Abstract

Background: Nearly a quarter of Canada’s population suffers from chronic pain, a long-lasting medical condition marked by physical pain and psychological suffering. Opioids are the primary treatment for pain management in this condition; yet, this approach involves several undesirable side effects. In contrast to this established approach, non-pharmacological interventions, such as medical hypnosis, represent an efficient alternative for pain management in the context of chronic pain. HYlaDO is a self-hypnosis program designed to improve pain management for people with chronic pain.

Purpose: This research aimed to evaluate the HYlaDO program based on the proof-of-concept level of the ORBIT model and investigated participants’ subjective experience.

Research design: Qualitative study.

Study sample: Seventeen participants with chronic pain took part in this study.

Data collection: We conducted individual semi-structured interviews with patients who had participated in HYlaDO to identify the three targets of desired change: pain, anxiety and autonomy in self-hypnosis practice.

Results: Thematic analysis revealed that the practice of hetero-hypnosis and self-hypnosis decreased (i) pain and (ii) anxiety. Also, it (iii) indicated the development of an independent and beneficial self-hypnosis practice by having integrated the techniques taught.

Conclusion: These results confirm that the established targets were reached and support further development, implementation and scaling up of this program. Consequently, we believe it is justified to move to the next step of program development.

Keywords: Hypnosis, chronic pain, anxiety, group intervention, qualitative study

Introduction

Chronic pain

In Canada, nearly a quarter of the population suffers from chronic pain, a medical condition marked by long-lasting physical pain and psychological distress. 1 Chronic pain represents a personal burden. It can transform even the most mundane tasks into insurmountable challenges. Unfortunately, waiting times for patients suffering from chronic pain can be long. For example, in Quebec, delays for an appointment in a pain clinic can be as long as 5 years. 2

Chronic pain is complex to treat. Multidisciplinary approaches are often considered to be key treatment of chronic pain. 3 However, pain management for chronic pain is often done using solely opioids. 4 Yet, this exclusively pharmacological approach yields several undesirable effects, including constipation and central nervous system depression, with the risk of developing opioid tolerance, dependence and addiction that may lead to substance abuse, overdose and death. 4 Thus, there is a need for more readily available strategies for chronic pain management. In this regard, the development of non-pharmacological interventions for chronic pain is highly desirable.

Medical hypnosis

Research shows that medical hypnosis represents an efficient non-pharmacological intervention.5–8 Clinically and statistically significant effects for pain management have been observed in several clinical populations suffering from chronic pain, including patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia, arthritis and cancer. 9 Furthermore, hypnosis is one of the non-pharmacological interventions that provide the advantage of maintaining effects over a longer period of time.9,10 In addition to pain reduction, hypnosis can offer additional effects such as reduced anxiety, better sleep and improved quality of life.5,11 In short, hypnosis represents a viable treatment option for chronic pain.

Contrary to hetero-hypnosis, which is defined by the accompaniment of the patient by an operator – that is, a clinician performing the intervention. self-hypnosis is characterised by hypnotic induction and suggestion procedures performed by the patient himself. In this fashion, self-hypnosis promotes better self-management of chronic pain beyond therapeutic sessions with a health professional. 12 Self-hypnosis training rests on two key elements, namely, the instructions for practicing self-hypnosis and audio recordings. 13 However, despite its apparent efficiency, self-hypnosis training remains mostly unexplored. 9 In particular, there is little information in the literature about the optimal way to provide instructions for self-hypnosis practice. The present work aims to address this shortcoming by continuing the development of a new standardised program called HYlaDO (HYpnose de la DOuleur, Hypnosis of pain in French). This new program is a self-hypnosis training program specifically adapted for chronic pain management. The present study is part of a preliminary evaluation using a qualitative approach to determine the validity of our program.

ORBIT model and design of HYlaDO – stage Ia

The development and evaluation of HYlaDO follows the methodology of the Obesity-Related Behavioural Intervention Trials framework.14,15 This framework comprises four distinct phases. First, there is the design phase. It is subdivided into two separate stages. The first stage involves defining the design of the program to establish the scientific basis of the proposed intervention. We previously carried out this first stage. 16 In fact, the development of the HYlaDO program was modelled after a program developed in oncology. 17

In approach used in oncology, each training session involves a hypnosis exercise. We adapted four of the five exercises of the oncology program and replaced the remaining one. To various degrees, these exercises aim to reduce stress and pain. We further refined them based on previous literature. 18 In our program, each training session was conducted via videoconference using the Zoom platform. During these sessions, a health professional trained in medical hypnosis performed one of the five hypnosis exercises with the patients.

For the first exercise, the ‘backpack technique’, patients are asked to imagine themselves emptying a heavy backpack to achieve lightness. 19 In this scenario, the weight of the backpack represents negative elements in their lives, mainly emotions and pain. The second exercise is called ‘doing nothing’ and focuses on acceptance. Here, the suggestions and metaphors evoke themes of relaxation and meditation in a pleasant place, as well as letting go. The third exercise rests on visualisation techniques to reduce their pain experience via metaphors. For example, a needle can represent pain and be transformed into something more tolerable, even pleasant, such as a feather. The fourth exercise rests on imagining a magic hand to relieve the pain. Lastly, the fifth exercise is inspired by a protocol developed by Rossi and capitalises on the patient’s resources and strengths to overtake the negative affects. 18 The goal of this exercise is to restore participants’ confidence in self-managing their pain.

The Hylado program is composed of 5 sessions performed by zoom with maximum 8 participants, during which we propose the 5 exercises mentioned. Each session lasts 90 min and is composed as follows. 1- Welcome the patients and discussion of their condition, that is, pain, difficulties encountered, practice of the exercises (20 min). 2- Introduction of the session’s exercise and explanation of its use, in accordance with the above-mentioned explanations (10 min). 3- Hypnosis exercise (40 min). This hypnosis follow the same general five steps pattern: An induction procedure that yields a trance experience; that is, a state of increased concentration, focused on internal phenomena, accompanied by a decrease in receptivity to external stimuli; the deepening of the trance; suggestions for desired changes such as relaxation or visiting an imaginary place; post-hypnotic suggestions aiming to extend the duration of the effects; and finally the return an alert state 4- Feedback with the participants (20 min), Figure 1 describes the intervention protocol of HYlaDO.

Figure 1.

Intervention protocol of HYlaDO.

In our program, self-management of chronic pain could be done in two ways. Patients were provided with audio recordings of the hypnosis sessions and were given instructions for practicing self-hypnosis. For this self-practice, we proposed to them either to listen to the audio recordings or to perform the exercise alone following the hypnotic framework that we had presented them. Patients were encouraged to practice without the audio recording and replicate the steps of the zoom sessions. Additionally, time was allotted for discussion during each hypnosis session where patients could share their experiences and ask questions. During this time, the hypnotherapist also shared more theoretical dimensions of hypnosis as well as tips on how to practice self-hypnosis.

ORBIT model and refinement of HYlaDO – stage Ib

The second stage of the first phase of the ORBIT model involves refining the intervention by collecting opinions and recommendations from the participants. We previously refined the HYlaDO program through a qualitative study. 16 This previous work focused on the social validity of the program, including the relevance and acceptability of the program, the expected and perceived effects, and the participants’ recommendations. This work also allowed us to uncover several themes pertaining to the participants’ perspectives, thereby allowing us to improve the program accordingly and to proceed confidently with the next phase of development. Note that the general structure of the program, that is, the training, the exercises and the structure of the exercises remained as described in the previous section.

ORBIT model and proof of concept of HYlaDO – stage IIa

The present study was part of stage IIa of the ORBIT framework, namely the proof of concept. It is not aiming to assess if the intervention produces statistically significant effects. This stage aims to determine whether the proposed treatment can achieve desired and notable clinical change. Therefore, the current work seeks to establish whether preliminary evidence supports the effectiveness of the program on a small scale. Ultimately, the early phases of the ORBIT model determine if the program has enough potential to proceed with subsequent phases and if so, they also serve the purpose to familiarise oneself with the testing process of the program to ensure the quality of subsequent studies. 15

For the proof of concept, we used a qualitative design to investigate the participants’ accounts of practice, particularly their self-hypnosis practice. This kind of design allowed us to investigate holistically the participants’ narrative and to make an in-depth analysis in a small sample.20,21 This made it possible to evaluate if they had acquired a clinically meaningful self-hypnosis basis for the management of their chronic pain and other related challenges. The procedure arranged under these designs allowed each patient to mention what is clinically meaningful for him/her by describing what is helpful and what isn’t.

As for the practice of self-hypnosis, there are no formal recommendations concerning the practice targets to be reached to the best of our knowledge. In this regard, the interviews allowed for exploratory flexibility.

Finally, we pre-established three objectives to evaluate our program at this stage. We evaluated our program to determine if hypnosis and self-hypnosis elicited (i) a decrease in pain; and (ii) a decrease in anxiety. Also, we evaluated if our program permitted (iii) the development of an independent and beneficial self-hypnosis practice by integrating the taught techniques.

Objectives

The present study investigates participants’ subjective experience following their hetero-hypnosis and self-hypnosis practices in the context of the HYlaDO program. In this effort, we evaluated if hetero-hypnosis and self-hypnosis elicited (i) a decrease in pain; and (ii) anxiety. Also, we evaluated (iii) if the participants had developed an independent self-hypnosis practice by integrating the taught techniques into their daily life for the management of chronic pain and other related challenges.

Materials and methods

Recruitment of participants

Thirty patients completed the self-hypnosis training program based on the following inclusions criteria for our study: Suffering from chronic pain, speak French, followed at the pain clinic of our hospital. Exclusion criteria were patients who had previous self-hypnosis practice and those who had problems that might interfere with verbal comprehension, that is, people with hearing loss and/or altered cognition (for neurological or psychiatric reasons). The entire group of patients in the training program was solicited via a short presentation of the project during a Zoom session as well as an e-mail describing it. Twenty-three patients consented to participate in our study which was approved by our institution Research Ethics Committee (#2022-2741).

Materials and procedures

An emergent thematic analysis method was used for this project. While the intervention sessions are delivered by zoom, we conducted the study evaluations in our lab. Measures included the completion of questionnaires, the hypnosis session with physiological measurements and a semi-structured interview. In the current study, we focused on the socio-demographic and clinical questionnaires, as well as interviews. We collected socio-demographic information about the patient’s age, their gender, marital status, number of children, level of education and occupational status. The clinical portion of the questionnaire asked for a brief description of the chronic pain problem, the diagnosis and their average level of pain using a scale ranging from 0 to 10. The semi-structured interview focused on the participants’ account of their hetero-hypnosis and self-hypnosis practice and was conducted by a research assistant not involved in the clinical portion of the program.

An interview grid — covered major themes of their practice while permitting freedom in the structure of the interview. Thus, the narrative of practice of each participant could emerge according to their own point of view. The interview was divided into sections, one about hetero-hypnosis and another one about self-hypnosis. The questions focused on how they practiced each of these, and what they got out of the practice. All interviews were audio-recorded and lasted about 30 min on average (min 11 min – max 48 min). The reasons for a short interview are: less talkative participants, people with less intense hypnotic experience, people with deep hypnotic experience and amnesia of the hypnotic experience and people who did not practice self-hypnosis, had less to report.

Analysis

The socio-demographic and clinical data were analysed using descriptive statistics. For our qualitative study, we needed to interview a minimum number of 12 participants to reach saturation. 22

Saturation means that no additional data are being found whereby the researcher can develop properties of the category. As the researcher sees similar instances over and over again, he becomes empirically confident that a category is saturated. 23 In this study, our sample consisted of 17 participants.

The qualitative data collected were processed and encoded using QD Miner software. An emergent thematic analysis method was used, and the transcript coding process followed these steps: 1- encoding of the transcript by the two authors (RC, AEJ) separately; 2- completion of two meetings to discuss and evaluate the interrater agreement and the selections of themes between the authors by consensus (RC, AEJ, EC, DO); 3- recoding of the transcript following each meeting, based on established guidelines and code descriptions; 4- development of the hierarchy of the three central themes (parents’ experience, evaluation of the program, suggestions for improvement); 5- reduction and synthesis of the data for each theme; 6- a preliminary drafting of the results incorporating quotes that had been transcribed without the markers of spoken language to allow for a more fluid reading. 24

Participants are identified using alphanumeric codes (P1 to P17). The results of the qualitative data are presented in a narrative format in which participants are identified using alphanumeric codes (P1 to P17). 24 Quotations have been incorporated into the text in italics and in quotation marks.

Results

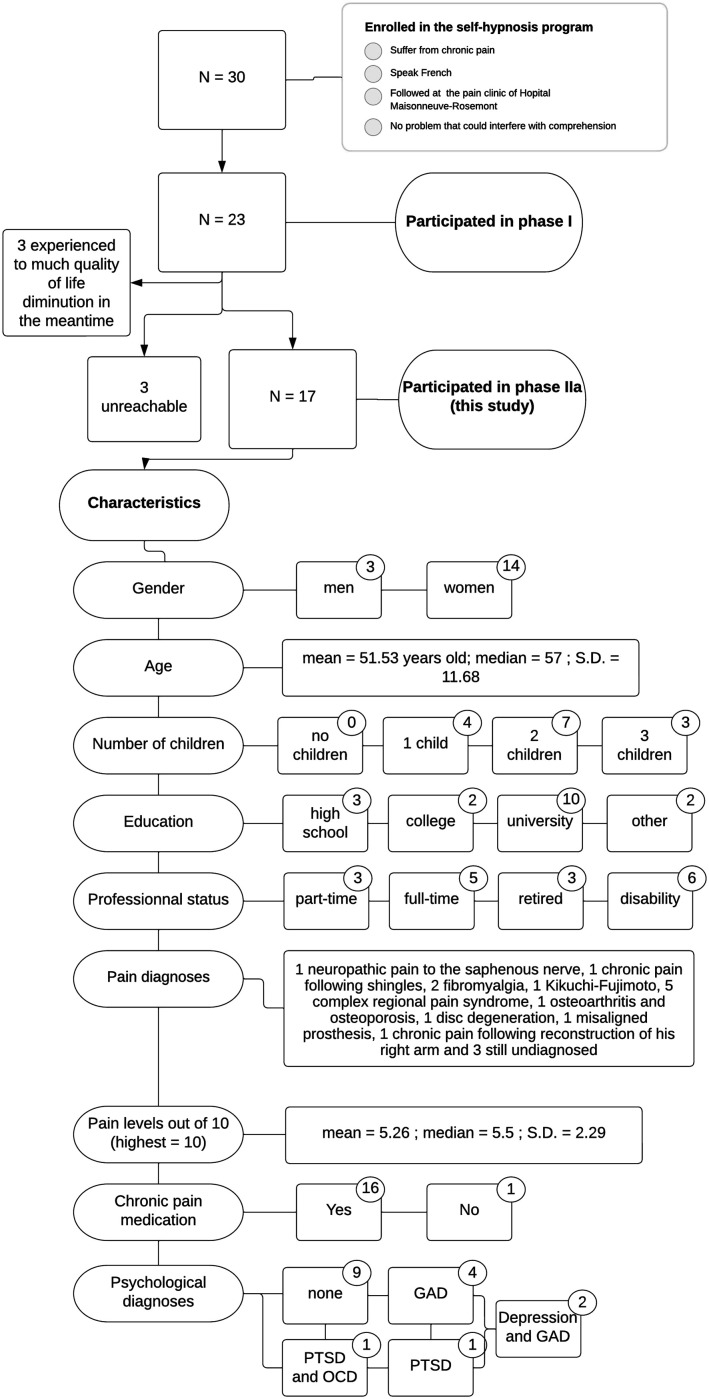

Of the 30 eligible participants in this study, 23 consented to the study. Ultimately, our sample consisted of 17 participants. The 6 dropouts were 3 participants who had suffered a significant decrease in quality of life in the meantime, and 3 participants who were unreachable at the invitation to the study visits. The final sample (N = 17) included 3 men and 14 women, all of Canadian nationality. All suffered from chronic pain. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart, demographic and clinical data. Notes: GAD: generalised anxiety disorder; OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder.

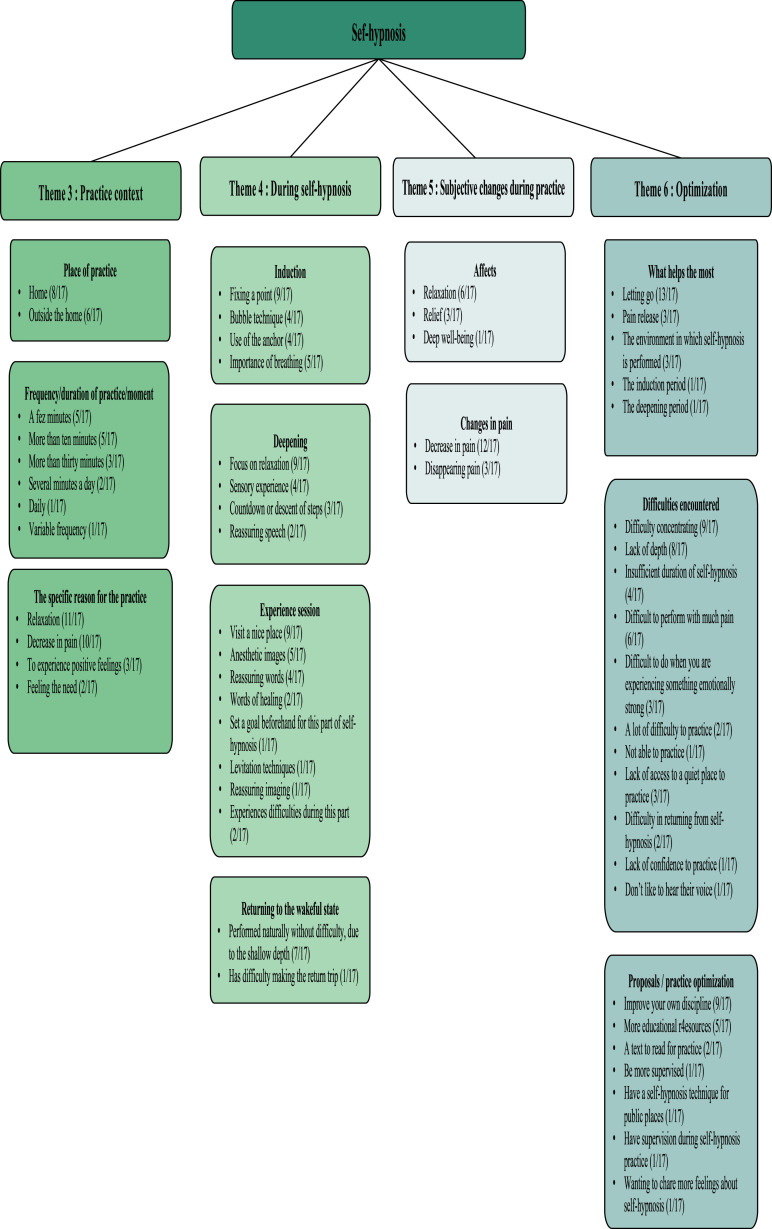

In this result section, we present the qualitative data according to 6 themes with a total of 17 codes. The first two themes relate to hetero-hypnosis practice. Theme 1 denotes the subjective experience during the practice of hetero-hypnosis while theme 2 includes aspects of the practice that are appreciated and that could potentially be improved. The other themes concern the practice of self-hypnosis. Theme 3 addresses the contextual elements of their practice, such as their motives for practicing at a given time. Theme 4 addresses the stages of the hypnotic process, from induction to return to wakefulness, during a self-hypnosis session. Themes 5 and 6 mirrored the components from themes 1 and 2, but in the context of self-hypnosis. Figures 3 and 4 summarise the overall qualitative results. Finally, please note that some modifications have been made to some statements to ensure appropriate syntax without changing the meaning.

Figure 3.

Practice of hetero-hypnosis.

Figure 4.

Practice of self-hypnosis.

Practice of hetero-hypnosis

This section concerns the practice of hetero-hypnosis during the sessions on Zoom with the hypnotherapist. The subtitles correspond to the codes.

Theme 1: subjective changes during practice

Changes in pain

Regarding changes in pain, in hetero-hypnosis, most of the participants (10/17) mentioned having a marked reduction in pain. In addition, a majority (10/17) also reported experiencing no pain during hetero-hypnosis. P11 (woman, 58 years old) mentioned: ‘It’s impressive how I can get myself to be pain-free’.

Negative affects

Among the comments addressing negative affect, the vast majority (12/17) reported being able to benefit from the relaxing effects of hetero-hypnosis and have noticed a decrease in their stress and/or anxiety level. For example, P12 (woman, 58 years old) said: ‘It's like feeling somewhere else. I feel like less anxiety, less stress’.

Positive affects

In terms of positive affect, several were mentioned and identified. First, a large majority of participants reported experiencing the dissociative state pleasantly (14/17). P7 (women, 36 years old) mentioned: ‘You see, you are a person, you are like in another person's body. Afterward, you come back to your body...to your own body’.

Almost all (16/17) reported experiencing lightness and zenitude during hetero-hypnosis. In this regards, P16 (man, 58 years old) reported: ‘I find it important to do it because I feel so zen’.

Joy was mentioned multiple times (15/17). This joy was often associated with places explored or autobiographical memories, or even hybridisation between imagination and memory. For example, P17 (woman, 55 years old) mentioned: ‘I usually fall back to a small village of my grandmother. That I would go like when I was happy. That was my vacation’.

A minority (7/17) also reported a change in perspective under hetero-hypnosis. P20 (woman, 58 years old) illustrates this well: ‘a kind of opening in my, in my thoughts, in my way of seeing my day’.

In addition, several participants reported a gain in energy (5/17). For example, P1 (woman, 37 years old) said, ‘I feel more energized’.

Finally, two participants (P16 and P19, woman, 53 years old) explicitly linked positive feelings to their physiological activities. For example, P20 said: ‘Sometimes I do different ideas in my head too, to get deeper and deeper. But really, I take a breath. Then, when I explain, I really feel my body and my brain activity slowing down with each breath. Then after that, it's like when there’s a story, there, it's like I’m floating’.

Theme 2: optimisation

Facilitators: ‘What helps the most?’

When referring to what helped the most through the practice, some (4/17) mentioned specificities about their pain. P14 (woman, 59 years old) mentioned: ‘It’s being able to control these pains, they disappear’. Some others (7/17) mentioned relaxation as the most helpful benefit they derived from hetero-hypnosis. For example, P21 (woman, 33 years old) said: ‘But it's relaxation, I think, because it helps everything. With stress, relaxing, with pain’. Other participants commented on specific aspects that aided relaxation and well-being. P15 (woman, 57 years old) specified that it was ‘the story [told]’, P17 noted that it was ‘when [he] looks for a place where [he] feels good’, while P10 (man, 31 years old) noted that it was the induction that ‘makes him feel the best’.

Several participants (7/17) emphasised the benefits they derived from the imagery evoked and their imagination during hypnosis. Some (6/17) mentioned greatly benefiting from the guidance of the hypnosis session, that is, the hypnotic speech from beginning to end, as opposed to self-hypnosis. A minority (4/17) also targeted dissociative states as their most beneficial state.

Finally, more contextual factors that helped their practice were named. Four participants noted that they appreciated the control of the environment in which they did their hypnosis session delivered via Zoom. Two participants (P1 and P10) noted that it was being able to ‘anchor it in a routine’ (P1) that helped them the most. One participant (P9, woman, 56 years old) named the synergy of the hypnosis group as the most helpful.

Obstacles: ‘What Helps the Least?’

Among the factors identified as least helpful or most challenging, a significant number of participants (7/17) noted outside noise and/or distractions. Four noted difficulties paying attention throughout the session. For example, P18 (woman, 39 years old) said, ‘I don’t stay focused on what you are saying’.

Some (4/17) mentioned having difficulty with pain. P10 mentioned that exercises involving the hands were more difficult. P12 noted having more difficulty ‘if the hypnosis session starts when [he] feels a peak of pain’.

The difficulties associated with hetero-hypnosis are mostly idiosyncratic. P7 reported feeling apprehensive about hypnosis at first. P10 and P12 reported having more difficulty when anxious. P4 (woman, 69 years old) felt compelled to do the anchoring. P11 named not liking having to come out of hypnosis. P9 found the sessions repetitive. P18 noted having difficulty breathing the right way at first. Finally, P12 named periodically having difficulty getting the desired hypnosis due to a particular event in her life.

Practice of self-hypnosis

This section concerns the practice of self-hypnosis. Fifteen of the 17 participants practiced some form of self-hypnosis, ranging from short induction to a practice approaching the full hypnosis sessions. The two participants who did not use self-hypnosis reported difficulties associated with this self-practice. The reasons are described in the results below. Figure 4 resumes this theme.

Theme 3: practice context

Place of practice

A portion (8/17) of the participants mentioned that their place of practice was at home, while some (6/17) also noted practicing self-hypnosis outside of their house. This included transportation (4/17), at work (3/17), and while waiting for an appointment (P17).

Frequency/duration of practice/time of the day

In total, 11 participants mentioned the duration of their self-hypnosis. For some (5/17) sessions of self-hypnosis lasted a few minutes, for others (5/17) more than 10 or 15 min. For some (3/17), it was more than 30 min. Note that among the participants beyond 30 min, they also mentioned having occasional shorter self-hypnosis sessions, lasting between a few minutes and more than 10 min. Four participants had comments about the frequency. For P21 and P10, it was several times a day. For P11, it was daily and for P9, it was a frequency that varied from daily to long breaks. As for the time of the day chosen, 5 participants mentioned some favourite moments. Four mentioned preferring evenings, 3 mentioned the afternoon and 2 mentioned the morning.

Specific reason for practice

Some patients identified the reasons for practicing self-hypnosis. Most of them (11/17) mentioned relaxation as a reason for practicing. For example, for P4 it is ‘relaxation before going to sleep’ while for P7 it is ‘especially when [she] is very anxious and worried about some outcome, which [she] had regarding [her] health or some other news’.

Also, 10 participants named pain reduction as a reason for practice. For example, P16 said, ‘I will often do it often when I have an [pain] attack’.

More exceptionally, a few participants (3/17) mentioned doing it to get something positive out of it, whether it was to get good energy or comfort. Two participants (P2, men, 59 and P23, woman 49 years old) mentioned doing it when they felt the need.

Theme 4: during self-hypnosis

Induction

There were mentions of the induction process in self-hypnosis. The majority (9/17) reported using the fixed point as their preferred method of induction. P20 mentioned: ‘A lot of times I look at a point, I stare at a point, then I breathe in. Then I concentrate on how my tongue is placed in my mouth’.

One participant (P12) also has another induction method during her self-hypnosis practice, the bubble technique, which consists in imagining a balloon that deflates in your hands. During the induction period, four participants also noted using anchoring. Several mentions (5/17) were made to emphasise the role of breathing during this phase. P12 illustrated it in this way: ‘I need to settle down for a moment. I need to bring my breath down. I need that energy there flowing through me’.

Deepening

In the deepening phase, a majority (9/17) named focussing on relaxation, mainly through breathing to increase the depth of their state. For example, P20 mentioned: ‘Then I tell myself with each breath, I am even deeper’.

Four participants mentioned using their senses during this time. One participant (P12) mentioned using all five senses. The other three mentioned opting for a body scan. P16 provided a good description of the process: ‘After that, all, this relaxation, I go down. After that, at the level of the mouth, at the level of all the muscles of the mouth, which relaxes, the jaw is softening. Then there, it goes down my neck, my shoulders, it goes down, going in the arms until every part of my body comes to relax. Then, I go down the column, I go down to the toes, that every part of my body is the most relaxed possible, with breathing’.

Three participants named using counting down or descending techniques during the deepening. For example, P20 mentioned: ‘There you know, I go down, I tell myself the numbers, then I go down’ or ‘Then after that, sometimes, I take an elevator’.

Finally, two participants (P21 and P18) mentioned opting for a reassuring speech during this phase. In this regard, P21 said: ‘I tell myself it’s going to be okay, then, you know, it’s okay. It’s there, it’s going to go. Then there, you know, I imagine something good there that I feel’.

Experience session

A majority of participants (9/17) reported imagining visiting pleasant places during their self-hypnosis sessions. For example, P17 mentioned: ‘For me, the quietest times are when I'm looking for a place where I feel good. Yeah, I’ve lived at the beach a lot, so sometimes I go to the beach, but that’s just the way it is. I’ve seen it before. I prefer to go to a place where there is a lot of flora, plants, where I can breathe, feel the life of the smells, whereas usually here I am stuck. [Interviewer: What kind of smells?] Lavender. Yes, yes, there are many smells too. I have the smell of lemongrass that I loved when I was in my grandmother’s house’.

In addition, some participants (5/17) mentioned invoking anaesthetic images in their imagination. For example, P10 mentioned: ‘I try to imagine myself as if... it sounds strange to say, but as if I had air or water or something cold’. P11 also had some interesting things to say about this: ‘Then when I’m really in pain, that’s when I go and get my techniques that I've learned. You know how I tell you. I see my hand; I see my skeleton. I bring a hand that comforts. I see the machines to take away the pain. I’m going to do everything according to what I’ve learned. I think I'm really putting it into practice’.

Four participants also reported using reassuring and/or empowering language during this phase. For example, P23 said, ‘So I value myself. I know I'm capable. I'm good’. Two participants (P4 and P7) mentioned using healing words: ‘I tell myself that I have no more pain, that my nerves are completely healed. Then I repeat words like that to myself’ (P4).

Some participants noted specifics to their practice. P12 mentioned setting a goal to achieve during the post-hypnotic experience. This goal was set with the self-hypnosis session. P20 used levitation techniques during her self-hypnosis session. P11 used reassuring imagery in the form of a protective envelope to provide comfort.

On the other hand, two participants (P22, woman 64 years old and P21) noted difficulties. For example, P22 said, ‘You know, I try to talk to me, say well, get you to a place, you know, like what you’re telling me, I try to do it to myself. But I don’t seem to be getting on board’.

Returning to the waking state

The participants (7/17) who mentioned returning from their hypnotic trance named doing so naturally and quietly. For example, P21 mentioned: ‘You know how much better I feel. I’m kind of aware that I’ve had enough. It’s really automatic. You know, I just feel; I feel awareness; I feel less stressed; I feel less pain’. A recurring aspect is the ease of return because of the shallow depth. It is well illustrated in the words of P22: ‘As I was saying earlier, I’m not as deeply gone. So it’s easy to come back’.

One participant, P12, reported difficulty with the return to wakefulness. It is important to note that this participant had self-hypnosis sessions that were the longest and seemed the deepest. P12 mentioned: ‘Getting back up is hard. And then getting out because you know, you have to. There’s a point where, you know, the steps are there to get out, to get back in. But there are times when I feel like I haven’t respected those steps. Then it’s harder for me during the day, afterward to get back on track’.

Theme 5: subjective changes during practice

Changes in pain

During the self-hypnosis practice, changes in the participants’ pain were reported. Some participants (12/17) mentioned that their pain had decreased during their self-hypnosis practice. This expression of their relief was expressed for P21 in the following way: ‘It helps me to relax my muscles, it helps me to relax the places where I have pain. Then I manage, you know the pain stays there, but it's like different’. In the case of P17, it was as follows: ‘If I do this, I will reduce my pain, and for sure I reduce my pain’. In a few cases (3/17), the complete disappearance of the pain was sometimes observed. For example, for P20: ‘Then, there, my knee is so relaxed. Then the pain goes away.’

Affects

In terms of what was felt emotionally, a minority of participants (6/17) mentioned relaxation during their practice. P7 mentioned: ‘It relaxes me completely’. In addition, a few participants (3/17) mentioned relaxation that evolved into relief. P12 mentioned: ‘Then when I succeed there, I see myself smile. I feel it, I feel good. Then it’s not just relaxing the muscles in my face. I feel a calmness in my body’. One participant also mentioned getting deep well-being from her self-hypnosis practice. In her words: ‘It’s really an exponential inner well-being’ (P12).

Theme 6: optimisation

What helps the most

The majority (13/17) named ‘letting go’ as what was most beneficial to them with self-hypnosis. For example, P22 highlighted this as follows: ‘Well, it’s the feeling of saying, look leave everything that’s there back and try to go get yourself. Try to imagine something that can give you serenity.’ In addition, three participants indicated that the release of pain during their practice helped them the most. Three participants noted contextual elements of their self-hypnosis that made it more optimal. They emphasised the environment in which they did their self-hypnosis practice, a place that had to be calm. Two participants (P7 and P10) referred to two moments in their self-hypnosis sessions as being most beneficial to them: induction and deepening.

Difficulties encountered

Several difficulties were reported with the practice of self-hypnosis. First, most of the participants (9/17) reported having difficulties concentrating during their self-hypnosis session. Several elements were named such as a disturbing environment, intrusive thoughts and not having the hypnotherapist's voice to guide them. Second, 8 participants also reported not being deep enough during self-hypnosis sessions compared to audios or hetero-hypnosis. Third, 4 participants mentioned that they were not satisfied with the duration of their self-hypnosis as they found it too short. Fourth, some participants (6/17) reported having difficulties adequately performing self-hypnosis when they experienced a lot of pain. As P9 said: ‘Sometimes it’s too strong and I can’t get a handle on it.’ Fifth, some participants (3/17) mentioned that they had difficulties entering self-hypnosis when they were experiencing something highly emotional. For example, P10 said, ‘When I'm anxious, I have a hard time with that actually.’ Sixth, some participants (3/17) mentioned having a lot of difficulties in general (P11 and P7), or even not being able to practice self-hypnosis (P22). In these cases, they mentioned a habituation to the audio recordings causing their failures to use self-hypnosis. For example, P7 mentioned: ‘I must have been so used to the audios that I told myself that without the audio, it doesn’t work.’ Seventh, three participants noted spatiotemporal elements negatively affecting their practice. Essentially, practicing without access to a comforting and quiet place was difficult. Eighth, two participants stated difficulties with the last step their self-hypnosis session, returning to the waking state. Finally, two participants had unusual difficulties. P7 mentioned a lack of confidence and a fear of getting stuck in hypnosis. P11 noted that she was able to do the self-induction but did not like to hear her voice afterward.

Proposal – practice optimisation

A few elements relating to the optimisation of self-hypnosis practice were noted. First, a majority of the participants (9/17) mentioned wanting to improve their discipline regarding their practice. Five participants expressed a desire to have more educational resources in the program. P15 mentioned: ‘A little summary of how to do it. That would definitely help me a lot’. In the same vein, P21 and P12 mentioned that they wanted a text to carry out their self-hypnosis. Interestingly, P12, after finding texts for self-hypnosis, recorded herself reading them. This allowed her to further internalise the techniques and become accustomed to her voice. The others who expressed this desire to have more educational resources did not specify any other solutions.

Several participants added other elements to improve their self-hypnosis practice. One participant (P14) mentioned wanting more guidance in her sessions. P17 affirmed wanting a self-hypnosis technique that would be easier to use in public places and have the effect of a protective barrier from her environment. P7 mentioned wanting to have supervision during self-hypnosis. Finally, P12 wanted to share more feelings about self-hypnosis in group meetings.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the subjective experience of participants in their practice of hetero-hypnosis and self-hypnosis following their enrolment into the HYlaDO program for patients with chronic pain. In the ORBIT framework, the current study is the proof of concept – which evaluates the potential benefits of this intervention.

In this regard, we established three objectives. We questioned participants about their perception of hetero-hypnosis and self-hypnosis effect on their levels of (i) pain; and (ii) anxiety. Furthermore, we evaluated (iii) if the participants had developed an independent and beneficial self-hypnosis practice by having integrated the taught techniques into their daily life for the management of chronic pain and other related challenges.

We will discuss our results under the light of these objectives. This will be done according to the themes related to hetero-hypnosis and then, according to the themes related to self-hypnosis. Note that some additional remarks concerning ways optimise the program.

Hypnosis themes – objective attainment

Theme 1 (Subjective Changes During Practice; Theme 1) and theme 2 (Optimisation; Theme 2) are germane to the objective of the program targets relative to hetero-hypnosis. Here, evidence shows that we attained our clinical objectives as most patients reported both a decrease (i) in pain experience and (ii) anxiety during hetero-hypnosis as reported in Theme 1.

In theme 1, they also described feelings of relaxation and several positive affects such as joy, lightness, broadening of consciousness and a gain in energy. This outcome is consistent with the idea that hypnosis can offer additional benefits for treating chronic pain patients more holistically. Furthermore, these benefits of medical hypnosis are of interest to individuals diagnosed with chronic pain because they often also struggle with emotional distress.5,9,25 Additionally, relaxation aspect of hetero-hypnosis decreases patient’s stress level – a psychological factor that enhances the experience of pain. 26 In the same vein, positive affects in the context of medical hypnosis promote better pain management. 27 Specifically, in the context of chronic pain, positive affects bolster several key factors relative to the outcome of the treatment, such as motivation, readiness to change and coping self-efficacy. 27 Hence, additional emphasis on the integration of positive affects during the hypnotic procedure could potentially improve the clinical efficacy of the HYlaDO program.

Self-hypnosis themes – objective attainment

The themes relevant to achieving the program targets in the self-hypnosis component are the following: Practice Context (Theme 3), During Self-Hypnosis (Theme 4), Subjective Changes During Practice (Theme 5) and Optimisation (Theme 6). We believe that this component of the program also achieves the objectives, although it leaves a larger window for optimisation. These objectives are (i) a decrease in pain with self-hypnosis practice, (ii) a decrease in anxiety with self-hypnosis practice and (iii) having developed an independent and beneficial self-hypnosis practice by having integrated the techniques taught.

We observed a (i) decrease in pain during self-hypnosis, as reported in Theme 5. Interestingly, this was also a reason for engaging into the practice of self-hypnosis, per Theme 3. However, in contrast to hetero-hypnosis, fewer participants mentioned experiencing pain disappearance (3/17 vs 10/17 when comparing Theme 5 and Theme 1). This difference potentially stems from the fact that patients fail to reach the same level of absorption and focus during the hypnotic trance during self-hypnosis compared to hetero-hypnosis.

Our study also confirms that (ii) the practice of self-hypnosis decreases anxiety. Here, participants reported that they experienced feelings of relaxation, with some indicating that they felt relieved. Relaxation was also mentioned as a reason to practice, per Theme 3. Furthermore, analysis of Theme 6 shows that a majority of participants indicated that ‘letting go’ represented the most helpful aspect of self-hypnosis. In sum, our research supports that participants were able to achieve a decrease in anxiety using self-hypnosis (i.e. Objective ii).

Our study also confirmed the attainment of Objective iii that assessed the development and the benefits of the independent practice of self-hypnosis in self-management of pain experience. This result supports the importance of this autonomous practice in pain management. This finding is also supported by research showing that hypnosis influences multiple neurophysiological processes involved in the experience of pain, and is similar to mindfulness meditation, which has immediate and long-term effects on cortical structures and activity involved in attention, emotional response and pain.25,28 In our study, patients indicated that they performed self-hypnosis in their home, with some practicing it outside of it. The practice of self-hypnosis outside their home demonstrates how this approach could counteract the negative impact of chronic pain on autonomy and mobility. 29 In this fashion, self-hypnosis facilitates movements and independence in the context of chronic pain. Additionally, although few participants discussed the frequency of practice, those who did revealed a great deal of variability. These autonomous sessions of self-hypnosis ranged from a few minutes to approximately 10 min, with a few reporting sessions that lasted over 30 min. However, we observed benefits even when the practice of self-hypnosis lasted just a few minutes. Furthermore, the thematic analysis revealed that the characteristic elements of a self-hypnosis session described in theme 4 also align with the third objective (iii). In fact, the participants named using many taught techniques in their self-hypnosis sessions. They were mostly able to perform the induction and the deepening. They were also mostly able to have an imaginary visit of a pleasant place or to use anaesthetic images. This is notable because these techniques are central to the exercises taught in the program. Overall, the return to a wakeful state was experienced smoothly by participants. However, the lesser depth experienced in self-hypnosis could explain the ease with which they perform this step.

In conclusion, Objective iii was attained. Most of the participants developed an independent and beneficial self-hypnosis practice by integrating the taught techniques into their daily life.

Comments on hetero-hypnosis and self-hypnosis practices

In accordance with the information provided by the participants, two observations from this study appear to have an impact on their practices of hetero-hypnosis and self-hypnosis. The first comment refers to the participants' access to the trance state. People with less access to this state report lesser effects of hetero-hypnosis practices and a lower motivation to practice self-hypnosis. In this case, suggestibility, which means the way the person receives suggestions, could be an explanatory variable. Studies have indeed shown that high suggestibility is associated with greater clinical benefits.30,31 This suggestibility was not studied in our research, which is a qualitative study evaluating the participants’ perception of hypnosis practices, but should be a moderating measure for clinical trials in hypnosis.

The second comment is the impact of the number of practices on hypnosis effectiveness on pain and anxiety. Studies show that a high number of practices allows patients to experience better effects of hypnosis. 5 In our study, we note that some participants practice less, often correlated with a poor response to hypnosis. These patients are those who appear to have the lowest suggestibility mentioned in the previous comment. For future clinical trials, it would be important to evaluate this practice in the context of a longitudinal study.

Limitations

Some limitations of the present study must be raised. The first limitation concerns hypnotisability, which was not measured in our study. Therefore, it is not possible to relate the different discourses of the participants to their degree of hypnotisability. This measure was not considered in our protocol because we wanted to assess the subjective experience of the participants. However, the measure of hypnotisability, which is recommended in clinical trials for the inclusion of participants and/or as a moderator of the effects, would permit in this study to clarify the results of participants with a slight hypnotic trance. This measure will be incorporated into our subsequent clinical trials. A second limitation is that the person who conducted the research interviews was also one of the two people who performed the coding. While this may be a bias in the analyses, we made this choice to allow for a better understanding of what emerged from the interviews. This choice is supported by qualitative research that indicates the credibility of integrating the researcher at different moments in the survey, such as the possibility of being both therapist and researcher. 32 A third limitation concerns the use of audio recordings. In fact, audio recordings are part of the HYlaDO program and were mentioned to be utilised by the patients, but we didn’t investigate their usage. Although the use of audio recordings is standard for self-hypnosis training, the effectiveness of their utility for self-hypnosis training has been questioned. 25 Note that the questioning concerns audio recordings as a teaching method and not the benefits of this practice as a full-fledged modality in a program. A final limitation concerns the study sample. It was only composed of patients from the pain clinic of a single hospital in the province of Quebec, Canada. This limits the representativeness of our study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we believe that the participants' discourse reflected the achievement of the desired clinical objectives at this stage. It also allowed us to identify several facets that could be optimised. With respect to the milestones set out in the ORBIT model, this justifies moving to the next stage, Phase IIb. This stage corresponds to a pilot study to investigate the presence of empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of HYlaDO, a standardise hypnosis training program on a small scale. With this pilot study, we will estimate effect sizes that will allow to calculate the sample size needed for a future clinical trial (ORBIT III).

More generally, this study highlights the importance to develop self-hypnosis programs in concert with the feedback of the patients. Qualitative methods provide unique and essential information for the design and refinement of novel interventions. This study illustrates the value of refining and assessing original non-pharmacological complementary approaches to improve self-management of chronic pain and reduce the burden of pain on the patients, health care professionals and the health care system.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital (MRH) Pain Clinic for allowing this study, as well as all the patients who participated. We also thank the research laboratory of anesthesiology of HMR and its director, Dr Philippe Richebé, for supporting this project.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributorship: Conceptualisation, D.O and M.A; methodology, D.O, Ph.R, P.R and M.L; formal analysis, R.C and AE.J; revision of analysis, E.C and D.O; clinical coordination, R.U and D.O, investigation, R.C, AE.J, M.I, N.G and M.A; writing – original draft preparation, R.C and A.J; writing – review and editing, R.C, AE.J, D.O, M.A and M.L; English revision, J.A and M.L, supervision, D.O; funding acquisition, D.O and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Do is a researcher funded by the Fond de Recherche du Québec (Santé) (322585).

Trial registration: N/A. This is a qualitative study.

Guarantor: David Ogez.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of our institution (protocol code #2022-2741, date of approval: 2021-09-17) for studies involving humans.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified.

ORCID iD

David Ogez https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7441-9678

References

- 1.Canadian-Pain-Task-Force . Working together to better understand, prevent, and manage chronic pain: what we heard. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada= Santé Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choinière M, Peng P, Gilron I, et al. Accessing care in multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities continues to be a challenge in Canada. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2020; 45: 943–948. DOI: 10.1136/rapm-2020-101935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth 2019; 123: e273–e283. DOI: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian-Pain-Task-Force . Chronic pain in Canada: laying a foundation for action. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langlois P, Perrochon A, David R, et al. Hypnosis to manage musculoskeletal and neuropathic chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2022; 135: 104591. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bicego A, Rousseaux F, Faymonville ME, et al. Neurophysiology of hypnosis in chronic pain: a review of recent literature. Am J Clin Hypn 2022; 64: 62–80. DOI: 10.1080/00029157.2020.1869517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKittrick ML, Connors EL, McKernan LC. Hypnosis for chronic neuropathic pain: a scoping review. Pain Med 2022; 23: 1015–1026. DOI: 10.1093/pm/pnab320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boldt I, Eriks-Hoogland I, Brinkhof MW, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for chronic pain in people with spinal cord injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 28(11): Cd009177, doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009177.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elkins G, Jensen MP, Patterson DR. Hypnotherapy for the management of chronic pain. IJCEH (Int J Clin Exp Hypn) 2007; 55: 275–287. DOI: 10.1080/00207140701338621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bicego A, Monseur J, Collinet A, et al. Complementary treatment comparison for chronic pain management: a randomized longitudinal study. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0256001. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen MP, McArthur KD, Barber J, et al. Satisfaction with, and the beneficial side effects of, hypnotic analgesia. IJCEH (Int J Clin Exp Hypn) 2006; 54: 432–447. DOI: 10.1080/00207140600856798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen MP, Mendoza ME, Ehde DM, et al. Effects of hypnosis, cognitive therapy, hypnotic cognitive therapy, and pain education in adults with chronic pain: a randomized clinical trial. Pain 2020; 161: 2284–2298. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winocur E, Gavish A, Emodi-Perlman A, et al. Hypnorelaxation as treatment for myofascial pain disorder: a comparative study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol 2002; 93: 429–434. DOI: 10.1067/moe.2002.122587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nesom G, Corbitt C, Andalia P, et al. Case series review of CBT-I outcomes: the relevance of medication use and morbidity. Sleep 2015; 1: A235–A236. Conference Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, et al. From ideas to efficacy: the ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol 2015; 34: 971–982. DOI: 10.1037/hea0000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caron-Trahan R, Jusseaux AE, Aubin M, et al. Definition and refinement of HYlaDO, a self-hypnosis training program for chronic pain management: a qualitative exploratory study. Explore 2023; 19: 417–425. DOI: 10.1016/j.explore.2022.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merckaert I, Lewis F, Delevallez F, et al. Improving anxiety regulation in patients with breast cancer at the beginning of the survivorship period: a randomized clinical trial comparing the benefits of single-component and multiple-component group interventions. Psycho Oncol 2017; 26: 1147–1154. DOI: 10.1002/pon.4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammond DC. Handbook of hypnotic suggestions and metaphors. New York, NY: WW Norton and Company, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogez D, Aubin M. Pratiquer l’autohypnose dans la gestion de la douleur chronique: Récit d’une patiente. Hypnose et thérapie brève 2022; 67. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bazeley P. Qualitative data analysis: Practical strategies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Agostino NM, Edelstein K. Psychosocial challenges and resource needs of young adult cancer survivors: implications for program development. J Psychosoc Oncol 2013; 31: 585–600. DOI: 10.1080/07347332.2013.835018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods 2006; 18: 59–82. DOI: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quantity 2018; 52: 1893–1907. DOI: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Analyse des données qualitatives. Paris: De Boeck Supérieur, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eason AD, Parris BA. Clinical applications of self-hypnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychol Conscious Theory, Res Pract 2019; 6: 262–278. DOI: 10.1037/cns0000173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: a psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Phys Ther 2014; 94: 1816–1825. DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20130597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finan PH, Garland EL. The role of positive affect in pain and its treatment. Clin J Pain 2015; 31: 177–187. DOI: 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen MP, Day MA, Miró J. Neuromodulatory treatments for chronic pain: efficacy and mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol 2014; 10: 167–178. DOI: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nijs J, D'Hondt E, Clarys P, et al. Lifestyle and chronic pain across the lifespan: an inconvenient truth? PM&R 2020; 12: 410–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tasso AF, Pérez NA, Moore M, et al. Hypnotic responsiveness and nonhypnotic suggestibility: disparate, similar, or the same? IJCEH (Int J Clin Exp Hypn) 2020; 68: 38–67. DOI: 10.1080/00207144.2020.1685330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen MP, Jamieson GA, Lutz A, et al. New directions in hypnosis research: strategies for advancing the cognitive and clinical neuroscience of hypnosis. Neurosci Conscious 2017; 3(1): nix004. DOI: 10.1093/nc/nix004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzales GR, Martinez AM, Goulart DM. Subjectivity within cultural-historical approach: theory, methodology and research. Berlin: Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar]