Abstract

Sleep disorders frequently result in poor memory, attention deficits, as well as a worse prognosis for neurodegenerative changes, such as Alzheimer's disease. The purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of sleep disorders on cognition. We screened four databases for all meta-analyses and systematic reviews from the establishment through March 2022. We have carried out quality evaluation and review the eligible systematic reviews. Evidence grading and quality assessment were performed on 22 eligible articles. Sleep deprivation primarily affects simple attention, complex attention, and working memory in cognition and alertness. The moderate-to-high-quality evidence proves optimal sleep time as 7–8 h. Sleep time outside this range increases the risk of impaired executive function, non-verbal memory, and working memory. Sleep-related breathing disorders is more likely to cause mild cognitive impairment and affects several cognitive domains. In older adults, insomnia primarily affects working memory, episodic memory, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, problem-solving, operational ability, perceptual function, alertness, and complex attention, and maintaining sensitivity. Sleep disturbances significantly impair cognitive function, and early detection and intervention may be critical steps in reducing poor prognosis. A simple neuropsychological memory test could be used to screen people with sleep disorders for cognitive impairment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s41105-022-00439-9.

Keywords: Sleep disorder, Cognitive impairment, Dementia, Overview of systematic reviews

Introduction

Sleep is a complex physiological and behavior-connected process, determining quality of life, while having an impact on longevity by affecting metabolic processes, with a prevalence of 20–30% reported by The Global Adult Epidemiological Survey [12]. Affected metabolic processes include early insulin resistance, obesity, type 2 diabetes, aging, and others [31, 60]. Insomnia, sleep-related breathing disorders, central disorders of hypersomnolence, circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders, hypersomnia, sleep-related movement disorders, and other sleep disorder are all classified as sleep disorders in the third edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) [58]. According to the 2021 White Paper on Exercise and Sleep, over 300 million Chinese suffer from sleep disorders. The factors influencing sleep include the circadian rhythm system, specific neural circuits that aid in sleep homeostasis, the neuroendocrine system, genetics, and environmental variables [54], interacting at multiple levels and play a role in the mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD)/Parkinson's disease with dementia (PDD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and multiple system atrophy (MSA) [54].

The Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care, published in 2017, attributed approximately 35% of dementia to education, high blood pressure and obesity in middle age, hearing loss, late-life depression, diabetes, physical inactivity, smoking, and social isolation, but did not include sleep disorders [43]. However, the committee in the 2020 update did acknowledge sleep disturbances as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease [44]. The question of whether sleep disruption is a risk factor for dementia has piqued interest of experts. Our analysis of systematic reviews included the two meta-analyses they utilized as evidence [8, 62].

The impact of sleep disorders on cognitive performance has become a major concern. There have been numerous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies published on this topic. In addition to clinical trials, bioinformatics analyses are being conducted, with inconsistent results. A gene-wide association study (GWAS) published in 2021 used Mendelian Randomization to estimate the causal effect of Alzheimer's disease risk using self-report and accelerometer-measured sleep parameters. The authors concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support a causal effect of sleep traits on AD risk; however, they acknowledged that this conclusion should be confirmed in an independent replication study [3].

There are conflicting viewpoints on whether sleep impacts cognition as a result of such a heated dispute. A vast number of academics have undertaken systematic reviews and meta-analyses to provide evidence-based medicine recommendations for clinical work. Sleep disorders, on the other hand, come in a variety of forms. In addition, definitions and testing methodologies for the cognitive field in different researches are not unified, and there is currently no widely accepted normative standard. As a result, existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been reviewed from a variety of angles, and coverage may be incomplete or repetitious. As a result, a systematic collection or overview is created to aid scholars working on this topic in rapidly and rationally reviewing past findings.

Overview of systematic reviews is a strategy that requires comprehensively collecting relevant systematic reviews on the treatment or etiology, diagnosis, and prognosis of the same disease or clinical condition, and then conducting comprehensive research. The goal of this overview of systematic reviews is to completely tease out and provide insight into the impact of various forms of sleep disorders on cognition using meta-analysis and systematic reviews. Second, assess the quality of data to establish the efficacy of sleep disorders' impact on cognition and identify research gaps. The overarching goal is to assist physicians in understanding the significance of sleep disturbance in the progression of Alzheimer's disease and to use evidence to highlight sleep interventions.

Methods

Literature search

From the establishment through May 2022, we searched PubMed, PsychInfo, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect. Used the following search terms: sleep disorders, sleep restriction, sleep fragmentation, sleep deprivation, insomnia, sleep-disordered breathing, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, sleep duration, or hypersomnia combined with executive function, cognition, cognitive impairment, dementia, Alzheimer's disease, neuropsychological function, memory, inhibitory control, task shifting, task switching, mental flexibility, decision making, attentional control, attention, verbal fluency, psychomotor vigilance, intelligence, recall, response time, reaction time, delay discounting, meta, systematic review. The publication type was limited to systematic reviews. For pertinent citations not captured in the computerized search, we manually searched the list of references for the selected literature. Find the whole article by searching for past research by the author for conference minutes that fit the topic. There were no language restrictions.

Study selection

In a two-step process, two researchers independently selected relevant reviews. First, review titles and summaries to identify potential qualifications. The full text was then retrieved for further analysis. Any disagreements about inclusion were settled through consensus.

We adhere to the following inclusion criteria to select articles that fit the theme of the cognitive impact from sleep disorders:

The target population consisted of adults reporting sleep disturbances. The normal control group consisted of adults who did not have sleep problems.

The outcome was an objective measure of cognitive changes, including but not limited to all-cause cognitive impairment, cognition, cognitive impairment, dementia, Alzheimer's disease, executive function, memory, visual ability, language ability, inhibitory control.

Considering the ethical implications of additional interventions, existing systematic reviews were dominated by observational studies, including community-based, population-based data, prospective or retrospective cohort studies, as well as case–control, cross-sectional studies, and a small number of RCT. We accept all types of the primary studies for the systematic reviews.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were among the types of literature included, and detailed characterization of primary studies was also available. Examine the original text's methodological quality as well as the plausibility of heterogeneity and bias analysis to determine whether they should be included

We excluded non-adult studies and articles, where detailed information could not be extracted from primary studies, and we limited the subjects to those over the age of 20. In the event of a duplicate release, we chose the newer or more complete version. Adults with severe cognitive or sleep impairments, such as mental disorders, heart failure, cancer, or a history of stroke, were excluded. Sleep disorders in specific populations, such as epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, depression, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia, were also excluded. These patients typically score extremely high on a neuropsychological test, implying that the baseline conditions cannot be controlled. Furthermore, because neurodegenerative disease is the leading cause of cognitive impairment and, eventually, dementia, distinguishing causative links between sleep disorders and cognitive impairment is difficult [1]. It is often difficult to distinguish between the preclinical phases of dementia and the clinical indications of mild cognitive impairment. Some researchers may not even classify mild cognitive impairment and preclinical dementia using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Global Deterioration Scale (GDS), or Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR). It reduced the difference in prognosis between the experimental and control groups by making the presence of preclinical dementia related to primary illness a residual factor. Furthermore, the primary illness population's cognitive exam results may be unstable, which could be related to the disease's clinical signs or prognosis rather than merely cognitive impairment induced by sleep disruption. All of this made it difficult to appropriately quantify the results' robustness. We did not include the effect of treating sleep disorders on cognitive improvement, because it is not in line with the topic of this paper at first, and such systematic reviews are few and difficult to stratify. (A list of studies excluded by full-text review is shown in Supplementary Table 1.)

Extract the data

Two researchers extracted the distinctive information of the included study separately. We utilized a pre-designed table to extract information (Supplementary Table 3).

Assessment of quality of included reviews

Methodological quality

The two authors independently assessed the methodological quality of the included reviews using AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) 2 across sixteen domains [30, 61]. AMSTAR 2's sixteen questions assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. Because the AMSTAR 2 score can mask important flaws, lowering confidence in systematic review results, seven critical domains were chosen to be followed, namely, items 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 [61]. Overall confidence is rated as high if there was no or one non-critical weakness, moderate if there were multiple non-critical weaknesses, low if there was one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses, and critically low if there were multiple critical flaws with or without non-critical weaknesses (Supplementary Table 2).

GRADE scoring

We used the GRADE guidelines to determine the strength of the evidence (Supplementary Table 3) [27, 39]. Because the primary studies are mostly observational, we gave each review a score of two at first.

If the primary study contains the following factors, we may consider lowering the quality strength of evidence: (1) the study design and implementation are insufficient, and bias is very likely to exist; (2) indirect evidence; (3) unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistencies in results; (4) the accuracy of results is insufficient; and (5) there is publication bias [59].

We should consider enhancing the quality of systematic review evidence if the primary study contains the following factors: (1) the effect value is large. (2) relevant confounders may diminish efficacy, and when methodologically rigorous observational studies reveal considerable or very significant efficacy and consistent results, we will have more confidence in the results. Observational studies are tended to overstate efficacy in these circumstances, but study design restrictions cannot account for the full effect. (3) dose–effect relationship [35, 59].

Factors that could lower or raise the quality of evidence were considered. We compared total GRADE scores based on the quality of four types of evidence: high (at least 4 points), medium (3 points), low (2 points), and very low (2 points) (1 point or less).

Result

Study selection

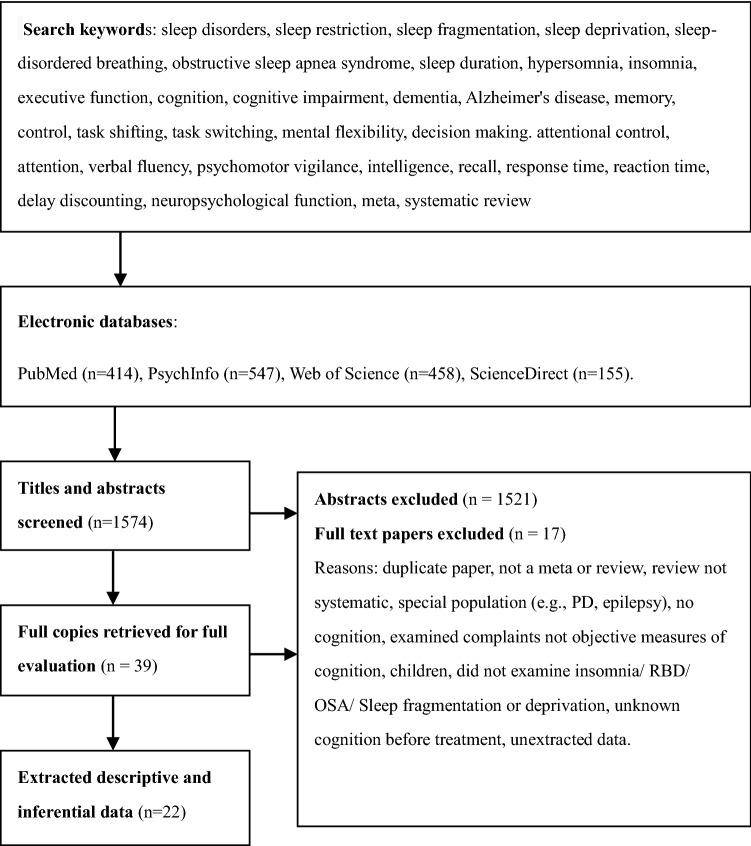

From four databases, 1574 records were identified (Fig. 1). Hand-searching reference lists yielded 16 additional studies.

Fig. 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram. This flow diagram includes a summary of the results from study identification and screening, the excluded studies with reasons, and the number of studies included in the systematic review

We thoroughly reviewed 39 articles. Four of the papers were neither systematic reviews nor meta-analyses [2, 10, 51, 64]. Four papers were studied in special populations, namely, people with primary nervous system diseases [19, 47, 48, 55]. Three papers involved or included children [21, 46, 63]. Four studies [17, 38, 57, 69] did not include cognitive performance as a measure of success. One study looked at the risk of OSA in people with Alzheimer's disease [21]. Another study [41] looked at the influence of sleep on the advantage of prospective memory, which is not relevant to our topic. A manuscript was written that contained minors in part, but no data analysis was done. Only the therapeutic effects of CPAP on cognition in elderly adults with OSA were investigated [9]. After some deliberation, we decided to partially include this article and exclude the systematic review conclusions generated by including minors. Finally, 22 systematic reviews matched the inclusion criteria and were chosen to be included in this review.

Characteristics of reviews

Full-text screening yielded 22 qualified reviews, totaling 623 primary studies, including RCTs, cross-sectional studies, and longitudinal studies. The trials in the inclusion systematic review had big enough sample sizes, with a mild to moderate risk of bias. Three reviews had a high GRADE, and two points were added for a substantial effect size and a dose–effect association between sleep duration and cognitive impairment [42, 72, 73]. For offering an appropriate effect size and no downgrading factor, fifteen of them were graded medium [5, 7–9, 14, 16, 22–24, 34, 40, 45, 62, 68, 70, 74]. Due to various downgrade causes, two of the remaining reviews are classified as extremely poor [52, 53] and two as low [7, 65].

Multiple sleep issues are reported in these 22 systematic reviews. In three articles [34, 52, 53], sleep deprivation was mentioned. Sleep length was discussed in four articles [22, 42, 45, 72]. Sleep-disordered breathing, namely, sleep apnea syndrome, was linked to cognitive impairment in eight studies [7, 9, 14, 24, 40, 65, 68, 74]. In addition to subjective and objective insomnia, there are four further reports on insomnia [5, 16, 23, 70]. The effects of a specific sleep disorder on cognition are the focus of all of the above reviews. Three research [8, 62, 73] looked at which sleep difficulties were associated with cognitive impairment, dementia, Alzheimer's disease, or vascular dementia, but they did not identify the cognitive domain. Supplementary Table 3 provides more information on the attributes.

Sleep deprivation

In the three meta-analyses, the effect size d value was obtained using variance analysis. Two of them had low quality scores, while the other had a medium score. All three supported the damages of sleep deprivation on human function, resulting in poor overall performance and cognitive impairment. The effects of sleep deprivation on memory (d = − 0.771) and cognitive performance (d = − 0.560) were moderate in the group of physicians studied by Philibert et al., but more so on vigilance (d = − 0.904) [52]. Lim et al. are concerned about the affected cognitive domain, with effect sizes for simple attention ranging from − 0.762 (error) to − 0.732 (response time), indicating moderate to substantial effects. The effect sizes of complex attention (all attentional processes, accuracy − 0.479, response time − 0.312) and working memory (accuracy − 0.555, response time − 0.515) were in the medium range, while the processing speed test average effect sizes were moderate but significant [34].

< 5 h [53]. Interestingly, they discovered that partial sleep deprivation had the greatest influence on overall performance (d = − 2.04), followed by long-term sleep deprivation (d = − 1.27) and short-term sleep deprivation (d = − 1.21). Partial sleep deprivation, in particular, had the greatest effect on cognitive performance (d = − 3.01) and mood (d = − 4.10). Philibert et al., who studied a specific group of physicians, classified their sleep deprivation as 24 to < 30 h, 30 to < 54 h, and ≥ 54 h [52]. Chronic partial sleep deprivation has a correction d of − 0.886, which is not as high as other sleep deprivation segments. Long-term sleep deprivation had a bigger impact on cognition and general performance than short-term sleep deprivation, according to the authors of the two meta-analyses; however, partial sleep deprivation results were mixed. In this approach, Pilcher et al. looked at the stratified effects of difficulty and task length on cognitive performance assessments rather than the duration of partial sleep deprivation. Despite the fact that Philiber et al. did not specify the length of chronic partial sleep deprivation, the general description and outcomes of "chronic" appear to be more in line with public perception.

Sleep duration

To calculate RR or HR values, the four meta-analyses included used regression analysis. Sleep duration was also discussed in two other studies that considered sleep disorders as a risk factor for cognitive impairment [8, 73]. Three of the six providing a dose–response relationship received a high GRADE score [42, 72, 73], while the other three were rated as medium [8, 22, 45]. Except for one review in which Fan et al. found that short sleep duration was not associated with future risk of all-cause dementia or Alzheimer's disease [22], they all agreed that both short and long sleep duration was associated with cognitive impairment. Furthermore, the degree of the risk of impairment in various cognitive areas linked with short and long sleep duration is inconsistent. Nonetheless, longer sleep appears to be connected with a higher risk than shorter sleep. The meta-analysis of changes in sleep characteristics conducted by Xu et al. found that increasing sleep duration, rather than decreased sleep duration, significantly increased the risk of cognitive impairment [73].

Three studies found a non-linear dose–response relationship between sleep duration and cognitive impairment or dementia/AD in the shape of a “U” or “J” [42, 72, 73]. Bubu et al., Wu et al., and Liang et al. all agreed that 7–8 h of sleep is optimum [8, 42, 72]. Xu et al., on the other hand, are slightly different, and their findings show that 6.3 h of sleep at night and 7.3 h of total sleep each day are the most suitable [73].

Executive function, verbal memory, and working memory capacity are all impacted; however, processing speed is not changed considerably [45].

Sleep-related breathing disorders

The influence of OSA, sleep apnea, snoring, and other sleep breathing disorders on cognition was discussed in eight papers with SBD as the theme and three with a comprehensive analysis of risk factors for cognitive impairment. Two of the eleven papers received a low GRADE [7, 65]. The review by Xu et al. received a high rating, since it presented a dose–response relationship for sleep duration, but it was equivalent to a moderate rating in terms of independent SBD assessments. The remaining seven papers received a medium rating [8, 9, 14, 24, 40, 62, 68, 74]. Eleven papers contain different effect sizes, namely, OR, d, and Hedge's g.

SBD dominated by OSA is an independent risk factor for cognitive impairment in non-dementia people, and SBD patients have a higher risk of mild cognitive impairment than dementia risk [8, 73, 74]. The connection between baseline SBD and the likelihood of eventual cognitive deterioration continued to some extent with advancing age, but sensitivity may have decreased [14, 74]. In contrast, the link between midlife OSA and later life cognition may be null in persons above the age of 60 [9]. The link between SBD and cognitive decline may differ by gender, with female SBD patients having a higher risk of cognitive impairment [74]. Both short-term and long-term continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy improved several aspects of cognition [9].

Beebe et al. and Wallace et al. conducted meta-analyses that compared OSA populations to healthy controls and normal person standard reference data [7, 68]. OSA had moderately negative effects on language capacity, long-term verbal memory, and delayed recall of verbal episodic memory when compared to normal standard reference data sets. OSA patients had severe declines in verbal episodic memory recognition and vigilance, as well as moderate declines in delayed memory of verbal episodic memory, learning, visuospatial episodic memory, and delayed memory when compared to the healthy control group data set. However, the visual memory results of Beebe et al. and Wallace et al. differed significantly, possibly due to the use of different testing procedures and scoring criteria.

Four other reviews compared SBD or OSA patients to healthy controls [14, 24, 40, 65]. Nonverbal memory (d = − 0.79), psychomotor speed (d = − 0.70), mental flexibility (d = − 0.72), visual delayed memory retrieval (d = − 0.67), and driving simulation performance (d = − 0.61) were found to be the most severely impaired in OSA patients. Working memory (d = − 0.41), verbal memory (d = − 0.39), construction (d = − 0.69), processing speed (d = − 0.52), attention (d = − 0.26–0.35), sustained attention (d = − 0.31–0.51), language delay memory retrieval (d =− 0.17), verbal fluency (d = − 0.39), and general intellectual function (d = − 0.24) were all significantly reduced. In terms of distraction and motor learning, the results were insignificant. The outcomes of the included studies varied in terms of executive function, working memory, concept formation, verbal or visual immediate memory, and motor ability.

Although Bubu et al.’s work in 2020 did not perform a meta-analysis, they grouped the middle-aged and elderly with 60-year age limit [9]. They concluded that there are modest to high relationships between OSA and cognition on several measures of attention, memory, reaction time, psychomotor vigilance, information processing speed, and executive function in young and middle-aged persons, but that this link is weak or missing in the elderly. The findings in middle age were related to daytime sleepiness, or fragmented sleepiness, produced by repeated episodes of apnea and nerve damage induced by periodic hypoxia, according to the researchers. Sleep fragmentation and excessive daytime sleepiness may be linked to attention and memory deficiencies, while motor function, executive function, response time, and vigilance may be linked to the degree of hypoxemia.

Insomnia

Four reviews on the topic of insomnia and three comprehensive sleep disorders examined insomnia problems that were reported subjectively or objectively, as shown in Supplementary Table 3 [5, 8, 16, 23, 62, 70, 73]. On the subject of insomnia, all seven articles received a medium GRADE. Insomnia is a high level of evidence of cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's disease, and preclinical Alzheimer's disease in older adults [8, 16, 62, 73].

Three papers investigated the effects of insomnia on different domains, calculating the expected loss (ES), Hedge's d, and g, respectively [5, 16, 23]. They acknowledged that insomnia has mild to moderate impacts on working memory. Retention was moderately affected, while manipulation was more severely damaged. Wardle-Pinkston et al. and Fortier-Brochu et al. investigated episodic memory and problem solving, and the findings consistently demonstrated that moderate-intensity had an impact [23, 70]. Otherwise, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and operational ability are affected to varying degrees.

In addition, vigilance, complex attention, and perceptual function (the domain of perceptual functions represents the cognitive ability to organize and analyze information encountered visually) were all linked to insomnia [16].

Other sleep problem

Short or extreme sleep duration, poor sleep quality, fragmented sleep, low sleep efficiency, daytime dysfunction, and prolonged sleep latency, as well as excessive time in bed, abnormal circadian rhythm, sleep behavior disorder, non-habitual napping, and insomnia, are all common sleep problems that affect cognition. To varied degrees, these sleep issues exacerbated cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease [8, 62, 73].

Insomnia and SBD or OSA are both high-risk variables for cognitive impairment, according to three studies. Shi et al. looked at AD, VD, and all-cause dementia in subgroups and discovered that insomnia only enhanced the risk of AD, whereas SBD was a risk factor for all-cause dementia, AD, and VD [62]. According to Bubu et al.'s subgroup analysis of AD, cognitive impairment, and preclinical AD, those with sleep disorders had a 3.78-fold higher risk of preclinical AD than those without sleep disorders. There was also a 1.55-fold increased risk of Alzheimer's disease and a 1.65-fold increased risk of cognitive impairment [8].

Discussion

In general, the impact of sleep problems on cognition is universal and extensive, but the impact of different sleep disorders on the cognitive domain varies slightly.

Among them, sleep deprivation mainly affects simple attention, complex attention, and working memory in cognition, it also affects vigilance, emotion, and clinical performance in residents and nonphysicians in residents and nonphysicians. Long-term sleep deprivation plays a key role on adverse outcomes. Long-term sleep deprivation causes tau deposition in the brain, affects cognition, and induces dementia [28]. Acute sleep deprivation with nighttime wake-ups exacerbates some of the effects of chronic sleep deprivation [13]. Therefore, acute and chronic sleep deprivation is of concern.

The optimal sleep duration is nearly 7–8 h, and sleep duration outside of this range is associated with a higher risk of impaired executive function, verbal memory, and working memory. It is not difficult to find that there are not enough meta-analyses on the effects of sleep duration in various cognitive fields. In addition, even when screened in primary studies, it is simply summed up as "multi-cognitive domain impairment", because there are no overlapping fields of study in testing cognitive domains. It made it less confident to answer the question of which cognitive domains are affected by sleep duration.

Insomnia mainly affects working memory, episodic memory, problem-solving ability, operational ability, as well as perceptual function, vigilance, and complex attention, and remains sensitive in the elderly.

In fact, SBD has the widest range of influence. SBD is more likely to cause mild cognitive impairment, with higher sensitivity in women and elderly. The affected areas are language skills, language fluency, long-term memory, verbal episodic memory, recognition and delayed recall, visual space episodic memory and delayed memory, visual delay memory retrieval, learning, construction, processing speed, vigilance and attention, and sustained attention and psychomotor speed, mental flexibility, driving simulation, general intelligence function performance. In addition the influence of inflammatory factors induced by sleep disorders, SBDs decreased oxygen saturation due to hypoxia is related to oxidative stress in the brain and impaired brain bioenergy during sleep [15, 18].

To be sure, cognitive impairment from sleep problems is real and widespread, but we're not sure which sleep problems most impaired cognition. These results are influenced by the cognitive scope and assessment methods. Distinct evaluation procedures for different cognitive domains were used in some of the primary studies in the systematic review, resulting in high heterogeneity across studies and preventing further data analysis. There is also an underlying relationship between sleep disorders. Insomnia and OSA, for example, can result in poor sleep quality, daytime drowsiness, and prolonged bed rest.

The popular belief is that napping or more sleep during the day can mitigate the damage caused by a lack of sleep at night. However, in fact, sleep–wake abnormalities and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome can cause daytime fatigue and sleepiness. However, naps and or prolonged bedtime may mask subjective feelings of sleepiness and fatigue of older with sleep disorder [50]. Although fatigue and sleepiness are two separate concepts, both chronic fatigue syndrome and excessive daytime sleepiness are associated with a higher risk of cognitive impairment, and excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with a higher risk of cognitive impairment than fatigue syndrome [49]. Early detection of sleep–wake disturbance and control of bed time may be one of the sleep health strategies to prevent cognitive impairment [25], which is consistent with the concept of maintaining an optimal sleep duration of 7–8 h.

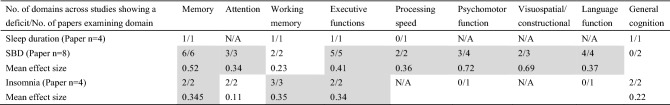

After removing the articles with very low GRADE digress, Table 1 summarizes the cognitive impairment profiles of sleep problems for ease of understanding. Memory includes, for example, episodic memory, spatial memory, immediate memory, delayed memory, and so on. This table counts the number of papers that examined the main domain as well as the number of domains that show a deficit across studies. Fortunately, the article includes only Cohen's d effect sizes. Despite the heterogeneity of meta-analyses, this quantitative method can still serve as a reference. Because of the large number of meta-analysis papers included, it is easy to find that SDB has significant cognitive impairment. However, the effect of various sleep disorders on memory is obvious to all. Slow-wave sleep (SWS) has long been thought to play an important role in memory consolidation, and during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, SO and δ waves compete to regulate memory consolidation and weakening [36]. The interaction of field potential oscillations associated with SWS promotes a gradual redistribution of connections and strengthening of neocortical network representations via neuronal replay of freshly encoded fragmented representations from the hippocampus network during slow-wave sleep [37]. Memory reactivation and restructuring are enhanced at the molecular and synaptic levels when in the rapid eye movement (REM) phase [56]. The overall sleep structure is altered or diminished over time, resulting in long-term memory impairment, regardless of the kind of sleep disturbance. Therefore, neurologists or sleep clinics can use some objective neuropsychological tests to screen patients with sleep disturbances for potential risk of cognitive decline. Commonly used neuropsychological tests include the Wechsler Memory Scale, the Clinical Memory Scale, and some items in the memory subdomain, for example, delayed recall trials of the short-term verbal memory measures, Williams word memory test, etc.

Table 1.

Comparison of cognitive profiles of sleep deprivation, sleep duration, SDB, and insomnia from systematic reviews and meta-analyses

SBD Sleep-related breathing disorder, N/A not explored in the present papers. Effect sizes of d > 0.20 were considered small, d > 0.50 medium, d > 0.80 large and d > 1.00 very large. Shaded cells represent domains that were considered to demonstrate cognitive deficits. Mean effect size = Σd/n

In our overview, qualified meta-analyses on the cognitive impact of REM behavior disorder are lacking. The cognitive impairment produced by RBD is clearly present in a complete examination of dementia risk variables. In neurodegenerative disorders such Parkinson's disease, multiple system atrophy, and Lewy body dementia, RBD is frequently the first sign of an alpha-synuclein disorder [29]. Patients with RBD performed worse than patients without RBD in terms of overall cognitive function, long-term language memory, long-term language recognition, generation, inhibition, mobility, language, and visuospatial/construction ability in a meta-analysis of 6,695 PD individuals [48].

Some researchers have discovered that in individuals with long-term insomnia, the functional connection between the locus coeruleus and the noradrenergic system (LC-NE) in the prefrontal lobe is diminished [26], which is compatible with poor cognitive clinical performance. The function of the LC-NE system is influenced to some extent by locus coeruleus integrity and is associated with broad differences in cognitive domains, daytime sleep-related dysfunction, and risk of aMCI [20]. The prefrontal cortex is the LC-NE system's principal ascending projection, and it plays a role in attention and cognitive regulation [6, 66]. As a result, alterations in the LC-NE functional linkages in brain regions governing distinct cognitive domains could be the neuropathological process underlying cognitive impairment induced by persistent sleep disturbances.

Another notable flaw is that none of the systematic reviews examined the individuals' sleep medication history at baseline. A search revealed that few of clinical trials on sleep problems focused on medication for insomnia patients. Benzo diazoles (BZDs) and Z-class drugs (Zolpidem, Zopiclone, and Zaleplon) are commonly used in the treatment of insomnia, with side effects including cognitive impairment, drug tolerance, insomnia rebound after drug withdrawal, traffic accidents, drug abuse, and drug dependence [4]. Insomnia medication can cause cognitive and behavioral problems, including forgetting [71]. Therefore, an uninvestigated medication history was a residual factor impacting the results' accuracy. Future clinical trials should either exclude people on medication or add medication status as a covariate to adjust for this interference.

At the moment, the diagnosis and treatment of risk factors is the only way to prevent Alzheimer's disease. Sleep disorder as a modifiable risk factor induces cellular senescence by triggering activation of inflammatory responses, including telomere shortening, increased DNA damage response, and expression of the cell surface senescence signaling marker P16 (INK4a). The potential of cells to replicate is also a potential biomarker of human ageing. Moreover, even one night of partial sleep deprivation increased the activation of inflammatory markers [11, 32, 33]. Sleep is both a trigger and a symptom of dementia, implying that there is a bidirectional association between sleep disturbances and Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's disease causes degeneration of the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which disrupts the patient's circadian cycle, resulting in sleep disturbance in AD patients [67]. According to a meta-analysis of ten clinical studies published in 2020, abnormal sleep architecture, non-REM sleep, and REM pathological changes in MCI patients may all predict the trajectory of cognitive deterioration in the elderly, suggesting that modifying sleep EEG activity may slow cognitive decline and dementia in patients with MCI [17].

In conclusion, early detection and intervention of sleep disorders hold the potential to minimize the incidence of cognitive impairment and potentially delay the onset of Alzheimer's disease. Memory loss might be utilized as a cue for clinical evaluation. Further investigating whether sleep management delays the onset of dementia, especially in mild cognitive impairment and preclinical AD is of great importance.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

This study was funded by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81870850). The sponsor had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers' bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical approval

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Adams HH, et al. Genetic risk of neurodegenerative diseases is associated with mild cognitive impairment and conversion to dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(11):1277–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aloia SM, Arnedt TJ, Davis DJ, Riggs LRBD. Neuropsychological sequelae of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: a critical review. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(5):722–785. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704105134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson EL, et al. Is disrupted sleep a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease? evidence from a two-sample mendelian randomization analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(3):817–828. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkin T, Comai S, Gobbi G. Drugs for insomnia beyond benzodiazepines: pharmacology, clinical applications, and discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2018;70(2):197–245. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.014381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballesio A, Aquino M, Kyle SD, Ferlazzo F, Lombardo C. Executive functions in insomnia disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2019;10:101. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bari A, et al. Differential attentional control mechanisms by two distinct noradrenergic coeruleo-frontal cortical pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(46):1091–6490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2015635117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beebe DW, Groesz C, Wells LF, Wells A, Nichols CF, Nichols K, McGee AF, McGee K. The neuropsychological effects of obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis of norm-referenced and case-controlled data. Sleep. 2003;263:298–307. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bubu OM, et al. Sleep, Cognitive impairment, and alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. 2017;40:1. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bubu OM, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, cognition and Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review integrating three decades of multidisciplinary research. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;50:101250. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.101250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bucks RS, Olaithe M, Eastwood P. Neurocognitive function in obstructive sleep apnoea: a meta-review. Respirology. 2013;18(1):61–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carreras A, et al. Chronic sleep fragmentation induces endothelial dysfunction and structural vascular changes in mice. Sleep. 2014;37(11):1817–1824. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chattu VK, Manzar MD, Kumary S, Burman D, Spence DW, Pandi-Perumal SR. The global problem of insufficient sleep and its serious public health implications. Healthcare (Basel) 2018;7(1):1–16. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choshen-Hillel S, et al. Acute and chronic sleep deprivation in residents: cognition and stress biomarkers. Med Educ. 2021;55(2):174–184. doi: 10.1111/medu.14296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cross N, Lampit A, Pye J, Grunstein RR, Marshall N, Naismith SL. Is obstructive sleep apnoea related to neuropsychological function in healthy older adults? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2017;27(4):389–402. doi: 10.1007/s11065-017-9344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cross NE, et al. Structural brain correlates of obstructive sleep apnoea in older adults at risk for dementia. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(1):1800740. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00740-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Almondes KM, Costa MV, Malloy-Diniz LF, Diniz BS. Insomnia and risk of dementia in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;77:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Rozario AL, et al. Objective measurement of sleep in mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;52:101308. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffy SL, et al. Association of Anterior Cingulate Glutathione with Sleep Apnea in Older Adults At-Risk for Dementia. Sleep. 2016;39(4):899–906. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elfil M, Bahbah EI, Attia MM, Eldokmak M, Koo BB. Impact of Obstructive Sleep Apnea on Cognitive and Motor Functions in Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord. 2021;36(3):570–580. doi: 10.1002/mds.28412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elman JA, et al. MRI-assessed locus coeruleus integrity is heritable and associated with multiple cognitive domains, mild cognitive impairment, and daytime dysfunction. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(6):1017–1025. doi: 10.1002/alz.12261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emamian F, et al. The Association Between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Alzheimer's Disease: A Meta-Analysis Perspective. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:78. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan L, Xu W, Cai Y, Hu Y, Wu C. Sleep duration and the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(12):1480–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fortier-Brochu E, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, Ivers H, Morin CM. Insomnia and daytime cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(1):83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fulda S, Schulz H. Cognitive Dysfunction in Sleep-related Breathing Disorders: A Meta-analysis. Sleep research online SRO. 2003;5:19–51. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gabelle A, et al. Excessive sleepiness and longer nighttime in bed increase the risk of cognitive decline in frail elderly subjects: the mapt-sleep study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:312. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong L, et al. The abnormal functional connectivity in the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system associated with anxiety symptom in chronic insomnia disorder. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:678465. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.678465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt GH, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:1756–1833. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holth JA-O, et al. The sleep-wake cycle regulates brain interstitial fluid tau in mice and CSF tau in humans. Science. 2019;363:1095–9203. doi: 10.1126/science.aav2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howell MJ, Schenck CH. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and neurodegenerative disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(6):707–712. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huan T, et al. Interpretation of AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2018;18(1):101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Humer E, Pieh C, Brandmayr G. Metabolomics in Sleep, Insomnia and Sleep Apnea. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:19. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irwin MR, Opp MR. sleep health: reciprocal regulation of sleep and innate immunity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(1):129–155. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irwin MR, Vitiello MV. Implications of sleep disturbance and inflammation for Alzheimer's disease dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):296–306. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim J, Dinges DF. A meta-analysis of the impact of short-term sleep deprivation on cognitive variables. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(3):375–89. doi: 10.1037/a0018883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kien C, et al. GRADE guidelines: 9 Rating up the quality of evidence. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2013;107(3):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J, Gulati T, Ganguly K. Competing roles of slow oscillations and delta waves in memory consolidation versus forgetting. Cell. 2019;179(2):514–526. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klinzing JG, Niethard N, Born J. Mechanisms of systems memory consolidation during sleep. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(10):1598–1610. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0467-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koslowsky M, Babkoff H. Meta-analysis of the relationship between total sleep deprivation and performance. Chronobiol Int. 1992;9(2):132–136. doi: 10.3109/07420529209064524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langer G, Meerpohl JJ, Perleth M, Gartlehner G, Kaminski-Hartenthaler A, Schunemann H. GRADE guidelines: 1 Introduction - GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2012;106(5):357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leng Y, McEvoy CT, Allen IE, Yaffe K. Association of sleep-disordered breathing with cognitive function and risk of cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1237–1245. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leong RLF, Cheng GH, Chee MWL, Lo JC. The effects of sleep on prospective memory: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;47:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang Y, Qu LB, Liu H. Non-linear associations between sleep duration and the risks of mild cognitive impairment/dementia and cognitive decline: a dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(3):309–320. doi: 10.1007/s40520-018-1005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Livingston G, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Livingston G, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the lancet commission. The Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lo JC, Groeger JA, Cheng GH, Dijk DJ, Chee MW. Self-reported sleep duration and cognitive performance in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2016;17:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lowe CJ, Safati A, Hall PA. The neurocognitive consequences of sleep restriction: A meta-analytic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:586–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maggi G, Trojano L, Barone P, Santangelo G. Sleep disorders and cognitive dysfunctions in parkinson's disease: a meta-analytic study. Neuropsychol Rev. 2021;31(4):643–682. doi: 10.1007/s11065-020-09473-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mao J, et al. Association between rem sleep behavior disorder and cognitive dysfunctions in parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Neurol. 2020;11:577874. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.577874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neu D, Kajosch H, Peigneux P, Verbanck P, Linkowski P, Le Bon O. Cognitive impairment in fatigue and sleepiness associated conditions. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189(1):128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen-Michel VH, et al. Underperception of naps in older adults referred for a sleep assessment: an insomnia trait and a cognitive problem? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(10):2001–2007. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olaithe M, Bucks RS, Hillman DR, Eastwood PR. Cognitive deficits in obstructive sleep apnea: Insights from a meta-review and comparison with deficits observed in COPD, insomnia, and sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;38:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Philibert I. Sleep loss and performance in residents and nonphysicians: a meta-analytic examination. Sleep. 2005;28(11):0161–8105. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.11.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pilcher JJ, Huffcutt AI. Effects of sleep deprivation on performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 1996;19(4):0161–8105. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pillai JA, Leverenz JB. Sleep and neurodegeneration: a critical appraisal. Chest. 2017;151(6):1375–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pushpanathan ME, Loftus AM, Thomas MG, Gasson N, Bucks RS. The relationship between sleep and cognition in Parkinson's disease: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;26:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rasch B, Born J. About sleep's role in memory. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(2):681–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Samkoff SJ, Jacques HCM. A review of studies concerning effects of sleepdeprivation and fatigue on residents' performance. Jacques Acad Med. 1991;66:687–693. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199111000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014;146(5):1387–1394. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holger JS, Julian PH, Gunn EV, Paul G, Elie AA, Nicole S, Gordon HG. Chapter 14: Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence. 2021. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-14.

- 60.Sengupta A, Weljie AM. Metabolism of sleep and aging: Bridging the gap using metabolomics. Nutr Healthy Aging. 2019;5(3):167–184. doi: 10.3233/NHA-180043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shea BJ, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shi L, et al. Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;40:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Short MA, et al. Cognition and objectively measured sleep duration in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Health. 2018;4(3):292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith L, et al. Sleep problems and mild cognitive impairment among adults aged >/=50 years from low- and middle-income countries. Exp Gerontol. 2021;154:111513. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2021.111513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stranks EK, Crowe SF. The Cognitive Effects of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An Updated Meta-analysis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2016;31(2):186–193. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acv087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Szabadi E. Functional neuroanatomy of the central noradrenergic system. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(8):659–693. doi: 10.1177/0269881113490326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Van Erum J, Van Dam D, De Deyn PP. Sleep and Alzheimer's disease: A pivotal role for the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;40:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wallace A, Bucks RS. Memory and obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 2013;36(2):203–220. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang ML, et al. Cognitive effects of treating obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75(3):705–715. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wardle-Pinkston S, Slavish DC, Taylor DJ. Insomnia and cognitive performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;48:101205. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilt TJ, et al. pharmacologic treatment of insomnia disorder: an evidence report for a clinical practice guideline by the american college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):103–112. doi: 10.7326/M15-1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu L, Sun D, Tan Y. A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of sleep duration and the occurrence of cognitive disorders. Sleep Breath. 2018;22(3):805–814. doi: 10.1007/s11325-017-1527-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu WA-O, Tan CC, Zou JJ, Cao XP, Tan L. Sleep problems and risk of all-cause cognitive decline or dementia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(3):1468–2330. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2019-321896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu X, Zhao Y. Sleep-disordered breathing and the risk of cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of 19,940 participants. Sleep Breath. 2018;22(1):165–173. doi: 10.1007/s11325-017-1562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.