis, controlling for direct other-appraisals. Panel C (POS-BS) depicts activity in rostral ACC and bilateral posterior insula that was positively correlated with best friend-social agreement in a whole-brain regression analysis, controlling for direct other-appraisals. For more details, see Table 4. Results are displayed at p < .005, with a cluster size threshold of k = 57 (achieves correction for multiple comparisons). x and z refer to the MNI coordinates corresponding to the left-right and inferior-superior axes, respectively. TPJ, VLPFC, mPFC, mPPC, and ACC refer to temporal-parietal junction, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, medial posterior parietal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex, respectively.

Table 4.

Correlations Between Agreement and Activity During Reflected Self-Appraisals by Domain

| Region | x | y | z | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mother Academic- Positive | |||||

| Hippocampal Gyrus | −32 | −12 | −14 | 5.63 | |

| mPPC BA7 | 16 | −40 | 48 | 3.82 | |

| 2. Mother Academic-Negative | |||||

| TPJ | R | 52 | −58 | 24 | 6.44 |

| VLPFC BA47 | R | 44 | 22 | −18 | 3.96 |

| VLPFC BA44 | L | −38 | 52 | 0 | 3.63 |

| R | 28 | 54 | 0 | 3.51 | |

| Lateral Temporal Cortex BA 20/21 | R | 56 | −20 | 22 | 5.58 |

| 58 | −22 | −10 | 4.55 | ||

| mPPC BA31 | −6 | −68 | 16 | 4.79 | |

| mPPC BA7 | 6 | −70 | 48 | 3.76 | |

| mPPC BA23/31 | 8 | −62 | 10 | 3.59 | |

| Temporal Pole BA38 | R | 42 | 10 | −22 | 4.77 |

| Cerebellum | −2 | −80 | −34 | 4.59 | |

| Superior Parietal Lobule BA7 | R | 34 | −54 | 60 | 3.76 |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus BA6 | R | 40 | 10 | 48 | 3.68 |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus BA9/46 | L | −50 | 32 | 28 | 3.71 |

| 3. Mother Social- Positive | |||||

| N/A | |||||

| 4. Mother Social- Negative | |||||

| Cingulate Gyrus BA31 | −16 | −22 | 40 | 5.34 | |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus BA9/10 | 28 | 60 | 26 | 3.88 | |

| 5. Best Friend Academic-Positive | |||||

| N/A | |||||

| 6. Best Friend Academic- Negative | |||||

| mPPC BA7/31 | −6 | −62 | 54 | 6.56 | |

| TPJ/pSTS | L | −52 | −58 | 18 | 5.53 |

| R | 50 | −48 | 22 | 4.65 | |

| VLPFC BA11 | L | −38 | 54 | −14 | 8.35 |

| R | 46 | 46 | −14 | 3.75 | |

| VLPFC BA47 | R | 42 | 34 | −12 | 4.66 |

| L | −36 | 28 | −4 | 4.15 | |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus BA8 | R | 40 | 22 | 40 | 7.55 |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus BA6 | L | −20 | −14 | 60 | 4.04 |

| Cerebellum | −26 | −56 | −36 | 7.11 | |

| Thalamus | R | 14 | −6 | 12 | 6.6 |

| L | −16 | −10 | 8 | 4.4 | |

| Lateral Temporal Cortex BA21 | R | 46 | −24 | −10 | 6.46 |

| L | −52 | −20 | −4 | 4.61 | |

| Cuneus BA17 | L | −18 | −78 | 12 | 6.35 |

| Lingual Gyrus BA18/19 | 26 | −78 | 10 | 4.43 | |

| Superior Frontal Gyrus BA10 | R | 28 | 50 | 0 | 6.19 |

| Caudate | L | −12 | 4 | 16 | 5.05 |

| Cingulate Gyrus BA23/31 | −4 | −30 | 30 | 4.83 | |

| Superior Parietal Lobule BA7 | R | 24 | −66 | 60 | 4.32 |

| 7. Best Friend Social-Positive | |||||

| Rostral ACC BA 32 | 2 | 42 | 14 | 4.38 | |

| Posterior Insula | L | −40 | 2 | −4 | 4.5 |

| R | 44 | −16 | 8 | 4.35 | |

| Superior Temporal Gyrus BA 21/22 | R | 48 | −14 | 0 | 5.47 |

| Superior Parietal Lobule BA 7 | L | −20 | −60 | 30 | 4.82 |

| Temporal Pole BA 38 | R | 44 | 4 | −20 | 4.77 |

| Hippocampal Gyrus BA 36/37 | L | −20 | −34 | −6 | 4.1 |

| Lateral Temporal Cortex BA 21/37 | R | 56 | −38 | −2 | 3.6 |

| Cingulate Gyrus BA 24 | 14 | 2 | 28 | 3.25 | |

| 8. Best Friend Social-Negative | |||||

| Postcentral Gyus BA1/2 | −16 | −36 | 74 | 6.02 | |

| Cerebellum | 6 | −48 | −28 | 5.82 | |

| Fusiform Gyrus BA20/37 | −34 | −46 | −16 | 5.61 | |

| 9. Classmates Academic-Positive | |||||

| N/A | |||||

| 10. Classmates Academic-Negative | |||||

| Superior Frontal Sulcus BA6/8 | −14 | 30 | 42 | 5.55 | |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus BA6/8 | −30 | 2 | 44 | 4.18 | |

| Inferior Parietal Lobule BA40 | R | 30 | −34 | 30 | 5.2 |

| VLPFC BA45 | L | −50 | 26 | 4 | 4.86 |

| VLPFC BA47 | L | −46 | 30 | −3 | 4.57 |

| R | 44 | 38 | −12 | 3.68 | |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus BA10/46 | −32 | 48 | 8 | 4.35 | |

| Cingulate Gyrus BA24 | −4 | −2 | 26 | 4.44 | |

| Cerebellum | 28 | −84 | −36 | 4.32 | |

| pSTS | L | −50 | −40 | 0 | 4 |

| mPPC BA7 | −8 | −56 | 32 | 3.61 | |

| Caudate | R | 20 | 12 | 16 | 3.67 |

| L | −16 | 0 | 14 | 3.21 | |

| 11. Classmates Social-Positive | |||||

| N/A | |||||

| 12. Classmates Social-Negative | |||||

| N/A |

Note: This analysis controls for direct other-appraisals. BA refers to putative Brodmann’s Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y, and z refer to the left-right, anterior-posterior, and inferior-superior dimensions, respectively; t refers to the t-score at those coordinates (local maxima or submaxima); and mPPC, TPJ, pSTS, ACC and VLPFC refer to medial posterior parietal cortex, temporal-parietal junction, posterior superior temporal sulcus, anterior cingulate cortex, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, respectively.

Exploratory Comparisons between Chinese and American fMRI Data

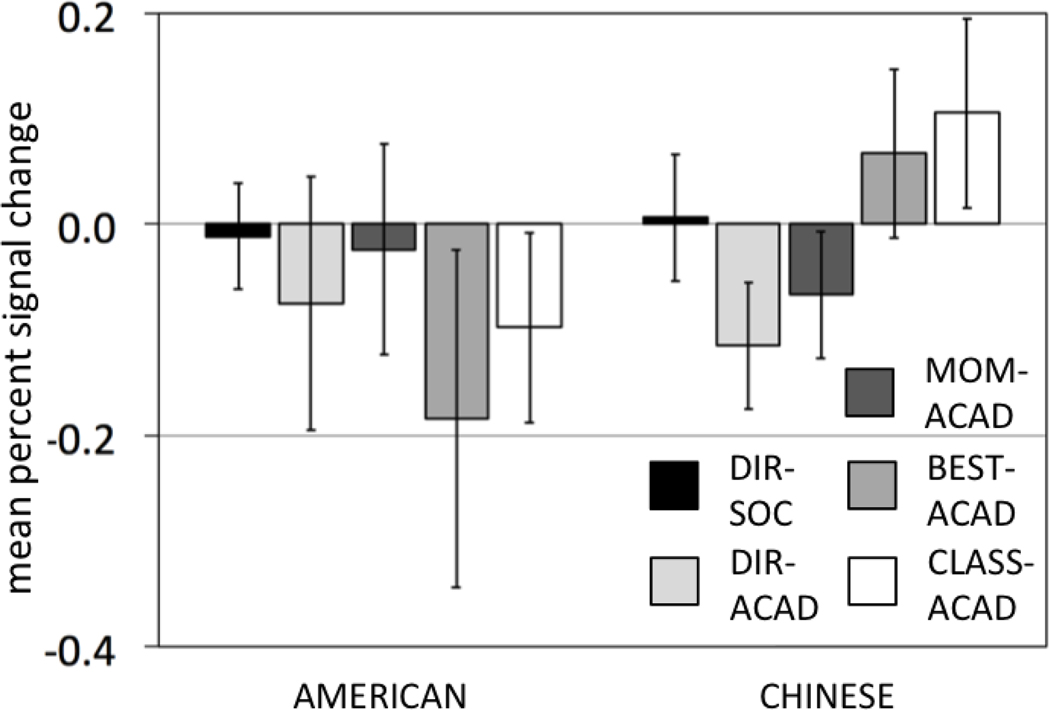

To facilitate exploratory cross-national comparisons, we also extracted percent signal change in the same right TPJ ROI from the American sample, after transforming the ROI from MNI to Talairach space. Following the process used above within the Chinese sample, we conducted a repeated-measures ANOVAs for each domain, having one within-subject factor (perspective: self, mother, best friend, or classmates) and one between-subject factor (nationality: American or Chinese). In the social domain, there was no significant interaction between perspective and nationality. This suggests that contrary to our implicit hypothesis, the Chinese sample did not engage TPJ relatively more during direct social self-appraisals than the American sample (F (3, 78) = 0.94, p = .424, partial η2 = .035). However, in the academic domain, there was a significant interaction between perspective and nationality (F (3, 78) = 3.16, p = .029, partial η2 = .108). Post hoc comparisons suggested this was driven by relatively greater TPJ activity in Chinese than American participants during classmate and best friend reflected academic appraisals (see Figure 5). A combined repeated measures ANOVA with two within-subject factors (domain, perspective) and one between-subject factor (nationality) exhibited a significant interaction between perspective and nationality (F (3, 78) = 3.43, p = .021, partial η2 = .116), but the three-way interaction between domain, perspective, and nationality was not significant (F (3, 78) = 1.33, p = .272, partial η2 = .049). There was not a significant interaction of the between-subjects factor of nationality and specific within-subjects contrast mirroring that run in the whole-brain analysis (F (1, 26) = 2.028, p = .166, partial η2 = .072).

Figure 5. Cross-National Comparisons in Right TPJ.

Comparison of mean percent signal change extracted from one of the two independent ROIs in right TPJ ([52 −50 22], defined by the meta-analysis of self/other processing in Denny et al., 2012) in American and Chinese samples. There were no significant differences in activity between direct self-appraisals in either domain, or reflected academic self-appraisals from mothers’ perspective. However, reflected academic self-appraisals from peer perspectives (best friend and classmates) engaged right TPJ significantly more in Chinese than American samples.

Discussion

This goal of this study was to further investigate the neural systems supporting self-perception in a more comprehensive manner and an understudied population, by contrasting reflected and direct self-appraisals from the social and academic domains in Chinese young adults. Results confirmed our expectation that an extended network supports reflected self-appraisal processes, including cortical midline structures anterior rostral mPFC and mPPC (both frequently implicated in self-referential processing) as well as right TPJ, pSTS, and dorsal mPFC (all regions that have been implicated in perspective-taking or mentalizing). This expansion beyond the common circumscribed network of cortical midline structures is the reason we refer to it as an “extended network.” Furthermore, TPJ was also relatively more engaged during direct appraisals of the social than academic self. In the academic domain, to the extent that reflected self-appraisals disagreed with direct self-appraisals in the academic domain, TPJ was recruited more heavily. The exploratory cross-national comparisons also suggested that during reflected self-appraisals from peer perspectives, Chinese young adults may engage TPJ more robustly than American young adults.

mPFC in Self-Appraisals

Scores of previous fMRI studies, conducted almost exclusively in adults, have targeted mPFC as a primary region supporting self-referential processing (Heatherton et al., 2006; Northoff et al., 2006; Denny et al., 2012), yet the precise functions of these areas are still subject to some debate. Our first investigation of developmental differences in the neural correlates of self-appraisal processes identified greater activity in mPFC for children than adults, which along with other results suggested that mPFC was probably not a site where self-knowledge was stored (Pfeifer, Lieberman, & Dapretto, 2007). We proposed instead that some form of reflection and integration was actively taking place – such as doing the mental “work” involved in defining the self via traits that are abstracted from autobiographical memories of many instances of behaviors – which is consistent with other functions generally assigned to anterior rostral mPFC (e.g., Christoff, Ream, Geddes, & Gabrieli, 2003; Dumontheil, Burgess, & Blakemore, 2008; Gilboa, 2004; Spreng, Mar, & Kim, 2009). These functions include integration of multiple internally-generated inputs and reflection on autobiographical memories, both of which would be useful to make higher-order generalizations about one’s own abilities and attributes from past experiences.

In other work, we also observed that activity in mPFC was maximized when making reflected self-appraisals in a domain that corresponded with the target other’s presumed sphere of significant influence (such as the social domain for a best friend; Pfeifer et al., 2009). We extended our conceptualization of mPFC functions with the idea that it may be relatively more engaged by relational self-processing, as in seeing oneself through the eyes of a close friend or relative. Perhaps to some degree, this is because individuals possess (both in number and relevancy) more autobiographical memories and other information to retrieve and integrate when the domain matches with a reflected perspective.

The current study is consistent with this more relational interpretation of how mPFC contributes to self-appraisal processes. Here, we found significantly heightened activity in mPFC during direct self-appraisals in the social domain, when compared with direct self-appraisals in the academic domain (despite the fact that average response latencies for self-evaluations were marginally faster in the academic than social domain, indicating that the effects are unlikely to be due to greater default-related activity in the social than academic domain). In China, the social domain (already inherently highly relational) is particularly interdependent, while the academic domain is characterized by relatively greater autonomy (due to Confucian traditions about learning; Li, 2001, 2002, 2003a/b, 2005, 2006; Li & Yue, 2004; Wang & Li, 2003). However, because we did not measure individual differences in self-construal style, or identification with self-reliance and independence in academics, this remains to be confirmed in future studies that do so.

TPJ in Self-Appraisals

In addition to the field’s research focus on the role of mPFC in self-referential processing, we propose that expanding beyond adult and Western samples (in whom self-evaluations are arguably most decontextualized) may better reveal important contributions to self-appraisal processes made by other brain regions – particularly TPJ. The current study adds to our previous findings that this region supports not only reflected self-appraisals, but also direct self-appraisals in some contexts (Pfeifer et al., 2009). It also conceptually replicates the recent work of others pointing to a role for TPJ in East Asian or collectivistic self-referential processing, especially in the social domain (Ma et al., 2014; Sul et al., 2012).

This study also illuminates possible functional contributions to self-appraisal processes made by TPJ. The negative correlations between activity in TPJ and agreement between direct self-appraisals and reflected self-appraisals in the academic domain shows that participants used this region more when reflected self-appraisals differed from direct self-appraisals. This is consistent with the idea that the role of TPJ in these self-appraisal contexts is to reason about others’ thoughts (specifically about the self; Saxe, 2010), a more complex task when they differ from one’s own. Given that the content of reflected self-appraisals agreed with direct self-appraisals more in the social than academic domain, it might initially seem counterintuitive that activity in TPJ during reflected academic self-appraisals increased when there was disagreement with direct academic self-appraisals. However, agreement was closer to ceiling in the social than academic domain, which may have created a restriction of range problem. This may be a function of the social and academic domains in general, or specifically in the Chinese sample. The exploratory cross-national analyses hint at the latter, because the TPJ was also significantly more active during reflected peer self-appraisals in the academic domain only in the Chinese sample – suggesting multiple cross-national differences in the neural systems supporting reflected academic self-appraisals – although the full cross-over interaction between perspective, domain, and nationality did not reach significance. Further research should attempt to replicate and explore the sources of this effect more precisely, including whether it is due in part to the different stages of post-secondary education occupied by the Chinese and American samples. Regardless, we do not propose it is the lack of agreement per se driving TPJ involvement, but rather the act of taking someone else’s perspective, whatever the cause for doing so. In other words, perspective-taking may be relatively pervasive in the social domain (across cultures and nationalities), but more variably engaged in other domains like academics.

VLPFC in Self-Appraisals

Although unexpected and unpredicted, the engagement of VLPFC when agreement was low was interesting, as this region is not typically a focus in self-referential fMRI studies. One possible interpretation is based on the strong role of VLPFC in response inhibition and other forms of self-control (Aron, Robbins, & Poldrack, 2004; Cohen & Lieberman, 2010). The negative correlations between activity in VLPFC and agreement during reflected self-appraisals may therefore suggest that one must inhibit or regulate one’s self-perceptions to the extent direct and reflected self-appraisals disagree. As a consequence, individuals who have difficulty with self-regulation (or are still developing this capacity) may exhibit greater difficulties incorporating reflected self-appraisals into their self-construals (and/or keeping them distinct).

Limitations

It should be noted again that this study was limited by not including a measure of collectivism in our sample of Chinese young adults, so any conclusions about cultural contributions are dependent on the average differences between nationalities on this dimension (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002; Ray et al., 2010). Our analysis strategy is therefore consistent with that described by Markus and Hamedani (2007; see also Zhou & Cacioppo, 2010) as the sociocultural model approach to the interdependence between sociocultural context and mind, which is particularly relevant to representations of self and others. Although this approach has been taken before with success in other cultural neuroscience studies, accounting for individual differences in the future would be ideal. For instance, specifically recruiting participants who demonstrate independent and interdependent self-construals in various domains a priori rather than post-hoc, would allow us to better understand the role that this phenomenon plays in the engagement of a more extended network beyond just cortical midline structures. Likewise, it will be vital to simultaneously test the full sociocultural model and its sensitivity to developmental stage and contexts by including many groups in the same study – participants from individualistic and collectivist cultures, at varying ages – and assessing domains with differing levels of interdependence and importance to the participants, as well as those within which participants have varying levels of experience and competence.

As mentioned previously, it is also problematic that scanner site and participant nationality could not be disentangled. This is why we recommend cautious interpretation of any cross-national comparisons. In addition, the Chinese sample was composed primarily of undergraduate students, while the American sample was composed entirely of graduate students. This may have implications for the ways in which participants valued each domain that trump contributions of nationality and/or culture. It may also have contributed to the finding of significantly greater TPJ activity in Chinese than American young adults during reflected peer academic self-appraisals. Furthermore, both of these samples were relatively small, so any assessments of individual differences and brain-behavior relationships were significantly underpowered.

Finally, the control condition (direct appraisals of participants’ best friends) was acquired entirely after all of the direct and reflected self-appraisals, which is suboptimal. One alternative would be to use a more conservative control condition, better tailored to multiple reflected-appraisals perspectives and assessed throughout the task. Another alternative would be to use a lower level control condition that is unlikely to vary across groups, such as judging a surface feature of the stimulus. Importantly, however, this limitation does not impact direct comparisons between individual conditions.

Conclusions and Future Directions

In summary, we found that Chinese young adults utilized an extended network of regions for both self-perception and social cognition during reflected self-appraisals regardless of domain, and during direct self-appraisals in an interdependent (social) domain, but not during direct self-appraisals in an independent (academic) domain. This network included the commonly engaged cortical midline structures in anterior rostral mPFC and mPPC, as well as TPJ, pSTS, and dorsal mPFC.

These findings join a growing trend in demonstrating the kind of advances in social neuroscience made possible by taking cultural and developmental approaches that are sensitive to the variability introduced by context and stage. For example, the model of an extended network for self-appraisals that has resulted from this and prior studies seems relevant to various clinical applications, in particular depression and autism (Pfeifer & Peake, 2012). First, it may prove to be important for better understanding how one may develop, as well as attempt to change, the negative self-evaluations that are persistent in depression (Northoff, 2007). Second, it also seems well-suited to address why autism spectrum disorder is associated with atypicalities in self- and social perception, and how each may influence the other’s functioning (Lombardo, Barnes, Wheelwright, & Baron-Cohen, 2007; Lombardo et al., 2010). Cutting edge studies are now beginning to assess how this extended network functions in depression and autism, both during adulthood and across development (Lemogne, Delaveau, Freton, Guionnet, & Fossati, 2012; Pfeifer et al., 2013). Therefore, this study clearly underscores the need for social neuroscientists to continue this movement of incorporating context-sensitive approaches. Ultimately, this helps to build on a model for the neural foundations of self-concept development and maintenance that is sensitive to national, ethnic, and cultural contexts as well as domain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Project 111 of the Ministry of Education in China as well as the FPR-UCLA Center for Culture, Brain, & Development. JHP was supported by R01 MH107418. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the Developmental Social Neuroscience lab at the University of Oregon for assisting with data analysis. We also thank Gordon Hall for his helpful comments on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Participants were specifically told to focus on their current university experiences, rather than memories from childhood. When making reflected self-appraisals from the perspective of their best friend, they were told to choose their best (same-gender) friend in their cohort at the university. When making reflected self-appraisals from the perspective of their classmates, participants were told to think about the other students in their university cohort.

References

- Ames DL, & Fiske ST (2010). Cultural neuroscience. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 13, 72–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2010.01301.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Robbins TW, & Poldrack RA (2004). Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JM (1895). Mental development of the child and the race: Methods and processes. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Tice DM, & Hutton DG (1989). Self-presentational motivations and personality differences in self-esteem. Journal of Personality, 57, 547–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb02384.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bohrnstedt GW, & Felson RB (1983). Explaining the relationships among children’s actual and perceived performances and self-esteem: A comparison of several causal models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 43–56. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.43 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brett M, Anton JL, Valabregue R, & Poline JB (2002). Region of interest analysis using an SPM toolbox. Neuroimage, 16, 1140–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Leung MC, Gest SD, & Cairns BD (1996). A brief method for assessing social development: Structure, reliability, stability, and developmental validity of the Interpersonal Competence Scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 725–736. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00004-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DW (1997). Self-concept domains and global self-worth among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Personality and Individual Differences, 22, 511–520. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00223-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DW (2002). Perceived domain-specific competence and global self-worth of primary students in Hong Kong. School Psychology International, 23, 355–368. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.43 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PHA, Wagner DD, Kelley WM, & Heatherton TF (2015). Activity in cortical midline structures is modulated by self-construal changes during acculturation. Culture and Brain, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s40167-015-0026-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, & Ambady N. (2007). Cultural neuroscience: Parsing universality and diversity across levels of analysis. In Kitayama S. & Cohen D(Eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Harada T, Komeda H, Li Z, Mano Y, Saito D, Parrish TB, Sadato N, & Iidaka T. (2009). Neural basis of individualistic and collectivist views of self. Human Brain Mapping, 30, 2813–2829. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Harada T, Komeda H, Li Z, Mano Y, Saito D, Parrish TB, Sadato N, & Iidaka T. (2010). Dynamic cultural influences on neural representations of the self. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22, 1–11. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Cheon BK, Pornpattananangkul N, Mrazek AJ, & Blizinsky KD (2013). Cultural neuroscience: Progress and promise. Psychological Inquiry, 24(1), 1–19. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2013.752715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoff K, Ream JM, Geddes LPT, & Gabrieli JD (2003). Evaluating self-generated information: Anterior prefrontal contributions to human cognition. Behavioral Neuroscience, 117, 1161–1168. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JR, & Lieberman MD (2010). The common neural basis of exerting self-control in multiple domains. In Trope Y, Hassin R, & Ochsner KN (eds.) Self-control (pp. 141–160). Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195391381.003.0008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CH (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- D’Argembeau A, Ruby P, Collette F, Degueldre C, Balteau E, Luxen A, et al. (2007). Distinct regions of the medial prefrontal cortex are associated with self referential processing and perspective taking. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19, 935–944. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.6.935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denissen JJA, Zarrett NR, & Eccles JS (2007). I like to do it, I’m able, and I know I am: Longitudinal couplings between domain-specific achievement, self-concept, and interest. Child Development, 78, 430–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny BT, Kober H, Wager TD, & Ochsner KN (2012). A meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of self-and other judgments reveals a spatial gradient for mentalizing in medial prefrontal cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(8), 1742–1752. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumontheil I, Burgess PW, & Blakemore SJ (2008). Development of rostral prefrontal cortex and cognitive and behavioural disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol, 50, 168–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02026.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Midgley C, Wigfield A, Bechanan CM, Reuman D, Flanagan C, & Iver DM (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48, 90–101. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Price CJ, Buchel C, & Worsley KJ (1999). Multisubject fMRI studies and conjunction analyses. Neuroimage, 10, 385–396. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner WL, Gabriel S, Lee AY (1999): “I” value freedom but “we” value relationships: self construal priming mirrors cultural differences in judgment. Psychological Science, 10(4), 321–326. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gieve S, & Clark R. (2005). “The Chinese approach to learning”: Cultural trait or situated response? The case of a self-directed learning programme. System, 33, 261–276. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2004.09.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilboa A. (2004). Autobiographical and episodic memory - one and the same? Evidence from prefrontal activation in neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychologia, 42, 1336. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, & Northoff G. (2008). Culture-sensitive neural substrates of human cognition: A transcultural neuroimaging approach. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9, 646–54. doi: 10.1038/nrn2456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, & Northoff G. (2009). Understanding the self: A cultural neuroscience approach. Progress in Brain Research, 178, 203–212. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17814-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Northoff G, Vogeley K, Wexler BE, Kitayama S, & Varnum ME (2013). A cultural neuroscience approach to the biosocial nature of the human brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 335–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-071112-054629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. (1999). The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press. doi:1999-02441-000 [Google Scholar]

- Hau KT, & Salili F. (1996) Prediction of academic performance among Chinese students: Effort can compensate for lack of ability. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65, 83–94. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1996.0008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Wyland CL, Macrae CN, Demos KE, Denny BT, & Kelley WM (2006). Medial prefrontal activity differentiates self from close others. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 1, 18–25. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, & Hamamura T. (2007). In search of East Asian self-enhancement. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(1), 4–27. doi: 10.1177/1088868306294587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, Fu G, & Lee K. (2008). Reasoning about the disclosure of success and failure to friends among children in the United States and China. Developmental Psychology, 44(4), 908. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hymel S, LeMare L, Ditner E, & Woody EZ (1999). Assessing self-concept in children: Variations across self-concept domains. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45, 602–623. doi:2000-08175-003 [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski KF, Moore WE, Merchant JS, Kahn LE, & Pfeifer JH (2014). But do you think I’m cool?: Developmental differences in striatal recruitment during direct and reflected social self-evaluations. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 8, 40–54. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagawa C, Cross SE, & Markus HR (2001). “Who am I?” The cultural psychology of the conceptual self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 27, 90–103. doi: 10.1177/0146167201271008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U. (1997). Asian collectivism: An indigenous perspective. In Kao H. & Sinha D. (Eds.), Asian perspectives on psychology, Cross-Cultural Research and Methodology Series, Vol. 19, (pp. 147–163). New Delhi, India: Sage. doi:1997-36359-008 [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, & Tompson S. (2010). Envisioning the future of cultural neuroscience. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 13, 92–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2010.01304.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, & Park J. (2010). Cultural neuroscience of the self: Understanding the social grounding of the brain. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 5, 111–129. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IA, & Preacher KJ (2013, September). Calculation for the test of the difference between two dependent correlations with one variable in common [Computer software]. Available from http://quantpsy.org.

- Legrand D, & Ruby P. (2009). What is self-specific? Theoretical investigation and critical review of neuroimaging results. Psychological Review, 116, 252–282. doi: 10.1037/a0014172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemogne C, Delaveau P, Freton M, Guionnet S, & Fossati P. (2012). Medial prefrontal cortex and the self in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(1), e1–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. (2001). Chinese conceptualization of learning. Ethos, 29, 111–137. doi: 10.1525/eth.2001.29.2.111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. (2002). A cultural model of learning: Chinese “heart and mind for wanting to learn.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33, 248–269. doi: 10.1177/0022022102033003003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. (2003a). The core of Confucian learning. American Psychologist, 58, 146–147. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.2.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. (2003b). U. S. and Chinese cultural beliefs about learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 258–267. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. (2005). Mind or virtue: Western and Chinese beliefs about learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 190–194. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00362.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. (2006). Self in learning: Chinese adolescents’ goals and sense of agency. Child Development, 77, 482–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00883.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, & Yue XD (2004). Self in learning among Chinese adolescents. In Mascolo MF & Li J. (Eds.), Culture and developing selves: Beyond dichotomization. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development, No. 104. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. doi: 10.1002/cd.102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo MV, Barnes JL, Wheelwright SJ, & Baron-Cohen S. (2007). Self-referential cognition and empathy in autism. PLoS ONE, 2(9), e883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo MV, Chakrabarti B, Bullmore ET, Sadek SA, Pasco G, Wheelwright SJ, Suckling J, MRC AIMS Consortium, & Baron-Cohen S. (2010). Atypical neural self-representation in autism. Brain, 133, 611–624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losin EAR, Dapretto M, & Iacoboni M. (2010). Culture and neuroscience: Additive or synergistic? Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 5, 148–158. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Bang D, Wang C, Allen M, Frith C, Roepstorff A, & Han S. (2014). Sociocultural patterning of neural activity during self-reflection. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9, 73–80. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malafouris L. (2010). The brain–artefact interface (BAI): A challenge for archaeology and cultural neuroscience. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 5, 264–273. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, & Kitayama S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, & Hamedani M. (2007). Sociocultural psychology: The dynamic interdependence among self systems and social systems. In: Kitayama S. & Cohen D. (Eds.), Handbook of Cultural Psychology (pp. 3–39). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW (1988). The Self Description Questionnaire (SDQ): A theoretical and empirical basis for the measurement of multiple dimensions of preadolescent self-concept: A test manual and a research monograph. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Craven RG, & Debus RL (1991). Self-concepts of young children aged 5 to 8: Their measurement and multidimensional structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T, & Nisbett RE (2006). Culture and change blindness. Cognitive Science, 30(2), 381–399. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog0000_63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]