Abstract

In many legumes, including Lotus japonicus and Medicago truncatula, susceptible root hairs are the primary sites for the initial signal perception and physical contact between the host plant and the compatible nitrogen-fixing bacteria that leads to the initiation of root invasion and nodule organogenesis. However, diverse mechanisms of nodulation have been described in a variety of legume species that do not rely on root hairs. To clarify the significance of root hairs during the L. japonicus-Mesorhizobium loti symbiosis, we have isolated and performed a detailed analysis of four independent L. japonicus root hair developmental mutants. We show that although important for the efficient colonization of roots, the presence of wild-type root hairs is not required for the initiation of nodule primordia (NP) organogenesis and the colonization of the nodule structures. In the genetic background of the L. japonicus root hairless 1 mutant, the nodulation factor-dependent formation of NP provides the structural basis for alternative modes of invasion by M. loti. Surprisingly, one mode of root colonization involves nodulation factor-dependent induction of NP-associated cortical root hairs and epidermal root hairs, which, in turn, support bacterial invasion. In addition, entry of M. loti through cracks at the cortical surface of the NP is described. These novel mechanisms of nodule colonization by M. loti explain the fully functional, albeit significantly delayed, nodulation phenotype of the L. japonicus ROOT HAIRLESS mutant.

Root hairs of higher plants represent an important extension of the root epidermal surface with functions in the exploitation of various biotic and abiotic resources of the rhizosphere. In addition to their commonly recognized role in water and nutrient uptake from soil, root hairs of legumes also facilitate symbiosis with the beneficial, nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria commonly known as rhizobia. This symbiosis leads to the formation of new root-derived organs, nitrogen-fixing nodules (Szczyglowski and Amyot, 2003).

Initiation of nodule organogenesis involves a highly specific molecular dialogue between the rhizobial microsymbiont and the appropriate host plant. As a result of this dialogue, the morphogenic lipochito-oligosaccharide signaling molecules, known as nodulation or Nod factors (NFs), are secreted by the symbiotic bacteria. Acting as determinants of host specificity (Denarie et al., 1996; Riely et al., 2004), NFs are sensed by the root perception apparatus of the compatible host plant. Recent cloning experiments in the model legumes, Lotus japonicus and Medicago truncatula, revealed the involvement of a family of related LysM receptor-like kinases in the NF-dependent perception mechanism(s) that initiates the intracellular colonization of the root by the symbiotic bacteria and the morphogenesis of nodule primordia (NP; Limpens et al., 2003; Madsen et al., 2003; Radutoiu et al., 2003).

The initial response of root hairs to the NF-producing, compatible strain of rhizobia involves the establishment of de novo polar root hair tip growth and curling, which leads to the formation of typical “shepherd's crook” structures (Lhuissier et al., 2001). These structures entrap the bacteria and serve as a starting point for the initiation of the infection process, which occurs through a local invagination of the plasma membrane and establishment of a growing infection structure, the infection thread (IT). The intercellular progression of the IT through the root hair toward the underlying nodule primordium occurs via a tip-growth-like mechanism and is guided by a specific arrangement of polarized cytoplasm in the underlying cortical cells (van Brussel et al., 1992; van Spronsen et al., 2001).

Only root hairs localized to the susceptible zone of the root and at a particular developmental stage appear to be fully receptive to NFs (Bhuvaneswari et al., 1981). Although the molecular determinates of root hair susceptibility are not well understood, root hairs that have almost reached their mature size have been shown to be the most receptive (Gage, 2004, and refs. therein). Based on the structure-functional analysis of Sinorhizobium meliloti NFs, the presence of at least two NF receptors or two NF-dependent signaling mechanisms at the root hair surface was postulated (Ardourel et al., 1994).

In many legumes, including the model legumes L. japonicus and M. truncatula, root hairs are the principal sites for attachment and intracellular entry of rhizobia. However, the mechanisms by which rhizobia colonize roots vary significantly among different legume species and various root hair-independent mechanisms of root colonization by rhizobia, including cortical intercellular invasion at lateral root bases, have been described (Boogerd and van Rossum, 1997; Guinel and Geil, 2002, and refs. therein). Interestingly, in the tropical legume, Sesbania rostrata, both intracellular and intercellular modes of root invasion by Azorhizobium caulinodans occur. Which invasion pathway is used depends on the particular growth conditions, which determine the availability of susceptible root hairs, and has been shown to be modulated by the plant hormone ethylene (Goormachtig et al., 2004a).

The initial responses of root epidermal and cortical cells to signaling from the NF-producing bacteria set off a cascade of signaling events that restrict the extent of successful infections at the root epidermis and nodule organogenesis in the root cortex (Nutman, 1952; van Brussel et al., 2002). Thus, the susceptibility of roots remains under the strict but flexible control of the host plant, which ensures the homeostasis of the plant-microbe symbiosis. Multiple levels of regulation, including local and systemic signaling events, have been implicated in this process and have been shown to involve the plant hormone ethylene and Har1 receptor kinase-dependent signaling (Penmetsa and Cook, 1997; Wopereis et al., 2000; Krusell et al., 2002; Nishimura et al., 2002). L. japonicus mutants carrying a mutation in the Har1 gene fail to autoregulate nodule formation, resulting in the formation of an excessive number of nodules (hypernodulation phenotype; Wopereis et al., 2000).

In this study, we describe the analysis of several root hair mutants of L. japonicus and the consequences of their associated developmental abnormalities on the outcome of the symbiotic interaction. The mutants were identified from a collection of new L. japonicus germlines derived from a screening for genetic suppressors of the L. japonicus har1-1 hypernodulation phenotype. We show that although the various aberrations in root hair development significantly diminish the effectiveness of the mutant roots to support an efficient colonization by the symbiotic bacteria, the progression of the cortical program for NP organogenesis remains, to a large extent, unaltered and provides an alternative mechanism for successful colonization of the root and the development of nitrogen-fixing nodules.

RESULTS

L. japonicus Wild-Type Root Hair Phenotype

The root hair phenotype of L. japonicus ecotype Gifu plants grown on vertical agar plates (see “Materials and Methods”) has been evaluated in terms of zone distribution, site of origin, patterning, and length.

In wild-type L. japonicus Gifu, root hairs begin to emerge from epidermal cells located approximately 1.0 to 1.5 mm behind the root tip (Fig. 1). There is no specific patterning of root hairs within or between different epidermal cell files in L. japonicus, since every epidermal cell appears to have the potential to produce a root hair. In fact, a vast majority of epidermal cells form root hairs, and only very sporadically root-hairless cells are observed. The rare root-hairless cells are randomly distributed either as single cells or as short stretches of a few cells within a single epidermal cell file (data not shown).

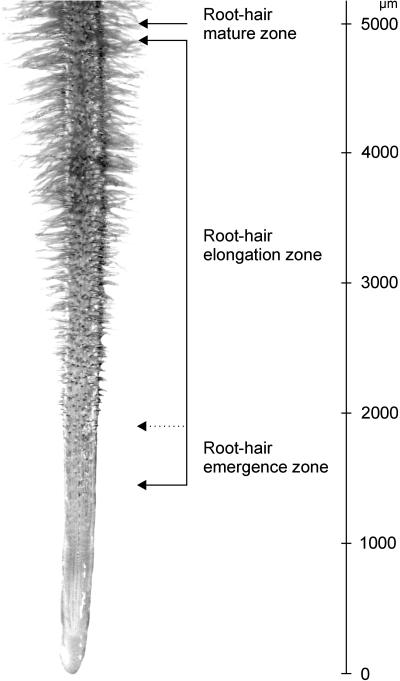

Figure 1.

Zones of root hair development in L. japonicus. An image of a portion of a L. japonicus root is shown and different zones of root hair development are indicated. The transition from the root hair emergence zone to the root hair elongation zone has been assigned arbitrarily and is indicated by a dotted line.

The initiation of root hairs in the L. japonicus root-hair emergence zone begins as a polarized outgrowth from the middle of the outer periclinal cell wall of the epidermal cell (Fig. 2A). The emergence zone is followed, without any defined boundary, by the root hair elongation zone, which terminates with fully extended root hairs in a root hair mature zone (Figs. 1 and 2B). The morphometric measurement of root hairs showed that the mean length of a mature root hair in L. japonicus is 690 ± 120 μm.

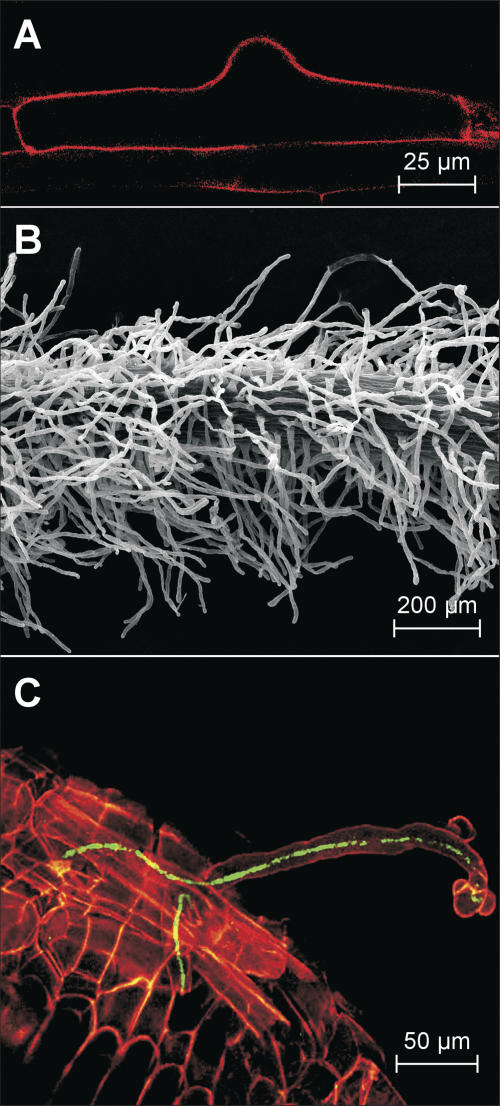

Figure 2.

Features of root hairs in wild-type L. japonicus. A, A confocal fluorescent image of a propidium iodide stained epidermal cell that has initiated root hair growth from the center of the periclinal cell wall. B, A scanning electron micrograph of a portion of wild-type L. japonicus root within the root hair mature zone. C, A scanning confocal image of an infection thread originating from a microcolony at the curled root hair tip and proceeding down into the base of the epidermal cell. M. loti bacteria are tagged with GFP (green fluorescence) and the root tissue has been counterstained with propidium iodide (red fluorescence).

L. japonicus Root Hair Mutants

L. japonicus interacts with its natural microsymbiont M. loti to form nitrogen-fixing nodules in a root hair-dependent manner (Szczyglowski et al., 1998). On the cytological level, the major initial steps in this interaction comprise modification of root hair growth and initiation of the infection process that culminates in the development of an IT. The IT traverses the infected root hair on its way to the root cortex (Fig. 2C).

By performing a screen for genetic suppressors of the L. japonicus har1-1 hypernodulation mutant phenotype (Wopereis et al., 2000), a group of mutants characterized by various aberrations in root hair development and a concomitant low nodulation phenotype (see below) has been identified. This group comprises nine independent double mutant lines, which have been further analyzed with respect to their nonsymbiotic root phenotype and also their ability to interact with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. A detailed description of the genetic screen for suppressors of the har1-1 mutant phenotype and its overall outcome will be reported elsewhere.

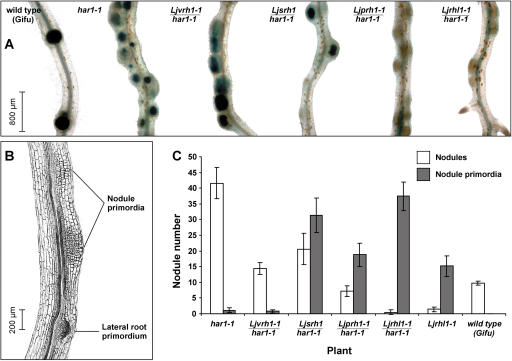

The initial microscopy observations lead to categorization of the root hair double mutant lines into 4 distinct phenotypic classes: (1) root hairless, Ljrhl; (2) petite root hairs, Ljprh; (3) short root hairs, Ljsrh; and (4) variable root hairs, Ljvrh. Images of nonsymbiotic live roots of the parental L. japonicus har1-1 mutant line and representative plants belonging to each mutant phenotypic category are shown in Figure 3, A and B.

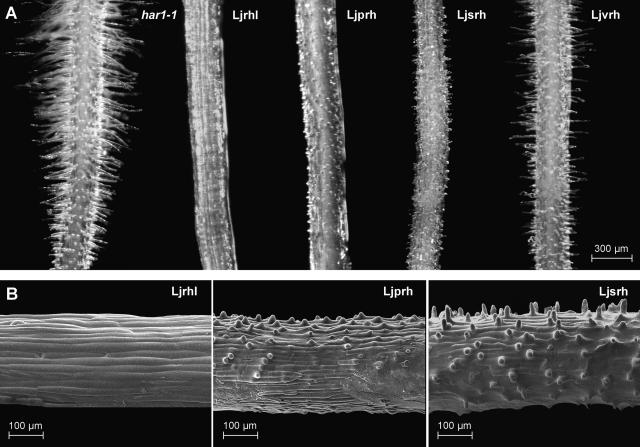

Figure 3.

Root hair phenotypes of L. japonicus mutant lines. A, The har1-1 parental line and double mutants Ljrhl1 har1, Ljprh1 har1, Ljsrh1 har1, and Ljvrh1 har1 are shown. B, Scanning electron micrographs of double mutants Ljrhl1 har1, Ljprh1 har1, and Ljsrh1 har1. Root segments were photographed at approximately 0.3 to 0.5 cm from the root tip.

Since all root hair mutant lines were derived from chemically mutagenized L. japonicus har1-1/har1-1 homozygous mutant seeds (see Fig. 3A), the observed aberrations in the growth and development of root hairs were presumed to be a result of secondary mutations. Upon careful characterization of the har1-1 phenotype with respect to distribution, site of origin, patterning, and length of root hairs, no discernible differences in comparison with wild-type root hair phenotype were found. The presence of the har1-1 allele was indicated by the overall short stature and the bushy root of the root hair mutants reminiscent of the nonsymbiotic har1-1 root phenotype (Wopereis et al., 2000). The genotyping analysis, using a har1-1 allele-specific cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence marker, confirmed that all nine root hair mutant lines are homozygous for the har1-1 mutant allele (data not shown). Further genetic analysis (see below) confirms their double mutant genetic background (Table I). To facilitate the distinction between the double versus single mutant genetic background, the following nomenclature is being used throughout the rest of the text. The double mutants are designated by two corresponding mutant alleles codes (e.g. Ljrhl1 har1-1), while a line carrying a mutation at the single locus in otherwise wild-type genetic background is described by the code of the corresponding mutant allele only (e.g. Ljrhl1).

Table I.

L. japonicus root hair mutants

sm, Root hair single mutant; dm, double mutant. *P, < 0.05.

| Double Mutant Line | Genetic Control | Complementation Groups | Allele |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt:har1-1:sm:dm | |||

| Class 1 (root hairless) | |||

| LjS16-2 | F2 75:21:25:8 (χ2 = 0.53) | a | Ljrhl1-1 |

| LjB13-C | F2 96:30:28:11 (χ2 = 0.46) | a | Ljrhl1-2 |

| LjS3-1 | F2 194:66:78:24 (χ2 = 2.10) | a | Ljrhl1-3 |

| Class 2 (petite root hair) | |||

| LjS24-B | F2 187:69:48:20 (χ2 = 3.92) | b | Ljprh1-1 |

| LjS67-B | F2 110:44:43:20 (χ2 = 4.65) | b | Ljprh1-2 |

| Class 3 (short root hair) | |||

| LjS88-5A | F2 138:5:3:31 (χ2 = 116.26)* | c | Ljsrh1 |

| Class 4 (variable root hair) | |||

| LjB12-IB | F2 137:10:5:37 (χ2 = 106.97)* | d | Ljvrh1-1 |

| LjS49-AA | F2 160:6:2:44 (χ2 = 149.79)* | d | Ljvrh1-2 |

| LjB69-A | F2 168:8:9:47 (χ2 = 139.95)* | d | Ljvrh1-3 |

Root-Hairless Mutants (Class 1)

Three independent double mutant root-hairless Ljrhl1 har1-1 lines (LjS3-1, LjS13-C, and LjS16-2) were identified. These plants were characterized by an almost complete lack of root hairs (Fig. 3, A and B). When grown on a surface of agarose-solidified medium, sporadic trichoblast cells could be found on the roots of these mutant lines. These, however, were usually localized to the base of the root, near the root-hypocotyl junction, and were found with a frequency of less than 1 root hair cell/10 plants. Overall, the root epidermis of the Ljrhl1 har1-1 double mutants remained virtually hairless (Fig. 3B). Genetic complementation tests revealed that the 3 independent class 1 mutant lines represent the same genetic locus (Table I). Therefore, the mutant alleles were designated as Ljrhl1-1, Ljrhl1-2, and Ljrhl1-3, and the corresponding wild-type gene as LjRHL1. The F1 plants derived from crosses between these three lines and wild-type L. japonicus Gifu showed wild-type root hair phenotypes, suggesting a recessive nature of the underlying mutations. This assumption was further confirmed by scoring phenotypic segregations in the resulting F2 populations, which were found to be in good agreement with the predicted Mendelian 9:3:3:1 ratio (wild-type:har1-1:root hairless:double mutant) for 2 independently segregating loci. This confirms that the LjRHL1 locus is inherited in a recessive fashion and independently of the HAR1 locus (Table I).

Petite Root Hair Mutants (Class 2)

Two independent double mutant lines (LjS24-B and LjS67-B) have been identified in the petite root hair phenotypic category (Table I). In contrast to the root-hairless mutants described above, the epidermal cells of class 2 mutants formed clearly identifiable swellings, indicative of the ongoing initiations of root hair development (Fig. 3, A and B). When grown on a surface of agarose-solidified medium, these epidermal swellings failed to transit to the tip growth phase, reaching an average length of only 15 ± 5.6 μm (Fig. 3B). However, when grown in soil, slightly longer root hairs were formed, indicating that under the conditions used, a very short period of tip growth phase may have occurred (data not shown). The mutations underlying the phenotype of class 2 mutants were found to be recessive, allelic, and inherited independently from the HAR1 locus (Table I).

Short Root Hair Mutant (Class 3)

A single plant in class 3 (LjS88-5A) was recovered from the mutagenized population and the corresponding mutant allele was named Ljsrh1 (Table I). The double mutant Ljsrh1 har1-1 plants were capable of initiating root hair growth, which transited to the tip growth phase only to be terminated shortly thereafter. When grown on agar plates, the root hairs of the Ljsrh1 har1-1 mutant reached an average length of 21 ± 7.9 μm. They were erect and tubular in shape, characteristics that clearly distinguish them from the broad-based epidermal swellings of the petite root hair mutants of class 2 (Fig. 3B). The Ljsrh1 allele was found to be recessive, as judged based on the recovery of the wild-type root hair phenotype in the F1 generation derived from the cross between Ljsrh1 har1-1 and wild-type L. japonicus Gifu. In the F2 generation, the proportion of plants showing the root hair phenotype deviated significantly from the expected 9:3:3:1 ratio, indicating linkage of LjSRH1 and HAR1 on Lotus chromosome 3 (Table I). However, recombination events between the LjSRH1 and HAR1 loci were recovered, indicating that the short root hair phenotype was not a result of genetic changes at the Har1 locus.

Variable Root Hair Mutants (Class 4)

Class 4 mutant lines LjB12-IB, LjS49-AA, and LjSB69-A showed a rather complex root hair phenotype. This phenotype was characterized by the presence of variable length root hairs throughout the apical-basal axis of the root. In addition, the overall root hair density was diminished in the double mutant lines as compared with the parental line har1-1 (Fig. 3A). The lower density of root hairs was found to be a result of a developmental defect(s), which appears to cause some elongating root hairs to collapse (data not shown). The combined genetic/phenotypic analysis revealed the recessive nature of the underlying mutations, while the complementation crosses allowed classification of the 3 independent double mutant lines into 1 complementation group (alleles: Ljvrh1-1, Ljvrh1-2, and Ljvrh1-3; Table I), defining a fourth L. japonicus root hair-associated locus, designated as LjVRH1. Interestingly, the segregation analysis indicated a genetic linkage between LjVRH1 and the HAR1 locus (Table I), but again, recovery of recombination events between the LjVRH1 and HAR1 loci proved that the variable root hair phenotype was not due to genetic changes at the HAR1 locus.

With regard to all classes of mutants described above, the single mutant lines homozygous for the wild-type Har1 allele that carry the corresponding homozygous root hair-related mutant alleles have been recovered from the segregating populations (Table I). They were found to have root hair phenotypes identical to their matching parental double mutant lines (see above). However, the phenotypic distinction between single and double mutants was straightforward since, unlike the har1-1 allele carrying plants, the root hair single mutants were characterized by a more elongated and less bushy root system, resembling the wild-type root phenotype. In addition, when grown in the presence of rhizobia, the single mutant lines carrying the Har1 allele recovered wild-type shoot elongation as opposed to the stunted shoot growth observed in the presence of the har1-1 allele in the double mutant lines (data not shown). Interestingly, when grown on either a surface of agar-solidified medium or in soil, the single Ljrhl1-1 mutant line had significantly longer roots than wild-type L. japonicus Gifu (see Supplemental Fig. 1).

Mapping of L. japonicus Root Hair Loci

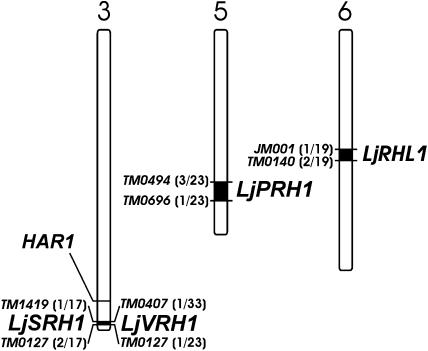

Analysis of the homozygous root hair mutants selected from F2 populations derived from crosses of the double mutant lines Ljrhl1-1 har1-1, Ljprh1-1 har1-1, Ljsrh1 har1-1, and Ljvrh1-1 har1-1 to the polymorphic mapping partner, L. japonicus ecotype MG20, allowed positioning of the underlying loci on the L. japonicus genetic map (Asamizu et al., 2003). Flanking recombinant markers delimit a 0.8-cM interval for the LjVRH1 and LjSRH1 loci on chromosome 3, a 5.2-cM interval for the LjPRH1 locus on chromosome 5, and a 3.2-cM interval for the LjRHL1 locus on chromosome 6 (Fig. 4). The independence of LjVRH1 locus from LjSRH1 was confirmed by performing an allelism test (see “Materials and Methods”). The F1 progeny derived from the cross between Ljsrh1 and Ljvrh1-1 showed a wild-type root hair phenotype, indicating genetic complementation. To confirm that the F1 plant indeed represented a hybrid of the two mutants, F2 progeny of the hybrid F1 plant were examined and were found to segregate short root hair, variable root hair, and wild-type phenotypes.

Figure 4.

Positions of root hair loci LjSRH1, LjVRH1, LjPRH1, and LjRHL1 on L. japonicus chromosomes 3, 5, and 6. Flanking simple sequence repeat markers are given. For all markers shown, the observed ratios of the genotypic classes deviated significantly from the ratios expected if independent segregation from the mutant locus was assumed (P < 0.001; chi-square tests). Thus, all markers shown are linked to their respective root hair loci. The number of recombinants as a fraction of the total number of mutants tested is given for each marker in brackets.

Symbiotic Phenotypes of L. japonicus Root Hair Mutants

In the presence of the har1-1 allele in the double mutant background, all 4 classes of root hair mutants developed nodules. Initial visual inspection of their nodulation phenotype, in comparison with the parental single mutant har1-1 line, showed an overall decrease in nodule number, confirming partial har1-1 suppressor characteristics of the Ljrhl1-1, Ljprh1-1, Ljsrh1, and Ljvrh1-1 mutant alleles.

To examine these nodulation phenotypes in more detail, a M. loti strain carrying a constitutively expressed hemA::lacZ reporter gene fusion was used in subsequent experiments, and the nodulation phenotypes of the double mutants were examined 10 and 21 d after inoculation (dai) and compared to the corresponding phenotypes of wild-type Gifu and the har1-1 parental mutant line (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Symbiotic phenotypes of wild-type (Gifu) and mutant plants (har1-1, and double mutants Ljrhl1 har1, Ljprh1 har1, Ljsrh1 har1, and Ljvrh1 har1. A, Roots of plants 10 dai with M. loti strain NZP2235 carrying a hemA::LacZ reporter gene construct. Roots of all plants shown were cleared and stained for β-galactosidase activity. B, A longitudinal section (25 μm) of the double mutant Ljrhl1 har1 10 dai. NP and emerging lateral root primordium can be easily distinguished. C, Numbers of nodules and NP on the roots of wild type, har1-1, and root hair double mutants (Ljrhl1 har1, Ljprh1 har1, Ljsrh1 har1, and Ljvrh1 har1) and single mutant (Ljrhl1-1) 21 dai with M. loti strain NZP2235 (hemA::LacZ). Roots were cleared and stained for β-galactosidase activity before counting. Mean values ± 95% confidence interval are given for each genotype (n = 10 to 15).

Ten dai, L. japonicus Gifu and the har1-1 single mutant developed wild-type and hypernodulation phenotypes, respectively (Fig. 5A). The dark-blue color of the nodules reflects the activity of the bacterially encoded β-galactosidase lacZ reporter gene and is thus indicative of successful root colonization by M. loti. Dark-blue stained nodules developed on roots of wild-type L. japonicus Gifu, har1-1, Ljvrh1-1 har1-1, and Ljsrh1 har1-1, and to a much lesser extent on the roots of Ljprh1-1 har1-1, but were absent from the roots of Ljrhl1-1 har1-1 (Fig. 5A). Instead, when cleared roots were analyzed (see “Materials and Methods”), a large number of foci of cortical cell divisions were found throughout the entire root system of the Ljrhl1-1 har1-1 (Fig. 5A). These foci were neither found on control uninoculated Ljrhl1-1 har1-1 roots nor were they present after inoculation with M. loti NodC::Tn5 mutant strain that is unable to produce NF, suggesting that they constitute NP (data not shown). This notion is supported by the results of longitudinal sectioning of segments of the Ljrhl1-1 har1-1 root, which showed broad-based foci of cortical cell divisions that are indistinguishable from NP (Fig. 5B). Unstained NP were also formed 10 dai on roots of Ljprh1-1 har1-1 and Ljsrh1 har1-1 but were virtually absent from Ljvrh1-1 har1-1, har1-1, and wild-type L. japonicus Gifu roots (Fig. 5A).

When examined 21 dai, roots of all mutant classes, but not wild-type L. japonicus Gifu, developed 2 types of symbiotic structures: nodules, which upon a histochemical staining for β-galactosidase activity showed dark-blue color indicative of the presence of M. loti, and NP, which in a majority of cases managed to surface through the root epidermis but remained uncolonized (Fig. 5C). L. japonicus Gifu and the har1-1 mutant line formed approximately 10 and 40 nodules, respectively. In contrast, the Ljrhl1-1 har1-1, Ljprh1-1 har1-1, and Ljsrh1 har1-1 lines developed a large number of NP, while they were only very infrequently observed on roots of Ljvrh1-1 har1-1 (Fig. 5C). The capacity of all root hair mutant lines to form nodules was significantly reduced as compared to the parental har1-1 line. At 21dai, the extent of this reduction was found to correlate with the severity of the respective mutant root hair phenotypes (Fig. 5C). Taking the extreme root hair phenotypes as an example, the Ljrhl1-1 har1-1 plants were characterized by the smallest, and the Ljsrh1 har1-1 and Ljvrh1-1 har1-1 plants by the highest, number of nodules (Fig. 5C).

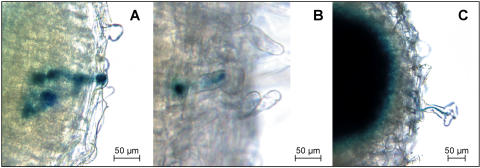

Interestingly, a closer inspection of the infection events at the root epidermis revealed the presence of infection threads that originated within the petite, short, and more elongated variable root hairs of the double mutant lines Ljprh1-1 har1-1, Ljsrh1 har1-1, and Ljvrh1-1 har1-1, respectively (Fig. 6). Since this finding offers, at least in part, an explanation for the observed nodulation phenotype in these 3 mutant lines (see “Discussion”), the further analyses of the nodulation and colonization events have been confined to the most severe root hair phenotype of the L. japonicus mutants of class 1. These analyses were carried out in the context of both double (Ljrhl1-1 har1-1) and single (Ljrhl1-1) mutant genetic backgrounds. The question we sought to answer was if M. loti is capable of colonizing L. japonicus roots through a mechanism that does not require root hairs.

Figure 6.

Representative infection events 21 dai on double mutants Ljprh1-1 har1-1, Ljsrh1 har1-1, and Ljvrh1-1 har1-1. Roots were cleared and stained for β-galactosidase activity to detect the infecting M. loti strain NZP2235 (hemA::LacZ). A, An abnormally broad IT formed within a mutant root hair of Ljprh1-1 har1-1. The IT has ramified within the nodule cortex (B) IT traversing an uncurled root hair on Ljsrh1 har1-1. C, A Ljvrh1-1 har1-1 root hair exhibiting a curled root hair tip encircling a microcolony from which an infection thread descends.

Nodulation of Ljrhl1 in the Double and Single Mutant Backgrounds

At 21 dai, roots of the single Ljrhl1-1 mutant developed numerous NP, while nodules could only be observed sporadically (Fig. 5C). The average number of nodules formed by the Ljrhl1-1 (1.4 ± 0.77) was not significantly different from the Ljrhl1-1 har1-1 double mutant line (0.5 ± 0.7). However, the plants of both genotypes differ significantly in the overall frequency of NP, with Ljrhl1-1 forming fewer NP than the corresponding double mutant line (Fig. 5C).

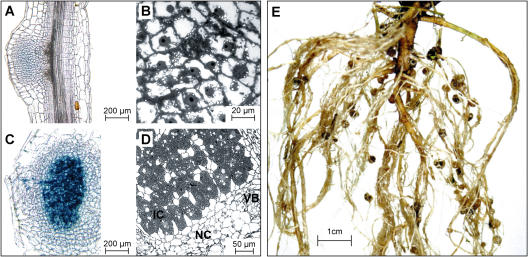

At 42 dai, the number of nodules formed by both Ljrhl1-1 har1-1 and Ljrhl1-1 increased to a larger extent than the number of NP when compared to plants 21 dai, suggesting an improved efficiency with which the roots and/or NP are colonized by M. loti (see Supplemental Fig. 2). The microscopic examination of NP revealed cortical cells containing enlarged, centrally localized nuclei and numerous starch granules, but deprived of symbiosomes (Fig. 7, A and B). In contrast, the nodules were characterized by wild-type histology of a determinate type, consisting of a large central area primarily composed of bacteroid-containing cells that is surrounded by concentric layers of uninfected nodule cortex (Fig. 7, C and D). Examination of histochemically stained sections of these nodules showed the presence of ITs descending from the nodule surface and ramifying within the central region of the nodule infected zone (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Infection phenotypes of Ljrhl1-1 (42 dai). A, A longitudinal section of a NP stained for β-galactosidase activity. B, A light micrograph of a semithin section of an NP. Note the absence of infected cells. Activated cortical cells with centrally located enlarged nuclei and many starch granules are visible. C, A longitudinal section of an infected nodule stained for β-galactosidase activity showing deep-blue color in the nodule central zone and an IT extending from the nodule apex. D, A light micrograph of a semithin section of an infected nodule. Infected cells (IC) are clearly discernible; NC, nodule cortex; VB, vascular bundle. E, Roots of a 4-month-old M. loti infected Ljrhl1-1 plant showing an abundance of nodules.

A few Ljrhl1-1 plants were maintained for an extended period of time (4 months; see “Materials and Methods”). When uprooted, these plants showed a fully developed nodulation phenotype, characterized by the presence of 80 to 150 big nodules distributed all over the root system (Fig. 7E). A microscopic inspection of younger and older root segments of one individual, which developed approximately 150 nodules, showed that the overall hairlessness was maintained throughout the entire growth period, while sectioning of a few nodules revealed their wild-type morphology (data not shown).

How Does M. loti Colonize Roots of the L. japonicus Root-Hairless Mutant?

The ability of M. loti to colonize, albeit with a significant delay, roots of the L. japonicus Ljrhl1-1 mutant could be due to the presence of sporadic root hair cells, an alternative mode(s) of root invasion, or both. The following observations provide support for the existence of at least two mechanisms of roots invasion by M. loti.

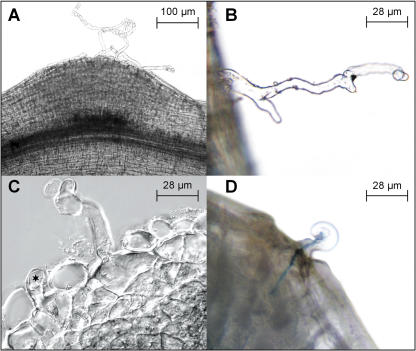

At 21 dai, an occasional association of dark-blue-stained patches of M. loti expressing the hemA::lacZ reporter gene fusion with the cortical surface of the enlarged NP was observed (Fig. 8A). Upon thorough microscopic inspection of many samples, no evidence for the formation of ITs that originate at the cortical surface of, and ramify within, the NP could be found. However, sectioning of several samples has uncovered three examples containing clearly identifiable bacteria, which appear to penetrate a few cortical cell layers deep inside the NP via a mechanism resembling intercellular invasion (Fig. 8B). Although infected cells were not found when the consecutive sections derived from these samples were examined (data not shown), these initial observations prompted us to look for a similar and/or more advanced invasion event in the older (42 dai) plant material. Sectioning of many nodules, 42 dai, revealed a single example of a successful invasion event that originated from a patch of bacteria localized on the cortical surface of the nodule (Fig. 8, C and D). This nodule was sectioned in its entirety and it was clear that the surface patch of bacteria was the only source of infection. The histochemical footprint of M. loti expressing the β-galactosidase reporter gene suggests that, in this particular case, the mode of entry inside the nodule involved the formation of a wide intercellular infection pocket that gave rise to a narrower IT, which eventually led to colonization of the underlying cortical cells of the nodule (Fig. 8, C and D).

Figure 8.

Root hair-independent invasion of NP in the Ljrhl1 mutant by M. loti (hemA::LacZ). A, A longitudinal thick section of an NP showing a bacterial patch on the surface visualized by β-galactosidase staining (21 dai). B, A light micrograph of a toluidine blue stained thin section of an NP showing a surface bacterial patch (asterisk) which progresses via an intercellular route through 3 layers of cortical cells creating an infection pocket (21 dai). C, A transverse section (30 μm) of an infected NP with a surface patch of bacteria leading to the infection pocket and the IT that has ramified within the NP cortex (42 dai). D, Close-up of C. The bacterial patch is continuous with an infection pocket (arrow) that narrows down into an IT.

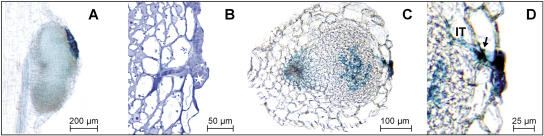

NF-Dependent Root Hair Induction

While examining roots of soil-grown single and double mutants carrying the Ljrhl1-1 allele at 42 dai, an unexpected discovery of root hairs that were associated with a proportion of the enlarged NP and nodules was made. These root hairs were often observed as groups of two to five and were usually short but sometimes very long and deformed (Fig. 9A). In addition, non-nodule-associated (epidermal) root hairs, typically singletons, were observed with increased frequency as compared to uninoculated plants. These root hairs were often deformed and/or branched (Fig. 9B). A closer microscopic examination showed that, in most cases, the nodule-associated hairs originated from cortical cells positioned underneath the fissure in the root epidermis caused by the emerging NP, defining them as the cortical root hairs (Fig. 9C). Importantly, at 42 dai, several examples of ITs traversing multiple hairs present on a single nodule or NP, as well as ITs associated with epidermal root hairs, have been found (Fig. 9D). Those infection threads that were associated with nodules had typically ramified inside the central zone, giving rise to infected cells of the nodule (see Fig. 7C).

Figure 9.

Root hair phenotypes of the Ljrhl1-1 mutant after inoculation with M. loti. A, Three long nodule-associated (cortical) hairs emerging from the apex of a NP. B, A non-nodule-associated (epidermal) root hair with presumed NF induced branching and deformations. C, A differential interference contrast image of an uncolonized NP showing two cortical root hairs, one fully emerged and the second one just emerging (asterisk). D, IT traversing a root (cortical) hair that has emerged from the site of a fissure in the root epidermis at the apex of an enlarged NP.

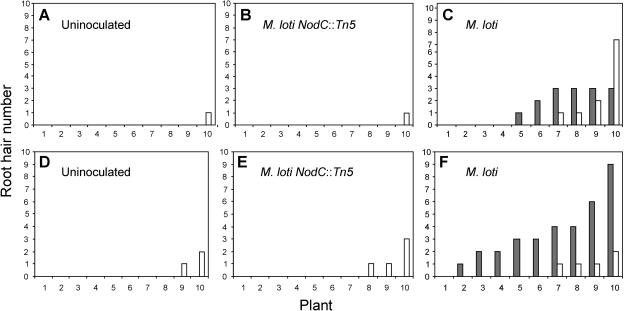

Since root hairs were only very rarely observed on the uninoculated single and double mutant lines carrying the Ljrhl1-1 allele, the augmented presence of root hairs suggested their de novo origin upon inoculation. To test this hypothesis, the frequency of root hairs on 42-d-old roots, which were either uninoculated or inoculated with wild-type or mutant NodC::Tn5 M. loti strains, was carefully evaluated. As expected, the uninoculated roots developed hairs only very sporadically (Fig. 10, A and D), while inoculation with M. loti significantly increased their frequency (Fig. 10, C and F). The M. loti NodC::Tn5 mutant strain was unable to exert a similar effect, indicating that the induction of these root hairs is NF dependent (Fig. 10, B and E). The increase in the frequency of hairs was visible in both genetic backgrounds but was somewhat more pronounced in the Ljrhl1-1 har1-1 mutant. The majority of hairs formed were found to be associated with nodules and NP (Fig. 10F), which are more abundant in the Ljrhl1-1 har1-1 double mutant as compared to the Ljrhl1-1 single mutant line. One week later (49 d after sowing), the inoculated Ljrhl1-1 developed an average of 38 ± 12 root hairs (n = 5; 66% of which were associated with nodules), while uninoculated control plants of the same age formed only 1.2 ± 2.2 root hairs/plant. The presence of ITs, within both the nodule-associated and the non-nodule (epidermal) root hairs, was clearly observable at this late time point during symbiotic interaction, suggesting that both types of root hairs contributed to the colonization of the Ljrhl1-1 root by M. loti.

Figure 10.

Numbers of nodule-associated (gray bars) and non-nodule-associated (white bars) root hairs for individual plants (1–10) that were either uninoculated or were inoculated with the M. loti strains as shown. A to C, Single mutant Ljrhl1-1. D to F, Double mutant Ljrhl1-1 har1-1.

DISCUSSION

Root hair development has been extensively studied in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). Although a large number of root hair mutants have been identified in this model organism (Grierson et al., 2001), they have not been characterized in the context of nitrogen-fixing symbiosis since Arabidopsis is unable to successfully interact with Rhizobium. We describe here the wild-type L. japonicus root hair phenotype and the isolation and characterization of nine L. japonicus root hair mutants carrying lesions in various parts of the root hair developmental pathway(s). These mutant lines, representing 4 distinct loci, have been identified as suppressors, or partial suppressors, of the L. japonicus har1-1 hypernodulation phenotype, which by itself provides formal evidence for the essential role of wild-type root hairs during the L. japonicus-M. loti interaction.

Almost unrestricted nodulation in the genetic background of the har1-1 autoregulatory mutation offers the ability to observe the otherwise wild-type nodulation events in much greater numbers in comparison to wild-type plants (Wopereis et al., 2000). This feature has guided us through the evaluation of the nodulation phenotypes of the L. japonicus root hair mutants and was especially useful during the analysis of the Ljroothairless 1 mutant, where the initial root invasion events are rare.

On the cellular level, the various developmental changes in both the root epidermis (the epidermal program) and cortex (the cortical program) are among the earliest observable responses of the host plant toward the compatible NF-producing Rhizobium (Spaink, 1996; D'Haeze and Holsters, 2002). Our results show that the presence of root hairs is not required for the activation of the cortical program in L. japonicus, while it is essential for the efficient progression of the epidermal program.

The cortical program, defined by the initiation of root cortical cell divisions and subsequent organogenesis of NP (Guinel and Geil, 2002), is induced efficiently by a NF-producing strain of M. loti on roots of L. japonicus double mutant lines belonging to all four root hair mutant classes. With one notable exception, namely Ljvrh1-1 har1-1 (see below), abundant organogenesis of NP occurs within the first few days after inoculation with M. loti. Over a period of 3 to 6 weeks, the majority of these NP enlarged in size but remained uncolonized, indicative of a defect in the progression of bacterial invasion at the root epidermis.

The observation that the overall number of NP is decreased in the Ljrhl1-1 single mutant line carrying a functional HAR1 receptor kinase gene, as compared to the corresponding double mutant Ljrhl1-1 har1-1, suggests that, similar to wild-type plants, the organogenesis of NP is subjected to autoregulation in the Ljrhl1-1 mutant background. Thus, NP formation and their autoregulation in L. japonicus do not require root hairs. It is, however, intriguing that the number of developing NP is limited in the double mutant genetic background of Ljvrh1-1 har1-1. Unlike the other L. japonicus root hair mutants described above, the Ljvrh1-1 har1-1 develops significantly fewer NP that quickly become colonized by M. loti. At 21 dai, the nodulation phenotype of Ljvrh1-1 har1-1 resembles the corresponding wild-type phenotype of L. japonicus Gifu. Follow up experiments will be needed to fully understand the nature of the mechanism(s) that limits nodulation events in this particular mutant background.

In contrast to the normal progression of NP organogenesis, the events at the root epidermis were found to be significantly affected in the root hair mutants. This is reflected in the diminished ability of all classes of L. japonicus root hair mutants to develop nodules as compared to the har1-1 parental mutant line (nodule no.; see Fig. 5C). Nevertheless, the root hairs of petite, short, and variable root hair mutants support, to some extent, the infection process. At 21 dai, the root colonization in these mutant lines proceeded via ITs that originated at the developmentally hindered root hairs.

Although growth-terminating root hairs have been shown to be particularly susceptible to NF deformation activity (Esseling et al., 2003; Esseling and Emons, 2004), young growing root hairs were found to entrap the bacteria under soil-growth conditions (Kijne, 1992). Root hairs of petite, short, and variable root hair mutants proceed through different durations of the tip growth phase, which is destined for premature termination. With the exception of Ljvrh1-1 har1-1 (see above), longer tip growth phase correlates with greater numbers of infected nodules. It is possible that the duration of the tip growth phase and thus the particular physiological status of the growing root hair that enables response to NF and subsequent bacterial entrapment (Esseling and Emons, 2004) may be one defining factor of the mutant root hair susceptibility to M. loti infection. Other developmental factors, such as the ability to curl and the propensity to initiate and sustain IT growth, are also important determinants of root hair susceptibility. The detailed evaluation of these processes in the above described L. japonicus root hair mutant lines is required to fully correlate the various root hair phenotypes with the outcome of the symbiotic interactions.

For many legume species, including L. japonicus, root hairs are considered to be essential structures for the establishment of successful plant-microbe symbioses. The involvement of root hairs in the entrapment of bacteria, the subsequent initiation of root invasion (which commences as invagination of the root hair plasma membrane to give rise to an IT), and eventual colonization of nodule structure have been well documented (Gage, 2004). The nodulation phenotypes of the L. japonicus root hair mutants described above provide additional support for the significance of root hairs in bacterial invasion of the root tissue. However, Kawaguchi et al. (2002) reported the identification of the L. japonicus SLIPPERY mutant, which in spite of having very few root hairs, was able to develop a low number of colonized nodules. Although not investigated further, this observation led the authors to suggest that an alternative entry mechanism(s) into the L. japonicus root may have accounted for the nodulation phenotype of the SLIPPERY mutant (Kawaguchi et al., 2002).

We set out to test this hypothesis by performing a detailed analysis of the nodulation phenotype of the independently isolated L. japonicus root hairless Ljrhl1-1 mutant. The allelic relationship between SLIPPERY and Ljrhl1 mutants has yet to be established and a relevant complementation analysis is currently under way.

We show that, under the growth conditions used, Ljrhl1-1 is capable of interacting with M. loti and, given an extended period of time, is able to develop a large number of nitrogen-fixing nodules. Evidence is provided for the ability of M. loti to enter the nodule structure via a crack entry mechanism through the cortical surface of the NP. Furthermore, we show that in a NF-dependent manner, a partial complementation of the root hairless phenotype occurs. These de novo induced root hairs restore the root hair-dependent mode of infection, which proceeds through IT formation and leads to the colonization of the Ljrhl1-1 root by M. loti.

There exist several examples of alternate mechanisms of infection that do not require root hairs. Crack entry mechanisms that rely on intercellular breaching of the epidermal cell layer have been reported in several legume species (de Faria et al., 1988; Subba-Rao et al., 1995; Boogerd and van Rossum, 1997) as well as in the nonlegume Parasponia (Lancelle and Torrey, 1984). For example, in the semiaquatic S. rostrata, a close relative of L. japonicus, a crack entry mechanism at the sites of lateral root emergence is used as the principal mode of bacterial entry for nodule colonization under hydroponic conditions (Goormachtig et al., 2004a, 2004b). This mechanism manifests itself as the formation of pockets of bacteria embedded in the intercellular matrix that narrow down to intracellular infection threads prior to entering the plant cells (Sprent and Raven, 1992; Ndoye et al., 1994; Subba-Rao et al., 1995). Interestingly, in Chamaecytisus proliferus (tagasaste)-Bradyrhizobium sp. symbiosis, the initially developed infection threads abort prematurely within the root hairs. A crack entry through the intercellular space of the outer layers of the emerging nodule is used instead for colonization, without further participation of ITs (Vega-Hernandez et al., 2001).

The single example of root hair-independent invasion described in this work, where M. loti colonized cracks at the surface of the emerged nodule, and proceeded through intercellular infection and IT formation to enter the nodule structure, appears to combine features of both the A. caulinodans-S. rostrata and the bradyrhizobia-tagasaste symbioses. This type of root invasion by M. loti appears to be rare, even on plants lacking epidermal root hairs and in spite of the frequent occurrence of bacterial colonies on the nodule surface. The importance of this phenomenon in Lotus is unknown and needs further study. One possibility is that this mode of infection is important under conditions that inhibit root hair growth or susceptibility, such as is the case in S. rostrata and Neptunia plena (Goormachtig et al., 2004a, 2004b). Interestingly, it is possible that symbionts that are unable to initiate the normal epidermal infection events, but are capable of inducing NP formation, may be capable of infecting L. japonicus through this route. Both Stylosanthes and Arachis, which are infected via crack entry, exhibit less stringent requirements toward their microsymbiotic partners (Dart, 1977). In addition, Goormachtig et al. (2004a) report that while mutant bacteria producing unsubstituted NFs fail to form functional nodules though root hair-dependent infections, they are able to colonize nodules via intercellular entry at nearly wild-type levels.

It appears, nevertheless, that the successful colonization of Ljrhl1-1 roots proceeds mainly through NF-dependent de novo formation of both cortical and epidermal root hairs. NFs and related lipochitin oligosaccharides are known for their strong plant growth promoting effects (Dyachok et al., 2002; Souleimanov et al., 2002; Prithiviraj et al., 2003) and have been shown to cause root hair induction (Hai) on vetch (Vicia sativa subsp. nigra; Roche et al., 1991; Zaat et al., 1987, 1989; Tak et al., 2004), S. rostrata (Mergaert et al., 1993), and L. japonicus (van Spronsen et al., 2001). van Brussel et al. (1992) observed the induction of cortical root hair formation upon application of mitogenic NFs in the absence of bacteria. It was speculated that NF signaling causes localized weakening of the cell wall, which directs IT formation in the presence of bacteria or root hair formation in their absence (van Brussel et al., 1992; van Spronsen et al., 1994). In our experiments, nodule-associated (cortical) root hairs, and also nodule independent (epidermal) root hairs, evolved with bacteria present but in the absence of preexisting root hairs, suggesting that the context of the bacteria (i.e. whether or not it can interact with root hairs) may be important. This notion is supported by the observation that the nodF nodL double mutant of S. meliloti, which produces altered NF and is unable to induce formation of shepherd's crook or to initiate ITs when inoculated onto alfalfa seedlings, exerts abnormal activity in terms of inducing tip growth on trichoblasts and non-haired epidermal cells (Ardourel et al., 1994).

In vetch, non-mitogenic NFs are stronger inducers of Hai than are mitogenic NFs (Roche et al., 1991; Tak et al., 2004). Furthermore, mitogenic NFs have inhibitory effects on Hai in vetch (Tak et al., 2004) but seem not to inhibit (cortical) root hair formation on NP. The separate ontogeny and differential response to NFs of nodule-associated (cortical) hairs and epidermal root hairs prescribe two distinct classes of root hairs in legumes. Both cortical and epidermal derived root hairs in L. japonicus are NF inducible, a developmental process that does not require the LjROOTHAIRLESS 1 gene product. One intriguing possibility is that M. loti-produced NFs complement, at least partially, the lack of Ljrhl1-1 gene function. If this is indeed the case, the molecular cloning of Ljrhl gene, which has became increasingly possible through the rapidly advancing L. japonicus whole genome sequencing project (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/lotus), should provide important insight into the role NFs play in the initiation of root hairs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The Lotus japonicus root hair mutants were generated by chemical ethylmethanesulfonate mutagenesis of L. japonicus ecotype Gifu har1-1 homozygous seeds (Wopereis et al., 2000) following the previously detailed procedure (Szczyglowski et al., 1998).

Seeds were surface sterilized and germinated as described previously (Szczyglowski et al., 1998). All plants (unless otherwise stated) were maintained in a growth room under the 16-/8-h day/night regime, 200 to 250 μE s−1 m−2 light intensity at 22°C, and were occasionally watered with B&D nutrient solution (Broughton and Dilworth, 1971) containing a low concentration (0.5 mm) of KNO3.

Evaluation of Root Length and Root Hair Phenotypes

The root length phenotypes were evaluated by examining plants grown on vertically positioned agar plates as previously described (Wopereis et al., 2000). The plates were incubated in the dark at 22°C for 6 d. Root length measurements were taken every 24 h during this period. Mean value ± 95% confidence interval for each time point was calculated (n = 10).

For root hair length measurements, the agar plate condition were used as described for Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Muller and Schmidt, 2004), except that the subsequent incubation was as in Wopereis et al. (2000). Unstained root images of 5-d-old plants were captured with a DMX1200 digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo) connected to a SMZ 1500 microscope (Nikon) and root hair lengths were measured manually, using a standard ruler, directly from enlarged printed images. For each genotype, a total of 80 root hairs were measured from 8 plants. The average root hair length is expressed as a mean value ± 95% confidence interval.

Root hair number was evaluated using 42-d-old (10 plants/each genotype; Fig. 10) and 49-d-old (5 plants/each genotype; see text) plants, which were either uninoculated or inoculated (7 d after transfer to soil) with the appropriate Mesorhizobium loti strain (see Fig. 10 legend). All plants were grown in pots containing a 6:1 mixture of vermiculite and sand. Plants were carefully uprooted, washed, and the roots were cut into approximately 5-cm-long sections. The root sections were then mounted on slides and examined under 200× magnification using a Zeiss (Jena, Germany) Axioskop 2 plus microscope. For the 49-d-old plants, roots were fixed, stained for β-galactosidase reporter gene activity, and cleared as previously described (Wopereis et al., 2000) before root hair counts were made.

Evaluation of Symbiotic Phenotypes

L. japonicus seedlings were transferred from germination plates to pots containing a 6:1 mixture of vermiculite and sand and allowed to grow for an additional 7 d at which point they were inoculated with one of the following M. loti strains: NZP2235, NZP2235 carrying a hemA::LacZ reporter gene fusion, NZP2235 carrying a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene fusion (kind gift from J. Stougaard, Aarhus University, Denmark), R7A, and R7A nodC::Tn5 mutant incapable of producing NFs (kindly provided by C. Ronson and J. Sullivan, University of Otago, Australia).

Plants inoculated with M. loti strains R7A and R7A nodC were examined 28 dai using brightfield light microscopy (Nikon SMZ 1500).

For the histochemical analysis of β-galactosidase reporter gene activity, soil grown plants were analyzed 10, 21, and 42 dai. The number of NP and nodules were scored at 21 and 42 dai (10–15 plants/each genotype). Root sections were processed as described above for root hair counts of 49-d-old plants. The cleared specimens were first examined by brightfield light microscopy (Zeiss Axioskop 2 plus). In addition, the microscopic sections were generated by embedding specimens in 3% agarose and sectioning them to 25 to 35 μm using a VT1000S vibrating microtome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The images were taken using a DMX1200 digital camera attached to an inverted microscope (Leitz, Midland, Canada) and processed into montages using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 software (Mountain View, CA).

For evaluation of the nodulation phenotype of mature plants, the Ljrhl1-1 single mutants were transferred at 42 dai to pots containing a 4:4:1 mixture of Promix XP (Premier Horticulture, Quakertown, PA), medium size vermiculite (Therm-O-Rock East, New Eagle, PA), and Perlite (Therm-O-Rock East), respectively, and grown for an additional 82 d. During this period, the plants were supplemented twice with 1× Hoagland growth solution and watered as needed.

Microscopy

The root hair phenotypes of uninoculated wild-type and mutant roots were examined using light and cryoscanning electron microscopy. Images of live roots were taken directly from the agar plates. For SEM, 2-cm-long root segments, taken at approximately 0.5 cm from the root tip of 6-d-old sterile L. japonicus seedlings that were grown vertically on the surface of 100-cm2 agar plates (as described for evaluation of root length phenotype), were frozen in liquid N2 vapor for 2 to 3 min. Ice was sublimed at −70°C and the specimen sputter-coated with gold before being examined using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi S570 SEM) fitted with a cold stage.

For evaluation of wild type infection events, soil grown plants cultivated under the conditions described for evaluation of root symbiotic phenotype (see above) were analyzed 10 to 12 dai with M. loti strain NZP2235 carrying a GFP reporter gene fusion. Samples were counterstained with propidium iodide. Observations were made using a Leica confocal microscope DM IRE2 (Leica Microsystem).

The cytology and histology of nodules were examined by light microscopy. Nodules were fixed and embedded as described by Subba-Rao et al. (1995). Semithin sections (0.3–0.5 μm) were stained with toluidine blue solutions and examined by brighfield light microscopy.

Complementation and Genetic Segregation Analyses

The presence of the har1-1 allele in the double mutant lines was confirmed using a cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (Konieczny and Ausubel, 1993) marker specific to the critical mutation at the har1-1 locus (G→A substitution; Krusell et al., 2002), which destroys an Mva1 restriction site present in the wild-type allele. Briefly, primers (har1-1 forward, 5′-gattgtgattggaattgcact-3′; har-1 reverse, 5′- cgcaatcttatacctcatctcc-3′) were used to amplify a 463-bp fragment of the HAR1 gene, 10 μL of which was subsequently digested with 5 units of Mva1 enzyme for 1 h at 37°C. Mva1 digested products amplified from wild-type Gifu alleles yielding 369- and 94-bp restriction fragments; those amplified from the har1-1 mutant allele fail to digest.

Crossing the L. japonicus homozygous mutant lines with the wild-type Gifu parental line was performed using a manual emasculation and pollination procedure as described previously (Jiang and Gresshoff, 1997). Root hair and symbiotic characteristics of the resulting F1 and F2 generations were scored and used to determine the genetic basis of the observed phenotypes.

To examine allelism, complementation analyses were conducted by cross pollinating independent double homozygous mutant lines belonging to an individual phenotypic category and by evaluating their respective F1 hybrid phenotypes. In addition, the allelic crosses were performed between representative double mutant lines belonging to all different phenotypic categories in order to rule out the possible influence of an allelic variance on the observed phenotypic differences. The latter was especially important to unambiguously categorized Ljsrh1 and Ljvrh1, which were mapped to the same interval on L. japonicus chromosome 3. The progeny from one to four independent crosses were evaluated.

Mapping of Ljrhl1, Ljprh1, Ljsrh1, and Ljvrh1

To map the genes underlying the various root hair phenotypes, the double mutants (Ljrhl1-1 har1, Ljprh1-1 har1, Ljsrh1 har1, and Ljvrh1-1 har1) were crossed to the polymorphic mapping partner, L. japonicus ecotype MG20. DNA derived from F2 homozygous mutants showing the variable root hair (33 individuals), short root hair (17 individuals), petite root hair (23 individuals), and root hairless (19 individuals) phenotypes was prepared as follows. Approximately 25 mg of leaf tissue was pulverized in a 1.5-mL microtube using a hand drill and a plastic pestle in 2× cetyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide extraction buffer (2% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide [w/v], 100 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 20 mm EDTA, 1.4 m NaCl, and 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone [w/v]) and then centrifuged for 1 min at 14,000 rpm. The supernatant was then extracted once with an equal volume of chloroform and the DNA was precipitated with 2/3 volume of isopropanol and briefly dried before being resuspended in 0.25 mL of 10-mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The resulting DNA samples were analyzed using a selection of available simple sequence repeat markers (Sato et al., 2001; Nakamura et al., 2002; Asamizu et al., 2003; Kaneko et al., 2003). In addition, the following simple sequence repeat markers were used: TM0407, TM1419, TM0494, TM0696, TM0140, and JM001. The corresponding primer sequences are as follows: TM0407-F, 5′-aagctattgcatccactggg-3′; TM0407-R, 5′-actagggttcattctgtggc-3′; TM1419-F, 5′-gtctaatgatgtgggttggc-3′; TM1419-R, 5′-ggagctcaaatattcattacac-3′; TM0494-F, 5′-catagctgcaattccaagag-3′; TM0494-R, 5′-tttcgcttgagtcaatgtag-3′; TM0696-F, 5′-ttgaccctaacatgggaatc-3′; TM0696-R, 5′-tggacaaatgcatgacacac-3′; TM0140-F, 5′-ggaaatcaatttcgggaggc-3′; TM0140-R, 5′-tggacagtaataaatacattcg-3′; JM001-F, 5′-aaggaggaagggttttgcac-3′; and JM001-R, 5′-caggcctcaagctaaggaca-3′. All marker amplification reactions were carried out in a total volume of 50 μL containing: 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.4, 50 mm KCl and 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1 μm each primer, 200 μm of each dCTP, dATP, dCTP, and dGTP, 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 5 μL of template DNA. PCR reactions were performed using a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 machine (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with a single 4-min denaturation cycle at 94°C followed by 35 cycles (94°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; and 72°C, 1 min). PCR products were separated on 4% agarose gels in 0.5× Tris-borate/EDTA buffer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dario Bonneta for his constructive comments on the manuscript and Alex Molnar for his expert help with the preparation of the figures.

This work was supported by the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Crop Genomics Initiative and by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (grant no. 3277A01).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.104.057513.

References

- Ardourel M, Demont N, Debelle F, Maillet F, de Billy F, Prome J-C, Denarie J, Truchet G (1994) Rhizobium meliloti lipooligosaccharide nodulation factors: different structural requirements for bacterial entry into target root hair cells and induction of plant symbiotic developmental responses. Plant Cell 6: 1357–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asamizu E, Kato T, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Kaneko T, Tabata S (2003) Structural analysis of a Lotus japonicus genome. IV. Sequence features and mapping of seventy-three TAC clones which cover the 7.5 Mb regions of the genome. DNA Res 10: 115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuvaneswari TV, Bhagwat AA, Bauer WD (1981) Transient susceptibility of root cells in four common legumes to nodulation by rhizobia. Plant Physiol 68: 1144–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boogerd FC, van Rossum D (1997) Nodulation of groundnut by Bradyrhizobium: a simple infection process by crack entry. FEMS Microbiol Rev 21: 5–27 [Google Scholar]

- Broughton WJ, Dilworth MY (1971) Control of leghaemoglobin synthesis in snake beans. Biochem J 125: 1075–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart PJ (1977) Infection and development of leguminous nodules. In RWF Hardy, WS Silver, eds, A Treatise on Dinitrogen Fixation Section III Biology, Ed 1. John Wiley and Sons, New York, pp 367–472

- Denarie J, Debelle F, Prome J-C (1996) Rhizobium lipo-chitooligosaccharide nodulation factors: signaling molecules mediating recognition and morphogenesis. Annu Rev Biochem 65: 503–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Haeze W, Holsters M (2002) Nod factor structures, responses, and perception during initiation of nodule development. Glycobiology 12: 79R–105R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Faria SM, Hay GT, Sprent JI (1988) Entry of rhizobia into roots of Mimosa scabrella Bentham occurs between epidermal cells. J Gen Microbiol 134: 2291–2296 [Google Scholar]

- Dyachok JV, Wiweger M, Kenne L, Arnold S (2002) Endogenous nod-factor-like signal molecules promote early somatic embryo development in Norway spruce. Plant Physiol 128: 523–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esseling JJ, Emons AMC (2004) Dissection of Nod factor signalling in legumes: cell biology, mutants and pharmacological approaches. J Microsc 214: 104–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esseling JJ, Lhuissier FGP, Emons AM (2003) Nod factor-induced root hair curling. Continuous polar growth towards the point of nod factor application. Plant Physiol 132: 1982–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage DJ (2004) Infection and invasion of roots by symbiotic, nitrogen-fixing rhizobia during nodulation of temperate legumes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68: 280–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson S, Parker J, Kemp A (2001) Arabidopsis genes with roles in root hair development. J Plant Nutr 164: 131–140 [Google Scholar]

- Goormachtig S, Capoen W, James EK, Holsters M (2004. a) Switch from intracellular to intercellular invasion during water stress-tolerant legume nodulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 6303–6308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormachtig S, Capoen W, Holsters M (2004. b) Rhizobium infections: lessons from the versatile nodulation behaviour of water-tolerant legumes. Trends Plant Sci 9: 518–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinel FC, Geil RD (2002) A model for the development of the rhizobial and arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses in legumes and its use to understand the roles of ethylene in the establishment of these two symbioses. Can J Bot 80: 695–720 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Gresshoff PM (1997) Classical and molecular genetics of the model legume Lotus japonicus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 10: 59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Asamizu E, Kato T, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S (2003) Structural analysis of a Lotus japonicus genome. III. Sequence features and mapping of sixty-two TAC clones which cover the 6.7 Mb regions of the genome. DNA Res 10: 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi M, Imaizumi-Anruaku H, Koiwa H, Niwa S, Ikuta A, Syono K, Akao S (2002) Root, root hair, and symbiotic mutants of the model legume Lotus japonicus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 15: 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kijne JW (1992) The Rhizobium infection process. In G Stacey, HJ Evans, RH Burris, eds, Biological Nitrogen Fixation. Chapman and Hall, London, pp 349–398

- Konieczny A, Ausubel FM (1993) A procedure for mapping Arabidopsis mutations using co-dominant ecotype-specific PCR-based markers. Plant J 4: 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusell L, Madsen LH, Sato S, Aubert G, Genua A, Szczyglowski K, Duc G, Kaneko T, Tabata S, de Bruijn F, et al (2002) Shoot control of root development and nodulation is mediated by a receptor-like kinase. Nature 420: 422–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancelle SA, Torrey JG (1984) Early development of Rhizobium-induced root nodules of Parasponia rigida. I. Infection and early nodule initiation. Protoplasma 123: 6–37 [Google Scholar]

- Lhuissier FGP, De Ruijter NCA, Sieberer BJ, Esseling JJ, Emons AM (2001) Time course of cell biological events evoked in legume root hairs by Rhizobium nod factors: state of the art. Ann Bot (Lond) 87: 289–302 [Google Scholar]

- Limpens E, Franken C, Smit P, Willemse J, Bisseling T, Geurts R (2003) LysM domain receptor kinases regulating rhizobial Nod factor-induced infection. Science 302: 630–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EB, Madsen LH, Radutoiu S, Olbryt M, Rakwalska M, Szczyglowski K, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, et al (2003) A receptor kinase gene of the LysM type is involved in legume perception of rhizobial signals. Nature 425: 637–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergaert P, Van Montagu M, Prome JC, Holsters M (1993) Three unusual modifications, a D-arabinosyl, an N-methyl, and a carbamoyl group, are present on the Nod factors of Azorhizobium caulinodans strain ORS571. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 1551–1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Schmidt W (2004) Environmentally induced plasticity of root hair development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 134: 409–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Kaneko T, Asamizu E, Kato T, Sato S, Tabata S (2002) Structural analysis of a Lotus japonicus genome. II. Sequence features and mapping of sixty-five TAC clones which cover the 6.5-Mb regions of the genome. DNA Res 9: 63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndoye I, de Billy F, Vasse J, Dreyfus B, Truchet G (1994) Root nodulation of Sesbania rostrata. J Bacteriol 176: 1060–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura R, Hayash M, Wu GJ, Kouchi H, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Murakami Y, Kawasaki S, Akao S, Ohmori M, Nagasawa M, et al (2002) HAR1 mediates systemic regulation of symbiotic organ development. Nature 420: 426–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutman PS (1952) Studies on the physiology of nodule formation. III. Experiments on the excision of root tip and nodules. Ann Bot 16: 81–102 [Google Scholar]

- Penmetsa RV, Cook DR (1997) A legume ethylene-insensitive mutant hyperinfected by its Rhizobial symbiont. Science 275: 527–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prithiviraj B, Zhou X, Souleimanov A, Kahn WM, Smith DL (2003) A host-specific bacteria-to-plant signal molecule (Nod factor) enhances germination and early growth of diverse crop plants. Planta 216: 437–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Felle HH, Umehara Y, Gronlund M, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Sandal N, et al (2003) Plant recognition of symbiotic bacteria requires two LysM receptor-like kinases. Nature 425: 585–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riely BK, Ane JM, Penmetsa RV, Cook DR (2004) Genetic and genomic analysis in model legumes bring Nod-factor signalling to center stage. Curr Opin Plant Biol 7: 408–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche P, Debelle F, Maillet F, Lerouge P, Faucher C, Truchet G, Dénarié J, Promé J-C (1991) Molecular basis of symbiotic host specificity in Rhizobium meliloti: nodH and NodPQ genes encode the sulfation of lipo-oligosaccharide signals. Cell 67: 1131–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Kaneko T, Nakamura Y, Asamizu E, Kato T, Tabata S (2001) Structural analysis of a Lotus japonicus genome. I. Sequence features and mapping of fifty-six TAC clones which cover the 5.4 Mb regions of the genome. DNA Res 8: 311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souleimanov A, Prithiviraj B, Smith DL (2002) The major Nod factor of Bradyrizobium japonicum promotes early growth of soybean and corn. J Exp Bot 53: 1929–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaink HP (1996) Regulation of plant morphogenesis by lipo-chitin oligosaccharides. Crit Rev Plant Sci 15: 559–582 [Google Scholar]

- Sprent JI, Raven JA (1992) Evolution of nitrogen fixing symbioses. In G Stacey, RH Burris, HJ Evans, eds, Biological Nitrogen Fixation. Chapman and Hall, New York, pp 461–496

- Subba-Rao NA, Mateos PF, Baker D, Stuart Pankratz H, Palma J, Dazzo FB, Sprent JI (1995) The unique root-nodule symbiosis between Rhizobium and aquatic legume, Neptunia Natans (L.F.) Druce. Planta 190: 311–320 [Google Scholar]

- Szczyglowski K, Amyot L (2003) Symbiosis. Inventiveness by recruitment? Plant Physiol 131: 935–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczyglowski K, Shaw R, Wopereis J, Copeland S, Hamburger D, Kasiborski B, Dazzo F, Bruijn F (1998) Nodule organogenesis and symbiotic mutants of the model legume Lotus japonicus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 11: 684–697 [Google Scholar]

- Tak T, van Spronsen PC, Kijne JW, van Brussel AN, Boot KJM (2004) Accumulation of lipochitin oligosaccharides and NodD-activating compounds in an efficient plant-rhizobium nodulation assay. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 17: 816–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Brussel AAN, Bakhuizen R, van Spronsen PC, Spaink HP, Tak T, Lugtenberg BJJ, Kijne JW (1992) Induction of pre-infection thread structures in the leguminous host plant by mitogenic lipo-oligosaccharides of Rhizobium. Science 257: 70–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Brussel AAN, Tak T, Boot KJM, Kijne JW (2002) Autoregulation of root nodule formation: signals of both symbiotic partners studied in a split-root system of Vicia sativa subsp. Nigra. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 15: 341–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Spronsen PC, Bakhuizen R, van Brussel AA, Kijne JW (1994) Cell wall degradation during infection thread formation by the root nodule bacterium Rhizobium leguminosarum is a two-step process. Eur J Cell Biol 64: 88–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Spronsen PC, Gronlund M, Bras CP, Spaink HP, Kijne JW (2001) Cell biological changes of outer cortical root cells in early determinate nodulation. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14: 839–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Hernandez MC, Perez-Galdona R, Dazzo FB, Jarabo-Lorenzo A, Alfayate MC, Leon-Barrios M (2001) Novel infection process in the indeterminate root nodule symbiosis between Chamaecytisus proliferus (tagasaste) and Bradyrhizobium sp. New Phytol 150: 707–721 [Google Scholar]

- Wopereis J, Pajuelo E, Dazzo FB, Jiang QY, Gresshoff PM, de Bruijn FJ, Stougaardn J, Szczyglowski K (2000) Short root mutant of Lotus japonicus with a dramatically altered symbiotic phenotype. Plant J 23: 97–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaat SAJ, van Brussel AAN, Tak T, Lugtenberg BJJ, Kijne JW (1989) The ethylene inhibitor aminoethoxyvinylglycine restores normal nodulation by Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar. viciae on Vicia sativa subsp. nigra by suppressing the ‘thick and short roots’ phenotype. Planta 177: 141–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaat SAJ, van Brussel AAN, Tak T, Pees E, Lugtenberg BJJ (1987) Flavonoids induce Rhizobium leguminosarum to produce nodDABC gene-related factors that cause thick, short roots and root hair responses on common vetch. J Bacteriol 169: 3388–3391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.