Highlights

-

•

WNV 3′ UTR recruits the 40S ribosomal subunit with high affinity and specificity.

-

•

3′ UTR RNA structural elements regulate viral translation by recruitment of the 40S.

-

•

The SL-III element and the double dumbbell domain constitute 40S binding sites.

-

•

40S acts as a bridge to allow cross-talk between the genomic ends in WNV translation.

-

•

Interfering with the 40S binding by the WNV 3′ UTR affects translation efficiency.

Keywords: WNV RNA, WNV translation control, RNA-40S interaction, WNV 3′ UTR, RNA folding, Flavivirus

Abstract

Flaviviral RNA genomes are composed of discrete RNA structural units arranged in an ordered fashion and grouped into complex folded domains that regulate essential viral functions, e.g. replication and translation. This is achieved by adjusting the overall structure of the RNA genome via the establishment of inter- and intramolecular interactions. Translation regulation is likely the main process controlling flaviviral gene expression. Although the genomic 3′ UTR is a key player in this regulation, little is known about the molecular mechanisms underlying this role. The present work provides evidence for the specific recruitment of the 40S ribosomal subunit by the 3′ UTR of the West Nile virus RNA genome, showing that the joint action of both genomic ends contributes the positioning of the 40S subunit at the 5′ end. The combination of structural mapping techniques revealed specific conformational requirements at the 3′ UTR for 40S binding, involving the highly conserved SL-III, 5′DB, 3′DB and 3′SL elements, all involved in the translation regulation. These results point to the 40S subunit as a bridge to ensure cross-talk between both genomic ends during viral translation and support a link between 40S recruitment by the 3′ UTR and translation control.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Viral RNA genomes are compact entities that retain all the information to ensure the successful infection. Essential information is stored in discrete and highly conserved structural RNA elements that establish complex networks of intra- and intermolecular interactions, the so-called interactome, which is critical to regulate the different steps of the viral cycle (Nicholson and White, 2014). During early infection, single-stranded positive RNA viruses make use of the translational cellular machinery to synthesize viral proteins (Firth and Brierley, 2012; Reineke and Lloyd, 2011). The sequestration and management of this machinery is accomplished by highly structured RNA elements especially accumulated at both ends of the viral RNA genome, but also dispersed throughout it (Firth and Brierley, 2012; Trainor and Shcherbik, 2021). In flaviviruses, these elements coordinate a translation mechanism that differs from the canonical cap-dependent one, thus contributing to the evasion of the cellular defense systems by the virus (Jaafar and Kieft, 2019; Sorokin et al., 2021). Following several rounds of translation, the process must shut down to activate replication, releasing the viral RNA genome that will function as template for replication. Therefore, the processes of protein and RNA synthesis, as well as the transition between them, must be finely regulated to ensure the progression of the infection. The mechanism that switches between both stages is still unknown.

West Nile virus (WNV), belonging to the family Flaviviridae, is a flavivirus with a (+) single-stranded RNA genome of about 11,000 nt-long, which encodes a single open reading frame (ORF) flanked by untranslated regions (5′ and 3′ UTRs, Fig. 1). The RNA genome bears a cap-1 structure at the 5′ terminus and lacks polyA tail at its 3′ end. The 5′ end possesses a widely conserved secondary structure among different isolates that operates as scaffold for the proper recruitment and positioning of the translational machinery (Liu and Qin, 2020; Ramos-Lorente et al., 2021). Specifically, the cHP element at the 5′ end promotes the stalling of the ribosome to favor the selection of the precise translation start codon (Clyde and Harris, 2006). In addition to structural conservation extending beyond the translation initiation codon at the 5′ end of the ORF, conserved sequence motifs have also been identified: the 5′ upstream of AUG region (5′UAR), the 5′ downstream of AUG region (5′DAR) I and II and the 5′ conserved/cyclization (5′CYC) sequence (Fig. 1) (Liu and Qin, 2020; Ramos-Lorente et al., 2021). These sequence motifs have been shown to be involved in the viral genome circularization via direct RNA-RNA interactions with their complementary sequences at the 3′ UTR, in a process called cyclization that is required for viral replication (Friebe and Harris, 2010; Villordo and Gamarnik, 2009).

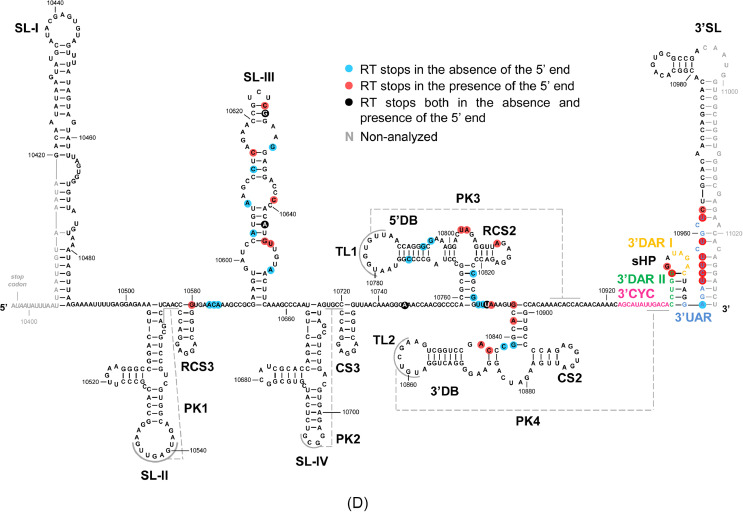

Fig. 1.

Secondary structure model proposed for the 5′ and the 3′ ends of the WNV genome. The 5′ end, comprising the 5′ UTR plus the cHP element and the 5′CYC sequence, which are involved in viral translation and replication, are included. The 3′ UTR is organized into three different domains: domain I, composed by the SL-I to SL-IV elements plus the repeated sequences RCS3 and CS3; domain II, including double dumbbell; and the highly conserved domain III containing the sHP and the 3′SL elements. Pseudoknot structures PK1-PK4 are depicted by dotted lines. Cyclization sequences UAR, DAR I, DAR II and CYC, located at the 5′ and the 3′ ends of the viral genome, are indicated by blue, yellow, green and pink solid lines, respectively. Translation start and stop codons are indicated by arrows. ORF, open reading frame.

At the 3′ end of the WNV genome, the 3′ UTR is a partially conserved sequence of ∼625 nt-long ending in a CUOH dinucleotide. This region can be divided in three domains (I, II and III; Fig. 1) showing different sequence conservation rate but a well-defined secondary structure (Goertz et al., 2018). The WNV 3′ UTR is featured by the presence of structural elements that are organized as duplicated cassettes. These duplications have been related to the acquisition of new functionalities by the viral genome as well as the adaptation of the virus to different hosts (de Borba et al., 2019; Pallares et al., 2020; Villordo et al., 2015). It is also worth mentioning the presence of four pseudoknot elements, PK1-PK4, located throughout the 3′ UTR, which are required for translation, replication and infectivity (Fig. 1) (Funk et al., 2010; Manzano et al., 2011; Sztuba-Solinska et al., 2013; Xing et al., 2021). The highly conserved sHP and 3′SL elements, located at the 3′-terminal end, contain the 3′ upstream of AUG region (3′UAR), 3′ downstream of AUG region (3′DAR) I and II and 3′ conserved/cyclization (3′CYC) sequence motifs, which interact with their corresponding partners in the 5′ UTR to achieve the cyclization of the viral genome (Alvarez et al., 2005, Alvarez et al., 2008; Friebe and Harris, 2010; Hahn et al., 1987; Khromykh et al., 2001; Lodeiro et al., 2009; Mandl et al., 1993). Cyclization is required for the recruitment of the NS5 polymerase during the initiation of the minus strand RNA synthesis (Davis et al., 2013; Dong et al., 2008; Filomatori et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2016; Meyer et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2008), while it interferes with efficient translation initiation by affecting the folding of those structural elements required for the proper ribosome scanning, e.g., cHP (Funk et al., 2010; Manzano et al., 2011; Sztuba-Solinska et al., 2013; Xing et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the acquisition of a circular conformation by cellular eukaryotic mRNAs is a mainstream requisite for protein synthesis initiation (Kim et al., 2023). Therefore, if a circular genomic conformation was required for translation in WNV, alternative mechanisms to the establishment of direct RNA-RNA interactions should trigger the acquisition of such conformation.

It is well accepted that the 3′ UTR stimulates viral translation. Recent findings have demonstrated that the WNV 3′ UTR exert a regulatory effect on cap-dependent protein synthesis, bearing elements that function in opposite ways, thus yielding a multifactorial control of viral translation (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022). In addition, it has been proposed that, besides a cap-dependent translation initiation mechanism, some flaviviruses could use a cap-independent mechanism to initiate the synthesis of viral proteins under specific conditions (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022; Edgil et al., 2006; Song et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). This process is also regulated by the 3′ UTR in WNV (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022), pointing to this region as a key element also in the control of viral protein synthesis. However, the molecular mechanism responsible for this phenomenon is unknown.

Many single stranded positive RNA viruses take advantage of the genomic structural elements to recruit the translational machinery and use it as a regulatory mechanism of translation (Kean, 2003). Examples are the Turnip crinkle virus (TCV) and Barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV), both of them belonging to the family Tombusviridae; or hepatitis C virus (HCV), which is closely related to WNV and belongs to the family Flaviviridae. The genome of tombusviruses is uncapped and lacks polyA tail. Instead of polyA, TCV bears a cap-independent translation element in the 3′ UTR (3′-CITE). 3′-CITEs are structurally diverse RNA elements located at the 3′ UTR of viral genomes that recruit components of the translation machinery, which are then delivered to the genomic 5′ UTR promoting the 5′−3′ communication, to initiate viral translation (Jaafar and Kieft, 2019; Truniger et al., 2017). In TCV, the 3′-CITE interacts with the P site of 80S ribosome through the 60S ribosomal subunit, thereby increasing translation efficiency (Stupina et al., 2008; 2011). On the other hand, BYDV has a 3′ translation element (3′ BTE) that is required for efficient translation initiation at the 5′ end of the viral RNA by the recruitment of the 40S subunit in the presence of eIF4 complex factors (Sharma et al., 2015). Finally, the HCV RNA genome recruits the 40S ribosomal subunit at two different sites within its 3′ end: the 3′ UTR and the cis-acting replicating element (CRE, located at the 3′ end of the ORF), promoting opposite effects on the regulation of viral translation (Bai et al., 2013; Rios-Marco et al., 2016; Romero-López et al., 2018).

This manuscript provides evidence of the direct recruitment of the 40S ribosomal subunit by the WNV 3′ UTR. This recruitment involves the participation of ribosomal proteins. Results of structural mapping and functional assays also demonstrate the existence of a communication between the 5′ and the 3′ UTRs, which seems to be mediated by the 40S subunit. This supports a model in which the 40S binding at the 3′ UTR could be a molecular mechanism controlling translation efficiency in WNV, and postulating the transfer of the 40S subunit from the 3′ UTR to the 5′ end of the viral genome as part of the flaviviral translation regulation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. DNA templates and RNA synthesis

The sequences used in this study derive from the NY99-flamingo382–99 strain (Lanciotti et al., 1999) with the modifications reported (GeneBank access AF196835) (Martin-Acebes and Saiz, 2011).

DNA template encoding for the WNV 3′ UTR was obtained as described (Romero-López et al., 2023). DNA encoding deletion mutants 3′WNV_10,400–10,900, 3′WNV_10,828–11,029, 3′WNV_10,742–10,950, 3′WNV_10,742–11,029 and 3′WNV_10,583–11,029 were obtained by PCR amplification from the plasmid pGLWNV (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022).

Plasmid pGLWNV was linearized with HindIII, BamHI or XbaI to generate the templates required for the synthesis of the 5′WNV, m7G-WNV and m7G-WNV_Δ3’UTR RNA constructs, respectively. Plasmids pGLWNV-d5’DB (previously referred as dpK3) (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022) and pGLWNV_dSLIII were digested with the restriction enzyme BamHI to generate the corresponding templates for the synthesis of m7G-WNV-d5’DB and m7G-WNV-dSLIII (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022), respectively.

DNA plasmids pGLWNV_d3’DB and pGLWNV_d3’PK3 were generated by site-directed mutagenesis from the parental construct pGLWNV, using appropriate pair of primers and the Phusion Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The pGLWNV_d3’DB DNA encompasses the same genetic organization than pGLWNV but it lacks the 3′DB element in the WNV 3′ UTR. The pGLWNV_d3’PK3 also derives from pGLWNV plasmid but includes a deletion in the WNV nucleotide positions 10,908–10,925, thus impeding the formation of the PK3 structure. Both plasmids were linearized with the endonuclease BamHI to generate the templates for the synthesis of the m7G-WNV-d3’DB and m7G-WNV-d3’PK3.

DNA templates encoding the m7G-FLuc-WNV and m7G-WNV_d3’SL RNA were obtained by PCR amplification from the pGLWNV with the appropriate pair of oligonucleotides.

DNA templates for the RNAs m7G-RLuc and RNA-100 were obtained as described (Romero-López et al., 2007; 2018).

RNAs WNV 3′ UTR, 3′WNV_10,400–10,900, 3′WNV_10,828–11,029, 3′WNV_10,742–10,950, 3′WNV_10,742–11,029, 3′WNV_10,583–11,029, 5′WNV, m7G-5′WNV and RNA-100 were synthesized using the T7 RNA polymerase ver.2.0 (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), following the manufacturer's instructions. On the other hand, RNAs m7G-WNV, m7G-WNV_Δ3’UTR, m7G-WNV-dSLIII, m7G-WNV-d5’DB, m7G-WNV-d3’DB, m7G-WNV-d3’PK3, m7G-WNV_d3’SL, m7G-FLuc-WNV and m7G-RLuc were obtained by in vitro transcription with the HighYield T7 RNA Synthesis kit (Jena Bioscience, Jena, Germany). The 5′ cap (m7G) was incorporated as described (Romero-López and Berzal-Herranz, 2012). RNAs were purified, quantified and their quality was assessed as reported elsewhere (Romero-López and Berzal-Herranz, 2009; 2012).

The sequences of all the primers used in this work are available upon request.

2.2. Cell culture

African green monkey kidney cells (Vero) were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 5 % heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco® by LifeTechnologies™, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), 2 mM l-Glutamine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma) at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere.

2.3. Purification of 40S ribosomal subunits

S10 fractions from Vero cells were prepared as previously described (Rios-Marco et al., 2016), with slight modifications. Briefly, ∼3 × 109 cells with 100 % confluence were pelleted and washed with 10 vol of isotonic buffer (35 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.6; 146 mM NaCl; 11 mM glucose) and centrifuged for 5 min at 1000 xg. Lysis was performed by incubating cells at 4 °C for 20 min with 1.5 vol of pre-cooled hypotonic buffer (20 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.6; 10 mM KCl; 1.5 mM Mg(Ac)2; 1 mM DTT) supplemented with cOmplete™ protease inhibitor (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Cell lysate was homogenized in a cooled glass Dounce homogenizer (25 strokes) and equilibrated with 0.2 vol of S10 buffer (100 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.6; 600 mM KAc; 20 mM Mg(Ac)2; 25 mM DTT and cOmplete™ protease inhibitor). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 xg for 10 min and the amount of protein was quantified by measuring A280.

The 40S ribosomal subunits were isolated from Vero S10 cell lysates, essentially as described (Pestova et al., 1996). S10 cell lysates were layered onto 3 ml of a 1 M sucrose cushion in buffer A (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.6; 2 mM DTT; 6 mM MgCl2; 0.5 M KCl) and ultracentrifuged at 40,000 rpm and 4 °C in a Beckman 70.1 Ti rotor for 4 h. The pellet containing the polysomes was resuspended in buffer B (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.6; 2 mM DTT; 6 mM MgCl2; 150 mM KCl) at a final concentration of 50–150 A260 units, and then incubated with 4 mM puromycin to release the ribosomal subunits. Reactions proceeded for 10 min at 4 °C followed by incubation during 30 min at 37 °C. A concentration of 0.5 M KCl was added in order to enrich the sample in ribosomes lacking eIF3. Ribosomal subunits were passed through a continuous 10–30 % linear sucrose gradient in buffer A by ultracentrifugation at 28,000 rpm and 4 °C for 18 h in a Beckman SW40 rotor device. Sucrose gradients were prepared using the BioComp Gradient Master 108 (BioComp Instruments, Fredericton, NB, Canada), following manufacturer's instructions. Fractions of 500 µl were collected from the top of the gradient. The presence of rRNA was checked by denaturing formaldehyde agarose gel electrophoresis. Fractions containing the isolated 40S subunit were concentrated using Amicon® Ultra-2 Centrifugal Filter Unit 30 kDa MWCO (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The concentration of the resulting suspension was determined by UV spectrophotometry (1 A260 unit = 30 pmol/ml).

2.4. In vitro binding assays

In vitro experiments to calculate the biochemical constants of the binding reaction between the WNV 3′ UTR and the 40S ribosomal subunit were performed as previously described (Romero-López et al., 2018). Briefly, trace amounts of the 32P-internally radiolabeled 3′ UTR was denatured for 2 min at 95 °C and renatured for 15 min at 4 °C. Binding reactions were initiated by the addition of increasing concentrations of the purified 40S subunit (0–400 nM). Reactions proceeded in SHAPE buffer (100 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4; 100 mM NaCl; 1 mM MgCl2) for 30 min at 37 °C. RNA-40S complexes were then fractioned by differential retention filter assay. For that purpose, reactions were diluted up to a volume of 100 µl with SHAPE buffer and loaded onto a top 0.45 µm nitrocellulose filter (GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA), which retains the ribonucleoprotein complexes, overlying a nylon membrane (GE HealthCare), which collects free RNA. Filters were pre-soaked in SHAPE buffer and assembled in a dot-blot apparatus to facilitate the passage of the reactions under vacuum. Both filters were air dried and exposed on Phosphor screens overnight. These were then scanned in a Storm 820 Phosphor Imager (GE HealthCare). The recovered signal was quantified using Image Quant 5.2© software (GE Healthcare). Data were fitted to a second order, sigmoidal equation using SigmaPlot for Windows Version 14.5 software, according to: y = (a·xb)/(cb+xb), where y is the ratio of complexed RNA, x is the concentration of the ligand (in this case, the 40S subunit), b is the Hill coefficient that provides a quantitative measurement of the ligand binding cooperativity and c is the half-saturation constant, which can be assumed as the Kd (dissociation constant) under the experimental conditions set. Additionally, data were fitted to a two-sites binding curve according to the equation y = ((Bmax1)/(Kd1 + x)) + ((Bmax2)/(Kd2 + x)), where y is the ratio of complexed RNA, Bmaxn is the maximum yield of the reaction at each site, x is the concentration of 40S subunit and Kdn the concentration of 40S required to achieve the maximum complex formation.

Competition binding assays were performed under similar conditions to those described above. Briefly, the 32P-internally labeled 3′ UTR was complexed with a 30-fold molar excess of the 40S ribosomal subunit as noted. The complex was challenged with increasing concentrations of the unlabeled transcripts WNV 3′ UTR, cap-5′WNV, 5′WNV and RNA-100 (0–1 µM) and the reactions were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Ribonucleoprotein complexes were separated from the free RNA, analyzed and quantified as noted above.

2.5. Identification of ribosomal proteins that interact with the WNV 3′ UTR by UV cross-linking and label transfer

A concentration of 5 nM of the previously denatured 32P-labeled 3′ UTR RNA (see above) was incubated with a 50-fold excess of purified 40S ribosomal subunit in cross-linking buffer (100 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.6; 10 mM DTT; 3 mM MgCl2; 400 mM KCl; 50 ng/µl tRNA; 5 % glycerol; 2 U/µl Invitrogen™ Ambion™ ANTI-RNase (Waltham, MA, USA)) for 30 min at 37 °C. Ribonucleoprotein complexes were UV cross-linked by irradiation at 365 nm during 15 min, using a CL-1000 ultraviolet cross-linker (Analytik Jena GmbH, Jena, Germany). Reactions were kept in a cooled metal block to avoid overheating. Potential RNA-protein interactions were verified by treating the cross-linked complexes with 2 µg/µl proteinase K in 0.5 % SDS, during 30 min at 65 °C. Reaction products were fractionated by differential retention filter assay. Filters were dried, exposed, scanned and quantified as described above.

To identify those ribosomal proteins involved in the interaction with the WNV 3′ UTR, 10 nM of the 32P-internally radiolabeled transcript WNV 3′ UTR were incubated with a 30-fold molar excess of the 40S subunit in cross-linking buffer for 30 min at 37 °C. The resulting complexes were UV cross-linked as previously described. Reactions were treated with 1 µg/µl RNase A for 15 min at 37 °C and loaded on a 12.5 % SDS-PAGE gel. Gel slices containing the labeled products, corresponding to the 3′ UTR-protein interaction, were cut out and digested with trypsin overnight for further analysis by mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) as previously described (Romero-López et al., 2018).

2.6. Differential shape (SHAPE-dif) analysis

SHAPE-dif analysis (Gherghe et al., 2008) of the WNV 3′ UTR RNA was performed with N-methylisatoic anhydride (NMIA) and 1-methyl-6-nitroisatoic anhydride (1M6) as described (Romero-López et al., 2017; 2018). Briefly, 6.5 pmol of the WNV 3′ UTR transcript were denatured as described above and incubated during 15 min at 37 °C with 560 nM of the 40S subunit in SHAPE buffer. Chemical probing was then performed with the addition of 6 mM of NMIA or 16 mM of 1M6. Reactions proceeded for 30 or 5 min at 37 °C, respectively. Control reactions with the probe solvent DMSO were performed in parallel. Chemical modifications were stopped by the addition of cold 0.3 M NaOAc, pH 5.2. RNAs were precipitated with ethanol and subjected to reverse transcription to identify the modified positions. For that purpose, 1.5 pmol of the 5′ fluorescently labeled as3’WNV oligonucleotide, which hybridizes at the very 3′ end of the RNA 3′ UTR, was used as primer for the cDNA synthesis with SuperScript™ III (Invitrogen). RNA sequencing reactions were also performed with 6.5 pmol of WNV 3′ UTR and 3 pmol of the 5′ fluorescently labeled primer in the presence of 1.5 nM ddCTP and ddTTP. The NED-5′ labeled as3’WNV oligonucleotide was used to detect both control and treated reactions, while sequencing ladders were carried out with 6-FAM and VIC fluorophores. The resulting cDNAs were resolved by capillary electrophoresis and the electropherograms were analyzed by using the QuShape software (Karabiber et al., 2013). Relative reactivity values and differential SHAPE profiles were obtained as previously described (Karabiber et al., 2013; Romero-López et al., 2014).

2.7. 2′‑hydroxyl molecular interference (HMX) assays

HMX assays were performed essentially as described (Romero-López et al., 2018). Briefly, 5 pmol of the WNV 3′ UTR RNA were treated with 5 mM NMIA in 100 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.4, using a final volume of 20 µl, for 3 min at 95 °C. Samples were snap cooled on ice for 2 min and the chemical probing was repeated twice. The evaporated volume was replenished after each round of treatment. Finally, NMIA reactions were stopped on ice by the addition of 0.3 M NaOAc, pH 5.2, followed by ethanol precipitation. RNA was washed three times, dried under vacuum conditions and quantified by measuring A260. Binding reactions were performed by incubating 2.5 pmol of the modified 3′ UTR RNA with a three-fold molar excess of the 40S subunit in SHAPE buffer, during 30 min at 37 °C. Ribonucleoprotein complexes were separated from free RNA by differential retention filter assay, as noted above. Dot slices were trimmed from the filters and the RNA was recovered in elution buffer (20 mM NH4Ac; 0.1 % (w/v) SDS; 17 mM EDTA) and phenol extracted followed by ethanol precipitation. Modified positions were detected by reverse transcription as described above. NMIA reactivity at each nucleotide position was determined with QuShape software (Karabiber et al., 2013). Normalized reactivity values from, at least, three independent experiments, were used to calculate significant variations in relative reactivity, both in the free RNA and in the RNA-40S complexes, by applying a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test.

2.8. Primer extension assays

Primer extension assays were performed as described (Romero-López et al., 2018). Briefly, 0.2 pmol of the RNA under study were denatured as noted and incubated with 1-, 5-, 25- or 70-fold excess of purified 40S ribosomal subunit in SHAPE buffer for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, reverse transcription was accomplished with ∼100 counts per minute (CPS) of the 32P-5′ end labeled oligonucleotide using Superscript™ III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's instructions. The extension products were resolved by high-resolution denaturing polyacrylamide gel (6 %) electrophoresis. RNA sequencing reactions with the four ddNTPs were run in parallel. Gels were dried, exposed on Phosphor screens and these were scanned as noted above. The mean intensity of each cDNA product was quantified using Image Quant 5.2© software (GE Healthcare). The +40S/−40S ratio was calculated for each product and used to obtain the median and the quartile 3 value (Q3). Those ratios exceeding the Q3 were selected as relevant RT stops.

2.9. Translation assays and luciferase measurements

Vero cell transfection was performed essentially as described (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022). Briefly, 24 h before transfection, 60,000 cells per well were seeded on a 24-well plate to reach 80 % confluency. A mixture containing 1.5 µg of the transcript of interest, 0.30 µg of the m7G-RLuc RNA (for well-to-well normalization), 100 µl of Opti-MEM® (Gibco® by LifeTechnologies™) and 2 µl of transfection reagent (TransFectin™; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) were added to the culture. At 4 h post-transfection, cells were lysed and firefly (FLuc) and Renilla (RLuc) luciferase activities were measured using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer's instructions. Relative translation efficiency was calculated from the FLuc/RLuc ratio and then referred to that obtained for the m7G-WNV RNA.

2.10. RNA stability assays

Intracellular stability of the RNA constructs under study was evaluated by RT-qPCR. Vero cells were transfected as described above with the indicated RNA constructs. At 4 h post-transfection, the culture medium was removed and the cells were washed with 1X PBS. Total RNA was then extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total amount of 150 ng of DNase I-treated RNA was reverse transcribed with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) using random hexamers at a final concentration of 10 µM. Briefly, random primers were hybridized to total RNA by heating at 95 °C during 2 min and slow cooling to 16 °C. Then, reverse transcriptase was added to a final concentration of 1.5 U/µl to initiate the cDNA synthesis in the presence of 0.8 mM of dNTPs and the buffer supplied by the manufacturer. Reaction proceeded for 30 min at 16 °C and subsequent heating at 42 °C during 30 min for a fast extension. Reverse transcriptase was inactivated at 85 °C during 5 min. A fraction of 3/20 of the RT reaction was used for qPCR with the TB Green® Premix Ex Taq (Takara). WNV cDNA was amplified using the primers qFLuc F and qFLuc R over 40 cycles with the following temperature conditions: 5 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C. An initial denaturation step (30 s at 95 °C) was included to activate the enzyme mix. Normalization was accomplished by RT-qPCR of the abl mRNA, using specific primers (Barroso-delJesus et al., 2011) for the amplification step. PCR reactions were performed in triplicate using a CFX96™ device (Bio-Rad), and the mean relative expression level was calculated with the CFX Manager™ Software (Bio-Rad).

2.11. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments, unless indicated. Data points were compared using the unpaired two-tailed Mann-Whitney test (Lehmann and D'Abrera, 2006). Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. The 3′ UTR of WNV directly recruits the 40S ribosomal subunit

To test whether the recruitment of the 40S ribosomal subunit could be a molecular mechanism underlying the 3′ UTR mediated translation regulation, in vitro binding assays of the 40S subunit to the WNV 3′ UTR RNA were performed. Briefly, trace amounts of the 32P-internally labeled WNV 3′ UTR transcript, which encompasses the full-length 3′ UTR of WNV (nucleotides 10,400–11,029) (Romero-López et al., 2023), were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified 40S subunit. The resulting complexes were separated by differential retention filter assays, as it has been widely used for this purpose (Angulo et al., 2016; Bai et al., 2013; Bhattacharyya et al., 2015; Deforges et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2013; Tallet-Lopez et al., 2003).

A dose-dependent complex was detected (Fig. 2A), demonstrating the existence of a direct interaction between the WNV 3′ UTR and the 40S ribosomal subunit without additional factors requirements. Data were fitted to a sigmoidal equation, with a Hill coefficient of 0.476 ± 0.101 (Fig. 2A and supplementary Table 1). This result suggests the existence of negative cooperativity, which cannot be distinguished from ligand binding to multiple independent sites with different affinity (Martini and Habeck, 2015; Sevlever et al., 2020). Interestingly, fitting the data to a sigmoid curve with two binding sites rendered Kd values in the low nM range (Kd1 = 0.231 ± 0.241 nM and Kd2 = 28.832 ± 8.094 nM). Kd values in the low nM range (1.8 ± 0.2 nM) have also been reported for the specific binding of the 40S ribosomal subunit to the HCV 3′ UTR (Bai et al., 2013), which supports the specific binding of 40S to the WNV 3′ UTR.

Fig. 2.

The WNV 3′ UTR binds the 40S ribosomal subunit in the absence of any other factor in a specific manner. (A) The 32P-internally radiolabeled transcript WNV 3′ UTR was incubated with increasing concentrations (0–400 nM) of the purified 40S ribosomal subunit. Ribonucleoprotein complexes were separated from the free RNA by differential retention filter assays and quantified. The image shows a representative blot of these assays. Data represent the mean of three independent experiments ± standard deviation. (B) Competition assays of the WNV 3′ UTR-40S complex challenged with increasing amounts of the unlabeled WNV 3′ UTR transcript, both capped or uncapped 5′WNV, as well as a non-related RNA, RNA-100. Data are the mean of three independent experiments ± standard deviation. Statistical significant differences (p < 0.05) in binding competition at the maximum competitor concentration tested, compared to the 3′ UTR-40S binding reaction in the absence of competitor RNA were calculated by applying a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

To evaluate the specificity of the interaction, the binding reaction of the WNV 3′ UTR to the 40S subunit under subsaturating conditions was challenged with increasing concentrations of the unlabeled WNV 3′ UTR transcript or with a non-related RNA, RNA-100 – a 100 nt-long transcript corresponding to the multiple cloning site of the pBS SK plasmid (see Materials and Methods section; Fig. 2B), which binds 40S at low efficiency (less than 5 %) in the low µM range (Romero-López et al., 2018). Importantly, the radiolabeled complex WNV 3′ UTR-40S was competed out in the presence of increasing concentrations of the unlabeled WNV 3′ UTR, while the negative control RNA-100 showed a low competition at the highest concentration tested (Fig. 2B), which can be explained by a non-specific binding of RNA-100 to the 40S subunit.

In addition, the radiolabeled 3′ UTR-40S complex formed at subsaturating conditions was challenged with increasing concentrations of the WNV 5′ end transcript, with cap (m7G-5′WNV) or without cap (5′WNV). This transcript bears the first 156 nt of the WNV genome and therefore includes the whole 5′ UTR plus the cHP element. Interestingly, the 5′WNV RNA significantly (p < 0.05) competed with the 3′ UTR-40S binding, though to a low extent (∼ 20 %) (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the yield of this competition was not significantly different to that shown by the non-related RNA-100 (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the efficient recruitment of the 40S at the 5′ UTR requires additional factors. It is remarkable that no differences in competition ability were detected for the capped or uncapped 5′ transcripts (Fig. 2B). These results point that the direct recruitment of the 40S subunit by the WNV 5′ end would not be the preferential mechanism for cap-independent translation initiation.

Taken together, these results support the specific interaction between the WNV 3′ UTR and the 40S subunit. This interaction even shows a higher affinity than that exhibited by the 5′ end of the viral genome.

3.2. The interaction between the WNV 3′ UTR and the 40S ribosomal subunit involves ribosomal proteins

In an attempt to investigate whether ribosomal proteins are involved in the WNV 3′ UTR-40S interaction as previously described for the 3′ UTR of HCV, the 32P-internally labeled 3′ UTR RNA was incubated with purified 40S ribosomal subunit under subsaturating conditions and subjected to UV cross-linking. The resulting complexes were fractionated by differential retention filter assays. As control, binding reactions were also treated with proteinase K. Only a 14 % of the total radioactive signal was detected after UV cross-linking followed by proteinase K treatment compared to that observed for the 3′ UTR-40S untreated complex (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 3 and 4), which confirms that the signal detected in the absence of proteinase K treatment correspond to the formation of a ribonucleoprotein complex between the WNV 3′ UTR of WNV and the 40S subunit. A proteomic strategy was next accomplished. The 32P-internally labeled 3′ UTR transcript was incubated with a molar excess of the 40S subunit and subjected to UV cross-linking. Then, RNA was removed by RNase A treatment and the reaction products were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3B). Proteins of different sizes were evidenced by label transfer, suggesting their direct interaction with the WNV 3′ UTR. The equivalent assay with unlabeled RNA was run in parallel to isolate the corresponding unlabeled protein products, which were subjected to liquid chromatography coupled to MS/MS analysis (LC-MS/MS) to identify the interacting proteins. The Mascot search engine reported five major candidate proteins: RPS2, RPS3, RPS8, RPS9 and RPS11 (Fig. 3C). All of them are related to the organization of the mRNA entry and exit channels and the constitution of the translation initiation complexes (Table 1), supporting the specificity of the interaction. It is also noteworthy that RPS2 and RPS3 have also been involved in the specific binding of the HCV 3′ UTR-40S (Bai et al., 2013).

Fig. 3.

Ribosomal proteins mediate the interaction between the WNV 3′ UTR and the 40S subunit. (A) The 32P-internally radiolabeled RNA WNV 3′ UTR was incubated with a molar excess of the 40S subunit and subjected to UV cross-linking to achieve the formation of a stable complex, which resulted sensible to subsequent proteinase K treatment. A set of reactions without UV irradiation were carried out in parallel. Ribonucleoprotein products were separated from the free RNA by differential retention filter assays. A representative image of one of these assays is shown. Data correspond to the mean of three independent experiments ± standard deviation (SD). The percentage of the 3′ UTR-40S complex at each reaction condition was quantified and referred to that obtained in the absence of proteinase K treatment (see bottom data). (B) Identification of WNV 3′ UTR interacting proteins. The 32P-internally radiolabeled WNV 3′ UTR was incubated with a 30-fold molar excess of the 40S ribosomal subunit and subjected to UV-irradiation (line 1). Reactions were treated with RNase A (line 2) or with RNase A and proteinase K, (line 3) as control reaction. All the reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and the labeled protein products obtained after the treatment with RNase A were further purified for trypsin digestion and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Those labeled protein products are indicated by red asterisk at the right side of the line 2. (C) Location of the identified ribosomal proteins within the crystal structure of the 40S subunit. rRNA is represented as a light blue backbone; ribosomal proteins are displayed as colored ribbons. RPS2, RPS3, RPS8, RPS9 and RPS11, which were identified by LC-MS/MS, are depicted as colored spheres.

Table 1.

Ribosomal proteins identified by LC-MS/MS that bind to the WNV 3′ UTR.

| Protein | Peptides | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPS2 | 16 | 40S assembly Translation fidelity Nucleolar processing of pre-18S rRNA |

(Bernstein et al., 2004; Pisarev et al., 2008) |

| RPS3 | 35 | Structural rearrangements in 40S (pre-initiation complex assembly) Helicase activity during translation Endonuclease activity (DNA repair) Spindle dynamics regulation in mitosis Apoptosis Transcription regulation |

(Gao and Hardwidge, 2011; Graifer et al., 2014; Havkin-Solomon et al., 2023; Jang et al., 2012a; 2012b; 2004; Kim et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010; Sanford et al., 2019; Seong et al., 2012) |

| RPS8 | 14 | 18S rRNA binding and 40S assembly | (Mundus et al., 1993; Yu et al., 2005) |

| RPS9 | 13 | Ribosome biogenesis Translation termination |

(Kim et al., 2003; Lindstrom and Zhang, 2008; Pnueli and Arava, 2007) |

| RPS11 | 6 | 40S assembly Elevated levels in certain tumors |

(Nadano et al., 2001; Yong et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2020) |

These data indicate that de interaction WNV 3′ UTR-40S imply the participation of ribosomal proteins required for translation initiation, though additional contacts with rRNA cannot be ruled out (Dong et al., 2017; Dong and Hinnebusch, 2022; Huang et al., 2020; Pisarev et al., 2008).

3.3. The 40S ribosomal subunit binds to the SL-III element and the double dumbbell domain of the WNV 3′ UTR

Primer extension assays were performed to identify binding sites of the 40S subunit in the WNV 3′ UTR. This RNA was incubated at a 25-fold molar excess of the purified 40S subunit in SHAPE buffer at 37 °C. A control reaction was performed in parallel in the absence of 40S subunit. Reverse transcription was then accomplished with different 32P-5′ end labeled oligonucleotides in order to read the full-length 3′ UTR. Reaction products were resolved by high-resolution denaturing polyacrylamide gels and run alongside with an RNA sequencing reaction in order to map the reverse transcription stops. The relative abundance of the cDNA products was quantified as described in Materials and Methods section.

Specific reverse transcriptase stops were identified in the presence of the 40S subunit, mainly mapping to the SL-III element and the double dumbbell domain (domain II containing the dumbbell elements 5′DB and 3′DB; Fig. 4). Non-specific RT pauses were observed in the rest of the 3′ UTR (Supplementary Figure S1), with the exception of that detected in the nucleotide A10951, which connects the sHP and the 3′SL elements (Supplementary Figure S1B). Although the existence of conformational changes capable of preventing retrotranscriptase progression cannot be ruled out, these results point the SL-III and the double dumbbell domain as two major anchoring sites for the 40S subunit.

Fig. 4.

The 40S ribosomal subunit can be recruited at different sites within the WNV 3′ UTR, as detected by primer extension assays. Representative autoradiographs of the primer extension assays of the WNV 3′ UTR in the presence of 25-fold molar excess of purified 40S ribosomal subunit, in which the SL-III (A) and 5′DB (B) elements are mapped. Primer extension analyses were performed with different 32P-5′ end labeled oligonucleotides in the absence and presence of the 40S subunit, in order to map the entire 3′ UTR. RNA sequence ladders obtained with the same primer were also performed to identify the 40S-dependent RT stops. The extension products were resolved on a 6 % high-resolution denaturing polyacrylamide gels. The proportion of each extension product in the presence of the 40S ribosomal subunit (+) was quantified and referred to that obtained in the (-) reaction. These data were used to calculate Q2 and Q3. Those cDNA products in which the relative intensity was higher than Q3 were considered as differential RT stops and represented as a heatmap. Those relevant RT stops are indicated by red arrowheads and the corresponding nt position is shown. Relevant nucleotides are also indicated on the right side of the gels. Numbering refers to the nucleotide positions of the NY99-flamingo382–99 strain (GeneBank access AF196835).

The results point to the existence of different, specific 40S recruitment sites along the WNV 3′ UTR and entail new roles for the SL-III and the double dumbbell domain during viral translation.

3.4. The PK3 element within the WNV 3′ UTR participates in the 40S recruitment

Primer extension analysis suggest the binding of the 40S subunit to the 5′DB element and the 5′ end of the 3′DB. Interestingly, the 5′DB element participates in the formation of the PK3 structure through the interaction between the TL1 sequence motif and its complementary sequence located at the 3′ end of the 3′DB (Fig. 1). The presence of pseudoknot structures in viral and cellular mRNAs has been associated to the ribosome binding and positioning, as well as to translation control (Brierley et al., 2007; Gupta and Bansal, 2020; Liu et al., 2020). In order to find out the potential role of PK3 in the recruitment of the 40S subunit, in vitro binding assays to the 40S subunit were performed with a collection of RNA constructs bearing deletions in different structural elements of the WNV 3′ UTR (Fig. 5A): 3′WNV_10,400–10,900, which comprises positions 10,400 to 10,900, and hence lacks the 3′ portion of the 3′ UTR including the 3′ end sequence of PK3, PK4, sHP and 3′SL; 3′WNV_10,828–11,029, spanning nucleotides 10,828 to 11,029; therefore, it contains the 3′DB element, the 3′ sequence of PK3, PK4, sHP and 3′SL; 3′WNV_10,742–10,950, which encompasses the double dumbbell elements plus PK3, PK4 and the sHP; 3′WNV_10,742–10,950; and 3′WNV_10,742–11,029, which comprises the complete domains II and III. Control reaction with the full-length 3′ UTR RNA was carried out in parallel. Interestingly, the 208 nt-long RNA transcript 3′WNV_10,742–10,950 bound the 40S subunit at a similar efficiency to that shown by the full 3′ UTR (Fig. 5B). However, those constructs bearing deletions that impede the formation of PK3 were unable to recruit the 40S subunit (Fig. 5), revealing a clear involvement of PK3 in 40S binding. The results show that, whereas deletion of the 129 nts of the 3′ end (resulting in a 500 nt long RNA) abolished 40S binding, the internal 208 nt-long fragment 10,742–10,950 showed complete binding, arguing against a non-specific 3′ UTR-40S interaction. Interestingly, the presence of the 3′SL element (3′WNV_10,742–11,029) induced a slight increase in the yield of the reaction without significantly affecting the Kd value compared to 3′WNV_10,742–10,950, and also promoting a significant increase in the Hill coefficient (see Fig. 5B and Supplementary Table S1), suggesting that the 3′SL element influences the binding cooperativity.

Fig. 5.

The PK3 pseudoknot is critical for the WNV 3′ UTR-40S interaction. RNA constructs lacking the 5′ or the 3′ sequences that are involved in the formation of PK3 were unable to bind the 40S ribosomal subunit. However, a construct preserving the minimal sequence required for PK3 was sufficient to achieve the full recruitment of the 40S ribosomal subunit. (A) Diagram representing the expected secondary structure of the constructs used in this study, indicating the start and stop nucleotide positions according to numbering referred in Fig. 4. (B) The efficiency of the complex formation with the 40S ribosomal subunit for each RNA construct was determined as noted in Fig. 2. Data correspond to the mean of three independent experiments ± standard deviation. (*) indicates statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

Taken together, the data reinforce the idea that the interaction depends on particular structural elements and requires a specific conformation, rather than being a promiscuous and non-specific binding. These findings point that the 5′DB element on its own would not be enough for recruiting the 40S subunit, but rather a specific, high-order structural organization of domain II of the WNV 3′ UTR for the 40S binding would be required. These assays also provide evidence that the PK3 would be necessary for the interaction of the 40S subunit with SL-III, as deduced from the observation that the construct 3′WNV_10,400–10,900 is unable to interact with the 40S subunit (Fig. 5B). Finally, the presence of SL-III improved the yield of the binding reaction but it had no significant effect on the affinity and cooperativity of binding to 40S compared to the 3′WNV_10,742–11,029 RNA (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S1). These results support previous assumption derived from the primer extension analysis of the existence of two sites, and suggest that the 5′DB element could operate as a high affinity recruitment site, while the SL-III would function as a secondary interacting site.

3.5. Structural features in the WNV 3′ UTR for the recruitment of the 40S subunit

The results shown above suggest the relevance of the three-dimensional WNV 3′ UTR structure for the binding of the 40S subunit. In order to accomplish a preliminary structural study of the WNV 3′ UTR-40S complex, differential SHAPE analysis (SHAPE-dif) was carried out (Gherghe et al., 2008). This technique takes advantage of the different selectivity of SHAPE reagents for electronic conformations that represent specific structural features of nucleotides. The combination of the reactivity data obtained with different SHAPE reagents generates a conformational map of the molecule that provides information about unique structural features. We chose NMIA and 1M6 as chemical probes, which differentially react with nucleotides that undergo slow conformational changes (Gherghe et al., 2008) or with stacked nucleotides with fast electronic dynamics (Steen et al., 2012), respectively.

SHAPE-dif analysis was performed with the WNV 3′ UTR RNA, in the absence and presence of the 40S subunit (see Materials and Methods). Interestingly, a general overview of the reactivity patterns showed that domain I of the 3′ UTR displayed preferential reactivity with NMIA in the free RNA, an indicator of slow local dynamics (Fig. 6A), while domains II and III reacted at a similar extent with both reagents, a fact that indicates the absence of preference for a given conformation. Nevertheless, the free 3′ UTR differentially reacted with 1M6 at precise positions located in the junction between SL-IV and CS3 and in the 3′CYC sequence motif (Fig. 6A, lower panel). It is noteworthy that, in both cases, these nucleotides are involved in the formation of pseudoknot structures, which is in good agreement with the structural selectivity shown by 1M6. In addition, these results point to a stacked organization of these reactive nucleotides, as previously demonstrated in other RNA models (Steen et al., 2012). Interestingly, in the presence of the 40S subunit, the differential reactivity completely disappeared in the above mentioned positions (Fig. 6A, lower panel), indicating the existence of conformational changes as a consequence of the 40S recruitment.

Fig. 6.

SHAPE-dif analysis shows conformational variations in the 3′ UTR-40S complex compared to the free RNA. (A) The folding of the WNV 3′ UTR was assayed in the absence (black line) and presence (red line) of the 40S ribosomal subunit using NMIA (upper panel) or 1M6 (central panel) as SHAPE probes. The differential SHAPE profile was drawn by scaling up NMIA and 1M6 reactivity values over a sliding window of 25 nt, followed by the subtraction of the 1M6 corrected values from those calculated for NMIA. (B) Summary of the SHAPE-dif results. Nucleotides showing an increase >0.4 reactivity units of the SHAPE-dif reactivity for the 3′ UTR-40S complex compared to the free 3′ UTR are encircled in cyan. Yellow encircled nucleotides correspond to those positions showing a decrease (>0.4 units) in the SHAPE-dif reactivity for the 3′ UTR-40S complex compared to the free 3′ UTR. Sequence cyclization motifs are color-coded as indicated in Fig. 1.

Besides variations in the SHAPE-dif pattern, additional changes in NMIA and 1M6 reactivity were observed in the 3′ UTR-40S complex, compared to the free RNA. Decreases in 1M6 reactivity values were detected in positions located at the apical portion of SL-III and in the 3′ flank of its stem (Fig. 6A, central and lower panel, and 6B), consistent with the binding of the 40S subunit, as detected by primer extension assays (Fig. 4A). Similarly, NMIA and 1M6 reactivity values were also diminished in precise positions of the 5′DB element (Fig. 6). These observations also agree with the binding of the 40S in this region, as detected (Fig. 4B). Structural reorganization events derived from the 40S recruitment are also likely, as reflected by the increase in 1M6 reactivity in SL-II and CS3 in the 3′ UTR-40S complex. These events could promote the switch from slow local dynamics to stacking conformations involving long-range RNA-RNA interactions.

To identify the structural requirements for the 40S recruitment in the WNV 3′ UTR, hydroxyl molecular interference assays (HMX) with NMIA were performed essentially as previously described (Romero-López et al., 2017; 2023). Briefly, the WNV 3′ UTR RNA was modified with NMIA under subsaturating and denaturing conditions. Then, RNA was renatured and complexed to 40S ribosomal subunit. Ribonucleoprotein complexes were fractionated by differential retention filter assays and purified by passive elution. Modifications were detected as stops in a fluorescently-labeled reverse transcription reaction. The resulting cDNAs were resolved and data were analyzed as described (Romero-López et al., 2017).

Structural requisites for the recruitment of the 40S subunit were detected in nucleotides of the SL-II, SL-III, SL-IV and 3′DB elements (Fig. 7). Interestingly, the binding of the 40S subunit required the 3′ UTR to present an open conformation, reflected as a significant increase in relative NMIA reactivity compared to the free RNA (Fig. 7). These results imply the disorganization of the helices, which could affect the overall structure of the 3′ UTR. In addition, single nucleotides in the 5′DB, SL-I, SL-II, SL-IV and 3′SL elements, as well as in RCS3, showed a significant decrease in NMIA reactivity when the 40S subunit is present (Fig. 7). This may occur because these nucleotides must remain unmodified, since the 40S subunit binding occurs directly in that region. It can be also the consequence of the above noted structural reorganization events in the 3′ UTR, which, in these residues, would promote their stabilization required for the 40S binding.

Fig. 7.

Identification of structural determinants of the 40S recruitment by the WNV 3′ UTR by 2′‑hydroxyl molecular interference (HMX) assays. (A) Histograms show the relative NMIA reactivity for the free WNV 3′ UTR RNA (upper panel) or the 3′ UTR-40S complex (lower panel) under denaturing conditions. Ribonucleoprotein complexes were separated from the free RNA by differential filter retention assays. Modified positions were detected as RT stops in a reverse transcription reaction followed by capillary electrophoresis. Different reactivity values are color-coded as indicated. Data are the mean of four independent experiments ± standard deviation. (B) Relative NMIA reactivity variations in the 3′ UTR-40S complex compared to the free RNA were calculated and represented as a heatmap. Significant variations (p < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk. (C) Sequence and secondary structure of the WNV 3′ UTR including the summary of the HMX results. Red encircled nucleotides show significant increase (>0.2 reactivity units) in NMIA reactivity in the 3′ UTR-40S complex compared to the free 3′ UTR; grey encircled nucleotides denote those positions exhibiting a significant increase (>0.2 reactivity units) in NMIA reactivity in the free 3′ UTR compared to the 3′ UTR-40S complex. Cyclization sequences are color-coded as noted in Fig. 1.

These structural data reinforce the importance of the SL-III and the 5′DB elements for the 40S subunit recruitment and point to the existence of conformational rearrangements in the WNV 3′ UTR that could be required for the control of viral translation.

3.6. A new 40S interacting site in the sHP and the 3′SL elements is dependent on the WNV 5′ end

In an effort to deepen understanding of the mechanism by which the 40S recruitment at the 3′ UTR could influence the 5′ UTR-dependent translation enhancement, primer extension assays were performed with the m7G-WNV construct (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022). This construct encompasses the capped 5′ end of the WNV genome (5′WNV RNA fragment) fused to the FLuc coding sequence plus the WNV 3′ UTR. For these analyses, a 70-fold molar excess of the 40S subunit was used to compensate for the competition of the 40S subunit binding by the 5′ end of the WNV genome.

Importantly, these assays revealed the existence of a new and specific 40S binding site in the m7G-WNV RNA, mapping at the 5′ base of the 3′SL and the loop of sHP elements (Figs. 8A and 8D). This newly discovered 40S binding site was absolutely dependent on the presence of the WNV 5′ end (compare Fig. 8A and Supplementary Figure 1C) and occupies a significant portion of the 3′UAR sequence motif (U10954CUU10957, U10959, U10962C10963) and two nucleotides of the 3′DAR II sequence (G10945G10946) and a nucleotide (A10934) of the 3′CYC sequence (Figs. 8A and 8D).

Fig. 8.

Primer extension assays show the existence of a binding site for the 40S ribosomal subunit in the WNV 3′ UTR that is dependent on the 5′ end of the viral genome. Representative autoradiographs of the primer extension assays of the WNV 3′ UTR in the presence of molar excess of purified 40S ribosomal subunit. Primer extension analysis was performed with 32P-5′ end labeled oligonucleotides in the absence (-) and presence (+) of the 70-fold molar excess of 40S subunit (A) to map 3′SL and sHP elements and (B) to map SL-III element (C) and 5-fold molar excess to map 3′DB and 5′DB elements. The extension products were resolved on a 6 % high-resolution denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Relevant RT stops were determined as in Fig. 4 and they are indicated by black arrowheads on the right side of the gels. (D) Sequence and secondary structure of the WNV 3′ UTR including the summary of the primer extension analyses for the WNV 3′ UTR-40S complex in the presence and absence of the WNV 5′ end. Numbering refers to the nucleotide positions of the NY99-flamingo382–99 strain (GeneBank access AF196835).

These assays also confirmed the presence of the 40S binding site within the SL-III element in the presence of the 5′ end at high 40S ratios (Figs. 8B and 8D). Regarding to the binding site placed at the double dumbbell domain, we observed that it retained the ability to recruit the 40S subunit in the presence of the 5′ end of the WNV genome, even at 40S molar ratios as low as 1:5 (Fig. 8C). In contrast, no RT stops were detected in the SL-III element under such subsaturating conditions (Supplementary Figure S3). This finding supports the notion that the double dumbbell domain could operate as a high affinity interacting site for the 40S subunit, with the SL-III element playing an acceptor role only under 40S saturating conditions.

The fact that the presence of the WNV 5′ end promotes the binding of the 40S subunit to the conserved elements 3′SL and sHP led us to investigate whether the 3′ UTR could also modulate the recruitment of the 40S subunit to the 5′ end. For that purpose, primer extension reactions were performed with the RNA transcript m7G-WNV in the absence and presence of the 40S. In parallel, reactions with the construct m7G-WNV_Δ3’UTR were performed. Interestingly, the results showed a slight displacement of the RT stops towards the 3′ end of the 5′CYC sequence motif in the presence of the 3′ UTR (Fig. 9). This observation correlates with the binding of the 40S ribosomal subunit to the 3′SL element in the presence of the 5′ end and suggests that the 3′ UTR may mediate the positioning of the ribosome at the 5′ end of the viral genome.

Fig. 9.

The 3′ UTR contributes to the positioning of the 40S ribosomal subunit at the 5′ end of the WNV genome. (A) Representative autoradiographs of the primer extension analysis of the 5′ end of the WNV were performed at the conditions indicated at the top of the gels, either in the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of the 3′ UTR. Quantification of each cDNA was accomplished as mentioned in Fig. 4. The resulting values were represented as a heatmap (central panel). Those relevant RT stops, according to the criteria indicated in Fig. 4, are indicated by color-coded arrowheads: red arrowheads denote RT stops detected in the absence of the 3′ end; black arrowheads indicate those RT stops observed in the presence of the 3′ end. (B) Sequence and secondary structure of the 5′ end of the WNV genome including the results obtained by primer extension assays. Nucleotides that form the cyclization sequences are color coded as indicated in Fig. 1. Numbering is as indicated in Fig. 4.

Taken together, these results show the binding of the 40S subunit by the 3′ UTR in a translatable RNA, most likely at the double dumbbell domain, the 3′SL and the SL-III elements. Further, they open new ways to understand the communication between the 5′ and the 3′ termini of the WNV genome. This makes tempting to suggest that the 40S ribosomal subunit could act as a molecular bridge between the two genomic ends, promoting the acquisition of a closed-loop, translatable conformation.

3.7. Interfering with the 40S binding to the WNV 3′ UTR influences the translation efficiency

Primer extension analysis have revealed three potential recruitment sites for the 40S ribosomal subunit within the WNV 3′ UTR. These sites include the SL-III, the 5′DB and the sHP plus the 3′SL elements. We had previously observed that SL-III and 5′DB elements operate in an opposite manner during WNV translation, either repressing or promoting protein synthesis, respectively (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022). Regarding to 3′SL element, controversial results have been obtained for different viral models (Holden and Harris, 2004; Holden et al., 2006; Li and Brinton, 2001). Other elements of the WNV 3′ UTR related to efficient 40S binding, such as 3′DB or PK3, could also contribute to translation control, suggesting that the 40S binding to the 3′ UTR could be a molecular mechanism underlying the translational control exerted by this genomic region.

To go further in this hypothesis, Vero cells were transfected with a series of RNA constructs based on the previously described m7G-WNV RNA but lacking those elements that have demonstrated to play a role in the 40S recruitment (Fig. 10A): m7G-WNV_del3’DB, which lacks the 3′DB element; m7G-WNV_del3’PK3, bearing the deletion of the sequence spanning nucleotides 10,908–10,925, impeding the formation of PK3; and m7G-WNV_d3’SL, deficient in the 3′SL element. The previously described transcripts WNV_dSLIII and WNV_dPK3 (renamed WNV_del5’DB in this work for simplicity), which carry the deletion of the SL-III and 5′DB elements respectively, were used as internal controls, along with the RNA lacking the entire WNV 3′ UTR (m7G-WNV_Δ3’UTR; Fig. 10A) (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022). Cells were co-transfected with each of the above described capped transcripts independently and the m7G-RLuc construct, whose translation is independent on WNV UTRs (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022). Relative luciferase units were quantified at 4 h post-transfection (see Materials and Methods).

Fig. 10.

Deletion of the 40S binding determinants within the WNV 3′ UTR interferes with viral translation. (A) Secondary structure of the m7G-WNV RNA used for the translation assays, including the structural and functional elements mentioned in the text. A series of deleterious mutants in precise elements and sequence motifs that are related to the 40S recruitment was generated and represented in the lower panel. (B) Vero cells were co-transfected with each independent capped construct and the m7G-RLuc RNA, for well-to-well normalization. Translation efficiency was calculated as the ratio between the FLuc and RLuc relative luciferase units, and referred to that obtained for the m7G-WNV construct. Data are the mean of four independent experiments ± standard deviation. Significant differences (p < 0.05) in the relative translation of the tested constructs compared to that obtained in for the m7G-WNV RNA were calculated by applying a non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.

Consistent with our previous findings, the 5′DB was partially required to achieve full WNV translation efficiency, while SL-III was confirmed as a translational repressor (p < 0.05) (Fig. 10B) (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022). The results obtained with other RNA constructs demonstrated that deletion of the 3′SL element interfered with protein synthesis up to ∼70 % (p < 0.05), a comparable yield to that obtained in the absence of the entire 3′ UTR (Fig. 10B). This result points to 3′SL as an essential important player in the regulation of the WNV translation, a role that could be mediated by the recruitment of the 40S ribosomal subunit. Further, the 3′DB element and PK3 are also necessary to accomplish the proper functioning of the WNV 3′ UTR as translation enhancer, leading their absence to ∼50 % decrease in translation efficiency (p < 0.05) (Fig. 10B). Importantly, the differential behavior exhibited by the tested RNA constructs could not be attributed to significant differences in their intracellular stability (see Supplementary Figure S4), as it has also been previously described by testing other closely related viral models (Bai et al., 2013; Edgil et al., 2006; Romero-López and Berzal-Herranz, 2012; Song et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020).

The results derived from translation assays make tempting to propose a link between the 40S recruitment and the translation enhancer effect mediated by the WNV 3′ UTR, suggesting that the interaction 3′ UTR-40S is a likely mechanism for translation control in WNV.

4. Discussion

The 3′ UTR of WNV is a cap-dependent and cap-independent enhancer of viral translation (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022). Our results support a model by which the molecular mechanism underlying such effect would involve the specific recruitment of the 40S ribosomal subunit by the 3′ UTR. This recruitment could mediate the establishment of a genomic end-to-end communication ― according to the definition of this term made by Vicens et al. (Vicens et al., 2018) ― leading to the positioning of the 40S at the 5′ translation initiation site.

The binding of translational machinery by the 3′ UTR of viral RNAs has been largely reported, e.g. such as in HCV (Bai et al., 2013; Rios-Marco et al., 2016; Romero-López et al., 2018) and Sindbis virus (SINV) (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2016); or via the 3′-CITEs in some plant viruses (Jaafar and Kieft, 2019). Such recruitment occurs in a specific manner and has a different effect on protein synthesis in each case. Thus, while 3′-CITEs favor the translation initiation, the 3′ UTR increases viral RNA translatability in HCV and SINV without affecting the first round of translation. In WNV, it has been demonstrated that viral subgenomic constructs lacking the 3′ UTR can be translated, though to a low efficiency (Berzal-Herranz et al., 2022). Different scenarios can be considered; it is plausible that the binding of the 40S ribosomal subunit by the 3′ UTR would improve the translation yield in WNV by promoting the efficient recycling of the ribosomes to the 5′ end of the viral genome, as well as the multiple usage of the viral RNA as translation template. It is also likely that the 3′ UTR could promote the entry of 40S at the translation initiation site during early stages of translation.

The results shown in the present manuscript allow us to propose that the WNV 3′ UTR binds the 40S ribosomal subunit with high efficiency (Fig. 2). In fact, Kd values within the low nM range argue for a specific interaction, as stated previously by Doudna and coworkers (Bai et al., 2013). The specificity of the WNV 3′ UTR-40S interaction is also supported by the observation that deletion of the last 129 nt of the WNV 3′ UTR abolished the binding of the 40S subunit, while an internal fragment of approximately 200 nt supported efficient binding. Even more, the WNV 3′ UTR-40S interaction is slightly competed by the presence of a negative control RNA at the highest concentration tested. This effect could be explained by the saturation of the 40S ribosomal surface, which may interfere with weak contacts with the 40S by specific RNA structural elements as it has also been described for HCV 3′ UTR (Bai et al., 2013). Further, at least two ribosomal proteins that crosslink with the WNV 3′ UTR also were identified to interact with the 3′ UTR of HCV. Taken together, these results support the specificity of the interaction.

It is noteworthy that the 3′ UTR-40S complex can be only partially competed with the 5′ end of the viral genome (Fig. 2), leading to the assumption that the WNV 3′ UTR-40S interaction would be preferential in the absence of other factors. Nevertheless, primer extension analyses demonstrated that the WNV 5′ end binds the 40S ribosomal subunit on its own, suggesting that this interaction, while showing low affinity, is stable enough to be detected under the experimental conditions tested. Interestingly, the primer extension analyses also revealed that the 40S positioning in the 5′ end did not occur at the expected translation start codon (Fig. 9). All these results together entail that additional factors are required for the effective binding of the 40S subunit at the 5′ end. This assumption is also supported by previous reports in which authors demonstrated that the formation of the pre-initiation complex 48S and the fidelity of the AUG codon recognition depend on eIF1A (Brito Querido et al., 2020; Obayashi et al., 2017; Valasek et al., 2004).

The presented data demonstrate that the 3′ UTR-40S interaction involves ribosomal proteins. (Fig. 3). These proteins play roles during ribosome assembly, but two of them, RPS3 and RPS11, also participate in key cellular processes, like apoptosis or mitosis, providing new ways of study for the molecular pathology of the WNV disease (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Interestingly, RPS3 has also been found to interact with the ZIKV and DENV RNA (Ooi et al., 2019), suggesting that the recruitment of the 40S subunit could be a general phenomenon in flaviviruses. Preliminary in vitro binding assays of the 40S ribosomal subunit to the 3′ UTR of DENV and YFV are in good agreement with this hypothesis (data not shown) and support the notion that this could be a general mechanism in flaviviruses.

It has been established that the adoption of a closed-loop architecture is a requirement of translation of most mRNAs (Vicens et al., 2018). The acquisition of a circular topology of the flaviviral RNA genome during translation has been largely proposed (Vicens et al., 2018). However, this phenomenon would not be dependent on direct RNA-RNA interactions by the cyclization sequences, as instead occurs during replication. This is supported by previous findings showing that mutations that prevent the 5′−3′CYC interaction increased translation performance (Holden et al., 2006). Furthermore, the exchange of the CS sequences, while retaining complementarity, did not achieve efficient translation (Chiu et al., 2005). Therefore, this points that the acquisition of a closed-loop topology by the genomic flaviviral RNA during translation would have to be mainly mediated by protein bridges of the cell's translational machinery (Polacek et al., 2009). Consistently, our findings also support the notion of a communication between both ends of the viral genome that could be mediated by the 40S ribosomal subunit. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the existence of possible long-distance RNA-RNA interactions between the two ends, as it has been described for the genomic RNA of HCV, where reciprocal structural fine-tuning of each genomic RNA end has been demonstrated in the presence of the other (Romero-López et al., 2012; 2014).

Primer extension analysis revealed the existence of RT stops at the base of the 3′SL element, overlapping with the 3′UAR cyclization sequence, that are dependent on the presence of the 5′ end (Fig. 8A). Conversely, RT stops in the presence of the 40S subunit appear at the base of the cHP element, partially occupying the 5′CYC sequence motif (Fig. 9). This finding correlates with the previously proposed model according to which the 5′ cyclization sequences must be “occupied” to prevent their interaction with their corresponding 3′ partners during viral translation initiation (Liu et al., 2016; Sanford et al., 2019), thus favoring the correct positioning of the 40S subunit at the appropriate start codon.

These assays also suggested the existence of two further potential 40S subunit binding sites in the WNV 3′ UTR, which are independent on the 5′ end of the viral genome (Fig. 4 and Fig. 8). These sites locate at the dumbbell (5′DB and 3′DB) and the SL-III elements. Our results also show that the binding at both sites depends on the formation of the PK3 pseudoknot (Fig. 5). The binding sites appeared differentially occupied by the 40S ribosomal subunit depending on its concentration (Fig. 8 and Supplementary Figure S3). Thus, while RT stops could be detected at the 5′DB element even at ratios 3′ UTR-40S as low as 1:5, in the SL-III element these emerged at 25-fold molar excess of the 40S ribosomal subunit (Fig. 8C and Supplementary Figure S3). This result clearly points to a differential affinity by the 40S at each element, which could be related to a different role during viral translation. Indeed, the dumbbell and the SL-III elements have been shown to operate as opposite partners during translation (Fig. 10), making it tempting to propose that differential 40S recruitment could underlie these observations. Furthermore, PK3 seems to be essential for the 40S binding (Fig. 5) and its deletion induces a 50 % decrease in translation efficiency (Fig. 10). Therefore, the combination of translation assays and primer extension data evidence an interesting correlation, which might link the 40S recruitment by the 3′ UTR with translational efficiency and the existence of an end-to-end cross-talk in the WNV genome during protein synthesis.

Structural analysis performed with the WNV 3′ UTR RNA in the absence or presence of the 40S subunit showed the relevance of preserving the conformation of the whole WNV 3′ UTR for the recruitment of the 40S (Figs. 6 and 7). Significant differences in NMIA reactivity were detected by HMX throughout the entire RNA molecule. It is noteworthy the fact that these variations in the 3′DB element involve an increase in nucleotide flexibility that is required for the efficient binding of the 40S subunit (Fig. 7). This finding suggests that the 3′DB element is a dynamic structural unit, which can modify its folding in response to different conditions. Interestingly, we have previously demonstrated that the WNV 3′ UTR forms dimeric units, being the 3′DB element a key player for this process (Romero-López et al., 2023). Further, a clear correlation between 3′DB and translation efficiency was observed, showing that this element is required to achieve translational enhancement mediated by the WNV 3′ UTR (Romero-López et al., 2023). Again, the present data point that this effect could be mediated by the implication of the 3′DB in the recruitment of the 40S subunit and its subsequent delivery to the 5′ UTR.

With these data and based on previous results, we could hypothesize that the opening of the 3′DB structure allows the binding of 40S to the 5′DB and its subsequent transfer to the base of the 3′SL element. This interaction would lead, in some way, to the delivery and further correct positioning of the 40S subunit at the translation initiation site within the genomic 5′ end, competing the 5′−3′CYC interactions required for replication. Importantly, deletion of the 3′SL element induced a reduction in translational yield to levels comparable to those obtained in the absence of the complete 3′ UTR (Fig. 10). The 3′SL has also been shown to contribute significantly to protein synthesis in DENV (Holden and Harris, 2004; Holden et al., 2006), confirming a shared role of 3′SL among different flaviviruses and suggesting that 40S recruitment could be behind this regulation. Conversely, the blockage of the 3′DB element could favor a structure competent for 40S binding to the SL-III, which might sequester this ribosomal unit from binding to the 3′SL, therefore promoting a negative regulation of translation as observed (Fig. 10).

Taken together, these data open a new field of study to evaluate the recruitment of the 40S subunit by the 3′ UTR as a likely molecular mechanism that could be involved in the communication between the 5′ and 3′ ends of the flaviviral genome during translation. Further, unpublished results from our laboratory suggest that the recruitment of the 40S is shared by the 3′ UTR of DENV and YFV (data not shown). Considering that the 3′ UTR of these flaviviruses greatly differs in sequence and structural elements, our findings open a new line of study aimed at the identification of those RNA structural determinants for the 40S binding and the related control of viral translation.

Author statement

Authors have not used generative AI or AI-assisted technologies in the writing process.

Funding

This work and S.E.R.-L. were funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación y Universidades/Agencia Estatal de Investigación/10.13039/501,100,011,033 (PID2019–104018RB-100 to A.B.-H.). Funding for open access charge: CSIC Open Access Publication Support Initiative through its Unit of Information Resources for Research (URICI).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sara Esther Ramos-Lorente: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Beatriz Berzal-Herranz: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Cristina Romero-López: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Alfredo Berzal-Herranz: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Carles Suñé and Carlos Briones for providing us with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit, in vitro transcription kits and other molecular biology reagents as well as plastic consumables. The research group is a member of the CSIC interdisciplinary framework “LifeHUB.CSIC”. The results presented are part of the experimental work of the Doctoral Thesis by S.E.R.-L.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2024.199340.

Contributor Information

Cristina Romero-López, Email: cristina_romero@ipb.csic.es.

Alfredo Berzal-Herranz, Email: aberzalh@ipb.csic.es.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Alvarez D.E., Filomatori C.V., Gamarnik A.V. Functional analysis of dengue virus cyclization sequences located at the 5′ and 3′UTRs. Virology. 2008;375(1):223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez D.E., Lodeiro M.F., Luduena S.J., Pietrasanta L.I., Gamarnik A.V. Long-range RNA-RNA interactions circularize the dengue virus genome. J. Virol. 2005;79(11):6631–6643. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6631-6643.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo J., Ulryck N., Deforges J., Chamond N., Lopez-Lastra M., Masquida B., Sargueil B. Loop IIId of the HCV IRES is essential for the structural rearrangement of the 40S-HCV IRES complex. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2016;44(3):1309–1325. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Zhou K., Doudna J.A. Hepatitis C virus 3′UTR regulates viral translation through direct interactions with the host translation machinery. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2013;41(16):7861–7874. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso-delJesus A., Lucena-Aguilar G., Sanchez L., Ligero G., Gutierrez-Aranda I., Menendez P. The Nodal inhibitor Lefty is negatively modulated by the microRNA miR-302 in human embryonic stem cells. FASEB J. 2011;25(5):1497–1508. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-172221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein K.A., Gallagher J.E., Mitchell B.M., Granneman S., Baserga S.J. The small-subunit processome is a ribosome assembly intermediate. Eukaryot. Cell. 2004;3(6):1619–1626. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.6.1619-1626.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzal-Herranz A., Berzal-Herranz B., Ramos-Lorente S.E., Romero-López C. The genomic 3′ UTR of flaviviruses is a translation initiation enhancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(15) doi: 10.3390/ijms23158604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya D., Diamond P., Basu S. An Independently folding RNA G-quadruplex domain directly recruits the 40S ribosomal subunit. Biochemistry. 2015;54(10):1879–1885. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley I., Pennell S., Gilbert R.J. Viral RNA pseudoknots: versatile motifs in gene expression and replication. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5(8):598–610. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]