Abstract

The replication of double-stranded plasmids containing a single N-2-acetylaminofluorene (AAF) adduct located in a short, heteroduplex sequence was analyzed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The strains used were proficient or deficient for the activity of DNA polymerase ζ (REV3 and rev3Δ, respectively) in a mismatch and nucleotide excision repair-defective background (msh2Δ rad10Δ). The plasmid design enabled the determination of the frequency with which translesion synthesis (TLS) and mechanisms avoiding the adduct by using the undamaged, complementary strand (damage avoidance mechanisms) are invoked to complete replication. To this end, a hybridization technique was implemented to probe plasmid DNA isolated from individual yeast transformants by using short, 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotides specific to each strand of the heteroduplex. In both the REV3 and rev3Δ strains, the two strands of an unmodified heteroduplex plasmid were replicated in ∼80% of the transformants, with the remaining 20% having possibly undergone prereplicative MSH2-independent mismatch repair. However, in the presence of the AAF adduct, TLS occurred in only 8% of the REV3 transformants, among which 97% was mostly error free and only 3% resulted in a mutation. All TLS observed in the REV3 strain was abolished in the rev3Δ mutant, providing for the first time in vivo biochemical evidence of a requirement for the Rev3 protein in TLS.

Organisms possess numerous and complex strategies that function with the common purpose of maintaining the integrity of their genetic material, including those devoted to the removal of damage caused by both endogenous and exogenous sources (i.e., excision repair pathways). However, conditions may arise in which the lesion burden is greater than the capacity of the repair process to remove all the lesions efficiently or the lesion itself may not be recognized as a substrate for any given repair pathway (7). Left unrepaired, damage can interfere with normal DNA metabolism, eventually resulting in mutations that, in higher eukaryotes, can contribute to the development of cancers.

Fortunately, cellular strategies exist to protect the genome from the potentially harmful effects of unrepaired damage. These pathways confer the ability to tolerate persistent damage, enabling replication recovery, continuation of the cell cycle, and, ultimately, survival under conditions of genotoxic stress. A subset of the tolerance mechanisms produces mutations which in unicellular organisms may confer an evolutionary advantage by permitting the organism to adapt to a harsh environment (7, 44).

Strategies for tolerating damage include the potentially mutagenic process of translesion synthesis (TLS), in which the information (or lack thereof) provided by the lesion in the damaged template strand is copied during replication. TLS may be continuous, in which the replication complex has or acquires the ability to continue replication directly across the damaged template, or discontinuous, involving the replicative filling-in of a gap left opposite the lesion by the dissociation and reinitiation of the replication complex downstream of the damage (7). Most, if not all, induced mutagenesis is thought to result from this process (7). Fortunately, mutations are rare events, suggesting that mutagenic TLS is a relatively minor component of damage tolerance; indeed, the majority of replication recovery seems to be carried out by largely error-free processes (7, 19, 49). Two essentially error-free mechanisms that share a fundamental feature, the use of the undamaged complementary sequence to accomplish replication, thereby avoiding the lesion (damage avoidance [DA]), have been proposed. Recombinational strand transfer of DNA from the undamaged duplex to the homologous strand of the damaged duplex is one proposed mechanism (41). A second process, referred to as copy choice or strand switch, postulates that the DNA polymerase (Pol) uses the newly synthesized daughter strand of the undamaged complementary sequence temporarily as a template to detour around the lesion (12). Following lesion clearance, the replicating Pol switches back to copying the original template strand. The details of both damage tolerance strategies (TLS and DA) are not well understood, particularly for eukaryotic cells.

In Escherichia coli, TLS is thought to be carried out by DNA Pol III together with at least three accessory proteins, the SOS-controlled umuDC gene products and the activated form of RecA (7, 49). However, TLS also has an umuDC-independent component (28, 31), pointing to the involvement of as-yet-undiscovered factors and underlining the complexity of this recovery strategy. The processes of DA are less well understood for this organism, but they may be the major means of replication recovery in the presence of a blocking lesion (19).

The budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is an excellent model with which to explore the damage tolerance mechanisms in higher eukaryotes, as the proteins involved in DNA metabolic activities are often very similar. The RAD6 pathway, comprised of components of the damage tolerance strategies, is responsible for a substantial fraction of this yeast’s resistance to DNA damage and for almost all induced mutagenesis (22). Less than half the genes implicated in the replication of damaged DNA have been cloned, and in only a few cases has it been possible to demonstrate the biochemical activity of the encoded proteins. However, certain protein functions are progressively being uncovered. For example, the multiple activities exhibited by the purified Rad6-Rad18 heterodimer suggest that this complex may recognize single-stranded DNA associated with replication forks stalled at damage sites (1). Once recruited, the complex may proceed to ubiquitinate components of the replication machinery, enabling replication recovery. Additionally, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (47), together with Pol δ (46), has been recently suggested to act in an error-free branch of the RAD6-dependent pathways.

An understanding of the potentially mutagenic mechanism of TLS is more advanced, owing mostly to in vitro primer extension studies using damaged templates and purified gene products. The Rev7p and the nonessential Rev3 DNA Pol associate to form a complex designated Pol ζ, whose sole function may be to replicate through damage sites (25). Pol ζ was able to perform TLS across a pyrimidine dimer-bearing primer template substrate (33). The REV1 gene product has been shown to insert cytosine preferentially across from a template abasic site, creating a lesion terminus that can be readily extended by Pol ζ (32). Interestingly, human Rev1p and Rev3p homologs may exist (25), rendering facets of yeast TLS potentially applicable to TLS operating in higher eukaryotes. However, in spite of the insights gathered from these in vitro studies, Rev protein-dependent TLS has not yet been demonstrated in vivo.

The current investigation was undertaken in an attempt to determine the frequencies with which the two major damage tolerance strategies (TLS and DA) are used in a eukaryotic cell faced with the problem of having to replicate a lesion-bearing, double-stranded DNA molecule. Replication of unmodified and heteroduplex plasmids carrying a single N-2-acetylaminofluorene (AAF) adduct situated at the third guanine of the sequence 5′ GGGAAF 3′ was examined in REV3 and rev3 strains deficient in both nucleotide excision (rad10Δ; NER−) and mismatch (msh2Δ) repair, respectively. Once the mechanisms used to complete damaged-plasmid replication were determined, the proposed role of the Rev3 component of Pol ζ in in vivo TLS was investigated. We present biochemical evidence of what appears to be an absolute requirement for Rev3p activity in TLS of the strong replication-blocking AAF adduct in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and media.

Yeast strains are derived from FL200 strains MATα ura3Δ trp1-4 leu2-1 (40). Both the REV3 and rev3Δ strains were in a rad10Δ msh2Δ background to avoid repair of the AAF adduct (48) and the 4-bp sequence heterology (36), respectively. All strains were constructed by the one-step gene disruption method (39). The rad10::LEU2 deletion was made by cloning the BamHI-HindIII LEU2 gene fragment of pFL33 (constructed by A. Bresson-Roy) into the XbaI site of the SalI-EcoRV RAD10 fragment (from pTB215; kindly provided by L. Prakash) previously cloned into the EcoRI site of plasmid pBR322. Inactivation of the MSH2 gene was accomplished by transforming rad10::LEU2 cells with the 9.5-kb SpeI fragment containing msh2::Tn10LUK obtained from restriction enzyme digestion of pII-2-Tn10LUK7-7 (generously provided by R. Kolodner). The rev3Δ strain was obtained by electroporating rad10::LEU2 msh2::Tn10LUK cells with the KpnI restriction fragment of the vector pDG347 (a generous gift from R. D. Gietz) containing the rev3::hisG-URA3-hisG cassette. Chromosomal integration and gene inactivation were confirmed by spore segregation analysis, mutant phenotype characterization, and Southern blot analysis (data not shown).

Yeast cells were grown either in complete medium (SC [glucose]) or in single-omission medium lacking the amino acid enabling transformant selection (SC lacking tryptophan [SC−Trp]) (43). Cells were transformed by electroporation (Bio-Rad gene pulser) (as previously described [40]) and incubated for at least 30 min at 30°C prior to plating. Small quantities (≤20 ng) of plasmid were used to transform yeast in order to minimize cotransformation, which was determined to be <10% (data not shown).

Bacterial strains and media.

The E. coli strains used were either TB1 (F− araΔ[lac-proAB] rpsL φ80[lacΔ(lacZ)M15] thi hsdR or XL1-Blue [F′::Tn10 proA+ B+ lacIq Δ(lacZ)M15/recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac] (42). Plasmids isolated from yeast for further analysis in E. coli (13) (see below) were transformed by electroporation into the above strains with the Bio-Rad gene pulser. Transformants were plated onto Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml (for transformant selection) as well as isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (X-Gal) to detect Lac+ colonies indicative of a −1G frameshift mutation having occurred in the sequence 5′ GGGAAF 3′ during plasmid replication in yeast (described in reference 19).

Plasmids.

The E. coli-S. cerevisiae shuttle vector pKBL10 was derived from pUC8. The HpaI-NdeI fragment of the 2μm plasmid digested from plasmid pFL45L (6), containing both the replication origin (ARS consensus sequence) and REP3 sequences, was cloned into the NdeI site of pUC8. The yeast TRP1 selective marker (Klenow fragment-filled BglII fragment from pFL39 [6]) was introduced into the Klenow fragment-filled AflIII site of pUC8. The pKBL(Helper), pKBL(3G), and pKBL(3G+3) parental plasmids were made by replacing the EcoRI-HindIII fragment of pKBL10 with duplex oligonucleotides containing the helper, 3G, or 3G+3 sequences, respectively (Fig. 1A).

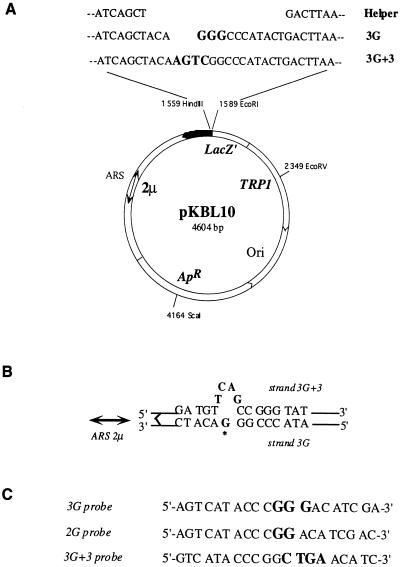

FIG. 1.

Vector design and hybridization strategy used in SSA. (A) Parental plasmids used to construct monomodified heteroduplexes and as hybridization controls. (B) Location of the strand marker with respect to the AAF adduct (asterisk). (C) Oligonucleotide probes to analyze strand segregation (3G and 3G+3) and −1G mutagenesis (2G).

Construction of heteroduplexes containing a single AAF adduct.

The strategy used to construct plasmids containing a single AAF adduct on the 3′ guanine of the sequence 5′ GGG 3′, itself located within a sequence heterology, involved the formation of gapped-duplex molecules described previously (19). The only modification was that the resulting adduct-containing heteroduplex plasmids were treated with Plasmid-Safe ATP-dependent DNase (Epicentre Technologies) after recovery from CsCl gradients in order to eliminate contaminating linear, double-stranded, homoduplex DNA which can transform yeast, albeit with a lower efficiency than that of closed, circular molecules (4, 39). Potential contamination by undigested pKBL(Helper) plasmids was minimized by HincII digestion prior to DNase treatment.

Strand segregation analysis (SSA).

The following technique enables sensitive and reproducible detection of the hybridization between a short, 5′-32P-labeled oligonucleotide and target plasmid sequences isolated from yeast transformants. Individual colonies issued from the transformation with heteroduplex constructions were picked up from SC−Trp plates and subsequently grown for approximately 24 h in 150 μl of SC−Trp in 96-well microtitration plates covered with sterile adhesive tape. Prior to lysis, cells were replica plated with a 48-prong manual replicator onto SC−Trp master plates so that plasmids having undergone TLS could be isolated (13) and transformed into E. coli for mutational analysis. The culture dishes were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 to 10 min in a Jouan GR2000S centrifuge to pellet the cells. Culture medium was aspirated off prior to spheroplast production to prevent inhibition of zymolyase activity. Spheroplasts were generated by enzymatic digestion for >30 min at 37°C by resuspending the above cell pellets in 100 μl of a digestion buffer containing 1 M sorbitol, 100 mM Na citrate, 50 mM EDTA, 14 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mg of Zymolyase 100T (Seikaguku) per ml. Spheroplast lysis was performed in the culture plaques by first adding, to the 100-μl spheroplast mixture, a 2× solution yielding a final concentration of 400 mM NaOH and 20 mM EDTA; this was followed by heating for approximately 3 min at 100°C. A microfiltration slot blot apparatus (Bio-Dot; Bio-Rad) was used to isolate total DNA (genomic and plasmid) onto a nylon membrane (Dupont/NEN) under vacuum pressure. The DNA was fixed to the filters with a solution of 400 mM NaOH, after which the membranes were briefly rinsed in 2× SSC. Hybridizations were performed according to the membrane manufacturer’s instructions (Dupont) with 20-mer oligonucleotide probes 3G (specific for the lesion-containing strand) and 3G+3 (specific for the strand marker) (Fig. 1C) at a hybridization temperature of 60°C. Dehybridization was done by placing the membranes in a boiling solution of 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 5 to 10 min followed by cooling them to room temperature. Both hybridization patterns and dehybridization efficiency were evaluated with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager. Hybridization signals of the negative controls (i.e., cells transformed with 3G+3 parental plasmids for 3G hybridization and vice versa for 3G+3 hybridization) were quantified by using the Image Quant function of Molecular Dynamics. The average of these measurements and its variance were calculated. All hybridization signals greater than the average negative control value plus two times the variance were considered positive. SSAs were systematically performed on clones arising from a minimum of four independent transformations per plasmid for each yeast strain.

Mutational analysis.

An initial screen for the −1G mutation in yeast was undertaken by hybridizing filters having previously undergone SSA (see above) with the 2G mutant-specific probe (Fig. 1C) at 62°C. A secondary analysis consisted of transforming E. coli with plasmids recovered from all yeast clones (grown on SC−Trp replica plates) having responded positively to both or either of the 3G and 2G probes. Sequence analysis (42) was performed on approximately 10 blue (mutant) and 10 white (nonmutant) bacterial colonies in order both to characterize the mutation and to confirm SSA in yeast, respectively.

RESULTS

SSA.

The present analysis in yeast cells was undertaken in a manner similar to that reported previously for E. coli (19) and is based on the following strategy: under normal circumstances, a single round of replication on a double-stranded DNA molecule yields two daughter molecules containing the genetic information derived from each original strand of the parent duplex. If the parent is a homoduplex, the daughters will be identical to each other and to the parent. However, if the parent molecule is a heteroduplex, the resulting progeny molecules will contain the genetic information of each original strand and will no longer be similar to each other nor to the original heteroduplex. This principle was used to study the damage tolerance strategies proposed to function in a eukaryote system when replication is forced to occur on a damaged DNA template. To this end, plasmids which contained, in the complementary strand directly opposite the adduct site, four extrahelical bases were constructed (Fig. 1B). Short 5′-32P-labeled oligonucleotides specific to each strand of the original, monomodified heteroduplex (probes 3G and 3G+3 [Fig. 1C]) were used to probe the progeny plasmids resulting from its replication. With this approach, the fate of each strand of a modified and unmodified heteroduplex could be monitored at the level of the strand marker after replication in individual yeast colonies. This enabled the determination of frequencies with which TLS and DA are used to complete replication of a bulky lesion-containing plasmid.

Replication of the unmodified heteroduplex vector.

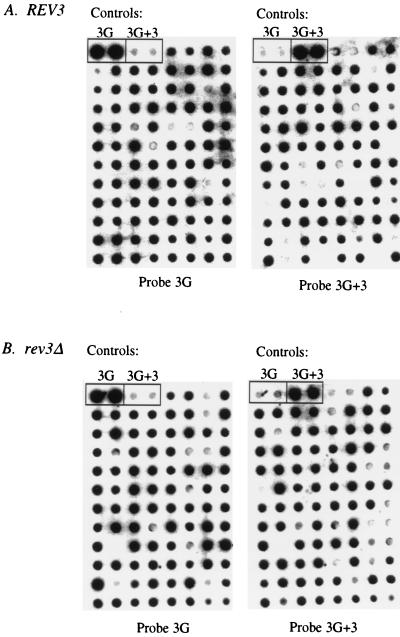

SSA was initially carried out on the REV3 and rev3Δ strains transformed with unmodified heteroduplex vectors as a control to compare with replication of the lesion-containing vector. Neither genomic DNA nor the endogenous 2μm plasmid interfered with hybridization analysis, as untransformed cells subjected to SSA did not hybridize with either the 3G or the 3G+3 probe (data not shown). The results are summarized in Table 1, and an example hybridization analysis performed on one filter for each strain is shown in Fig. 2. In both the REV3 and rev3Δ strains, an average of 80% of the transformants hybridized with both the 3G and 3G+3 probes (mixed colonies [Table 1]), indicating that both strands of the original heteroduplex molecule had been replicated to approximately the same extent, confirming the nonessential role of Rev3p in plasmid replication (37, 38). Of the remaining 20%, approximately half hybridized with only the 3G or the 3G+3 probe, respectively (Table 1) (3G and 3G+3 pure colonies). The presence of only one strand of the original heteroduplex in these clones could reflect prereplicative MSH2-independent mismatch repair. An activity that binds to heteroduplexes containing four to nine extra bases has been previously observed in cellular extracts prepared from yeast containing a mutation in the MSH2 gene (29). However, it is also possible that these clones arise from the preferential replication of one strand relative to the other. Regardless of their origin, the activity giving rise to the pure colonies was not dependent on functional Rev3p, as their total proportion (i.e., pure versus mixed) remained essentially the same in both strains (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

SSA of the unmodified heteroduplex plasmid in REV3 and rev3Δ strainsa

| Strain | % Mixedb | % 3G pure | % 3G+3 pure |

|---|---|---|---|

| REV3 | 78 (458/589) | 8 (50/589) | 14 (81/589) |

| rev3Δ | 82 (499/607) | 10 (59/607) | 8 (49/607) |

The percentages are calculated by dividing the number of clones hybridizing with a given probe by the total number of clones analyzed (in parentheses).

Mixed colonies are those responding positively to both the 3G and 3G+3 probes.

FIG. 2.

SSA of strains transformed with the nonmodified heteroduplex plasmids. (A) Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager image of an analysis performed on REV3 clones. At left is the hybridization pattern observed with the 3G probe. To the right is the same filter hybridized with the 3G+3-specific probe. (B) The same analysis as shown in panel A for the rev3Δ strain. Hybridization controls (parental plasmids 3G and 3G+3 [Fig. 1A]) are indicated at the top of each filter (rectangles).

Replication of the AAF-modified plasmid.

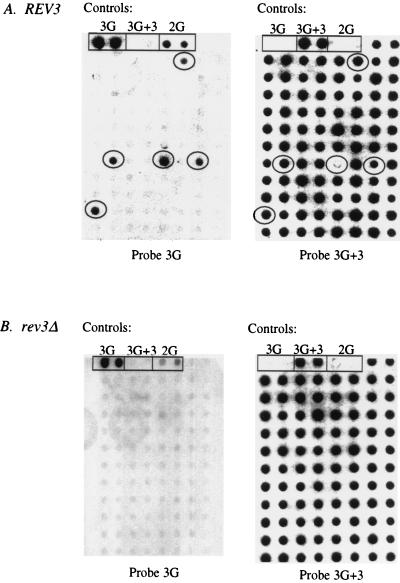

AAF-monomodified heteroduplex plasmids were transformed into the above yeast strains and analyzed as described for the unmodified vector. AAF was the lesion of choice, as the chemical adducts it forms in DNA are stable and well characterized and have been shown to be strong blocks to replication (5, 14, 19, 27, 31, 45). Moreover, AAF-monomodified plasmids have been successfully used as tools to investigate damage tolerance strategies in E. coli (19, 31). The total number of transformants obtained with both the unmodified and the modified plasmid preparations was the same for both strains (data not shown), thereby eliminating a possible bias in the observations resulting from adduct toxicity. As can be seen in Table 2 and Fig. 3A, the presence of a single AAF lesion had a marked effect on plasmid replication in the REV3 strain (compare with Table 1 and Fig. 2A). An average of 92% of the transformant colonies contained only the 3G+3 strand (versus 14% observed with the unmodified plasmid [Table 1]), while the proportion of colonies responding positively to both probes was reduced from 78% in the absence of the lesion to 6% in its presence. Interestingly, 2% of the colonies appear to be 3G pure (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

SSA of REV3 and rev3Δ strains transformed with monomodified heteroduplexesa

| Strain | TLSb

|

DAc (% 3G+3 pure) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Mixed | % 3G pure | ||

| REV3 | 6 (97/1,558) | 2 (25/1,558) | 92 (1,436/1,558) |

| rev3Δ | <0.1 (0/988) | <0.1 (0/988) | 100 (988/988) |

The percentages are calculated by dividing the number of clones hybridizing with a given probe by the total number of clones analyzed (in parentheses).

Mixed clones are those that hybridize with both the 3G and 3G+3 probes.

3G+3 pure clones represent clones in which replication was completed by either a DA or a strand loss mechanism.

FIG. 3.

SSA of clones transformed with monomodified heteroduplex plasmids. (A) Example filter of REV3 clones analyzed, at left, with the 3G probe specific to the lesion-containing strand and, at right, with the 3G+3 probe. (B) As shown for panel A, with the rev3Δ strain. Circles represent those clones in which TLS has occurred. Controls are as described for Fig. 2. Note that the 2G control cross-hybridizes with the 3G probe.

Fidelity of TLS.

The dG–C8–AAF located at the 3′ end of a run of three consecutive guanines (5′ GGGAAF 3′) has been previously characterized as inducing −1G frameshift mutations in both E. coli (21) and yeast (4, 40) at high frequencies. However, in this particular experimental system, phenotypic detection of mutagenic events arising in yeast transformants was not possible. An initial hybridization screen of yeast filters previously subjected to SSA was performed with the −1 frameshift mutation-specific 2G probe, but cross-hybridization of this probe with the wild-type 3G sequence rendered positive mutation identification uncertain (data not shown). However, the guanine run is located in the lacZ′ gene in a +1 reading frame, enabling easy phenotypic detection of −1 frameshift events in E. coli via the so-called lacZαω complementation assay. Since mutations are thought to arise during TLS (21), all plasmids hybridizing with the 3G probe (mixed and 3G pure [Table 2]), regardless of their hybridization response to the mutant probe, were subjected to further analysis in E. coli (see Materials and Methods). Of the TLS events observed in the REV3 strain (122 of 1,558, or 8%), only 3% were mutagenic (4 of 122) (Fig. 4). Among the four mutants recovered, three were the expected −1G; the remaining mutant was an untargeted −1C (previously observed in this sequence context in E. coli [21] and yeast [4]). Interestingly, the four mutants recovered were identified in SSA as being mixed (3G and 3G+3 positive [Fig. 3]) and gave variable but inconclusive hybridization signals with the 2G mutation-specific probe (data not shown). Secondary transformation of E. coli with plasmids isolated from these mutants gave rise to transformant populations in which the total number of blue (mutant) colonies was different for each yeast clone but was always smaller than the white (nonmutant) population, consisting of 3G and 3G+3 homoduplex plasmids (confirmed by sequencing analysis [data not shown]).

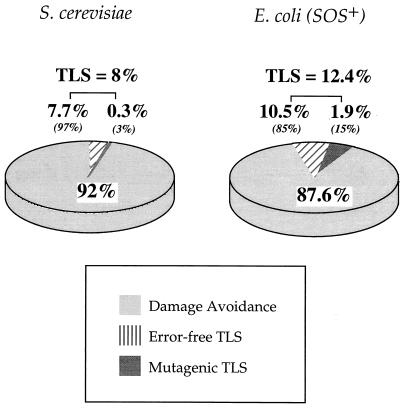

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the proportions of DA and error-free and mutagenic TLS observed in yeast (rad10Δ msh2Δ) and SOS-induced E. coli (uvrA mutS) strains transformed with the AAF-modified heteroduplex vector. Results for E. coli are taken from reference 19. The percentages represent the contribution of each strategy to the total events detected with SSA. DA includes all processes giving rise to 3G+3 pure clones, including lesion-induced strand loss (see text for details).

Dependence of TLS on the Rev3 Pol component of Pol ζ.

The possible involvement of the Rev3 Pol in the TLS observed in the REV3 strain was examined by performing SSA on the rev3Δ mutant strain transformed with the AAF-modified heteroduplex plasmid. The results show that, in the absence of functional Rev3 protein, all TLS, indicated by mixed and 3G pure clones, is abolished (Table 2 and Fig. 3B). Completion of plasmid replication in the rev3Δ mutant occurred 100% of the time by a mechanism employing, at least locally at the adduct site, the complementary, lesion-free strand. As the unmodified plasmid is replicated in a similar manner in both REV3 and rev3Δ strains (Table 1), these results are not due to a general Rev3-dependent defect in plasmid replication.

DISCUSSION

TLS of the AAF-modified sequence (5′ GGGAAF 3′) is infrequent and relatively error free.

Replication of the AAF-monomodified plasmid in the REV3 strain was completed by a mechanism using, at least locally at the lesion site, the information provided by the undamaged strand in more than 90% of the clones analyzed (Table 2; Fig. 3A). Mechanisms avoiding direct copying of unrepaired damage include recombinational daughter strand gap filling (41) and Pol strand switch (12). Either one of these mechanisms could conceivably give rise to the large proportion of 3G+3 pure clones observed in both REV3 and rev3Δ strains. However, an alternative explanation relevant to the plasmid situation that could equally account for the high proportion of 3G+3 pure clones might be the preferential replication and concomitant amplification of the undamaged strand. Lesion-induced strand loss was proposed to explain the prevalence of the undamaged strand in transformants arising from the replication of vectors containing either AAF adducts (20, 45) or a single cis-syn cyclobutane thymine dimer (15) in E. coli. It is not possible, with the present constructs, to distinguish between true DA events and lesion-induced strand loss.

Of the 8% TLS events detected, 6% were mixed clones (positive for 3G and 3G+3) and 2% were identified as 3G pure colonies (Table 2). Error-free, replicative filling-in of a gap created opposite the adduct during repair of the strand marker could give rise to these 3G pure clones. This repair might be associated with the MSH2-independent heteroduplex binding activity previously observed (29) and proposed, in this study, as one possible origin of the pure clones observed after replication of the unmodified heteroduplex plasmid (3G and 3G+3 pure [Table 1]). However, we cannot confirm an association between this binding activity and a repair process acting at the lesion heteroduplex site. Alternatively, these clones could arise from the preferential replication of the strand bearing the monomodified sequence, but this seems unlikely. What is unequivocal is that these clones result from error-free TLS; whether this TLS is coincident with gap filling (associated with either repair or discontinuous replication) or with continuous synthesis is speculative.

The TLS detected in yeast at the sequence 5′ GGGAAF 3′ (8%) is comparable to that observed previously at the identical site in SOS-induced NER− mismatch repair-deficient (uvrA mutS) E. coli strains (12.4%); conversely, the frequency of mutagenic TLS in yeast is about five times lower (3 versus 15%) (19) (Fig. 4). The structure of the adduct-modified template largely determines the kinds of mutations induced. However, both the efficiency with which TLS is performed and the relative proportions of error-free TLS and of the different mutagenic TLS events depend not only on the damaged template structure but also on the intrinsic properties of the replication proteins involved (24). Protein-dependent quantitative differences in the extent of TLS and in the mutagenic specificity have been observed in studies in which NER-deficient yeast and bacteria were transformed with vectors bearing either a defined and specifically located UV photoproduct (2, 3, 8, 9) or an abasic site (10, 23). In general, all lesions examined so far were bypassed in yeast with a relatively lower error rate per bypass event compared to that of the SOS-induced E. coli strain. As the predominant mutation recovered in this study is a −1G frameshift, the mechanism responsible is likely similar to that proposed for E. coli: primer template slippage subsequent to insertion of a cytosine opposite the dG-AAF, followed by elongation, from the slipped mutagenic intermediate, of the postlesion primer terminus (21, 31). It should be stressed that the AAF adduct does not change the coding properties of the guanine due to the fact that the adduction site (i.e., the C8 position) is not involved in the coding portion of the base (27). Unlike mutagens that induce base substitutions, AAF exerts its mutagenic potential by promoting a miselongation event rather than a misinsertion event. The lower frequency of mutagenic TLS may suggest that either the formation of or the elongation from the slipped mutagenic intermediate may be somewhat more difficult for the yeast replicative machinery than for that of E. coli.

Interestingly, the fact that the four yeast mutants were mixed colonies (i.e., hybridizing with both the 3G and 3G+3 probes) indicates that the mutations arose after the first round of plasmid replication. Persistent damage has previously been documented to be a continuing source of mutations (18), as well as of sister chromatid recombination (16) in yeast during subsequent rounds of replication. This contrasts with E. coli, in which AAF-induced mutagenesis appeared to take place during the first round of replication (19).

Dependence of TLS on Rev3p.

The hypomutator phenotype exhibited by rev3 mutants with respect to both spontaneous (37, 38) and certain agent-induced (26, 30, 34, 35) mutagenesis, together with it being a nonessential, distant member of the δ family of DNA Pols (30), suggested that yeast, unlike E. coli, required a specialized Pol to replicate across damage sites. This has been substantiated with the demonstration of Rev3p-dependent TLS in vitro (32, 33). In this study, elimination of the Rev3p component of Pol ζ abolished all TLS (Table 2; Fig. 3B), identifying Rev3p, and probably by extension Pol ζ, as being required for the TLS observed at the dG-AAF located in the sequence 5′ GGGAAF 3′ on a double-stranded plasmid.

With respect to the 3G pure clones observed in the REV3 strain, if a gap-filling process did indeed produce these clones, this could suggest that Rev3p may have a general role in gap filling across lesion sites independent of the process creating the gap. Curiously, the possible association of an essentially nonmutagenic repair activity (i.e., mismatch repair) with a potentially mutagenic process (TLS of lesions located in strand gaps) is reminiscent of the theories of misrepair in yeast in which a role for repair processes in mutation fixation was proposed (reference 17 and references therein).

Despite the unambiguous demonstration of a requirement for Rev3p in TLS in this study, many unknowns remain concerning the individual steps, catalytic activities, and protein interactions required to carry out replication on a variety of lesions. Furthermore, TLS mechanisms operating on a plasmid may be different from those functioning at the chromosome. Moreover, depending upon the replication-hindering capacity of lesions, a Pol(s) other than Pol ζ may be capable of replicating damaged templates in yeast. A Pol δ temperature-sensitive mutant (pol3-13) was shown to be defective in UV-induced chromosomal mutagenesis and to behave epistatically with a rev3 mutant (11). These findings led the authors to propose that Pol δ may have a global role in UV-induced mutagenesis (i.e., TLS). What this study may indicate is that both Pols (Pol ζ and δ) are necessary to carry out the whole process of TLS in yeast. Pol ζ exhibits poor processivity on DNA templates in vitro (33). It could be imagined that Pol ζ activity (i.e., incorporation opposite the lesion, accompanied or not by a limited amount of elongation from the inserted nucleotide) may be required only at the lesion site itself, creating a 3′ terminus from which Pol δ could elongate in a highly processive manner.

Thus, TLS in yeast and, by extension, in higher eukaryotes is a complex process, likely requiring the participation of several protein activities. For example, the cytidyl transferase activity of Rev1p may be required to replicate past abasic sites, while another general function of Rev1p is likely necessary for TLS of UV lesions (32). Together with Pol ζ and δ, Rev1p and probably other proteins may function as part of a TLS complex capable of replicating past a variety of DNA lesions. The identification of the proteins and their respective function(s) in the individual steps of TLS awaits further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely thank I. Pinet for superb technical assistance and O. Becherel, M. Bichara, and A. Aboussekhra for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions.

K.B. was supported by a Bourse du Gouvernement Français au Canada (BDF).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailly V, Lauders S, Prakash S, Prakash L. Yeast DNA repair proteins Rad6 and Rad18 form a heterodimer that has ubiquitin conjugating, DNA binding, and ATP hydrolytic activities. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23360–23365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banerjee S K, Borden A, Christensen R B, LeClerc J E, Lawrence C W. SOS-dependent replication past a single trans-syn T-T cyclobutane dimer gives a different mutation spectrum and increased error rate compared with replication past this lesion in uninduced cells. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2105–2112. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.2105-2112.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee S K, Christensen R B, Lawrence C W, LeClerc J E. Frequency and spectrum of mutations produced by a single cis-syn thymine-thymine cyclobutane dimer in a single-stranded vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8141–8145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baynton, K., and A. Bresson-Roy. Unpublished data.

- 5.Belguise-Valladier P, Maki H, Sekiguchi M, Fuchs R P P. Effect of single DNA lesions on in vitro replication with DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. Comparison with other polymerases. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:151–164. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonneaud N, Ozier-Kalogeropoulous O, Li G Y, Labouesse M, Minvielle-Sebastia L, Lacroute F. A family of low and high copy replicative, integrative and single-stranded S. cerevisiae/E. coli shuttle vectors. Yeast. 1991;7:609–615. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedberg E C, Walker G C, Siede W. DNA repair and mutagenesis. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibbs P E M, Borden A, Lawrence C W. The T-T pyrimidine (6-4) pyrimidone UV photoproduct is much less mutagenic in yeast than in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1919–1922. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.11.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbs P E M, Kilbey B J, Banerjee S K, Lawrence C W. The frequency and accuracy of replication past a thymine-thymine cyclobutane dimer are very different in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2607–2612. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2607-2612.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibbs P E M, Lawrence C W. Novel mutagenic properties of abasic sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Biol. 1995;251:229–236. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giot L, Chanet R, Simon M, Facca C, Faye G. Involvement of the yeast polymerase δ in DNA repair. Genetics. 1997;146:1239–1251. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.4.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins N P, Kato K, Strauss B. A model for replication repair in mammalian cells. J Mol Biol. 1976;101:417–425. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman C S, Winston F. A ten minute preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;57:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann J S, Pillaire M J, Lesca C, Burnouf D, Fuchs R P P, Defais M, Villani G. Fork-like DNA templates support bypass replication of lesions that block DNA synthesis on single-stranded templates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13766–13769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang N, Taylor J S. In vivo evidence that UV-induced C→T mutations at dipyrimidine sites could result from the replicative bypass of cis-syn cyclobutane dimers or their deamination products. Biochemistry. 1993;32:472–481. doi: 10.1021/bi00053a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kadyk L C, Hartwell L H. Replication-dependent sister chromatid recombination in rad1 mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1993;133:469–487. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.3.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilbey B J. Mutagenesis in yeast—misreplication or misrepair? Mol Gen Genet. 1984;197:519–521. doi: 10.1007/BF00329955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilbey B J, James A P. The mutagenic potential of unexcised pyrimidine dimers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae7RAD1-1. Mutat Res. 1979;60:163–171. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(79)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koffel-Schwartz N, Coin F, Veaute X, Fuchs R P P. Cellular strategies for accommodating replication-hindering adducts in DNA: control by the SOS response in E. coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7805–7810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koffel-Schwartz N, Maenhaut-Michel G, Fuchs R P P. Specific strand loss in N-2-acetylaminofluorene-modified DNA. J Mol Biol. 1987;193:651–659. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert I B, Napolitano R L, Fuchs R P P. Carcinogen-induced frameshift mutagenesis in repetitive sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1310–1314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence C. The RAD6 DNA repair pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: what does it do, and how does it do it? Bioessays. 1994;16:253–258. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrence C W. Mutation frequency and spectrum resulting from a single abasic site in a single-stranded vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2153–2157. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.8.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence C W, Gibbs P E M, Borden A, Horsfall M J, Kilbey B J. Mutagenesis induced by single UV photoproducts in E. coli and yeast. Mutat Res. 1993;299:157–163. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(93)90093-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence C W, Hinkle D C. DNA polymerase ζ and the control of DNA damage induced mutagenesis in eukaryotes. Cancer Surv. 1996;28:21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemontt J F. Mutants of yeast defective in mutation induced by ultraviolet light. Genetics. 1971;68:21–33. doi: 10.1093/genetics/68.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsley J E, Fuchs R P P. Use of single-turnover kinetics to study bulky adduct bypass by T7 DNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:764–772. doi: 10.1021/bi00169a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maenhaut-Michel G, Janel-Bintz R, Fuchs R P P. A umuDC-independent SOS pathway for frameshift mutagenesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;235:373–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00279383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miret J J, Parker B O, Lahue R S. Recognition of DNA insertion/deletion mismatches by an activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:721–729. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.4.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison A, Christensen R B, Alley J, Beck A K, Bernstine E G, Lemontt J F, Lawrence C W. REV3, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene whose function is required for induced mutagenesis, is predicted to encode a nonessential DNA polymerase. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5659–5667. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5659-5667.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Napolitano R L, Lambert I, Fuchs R P P. SOS factors involved in translesion synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5733–5738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson J R, Lawrence C W, Hinkle D C. Deoxycytidyl transferase activity of yeast REV1 protein. Nature. 1996;382:729–731. doi: 10.1038/382729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson J R, Lawrence C W, Hinkle D C. Thymine-thymine dimer bypass by yeast DNA polymerase ζ. Science. 1996;272:1646–1649. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prakash L. Effect of genes controlling radiation sensitivity on chemically induced mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1976;83:285–301. doi: 10.1093/genetics/83.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prakash L. Characterization of postreplication repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and effects of rad6, rad18, rev3 and rad52 mutations. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;25:33–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00352525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reenan R A G, Kolodner R D. Characterization of insertion mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH1 and MSH2 genes: evidence for separate mitochondrial and nuclear functions. Genetics. 1992;132:975–985. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.4.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roche H, Gietz R D, Kunz B A. Specificity of the yeast rev3Δ antimutator and REV3 dependency of the mutator resulting from a defect (rad1Δ) in nucleotide excision repair. Genetics. 1994;137:637–646. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.3.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roche H, Gietz R D, Kunz B A. Specificities of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae rad6, rad18 and rad52 mutators exhibit different degrees of dependence on the REV3 gene product, a putative nonessential DNA polymerase. Genetics. 1995;140:443–456. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothstein R. Targeting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:281–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy A, Fuchs R P P. Mutational spectrum induced in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by the carcinogen N-2-acetylaminofluorene. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:69–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00279752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rupp W D, Howard-Flanders P. Discontinuities in the DNA synthesized in an excision-defective strain of Escherichia coli following ultraviolet irradiation. J Mol Biol. 1968;31:291–304. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taddei F, Matic I, Radman M. Mutagenèse et adaptation. Méd Sci. 1997;13:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas D C, Veaute X, Kunkel T A, Fuchs R P P. Mutagenic replication in human cell extracts of DNA containing site-specific N-2-acetylaminofluorene adducts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7752–7756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torres-Ramos C A, Prakash S, Prakash L. Requirement of yeast DNA polymerase δ in post-replication repair of UV-damaged DNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25445–25448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torres-Ramos C A, Yoder B L, Burgers P M J, Prakash S, Prakash L. Requirement of proliferating cell nuclear antigen in RAD6-dependent postreplicational DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9676–9681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z, Svejstrup J Q, Feaver W S, Wu X, Kornberg R D, Friedberg E C. Transcription factor b (TFIIH) is required during nucleotide excision in yeast. Nature. 1994;368:74–76. doi: 10.1038/368074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woodgate R, Levine A S. Damage inducible mutagenesis: recent insights into the activities of the Umu family of mutagenesis proteins. Cancer Surv. 1996;28:117–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]