Abstract

Background:

While perinatal anxiety is common in birthing and non-birthing parents, little is known about the mental health or educational needs of non-birthing parents during the perinatal period, and whether perinatal anxiety in the birthing parent is associated with non-birthing parent educational preferences.

Objective(s):

To examine the desired digital perinatal educational preferences of non-birthing parents and whether these preferences differed by: 1) endorsement of high parenthood-related anxiety in the non-birthing partner, and 2) mental health of the birthing parent (including both identified mental health conditions and presence of pregnancy-related anxiety)

Study Design:

In this cross-sectional study, non-birthing and birthing parents using Maven, a digital perinatal health platform, selected the areas in which they wanted education or support from a list of options. Participants also reported their experience of parenthood or pregnancy-related anxiety through a 5-item Likert scale in response to the prompt, “On a scale of 1=None to 5=Extremely, how anxious are you feeling about parenthood / pregnancy?” High-parenthood or pregnancy-related anxiety was defined as being very (4) or extremely (5) anxious. Birthing parents also reported whether they had a current or prior mood disorder, but this information was not reported by non-birthing parents. Survey responses for birthing and non-birthing parents were linked through the digital platform. Descriptive analyses were used to assess non-birthing parent demographics and perinatal support interests, stratified by high parenthood-related anxiety, high pregnancy-related anxiety in their partner, and perinatal mood disorders or high pregnancy-related anxiety in their partner.

Results:

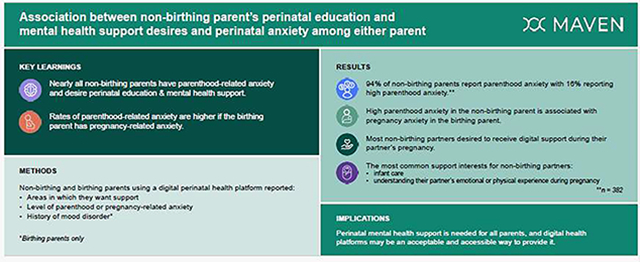

Among 382 non-birthing parents, most (85.6%) desired to receive digital support during their partner’s pregnancy: the most commonly endorsed support interests were infant care (327 (85.6%)) and understanding their partner’s emotional (313 (81.9%)) or physical (294 (77.0%)) experience during pregnancy. Overall, 355 (93.9%) of non-birthing parents endorsed any parenthood-related anxiety, and 63 (16.5%) were categorized as having high parenthood-related anxiety. Those with high parenthood-related anxiety were more likely to desire digital support for each topic. Among birthing parents, 124 (32.4%) had a mental health condition and 45 (11.8%) had high pregnancy-related anxiety. When non-birthing parents were stratified by presence of their partner having a mental health condition or high pregnancy-related anxiety alone, no differences in desired perinatal education were identified. Though non-birthing parents had higher rates of high parenthood-related anxiety if the birthing parent reported high pregnancy anxiety (17 (27.0%) versus 28 (8.8%); p<0.001), no difference was found with other conditions within the mental health composite.

Conclusion:

In this cross-sectional study, many non-birthing parents who engaged with a perinatal digital platform desired education on their or their partner’s emotional health during the perinatal period, and most endorsed parenthood-related anxiety. These findings suggest that perinatal mental health support is needed for nearly all parents and that non-birthing parents who utilize digital health platforms are amenable to receiving comprehensive perinatal education via these platforms.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Regardless of a parent’s gender or role in the birthing process, the perinatal period is among the highest risk time across the lifespan for having symptoms of anxiety: up to 25% of parents experience anxiety during pregnancy or within a year of childbirth.1–4 Despite the similar prevalence of perinatal anxiety between parents and the well-described and reciprocal association between maternal postpartum mood disorders and increased risk of paternal postpartum mood disorders,5–9 perinatal anxiety research on non-birthing parents is scant.10,11 Little is known about whether non-birthing parents desire pregnancy-related education including mental health during the perinatal period. In addition, it is possible that the perinatal educational preferences of non-birthing parents may change if they themselves have high parenthood-related anxiety or if their partner has high pregnancy-related anxiety. These insights are important in informing the development of targeted interventions that have the potential to support parents during this high-risk time.

Reproductive age men (who are often, but not always, the non-birthing parent) are markedly less likely than reproductive-aged women to engage with the healthcare system,12,13 and traditional prenatal care models do not routinely provide preventive or mental health care for non-birthing parents.14 Digital health platforms offering perinatal support for both birthing and non-birthing parents provide a mechanism to gain insight into non-birthing parent’s perinatal educational preferences. Thus, using data obtained from a perinatal digital platform, we aimed to first examine digital educational preferences among non-birthing parents during their partner’s pregnancy and then assess whether these educational preferences differed among those who endorsed high parenthood-related anxiety or whose partner had mental health conditions or high pregnancy-related anxiety.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria/Recruitment

This study used data from a cohort of users who enrolled in Maven from March 16, 2021 through October 20, 2022. Maven is a comprehensive women’s and family health digital platform that was developed to provide support services that supplement and complement routine prenatal care through digital services. Users receive free and unlimited access to Maven as an employer-sponsored health benefit through their own or their partner’s employer. Within the digital platform, Maven offers educational content (articles, videos, and live classes), care coordination (through a dedicated care advocate), and provider services (virtual appointments and communication with a diverse team of providers).

Users complete an onboarding survey upon enrollment. The non-birthing parent’s onboarding survey collects self-reported information including their desired support interests and parenthood-related anxiety. To report support interests, users selected as many support interests as they desired from the following list in response to the question, “Which areas are you most interested in receiving support in?”: “Choosing a healthcare provider/team”; “Labor and delivery options”; “Preparing to be a working parent”; “Infant care”; “Learning about childcare options”; “My own emotional health”; “Understanding my parent’s physical experience during pregnancy”; and/or “Understanding my parent’s emotional experience during pregnancy.” Parenthood-related anxiety was reported through a 5-item Likert scale15 in response to the prompt, “On a scale of 1 to 5, how anxious are you feeling about parenthood?” with options ranging from 1= not at all to 5=extremely. High parenthood-related anxiety was defined as responding with a 4 (“very”) or 5 (“extremely”).

For birthing parents, a composite of birthing parent mental health conditions was created, comprised of either 1) a personal history or current diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or perinatal mood disorder (regardless of whether patient has or has not received treatment) or 2) high pregnancy-related anxiety. The latter was reported in response to the prompt (provided during pregnancy), “On a scale of 1–5, how anxious are you feeling about your pregnancy?”, with options ranging from 1= not at all to 5=extremely. High pregnancy-related anxiety was defined in this study as responding with a 4 (“very”) or 5 (“extremely”); however, being categorized as having high pregnancy-related (or parenthood-related) anxiety does not signify the presence of an actual mental health condition as neither Likert scale is diagnostic. Aside from parenthood-related anxiety, self-reported data on mental health conditions for the non-birthing parent was not captured.

Both birthing and non-birthing parents reported whether they were first time parents, their race and ethnicity, and household income. Due to small sample sizes, users who reported their race/ethnicity as American Indian or Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or multiple races were categorized in the “Other” category. Income was assessed categorically.

Users were included if they completed an onboarding survey and if both the birthing and non-birthing parent were enrolled in Maven at any point during the birthing person’s pregnancy. Users consented to the use of their de-identified data for scientific research upon creating an account for the digital platform. The study was designated as exempt by WCG Institutional Review Board, an independent ethical review board.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to assess non-birthing parent demographics and perinatal support interests overall. We then examined perinatal support interests after stratifying the cohort by the presence of high parenthood-related anxiety in the non-birthing parent, of high-pregnancy-related anxiety in their birthing parent, and the presence of any condition within the birthing parent mental health composite. In bivariate analyses, Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess categorical variables. All analyses were conducted in R v.3.6.3.16

Results

Data were included from 382 birthing and non-birthing parental dyads, who independently created accounts in Maven, completed all relevant information on onboarding surveys, and had their accounts linked by Maven. Overall, most non-birthing parents self-identified as male (96.3%), as first-time parents (83.2%), as White (43.5%) or Asian (30.1%), and having annual incomes of more than $100,000 (72.2%) (Table 1). In terms of perinatal anxiety, 355 (93.9%) non-birthing parents endorsed any parenthood-related anxiety and 63 (16.5%) were categorized as having high parenthood-related anxiety, while 45 (11.8%) birthing parents endorsed high pregnancy-related anxiety. One in three birthing parents (32.5%) endorsed having a condition within the mental health composite.

Table 1.

Non-birthing parent demographics and desired support by parenthood-related anxiety

| Overall (N=382) | Low Parenthood-related anxiety (N=319) | High Parenthood-related anxiety (N=63) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race / Ethnicity | 0.27 | |||

| Asian | 115 (30.1%) | 92 (28.8%) | 23 (36.5%) | |

| Black | 23 (6.0%) | 19 (6.0%) | 4 (6.3%) | |

| Hispanic | 30 (7.9%) | 22 (6.9%) | 8 (12.7%) | |

| Other | 48 (12.6%) | 41 (12.9%) | 7 (11.1%) | |

| White | 166 (43.5%) | 145 (45.5%) | 21 (33.3%) | |

| First-time Parent | 318 (83.2%) | 261 (81.8%) | 57 (90.5%) | 0.09 |

| Biological Sex | 0.82 | |||

| Female | 2 (0.5%) | 2 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Male | 368 (96.3%) | 307 (96.2%) | 61 (96.8%) | |

| Missing | 12 (3.1%) | 10 (3.1%) | 2 (3.2%) | |

| Household Income | 0.91 | |||

| Less than $50k | 4 (1.0%) | 3 (0.9%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| $50k-$100k | 30 (7.9%) | 24 (7.5%) | 6 (9.5%) | |

| More than $100k | 272 (71.2%) | 228 (71.5%) | 44 (69.8%) | |

| Missing | 76 (19.9%) | 64 (20.1%) | 12 (19.0%) | |

| Birthing Parent Mental Health Condition Composite | 124 (32.5%) | 99 (31.0%) | 25 (39.7%) | 0.18 |

| History of depression | 47 (12.3%) | 38 (11.9%) | 9 (14.3%) | 0.6 |

| History of anxiety | 88 (23.0%) | 76 (23.8%) | 12 (19.0%) | 0.41 |

| Perinatal mood disorder | 6 (1.6%) | 5 (1.6%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0.99 |

| High pregnancy anxiety | 45 (11.8%) | 28 (8.8%) | 17 (27.0%) | <0.001 |

The prevalence of non-birthing parents who endorsed high parenthood-related anxiety was higher among Hispanic, Asian, or Black users compared to White users and among those who reported annual income of <$50,000, or between $50,000 and $100,000, compared to ≥ $100,000 (Table 1). The prevalence of high parenthood-related anxiety was increased among first-time parents (n=57 (17.9%)) compared to non- first-time parents (n=6 (9.4%)), but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.09). There was no difference among rates of high parenthood-related anxiety in non-birthing parents when stratified by whether the birthing parent endorsed any condition in the mental health composite. However, non-birthing parents had higher rates of high parenthood-related anxiety if the birthing parent had high pregnancy anxiety (17 (27.0%) versus 28 (8.8%); p<0.001).

Overall, most non-birthing parents reported interest in receiving digital educational support during their partner’s pregnancy: the most commonly reported support interests were infant care (327 (85.6%)) and understanding their partner’s emotional (313 (81.9%)) or physical (294 (77.0%)) experience during pregnancy (Table 2). More than two in five non-birthing parents (160 (41.9%)) desired to receive education on their own emotional health. Across each of the support interests, non-birthing parents with high parenthood-related anxiety were descriptively more likely to report that they desire digital support than those without parenthood-related anxiety; however, this difference was only statistically significant for education on their own emotional health (36 (57.1%) versus 124 (38.9%); p =0.009) and understanding their parent’s physical experience during pregnancy (55 (87.3%) versus 239 (74.9%); p =0.04).

Table 2.

Non-birthing parent desired support, stratified by non-birthing parent’s parenthood-related anxiety

| Overall (N=382) | Low Parenthood-related anxiety (N=319) | High Parenthood-related anxiety (N=63) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Interests | ||||

| Infant care | 327 (85.6%) | 272 (85.3%) | 55 (87.3%) | 0.80 |

| Understanding my partner’s emotional experience during pregnancy | 313 (81.9%) | 257 (80.6%) | 56 (88.9%) | 0.15 |

| Understanding my partner’s physical experience during pregnancy | 294 (77.0%) | 239 (74.9%) | 55 (87.3%) | 0.04 |

| Preparing to be a working parent | 289 (75.7%) | 236 (74.0%) | 53 (84.1%) | 0.11 |

| Leaning about childcare options | 217 (56.8%) | 179 (56.1%) | 38 (60.3%) | 0.59 |

| Labor and delivery options | 174 (45.5%) | 141 (44.2%) | 33 (52.4%) | 0.26 |

| My own emotional health | 160 (41.9%) | 124 (38.9%) | 36 (57.1%) | 0.009 |

| Choosing a healthcare provider/team | 94 (24.6%) | 77 (24.1%) | 17 (27.0%) | 0.66 |

When non-birthing parents were stratified by presence of their partner having any mental health condition (Table 3) or high pregnancy-related anxiety alone (Table 4), no differences were identified in non-birthing parents’ support interests. While a higher proportion of non-birthing parents desired digital support on their own emotional health when the birthing parent endorsed high pregnancy-related anxiety, this difference did not achieve statistical significance (25 (55.6%) versus 134 (40.2%); p =0.06) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Non-birthing parent desired support, stratified by birthing parent mental health condition

| Support Interests | Birthing Parent No Mental Health Condition1 (N=258) | Birthing Parent Mental Health Condition1 (N=124) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infant care | 222 (86.0%) | 105 (84.7%) | 0.53 |

| Understanding my partner’s emotional experience during pregnancy | 208 (80.6%) | 105 (84.7%) | 0.45 |

| Understanding my partner’s physical experience during pregnancy | 201 (77.9%) | 93 (75.0%) | 0.4 |

| Preparing to be a working parent | 200 (77.5%) | 89 (71.8%) | 0.15 |

| Learning about childcare options | 150 (58.1%) | 67 (54.0%) | 0.38 |

| Labor and delivery options | 121 (46.9%) | 53 (42.7%) | 0.39 |

| My own emotional health | 106 (41.1%) | 54 (43.5%) | 0.71 |

| Choosing a healthcare provider/team | 63 (24.4%) | 31 (25.0%) | 0.95 |

Mental health condition defined as self-report on Maven onboarding survey a history of depression or anxiety or perinatal mood disorder or high pregnancy-related anxiety

Table 4.

Non-birthing parent desired support, stratified by birthing parent pregnancy-related anxiety

| Support Interests | Birthing Parent Low Pregnancy-Related Anxiety (N=333) | Birthing Parent High Pregnancy-Related Anxiety (N=45) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infant care | 285 (85.6%) | 40 (88.9%) | 0.64 |

| Understanding my partner’s emotional experience during pregnancy | 272 (81.7%) | 38 (84.4%) | 0.74 |

| Understanding my partner’s physical experience during pregnancy | 256 (76.9%) | 35 (77.8%) | 0.98 |

| Preparing to be a working parent | 255 (76.6%) | 32 (71.1%) | 0.36 |

| Leaning about childcare options | 188 (56.5%) | 28 (62.2%) | 0.5 |

| Labor and delivery options | 153 (45.9%) | 20 (44.4%) | 0.81 |

| My own emotional health | 134 (40.2%) | 25 (55.6%) | 0.06 |

| Choosing a healthcare provider/team | 80 (24.0%) | 13 (28.9%) | 0.5 |

Discussion

Principal Results

In this cross-sectional study of parent dyads who engaged with a perinatal digital platform, a significant proportion of non-birthing partners desired education on the birthing parent’s emotional or physical experience during pregnancy, and many desired to receive education on their own emotional health. In addition, nearly all non-birthing parents had at least some parenthood-related anxiety, and the proportion of high parenthood-related anxiety among non-birthing parents was similar to that of high pregnancy-related anxiety among birthing parents. Digital educational preferences were similar among non-birthing parents whose partners did versus did not have mental health conditions. Collectively, these findings suggest not only that perinatal mental health support is needed for nearly all parents, but also that non-birthing parents who utilize digital health platforms are amenable to receiving comprehensive perinatal education and mental health support via these platforms.

Results in the Context of What is Known

In this cohort, the majority of non-birthing parents endorsed having parenthood-related anxiety, which is consistent with prior research demonstrating that adjustment disorder with anxiety symptoms is the most common mental health diagnosis for perinatal fathers.17 In addition, the prevalence of high parenthood-related anxiety identified in this study (16%) among non-birthing parents is within the range of prevalence of perinatal anxiety among fathers in the published literature (3–25%).2,11 While rates of pregnancy-related anxiety were similar between non-birthing and birthing parents, our findings differ from the current literature in that birthing parents’ mental health conditions were not associated with non-birthing parent anxiety.5–9 This difference could be because participants self-reported perinatal mental health conditions, whereas other studies may have relied on diagnoses obtained through psychometric screening tools, diagnostic interviews or the medical record.5–9 It may also be due to the specific patient sample, who based on sociodemographic characteristics may have better access to mental health treatment and thereby improved management of their mental health conditions.

Clinical Implications

Our findings suggest that non-birthing partners seek perinatal education and mental health support, which is not currently addressed in most perinatal care delivery models. Ideally, all parents should be offered perinatal educational support including mental health, particularly those experiencing parenthood or pregnancy-related anxiety. There are considerable barriers, however, to achieving this in routine practice, and alternative approaches to delivery of educational content are needed. Our study suggests that digitally delivered mental health support and perinatal education are acceptable to non-birthing parents. In the United States, 96% of individuals aged 18–29, 95% of those aged 30–49 years, and 76% of individuals earning <$30,000 annually own a smartphone,18 and most low-income people have home internet.19 Thus, digitally delivered perinatal education and mental health support can be made accessible to nearly all non-birthing parents, thereby filling an important gap in terms of non-birthing parents’ perinatal education and mental health support preferences. This innovative method of care delivery overcomes many obstacles for providing perinatal education and mental health support to non-birthing parents, including low engagement with healthcare12,13 and current prenatal care models.14

Research Implications

These findings provide important initial insights into non-birthing parents’ perinatal educational desires and mental health concerns. However, prior to widespread adoption of perinatal digital education and mental health support for non-birthing parents, these findings should be confirmed in a larger, prospectively collected study that examines non-birthing parents’ perinatal experience and digital health use longitudinally. In this manner, the potential effect of perinatal education and mental health support on both parents’ parenthood-anxieties and other mental health outcomes can be further evaluated.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has many strengths including a large cohort of matched non-birthing and birthing partners. In addition, non-birthing parents and birthing parents completed the onboarding surveys independently, reducing the risk of response bias. In addition, as this study was conducted exclusively among users of a digital health platform, these findings demonstrate that non-birthing parents who register with a digital health platform are amenable to and desire digital perinatal education and perinatal mental health support.

Nonetheless, this project is not without limitations. First, non-birthing and birthing parents self-reported the presence of parenthood- or pregnancy-related anxiety on a Likert scale, not a validated anxiety measure. Similarly, as all mood disorders were self-reported instead of clinically diagnosed, the prevalence of mood disorders may not accurately reflect the prevalence of these conditions in our study population. Second, data on the prevalence of mental health conditions is not captured for non-birthing parents; therefore, we cannot comment on whether non-birthing parents who endorsed high parenthood-related anxiety had higher rates of self-reported anxiety disorders. Third, generalizability of these findings may be reduced due to characteristics of our study population, which was comprised exclusively of digital health users, many of whom reported annual incomes of >$100,000 and all of whom access the digital platform as an employer-sponsored health benefit through their own or their partner’s employer. Lastly, minoritized individuals and those with less socioeconomic resources reported higher levels anxiety, and it will be critical to directly target minoritized, low resourced, and non-heterosexual couples, including those not yet able to access digital health tools, to understand how their support preferences may differ.

Conclusions

Among non-birthing parents who utilized a digital health platform, most desired digitally delivered perinatal education, and nearly all reported having some parenthood-related anxiety. Non-birthing parents with high parenthood-related anxiety were more likely to desire digital perinatal education on their own emotional health and were linked to a birthing parent with high-pregnancy anxiety compared to those without high parenthood-related anxiety. These findings suggest that non-birthing parents are amenable to receiving comprehensive perinatal education and mental health support through digital health platforms. Additional data are needed as to whether digitally delivered perinatal education or mental health support result in improved perinatal outcomes for non-birthing people.

Tweetable statement:

Most non-birthing parents desire digital perinatal education & mental health support. Rates of non-birthing parents’ parenthood-related anxiety are higher if the birthing parent has pregnancy-related anxiety.

AJOG at a Glance.

- Why was this study conducted?

- To examine perinatal educational preferences among non-birthing parents overall and whether these preferences differed in the setting of high parenthood-related or birthing parent’s pregnancy-related anxiety.

- What are the key findings?

- Among 382 non-birthing parents, most desired to receive perinatal education and mental health support, and >40% desired education on their own emotional health.

- Non-birthing and birthing parents had similar rates of high parenthood-related or pregnancy-related anxiety, respectively.

- Non-birthing parents preferred similar perinatal education irrespective of pregnant-related anxiety in the birthing parent.

- What does this study add to what is known?

- Prior research has demonstrated that perinatal anxiety is common in birthing and non-birthing parents

- Our findings suggest that perinatal mental health support is needed for nearly all parents and that non-birthing parents who utilize digital health platforms are amenable to receiving comprehensive perinatal education via these platforms.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest/Funding:

Dr. Lewkowitz has served on a medical advisory board for Pharmacosmos Therapeutics, Incorporated in 2022 and on a medical advisory board for Shields Pharmaceuticals in 2021 and is supported by the NICHD (K23HD103961). Dr. Ayala is a recipient of the Robert A. Winn Diversity in Clinical Trials Career Development Award, funded by Gilead Sciences. Dr. Miller is supported by the NICHD (R01HD105499). These sources had no role in study design, data interpretation, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Ms. Rubin-Miller and Drs. Jahnke and Henrich are employed by Maven Clinic. Dr. Guille is a Maven Visiting Scientist and receives consulting honorarium from Maven Clinic.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Works Cited

- 1.Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;210:315–323. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Philpott LF, Savage E, FitzGerald S, Leahy-Warren P. Anxiety in fathers in the perinatal period: A systematic review. Midwifery. Sep 2019;76:54–101. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2019.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yonkers KA, Vigod S, Ross LE. Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and management of mood disorders in pregnant and postpartum women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;117:961–77. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821187a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. Anxiety Disorders Among Women: A Female Lifespan Approach. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). Spring; 2017;15(2):162–172. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20160042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulson JF, Bazemore SD. Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: A meta-analysis. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(Suppl:1961–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luoma I, Puura K, Mäntymaa M, Latva R, Salmelin R, Tamminen T. Fathers’ postnatal depressive and anxiety symptoms: An exploration of links with paternal, maternal, infant and family factors. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;67(Supl 6):407–13. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2012.752034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman JH. Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family health. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;45:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis CL, Ross L. Women’s perceptions of parent support and conflict in the development of postpartum depressive symptoms. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;56:588–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ansari NS, Shah J, Dennis CL, Shah PS. Risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms among fathers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2021;100:1186–1199. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher SD, Cobo J, Figueiredo B, et al. Expanding the international conversation with fathers’ mental health: toward an era of inclusion in perinatal research and practice. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2021:Online ahead of print-Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s00737-021-01171-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher ML, Sutcliffe P, Southern C, Grove AL, Tan BK. The Effectiveness of Interventions for the Prevention or Treatment of Paternal Perinatal Anxiety: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. Nov 8 2022;11(22)doi: 10.3390/jcm11226617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hing E, Albert M. State Variation in Preventive Care Visits, by Patient Characteristics, 2012. NCHS Data Brief. Jan 2016;(234):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guidelines for Perinatal Care: 8th Edition. American College of Obstetricans and Gynecologists & American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewkowitz AK, Griffin LB, Miller ES, Howard ED. A Missed Opportunity? How Prenatal Care, Birth Hospitalization, and Digital Health Could Increase Nonbirthing Parents’ Access to Recommended Medical and Mental Healthcare. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. Oct-Dec 01 2022;36(4):330–334. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tebb AJ, Ng V, Tay L. A review of key Likert scale development advances: 1995–2019. Front Psychol. 2021; 12:637547. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.637547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Team. RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Accessed December 19, 2022, 2022. https://www.r-project.org/

- 17.Wynter K, Rowe H, Fisher J. Common mental disorders in women and men in the first six months after the birth of their first infant: a community study in Victoria, Australia. J Affect Disord. Dec 2013;151(3):980–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.“Demographics of Mobile Device Ownership.” Pew Research Center. Washington DC: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pew. Digital divide persists even as lower-income Americans make gains in tech adoption: 2021. October 14, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/06/22/digital-divide-persists-even-as-americans-with-lower-incomes-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/