Abstract

Background:

There is a lack of research on autistic intimacy; however, a small body of research suggests that bondage, discipline, domination, submission, sadism and (sado)masochism (BDSM)/kink may be appealing to autistic people. We aimed at exploring how engagement in BDSM/kink related to autistic identity, using a phenomenological approach.

Methods:

We recruited six autistic adults through purposive sampling on social media. All participants took part in a one-to-one spoken interview about their engagement in BDSM/kink and how it related to their sense of identity.

Results:

We used interpretative phenomenological analysis to analyze the data and found three key themes. Theme 1, “Practicing safe ‘sex’” highlighted how the clear communication and explicit focus on consent present in BDSM/kink facilitated a feeling of safety. Theme 2, “So many ways to touch and be touched” was focused on the sensory draw of BDSM/kink, and how it provided exciting ways to explore sensory joy (and sometimes revulsion). Theme 3, “Subverting (neuro)normativity” showed how autistic people can find pleasure in intimate practices that transgress normative expectations.

Conclusion:

Our findings highlighted the importance of exploring the perceptions of autistic adults in relation to their own intimate practices. Autistic intimacy is an emerging area of research, with very little focus on lived experience. Although engagement in BDSM/kink may appear niche, our findings suggest that there are aspects which are inherently appealing to autistic people. These findings can be used to destigmatize both autistic intimacy and engagement in alternative intimate practices more broadly.

Keywords: autism, BDSM, kink, intimacy, neuroqueer

Community brief

Why is this an important issue?

Autistic intimacy is an under-explored area, with very little focus on the lived experiences of autistic adults and their preferences. Bondage, discipline, domination, submission, sadism and (sado)masochism (BDSM) and kink are alternative intimate practices. There are aspects of BDSM/kink that may appeal to autistic people (e.g., sensory experiences such being restrained during intimacy). However, to date, there is very little research to explore this.

What was the purpose of this study?

This study aimed at exploring the experiences and motivations of autistic people who engage in BDSM/kink from their own perspectives.

What did the researchers do?

We conducted online video interviews with six autistic adults. We purposefully recruited a small number of people, choosing to use a method called “interpretative phenomenological analysis” that emphasizes deep explorations of the experiences of a small number of people. This method is particularly suitable for areas where very little research exists.

What were the results of the study?

We found three key themes: Theme 1, “Practicing safe ‘sex’” highlighted how the clear communication and explicit focus on consent present in BDSM/kink facilitated a feeling of safety for our participants, who found uncertainty during intimacy stressful. The sense of safety fostered within these interactions also provided the participants with a space to be their authentic selves, and “switch off” from the outside world. Theme 2, “So many ways to touch and be touched” was focused on the sensory lure of BDSM/kink, and how it provided exciting ways to explore sensory joy (and sometimes revulsion) for autistic people. Theme 3, “Subverting (neuro)normativity” showed how autistic people can find pleasure in intimate practices that other people might find unusual.

What do these findings add to what was already known?

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore autistic engagement in BDSM/kink from a first-person perspective. Our findings show that some alternative ways of being intimate might attract autistic people, because they provide stability, pathways for sensory exploration, or because they are fun in ways that other people sometimes find unexpected.

What are potential weaknesses in the study?

We only interviewed a small number of people, and most of them shared similar interests within BDSM/kink. In future, it would be good to find out about the interests of a larger number of autistic people.

How will these findings help autistic adults now or in the future?

There is very little research exploring autistic intimacy from a validating perspective. Our findings will help to destigmatize autistic intimacy and normalize conversations about things that people might think of as “taboo.”

Introduction

Autism is a form of neurodivergence characterized by hyper/hypo-sensitive sensory perception,1,2 a monotropic (more singularly focused) attentional style,3 and a unique social communication style.4,5 Historical views on autism have framed autistic people as socially impaired and “mindblind”6 compared with the non-autistic population. Thus, autistic relationships, particularly those of an intimate nature, have gone relatively unexplored until more recently as viewpoints on autism and autistic people have started to shift away from deficit-focused conceptualizations.7 Researchers and the wider autistic community have highlighted the importance of research that addresses autistic sexuality and intimacy,8 inviting research that examines the unique features of autistic intimacy as one core focus.

Emerging research suggests that some autistic people may be likely to engage in alternative intimate practices, including bondage, discipline, domination, submission, sadism and (sado)masochism (BDSM hereafter) and/or kink.9–11 The aim of the current study is to explore autistic intimacy in BDSM/kink from a phenomenological perspective.

There is very little literature exploring BDSM/kink among autistic people from a sex-positive, non-deficit focused perspective.9 The exploration of alternative intimate practices such as BDSM/kink through an autistic lens offers the opportunity to break the “epistemic hamster wheel” (whereby autistic perceptions of our own sexualities become intertwined with deficit based perceptions of it)9 and gain insight into autistic intimacy in and of itself, as opposed to the positioned “other.” This approach sits in opposition to majority of extant research, which frames autistic intimate interest in BDSM and/or kink as “paraphilic” and “disordered.”12,13

BDSM and kink are umbrella terms that encompass a variety of practices, activities, and desires, including power exchange, physical restriction, the giving or receiving of pain/sensory stimulation, and roleplay.14–17 BDSM is often associated with a set of core principles, centered around clear communication of needs, boundaries, and desires.

These principles have been referred to previously as Safe, Sane, Consensual, however terminology has evolved over time to reflect changing attitudes toward what constitutes “safe,”18 and the ableist/saneist implications of the word “sane.”19 Hence, more recently, the terms “Risk Aware Consensual Kink” and “Personal Responsibility, Informed Consensual Kink” have become more widely used.20 Despite the changes in terminology, the foundational ideas of BDSM have remained the same.

Practitioners emphasize being aware of the potential health and safety risks of different types of play (e.g., if one chooses to engage in rope bondage, are they aware of potential risks and how to respond if there is a problem). In addition, the clear communication of needs, wants, and boundaries (i.e., activities that are off limits) is expected and encouraged both before and during play (known as negotiation). Both verbal (e.g., safewords such as red), and non-verbal (e.g., having an item to jingle, or drop) forms of communication can be used to signal discomfort to a partner (or the desire for an increase in intensity), and the desire to stop/continue play.

Finally, enthusiastic and active consent is a cornerstone of healthy BDSM play (even when the appearance of non-consent or coerced consent has been negotiated at the outset), and a practitioner may revoke their consent at any time without having to give a reason.

Recent evidence from the individual research streams (autism research, and BDSM/kink research) may provide insight into the possible ways in which autistic characteristics and BDSM/kink practices may complement each other. BDSM and kink practitioners commonly report engaging in behaviors that provide sensory stimulation, such as temperature play and impact play (e.g., spanking).

A recent study from Gray et al.10 explored sensory features of sexuality and relationships among autistic people, finding a unique impact that could be both positive (e.g., increasing sensitivity to touch) and negative (e.g., auditory distress making it hard to enjoy intimacy). Positive aspects of sensory experience can promote emotional regulation and catharsis, resulting in a sense of calm and relief.21,22

Interestingly, qualitative studies with autistic people have shown that “stimming” (i.e., self-stimulatory behaviors such as finger tapping, hand flapping, and leg bouncing) elicits similar outcomes regarding emotional regulation and release.23,24 BDSM practitioners often report that participating in physical bondage (e.g., using rope to restrict movement) can elicit a sense of safety and calmness in those who are bound.25

This parallels autistic people's use of therapeutic tools, such as weighted blankets, to reduce anxiety and promote calmness.26 Finally, BDSM practice is typically characterized by constancy, requiring specific set-ups, clear communication, and considerable planning, resulting in a ritualistic experience for the participants. These aspects of BDSM parallel, and likely appeal to, many autistic peoples' desire for routine and predictability.27

To practice BDSM with constancy, a period of in-depth learning is often required for participants to learn sufficient detail regarding the specific practices they may wish to engage in (for a review see Simula).28 Researchers have suggested that for some autistic people, sex (and/or BDSM) may serve as a focused passion or interest.9 Thus there are many sources of overlap between factors from which autistic people commonly derive joy, and aspects of BDSM and kink.

In addition to the potential appeal in the sensory and practical aspects, autistic people may be attracted to the inherently transgressive nature of BDSM and kink. Recent advances in theoretical conceptualizations of autism as a form of neurodivergence have also explored autistic modes of embodiment as a form of “neuroqueering.”29

Walker posits that autistic people are liberated by emancipating themselves from normative and essentialist expectations of gender and sexuality (cis and heteronormative expectations), and the demand to perform neurotypical social behavior (neuronormativity). This emancipation provides space for autistic people to flourish through deriving joy in ways that challenge societal expectations.29

Likewise, exploring queer forms of intimacy (such as BDSM/kink) eschews and rejects expectations of what “normative” human sexuality is meant to look like30 and allows for the exploration of alternative forms of pleasure. Bertilsdotter Rosqvist and Jackson-Perry9 call for qualitative research that rejects deficit narratives of autistic sociality/sexuality and does not bring preconceived notions of what constitutes autistic sex and intimacy.

Thus, the aim of this study was to conduct a qualitative exploration of experiences of BDSM and kink among autistic adults, focusing on how these experiences relate to autistic identity.

Methods

Research question

The aim of this study was to explore the motivations and experiences of autistic adults who engage in BDSM/kink and how their sexuality (inclusive of asexuality) relates to their autistic identity. Our research questions were:

(a) What are the experiences of autistic adults who engage in BDSM/kink?

(b) How do autistic adults describe their engagement in BDSM/kink as it relates to their autistic identity?

Methodological approach

This study was ideographic in nature and drew upon a critical realist perspective and feminist standpoint theory.31 Our interpretations were grounded in the assumption that although all autistic people have unique experiences of the world, they will also have shared experiences, based not only on a shared/similar neurotype but also on how the outside world views autistic people.32,33 We chose to use interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) as our analytic framework due to the suitability of IPA toward exploring how people make sense of their own experiences,34 and its alignment with a critical realist perspective.

The IPA uses the double hermeneutic, an interactive process by which both researcher and participant make meaning of the participants' experiences,35 with the researcher considering both explicit (what is said) and latent (what is socially constructed/influenced) content of the conversation in their analysis.

We used semi-structured interviews (Supplementary Data S1) with a set of questions designed to guide the conversation, with space for the interview to flow in the direction that the participant led with their responses. All interviews were conducted by A.P. and analyzed by both authors. Both authors are autistic and have situated experience of the research topic.

Although a shared neurotype between researcher and participant is not necessary for IPA, autism research has a history of epistemic injustice,6 by which the experiences of autistic people are interpreted through a neuronormative lens.36 It was important to the authors that this study did not perpetuate harmful stereotypes about autistic desire (e.g., labeling intimate interests as paraphilic), objectify autistic people, or stigmatize people who engage in BDSM/kink (neurodivergent or otherwise).

Participants

We recruited six adults between the ages of 27 and 52 (Table 1) through purposive sampling using a social media post shared on Twitter. We initially sought to interview between 5 and 10 people; 16 people responded to our original advert, and 6 of these contacted us to arrange an interview. Our small sample size was determined by our approach; IPA is not appropriate for use with larger samples due to the in-depth nature of the approach and as it does not aim at generating theory but at exploring a particular phenomenon.35

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Pseudonym

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender (self-described) | Sexual orientation (self-described) | Race/ethnicity (self-described) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alee | 32 | Female | Bi/pansexual | Tornio |

| Noel | 52 | Male | Heterosexual | White |

| Alice | 45 | Unsure | Unsure | White |

| Bucky | 27 | Non-binary | Queer | White British-Black Caribbean |

| Autumn | 29 | Non-binary | Gynosexual | White |

| Quin | 33 | Non-binary | Queer | White |

Inclusion criteria specified that we were looking for autistic adults (18+) who engage in BDSM/kink. Both clinically diagnosed and self-identified autistic participants were welcome, as the researchers acknowledge (a) biases present in the diagnostic process that can make it difficult for one to seek and attain a diagnosis37,38 and (b) that not all autistic people feel the need to have a clinician confirm their neurotype.

Procedure

In accordance with the AASPIRE39 guidelines for research involving autistic people as participants and researchers, we offered participants the opportunity to take part in interviews using multiple formats (i.e., live video interview, asynchronous written interview). All six participants chose to give spoken interviews. Interviews took place on Zoom or Microsoft Teams at a time suitable to the participant. The interviewer read the information sheet with the participant (which had been sent to the participant before the interview) and confirmed consent.

They proceeded with the interview after confirming that the participant was happy to be recorded, starting with demographic questions before moving on to the interview questions. The semi structured nature of the interview meant that the dialogue was able to flow in the direction that the conversation naturally progressed while covering key questions. Each interview lasted between 37 and 75 minutes (mean length = 52 minutes). After the interviews were complete, the authors transcribed the recording (taking three each and double checking for accuracy) and deleted the recordings.

Ethical considerations

This study received ethical approval from the University of Sunderland Research Ethics Committee (No. 004827). All participants are referred to using a pseudonym throughout this manuscript to protect their anonymity and were given the option to choose this name or have the researcher assign one to them. Three chose their own pseudonym, and the remaining three asked the researcher to assign one.

Analysis

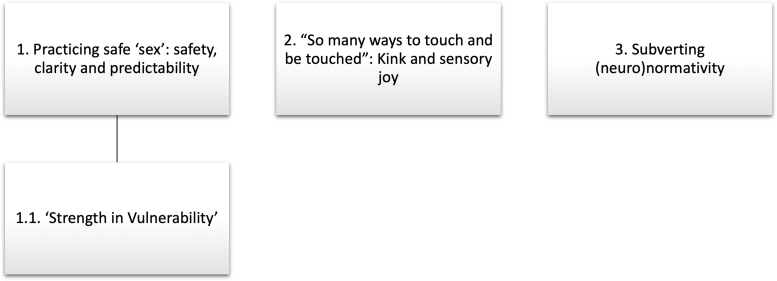

We analyzed the data following established guidelines on conducting IPA.35 Each author coded all six transcripts independently. We started by reading through the transcripts and making notes, then met to discuss our initial thoughts. Next, we started to transform our notes into emergent themes for each participant, meeting again to discuss our findings so far and our interpretations. Finally, we started developing emergent themes into clustered themes based on shared connections across participants. We met once more to finalize our themes, sharing our clustered themes with each other and refining these until we reached the final set, common to all participants (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Final superordinate and sub-themes developed during the analytic phase.

Both authors found the research process validating, providing space to explore their own thoughts on the topic and how their experiences related to those of the participants. The first author also found it incredibly rewarding to experience participants making sense of their own stories during the interview and gaining further self-knowledge from the discussion.

Results

Our final themes comprised three superordinate themes (Fig. 1), with only theme 1 containing a sub-theme. These themes captured the nature of BDSM/kink as providing our participants predictability and safety, a world of sensation, and a space to find joy in the unexpected. We discuss each in turn.

Theme 1: practicing safe “sex”: safety, clarity, and predictability

Among our participants, there was a general sense that the structure, negotiation, and communication present within BDSM/kink reduced uncertainty and made them feel safer. The explicit negotiation involved removed anxiety around intimacy through the implicit structure present, and it provided participants with the opportunity to ensure that they and their partner had shared values across multiple levels:

“It's more structured. It feels safer…I do get anxiety over sexual situations I suppose, but less so with kink, I think because it has that skeleton structure holding it up… ‘It means I've gone through all the sexy negotiation bits, and I do know where these people stand on like things that are integral to my personhood, you know? Like race and transphobia, and all that…It's comforting, reassuring, and hot’” (Bucky).

Establishment of shared values can be essential for autistic people (and particularly those with multiple marginalized identities like Bucky who is autistic, queer, non-binary and of mixed-race) in avoiding both fetishization (e.g., being pursued because of a particular characteristic) and dehumanization. Likewise, Quin recounted experiencing gender invalidation in their first experience that led them to think about their future boundaries:

“I don't think I knew what I wanted. But at least with that person and that experience now, I do know…it was only after we did the do that I found out that this person wanted someone who, in his own almost verbatim words, uses exclusively she/her pronouns.”

Developing negotiation skills also provided the opportunity for participants to be upfront in their communication and create a more effective and open dialogue with partners outside of kink. Alee spoke about how her current partner is not interested in BDSM/kink, but she has implemented explicit and active communication with him and taught him how to do the same.

Here, the “communication styles” of kink and BDSM, and autistic people are well aligned (directness, being explicit), which can also help non-autistic (and non-kinky people) to learn how to communicate about their own boundaries more explicitly and openly. However, it is important to note that prior experiences of being direct had not always been welcomed and had led to anxiety around communication of needs being met with rejection. Thus, for some participants, the ability to communicate in a more “autistic” way meant using non-verbal signifiers that minimized the risk of either partner being dissatisfied, or of miscommunication occurring, while providing the space to have needs met:

“It's gonna be like the most autistic thing you ever heard. Um, so you know how toothbrushing is a thing in autism… So my husband has an issue where he will not brush his teeth….But he also knows that like, I got my boundaries, like, dude, you gotta brush your teeth, you gotta shower. So when we want to have sex, either one of us, we often send each other tooth brushing gifs. And that is asking for sex. Because you know, we're both afraid of like (asking), we're both familiar with what it is to not have our needs met.” (Alice).

Using text messages and emojis facilitated open communication and reduced stress, leading to an increased sense of safety and intimacy. Alice and her husband had found a way of communicating that worked for them, and felt comfortable, helping them both to move past prior invalidating experiences. One important and unexpected factor raised by participants was how developing these communication skills and advocating for themselves during intimate negotiations also came from engaging with sex work (as a client or worker):

“I should read their website first. And you know, I should .. I should be clear about A, B, and C…there are a lot of people who do needle play, and there's a lot of people with electric play and very serious CBT [cock and ball torture]. And like, there are things that it if, if you say, ‘I don't have any limits,’ there are things that it would be reasonable to experience in a session that you probably don't want to” (Autumn)

The explicit nature of these interactions meant that clarity was present from the start that facilitated confidence in both self-advocacy and the ability to use a more direct communication style. These interactions also allowed participants to feel that they were able to be themselves, without worrying about the “maintenance” of the relationship outside of that specific context. Alice spoke about the ease of developing a friendship with a sex worker that she and her husband would sometimes see because the explicit rules of the interaction minimized a need for masking (the suppression of aspects of self to minimize recognition of autistic characteristics).40,41

“I can fake all day at work and I can mask all day at work and I can be fine right but like, interpersonal friendship is just exhausting for me…autistic people need connection too… it's just different. And, I, I wish people understood that part that it's… I just have a threshold and it's different for what I can tolerate and how I connect. So that's why we went that route [seeing a sex worker]” (Alice)

Safety and predictability were also achieved through sexual scripting in the way that participants approached or mapped out interactions with partners. Sometimes, this was following an explicit “plan of action,” as described by Noel:

“Knowing what to expect, having a structure as to what what's going to happen…it always starts off with us shutting the curtains, and we've got an LED light…Diana will go off and get dressed, and then just the tactile stuff feeling working my way up and then just we go forward.”

However, scripting was not always about following the exact same pattern of actions, but about knowing what was possible. For example, both Bucky and Alice mentioned that there might be unexpected occurrences within an encounter, but that these would always be from a menu of consensual and pre-agreed items. This meant that participants were able to be spontaneous during intimacy while still having some certainty about the remit of what might occur, which meant that they knew whatever happened was going to be enjoyable for them and their partner.

Strength in vulnerability

The sense of safety present in kink-based intimacy also allowed participants to be vulnerable with their partners, and “let go,” which was difficult to achieve without some external prompting.

“I like being pushed mentally down…It gives me a type of mental peace that I struggle to find elsewhere. I would assume other people reach it by meditating, I've never managed but it's really knowing that for one, I'm safe. Someone else got me.” (Alee)

The sense of always feeling “switched on,” engaging in constant self-reflection or thinking about external responsibilities was “switched off” through kink, forcing participants to be “in their body.” Some of the participants had thought about this explicitly and knew that kink was a way to achieve this mental state, as Bucky described:

“My brain is constantly running like 6 threads at the time. And it's just so hard to get out of it like, even when I rest, I'm not resting because I'm thinking. And outside of kink really, the only other time that happens is if I'm engaged in a special interest, or if I'm asleep… I'm not able to do that (think) when I'm really rooted in my body.”

For others, the realization came during the discussion, as Autumn reflected: “So I actually hadn't thought of that kind of experience in the context of BDSM before but reflecting now I do think that I am usually taken out of myself in that process.”

These experiences were also related to masking, with kink (and particularly power exchange) providing a place to unmask, and give up control:

“It's surrendering responsibility. You spent so much time being responsible, managing, acting, having to mask having to…it's like or so almost in your head having…a version of you that's looking back at you, that you're always self analyzing. You live in such a strict, controlled way…That to just not have any power, to not have any control is, it's. It's here as well [gestures to head]” (Noel)

Being “forced” to unmask in a safe environment provided a place to truly relax and “let go,” with the inbuilt reassurance led to catharsis and a sense of bodily relaxation that could be otherwise difficult to achieve. Here, participants could express authenticity and be accepted for who they were at their most vulnerable, as described by Alice as “there's a vulnerability and it's really, it can be really raw really raw vulnerability” (Alice).

The ability to be vulnerable also provided the opportunity to learn about boundaries and self-advocacy in a way that carried over into other aspects of life (as highlighted in the superordinate theme). All of the participants mentioned traumatic experiences during their interviews (not necessarily centered around intimacy), and their comments suggested that kink/BDSM had provided a way to navigate trauma, for example, Alice spoke about using BDSM as a way to “practice boundaries in a way that carries over into action,” and Autumn spoke about certain aspects of BDSM allowing them to “process trauma in a friendly environment.” Overall, kink and BDSM seemed to provide a framework that inherently supported the communicative and cognitive needs of the participants, providing a sense of certainty, safety, and openness.

Theme 2: “so many ways to touch and be touched”: kink and sensory joy

There was a strong element of sensorium present within the motivation to engage in kink. Autistic sensory processing often includes aspects of hyper (over-stimulating) and hypo (under-stimulating) sensitivity. Although this can be distressing and overwhelming when it occurs through unpredictable means,1,2 the ability to play with sensory experience can also be incredibly pleasurable, as captured by the concept of “sensory joy” within the autistic community.42 Bucky described navigating this dichotomy:

“You know when you're playing explicitly with like sensory play, that autistic dislikes or wants, you know, somewhere along the lines…that's gonna trip something cause I think there are so many ways to touch and be touched by someone…like in the past I've been asked like do you want to do temperature play? And I was like no [laughs]. That sounds like the worst idea I've ever heard. Absolutely not.”

Sensation is a key aspect of kink and BDSM that may provide appeal to broaden the experience of sensory joy, beyond avoidance of sensory repulsion. Sensory exploration is present in physical stimulation (e.g., temperature play, as mentioned by Bucky). Participants highlighted sensory seeking as an attractive aspect of BDSM, through physical stimulation: “I had a violet wand [electrical toy] on my arm. Just to try that. And I remember liking that” (Quin), and through specific paraphernalia such as clothing or restraints: “I love, I guess like fetishwear and stuff like that, all that sort of stuff. It's probably sensory, the smell, the feel, that sort of stuff.”

Noel also described the physical sensations derived from kink: “Creating mentally a warm sensation [gestures to head]…Like electric flowing through your body, it's a sensory thing, it's, it's, it's beyond.” (Noel). For him, engaging in power exchange went beyond the physical sensation of touch, and it led to a more wholly embodied experience felt throughout the body and mind (being “cerebral rather than physical”).

Engagement with kink seemed to provide an opportunity to embed embodied sensory practice as pleasure, encouraging awareness of the position and function of the body. Alee described drawing upon her work with other disabled adults to use rope in a therapeutic manner: “…like showing you where your body is… so we do a lot of like, here are your fingers…Like that type of thing I bring in with me when I rope top.” The integration of knowledge about disabled embodied experience into intimate practices helped to create an experience tailored to be pleasurable to the individual.

Theme 3: subverting (neuro)normativity

The experience of not feeling part of the “dominant” social group attracted the participants toward the BDSM/kink subculture. Noel described being drawn to the gothic subculture and clothing as a teen: “I guess the alternative scene always interested me growing up…I never connected to the mainstream people.” (Noel). There was a sense among the participants of always being on the margins, or standing out from others even when it was not intentional.

BDSM/kink spaces were described as more accepting of difference as described by Alee: “I feel like I will be accepted, even if I'm stimming.” However, this was not universal, as Quin described how some spaces that appear to be open and accepting are “are actually quite conservative.”

There was a deep sense among participants that their engagement with both kink and the wider world was an inherently transgressive action that eschews normative expectations of autistic people by virtue of their existence: “autistic people by proxy of living in this world, we subvert a lot of things because these things are rules, and we don't see the point of them” (Bucky). The discussion with Bucky highlighted how the engagement in kink, and engagement in other non-normative activities were treated as analogous within the wider discourse around autistic interests:

“We are taught to endure as autistic people, and again, I think it's something about naming the unknown. It's empowering in the way that in naming something you assume the power of it, and then you can choose what to do with it…there are a lot of things [as autistic people] we have to endure and I think the flip side and the unspoken side of that is that our pleasure isn't equivocal? I think we get that lesson a lot, that like, the things that we take joy in aren't enough or equivalent to neurotypical joy. And that's why you get people being shamed over like special interests and their hobbies”

The experience of deriving joy from the “atypical” here subverts expectations of both what is pleasurable, and what is “normal” for the participant. Bucky indicates that autistic people can take this concept and play with it, queering expectations and finding joy in unexpected places (e.g., the sensation of pain).

The subversive nature of kink meant that participants could explore aspects of themselves outside of normative expectations of what being an adult looks like. Quin described how age play (e.g., engaging in activities associated with younger people, or roleplaying as a younger person) provided a form of escapism and identity exploration:

“I would think about what it would be like to be a baby again. Yeah. But in a completely innocent sense, like, Oh, I wish I didn't have to do all this. I wish I didn't have to be so grown up all the time. Yeah. And, of course, and it sounds odd. I've only ever seen this expressed elsewhere once, but I sometimes I think of that little space, potentially as a sort of drag.”

The space to explore different aspects of identity is similar to that seen in the literature focusing on adult play.43 Though some forms of identity exploration may be viewed as more “transgressive” due to the nature of the identity being explored, the ability to “play” with conceptualizations of self also allows us to unpack our experiences and thoughts about them through a different lens, as Quin recounted, “I don't think of I don't think of it in terms of strict age. Because I went to special education…Sometimes it might be stuff like watching cartoons, might be colouring in.”

Here, Quin explores the notion of “mental age” and the perception that our chronological age and “mental age” are not always consistent. Though the concept of mental age is considered ableist,44 Quin queers this concept through exploring a mentally, and physically younger self in a way that empowers them and provides a sense of escapism, as opposed to the concept being used by an outsider to form (usually negative) perceptions of their capabilities.

This again relates to Bucky's point that autistic interests are not considered equivocal, and engaging in sensorily-stimulating activities such as playing with beads is often infantilized and considered “inappropriate” for an adult.

Despite the notion that autistic people were by virtue of their existence queering expectations, there was also a sense that autistic sexuality (and disabled sexuality more broadly) should not be viewed as surprising. Both Quin and Alee expressed objection with people treating disabled intimacy as “edgy,” with Alee drawing upon a local disability justice slogan to emphasize: “We have a slogan here that a lot of wheelchair users use that would be ‘Gå eller rulla—Alla vill knulla’ which means ‘walking or wheeling, everyone just wants to fuck’” (Alee).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to explore the BDSM and/or kink experiences of autistic adults, with a particular focus on how they related these experiences to their autistic identity. Although research investigating the intersection of BDSM, kink, and autism is sparse, studies to date have highlighted a number of ways that BDSM and/or kink may appeal to autistic people.1,9 Although this was evident in the current study, our data also revealed a strong relationship between the identities of our participants, and their BDSM/kink experiences. Three key themes emerged from the present study, centered on finding comfort and safety in predictability, sensory joy, and subverting (neuro)normativity.

Comfort and safety in predictability

Across participants, we found a sense of safety present in kink and BDSM. This sense of safety was related definitively to both expectation of explicit negotiation and a clear communication style, and the resulting predictability that acted as a foundation for allowing the participants to experience true vulnerability. For autistic people, navigating the world is often fraught with uncertainty, whether in the form of unpredictable sensory stimuli,1 or social responses from conspecifics.

Autistic people often experience misinterpretation during social interaction due to the double empathy problem4 whereby mutual misunderstandings arise between autistic and non-autistic interlocutors through the misalignment of communication styles. Historical deficit accounts of autistic social skills have framed autistic communication as impaired, rather than acknowledging that any breakdowns in interaction between autistic and non-autistic people are bi-directional, with each participant drawing upon their own unique contextual understandings.

These accounts pervade the public understanding of autistic social skills, which can result in heightened anxiety for autistic people around being perceived as an “instigator” of any communicative breakdowns. The anxiety around social interaction and experience of stigma can also lead autistic people to engage in “masking”40 and concealment45 of identity. Masking is exhausting for autistic people46 and requires a high degree of self-monitoring and cognitive control,40,47 and engagement in BDSM/kink appeared to provide catharsis from the need to feel “in control.”

All the participants also highlighted how BDSM/kink had helped them to deal with previous trauma. It is important to note here that this navigation did not necessarily come from re-enacting trauma in a controlled environment (see Thomas)48 but from the skills developed through wider engagement, such as boundary setting, self-advocacy, and being treated in response with respect and care from partners (which fostered a sense of safety and the ability to be vulnerable and open).

Sensory joy

Several participants discussed how participating in BDSM and/or kink had provided them with opportunities to have their sensory needs fulfilled, and experience sensory joy, but also meant risking sensory distress or repulsion. The embodied experience of being autistic diverges from that of neurotypicality, with a high percentage of autistic people experiencing sensorimotor differences49,50 including in interoceptive (internal sense, e.g., hunger, thirst) and proprioceptive (sense of where your body is in space) processing.

For some participants, BDSM/kink provided a unique opportunity to explore their sensory preferences via physical sensations (e.g., touch, pain) and engage with specific textures (e.g., of fabrics of clothing and props) to foster sensory joy and avoid displeasure. Indeed, at least one participant stated that the potential for sensory joy was a large part of their initial attraction toward experimenting with BDSM/kink.

Moreover, due in part to the clear communication/predictability already mentioned, for some participants BDSM/kink provided them with the chance to experiment and play with new sensations in a predictable and controllable manner. The sensory aspect of BDSM/kink appeared to be a strong factor in attracting our interviewees in the first instance, with formative experiences centering around an attraction to new sensations.

Subverting (neuro)normativity

Recent work has positioned autistic people as a minority,29,51 whose ways of navigating, and existing in a society framed around the needs of the dominant group are pathologized. Across most of our participants, there was an acknowledgment of BDSM and kink was generally considered subversive; that is, regardless of identity, an individual engaging in BDSM/kink is subverting what is commonly deemed “acceptable” with regards to sexual behavior and sexual satisfaction.

The BDSM/kink community appeared to be more welcoming for some of our participants, though this was not universal. These findings are consistent with previous work in BDSM/kink communities,30,52 showing that although no singular kink community exists, many kink spaces provide validation and acceptance for those considered to exist on the margins of society.

In addition, our participants also acknowledged that their engagement in BDSM/kink as an autistic person is subversive of the normative expectations of autistic people. The participants discussed in depth the ways in which their BDSM/kink engagement as autistic people subverts (neuro)normative expectations at two levels: (a) the experience of pleasure in response to stimuli typically considered to be aversive (e.g., pain), and (b) the experience of sexuality and sexual pleasure as an autistic person.

Discussion of autistic interests is often framed in a pathological manner, either relating to the intensity of the focus (e.g., framing autistic interests as “special interests”)53 or the focus itself (e.g., being “niche” or “circumscribed”).54 Participants' comments were consistent with Bertilsdotter Rosqvist and Jackson-Perry,9 whereby autistic desires are often framed as inherently pathological through virtue of being attached to an autistic person.

The findings centered in “queering” of expectations supports Walker's work on neuroqueering29 as a practice for autistic emancipation and flourishing. This approach was apparent in Quins commentary on their engagement in age play, and how it related to attending specialist educational provision, where students were labeled “developmentally behind.”

Indeed, Pyne55 outlines how joy in autistic childhood, particularly when spent in “special education,” is quashed in favor of “behavioural intervention” and “functional skills.” Quin inferred that “playing” with age served a dual purpose: to immerse themselves in typically “childlike” activities (e.g., coloring books, watching cartoons) for pure sensory joy, but that also they saw the idea of “age appropriate” as pointless, because of previous experiences with ableist assertions that their intellectual ability and chronological age were inconsistent on account of their autistic identity.

Taking perceptions of what is “developmentally appropriate” for an adult or child, and subverting it, relates to Hammacks30 argument that kink involves acknowledging the performativity of social roles (e.g., what a disabled adult should desire), and a reframing of injustice (ableist and infantilizing perceptions). In this instance, BDSM created a space for participants to take typically negative, ableist perceptions and expectations of autistic people and subvert them in a way that provides joy, catharsis, and escape.

Alongside the view of autistic engagement in BDSM and kink as subversive of (neuro)normative expectations, our participants also frequently noted that autistic sexuality should not be viewed as something extraordinary. Participants were aware of this apparent dichotomy in their thinking, and discussed how this highlighted the need for acceptance of their apparent “otherness” as autistic people as an empowering action, while forcing neuronormative expectations onto autistic sexuality resulted in objectification and negative experiences.

This dichotomy between subversion and being “nothing out of the ordinary” echoes the findings of Bertilsdotter Rosqvist and Jackson-Perry.9 However, in the current study, it appears that the participants were unpacking these notions, aware of the dichotomous nature. There was an awareness that being autistic resulted in being marked as “other,” and that accepting this otherness and subverting normative expectations was empowering, but that trying to understand these desires through a neuronormative lens was needlessly objectifying.

These acknowledgments suggest that it is possible to break the epistemic hamster wheel highlighted by Bertilsdotter Rosqvist and Jackson-Perry9 if we respect the experiences of autistic people and explore them with nuance.

This is a valuable insight concerning the depth to which BDSM/kink engagement relates to our autistic participants identities as autistic people; their engagement in a non-normative activity, like BDSM and/or kink, is not just a personally empowering experience, but something that can drive autistic emancipation more widely.

Limitations

Though our participants had a range of interests within BDSM/kink, most preferred to take either a submissive or switching role within their relationships, and no-one described themselves as primarily dominant. Though samples in IPA tend to be purposefully homogenous, kink is also notoriously broad, and there are many aspects of kink/BDSM engagement that may attract autistic people that we do not capture within our sample. Future research should explore a wider range of BDSM/kink activities and orientations to gain more insight into aspects that may interact with autistic identity.

Our participants had varying levels of experience with “in person” play, and this did appear to impact their reflections, with those who had more experience reflecting more depthfully on their preferences and experiences. However, this finding supported broader commentary of kink as a facilitator of self-discovery and self-advocacy, whereby “learning by experience” created a bank of knowledge that could be applied within and outside of kink.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore autistic engagement in BDSM/kink from an emancipatory perspective. We found that the explicit communication style present in kink spaces fostered a sense of safety for autistic adults that made intimacy more accessible. Kink also provided the potential for sensory exploration, inclusive of both positive and negative aspects that needed to be carefully navigated.

Finally, engagement in kink related to a broader sense of neuroqueering normative expectations about pleasure and intimacy. Our findings mirror the broader literature on BDSM/kink,30 and they illuminate the ways in which reconsideration of normative structures of intimacy can foster a more in-depth understanding of autistic flourishing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the people who kindly gave their time to take part in this research.

Data Availability

The data for this project are not available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

A.P.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation.

S.H.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The authors did not receive any funding for this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Kirby AV, Bilder DA, Wiggins LD, et al. Sensory features in autism: Findings from a large population-based surveillance system. Autism Res. 2022;15(4):751–760. 10.1002/aur.2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacLennan K, O'Brien S, Tavassoli T. In our own words: The complex sensory experiences of autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022;52(7):3061–3075. 10.1007/s10803-021-05186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murray D, Lesser M, Lawson W. Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism. Autism. 2005;9(2):139–156. 10.1177/1362361305051398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Milton DEM. On the ontological status of autism: the ‘double empathy problem.’ Disabil Soc. 2012;27(6):883–887. 10.1080/09687599.2012.710008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mitchell P, Sheppard E, Cassidy S. Autism and the double empathy problem: Implications for development and mental health. Br J Dev Psychol. 2021;39(1):1–18. 10.1111/bjdp.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Botha M. Academic, activist, or advocate? Angry, entangled, and emerging: A critical reflection on autism knowledge production. Front Psychol. 2021;12:727542. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.727542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bertilsdotter Rosqvist H. Becoming an ‘Autistic Couple’: Narratives of sexuality and couplehood within the swedish autistic self-advocacy movement. Sex Disabil. 2014;32(3):351–363. 10.1007/s11195-013-9336-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dewinter J, van der Miesen AIR, Holmes LG. INSAR Special Interest Group Report: Stakeholder perspectives on priorities for future research on autism, sexuality, and intimate relationships. Autism Res. 2020;13(8):1248–1257. 10.1002/aur.2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bertilsdotter Rosqvist H, Jackson-Perry D. Not doing it properly? (Re)producing and resisting knowledge through narratives of autistic sexualities. Sex Disabil. 2021;39(2):327–344. 10.1007/s11195-020-09624-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gray S, Kirby AV, Graham Holmes L. Autistic narratives of sensory features, sexuality, and relationships. Autism Adulthood. 2021;3(3):238–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pliskin AE. Autism, Sexuality, and BDSM. Ought: J Aut Cul. 2022;4(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schöttle D, Briken P, Tüscher O, Turner D. Sexuality in autism: Hypersexual and paraphilic behavior in women and men with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19(4):381–393. 10.31887/dcns.2017.19.4/dschoettle. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kellaher DC. Sexual behavior and autism spectrum disorders: An update and discussion. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(4):562. 10.1007/s11920-015-0562-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. De Neef N, Coppens V, Huys W, Morrens M. Bondage-discipline, dominance-submission and sadomasochism (BDSM) from an integrative biopsychosocial perspective: A systematic review. Sex Med. 2019;7(2):129–144. 10.1016/j.esxm.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wignall L, McCormack M. An exploratory study of a new kink activity: “Pup Play.” Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46(3):801–811. 10.1007/s10508-015-0636-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Newmahr S. Rethinking kink: Sadomasochism as serious leisure. Qual Sociol. 2010;33(3):313–331. 10.1007/s11133-010-9158-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vivid J, Lev E, Sprott R. The structure of kink identity: Four key themes within a world of complexity. J Posit Sex. 2020;6:75–85. 10.51681/1.623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lupine E. 5 types of BDSM play people don't realise are dangerous. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QkubpzH4t04 Accessed October 7, 2022.

- 19. Peschek M. Safe, Sane and Consensual (SSC) vs. Risk Aware Consensual Kink (RACK). In: A Kinky Autistic. 2019. https://akinkyautistic.com/2019/05/15/safe-sane-and-consensual-versus-risk-aware-consensual-kink/ Accessed October 7, 2022.

- 20. Epochryphal. RACK vs SSC—Kink, Consent, Ableism, Agency. Published 2015. https://epochryphal.wordpress.com/2015/02/16/rack-vs-ssc-kink-consent-ableism-agency/comment-page-1/ Accessed October 7, 2022.

- 21. Lindemann D. BDSM as therapy? Sexualities. 2011;14(2):151–172. 10.1177/1363460711399038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ambler JK, Lee EM, Klement KR, et al. Consensual BDSM facilitates role-specific altered states of consciousness: A preliminary study. Psychol Conscious Theory Res Pract. 2017;4:75–91. 10.1037/cns0000097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCormack L, Wong SW, Campbell LE. “If I don't Do It, I'm Out of Rhythm and I Can't Focus As Well”: Positive and negative adult interpretations of therapies aimed at “Fixing” their restricted and repetitive behaviours in childhood. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022. [Epub ahead of print]; 10.1007/s10803-022-05644-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24. Kapp SK, Steward R, Crane L, et al. ‘People should be allowed to do what they like’: Autistic adults' views and experiences of stimming. Autism. 2019;23(7):1782–1792. 10.1177/1362361319829628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zambelli L. Subcultures, narratives and identification: An empirical study of BDSM (bondage, domination and submission, discipline, sadism and masochism) practices in Italy. Sex Cult. 2017;21(2):471–492. 10.1007/s12119-016-9400-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Green L, Willis E, Ziev N, Oliveira D, Kornblau B, Robertson S. The impact of weighted blankets on the sleep and sensory experiences of autistic adults. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74(4 Suppl 1):7411515430p1. 10.5014/ajot.2020.74S1-PO6802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boucher NR. Relationships between Characteristics of autism spectrum disorder and BDSM behaviors [Undergraduate Honors Thesis. Ball state university]. 2018;Honr499. https://cardinalscholar.bsu.edu/handle/123456789/201533 Accessed October 7, 2022.

- 28. Simula BL. Pleasure, power, and pain: A review of the literature on the experiences of BDSM participants. Sociol Compass. 2019;13(3):e12668. 10.1111/soc4.12668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walker N. Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities. US: Autonomous Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hammack PL, Frost DM, Hughes SD. Queer intimacies: A new paradigm for the study of relationship diversity. J Sex Res. 2019;56(4–5):556-592. 10.1080/00224499.2018.1531281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harding S. Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Botha M. Critical realism, community psychology, and the curious case of autism: A philosophy and practice of science with social justice in mind. J Community Psychol. 2021. [Epub ahead of print]; 10.1002/jcop.22764. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33. Kourti M. A Critical realist approach on autism: ontological and epistemological implications for knowledge production in autism research. Front Psychol. 2021;12(December):1–15. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith JA. Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2004;1(1):39–54. 10.1191/1478088704qp004oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pietkiewicz I, Smith JA, Pietkiewicz I, Smith JA. A practical guide to using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in qualitative research psychology. Czas Psychol Psychol J. 2014;20(1):7–14. 10.14691/cppj.20.1.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chapman R, Carel H. Neurodiversity, epistemic injustice, and the good human life. J Soc Philos. 2022;53(4):614–631. 10.1111/josp.12456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leedham A, Thompson AR, Smith R, Freeth M. ‘I was exhausted trying to figure it out’: The experiences of females receiving an autism diagnosis in middle to late adulthood. Autism. 2019;24(1):135–146. 10.1177/1362361319853442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Giwa Onaiwu M. “They Don't Know, Don't Show, or Don't Care”: Autism's white privilege problem. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2(4):270–272. 10.1089/aut.2020.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, Kapp SK, et al. The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism. 2019;23(8):2007–2019. 10.1177/1362361319830523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pearson A, Rose K. A conceptual analysis of autistic masking: Understanding the narrative of stigma and the illusion of choice. Autism Adulthood Challenges Manag. 2021;3(1):52–60. 10.1089/aut.2020.0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hull L, Petrides KV, Allison C, et al. “Putting on My Best Normal”: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(8):2519–2534. 10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reardon E. Sensory Joy and Healing. Undercover Autism: An Insider's Experience. Published 2020. https://undercoverautism.org/2020/08/03/sensory-joy-and-healing/#site-header Accessed October 7, 2022.

- 43. Deterding S. Alibis for adult play: A Goffmanian account of escaping embarrassment in adult play. Games Cult. 2017;13(3):260–279. 10.1177/1555412017721086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Andrews EE, Ayers KB, Stramondo JA, Powell RM. Rethinking systemic ableism: A response to Zagouras, Ellick, and Aulisio. Clin Ethics. 2022;18(1):7–12. 10.1177/14777509221094472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Frost DM. Social stigma and its consequences for the socially stigmatized. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2011;5:824–839. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00394.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mantzalas J, Richdale AL, Adikari A, Lowe J, Dissanayake C. What is autistic burnout? A thematic analysis of posts on two online platforms. Autism Adulthood Challenges Manag. 2022;4(1):52–65. 10.1089/aut.2021.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ai W, Cunningham WA, Lai MC. Reconsidering autistic “camouflaging” as transactional impression management. Trends Cogn Sci. 2022;26(8):631–645. 10.1016/j.tics.2022.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thomas JN. BDSM as trauma play: An autoethnographic investigation. Sexualities. 2019;23(5–6):917–933. 10.1177/1363460719861800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Proff I, Williams GL, Quadt L, Garfinkel SN. Sensory processing in autism across exteroceptive and interoceptive domains. Psychol Neurosci. 2022;15:105–130. 10.1037/pne0000262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van Es T, Bervoets J. Autism as gradual sensorimotor difference: From enactivism to ethical inclusion. Topoi. 2022;41(2):395–407. 10.1007/s11245-021-09779-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Botha M, Frost DM. Extending the minority stress model to understand mental health problems experienced by the autistic population. Soc Ment Health. 2020;10(1):20–34. 10.1177/2156869318804297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Weinberg TS. Sadomasochism and the social sciences. J Homosex. 2006;50(2–3):17–40. 10.1300/J082v50n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bottema-Beutel K, Kapp SK, Lester JN, Sasson NJ, Hand BN. Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers. Autism Adulthood. 2021;3(1):18–29. 10.1089/aut.2020.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Klin A, Danovitch JH, Merz AB, Volkmar FR. Circumscribed interests in higher functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders: An exploratory study. Res Pract Pers Sev Disabil. 2007;32(2):89–100. 10.2511/rpsd.32.2.89. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pyne J. Autistic disruptions, trans temporalities: A narrative “Trap Door” in time. South Atl Q. 2021;120(2):343–361. 10.1215/00382876-8916088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data for this project are not available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.