Abstract

BACKGROUND

Gestational diabetes mellitus is associated with increased risks of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. We hypothesized that high maternal glucose concentrations in early pregnancy are associated with adverse placental adaptations and subsequently altered uteroplacental hemodynamics during pregnancy, predisposing to an increased risk of gestational hypertensive disorders.

METHODS

In a population-based prospective cohort study from early pregnancy onwards, among 6,078 pregnant women, maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations were measured. Mid and late pregnancy uterine and umbilical artery resistance indices were assessed by Doppler ultrasound. Maternal blood pressure was measured in early, mid, and late pregnancy and the occurrence of gestational hypertensive disorders was assessed using hospital registries.

RESULTS

Maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations were not associated with mid or late pregnancy placental hemodynamic markers. A 1 mmol/l increase in maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations was associated with 0.71 mm Hg (95% confidence interval 0.22–1.22) and 0.48 mm Hg (95% confidence interval 0.10–0.86) higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure in early pregnancy, respectively, but not with blood pressure in later pregnancy. Also, maternal glucose concentrations were not associated with the risks of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

CONCLUSIONS

Maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations within the normal range are associated with blood pressure in early pregnancy, but do not seem to affect placental hemodynamics and the risks of gestational hypertensive disorders.

Keywords: blood pressure, cohort, Doppler, gestational hypertensive disorders, glucose, hypertension, placenta, pregnancy

Gestational diabetes complicates up to 17% of all pregnancies and is a strong risk factor for gestational hypertensive disorders.1,2 In pregnant women with pregestational diabetes, hyperglycemia causes a proinflammatory environment and cytokine derangements, which act on the endothelium, and lead to placental vascular changes, whereas insulin may have a direct toxic effect on the placenta.3,4 Also, pregnancies complicated by obesity or gestational diabetes show dysregulation of metabolic, vascular, and inflammatory pathways.5,6 This dysregulation is characterized by increased circulating concentrations of inflammatory molecules and placental overexpression of genes encoding for inflammatory mediators.5,6 Studies have shown that hyperglycemia during pregnancy is associated with reduced invasiveness of the trophoblast, increased oxidative stress in the maternal and fetal milieu, disrupted vasculogenesis, and macroscopically and histologically altered placentae.4,7–11 Treatment of gestational diabetes has been shown to reduce the prevalence of preeclampsia.12 It is not known yet to what extent early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations may influence early placental adaptations, blood pressure, and predispose women to gestational hypertensive disorders.

We hypothesized that high maternal glucose concentrations in early pregnancy are associated with adverse placental adaptations and subsequently altered uteroplacental hemodynamics during pregnancy, predisposing to an increased risk of gestational hypertensive disorders. We examined in a low-risk, multiethnic, population-based prospective cohort study among 6,078 pregnant women, the associations of maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations with placental flow measures, blood pressure throughout pregnancy, and gestational hypertensive disorders.

METHODS

Study design

This study was embedded in the Generation R Study, a population-based prospective cohort study from early pregnancy onwards in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. All pregnant woman and their children who were living within the city of Rotterdam at the time of birth were eligible to participate.13 The study has been approved by the local Medical Ethical Committee (MEC 198.782/2001/31). Written consent was obtained from all participating women. All pregnant women were enrolled between 2001 and 2005. Response rate at birth was 61%.14 In total, 8,879 women were enrolled during pregnancy. For the current study, 6,869 women were eligible as they enrolled before 18 weeks of gestational age and had singleton livebirths. Women with no data on maternal early-pregnancy glucose metabolism or with all outcome measures missing were excluded (n = 763). Women with pregestational diabetes (n = 21) and women with unreliable glucose concentrations (<1 mmol/l) were excluded (n = 7). The population for analysis comprised 6,078 pregnant women (Figure 1). All measurements in pregnancy were performed by trained research assistants who were part of the study team.

Figure 1.

Flowchart population for analysis.

Maternal glucose concentrations

Blood samples were collected once in early pregnancy at 13.2 median weeks’ gestation (95% range 9.6;17.6), as described previously.15 After 30 minutes of fasting, venous blood samples were collected from pregnant women, by specifically trained research nurses who were part of the research team, and temporally stored at room temperature for a maximum of 3 hours. We considered the 30 minutes fasting samples non-fasting samples. This time interval was chosen because of the design of our study, in which it was not possible to obtain fasting samples from all pregnant women. At least every 3 hours, blood samples were transported to a dedicated laboratory facility (Star-MDC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands), for further processing and storage.16 Glucose (mmol/l) is an enzymatic quantity and was measured with the c702 module on a Cobas 8000 analyzer (Roche, Almere, The Netherlands). Insulin (pmol/l) was measured with electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on a Cobas e411 analyzer (Roche, Almere, The Netherlands). Quality control samples demonstrated intra- and interassay coefficients of variation of 1.30% and 2.50%, respectively. Information on pregestational diabetes mellitus was obtained from self-reported questionnaires and on gestational diabetes from medical records after delivery. Gestational diabetes was diagnosed by a community midwife or an obstetrician according to Dutch midwifery and obstetric guidelines using the following criteria: either a random glucose concentrations >11.0 mmol/l, a fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l, or a fasting glucose between 6.1 and 6.9 mmol/l with a subsequent abnormal glucose tolerance test.17

Placenta hemodynamic characteristics

Ultrasound examinations were carried out in 2 dedicated research centers in the city of Rotterdam in early (median 13.2 weeks gestational age, interquartile range (IQR) 12.2;14.9), mid (median 20.4 weeks gestational age, IQR 19.9;21.1), and late pregnancy (median 30.2 weeks gestational age, IQR 29.9;30.6). We established gestational age by using data from the first ultrasound examination.18 Uterine artery resistance index and umbilical artery pulsatility index were derived from flow velocity waveforms in mid and late pregnancy. Standard deviation scores for uterine artery resistance index and umbilical artery pulsatility index were based on values from the whole study population and represent the equivalent of z-scores. Late pregnancy uterine artery notching was diagnosed if a notch was present uni- or bilaterally, as a result from increased blood flow resistance, which is a sign of placental insufficiency.19

Blood pressure and gestational hypertensive disorders

Blood pressure was measured at each pregnancy visit (median gestational age 13.2 weeks (IQR 12.2;14.9); 20.4 weeks (IQR 19.9;21.1); and 30.2 weeks (IQR 29.9;30.6)) using an Omron 907 automated digital oscillometer sphygmomanometer (OMRON Healthcare Europe, Hoofddorp, The Netherlands).20 The mean value of 2 blood pressure readings over a 60-second interval was documented for each participant.21

Information about hypertensive disorders in pregnancy was obtained from medical records.14 The occurrence of hypertension and related complications were cross-validated using hospital registries, and defined using criteria of the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy.22,23 Gestational hypertension was defined as de novo hypertension alone (an absolute blood pressure 140/90 mm Hg or greater), appearing after 20 weeks gestational age. Preeclampsia was defined as de novo hypertension (blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg) after the 20th gestational week with concurrent proteinuria (0.3 g or greater in a 24-hour urine specimen or 2+ or greater (1 g/l) on a voided specimen or 1+ or greater (0.3 g/l) on a catheterized specimen). Any gestational hypertensive disorder was defined as either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

Covariates

Maternal height (cm) and weight (kg) were measured without shoes and heavy clothing at enrollment and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated. Information about prepregnancy weight, ethnicity (European/non-European), and education (higher education yes/no) was obtained by questionnaire.14 Folic acid supplementation, categorized as use vs. no use, and parity, categorized as nulliparous or multiparous, were obtained at enrollment by questionnaire.24 Information about smoking was available from questionnaires, and was classified as “yes” if the woman smoked until pregnancy was known and if she continued to smoke throughout pregnancy.25

Statistical analyses

First, we conducted a nonresponse analysis to compare characteristics of women with and without glucose measurements available. Second, we assessed the associations of maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations continuously with mid and late pregnancy uterine artery and umbilical artery resistance indices and late pregnancy uterine artery notching, and with blood pressure in early, mid, and late pregnancy, using linear and logistic regression models. We also analyzed the longitudinal systolic and diastolic blood pressure patterns in women using unbalanced repeated measurement regression models.26 These models take the correlation between repeated measurements of the same subject into account, and allow for incomplete outcome data. Using fractional polynomials of gestational age, the best-fitting models were constructed. For presentation purposes, we constructed tertiles of maternal glucose concentrations for these analyses. Third, we assessed the associations of maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations continuously with gestational hypertensive disorders (gestational hypertension and preeclampsia), using logistic regression models. For all analyses, we constructed different models to explore whether any association was explained by maternal sociodemographic and lifestyle factors. The basic model was adjusted for gestational age at glucose measurement; the main model was additionally adjusted for gestational age at assessment, maternal ethnicity, age, parity, educational level, smoking, and folic acid supplement use; and the maternal BMI model was additionally adjusted for maternal prepregnancy BMI. Included covariates were based on previous studies, strong correlations with exposure and outcomes, and changes in effect estimates of >10%. We further tested but did not observe statistical interactions between maternal prepregnancy BMI and maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations for the associations with uterine and umbilical artery resistance indices and blood pressure. Statistical interaction terms were tested by including the term maternal prepregnancy BMI × maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations in the regression model. We performed 3 sensitivity analyses. First, analyses were repeated using maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting insulin concentrations. Second, to test whether the associations of maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations with high blood pressure we excluded women with gestational diabetes (n = 66). Third, to test whether a cutoff effect was present, we tested for differences in associations with blood pressure between women in quintiles of glucose concentrations, with the lowest quintile used as the reference group. We used multiple imputation for missing values of covariates according to Markov Chain Monte Carlo method.27 The percentage of missing data was <10%, except for smoking (15%) and folic acid supplement use (31.2%). Five imputed datasets were created and pooled for analyses. No significant differences in descriptive statistics were found between the original and imputed datasets. The repeated measurement analysis was performed using the Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), including the Proc Mixed module for unbalanced repeated measurements. All other analyses were performed using the Statistical Package of Social Sciences version 24.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Population characteristics

Population characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations were 4.4 mmol/l. In total, 64 (1.1%) women were diagnosed with gestational diabetes. Late pregnancy uterine artery notching occurred in 312 (10.2%) participants. Gestational hypertension developed in 203 (3.8%) women and preeclampsia developed in 131 (2.4%) women. Nonresponse analyses showed that women without glucose measurements were more often parous, had a lower level of educational attainment, used folic acid supplementation more often, were more often of non-European descent, and had a higher mid pregnancy and a lower late pregnancy uterine artery resistance index (Supplementary Table S1 online). Histogram for maternal glucose concentrations given in Supplementary Figure S1 online.

Table 1.

Characteristics of mothers (n = 6,078)

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 29.8 (5.1) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 167.5 (7.4) |

| Weight before pregnancy, mean (SD), kg | 66.4 (12.7) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 22.6 (20.7–25.4) |

| Parity, no. nulliparous (%) | 3,458 (57.4) |

| Education, no. higher education (%) | 2,538 (44.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Dutch or European, no. (%) | 3,558 (61.0) |

| Surinamese, no. (%) | 503 (8.6) |

| Turkish, no. (%) | 472 (8.1) |

| Moroccan, no. (%) | 352 (6.0) |

| Cape Verdian or Dutch Antilles, no. (%) | 410 (7.1) |

| Smoking | |

| None, no. (%) | 3,712 (72.2) |

| Early-pregnancy only, no. (%) | 452 (8.8) |

| Continued, no. (%) | 974 (19.0) |

| Folic acid use, no. used (%) | 2,943 (47.4) |

| Pregestational diabetes mellitus, no. (%) | 0 (0) |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | |

| Early pregnancy | 115 (12.3)/68 (9.6) |

| Mid pregnancy | 116 (12.0)/67 (9.4) |

| Late pregnancy | 118 (12.0)/69 (9.4) |

| Mid pregnancy uterine artery resistance index, mean (SD) | 0.54 (0.09) |

| Late pregnancy uterine artery resistance index, mean (SD) | 0.49 (0.08) |

| Late pregnancy uterine artery notching, no. (%) | 312 (10.2) |

| Glucose, mean (SD), mmol/l | 4.4 (0.84) |

| Insulin, median (IQR), pmol/l | 115.1 (55.4–233.4) |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus, no. (%) | 64 (1.1) |

| Gestational hypertension, no. (%) | 203 (3.8) |

| Preeclampsia, no. (%) | 131 (2.4) |

| Birth characteristics | |

| Males, no. (%) | 3,076 (50.6) |

| Gestational age at delivery, median (IQR), weeks | 40.1 (39.1–41.0) |

| Preterm birth, no. (%) | 310 (5.1) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 3,417 (564) |

| Placenta weight, median (IQR), g | 610 (530–720) |

Values are observed data and represent means (SD), medians (IQR), or number of subjects (valid %). Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Early-pregnancy glucose concentrations and placental hemodynamics

Maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations were not associated with mid and late pregnancy uterine artery resistance indices, umbilical artery pulsatility indices, and risk of late pregnancy uterine artery notching (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations with mid and late pregnancy placental flow measures (n = 4,236)

| Maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations, mmol/l | Uterine artery | Umbilical artery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance index (95% confidence interval) | Notching (95% confidence interval) | Pulsatility index (95% confidence interval) | |

| Mid pregnancy | |||

| Basic model | −0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) | Not available | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.07) |

| Main model | −0.00 (−0.05 to 0.04) | Not available | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.07) |

| BMI model | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) | Not available | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.06) |

| Late pregnancy | |||

| Basic model | −0.00 (−0.03 to 0.02) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.09) | −0.02 (−0.06 to 0.01) |

| Main model | −0.00 (−0.05 to 0.04) | 0.95 (0.82 to 1.09) | −0.02 (−0.06 to 0.02) |

| BMI model | −0.03 (−0.08 to 0.02) | 0.92 (0.79 to 1.08) | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.02) |

Values are SDSs (95% CI) from linear regression models, reflecting differences in measures of uterine and umbilical artery flow measures, and OR (95% CI) reflecting difference in risk of late pregnancy uterine artery notching, per 1 mmol/l increase in maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations. Estimates are from multiple imputed data. Basic model: adjusted for gestational age at glucose measurement. Main model: gestational age at glucose measurement, gestational age at ultrasound, maternal ethnicity, age, parity, educational level, smoking, and folic acid supplement use. BMI model: main model additionally adjusted for maternal prepregnancy BMI. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SDSs, standard deviation scores.

Early-pregnancy glucose concentrations, blood pressure, and gestational hypertensive disorders

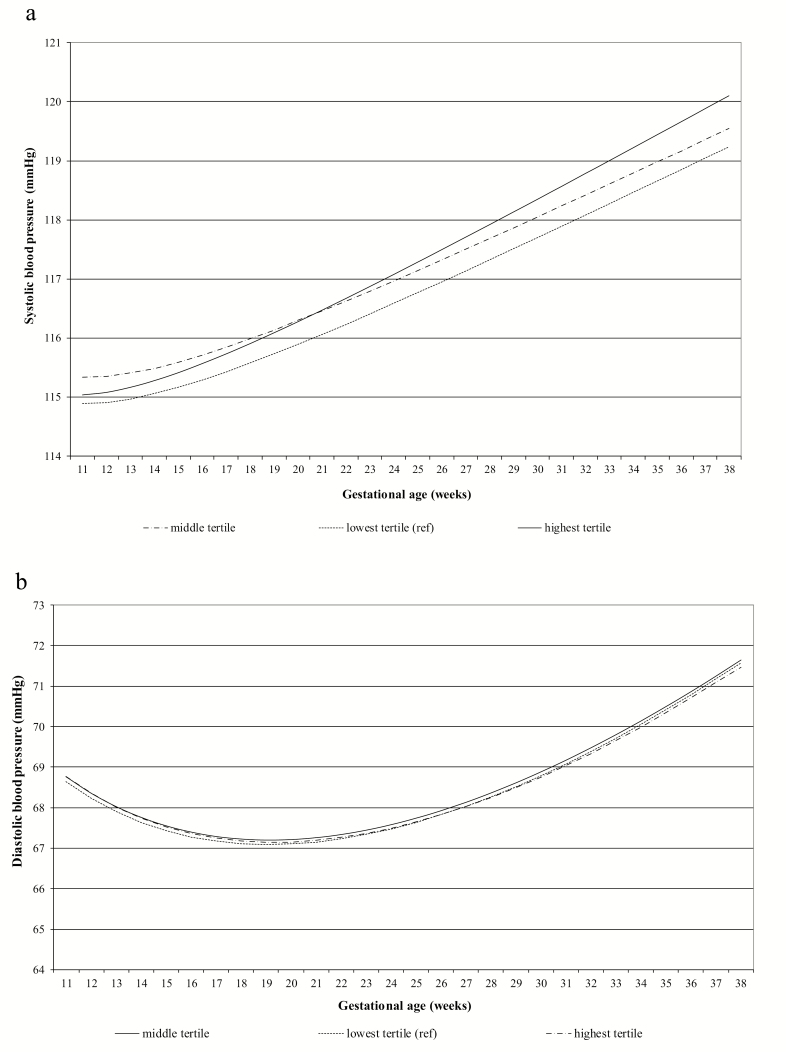

Associations of maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations with blood pressure in early, mid, and late pregnancy are shown in Table 3. A 1 mmol/l increase in maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations was associated with 0.71 mm Hg (95% confidence interval 0.22;1.22) and 0.48 mm Hg (95% confidence interval 0.10;0.86) higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure in early pregnancy, respectively, but not with blood pressure in later pregnancy. Using repeated measurements analysis (Figure 2), we observed that tertiles of maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations were not associated with blood pressure over time (P value for interaction of early-pregnancy glucose concentrations with gestational age >0.05, Supplementary Table S5 online). Also, maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations were not associated with the risks of gestational hypertensive disorders (Table 4).

Table 3.

Associations of maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations with early, mid, and late pregnancy blood pressure (n = 5,265)

| Maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations, mmol/l | Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg (95% confidence interval) | Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Early pregnancy | ||

| Basic model | 0.37 (−0.08 to 0.81) | 0.40 (0.06 to 0.75)* |

| Main model | 0.47 (0.03 to 0.92)* | 0.40 (0.06 to 0.75)* |

| BMI model | 0.71 (0.22 to 1.22)* | 0.48 (0.10 to 0.86)* |

| Mid pregnancy | ||

| Basic model | 0.13 (−0.30 to 0.48) | −0.13 (−0.44 to 0.18) |

| Main model | 0.19 (−0.21 to 0.59) | −0.12 (−0.43 to 0.20) |

| BMI model | 0.36 (−0.09 to 0.80) | −0.02 (−0.37 to 0.33) |

| Late pregnancy | ||

| Basic model | 0.21 (−0.18 to 0.61) | 0.19 (−0.12 to 0.50) |

| Main model | 0.25 (−0.15 to 0.65) | 0.18 (−0.13 to 0.49) |

| BMI model | 0.36 (−0.08 to 0.80) | 0.24 (−0.10 to 0.59) |

Values are mm Hg (95% CI) from linear regression models, reflecting differences in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, per 1 mmol/l increase in maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations. Estimates are from multiple imputed data. Basic model: adjusted for gestational age at glucose measurement. Main model: gestational age at glucose measurement, gestational age at blood pressure measurement, maternal ethnicity, age, parity, educational concentrations, smoking, and folic acid supplement use. BMI model: main model additionally adjusted for maternal prepregnancy BMI. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval.

*P value < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal associations between tertiles of early-pregnancy glucose concentrations and blood pressure (n = 6,078). Blood pressure patterns in different maternal early-pregnancy glucose tertiles. (a) Systolic and (b) diastolic blood pressure in different maternal early-pregnancy glucose tertiles (n = 6,078). Results reflect the change in mm Hg in mothers with early-pregnancy glucose concentrations in the second (4.0–4.6 mmol/l) and third (4.6–10.3 mmol/l) tertiles, compared with those with glucose levels in the first tertile (0.3–4.0 mmol/l). (a) Systolic blood pressure = β0 + β1 × glucose tertile + β2 × gestational age + β3 × gestational age−2 + β4 × glucose tertile × gestational age. (b) Diastolic blood pressure = β0 + β1 × glucose tertile + β2 × gestational age + β3 × gestational age0.5 + β4 × glucose tertile × gestational age. The models were adjusted for gestational age at intake. The interaction term of maternal early-pregnancy glucose tertile with gestational age in weeks was not significant. Similarly, when glucose was used continuously in the models, no significant interaction of maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentration with gestational age in weeks was observed. Estimates are given in Supplementary Table S5 online.

Table 4.

Associations of maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations with the risks of gestational hypertensive disorders (n = 5,459)

| Maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations, mmol/l | Gestational hypertension (95% confidence interval), n = 203 | Preeclampsia (95% confidence interval), n = 131 | Any gestational hypertensive disorder (95% confidence interval), n = 334 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic model | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.20) | 0.98 (0.81 to 1.17) | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.09) |

| Main model | 1.02 (0.86 to 1.20) | 0.87 (0.70 to 1.09) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.10) |

| BMI model | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.18) | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.11) | 0.94 (0.81 to 1.09) |

Values are ORs (95% CI) from logistic regression models, reflecting differences in risk of gestational hypertensive disorders, per 1 mmol/l increase in maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations. Estimates are from multiple imputed data. Basic model: adjusted for gestational age at glucose measurement. Main model: gestational age at glucose measurement, maternal ethnicity, age, parity, educational level, smoking, and folic acid supplement use. BMI model: main model additionally adjusted for maternal prepregnancy BMI. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; ORs, odds ratios.

Sensitivity analyses

In mid pregnancy, higher insulin concentrations were associated with a higher umbilical artery pulsatility index in the basic and main model, but the association attenuated in the BMI model (Supplementary Table S2 online). In the BMI model, higher early-pregnancy insulin concentrations were associated with a higher early-pregnancy systolic blood pressure (Supplementary Table S3 online). We found similar results to the main findings when we excluded women with gestational diabetes (data not shown). Finally, no differences in associations with blood pressure between women with non-fasting glucose concentrations in quintiles were observed (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that higher maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations are associated with higher blood pressure in early pregnancy, but no associations were present with blood pressure in mid or late pregnancy. Also, maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations were not associated with placental hemodynamics or gestational hypertensive disorders.

Meaning of the current study and findings

Hyperglycemia during pregnancy is associated with miscarriage, fetal structural anomalies, fetal macrosomia, fetal demise, preterm birth, and gestational hypertensive disorders.28,29 Limited evidence for early-pregnancy screening for diabetes in the general population exist, although testing can be performed as early as the first prenatal visit if a high degree of suspicion of undiagnosed type 2 diabetes exists.28 Current clinical guidelines advise screening for pregestational diabetes among women with overweight and additional risk factors.28,30 In clinical practice, the diagnosis of gestational diabetes is usually made in second half of pregnancy. However, high glucose concentrations may already have contributed to risk of gestational hypertensive disorders and other adverse effects on maternal and fetal health before gestational diabetes and associated complications such as fetal macrosomia and polyhydramnios become apparent.29 Optimization of glucose regulation in the case of gestational diabetes and pregestational diabetes leads to a strong reduction of risk of gestational hypertensive disorders.31 Therefore, early pregnancy may be a critical period for adverse effects of increased glucose concentrations on fetal and maternal pregnancy outcomes. Previously we reported associations of higher maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations with decreased fetal growth rates in mid pregnancy and increased fetal growth rates from late pregnancy onwards, and an increased risk of delivering a large-for-gestational-age infant.15 Early placenta development may play an important role in these associations. Next to its adverse effects on fetal growth, inadequate placental development may play an important role in the development of gestational hypertensive disorders.

Early pregnancy is a critical period for optimal placenta development. In this period, trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling takes place to ensure adequate blood flow to the placenta, leading to larger vessels with lower resistance and increased end-diastolic flow.32 Normally, in early pregnancy, cardiac output increases, peripheral vascular resistance is reduced, and blood pressure decreases until mid pregnancy, returning to baseline at term.32 If these processes are inadequate, increased blood pressure, abnormal uterine artery Dopplers with higher resistance indices and notching may be observed, and gestational hypertension or preeclampsia may develop. Previous studies have shown that women with prediabetes defined as HbA1c of 5.7–6.4% in early pregnancy represent a high-risk group for development of gestational hypertensive disorders.33,34 It is unclear how early-pregnancy glucose concentrations across the full range influence placental flow measures, blood pressure, and gestational hypertensive disorders. We hypothesized that higher early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations negatively influence placental flow measures, blood pressure, and risk of gestational hypertensive disorders.

Previous studies report associations of glucose concentrations with placental flow measures.35,36 In a study among 231 pregnant women with polycystic ovarian syndrome, early pregnancy and, more strongly, mid pregnancy fasting glucose concentrations, were positively associated with an increased mid-pregnancy uterine artery pulsatility index.35 A retrospective study among 155 pregestational diabetic women suggested a positive correlation between concentrations of HbA1c and increased vascular resistance in the uterine and umbilical arteries, suggesting that hyperglycemia may influence uterine and placental vessel endothelial function.36 In the current study in a low-risk healthy population, we did not observe associations of maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations with placental flow measures. The difference in results may be explained by our low-risk, nondiabetic population. Also, glucose concentrations in early pregnancy may not influence placental flow measures measured later in pregnancy.

Diabetes and hypertension often occur simultaneously and show a substantial overlap in disease etiology and risk factors, such as genetics, obesity, insulin resistance, and inflammation.37–39 Due to prolonged exposure to effects of hyperglycemia, we expected to find stronger associations of early-pregnancy glucose concentrations with blood pressure throughout pregnancy. In the current study, we observed associations of maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations with early-pregnancy blood pressure, but not later in pregnancy. Possibly, this may be due to the fact that the time between the exposure and the outcome is large, and as the effect estimates are already small and within the normal range in early pregnancy, the effect of early-pregnancy glucose concentrations on blood pressure in mid or late pregnancy may not be detectable, or no association may present at all. Possibly, a more pronounced effect on cardiovascular outcomes may be observed in the presence of sustained elevated glucose concentrations. It has been shown that gestational diabetes leads to a strongly increased risk of gestational hypertensive disorders.1,2 Simultaneously, associations with gestational hypertensive disorders have not been found in women diagnosed with prediabetes in early pregnancy although these women are at increased risk of development of gestational diabetes.34,40 A previous prospective study among 4,589 healthy nulliparous women showed that even within the normal range, the plasma glucose level 1 hour after 50-g oral glucose challenge was positively correlated with the likelihood of preeclampsia.41 As parity is a strong risk factor for preeclampsia, the baseline risk of gestational hypertensive disorders among this nulliparous population may be higher. In the current study, we did not find associations of early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations with risk of preeclampsia. This difference might be explained by differences in baseline risk and in glucose measurements. Future studies, using early-pregnancy fasting glucose concentrations or glucose concentrations obtained after a standardized oral glucose challenge, are needed to confirm if early-pregnancy glucose concentrations are indeed associated with preeclampsia in a low-risk population. We did not observe associations of maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations across the full range, with gestational hypertensive disorders.

Findings from our study do not support strong effects of non-fasting glucose concentrations in early pregnancy within the normal range on the risks of gestational hypertensive disorders. In clinical practice, testing for pregestational diabetes is only recommended among high-risk populations.28,30,42 As pregnancy physiologically influences the glucose metabolism, future studies focused on prepregnancy glucose concentrations may shed an important light on the effects of glucose concentrations on blood pressure, placental flow measures, and risk of gestational hypertensive disorders.

Strengths and limitations

We had a prospective data collection from early pregnancy onwards and a large low-risk sample of 6,078 women with detailed glucose measurements, blood pressure, placental flow measures, and information on gestational hypertensive disorders available. The response rate at baseline was 61%. The nonresponse at baseline might have led to selection of a healthier population. We had a population with a relatively low BMI, a low mean non-fasting glucose concentration, and the sample contained a small number of cases of gestational diabetes, indicating selection toward a nondiabetic population and might affect the generalizability of our findings to higher-risk populations in which stronger associations are expected. Blood sample collection was performed in a non-fasting state at different time points in the day. The minimum fasting time until blood sample collection was 30 minutes, due to the design of the study. The samples were therefore considered as non-fasting blood samples. Since glucose and insulin concentrations are sensitive toward carbohydrate intake and vary during the day, this may have led to non-differential misclassification and an underestimation of the observed effect estimates. We had no information available on oral glucose tolerance testing in pregnancy. Although we included many covariates, there still might be some residual confounding, as in any observational study. Further studies are needed to replicate our findings using more detailed maternal glucose metabolism measurements, including fasting glucose concentrations and detailed postprandial glucose measurements among higher-risk populations.

Maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations across the full range are associated with blood pressure in early pregnancy, but not later in pregnancy. Also, maternal early-pregnancy non-fasting glucose concentrations within the normal range are not associated with placental flow measures and gestational hypertensive disorders.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Generation R Study is conducted by the Erasmus Medical Center in close collaboration with the School of Law and Faculty of Social Sciences of the Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Municipal Health Service Rotterdam area, Rotterdam, the Rotterdam Homecare Foundation, Rotterdam, and the Stichting Trombosedienst and Artsenlaboratorium Rijnmond (STAR). We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of participating parents, children, general practitioners, hospitals, midwives, and pharmacies in Rotterdam.

FUNDING

The Generation R Study was supported by financial support by the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, and the Ministry of Youth and Families. Vincent Jaddoe received a grant from the European Research Council (Consolidator grant, ERC-2014-CoG-648916). Romy Gaillard received funding from the Dutch Heart Foundation (grant number 2017T013), the Dutch Diabetes Foundation (grant number 2017.81.002), and ZonMw (grant number 543003109).

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data are available by request from the corresponding author.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

JE, MG, and RG had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. Study concept and design: JE, MG, RG, and VJ. Analysis and interpretation of data: JE, MG, and RG. Drafting of the manuscript: JE, MG, RG, and VJ. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ferrara A. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a public health perspective. Diabetes Care 2007; 30(Suppl 2):S141–S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Catalano PM, McIntyre HD, Cruickshank JK, McCance DR, Dyer AR, Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Trimble ER, Coustan DR, Hadden DR, Persson B, Hod M, Oats JJ; Group HSCR . The hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome study: associations of GDM and obesity with pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care 2012; 35:780–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cvitic S, Desoye G, Hiden U. Glucose, insulin, and oxygen interplay in placental hypervascularisation in diabetes mellitus. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014:145846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vega M, Mauro M, Williams Z. Direct toxicity of insulin on the human placenta and protection by metformin. Fertil Steril 2019; 111:489–496.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lowe LP, Metzger BE, LoweWL, Jr., Dyer AR, McDade TW, McIntyre HD; Group HSCR . Inflammatory mediators and glucose in pregnancy: results from a subset of the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95:5427–5434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hauguel-de Mouzon S, Guerre-Millo M. The placenta cytokine network and inflammatory signals. Placenta 2006; 27:794–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoch D, Gauster M, Hauguel-de Mouzon S, Desoye G. Diabesity-associated oxidative and inflammatory stress signalling in the early human placenta. Mol Aspects Med 2019; 66:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Basak S, Das MK, Srinivas V, Duttaroy AK. The interplay between glucose and fatty acids on tube formation and fatty acid uptake in the first trimester trophoblast cells, HTR8/SVneo. Mol Cell Biochem 2015; 401:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pinter E, Haigh J, Nagy A, Madri JA. Hyperglycemia-induced vasculopathy in the murine conceptus is mediated via reductions of VEGF-A expression and VEGF receptor activation. Am J Pathol 2001; 158:1199–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carrasco-Wong I, Moller A, Giachini FR, Lima VV, Toledo F, Stojanova J, Sobrevia L, San Martín S. Placental structure in gestational diabetes mellitus. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020; 1866:165535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gauster M, Majali-Martinez A, Maninger S, Gutschi E, Greimel PH, Ivanisevic M, Djelmis J, Desoye G, Hiden U. Maternal Type 1 diabetes activates stress response in early placenta. Placenta 2017; 50:110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries WS, Robinson JS; Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women Trial G . Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2477–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jaddoe VW, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Steegers EA, Tiemeier H, Verhulst FC, Witteman JC, Hofman A. The Generation R Study: design and cohort profile. Eur J Epidemiol 2006; 21:475–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kooijman MN, Kruithof CJ, van Duijn CM, Duijts L, Franco OH, van IJzendoorn MH, de Jongste JC, Klaver CC, van der Lugt A, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Peeters RP, Raat H, Rings EH, Rivadeneira F, van der Schroeff MP, Steegers EA, Tiemeier H, Uitterlinden AG, Verhulst FC, Wolvius E, Felix JF, Jaddoe VW. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update 2017. Eur J Epidemiol 2016; 31:1243–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Geurtsen ML, van Soest EEL, Voerman E, Steegers EAP, Jaddoe VWV, Gaillard R. High maternal early-pregnancy blood glucose levels are associated with altered fetal growth and increased risk of adverse birth outcomes. Diabetologia 2019; 62:1880–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kruithof CJ, Kooijman MN, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, de Jongste JC, Klaver CC, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Raat H, Rings EH, Rivadeneira F, Steegers EA, Tiemeier H, Uitterlinden AG, Verhulst FC, Wolvius EB, Hofman A, Jaddoe VW. The Generation R Study: biobank update 2015. Eur J Epidemiol 2014; 29:911–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Silva LM. Fetal Origins of Socioeconomic Inequalities in Early Childhood Health: The Generation R Study. Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaillard R, Steegers EA, de Jongste JC, Hofman A, Jaddoe VW. Tracking of fetal growth characteristics during different trimesters and the risks of adverse birth outcomes. Int J Epidemiol 2014; 43:1140–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li H, Gudnason H, Olofsson P, Dubiel M, Gudmundsson S. Increased uterine artery vascular impedance is related to adverse outcome of pregnancy but is present in only one-third of late third-trimester pre-eclamptic women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2005; 25:459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. El Assaad MA, Topouchian JA, Darné BM, Asmar RG. Validation of the Omron HEM-907 device for blood pressure measurement. Blood Press Monit 2002; 7:237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gaillard R, Eilers PH, Yassine S, Hofman A, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW. Risk factors and consequences of maternal anaemia and elevated haemoglobin levels during pregnancy: a population-based prospective cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2014; 28:213–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coolman M, de Groot CJ, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Raat H, Steegers EA. Medical record validation of maternally reported history of preeclampsia. J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63:932–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brown MA, Lindheimer MD, de Swiet M, Van Assche A, Moutquin JM. The classification and diagnosis of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: statement from the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP). Hypertens Pregnancy 2001; 20:IX–XIV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gaillard R, Rurangirwa AA, Williams MA, Hofman A, Mackenbach JP, Franco OH, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW. Maternal parity, fetal and childhood growth, and cardiometabolic risk factors. Hypertension 2014; 64:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jaddoe VW, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, van der Heijden AJ, van Iizendoorn MH, de Jongste JC, van der Lugt A, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Raat H, Rivadeneira F, Steegers EA, Tiemeier H, Uitterlinden AG, Verhulst FC, Hofman A. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update 2012. Eur J Epidemiol 2012; 27:739–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Twisk JWR. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis for Epidemiology: A Practical Guide. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, Wood AM, Carpenter JR. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009; 338:b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Committee on Practice B-O. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2018; 131:e49–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). Diabetes in Pregnancy: Management of Diabetes and Its Complications from Preconception to the Postnatal Period; RCOG Press: London, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. International Association of D, Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus P, Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, Buchanan TA, Catalano PA, Damm P, Dyer AR, Leiva A, Hod M, Kitzmiler JL, Lowe LP, McIntyre HD, Oats JJ, Omori Y, Schmidt MI. International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010; 33:676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hartling L, Dryden DM, Guthrie A, Muise M, Vandermeer B, Donovan L. Benefits and harms of treating gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the National Institutes of Health Office of Medical Applications of Research. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159:123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lin S, Shimizu I, Suehara N, Nakayama M, Aono T. Uterine artery Doppler velocimetry in relation to trophoblast migration into the myometrium of the placental bed. Obstet Gynecol 1995; 85:760–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hughes RC, Moore MP, Gullam JE, Mohamed K, Rowan J. An early pregnancy HbA1c ≥5.9% (41 mmol/mol) is optimal for detecting diabetes and identifies women at increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care 2014; 37:2953–2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen L, Pocobelli G, Yu O, Shortreed SM, Osmundson SS, Fuller S, Wartko PD, Mcculloch D, Warwick S, Newton KM, Dublin S. Early pregnancy hemoglobin A1C and pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Am J Perinatol 2019; 36:1045–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stridsklev S, Carlsen SM, Salvesen Ø, Clemens I, Vanky E. Midpregnancy Doppler ultrasound of the uterine artery in metformin- versus placebo-treated PCOS women: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99:972–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pietryga M, Brazert J, Wender-Ozegowska E, Biczysko R, Dubiel M, Gudmundsson S. Abnormal uterine Doppler is related to vasculopathy in pregestational diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2005; 112:2496–2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cheung BM, Li C. Diabetes and hypertension: is there a common metabolic pathway? Curr Atheroscler Rep 2012; 14:160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hedderson MM, Ferrara A. High blood pressure before and during early pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2008; 31:2362–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Black MH, Zhou H, Sacks DA, Dublin S, Lawrence JM, Harrison TN, Reynolds K. Prehypertension prior to or during early pregnancy is associated with increased risk for hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and gestational diabetes. J Hypertens 2015; 33:1860–1867; discussion 1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fong A, Serra AE, Gabby L, Wing DA, Berkowitz KM. Use of hemoglobin A1c as an early predictor of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014; 211:641.e1–641.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Joffe GM, Esterlitz JR, Levine RJ, Clemens JD, Ewell MG, Sibai BM, Catalano PM. The relationship between abnormal glucose tolerance and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in healthy nulliparous women. Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention (CPEP) Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998; 179:1032–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moyer VA, Force USPST. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available by request from the corresponding author.