Key Points

Question

Among extremely preterm infants fed minimal maternal milk, does feeding of donor human milk compared with preterm formula during the birth hospitalization result in improved neurodevelopmental outcomes?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial, the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development adjusted mean cognitive score was 80.7 (measured at 22-26 months’ corrected age) for infants fed donor human milk vs 81.1 for infants fed preterm formula (adjusted between-group mean difference, −0.77 [95% CI, −3.93 to 2.39]), which was not a significant difference. The adjusted mean language and motor scores also did not differ.

Meaning

Among extremely preterm infants, donor milk feeding did not result in different 2-year neurodevelopmental outcomes compared with preterm formula feeding.

Abstract

Importance

Maternal milk feeding of extremely preterm infants during the birth hospitalization has been associated with better neurodevelopmental outcomes compared with preterm formula. For infants receiving no or minimal maternal milk, it is unknown whether donor human milk conveys similar neurodevelopmental advantages vs preterm formula.

Objective

To determine if nutrient-fortified, pasteurized donor human milk improves neurodevelopmental outcomes at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age compared with preterm infant formula among extremely preterm infants who received minimal maternal milk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Double-blind, randomized clinical trial conducted at 15 US academic medical centers within the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Infants younger than 29 weeks 0 days’ gestation or with a birth weight of less than 1000 g were enrolled between September 2012 and March 2019.

Intervention

Preterm formula or donor human milk feeding from randomization to 120 days of age, death, or hospital discharge.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (BSID) cognitive score measured at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age; a score of 54 (score range, 54-155; a score of ≥85 indicates no neurodevelopmental delay) was assigned to infants who died between randomization and 22 to 26 months’ corrected age. The 24 secondary outcomes included BSID language and motor scores, in-hospital growth, necrotizing enterocolitis, and death.

Results

Of 1965 eligible infants, 483 were randomized (239 in the donor milk group and 244 in the preterm formula group); the median gestational age was 26 weeks (IQR, 25-27 weeks), the median birth weight was 840 g (IQR, 676-986 g), and 52% were female. The birthing parent’s race was self-reported as Black for 52% (247/478), White for 43% (206/478), and other for 5% (25/478). There were 54 infants who died prior to follow-up; 88% (376/429) of survivors were assessed at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age. The adjusted mean BSID cognitive score was 80.7 (SD, 17.4) for the donor milk group vs 81.1 (SD, 16.7) for the preterm formula group (adjusted mean difference, −0.77 [95% CI, −3.93 to 2.39], which was not significant); the adjusted mean BSID language and motor scores also did not differ. Mortality (death prior to follow-up) was 13% (29/231) in the donor milk group vs 11% (25/233) in the preterm formula group (adjusted risk difference, −1% [95% CI, −4% to 2%]). Necrotizing enterocolitis occurred in 4.2% of infants (10/239) in the donor milk group vs 9.0% of infants (22/244) in the preterm formula group (adjusted risk difference, −5% [95% CI, −9% to −2%]). Weight gain was slower in the donor milk group (22.3 g/kg/d [95% CI, 21.3 to 23.3 g/kg/d]) compared with the preterm formula group (24.6 g/kg/d [95% CI, 23.6 to 25.6 g/kg/d]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among extremely preterm neonates fed minimal maternal milk, neurodevelopmental outcomes at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age did not differ between infants fed donor milk or preterm formula.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01534481

This randomized clinical trial compares the effect of donor human milk on neurodevelopmental outcomes at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age compared with preterm infant formula among extremely preterm infants who received minimal maternal milk.

Introduction

Extremely preterm infants are at risk for neurodevelopmental impairment due to postnatal events such as intraventricular hemorrhage or periventricular leukomalacia,1 sepsis,2 necrotizing enterocolitis,3 bronchopulmonary dysplasia,4 and poor growth.5 Interventions to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes are needed. Maternal milk intake has been associated with decreased risk of sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis, and bronchopulmonary dysplasia.6,7

Among preterm infants, maternal milk feeding during the birth hospitalization has been associated with better neurodevelopmental outcomes than formula.8,9,10 Evidence for the benefits of maternal milk is based primarily on observational studies because randomized clinical trials would be unethical. A dose-response relationship between maternal milk intake and higher developmental scores was reported at both 18 months’ corrected age and 30 months’ corrected age in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Glutamine Study.9,10 Pasteurized donor human milk is recommended by multiple public health and professional organizations11,12,13,14 as the preferred diet when maternal milk is unavailable. However, there is limited evidence on the neurodevelopmental effects of donor milk compared with infant formula.15

Given the observed benefits of maternal milk, this randomized clinical trial tested the hypothesis that use of donor milk compared with formula in extremely preterm infants who received no or minimal maternal milk during hospitalization would result in better neurodevelopmental outcomes (primarily determined using the third edition of the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development16 [BSID] cognitive score measured at 22-26 months’ corrected age).

Methods

Study Design and Oversight

The MILK trial was a pragmatic, double-blind, randomized clinical trial comparing the use of donor milk vs preterm formula that was conducted at 15 centers within the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. The Neonatal Research Network is a group of US academic medical centers selected every 5 to 7 years through a competitive process to collaboratively conduct observational and interventional studies in neonates.

Infants were enrolled from September 7, 2012, to March 13, 2019; follow-up visits at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age were completed on November 15, 2021. The trial protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each center and written parental consent was obtained. The trial protocol appears in Supplement 1. The data safety and monitoring committee reviewed prespecified safety outcomes (necrotizing enterocolitis, intestinal perforation, culture-proven late-onset sepsis or meningitis, hospital-acquired viral infection, and death after randomization) when 25%, 50%, and 75% of planned status reporting for 670 participants was reached. Pocock bounds were used to construct stopping rules for safety. Based on group sequential monitoring for these 3 safety assessments at 25%, 50%, and 75% of planned status reporting, the associated P value was .02 for each assessment.

Participants

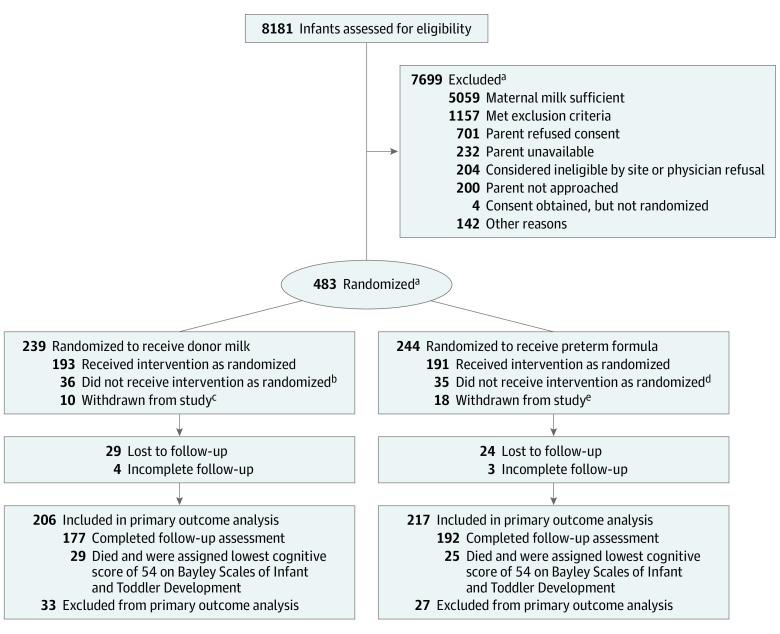

Infants younger than 29 weeks 0 days’ gestation or with a birth weight of less than 1000 g admitted to Neonatal Research Network centers before 7 days of age were eligible for enrollment if (1) the infant’s birthing parent never initiated lactation; (2) lactation was initiated, but the mother ceased expressing milk prior to 21 days; or (3) the milk supply was minimal (mean milk volume ≤3 oz/d over 5 days) from 7 to 21 days after birth (Figure). Infants could be randomized anytime from birth to 21 days if maternal milk criteria were met.

Figure. Recruitment, Randomization, and Patient Flow in the MILK Trial.

aOne infant who was ineligible was randomized.

bThere were missing data for 3 infants, 17 were fed an open-label diet but resumed the study diet, and 16 were switched permanently to an open-label diet.

cTwo infants were too unstable to continue per the physician, 4 were withdrawn at parental request, 3 were withdrawn at physician request, and 1 was withdrawn for an unknown reason.

dThere were missing data for 1 infant, 25 were fed an open-label diet but resumed the study diet, 8 were switched permanently to an open-label diet, and 1 received a diet that was prepared incorrectly.

eOne infant was too unstable to continue per the physician, 8 were withdrawn at physician request, 7 were withdrawn at parental request, and 2 were withdrawn for unknown reasons.

The randomization procedure used a permutated block design; infants were stratified by center and birth weight (≤750 g, >750 g). Multiple gestation infants were randomized individually. Prior to enrollment, infants were fed according to center practice and data regarding the type and amount of milk (maternal, donor, or formula) were not collected.

Infants were excluded if they had chromosomal anomalies, congenital heart disease, disorders known to affect feeding, intrauterine infections, prior necrotizing enterocolitis or spontaneous intestinal perforation, or terminal illness. Planned subgroups of infants receiving no maternal milk (sole diet) and minimal maternal milk (primary diet) were recruited. Investigators, medical teams, outcome examiners, and parents were blinded to the diet intervention.

Maternal race and ethnicity were collected from medical records to assess generalizability to other populations; this information was self-identified from a list of options.

Diet Intervention

Infants in the no maternal milk subgroup received a study diet for all feedings from randomization to hospital discharge, death, or 120 days of age, whichever occurred earliest. The infants in the minimal maternal milk subgroup received any minimal maternal milk available and a study diet for the remainder of feedings from randomization through status checks (hospital discharge, death, or 120 days of age, whichever occurred earliest).

Donor milk was obtained from banks within the Human Milk Banking Association of North America. Preterm infant formula, bovine human milk fortifier, and other dietary supplements were provided by centers per standard practice. No participating center used a fortifier based on human milk.

This study was designed to be pragmatic. Only the base diet (preterm formula or donor human milk) was standardized. The feeding initiation, nutrient fortification practices, and advancement protocols were not standardized. Each center created a set of stepwise-paired study diet recipes that represented their standard human milk fortification progression and formula product use.

To provide adequate protein for the donor milk group, fortified donor milk recipes were required to provide an estimated 2.8 g/dL to 3.0 g/dL of protein using commercially available fortifiers or protein supplements. Unfortified donor milk protein content was estimated to be 0.8 g/dL to 0.9 g/dL; the nutrient content of donor milk was not measured. Treating clinicians made decisions regarding initiation and advancement of feeding and the timing and contents of fortification. For example, clinicians would not know which base diet an infant was receiving. However, the clinician would know the infant would receive 24 kcal/oz of preterm formula (the hospital’s typical brand) or 24 kcal/oz of donor human milk (fortified with bovine human milk fortifier) if they had ordered the step 2 diet.

Feedings were prepared daily by study staff. A 24-hour supply of feedings was delivered to each infant’s bedside and the infants were fed by nurses or family members. Medfusion 3500 syringe pumps (version 5.0; Biomedix Medical Inc) were used to deliver feedings by nasogastric or orogastric tube, or feedings were administered by low-gravity bolus per clinician preference. Amber-tinted oral syringes and storage bottles were used to mask the appearance of the study diet. Infants were transitioned from the study diet to the preterm formula chosen by the clinician 1 week prior to anticipated hospital discharge or at 120 days if still hospitalized.

Growth Measurements and Nutritional Data

Infant weight was recorded weekly and obtained from the medical records. Infant length and head circumference were measured by study personnel every 2 weeks. Feeding intolerance (defined as withholding of feedings for >24 hours) was recorded weekly. For infants in both groups, receipt of any maternal milk was recorded weekly as any or none.

Neurodevelopmental Follow-Up

Participants were assessed at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age. The BSID and a standardized neurological examination for cerebral palsy, which included the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS), were conducted. Examiners were blinded to the diet intervention and were certified by the Neonatal Research Network annually for interrater reliability and accuracy using published methods.17

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was the cognitive score on the BSID.16 Infants who died between randomization and 22 to 26 months’ corrected age and those unable to complete the BSID due to disability were assigned a score of 54 (score range, 54-155; a score of ≥85 indicates no neurodevelopmental delay).

Secondary outcomes included (1) BSID language score (score range, 44-155) and BSID motor score (score range, 49-155) (a score of ≥85 indicates no neurodevelopmental delay for both the BSID language and motor scores), (2) moderate or severe cerebral palsy (GMFCS score ≥2), and (3) moderate or severe neurodevelopmental impairment (BSID cognitive score <85; GMFCS score ≥2; visual acuity <20/200 in both eyes; or profound hearing loss requiring amplification in both ears18). The BSID is standardized with a mean score of 100 (SD, 15) for all scores (cognitive, language, and motor scores).

Other secondary outcomes included growth (measured during the intervention), late-onset sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis, and death. Growth was assessed by change in weight, length, and head circumference between randomization and status (hospital discharge, death, or 120 days of age, whichever occurred earliest) using z scores from the Fenton growth chart.19 Late-onset sepsis or meningitis was defined as clinical illness with positive blood culture or cerebrospinal fluid culture after 72 hours of age that was treated with antibiotics for at least 5 days. Necrotizing enterocolitis was defined as Bell stage 2 or greater.20,21

Statistical Analysis

The outcome analyses by treatment group were adjusted for birth weight stratum, academic medical center, and age (in days) at randomization. Linear regression was used for the continuous outcomes to obtain the adjusted between-group differences in mean BSID scores. Robust Poisson regression was used for the binary and categorical outcomes to obtain adjusted between-group risk difference estimates. Due to the use of imputed scores for infants who died, median regression was also performed for BSID scores, which did not differ from the linear regression results. All models converged without unusually high SEs for any parameters. Strata ranged from 2 to 96 infants per stratum (median, 11 infants [IQR, 6-17 infants]). The statistical analysis plan appears in Supplement 1.

Planned subgroup analyses were performed on the no maternal milk subgroup for both the primary outcome and all listed secondary outcomes. Treatment heterogeneity was assessed through interaction tests by diet group and by all randomization strata and sex. No significant interactions were identified. The secondary outcomes and subgroup analyses were considered exploratory and were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

The analyses of growth outcomes excluded infants who died during the birth hospitalization. The sample size calculation assumed 15% of infants would die after randomization, a follow-up of 90%, and a conservative estimate for the SD of 20 points for the BSID scores. It was estimated a target sample size of 670 infants (502 evaluated at 22-26 months’ corrected age) would result in 80% power to detect a 5-point difference in the BSID cognitive score. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) was used for the analyses; all analyses were 2-sided with an α level of .05.

Results

Of the 1965 eligible infants identified, 483 (25%) were randomized (239 in the donor milk group and 244 in the preterm formula group) (Figure). The median gestational age was 26 weeks (IQR, 25-27 weeks), the median birth weight was 840 g (IQR, 676-986 g), and 52% were female. The birthing parent’s race was self-reported as Black for 52% (247/478), White for 43% (206/478), and other for 5% (25/478). There were 54 infants who died prior to follow-up; 88% of survivors (376/429) were assessed at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age. The baseline characteristics were similar between the groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population.

| No. (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|

| Donor milk (n = 239) | Preterm formula (n = 244) | |

| Gestational age, median (IQR), wk | 26 (25-27) | 26 (25-27) |

| Weight at birth, median (IQR), g | 840 (677-1001) | 840 (673-968) |

| Infant sexb | ||

| Female | 133 (56) | 116 (48) |

| Male | 106 (44) | 128 (52) |

| Multiple birth | 50 (21) | 48 (20) |

| Use of antenatal steroids | 206 (87) | 203 (85) |

| Maternal age, median (IQR), y | 27 (23-33) | 28 (23-33) |

| Maternal ethnicityc | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 37 (15) | 31 (13) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 201 (84) | 212 (87) |

| Not known or not reported | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| Maternal racec | ||

| Black | 126 (54) | 121 (50) |

| White | 98 (42) | 108 (44) |

| Otherd | 11 (4.7) | 14 (5.8) |

| Maternal public insurancee | 178 (75) | 184 (77) |

| Maternal education | ||

| <High school diploma | 64 (29) | 57 (25) |

| High school diploma | 82 (37) | 93 (41) |

| >High school diploma | 74 (34) | 77 (34) |

| Age at randomization, median (IQR), d | 16 (9-20) | 16 (10-20) |

Unless otherwise indicated.

Assigned at birth by treating medical personnel. Data were obtained from the medical records.

The categories were created by the Neonatal Research Network. Data were obtained from the infant or maternal medical record.

Includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and more than 1 race. This category was combined to preserve patient anonymity due to the low numbers of individuals in these categories.

Includes Medicare, Medicaid, state-funded programs, and insurance purchased through the Affordable Care Act marketplace.

There were 114 infants who did not receive maternal milk and 370 infants who received minimal maternal milk. Enrollment was stopped after randomization of 483 infants due to declining enrollment and loss of equipoise among participating centers. There also has been increasing use of donor milk in the Neonatal Research Network over time.

Diet Intervention

Enteral feedings were initiated at a median of 4 days (IQR, 3-5 days) in both groups. Infants were randomized at a median age of 16 days (IQR, 10-20 days) and received the study diet for a median of 56 days (IQR, 34-75 days). Discontinuation of the study diet occurred at a median of 37 weeks’ postmenstrual age (IQR, 35-40). After randomization, 53% (255/483) of infants did not receive maternal milk. The remaining 43% (228/483) of infants had some maternal milk recorded for a median of 1 week (IQR, 0-2 weeks) in the donor milk group and for a median of 0 weeks (IQR, 0-2 weeks) in the preterm formula group.

Growth

Weight gain was slower in the donor milk group (22.3 g/kg/d [95% CI, 21.3 to 23.3 g/kg/d]) compared with the preterm formula group (24.6 g/kg/d [95% CI, 23.6 to 25.6 g/kg/d]) (Table 2). At the end of the study, the mean weight in the donor milk group was 143 g lower than the preterm formula group. Infants in both groups had similar weight, length, and head circumference at study entry (range of mean z scores, −1.46 to −0.90). Length gain and head circumference growth did not differ between the groups during the study.

Table 2. Study Diet Information and Growth Outcomes.

| Donor milk | Preterm formula | Adjusted between-group difference, mean (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of infants | Mean (SD) [95% CI]a | No. of infants | Mean (SD) [95% CI]a | ||

| Information on study diet, mean (95% CI) a | |||||

| Study diet intake | |||||

| Total duration, d | 233 | 54.4 (50.9 to 58.0) | 242 | 54.5 (51.0 to 58.1) | −0.14 (−5.01 to 4.73) |

| Postmenstrual age at last intake, wkb | 237 | 36.6 (36.1 to 37.2) | 240 | 36.7 (36.2 to 37.2) | −0.10 (−0.79 to 0.60) |

| Enteral feedings withheld for >24 h during at least 1 wk, No. (%) | 237 | 107 (46) | 240 | 122 (50) | −2 (−10 to 7)c |

| Any maternal milk intake after randomization, wk | 239 | 1.73 (1.35 to 2.10) | 244 | 1.64 (1.27 to 2.01) | 0.09 (−0.41 to 0.58) |

| At first enteral feeding | |||||

| Postmenstrual age, wkb | 239 | 26.5 (26.3 to 26.8) | 243 | 26.7 (26.5 to 26.9) | −0.17 (−0.44 to 0.09) |

| Day of life | 239 | 4.31 (3.84 to 4.77) | 243 | 4.72 (4.17 to 5.27) | −0.40 (−1.09 to 0.30) |

| At first oral feeding | |||||

| Postmenstrual age, wkb | 239 | 34.0 (33.6 to 34.5) | 244 | 34.4 (33.9 to 34.9) | −0.29 (−0.90 to 0.32) |

| Postnatal age, dd | 239 | 54.2 (50.4 to 58.1) | 244 | 57.6 (53.8 to 61.3) | −2.10 (−6.62 to 2.43) |

| Total parenteral nutrition, d | 239 | 16 (11 to 28) | 244 | 16 (12 to 29) | −1.57 (−4.80 to 1.66) |

| Anthropometrics at study entry | |||||

| Weight, g | 235 | 896 (245) [864 to 927] | 244 | 890 (234) [861 to 920] | 7.22 (−19.2 to 33.7) |

| Length, cm | 230 | 34.2 (3.4) [33.7 to 34.6] | 235 | 34.3 (3.4) [33.9 to 34.8] | −0.14 (−0.55 to 0.27) |

| Head circumference, cm | 235 | 23.6 (2.1) [23.4 to 23.9] | 239 | 23.8 (2.4) [23.5 to 24.1] | −0.15 (−0.44 to 0.15) |

| Z score for age | |||||

| Weight | 235 | −0.90 (0.7) [−0.99 to −0.81] | 244 | −0.98 (0.61) [−1.06 to −0.91] | 0.09 (−0.02 to 0.19) |

| Length | 230 | −0.99 (1.0) [−1.12 to −0.85] | 235 | −1.01 (1.1) [−1.15 to −0.88] | 0.02 (−0.14 to 0.18) |

| Head circumference | 235 | −1.46 (1.1) [−1.60 to −1.33] | 239 | −1.42 (1.3) [−1.59 to −1.26] | −0.02 (−0.21 to 0.16) |

| Anthropometrics at hospital discharge e | |||||

| Weight, g | 235 | 2589 (806) [2485 to 2693] | 243 | 2726 (812) [2623 to 2828] | −143 (−280 to −5.10) |

| Length, cm | 213 | 44.3 (4.2) [43.8 to 44.9] | 224 | 44.9 (4.1) [44.4 to 45.5] | −0.62 (−1.35 to 0.12) |

| Head circumference, cm | 221 | 32.0 (3.7) [31.5 to 32.5] | 227 | 32.4 (2.8) [32.0 to 32.8] | −0.50 (−1.07 to 0.08) |

| Z score for age | |||||

| Weight | 235 | −1.33 (1.2) [−1.48 to −1.18] | 243 | −1.07 (1.0) [−1.20 to −0.94] | −0.26 (−0.44 to −0.09) |

| Length | 213 | −1.91 (1.4) [−2.10 to −1.72] | 224 | −1.80 (1.4) [−1.98 to −1.62] | −0.11 (−0.34 to 0.12) |

| Head circumference | 221 | −1.13 (1.97) [−1.39 to −0.87] | 227 | −0.97 (1.24) [−1.13 to −0.81] | −0.17 (−0.45 to 0.11) |

| Growth during study | |||||

| Weight gain, g/kg/d | 235 | 22.3 (7.8) [21.3 to 23.3] | 243 | 24.6 (8.1) [23.6 to 25.6] | −2.34 (−3.63 to −1.05) |

| Length gain, cm/wk | 209 | 0.84 (0.2) [0.80 to 0.87] | 216 | 0.86 (0.3) [0.82 to 0.90] | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) |

| Head circumference gain, cm/wk | 218 | 0.70 (0.3) [0.66 to 0.73] | 223 | 0.71 (0.2) [0.68 to 0.73] | −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.03) |

| Z score for change | |||||

| Weight | 235 | −0.43 (0.9) [−0.54 to −0.32] | 243 | −0.09 (0.9) [−0.20 to 0.02] | −0.35 (−0.50 to −0.20) |

| Length | 209 | −0.93 (1.12) [−1.08 to −0.77] | 216 | −0.77 (1.20) [−0.93 to −0.61] | −0.13 (−0.34 to 0.08) |

| Head circumference | 218 | 0.39 (1.98) [0.12 to 0.65] | 223 | 0.44 (1.34) [0.26 to 0.62] | −0.08 (−0.39 to 0.22) |

Unless otherwise indicated.

Postmenstrual age calculated as gestational age at birth plus postnatal age in weeks.

Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) expressed as percentages.

Postnatal age was defined as age since birth in days or weeks.

Or at 120 days of age, whichever came first.

Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 22 to 26 Months’ Corrected Age

Of 483 infants, 54 died prior to follow-up (the BSID scores were imputed) and 53 were lost to follow-up (29 in the donor milk group vs 24 in the preterm formula group) and were excluded from the analysis (Figure). There were 369 infants who underwent follow-up. The adjusted mean BSID cognitive score was 80.7 (SD, 17.4) in the donor milk group vs 81.1 (SD, 16.7) in the preterm formula group (adjusted between-group mean difference, −0.77 [95% CI, −3.93 to 2.39]).

The BSID motor and language scores did not significantly differ between groups (Table 3). Among infants with BSID cognitive scores of less than 85, 46% (95/206) were in the donor milk group vs 49% (106/217) in the preterm formula group (adjusted between-group risk difference, −3% [95% CI, −12% to 6%]). Among infants with BSID cognitive scores of less than 70, 25% (51/206) were in the donor milk group vs 24% (51/217) in the preterm formula group (adjusted between-group risk difference, 1% [95% CI, −3% to 4%]).

Table 3. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 22 to 26 Months’ Corrected Age.

| Donor milk | Preterm formula | Adjusted between-group difference (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| BSID cognitive score, mean (SD) [No.]b | 80.7 (17.4) [206] | 81.1 (16.7) [217] | MD, −0.77 (−3.93 to 2.39) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| BSID score, mean (SD) [No.]b | |||

| Language | 76.7 (19.6) [203] | 75.8 (18.6) [212] | MD, 0.68 (−2.89 to 4.24) |

| Motor | 80.3 (21.6) [202] | 80.1 (19.9) [213] | MD, −0.38 (−4.28 to 3.52) |

| BSID score for no maternal milk subgroup, mean (SD)b | |||

| Cognitive | 80.2 (18.0) | 80.9 (18.2) | MD, −1.61 (−8.97 to 5.74) |

| Language | 78.9 (22.2) | 77.3 (19.8) | MD, 1.16 (−7.04 to 9.37) |

| Motor | 77.7 (22.8) | 77.8 (20.5) | MD, −1.31 (−10.2 to 7.58) |

| BSID score <85, No./total (%)c | |||

| Cognitive | 95/206 (46) | 106/217 (49) | RD, −3 (−12 to 6) |

| Language | 115/203 (57) | 134/212 (63) | RD, −11 (−20 to −1) |

| Motor | 90/202 (45) | 102/213 (48) | RD, −3 (−13 to 6) |

| BSID score <70, No./total (%)d | |||

| Cognitive | 51/206 (25) | 51/217 (24) | RD, 1 (−3 to 4)e |

| Language | 64/203 (32) | 72/212 (34) | RD, −4 (−9 to 0.4)e |

| Motor | 49/202 (24) | 58/213 (27) | RD, −5 (−10 to 1)e |

| Neurodevelopmental impairment, No./total (%) | |||

| Moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairmentf | 89/177 (50) | 98/189 (52) | RD, −2 (−12 to 8) |

| Moderate to severe cerebral palsyg | 14/185 (7.6) | 20/197 (10) | RD, −2 (−7 to 2)e |

| Any severity level of cerebral palsyh | 28/185 (15) | 40/197 (20) | RD, −5 (−10 to −0.2)e |

| Severe visual impairmenti | 4/189 (2.1) | 2/200 (1) | NAj |

| Severe hearing impairmentk | 6/190 (3.2) | 7/199 (3.5) | NAj |

| Sensitivity analysis l | |||

| BSID score, mean (SD) [No.] | |||

| Cognitive | 85.1 (14.8) [185] | 84.7 (14.3) [192] | MD, 0.12 (−2.80 to 3.05) |

| Language | 81.8 (16.3) [185] | 79.8 (16.0) [192] | MD, 1.81 (−1.45 to 5.06) |

| Motor | 86.4 (16.9) [185] | 84.8 (15.9) [192] | MD, 0.95 (−2.46 to 4.36) |

Abbreviations: BSID, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development; MD, mean difference; NA, not available; RD, risk difference.

From linear or robust Poisson regression models. Adjusted for birth weight stratum (<751 g, 751-1000 g), day of life at randomization, and study center. The adjusted risk difference (95% CI) expressed as percentages.

Deaths were assigned the lowest values possible: 54 for cognitive score (score range, 54-155), 44 for language score (score range, 44-155), and 49 for motor score (score range, 49-155). A score of 85 or higher indicates no neurodevelopmental delay. The BSID is standardized with a mean score of 100 (SD, 15) for all scores (cognitive, language, and motor scores).

A score of less than 85 indicates moderate impairment (score range, 70-84).

A score of less than 70 indicates severe impairment.

Due to sparse data, robust Poisson generalized estimating equation models were used with clustering for center.

Had BSID16 cognitive score of less than 85, moderate or severe cerebral palsy, or severe visual or hearing impairment.18

Had a Gross Motor Function Classification System score of 2 or greater.

Had a Gross Motor Function Classification System score of 1 or greater.

Visual acuity less than 20/200 in both eyes.

The adjusted risk difference is not available because the model did not converge due to sparse data (even after clustering for center).

Profound hearing loss requiring amplification in both ears.18

Includes survivors only.

The prevalence and severity of neurodevelopmental impairment did not significantly differ between groups (Table 3). In the sensitivity analysis, which excluded 54 infants who died, the mean BSID cognitive score was 85.1 (SD, 14.8) in the donor milk group vs 84.7 (SD, 14.3) in the preterm formula group (adjusted between-group mean difference, 0.12 [95% CI, −2.80 to 3.05) (Table 3 and eTable in Supplement 2).

The categorization of BSID scores by less than 85 and less than 70 revealed no significant between-group differences (Table 3). Among the 114 infants who did not receive maternal milk, the cognitive score was 80.2 (SD, 18.0) in the donor milk group vs 80.9 (SD, 18.2) in the preterm formula group (adjusted between-group mean difference, −1.61 [95% CI, −8.97 to 5.74]; Table 3).

Exploratory analyses of cognitive score by stratification variables were conducted (eFigure in Supplement 2). These analyses revealed no significant relationships between cognitive score and birth weight stratum, Neonatal Research Network center, time of randomization, or infant sex.

Mortality and In-Hospital Morbidity

The outcome of death prior to hospital discharge occurred in 10% of infants (24/239) in the donor milk group vs 7.4% of infants (18/244) in the preterm formula group (Table 4). The outcome of death prior to follow-up occurred in 13% of infants (29/231) in the donor milk group vs 11% of infants (25/233) in the preterm formula group (adjusted between-group risk difference, −1% [95% CI, −4% to 2%]).

Table 4. Mortality, Length of Hospital Stay, In-Hospital Morbidity, and Follow-Up.

| No./total (%)a | Adjusted between-group risk difference (95% CI), %b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor milk | Preterm formula | ||

| Died | |||

| Prior to hospital discharge | 24/239 (10) | 18/244 (7.4) | NAc |

| Prior to follow-up | 29/231 (13) | 25/233 (11) | −1 (−4 to 2)d |

| Follow-up | |||

| Lost to follow-up | 29/210 (14) | 24/219 (11) | −3 (−9 to 4) |

| Followed upe | 181/210 (86) | 195/219 (89) | 3 (−9 to 4) |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 10/239 (4.2) | 22/244 (9.0) | −5 (−9 to −2)d |

| Late-onset sepsis | 47/238 (20) | 37/244 (15) | 5 (−1 to 11)d |

| Meningitis | 1/239 (0.4) | 2/244 (0.8) | NAc |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 94/222 (42) | 107/230 (47) | −5 (−14 to 3)d |

| Length of hospital stay, median (IQR), d | 94 (71 to 121) | 96 (73 to 122) | −3.03 (−13.6 to 7.54) |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Unless otherwise indicated.

From linear or robust Poisson regression models. Adjusted for birth weight stratum (≤750 g, >750 g), day of life at randomization, and study center.

The adjusted between-group risk difference is not available because the model did not converge due to sparse data (even after clustering for center).

Due to sparse data, robust Poisson generalized estimating equation models were used with clustering for center.

Excludes participants (4 in donor milk group and 3 in preterm formula group) with incomplete follow-up data.

Necrotizing enterocolitis occurred among 4.2% of infants (10/239) in the donor milk group vs 9.0% of infants (22/244) in the preterm formula group (adjusted between-group risk difference, −5% [95% CI, −9% to −2%]). No infants developed hospital-acquired viral infection.

Discussion

Among extremely preterm infants fed no or minimal maternal milk, developmental outcomes at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age did not differ between those fed nutrient-fortified, pasteurized donor human milk and those fed preterm formula. The BSID cognitive, language, and motor scores were essentially the same in both groups (mean differences of <1 point for all BSID scores). These differences were not clinically significant based on previous literature that suggests a 5-point improvement could result in decreased need for special educational services for very preterm children.10 The incidence and severity of neurodevelopmental impairment and cerebral palsy were also unaffected by diet group.

Randomized clinical trials8,22 on the neurodevelopmental effect of donor milk vs formula in preterm infants, which included infants who received a variable amount of maternal milk, have not demonstrated a neurodevelopmental advantage with donor milk. The most recent Cochrane review15 of formula vs donor milk for preterm infants concluded with moderate GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) evidence that the data do not show an effect of donor milk on neurodevelopment.

Previous studies may have failed to detect neurodevelopmental benefits of donor milk compared with formula due to high maternal milk intake.8,22 However, in the current study, developmental outcomes were not affected by diet type even in the subgroup with very low maternal milk exposure. In addition, no effect was noted among the subgroup of 114 infants who did not receive maternal milk. Therefore, we found no evidence that the use of donor human milk rather than preterm formula improves neurodevelopmental outcomes at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age.

In the current study, donor milk use was associated with a lower incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis, which was a prespecified secondary outcome. Infants randomized to donor milk experienced necrotizing enterocolitis half as often as those randomized to preterm formula. Similar reduced risk of necrotizing enterocolitis with the use of donor milk was reported by O’Connor et al22 and in the Cochrane meta-analysis15 of formula vs donor milk for preterm infants (relative risk, 0.53). This finding, which is consistent across multiple studies, suggests that donor human milk, like maternal milk, can reduce the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis compared with formula diets.

Donor milk has been associated with worse growth outcomes than preterm formula.15 In the current study, infants fed donor milk experienced slower weight gain than those fed formula. However, length and head circumference growth did not differ between diet groups. Although donor milk was associated with lower weight gain than preterm formula, the falloff in weight percentile during the study was less than that reported in previous studies of donor milk.22,23

In the current study, the mean weight at study end was at the 29th percentile for their age for the infants in the donor milk group compared with at the 40th percentile for the infants in the preterm formula group; at study entry, the weight in both groups was at the 30th percentile for age.24 This difference in growth is likely due to variation in milk fortification practices among centers, which were not standardized in the study, and by the inability to measure the macronutrient content of all donor milk used. It is well described that the protein and energy content in donor milk is lower than in mother’s milk, and is variable batch to batch.25

To our knowledge, this is the largest randomized clinical trial of donor milk vs preterm formula in extremely preterm infants undertaken in the era of routine human milk fortification and the current study included the largest number of infants without maternal milk exposure. In addition, the study population was recruited from geographically diverse academic medical centers in the US.

Limitations

This study was limited by several factors. First, the study closed early due to slow enrollment related to increasing donor milk use at participating centers and associated loss of equipoise. At study initiation in 2012, less than 25% of Neonatal Research Network centers used donor milk; at study cessation, more than 75% of participating centers were widely using donor milk. Within 1 year of study initiation, the American Academy of Pediatrics26 and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition27 published policy statements recommending donor milk for preterm infants for the first time. The supply of donor milk available from the Human Milk Banking Association of North America28 increased exponentially during the current study, as did reported use in US neonatal intensive care units.29,30

Second, information about the type and amount of milk fed to infants prior to enrollment was not collected, so it was not possible to assess how preenrollment feeding affected the primary outcome. However, a subgroup analysis found that cognitive scores did not differ between infants randomized on the fifth day of life and those randomized on the 17th day of life.

Third, the nutrient content of donor milk was not measured and nutritional management varied across centers; this may have contributed to our finding of slower weight gain in the donor milk group. Nutritional information was not collected at the participant level, limiting the ability to investigate the causes of slow weight gain.

Fourth, the recruited population may have been more medically vulnerable than the average preterm population because they had disproportionally high rates of factors associated with worse health outcomes, including limited maternal education, public insurance, and identification of the birthing parent as Black. These factors have been associated with increased risk of neonatal morbidity and poor neurocognitive developmental in extremely preterm infants.31,32,33 This may limit the generalizability of our findings to other preterm populations.

Conclusions

Among extremely preterm neonates fed minimal maternal milk, neurodevelopmental outcomes at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age did not differ between infants fed donor milk or preterm formula.

Trial protocol and statistical analysis plan

eTable. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Survivors Only

eFigure. Subgroup analyses of Bayley III Cognitive Score (primary outcome) by stratification variables

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Gilard V, Tebani A, Bekri S, Marret S. Intraventricular hemorrhage in very preterm infants: a comprehensive review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2447. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai S, Thompson DK, Anderson PJ, Yang JY. Short- and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of very preterm infants with neonatal sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Children (Basel). 2019;6(12):131. doi: 10.3390/children6120131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blakely ML, Tyson JE, Lally KP, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Initial laparotomy versus peritoneal drainage in extremely low birthweight infants with surgical necrotizing enterocolitis or isolated intestinal perforation: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2021;274(4):e370-e380. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen EA, Schmidt B. Epidemiology of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2014;100(3):145-157. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordova EG, Cherkerzian S, Bell K, et al. Association of poor postnatal growth with neurodevelopmental impairment in infancy and childhood: comparing the fetus and the healthy preterm infant references. J Pediatr. 2020;225:37-43.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller J, Tonkin E, Damarell RA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of human milk feeding and morbidity in very low birth weight infants. Nutrients. 2018;10(6):707. doi: 10.3390/nu10060707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altobelli E, Angeletti PM, Verrotti A, Petrocelli R. The impact of human milk on necrotizing enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2020;12(5):1322. doi: 10.3390/nu12051322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucas A, Morley R, Cole TJ, Gore SM. A randomised multicentre study of human milk versus formula and later development in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1994;70(2):F141-F146. doi: 10.1136/fn.70.2.F141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, et al. ; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development National Research Network . Persistent beneficial effects of breast milk ingested in the neonatal intensive care unit on outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants at 30 months of age. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e953-e959. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, et al. Beneficial effects of breast milk in the neonatal intensive care unit on the developmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants at 18 months of age. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e115-e123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meek JY, Noble L; Section on Breastfeeding . Policy statement: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2022;150(1):e2022057988. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Standards for improving the quality of care for small and sick newborns in health facilities. Published September 2020. Accessed January 19, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010765

- 13.World Health Organization . Optimal feeding of low birth-weight infants in low-and-middle-income countries. Updated January 1, 2011. Accessed May 3, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548366 [PubMed]

- 14.Embleton ND, Jennifer Moltu S, Lapillonne A, et al. Enteral Nutrition in Preterm Infants (2022): a position paper from the ESPGHAN committee on nutrition and invited experts. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2023;76(2):248-268. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quigley M, Embleton ND, McGuire W. Formula versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7(7):CD002971. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002971.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. 3rd edition. Pearson; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilbride HW, Vohr BR, McGowan EM, et al. Early neurodevelopmental follow-up in the NICHD Neonatal Research Network: advancing neonatal care and outcomes, opportunities for the future. Semin Perinatol. 2022;46(7):151642. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2022.151642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Younge N, Goldstein RF, Bann CM, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes among periviable infants. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):617-628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fenton TR, Kim JH. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg. 1978;187(1):1-7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197801000-00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh MC, Kliegman RM. Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1986;33(1):179-201. doi: 10.1016/S0031-3955(16)34975-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connor DL, Gibbins S, Kiss A, et al. ; GTA DoMINO Feeding Group . Effect of supplemental donor human milk compared with preterm formula on neurodevelopment of very low-birth-weight infants at 18 months: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(18):1897-1905. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colaizy TT, Carlson S, Saftlas AF, Morriss FH Jr. Growth in VLBW infants fed predominantly fortified maternal and donor human milk diets: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou JH, Roumiantsev S, Singh R. PediTools electronic growth chart calculators: applications in clinical care, research, and quality improvement. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(1):e16204. doi: 10.2196/16204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colaizy TT. Effects of milk banking procedures on nutritional and bioactive components of donor human milk. Semin Perinatol. 2021;45(2):151382. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2020.151382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Section on Breastfeeding . Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arslanoglu S, Corpeleijn W, Moro G, et al. ; ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition . Donor human milk for preterm infants: current evidence and research directions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57(4):535-542. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182a3af0a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Human Milk Banking Association of America . Nonprofit milk banks step up during formula crisis, dispensing nearly 10 million ounces in 2022. Published February 20, 2023. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.hmbana.org/news/blog.html/article/2023/02/20/nonprofit-milk-banks-step-up-during-formula-crisis-dispensing-nearly-10-million-ounces-in-2022

- 29.Hagadorn JI, Brownell EA, Lussier MM, Parker MG, Herson VC. Variability of criteria for pasteurized donor human milk use: a survey of US neonatal intensive care unit medical directors. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40(3):326-333. doi: 10.1177/0148607114550832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker MG, Barrero-Castillero A, Corwin BK, Kavanagh PL, Belfort MB, Wang CJ. Pasteurized human donor milk use among US level 3 neonatal intensive care units. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(3):381-389. doi: 10.1177/0890334413492909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janevic T, Zeitlin J, Auger N, et al. Association of race/ethnicity with very preterm neonatal morbidities. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1061-1069. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joseph RM, O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Heeren T, Kuban KK. Maternal educational status at birth, maternal educational advancement, and neurocognitive outcomes at age 10 years among children born extremely preterm. Pediatr Res. 2018;83(4):767-777. doi: 10.1038/pr.2017.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly MM, Li K. Poverty, toxic stress, and education in children born preterm. Nurs Res. 2019;68(4):275-284. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol and statistical analysis plan

eTable. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Survivors Only

eFigure. Subgroup analyses of Bayley III Cognitive Score (primary outcome) by stratification variables

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement