Abstract

To understand the molecular basis for the dramatic functional synergy between transcription factors that bind to the minimal T-cell receptor α enhancer (Eα), we analyzed enhancer occupancy in thymocytes of transgenic mice in vivo by genomic footprinting. We found that the formation of a multiprotein complex on this enhancer in vivo results from the occupancy of previously identified sites for CREB/ATF, TCF/LEF, CBF/PEBP2, and Ets factors as well as from the occupancy of two new sites 5′ of the CRE site, GC-I (which binds Sp1 in vitro) and GC-II. Significantly, although all sites are occupied on a wild-type Eα, all sites are unoccupied on versions of Eα with mutations in the TCF/LEF or Ets sites. Previous in vitro experiments demonstrated hierarchical enhancer occupancy with independent binding of LEF-1 and CREB. Our data indicate that the formation of a multiprotein complex on the enhancer in vivo is highly cooperative and that no single Eα binding factor can access chromatin in vivo to play a unique initiating role in its assembly. Rather, the simultaneous availability of multiple enhancer binding proteins is required for chromatin disruption and stable binding site occupancy as well as the activation of transcription and V(D)J recombination.

Gene regulation in eukaryotic cells is accomplished through the interplay between transcription factors and chromatin. Chromatin structure is, in general, inhibitory for transcriptional activation and plays a critical role in gene regulation because it prevents transcription factors from accessing their binding sites within cis-regulatory regions in inappropriate tissues and at inappropriate times during development (12, 35, 48). Active cis-regulatory regions are usually mapped as DNase I-hypersensitive sites that result from a local disruption of the canonical nucleosome structure (19). Some transcription factors, including steroid hormone receptors, Pho4, GAL4 and its derivatives, and GAGA factor, seem capable of accessing their binding sites in chromatin and initiating alterations in the structure and stability of underlying or adjacent nucleosomes that result in the generation of these accessible regions (2, 38). The ability of these factors to access nucleosomal DNA depends critically on the positioning of their binding sites with respect to the nucleosome. Initial factor binding facilitates the loading of additional factors that otherwise could not access their binding sites in chromatin, leading ultimately to transcriptional activation. Two classes of enzymatic activities may be recruited by specific transcription factors to facilitate nucleosome remodeling and transcription factor binding: ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes and histone acetyltransferases (34, 63, 67).

The minimal human T-cell receptor (TCR) α enhancer (Eα) has been the subject of intensive analysis and represents an excellent paradigm for the coordinated assembly of and synergistic transcriptional activation by a multiprotein complex on a cis-regulatory element. This enhancer was initially characterized as a 116-bp segment of DNA that, on the basis of in vitro DNase I footprinting, includes two protein binding regions (Tα1 and Tα2) (30). The minimal Eα is sufficient to activate transcription in transiently transfected T-cell lines (30) and V(D)J recombination in thymocytes of transgenic mice (53). It contains binding sites for members of the CREB/ATF, TCF/LEF, CBF/PEBP2, and Ets families of transcription factors, all of which are critical for enhancer activity (17, 29, 30, 53, 59, 64, 65). The mechanisms by which these factors act in synergy to activate both transcription and V(D)J recombination in vivo have yet to be fully elucidated.

A major focus of recent studies has been the role of TCF/LEF family transcription factors in the assembly of the multiprotein complex on Eα. TCF/LEF transcription factors are members of the sequence-specific class of high-mobility-group (HMG) proteins (7). These proteins are known as “architectural” transcription factors because of their ability to introduce a sharp bend in DNA (15, 39). This property has been suggested to facilitate the assembly of a transcriptionally active multiprotein complex by promoting interactions between proteins bound on either side of the bend (15, 17, 20, 66). TCF/LEF factors cannot transactivate transcription by themselves but can do so either in the context of a specific arrangement of additional transcription factor binding sites (51, 55, 59, 62, 65) or by interaction with the transcriptional coactivator β-catenin (5, 51, 60). Context-dependent transcriptional activation results in part from DNA bending induced by the HMG domain (17, 42) but also depends on a distinct activation domain in a manner that is independent of DNA bending (8, 16, 55). The latter suggests that TCF/LEF, in addition to promoting protein-protein interactions through DNA bending, directly contacts specific proteins via its context-dependent activation domain. One such protein, ALY, is a context-dependent coactivator that appears to facilitate functional interactions with other factors bound to the minimal Eα (6). β-Catenin interacts with a distinct region of TCF/LEF factors and stimulates transcription through TCF/LEF binding sites (3, 5, 31, 44, 51, 60) but does not appear to regulate the minimal Eα (3). In some cases, a functional role for TCF/LEF is only apparent in chromatin-integrated templates (23, 55), a result which has led to the suggestion that its primary role may be to recruit chromatin-remodeling complexes (34).

The in vitro assembly of a multiprotein complex on the minimal Eα has been studied in two laboratories with both naked DNA and in vitro-reconstituted chromatin templates (17, 42). In studies with naked DNA templates, LEF-1 and CREB/ATF proteins were shown to bind independently. CBF/PEBP2 and Ets-1 were shown to bind cooperatively, and LEF-1-induced DNA bending and helical phasing of the CRE site relative to other sites were both found to be important to further stabilize the binding of CBF/PEBP2 and Ets-1 (17). It was suggested that stable binding of CBF/PEBP2 and Ets-1 required LEF-1-induced DNA bending to facilitate the interaction of ATF proteins and Ets-1. More recently, different results were obtained with in vitro-reconstituted chromatin templates (42). In this case, LEF-1 stabilized the binding of CBF/PEBP2 and Ets-1, but this stabilization did not depend on CREB, which bound independently. Nevertheless, both sets of in vitro experiments suggested stepwise, or hierarchical, assembly of transcription factors onto the minimal Eα, with a central organizing role for LEF-1.

In this study, we have analyzed transcriptional activity and transcription factor occupancy of chromosomally integrated wild-type and mutant versions of the minimal Eα in vivo by using thymocytes of transgenic mice. We show that the minimal Eα can direct transcription in vivo and that transcription is dependent on intact binding sites for TCF/LEF and Ets factors. Importantly, we found that although all binding sites are occupied on the wild-type enhancer, all binding sites are unoccupied on enhancers with either a mutated TCF/LEF site or a mutated Ets site. Our in vivo results therefore support a novel model for the highly cooperative assembly of a multiprotein complex on the minimal Eα in which no single enhancer binding factor can access its binding site in native chromatin to potentially serve as an initiator, or master regulator, of enhancer occupancy. Highly cooperative assembly may explain both the dramatic functional synergy between Eα binding proteins and the tight regulation of TCR α gene expression in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Northern blotting.

Total RNA was isolated from unfractionated thymocytes of 4-week-old transgenic mice as described previously (11). RNA samples (8 μg) were electrophoresed through a 1.5% agarose gel containing 2.2 M formaldehyde and transferred to a nylon membrane (Micron Separations, Westboro, Mass.). Cδ transcripts were detected with a 32P-labeled Cδ probe (21), and RNA loading was assessed with a 32P-labeled glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase probe.

DMS and DNase I treatments.

Unfractionated thymocytes from 4-week-old transgenic mice were used for dimethyl sulfate (DMS) and DNase I analyses. Thymocytes isolated from a single mouse were used for both in vivo and in vitro treatments performed in parallel. DMS treatments were performed as described previously (45).

For in vivo DNase I treatment, thymocytes were permeabilized with Nonidet P-40 (52) or lysolecithin (49). Briefly, 5 × 107 to 1 × 108 cells were resuspended and incubated for 1 min at 37°C in 1 ml of preequilibrated 150 mM sucrose–80 mM KCl–5 mM K2HPO4–5 mM MgCl2–0.5 mM CaCl2–35 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) containing 0.05% (wt/vol) lysolecithin or 0.2% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40. After cell permeabilization, 9 ml of 150 mM sucrose–80 mM KCl–5 mM K2HPO4–5 mM MgCl2–2 mM CaCl2–35 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and 15 to 120 U of DNase I (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Freehold, N.J.) were added for a 5-min incubation at 23°C. Cells were then centrifuged at 4°C and lysed by incubation in 3 ml of lysis buffer (45) containing 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.2 mg of proteinase K per ml for 5 to 16 h at 37°C. Genomic DNA from DNase I-treated and untreated cells was obtained as described previously (45). DNA samples were treated with RNase A (100 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C followed by proteinase K (200 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C. DNA was then serially extracted with phenol, phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1), and ethyl ether and precipitated by adding a 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 7.0) and 2 volumes of cold ethanol. Pellets were washed in 75% ethanol and resuspended at 1 to 2 μg/ml in 1 mM EDTA–10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5).

For in vitro DNase I treatment, 50 μl of DNA solution was diluted by the addition of 400 μl of H2O and 50 μl of 100 mM MgCl2–20 mM CaCl–500 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), and DNase I (0.0225 to 0.045 U) was added for a 30- to 90-s incubation at 23°C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 175 μl of 143 mM EDTA (pH 8.0)–7.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. DNA was then extracted and precipitated as described above.

LM-PCR.

DMS- and DNase I-treated DNA was subjected to ligation-mediated PCR (LM-PCR) as described previously (45). The oligonucleotides used for the analysis of the top strand were I-NC (5′GCTGAGAAGCTCAACTAAAAGACTG), II-NC (5′CTGATTCTGTTTCAGTCACTCAGGGC), and III-NC (5′CTGTTTCAGTCACTCAGGGCAGGAAAC). Those used for the analysis of the bottom strand were P1α (5′CAAGGAGACAGAGTATTACAGATG), P2(α) close (5′GATCCGTTGGGGGCTGGG), and P3(α)close (5′GTTGGGGGCTGGGGCGGT). The asymmetric linker was identical to that previously described by Mueller et al. (45).

EMSA.

Preparation of Jurkat cell nuclear extract, radiolabeling of binding site probes with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I and [α-32P]dCTP (ICN Radiochemicals, Irvine, Calif.), and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed as described previously (26, 27, 50). Binding reaction mixtures for analyzing Jurkat cell nuclear extract contained 2.2 μg of extract, 2 μg of dI-dC, and 5 μg of bovine serum albumin. Binding reaction mixtures for analyzing pure Sp1 contained 0.1 U of human recombinant Sp1 (Promega, Madison, Wis.), 0.5 μg of dI-dC, and 10 μg of bovine serum albumin. Anti-Sp1 serum was kindly provided by J. Horowitz (Duke University, Durham, N.C.), and normal rabbit serum was obtained from Dako, Carpinteria, Calif.

Plasmids.

To generate Tα1,2-Vδ1-CAT, the Tα1,2 fragment of Eα was excised from plasmid Eα0.7 (30) by digestion with BstXI and DraI, blunt ended by treatment with T4 polymerase, and ligated to XbaI-digested, Klenow fragment- and phosphatase-treated Vδ1-CAT (50). With this plasmid as a template, the Del GC-I and Del GC-I+II enhancer fragments were obtained by PCR with oligonucleotide 5′-GGGTCTAGACTCCCATTTCCATGACGTCA-3′ or 5′-GGGTCTAGAGGTCCCCTCCCATTTCCATG-3′ in conjunction with Vδ1 promoter oligonucleotide 5′-GAGAGGTAGCCATGCTCT-3′. PCR products were digested with BamHI and XbaI and ligated to BamHI- and XbaI-digested, phosphatase-treated Vδ1-CAT. Construct structure was confirmed by dideoxynucleotide sequence analysis.

Transient transfections and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase assays.

The human leukemia T-cell line Jurkat was cultured and transfected with CsCl-purified plasmid DNA as described previously (27). pRSV-luciferase (0.2 μg) was cotransfected with test plasmids to control for transfection efficiency. Luciferase activity was measured with a luciferase assay system (Promega). For chloramphenicol acetyltransferase assays, the acetylation of [14C]chloramphenicol (Dupont-New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.) was assayed as described previously (26) and quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

RESULTS

The minimal Eα can activate transcription in vivo.

cis-regulatory elements such as enhancers and promoters determine the developmental activation of V(D)J recombination within the TCR and immunoglobulin loci (57) by modulating chromatin structure so as to provide local accessibility to the recombinase machinery (43, 58). We previously studied enhancer control of V(D)J recombination in transgenic mice containing a chromosomally integrated, unrearranged human TCR δ gene minilocus (37). This construct is composed of germ line V, D, J, and C gene segments, with test enhancers inserted between J and C (Fig. 1). The initial V-to-D step of transgene rearrangement occurs in an enhancer-independent fashion, whereas the second step of transgene rearrangement, VD to J, depends critically upon the presence of a functional enhancer between J and C (28, 37, 53). This behavior reflects the fact that V and D segment accessibility is maintained even in the absence of an enhancer, whereas J segment accessibility is provided by the enhancer (43).

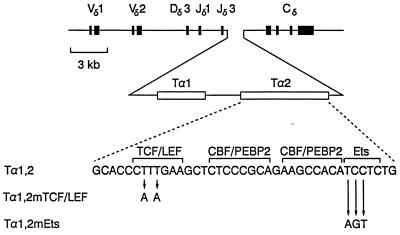

FIG. 1.

Structures of transgenic minilocus constructs. Human TCR δ gene minilocus constructs containing wild-type or mutant versions of the minimal Eα were previously described (53). Solid boxes represent exons, and open boxes represent protein binding sites.

We recently showed that the 116-bp minimal Eα is competent to activate the enhancer-dependent step of V(D)J recombination in this system and that intact binding sites for TCF/LEF and Ets family transcription factors are essential for its activity (53). In the present study, we analyzed transcription and enhancer occupancy in 10 previously studied lines of transgenic mice that included either the wild-type minimal Eα (Tα1,2 lines T2, T3, T5, and T7), the minimal Eα with a mutated TCF/LEF binding site (Tα1,2mTCF/LEF lines JI, JJ, and JK), or the minimal Eα with a mutated Ets binding site (Tα1,2mEts lines JN, JO, and JR) (Fig. 1 and Table 1). In our previous study (53), we found that the enhancer-independent V-to-D step and the enhancer-dependent VD-to-J step of transgene rearrangement both occurred in Tα1,2 lines T2, T5, and T7 but did not occur in Tα1,2 line T3 (Table 1). In all lines containing mutated enhancers, the enhancer-independent V-to-D rearrangement step occurred, but the enhancer-dependent VD-to-J step did not. We previously suggested that the absence of both VD and VDJ rearrangements in line T3 reflects transgene integration into an inhibitory site in chromatin.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of transgenic lines used in this study

| Construct | Line | Transgene copy number in thymus DNAa | Rearrangementb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VD | VDJ | |||

| Tα1,2 | T2 | 4 | + | + |

| T3 | 1 | − | − | |

| T5 | 1 | + | + | |

| T7 | 2 | + | + | |

| Tα1,2mTCF/LEF | JI | 2 | + | − |

| JJ | ND | + | − | |

| JK | 3 | + | − | |

| Tα1,2mEts | JN | 1 | + | − |

| JO | 3 | + | − | |

| JR | 4 | + | − | |

Assessed on slot blots. ND, not determined.

VDJ recombination phenotypes, as judged by PCR analysis of VD and VDJ rearrangement products, were previously determined (53). +, rearrangement; −, no rearrangement.

To determine whether the minimal Eα directs transcription as well as V(D)J recombination in a chromosomally integrated context, we analyzed Cδ-containing mRNA transcripts in transgenic thymocytes by Northern blotting (Fig. 2). Previous studies identified four major transcripts originating from the endogenous human TCR δ gene, two differentially polyadenylated transcripts originating from VDJ rearranged templates, and two differentially polyadenylated transcripts originating from germ line templates (21). Corresponding transcripts originating from VDJ rearranged and unrearranged templates were readily detected in thymocytes of Tα1,2 lines T2, T5, and T7 but were not detected in line T3. Furthermore, these transcripts were undetectable in thymocytes of Tα1,2mTCF/LEF and Tα1,2mEts transgenic mice. These differences are not readily attributable to differences in transgene copy number, as the different lines only varied by from one to four copies of the minilocus in transgenic thymocytes (Table 1). Therefore, these data, in conjunction with our previous results (53), indicate that the minimal Eα can activate both transcription and V(D)J recombination in vivo and that TCF/LEF and Ets binding sites are critical for both processes. The ability of the enhancer to activate transcription correlates precisely with its ability to activate V(D)J recombination in the various lines.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of transgenic minilocus transcription by Northern blotting. Thymocyte RNA samples were analyzed on Northern blots hybridized with 32P-labeled Cδ and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase probes. Filled and open arrowheads indicate differentially polyadenylated transcripts originating from VDJ rearranged and germ line templates, respectively.

Analysis of wild-type minimal Eα occupancy in vivo by genomic footprinting.

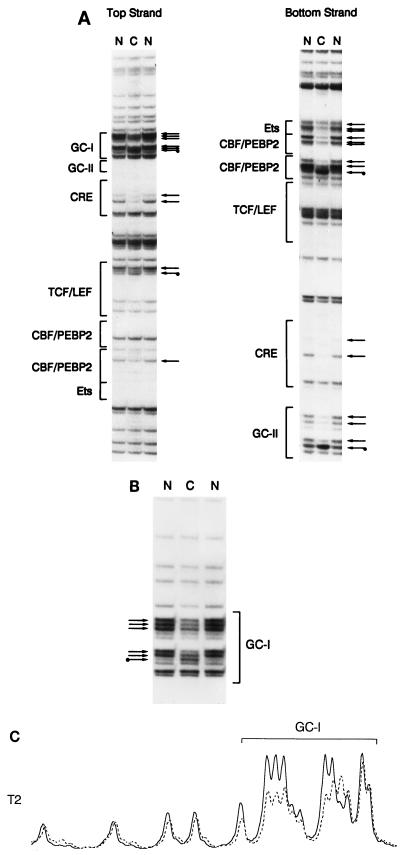

To investigate the molecular basis for minimal Eα function in vivo, we analyzed the occupancy of wild-type and mutant versions of the enhancer in thymocytes of transgenic mice by genomic footprinting with DMS as a chemical probe. This approach is widely used for genomic footprinting because living cells are permeable to DMS and DNA wound over nucleosomal core histones is freely accessible to react with it. We treated both intact thymocytes and purified thymocyte DNA with DMS to methylate guanines at the N7 position, cleaved DNA from both treatment regimens at methylated guanines by using piperidine, and performed LM-PCR as described by Mueller et al. (45) to visualize cleavage products. Analysis of both strands of the wild-type minimal Eα in total thymocytes of Tα1,2 transgenic line T2 is presented in Fig. 3. Identical footprints were obtained with Tα1,2 transgenic lines T5 and T7 (see Fig. 7A and B; also data not shown). Occupancy of the CRE site was clearly visualized as two protected guanines on the top strand and two protected guanines on the bottom strand (Fig. 3A). Occupancy of the upstream CBF/PEBP2 binding site was detected as two protected guanines and one hypersensitive guanine on the bottom strand, whereas occupancy of the downstream CBF/PEBP2 binding site was detected as one protected guanine on the top strand and three protected guanines on the bottom strand. Occupancy of the Ets binding site was detected as three protected guanines on the bottom strand. TCF/LEF binding is not easy to detect with DMS as a probe, because TCF/LEF primarily contacts DNA in the minor groove (17, 39, 61). However, we detected a weakly protected guanine and a hypersensitive guanine at one end of the TCF/LEF binding site on the top strand. These changes are presumably a consequence of TCF/LEF binding because purified LEF-1 protects these bases from DNase I digestion (14, 17, 59).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of in vivo occupancy of the wild-type minimal Eα by genomic footprinting. Transgenic thymocyte DNA from the Tα1,2 line T2 was methylated with DMS either as naked (N) DNA in vitro or as chromosomal (C) DNA in intact cells in vivo. Methylated DNA samples were treated with piperidine and subjected to LM-PCR. Protected guanines are indicated by plain arrows, and hypersensitive guanines are indicated by tagged (with a dot) arrows. Protein binding sites are indicated by brackets. (A) Top- and bottom-strand analyses of the minimal Eα. (B) Higher-resolution top-strand analysis of the GC-I box. (C) PhosphorImager scan of top-strand analysis of the GC-I box. Solid line, naked DNA; broken line, chromosomal DNA.

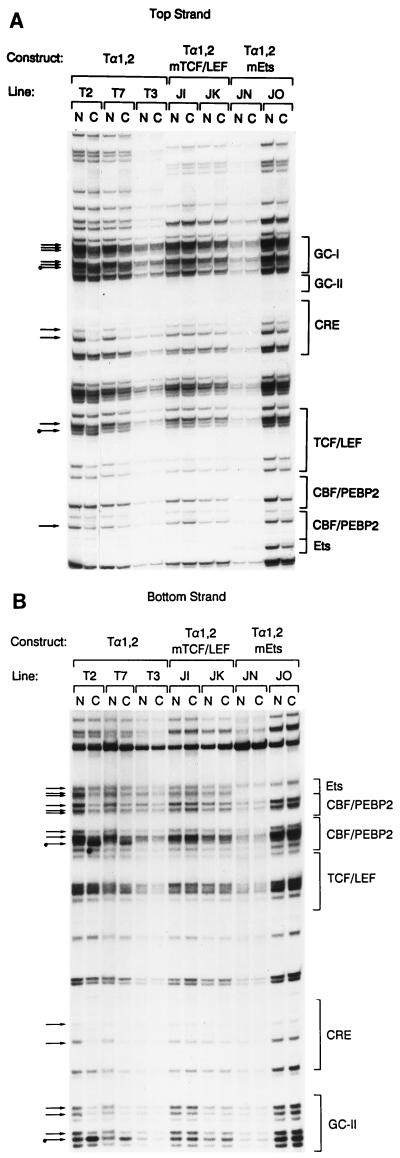

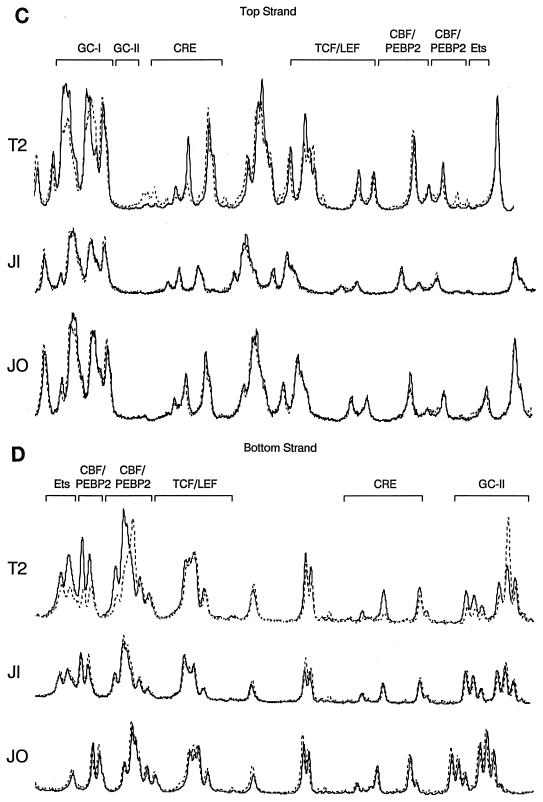

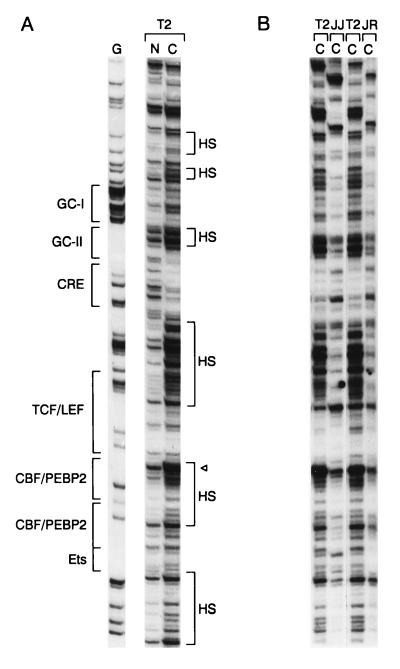

FIG. 7.

The minimal Eα is unoccupied in vivo in the absence of either TCF/LEF or Ets binding. Transgenic thymocyte DNA samples were analyzed by genomic footprinting as naked (N) DNA in vitro or chromosomal (C) DNA in vivo. Protected guanines are indicated by plain arrows, and hypersensitive guanines are indicated by tagged (with a dot) arrows. Protein binding sites are indicated by brackets. (A and B) Top-strand and bottom-strand analyses. (C and D) PhosphorImager scans of top-strand and bottom-strand analyses. Solid lines, naked DNA; broken lines, chromosmal DNA.

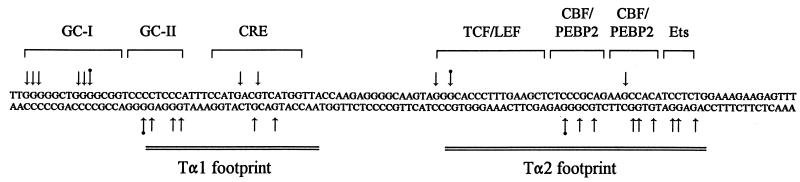

In addition to these previously characterized binding sites within the enhancer, we detected two other sites. One of these was not detected by previous in vitro DNase I footprinting (30). It is defined by five protected guanines and one hypersensitive guanine on the top strand, upstream of the CRE site (Fig. 3A; Fig. 3B shows a higher-resolution view). The sequence of this new site is GGGGGCTGGGGCGG, and we refer to it as the GC-I box. The second binding site is defined by strong protection of three guanines and hypersensitivity at another guanine on the bottom strand, between the GC-I box and the CRE site (Fig. 3A). This site is included in the Tα1 footprint initially detected by in vitro DNase I footprinting (30) (see Fig. 4). Its sequence is CCCCTCCC, and we refer to it as the GC-II box.

FIG. 4.

Summary of protected and hypersensitive guanines within the minimal Eα. Protected guanines are indicated by plain arrows, and hypersensitive guanines by tagged (with a dot) arrows. Factor binding sites are indicated by brackets. The Tα1 and Tα2 regions defined by in vitro footprinting (30) are indicated by double lines. Protection ranged from 30 to 80%, as quantified by PhosphorImager analysis.

Our qualitative assessments of the various protected and hypersensitive guanine residues were confirmed by quantitative analyses with a PhosphorImager (Fig. 3C; see also Fig. 7C and D) and are summarized in Fig. 4. Protection ranged from 30 to 80% at different guanines. These levels of protection are typical of those observed in other studies in which homogeneous cell populations were examined (9, 13, 33, 41, 46) and are therefore consistent with the minimal Eα being occupied in the majority of transgenic thymocytes.

Sp1 binds specifically to the functionally relevant GC-I box.

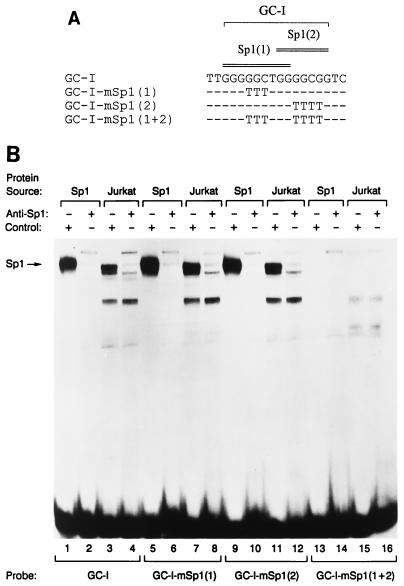

The GC-I box appears to contain two overlapping binding sites for Sp1, denoted Sp1(1) and Sp1(2) (Fig. 5A). Of these, the Sp1(1) site is occupied in vivo, whereas the Sp1(2) is not (Fig. 3A and B and 4). The characteristics of the footprint over the Sp1(1) site, with several protected guanines followed by a hypersensitive guanine at the end of the binding site, are typical of Sp1 binding, as reported previously (10, 41, 69). In order to investigate whether Sp1 can bind to the GC-I box, we used wild-type and mutant double-stranded GC-I oligonucleotides in EMSA (Fig. 5). Incubation of recombinant human Sp1 protein with a radiolabeled double-stranded GC-I oligonucleotide in the presence of a control antiserum yielded a single protein-DNA complex (Fig. 5B, lane 1). The same complex was formed in the presence of a labeled GC-I oligonucleotide with a mutation in the Sp1(1) site [GC-I-mSp1(1)] (Fig. 5B, lane 5) or a mutation in the Sp1(2) site [GC-I-mSp1(2)] (lane 9) but was not formed in the presence of an oligonucleotide with mutations in both sites [GC-I-mSp1(1+2)] (lane 13). That this complex indeed contained Sp1 was confirmed by the fact that the formation of the complex was dramatically inhibited by preincubation of proteins with an anti-Sp1 serum (Fig. 5B, lanes 2, 6, and 10). Thus, both the Sp1(1) and the Sp1(2) sites can serve as binding sites for purified Sp1.

FIG. 5.

In vitro binding of Sp1 to the GC-I box. (A) Wild-type and mutant GC-I boxes were tested. The actual binding site probes used included flanking BamHI overhangs to facilitate radiolabeling. (B) Radiolabeled binding site probes were incubated with pure Sp1 protein or Jurkat cell nuclear extracts in the presence of a control serum or an anti-Sp1 rabbit serum. DNA-protein complexes were resolved by electrophoresis. The Sp1-containing DNA-protein complex is marked.

To determine whether these sites could bind Sp1 from T-cell nuclear extracts, we incubated the labeled GC-I oligonucleotide with nuclear extracts from the leukemia T-cell line Jurkat. Several complexes were detected in the presence of a control antiserum (Fig. 5B, lane 3). The most prominent of these displayed the same mobility as the complex formed with recombinant Sp1 (compare lanes 1 and 3 of Fig. 5B), and its formation was inhibited by the anti-Sp1 serum (lane 4). Identical results were obtained with labeled GC-I-mSp1(1) and GC-I-mSp1(2) oligonucleotides (Fig. 5B, lanes 7, 8, 11, and 12). However, this complex was not formed by incubation with labeled GC-I-mSp1(1+2) oligonucleotide (Fig. 5B, lane 15). Thus, Sp1 is the predominant protein in T-cell nuclear extracts that binds to the GC-I box. Because none of the other complexes detected with the GC-I oligonucleotide were affected by the anti-Sp1 serum, they probably do not contain Sp1 (Fig. 5B, lanes 3 and 4). However, the fact that they were also detected by the GC-I-mSp1(1) and GC-I-mSp1(2) oligonucleotides but not by the GC-I-mSp1(1+2) oligonucleotide suggests that they have a sequence specificity that is similar to that of Sp1 (Fig. 5B, lanes 7, 11, and 15). Their identities are unclear at present.

Our results argue against simultaneous occupancy of the two Sp1 sites on a wild-type GC-I box, because the mobility of the Sp1 complex formed with the GC-I probe (containing two Sp1 sites) was identical to the mobility of the Sp1 complexes formed with the GC-I-mSp1(1) and GC-I-mSp1(2) probes (containing only one Sp1 site each). In addition, cross-competition experiments indicated that Sp1 binds with a higher affinity to the Sp1(1) site than to the Sp1(2) site (data not shown). Both of these results are consistent with the genomic footprinting experiments, which revealed occupancy of only the Sp1(1) site in vivo.

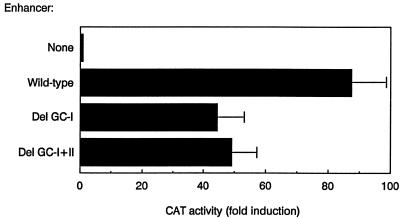

In order to evaluate the functional significance of protein binding to the GC-I and GC-II boxes, two minimal Eα deletion mutants were generated. In one, the GC-I box [containing both the Sp1(1) and the Sp1(2) sites] was deleted (Del GC-I), and in the other, both the GC-I and the GC-II boxes were deleted (Del GC-I+II). The wild-type and mutant minimal Eα’s were subcloned upstream of the Vδ1 promoter in the enhancer-dependent test construct Vδ1-CAT, and plasmids were transiently transfected into Jurkat cells to measure their activities (Fig. 6). Strikingly, both mutants displayed about 50% the activity of the wild-type enhancer. Hence, the GC-I box is functionally relevant, whereas the GC-II box is either inert, active only in the context of the GC-I box, or functionally redundant with other elements of the minimal enhancer. We conclude that an Sp1 site is occupied in vivo in a functionally relevant GC-I box within the minimal Eα.

FIG. 6.

Transcriptional activation by wild-type and mutant versions of the minimal Eα. Enhancer fragments were cloned upstream of the Vδ1 promoter in plasmid Vδ1-CAT. Test constructs were transfected along with an internal control plasmid into Jurkat cells, and normalized values for percentages of chloramphenicol acetylation were averaged and expressed as fold induction relative to Vδ1-CAT. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation for 5 to 12 determinations. CAT, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase.

The minimal Eα is unoccupied in vivo in the absence of either TCF/LEF or Ets binding.

Our data indicate that TCF/LEF and Ets factors function in a highly synergistic fashion to activate both V(D)J recombination and transcription within the minilocus construct in vivo. To investigate the molecular basis for functional synergy, we compared the in vivo occupancy of wild-type and mutant enhancers by genomic footprinting. Wild-type Tα1,2 lines T2, T5, and T7 yielded identical footprint patterns (Fig. 7A and B and data not shown), indicating that the wild-type enhancer was fully occupied in these lines. However, no footprints were detected for Tα1,2 line T3. The lack of enhancer occupancy in line T3 correlates with the absence of transcription (Fig. 2) and the absence of even enhancer-independent V-to-D rearrangement events in this line (53), supporting our contention that the transgene is integrated into an inhibitory site in chromatin that prevents factor access.

Genomic footprinting analysis of lines carrying mutated enhancers (Tα1,2mTCF/LEF lines JI and JK and Tα1,2mEts lines JN and JO) indicated that all binding sites were unoccupied in each line. These qualitative assessments of enhancer occupancy were confirmed by a quantitative analysis with a PhosphorImager (Fig. 7C and D). The lack of enhancer occupancy is not, as in line T3, secondary to integration into an inhibitory site in chromatin that prevents factor access because, unlike in line T3, enhancer-independent V-to-D rearrangement proceeds quite efficiently in the lines carrying mutant enhancers (53). Therefore, our data indicate that in the absence of either TCF/LEF binding or Ets binding, none of the other binding sites within the minimal Eα can be loaded in vivo. We conclude that no single factor can occupy its site within the minimal Eα and that enhancer occupancy is highly cooperative in vivo.

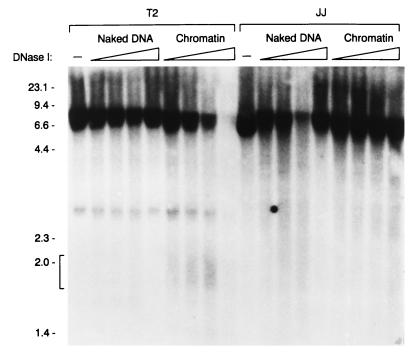

Enhancer occupancy induces a local change in chromatin structure.

We examined whether transcription factor occupancy of the minimal Eα influences local chromatin structure by measuring DNase I hypersensitivity in an area of 8 kb surrounding the enhancer. Genomic DNA of transgenic thymocytes from Tα1,2 line T2, Tα1,2mTCF/LEF line JJ, and Tα1,2mEts line JR was analyzed following DNase I treatment either as naked DNA in vitro or as chromatin in permeabilized cells. DNase I-treated DNA was subjected to SacI digestion and was analyzed by Southern blotting with a radiolabeled Jδ3 fragment as a probe. Comparison of DNase I-digested naked DNA and chromatin revealed a DNase I-hypersensitive region of 200 to 300 bp over the wild-type enhancer in line T2 chromatin (Fig. 8). No such hypersensitivity was detected over the mutant enhancers in line JJ and JR chromatin (Fig. 8 and data not shown), arguing that the disruption of chromatin structure over the enhancer is dependent on full enhancer occupancy.

FIG. 8.

Local chromatin disruption by the wild-type minimal Eα. Transgenic thymocyte DNAs from wild-type Tα1,2 line T2 and Tα1,2mTCF/LEF line JJ were digested with DNase I either as naked DNA in vitro or as chromatin in permeabilized cells. DNA samples (10 μg) were digested with SacI, electrophoresed through a 0.9% agarose gel, and analyzed on a Southern blot probed with a 32P-labeled 1.1-kb Jδ3 genomic fragment (22). A DNase I-hypersensitive region over the enhancer in line T2 is denoted by a bracket. Size makers (in kilobases) are indicated at the left.

We then used LM-PCR to allow fine mapping of the altered chromatin structure detected by DNase I digestion. In vivo DNase I treatment of DNA from wild-type Tα1,2 transgenic line T2 revealed extended regions of hypersensitivity within the enhancer, compared with those in in vitro-treated DNA (Fig. 9A). Of note is a particularly strong hypersensitive nucleotide at the downstream border of the TCF/LEF site. This hypersensitivity is directly attributable to occupancy of the TCF/LEF site, as it was previously detected by in vitro footprinting with purified LEF-1 (6, 59). In addition, a stretch of strongly hypersensitive bases was detected between the TCF/LEF and CRE sites. DNase I hypersensitivity was previously detected in this region by footprinting of in vitro-reconstituted chromatin templates with purified LEF-1 (42). Hence, hypersensitive regions both 5′ and 3′ of the TCF/LEF site seem to be a direct consequence of TCF/LEF binding. Hypersensitive regions were also detected upstream and downstream of the GC-I box and downstream of the Ets site. The extensive DNase I hypersensitivity presumably reflects binding and distortion of the DNA as a consequence of both TCF/LEF binding and interactions among the various DNA-bound factors. Likely due to the extensive DNase I hypersensitivity, clear DNase I footprints, which would be indicative of an occupied wild-type Eα, were not detected. Extended DNase I hypersensitivity between transcription factor binding sites, rather than footprints over the binding sites, were similarly detected in studies of the interleukin-2 enhancer (54).

FIG. 9.

Chromatin structure probed by LM-PCR analysis of DNase I digestion products. (A) Transgenic thymocyte DNA from Tα1,2 line T2 was digested with DNase I as naked (N) DNA in vitro or as chromatin (C) in permeabilized cells and was then subjected to LM-PCR. Lane G displays guanine residues detected by LM-PCR of DMS-treated samples. DNase I-hypersensitive (HS) regions within the wild-type enhancer are indicated by brackets. A prominent hypersensitive base previously shown to be dependent upon LEF-1 binding (6, 59) is also indicated (open arrowhead). Protein binding sites are indicated by brackets. (B) Transgenic thymocyte DNAs from Tα1,2 line T2, Tα1,2mTCF/LEF line JJ, and Tα1,2mEts line JR were digested with DNase I as chromatin (C) in permeabilized cells and were then subjected to LM-PCR. Note that the DNase I digestion patterns upstream of the GC-I box are offset between line T2 and lines JJ and JR due to the use of slightly different cloning strategies for the different constructs (53). These differences lie outside the minimal Eα.

Strikingly, a comparison of in vivo DNase I-treated DNA samples from Tα1,2 line T2, Tα1,2mTCF/LEF line JJ, and Tα1,2mEts line JR revealed no evidence of hypersensitive regions in the mutant enhancers (Fig. 9B), supporting the notion that the mutant enhancers are unoccupied. The result for Tα1,2mEts line JR is particularly important because it argues persuasively that the TCF/LEF binding site remains unoccupied in the absence of Ets binding, as initially suggested by DMS footprinting (Fig. 7A).

DISCUSSION

Coordinate factor binding to the minimal Eα in vivo.

Because of the positions of their binding sites in an accessible location at the edge or on the surface of a nucleosome, some transcription factors can bind to chromatin, initiate the disruption of the nucleosome structure, and in this way facilitate the binding of other factors to adjacent but otherwise inaccessible sites (2, 38). Our data indicate that no single factor can access its binding site to carry out this function for the minimal Eα. As such, it is possible that none of the binding sites within the minimal Eα is positioned appropriately with respect to the nucleosome to allow appropriate access. Simultaneous loading of multiple transcription factors may be essential for stable binding to nucleosomal DNA when no one site is readily accessible.

Our experiments have implications for the mechanism by which TCF/LEF and other HMG proteins regulate gene expression. LEF-1 binds to its specific sequence with only 20- to 40-fold-greater affinity than to random DNA (14), raising the question of how it can display appropriate binding site selectivity when challenged with a complete genome. This problem also applies to other sequence-specific members of the HMG family of proteins (20). Our data clearly indicate that TCF/LEF must bind to the minimal Eα in vivo in conjunction with other sequence-specific proteins. This requirement for cooperative binding is both consistent with and provides a mechanism to overcome the low binding specificity of TCF/LEF factors. Importantly, our data argue against the possibility that these factors play an initiating or nucleating role for the assembly of a multiprotein complex on Eα, as suggested elsewhere (34, 66). We predict that cooperative binding with other factors will be found to be an important general mechanism for increasing the sequence selectivity of members of the HMG family.

We have identified the GC-I box as a novel, functionally important regulatory site within Eα that binds Sp1. The GC-I box was not detected in initial studies of the enhancer by DNase I footprinting in vitro (30). Further, more recent analyses of factor assembly and functioning on the enhancer (17, 42, 59, 64, 65) were performed with 95- and 98-bp enhancer fragments (corresponding to bases 19 to 112 and 12 to 109, respectively, of the 116-bp fragment originally identified by Ho et al. [30]) that lack the GC-I box. Interestingly, although the in vitro transcription experiments of Mayall et al. (42) made use of an enhancer fragment lacking the GC-I box, a similarly situated Sp1 site was contributed by the thymidine kinase promoter in their construct. Purified Sp1 was found to act in synergy with enhancer binding proteins (42), perhaps because the fortuitously positioned promoter site mimicked the natural enhancer site.

The adjacent GC-II box identified in this study was previously found to be occupied by DNase I footprinting experiments performed in vitro with Jurkat cell extracts (30). As it is not protected by HeLa cell nuclear extract or purified CREB protein (17, 42), it may serve as the binding site for an unidentified T-cell-specific nuclear protein. Our transient transfection experiments did not attribute functional activity to the GC-II box, but it should be noted that our experiments did not address the roles of the GC-I and GC-II boxes in a chromosomal context.

In a formal sense, the GC-I and GC-II boxes should not be considered true components of the functionally defined minimal Eα, as transient transfection experiments indicated that substantial enhancer activity remained with both sites deleted. Given this finding our data are consistent with two distinct models for coordinate factor binding to the minimal Eα (defined as extending from the CRE site through the Ets site). The first model proposes fully cooperative occupancy, in which simultaneous availability of all enhancer binding proteins is required to disrupt the nucleosome structure and assemble a stable complex on the enhancer. The second model has aspects of both cooperative occupancy and hierarchical occupancy. It suggests that the combination of TCF/LEF and Ets factors (and presumably also CBF/PEBP2, which binds in a highly cooperative fashion with Ets-1 in vitro [17, 68]) is required to initiate disruption of the nucleosome structure and facilitate the binding of CREB/ATF proteins to the 5′ end of the enhancer. In vivo analysis of a CRE site mutant should distinguish the models; elimination of TCF/LEF, Ets, and CBF/PEBP2 site occupancy by this mutation would argue strongly in favor of simultaneous, single-step occupancy. Because occupancy of the CBF/PEBP2 and Ets binding sites depends on LEF-1-induced bending and helical phasing with the CRE site even on naked DNA templates (17), we favor the notion that CRE site occupancy is critical for the occupancy of other minimal Eα binding sites in vivo. Whether GC-I and GC-II site occupancy is required for the occupancy of minimal Eα binding sites is an open question. Since transient transfection experiments revealed substantial enhancer activity to be retained without the GC-I and GC-II sites, their occupancy might not be critical for occupancy elsewhere. This idea leads to speculation that the assembly of CREB/ATF, TCF/LEF, CBF/PEBP2, and Ets factors occurs in an all-or-none fashion and that the assembly of this complex may be required for the occupancy of GC-I, GC-II, and other sites within Eα. Additional work is required to test the details of this model.

Factor binding and functional studies performed in vivo versus in vitro.

Both of the models outlined above differ from those suggested by studies of factor binding in vitro to naked and chromatin-reconstituted minimal Eα DNA (17, 42). Compared to the analysis of naked DNA templates (17), the more stringent cooperativity detected in our study probably reflects the fact that in vivo occupancy depends on both the specific protein-protein contacts that lead to the cooperative assembly steps previously identified with naked DNA in vitro and an additional level of cooperativity imposed by the need to effectively compete with core histones.

Differences between our results and those obtained with in vitro-reconstituted nucleosomal templates (42) are more surprising. The diminished cooperativity with respect to enhancer occupancy observed in that study was paralleled by diminished functional synergy among enhancer binding proteins. Although transcriptional synergy could be reproduced with limiting concentrations of transcription factors, the enhancer typically retained significant activity in the absence of one or more enhancer binding proteins. One explanation for this difference may be that in vitro-reconstituted nucleosomal templates are in a derepressed or weakly repressed state compared to native chromatin, such that the DNA is relatively more accessible to transcription factors (48). A second explanation may be that the translational positioning of nucleosomes assembled in vitro is distinct from that found in vivo (2). A third possibility is that the heightened cooperativity observed in vivo depends on the coassembly of enhancer binding proteins with coactivators, such as CBP (36) and ALY (6), that were not included in the in vitro experiments. Finally, it is possible that superphysiological levels of the various transcription factors tested in vitro compete for binding sites in nucleosomal DNA in a fashion that is much more efficient than would normally be expected to occur in vivo. Regardless, our work suggests that studies of transcription factor access to chromatin that rely solely on in vitro-reconstituted nucleosomal DNA should be interpreted cautiously.

Comparison with in vivo occupancy of other regulatory elements.

It is interesting to compare our data with in vivo occupancy data obtained for other regulatory elements. Our results suggest a model that is different from that proposed for the βA/ɛ globin gene enhancer (4). Analysis of wild-type and mutant enhancer constructs in transfected cells indicated that the binding of erythroid cell-specific factors additively, rather than cooperatively, increased the probability of the formation of DNase I-hypersensitive sites. Thus, accessible regions were generated even in the absence of one or more tissue-specific factors, although the fraction of cells in which such regions were generated was reduced. Occupancy of the minimal Eα is also different from other instances in which occupancy clearly occurred in a stepwise or hierarchical fashion dependent on the initial binding of a single factor (2, 38). Our data suggest a situation that is similar to one proposed to explain in vivo factor occupancy of the interleukin-2 promoter, as the inhibition of any of several combinations of factors eliminated the occupancy of almost all binding sites (9, 13, 54). In other instances in which regulatory regions are completely unoccupied when a single factor has been inactivated by mutation (33, 40) or when a single binding site has been inactivated by mutation (18), it is unclear whether the missing factor per se disrupts chromatin structure, or rather, provides one of several components required for highly cooperative, all-or-none occupancy.

Long-distance regulation of accessibility by Eα.

Occupancy of the minimal Eα induces only a local change in the organization of the nucleosomal array, as assessed by either micrococcal nuclease digestion or hypersensitivity to DNase I digestion (this study; 42). However, our analysis of the regulation of V(D)J recombination indicates that an occupied minimal Eα can stimulate the accessibility of recombination signal sequences to the V(D)J recombinase at distances of at least 2 kb in transgenic mice (53). Furthermore, the endogenous Eα regulates the accessibility of Jα recombination signal sequences over 70 kb within the endogenous TCR α/δ locus (56). The mechanism by which accessibility may be modulated over such distances has not been established. As the hyperacetylation of histones has been associated with active chromatin domains in vivo (24, 25, 32) and as CREB interacts with CBP and p300 (36), which are themselves histone acetyltransferases (1, 47), regional control of histone acetylation by the enhancer is an appealing possibility. Further investigation is required to evaluate the role of this and other chromatin modifications in long-distance regulation by enhancers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. Suñé for help during the course of this study.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM41052. M.S.K. was the recipient of American Cancer Society Faculty Research award FRA-414. C.H.-M. was supported in part by a fellowship from the Leukemia Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bannister A J, Kouzarides T. The CBP co-activator is a histone acetyltransferase. Nature (London) 1996;384:641–643. doi: 10.1038/384641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beato M, Eisfeld K. Transcription factor access to chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3559–3563. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.18.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behrens J, von Kries J P, Kuhl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature (London) 1996;382:638–642. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyes J, Felsenfeld G. Tissue-specific factors additively increase the probability of the all-or-none formation of a hypersensitive site. EMBO J. 1996;15:2496–2507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brannon M, Gomperts M, Sumoy L, Moon R T, Kimelman D. A β-catenin/XTcf-3 complex binds to the siamois promoter to regulate dorsal axis specification in Xenopus. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2359–2370. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruhn L, Munnerlyn A, Grosschedl R. ALY, a context-dependent coactivator of LEF-1 and AML-1, is required for TCRα enhancer function. Genes Dev. 1997;11:640–653. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bustin M, Reeves R. High-mobility-group chromosomal proteins: architectural components that facilitate chromatin function. Prog Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol. 1996;54:35–100. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlsson P, Waterman M L, Jones K A. The hLEF/TCF-1α HMG protein contains a context-dependent transcriptional activation domain that induces the TCRα enhancer in T cells. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2418–2430. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen D, Rothenberg E V. Interleukin 2 transcription factors as molecular targets of cAMP inhibition: delayed inhibition kinetics and combinatorial transcription roles. J Exp Med. 1994;179:931–942. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Wright K L, Berkowitz E A, Azizkham J C, Ting J P-Y, Lee D C. Protein interactions at Sp1-like sites in the TGFα promoter as visualized by in vivo genomic footprinting. Oncogene. 1994;9:3179–3187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chomezynski P, Saachi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felsenfeld G. Chromatin unfolds. Cell. 1996;86:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrity P A, Chen D, Rothenberg E V, Wold B. Interleukin-2 transcription is regulated in vivo at the level of coordinated binding of both constitutive and regulated factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2159–2169. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giese K, Amsterdam A, Grosschedl R. DNA-binding properties of the HMG domain of the lymphoid-specific transcriptional regulator LEF-1. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2567–2578. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12b.2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giese K, Cox J, Grosschedl R. The HMG domain of lymphoid enhancer factor 1 bends DNA and facilitates assembly of functional nucleoprotein structures. Cell. 1992;69:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90129-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giese K, Grosschedl R. LEF-1 contains an activation domain that stimulates transcription only in a specific context of factor-binding sites. EMBO J. 1993;12:4667–4676. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giese K, Kingsley C, Kirshner J R, Grosschedl R. Assembly and function of a TCRα enhancer complex is dependent on LEF-1-induced DNA bending and multiple protein-protein interactions. Genes Dev. 1995;9:995–1008. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong Q, McDowell J, Dean A. Essential role of NF-E2 in remodelling a chromatin structure and transcriptional activation of the ɛ-globin gene in vivo by 5′ hypersensitive site 2 of the β-globin locus control region. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6055–6064. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross D S, Garrard W T. Nuclease hypersensitive sites in chromatin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:159–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grosschedl R, Giese K, Pagel J. HMG domain proteins: architectural elements in the assembly of nucleoprotein structures. Trends Genet. 1994;10:94–100. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hata S, Brenner M B, Krangel M S. Identification of putative human T-cell receptor δ complementary DNA clones. Science (Washington, DC) 1987;238:678–682. doi: 10.1126/science.3499667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hata S, Clabby M, Devlin P, Spits H, de Vries J E, Krangel M S. Diversity and organization of human T cell receptor δ variable gene segments. J Exp Med. 1989;169:41–57. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haynes T L, Thomas M B, Dusing M R, Valerius M T, Potter S S, Wiginton D A. An enhancer LEF-1/TCF-1 site is essential for insertion site-independent transgene expression in thymus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:5034–5044. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.24.5034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hebbes T R, Clayton A L, Thorne A W, Crane-Robinson C. Core histone hyperacetylation co-maps with generalized DNase I sensitivity in the chicken β-globin chromosomal domain. EMBO J. 1994;13:1823–1830. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hebbes T R, Thorne A W, Crane-Robinson C. A direct link between core histone acetylation and transcriptionally active chromatin. EMBO J. 1988;7:1395–1402. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernandez-Munain C, Krangel M S. Regulation of the T-cell receptor δ enhancer by functional cooperation between c-Myb and core-binding factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:473–483. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez-Munain C, Krangel M S. c-Myb and core-binding factor (CBF/PEBP2) display functional synergy but bind independently to adjacent sites in the T-cell receptor δ enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3090–3099. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernandez-Munain C, Lauzurica P, Krangel M S. Regulation of T cell receptor δ gene rearrangement by c-Myb. J Exp Med. 1996;183:289–293. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho I-C, Bhat N K, Gottschalk L R, Lindsten T, Thompson C B, Papas T S, Leiden J M. Sequence-specific binding of human Ets-1 to the T cell receptor α gene enhancer. Science (Washington, DC) 1990;250:814–818. doi: 10.1126/science.2237431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho I-C, Yang L-H, Morle G, Leiden J M. A T-cell-specific transcriptional enhancer element 3′ of Cα in the human T-cell receptor α locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6714–6718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huber O, Korn R, McLaughlin J, Ohsugi M, Hermann B G, Kemler R. Nuclear localization of β-catenin by interaction with transcription factor LEF-1. Mech Dev. 1996;59:3–10. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00597-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeppesen P, Turner B M. The inactive X chromosome in female mammals is distinguished by a lack of histone H4 acetylation, a cytogenetic marker for gene expression. Cell. 1993;74:281–289. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90419-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kara C J, Glimcher L H. In vivo footprinting of MHC class II genes: bare promoters in the bare lymphocyte syndrome. Science (Washington, DC) 1991;252:709–711. doi: 10.1126/science.1902592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kingston R E, Bunker C A, Imbalzano A N. Repression and activation by multiprotein complexes that alter chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 1996;10:905–920. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kornberg R D, Lorch Y. Chromatin structure and transcription. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:563–587. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwok R P S, Lundblad J R, Chrivia J C, Richards J P, Bachinger H P, Brennan R D, Roberts S G E, Green M R, Goodman R H. Nuclear protein CBP is a coactivator for the transcription factor CREB. Nature (London) 1994;370:223–226. doi: 10.1038/370223a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lauzurica P, Krangel M S. Enhancer-dependent and -independent steps in the rearrangement of a human T cell receptor δ transgene. J Exp Med. 1994;179:43–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Q, Wrange O, Eriksson P. The role of chromatin in transcriptional regulation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:731–742. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Love J J, Li X, Case D A, Giese K, Grosschedl R, Wright P E. Structural basis for DNA bending by the architectural transcription factor LEF-1. Nature (London) 1995;376:791–795. doi: 10.1038/376791a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mach B, Steimle V, Martinez-Soria E, Reith W. Regulation of MHC class II genes: lessons from a disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:301–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez-Balbas M A, Dey A, Rabindran S K, Ozato K, Wu C. Displacement of sequence-specific transcription factors from mitotic chromatin. Cell. 1995;83:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayall T P, Sheridan P L, Montminy M R, Jones K A. Distinct roles for P-CREB and LEF-1 in TCRα enhancer assembly and activation on chromatin templates in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:887–899. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McMurry M T, Hernandez-Munain C, Lauzurica P, Krangel M S. Enhancer control of local accessibility to V(D)J recombinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4553–4561. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moolenar M, Van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Peterson-Maduro J, Godsave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destree O, Clevers H. Xtcf-3 transcription factor mediates β-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell. 1996;86:391–399. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mueller P R, Garrity P A, Wold B. Ligation-mediated PCR for genomic sequencing and footprinting. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1992. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mueller P R, Wold B. In vivo footprinting of a muscle specific enhancer by ligation mediated PCR. Science (Washington, DC) 1989;246:780–786. doi: 10.1126/science.2814500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogryzko V V, Schiltz R L, Russanova V, Howard B H, Nakatani Y. The transcriptional coactivators p300 and CBP are histone acetyltransferases. Cell. 1996;87:953–959. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)82001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paranjape S M, Kamakaka R T, Kadonaga J T. Role of chromatin structure in the regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:265–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfeifer G P, Riggs A D. Chromatin differences between active and inactive X chromosomes revealed by genomic footprinting of permeabilized cells using DNase I and ligation-mediated PCR. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1102–1113. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Redondo J M, Pfohl J L, Krangel M S. Identification of an essential site for transcriptional activation within the human T-cell receptor δ enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5671–5680. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riese J, Yu X, Munnerlyn A, Eresh S, Hsu S-C, Grosschedl R, Bienz M. LEF-1, a nuclear factor coordinating signaling imputs from wingless and decapentaplegic. Cell. 1997;88:777–787. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81924-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rigaud G, Roux J, Pictet R, Grange T. In vivo footprinting of rat TAT gene: dynamic interplay between the glucocorticoid receptor and a liver-specific factor. Cell. 1991;67:977–986. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90370-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roberts J L, Lauzurica P, Krangel M S. Developmental regulation of VDJ recombination by the core fragment of the T cell receptor α enhancer. J Exp Med. 1997;185:131–140. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rothenberg E V, Ward S B. A dynamic assembly of diverse transcription factors integrates activation and cell-type information for the interleukin 2 gene regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9358–9365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheridan P L, Sheline C T, Cannon K, Voz M L, Pazin M J, Kadonaga J T, Jones K A. Activation of the HIV-1 enhancer by the LEF-1 HMG protein on nucleosome-assembled DNA in vitro. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2090–2104. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sleckman B P, Bardon C G, Ferrini R, Davidson L, Alt F W. Function of the TCRα enhancer in αβ and γδ T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:505–515. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sleckman B P, Gorman J R, Alt F W. Accessibility control of antigen receptor variable region gene assembly: role of cis-acting elements. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:459–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stanhope-Baker P, Hudson K M, Shaffer A L, Constantinescu A, Schlissel M S. Cell type-specific chromatin structure determines the targeting of V(D)J recombinase activity in vitro. Cell. 1996;85:887–897. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Travis A, Amsterdam A, Belanger C, Grosschedl R. LEF-1, a gene encoding a lymphoid-specific protein with an HMG domain, regulates T-cell receptor α enhancer function. Genes Dev. 1991;5:880–894. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van de Wetering M, Cavallo R, Dooijes D, Van Beest M, Van Es J, Loureiro J, Ypma A, Hursh D, Jones T, Bejsovec A, Peifer M, Mortin M, Clevers H. Armadillo coactivates transcription driven by the product of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dTCF. Cell. 1997;88:789–799. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van de Wetering M, Clevers H. Sequence-specific interaction of the HMG box proteins TCF-1 and SRY occurs within the minor groove of a Watson-Crick double helix. EMBO J. 1992;11:3039–3044. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Van Norren K, Clevers H. Sox-4, an Sry-like HMG box protein, is a transcriptional activator in lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1993;12:3847–3854. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wade P A, Pruss D, Wolffe A P. Histone acetylation: chromatin in action. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:128–132. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Waterman M L, Fischer W H, Jones K A. A thymus-specific member of the HMG protein family regulates the T cell receptor Cα enhancer. Genes Dev. 1991;5:656–669. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.4.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Waterman M L, Jones K A. Purification of TCF-1α, a T-cell-specific transcription factor that activates the T-cell receptor Cα gene enhancer in a context-dependent manner. New Biol. 1990;2:621–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Werner M H, Burley S K. Architectural transcription factors: proteins that remodel DNA. Cell. 1997;88:733–736. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81917-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wolffe A P, Pruss D. Targeting chromatin disruption: transcription regulators that acetylate histones. Cell. 1996;84:817–819. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wotton D, Ghysdael J, Wang S, Speck N A, Owen M J. Cooperative binding of Ets-1 and core binding factor to DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:840–850. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wright K L, White L C, Kelly A, Beck S, Trowsdale J, Ting J P-Y. Coordinate regulation of the human TAP1 and LMP2 genes from a shared bidirectional promoter. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1459–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]