Abstract

Background

The number of older people is increasing worldwide and public expenditure on residential aged care facilities (ACFs) is expected to at least double, and possibly triple, by 2050. Co‐ordinated and timely care in residential ACFs that reduces unnecessary hospital transfers may improve residents' health outcomes and increase satisfaction with care among ACF residents, their families and staff. These benefits may outweigh the resources needed to sustain the changes in care delivery and potentially lead to cost savings. Our systematic review comprehensively and systematically presents the available evidence of the effectiveness, safety and cost‐effectiveness of alternative models of providing health care to ACF residents.

Objectives

Main objective

To assess the effectiveness and safety of alternative models of delivering primary or secondary health care (or both) to older adults living in ACFs.

Secondary objective

To assess the cost‐effectiveness of the alternative models.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, five other databases and two trials registers (WHO ICTRP, ClinicalTrials.gov) on 26 October 2022, together with reference checking, citation searching and contact with study authors to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included individual and cluster‐randomised trials, and cost/cost‐effectiveness data collected alongside eligible effectiveness studies. Eligible study participants included older people who reside in an ACF as their place of permanent abode and healthcare professionals delivering or co‐ordinating the delivery of healthcare at ACFs. Eligible interventions focused on either ways of delivering primary or secondary health care (or both) or ways of co‐ordinating the delivery of this care. Eligible comparators included usual care or another model of care. Primary outcomes were emergency department visits, unplanned hospital admissions and adverse effects (defined as infections, falls and pressure ulcers). Secondary outcomes included adherence to clinical guideline‐recommended care, health‐related quality of life of residents, mortality, resource use, access to primary or specialist healthcare services, any hospital admissions, length of hospital stay, satisfaction with the health care by residents and their families, work‐related satisfaction and work‐related stress of ACF staff.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies for inclusion, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias and certainty of evidence using GRADE. The primary comparison was any alternative model of care versus usual care.

Main results

We included 40 randomised trials (21,787 participants; three studies only reported number of beds) in this review.

Included trials evaluated alternative models of care aimed at either all residents of the ACF (i.e. no specific health condition; 11 studies), ACF residents with mental health conditions or behavioural problems (12 studies), ACF residents with a specific condition (e.g. residents with pressure ulcers, 13 studies) or residents requiring a specific type of care (e.g. residents after hospital discharge, four studies). Most alternative models of care focused on 'co‐ordination of care' (n = 31). Three alternative models of care focused on 'who provides care' and two focused on 'where care is provided' (i.e. care provided within ACF versus outside of ACF). Four models focused on the use of information and communication technology. Usual care, the comparator in all studies, was highly heterogeneous across studies and, in most cases, was poorly reported. Most of the included trials were susceptible to some form of bias; in particular, performance (89%), reporting (66%) and detection (42%) bias.

Compared to usual care, alternative models of care may make little or no difference to the proportion of residents with at least one emergency department visit (risk ratio (RR) 1.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.84 to 1.20; 7 trials, 1276 participants; low‐certainty evidence), but may reduce the proportion of residents with at least one unplanned hospital admission (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.99, I2 = 53%; 8 trials, 1263 participants; low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain of the effect of alternative models of care on adverse events (proportion of residents with a fall: RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.60, I² = 74%; 3 trials, 1061 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) and adherence to guideline‐recommended care (proportion of residents receiving adequate antidepressant medication: RR 5.29, 95% CI 1.08 to 26.00; 1 study, 65 participants) as the certainty of the evidence is very low. Compared to usual care, alternative models of care may have little or no effect on the health‐related quality of life of ACF residents (MD ‐0.016, 95% CI ‐0.036 to 0.004; I² = 23%; 12 studies, 4016 participants; low‐certainty evidence) and probably make little or no difference to the number of deaths in residents of ACFs (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.16, 24 trials, 3881 participants, moderate‐certainty evidence).

We did not pool the cost‐effectiveness or cost data as the specific costs associated with the various alternative models of care were incomparable, both across models of care as well as across settings. Based on the findings of five economic evaluations (all interventions focused on co‐ordination of care), we are uncertain of the cost‐effectiveness of alternative models of care compared to usual care as the certainty of the evidence is very low.

Authors' conclusions

Compared to usual care, alternative models of care may make little or no difference to the number of emergency department visits but may reduce unplanned hospital admissions. We are uncertain of the effect of alternative care models on adverse events (i.e. falls, pressure ulcers, infections) and adherence to guidelines compared to usual care, as the certainty of the evidence is very low. Alternative models of care may have little or no effect on health‐related quality of life and probably have no effect on mortality of ACF residents compared to usual care. Importantly, we are uncertain of the cost‐effectiveness of alternative models of care due to the limited, disparate data available.

Keywords: Aged, Humans, Health Personnel, Homes for the Aged, Primary Health Care, Quality of Life, Secondary Care

Plain language summary

Alternative ways to organise delivery of health care to older adults living in aged care facilities

What is the aim of this review?

This Cochrane review set out to determine if providing residents of aged care facilities (ACF) with the same care as usual care, just delivered in a different way (alternative models of care), is better in terms of emergency department transfers, unplanned hospital admissions, adverse events, adherence to clinical guideline‐recommended care, health‐related quality of life, mortality and costs. For example, are multidisciplinary teams (alternative model) a better way of delivering care to residents of ACFs compared to providing care through individual practitioners (usual care)?

Key messages

Compared to usual care, alternative models of care may reduce unplanned hospital admissions, but may make little or no difference to the number of emergency department visits and the health‐related quality of life of ACF residents, and probably make little or no difference to mortality. We are uncertain of the effect of alternative models of care on adverse events (i.e. falls, pressure ulcers, infections) and adherence to guideline‐recommended care. Importantly, we are uncertain whether alternative models of care are cost‐effective due to the limited, conflicting data available.

Studies differed widely in terms of intervention characteristics, health care settings and descriptions of usual care and this hindered many analyses in this review. Future studies should provide a detailed description of what intervention and usual care constitutes in their setting.

What was studied in this review?

The world's population is ageing and the number of persons living in residential ACFs is growing worldwide. ACF residents are often frail, elderly people with multiple health conditions that require intensive medical care. When an ACF is not able to deliver appropriate health care, residents are often transferred to a hospital for treatment. Such transfers are often burdensome and traumatic for ACF residents and their families and may lead to increased costs. Alternative models of care, designed to provide care that is better co‐ordinated and more timely, aim to reduce unnecessary hospital transfers and improve residents' well‐being. Alternative models of care may be more expensive to implement (e.g. employ more healthcare personnel) but may lead to cost savings down the line (e.g. more residents receive care in ACF, avoiding costly hospital transfers). The synthesised evidence in this review compares the effect of alternative models of care with usual care on the number of emergency department transfers, unplanned hospital admissions, adverse events, adherence to clinical guideline‐recommended care, health‐related quality of life, mortality and costs (i.e. does the model deliver better value for money compared to usual care).

What are the main results of this review?

We identified 40 studies (with in total 21,787 participants; three studies did not provide number of participants) conducted in 15 countries. The study participants differed with respect to their health needs. In 11 studies, the alternative model of care was aimed at all ACF residents (with mixed health needs/conditions). Other studies included residents with mental health conditions or behavioural problems (12 studies), ACF residents with a specific condition (e.g. residents with pressure ulcers; 13 studies) or residents requiring a specific type of care (e.g. residents after discharge from a hospital; four studies). In most (31) of the studies, the alternative model of care focused on 'co‐ordination of care'. In three studies, the alternative models of care focused on 'who provides care' (e.g. nurse practitioner‐led care using best practice guide instead of GP‐led care) and in two studies, alternative models of care focused on 'where care is provided' (i.e. investigating alternative locations for the provision of care, for example within ACF versus outside of ACF). In four studies, the alternative models of care focused on the use of information and communications technology for the provision of care to ACF residents. In all studies, the alternative model of care was compared with usual care.

We found that, compared to usual care, alternative models of care may make little or no difference to the number of emergency department visits; however, the number of unplanned hospital admissions may be reduced. We are uncertain of the effect of alternative models of care on adverse events and adherence to clinical guideline‐recommended care compared with usual care. Alternative models of care may have little or no effect on ACF residents' health‐related quality of life and probably make little or no difference to mortality. Based on the findings of five studies that provided full economic evaluations (all alternative models of care focused on 'co‐ordination of care'), we are uncertain whether alternative models of care are more cost‐effective than usual care.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Our confidence in the evidence is limited because participants in the studies were aware of which treatment they were getting. Usual care was poorly described by most of the studies. Usual care differs across countries and regions, so this lack of information limits our interpretation, contextualisation and generalisation of the comparisons. Not all of the studies provided data about outcomes we were looking to assess.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies published up to October 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings: Any alternative model of care versus usual care.

| Any alternative model of care compared with usual care for residents of aged care facilities | ||||||

|

Patient or population: residents of aged care facilities Settings: residential aged care facility Intervention: any alternative model of care Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With usual care | With alternative model of care | |||||

|

Emergency department (ED) visits: proportion of residents with at least one ED visit at longest follow‐up (follow‐up: 1 to 32 months) |

200 per 1000 | 2 more per 1000 (from 32 fewer to 40 more) | RR 1.01 (0.84 to 1.20) | 1276 (7) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Eleven studies reported on ED visits and measured this in different ways. Based on a meta‐analysis of 7 studies, alternative models of care may make little or no difference to the proportion of residents with at least one ED visit compared to usual care. Other measures were mean number of ED visits per resident and rate of ED visits per person‐time. We are uncertain of the effect of alternative models of care on these measures of ED visits as the certainty of the evidence for both of these outcomes is very low. Three studies not incorporated into the meta‐analyses reported the following: Haines 2020 reported a reduction in the mean number of unplanned hospital transfers per site in the intervention group, per 9‐week block; Wu 2010 reported that there were no ED visits in either group; Cavalieri 1993 reported that emergency room visits were "more frequent for the usual care group than the intervention group". |

|

Unplanned hospital admissions: proportion of residents with at least one unplanned hospital admission at longest follow‐up (follow‐up: 21 days to 32 months) |

320 per 1000 | 83 fewer per 1000 (141 fewer to 3 fewer) | RR 0.74 (0.56 to 0.99) | 1263 (8) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | Twelve studies reported on unplanned hospital admissions and measured this in different ways. Based on a meta‐analysis of 8 studies, alternative models of care may reduce the proportion of residents with unplanned hospitalisations compared to usual care. Other measures were mean number of unplanned admissions per resident and rate of unplanned hospital admissions. While we are uncertain of the effect of alternative models of care on the mean number of unplanned admissions per resident, as the certainty of the evidence is very low,alternative models of care may make little or no difference to the rate of unplanned hospital admissions compared to usual care. Haines 2020 (not included in any meta‐analysis) reported a reduction in the mean number of unplanned hospital admissions per site, per 9‐week block in the intervention group. |

|

Adverse events/falls: proportion of residents with a fall at longest follow‐up (follow‐up: 1 to 24 months) |

255 per 1000 | 38 more per 1000 (from 43 fewer to 153 more) | RR 1.15 (0.83 to 1.60) | 1061 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowc | Eight studies reported on adverse events (including falls, pressure ulcers and infections) and measured these outcomes in different ways. Six studies reported on falls. Based on a meta‐analysis of 3 studies, we are uncertain of the effect of alternative models of care on the proportion of residents with a fall compared to usual care,as the certainty of the evidence is very low. Other measures were mean number of falls per resident, rate of falls, proportion of residents with an injurious fall, mean number of injurious falls, incidence of pressure ulcers, proportion of residents with an infection, mean number of infections per resident and infection rate per person‐time. Alternative models of care may have little or no effect on the mean number of falls per resident compared to usual care. We are uncertain of the effect of alternative models of care on the rate of falls, proportion of residents with an injurious fall, mean number of injurious falls, incidence of pressure ulcers, proportion of residents with an infection, mean number of infections per resident and infection rate per person‐time as the certainty of the evidence for these outcomes is very low. |

|

Adherence to clinical guideline‐recommended care: proportion of residents with adequate antidepressant therapy at longest follow‐up (follow‐up: 3 months) |

45 per 1000 | 195 more per 1000 (from 4 more to 1125 more) | RR 5.29 (1.08 to 26.00) | 65 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowd | Three studies reported on adherence to clinical guideline‐recommended care and measured it in different ways. Based on one study assessing adequate antidepressant therapy, we are uncertain of the effect of alternative models of care on adherence to guidelines compared to usual care as the certainty of the evidence is very low. Other measures of guideline‐recommended care were adequate antipsychotic therapy, adequate antibiotic prescription and medication appropriateness.We are uncertain of the effect of alternative models of care on these outcomesas the certainty of the evidence is very low. |

|

Health‐related quality of life (mean difference) at longest follow‐up (EQ‐5D, scale 0 to 1, higher is better) (follow‐up: 1 to 21 months) |

The mean change from baseline (in EQ‐5D‐3L index score) after 6 months in the usual care group was 0.07e | — | MD 0.016 lower (0.036 lower to 0.004 higher)f | 4016 (12) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowg | Fourteen studies reported on health‐related quality of life. Based on a meta‐analysis of 12 studies, alternative models of care may have little or no effect on health‐related quality of life compared to usual care. Findings of the 2 studies not included in meta‐analysis: De Luca 2016 reported a higher median EUROQoL score in the intervention group compared to the usual care group; Harvey 2014 did not provide any data but reports the following regarding quality of life: "There were no significant differences between groups in quality of life at baseline and no significant changes within either group over time." |

|

Mortality: proportion of residents who died at longest follow‐up (follow‐up: 1 to 24 months) |

205 per 1000 | 6 more per 1000 (from 16 fewer to 33 more) | RR 1.03 (0.92 to 1.16) | 3881 (24) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateh | Twenty‐five studies reported on this outcome. Based on a meta‐analysis of 24 studies, alternative models of care probably make little or no difference tothe proportion of residents who died compared to usual care. Haines 2020 (not included in meta‐analysis) reported a higher mean number of deaths per site, per 9‐week block in the intervention group. |

|

Resource use: cost‐effectiveness evaluations (6 to 21 months) |

Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | 2341 (5) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowi | Eleven studies reported on costs of care or cost‐effectiveness evaluations (or both). Due to the heterogeneity of the interventions, settings and study time frames, it was not possible to pool cost estimates. Based on 5 economic evaluations, we are uncertain of the cost‐effectiveness of alternative models of care compared to usual care as the certainty of the evidence is very low. Other reported measures included total cost of health care, cost of primary/secondary care, inpatient cost, ED admissions cost, medication costs, informal care costs, staff costs and intervention implementation costs. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; ED: emergency department; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded once for serious risk of bias (all studies at high risk of performance bias, one study at high risk of detection bias) and once for serious imprecision (analyses not powered to detect important harm or benefit).

bDowngraded once for serious risk of bias (all studies at high risk of performance bias) and once for serious inconsistency (I2 = 59%).

cDowngraded once for serious risk of bias (two studies at unclear risk of selection and detection bias), once for serious inconsistency (I2 = 74%) and once for serious imprecision (very wide CIs, which include both no effect and important harm).

dDowngraded once for serious risk of bias (one study at high risk of performance bias), once for serious indirectness (one study limited to a population with mental health problems and intervention related to medication use, which limits the generalisability of findings to other care models/other resident populations) and twice for very serious imprecision (wide confidence intervals that include no appreciable benefit and very large benefit).

eData from usual care group in Man 2020. Man 2020 was deemed to be the most representative study (Stern 2014 (weight 21%) and Van den Block 2020 (weight 27.8%) ‐ no baseline SD provided for control groups).

fHealth‐related quality of life was assessed using different instruments in the eligible studies, so we combined the data using a standardised mean difference. We used the SD provided by Man 2020 (0.4 on a 0 to 1 EQ‐5D index scale) for quality of life at baseline in the usual care group to back‐translate the SMD (SMD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.01) to the MD (Higgins 2021).

gDowngraded once for serious risk of bias (all studies at high risk of performance bias) and once for serious publication bias.

hDowngraded once for serious publication bias.

iDowngraded once for serious risk of bias (all studies at high risk of performance bias), once for serious inconsistency and once for serious imprecision.

Background

In almost every country in the world, the number and proportion of older people is increasing. It is projected that by 2050, one in six (16%) people in the world will be over 65 years of age, almost double the rate noted in 2019 of one in 11 (9%) (UN 2019). The number of people aged 80 years or older is projected to triple, from 143 million in 2019 to 426 million in 2050 (UN 2019).

Across Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) countries, an average of 10.8% of people aged 65 years and over received long‐term care in 2017. This represents a 5% increase compared with 2007 (OECD 2019). Most OECD countries allocate approximately 1% to 1.5% of their gross domestic product (GDP) to long‐term care of the elderly. However, given the current ageing trends, public long‐term care expenditure is expected to at least double, and possibly triple, by 2050 (OECD 2011). Identifying the most efficient models of long‐term care that best serve the needs of older aged people has been included as a strategic objective in the WHO Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health (WHO 2017).

Residents of aged care facilities (ACFs) are often frail with a number of chronic health conditions (e.g. diabetes or heart conditions) that require regular monitoring and management. In the event of an injury, altered mental state, acute infection, or exacerbation or complication of an underlying condition, residents require acute care services. Currently, people living in residential care are commonly transported to hospital for care that might otherwise be managed within the residential care facility. Available evidence suggests that complications associated with underlying conditions may be prevented with earlier identification of risk and appropriate management (Bowman 2001; Lemoyne 2019). Recent reviews have found that 4% to 55% of all acute transfers of nursing home residents are classified as inappropriate and are associated with a high risk of complications and mortality (Dwyer 2017; Lemoyne 2019).

Description of the condition

Hospitalisation of residents of ACFs is distressing and often burdensome for both the residents and their families, and potentially more costly for all (King 2013; Wong 2010). Locating specialised nurses, nursing teams, general practitioners (GPs) and specialist physicians (e.g. geriatricians) in ACFs, or improving collaboration between these healthcare professionals and ACF staff, may improve co‐ordination and quality of care, reduce unplanned hospital transfers, enhance resident well‐being and resident and staff satisfaction, and potentially reduce healthcare costs (Lemoyne 2019).

Description of the intervention

The way in which primary or secondary medical care (or a combination of these) is delivered to residents of ACFs is the main focus of this review. Our focus is not limited to a single model or intervention, but rather covers a number of alternative ways in which primary or secondary care can be organised and delivered to older adults living in ACFs. In the absence of agreed‐upon definitions, the term primary care is often used interchangeably with first level of contact with the healthcare system. Primary care may be provided by a range of professionals, including primary care physicians and nurses. Primary care covers preventive, curative and rehabilitative services (OECD 2023; WHO 2023). Secondary care is specialist care, usually following a referral from a primary care provider (WHO 2023). Our review will investigate the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of different models of providing health care in this population. Possible models of delivering medical care to residents of ACFs may include, but are not limited to, the following.

Hospital in‐reach models of care (provision of care in ACFs by hospital staff, as an alternative to in‐patient stay)

In‐reach services are provided by hospital staff to residents of ACFs requiring acute care. Services provided by in‐reach models may include advanced assessment and management of unwell or injured residents, provision of subcutaneous fluids and intramuscular medications, catheter or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy troubleshooting, and specialist palliative care support. An example of an in‐reach service model is Hospital in the Nursing Home (HiNH). In this model, clinical staff are allocated to manage older adults living in ACFs with actual or potential acute symptoms, which would otherwise require either an emergency department visit or hospital admission (Fan 2015).

Nurse‐led care alone or within the context of a complex care co‐ordination intervention

Examples of nurse‐led care include care delivered to residents of ACFs by nurse practitioners co‐located in the ACF and working in collaboration with GPs (primary care) (Arendts 2018) or gerontology nurse specialists co‐located in the ACF and providing staff education and care co‐ordination within a multidisciplinary team (Boyd 2014; Connolly 2013; Connolly 2015).

Provision of general practitioner services within ACFs

Such models include the Continuity of Care model, where GPs continue to provide care for long‐term patients when they move into an ACF through regular on‐site visits; the ACF Panel model, where GPs either take on patients from nearby residential ACFs or become the dedicated GP for a residential ACF; the GPs with Special Interest in Residential Aged Care model, where GPs provide regularly scheduled services to groups of patients in a number of different ACFs; the Longitudinal General Practice Team model, where GPs work with nurse practitioners to provide team‐based care to residents of ACFs; and ACF‐based models of GP care, where GPs are employed by, and have their practices located within, ACFs (Haines 2020; Reed 2015).

Multidisciplinary team care

Residents of ACFs often have multiple morbidities that require care from different healthcare professionals. Effective interventions for chronic diseases generally rely on multidisciplinary team approaches. Multidisciplinary integrated care at ACFs may be an alternative for providing care on request (Boorsma 2011a).

Provision of primary care or specialist services through video‐conferencing (telehealth) versus face‐to‐face

Modern technologies provide the ability to incorporate video conferencing/telehealth as part of medical care for the elderly without a need for travel. An example of the use of telehealth in nursing homes can be video consultations by a wound specialist for patients with problematic, non‐healing wounds (Dobke 2008).

How the intervention might work

Inadequate training or understaffing (or both) of ACFs’ workforces may limit their ability to manage the chronic or acute care needs of residents, resulting in increased emergency department visits and unplanned hospital admissions, some of which may be unnecessary. Not only are these costly, they are often traumatic for the ACF resident and their family.

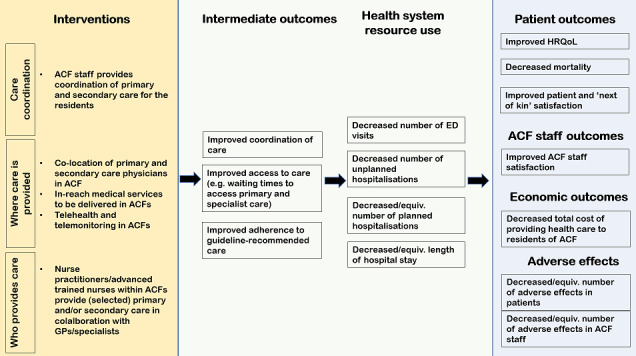

Alternatively, in order to attend to residents' chronic or acute care needs, a GP could be on‐site, or an ACF staff member could be dedicated to co‐ordinating the delivery of care by both internally and externally located physicians. This may lead to improved access to guideline‐recommended and better co‐ordinated care, which is expected to result in reduced emergency department visits and unplanned hospital admissions. Well co‐ordinated and timely care, without unnecessary hospital transfers, is hypothesised to improve health outcomes of residents and to increase satisfaction with care among the residents, their families and staff. The benefits associated with reducing the number of hospital transfers and unplanned admissions may outweigh the resources needed to sustain the changes in care delivery, and potentially lead to cost savings. Interventions of interest and expected pathways to outcomes of interest are presented in Figure 1.

1.

Intervention logic model

Why it is important to do this review

This topic is important given that the increasing number and proportion of older people globally will increase the demand for efficient and effective aged care services (Davies 2011). The costs of caring for older people, particularly residents of ACFs, who are often frail with multiple comorbidities, is significant and increasing (OECD 2011). Delivering clinically effective and cost‐effective primary or specialist medical or nursing care (or both) to residents of ACFs will not only improve residents’ access to, and quality of, care, but may also reduce the rate of emergency department visits and unplanned hospital admissions. It is expected that this will improve the physical and psychological well‐being of ACF residents and their families, and ultimately reduce the total costs of providing medical care for older adults living in ACFs.

A variety of different models of providing better health care for residents of ACFs have been postulated and investigated. Our systematic review aims to comprehensively and systematically collate the available evidence of the effectiveness, safety and cost‐effectiveness of the different models of providing health care to residents of ACFs.

Objectives

Main objective

To assess the effectiveness and safety of alternative models of delivering primary or secondary health care (or both) to older adults living in ACFs.

Secondary objective

To assess the cost‐effectiveness of the alternative models.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials, including cluster‐randomised trials. Cluster‐randomised trials were required to have at least two intervention and two control sites to be considered eligible for inclusion, to reduce potential bias from site‐specific confounding (EPOC 2017). Cross‐over trials were not included.

The following types of economic evaluation studies were considered for inclusion: full economic evaluation studies (i.e. cost‐effectiveness analyses, cost‐utility analyses, cost‐benefit analyses), partial economic evaluations (i.e. cost analyses, cost‐description studies, cost‐outcome descriptions), and randomised trials reporting more limited information, such as estimates of resource use or costs associated with intervention(s) and comparator(s). We only considered relevant health economics studies conducted alongside effectiveness studies that met the eligibility criteria for the effectiveness component of this review (Aluko 2020). We considered studies irrespective of their publication date, publication status or language of publication. Where possible, we translated the studies published in non‐English languages.

Types of participants

Eligible study participants included healthcare professionals delivering or co‐ordinating healthcare to older adults living in ACFs, and older people residing in a care home as their place of permanent abode. We defined older people as those aged 60 years or over, and we included all participants in studies where the mean age was 60 years or more.

Aged care facilities are called different things in different countries. The terms “care home”, “residential aged care facility”, “nursing home”, “aged care”, “residential/subacute/extended aged care settings”, “restorative care”, “rest homes”, “skilled nursing facilities” and “homes for the aged” are used interchangeably. No matter what the facility is called, only facilities that meet all the criteria for ‘care home’ set out in Crocker 2013 and Ward 2008 were eligible for inclusion. Such facilities provide:

communal living facilities for long‐term care (as opposed to hospital, where there is an expectation that this care is time‐limited);

overnight accommodation;

nursing or personal care; and

care for people with illness, disability or dependence.

Types of interventions

Eligible interventions focused on either ways of delivering primary or secondary health care (or both) or ways of co‐ordinating the delivery of this care. The term primary care is often used interchangeably with first level of contact with the healthcare system. Primary care may be provided by a range of professionals including primary care physicians and nurses and covers preventive, curative and rehabilitative services (OECD 2023; WHO 2023). Secondary care is specialist care, usually following a referral from a primary care provider (WHO 2023).

Eligible models of care delivery had to investigate changes to at least one of the following delivery arrangement domains (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy of health system interventions; EPOC 2015):

co‐ordination of the primary or secondary (or both) health care, or management of the primary or specialist (or both) care processes (e.g. continuity of care models; protocols for care decisions or decision support; nurse practitioners working collaboratively with GPs; care provision by multidisciplinary teams);

where the primary or secondary (or both) health care is provided (e.g. co‐location of primary medical care or secondary care services within ACFs; Hospital in the Nursing Home; in‐reach of specialists or specialised nursing teams for routine or emergency care; telemedicine to assist with provision of primary/secondary care services to residents of ACFs); or

who provides the primary or secondary (or both) health care (e.g. provision of primary or secondary care services (or both) to residents of ACFs by nurse practitioners; medical treatment provided by multidisciplinary teams of experts).

We considered studies irrespective of the medical specialisation of the healthcare professional involved in delivering the various models of health care. We excluded care provided by allied health professionals (e.g. physiotherapy) or pharmacist‐led interventions, except when they were part of a multidisciplinary team or were providing primary or specialist medical care to residents of ACFs.

Eligible comparators included usual care or another model of care, as defined by the trialists. A key aspect of this review is that both the experimental group and the comparison group needed to receive the same primary or specialist healthcare services, just in a different way (e.g. primary care services provided by a GP who is a staff member of the ACF versus provision of primary care to ACF residents on request by an external GP). A detailed description of usual care was important for a meaningful interpretation of the effects of interventions in this review, because the organisation and delivery of medical care to residents in ACFs was expected to be different within and between countries. We described the interventions, including usual care, using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist (Hoffmann 2014).

We excluded studies focusing on ways of providing dental care. We also excluded studies looking at more effective ways of providing general care to ACF residents, such as bathing or feeding. We excluded studies focused primarily on nursing staffing models for existing staff employed within ACFs (i.e. how existing ACF nursing and personal care attendant staffing is organised to meet resident/patient needs, including the mix and level of skills, and staffing ratios), as this is the focus of a separate Cochrane review (Hodgkinson 2011).

Medication review for older people in residential care is a focus of several other Cochrane reviews (Alldred 2016; LaMantia 2010; Rankin 2018), so this intervention was not considered in this review unless it was part of a more complex intervention (e.g. general medical in‐reach review) that includes other eligible elements. Studies investigating the introduction of new treatments (i.e. adding services such as cognitive behavioural therapy for dementia; or social prescribing, e.g. visits from school children or music therapy providers), were not considered in this review. Interventions focused exclusively on education of staff, skill development or quality improvement (e.g. interventions that focus primarily on education, information campaigns, audit and feedback, provider reminders, computerised medical records, enhanced automated patient monitoring systems, financial incentives, guideline implementation or guideline adherence) were also outside the scope of this review.

Types of outcome measures

The outcomes in this review were designed to capture the key health, quality‐of‐care and economic effects of alternative ways of delivering or co‐ordinating healthcare (or both) to older adults living in ACFs. While cognitive and functional status outcomes are relevant outcomes to this patient population, they were not the focus of this review, which aims to investigate the effects of different ways of delivering or co‐ordinating the same primary or secondary healthcare. Studies were not selected based on outcomes reported.

Primary outcomes

Emergency department visits, reported at longest follow‐up

Unplanned hospital admissions, reported at longest follow‐up

Adverse effects (defined as infections, falls and pressure ulcers), reported at longest follow‐up

Secondary outcomes

Adherence to clinical guideline‐recommended care, reported at longest follow‐up

Health‐related quality of life of residents, as measured by generic scales (e.g. 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) (mental component score) or EuroQol 5 dimensions (EQ5D)) at longest follow‐up. If no generic scale was provided, we used a disease‐specific quality of life scale, if available.

Mortality, reported at longest follow‐up

Resource use (i.e. resources needed to deliver the intervention, total costs of care or types of care (e.g. hospital care, GP care), economic outcomes from cost‐effectiveness analyses, cost‐utility analyses or cost‐benefit analyses)

Access to primary or specialist healthcare services (e.g. waiting times to see the GP or specialist), reported at longest follow‐up

Any hospital admissions, reported at longest follow‐up

Length of stay for any hospital admission, reported at longest follow‐up

Residents’ satisfaction with the health care received, as measured by the trial and reported at longest follow‐up

'Next of kin' satisfaction with the health care provided to the resident, as measured by the trial and reported at longest follow‐up

Work‐related satisfaction of ACF staff, pertaining to the health care provided to the residents, as measured in the trial and reported at longest follow‐up

Work‐related stress/burnout of ACF staff, as measured in the trial and reported at longest follow‐up

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The review authors developed the search strategies in consultation with the Cochrane EPOC Information Specialist. We searched the following databases for primary studies, from inception to 26 October 2022. See Appendix 1 for search strategies.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2022, Issue 10), in the Cochrane Library;

MEDLINE via Ovid (1946 to 26 October 2022);

Embase via Ovid (1980 to 2022 week 43);

Age Line EBSCO (1944 to 2022 week 43);

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (1980 to 2022 week 43).

The following databases were searched to identify eligible economic evaluations:

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED 2015, Issue 2);

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry (CEA) 1976 to 2022 week 43;

MEDLINE Ovid from 2015 to 2022 week 43.

Search strategies comprised keywords and controlled vocabulary terms. We did not apply any limits on language and we searched all databases from inception to 26 October 2022. We used a study design filter to identify randomised trials. The study design filter was developed by the Cochrane EPOC Information Specialist, and published in our protocol, after peer review (Putrik 2021). It is a slight modification of the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy (Lefebvre 2021) and is widely used in EPOC reviews (Purgato 2023).

Searching other resources

To identify completed but unpublished, ongoing and planned trials, the following registries were searched on 26 October 2022:

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (ClinicalTrials.gov; www.clinicaltrials.gov).

We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) for related systematic reviews. We screened the included studies of these reviews to identify any additional eligible studies. We also handsearched reference lists of all included studies to identify additional potentially eligible studies. We contacted authors of included studies to clarify reported published information, or to seek unpublished results/data if needed. See Appendix 1 for search strategies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We imported all records retrieved from the search into Covidence (www.covidence.org) to facilitate deduplication and subsequent independent duplicate screening of titles and abstracts and potentially eligible full‐text papers. We also used Covidence to facilitate the assessment of risk of bias in included studies.

Two of four review authors (PP, LG, AL, HR) independently screened titles and abstracts for potentially eligible studies. The full texts of all potentially eligible studies were independently screened by two review authors (PP, LG, AL, HR) to identify eligible studies. We listed all studies excluded at this stage, together with reasons for exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We resolved any disagreement through discussion; if required, we consulted a senior author (DOC or RB).

We collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study rather than each published report is the unit of analysis in the review. We reported basic information on any eligible ongoing studies we identified. We recorded the study selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

We adapted the Cochrane EPOC standard data collection form and used it to extract study characteristics and outcome data (EPOC 2017). We piloted the form on at least one eligible study in the review. Two review authors (PP, LG, AL, HR) independently extracted the following study characteristics from the included studies:

Methods: study design, number of study centres and location, study setting, withdrawals, date of study, duration of follow‐up.

Participants: number, mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition(s) where relevant, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, other relevant ACF resident characteristics.

Intervention and categorised: classified according to the EPOC taxonomy of health system interventions and described using TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann 2014), including the nature of primary or specialist healthcare provided.

Outcomes: all outcomes planned and reported on, with time points and methods of data collection.

Notes: funding source for trial, conflicts of interest of trial authors, ethical approval.

We developed a data extraction form for economic evaluations based on the format and guidelines used to produce structured abstracts of economic evaluations for inclusion in the NHS EED, adapted to the specific requirements of this review. We resolved differences in extracted data by consensus or by involving a fourth review author (DOC). If important information was missing from the full‐text article, we contacted the authors of the publication to obtain it.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (PP, LN, AL, HR) independently assessed risk of bias for each included study using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011) and additional criteria specified by Cochrane EPOC (EPOC 2017). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by consulting a senior author (DOC or RB). The risk of bias assessment included the following domains.

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting

Other bias (bias due to problems not covered by sources of bias specified above; for cluster‐randomised trials, the following specific issues were assessed: recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, protection against contamination, incorrect analysis)

We judged each study to be at high, low or unclear risk of bias for each domain listed above, and we provided justification for our judgement in the risk of bias table for each study. We assessed information from study reports, protocols, trial registration documents or correspondence with trialists to support our judgement. Where information on risk of bias is related to correspondence with trialists or unpublished data, we noted this in the risk of bias table. We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed and included the summary figure generated by Review Manager software (Review Manager 2020). If the clusters of a cluster‐randomised trial were all allocated to the treatment groups at the same time, we judged allocation concealment to be low risk, even if the study authors did not provide explicit information regarding the allocation concealment process.

When considering intervention effects, we took account of the risk of bias for the studies that contribute to that outcome and incorporated this into our judgements about the certainty of the evidence. A summary assessment of the risk of bias of each study was done using three key domains: sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), and blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias). Studies were considered to be at low risk of bias if the three key domains were at low risk of bias; unclear risk of bias if at least one of the domains was unclear risk of bias and none of the domains were at high risk of bias; and high risk of bias if at least one of the key domains was at high risk of bias.

Each economic evaluation was classified as: (1) a type of full economic evaluation; (2) a type of partial economic evaluation; or (3) a type of effectiveness study (e.g. a randomised trial) reporting more limited information on the resource use or costs associated with an intervention. For types (1) and (2), the economic studies were classified as a single study design (e.g. an economic evaluation alongside a randomised trial) or a model‐based evaluation, involving the synthesis of evidence derived from multiple studies or data sources.

We used the CHEC checklist to assess the quality of reporting of health economics studies (Evers 2005). We assessed whether the included studies described methods, assumptions, data and possible biases in a way that is transparent and is easily accessible to critical readers (Aluko 2020). In assessing the methodological quality of economic evaluations, we aimed to identify the key uncertainties in each study and assess the applicability and relevance of each economic evaluation to different settings.

Measures of treatment effect

We estimated the effect of the intervention on dichotomous outcomes using risk ratios, together with the appropriate associated 95% confidence interval. We used the number of patients with the event as the numerator and the number of participants randomised to the group as the denominator. For rate data (e.g. number of events in a period of time) we have used a rate ratio, which compares the rate of events in the two groups by dividing one by the other. The natural logarithms of the rate ratios were combined across studies using the generic inverse variance method.

We estimated the effect of the intervention on continuous outcomes by calculating the mean difference (MD), together with the appropriate associated 95% confidence interval. We used a standardised mean difference (SMD), with 95% confidence interval, to combine data from trials that measure the same outcome but use different scales. We standardised the data to their effect size by dividing the estimated mean difference by its standard deviation. We always back‐translated to an understandable unit to make it meaningful to the users of the review. If some studies reported endpoint data and others reported change‐from‐baseline data (with standard errors), we combined these in the meta‐analysis if the outcomes were reported using the same scale (Deeks 2020). We ensured that an increase in scores for continuous outcomes could be interpreted in the same way for each outcome. We explained the direction of effect to the reader, and reported where the directions were reversed if this was necessary. We calculated the MD or SMD based on the number of participants analysed at that time point. If the number of participants analysed is not presented for each time point, we used the number of participants randomised to each group at baseline and noted this in the table of included studies 'Notes' section.

For all included outcomes, we prepared a structured summary of effects that included the intervention effect estimate, its 95% confidence interval, P value and the method of statistical analysis used to calculate it.

Unit of analysis issues

We checked to see that analyses in the eligible studies were performed at the same level as the allocation to ensure that unit of analysis errors were avoided. Data from cluster‐randomised trials had to be appropriately adjusted for clustering when presenting the data at the individual patient level. If the data from cluster‐randomised trials were not adjusted correctly, we re‐analysed the results based on guidance provided in Chapter 23 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019). Adjusting for clustering required dividing the original sample size (and number of events in the case of dichotomous data) by the design effect, which was calculated from the average cluster size and the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC). Where the ICC was not reported, we imputed the most commonly reported value from studies, where it was reported.

Dealing with missing data

If data were missing, we contacted study investigators in order to verify key study characteristics and obtain missing outcome data where possible (e.g. when a study was identified as abstract only). For all outcomes, we analysed the data on an intention‐to‐treat basis. That is, we included all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and analysed data according to initial group allocation, irrespective of whether or not participants received, or complied with, the planned intervention. Where intention‐to‐treat analyses were not possible due to missing data, we conducted available case analysis; that is, we only included the number of participants in whom the outcome was measured in both the intervention and control groups.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Where a meta‐analysis of the study data was feasible, we used the I² statistic to assess heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 50% to 90%) or considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 75% to 100%) (Deeks 2020), we noted this in the text and explored this heterogeneity through the pre‐specified subgroup analyses (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). We used caution in interpreting meta‐analysis results with high levels of unexplained heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we were unable to contact study authors to obtain missing outcome data, or they could not provide it, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results. Where we identified more than 10 studies reporting on the same outcome, we generated funnel plots using Review Manager software (Review Manager 2020) and visually examined them for asymmetry, to explore possible reporting or publication biases (Higgins 2019; Sterne 2011).

For the economic evaluation, a common reporting bias is the non‐reporting of planned economic evaluations. Wherever possible, we followed up studies that planned to do an economic evaluation in the study protocol but had not yet reported or published these findings, in order to access these data.

Data synthesis

We combined study data in meta‐analyses only when it was meaningful to do so, i.e. if the interventions, participants, outcomes and the underlying question were similar enough for pooling to make sense. We carried out the statistical analysis using Review Manager software (Review Manager 2020). We used a random‐effects model to combine the data, as there is heterogeneity between studies attributable to the different settings, populations and interventions (for example, different models of care, with different usual care protocols, varying skills of the nursing staff, age and disease condition of ACF residents).

We assessed the combined effect of intervention using the standardised mean difference (SMD) for continuous outcomes and risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and analysed using the inverse variance and Mantel‐Haenszel methods, respectively (Deeks 2020). For cluster‐randomised trials, we either used the adjusted data as provided by the study authors, or we adjusted the unadjusted/raw data, using either the ICC provided by the study authors or a conventional ICC of 0.05 prior to the inclusion in meta‐analysis.

If trialists report medians and interquartile ranges, it may be because their data are not normally distributed. Where this was the case, we made a note of this and considered the implications of the skewed data on the study findings. If a study had multiple trial arms, we extracted and analysed data from the relevant arms. Where two comparisons (e.g. intervention A versus usual care and intervention B versus usual care) must be entered into the same meta‐analysis, we halved the control group to avoid double‐counting.

Study authors used different ways to present outcome data, both within and across studies. We presented the findings and the certainty of the evidence for all of the analyses. We selected one analysis per outcome as a primary analysis, based on the outcome with the most evidence (most number of studies). The primary analysis for each outcome is reported in the summary of findings table, with the findings of the other analyses incorporated into the 'Comments' section of the table. Only the primary analyses were subjected to subgroup and sensitivity analyses, where necessary.

There are currently no agreed‐upon methods for pooling combined estimates of cost‐effectiveness, extracted from multiple economic evaluations, using meta‐analysis or other quantitative synthesis methods. However, if comparable measures of resource use and costs were available from two or more studies undertaken in a similar setting for a common intervention and comparator, we pooled these using meta‐analysis.

We adjusted cost estimates collected from multiple studies to a common reference year and currency using a two‐step process. Firstly, we converted the reported currency to Australian dollars using the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) between the reported currency and the Australian dollar in the year for which each study reported costs had been estimated (https://data.oecd.org/conversion/purchasing-power-parities-ppp.htm). Secondly, we updated the converted cost estimates to 2021 cost values using the Australian Consumer Price Index for health expenditure (https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/price-indexes-and-inflation/monthly-consumer-price-index-indicator/). Where meta‐analyses of resource use or cost data were conducted, we included a structured summary in the 'Results' section to comment on the direction and magnitude of results and their precision. Where meta‐analyses could not be conducted, we provided a summary of the results of included economic evaluations in a table, supplemented by a structured summary description in the 'Results'.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where possible, we conducted subgroup analyses for the following factors.

Type of model according to relevant EPOC delivery arrangement categories, i.e. where care is provided; who provides care; co‐ordination of care.

Type of health care being provided, i.e. primary, secondary.

Age of the ACF patients (less than 80 years versus 80 years or more): increasing age is often associated with decreasing physical/psychological well‐being, so it is possible that different models are more or less effective in very old residents.

Type of condition being treated: it is possible that different models are more effective for different conditions (e.g. patients with dementia might respond differently to a particular model of care compared to patients with congestive heart failure).

Sensitivity analysis

Where possible, we performed the following sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our conclusions and explore their impact on effect sizes.

Restricting the analysis to studies with a low risk of bias.

Assessing the impact of timing of assessment: short‐term (up to 12 months; if multiple time points were available, we selected the closest to six months) and longer‐term (12 to 24 months; if multiple time points were available, we selected the closest to 18 months).

We conducted the review according to the published protocol and reported any deviations from it in the Differences between protocol and review section of the review.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created a summary of findings table for the main intervention comparison: any alternative model of care versus usual care. Due to the expected heterogeneity across interventions, we considered creating additional summary of findings tables to reflect findings based on different interventions with similar content (e.g. care provided by multidisciplinary teams or care provided via teleconsultations at a distance). However, due to the limited evidence available per EPOC intervention category, we felt that it would not be meaningful to create additional summary of findings tables. We had planned to split comparisons according to the characteristics of the control intervention if 'usual care' was considered substantially different across trials. Usual care was not well described in most studies, which did not allow further splitting of comparison groups in a meaningful way.

The following outcomes were included in the summary of findings table, together with the certainty of the evidence for each (findings of the additional analyses for each outcome were included in the comments section): proportion of residents with at least one emergency department (ED) visit; proportion of residents with at least one unplanned hospital admission; adverse events ‐ proportion of residents with a fall; adherence to clinical guideline‐recommended care ‐ proportion of residents receiving adequate antidepressant therapy; mean health‐related quality of life per resident; proportion of residents who died; and total costs of care. No other important outcomes emerged during the review process.

Using GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT), two of the review authors (PP, LN) independently, and in duplicate, assessed the certainty of the evidence (high, moderate, low or very low) using the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) (Guyatt 2008; Higgins 2019). We were guided by the methods and recommendations described in Chapter 14 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019), and the EPOC worksheets (EPOC 2015). We provided justification for our decisions using table footnotes and we inserted comments to aid readers' understanding of the findings, where necessary. These decisions were checked by all authors and any disagreements on certainty ratings were resolved by discussion.

If a study provided data on an outcome, but these data could not be included in the meta‐analyses, we added a comment to the summary of findings table, noting if the findings support or contradict the summary estimate of effect from the meta‐analyses. We used plain language statements to report these findings in the review (Cochrane Norway 2019).

In order to be consistent with our judgement, we used the following rules when deciding whether or not to downgrade for imprecision (Schünemann 2022):

If the CI includes no effect AND appreciable harm/benefit, we conclude there is serious imprecision. RR < 0.75 or RR > 1.25 are interpreted as appreciable harm or benefit.

If the CI does not include 'no effect', we calculate the sample size that would be needed for an adequately powered individual study. If the number of participants exceeds this number, precision is sufficient.

If the CI includes no effect and NO appreciable harm/benefit, we calculate the sample size that would be needed for an adequately powered individual study. If the number of participants exceeds this number, precision is sufficient.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

A PRISMA flow diagram of the screening and selection process is presented in Figure 2. The search identified 9372 records. After removal of duplicates, we screened 6412 records (6358 studies). We retrieved 184 studies for full‐text screening. There were 40 trials that met our inclusion criteria (Agar 2017; Arendts 2018; Bellantonio 2008; Boorsma 2011a; Boyd 2014; Brodaty 2003; Cavalieri 1993; Chapman 2007; Connolly 2015; Cordato 2018; Crotty 2004; Crotty 2019; De Luca 2016; Dy 2013; Forbat 2020; Grabowski 2014; Haines 2020; Harvey 2014; Kim 2020; Kolcu 2020; Kotynia‐English 2005; Kovach 2006; Leontjevas 2013; Lichtwarck 2018; Lin 2010; Lin 2014; Loeb 2005; Loeb 2006; Man 2020; McSweeney 2012; Neyens 2009; Pieper 2016; Rubenstein 1990; Rutten 2022; Stern 2014; Temkin‐Greener 2018; Uy 2008; Van den Block 2020; Wu 2010; Zwijsen 2014).

2.

Study flow diagram

We excluded 125 studies: 61 had not evaluated an alternative model of care (wrong intervention), 39 used ineligible study designs, 21 studies were conducted in a setting other than an ACF (wrong setting) and four had an ineligible study population (see Excluded studies). Five studies were labelled as awaiting classification; see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification (Bagaragaza 2021; Bath 2001; Palmer 2020; Sillies 2022; Umpierrez 2021).

We identified 14 ongoing trials; see Characteristics of ongoing studies (Brucken 2022; Choi 2020; Dantoine 2019; Kaasalainen 2019; Kapp 2022; Moore 2022; Muller 2020; Papaioannou 2021; Piau 2018; Sourdet 2018; Spichiger 2021; Sunner 2020; Tchalla 2019; Tesky 2019).

Included studies

A description of the 40 included trials (21,787 participants (Boyd 2014, Grabowski 2014 and Haines 2020 only reported number of beds; four studies reported staff outcomes, 5856 participants)) is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table. A brief description of the study design, population, intervention and comparator in the included studies is provided in Table 2 and below.

1. Brief description of characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Design | Population | Intervention | Comparator (usual care) |

| WHO PROVIDES CARE (staffing models) | ||||

|

Haines 2020 Australia |

Stepped‐wedge cRCT | Residents of ACFs, not further limited to a specific subgroup | GP co‐located in ACF | Residents seen by external GPs not directly linked with facility staff |

| WHO PROVIDES CARE (Role expansion or task shifting) | ||||

|

Arendts 2018 Australia |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs, not further limited to a specific subgroup | Nurse practitioners led care using best practice guide | Residents received usual care and were assigned to GPs who were responsible for their care. Neither NPs nor the resource folder of best practice guidelines were available. |

|

Kolcu 2020 Turkey |

RCT | Residents of ACFs with hypertension | A nurse‐led hypertension management programme | The participants in the control group received the routine care provided in their nursing home (clinical evaluation every 6 months, procurement and administration of anti‐hypertension medications, and blood pressure measurement twice a day and when patients reported feeling unwell) |

| WHERE CARE IS PROVIDED (Site of service delivery) | ||||

|

Man 2020 Australia |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs with visual impairment |

Residential ocular care (ROC) model The ROC model of eye care includes an on‐site eye examination by an optometrist with expertise in domiciliary and low vision care. Four intervention options were provided to help improve vision based on the individual participants’ eye history. These include: (1) refraction and spectacle provision; (2) cataract surgery; (3) referral to an ophthalmologist for medical and surgical treatments for conditions likely to cause loss of sight or ocular discomfort; and (4) low vision rehabilitation for untreatable eye disease. If a clinical need is identified, participants will be eligible to receive more than one intervention pathway (e.g. spectacles and low vision rehabilitation aids/services). For all pathways, transportation costs for initial consultations and for up to 2 follow‐up consultations (to either a public or private care provider) were funded by the study. |

Residents with visual impairment in the usual care group were referred for an evaluation to the eye care service associated with the facility or a practitioner of their choice |

|

Uy 2008 Australia |

RCT | Residents of ACFs recovering after hip fracture | Inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme | Residents were discharged back to the RACF soon after surgery for the hip fracture |

| COORDINATION OF CARE (Teams) | ||||

|

Boorsma 2011a the Netherlands |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs, not further limited to a specific subgroup | The multidisciplinary integrated care model | The GP was responsible for medical care and offered it on request. There was neither co‐ordination nor structured planning of care. Multidisciplinary meetings were mostly not attended by the family physicians. |

|

Boyd 2014 New Zealand |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs, not further limited to a specific subgroup | Geriatric nurse specialist (GNS)‐led care including quality improvement, staff education and multidisciplinary care (The Residential Aged Care Integration Program (RACIP)) | Comparison facilities did not receive GNS on‐site intervention |

|

Connolly 2015 New Zealand |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs, not further limited to a specific subgroup | GNS‐led care including quality improvement, staff education and multidisciplinary care (Aged Care Healthcare Utilization Study (ARCHUS)) | Residents in control facilities received usual District Health Boards support, which did not include any of the elements listed in the intervention description |

|

Bellantonio 2008 USA |

RCT | Residents of RACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Multidisciplinary team care | Usual clinical care consisted of a medical evaluation conducted by the resident’s primary care physician 30 days before move‐in or within 7 days of admission, as per facility policy. The content and subsequent frequency of medical evaluations was at the discretion of the primary care physician; no team approach. |

|

Brodaty 2003 Australia |

RCT | Residents of ACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Arm 1: Multidisciplinary psychogeriatric case management Arm 2: Multidisciplinary team assessment with resulting treatment plan provided to a GP |

Immediate feedback was provided if psychopathology that was a danger to the resident, e.g. suicidality, was uncovered |

|

Chapman 2007 USA |

RCT | Residents of ACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Multidisciplinary team care (Advanced Illness Care Teams (AICT) intervention) | Residents received all the services typically provided by the facility, including medication management and monitoring, ongoing nursing care, social‐recreational activities, pastoral care, occupational and physical therapies, and social work services |

|

Crotty 2004 Australia |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Multidisciplinary case conferencing | Not described |

|

Lin 2010 Taiwan |

RCT | Residents of ACFs, not further limited to a specific subgroup | A hospital‐based (outreach) multidisciplinary approach to improve nutritional status of RACF residents | In the control group, usual care, including a medical doctor, nurse and pharmacist, was adopted for each participant |

|

Leontjevas 2013 The Netherlands |

Stepped‐wedge cRCT | Residents of ACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Act in Case of Depression (AiD) Multidisciplinary care programme | When the units were not receiving the intervention, no specific information about AiD was provided to nursing‐home staff and residents. No structural approach to depression management was used: depression was assessed after indications of possible depression were reported by nursing staff, a resident or any other informant; teams did not use multidisciplinary pathways for depression treatment, which was provided ad hoc and was mainly in the form of drugs |

|

McSweeney 2012 Australia |

cRCT | Residents of RACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Multidisciplinary team care | Control RACFs participated in the assessment component of the study, but no advice was offered regarding the management of depression during the intervention phase |

|

Neyens 2009 the Netherlands |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Multifactorial fall prevention programme applied by a multidisciplinary team | Not described |

|

Temkin‐Greener 2018 USA |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs, not further limited to a specific subgroup | Palliative care through teamwork (IMPACTT) | Not described in the published report. Additional information provided by authors via email: “Usual care meant no active palliative care teams operating on site. While palliative care may be provided in US nursing homes, largely via a contractual relationship with hospice, on site palliative care teams do not exist” |

|

Zwijsen 2014 The Netherlands |

Stepped‐wedge cRCT | Residents of ACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Multidisciplinary team care | Not described |

|

Stern 2014 Canada |

Stepped‐wedge cRCT | Residents of ACFs with pressure ulcers | Enhanced Multidisciplinary Team (EMDT) care | Wound care within RACFs was typically provided by RNs, RPNs, personal support workers and nutritionists, who may or may not have had expertise in wound care. Access to other disciplines was available, typically on a reactive basis. |

|

Wu 2010 Taiwan |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs who are highly disabled | Multidisciplinary team care | Participants were provided usual nursing and personal care with some professional care (i.e. physician, physical therapist and dietitian visits) when necessary |

|

Crotty 2019 Australia |

RCT | Residents of ACFs recovering after hip fracture | In‐reach multidisciplinary rehabilitation | Participants continued treatments (which may include sessions of physiotherapy) according to usual practice in the RACF. The control group on all sites will receive orthogeriatric care in hospital and medical care from a general practitioner after discharge. |

| COORDINATION OF CARE (Discharge planning) | ||||

| Cordato 2018 Australia | RCT | Residents of ACFs discharged back to ACF after hospital admission | Regular Early Assessment Post‐Discharge (REAP) following acute hospitalisation protocol of co‐ordinated specialist geriatrician and nurse practitioner visits | Usual post‐discharge care administered by their usual general practitioner (or primary care physician) and nursing staff at their RACF |

|

Harvey 2014 Australia |

RCT | Residents of ACFs discharged back to ACF after hospital admission | Geriatrician‐led discharge from hospital to RACF (The Residential Care Intervention Program in the Elderly (RECIPE) | The usual care group was managed by the treating medical unit according to standard hospital protocols and received standard discharge planning, with follow‐up at the RACF by their primary care physician service |

| COORDINATION OF CARE (Case management) | ||||

|

Agar 2017 Australia |

cRCT | Residents of RACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Facilitated case conferencing with family, multidisciplinary nursing home staff and external health professionals (e.g. general practitioners (GPs)) | No staff education, training or support was provided. No restrictions were placed on nursing homes’ education programme, or approach to care planning and decision‐making. |

|

Forbat 2020 Australia |

Stepped‐wedge cRCT | Residents of ACFs with short prognosis and high symptom burden | Specialist Palliative Care Needs Rounds (triage meetings, case‐based education, case conferences) | Usual care involves access to the specialist palliative care team’s two nurses who work in residential aged care. No embedded ‘triage’ element in the form of the needs rounds and limited case‐based education for staff. Essentially, the usual care is reactive, whereas the trial intervention is proactive and anticipatory. |

|

Lichtwarck 2018 Norway |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Intervention arm: Targeted Interdisciplinary Model for Evaluation and Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms (TIME) | Brief education‐only intervention. The staff in both the intervention and control nursing homes were offered a 2‐hour lecture covering dementia and NPS. |

|

Van den Block 2020 Belgium, England, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Switzerland |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs, not further limited to a specific subgroup | Palliative Care for Older People (PACE) Steps to Success | Care as usual (no further details provided) |

| COORDINATION OF CARE (Care pathway) | ||||

|

Kotynia‐English 2005 Australia |

RCT | Residents of ACFs upon admission to the facility | Early psychiatric intervention (screening at admission followed by referral (in case of positive screening) to a multidisciplinary psychogeriatric team) | Subjects in the control group received standard care (i.e. positive screening did not automatically trigger a referral) |

|

Kovach 2006 USA |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs with mental health conditions or behavioural problems | Serial Trial Intervention (STI): clinical protocol designed to address the problems of pain and other unmet needs | The control group nurses received common misconceptions about ageing, the physical effects of ageing, reversible and irreversible causes of dementia, stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and various approaches to treating behaviours and physical conditions associated with dementia. Videotapes were shown on management of common behaviours associated with dementia. |

|

Loeb 2005 Canada |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs, not further limited to a specific subgroup | Diagnostic and treatment algorithm for urinary tract infections using a multifaceted approach | Nurses and physicians in control nursing homes were notified about the study and were informed about how data were going to be collected |

|

Loeb 2006 Canada |

cRCT | Residents of ACFs with pneumonia or lower respiratory tract infections | Clinical Pathway to assess whether patient needs to be transferred to hospital | Care for residents allocated to usual care treatment was left up to the resident’s physician (the physician and RACF staff made treatment decisions, including antimicrobial use and transfer to hospital) |

|

Pieper 2016 the Netherlands |