Abstract

The examination of the influence of morphine on behavioral processes, specifically learning and memory, holds significant importance. Additionally, microtubule proteins play a pivotal role in cellular functions, and the dynamics of microtubules contribute to neural network connectivity, information processing, and memory storage. however, the molecular mechanism of morphine on microtubule dynamics, learning, and memory remains uncovered. In the present study, we examined the effects of chronic morphine administration on memory formation impairment and the kinetic alterations in microtubule proteins induced by morphine in mice. Chronic morphine administration at doses of 5 and 10 mg/kg dose-dependently decreased subjects' performance in spatial memory tasks, such as the Morris Water Maze and Y-maze spontaneous alternation behavior. Furthermore, morphine was found to stabilize microtubule structure, and increase polymerization, and total polymer mass. However, it simultaneously impaired microtubule dynamicity, stemming from structural changes in tubulin dimer structure. These findings emphasize the need for careful consideration of different doses when using morphine, urging a more cautious approach in the administration of this opioid medication.

Keywords: Spatial Memory, Microtubule dynamics, Morphine, Synaptic plasticity

Highlights

-

•

Morphine administration impairs spatial memory in adult male mice

-

•

Morphine induces the stabilizing of the microtubule dynamicity in the animal's brain

-

•

Spatial memory impairment in animals can be due to the decreasing microtubule dynamicity

1. Introduction

Morphine is an opioid medication commonly utilized for pain relief; nevertheless, it is also a highly addictive substance capable of inducing tolerance, dependence, and addiction (Toussaint et al., 2022).

An increasing body of evidence suggests that both acute and chronic administration of morphine can impact learning and various forms of memory, including spatial memory (Li et al., 2001, Ranganathan and D’Souza, 2006). Systemic administration of morphine in mice impaired spatial memory function and exploratory behavior in both the Morris Water Maze and Y-maze experiments (Ma et al., 2007, Kitanaka et al., 2015, Khani et al., 2022).

The precise mechanisms responsible for morphine-induced memory impairment are not yet fully understood; however, it is believed to involve alterations in neurotransmitter function and synaptic plasticity (Bayassi-Jakowicka et al., 2022).

Chronic morphine administration induces morphological alterations in the cytoskeleton, leading to reduced dendritic branching and spine density (Sklair-Tavron et al., 1996, Robinson and Kolb, 1999). Morphine modulates the expression of cytoskeletal or cytoskeletal-associated proteins (Marie-Claire et al., 2004, Xu et al., 2005, Moron et al., 2007). One of the primary components of the cytoskeleton is the microtubule protein.

Microtubules, cytoskeletal filaments in eukaryotic cells, comprise α and β subunits (Dent, 2017), They are polarized polymeric tubes with dynamic ends (Akhmanova and Steinmetz, 2019). Chronic morphine treatment reduces the expression levels of tubulin and Tau (a microtubule-associated protein) at both the mRNA and protein levels (Marie-Claire et al., 2004).

Dynamic microtubules are involved in dendritic spine changes and synaptic plasticity (Jaworski et al., 2009a, Jaworski et al., 2009b). Numerous studies have explored the correlation between microtubule dynamicity, learning, and memory. Microtubule dynamicity denotes their capacity for rapid alterations in length and orientation, critical for diverse neuronal processes such as axonal growth and synaptic remodeling (Mun et al., 2023, Waites et al., 2021).

Furthermore, research has demonstrated that the distribution of microtubules in neurons changes long-term potentiation (LTP), considered the most widely accepted model of memory formation (Mitsuyama et al., 2008). It has been reported that Taxol administration impaired spatial memory function in the Morris Water Maze (MWM) test, and this has been associated with the impairment of microtubule dynamicity (Atarod et al., 2015a, Atarod et al., 2015b).

By previous studies, microtubule dynamicity has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in synaptic plasticity and memory formation. Furthermore, morphine has been shown to impact synaptic connections and reorganizations in the brain (Pomierny-Chamioło et al., 2014), adversely affecting learning and memory.

Hence, it can be postulated that morphine exerts its influence through alterations in microtubule dynamicity. In the current study, we assessed the memory performance of mice following morphine administration using the Morris water maze and Y-maze spontaneous alternation. We explored the interaction between the effects of morphine and microtubule dynamicity in this spatial performance test.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemicals

All materials and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Morphine sulfate was obtained from Temad Company, Tehran, Iran.

2.2. Animals

A total number of 30 adult male Swiss mice, weighing 18–20 g approximately four months old at the beginning of the test, were purchased from the animal center of the Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics (IBB), University of Tehran. The Research Ethics Committee approved the present study of Amol University of Special Modern Technologies, Amol, Iran (Ir.ausmt.rec.1400.20). The animals were housed in standard cages (10 in each cage) under a 12-hour light-dark cycle and constant temperature (23 3) with freely available food and water. The processes have followed the National Research Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The animals were transferred to the laboratory one hour before the tests, and all experiments were carried out from 8:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m.

2.3. Morphine administration

After a week of acclimatization to colony room conditions, a total of 30 mice were randomly allocated into three groups (n = 10): a control group (saline-injected) and two groups treated with morphine (5 and 10 mg/kg) administered 30 min before trials for four consecutive days. On the fifth day, a 60-second probe trial was conducted.

Morphine was obtained in powder form and dissolved in saline to achieve final concentrations of 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg (Li et al., 2001). Morphine was injected intraperitoneally (IP) at an equal daily dose 30 min before the tests (Chen et al., 2018).

2.4. Morris water maze test

The Morris Water Maze (MWM) was conducted following a previously described protocol (Bromley-Brits et al., 2011) with minor modifications. In summary, the apparatus utilized was a circular black pool measuring 120 cm in diameter and 40 cm in height, centrally placed in an isolated room. Several visual cues were strategically positioned in consistent, unaltered locations, easily visible from within the pool.

The transparent platform (10 cm in diameter) was located at one of the quadrants (quadrant 2, Fig. 1). It was hidden 1 cm beneath the water surface (water temperature 22 °C) so mice could easily get and stay on it.

Fig. 1.

The schematic patterns of MWM. Q2 is a target quadrant in the acquisition training trials.

The experiments were performed over five continuous days; one day before day 1, mice were introduced to the pool with a platform and visible clues. During days 1–4, an invisible Plexiglas platform was placed 1 cm under the water. The platform's location was unchanged throughout all the days and trials, but the starting direction differed with each trial each day. Four trials were conducted each day during the training days. Each mouse commenced the trial at the pool's edge, facing the wall. For each animal, three factors were recorded: the amount of time spent to find the platform (latency), the distance the animal swam before finding it (distance), and the swimming speed (velocity).

Each mouse was given at most 180 s(s) to find the platform. Once the animal found the platform, it was allowed to stay on it for 30 s before being returned to its cage. If the animal could not find the platform in 180 s, it was taken and placed on the platform and allowed to remain there for 30 s). On day five, a probe test was performed, the platform was removed from the pool, and mice were let to swim for 60 s. The time each animal spent in the platform quadrant was recorded.

2.5. Y-maze test

Y-maze testing was conducted, as reported previously (Kitanaka et al., 2015). The Y-maze used in this study was made of three wooden arms (5 × 30 cm) and 7.5 cm height, linked by a common central platform (triangular neutral zone, Fig. 2). Mice that finished the MWM test were put into the central zone of the Y-maze, and arm entries were recorded for 8 min. Alternation behavior was defined as consecutive entries into all three arms without repeated entries and was expressed as a percentage of the total arm entries using the following equation:

| Y = number of triads/ (total number of arms entries-2) × 100 |

Fig. 2.

The schematic patterns of Y-maze test. Three arms are described with A, B and C. The central zone is shown in red.

The total number of arm entries measures locomotor activity during the testing session (Prieur and Jadavji, 2019).

2.6. Microtubule extraction following the Y-maze test

Following the Y-maze test, microtubule was extracted from the animals ‘brain. Tubulin dimers were purified from the brain of animals through homogenization in the PEM buffer (100 mM PIPES adjusted to pH 6.9, 2 mM MgSO4, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM ATP). The final homogenization was then centrifuged at 30,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant containing tubulins was polymerized by adding 0.5 mM Mg2+ GTP in a shaker incubator at 37 °C for 45 min. Next, glycerol (33% V/V) was added to microtubules, centrifuged at 120,000 g for 45 min at 25 °C, and the pellet was then suspended in PEM buffer. Microtubules were then depolymerized at 4 °C and immediately centrifuged at 85,000 g for 45 min at 4 °C. The pellet contains tubulins, and MAPs (microtubule associated protein) were suspended in PEM buffer and stored at −70 °C for polymerization experiments. Anion exchange chromatography with a phosphocellulose column (25 ml bed volume) was then used for the separation of tubulins from MAPs (Gholami et al., 2018, Gholami et al., 2019). About 2 mg/ml of protein was loaded onto the column with a constant rate flow of 1 ml/min. The concentration of proteins was determined by Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) in which bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used for quantification as a standard. Finally, the purity of extracted tubulins was analyzed by 10% SDS PAGE (Fig. 6). All samples were stored at −70 °C for the following experiments.

Fig. 6.

Tubulin extraction (lane A) and purification (lane B) from animal brain.

2.7. Turbidity assessments

Microtubule polymerization was measured using a Cary 100 Bio UV/ visible spectrophotometer equipped with a thermometer (Varian, Australia). One mM Mg2+ GTP was added to microtubule suspensions at 37 °C, and the process was detected at 350 nm absorbance (Gholami et al., 2018).

2.8. Kinetic parameters of tubulin polymerization

After conducting the polymerization assay at 350 nm, additional insights were gleaned through a polymerization curve (Johnson and Borisy, 1977). To study the nucleation/lag phase, which occurs in the very first few minutes of a polymerization assay, we calculated the tenth time or "t1/10". "t1/10" describes the time needed to produce 1/10 of the final mass of the polymer (Bonfils et al., 2007). The polymerization rate, which indicated how fast the assembly occurred, was analyzed by calculating the logarithmic phase of each curve. The maximum absorbance in 350 nm, which shows the final mass, was recorded in approximately 30 min. Afterward, to study the stability of microtubule structure and depolymerization, we reduced the temperature to 4 °C.

The depolymerization assay lasted for 20–30 min. The minimum absorbance was also recorded, and the slope of the depolymerization assay was calculated (Atarod et al., 2015a, Atarod et al., 2015b).

2.9. Circular dichroism spectroscopy

The secondary structures of α/β tubulins purified from the brains of mice in the experimental groups were performed by a CD spectrophotometer (Aviv Biomedical, USA). For the analysis of the secondary structure, the far-ultraviolet CD spectra were monitored in a range of 190–260 nm (Dadras et al., 2013).

2.10. Statistical analysis

The Morris Water Maze (MWM) data underwent a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), while one-way ANOVA was utilized to assess behavioral parameters across groups over the four days. Analysis of the probe data and Y-maze test results involved one-way ANOVA, and Dunnett's post hoc test was performed to ascertain differences relative to the control group.

For the analysis of microtubule investigation data, one-way ANOVA was employed, followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis for mean comparisons. Statistical significance was set at a p-value less than 0.05. The results were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of morphine on spatial memory in the MWM

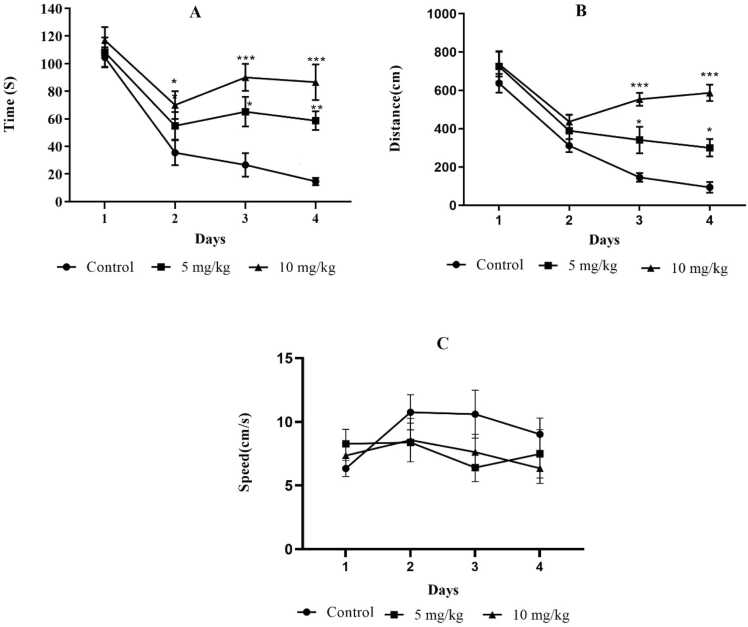

During the trial tests, we observed significant differences in dose × trial effects on escape latencies (F (6, 106) = 2.315, P = 0.04) and swimming distance (F (6, 106) = 3.994, P = 0.001) but not on swimming velocity (F (6, 106) = 0.964, P = 0.453). Morphine treatment significantly affected escape latencies (F (2, 106) = 24.96, P < 0.001) and swimming distance (F (2, 106) = 30.96, P < 0.001), but had no significant effect on swimming velocity (F (2, 106) = 1.828, P = 0.165).

On the second trial day, 10 mg/kg morphine-treated animals showed a significant increase in escape latency compared to the control group (P < 0.05, Fig. 3A). On trial test days 3 and 4, the escape latency increased significantly (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 for 5 mg/kg, respectively, and P < 0.001 in 10 mg/kg in both days), as well as swimming distance in 5 and 10 mg/kg morphine-treated animals compared to the control (P < 0.05 in 5 mg/kg and P < 0.001 in 10 mg/kg in both days, Fig. 3A & B). Swimming velocity in MWM refers to the locomotor activity of the animal (Vorhees and Williams, 2006), which did not change during the trial sessions in morphine-treated groups (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

The Morris Water Maze (MWM) trials were conducted over four consecutive days. A) The mean escape latency (time), B) The mean swimming distance (distance), and C) The mean swimming velocity (speed) were assessed in both control and morphine-treated animals (morphine: 5 and 10 mg/kg). Asterisks indicate significant differences (Two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett comparison post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with the control; 10 mice/group).

3.2. Results of probe test

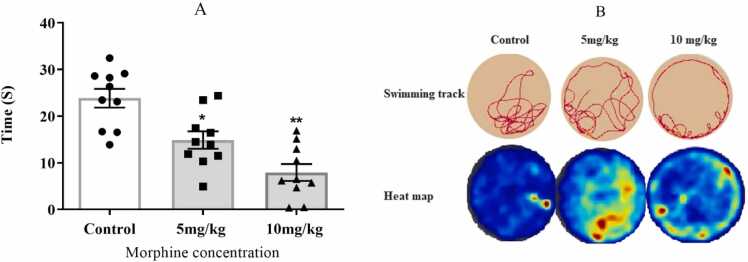

Our results on the probe day test showed that morphine-treated mice (5 and 10 mg/kg) spent significantly less time in target quadrants (quadrant 2) compared to the control group (F (2, 27) = 8, P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 for 5 and 10 mg/ml respectively, Fig. 4A. Swimming track and heat map of the probe day test are represented in Fig. 4B.

Fig. 4.

Probe trial performance was assessed as follows: A) The mean escape latency (time) in control and morphine-treated animals, with morphine administered at 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg. B) The swimming track and heat map of the Morris Water Maze (MWM) on the probe day test revealed that subjects in the morphine-treated groups spent less time in the target quadrant compared to the control group. (One-way ANOVA, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; Values are presented as means ± SEM, n = 10/group).

3.3. Effects of morphine on spontaneous alternation behavior in the Y-maze

After completing the probe test day, the Y-maze test was conducted following the procedures outlined in the materials and methods section. Fig. 5 illustrates the percentage of alternation behavior (A) and the total number of arm entries (B). One-way ANOVA applied to the data in Fig. 5A revealed a significant main effect of treatment (F (2, 26) = 11.57, P < 0.01). Post hoc comparisons demonstrated that Y-maze alternations were significantly reduced in mice treated with morphine (5 and 10 mg/kg) compared to control mice treated with saline (P < 0.01, P < 0.001 for 5 and 10 mg/kg morphine, respectively).

Fig. 5.

The impact of morphine on spontaneous alternation behavior (A) in mice assessed in a Y-maze and (B) the total number of arm entries was evaluated using one-way ANOVA (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). The values are presented as means ± SEM (n = 10/group).

The analysis of the total number of arm entries, which serves as an indicator of locomotor activity, revealed that there was no significant effect of treatment (F (2, 26) = 1.017, P = 0.37) in the morphine-treated groups.

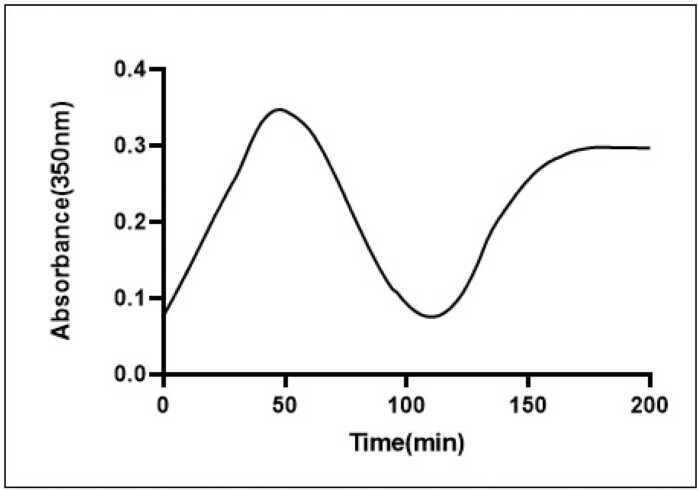

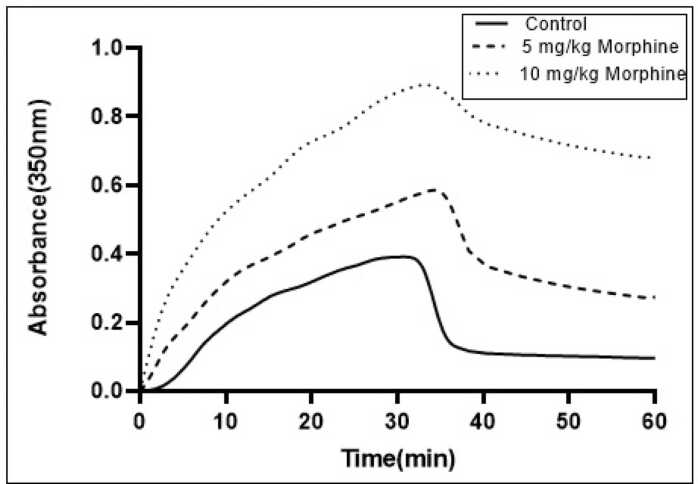

3.4. Kinetics of microtubule assembly

Tubulin polymerization was performed through cycles of polymerization and depolymerization at 37 °C and 4 °C using brain-extracted protein from the control group. The temperature variation induced changes in absorbance at 350 nm, as illustrated in the control tubulin sample (Fig. 7). To investigate the impact of injected morphine on microtubule dynamicity, we isolated microtubules from the brains of the animals following the Y-maze test. Microtubule polymerization and depolymerization were assessed at 37 °C and 4 °C, respectively (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Cycles of tubulin polymerization and depolymerization at 37 and 4 °C.

Fig. 8.

The tubulin polymerization and depolymerization assays were conducted on brain extracts from both saline and morphine-treated groups (5 and 10 mg/kg). The polymerization assay occurred at 37 °C, followed by a temperature reduction to 4 °C for the depolymerization assay. Morphine administration led to a significant increase in maximum absorbance.

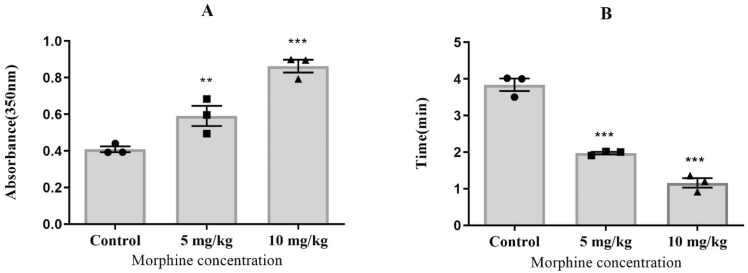

In the polymerization phase of microtubule analysis, a significant increase in maximum absorbance was observed in the groups administered 5 and 10 mg/kg of morphine (F (2, 6) = 63.4, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, respectively, as shown in Fig. 9A). The nucleation phase was notably shorter in the morphine-treated groups (F (2, 6) = 93.5, P < 0.0001). Specifically, the mean time of the nucleation phase, t1/10, for the control group was 4.221 ± 0.0132 s, while the times for the 5 and 10 mg/kg morphine groups were 2.022 ± 0.0254 s and 1.221 ± 0.033 s, respectively (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Kinetic parameters of tubulin polymerization in brain-extracted tubulin were assessed in the control and morphine-treated groups (5 and 10 mg/kg). A) The maximum absorbance at 350 nm increased in both morphine-treated groups compared to the control group. B) The tenth time (the time required to produce 1/10 of the final mass of the polymer) was decreased by morphine treatment compared to the control saline group. (One-way ANOVA, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Values are presented as means ± SEM, n = 10/group).

Furthermore, morphine induced a significant increase in the polymerization rate for both doses compared to the control group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Maximum Absorbance and Polymerization Rate at 37 °C. Kinetics of the polymerization assay exhibited significant alterations. Data were derived from three repetitions.

| Control group | 5 mg/kg morphine | 10 mg/ kg morphine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum absorbance | 0.3750 ± 0.0175 | 0.6076 ± 0.0180** | 0.9030 ± 0.0050*** |

| Rate of polymerization | 0.0122 ± 0.0001 | 0.0188 ± 0.0008** | 0.0280 ± 0.0009*** |

(**P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, compared with control); Values represent the mean ± SEM. (n = 10/group).

The minimum absorbance showed a significant increase in the 5 and 10 mg/kg morphine-treated groups compared to the control (F (2, 6) = 34.95, P < 0.001 for both groups, Table 2, Lane 1). Conversely, the rate of depolymerization decreased in both morphine-treated groups (F (2, 6) = 11, P < 0.05 for both groups, Table 2, Lane 2).

Table 2.

The minimum absorbance and rate of depolymerization were calculated following the temperature reduction to 4 °C. Both depolymerization assay kinetics changed significantly. Data were obtained from three repetitions.

| Control group | 5 mg/kg morphine | 10 mg/ kg morphine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum absorbance | 0.3960 ± 0.002636 | 0.5996 ± 0.0023*** | 0.8918 ± 0.0079*** |

| Rate of depolymerization | 0.01984 ± 0.0015 | 0.0141 ± 0.0011* | 0.0081 ± 0.0003* |

(One way ANOVA, *P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001, Values are shown as means ± SEM (n = 10/group).

3.5. CD spectroscopy of tubulin demonstrated significant changes in the secondary structure of tubulin

According to our CD data, morphine treatment distinctly altered the secondary structure of tubulin in a dose-dependent manner: there was an increase in α-helix structure in morphine-treated samples and a decrease in β secondary structures and random coil compared to the control group. The percentage of secondary structures is summarized in Table 1.

Morphine-treated samples exhibited heightened intensity in negative ellipticity, and both the positive and negative CD bands displayed a shift in the x-axis towards lower wavelengths (Fig. 10). Therefore, as the morphine concentration increased, it appeared that more peptides tended to form α-helix structures (Table 3).

Fig. 10.

The impact of morphine on the secondary structure of tubulin is depicted in the graph. The solid line represents the control, the dashed-dot line represents incubation with 5 mg/kg, and the dotted line represents incubation with 10 mg/kg morphine.

Table 3.

Alteration of tubulin secondary structures in the presence of different concentrations of morphine has been shown. All numbers are in percent (%).

| α-helix | β-turn | β- antiparallel | β-parallel | Random coil | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mg/kg | 49.1 | 14.3 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 24 |

| 5 mg/kg | 38.1 | 15.9 | 7 | 7.6 | 30.1 |

| 0 mg/k | 35 | 16.4 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 31.6 |

4. Discussion

Synaptic plasticity stands out as a prominent property of the mammalian brain, signifying the synapses' ability to alter their strength in response to activity. This fundamental property plays a crucial role in diverse cognitive functions, including learning and memory. Long-term potentiation (LTP) is a widely recognized form of synaptic plasticity, characterized by a sustained enhancement in the strength of synaptic connections between neurons following high-frequency stimulation of a presynaptic neuron. LTP is deemed to underlie various facets of learning and memory, serving as a cellular mechanism for memory storage in the brain (Neves et al., 2008, Lømo, 2018). The molecular mechanisms that underlie long-term potentiation (LTP) entail the activation of diverse signaling pathways and the involvement of specific molecules, including NMDA receptors, AMPA receptors, as well as various kinases and phosphatases. These molecules play crucial roles in the initiation, perpetuation, and manifestation of LTP (Bagwe et al., 2023).

Research studies have demonstrated that opioids, including morphine, can influence synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation (LTP) in different brain regions, such as the hippocampus and the amygdala. Chronic opioid administration has been observed to impair the initiation and sustenance of LTP in animal models. These findings indicate that opioids may disrupt the cellular mechanisms of learning and memory, potentially contributing to the cognitive deficits linked with opioid use (Hauser et al., 2023). Opioids, particularly morphine, have the potential to impact learning and memory processes, leading to memory impairment (Sarkaki et al., 2022). Numerous studies have reported the disruption of hippocampal plasticity, manifested as reduced LTP, under both acute and chronic exposure to opiates (Beltran-Campos et al., 2015, Kutlu and Gould, 2016).

A solitary injection of morphine resulted in an altered gene expression profile, predominantly affecting genes associated with cytoskeleton-related proteins (Loguinov et al., 2001). Prolonged administration of morphine in the rat striatum induced alterations in proteins associated with microtubule polymerization, stabilization, intracellular trafficking, and markers of neuronal growth and degeneration, including α-tubulin, Tau, and Stathmin (Marie-Claire et al., 2004). Morphine administration induces alterations in protein functions through post-translational modifications (PTMs), including phosphorylation. Studies have revealed an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of various cytoskeletal proteins, such as different isoforms of tubulin and actin, in morphine-dependent rat brains (Kim et al., 2005).

Numerous studies have concentrated on elucidating opioid receptor signaling, regulation, and trafficking. It has been disclosed that chronic morphine administration modifies the expression and functional effects of the G-protein receptor, which regulates downstream cytoskeletal proteins (Xu et al., 2005).

In the present study, we endeavored to elucidate a potential mechanism for the impact of morphine on memory function. Comprehending the influence of opioids on synaptic plasticity and LTP is, therefore, imperative for devising effective treatments for opioid addiction and mitigating the adverse impact of these substances on cognitive.

This paper demonstrated that the administration of morphine (5, 10 mg/kg) led to spatial memory impairment in mice, consistent with previous findings (McNamara and Skelton, 1991, Li et al., 2001, Farahmandfar et al., 2010, Khani et al., 2022, Mozafari et al., 2022). Our data from the Y-maze test corroborated this notion, aligning with previous studies (Castellano, 1975, Ma et al., 2007, Kitanaka et al., 2015, Chen et al., 2018). Considering the swimming speed in the MWM and the number of total arm entries in the Y-maze alternation test, the poor performance of mice in the behavioral test is not attributable to locomotor activity issues. Consequently, morphine negatively impacted the animals' spatial memory function, consistent with previous studies (Aguilar et al., 1998, Ma et al., 2007).

Microtubules are highly dynamic structures, and their dynamicity is an essential property of cellular plasticity. Microtubules penetrated the spines and dendrites and maintained their shape, a result reported by electron microscopy, biochemical studies, computational methods, and super-resolution imaging (Quinlan and Halpain, 1996; Jaworski et al., 2009a, Jaworski et al., 2009b Dent, 2017). Several recent studies have begun to suggest that microtubule dynamics in dendrites play essential roles in brain function and diseases. LTP, which is related to memory consolidation (Nabavi et al., 2014), is affected by changes in microtubule dynamicity. Therefore, dysfunction of microtubules may impair synaptic plasticity and, consequently, learning and memory (Craddock et al., 2012). Microtubule-stabilizing agents can prevent microtubule instability in tau protein malfunction-related diseases (Michaelis et al., 1998, Matsuoka et al., 2008). However, as previously studied in our laboratory, microtubule-stabilizing agents such as paclitaxel have adverse effects on microtubule dynamicity, thus, impairing memory function (Atarod et al., 2015a, Atarod et al., 2015b).

Turbidity measurement of the animals' brain tubulin following the behavioral test demonstrated a significant impact of morphine on microtubule polymerization and depolymerization. Morphine significantly increased the microtubule stability and the final mass through an increasing polymerization rate and accelerating nucleation. However, morphine decreased the microtubule depolymerization rate at 4 °C. Morphine provided stable microtubule structures, and the dynamicity of the microtubule was significantly reduced. Our CD data represented secondary structural changes of tubulin of morphine- treated animals. Morphine induced more α-helix structures which are more stable than the other structures and decreased in β-secondary structures.

Since microtubule dynamicity is more important than stability in memory formation, morphine disrupted spatial memory by decreasing microtubule dynamicity. Microtubule rigidity can adversely affect synaptic plasticity and impair learning and memory functions.

Morphine exerts its effect by binding to its receptor -G-protein coupled receptor- in the brain and activates a cascade inside the cell which leads to many molecular changes inside the cell (Sharma et al., 1977, Chakrabarti et al., 2016). The authors of the paper suggest that morphine administration affects microtubule dynamicity indirectly, which contributes to memory impairment in laboratory animals. Our data is in agreement with a previous study that suggests that morphine-induced changes in microtubule dynamics can alter the cytoskeletal structure of neurons and impair their ability to undergo synaptic plasticity (Carulli and Verhaagen, 2021). This is an important finding, as it provides further support for the hypothesis that morphine can interfere with the cellular mechanisms of learning and memory by affecting microtubule dynamics which is critical for learning and memory.

In these behavioral tasks, the morphine-induced memory impairment could be partially due to the disturbance of the microtubule dynamicity in the animal's brain. However, further investigation on the signaling pathways which regulate microtubule dynamicity, and various other mechanisms involved in this process must be conducted.

5. Conclusion

Our study elucidates that morphine-induced changes in microtubule dynamicity substantially contribute to spatial memory impairment. Chronic morphine administration disrupts synaptic plasticity, favoring microtubule stability over dynamicity, ultimately compromising cognitive function. These findings underscore a novel mechanism through which opioids influence learning and memory processes. Understanding these cellular dynamics is crucial for developing targeted interventions to alleviate the cognitive effects associated with opioid use. Further research into the intricate signaling pathways regulating microtubule dynamics is warranted for a comprehensive understanding of these processes.

Ethical approval

The procedure was performed under the international line for animal care and use (NIH publication # 85–23, revised in 1985). The ethical guideline for investigating experimental animals was followed in all tests. The Research Ethics Committee approved the present study of Amol University of Special Modern Technologies, Amol, Iran (Ir.ausmt.rec.1400.20). Also, the study is reported by ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

M.M., Gh.D., and R.Gh. designed the research. M.M. collected the experimental materials. M.M., Gh.D., and R.Gh conducted experiments. M.M. and Gh.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript submission.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. A. Mohammadkhani for his support during the preparation of the manuscript. The authors received financial support from the Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics (IBB), University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. Also, this research work has been supported by a research grant from the Amol University of Special Modern Technologies, Amol, Iran.

References

- Aguilar M., Minarro J., Simón V.M. Dose-dependent impairing effects of morphine on avoidance acquisition and performance in male mice. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 1998;69(2):92–105. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1997.3804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmanova A., Steinmetz M.O. Microtubule minus-end regulation at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2019;132(11):jcs227850. doi: 10.1242/jcs.227850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atarod D., Eskandari-Sedighi G., Pazhoohi F., Karimian S.M., Khajeloo M., Riazi G.H. Microtubule dynamicity is more important than stability in memory formation: an in vivo study. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2015;56:313–319. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0535-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atarod D., Eskandari-Sedighi G., Pazhoohi F., Karimian S.M., Khajeloo M., Riazi G.H. Microtubule dynamicity is more important than stability in memory formation: an in vivo study. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2015;56(2):313–319. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0535-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwe P.V., Deshpande R.D., Juhasz G., Sathaye S., Joshi S.V. Uncovering the significance of STEP61 in Alzheimer’s disease: structure, substrates, and interactome. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s10571-023-01364-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayassi-Jakowicka M., Lietzau G., Czuba E., Patrone C., Kowiański P. More than addiction—the nucleus accumbens contribution to development of mental disorders and neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(5):2618. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran-Campos V., Silva-Vera M., Garcia-Campos M., Diaz-Cintra S. Effects of morphine on brain plasticity. Neurol. (Engl. Ed. ) 2015;30(3):176–180. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfils C., Bec N., Lacroix B., Harricane M.-C., Larroque C. Kinetic analysis of tubulin assembly in the presence of the microtubule-associated protein TOGp. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282(8):5570–5581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605641200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley-Brits K., Deng Y., Song W. Morris water maze test for learning and memory deficits in Alzheimer's disease model mice. JoVE (J. Vis. Exp. ) 2011;(53) doi: 10.3791/2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carulli D., Verhaagen J. An extracellular perspective on CNS maturation: perineuronal nets and the control of plasticity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(5):2434. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano C. Effects of morphine and heroin on discrimination learning and consolidation in mice. Psychopharmacologia. 1975;42(3):235–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00421262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S., Chang A., Liu N.J., Gintzler A.R. Chronic opioid treatment augments caveolin‐1 scaffolding: relevance to stimulatory μ‐opioid receptor adenylyl cyclase signaling. J. Neurochem. 2016;139(5):737–747. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Fu Y., An Y., Cao J., Wang J., Zhang J. Interactive effects of morphine and dopamine receptor agonists on spatial recognition memory in mice. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018;45(4):335–343. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock T.J., Tuszynski J.A., Hameroff S.J.P. c b. Cytoskeletal signaling: is memory encoded in microtubule lattices by CaMKII phosphorylation? Plos Comput. Biol. 2012;8(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadras A., Riazi G.H., Afrasiabi A., Naghshineh A., Ghalandari B., Mokhtari F. In vitro study on the alterations of brain tubulin structure and assembly affected by magnetite nanoparticles. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2013;18:357–369. doi: 10.1007/s00775-013-0980-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent E.W. Of microtubules and memory: implications for microtubule dynamics in dendrites and spines. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2017;28(1):1–8. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-11-0769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farahmandfar M., Karimian S.M., Naghdi N., Zarrindast M.-R., Kadivar M. Morphine-induced impairment of spatial memory acquisition reversed by morphine sensitization in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2010;211(2):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholami D., Ghaffari S.M., Shahverdi A., Sharafi M., Riazi G., Fathi R., Esmaeili V., Hezavehei M. Proteomic analysis and microtubule dynamicity of human sperm in electromagnetic cryopreservation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018;119(11):9483–9497. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholami D., Riazi G., Fathi R., Sharafi M., Shahverdi A. Comparison of polymerization and structural behavior of microtubules in rat brain and sperm affected by the extremely low-frequency electromagnetic field. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12860-019-0224-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser K.F., Ohene-Nyako M., Knapp P.E. Accelerated brain aging with opioid misuse and HIV: New insights on the role of glially derived pro-inflammation mediators and neuronal chloride homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2023;78 doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2022.102653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski J., Kapitein L.C., Gouveia S.M., Dortland B.R., Wulf P.S., Grigoriev I., Camera P., Spangler S.A., Di Stefano P., Demmers J. Dynamic microtubules regulate dendritic spine morphology and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2009;61(1):85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski J., Kapitein L.C., Gouveia S.M., Dortland B.R., Wulf P.S., Grigoriev I., Camera P., Spangler S.A., Di Stefano P., Demmers J.J.N. Dynamic microtubules regulate dendritic spine morphology and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2009;61(1):85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K.A., Borisy G.G. Kinetic analysis of microtubule self-assembly in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;117(1):1–31. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khani F., Pourmotabbed A., Hosseinmardi N., Nedaei S.E., Fathollahi Y., Azizi H. Impairment of spatial memory and dorsal hippocampal synaptic plasticity in adulthood due to adolescent morphine exposure. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2022;116 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2022.110532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.-Y., Chudapongse N., Lee S.-M., Levin M.C., Oh J.-T., Park H.-J., Ho K. Proteomic analysis of phosphotyrosyl proteins in morphine-dependent rat brains. Mol. Brain Res. 2005;133(1):58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitanaka J., Kitanaka N., Hall F.S., Fujii M., Goto A., Kanda Y., Koizumi A., Kuroiwa H., Mibayashi S., Muranishi Y. Memory impairment and reduced exploratory behavior in mice after administration of systemic morphine. J. Exp. Neurosci. 2015;9:S25057. doi: 10.4137/JEN.S25057. (JEN.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlu M.G., Gould T.J. Effects of drugs of abuse on hippocampal plasticity and hippocampus-dependent learning and memory: contributions to development and maintenance of addiction. Learn. Mem. 2016;23(10):515–533. doi: 10.1101/lm.042192.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Wu C., Pei G., Xu N. Reversal of morphine-induced memory impairment in mice by withdrawal in Morris water maze: possible involvement of cholinergic system. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2001;68(3):507–513. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loguinov A., Anderson L., Crosby G., Yukhananov R. Gene expression following acute morphine administration. Physiol. Genom. 2001;6(3):169–181. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.6.3.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lømo T. Discovering long‐term potentiation (LTP)–recollections and reflections on what came after. Acta Physiol. 2018;222(2) doi: 10.1111/apha.12921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M., Chen Y., He J., Zeng T., Wang J. Effects of morphine and its withdrawal on Y-maze spatial recognition memory in mice. Neuroscience. 2007;147(4):1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie-Claire C., Courtin C., Roques B.P., Noble F. Cytoskeletal genes regulation by chronic morphine treatment in rat striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(12):2208–2215. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka Y., Jouroukhin Y., Gray A.J., Ma L., Hirata-Fukae C., Li H.-F., Feng L., Lecanu L., Walker B.R., Planel E. A neuronal microtubule-interacting agent, NAPVSIPQ, reduces tau pathology and enhances cognitive function in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;325(1):146–153. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.130526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara R.K., Skelton R.W. Pretraining morphine impairs acquisition and performance in the Morris water maze: Motivation reduction rather than anmesia. Psychobiology. 1991;19(4):313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis M., Ranciat N., Chen Y., Bechtel M., Ragan R., Hepperle M., Liu Y., Georg G. Protection against β‐amyloid toxicity in primary neurons by paclitaxel (taxol) J. Neurochem. 1998;70(4):1623–1627. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuyama F., Futatsugi Y., Okuya M., Karagiozov K., Kato Y., Kanno T., Sano H., Koide T. Microtubules to form memory. Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. = Arch. Ital. di Anat. Ed. embriologia. 2008;113(4):227–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moron J.A., Abul-Husn N.S., Rozenfeld R., Dolios G., Wang R., Devi L.A. Morphine administration alters the profile of hippocampal postsynaptic density-associated proteins: a proteomics study focusing on endocytic proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2007;6(1):29–42. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600184-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozafari N., Hassanshahi J., Ostadebrahimi H., Shamsizadeh A., Ayoobi F., Hakimizadeh E., Pak‑Hashemi M., Kaeidi A. Neuroprotective effect of Achillea millefolium aqueous extract against oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by chronic morphine in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2022;82:179–186. doi: 10.55782/ane-2022-016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun D.J., Goo B.S., Suh B.K., Hong J.-H., Woo Y., Kim S.J., Kim S., Lee S.B., Won Y., Yoo J.Y., Cho E., Jang E.J., Nhung T.T.M., Triet H.M., An H., Lee H., Nguyen M.D., Park S.-Y., Baek S.T., Park S.K. Gcap14 is a microtubule plus-end-tracking protein coordinating microtubule–actin crosstalk during neurodevelopment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023;120(8) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2214507120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabavi S., Fox R., Proulx C.D., Lin J.Y., Tsien R.Y., Malinow R. Engineering a memory with LTD and LTP. Nature. 2014;511(7509):348–352. doi: 10.1038/nature13294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves G., Cooke S.F., Bliss T.V. Synaptic plasticity, memory and the hippocampus: a neural network approach to causality. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9(1):65–75. doi: 10.1038/nrn2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomierny-Chamioło L., Rup K., Pomierny B., Niedzielska E., Kalivas P.W., Filip M. Metabotropic glutamatergic receptors and their ligands in drug addiction. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;142(3):281–305. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieur E.A., Jadavji N.M. Assessing spatial working memory using the spontaneous alternation Y-maze test in aged male mice. Bio-Protoc. 2019;9(3) doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.3162. e3162-e3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan E.M., Halpain S. Postsynaptic mechanisms for bidirectional control of MAP2 phosphorylation by glutamate receptors. Neuron. 1996;16(2):357–368. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan M., D’Souza D.C. The acute effects of cannabinoids on memory in humans: a review. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188(4):425–444. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0508-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson T.E., Kolb B. Alterations in the morphology of dendrites and dendritic spines in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex following repeated treatment with amphetamine or cocaine. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11(5):1598–1604. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkaki A., Mard S.A., Bakhtiari N., Yazdanfar N. Sex‐specific effects of developmental morphine exposure and rearing environments on hippocampal spatial memory. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2022 doi: 10.1002/jdn.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S.K., Klee W.A., Nirenberg M. Opiate-dependent modulation of adenylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1977;74(8):3365–3369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklair-Tavron L., Shi W.-X., Lane S.B., Harris H.W., Bunney B.S., Nestler E.J. Chronic morphine induces visible changes in the morphology of mesolimbic dopamine neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996;93(20):11202–11207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint A.B., Foster W., Jones J.M., Kaufmann S., Wachira M., Hughes R., Bongiovanni A.R., Famularo S.T., Dunham B.P., Schwark R., Karbalaei R., Dressler C., Bavley C.C., Fried N.T., Wimmer M.E., Abdus-Saboor I. Chronic paternal morphine exposure increases sensitivity to morphine-derived pain relief in male progeny. Sci. Adv. 2022;8(7):eabk2425. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abk2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorhees C.V., Williams M.T. Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1(2):848–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waites C., Qu X., Bartolini F. The synaptic life of microtubules. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2021;69:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2021.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Wang X., Zimmerman D., Boja E.S., Wang J., Bilsky E.J., Rothman R.B. Chronic morphine up-regulates Gα12 and cytoskeletal proteins in Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing the cloned μ opioid receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;315(1):248–255. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.089367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]