Abstract

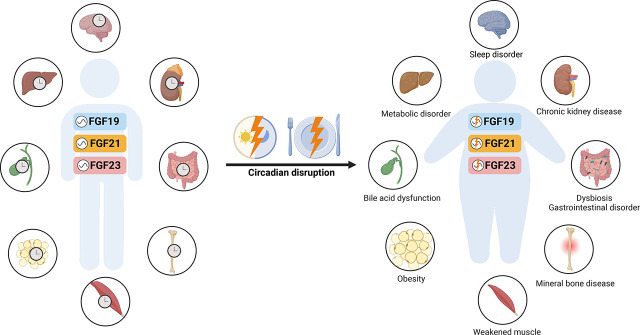

The circadian clock is an endogenous biochemical timing system that coordinates the physiology and behavior of organisms to earth’s ∼24-hour circadian day/night cycle. The central circadian clock synchronized by environmental cues hierarchically entrains peripheral clocks throughout the body. The circadian system modulates a wide variety of metabolic signaling pathways to maintain whole-body metabolic homeostasis in mammals under changing environmental conditions. Endocrine fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), namely FGF15/19, FGF21, and FGF23, play an important role in regulating systemic metabolism of bile acids, lipids, glucose, proteins, and minerals. Recent evidence indicates that endocrine FGFs function as nutrient sensors that mediate multifactorial interactions between peripheral clocks and energy homeostasis by regulating the expression of metabolic enzymes and hormones. Circadian disruption induced by environmental stressors or genetic ablation is associated with metabolic dysfunction and diurnal disturbances in FGF signaling pathways that contribute to the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases. Time-restricted feeding strengthens the circadian pattern of metabolic signals to improve metabolic health and prevent against metabolic diseases. Chronotherapy, the strategic timing of medication administration to maximize beneficial effects and minimize toxic effects, can provide novel insights into linking biologic rhythms to drug metabolism and toxicity within the therapeutical regimens of diseases. Here we review the circadian regulation of endocrine FGF signaling in whole-body metabolism and the potential effect of circadian dysfunction on the pathogenesis and development of metabolic diseases. We also discuss the potential of chrononutrition and chronotherapy for informing the development of timing interventions with endocrine FGFs to optimize whole-body metabolism in humans.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

The circadian timing system governs physiological, metabolic, and behavioral functions in living organisms. The endocrine fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family (FGF15/19, FGF21, and FGF23) plays an important role in regulating energy and mineral metabolism. Endocrine FGFs function as nutrient sensors that mediate multifactorial interactions between circadian clocks and metabolic homeostasis. Chronic disruption of circadian rhythms increases the risk of metabolic diseases. Chronological interventions such as chrononutrition and chronotherapy provide insights into linking biological rhythms to disease prevention and treatment.

Introduction

Circadian Rhythm

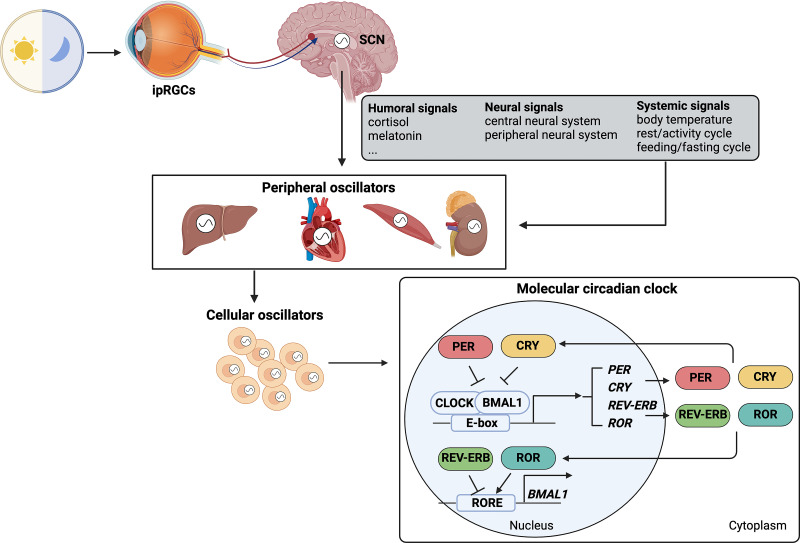

Circadian rhythms are ∼24-hour periodic oscillations in physiologic, behavioral, and metabolic processes primarily synchronized to external light/dark cycles (Bell-Pedersen et al., 2005). Diurnal rhythm is usually considered a rhythm that occurs during the day and is synchronized by the day/night cycle. Sometimes diurnal rhythm is not considered circadian until it has been shown to persist independent of meal timing, activity/sleep schedules, and environmental changes, only driven by the internal time-keeping system. Circadian rhythms reflect the organism’s ability to adapt to environmental conditions and are essential for survival and reproduction of living beings. Studies have demonstrated that circadian rhythms exist in almost all individual cells and exhibit a self-sustained and cell-autonomous manner that is independent of entraining signals (Ferrell and Chiang, 2015). These autonomous clocks must be synchronized to coordinate function of cells, tissues, organs, and behavior of the organism. In mammals, this is accomplished via the circadian timing system, comprising a central clock located within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus and peripheral clocks located in peripheral tissues and organs throughout the body (Fig. 1). The central pacemaker in the SCN entrained by primary Zeitgeber (German term for time giver), a light/dark cycle via specialized intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) in the eye, synchronizes peripheral clocks via neural innervation, hormone signaling, and other systemic cues (Buijs and Kalsbeek, 2001; Guo et al., 2005). Entrainment of peripheral clocks also occurs via direct input from the feeding/fasting cycle, rest/activity cycle, body temperature, and local signaling pathways, including metabolites and nuclear receptors (Mohawk et al., 2012). The feeding/fasting cycle can influence the circadian pattern of gene expressions and transcription factors that control metabolism, therefore regulating physiologic and metabolic processes in peripheral organs and tissues. By integrating environmental signals, organisms are able to coordinate circadian rhythms across different levels of temporal oscillations within the body from gene expressions, biologic responses, and ultimately biologic behaviors.

Fig. 1.

The circadian timing system across different levels within the entire body in mammals. The light/dark cycle as the primary Zeitgeber is sensed by ipRGCs in the eye. These cells directly send signals to the central circadian clock located within the SCN. The central pacemaker outputs humoral signals, neural signals, and systemic signals to peripheral clocks located in peripheral tissues and organs throughout the body. Moreover, systemic signals can directly entrain peripheral clocks. Mammalian cells exhibit self-sustained and cell-autonomous oscillations. Molecular machinery underlying the highly conserved circadian clock system in mammalian cells is characterized by the transcriptional-translational feedback loops.

Molecular machinery underlying the highly conserved circadian clock system in mammalian cells is characterized by the transcriptional-translational feedback loops, which generate the rhythmic outputs of a set of clock genes (CGs) and clock-controlled genes (CCGs) (Korenčič et al., 2014; Rijo-Ferreira and Takahashi, 2019) (Fig. 1). Two master transcription factors, brain and muscle Arnt-like 1 (BMAL1) and circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK), form the heterodimers to bind to the E-box elements in the promoters of CGs, including period (PER1, PER2, and PER3), cryptochrome (CRY1 and CRY2), nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D members (REV-ERBs), and retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (RORs) to promote their transcriptions. PER and CRY proteins form the negative limb of the circadian feedback loops to prevent BMAL1:CLOCK heterodimers from binding to E-box elements, thus suppressing the transcription activity of CGs. ROR proteins bind to ROR response elements (ROREs) to positively regulate BMAL1 expression, which can be counterbalanced by the role of REV-ERB via inhibiting ROREs (Ko and Takahashi, 2006). The core clock components further regulate downstream CCGs, of which circadian expressions mediate the circadian effects of physiologic, metabolic, and behavioral processes within the body (Lowrey and Takahashi, 2011; Han et al., 2015).

The circadian clock system orchestrates metabolism and energy homeostasis on a daily 24-hour cycle in mammals, including humans. Studies have shown that circadian gene networks regulate circadian rhythms of transcription factors, transcription and translational modulators, and metabolic enzymes involved in metabolism (Rijo-Ferreira and Takahashi, 2019). In turn, the circadian system receives inputs from nutrient signaling to establish feedback loops between the circadian system and energy metabolism (Bass and Takahashi, 2010). Importantly, disruption of circadian rhythms induced by multifaceted factors has been reported to affect physiologic and metabolic processes, resulting in metabolic disorders. These interconnections between circadian rhythms and metabolism underscore the importance of regulatory factors linking these two processes for maintaining whole-body metabolic homeostasis.

Fibroblast Growth Factor Family

In mammals, the FGF family is composed of phylogenetically and structurally related proteins that are classified into autocrine/paracrine (canonical) and endocrine FGFs (Beenken and Mohammadi, 2009). FGFs can exert their effects through binding to highly conserved transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors (FGFR1–4) (Turner and Grose, 2010). Canonical FGFs are characterized as paracrine/autocrine factors, which require heparin/heparan sulfate proteoglycans as cofactors to activate FGFRs and induce subsequent FGF-FGFR signaling pathways (Ornitz, 2000). Endocrine FGFs, including FGF15/19 (FGF15 is the mouse ortholog of human FGF19), FGF21, and FGF23, are circulating hormones that require Klotho proteins as cofactors to interact with FGFRs to regulate metabolic functions (Kurosu et al., 2006; Ogawa et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007). Klotho proteins are a class of single-pass transmembrane glycoproteins, and among them α-Klotho is responsible for the binding of FGF23 to FGFRs, while β-Klotho facilitates the binding of FGF15/19 and FGF21 to FGFRs (Kuro-o, 2019). The activation of the FGF-cofactor-FGFR complex drives the dimerization and activation of cytosolic tyrosine kinases, which further mediate downstream signal transduction pathways (Xie et al., 2020). The FGF11 subfamily is composed of four intracellular nonsignaling proteins (FGF11–FGF14), which are intracellular FGF homologous factors and do not have the ability to activate signaling FGFRs and thus are not included in the FGF family. The FGF family of signaling proteins regulates a variety of biologic development processes including cell proliferation, growth and differentiation, embryonic development, tissue patterning, brain development, limb development, angiogenesis, and wound healing and repair (Beenken and Mohammadi, 2009). Notably, endocrine FGFs play a crucial role in regulating whole-body metabolism and energy homeostasis by activating signaling pathways in bile acid (BA), glucose, protein, lipid, and mineral metabolism (Itoh and Ornitz, 2008).

In this review, we summarize the role of endocrine FGFs in the interconnection between circadian clocks and whole-body energy metabolism. Disruption of circadian rhythmicity in central or peripheral clocks is associated with dysregulation of endocrine FGF-related metabolic signaling pathways. Moreover, we discuss the current knowledge on chrononutrition and chronotherapy, which supports the feasibility of targeting endocrine FGFs as a circadian-dependent intervention to improve basic health and prevent metabolic diseases in humans.

FGF15/19 and Circadian Rhythm: Circadian Regulation of BA Metabolism

Physiologic Functions of Endogenous FGF15/19

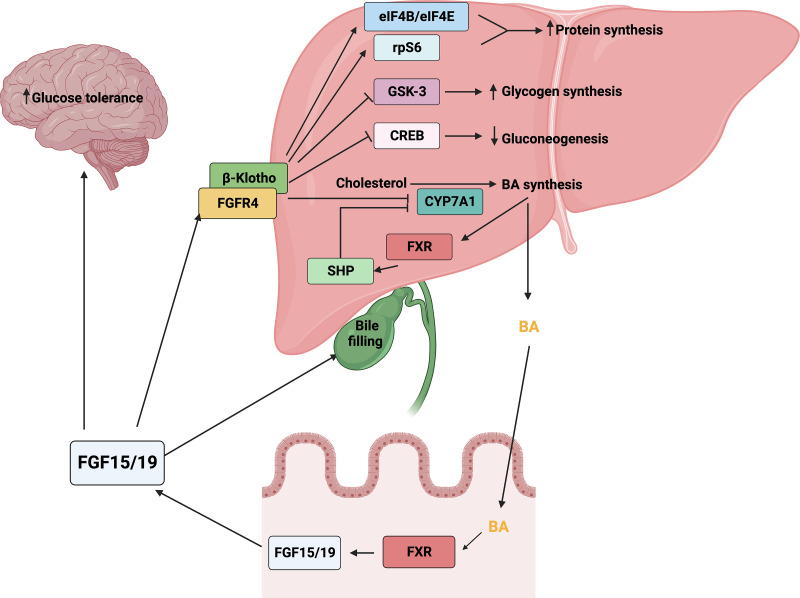

FGF15/19 is a late fed-state gut-derived hormone, which binds to FGFR4 and β-Klotho on the cell surface of hepatocytes to mediate postprandial hepatic responses (Guan et al., 2016). FGF15/19 has been identified as an important negative regulator to maintain BA homeostasis. BAs are powerful detergents and are produced from cholesterol by the cholesterol-7α-hydroxylase (cytochrome P450 7A1/CYP7A1) and CYP27A1. BA synthesis is finely regulated by the intrahepatic BA-farnesoid X receptor (FXR)-small heterodimer partner (SHP) and enterohepatic BA-FXR-FGF15/19 feedback signaling pathways (Fig. 2). BAs act as ligands of the hepatic nuclear receptor FXR, which induces the transcription of SHP responsible for the suppression of CYP7A1 transcription within the intrahepatic BA feedback signaling pathway (Lu et al., 2000). In the enterohepatic BA-FXR-FGF15/19 signaling pathway, gut BAs activate ileal FXR to induce the gene expression of Fgf15/FGF19, which in turn functions as an endocrine signal and binds to FGFR4 with β-Klotho on hepatocytes to inhibit CYP7A1 expression, thus resulting in the suppression of BA biosynthesis (Inagaki et al., 2005). Accordingly, Fgf15-knockout (KO) mice presented elevated expressions of Cyp7a1 and BA levels, whereas administration of recombinant FGF15 restored the ability to repress BA synthesis (Kok et al., 2003; Inagaki et al., 2005). Moreover, FGF15/19 regulates the metabolism of protein and glucose in the liver. FGF15/19 activates the phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 4B and 4E (eIF4B and eIF4E) and ribosomal protein S6 (rpS6), which promotes hepatic protein synthesis (Kir et al., 2011). FGF15/19 regulates hepatic glucose metabolism by enhancing glycogen synthesis through inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase 3 and suppressing gluconeogenesis through inactivating cAMP-response element binding protein (Kir et al., 2011; Potthoff et al., 2011). FGF19 has also been shown to act in the brain to improve glucose tolerance in rodents (Morton et al., 2013; Ryan et al., 2013). In addition, FGF15 was shown to maintain the homeostasis of temporal feeding/fasting signal-induced gallbladder motility by promoting the bile refilling in the gallbladder in opposite to cholecystokinin action (Choi et al., 2006). These findings demonstrate a relatively clear mechanism by which enterohepatic signal FGF15/19 plays a crucial role in regulating BA metabolism and homeostasis.

Fig. 2.

The signaling pathways and pleiotropic metabolic effects of FGF15/19. Systemic FGF15/19 binds to FGFR4 and β-Klotho on the cell surface of hepatocytes to mediate postprandial hepatic responses, including increased protein and glycogen synthesis and inhibited gluconeogenesis and BA synthesis. BA synthesis is finely regulated by the intrahepatic BA-FXR-SHP and enterohepatic BA-FXR-FGF15/19 feedback signaling pathways.

In addition, FGF15/19 coordinates glucose and protein metabolism with BA metabolism to govern postprandial responses. FGF15/19 functions subsequent to insulin but independent of insulin to regulate postprandial hepatic glucose metabolism by promoting glycogen synthesis and inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis (Kir et al., 2011; Potthoff et al., 2011). Moreover, systemic administration or intracerebroventricular injection of FGF19 enhanced glucose tolerance and decreased glucose levels in ob/ob mice in an insulin-independent manner (Morton et al., 2013). FGF19 administration in wild-type mice promotes protein synthesis in the liver (Kir et al., 2011).

Circadian Regulation of FGF15/19

In humans, the metabolic switch between anabolic and catabolic activities following the feeding/fasting state is under circadian control. The liver circadian clock, one of most important peripheral oscillators, links the core circadian clock to organismal physiology including energy metabolism, nutrient homeostasis, and detoxification (Reinke and Asher, 2016). Recent studies have demonstrated that the liver clock governs some metabolic processes including glycogen metabolism and NAD+ salvage metabolism independent of the central circadian clock (Koronowski et al., 2019). Studies have shown that the tight regulation of BA metabolism by circadian clocks is characterized by oscillations of BA, rate-limiting enzymes, transcription factors, and CCGs involved in BA metabolism (Adamovich et al., 2014). The circulating BA level shows a significant diurnal rhythm with two postprandial rises in humans (Lundasen et al., 2006). The surrogate marker of CYP7A1 enzyme activity, 7alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one, also shows related diurnal variations in healthy subjects. The oscillation of circulating FGF19 levels is closely associated with BA synthesis (Lundasen et al., 2006; Al‐Khaifi et al., 2018). Specifically, the serum FGF19 levels present the diurnal rhythm with peaks occurring 90 to 120 minutes after the postprandial BA surge. In turn, FGF19 peaks induce the reduction of BA synthesis, reflecting FGF19-mediated rhythmic inhibition of BA synthesis.

In mice, BAs in serum, liver, intestine, and gallbladder exhibit circadian oscillations with one peak at dark phase (active/feeding phase) (Zhang et al., 2011; Han et al., 2015). Accordingly, circadian rhythms of intestinal Fgf15 expression and circulating FGF15 level were observed, presenting a single peak at the end of the dark phase and a nadir at the end of the light phase (rest/fasting period) (Stroeve et al., 2010; Han et al., 2015). Intestine-specific Fxr null mice blunted circadian rhythmicity and expressions of ileal Fgf15 while increasing circadian rhythmicity and expression of hepatic Cyp7a1. These findings highlight an important role of circadian control of the enterohepatic FXR-FGF15-CYP7A1 signaling pathway in regulating BA metabolism. In turn, BA might regulate the circadian rhythmicity of FGF15. Cholecystectomy not only abolished the circadian rhythms and levels of BA pools, hepatic and ileal BAs, but also disrupted circadian rhythm and decreased mRNA levels of ileal Fgf15 expression in mice (Zhang et al., 2018a). However, the ileum-derived transcription factor Kruppel-like factor 15 has been identified as an endogenous negative circadian regulator of ileal Fgf15 expression and serum FGF15 levels independent of the hepatic BA-intestinal FXR signaling pathway (Han et al., 2015). Accordingly, genetic ablation of Klf15 altered circadian patterns of ileal Fgf15 mRNA and serum FGF15 levels.

FGF21 and Circadian Rhythm: Circadian Regulation of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism

Physiologic Functions of Endogenous FGF21

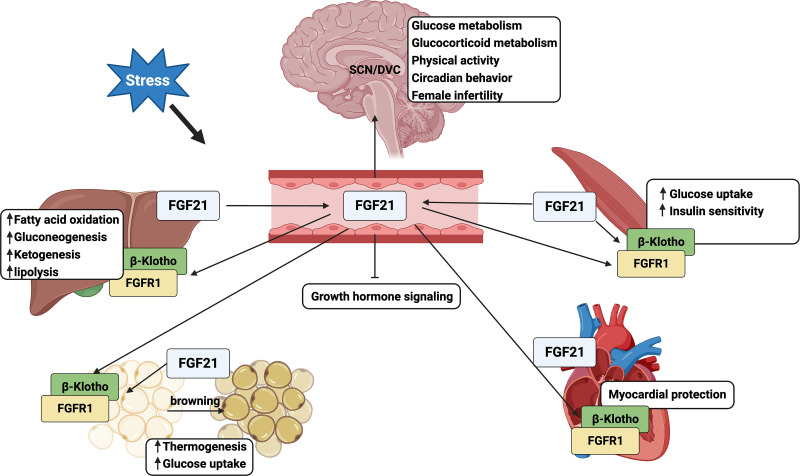

FGF21 is an endocrine starvation hormone and plays a crucial role in regulating glucose and lipid metabolism, thermogenesis, and insulin sensitivity. FGF21 is primarily expressed in the liver and adipose tissues and, to a much lower extent, in the skeletal muscle, heart, kidney, testis, and pancreas (Itoh, 2014). In response to different stresses such as fasting, fasting-refeeding regimen, high-carbohydrate and ketogenic diets, and cold, FGF21 binds to FGFR1 and coreceptor β-Klotho expressed on the cell membrane of target tissues to initiate signaling pathways in either an endocrine or autocrine/paracrine manner (Badman et al., 2007; Oishi et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2012) (Fig. 3). Hepatokine FGF21 has been shown to induce fatty acid oxidation, lipolysis, ketogenesis, and gluconeogenesis in response to fasting in mice (Badman et al., 2007; Potthoff et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016). Additionally, fasting-induced FGF21 inhibits growth hormone signaling (Inagaki et al., 2008). Adipokine FGF21 mediates thermogenesis, glucose uptake, and white adipose tissue (WAT) browning, mainly in an autocrine/paracrine manner (Fisher et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2013). Myokine FGF21 not only enhances insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and myocardial protection in heart but also circulates into WAT to regulate energy metabolism and thermogenesis (Kim et al., 2013; Keipert et al., 2014; Planavila et al., 2015; Jeon et al., 2016). Notably, circulating FGF21 can act on the SCN or dorsal vagal complex (DVC) area in the brain to regulate glucose and glucocorticoid metabolism, physical activity, circadian behavior, and female fertility, resembling adaptive starvation responses (Owen et al., 2013; Cornu et al., 2014). The physiologic roles of FGF21 in humans may differ from those in mice. In humans, circulating FGF21 levels greatly increased after 7-day fasting, but levels remained unchanged levels after 2-day fasting, suggesting a late adaptive response to fasting (Li et al., 2014). Moreover, FGF21 induction inhibited thermogenesis and adiponectin and did not induce ketogenesis in humans (Fazeli et al., 2015).

Fig. 3.

The pleiotropic metabolic effects of FGF21. The physiologic and metabolic actions of FGF21 are mediated by its fine-tuning of intra- and interorgan metabolic crosstalk.

Circadian Regulation of FGF21

The oscillation pattern of circulating FGF21 levels is context-specific in human studies. Circulating FGF21 levels display a diurnal oscillation pattern with a peak in the early morning and decreased levels during the day with a nadir in the early evening, followed by increased levels during the night in healthy women (Foo et al., 2013), whereas no circadian variation of circulating FGF21 levels was identified in healthy men (Foo et al., 2015). The circadian variation in FGF21 levels shows sexual dimorphism in the fed state, probably due to sex differences in lipid metabolism. However, no sexual difference was identified for the circadian rhythm of circulating FGF21 levels in Yu et al.’s study (Yu et al., 2011). The circadian level of circulating FGF21 resembles the circadian rhythmicity of free fatty acids (FFAs) and cortisol, whereas opposite to oscillatory patterns of insulin and glucose (Yu et al., 2011). Foo et al. also identified positive correlations between circulating FFAs and FGF21 levels in either the fed or fasted state (Foo et al., 2013). Effects of fasting duration on the circadian rhythm of FGF21 levels are controversial. No significant alterations were identified in the physiologically circadian rhythmicity of FGF21 levels in response to 48-hour or even 72-hour fasting (Gälman et al., 2008; Christodoulides et al., 2009; Andersen et al., 2011). However, Foo et al. reported that 72-hour fasting in healthy females diminished the circadian pattern of FGF21 with significant increased levels, which was associated with prolonged fasting-induced lipolysis (Foo et al., 2013). Moreover, the environmental temperature signal such as mild cold exposure induced diurnal changes of the circulating FGF21 levels, which was associated with cold-induced metabolic changes, including increased lipolysis and thermogenesis in humans (Lee et al., 2013).

The circadian expression of FGF21 in rodents remains controversial and greatly controlled by fasting and circadian regulation. Circadian clock-controlled transcription factors including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), RORα, REV-ERBs, and E4 promoter–binding protein 4 (E4BP4) have been shown to directly control the circadian expression and secretion of FGF21 (Oishi et al., 2008; Estall et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010). The PPARα nuclear receptor can directly sense fasting signals and induce fasting adaptive responses by regulating the expression of numerous genes involved in lipid metabolism, including induction of hepatic Fgf21 expression (Lundåsen et al., 2007). Compared with relatively constant Fgf21 expression in control groups, PPARα agonist induced the circadian expression of hepatic Fgf21 in mice, which was diminished in PPARα-deficient mice (Oishi et al., 2008). Interestingly, only nighttime administration of PPARα agonist promoted the circadian expression of Fgf21, suggesting circadian regulation of Fgf21 in response to nighttime fasting cues. Therefore, the circadian induction of Fgf21 expression may allow the circadian timing system to detect and respond to unusual metabolic states. RORs bind to the RORE site in the proximal promoter of the Fgf21 gene to promote its expression whereas REV-ERBs exert opposite effects (Estall et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010). The circadian output protein E4BP4 is responsible for the circadian regulation of Fgf21 expression independent of PPARα activation. Hepatic Fgf21 expression exhibits a circadian phase opposite to the circadian pattern of E4BP4, indicating the role of E4BP4 as a transcription repressor of Fgf21 expression in response to feeding (Tong et al., 2010). Moreover, knockdown of E4bp4 disrupted the circadian rhythmicity of hepatic Fgf21 expression in mice. PPARα and E4BP4 are both important circadian clock regulators that mediate the circadian oscillations of hepatic Fgf21 expression in response to the feeding/fasting cycle.

FGF21 may directly act on the SCN of the hypothalamus or DVC of the hindbrain to regulate systemic glucocorticoid levels, circadian behavior, physical activity, and female ovulation as adaptive starvation responses (Bookout et al., 2013; Owen et al., 2013). Abundant expressions of βKlotho in the SCN or DVC are key factors to mediate FGF21 signaling in the brain. FGF21 modulates circadian behavior and might be mediated by suppressing SCN output. However, overexpression of Fgf21 caused modest changes in CG expressions in liver but no changes in CG expressions in the SCN, suggesting the complex role of FGF21 in the regulatory feedback loop within the liver-to-brain hormonal axis. Fgf21 KO mice did not show any difference in free-running periods of locomotor activity rhythm, circadian expressions of hepatic and WAT CGs, and food anticipatory activity (Bookout et al., 2013). These studies suggest the complex but dispensable role of FGF21 in regulating the rhythm of central and peripheral circadian oscillators.

FGF23 and Circadian Rhythm: Circadian Regulation of Mineral Metabolism

Physiologic Functions of Endogenous FGF23

FGF23 is a bone-derived endocrine hormone. It is a small glycoprotein composed of FGF homology N-terminal domain, FGF23-specific C-terminal domain for interacting with FGFR1 and α-Klotho, and a specific proteolytic cleavage site between N-terminal and C-terminal domains (Vervloet and Larsson, 2011). Cleavage at the proteolytic cite by furin-like enzymes inactivates FGF23, resulting in the formation of C-terminal fragments. FGF23 regulates homeostasis among parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D, phosphate, and calcium, primarily via binding to the FGF1-α-Klotho complex on the kidney and parathyroid glands (Fig. 4). Mineral signals including increased vitamin D, PTH, and phosphate can directly act on bone cells to stimulate FGF23 expression and secretion (Shimada et al., 2005). In turn, endocrine FGF23 acts on the kidney to upregulate Cyp24a1 and downregulate Cyp27b1 expression to decrease 1, 25(OH)2D3 synthesis (Liu et al., 2006). Additionally, FGF23 signaling inhibits the renal membrane expression of sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters (NaPi2a and NaPi2c), resulting in the suppression of phosphate reabsorption (Gattineni et al., 2009). FGF23 acts on the parathyroid to suppress PTH production in response to increased PTH levels (Lanske and Razzaque, 2014; Ben-Dov et al., 2007). FGF23 fine-tunes mineral metabolism via negative feedback within the bone-kidney-parathyroid homeostatic network. The disturbance of any factor in this network would disrupt mineral metabolism leading to mineral-related diseases. Klotho not only serves as the coreceptor for FGF23 signaling but also circulates as an endocrine signal to inhibit PTH and vitamin D production (Hu et al., 2013). Fgf23 KO mice and Klotho KO mice shared many major phenotypes including dysregulated mineral metabolism, presented as increased circulating calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D levels and aging-like changes (Kuro-o et al., 1997; Shimada et al., 2004).

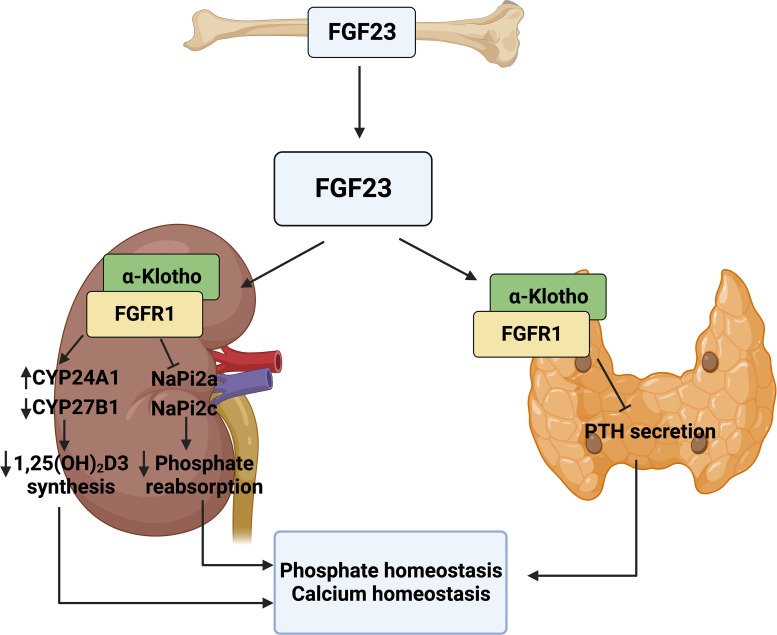

Fig. 4.

The pleiotropic metabolic effects of FGF23. FGF23 released from the bone binds to FGFR1 and α-Klotho on the kidney and parathyroid gland to finely regulate mineral metabolism within the bone-kidney-parathyroid homeostatic network.

Circadian Regulation of Endogenous FGF23

Circadian rhythms play an important role in regulating mineral homeostasis and bone health. Circadian rhythms control the oscillation in associated mineral parameters including FGF23, α-Klotho, PTH, phosphate and calcium, and other markers of bone turnover (Swanson et al., 2018). The circadian rhythmicity of FGF23 in different human studies is context-specific and controversial. Two studies examined the circadian oscillation of intact serum FGF23 (iFGF23) and C-terminal FGF23 (cFGF23) levels, representing active and inactive FGF23, respectively. Vervloet et al. identified different oscillating patterns of iFGF23 and cFGF23, with iFGF23 peaking in the early morning and decreasing during the day and cFGF23 increasing during the daytime and peaking in the late afternoon (Vervloet et al., 2011). Smith et al. observed diurnal rhythmicity of iFGF23 with the peak in the early morning and the nadir in the evening but no circadian oscillation for cFGF23 (Smith et al., 2012). The circadian magnitude of iFGF23 was consistent with that of plasma PTH and serum phosphate levels with about an 8- to 12-hour phase delay, indicating their interconnection is under circadian control. Swanson et al. showed that serum iFGF23 levels presented circadian rhythmicity with peak variations between late night to morning in men (Swanson et al., 2017). Carpenter et al. only observed the circadian oscillation of circulating Klotho levels but no rhythmicity of iFGF23 and phosphate (Carpenter et al., 2010). The clinical difference between iFGF23 and cFGF23 function has not been well elucidated. Recent studies suggested that alteration in the levels of cFGF23 and iFGF23 might be the pathophysiological signals in different disease states including fibrous dysplasia, iron deficiency, and kidney transplant graft loss (Bhattacharyya et al., 2012; Chu et al., 2021). Hence, the significance of biologic variations in circadian rhythmicity of either iFGF23 or cFGF23 levels requires further study before clinical application as diagnostic or interventional biomarkers in humans.

Rodents present a relatively distinct circadian rhythm of Fgf23 expression. Studies indicated that circadian clocks regulate skeletal Fgf23 expression through sympathetic activation induced by food intake in mice. The timing of dietary phosphate is considered the predominant factor to determine the circadian oscillation of skeletal Fgf23 gene expression levels (Kawai et al., 2014). Plasma FGF23, PTH, and phosphate in rats present similar circadian patterns with a peak in the afternoon, indicating circadian regulation of the bone-kidney- parathyroid network (Nordholm et al., 2019). In conclusion, the circadian rhythmicity of FGF23 is closely linked to that of other mineral markers, reflecting an endogenous circadian rhythm important for normal bone and mineral metabolism.

Circadian Disruption and Endocrine FGF Dysregulation

Circadian misalignment between environmental cues and internal rhythms results in circadian disruption, which leads to dysregulation of physiology, metabolism, and behavior in living organisms. Shift work, social jet lag, and artificial light exposure at night can impose abnormal light/dark cues on the central clock SCN, resulting in disturbance of internal timing synchronization and circadian disruption. Long-term shift work has been associated with increased risks of many diseases including sleep disorders, psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer (Allada and Bass, 2021). Shift work alters the rhythm of light exposure and feeding behavior, such as phase shifts or amplitude changes, which could serve as strong signals sent to central and peripheral molecular clocks, leading to varying degrees of phase shifts and amplitude changes. Bright light exposure at night caused a significant phase shift of core body temperature rhythm (Duffy et al., 1996). Central circadian markers, including melatonin, cortisol, and core body temperature, have been shown to present reduced or distorted amplitudes or phase shifts in subjects working night shifts (Goh et al., 2000; Harris et al., 2010; Leichtfried et al., 2011; Bracci et al., 2016; Molzof et al., 2019). Targeted plasma metabolomics identified that 95% of rhythmic metabolites showed phase shifts but with 24-hour circadian rhythmicity in participants under constant routine schedules following 3-day simulated night-shift work compared with day-shift work (Skene et al., 2018). Shift work associated with recurrent disruption of rest/activity rhythms usually leads to altered food access and unfavorable eating patterns, including an irregular eating schedule and an unhealthy, high-fat, and high-sugar diet. These changes in feeding patterns are associated with disruption of peripheral clocks, which results in an increased risk of metabolic disorders. The phase shift of feeding time from active to rest phase induced misalignment between central and peripheral circadian clocks, which leads to metabolic syndrome in mouse models (Mukherji et al., 2015). Night-eating syndrome, an eating disorder characterized by a delayed circadian pattern of food intake relative to a normal sleep/wake cycle, is strongly associated with obesity in populations (Cleator et al., 2012). In rodents, circadian disruption induced by genetic or environmental stressors disturbs metabolic homeostasis. Genetic ablation of CGs including PER2, CLOCK, and/or BMAL1 led to increased food intake during rest time, decreased circadian behavior, impaired insulin action, and increased serum levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, and glucose, which lead to obesity and metabolic syndrome in mice (Turek et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2013). Artificial light exposure at night induced elevated food intake during the normal rest period, leading to increased body mass and decreased glucose tolerance in mice (Fonken et al., 2010). Time-delayed eating behavior caused glucose intolerance and irregular lipid metabolism, which contributed to the occurrence of obesity and lipid disorders in mice (Wu et al., 2015).

Endocrine FGFs are important regulators of metabolism and energy homeostasis and are well controlled by the coordination between external signals and the internal circadian timing system. However, the possibility of a direct association between circadian disruption and dysregulation of FGF15/19 expression remains unclear. Acute daytime fasting diminished the rhythmicity of circulating BA and FGF19 levels in rodents and humans (Lundåsen et al., 2006). Studies have identified that genetic ablation of Per1/Per2 in mice induced dysregulation of BA homeostasis shown as increased BA levels and abolished rhythmicity of Cyp7a1 expression, which may contribute to the disturbance of Fgf15 expression (Ma et al., 2009).

Circadian disruption is associated with dysregulation of circadian expression and metabolism of FGF21 and FGF23, resulting in metabolic impairments and disease pathogenesis. In humans, acute sleep loss induced the elevation of circulating FGF21 levels under both feeding and fasting situations, indicating the central circadian misalignment (Mateus Brandão et al., 2022). Compared with the relatively constant pattern of FGF21 levels in response to prolonged feeding, altered circulating FGF21 levels in response to central misalignment may indicate the important role of the central clock in synchronizing environmental cues, behavior, and metabolism. Increased circulating FGF21 levels have also been found in patients diagnosed with type II diabetes, obesity, coronary heart disease, and metabolic syndrome (Xie and Leung, 2017). The diurnal rhythmicity of circulating FGF21 was abolished in obese subjects with significantly increased levels compared with lean subjects (Yu et al., 2011). The persistently high FGF21 levels may lead to desensitization or resistance of FGF21, which contributes to metabolic dysfunction in obese patients. Lee et al. observed that obese individuals showed increased numbers of larger oscillations of serum FGF21 compared with nonobese individuals, suggesting unstable metabolic states in obese individuals (Lee et al., 2012). The identification of circadian disruption of circulating FGF21 levels in patients with metabolic disorders suggests the possibility of monitoring the circadian rhythmicity of FGF21 levels as a biomarker for disease development and/or as intervention endpoints in clinical trials.

Environmental and behavioral stressors including changes in lighting conditions and sleep/wake and feeding/fasting patterns have been identified to cause circadian disruption of Fgf21 expression in rodents, an indicator of metabolic desynchrony. Exposure to artificial light at night with protein restriction feeding disturbed circadian glucose metabolism shown as the inversed circadian pattern of hepatic Fgf21 expression in mice (Borck et al., 2021). Nutrient redundancy in mice caused circadian disruption of molecular clocks presented as circadian dysregulation of CG expressions and nuclear receptor network, which directly or indirectly disturb the circadian expression of CCGs and circadian regulatory genes (Kohsaka et al., 2007). A high-fat diet altered the circadian rhythmicity of Fgf21 expression in the mouse liver and WAT, whereas a ketogenic diet completely abolished the circadian rhythmicity of Fgf21 expression, indicating the impaired circadian regulation of fat metabolism (Chapnik et al., 2017). Additionally, genetic ablation of circadian gene Cry blunted the circadian level of hepatic Fgf 21 expression in mice treated with caloric restriction (Mezhnina et al., 2022).

Circadian disruption of mineral homeostasis is associated with renal and bone diseases (Johnston and Pollock, 2018). Chronic shift workers often present increased bone resorption and decreased bone mineral density, which may contribute to osteoporosis and bone fracture (Feskanich et al., 2009; Quevedo and Zuniga, 2010). These might be due to decreased sun exposure and physical activity and/or increased cortisol and inflammation in night-shift workers. Short sleep duration in shift workers has been identified to increase the risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Sasaki et al., 2014). Shift work is also associated with dysregulation of bone turnover markers including increased FGF23 and α-Klotho levels and decreased vitamin D levels (Min et al., 2020). Feeding/fasting alteration is considered another important cause of circadian disruption. In mice, food intake switched from the dark phase to the light phase shifted the circadian rhythm of skeletal Fgf23 expression by altering sympathetic activity, suggesting the role of the central circadian clock in linking feeding cues and metabolic output (Kawai et al., 2014). Phosphate loading significantly elevated both circulating iFGF23 and cFGF23 levels with altered circadian patterns, which contributes to phosphaturia and vitamin D metabolic disturbance (Vervloet et al., 2011). Abolished circadian rhythmicity of mineral parameters including circulating phosphate, calcium, PTH, and FGF23 has been demonstrated in CKD and CKD-mineral bone disease, indicating the role of circadian disruption in the pathogenesis of renal and bone dysfunction (Nordholm et al., 2019; Egstrand et al., 2020). Dysregulated circadian rhythm of mineral parameters is also associated with the pathophysiology of hypophosphatemia (Noguchi et al., 2018). In addition, great and rapid alterations in FGF23 levels have been identified in mice with acute kidney injury (Egli-Spichtig et al., 2018). These findings indicate that the circadian rhythmicity of mineral regulatory factors may be considered as biomarkers for mineral dysregulation and diseases in animals and humans.

Circadian Nutrition and Medication in Human Health

Chrononutrition

Feeding/fasting environmental cues function as powerful Zeitgebers in the circadian timing system to synchronize peripheral clocks, leading to rhythmic regulation of energy metabolism (Pickel and Sung, 2020). Temporal regulation of feeding has been recognized as an effective nonpharmacological intervention strategy to maintain metabolic homeostasis (Sunderram et al., 2014). Chrononutrition refers to modulating temporal feeding patterns to regulate nutrient metabolism and improve metabolic health under circadian control. The most common type of chrononutrtion is time-restricted feeding (TRF), which restricts food intake within 8 to 12 hours during the active phase without caloric intake restriction (Longo and Panda, 2016). We summarize the pleiotropic effects of TRF in animal and human studies in Table 1. In rodents, TRF imparts pleiotropic benefits including increased glucose tolerance and motor coordination; decreased body weight gain, adiposity, and inflammation; and improved nutrient and metabolism homeostasis. Caloric restriction is considered the most robust nonpharmacologic intervention known to decrease body weight, improve health, and prevent diseases. However, TRF in mice fed obesogenic diets without caloric restriction in the active phase decreased body weight gain, inflammation, and oxidative stress and improved metabolic rhythms, glucose, lipid and BA metabolism, nutrient homeostasis, and gut microbial abundance, thus preventing metabolic disorders (Hatori et al., 2012; Chaix et al., 2014; Ye et al., 2020). Moreover, TRF only conducted during weekdays with ad libitum on weekends also prevented mice fed high-fat and high-glucose diets from developing metabolic diseases (Chaix et al., 2014). TRF improved insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, pulsatile growth hormone secretion, and immune homeostasis and alleviated hyperinsulinemia in overweight or obese mice (Kim et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). Diabetic mice presented abnormal sleep/wake cycles, which could be improved by TRF during the active phase (Hou et al., 2019). Moreover, circadian disruption induced by the altered light/dark cycle in diabetic mice promoted Alzheimer's disease progression, which could be improved by TRF (Peng et al., 2022). Circadian disruption induced by other factors including chronic jetlag or genetic ablation of circadian genes was restored in mice treated with TRF (Chaix et al., 2019). However, TRF impaired fertility competence, which might be attributed to decreased serum lipids and increased oxidative stress in oocytes in mice (Konishi et al., 2022).

TABLE 1.

Summary of Pleiotropic Effects of TRF in Rodent and Human Studies

| Intervention | Study Models | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRF 8 h/d in the active phase | Mice (high-fat diet) | Decreased body weight gain and inflammation, increased diurnal rhythms, improved glucose and BA metabolism, hepatic and adipose tissue homeostasis | Hatori et al., 2012 |

| TRF 8–9 h/d in the active phase | Mice (high-fat, high-fructose, and high-fat + high-fructose diets) | Decreased body weight gain, whole-body fat accumulation, inflammation, oxidative stress, glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, and improved nutrient homeostasis and cholesterol homeostasis | Chaix et al., 2014 |

| TRF 8 h/d in the active phase | Mice fed with high-fat diet | Decreased body weight gain, liver steatosis, and hepatic triglyceride, increased circadian rhythm of hepatic CCG expressions and gut microbial abundance | Ye et al., 2020 |

| TRF 9–12 h/d in the active phase | Obese mice | Decreased hyperinsulinemia and improved pulsatile growth hormone secretion and energy metabolism | Wang et al., 2022 |

| TRF 10h/d in the active phase | Overweight or obese mice | Reduced monocyte production | Kim et al., 2022 |

| TRF 8 h/d in the active phase | Diabetic mice | Improved sleep/wake cycle | Hou et al., 2019 |

| TRF 8h/d in the active phase | Diabetic mice with altered light/dark cycle | Improved circadian disruption-induced body weight gain, lipid accumulation, and cognition impairment | Peng et al., 2022 |

| TRF in the active phase | Chronically jetlagged mice | Reestablished food intake pattern, improved ghrelin circadian rhythmicity of gene expressions, plasma ghrelin, and body mass | Desmet et al., 2021 |

| TRF 9–10 h/d in the active phase | Mice (circadian mutant mice fed with isocaloric with 60% high-fat diet) | Decreased body weight gain, lipid accumulation, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance and enhanced diurnal rhythms of fuel utilization | Chaix et al., 2019 |

| TRF 8 h/d in the active phase | Mice | Decreased fertility competence | Konishi et al., 2022 |

| TRF 8 h/d from 19:30 to 03:30 | Humans (healthy men) | Altered gut microbial composition and abundance and dietary nutrient intake | Zeb et al., 2020 |

| TRF 8 h/day from 10:00 to 18:00 | Humans (obese men) | Decreased body weight, energy intake, and systolic blood pressure | Gabel et al., 2018 |

| TRF 9 h/day from 08:00 to 17:00 or 12:00 to 21:00 | Humans (overweight men) | Improved glucose tolerance | Hutchison et al., 2019 |

| TRF 10 h/day | Humans (patients with metabolic syndrome) | Decreased body weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, LDL-C, non-HDL-C, and hemoglobin A1c and increased restful sleep | Wilkinson et al., 2020 |

| TRF 8 h/day from 10:00 to 18:00 | Humans (overweight or obese men) | Decreased nocturnal blood glucose, positive attitude, and improved feelings | Parr et al., 2020 |

| TRF 6 h/d from 08:00 to 14:00 | Humans (overweight adults) | Decreased 24-h blood glucose and glycemic excursions and improved lipid metabolism and circadian rhythms of cortisol and CG expression | Jamshed et al., 2019 |

| TRF 6 h/d with dinner before 15:00 | Humans (prediabetic men) | Increased insulin sensitivity, pancreatic β cell function, decreased postprandial insulin, blood pressure, oxidative stress, and appetite | Sutton et al., 2018 |

| TRF 10 h/day from 08:00 to 18:00 | Humans (overweight adults with type II diabetes) | Improved glucose and insulin sensitivity, decreased triglyceride, total cholesterol, and LDL-C | Che et al., 2021 |

| TRF 8 h/d | Humans (overweight, older adults) | Decreased body weight | Anton et al., 2019 |

| TRF 8 h/d from 08:00 to 16:00 | Humans (women with anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome) | Decreased body weight, hyperandrogenemia, insulin resistance, and chronic inflammation and improved menstruation | Li et al., 2021 |

HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

In healthy humans, TRF treatment altered abundance and composition of gut microbiota, thus affecting the host nutritional status, metabolism, and defense (Zeb et al., 2020). TRF is associated with food intake alteration, weight loss, decreased blood pressure and oxidative stress, and improved lipid and glucose metabolism in obese or overweight humans (Gabel et al., 2018; Hutchison et al., 2019; Parr et al., 2020; Wilkinson et al., 2020). TRF also improved glucose and insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and body weight loss in overweight subjects with type II diabetes (Che et al., 2021). Moreover, TRF has been identified as a feasible intervention method to decrease body weight and improve health in older overweight adults (Anton et al., 2019). For women with anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome, TRF decreased body weight, hyperandrogenemia, insulin resistance, and chronic inflammation and improved menstruation (Li et al., 2021). However, TRF effects were inconsistent in different human TRF trials, possibly due to different types of interventions and their duration, study scale, and biologic variations. A recent study identified early TRF, which restricts food intake from 08:00 to 14:00, improved the 24-hour circadian rhythm of glucose levels and altered gene expressions in lipid metabolism, circadian clock, and autophagy, which may elicit anti-aging effects (Jamshed et al., 2019), whereas either early (08:00 to 17:00) or late (12:00 to 21:00) TRF improved glucose tolerance in overweight men (Hutchison et al., 2019). One study identified that TRF uncoupled peripheral metabolic clocks in the liver clock from the central oscillator, suggesting a complex role of feeding time independent of the core circadian clock (Hara et al., 2001).

Temporal patterns of restricted food intake contribute to the improvement of circadian regulation of BA homeostasis, thus exerting protective effects against metabolic disorders and BA-related diseases. Compared with ad libitum feeding, TRF either in the active or the rest phase in rats improved the circadian rhythmicity of plasma BAs with significantly increased levels (Eggink et al., 2017). Moreover, TRF in the active phase induced the circadian rhythmicity of hepatic Fxr and Shp expressions. However, TRF in the rest phase altered the composition of the plasma BAs and the circadian oscillations of Cyp7a1, Cyp7b1, and Cyp27a1. These studies have not identified the potential role of FGF15/19 in the circadian regulation of BA metabolism in response to TRF signaling.

The modulation of circadian Fgf21 expression by TRF exhibits organ-specific effects in rodents. Most studies reported that TRF significantly increased Fgf21 expression. Oishi et al. found TRF in the rest phase induced the circadian oscillation of Fgf21 expression with significantly increased levels in epididymal WAT and a modest increase in the liver in mice (Oishi et al., 2011). Rats fed ad libitum presented the 24-hour circadian oscillation of hepatic Fgf21 expression, whereas TRF induced a phase shift of the circadian Fgf21 expression with a delayed peak in the dark phase and significantly increased serum FGF21 levels (García-Gaytán et al., 2020). Moreover, TRF induced resynchronization of FFAs and ketone bodies, coordinated with FGF21 to regulate lipid metabolism. These data demonstrate that alterations of Fgf21 expression in response to TRF reflect the circadian synchronization of whole-body metabolism. TRF alleviated microgravity-induced cardiac dysfunction in rats by improving the cardiac FGF21-FGFR1 signaling pathway (Wang et al., 2020). Liver-specific Fgf21 KO and cardiac-specific Fgfr1 KO mice abolished the protective effects of this pathway. In female mice, TRF restored glucose metabolism and improved reproductive performance in mice fed the high-fat diet (Hua et al., 2020). Similarly, these protective effects were blunted in liver-specific Fgf21 KO mice. These studies highlight the important role of hepatic FGF21 signaling in TRF-mediated beneficial effects. The molecular mechanisms underlying FGF21 response to TRF are not fully understood. The absence of FGF21 did not affect food-sustained circadian oscillators and rhythmic expression profiles of clock components in Fgf21 KO mice. Hence, dietary-mediated circadian oscillations may be regulated by multiple factors, of which FGF21 is one of the potential regulators. To date, there have been no studies identifying the effects of TRF on FGF21 levels in humans. Night-restricted feeding in diurnal growing pigs resulted in a significant reduction in the circadian level of serum FGF21, very low density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, resulting in abnormal lipid metabolism (Wang et al., 2021).

To date, no studies have reported the effects of TRF on FGF23. Restricted phosphate intake affects FGF23 levels and mineral homeostasis. Dietary phosphate restriction induced the upregulation of rhythmic transcriptions of CGs in response to hypophosphatemia in mice, thus causing the restoration of circadian patterns of serum mineral factors including PTH, FGF23, and phosphate (Noguchi et al., 2018). Restricted dietary phosphate caused the reduction of FGF23 levels, which may be beneficial for patients with late-stage CKD (Isakova et al., 2013). Kawai et al. found that the circadian profiles of skeletal Fgf23 expression may be predominantly dependent on the timing of dietary phosphate intake instead of the amount of ingested phosphate (Kawai et al., 2014). Hence, these findings emphasize the important role of feeding time in regulating the circadian rhythm of mineral metabolism, thus providing novel insight into treating bone and mineral diseases in a temporal manner.

However, the TRF regimen raised the question of whether TRF is applicable for various metabolic conditions. Hu et al. found that 16-hour fasting during the daytime for 4 weeks in childhood followed by ad libitum diet in adulthood caused irreversible detrimental effects on metabolic, developmental, and immune systems in mice (Hu et al., 2019). Further studies should be investigated to determine the role of TRF regimens in regulating whole-body homeostasis.

Chronotherapy

Chronotherapy refers to the adjustment of medication administration timing to optimize its pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety profile. By taking into account the circadian rhythms of the body when administering medications, it is possible to maximize their therapeutic benefits while minimizing potential adverse effects (Levi and Schibler, 2007). We summarize the key findings of chronotherapy for different drugs in clinical trials in Table 2. Blood pressure represents a well-recognized 24-hour circadian rhythm with a morning surge followed by decreased levels during the day and a nocturnal dipping in humans. However, absence of nocturnal dipping is more frequent in hypertensive patients and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events (Biaggioni, 2008). Recent studies have identified that nighttime administration of antihypertensive drugs improved overall circadian patterns of 24-hour blood pressure compared with morning administration (Bowles et al., 2018). Chronotherapeutic trials using methotrexate or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis have demonstrated that bedtime medication administration leads to improved rheumatoid arthritis symptoms (Cutolo et al., 2008; To et al., 2011; Buttgereit et al., 2015). Moreover, bedtime administration of glucocorticoids with release in the late night coordinated with nocturnal interleukin-6 increase decreased morning joint stiffness and pain (Cutolo et al., 2008; Buttgereit et al., 2015; Cutolo, 2016). Chronotherapy of anticancer drugs for patients with gastrointestinal cancer increased high-dose drug tolerance and drug efficacy and for colorectal cancer with liver metastases treated with complete surgical resection elevated 5-year survival (Giacchetti, 2002; Eriguchi et al., 2003). Hassan and Haefeli identified that optimizing drug administration timing increased clinical outcomes of some drugs in randomized controlled trials (Hassan and Haefeli, 2010). Kaur et al. indicated that some clinical trials supported the beneficial effects of chronotherapy for some commonly prescribed medicines via optimal circadian-based timing administration in Australia; however, circadian dosing information is often neglected in daily practice, even for drugs with unequivocal evidence of circadian variability (Kaur et al., 2016).

TABLE 2.

Summary of Chronotherapy Effects Regarding Different Drugs in Clinical Trials

| Drugs | Intervention | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antihypertension drugs | Evening administration | Controlled morning rise of high blood pressure and heart rate improved 24-h blood pressure profiles | Hermida et al., 2010, 2020; Bowles et al., 2018 |

| Teriparatide | Morning administration | Decreased bone collagen degradation, increased bone mineral density | Luchavova et al., 2011; Michalska et al., 2012 |

| Calcitonin | Evening administration | Decreased bone collagen degradation | Karsdal et al., 2008 |

| Methotrexate, NSAIDs | Bedtime administration | Improved symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis | To et al., 2011; Buttgereit et al., 2015; Cutolo, 2016 |

| Glucocorticoids | Bedtime administration with release in the late night | Decreased morning joint stiffness and pain | Cutolo et al., 2008; Buttgereit et al., 2015; Cutolo, 2016 |

| Cisplatin + 5-fluorouracil (combined with radiotherapy) | Cisplatin administration from 10:00 to 22:00 + 5-fluorouracil from 22:00 to 10:00 | Decreased adverse effects and increased treatment tolerance | Gou et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018b |

| Irinotecan | Morning administration for males and afternoon administration for females | Decreased adverse effects | Innominato et al., 2020 |

| Radiotherapy | 11:01 to 14:00 administration | Increased response rate in females | Chan et al., 2017 |

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Despite extensive research on chronotherapy, no studies to date have investigated the potential association between chronotherapy and metabolic diseases. An increased number of clinical trials are focusing on intervention strategies aimed at modulating FGF signaling to treat metabolic diseases. The therapeutical potential of endocrine FGF members has been tested in recent ongoing clinical trials, which provide novel strategies for treating metabolic diseases, mineral diseases, and cancers (Degirolamo et al., 2016). FGF19-related therapies have become promising strategies for the treatment of a variety of metabolic diseases associated with BA dysregulation. Several engineered FGF19 analogs have been evaluated in clinical trials in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (Harrison Hirschfield et al., 2019; et al., 2021; Sanyal et al., 2021). Strategies targeting modulating FGF19/FXR signaling, such as FXR agonists, assessed FGF19 levels as endpoints in clinical studies in patients with NASH, primary BA diarrhea or bowel syndrome (Rao et al., 2010; Walters et al., 2015; Sanyal et al., 2023). Inhibition of FGF19/FGFR4 signaling including genetic deletion and application of FGFR4 neutralizing antibody has been identified to prevent hepatocellular carcinoma development in preclinical animal models (Desnoyers et al., 2008; French et al., 2012). Moreover, an engineered FGF19 variant (M70) has been shown to retain the biologic activity in maintaining BA homeostasis but can prevent hepatocarcinogenesis in mouse models (Zhou et al., 2014). The effects of FGF21 on whole-body metabolism and its crucial regulatory role in BA homeostasis have endorsed FGF21 as potentials for treating obesity and type II diabetes. Pegbelfermin, an engineered PEGylated FGF21, improved metabolic parameters and fibrosis biomarkers in clinical trials in patients with obesity and type II diabetes (Charles et al., 2019). Recently, FGF21 and its analogs have been shown to present antisteatotic, anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects against NASH in murine and humans (Henriksson and Andersen, 2020). The development of FGF23 neutralizing antibodies has been the trend for FGF23-based therapies for hypophosphatemic diseases, CKD, hyperparathyroidism, and comorbidities of these diseases (Shalhoub et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2015; Imel et al., 2019). The neutralizing antibodies decrease FGF23 levels and block FGF23-targeted signaling, thus achieving phosphate, calcium, and vitamin D homeostasis. As circadian profiles of FGF levels are associated with energy metabolism, mineral homeostasis, and central oscillators, pharmacological treatment in metabolic diseases through timed administration of exogenous FGFs may provide new perspectives into maintaining metabolic homeostasis. Circadian synchronization of metabolic influxes, hormone secretion, and energy metabolism may induce beneficial effects on overall metabolic health. Ultimately, the goal of chronotherapy is to improve patient outcomes and quality of life by tailoring medication regimens to the individual's unique biologic rhythms.

Conclusion

The circadian regulation of endocrine FGF members is critically important in modulating whole-body energy metabolism among mediating intra- and interorgan signaling. Circadian disruption induced by environmental cues and genetic ablation is associated with metabolic dysfunction and disorders. Circadian oscillations of endocrine FGFs may serve as potential biomarkers for determining metabolic conditions. The timing of food intake is highlighted as a powerful environmental cue with the potential to restore the synchrony of circadian rhythms in metabolism. The therapeutical strategies targeted at drug administration timing may present a novel perspective for modulating the therapeutic regimens via maintaining the physiologic and behavioral activities under circadian control. Due to the increasingly extensive development of endocrine FGF-based therapies, more studies should be conducted to provide information on FGF signaling pathways to support the potential application of chrononutrition and chronotherapy to improve basic health and optimize current therapy regimens of metabolic diseases and mineral diseases.

Acknowledgments

Figures were created with BioRender.com.

Data Availability

The authors declare that there are no datasets generated or analyzed within the paper.

Abbreviations

- BA

bile acid

- BMAL1

brain and muscle Arnt-Like 1

- CCG

clock-controlled gene

- cFGF23

C-terminal fibroblast growth factor 23

- CG

clock gene

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CLOCK

circadian locomotor output cycles kaput

- CRY

cryptochrome

- CYP7A1

cholesterol-7α-hydroxylase/cytochrome P450 7A1

- DVC

dorsal vagal complex

- E4BP4

E4 promoter-binding protein 4

- FFA

free fatty acid

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR

fibroblast growth factor receptor

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- iFGF23

intact fibroblast growth factor 23

- KO

knockout

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- PER

period

- PPARα

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- REV-ERB

nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D members

- ROR

retinoic acid-related orphan receptor

- RORE

retinoic acid-related orphan receptor response element

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- SHP

small heterodimer partner

- TRF

time-restricted feeding

- WAT

white adipose tissue

Authorship Contributions

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Yang, Zarbl, Guo.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Center for Environmental Exposure and Diseases [Grant P30ES005022] (to H.Z.); National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Grants ES005022, ES007148, and ES029258] (to G.L.G.), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [Grant DK122725] (to G.L.G.), National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grants GM135258 and GM093854] (to G.L.G.); and the Department of Veteran Affairs [Grant BX002741] (to G.L.G.).

References

- Adamovich Y, Rousso-Noori L, Zwighaft Z, Neufeld-Cohen A, Golik M, Kraut-Cohen J, Wang M, Han X, Asher G (2014) Circadian clocks and feeding time regulate the oscillations and levels of hepatic triglycerides. Cell Metab 19:319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khaifi A, Straniero S, Voronova V, Chernikova D, Sokolov V, Kumar C, Angelin B, Rudling M (2018) Asynchronous rhythms of circulating conjugated and unconjugated bile acids in the modulation of human metabolism. J Intern Med 284:546–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allada R, Bass J (2021) Circadian mechanisms in medicine. N Engl J Med 384:550–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen B, Beck-Nielsen H, Højlund K (2011) Plasma FGF21 displays a circadian rhythm during a 72-h fast in healthy female volunteers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 75:514–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton SD, Lee SA, Donahoo WT, McLaren C, Manini T, Leeuwenburgh C, Pahor M (2019) The effects of time restricted feeding on overweight, older adults: a pilot study. Nutrients 11:1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badman MK, Pissios P, Kennedy AR, Koukos G, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E (2007) Hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by PPARalpha and is a key mediator of hepatic lipid metabolism in ketotic states. Cell Metab 5:426–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass J, Takahashi JS (2010) Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science 330:1349–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenken A, Mohammadi M (2009) The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8:235–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell-Pedersen D, Cassone VM, Earnest DJ, Golden SS, Hardin PE, Thomas TL, Zoran MJ (2005) Circadian rhythms from multiple oscillators: lessons from diverse organisms. Nat Rev Genet 6:544–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dov IZ, Galitzer H, Lavi-Moshayoff V, Goetz R, Kuro-o M, Mohammadi M, Sirkis R, Naveh-Many T, Silver J (2007) The parathyroid is a target organ for FGF23 in rats. J Clin Invest 117:4003–4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya N, Wiench M, Dumitrescu C, Connolly BM, Bugge TH, Patel HV, Gafni RI, Cherman N, Cho M, Hager GL, et al. (2012) Mechanism of FGF23 processing in fibrous dysplasia. J Bone Miner Res 27:1132–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biaggioni I (2008) . Circadian clocks, autonomic rhythms, and blood pressure dipping. Hypertension 52:797–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookout AL, de Groot MH, Owen BM, Lee S, Gautron L, Lawrence HL, Ding X, Elmquist JK, Takahashi JS, Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. (2013) FGF21 regulates metabolism and circadian behavior by acting on the nervous system. Nat Med 19:1147–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borck PC, Rickli S, Vettorazzi JF, Batista TM, Boschero AC, Vieira E, Carneiro EM (2021) Effect of nighttime light exposure on glucose metabolism in protein-restricted mice. J Endocrinol 252:143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles NP, Thosar SS, Herzig MX, Shea SA (2018) Correction to: chronotherapy for hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 21:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracci M, Ciarapica V, Copertaro A, Barbaresi M, Manzella N, Tomasetti M, Gaetani S, Monaco F, Amati M, Valentino M, et al. (2016) Peripheral skin temperature and circadian biological clock in shift nurses after a day off. Int J Mol Sci 17:623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs RM, Kalsbeek A (2001) Hypothalamic integration of central and peripheral clocks. Nat Rev Neurosci 2:521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttgereit F, Smolen JS, Coogan AN, Cajochen C (2015) Clocking in: chronobiology in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 11:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter TO, Insogna KL, Zhang JH, Ellis B, Nieman S, Simpson C, Olear E, Gundberg CM (2010) Circulating levels of soluble klotho and FGF23 in X-linked hypophosphatemia: circadian variance, effects of treatment, and relationship to parathyroid status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:E352–E357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaix A, Lin T, Le HD, Chang MW, Panda S (2019) Time-restricted feeding prevents obesity and metabolic syndrome in mice lacking a circadian clock. Cell Metab 29:303–319.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaix A, Zarrinpar A, Miu P, Panda S (2014) Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Cell Metab 20:991–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S, Zhang L, Rowbottom L, McDonald R, Bjarnason GA, Tsao M, Barnes E, Danjoux C, Popovic M, Lam H, et al. (2017) Effects of circadian rhythms and treatment times on the response of radiotherapy for painful bone metastases. Ann Palliat Med 6:14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapnik N, Genzer Y, Froy O (2017) Relationship between FGF21 and UCP1 levels under time-restricted feeding and high-fat diet. J Nutr Biochem 40:116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ED, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Pablo Frias J, Kundu S, Luo Y, Tirucherai GS, Christian R (2019) Pegbelfermin (BMS‐986036), PEGylated FGF21, in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes: results from a randomized phase 2 study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 27:41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che T, Yan C, Tian D, Zhang X, Liu X, Wu Z (2021) Time-restricted feeding improves blood glucose and insulin sensitivity in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Nutr Metab (Lond) 18:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Moschetta A, Bookout AL, Peng L, Umetani M, Holmstrom SR, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE, Richardson JA, Gerard RD, et al. (2006) Identification of a hormonal basis for gallbladder filling. Nat Med 12:1253–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulides C, Dyson P, Sprecher D, Tsintzas K, Karpe F (2009) Circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 is induced by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists but not ketosis in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:3594–3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Elitok S, Zeng S, Xiong Y, Hocher C-F, Hasan AA, Krämer BK, Hocher B (2021) C-terminal and intact FGF23 in kidney transplant recipients and their associations with overall graft survival. BMC Nephrol 22:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleator J, Abbott J, Judd P, Sutton C, Wilding JP (2012) Night eating syndrome: implications for severe obesity. Nutr Diabetes 2:e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornu M, Oppliger W, Albert V, Robitaille AM, Trapani F, Quagliata L, Fuhrer T, Sauer U, Terracciano L, Hall MN (2014) Hepatic mTORC1 controls locomotor activity, body temperature, and lipid metabolism through FGF21. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:11592–11599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutolo M (2016) Glucocorticoids and chronotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open 2:e000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutolo M, Straub RH, Buttgereit F (2008) Circadian rhythms of nocturnal hormones in rheumatoid arthritis: translation from bench to bedside. Ann Rheum Dis 67:905–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degirolamo C, Sabbà C, Moschetta A (2016) Therapeutic potential of the endocrine fibroblast growth factors FGF19, FGF21 and FGF23. Nat Rev Drug Discov 15:51–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet L, Thijs T, Mas R, Verbeke K, Depoortere I (2021) Time-restricted feeding in mice prevents the disruption of the peripheral circadian clocks and its metabolic impact during chronic jetlag. Nutrients 13:3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desnoyers LR, Pai R, Ferrando RE, Hötzel K, Le T, Ross J, Carano R, D’Souza A, Qing J, Mohtashemi I, et al. (2008) Targeting FGF19 inhibits tumor growth in colon cancer xenograft and FGF19 transgenic hepatocellular carcinoma models. Oncogene 27:85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Boney-Montoya J, Owen BM, Bookout AL, Coate KC, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA (2012) βKlotho is required for fibroblast growth factor 21 effects on growth and metabolism. Cell Metab 16:387–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JF, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA (1996) Phase-shifting human circadian rhythms: influence of sleep timing, social contact and light exposure. J Physiol 495:289–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggink HM, Oosterman JE, de Goede P, de Vries EM, Foppen E, Koehorst M, Groen AK, Boelen A, Romijn JA, la Fleur SE, et al. (2017) Complex interaction between circadian rhythm and diet on bile acid homeostasis in male rats. Chronobiol Int 34:1339–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli-Spichtig D, Zhang MYH, Perwad F (2018) Fibroblast growth factor 23 expression is increased in multiple organs in mice with folic acid-induced acute kidney injury. Front Physiol 9:1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egstrand S, Olgaard K, Lewin E (2020) Circadian rhythms of mineral metabolism in chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 29:367–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriguchi M, Levi F, Hisa T, Yanagie H, Nonaka Y, Takeda Y (2003) Chronotherapy for cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 57(Suppl 1):92s–95s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estall JL, Ruas JL, Choi CS, Laznik D, Badman M, Maratos-Flier E, Shulman GI, Spiegelman BM (2009) PGC-1α negatively regulates hepatic FGF21 expression by modulating the heme/Rev-Erb(α) axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:22510–22515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli PK, Lun M, Kim SM, Bredella MA, Wright S, Zhang Y, Lee H, Catana C, Klibanski A, Patwari P, et al. (2015) FGF21 and the late adaptive response to starvation in humans. J Clin Invest 125:4601–4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell JM, Chiang JY (2015) Circadian rhythms in liver metabolism and disease. Acta Pharm Sin B 5:113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feskanich D, Hankinson SE, Schernhammer ES (2009) Nightshift work and fracture risk: the Nurses’ Health Study. Osteoporos Int 20:537–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher FM, Kleiner S, Douris N, Fox EC, Mepani RJ, Verdeguer F, Wu J, Kharitonenkov A, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E, et al. (2012) FGF21 regulates PGC-1α and browning of white adipose tissues in adaptive thermogenesis. Genes Dev 26:271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonken LK, Workman JL, Walton JC, Weil ZM, Morris JS, Haim A, Nelson RJ (2010) Light at night increases body mass by shifting the time of food intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:18664–18669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo JP, Aronis KN, Chamberland JP, Mantzoros CS (2015) Lack of day/night variation in fibroblast growth factor 21 levels in young healthy men. Int J Obes 39:945–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo J-P, Aronis KN, Chamberland JP, Paruthi J, Moon H-S, Mantzoros CS (2013) Fibroblast growth factor 21 levels in young healthy females display day and night variations and are increased in response to short-term energy deprivation through a leptin-independent pathway. Diabetes Care 36:935–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DM, Lin BC, Wang M, Adams C, Shek T, Hötzel K, Bolon B, Ferrando R, Blackmore C, Schroeder K, et al. (2012) Targeting FGFR4 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma in preclinical mouse models. PLoS One 7:e36713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel K, Hoddy KK, Haggerty N, Song J, Kroeger CM, Trepanowski JF, Panda S, Varady KA (2018) Effects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: a pilot study. Nutr Healthy Aging 4:345–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gälman C, Lundåsen T, Kharitonenkov A, Bina HA, Eriksson M, Hafström I, Dahlin M, Åmark P, Angelin B, Rudling M (2008) The circulating metabolic regulator FGF21 is induced by prolonged fasting and PPARalpha activation in man. Cell Metab 8:169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Gaytán AC, Miranda-Anaya M, Turrubiate I, López-De Portugal L, Bocanegra-Botello GN, López-Islas A, Díaz-Muñoz M, Méndez I (2020) Synchronization of the circadian clock by time-restricted feeding with progressive increasing calorie intake. Resemblances and differences regarding a sustained hypocaloric restriction. Sci Rep 10:10036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattineni J, Bates C, Twombley K, Dwarakanath V, Robinson ML, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, Baum M (2009) FGF23 decreases renal NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c expression and induces hypophosphatemia in vivo predominantly via FGF receptor 1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297:F282–F291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacchetti S (2002) Chronotherapy of colorectal cancer. Chronobiol Int 19:207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh VH-H, Tong TY-Y, Lim C-L, Low EC-T, Lee LK-H (2000) Circadian disturbances after night-shift work onboard a naval ship. Mil Med 165:101–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou X-X, Jin F, Wu W-L, Long J-H, Li Y-Y, Gong X-Y, Chen G-Y, Chen X-X, Liu L-N (2018) Induction chronomodulated chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase II prospective randomized study. J Cancer Res Ther 14:1613–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan D, Zhao L, Chen D, Yu B, Yu J (2016) Regulation of fibroblast growth factor 15/19 and 21 on metabolism: in the fed or fasted state. J Transl Med 14:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Brewer JM, Champhekar A, Harris RB, Bittman EL (2005) Differential control of peripheral circadian rhythms by suprachiasmatic-dependent neural signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:3111–3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Zhang R, Jain R, Shi H, Zhang L, Zhou G, Sangwung P, Tugal D, Atkins GB, Prosdocimo DA, et al. (2015) Circadian control of bile acid synthesis by a KLF15-Fgf15 axis. Nat Commun 6:7231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara R, Wan K, Wakamatsu H, Aida R, Moriya T, Akiyama M, Shibata S (2001) Restricted feeding entrains liver clock without participation of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Cells 6:269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Waage S, Ursin H, Hansen ÅM, Bjorvatn B, Eriksen HR (2010) Cortisol, reaction time test and health among offshore shift workers. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35:1339–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SA, Neff G, Guy CD, Bashir MR, Paredes AH, Frias JP, Younes Z, Trotter JF, Gunn NT, Moussa SE (2021) Efficacy and safety of aldafermin, an engineered FGF19 analog, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 160: 219–231. e211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A, Haefeli WE (2010) Appropriateness of timing of drug administration in electronic prescriptions. Pharm World Sci 32:162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatori M, Vollmers C, Zarrinpar A, DiTacchio L, Bushong EA, Gill S, Leblanc M, Chaix A, Joens M, Fitzpatrick JA, et al. (2012) Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab 15:848–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson E, Andersen B (2020) FGF19 and FGF21 for the treatment of NASH—two sides of the same coin? Differential and overlapping effects of FGF19 and FGF21 from mice to human. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 11:601349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojón A, Fernández JR (2010) Influence of circadian time of hypertension treatment on cardiovascular risk: results of the MAPEC study. Chronobiol Int 27:1629–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermida RC, Crespo JJ, Domínguez-Sardiña M, Otero A, Moyá A, Ríos MT, Sineiro E, Castiñeira MC, Callejas PA, Pousa L, et al. ; Hygia Project Investigators (2020) Bedtime hypertension treatment improves cardiovascular risk reduction: the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial. Eur Heart J 41:4565–4576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfield GM, Chazouillères O, Drenth JP, Thorburn D, Harrison SA, Landis CS, Mayo MJ, Muir AJ, Trotter JF, Leeming DJ, et al. (2019) Effect of NGM282, an FGF19 analogue, in primary sclerosing cholangitis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial. J Hepatol 70:483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T, Wang C, Joshi S, O’Hara BF, Gong MC, Guo Z (2019) Active time-restricted feeding improved sleep-wake cycle in db/db mice. Front Neurosci 13:969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Mao Y, Xu G, Liao W, Ren J, Yang H, Yang J, Sun L, Chen H, Wang W, et al. (2019) Time-restricted feeding causes irreversible metabolic disorders and gut microbiota shift in pediatric mice. Pediatr Res 85:518–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]