Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Urgent care (UC; a convenient site to receive care for ambulatory-sensitive) centers conditions; however, UC clinicians showed the highest rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among outpatient settings according to national billing data. Antibiotic prescribing practices in pediatric-specific UC centers were not known but assumed to require improvement. The aim of this multisite quality improvement project was to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing practices for 3 target diagnoses in pediatric UC centers by a relative 20% by December 1, 2019.

METHODS:

The Society of Pediatric Urgent Care invited pediatric UC clinicians to participate in a multisite quality improvement study from June 2019 to December 2019. The diagnoses included acute otitis media (AOM), otitis media with effusion, and pharyngitis. Algorithms based on published guidelines were used to identify inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions according to indication, agent, and duration. Sites completed multiple intervention cycles from a menu of publicly available antibiotic stewardship materials. Participants submitted data electronically. The outcome measure was the percentage of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions for the target diagnoses. Process measures were use of delayed antibiotics for AOM and inappropriate testing in pharyngitis.

RESULTS:

From 20 UC centers, 157 providers submitted data from 3833 encounters during the intervention cycles. Overall inappropriate antibiotic prescription rates decreased by a relative 53.9%. Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing decreased from 57.0% to 36.6% for AOM, 54.6% to 48.4% for otitis media with effusion, and 66.9% to 11.7% for pharyngitis.

CONCLUSIONS:

Participating pediatric UC providers decreased inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions from 60.3% to 27.8% using publicly available interventions.

Urgent care (UC) centers are becoming an increasingly popular setting for ambulatory-sensitive conditions.1 In 2014, a group of pediatric UC clinicians founded the Society of Pediatric Urgent Care (SPUC) with the goal of developing clinical standards for pediatric UC clinicians who provide unscheduled nonemergent care to children when the medical home is not an option.2 More than one-third of pediatric patients who present to UC centers report upper respiratory symptoms, including otalgia and pharyngitis, as their chief complaint.3

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing contributes to increased rates of antibiotic-resistant infections, leading to increased health care costs.4 This prescribing practice also puts patients at risk for adverse reactions and drug adverse effects.5 In a study of claims data, Palms et al6 reported that the highest incidence (45.7%) of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing occurs in UC centers. However, these researchers did not differentiate between general UC and specialized pediatric UC centers. In a separate study, Frost et al7 reported that pediatricians are more likely to follow guideline-concordant prescribing practices for pharyngitis and sinusitis and withhold antibiotics for viral respiratory infections compared with nonpediatricians.

Previous antibiotic stewardship quality improvement (QI) studies have encouraged the use of delayed prescriptions in acute otitis media (AOM) to decrease overall antibiotic use in eligible patients in the primary pediatric setting8 and emergency department.9 Other outpatient studies have coached providers on effectively communicating a treatment plan with families to decrease unnecessary antibiotic prescribing while maintaining positive patient experiences.10 In their joint statement released in 2020, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society identified UC centers as an important target for antibiotic stewardship initiatives.11 A leadership team comprising subject matter experts from the SPUC, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Children’s National Hospital, and the Antibiotic Resistance Action Center designed and led a multisite QI collaborative to achieve a reasonable goal: Decrease the use of inappropriate antibiotics in freestanding pediatric UC centers by a relative 20% from the beginning of the project period to the end.

METHODS

Project Design

In January 2019, the leadership team recruited participants through SPUC e-mails, newsletters, and webinars. The SPUC had a membership of ~500 physicians and advanced practice providers from ~200 UC centers. Although the SPUC supported the project, clinicians did not have to be members to participate in the study. A recruitment webinar in February 2019 provided details for participation: Each institution needed a minimum of 3 providers to each commit to submitting 10 patient encounters per month (or at least 30 charts per month for those with <3 providers participating). As a recruitment incentive, we offered American Board of Pediatrics Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Part 4 credit to eligible pediatricians participating in the study. From March 2019 to May 2019, participants submitted data on 10 sequential patients who received antibiotics to identify the diagnoses for which UC clinicians prescribed antibiotics. From these submissions, 3 target diagnoses were chosen: AOM, otitis media with effusion (OME), and pharyngitis. We chose AOM and pharyngitis because these were the most common diagnoses for which UC clinicians prescribed antibiotics. OME accounted for only 3% of diagnoses to receive antibiotics, but we believed that it was important to evaluate the prescribing practices for OME at the same time as AOM. To minimize participant attrition, we limited the intervention period to 9 months of active participation (March 2019 to December 2019), with the final project evaluation coinciding with submission for MOC credit. Live webinars each month were convened to review the deidentified aggregate results and discuss barriers and successes of the study. Subject matter experts on antibiotic stewardship and QI science provided didactic sessions during the webinars. Attending the webinars was a requirement for participation; however, webinars were recorded, and participants were able to self-report that they had reviewed the recorded version.

Data Collection

The study collection period occurred from June 2019 to November 2019. Each month, there was a 2-week data collection period when participants entered data on antibiotic prescribing practices for sequential cases of diagnosed AOM, OME, or pharyngitis. Clinicians completed data entry on all encounters with these diagnoses until they reached a total of 10 for that month. Data collected included patient demographics, target primary diagnosis, codiagnoses, clinical characteristics (medication allergies and type of reaction, comorbidities, recent health history, diagnostic orders), type of antibiotic prescription (none, during visit, immediate fill, or delayed prescription), and antibiotic prescription information (agent, dose, frequency, and duration). All data were submitted through Research Electronic Data Capture12,13 (Supplemental Information 1).

Interventions

The MITIGATE Antimicrobial Stewardship Toolkit: A Guide for Practical Implementation in Adult and Pediatric Emergency Department and Urgent Care Settings14,15 served as the source for all the project’s interventions. During the first plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle, we required all participating sites to sign and post a letter of commitment to antibiotic stewardship.16 No site reported having a commitment letter posted before the intervention period. The leadership team collated a menu of intervention choices from publicly available content covering a variety of strategies from which each center could choose to implement during the intervention period, including provider clinical education, provider communication training, parent engagement, and patient engagement tools. Because of the variability of resources available at each UC center, each site had autonomy to choose 2 interventions to implement during the second and third PDSA cycles that would best address the causes they identified for unnecessary antibiotic prescribing (Supplemental Table 3).

Measures

For our primary outcome measure, we evaluated the rate of overall inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions for all target diagnoses. To determine antibiotic appropriateness for each encounter, the leadership team developed algorithms using the 2013 AAP guidelines for AOM, the 2004 American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery and AAP joint guidelines for OME, and the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for group A streptococcal pharyngitis (Supplemental Information 2).17-19 We used a 3-tiered classification system from previously published literature to determine if antibiotics were appropriate, taking into consideration any associated codiagnoses.20-22 Tier 1 diagnoses included conditions for which antibiotics are almost always indicated. Tier 2 diagnoses included conditions for which antibiotics may be indicated, including for AOM and pharyngitis. Tier 3 diagnoses included conditions for which antibiotics are not indicated or the indication is unclear, including OME. Submitted encounters of any of the target diagnoses, including OME, with a codiagnosis in tier 1 or tier 2 were assumed to have been prescribed antibiotics appropriately (Supplemental Information 2A)

We reviewed encounters of uncomplicated AOM for appropriateness. We considered amoxicillin as the appropriate antibiotic agent unless the patient was allergic to penicillin or was codiagnosed with a tier 1 or 2 codiagnosis (eg, conjunctivitis). If the patient received an antibiotic other than amoxicillin, we assumed that the antibiotic agent was appropriate if the patient had any of the following: significant comorbidity (eg, immunosuppression, end-stage liver disease, chronic lung disease), recurrent AOM, or antibiotic use in the past 30 days. We reviewed antibiotic duration according to the patient’s age and prescribed antibiotic. Finally, we evaluated the encounter for eligibility in delayed prescribing and if prescription type (immediate vs delayed) was appropriate (Supplemental Information 2B). Due to the limitations of the study design, the scope of the study did not include diagnostic stewardship.

For patients with pharyngitis as their primary diagnosis, we considered any patient with a codiagnosis of viral upper respiratory infection (URI) or who was <3 years of age with a streptococcal test as inappropriately tested. If patients were appropriately tested, we then considered them to be appropriately treated only if the test result was positive. We considered amoxicillin or penicillin as the appropriate antibiotic choice unless a tier 1 or 2 codiagnosis was present or there was a documented penicillin allergy (Supplemental Information 2C).

We also measured the individual rate of inappropriate antibiotics for AOM, OME, and pharyngitis. In secondary analyses, we evaluated which factor in prescribing practices (indication, agent, or duration) contributed to categorization as inappropriate use for each diagnosis. Additionally, we evaluated the frequency with which participants engaged in best practices for antibiotic prescriptions for AOM and pharyngitis. We evaluated the frequency of AOM encounters that qualified for a period of observation18 and received delayed antibiotics. For pharyngitis we evaluated how often patients <3 years of age or with a codiagnosis of URI underwent streptococcal testing.

The process measure of live webinar attendance by participants was used to evaluate the level of engagement in the project. For this measure, we evaluated the percentage of participants who attended the live webinar each month. We used the percentage of all encounters that included laboratory (excluding rapid streptococcal antigen testing) or radiology orders as a balancing measure to evaluate if the interventions were resulting in increased resource use.

Analysis

We exported data from Research Electronic Data Capture to Microsoft Excel and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for analysis. Demographic characteristics of the patients for each diagnosis were compared using χ2 test. Because of the short duration of the study and limited number of data points, we used a line graph to trend the rates of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions for all encounters and for individual diagnoses. We tracked process and balancing measures on line graphs as well. We performed secondary analyses of the data to identify future areas for improvement using line graphs and Pareto charts. We used χ2 test to detect changes from the beginning of the intervention period to the end. We did not report results at the individual level to decrease reporting bias by participants and preserve anonymity. In previous studies, evaluation at the individual level confounded results through cross contamination of practice changes and increased hesitation in participation.23 The study team provided participants with feedback using the global deidentified site data during monthly webinars. The institutional review board at Children’s Mercy Kansas City determined that this study did not involve research as defined by Department of Health and Human Services regulations.

RESULTS

Participants

Of ~500 members of the SPUC, our recruitment goal was 30 participants. We exceeded this goal with 157 participants in this study. These clinicians serve 20 US institutions with freestanding pediatric UC centers (4 West, 6 Midwest, 7 South, 3 Northeast).

Interventions

The interventions selected for each PDSA cycle are listed in Table 1. Ten sites (50%) chose provider education for at least 1 of their interventions. Sites also chose interventions that included parent engagement (40%), communication training (35%),10 and social media (30%) during the intervention period.

TABLE 1.

Intervention Choice and Rates of Inappropriate Antibiotic Use

| Site | Baseline Average (Jun), % |

PDSA Cycle Average, % | Improvement From Baseline, Relative % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After Cycle 1a (Jun–Jul) |

Cycle 2b | After Cycle 2 (Aug–Sep) |

Cycle 3b | After Cycle 3 (Oct–Nov) |

|||

| 1A | 60.0 | 67.5 | Communication training | 20.0 | Parent engagement | 20.0 | 66.7 |

| 2A | 75.0 | 76.8 | Provider education | 30.2 | Communication training | 17.9 | 76.1 |

| 3A | 40.0 | 51.9 | Provider education | 34.8 | Provider education | 29.4 | 26.5 |

| 4A | 63.8 | 55.2 | Provider education | 30.6 | Parent engagement | 26.7 | 58.2 |

| 5A | 61.5 | 47.1 | Provider education | 15.2 | Communication training | 32.9 | 46.5 |

| 6A | 50.0 | 47.6 | Social media | 19.2 | Delayed prescribing | 13.6 | 72.8 |

| 7A | 47.1 | 48.3 | Delayed prescribing | 20.0 | Provider education | 38.1 | 19.1 |

| 10A | 53.8 | 53.1 | Provider education | 16.5 | Patient engagement | 12.2 | 77.3 |

| 12A | 65.4 | 61.5 | Provider education | 43.3 | Communication training | 44.2 | 32.4 |

| 13A | 60.7 | 54.9 | Parent engagement | 17.1 | Patient engagement | 24.0 | 60.5 |

| 14A | 42.9 | 49.2 | Delayed prescribing | 16.1 | Provider education | 8.3 | 80.7 |

| 15A | 55.4 | 53.6 | Delayed prescribing | 26.8 | Provider education | 31.3 | 43.5 |

| 16A | 65.5 | 58.0 | Parent engagement | 36.7 | Communication training | 40.0 | 38.9 |

| 17A | 62.3 | 58.3 | Provider education | 25.5 | Communication training | 28.4 | 54.4 |

| 18A | 70.0 | 54.8 | Parent engagement | 36.5 | Delayed prescribing | 26.9 | 61.6 |

| 19A | 91.7 | 86.7 | Social media | 83.3 | Communication training | 16.7 | 81.8 |

| 24A | 79.5 | 78.4 | Parent engagement | 46.2 | Social media | 53.4 | 32.8 |

| 25A | 50.0 | 44.1 | Parent engagement | 31.3 | Social media | 25.0 | 50.0 |

| 27A | 93.3 | 88.0 | Parent engagement | 70.0 | Social media | 72.7 | 22.1 |

| 29A | 72.2 | 60.4 | Parent engagement | 8.3c | Social media | —d | 88.5 |

Specific interventions grouped into categories are listed in Supplemental Table 3.

A commitment letter was required for PDSA cycle 1.

Individual sites chose from a menu of intervention options adapted from the CDC toolkit for PDSA cycles 2 and 3.

Data for August only.

No data for October and November.

Demographics

Participants submitted data on 3833 encounters during the intervention period (June to November 2019). Demographics of the encounters are listed in Table 2. AOM was the most common diagnosis (52.0%), followed by pharyngitis (40.9%) and OME (7.1%).

TABLE 2.

Patient Demographics for the 3 Target Diagnoses

| Patient Characteristic (N = 3833) | AOM (n = 1994, 52.0%) | OME (n = 272, 7.1%) | Pharyngitis (n = 1567, 40.9%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–6) | 7 (4–10) | < .01 |

| Race | .06 | |||

| White | 1390 (69.7) | 206 (75.7) | 1068 (68.2) | |

| Black | 170 (8.5) | 14 (5.2) | 154 (9.8) | |

| Unsure | 434 (21.8) | 52 (19.1) | 345 (22.0) | |

| Language | .01 | |||

| English | 1744 (87.5) | 255 (93.8) | 1408 (89.9) | |

| Other | 138 (6.9) | 12 (4.4) | 111 (7.1) | |

| Unsure | 111 (5.6) | 5 (1.8) | 48 (3.1) | |

| Insurance | .44 | |||

| Commercial | 1084 (54.4) | 162 (59.6) | 845 (54.0) | |

| Public | 712 (35.7) | 81 (29.8) | 579 (36.9) | |

| Military | 62 (3.1) | 6 (2.2) | 39 (2.5) | |

| None | 52 (2.6) | 8 (2.9) | 43 (2.7) | |

| Unsure | 84 (4.2) | 15 (5.5) | 61 (3.9) | |

| Codiagnosis | ||||

| Tier 1 or tier 2 | 276 (13.8) | 18 (6.6) | 95 (6.1) | < .01 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. IQR, interquartile range.

Outcome Measures

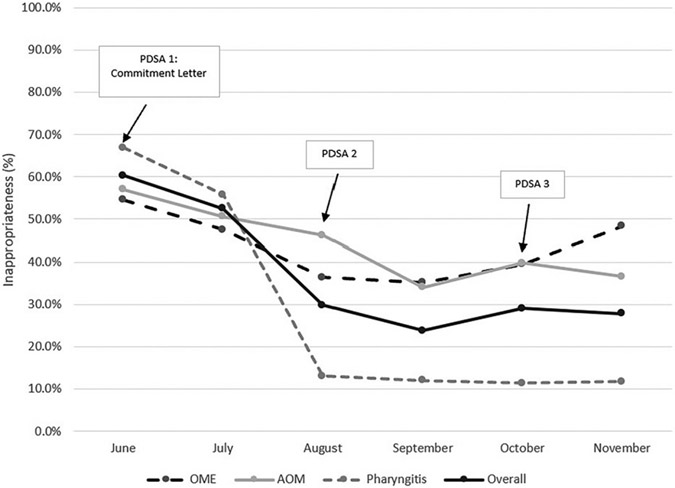

At the beginning of the intervention period, 60.3% of all patient encounters resulted in an inappropriate antibiotic prescription. This rate decreased to 27.8% by the end of the intervention period (P < .01). The rates of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions decreased in AOM and pharyngitis from 57.0% and 66.9% to 36.6% and 11.7%, respectively (P < .01). The rates of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions for OME did not decrease (P = .67). Because OME was a small proportion of the patient encounters, encounters for AOM and pharyngitis drove the improvement in the overall rates of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

Rates of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions overall and for each target diagnosis by month.

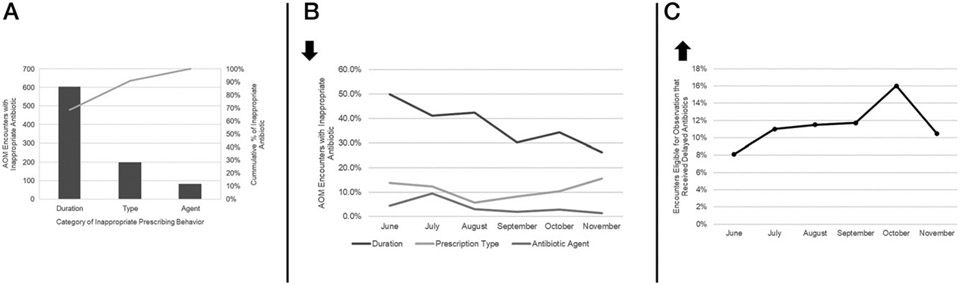

The most common error in prescribing for AOM was inappropriate duration (Fig 2A). Rates of inappropriate duration for AOM encounters improved over time from 49.9% to 26.2% (P < .01). However, the rate of inappropriate antibiotic choice (P = .11) and type of prescription (P = .75) did not improve (Fig 2B). AOM encounters with delayed antibiotic prescriptions made up 8.1% of encounters at the beginning of the intervention period and increased to a high of 15.9% during PDSA cycle 3; however, the improvement was not sustained and was 10.0% by the end of the intervention period (Fig 2C).

FIGURE 2.

A, Pareto chart of category of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions for AOM encounters. B, Rates of inappropriate prescribing behaviors for AOM encounters over time. C, Rates of delayed antibiotics for AOM encounters eligible for a period of observation according to national guidelines.

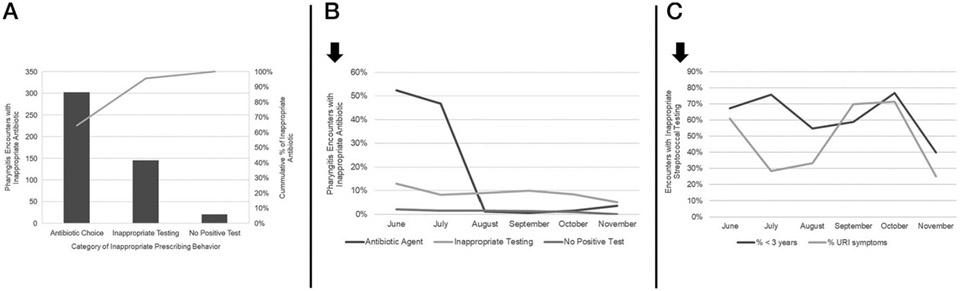

For pharyngitis, the most common factor contributing to inappropriate prescriptions was antibiotic choice (Fig 3A). This rate improved over time from 52.4% to 3.6% (P < .01). However, the rate of inappropriate testing (P = .08) and treating without a test (P = .18) did not change significantly (Fig 3B). Sustained improvement also was not seen in inappropriate streptococcal testing for patients with concurrent URI symptoms or <3 years of age during the intervention period (Fig 3C). Of the 131 encounters with inappropriate streptococcal testing, 28% (n = 37) were prescribed an antibiotic.

FIGURE 3.

A, Pareto chart of category of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions for pharyngitis encounters. B, Rates of inappropriate prescribing behaviors for pharyngitis encounters over time. C, Rates of streptococcal testing in patients with concurrent URI symptoms or <3 years of age.

Process and Balancing Measures

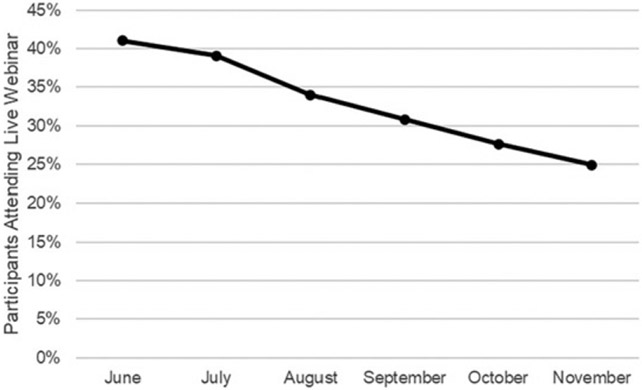

The percentage of participants who attended the live webinar decreased over time, with the lowest attendance at the end of the intervention period (41.0% vs 24.2%) (Fig 4). The percentage of encounters resulting in laboratory testing (excluding rapid streptococcal antigen testing) remained stable (34.9% vs 36.8%). The percentage of encounters with radiology orders decreased during the intervention period (2.0%–1.0%).

FIGURE 4.

Percentage of participants who attended live webinars each month.

DISCUSSION

In this first multisite pediatric UC QI collaborative, we improved antibiotic prescribing practices in AOM, pharyngitis, and OME using publicly available intervention tools. We show a relative decreased rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions by 53.9%, and the relative rate of inappropriate antibiotic use decreased by 35.8% in AOM and 82.5% in pharyngitis.

Our process measures of webinar attendance did not correlate with the improvement we saw in the outcome measure. Although the webinars provided expert content at the global level, the interventions at the local level may have had a larger impact on the outcome measure. Despite the decrease in live webinar viewing, antibiotic prescribing practices improved with each PDSA cycle, with more appropriate antibiotic choices for pharyngitis encounters and appropriate duration for AOM encounters driving the overall improvement. Although antibiotic choice improved, inappropriate testing in patients with pharyngitis still resulted in 28% of patients being exposed to antibiotics. Continued focus on appropriate testing in pharyngitis should be further explored to overcome barriers to more judicious antibiotic prescribing.

This project did not increase the rate of offering delayed prescriptions for eligible patients diagnosed with AOM to reduce antibiotic use,11 a finding consistent with previous studies revealing that clinicians have been slow to adopt using a period of observation before prescribing antibiotics in mild cases of AOM.24 Because the relationship between the patient and UC provider is limited to the duration of a single visit, UC providers reported hesitancy to delay treatment, citing inability to monitor progression of illness or guarantee follow-up.24 Researchers should explore the barriers to UC providers’ limited use of delayed prescribing.

Pediatric UC providers prescribed antibiotics for more than one-half of OME encounters, a prescribing rate similar to that reported by Palms et al.6 By the end of the intervention period, inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions for OME had decreased to 48.4%, which is similar to the frequency reported for emergency departments and retail clinics but still higher than medical offices.6 Studies have revealed that health care providers are more likely to prescribe antibiotics when none are indicated if they perceive that families are expecting antibiotics.25 However, although some families may expect antibiotics, patient satisfaction scores have been shown to be highest in patients who did not receive antibiotics but were provided positive recommendations for nonantibiotic treatment options, including supportive care and a contingency plan.26 Although accounting for a small portion of encounters, as a never-diagnosis, OME could be explored as a future diagnosis to evaluate integration of watchful waiting as an intervention option in the setting of a pediatric UC to successfully decrease inappropriate use of antibiotics.

Ideally, the project would have lasted an entire year to capture the variation in seasonal illnesses; however, best practice of implementation science demands that the culture and environment be accounted for to successfully complete an intervention.27 Requiring increased attendance (webinars, onsite meetings) and activities (submitting case data, completing education modules) for shift workers in the high-pace, high-volume time of winter respiratory season would have placed undue pressure on the participants and affected their ability to complete the requirements for participation. Our project involved low-reliability interventions28 that challenge the ability to sustain improvement after the project concludes. However, our hope is that this antibiotic stewardship initiative provided a foundation for UC centers to develop their own local antibiotic initiatives that consider the people and systems unique to each UC center.

Although this study involved 20 pediatric UCs across the United States, generalizability may be limited. As with all QI studies, the interventions do not occur in a vacuum. It is possible that there were competing local projects at individual UC centers that may have influenced the results of our multicenter study. However, no centers identified competing projects during the intervention period when we asked for program feedback at the close of the project. In the absence of a national registry, we relied on the integrity of the providers to report their individual prescribing practices to collect data, which is at risk for bias. Participants’ prescribing behavior may have been influenced because they knew their prescribing patterns were being monitored or because MOC credit was being offered to eligible participants. We minimized the selection bias by instructing participants to report prescribing practices on 10 sequential encounters with the target diagnoses for each month during the collection period. We also limited the analyses to site-level data, leveraging anonymity at the individual level to improve integrity in reporting.29

Unlike traditional QI studies, ours did not have uniform interventions applied to all settings at the same time. Using methods from implementation and dissemination science, we allowed each UC center to choose the intervention that would best address their identified barriers to appropriate antibiotic prescribing. Because of the relatively resource-poor settings in which our participants practice, we relied on publicly available resources for our interventions. Although these resources have low reliability,28 they are affordable, accessible, and easy to implement without significant investment of finances or time. Our results reveal that low-reliability interventions affected the intended outcome without significant barriers in implementation. However, we recognize that these changes are difficult to maintain because new people enter the system and humans fall back on old habits. Future work is needed to embed these changes into the UC system by incorporating antibiotic stewardship initiatives into local onboarding processes, annual mandatory education, audits, and national benchmarking.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Magna Dias and the SPUC Board of Directors for spurring the collaboration of organizations involved to accomplish the study goals. In addition, the authors thank the participating clinicians for their leadership, enthusiasm, and dedication to the study.

FUNDING:

This work was supported by departmental funds of Drs Nedved and Montalbano; in-kind support from the Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, for data management and analysis; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for subject matter expertise. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- AOM

acute otitis media

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- MOC

Maintenance of Certification

- OME

otitis media with effusion

- PDSA

plan-do-study-act

- QI

quality improvement

- SPUC

Society of Pediatric Urgent Care

- UC

urgent care

- URI

upper respiratory infection

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: The authors have indicated they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black LI, Zablotsky B. Urgent care center and retail health clinic utilization among children: United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 393. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Society for Pediatric Urgent Care. Mission statement. Available at: https://urgentcarepeds.org/. Accessed December 13, 2021

- 3.Montalbano A, Rodean J, Kangas J, Lee B, Hall M. Urgent care and emergency department visits in the pediatric Medicaid population. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20153100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P T. 2015;40(4):277–283 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lushniak BD. Antibiotic resistance: a public health crisis. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(4):314–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palms DL, Hicks LA, Bartoces M, et al. Comparison of antibiotic prescribing in retail clinics, urgent care centers, emergency departments, and traditional ambulatory care settings in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9):1267–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frost HM, McLean HQ, Chow BDW. Variability in antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory illnesses by provider specialty. J Pediatr. 2018;203:76–85.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun D, Rivas-Lopez V, Liberman D. A multifaceted quality improvement intervention to improve watchful waiting in acute otitis media management. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2019;4(3):e177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frost HM, Monti JD, Andersen LM, et al. Improving delayed antibiotic prescribing for acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2021;147(6):e2020026062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kronman MP, Gerber JS, Grundmeier RW, et al. Reducing antibiotic prescribing in primary care for respiratory illness. Pediatrics. 2020;146(3):e20200038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerber JS, Jackson MA, Tamma PD, Zaoutis TE; Committee on Infectious Diseases, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Antibiotic stewardship in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2021;147(1):e2020040295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. ; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap Consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Be Antibiotics Aware Partner Toolkit. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/week/toolkit.html. Accessed June 3, 2022

- 15.May L, Yadav K, Gaona SD, et al. MITIGATE antimicrobial stewardship toolkit: a guide for practical implementation in adult and pediatric emergency department and urgent care settings. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/80653. Accessed June 3, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yadav K, Meeker D, Mistry RD, et al. A multifaceted intervention improves prescribing for acute respiratory infection for adults and children in emergency department and urgent care settings. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(7):719–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion (update). Available at: https://www.entnet.org/quality-practice/quality-products/clinical-practice-guidelines/ome/. Accessed June 3, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2014;133(2):346]. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e964–e999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(10):1496]. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):e86–e102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among us ambulatory care visits, 2010–2011. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1864–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapiro DJ, Hicks LA, Pavia AT, Hersh AL. Antibiotic prescribing for adults in ambulatory care in the USA, 2007–09. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(1):234–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, Shah SS. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1053–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrison MM, Mangione-Smith R. Cluster randomized trials for health care quality improvement research. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(suppl 6):S31–S37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamdy RF, Nedved A, Obremskey JC, Fung M, Liu C, Montalbano A. Pediatric urgent care providers’ approach to antibiotic stewardship: a national survey. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6:S398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mangione-Smith R, McGlynn EA, Elliott MN, Krogstad P, Brook RH. The relationship between perceived parental expectations and pediatrician antimicrobial prescribing behavior. Pediatrics. 1999;103(4 pt 1):711–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangione-Smith R, McGlynn EA, Elliott MN, McDonald L, Franz CE, Kravitz RL. Parent expectations for antibiotics, physician-parent communication, and satisfaction. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(7):800–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health. Implementation science news, resources and funding for global health researchers. Available at: https://www.fic.nih.gov/ResearchTopics/Pages/ImplementationScience.aspx. Accessed December 13, 2021

- 28.Stevens P, Campbell J, Urmson L, Damignani R. Building safer systems through critical occurrence reviews: nine years of learning. Healthc Q. 2010;13:74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health (Oxf). 2005;27(3):281–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.