INTRODUCTION

Over the years, besides the focus on mental disorders, the focus has shifted to mental health and well-being. In contrast to mental disorders, the concept of mental health and mental well-being is important for everyone in society. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease” (WHO, 2020).[1] Accordingly, it can be said that since the beginning the WHO has integrated the concept of well-being into its definition of health.

Three core concepts crucial to enhancing health emerge from the definition of health as per the WHO.[2] Mental health is an intrinsic component of overall health, mental health encompasses more than just the absence of illness, and mental health is intricately intertwined with physical health and behavior.

Defining mental health is crucial, but it is not necessarily required for its improvement. Value differences between countries, cultures, classes, and genders may appear to be too significant to allow for agreement on a definition. However, just as age and wealth have many diverse manifestations worldwide while maintaining a basic common-sense universal meaning, mental health can be defined without limiting its interpretation across cultures.[2]

The WHO defines mental health as follows:

A state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully and is able to contribute to his or her community. It is a crucial element of health and well-being that supports both our individual and group capacity to decide, form connections, and influence the world we live in.[3]

These WHO definitions differentiate between subjective happiness or life satisfaction (hedonic well-being) and positive psychological functioning (eudaimonic well-being).[4]

The American Psychological Association describes the concept of mental health as follows:[5]

Mental health is a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioural adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life.[5]

While this definition represents significant progress in moving away from the conceptualization of mental health as the absence of mental illness, it raises several concerns and lends itself to potential misunderstandings by identifying positive feelings and positive functioning as key factors for mental health.[6]

Researchers and health organizations acknowledged the difficulty in reaching a consensus on mental health due to cultural variations and sought to construct an inclusive definition while avoiding restrictive assertions. While it was commonly understood that mental health is more than the absence of mental disease, there was no universal agreement on equating mental health with well-being or functioning, resulting in a definition that includes a wide range of emotional states and “imperfect functioning.”[6]

The proposed new definition by Galderisi et al.[6] states that “Mental health is a dynamic state of internal equilibrium that enables individuals to use their abilities in harmony with the universal values of society. Basic cognitive and social skills; ability to recognize, express and modulate one's own emotions, as well as empathize with others; flexibility and ability to cope with adverse life events and function in social roles; and harmonious relationship between body and mind represent important components of mental health which contribute, to varying degrees, to the state of internal equilibrium.”

CONCEPT OF POSITIVE MENTAL HEALTH

It has been conceptualized as a positive emotion that leads to a feeling of happiness. The personality traits of people with positive mental health include psychological resources of self-esteem, mastery, and resilience, which is the capacity to cope with adversity and avoid a breakdown when confronted by stressors. Such people have the capacity to master their environments, and they have the ability to identify, confront, and solve problems. Mental health is clearly influenced by cultural, socioeconomic, and political situations.[2]

Mental health has intrinsic values, as described as follows.[2]

Mental health is critical for an individual's well-being and functioning.

Good mental health is a valuable resource for individuals, families, communities, and nations.

Mental health, as an integral component of overall health, contributes to societal functions and has an impact on overall productivity.

Everyone is concerned about mental health because it is generated in our daily lives in our homes, schools, workplaces, and leisure activities.

Good mental health contributes to a society's social, human, and economic capital.

Spirituality can contribute significantly to the development of mental health, and mental health influences spiritual life.[7]

Culture and mental health

Each culture has an impact on how people perceive and comprehend mental health. Understanding and sensitivity to culturally valued characteristics will boost the relevance and success of prospective treatments.[2]

Race, ethnicity and genetic- its influence on mental health and mental well-being

Race and ethnicity, along with genetic factors, play complex roles in shaping mental health and well-being. Social determinants linked to race and ethnicity can contribute to disparities in access to mental health care and resources, impacting mental well-being. Genetic factors influence vulnerability to certain conditions, but interactions with the environment and experiences are vital. For instance, the “diathesis-stress” model highlights how genetic predisposition interacts with stressors.[8] These intertwined factors underscore the need for culturally sensitive care and a comprehensive understanding of mental health influences. Culture significantly shapes perceptions of well-being, influencing emotional expression, social support systems, and coping strategies, ultimately impacting an individual's mental well-being.

Mental health and social capital

The idea of “social capital” has been central to the recent renaissance in thinking about social connectivity and health promotion. According to Putnam (1995), social capital “refers to features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit.”[9] Social capital is also impacted by economic and social conditions. Research over the previous two decades has shown relationships between social capital and economic development and the efficiency of human service systems and neighborhood improvement.[2] According to Woolcock (1998), having more social capital can protect individuals from social isolation, create a sense of social security, lower crime, enhance education and societal functioning, and enhance job performance.[10]

There are continuous research and discussion on the connections between social capital, physical health, and mental health and the viability of promoting mental health to boost social capital. The strength of social capital lies in its capacity to view the world from a fresh perspective, considering both environmental and social factors and associated social groups. In contrast to aggregated individual health outcomes, this perspective on networks of people interacting with their environments offers the potential to explain a wider range of collective outcomes.[2]

Mental well-being

The concept of mental well-being has developed over time in response to advances in domains, such as psychology, medicine, sociology, and public health.

Initially, a focus on mental illness, with an emphasis on diagnosing and treating problems, typically overshadowed mental well-being.

However, in recent decades, there has been a paradigm shift toward a more holistic and positive perspective on mental health.

However, the term “mental well-being” can be ambiguous at times, as it may or may not indicate the absence of mental illness or distress. Well-being has been highlighted as an indicator of national prosperity and has been associated with enhanced physical and mental health.[3]

Mental well-being is characterized by the following:

Optimal physical and behavioral health

Life's purpose

Active participation in enjoyable work and play

Pleasant relationships

Contentment

Mental health and mental well-being are different phenomena. Ill mental health or mental disorders are characterized by abnormal psychological patterns, emotional distress, and impaired functioning. The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007 showed that mental well-being has relatively independent associations with symptoms of mental illness.[11] It is possible for mental well-being to persist even when experiencing mental suffering.[11]

The determinants and variations of mental well-being among individuals with mental health issues are less studied and understood compared with those without such problems.[11]

Mental well-being can fluctuate with the phases of mental illnesses, which often involve relapses and remissions. The number, frequency, and duration of relapses may influence the variation in mental well-being.[11]

Defining well-being is crucial for understanding and discussing mental health and public mental health, but it has been the subject of much debate and some controversy in recent years. Well-being falls outside the medical model of health, as it is not a diagnostic entity. It is widely recognized that subjective well-being differs significantly among individuals, as well as the factors that influence it.[12]

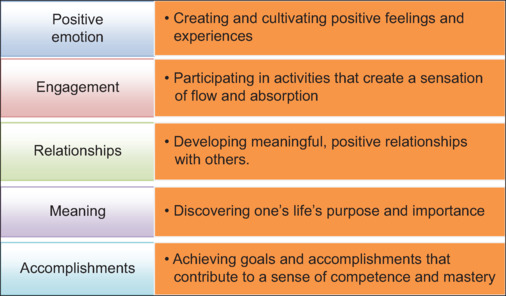

Mental well-being aligns closely with the WHO's comprehensive and positive definition of health and with the positive psychology approach promoted by Seligman. A similar approach to defining mental well-being is used by faculties of public health in the UK.[12] Seligman's proposed PERMA model of psychological well-being as mention in Figure 1.[13]

Figure 1.

Five core elements of psychological well-being Seligman's PERMA model[13]

Social inclusion and well-being

Wellness is inextricably linked to social elements that can either support or obstruct social inclusion. It is obvious that a variety of obstacles, such as trauma, poverty, unemployment, and other bad social situations, can all have a substantial impact on the onset of behavioral health issues in individuals.

These issues not only have an impact on people's mental and emotional well-being, but they can also lead to a larger marginalization of people, limiting their access to critical social resources, such as education, economic opportunities, leisure activities, cultural involvement, and healthcare services.

Recognizing this, it becomes critical for us as a society to actively participate in the process of building vibrant, holistic, and inclusive communities. We can try to close the gaps generated by these by creating an environment that appreciates and prioritizes well-being.

MENTAL WELL-BEING AND QUALITY OF LIFE

Mental well-being refers to a positive state of emotional, psychological, and social health, characterized by a sense of contentment, resilience, and the ability to effectively cope with life's challenges. It encompasses positive emotions, a sense of purpose, and the capacity to engage in fulfilling relationships and activities.

Quality of life, however, is a broader concept that encompasses various domains of an individual's life, including physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, environment, and personal goals. It reflects an individual's overall satisfaction with their life circumstances and their perceived ability to pursue their aspirations.

Mental well-being is a key component of overall quality of life (QoL), as positive mental health contributes significantly to an individual's perception of their life's value and fulfillment.

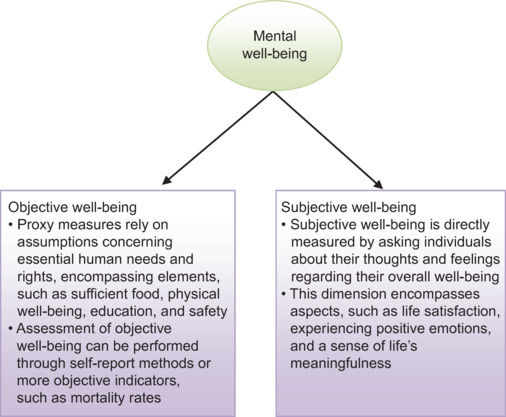

Although there are many methods for defining mental well-being, such as dimensional categorization as shown in Figure 2, mental well-being is thought to have both subjective and objective components.[12]

Figure 2.

Objective and subjective dimensions of mental well-being

Although the concept of QoL has been now used for more than half a century, there still needs to be more consensus on the definition of QoL. As per the WHO, QoL is defined as “an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and about their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”.[14] It is further clarified that QoL refers to a subjective assessment rooted in the person's cultural, social, and environmental context. Besides this, there are other definitions of QoL too. Wenger et al.[15] defined QoL as “an individual's perceptions of his or her functioning and well-being in different domains of life.” Another definition that only focuses on positive aspects of life defines QoL as “The essential characteristics of life, which in the general public is often interpreted as the positive values of life, or the good parts of life, or the total existence of an individual, group or society”.[16] Although it is emphasized that QoL is more of a subjective judgment, some of the researchers have argued that QoL is determined by a host of objective parameters and, accordingly, define QoL as “an overall general well-being that comprises objective descriptors and subjective evaluations of physical, material, social, and emotional well-being together with the extent of personal development and purposeful activity, all weighted by a personal set of values”.[17]

There have been some efforts to distinguish QoL from other related concepts, especially in the context of health and diseases. QoL differs from symptoms of an illness or disability arising from the illness. In the context of any illness, QoL should be understood as the perceived effect of the illness by the person on their life (WHO, 2020). QoL also should not be understood as the same or similar to lifestyle, life satisfaction, mental state, or well-being. QoL is understood as the perception of the individual about their life, whereas “well-being” is more of an indication of positive emotions and satisfaction or contentment, with a lack of long-standing and persistent negative emotions. QoL also should not be equated with the standard of life, which is determined by wealth or material goods.[18]

NEUROBIOLOGY OF MENTAL WELL-BEING

The concept of mental well-being has several dimensions and includes a variety of cognitive, emotional, and social components. It refers to a state involving complete psychological and emotional well-being that is defined by pleasant emotions, efficient functioning, and a feeling of fulfillment in life.

A complex combination of neuronal circuits, neurotransmitters, hormones, and brain areas underlies the neurobiology of mental health. Here are some significant neurobiological aspects of mental well-being listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Various hypotheses of the neurobiological model of well-being

| Neurotransmitters or neuronal circuit | Description |

|---|---|

| Neurotransmitters and neurocircuitry 1) Serotonin 2) Dopamine 3) Endorphins |

This neurotransmitter is often linked to mood regulation and emotional balance. Low levels of serotonin have been associated with conditions, such as depression and anxiety. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a class of antidepressants, work by increasing serotonin levels in the brain Dopamine plays a role in reward, motivation, and pleasure. Healthy dopamine function is linked to feelings of satisfaction and contentment. Imbalances in dopamine can contribute to conditions, such as depression and addiction These natural pain-relieving compounds are associated with feelings of pleasure and euphoria. Physical activity, laughter, and positive social interactions can trigger endorphin release |

| Stress response and cortisol | The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is a crucial part of the body’s stress response. Chronic stress and elevated levels of cortisol, the primary stress hormone, can have detrimental effects on mental well-being. Effective stress management is important for maintaining mental health |

| Prefrontal cortex and emotional regulation | The prefrontal cortex, especially the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, is involved in executive functions, such as decision-making, impulse control, and emotional regulation. A well-functioning prefrontal cortex contributes to effective coping strategies and emotional resilience |

| Limbic system and emotion processing | The limbic system, including structures, such as the amygdala and hippocampus, plays a key role in processing emotions and forming memories. A balanced and healthy limbic system contributes to stable emotional states and adaptive responses to stressors |

| Default mode network (DMN) | The DMN is a network of brain regions that becomes active when the mind is at rest or engaged in introspective thinking. It is associated with self-referential thoughts, mind wandering, and aspects of mental well-being, such as self-awareness and self-reflection. |

| Neuroplasticity and resilience | Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to adapt and rewire itself in response to experiences and learning. Positive experiences, mindfulness practices, and social connections can promote neuroplasticity and enhance resilience to stress and adversity. |

Relationship between mental health and well-being

The relationship between mental health and well-being can be viewed from two perspectives: the dual continuum model and the single continuum model.[12]

The dual continuum model sees mental health and well-being as separate but related, allowing for high well-being despite a mental illness diagnosis.

The single continuum model integrates mental well-being into mental health on a spectrum, suggesting that improving overall population well-being can reduce mental illness prevalence.

Although evidence supports a single continuum model for common mental health disorders, controversies persist in promoting mental health and measuring population well-being, particularly for severe and enduring mental illness.

Mental health is a vital aspect of human life, affecting individuals, society, and culture. It contributes to well-being, productivity, and prosperity at both individual and societal levels.

Being an inseparable part of general health, mental well-being is crucial for proper functioning in society and impacts various aspects of life. Positive mental health brings about significant social, human, and economic benefits, fostering growth and development in every society.

Measuring mental well-being

Measuring mental well-being is critical for gaining a better understanding of people's psychological health and general QoL. It entails evaluating a variety of factors, such as good emotions, life satisfaction, and a sense of purpose.

Researchers and policymakers obtain vital insights into mental health promotion and intervention initiatives by investigating these variables. Effective assessment methods aid in the identification of areas for improvement and in assisting individuals in their pursuit of optimal well-being. Table 2 shows the scales used in measuring mental well-being.

Table 2.

Scales for assessment of well-being

| Name of the scale | Number of items | Domains |

|---|---|---|

| WHO-5 Well-Being Index | Five-item questionnaire It is suitable for children aged nine and above |

No specific domains |

| Psychological Well-Being Scale | 42-item version 18-item version |

Measures well-being and happiness in six domains, that is, autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relation with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance |

| Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) | 14-item scale | Self-report scale Consists of 14 positively worded items assessing positive affect, relationships, and functioning over the last 2 weeks on a 5-point Likert scale |

| BBC Subjective Well-Being Scale | 24-item self-report questionnaire | Five domains of well-being in this scale include goal pursuit, life satisfaction, positive affect, quality of life, and sense of meaning |

| Well-Being Numerical Rating Scales (WB-NRSs) | Five-item instrument to assess physical, psychological, spiritual, relational, and general well-being | |

| Comprehensive Well-Being Scale | 20 items | Factor analysis yielded a 2-factor structure, that is, intrapersonal well-being and transpersonal well-being |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) | 5 items | Self-report measure that evaluates the overall life satisfaction Each statement is rated on a 7-point Likert scale |

| General Well-Being Schedule | 23 items | Focuses on subjective feelings of psychological well-being |

| Life Satisfaction Index A | 20 items | Focuses on psychological well-being |

| Quality-of-Life Scale | 19 items | Assess psychological well-being related to the quality of life; it measures four domains (i.e., control, autonomy, pleasure, and self-realization) |

| Mental Health Continuum is Long and Short-Form | 40 items 14 items |

Measures psychological well-being, social well-being, and emotional well-being |

| Flourishing Scale | Eight items | Mainly measures psychological well-being in the flourishing domain |

| PREMA Profiler | 23 items | It mainly measures psychological well-being in the flourishing domain, and the subscales include positive and negative emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment, and health |

| Flourishing Index | Assesses psychological well-being | |

| Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) | 20 items | Assesses positive and negative affect |

| Bradburn Scale of Psychological Well-Being (Affect Balance Scale) | Ten items | Assesses positive and negative affect |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale | Five items | Assess general life satisfaction |

| Life Satisfaction Scale | Four items | Assess general life satisfaction |

| Pearlin Mastery Scale | Seven items | Assesses positive psychological well-being |

| Internal-External Locus of Control Scale | 29 items | Assesses mastery domain of positive psychological well-being |

| Subjective Happiness Scale | Four items | Assesses happiness domain of positive psychological well-being |

Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) has been translated and validated in India[19]

Measurement of Well-being and Quality of life: Different instruments have been developed to assess well-being over the years. As well-being is subjective, most of the instruments used to evaluate well-being are self-reported. The length of these instruments varies from a single-item global life satisfaction question to multiple-item scales assessing different components of well-being. Some of the available scales are listed in Table 2. Among all these scales, the WHO-5 Well-Being Index is possibly the only scale available in about 30 languages, although not in any of the Indian languages.

The various available QoL instruments can be broadly divided into generic QoL instruments and those that are disease-specific. Some of the standard generic QoL instruments include World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Instrument (WHOQOL-100), World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF), Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36 (MOS SF-36), EuroQol 5 Dimension (EQ-5D), Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12), and Visual Analogue Scale EQ visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS). Studies involving patients with various physical illnesses suggest impairment in QoL. Some of the QoL scales developed by the WHO specifically focus on spirituality, religiousness, and personal beliefs (SRPB), and accordingly, the scale is known as WHOQOL-SRPB. Among the various scales of QoL, WHOQOL-BREF[20] and WHOQOL-SRPB[21] have been validated in Hindi in India.

A comprehensive understanding of mental health and well-being necessitates a detailed exploration of the various determinants that influence both individual well-being and societal outcomes, as highlighted in the preceding discussion.

DETERMINANTS OF MENTAL HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

The relationship between well-being and mental health problems is interrelated. When well-being is high, the likelihood of experiencing mental illness decreases, whereas poor mental health diminishes overall well-being. Studies indicate that individuals with mental health problems constitute the largest proportion of those with low levels of well-being. Consequently, prioritizing the promotion of well-being is crucial both for preventing mental illness and facilitating recovery from mental health issues.

Higher levels of well-being have numerous favorable effects, including enhanced educational achievements, adoption of healthier lifestyles, and a decrease in risky behaviors, such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and substance abuse. Additionally, high well-being is associated with increased productivity and reduced levels of crime, violence, and antisocial behavior.[22]

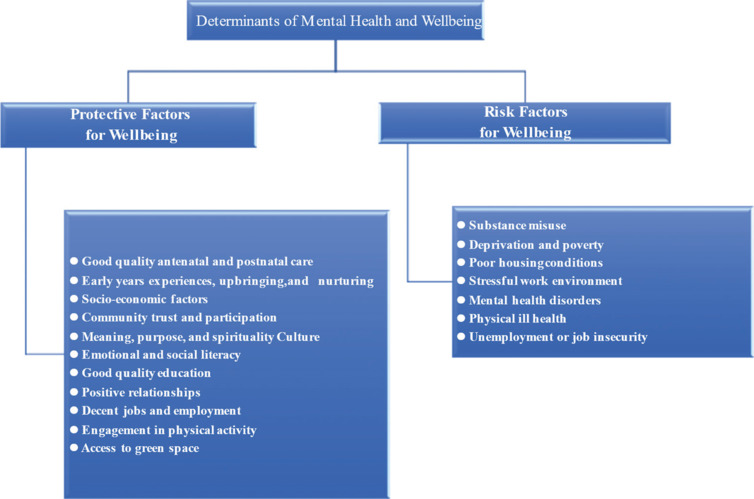

Factors that contribute to good mental health and well-being may vary from those that contribute to poor mental health. Several risk factors increase the chances of experiencing mental health issues or poor well-being throughout one's life. Conversely, protective factors have been identified to promote positive mental health. It is important to note that the determinants of mental well-being may differ from the determinants of mental ill health.[22,23,24,25]

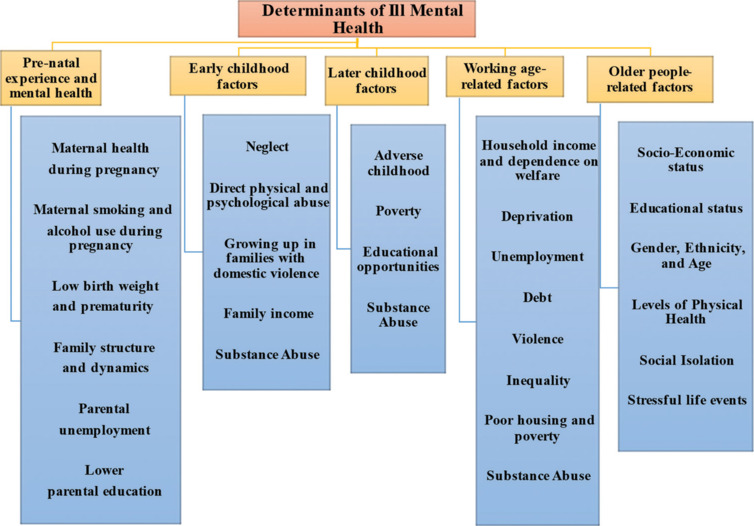

The determinants of mental ill health vary throughout a person's life, but the evidence shows that most mental health issues develop before adulthood.

Research suggests that even a small improvement in well-being can help reduce the risk of mental health problems and support individuals in flourishing. Different determinants of mental health and well-being are presented in Figure 3.[26,27]

Figure 3.

Determinants of mental health and mental well-being

Mental illness-related determinants arise from complex interplays and vary across the lifespan. These factors intertwine, impacting mental health risk and resilience. Figure 4 illustrates the determinants of poor mental health.

Figure 4.

Determinants of ill mental health

An individual's entire mental well-being is influenced by a variety of variables, which also influence mental health. These factors cover the biological, psychological, social, and environmental domains, and they are complex and linked. Table 3 shows various determinants of mental health and well-being.

Table 3.

| Determinants | Examples | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Individual factors | Intelligence | Higher cognitive abilities can contribute to better problem-solving skills and coping mechanisms |

| Easy temperament | Individuals with appositive disposition and adaptability tend to have higher mental Well-being |

|

| Resilience | The ability to bounce back from adversity and cope with stressors positively | |

| Interpersonal relationships | Healthy and meaningful connections with others, including family, friends, and peers | |

| Self-esteem | A positive self-perception and confidence in one’s abilities | |

| Social factors | Social capital | Resources are available through social networks, community participation, and support systems |

| Social support | Having a strong network of supportive relationships and social connections | |

| Community participation | Engaging in activities and contributing to the community, fostering a sense of belonging | |

| Economic factors | Income | Higher-income levels are associated with better mental health outcomes, as financial stability can reduce stress |

| Employment | Meaningful and secure employment provides a sense of purpose and financial security | |

| Poverty | Living in poverty increases the risk of mental health problems due to limited access to resources and opportunities | |

| Education | Level of education | Higher levels of education are often linked to better mental health outcomes |

| Access to quality education | Adequate educational opportunities and resources contribute to positive mental development | |

| Physical health | Physical well-being | Good physical health, including regular exercise, healthy diet, and sufficient sleep Supports mental well-being |

| Access to health care | Adequate access to healthcare services and preventive care contributes to better mental health outcomes | |

| Housing | Housing quality | Safe, secure, and suitable housing conditions positively impact mental well-being |

| Stability | Having stable housing and a sense of belonging in one’s living environment. | |

| Family and relationships | Positive family dynamics | Supportive, loving, and nurturing family relationships foster mental health |

| Support networks | Strong social support systems beyond the family units, such as friends and community groups | |

| Supportive adults | Having caring and supportive adults in one’s life, such as parents or mentors, can provide emotional stability and guidance | |

| Life events | Positive life events | Joyful experiences and significant achievements contribute to positive mental well-being |

| Coping mechanisms | The ability to effectively cope with stressful life events and adapt to changes | |

| Culture and identity | Cultural norms | Cultural values, beliefs, and practices that support mental health and well-being |

| Sense of belonging | Feeling connected to one’s culture, community, and identity promotes mental well-being | |

| Access to resources | Access to mental health services | Availability and affordability of mental health support and treatment options |

| Social support systems | Access to networks and resources that provide assistance during challenging times | |

| Environment | Urban design | Well-designed cities and neighborhoods that promote physical activity, community engagement, and access to nature |

| Green spaces | Access to parks and natural environments that contribute to stress reduction and improved mental health | |

| Community infrastructure | Availability of community centers, recreational facilities, and amenities that foster social connections | |

| Lifestyle factors | Diet | A balanced and nutritious diet contributes to overall mental and physical well-being |

| Exercise | Regular physical activity is associated with improved mental health and mood | |

| Substance use | Associated with poor mental health and well-being | |

| Sleep patterns | Sufficient and quality sleep is crucial for mental and emotional balance | |

| Stigma and discrimination | Reduction in stigma | Challenging and reducing societal stigmatization around mental health issues |

| Promotion of inclusivity | Creating an inclusive and accepting society that embraces diversity |

Protective factors

The concept of protective factors relates to conditions that enhance people's ability to withstand and overcome risk factors and disorders. Protective factors are defined as factors that modify, eliminate, or alter an individual's response to environmental hazards that predispose them to negative outcomes. These protective factors are closely associated with positive mental health.[24]

At the individual level, various factors have been identified as protective throughout different stages of life. These include factors, such as higher intelligence, a temperament that is easy to manage, and the presence of supportive adults. In late adolescence, resilience is linked to positive interpersonal relationships and a strong sense of self.

Social protective factors play a significant role as well. Numerous studies examining the structural aspects of social capital have found a statistically significant correlation between low social capital measures and poor mental health outcomes.[24]

Social capital refers to the resources available to individuals and society through social relationships, including features, such as civic participation, norms of reciprocity, and trust in others, which facilitate cooperation for mutual benefit.

The combined impact of various risk factors, along with the absence of protective factors, and the complex interplay between them, contributes to an increased vulnerability that can lead to mental ill health and eventually diagnosed mental disorders. The field of preventive science has substantially developed over a period, drawing contributions from the social, biological, and neurological sciences. These interdisciplinary efforts have provided insights into the role of both risk and protective factors in the developmental pathways to mental health. Strategies must be aimed at promoting positive mental health by strengthening the factors that provide protection throughout all stages of life. A collective approach that targets the entire population and encompasses a wide range of activities to foster positive mental health must be emphasized.

COPING STRATEGIES

To lower risks, foster resilience, and create environments that are supportive of mental health, promotion, and prevention interventions, first the individual, societal, and structural determinants of mental health are identified. Interventions may be created for single people, particular groups, or entire communities.

Promotion and prevention initiatives should encompass the education, labor, justice, transportation, environment, housing, and welfare sectors, as changing the determinants of mental health frequently requires action beyond the health sector. Here, we discuss the psychological aspects of care and coping in relation to mental health and well-being.[2]

Coping

Coping has various definitions, and it is considered a psychological tool to deal with various external and internal stressful situations. Coping is defined as follows:

The thoughts and behaviors mobilized to manage internal and external stressful situations.[28]

Unconscious or conscious way of dealing with stress[30]

Activities of which the person is aware to reduce stressful events or situations—for example, deliberately avoiding further stressors[31]

Coping strategies are voluntary mobilization of acts, whereas defense mechanisms are subconscious or unconscious responses to reduce stress.[31] Coping strategies help to deal with stressful situations and may lead to emotional and somatic responses. Coping skills do not necessarily remove stress or eradicate challenges, such as mental illness, but they go a long way toward helping people function well despite challenges. People can use their own personal coping skills to take charge of their thoughts, feelings, and actions, and when they do, they find that they experience mental health and even begin to thrive.

Coping can be broadly classified as follows:[31]

Reactive coping (a reaction following the stressor):

Excel in stable environments because they are more routine, rigid, and less reactive to stressors.

Proactive coping (aiming to neutralize future stressors):

Perform better in a more variable environment.

COPING STYLE AND COPING RESPONSE

Coping style is a relatively stable trait of behavior, and it differs from coping response, which is more specific to a particular event. Different people react to stress with different coping styles, and sometimes person can modify his or her coping style as a response to stress.[32]

Coping style[33]

While dealing with difficult circumstances, some individuals could be motivated to solve the issue right away, while others would wish to avoid it altogether. Although there is not a single best way to deal with stress, it is crucial to be aware of different ways to cope.

-

Active Coping

It is dealing with the stressor directly. An active coping strategy is an effort to deal with the stressor and try to lessen its impact on you, whether you choose to focus on the issue at hand (problem-focused) or how your emotions are about the situation (emotion-focused).

-

Avoidant Coping

It entails avoiding the scenario that is causing a stress response or completely dismissing our feelings about the stressor.

APPROACHES USED TO COPE

The mechanisms we use to cope may be called approaches or techniques for how we implement our coping skills. Typically, we utilize cognitive and behavioral approaches to cope.[34]

Cognitive coping strategies are those that involve thinking.

Behavioral coping strategies are action-based.

Emotion-focused and problem-focused coping styles are the two primary coping mechanisms identified by most of the coping literature. Algorani and Gupta (2021),[31] in contrast, add meaning-focused and social coping, often known as support-seeking methods of coping, to the initial two styles to create four key coping categories. A fifth coping method, termed avoidance-focused, is mentioned by Meyerson et al. (2022).[35]

Different coping styles are explained in Table 4.[31,33]

Table 4.

| Coping styles | Description | Usefulness/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Emotion-focused coping style | • It involves reducing emotional disturbance associated with stress while ignoring to address the problem. • It focuses on ourselves and our emotion |

• Aim to reduce emotional distress • Similar to the cognitive approach • It is considered problematic because it may reason for mental health issues • It can be useful in the long term if the problem is uncontrollable |

| Problem-focused coping style | • Address problems causing distress | • Act by identifying and interpreting the problems and planning to solve the problems • Consider the most effective way to deal with stress • Similar to the behavioral approach |

| Meaning-focused coping style | • It uses cognitive strategies to process and make sense of the meaning of a situation | • Useful when one cannot control the situation • Religious and spiritual beliefs and values play an important part in this coping style |

| Social coping (support-seeking) | • When a person neutralizes stress by taking emotional or instrumental support from his/her community or society | • Children and adolescents seek support from parents or peers via this coping style |

| Avoidance-focused coping style | • Trying to avoid stressful situations or events by distraction | • Responsible for the negative functioning of individual |

COPING MECHANISM TYPES

Coping mechanisms can be categorized into maladaptive and adaptive strategies. Maladaptive coping is based on the avoidance of external or internal stimuli. In contrast, adaptive coping strategies match the stressor and aim to reduce emotional distress.

It is important to note that emotional, problematic, significant, social, and avoidant styles can be maladaptive and ineffective or adaptive and effective, depending on the outcome. Table 5[32,36] shows coping mechanism types and their examples.

Table 5.

| Healthy coping or adaptive strategies | Unhealthy coping or maladaptive strategies |

|---|---|

| Healthy coping is utilizing a coping strategy that allows us to respond to a stressful situation in a healthy capacity. When struggling with a stressor or a challenge, healthy coping mechanisms may not instantly feel gratifying, but they can promote positive long-term change Some healthy coping examples include the following:

|

It employs strategies that respond to stressors in an unhealthy or harmful way. While unhealthy coping mechanisms might offer comfort instantaneously, they tend to lead to negative consequences down the road. Some unhealthy coping examples include the following:

|

Numerous coping techniques are effective in some circumstances. A problem-focused strategy may be the most advantageous, according to some studies, while other studies consistently show that some coping techniques have negative effects.[32] Maladaptive coping is the term used to describe coping strategies that are linked to poor mental health outcomes and greater levels of psychopathology symptoms. Disengagement, avoidance, and emotional restraint are a few of these.[36,37]

The medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens and serotonergic and dopaminergic inputs play a role in the physiology of various coping mechanisms.[38]

The neuropeptides, such as oxytocin and vasopressin, also play a significant role in coping mechanisms. However, neuroendocrinology that involved plasma catecholamine levels, corticosteroids, and the activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis was unlikely to have a direct causal association with a person's coping style.[39]

What different coping styles are used in healthy and unhealthy ways is described in Table 6.[40]

Table 6.

Different coping styles in relation to healthy and unhealthy coping mechanisms[40]

| Healthy coping or adaptive strategies | Unhealthy coping or maladaptive | |

|---|---|---|

| Emotion-focused coping style | • Ventilation of emotion • Evaluation of problem • Positive reappraisal of the problem • Meditation and breathing exercises • Humor • Positive thinking • Writing journal |

• Business • Failing to talk about emotions • Toxic positivity: an unhealthy way of looking at something good in a bad situation |

| Problem-focused coping style | • Obtaining information or advice • Planning • Solving problem • Confrontation |

• Overanalyzing and incisiveness |

| Meaning-focused coping style | • Finding good in a bad situation | • Overthinking |

| Social coping (support-seeking) | • Taking help from friends • Speaking with a counselor |

• Isolation • Venting |

| Avoidance-focused coping style | • Controlled distraction | • Substance misuse or smoking • Denial and disengagement • Overspending money without thinking • Overeating • Harming oneself |

MEASURING COPING RESPONSE

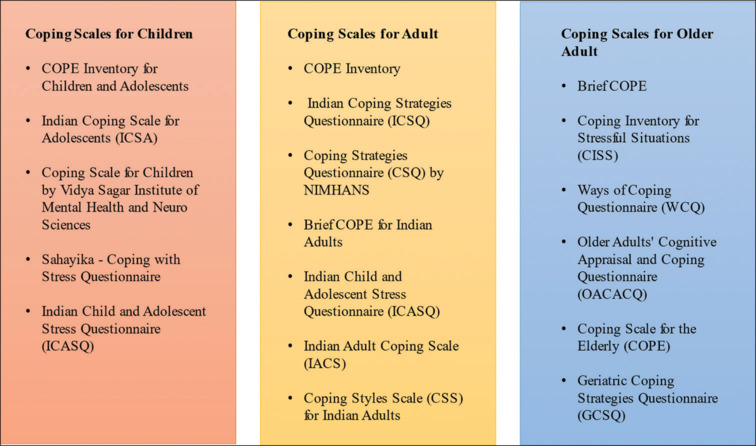

Identifying and measuring coping responses are crucial for understanding how individuals cope with stressors. Resilience and emotional well-being depend heavily on coping mechanisms. To promote positive mental health outcomes, we can obtain valuable insight into the coping strategies people employ through validated scales and inventories. Table 7[41] shows different coping scales and their brief description, and Figure 5 describes different coping scales available for different age groups.

Table 7.

Coping scales[41]

| Scales | Brief descriptions |

|---|---|

| Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) | • To evaluate the different coping strategies individuals, employ when faced with stress, Carver et al. (1989) developed the COPE inventory • In the COPE inventory, there are two components: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping • 1–4 points scored in each statement |

| Brief-COPE | • 28 items • Shorter version of COPE |

| Coping Self-Efficacy Scale | • Assesses a person’s confidence in their ability to cope • 26 statements, score of 0, 5, and 10 for each statement |

| Coping Strategies Questionnaire-Revised | • 27-item questionnaire • Measures the use of strategies for coping with pain by assessing six domains: distraction, catastrophizing, ignoring pain sensations, distancing from pain, coping self-statements, and praying |

| Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) | • Sinclair and Walston (2004) developed the Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) to measure an individual’s ability to cope with stress in a highly adaptive way • Score from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 5 (describes me very well) |

| Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI) | • Measures different proactive approaches to coping and contains seven subscales. • 55 statements score in the range of 1–4 |

| Coping Response Inventory | • Brief self-report inventory • Identifies the cognitive and behavioral responses an individual used to cope with a recent problem or stressful situation |

| Ways of Coping Questionnaire | • It measures coping processes—not coping dispositions or styles |

| Dyadic Coping Inventory (DCI) | • Designed by Bodenmann • 37-item scale, assessing strategies to cope with stressful situations in intimate relationships |

| Coping Checklist | • Developed by Dr Kiran Rao • Available in various Indian languages • Open-ended, 76 items |

Figure 5.

Different coping scales available for the indian populations across different age groups

Various coping scales and coping Behavior Assessment Scale have been adapted and validated in the Indian context. These include

Coping Behavior Assessment Scale.[42]

The coping scale specifically focuses on religious coping, that is, brief religious coping.[19]

Ways of coping checklist has also been translated into Hindi and some of its psychometric properties have been assessed.[43]

The stress coping strategies scale is also available in Hindi.[44]

All the scales mentioned above have been validated by respective authors and can be obtained from them by personal communication.

A variety of techniques are used by people as coping mechanisms to deal with stress, difficulties, and emotional pain. These pursuits are numerous and individual, as people frequently find comfort and satisfaction in a variety of ways. Coping strategies give people the tools they need to deal with life's ups and downs, from exercising and engaging in creative hobbies to getting social support and meditating. People can develop resilience and advance their mental health by adopting these various coping methods in their daily life.

Coping can include various activities, but Table 8[45] shows a few examples of coping activities.

Table 8.

Coping activities examples[45]

| Coping activities | Coping activities examples |

|---|---|

| Social coping activities | Stay connected with others to build a support network |

| Share your feelings and thoughts with someone you trust | |

| Participate in activities that bring you joy and fulfillment. Destressing with soothing activities, such as coloring and reading | |

| Lifestyle-related coping activities | Avoid harmful substances that may negatively impact your mental health |

| Eating healthy | |

| Sleeping adequately | |

| Personal and emotional activities for coping | Noticing tension and taking deep breaths to reduce it Catching negative thoughts and replacing them with healthy ones Setting and maintaining appropriate and healthy boundaries between you and others Finding things that make you grateful Creating little moments of joy each day Take two minutes to engage in mindfulness and appreciate the world around you |

Coping in the Indian Context

Spirituality is a widely accepted idea as coping in the Indian population. During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, people often used religious coping to deal with their routine day-to-day stress.[46] It entails faith and obedience to an all-powerful entity known as God, who rules over the universe and man's fate. It entails how people fulfill what they believe to be the purpose of their existence, as well as a search for the meaning of life and a sense of connectedness to the cosmos. The universality of spirituality transcends religion and culture. At the same time, spirituality is highly personal and unique to everyone. It is a holy domain of human experience. Love, honesty, patience, tolerance, compassion, a sense of detachment, faith, and hope are all attributes that spirituality fosters in man. Recently, there have been some reports indicating that several places. There have recently been some reports indicating that certain parts of the brain, primarily the nondominant one, are engaged in the appreciation and fulfillment of spiritual values and experiences.

Religion and spirituality[47,48]

Religion is spirituality institutionalized. As a result, there exist numerous religions, each with its own set of beliefs, practices, and teachings. They have several community-based worship programs. All of these religions have one thing in common: spirituality. Religions may lose their spirituality when they become oppressive institutions rather than agents of benevolence, peace, and harmony. They have the potential to divide rather than unite. History will tell us that this has happened on occasion. It is stated that more blood has been shed in the name of religion than in any other. Examples include medieval European holy wars, as well as modern-day religious-based terrorism and conflicts.

We must remember that religious organizations are designed to assist us in practicing spirituality in our daily lives. They require periodic revivals to establish spirituality.

Common spiritual practices for psychological health and well-being[47]

Practicing meditation, mindfulness, prayer, and profound introspection.

Spending time reading for reflection (literature, poetry, or scripture).

Singing or playing sacred music.

Being a part of a religious tradition.

Participating in religious ceremonies, rituals, symbolic activities, or worship.

Participating in pilgrimages or retreats.

Following a fasting regimen or other lifestyle habits.

Spending time outside admiring nature.

Enjoy being creative, such as through painting, sculpture, cooking, gardening, and so on.

Be of assistance to others.

Steps for improving spiritual well-being[47]

As you take steps to promote a good mental state, make sure you also take care of your spiritual health. Different tactics work for different people in different ways. You should do whatever makes you most at ease and pleased. Some suggestions for improving your spiritual health include the following:

Determine what makes you feel at peace, cherished, strong, and connected.

Devote a portion of your day to community service.

Read motivational books.

Consider meditating.

Go for a walk outside.

Pray, either alone or in a group.

Inclusion of yoga in daily living.

Participate in your preferred sport.

Schedule some alone (leisure) time for yourself.

Spirituality: Key points

Spirituality has been characterized as an expression of transcending means of realizing human potential.

Spirituality is a known psychological phenomenon that differs from religiosity and is applicable across cultures.

Significant study evidence suggests that spirituality is crucial in the treatment of psychological problems.

Spirituality: positive impact.

Spirituality can help your mental health in a variety of ways:

You might have a stronger feeling of purpose, tranquility, hope, and meaning.

You may feel more confident, self-esteem, and self-control.

It can assist you in making sense of your life events.

When you are sick, it can help you feel stronger and recover faster.

Those who belong to a spiritual community may receive additional help.

You may work on improving your relationships with yourself and others.

Many people suffering from mental illnesses find hope by speaking with a religious or spiritual leader. Some mental diseases might be characterized as moments when people doubt their worth or purpose in a way that makes them feel depressed. Incorporating spirituality into the therapy of mental health issues can be incredibly beneficial.

Spirituality: Negative impact

Some people may exploit emotionally sensitive people by claiming to encourage their spirituality. When emotionally susceptible, one is more likely to be persuaded to engage in risky behavior.

Measuring spirituality as a coping mechanism for mental well-being can be a complex task, as both spirituality and mental well-being are multifaceted concepts that can vary greatly from person to person.

Several standardized scales and questionnaires have been developed to measure spirituality and its relationship with mental well-being. Examples include the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness or Spirituality (BMMRS), the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS), and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). These scales typically consist of items that assess beliefs, practices, and experiences related to spirituality, as well as their impact on mental health. Table 9 shows a few examples of scales available for measuring spirituality in reference to mental well-being.

Table 9.

Few examples of spirituality scales in the Indian population

| Spirituality scales | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| WHO Quality of Life–Spirituality, Religiousness, and Personal Beliefs (WHOQOL-SRPB) | This module from the World Health Organization’s quality-of-life assessment includes questions related to spirituality and religiousness, and it can be used in conjunction with other well-being scales |

| Indian Mental Health Scale (IMHS) | While not exclusively focused on spirituality, the IMHS assesses mental health and well-being in the Indian context, which often includes spiritual dimensions due to cultural interconnections |

| Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS)—Indian Adaptation | The SWBS measures aspects of spiritual well-being, and an adaptation for the Indian context might include items that align with cultural and spiritual norms |

| Saraswathi or Spiritual Quotient Scale (SQS) | This scale focuses on assessing spiritual intelligence and well-being, considering Indian cultural and philosophical foundations |

Among these scales, WHOQOL-SRPB[21] has been validated in Hindi in India. Certain scales, such as Central Religiosity Scale and Duke University Religion Index (DUREL), have been adapted and validated in Hindi.[19,49]

SUMMARY

We explore various facets of mental health and well-being in this article. The study thoroughly examines the ideas of mental health and mental well-being, emphasizing the role that good mental health plays in promoting general wellness. The article dives into the complex concept of mental health, highlighting its benefits and how it enhances a person's QoL. The topic of measuring mental well-being is covered, putting light on the various tools and techniques used to rate and quantify this crucial aspect of humanity. The identification of variables that affect mental health and well-being is one of the main focuses of this study. The work emphasizes how biological, psychological, social, and environmental elements interact in complex ways to collectively determine a person's mental state.

This comprehensive analysis provides valuable insights into the holistic approach required to promote and maintain optimal mental health. Each individual employs a different coping strategy to deal with challenges and stressors. In our article, we explore and discuss various coping styles.

In conclusion, the article offers a comprehensive understanding of mental health and well-being, illustrating its conceptual foundations, determinants, and coping mechanisms.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization Constitution of the World Health Organization. 1946 Available from: https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/PDF/bd47/EN/constitution-en.pdf. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 10] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2004. Promoting mental health: Concepts, emerging evidence, practice: Summary report/a report from the World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation and the University of Melbourne. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42940 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mental Health. WHO Factsheet. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 10] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Cates A, Stranges S, Blake A, Weich S. Mental well-being: An important outcome for mental health services? Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207:195–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.158329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.APA Dictionary of Psychology. Available from: https://dictionary.apa.org/mental-health. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 10] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galderisi S, Heinz A, Kastrup M, Beezhold J, Sartorius N. Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry. 2015;14:231–3. doi: 10.1002/wps.20231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Underwood-Gordon LG. A working model of health: Spirituality and religiousness as resources: Applications to persons with disability. J Relig Disabil Health. 1999;3:51–71.. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGuire TG, Miranda J. New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health: Policy implications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:393–403. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Putnam R. Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. J Democracy. 1995;6:65–78.. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolcock M. Social capital and economic development: Towards a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory Soc. 1998;27:151–208.. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weich S, Brugha T, King M, McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, et al. Mental well-being and mental illness: Findings from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey for England 2007. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:23–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.091496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crinson I, Martino L. 2017 Available from: https://www.healthknowledge.org.uk/public-health-textbook/medical-sociology-policy-economics/4a-concepts-health-illness/section2/activity3. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 05] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seligman ME. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life. World Health Organization. Available from: https:/www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/ [Archived from the original on 2020 May 15. Retrieved 2020 May 22] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Furberg CD, Elinson J. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54:908–13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(84)80232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindstrom B. Quality of life – a model for evaluating health for all: conceptual considerations and policy implications. Sozial und Preventivmedizin. 1992;37:301–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01299136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felce D, Perry J. Quality of life: its definition and measurement. Research in developmental disabilities. 1995;16:51–74. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(94)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skevington SM. Quality of Life. In Encyclopedia of Stress (Second Edition), 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grover S, Dua D. Hindi Translation and Validation of Scales for Subjective Well-being, Locus of Control and Spiritual Well-being. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021;43:508–15. doi: 10.1177/0253717620956443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxena S, Chandiramani K, Bhargava R. WHOQOL-Hindi: a questionnaire for assessing quality of life in health care settings in India. World Health Organization Quality of Life. Natl Med J India. 1998;11:160–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grover S, Shah R, Kulhara P. Validation of Hindi Translation of SRPB Facets of WHOQOL-SRPB Scale. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:358–63. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.122225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huppert FA. Psychological well-being: Evidence regarding its causes and consequences. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01008.x Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2009;1:137–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Compton MT, Shim RS. The social determinants of mental health. Available from: https://focus.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.focus.20150017. Published Online 2015 Oct 22. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation . Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Social determinants of mental health. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241506809. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 10] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arumugam S. Strategies toward building preventive mental health. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2019;35:164–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Public Health reports- Joint Strategic Needs Assessment. Mental wellbeing. Available from: https://jsna.bradford.gov.uk/Mental%20wellbeing.asp. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 10] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khanna P, Aeri B. Risk factors for mental health disorders: From conception till adulthood. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328889507.2017 . [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alegría M, NeMoyer A, FalgàsBagué I, Wang Y, Alvarez K. Social determinants of mental health: Where we are and where we need to go. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20:95. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0969-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.10th. Wolters and Kluwer Publishing; Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry; p. 4571. [Google Scholar]

- 30.7th. Oxford University Press; Coping Mechanism, Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry; p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Algorani EB, Gupta V. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Coping mechanisms. [Updated 2023 Apr 24] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:745–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rekhi S, Davis T. Coping mechanisms: Definition, examples, and types. Available from: https://www.berkeleywellbeing.com/coping-mechanisms.html. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 10] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burns DD, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Coping styles, homework compliance, and the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:305–11. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyerson J, Gelkopf M, Eli I, Uziel N. Stress coping strategies, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction amongst Israeli dentists: A cross-sectional study. Int Dent J. 2022;72:476–83. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stallman HM, Beaudequin D, Hermens DF, Eisenberg D. Modelling the relationship between healthy and unhealthy coping strategies to understand overwhelming distress: A Bayesian network approach. J Affect Disord Rep. 2021;3:100054. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP, et al. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol Bull. 2017;143:939–91. doi: 10.1037/bul0000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coppens CM, de Boer SF, Koolhaas JM. Coping styles and behavioural flexibility: Towards underlying mechanisms. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:4021–8. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koolhaas JM, de Boer SF, Coppens CM, Buwalda B. Neuroendocrinology of coping styles: Towards understanding the biology of individual variation. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010;31:307–21. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Millacci TS, Lancia G. Healthy coping: 24 mechanisms and skills for positive coping. Available from: https://positivepsychology.com/coping. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 10] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kato T. Frequently used coping scales: A meta-analysis. Stress Health. 2015;31:315–23. doi: 10.1002/smi.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janghel G, Shrivastav P. Coping Behavior Assessment Scale (Indian Adaptation): Establishing Psychometrics Properties, Int J Indian Psychol 2017;4. DIP: 18.01.077/20170403. DOI: 0.25215/0403.077. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shah R, Grover S, Kulhara P. Coping in residual schizophrenia: Re-analysis of ways of Coping checklist. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145:786–95. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1927_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.https://www.npcindia.com/Psychological-Test/STRESS-COPING-STRATEGIES-SCALE/1000022/1 National Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peterson T. Coping skills for mental health and wellbeing, healthy place. (2015 Dec 23) Available from: https://www.healthyplace.com/other-info/mental-health-newsletter/coping-skills-for-mental-health-and-wellbeing. [Last accessed on 2023 Jul 21] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fatima H, Oyetunji TP, Mishra S, Sinha K, Olorunsogbon OF, Akande OS, et al. Religious coping in the time of COVID-19 pandemic in India and Nigeria: Finding of a cross-national community survey. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68:309–15. doi: 10.1177/0020764020984511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Royal College of Psychiatry Spirituality and Mental health. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/treatments-and-wellbeing/spirituality-and-mental-health. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 10] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verghese A. Spirituality and mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:233–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.44742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dua D, Scheiblich H, Padhy SK, Grover S. Hindi Adaptation of Centrality of Religiosity Scale. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120683 Religions. 2020;11:683. [Google Scholar]