Abstract

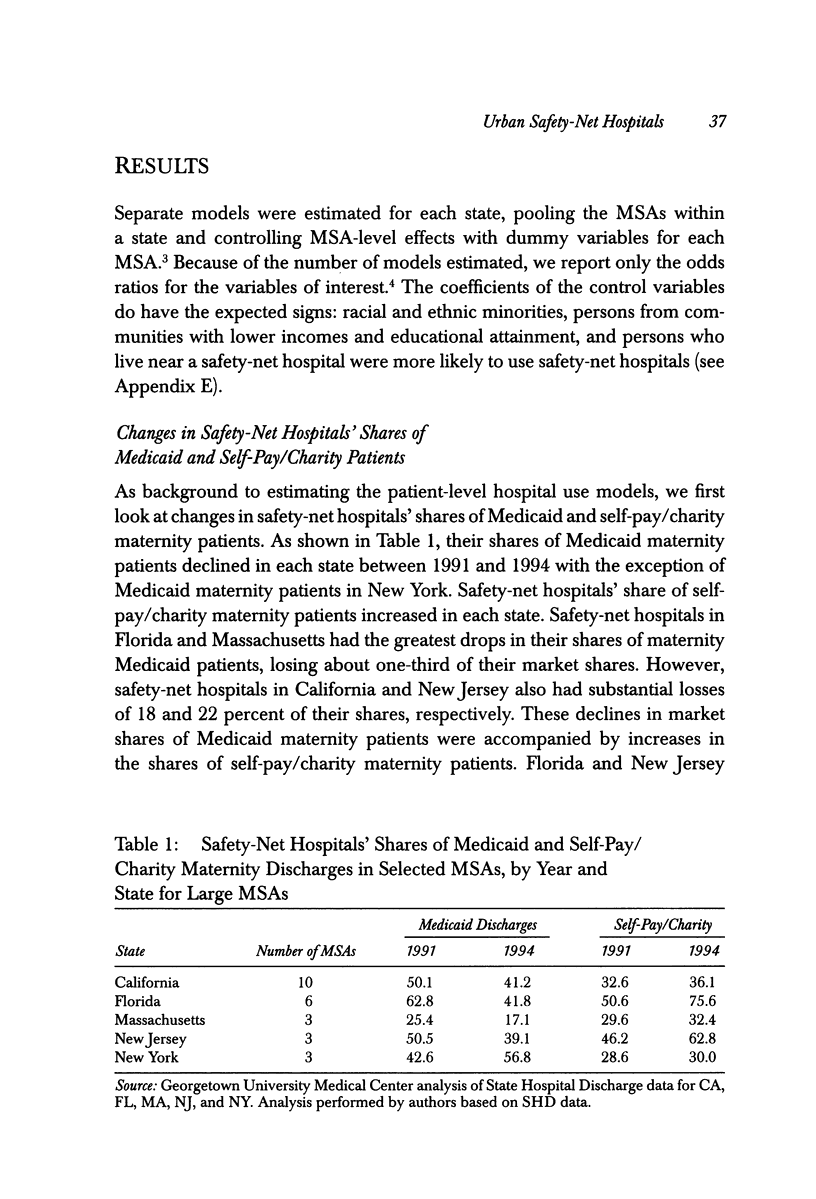

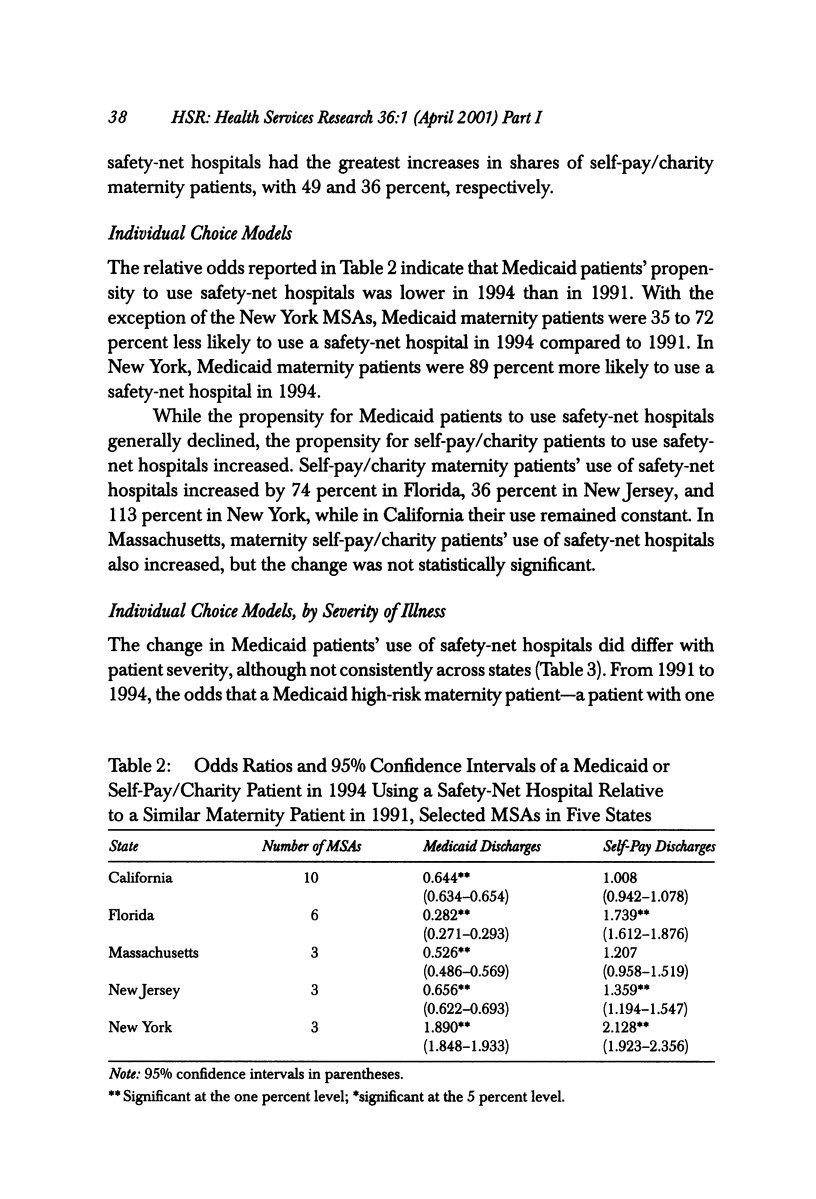

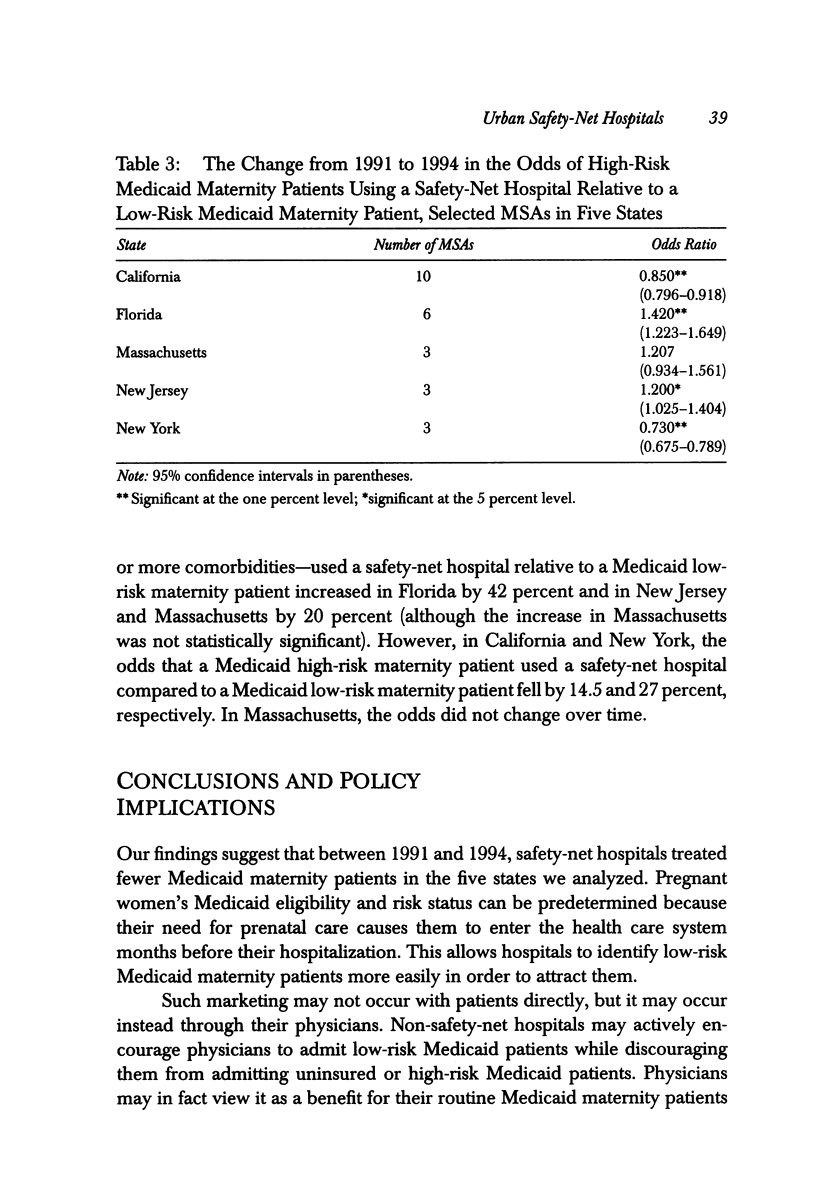

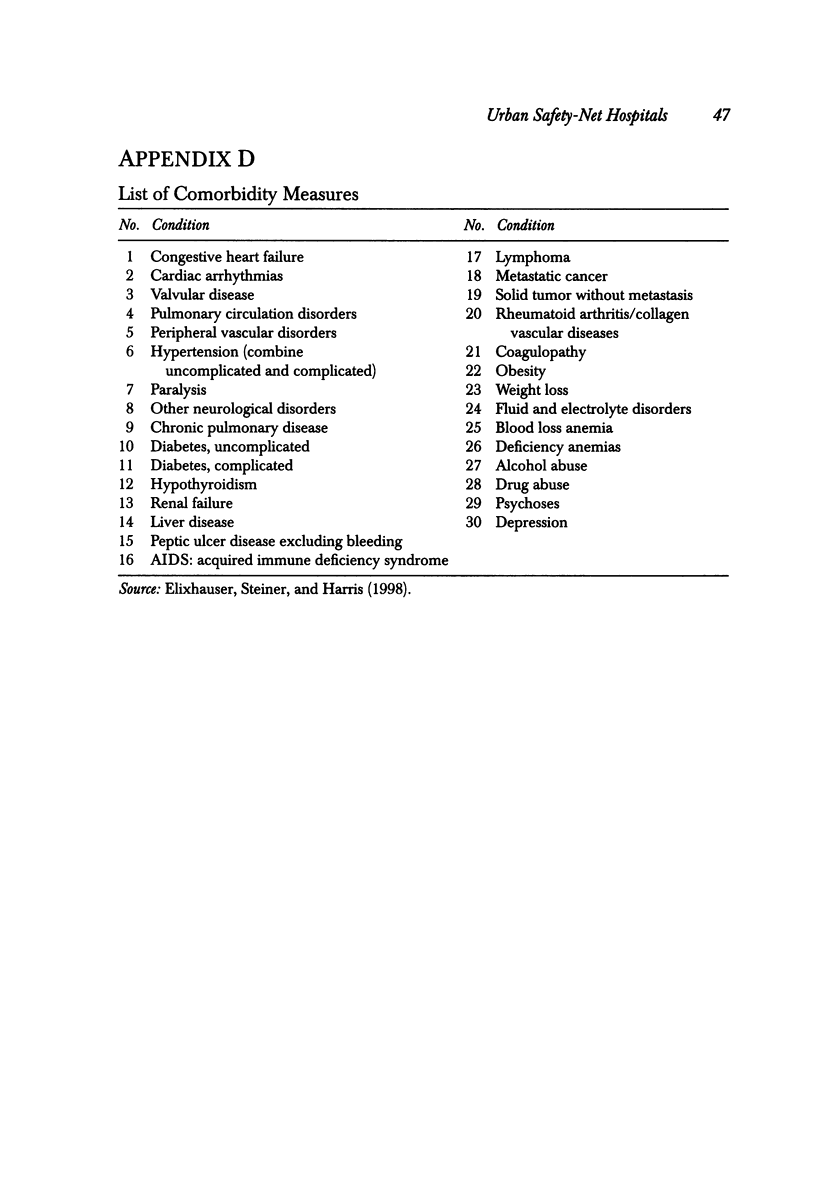

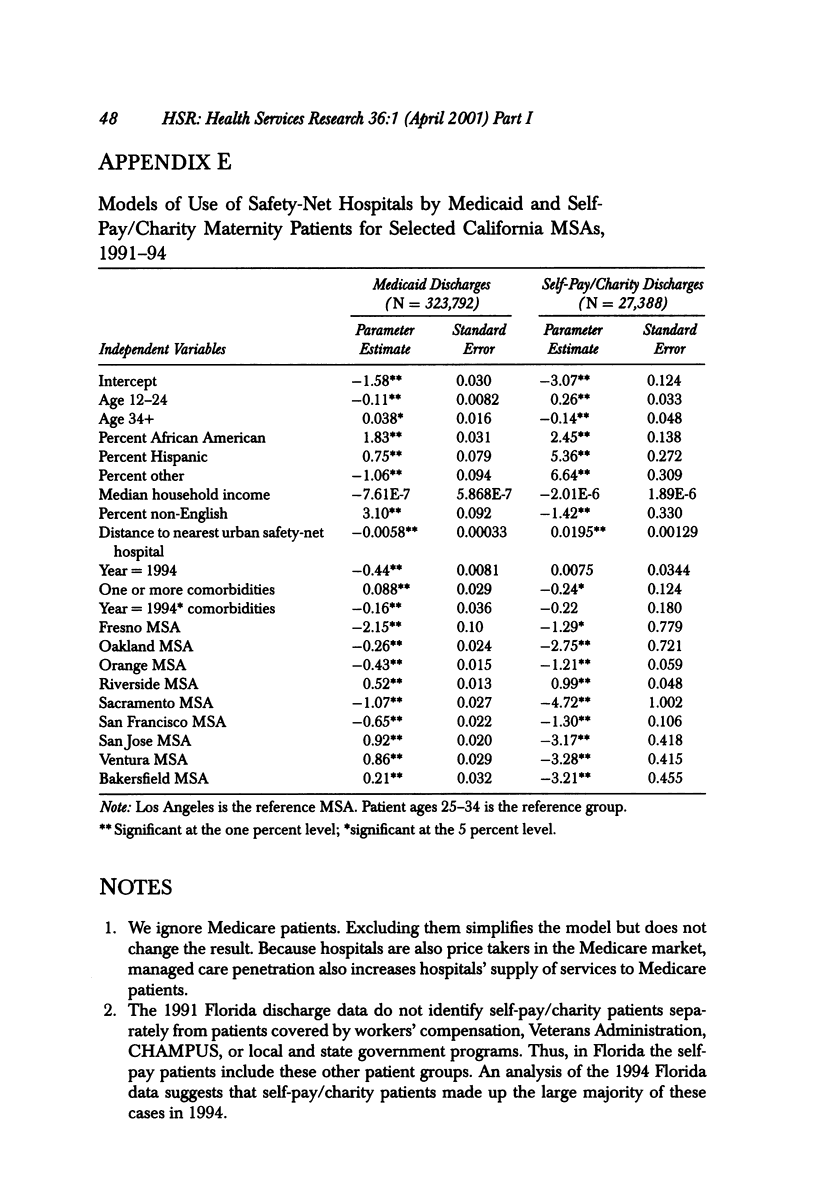

OBJECTIVE: To examine data on Medicaid and self-pay/charity maternity cases to address four questions: (1) Did safety-net hospitals' share of Medicaid patients decline while their shares of self-pay/charity-care patients increased from 1991 to 1994? (2) Did Medicaid patients' propensity to use safety-net hospitals decline during 1991-94? (3) Did self-pay/charity patients' propensity to use safety-net hospitals increase during 1991-94? (4) Did the change in Medicaid patients' use of safety-net hospitals differ for low- and high-risk patients? STUDY DESIGN: We use hospital discharge data to estimate logistic regression models of hospital choice for low-risk and high-risk Medicaid and self-pay/charity maternity patients for 25 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in five states for the years 1991 and 1994. We define low-risk patients as discharges without comorbidities and high-risk patients as discharges with comorbidities that may substantially increase hospital costs, length of stay, or morbidity. The five states are California, Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York. The MSAs in the analysis are those with at least one safety-net hospital and a population of 500,000 or more. This study also uses data from the 1990 Census and AHA Annual Survey of Hospitals. The regression analysis estimates the change between 1991 and 1994 in the relative odds of a Medicaid or self-pay/charity patient using a safety-net hospital. We explore whether this change in the relative odds is related to the risk status of the patient. PRINCIPAL FINDINGS: The findings suggest that competition for Medicaid patients increased from 1991 to 1994. Over time, safety-net hospitals lost low-risk maternity Medicaid patients while services to high-risk maternity Medicaid patients and self-pay/charity maternity patients remained concentrated in safety-net hospitals. IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY: Safety-net hospitals use Medicaid patient revenues and public subsidies that are based on Medicaid patient volumes to subsidize care for uninsured and underinsured patients. If safety-net hospitals continue to lose their low-risk Medicaid patients, their ability to finance care for the medically indigent will be impaired. Increased hospital competition may improve access to hospital care for low-risk Medicaid patients, but policymakers should be cognizant of the potential reduction in access to hospital care for uninsured and underinsured patients. Public policymakers should ensure that safety-net hospitals have sufficient financial resources to care for these patients by subsidizing their care directly.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Burns L. R., Wholey D. R. The impact of physician characteristics in conditional choice models for hospital care. J Health Econ. 1992 May;11(1):43–62. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(92)90024-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson M. E., Pompei P., Ales K. L., MacKenzie C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. A., Lee H. L. The determinants of spatial distribution of hospital utilization in a region. Med Care. 1985 Jan;23(1):27–38. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elixhauser A., Steiner C., Harris D. R., Coffey R. M. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998 Jan;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R. P., McGuire T. G. Insurance principles and the design of prospective payment systems. J Health Econ. 1988 Sep;7(3):215–237. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(88)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R., Chan H. C., Kralewski J., Dowd B., Shapiro J. Effects of HMOs on the creation of competitive markets for hospital services. J Health Econ. 1990 Sep;9(2):207–222. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(90)90018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman L. E. What types of hospitals form the safety net? Health Aff (Millwood) 1997 Jul-Aug;16(4):215–222. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman E. California public hospitals. The buck has stopped. JAMA. 1997 Feb 19;277(7):577–581. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnick D. W., Lichtenberg E., Phibbs C. S., Luft H. S., Peltzman D. J., McPhee S. J. The sensitivity of conditional choice models for hospital care to estimation technique. J Health Econ. 1989;8(4):377–397. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(90)90022-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin D. J., Hadley J. Population characteristics of markets of safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals. J Urban Health. 1999 Sep;76(3):351–370. doi: 10.1007/BF02345673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner P. F., Blumenthal D. Reforming the structure and management of academic medical centers: case studies of ten institutions. Acad Med. 1998 Jul;73(7):818–825. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199807000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick G. A., Zwanziger J., Bamezai A., Pattison R. The effects of market structure and bargaining position on hospital prices. J Health Econ. 1992 Oct;11(3):217–233. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(92)90001-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. H., Luft H. S. Managed care plan performance since 1980. A literature analysis. JAMA. 1994 May 18;271(19):1512–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. B. Physician participation in Medicaid revisited. Med Care. 1991 Jul;29(7):645–653. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phibbs C. S., Mark D. H., Luft H. S., Peltzman-Rennie D. J., Garnick D. W., Lichtenberg E., McPhee S. J. Choice of hospital for delivery: a comparison of high-risk and low-risk women. Health Serv Res. 1993 Jun;28(2):201–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porell F. W., Adams E. K. Hospital choice models: a review and assessment of their utility for policy impact analysis. Med Care Res Rev. 1995 Jun;52(2):158–195. doi: 10.1177/107755879505200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon G. W., Skinner J. L., Bashshur R. L. Time and distance: the journey for medical care. Int J Health Serv. 1973 Spring;3(2):237–244. doi: 10.2190/FK1K-H8L9-J008-GW65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studnicki J. The geographic fallacy: hospital planning and spatial behavior. Hosp Adm (Chic) 1975 Summer;20(3):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]