Abstract

Activation of the CFTR Cl– channel inhibits epithelial Na+ channels (ENaC), according to studies on epithelial cells and overexpressing recombinant cells. Here we demonstrate that ENaC is inhibited during stimulation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrance conductance regulator (CFTR) in Xenopus oocytes, independent of the experimental set-up and the magnitude of the whole-cell current. Inhibition of ENaC is augmented at higher CFTR Cl– currents. Similar to CFTR, ClC-0 Cl– currents also inhibit ENaC, as well as high extracellular Na+ and Cl– in partially permeabilized oocytes. Thus, inhibition of ENaC is not specific to CFTR and seems to be mediated by Cl–.

INTRODUCTION

A regulatory relationship has been suggested between the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and epithelial Na+ channels (ENaC) in human and murine airway and intestinal epithelia (Mall et al., 1998, 1999). Enhanced Na+ absorption has been demonstrated in airway and colonic epithelia carrying the cystic fibrosis (CF) defect (Boucher et al., 1988). Subsequent studies have shown that the ENaC are inhibited during activation of CFTR, in recombinant cells (Stutts et al., 1995; Mall et al., 1996; Briel et al., 1998) and in native cells (Letz and Korbmacher, 1997; Ismailov et al., 1996; Mall et al., 1998, 1999; Jiang et al., 2000). Thus, enhanced amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ conductance in CF airways and intestine is likely to be caused by missing inhibition of ENaC due to mutant CFTR. The reciprocal interaction of CFTR and ENaC is not well understood. However, a recent study has shown that the amplitude of CFTR Cl– currents is crucial for inhibition of ENaC (Briel et al., 1998). Here we demonstrate that anions are required for inhibition of ENaC, and that an increase in the intracellular Cl– concentration is likely to inhibit ENaC.

RESULTS

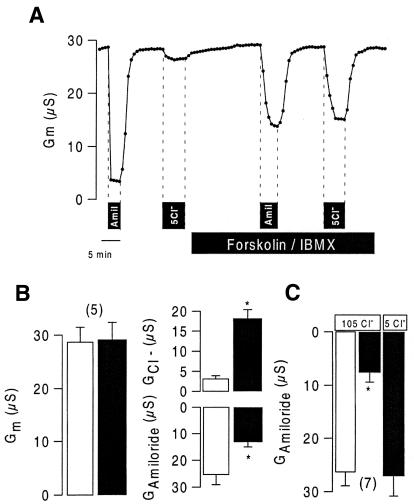

CFTR and ENaC were coexpressed in Xenopus oocytes and amiloride-sensitive Na+ conductance was 24 ± 3.2 µS (n = 5) in coexpressing oocytes compared with 37 ± 4.5 (n = 8) in oocytes expressing ENaC only. After activation of CFTR with IBMX (1 mmol/l) and forskolin (2 µmol/l), the effect of amiloride was attenuated (Figure 1). Activation of CFTR was demonstrated by the effect of low (5 mmol/l) extracellular Cl– on the whole-cell conductance, and inhibition of Na+ conductance was demonstrated by a reduced effect of amiloride. Both activation of the Cl– conductance (GCl–) and inhibition of the Na+ conductance (GAmiloride) occurred at similar magnitude and therefore no change in total conductance was observed (Figure 1A and B). ENaC was inhibited by CFTR in the presence of high (105 mmol/l) extracellular Cl– and was completely recovered when subsequently the bath Cl– concentration was reduced to 5 mmol/l. This demonstrates the requirement of Cl– for inhibition of ENaC and shows the reversibility of the inhibitory effect on ENaC.

Fig. 1. Continuous recording (A) and summary (B) of whole-cell conductances obtained from Xenopus oocytes coexpressing CFTR and ENaC. The effects of amiloride (10 µmol/l) and low bath Cl– (5 mmol/l) were compared before and after stimulation with IBMX (1 mmol/l) and forskolin (10 µmol/l). No net change in the whole-cell conductance (Gm) was observed during activation (IBMX/forskolin; black bars) of the Cl– conductance (GCl–) and inhibition of ENaC (GAmiloride). (C) Stimulation of CFTR in the presence of high (105 mmol/l) but not low (5 mmol/l) extracellular Cl– inhibited ENaC. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (paired t-test, P <0.05) (number of experiments shown in parentheses). The experiments were performed with OOC-1 and Warner OC725C amplifiers with two bath electrodes..

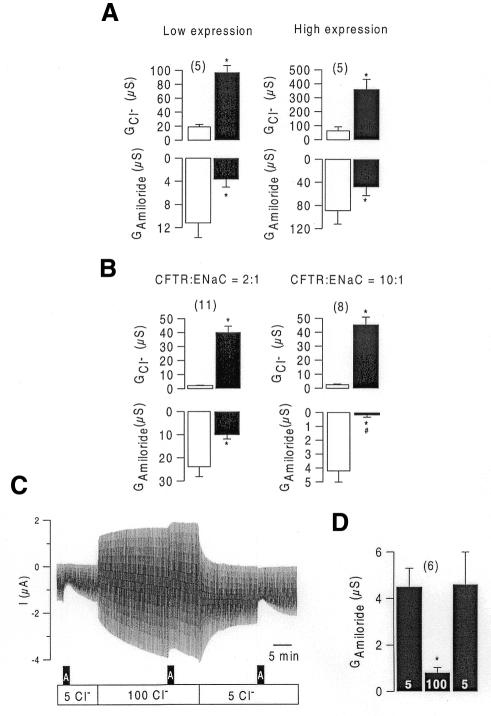

We examined whether the level of expression of CFTR and ENaC has an impact on the inhibition of ENaC. The summary of these experiments (Figure 2A) shows inhibition of ENaC by CFTR in oocytes expressing both low and high conductances, however the ratio of CFTR to ENaC currents is crucial. In oocytes with a CFTR to ENaC conductance ratio of roughly 2:1, stimulation of CFTR inhibited ∼60% of the initial ENaC conductance. However, 95% of the initial ENaC conductance was inhibited at a ratio of 10:1 (Figure 2B). These results show that the amount of the CFTR conductance relative to ENaC determines inhibition of ENaC. The result could be explained by a ‘patchy’ and thus unequal expression of ENaC and CFTR with the possibility of an inhomogeneous increase of intracellular Cl–, or by interaction of both proteins that requires a certain stoichiometry (Ji et al., 2000).

Fig. 2. (A) Summaries of Cl– (GCl–) and ENaC (GAmiloride) whole-cell conductance in Xenopus oocytes expressing low or high levels of CFTR and ENaC. Conductances were obtained before (white bars) and after (black bars) stimulation with IBMX and forskolin. (B) Summary of Cl– (GCl–) and ENaC (GAmiloride) from experiments showing two different ratios of expression for GCFTR:GENaC of ∼2:1 and 10:1. Stronger inhibition of ENaC is observed at the higher ratio. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (paired t-test, P <0.05). # indicates significant difference of ENaC inhibition at high and low ratios (unpaired t-test, P <0.05) (number of experiments shown in parentheses). (C) Continuous recording of the whole-cell current generated by expression of ENaC and ClCl-0 in a Xenopus oocyte. Oocytes were voltage clamped from –60 to +40 mV in steps of 10 mV. Note that the effect of amiloride is significantly and reversible inhibited at high bath Cl– concentration. (D) Summary of the whole-cell conductances obtained from experiments shown in (C). GAmiloride is significantly (paired t-test, P <0.05) inhibited at high extracellular Cl– concentration (number of experiments shown in parentheses). Experiments were performed with GeneClamp 500 and Warner OC725C amplifiers using two bath electrodes.

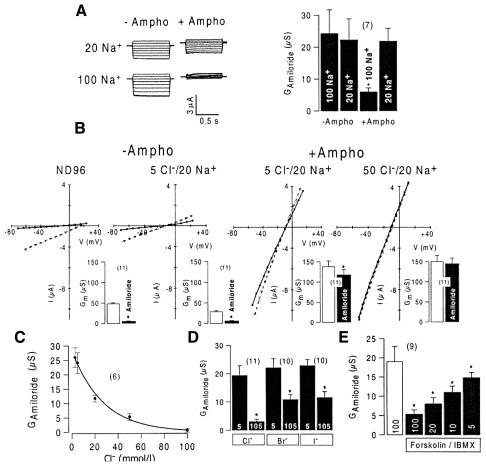

A contribution of Cl– to inhibition of ENaC by CFTR has been suggested previously (Briel et al., 1998). To confirm further the role of Cl– in inhibition of ENaC by CFTR, we coexpressed another Cl– channel, ClC-0, together with ENaC (Kieferle et al., 1994). A Cl– conductance of 48.0 ± 3.7 µS was observed in the presence of 100 mmol/l extracellular Cl–, which was reduced to 8.3 ± 0.8 µS (n = 8) at 5 mmol/l Cl– (Figure 2C). Amiloride-sensitive Na+ conductance was 4.6 ± 1.1 µS (n = 6) in coexpressing oocytes compared with 14.4 ± 2.1 (n = 9) in oocytes expressing ENaC only. We examined the effect of amiloride in the presence of low and high bath Cl– and found a pronounced inhibition of GAmiloride at 100 mmol/l Cl– (Figure 2C and D). This result suggests that inhibition of ENaC is not unique to CFTR and may be due to an increase in the intracellular Cl– concentration. We used another approach to examine whether possible changes in the intracellular Cl– and/or Na+ concentration in Xenopus ooyctes interfere with ENaC, by a partial permeabilization of the oocyte membrane with amphotericin B (1 µmol/l), which leads to a permeability for cations > anions. Thus, adaptation of the intracellular ion concentration to that of the bath solution was expected (Rae et al., 1991). Increase in intracellular Na+ has been shown to inhibit ENaC in Xenopus oocytes (Kellenberger et al., 1998; Hübner et al., 1999). We therefore expected inhibition of ENaC during an increase of extracellular Na+ from 20 to 100 mmol/l in the continuous presence of amphotericin B and at low (5 mmol/l) bath Cl–. After subtraction of the leak current (2.7 ± 3.6 µA, Vc = –80 mV), an amiloride-sensitive whole cell current of 2.4 ± 3.4 µA was determined accurately. In the absence of amphotericin B (–Ampho), ENaC conductances were independent of bath Na+ concentration, while in the presence of amphotericin B (+Ampho), ENaC conductances were significantly inhibited at high (100 mmol/l) extracellular Na+ (Figure 3A). This confirms inhibition of ENaC by an increase in the intracellular Na+ concentration.

Fig. 3. (A) Amiloride-sensitive whole-cell currents in Xenopus oocytes after subtraction of leak currents and summary of the calculated amiloride sensitive whole-cell conductances (GAmiloride). Oocytes were voltage clamped from –50 to +20 mV in steps of 10 mV. Currents are shown before and after permeabilization with amphotericin B (Ampho; 1 µmol/l). ENaC is inhibited by high Na+ after permeabilization. (B) I/V curves obtained from ENaC expressing oocytes before (dotted line) and after (solid line) application of amiloride, and before (–Ampho) and after (+Ampho) permeabilization. After permeabilization, ENaC was inhibited by an increase of extracellular Cl– to 50 mmol/l. Inserts summarize total conductance and effect of amiloride before and after permeabilization. (C) Amiloride-sensitive Na+ conductances (GAmiloride) in permeabilized oocytes at various bath Cl– concentrations. (D) Amiloride-sensitive Na+ conductances (GAmiloride) in permeabilized oocytes in the presence of 5 and 105 mmol/l Cl–, Br– or I– in the bath solution. (E) Inhibition of ENaC by activation of CFTR at different extracellular Cl– concentrations. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (paired t-test, P <0.05) (number of experiments shown in parentheses). Experiments were performed with GeneClamp 500 and Warner OC725C amplifiers using two bath electrodes.

The increase of extracellular Cl– on amiloride-sensitive Na+ currents was examined in permeabilized oocytes. Although leak currents were higher in this series of experiments, we could determine precisely the amiloride-sensitive conductance (inserts in Figure 3). During permeabilization (+Ampho) and in the presence of 5 mmol/l Cl– and 20 mmol/l Na+, ENaC currents (and conductances) dropped non-significantly from 21.7 ± 3.7 µS (–Ampho) to 19.4 ± 3.4 µS (+Ampho) (Figure 3B). The subsequent increase of Cl– to 50 mmol/l reduced ENaC to 5.3 ± 1.2 µS (Figure 3B) (n = 11). A zero current potential of –10 mV was observed, which is due likely to a Na+ diffusion potential. We examined further the effects of various concentrations of extracellular Cl– on amiloride-sensitive Na+ conductance in permeabilized oocytes. The results indicate a gradual inhibition of ENaC with increasing extracellular Cl– concentrations (Figure 3C). Upon returning to 5 mmol/l bath Cl–, ∼50% of the initial ENaC conductance was recovered (data not shown). Moreover, high (105 mmol/l) but not low (5 mmol/l) extracellular concentrations of other anions such as Br– and I– inhibited ENaC significantly (Figure 3D). Finally, a similar Cl– concentration-dependent inhibition of ENaC was found in oocytes coexpressing CFTR and after stimulation with forskolin and IBMX (Figure 3E).

Cell swelling, which may occur during activation of CFTR or upon permeabilization, is unlikely to cause inhibition of ENaC, since similar results were obtained in the presence of 200 mosmol/l mannitol, counteracting potential cell swelling. Moreover, ENaC conductances were not altered by hypertonic (420 mosmol/kg) or hypotonic (100 mosmol/kg) bath solution (data not shown). Finally, inhibition of ENaC cannot be explained by a possible ‘rundown’ of ENaC activity for the following reasons. (i) ENaC conductance (21.2 ± 3.9 µS) does not attenuate under control conditions >90 min (20.2 ± 3.4 µS, n = 5). (ii) The protocols of all experiments shown here have been alternated with similar results. (iii) Inhibition of ENaC by CFTR could be elicited repetitively in the same oocytes. (iv) The inhibitory effects of CFTR, ClC-0 and Cl– (amphothericin B) were reversible (Figures 1C, 2D and 3D and E). Taken together, these results suggest that activation of CFTR may cause an increase in intracellular Cl– in Xenopus ooyctes, which inhibits ENaC.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies show inhibition of the epithelial Na+ channel ENaC by stimulation of CFTR in Xenopus oocytes (Mall et al., 1996; Briel et al., 1998; Schreiber et al., 1999). This is confirmed by these results, which demonstrate augmented inhibition at increased ratios of CFTR to ENaC conductance. Inhibition of ENaC by CFTR was observed at different expressions levels of both proteins and was independent of the type of amplifier used. A recent study demonstrated compromised measurements of ENaC currents in Xenopus oocytes with high current expression, using a single high resistance bath electrode (Nagel et al., 2001. The results of the study by Nagel et al. (2001) are not in agreement with the present results or previously published data (Mall et al., 1996; Briel et al., 1998; Schreiber et al., 1999), possibly for the following reasons. (i) The resistance of the single bath electrode used here and in our previous studies was low (700 Ω). (ii) The conductances in our previous studies and the present report were generally low (∼50 µS), and thus the contribution of the serial resistance did not exceed 4%. (iii) Inhibition of ENaC by CFTR takes place in oocytes, which do not show a net increase in the whole-cell conductance (Figure 1). (iv) Inhibition of ENaC by CFTR is observed in experiments with two bath electrodes and a virtual-ground headstage, eliminating a voltage drop across the serial resistance.

The present results show inhibition of ENaC by CFTR, ClC-0 and amphothericin B induced Cl– conductance, suggesting that the mechanism for inhibition of ENaC is rather non-specific and is mediated by Cl–. However, in the intact epithelium CFTR Cl– currents are inhibiting ENaC, since CFTR is the predominant Cl– channel in the airways and the only Cl– conductance in the colon (Willumsen et al., 1989a; Mall et al., 2000b). The lack of inhibition of ENaC by CFTR as reported recently is probably caused by the fact that too little CFTR had been expressed relative to ENaC currents in this study (Nagel et al., 2001). We clearly observe reversible inhibition of ENaC by CFTR, which is probably due to higher CFTR Cl– currents expressed in our study. According to our results, a proper ratio of both conductances is essential for inhibition of ENaC. As shown in Figure 2B and as demonstrated for CFTR truncations which generated only little Cl– conductance (Schreiber et al., 1999), low Cl– conductances exert only partial inhibitory effects on ENaC. Inhibition of ENaC by activation of endogenous Ca2+ activated Cl– currents in Xenopus oocytes was not observed previously (Briel et al., 1998). However, these Cl– currents may have been too small and transient to generate sufficient changes in the cytosolic Cl– concentration. In contrast, ENaC is inhibited during Ca2+-dependent stimulation of Cl– transport in airway epithelial cells, which may be crucial for the therapy of CF (Mall et al., 2000a). The present data suggest inhibition of ENaC by increasing concentrations of anions and Na+, although the data do not directly show an increase in intracellular Cl– upon stimulation of CFTR. However, since the membrane voltage in these oocytes is largely depolarized due to ENaC expression, a driving force exists for Cl– uptake. Activation of CFTR is therefore likely to enhance influx of both Na+ and Cl– ions, which could then inhibit ENaC. An increase in cytosolic Cl– during activation of CFTR in airways and colonic epithelial cells has not yet been examined (Willumsen et al., 1989b). Previous measurements were only done under baseline conditions, which did not reveal differences in cytosolic Cl– conductances between CF and non-CF airway epithelial cells (Willumsen et al., 1989b). A correlation between cytosolic Cl– activity and ENaC conductance might be difficult to assess, since local changes in Cl– concentration close to the cell membrane and in close proximity to ENaC would be already sufficient to inhibit ENaC. More detailed analysis will be required in order to assess the changes of the intracellular Cl– concentrations during activation of transport. The fact that amiloride-sensitive Na+ absorption is lower in non-CF compared with CF airways, even in the absence of exogenous stimulation, might be due to several reasons, such as the action of endogenous mediators, a possible protein interaction of CFTR and ENaC (Kunzelmann et al., 1997; Ji et al., 2000) and effects of CFTR on expression of ENaC.

Speculation

Because luminal Cl– has been shown to be in equilibrium in airway epithelial cells (Willumsen et al., 1989b), an opening of luminal Cl– channels could increase absorption of both Cl– and Na+ and thereby inhibit ENaC. In the sweat duct, cAMP-dependent stimulation activates ENaC and does not increase intracellular Cl– (Reddy and Quinton, 1994, 1999). Since CFTR is activated to a larger degree in the basolateral membrane of the sweat duct, this could even lead to a drop in cytosolic Cl– with stimulation of absorption (Reddy and Quinton, 1994).

METHODS

cRNAs for rat epithelial Na+ channel (rENaC) subunits, CFTR and ClC-0. Rat α,β,γ ENaC (kindly provided by Professor B. Rossier, Pharmacological Institute of Lausanne, Switzerland), human CFTR and ClC-0 (kindly provided by Dr M. Pusch, Instituto di Cibernetica e Biofisica, Genova, Italy) were linearized in pBluescript or pTLN (Kieferle et al., 1994), with NotI, XhoI or MlnI and in vitro transcribed using T7, T3 or SP6 promotor and polymerase (Message Machine, Ambion, Austin, TX).

Preparation of oocytes and microinjection of cRNA. Isolation and microinjection of oocytes have been described in a previous report (Briel et al., 1998). In brief, after isolation from adult Xenopus laevis female frogs, oocytes were dispersed and defolliculated by a 0.7 h treatment with collagenase (type A; Boehringer, Germany). Subsequently, oocytes were rinsed and kept in ND96 buffer (96 mmol/l NaCl, 2 mmol/l KCl, 1.8 mmol/l CaCl2, 1 mmol/l MgCl2 1, 5 mmol/l HEPES, 2.5 mmol/l Na-pyruvate pH 7.55) supplemented with theophylline (0.5 mmol/l) and gentamycin (5 mg/l) at 18°C. In some experiments, Cl– and Na+ were replaced by equimolar concentrations of gluconate and N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG), respectively. Oocytes of identical batches were injected with cRNA of αβγ rENaC (each subunit 5–50 ng) and CFTR (5–50 ng) in 32 nl double-distilled water (Nanoliter injector; WPI, Germany). Water-injected oocytes served as controls.

Electrophysiological analysis of Xenopus oocytes. Two days after injection, oocytes were impaled with two electrodes (Clark instruments), which had resistances of 1 MΩ when filled with 2.7 mol/l KCl. A large flowing (2.7 mol/l) KCl electrode served as bath reference in order to minimize junction potentials, which were close to zero when bath Cl– was replaced by gluconate. The electrode had a resistance of 700 Ω when immersed in ND96 bath solution. Membrane currents were measured by voltage clamping of the oocytes in intervals from –90 or –50 to +20 mV in steps of 10 mV, every 1000 ms. Current data were filtered at 50 Hz. For some protocols, oocytes were partially permeabilized by perfusion with 1 µM amphothericin B for 5 min. After stabilization of the currents, experiments were performed in the continuous presence of amphothericin B.

Whole-cell currents were measured by means of three different amplifiers [OOC-1 oocyte clamp amplifier (WPI, Germany) with one bath electrode, GeneClamp 500 amplifier (Axon Instruments) and Warner oocyte clamp amplifier OC725C, both with two bath electrodes and a virtual-ground headstage]. Using two bath electrodes, the voltage drop across Rserial is effectively zero. However, in the experiments performed with OOC-1, the voltage drop along Rserial was small due to low expression of CFTR and ENaC and did not exceed 4%. Between intervals, oocytes were voltage clamped to –20 mV for 20 s. Data were collected continuously (MacLab, AD Instruments). Data were analyzed using the programs chart and scope (McLab, AD Instruments, Macintosh). Conductances were calculated for the voltage clamp range of –90/–50 to +20 mV according to Ohm’s law. During the whole experiment the bath was continuously perfused at a rate of 5–10 ml/min.

Materials. All used compounds were of highest available grade of purity. Amiloride, IBMX, forskolin and amphotericin B were from Sigma (Castle Hill, NSW, Australia). Statistical analysis was performed according to Students’ t-test. A P-value <0.05 was accepted to indicate statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by DFG Ku756/4-1, German Mukoviszidose e.V., ARC A0-104609 and Cystic Fibrosis Australia.

REFERENCES

- Boucher R.C., Cotton, C.U., Gatzy, J.T., Knowles, M.R. and Yankaskas, J.R. (1988) Evidence for reduced Cl– and increased Na+ permeability in cystic fibrosis human primary cell cultures. J. Physiol. (Lond.), 405, 77–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briel M., Greger, R. and Kunzelmann, K. (1998) Cl– transport by CFTR contributes to the inhibition of epithelial Na+ channels in Xenopus ooyctes coexpressing CFTR and ENaC. J. Physiol. (Lond.), 508, 825–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübner M., Schreiber, R., Boucherot, A., Sanchez-Perez, A., Poronnik, P., Cook, D.I. and Kunzelmann, K. (1999) Feedback inhibition of epithelial Na+ channels in Xenopus oocytes does not require G0- or Gi2-proteins. FEBS Lett., 459, 443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismailov I.I., Awayda, M.S., Jovov, B., Berdiev, B.K., Fuller, C.M., Dedman, J.R., Kaetzel, M.A. and Benos, D.J. (1996) Regulation of epithelial sodium channels by the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 4725–4732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H.L., Chalfant, M.L., Jovov, B., Lockhart, J.P., Parker, S.B., Fuller, C.M., Stanton, B.A. and Benos, D.J. (2000) The cytosolic termini of the β and γ-ENaC subunits are involved in the functional interactions between CFTR and ENaC. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 27947–27951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Li, J., Dubroff, R., Ahn, Y.J., Foskett, J.K., Engelhardt, J. and Kleyman, T.R. (2000) Epithelial sodium channels regulate cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channels in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 13266–13274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellenberger S., Gautschi, I., Rossier, B.C. and Schild, L. (1998) Mutations causing Liddle syndrome reduce sodium-dependent downregulation of the epithelial sodium channel in the Xenopus oocyte expression system. J. Clin. Invest., 101, 2741–2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieferle S., Fong, P., Bens, M., Vandewalle, A. and Jentsch, T.J. (1994) Two highly homologous members of the ClC chloride channel family in both rat and human kidney. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 6943–6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K., Kiser, G., Schreiber, R. and Riordan, J.R. (1997) Inhibition of epithelial sodium currents by intracellular domains of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. FEBS Lett., 400, 341–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letz B. and Korbmacher, C. (1997) cAMP stimulates CFTR-like Cl– channels and inhibits amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels in mouse CCD cells. Am. J. Physiol., 272, C657–C666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mall M., Hipper, A., Greger, R. and Kunzelmann, K. (1996) Wild type but not ΔF508 CFTR inhibits Na+ conductance when coexpressed in Xenopus oocytes. FEBS Lett., 381, 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mall M., Bleich, M., Greger, R., Schreiber, R. and Kunzelmann, K. (1998) The amiloride inhibitable Na+ conductance is reduced by CFTR in normal but not in CF airways. J. Clin. Invest., 102, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mall M., Bleich, M., Kühr, J., Brandis, M., Greger, R. and Kunzelmann, K. (1999) CFTR-mediated inhibition of amiloride sensitive sodium conductance by CFTR in human colon is defective in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol., 277, G709–G716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mall M., Wissner, A., Kühr, J., Gonska, T., Brandis, M. and Kunzelmann, K. (2000a) Inhibition of amiloride sensitive epithelial Na+ absorption by extracellular nucleotides in human normal and CF airways. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol., 23, 755–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mall M., Wissner, A., Seydewitz, H.H., Kühr, J., Brandis, M., Greger, R. and Kunzelmann, K. (2000b) Defective cholinergic Cl– secretion and detection of K+ secretion in rectal biopsies from cystic fibrosis patients. Am. J. Physiol., 278, G617–G624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel G., Szellas, T., Riordan, J.R., Frierich, T. and Hartung, K. (2001) Non-specific activation of the epithelial sodium channel by the CFTR chloride channel. EMBO Rep., 2, 249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae J., Cooper, K., Gates, P. and Watsky, M. (1991) Low access resistance perforated patch recordings using amphotericin B. J. Neurosci. Meth., 37, 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy M.M. and Quinton, P.M. (1994) Intracellular Cl activity: evidence of dual mechanisms of Cl– absorption in sweat duct. Am. J. Physiol., 267, C1136–C1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy M.M. and Quinton, P.M. (1999) Activation of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) requires CFTR Cl– channel function. Nature, 402, 301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R., Hopf, A., Mall, M., Greger, R. and Kunzelmann, K. (1999) The first nucleotide binding fold of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is important for inhibition of the epithelial Na+ channel. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 5310–5315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutts M.J., Canessa, C.M., Olsen, J.C., Hamrick, M., Cohn, J.A., Rossier, B.C. and Boucher, R.C. (1995) CFTR as a cAMP-dependent regulator of sodium channels. Science, 269, 847–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willumsen N.J., Davis, C.W. and Boucher, R.C. (1989a) Cellular Cl– transport in cultured cystic fibrosis airway epithelium. Am. J. Physiol., 256, C1045–C1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willumsen N.J., Davis, C.W. and Boucher, R.C. (1989b) Intracellular Cl– activity and cellular Cl– pathways in cultured human airway epithelium. Am. J. Physiol., 256, C1033–C1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]