Abstract

Immunization of mice with Borrelia burgdorferi decorin binding protein A (DbpA), one of two gene products of the dbpBA locus, has been shown recently to confer protection against challenge. Hyperimmune DbpA antiserum killed a large number of B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates of diverse phylogeny and origin, suggesting conservation of the protective epitope(s). In order to evaluate the heterogeneity of DbpA and DbpB and to facilitate defining the conserved epitope(s) of these antigens, the sequences of the dbpA genes from 29 B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates and of the dbpB genes from 15 B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates were determined. The predicted DbpA sequences were fairly heterogeneous among the isolates (58.3 to 100% similarity), but DbpA sequences with the highest similarity tended to group into species previously defined by well-characterized chromosomal markers. In contrast, the predicted DbpB sequences were highly conserved (96.3 to 100% similarity). Substantial diversity in DbpA sequence was seen among isolates previously shown to be killed by antiserum against a single DbpA, suggesting that one or more conserved protective epitopes are composed of noncontiguous amino acids. The observation of individual dbpA alleles with sequence elements characteristic of more than one B. burgdorferi sensu lato species was consistent with a role for genetic recombination in the generation of dbpA diversity.

Spirochetes classified as Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (including B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii) are the causative agents of Lyme disease, the most commonly reported vector-borne infectious disease in the United States (50), and distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere. B. burgdorferi sensu lato is transmitted to human and animal hosts primarily by Ixodes sp. ticks. If diagnosed early, the disease can be effectively treated. However, if the infection is improperly diagnosed or treated, chronic or recurrent disease may result (49). Since diagnosis can be difficult, preventive measures in the form of a vaccine against the agent would be highly desirable, as would improved diagnostic tests.

Many B. burgdorferi proteins have been considered as candidate Lyme disease vaccines. Among these, outer surface protein A (OspA) has emerged as the most promising candidate (24, 31), showing efficacy when administered before syringe- or tick-borne challenge in several animal models (7, 15, 23). However, OspA is down regulated by the spirochete during transmission to the vertebrate host (10) and is, therefore, inaccessible or absent on most or all spirochetes during infection. Antibodies to OspA are capable of blocking transmission but are relatively ineffective against host-adapted spirochetes (2, 13).

Alternative vaccine candidates have been sought among the B. burgdorferi proteins that are immunogenic during natural or experimental infections and are therefore presumptively expressed in vivo. Antibodies to OspC, an in vivo-expressed protein (32), can protect gerbils or mice against homologous B. burgdorferi challenge (40, 42, 57); however, protection of mice against high-dose challenge with heterologous isolates has been unsuccessful to date (41). OspC is fairly heterogeneous in sequence (22, 53, 55), and predictions of at least 13 serogroups have been made with panels of OspC monoclonal antibodies (22). Additionally, OspC appears to be inaccessible to antibodies on some B. burgdorferi strains (4, 9).

B. burgdorferi binds specifically (19) to the collagen-associated proteoglycan decorin (8), an activity that may promote colonization of host tissues. A genetic locus encoding the candidate adhesins, decorin binding proteins A and B (DbpA and DbpB), has been cloned and sequenced elsewhere (18). In B. burgdorferi B31, the dbpBA locus is on the linear plasmid lp54, which also encodes ospAB (16). DbpA and DbpB are immunogenic and expressed in vivo, and DbpA is a target for antibody-mediated killing of B. burgdorferi during the early stages of infection (6, 20). Active immunizations with recombinant DbpA (rDbpA) also protected mice from homologous, and in some cases heterologous, borrelial challenge. Hyperimmune antiserum against a single rDbpA immunogen had bactericidal activity against many B. burgdorferi, B. afzelii, and B. garinii isolates, suggesting that a serological epitope(s) targeted by growth-inhibitory anti-DbpA antibodies is conserved throughout many diverse strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato (20). However, unlike DbpA antibodies, DbpB antibodies had only limited protective efficacy. To facilitate identification of the conserved serological epitope(s) of DbpA and to determine the extent of variability of the decorin binding proteins, we determined and analyzed the sequences of dbpA and dbpB genes from a diverse set of B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Borrelia isolates and cultivation.

The sources of the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, and group 25015 isolates used in this study are listed in Table 1. Borrelias were propagated in BSKII medium (1) as previously described (20).

TABLE 1.

Origins and accession numbers of dbpA and dbpB gene sequences that have been determined in this study

| Sp. and isolate | Origin

|

Sequence information

|

Source of isolate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biologicala | Geographic |

dbpA

|

dbpB

|

||||

| Amplification primers | Accession no. | Amplification primers | Accession no. | ||||

| B. burgdorferi sensu stricto | |||||||

| 297 | CSF | USAg (N.Y.) | 2 + 19, 8 + 13 | U75866b | 1 + 12 | U75867b | D. Dorward |

| B31 | Tick (I. scapularis) | USA (N.Y.) | 2 + 19, 9 + 13 | AF069269 | 1 + 12 | AF069266 | A. Barbour |

| Sh-2-82 | Tick (I. scapularis) | USA (N.Y.) | 2 + 19, 8 + 13 | AF069253 | 1 + 12 | AF069253 | A. Barbour |

| N40 | Tick (I. scapularis) | USA (N.Y.) | 2 + 19, 11 + 18a | AF069252 | 1 + 12 | AF069252 | S. Barthold |

| JD1 | Tick (I. scapularis) | USA (Mass.) | 2 + 19, 9 + 13 | AF069257 | 1 + 12 | AF069257 | D. Dorward |

| HB19 | Blood | USA | 2 + 19 | AF069254 | 1 + 12 | AF069254 | D. Dorward |

| 3028 | Human pus | USA (Tex.) | 2 + 17, 4 + 19, 2 + 19 | AF069286 | NDc | NAd | D. Dorward |

| G39/40 | Tick | USA (Conn.) | 2 + 19 | AF069256 | 1 + 12 | AF069256 | M. Höök |

| LP4 | Skin (EM) | USA (Conn.) | 2 + 19, 9 + 13 | AF069271 | 1 + 12 | AF069264 | M. Höök |

| LP5 | Skin (EM) | USA (Conn.) | ND | NA | 1 + 12 | AF069261 | D. Dorward |

| LP7 | Skin (EM) | USA (Conn.) | 2 + 19, 9 + 13 | AF069255 | 1 + 12 | AF069255 | M. Höök |

| NCH-1 | Skin | USA | 9 + 13, 2 + 19, 2 + 17, 5 + 19 | AF069285 | 1 + 12 | AF069259 | R. Johnson |

| ZS7 | Tick (I. ricinus) | Germany | 2 + 19 | AF069251 | 1 + 12 | AF069251 | R. Johnson |

| CA-2-87 | Tick (I. pacificus) | USA (Calif.) | ND | NA | 1 + 12 | AF069262 | D. Dorward |

| CA-3-87 | Tick (I. pacificus) | USA (Calif.) | 9 + 13, 2 + 19, 2 + 17, 5 + 19 | AF069276 | ND | NA | D. Dorward |

| FRED | Human | USA (Mo.) | ND | NA | 1 + 12 | AF069260 | D. Dorward |

| HBNC | Blood | USA (Calif.) | 9 + 13, 2 + 19, 2 + 17, 5 + 19 | AF069275 | ND | NA | D. Dorward |

| MC1 | Skin | USA (Wis.) | 9 + 13, 2 + 19, 2 + 17, 5 + 19 | AF079361 | ND | NA | R. Johnson |

| IPS | Tick (I. pacificus) | USA | ND | NA | 1 + 12 | AF069265 | R. Johnson |

| B. afzelii | |||||||

| PGau | Skin (ACA) | Germany | 2 + 19 | AF069270 | ND | NA | D. Dorward |

| ACA1 | Skin (ACA) | Sweden | 2 + 17, 10 + 19 | AF069278 | ND | NA | A. Barbour |

| M7 | Tick (I. persulcatus) | China | 2 + 17, 10 + 19 | AF069280 | ND | NA | R. Johnson |

| IPF | Tick (I. persulcatus) | Japan | 2 + 17, 10 + 19 | AF069274 | ND | NA | R. Johnson |

| BO23 | Skin | Germany | 2 + 19 | AF069267 | ND | NA | R. Johnson |

| VS461 | Tick (I. ricinus) | Switzerland | 2 + 17, 10 + 19 | AF069282 | ND | NA | R. Johnson |

| U01 | Skin | Sweden | 3 fluor,e 15a + 16a | AF069284 | ND | NA | D. Dorward |

| B. garinii | |||||||

| PBr | CSF | Germany | 2 + 17, 6 + 19, 7 + 14 | AF069281 | ND | NA | D. Dorward |

| Ip90 | Tick (I. persulcatus) | Russia | 9-12 frag DIG,f 15c + 18c | AF069258 | ND | NA | A. Barbour |

| 20047 | Tick (I. ricinus) | France | 2 + 17, 6 + 19 | AF029277 | 1 + 12 | AF069263 | R. Johnson |

| G25 | Tick (I. ricinus) | Sweden | 2 + 17, 10 + 19 | AF069279 | ND | NA | R. Johnson |

| VSBP | CSF | Switzerland | 2 + 17, 6 + 19 | AF069272 | ND | NA | R. Johnson |

| JEM4 | Skin | Japan | 2 + 17, 6 + 19 | AF079362 | ND | NA | R. Johnson |

| 153 | Tick (I. ricinus) | France | 3 fluor,e 15b + 16b | AF069283 | ND | NA | D. Dorward |

| Group 25015; 25015 | Tick (I. scapularis) | USA (N.Y.) | 2 + 17, 6 + 19, 10 + 19, 2 + 12, 15d + 18b | AF069273 | ND | NA | S. Barthold |

For B. burgdorferi sensu lato, original biological source was Ixodes sp. ticks (I. scapularis, Ixodes pacificus, Ixodes ricinus, or Ixodes persulcatus) or human Lyme disease clinical material (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF], erythema migrans [EM], and acrodermatitis chronicum atrophicans [ACA]).

B. burgdorferi 297 sequences from reference 18, confirmed in the present study.

ND, not determined.

NA, not applicable.

Oligonucleotide 3 used as fluorescein-labeled probe.

PCR fragment (frag) from primers 9 and 12 used as DIG-labeled probe.

USA, United States of America.

Genomic DNA preparation and molecular typing.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from various Borrelia isolates by standard methods (48) or with the Puregene (Gentra Systems, Inc., Research Triangle Park, N.C.) genomic DNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s directions. The rRNA rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer region was amplified from each isolate by PCR, and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis was then performed to confirm classification into the B. burgdorferi sensu lato groups according to the methods described by Postic et al. (39). PCR was performed by using Taq DNA polymerase and buffers (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.0], 2.5 mM MgCl2) from Perkin-Elmer Cetus (Foster City, Calif.) and 250 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, Ind.).

DNA blotting, hybridization, and detection.

A quantity (1.5 to 2.0 μg) of total genomic DNA was digested with 10 to 20 U of the appropriate restriction endonuclease as recommended by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). Digested DNA was separated by electrophoresis through an 0.8% agarose gel. Fragments were transferred to a Hybond-N membrane (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) with the Turboblot system (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and UV cross-linked to the membranes with the Stratalinker (Stratagene, North Torrey Pines, Calif.). The dbpAIp90 DNA fragment was labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) with the Genius kit (Boehringer Mannheim); other gene fragments and oligonucleotides were labeled with fluorescein with the ECL labeling kit (Amersham).

Blots to be probed with fluorescein-labeled fragments and/or oligonucleotides (used to identify and clone dbpA from B. garinii 153 and B. afzelii U01) were prehybridized and hybridized at 50°C in 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–5× Denhardt’s solution–1× ECL blocking solution–0.2 mg of heat-denatured herring sperm DNA per ml by standard protocols (48). After a 12- to 15-h hybridization with 10 to 20 ng of probe, the blots were washed as follows: two washes with 2× SSC–0.1% SDS for 2 min each at room temperature, a wash with 2× SSC–0.1% SDS for 2 min at 50°C, and then a wash with 0.5× SSC–0.1% SDS at 50°C. Bound probe was visualized on film (Kodak X-AR; ECL Hyperfilm) following development with the ECL detection kit.

For the DIG-labeled fragment (used to identify and clone dbpAIp90), prehybridization and hybridization were done in the same solution of 5× SSC–2% DIG blocking solution–0.1% Sarkosyl–0.02% SDS–50% formamide at 42°C. Probes were again used at a concentration of 10 to 20 ng/ml. Blots were then washed (two washes for 5 min each at room temperature with 2× SSC–0.1% SDS and then two washes for 15 min each at 65°C with 0.5× SSC–0.1% SDS) and visualized according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Genomic sublibrary construction and gene cloning.

In three cases, DNA fragments containing dbpA genes were identified and cloned from restriction enzyme digests of total genomic DNA by hybridization with dbpA probes. Primers 2 and 12 (Table 1 and Fig. 1), derived from dbpA297, were used to PCR amplify a 280-bp fragment from genomic DNA of B. garinii Ip90. Sequencing this fragment confirmed that it was a portion of the dbpAIp90 gene. This fragment was again PCR amplified, incorporating DIG-UTP label, and used to probe blots of digested Ip90 DNA. A 1.3-kb HindIII fragment hybridized to the probe. Fragments in a 1- to 3-kb range of genomic DNA cut with HindIII were excised from an agarose gel and extracted with Geneclean (BIO 101, Vista, Calif.). These fragments were ligated into pUC19 digested with the same enzyme and transformed into Subcloning Efficiency-Competent DH5α (BRL) cells. The dbpA genes of B. garinii 153 and B. afzelii U01 were identified with a fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotide (primer 3 [Table 2 and Fig. 1]) and BglII-digested genomic DNA with a similar approach. Colonies were lifted onto Nytran (Schleicher & Schuell) membranes, and single colonies containing the target gene were subsequently identified by hybridization with fluorescein- or DIG-labeled probes as described above. Plasmid DNA was prepared from the presumptive clones with the QIAprep plasmid miniprep kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.), and the Borrelia DNA inserts were sequenced to identify dbpA-containing clones.

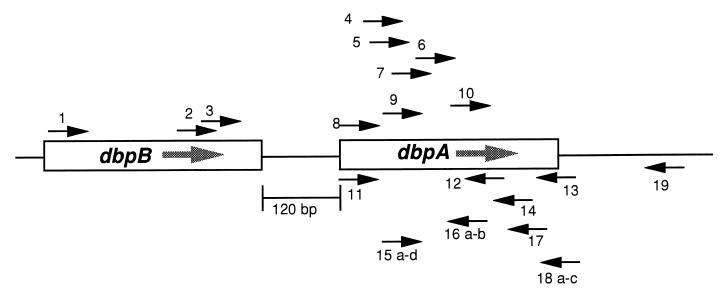

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of positional relationships among primers used for amplification of dbpA and dbpB genes. The annealing positions of the primers relative to the dbpBA locus of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolate 297 are indicated. These primers are described further in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide list

| No. | Name | Sequence | Derivation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WR6 | 5′-ATG AAA ATT GGA AAG CT-3′ | dbpB297 |

| 2 | 10F4 | 5′-GTG GTT AAG GAA AAA CAA AA-3′ | 3′ end of dbpB297 |

| 3 | WR38 | 5′-TTG TTA GCC TGT TAG TAG CAT GTG-3′ | dbpAIp90 |

| 4 | WR29 | 5′-GCA TGT AGT TTA ACA GGA A-3′ | Consensus of dbpBIp90-dbpB297 |

| 5 | WR24 | 5′-G(A/T)(C/T) TAA (C/A)AG GAG (C/A)AA CAA AA-3′ | dbpA297-dbpAN40-dbpAB023 |

| 6 | BM74 | 5′-GCC TGA ATT CAT ACT TAA AGC-3′ | Consensus of dbpAG25-dbpAJEM4-dbpAPBr- dbpAVSBP-dbpA20047 |

| 7 | WR2 | 5′-ATT CAT ACT TAA AGC AAA A-3′ | Consensus of dbpA297-dbpAPGau-dbpAIp90 |

| 8 | dbp 5′ | 5′-TTT CTA GAT TTT ATC TAA AAT ACA AAA AAA GG-3′ | dbpA297 |

| 9 | dbpΔ5′ | 5′-CCG GAT CCC GGA CTA ACA GGA GCA ACA AAA ATC-3′ | dbpA297 |

| 10 | BM73 | 5′-TAA AGA AAA TGG AGC GGG-3′ | Consensus of dbpAACA-1-dbpAIPF-dbpAM7- dbpAVS461 |

| 11 | N40 5′ | 5′-ATG AAT AAA TAT CAA AAA ACT-3′ | dbpAN40 |

| 12 | dbpREV | 5′-GCT TCC TCT TCT ATT GCT ATT A-3′ | dbpA297 |

| 13 | dbp 3′ | 5′-TTG TCT AAG CTT TTG AGT TGC ATA TAA AAA TGG-3′ | dbpA297 |

| 14 | WR4 | 5′-TCA GCT GTA GTT GGA GG-3′ | Consensus of dbpA297-dbpAPGau-dbpAIp90 |

| 15a | U01 5′ | 5′-TCT TGA GCT GAT GAT TCT A-3′ | dbpAU01 |

| 15b | 153 5′ | 5′-ACC GAT GAT TCT AGT CTA GC-3′ | dbpA153 |

| 15c | Ip90Δ5′B | 5′-CCG GAT CCC GGC TTA ACA GGA GAA-3′ | dbpAIp90 |

| 15d | 25015Δ5′ | 5′-CCG GAT CCC GGA TTA ACA GGA GAA ACA AA-3′ | dbpA25015 |

| 16a | U01 2.3′ | 5′-GAC AGG AAC AGT TAC ACA C-3′ | dbpAU01 |

| 16b | 153 2.3′ | 5′-ACA GTC ACA GAT GCA AAT G-3′ | dbpA153 |

| 17 | WR25 | 5′-CC(T/C/A) T(G/C/T)A GCT GTA GTT-3′ | dbpA297-dbpAIp90-dbpAN40-dbpA257-dbpAPGau-dbpAHB19-dbpAB023 |

| 18a | N40 3′ | 5′-GCA AGC TAA CAT TTA AAT-3′ | dbpAN40 |

| 18b | 25015 3′S | 5′-TGT CTA AGC TTA GTC GAC TTC TTT ATT TTT GCA TTT TTC-3′ | dbpA25015 |

| 18c | Ip90 3′H | 5′-TTG TCT AAG CTT GAT TTA AAC TAG GTA-3′ | dbpAIp90 |

| 19 | 5R1 | 5′-CCA AAT AAC ATC AAA AAG GA-3′ | 5′ to dbpA297 |

| 20 | 918 | 5′-GCG GAT AAC AAT TTC ACA CAG G-3′ | m13mp18 |

| 21 | 919 | 5′-GTT TTC CCA GTC ACG ACG-3′ | m13mp18 |

PCR amplification and DNA sequencing.

PCR fragments containing full-length or partial dbpA and dbpB genes were amplified with primer pairs described in Table 1 under standard PCR conditions: 96°C denaturing for 30 s, 52°C annealing for 30 s, and 72°C extension for 60 s. The annealing temperature was lowered to 45°C when fragments were amplified with degenerate oligonucleotides. The amplified fragments were purified from the PCR mix over a Qiaquick PCR purification column (Qiagen). The majority of dbpA and dbpB sequences were obtained by direct double-stranded cycle sequencing of the purified PCR product. The initial rounds of sequencing were with the primers used to generate these PCR products. In some instances, PCR-amplified fragments were cloned into the pCRII vector of the TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and subsequently sequenced with vector primers (primers 20 and 21 [Table 2]) and dbpA-specific primers. Gaps were bridged with genomic DNA as template and primers derived from the first round of sequencing. The complementary positions of the various primers used for PCR amplification are illustrated schematically in Fig. 1. Multiple independent sequence confirmation was available on both strands for most of the genes cloned by PCR. Sequencing in all cases was performed with the Dye Terminator Cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.). All sequencing reactions were run on the ABI Model 373A sequencer.

Sequence analysis.

The programs EDITSEQ of the Lasergene software package (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.) and DNA Strider (28) version 1.2 were used for routine analysis of DNA sequence information. Similarities and identities between pairwise comparisons of protein sequences were determined with the BestFit program of the Genetics Computer Group (GCG, Madison, Wis.) Wisconsin package version 8.0. Comparisons of multiple sequence alignments were done with the programs PileUp (GCG) and MEGALIGN (Lasergene). Relative similarity among the DbpA sequences by amino acid position was derived with the program PlotSimilarity (GCG) with a sliding window average of 10 residues. The Jameson-Wolf antigenic index of the DbpA297 sequence was determined with the program PROTEAN (Lasergene). Screening for multiple and direct repeats in the dbpBA locus and flanking genomic sequence was performed with DNA Strider version 1.2.

The phylogenetic relatedness among the DbpA sequences was estimated with the PHYLIP (12) analysis package, version 3.5c. A distance matrix was generated from the full-length amino acid sequences of the 30 DbpAs, and DbpB297, by the PHYLIP program PROTDIST with the Dayhoff percent accepted mutations matrix option. With the program NEIGHBOR (PHYLIP), phylogenetic trees were generated from the PROTDIST output by the distance matrix UPGMA (unweighted pair-group method using arithmetic averages) method. The sequence data was resampled into 100 replicate sets by the bootstrap analysis option of SEQBOOT (PHYLIP) to estimate the reproducibility of the tree branch nodes. A 50% majority rule consensus tree was constructed by the program CONSENSE (PHYLIP) and displayed by the program TreeView (36). The UPGMA method was also used to construct a phylogram from a subset of 23 DbpA sequences.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the dbpA and dbpB sequences determined in this study are listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

Sequencing of dbpA and dbpB genes.

In the current study, we have determined the nucleotide sequences of dbpA genes from 29 isolates, and of dbpB genes from 15 isolates, of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. A PCR-based approach, initially using primers derived from the original sequence of the dbpBA locus of isolate 297 (GenBank accession no. U75866 and U75867), was employed to amplify and sequence alleles of dbpA and dbpB from multiple B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates. In the case of dbpA, only a limited number of new genes could be amplified with the original primer sets, in contrast to similar methods used for amplification and sequencing of multiple alleles of the ospA (54) and ospC (22, 53) genes. Comparison of newly sequenced dbpA alleles allowed us to design additional primers from regions of conserved nucleotide sequences that permitted PCR amplification of new dbpA genes from additional B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates. These primers included two degenerate (up to 16-fold) oligonucleotides (numbers 5 and 17 [Table 2]) designed by selecting regions of the dbpA gene showing only moderate sequence conservation among multiple alleles. Attempts to PCR amplify dbpA alleles of B. garinii Ip90 and 153, B. afzelii U01, and six other strains with several combinations of primer pairs (Table 1 and Fig. 1) were unsuccessful. Sublibrary construction based on data obtained by Southern hybridization was used to obtain the sequence of the dbpA alleles of B. garinii Ip90 and 153 and B. afzelii U01. In contrast, a single specific oligonucleotide pair (primers 1 and 12 [Table 2 and Fig. 1]) was successfully used to amplify and sequence dbpB from 14 of 14 isolates of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. garinii 20047. Subsequent to determination of these sequences, the sequences of the dbpBA loci from B. burgdorferi B31 and N40 were deposited in GenBank (accession no. AE000790 and AF042746, respectively). There was complete agreement of our data with the sequences deposited by others.

Analysis and comparison of DbpA sequences.

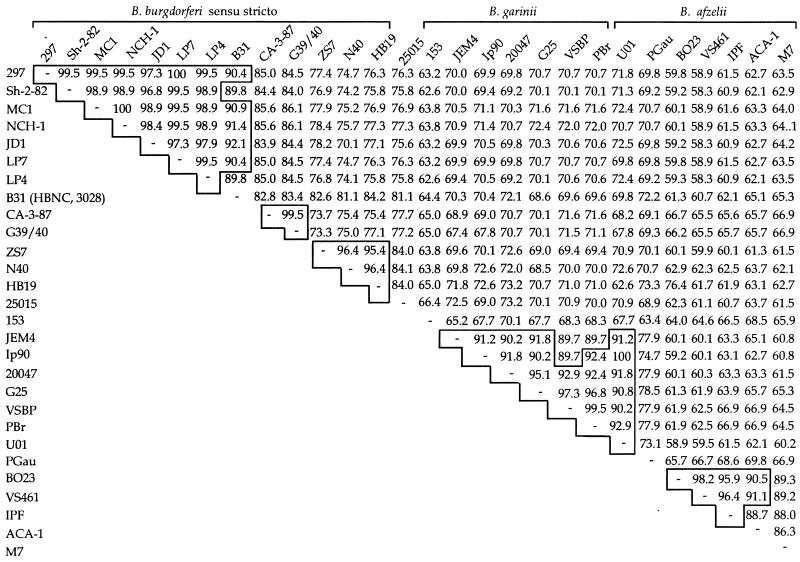

The similarity scores of all pairwise combinations of DbpA protein sequences were determined (Fig. 2). The interstrain heterogeneity of DbpA was high, with similarities ranging from 58.3 to 100%. As expected, the greatest similarity among DbpA allele sequences appeared within a given species (85 to 100%), but exceptions were noted. For example, DbpAs from isolates PGau (B. afzelii) and 153 (B. garinii) both differ from the other members of their respective species by >30%. At the present time, we do not know whether these highly divergent strains represent a minority of the alleles. DbpA from isolate 25015, the sole member of its phylogenetic group (5, 30, 39) that was sequenced, had 84% similarity with a subset of three B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolates (N40, HB19, and ZS7). Twenty-six of the 30 DbpA sequences had >90% similarity with at least one and in most cases several other DbpAs (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Amino acid similarities of DbpA sequences among B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates. Amino acid similarities, in percent, for deduced full-length DbpA sequences were calculated with BestFit. DbpAs of isolates B31, HBNC, and 3028 are 100% identical and were considered as a group for simplicity. For comparative purposes, isolates with >90% similarity are boxed.

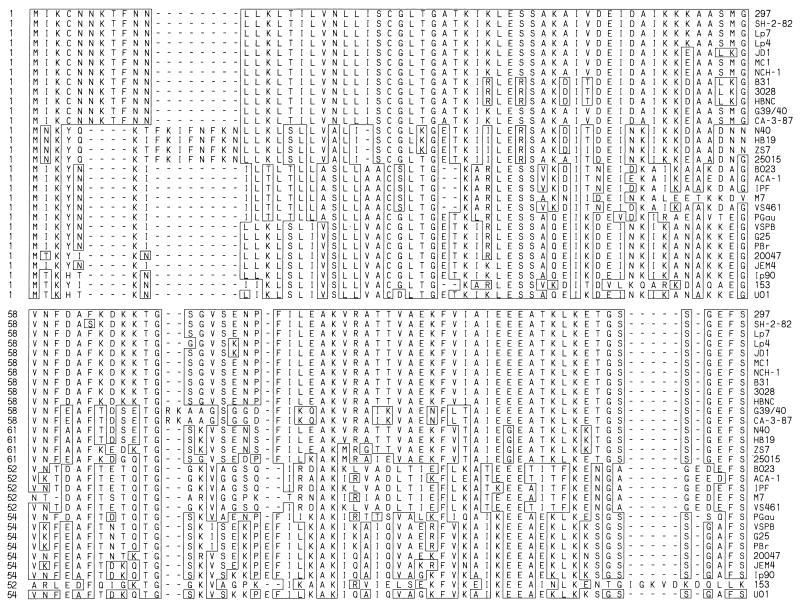

The derived DbpA amino acid sequences ranged in length from 169 to 195 residues. The shortest DbpA sequences were from B. afzelii. Multiple alignment of the 30 DbpA sequences (Fig. 3) revealed many well-conserved stretches of amino acids, as well as conserved putative insertions and deletions of one to eight residues, that were scattered throughout the length of the DbpAs. It was readily apparent that each of these features was conserved primarily within isolates from the same species. For example, six of seven B. afzelii isolates had an identical presumptive leader peptide 20 amino acids in length. All seven B. garinii isolates had a nearly identical leader peptide, again 20 amino acids long, but differing from the conserved B. afzelii sequence in five positions. Two different leader peptide sequences, of 24 and 27 amino acids, were seen among the 15 B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolates. Isolate 25015 has been placed in a separate phylogenetic group from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer (39) and genomic macrorestriction analysis (5, 30), yet its DbpA sequence was nearly identical to that of the B. burgdorferi N40-HB19-ZS7 group through the first 50 residues. While many blocks of amino acid sequence were fairly well conserved within the species groupings, only 23 positions in the mature protein following the amino-terminal cysteine had invariant residues in all 30 DbpA sequences. Also of note, the codon for Trp was absent from all 30 dbpA genes.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of DbpA. The sequences of DbpA from the 30 B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates were aligned with MEGALIGN. Residues identical with the reference DbpA297 are boxed.

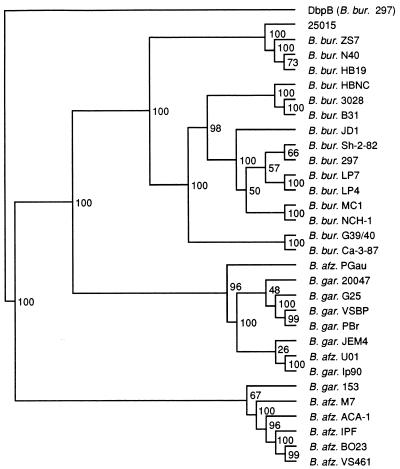

The DbpA multiple sequence alignment was analyzed by the distance matrix program, UPGMA, from the PHYLIP package to further investigate potential phylogenetic relationships among the various proteins. DbpB from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto 297 was included in this analysis as a potential sequence outlier. The inferred DbpA molecular phylogeny (Fig. 4) shows a major division between the group including most of the B. afzelii sequences and the rest of the DbpAs, with a further major division between the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. garinii sequences. With higher numerical representation, the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto branch was further divisible into smaller subgroups. Again, 25015 appeared to be most closely related to the N40-HB19-ZS7 group. B. garinii 153 was fairly distant from the other six representatives of this species, and B. afzelii PGau and U01 appeared more closely related to the B. garinii group than to the other members of their own species. All the DbpA sequences were more closely related to each other than to DbpB. Bootstrap analysis of the sequence data was performed to determine the number of times that a cluster of sequences would segregate to a particular node of the cladogram out of 100 resamplings of the data set. The nodes at all of the major branches of the DbpA cladogram had high bootstrap values, indicating that the overall topology of this phylogenetic tree was well supported.

FIG. 4.

Molecular tree showing phylogenetic relationships among the different DbpA sequences and comparison with DbpB. The rectangular cladogram was generated from comparisons of the 30 full-length DbpA sequences by PHYLIP. DbpB297 was included for comparative purposes. The numbers at the branch nodes indicate the results of bootstrap analysis. B. burgdorferi sensu lato species names were abbreviated as follows: B. burgdorferi, B. bur, B. afzelii, B. afz.; B. garinii, B. gar.

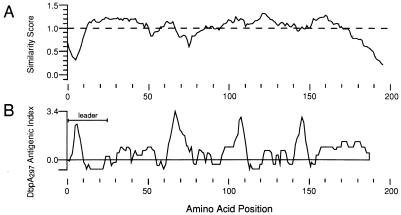

Visual inspection of the DbpA multiple sequence alignment indicated that most of the heterogeneity occurred near the carboxy terminus. This impression was confirmed by analysis of the alignment with the PlotSimilarity algorithm (Fig. 5A). Lower similarity scores were obtained in the regions of the molecule having the most postulated insertions and deletions, exemplified by the leader peptide, the region near residue 70, and the carboxy terminus. The heterogeneity among the dbpA genes at the 3′ end was consistent with the need to screen several potential PCR primers before successfully amplifying the desired dbpA product. In general, the predicted antigenic index along the length of the DbpA protein correlated with the regions of highest sequence heterogeneity (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Plot of the similarity score and antigenic index versus position number for the aligned DbpA sequences. The DbpA sequences were aligned with the program PileUp, and the relative identity score among the DbpAs was derived by the program PlotSimilarity with a sliding window average of 10 amino acids (A). The Jameson-Wolf antigenic index of the DbpA297 was determined with the program PROTEAN (B). The position numbering is relative to the first Met codon of the DbpA297 precursor protein; the position of the presumptive leader peptide region of this protein is indicated.

Analysis of DbpB sequences.

The similarity of the amino acid sequences of DbpB from 15 B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolates, and one B. garinii isolate, was very high, ranging from 96.3 to 100% (95.1 to 100% identity [data not shown]). We did not attempt to PCR amplify the dbpB genes from any additional isolates, but a partial sequence of dbpB was determined from the dbpBA locus cloned from B. garinii Ip90 by hybridization with a dbpA probe. The dbpB gene of Ip90 was divergent in sequence from the 16 PCR-amplified dbpB genes (data not shown), indicating that we have not yet determined the full extent of dbpB heterogeneity. Southern hybridization of genomic DNA from several different B. burgdorferi sensu lato species with a probe derived from dbpB297 gave further evidence of the interspecies heterogeneity of this gene (data not shown).

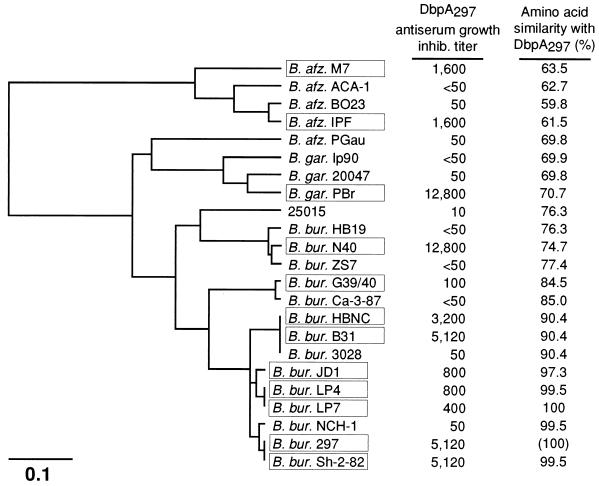

B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates killed by monovalent DbpA antiserum include those with divergent DbpA sequence phylogeny. We previously evaluated a panel of 35 B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates for their in vitro sensitivity to killing by rabbit hyperimmune serum against rDbpA derived from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto 297 (20). The sequence of DbpA has now been determined for 23 of the isolates evaluated in our earlier study. Among the 23 isolates that were sequenced, the 12 that were highly sensitive to killing by DbpA297 antiserum (inhibition endpoint titer of ≥100) were distributed among all major branches of the DbpA phylogram and were not restricted to those isolates with the highest DbpA297 sequence similarity (Fig. 6). Inspection of the alignment of these 12 sequences (data not shown) reveals that the longest run of contiguous amino acids identical among all isolates is three residues (TTA; DbpA297 residues 148 to 150). The TTA tripeptide and several conserved flanking residues are also found in isolates not killed by DbpA297 antiserum. As antibody binding sites on proteins are generally considered to be larger than three amino acids, it is likely that the epitope or epitopes targeted by the borreliacidal antibodies in the DbpA297 antiserum are composed of noncontiguous amino acids. Further, this putative epitope(s) appears to be conserved among DbpA proteins that are divergent in their primary structure.

FIG. 6.

DbpA sequence relatedness among isolates killed by DbpA297 antiserum. The molecular phylogram of the DbpA sequences that were determined for 23 of the isolates previously evaluated (20) for sensitivity to killing by DbpA297 antiserum was generated by the distance matrix program, UPGMA. Branch lengths are proportional to the relative mutational distance. The scale is in 0.1 nucleotide substitutions per site. The growth inhibition endpoint titer of the DbpA297 antiserum previously determined for each isolate (20) is indicated. A titer ≥ 100 is defined as positive inhibition; these isolates are indicated by boxes. The percent amino acid similarity of each DbpA with DbpA297 is shown for comparative purposes. Abbreviations used are as described for Fig. 4.

Evidence for recombination at the dbpBA locus.

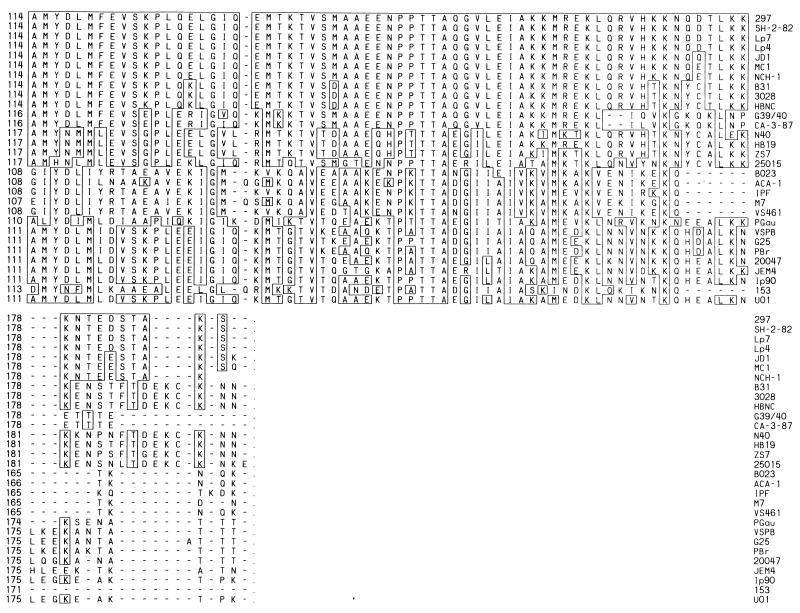

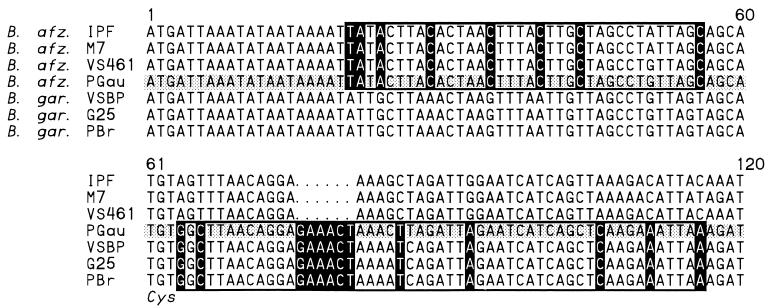

Examination of the alignment of DbpA sequences (Fig. 3) revealed the presence of stretches of amino acids that were conserved among most, but not all, alleles of a particular species. Combined with the phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 4), dbpA from B. afzelii PGau seemed to be a likely candidate for a gene resulting from recombination between alleles from different species. Alignment of the 5′ end of dbpAPGau with the dbpA genes from three other B. afzelii strains and three B. garinii strains gave further support for the possibility of lateral exchange of dbpA sequence between these species (Fig. 7). The dbpA gene in B. afzelii PGau is nearly identical to B. afzelii IPF, M7, and VS461 between nucleotides 1 and 57 encoding the putative leader peptide region, but the region just downstream of the Cys (nucleotides 63 to 120) shows greater similarity to the corresponding region of B. garinii VSBP, G25, and PBr. The dbpA gene from B. afzelii U01 has more stretches of nucleotides in common with B. garinii dbpA genes throughout its entire length, including the leader peptide (data not shown), and DbpAU01 has >90% overall similarity with six B. garinii DbpAs (Fig. 2). This data, in conjunction with the phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 4), suggests that the entire dbpA gene of B. afzelii U01 may have been acquired from a B. garinii isolate.

FIG. 7.

Alignment of the 5′ ends of selected dbpA genes reveals potential mosaic structure in dbpA from B. afzelii PGau. The sequence of the first 120 nucleotides of the coding region of dbpAPGau was aligned with the sequence of dbpA from three other B. afzelii isolates and with that of dbpA from three B. garinii isolates. The positions at which the dbpA genes are heterogeneous, and at which dbpAPGau is identical to the intraspecies consensus, are indicated by white letters on a black background. Regions of putative mosaic structure in dbpAPGau and their proposed species of origin are indicated by the open boxes. The position of the codon TGT for cysteine, at the amino terminus of the mature protein, is indicated for orientation purposes.

DISCUSSION

We have determined and analyzed the sequences of the dbpA genes from 29 isolates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato and of the dbpB genes from 15 isolates in order to evaluate the molecular heterogeneity of these genes and to complement serological analysis of their products. In our previous study, we found that, unlike OspC antisera (41, 42), hyperimmune antiserum against DbpA has in vitro borreliacidal activity and can passively protect mice against challenge (6, 20). This property facilitated our evaluation of the conservation of serological epitopes contributing to antibody-mediated spirochete killing and protection. The dbpA sequences of 23 of the 35 isolates evaluated in our earlier study for their vulnerability to rabbit antiserum against rDbpA from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto 297 have now been determined. We found that many isolates that were vulnerable to this serum had DbpA sequences that were highly divergent from DbpA297. DbpA of B. burgdorferi N40 has only 74.7% similarity (Table 2) and 66.7% identity (data not shown) with DbpA297, yet passively administered hyperimmune DbpA297 antiserum protected mice against challenge with B. burgdorferi N40 and had strong bactericidal activity against this isolate (20) (Fig. 6). B. afzelii M7 (63.5% DbpA similarity) and B. garinii PBr (70.7% DbpA similarity) were also killed by DbpA297 antiserum in vitro.

A few B. burgdorferi isolates were not killed by DbpA297 antiserum in vitro (e.g., 3028 and CA-3-87), yet their DbpA sequences were found to be highly similar to those of other isolates that were sensitive to DbpA297 antiserum (e.g., B31 and G39/40). It is possible that on these isolates other proteins expressed in vitro, such as the more abundant OspA and OspB, impede accessibility of DbpA to borreliacidal antibodies, as has been suggested for the P13 protein (47). In some cases (e.g., HB-19 and 25015), low levels of DbpA expression in vitro also contributed to resistance to killing by DbpA297 antiserum (20).

Comparison of the 12 DbpA sequences from B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates killed by DbpA297 antiserum did not reveal a good candidate for a conserved linear epitope target for these borreliacidal antibodies. For OspC, it has been suggested that protective antibodies bind to an as yet unidentified conformational epitope on this protein, as mice immunized with SDS-denatured OspC were not protected against B. burgdorferi challenge (17). The target(s) of bactericidal and protective DbpA antibodies may also be a conformational epitope(s) comprised of amino acids that are noncontiguous in the DbpA sequence.

The dbpA gene provides an additional example of a highly divergent, plasmid-encoded, B. burgdorferi lipoprotein gene. The extent of sequence heterogeneity of DbpA is found to be comparable to that observed among OspC sequences (22, 53, 55). However, we observed many groups of highly similar (>90%) DbpA sequences. Heterogeneity among OspA sequences has also been documented, but the extent of heterogeneity observed to date (25% divergence in identity [54]) seems to be less than that of OspC and DbpA. Comparison of DbpA sequences between pairs of isolates, in conjunction with similar comparisons among OspA and OspC sequences, showed that variation in each antigen can occur independently of the other. The OspA sequences of B. burgdorferi 297 (41) and N40 (14) are >99% similar, while DbpA is only 75% similar between these two strains (Fig. 2). Other pairs of B. burgdorferi strains also have similar OspA sequences but more divergent DbpA sequences. There is marked similarity between both the DbpA and OspA proteins of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto N40 isolated from an Ixodes scapularis (dammini) tick in New York and ZS7 isolated from an Ixodes ricinus tick in Germany (96 and 100%, respectively), but their OspC proteins are only 78% similar (43). The dbpA and ospA genes in these two geographically distant isolates have diverged little from their presumptive common ancestor, unlike their ospC genes.

In three studies (27, 43, 53), phylogenetic analysis of ospC sequences from large groups of B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates of diverse geographical origin showed that the ospC alleles did not strictly cluster into major monophyletic groups corresponding to their species of origin. Similarly, we found that the inferred phylogeny among DbpA sequences does not strictly correspond to B. burgdorferi sensu lato species (Fig. 4). The plasmid-encoded ospA gene seems to have a common evolutionary history with genes on the large chromosome in most B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates (11), however. Both ospC and dbpA appear to be evolving faster than, and possibly independently of, ospA and the genes on the large chromosome.

It is well recognized that most B. burgdorferi lipoproteins are heterogeneous in structure among different isolates, but the mechanisms for generating diversity among these antigens are, in most cases, only partially understood. The recently identified vmp-like sequence (vls) provides probably the best-characterized mechanism of antigenic variation in B. burgdorferi (56). The vls locus is comprised of 15 divergent tandemly arrayed silent vls pseudogenes and a single expressed gene, vlsE, near the telomere of the 28-kb linear plasmid lp28-1. Hypervariability in the VlsE lipoprotein is generated primarily by nonreciprocal recombination between the 17-bp direct repeats shared between vlsE and each of the pseudogenes, resulting in replacement of the central portion of vlsE with one of the vls pseudogenes. The mechanisms that generate diversity in other antigens are less well defined. Point mutations and deletions in the ospAB operon, apparently from nonreciprocal homologous recombination between ospA and ospB, have been observed during in vitro passage of B. burgdorferi (45, 46). Unlike the single-copy vlsE and ospAB loci, homologs of ospE and ospF genes are present on multiple plasmids (29, 51), and recombination among them may be facilitated by a conserved, repeated sequence element found upstream of, and in some cases flanking, these genes (29). Direct repeated sequence elements were not apparent within, or flanking, the dbpBA loci. Southern blot analysis (data not shown) and whole-genome sequencing (16) indicate that the dbpBA locus is present in a single copy. Thus, diversity of DbpA and B results in a manner different from that of VlsE and of OspE and OspF. Additionally, we have not observed in the dbpBA locus evidence of gene truncation and fusion as seen for ospAB (45). DbpA (Fig. 7) shares with OspC an apparent mosaic or chimeric structure (22, 27). This has been interpreted as evidence of lateral gene exchange between different B. burgdorferi sensu lato species in the case of ospC (22, 27), although an alternative hypothesis of parallel and convergent evolution has also been proposed (53). Evidence has been reported recently of simultaneous infections of vector ticks (25) and reservoir hosts (33) with multiple B. burgdorferi sensu lato species, suggesting that the opportunity exists for lateral gene exchange between different Borrelia species in the natural reservoir.

The sequence heterogeneity of DbpA among B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates may also reflect functional considerations. B. burgdorferi infects a broad range of vertebrate reservoir hosts in addition to mammals, including birds (34) and reptiles (26). It has recently been shown that chickens, unlike mammals, express two distinct isoforms of decorin containing either one or two dermatan sulfate chains (3). DbpA heterogeneity may reflect, at least in part, a need for B. burgdorferi to interact with different forms of decorin, or other related proteoglycans, in these reservoir hosts. There are presumably some structural constraints that limit the maximum extent of DbpA and DbpB heterogeneity while maintaining their adhesin activity. The PapG-PrsG pilus-associated proteins of uropathogenic Escherichia coli provide precedent for sequence heterogeneity within a family of adhesin proteins reflecting different specificities for related isoreceptors. Approximately 70% amino acid sequence similarity is found among the three variants of this adhesin family, each binding primarily to one of three related globoseries glycosphingolipids. These differences in receptor specificity appear to contribute to differences in tissue and host tropism for uropathogenic E. coli (52).

In contrast to DbpA, DbpB is very highly conserved within B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, with 15 different alleles showing >96% sequence similarity. This suggests that there may be higher selective pressure for variation in dbpA than in dbpB. For variable antigens such as OspA and OspC, it has been suggested that the heterogeneity in these proteins has resulted from immune selection in the natural reservoir (22, 53, 54). Such selective pressure may also exist for DbpA. The very high conservation of DbpB suggests that it is not under such selective pressure, consistent with the relative resistance of spirochetes to DbpB antibodies (20).

We have found evidence of decorin binding proteins in all species of B. burgdorferi sensu lato examined thus far, either by decorin affinity blotting (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, Borrelia japonica, Borrelia andersonii, and Borrelia valaisiana sp. nov. [20, 38]) or, as in this study, by PCR and Southern blotting (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, and group 25015). Borrelia hermsii, Borrelia turicatae, and Borrelia coriaceae are negative in the decorin affinity blot assay (38) and by Southern blotting with dbpA and dbpB probes (data not shown). Expression of decorin binding proteins may represent another biological difference between these other three Borrelia species, which are transmitted by the rapid-feeding soft-bodied Ornithodoros sp. ticks, and B. burgdorferi sensu lato species, which are transmitted by slow-feeding hard-bodied ticks, primarily Ixodes spp.

Although DbpA and DbpB are highly immunogenic during experimental infection (20), the sequence heterogeneity of these proteins may influence their utility in the serodiagnosis of human Lyme disease. In a preliminary study, Western blot assays with recombinant DbpA and DbpB detected immunoglobulin G antibodies specific for these proteins in the sera of many U.S. patients meeting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention case definition for early Lyme disease but not in sera from healthy volunteers residing in areas in which Lyme disease is nonendemic (37). Future work will examine the performance of DbpA and DbpB relative to other recombinant B. burgdorferi proteins that are under evaluation as serodiagnostic antigens (21, 35, 44).

We have demonstrated that the two tandem genes in the dbpBA locus differ substantially in their sequence heterogeneity, suggesting that they are under different selective pressure. These findings have raised interesting questions regarding potential differences in the interaction of the products of these two genes with the host immune system and with their proteoglycan receptors. The relatively few amino acids conserved among the DbpA sequences in all the B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates may be important for decorin binding activity. Despite the high-level sequence heterogeneity among dbpA genes, the finding that isolates with diverse dbpA sequences are in many cases vulnerable to the same DbpA antiserum suggests that antibody against a small number of DbpA alleles may protect against most isolates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. This adds support to the idea that DbpA may be a good candidate for inclusion in a second-generation vaccine for Lyme disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alan Barbour, Stephen Barthold, David Dorward, Claude Garon, and Russell Johnson for providing Borrelia isolates. We also thank Betty Guo and Magnus Höök for oligonucleotides 10f4 and 5r1 and for additional Borrelia isolates. We gratefully acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Nita K. Patel. We also thank Scott Koenig and Alice Erwin for critical review of the manuscript and Donni Leach for assistance in its preparation. We also acknowledge the National Cancer Institute for allocation of computing time and staff support at the Frederick Biomedical Supercomputing Center of the Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center.

This work was funded in part by NIH grant AI39865.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbour A G. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J Biol Med. 1984;57:521–525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barthold S W, Fikrig E, Bockenstedt L K, Persing D H. Circumvention of outer surface protein A immunity by host-adapted Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2255–2261. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2255-2261.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaschke U K, Hedbon E, Bruckner P. Distinct isoforms of chicken decorin contain either one or two dermatan sulfate chains. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30347–30353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bockenstedt L K, Hodzic E, Feng S, Bourrel K W, de Silva A, Montgomery R R, Fikrig E, Radolf J D, Barthold S W. Borrelia burgdorferi strain-specific Osp C-mediated immunity in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4661–4667. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4661-4667.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casjens S, Delange M, Levy III H L, Rosa P, Huang W M. Linear chromosomes of Lyme disease agent spirochetes: genetic diversity and conservation of gene order. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2769–2780. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2769-2780.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassatt D R, Patel N K, Hanson M S, Guo B P, Höök M. Protection of Borrelia burgdorferi infection by antibiotics to decorin-binding protein. In: Brown F, Burton D, Doherty P, Mekalanos J, Norby E, editors. Vaccines 97. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang Y F, Jacobson R H, Harpending P, Straubinger R, Patrican L A, Mohammed H, Summers B A. Recombinant OspA protects dogs against infection and disease caused by Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3543–3549. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3543-3549.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi H U, Johnson T L, Pal S, Tang L H, Rosenberg L, Neame P J. Characterization of the dermatan sulfate proteoglycans, DS-PGI and DS-PGII, from bovine articular cartilage and skin isolated by octyl-sepharose chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2876–2884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox D L, Akins D R, Bourell K W, Lahdenne P, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Limited surface exposure of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7973–7978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.deSilva A M, Telford III S R, Brunet L R, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi OspA is an arthropod-specific transmission-blocking Lyme disease vaccine. J Exp Med. 1996;183:271–275. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dykhuizen D E, Polin D S, Dunn J J, Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Dattwyler R, Luft B J. Borrelia burgdorferi is clonal: implications for taxonomy and vaccine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10163–10167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP-phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fikrig E, Barthold S W, Flavell R A. OspA vaccination of mice with established Borrelia burgdorferi infection alters disease but not infection. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2553–2557. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2553-2557.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fikrig E, Barthold S W, Kantor F S, Flavell R A. Protection of mice against the Lyme disease agent by immunizing with recombinant OspA. Science. 1990;250:553–556. doi: 10.1126/science.2237407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fikrig E, Telford III S R, Barthold S W, Kantor F S, Spielman A, Flavell R A. Elimination of Borrelia burgdorferi from vector ticks feeding on OspA-immunized mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5418–5421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser C M, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J-F, Fleischmann R D, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Gocayne J, Weidman J, Utterback T, Watthey L, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Garland S, Fujii C, Cotton M D, Horst K, Roberts K, Hatch B, Smith H O, Venter J C. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilmore R D J, Kappel K J, Dolan M C, Burkot T R, Johnson B J B. Outer surface protein C (OspC), but not P39, is a protective immunogen against a tick-transmitted Borrelia burgdorferi challenge: evidence for a conformational protective epitope in OspC. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2234–2239. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2234-2239.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo, B. P., E. L. Brown, D. W. Dorward, L. C. Rosenberg, and M. Höök. Mol. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Guo B P, Norris S J, Rosenberg L C, Höök M. Adherence of Borrelia burgdorferi to the proteoglycan decorin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3467–3472. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3467-3472.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson M S, Cassatt D, Guo B P, Patel N K, McCarthy M, Dorward D W, Höök M. Active and passive immunity against Borrelia burgdorferi decorin binding protein A (DbpA) protects against infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2143–2153. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2143-2153.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauser U, Wilske B. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays with recombinant internal flagellin fragments derived from different species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato for the serodiagnosis of Lyme neuroborreliosis. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1997;186:145–151. doi: 10.1007/s004300050057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jauris-Heipke S, Liegl G, Preac-Mursic V, Schwab E, Soutschek E, Will G, Wilske B. Molecular analysis of genes encoding outer surface protein C (OspC) of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: relationship to ospA genotype and evidence of lateral gene exchange of ospC. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1860–1866. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1860-1866.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson B J B, Sviat S L, Happ C M, Dunn J J, Frantz J C, Mayer L W, Piesman J. Incomplete protection of hamsters vaccinated with unlipidated OspA from Borrelia burgdorferi infection is associated with low levels of antibody to an epitope defined by mAb LA-2. Vaccine. 1995;13:1086–1094. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00035-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller D, Koster F T, Marks D H, Hosbach P, Erdile L F, Mays J P. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant outer surface protein A Lyme vaccine. JAMA. 1994;271:1764–1768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirstein F, Rijpkema S, Molkenboer M, Gray J S. Local variations in the distribution and prevalence of Borrrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genomospecies in Ixodes ricinus ticks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1102–1106. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1102-1106.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin M, Levine J F, Yang S, Howard P, Apperson C S. Reservoir competence of the southeastern five-linked skink (Eumeces inexpectatus) and the green anole (Anolis carolinensis) for Borrelia burgdorferi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:92–97. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livey I, Gibbs C P, Schuster R, Dorner F. Evidence for lateral transfer and recombination in OspC variation in Lyme disease Borrelia. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:257–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18020257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marck C. “DNA Strider”: a “C” program for the fast analysis of DNA and protein sequences on the Apple Macintosh family of computers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1829–1836. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.5.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marconi R T, Sung S Y, Norton Hughes C A, Carlyon J A. Molecular and evolutionary analyses of a variable series of genes in Borrelia burgdorferi that are related to ospE and ospF, constitute a gene family, and have a common upstream homology box. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5615–5626. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5615-5626.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathiesen D A, Oliver J H, Kolbert C P, Tullson E D, Johnson B J, Campbell G L, Mitchell P D, Reed K D, Telford III S R, Anderson J F, Lane R S, Persing D H. Genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:98–107. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meurice F, Parenti D, Fu D, Krause D S. Specific issues in the design and implementation of an efficacy trial for a Lyme disease vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:S71–S75. doi: 10.1086/516167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montgomery R R, Malawista S E, Feen K J M, Bockenstedt L K. Direct demonstration of antigenic substitution of Borrelia burgdorferi ex vivo: exploration of the paradox of the early immune response to outer surface proteins A and C in Lyme disease. J Exp Med. 1996;183:261–269. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakao M, Miyamoto K. Mixed infection of different Borrelia species among Apodemus speciosus mice in Hokkaido, Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:490–492. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.490-492.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olsen B, Jaenson T G T, Noppa L, Bunikis J, Bergstrom S. A Lyme borreliosis cycle in seabirds and Ixodes uriae ticks. Nature. 1993;362:340–342. doi: 10.1038/362340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padula S J, Dias F, Sampieri A, Craven R B, Ryan R W. Use of recombinant OspC from Borrelia burgdorferi for serodiagnosis of early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1733–1738. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1733-1738.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Page R D M. An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel, N. K., D. A. Couchenour, and M. S. Hanson. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 38.Patel, N. K., and M. S. Hanson. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 39.Postic D, Assous M V, Grimont P A, Baranton G. Diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato evidenced by restriction fragment length polymorphism of rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer amplicons. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:743–752. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preac-Mursic V, Wilske B, Patsouris E, Jauris S, Will G, Rainhardt S, Lehnert G, Klockmann U, Mehraein P. Active immunization with pC protein of Borrelia burgdorferi protects gerbils against B. burgdorferi infection. Infection. 1992;20:342–349. doi: 10.1007/BF01710681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Probert W S, Crawford M, Cadiz R B, LeFebvre R B. Immunization with outer surface protein (Osp) A, but not OspC, provides cross-protection of mice challenged with North American isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:400–405. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Probert W S, LeFebvre R B. Protection of C3H/HeN mice from challenge with Borrelia burgdorferi through active immunization with OspA, OspB, or OspC, but not with OspD or the 83-kilodalton antigen. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1920–1926. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1920-1926.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ras N M, Postic D, Foretz M, Baranton G. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, a bacterial species “Made in the U.S.A.”? Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1112–1117. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roessler D, Hauser U, Wilske B. Heterogeneity of BmpA (P39) among European isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and influence of interspecies variability on serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2752–2758. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2752-2758.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosa P A, Schwan T G, Hogan D. Recombination between genes encoding major outer surface proteins A and B of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3031–3040. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sadziene A, Rosa P, Thompson P A, Hogan D, Barbour A G. Antibody-resistant mutants of Borrelia burgdorferi: in vitro selection and characterization. J Exp Med. 1992;176:799–809. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.3.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sadziene A, Thomas D D, Barbour A G. Borrelia burgdorferi mutant lacking Osp: biological and immunological characterization. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1573–1580. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1573-1580.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steere A C. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:586–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908313210906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steere A C. Lyme disease: a growing threat to urban populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2378–2383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevenson B, Tilly K, Rosa P. A family of genes located on four separate 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi B31. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3508–3516. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3508-3516.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stromberg N, Marklund B I, Lund B, Ilver D, Hamers A, Gaastra W, Karlsson K A, Normark S. Host-specificity of uropathogenic Escherichia coli depends on differences in binding specificity to Gal alpha 1-4Gal-containing isoreceptors. EMBO J. 1990;9:2001–2010. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Theisen M, Borre M, Mathiesen M J, Mikkelsen B, Lebech A M, Hansen K. Evolution of the Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein OspC. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3036–3044. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3036-3044.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Will G, Jauris-Heipke S, Schwab E, Busch U, Robler D, Soutschek E, Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V. Sequence analysis of ospA genes shows homogeneity within Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto and Borrelia afzelii strains but reveals major subgroups within the Borrelia garinii species. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1995;184:73–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00221390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Jauris S, Hofmann A, Pradel I, Soutschek E, Schwab E, Will G, Wanner G. Immunological and molecular polymorphisms of OspC, an immunodominant major outer surface protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2182–2191. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2182-2191.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang J R, Hardham J M, Barbour A G, Norris S J. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of VMP-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhong W, Stehle T, Museteanu C, Seibers A, Gern L, Kramer M D, Wallich R, Simon M M. Therapeutic passive vaccination against chronic Lyme disease in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12533–12538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]