Abstract

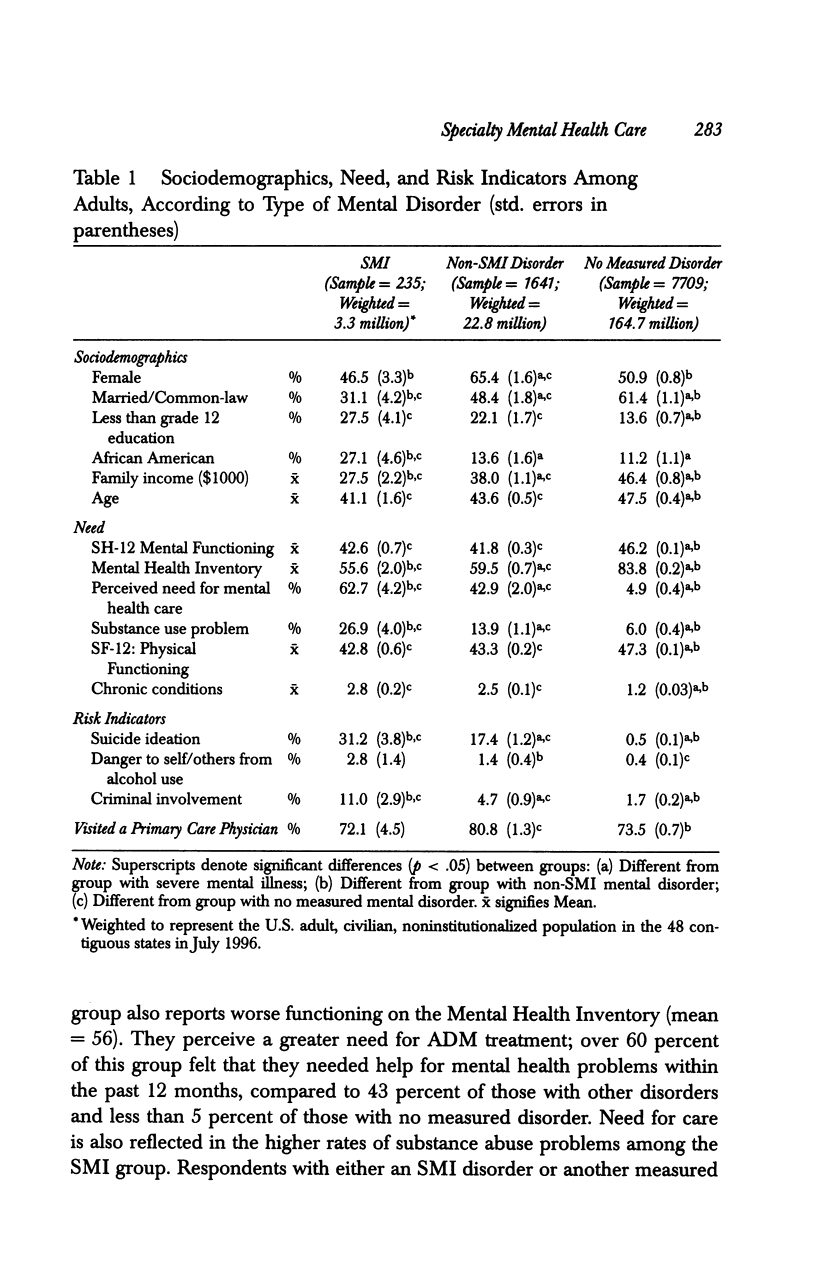

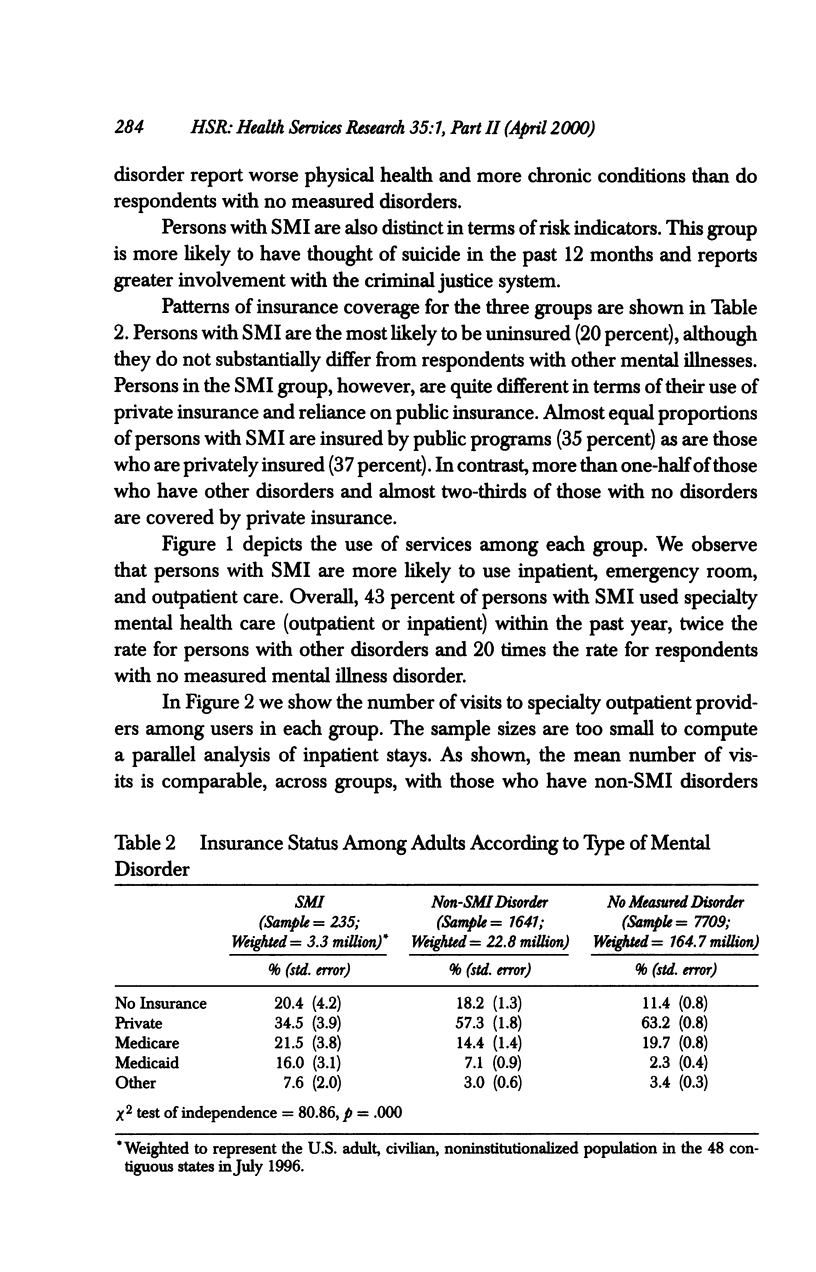

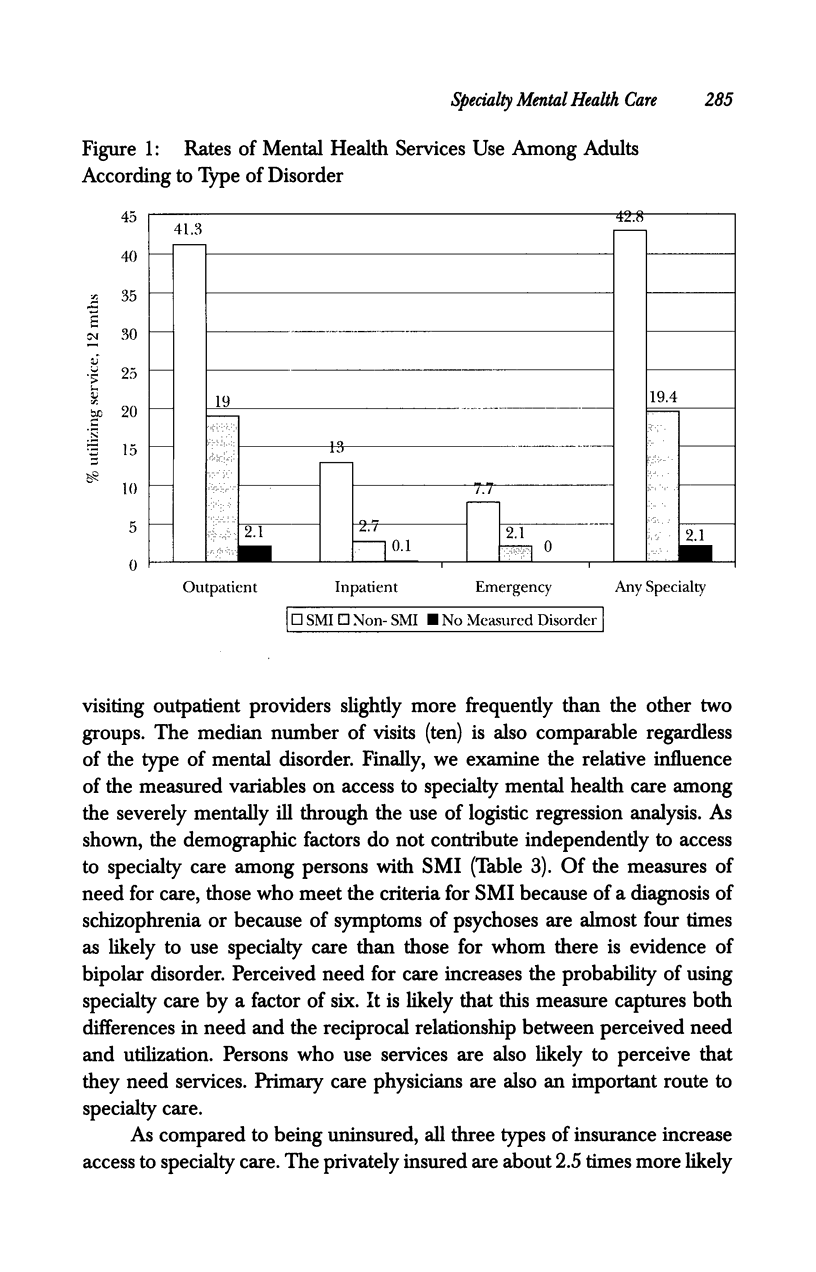

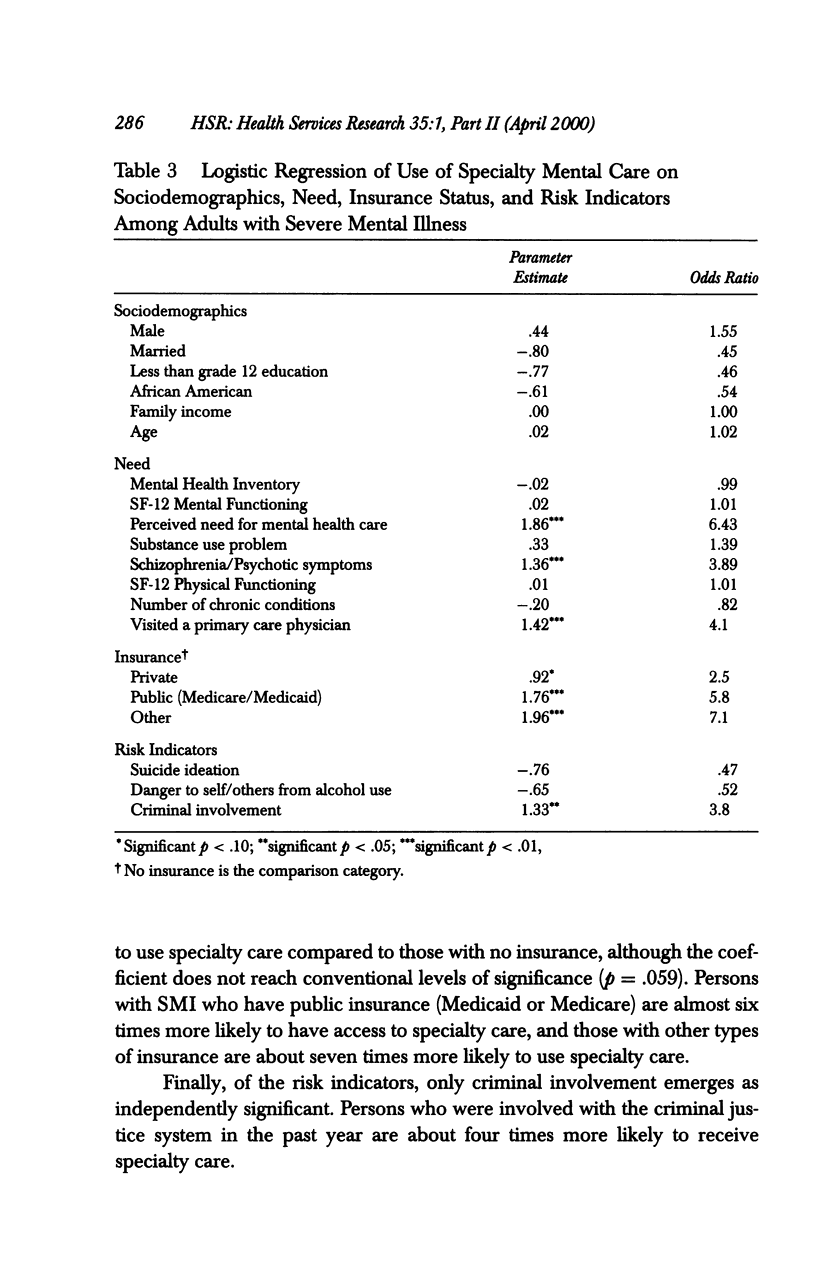

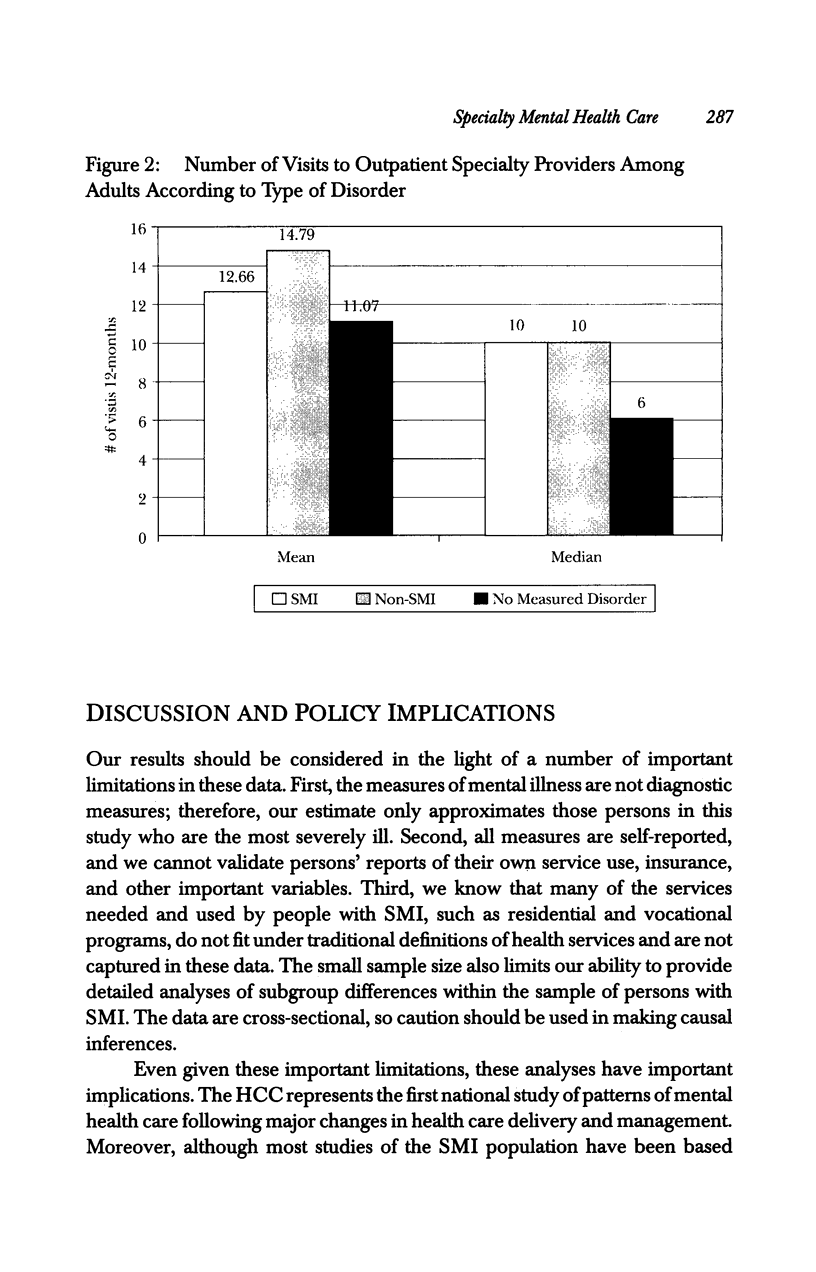

OBJECTIVE: To examine the sociodemographic, need, risk, and insurance characteristics of persons with severe mental illness and the importance of these characteristics for predicting specialty mental health utilization among this group. DATA SOURCE: The Healthcare for Communities survey, a national study that tracks alcohol, drug, and mental health services utilization. Data come from a telephone survey of adults from 60 communities across the United States, and from a supplemental geographically dispersed sample. STUDY DESIGN: Respondents were categorized as having a severe mental disorder, other mental disorder, or no measured mental disorder. Differences among groups in sociodemographics (gender, marital status, race, education, and income), insurance coverage, need for mental health care (symptoms and perceived need), and risk indicators (suicide ideation, criminal involvement, and aggressive behavior) are examined. Measures of service use for mental health care include emergency room, inpatient, and specialty outpatient care. The importance of sociodemographics, need, insurance status, and risk indicators for specialty mental health care utilization are examined through logistic regression. PRINCIPAL FINDINGS: The severely mentally ill in this study are disproportionately African American, unmarried, male, less educated, and have lower family incomes than those with other disorders and those with no measured mental disorders. In a 12-month period almost three-fifths of persons with severe mental illness did not receive specialty mental health care. One in five persons with severe mental illness are uninsured, and Medicare or Medicaid insures 37 percent. Persons covered by these public programs are over six times more likely to have access to specialty care than the uninsured are. Involvement in the criminal justice system also increases the probability that a person will receive care by a factor of about four, independent of level of need. The average number of outpatient visits for specialty care varies little across type of disorder, and the median number of visits (ten) is equivalent for those with a severe mental illness and those with other disorders. CONCLUSIONS: Persons with severe mental illness have a high level of economic and social disadvantage. Barriers to care, including lack of insurance, are substantial and many do not receive specialty care. Public insurance programs are the major points of leverage for improving access, and policy interventions should be targeted to these programs. Problems of adequate care for the severely mentally ill may be exacerbated by the managed care trend to reductions in intensity of treatment.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Goldberg J. F., Harrow M., Grossman L. S. Recurrent affective syndromes in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders at follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 1995 Mar;166(3):382–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M., Sands J. R., Silverstein M. L., Goldberg J. F. Course and outcome for schizophrenia versus other psychotic patients: a longitudinal study. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(2):287–303. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard K. I., Cornille T. A., Lyons J. S., Vessey J. T., Lueger R. J., Saunders S. M. Patterns of mental health service utilization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996 Aug;53(8):696–703. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830080048009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Zhao S., Katz S. J., Kouzis A. C., Frank R. G., Edlund M., Leaf P. Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 Jan;156(1):115–123. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landerman L. R., Burns B. J., Swartz M. S., Wagner H. R., George L. K. The relationship between insurance coverage and psychiatric disorder in predicting use of mental health services. Am J Psychiatry. 1994 Dec;151(12):1785–1790. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf P. J., Livingston M. M., Tischler G. L., Weissman M. M., Holzer C. E., 3rd, Myers J. K. Contact with health professionals for the treatment of psychiatric and emotional problems. Med Care. 1985 Dec;23(12):1322–1337. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198512000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie D. L., Rosenheck R. Shifting to outpatient care? Mental health care use and cost under private insurance. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 Aug;156(8):1250–1257. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay A. P., Tarbuck A. F., Shapleske J., McKenna P. J. Neuropsychological function in manic-depressive psychosis. Evidence for persistent deficits in patients with chronic, severe illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1995 Jul;167(1):51–57. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D., Angel R., Davies L. Risk and selection processes between the general and the specialty mental health sectors. J Health Soc Behav. 1991 Mar;32(1):49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D., McAlpine D. D. Mission unfulfilled: potholes on the road to mental health parity. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999 Sep-Oct;18(5):7–21. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz J., Bromet E. J., Lavelle J., Severance K. J., Zariello S. L., Rosen B. Relationship between type of insurance and care during the early course of psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1998 Oct;155(10):1392–1397. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier D. A., Narrow W. E., Rae D. S., Manderscheid R. W., Locke B. Z., Goodwin F. K. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993 Feb;50(2):85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J. B., Aasland O. G., Babor T. F., de la Fuente J. R., Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993 Jun;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski S. M., Shelton R. C., Kolbrener M. L. The effects of race and comorbidity on clinical diagnosis in patients with psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993 Mar;54(3):96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R., Gresenz C., Sherbourne C., Minnium K., Klap R., Bhattacharya J., Farley D., Young A. S., Burnam M. A., Wells K. B. The design of Healthcare for Communities: a study of health care delivery for alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health conditions. Inquiry. 1999 Summer;36(2):221–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan G., Young A. S., Morgenstern H. Behaviors as risk factors for rehospitalization: implications for predicting and preventing admissions among the seriously mentally ill. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997 May;32(4):185–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00788237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J., Jr, Kosinski M., Keller S. D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996 Mar;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickizer T. M., Lessler D. Effects of utilization management on patterns of hospital care among privately insured adult patients. Med Care. 1998 Nov;36(11):1545–1554. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199811000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]