Abstract

TFIID is a multiprotein complex consisting of the TATA box binding protein and multiple tightly associated proteins (TAFIIs) that are required for transcription by selected activators. We previously reported cloning and partial characterization of human TAFII130 (hTAFII130). The central domain of hTAFII130 contains four glutamine-rich regions, designated Q1 to Q4, that are involved in interactions with the transcriptional activator Sp1. Mutational analysis has revealed specific regions within the glutamine-rich (Q1 to Q4) central region of hTAFII130 that are required for interaction with distinct activation domains. We tested amino- and carboxyl-terminal deletions of hTAFII130 for interaction with Sp1 activation domains A and B (Sp1A and Sp1B) and the N-terminal activation domain of CREB (CREB-N) by using the yeast two-hybrid system. Our results indicate that Sp1B interacts almost exclusively with the Q1 region of hTAFII130. In contrast, Sp1A makes multiple contacts with Q1 to Q4 of hTAFII130, while CREB-N interacts primarily with the Q1-Q2 hTAFII130 subdomain. Consistent with these interaction studies, overexpression of the Q1-to-Q4 region in HeLa cells inhibits Sp1- but not VP16-mediated transcriptional activation. These findings indicate that the Q1-to-Q4 region of hTAFII130 is required for Sp1-mediated transcriptional enhancement in mammalian cells and that different activation domains target distinct subdomains of hTAFII130.

The role of TAFs in transcriptional regulation has been intensely studied in vitro as well as in vivo over the past several years (reviewed in references 3, 5, 32, and 40). Results from the early in vitro studies have revealed that TAFs play an essential role in mediating transcriptional activation by a variety of activators, and as such, they are considered coactivators. TAFs have been shown to directly contact selected activators, and these interactions are required for activated transcription in vitro. In vivo studies conducted with yeast, however, have suggested that TAFs may not be required at all gene promoters to regulate transcription (29, 47). Further work has revealed that they may be essential for transcription of selected genes that govern the cell cycle progression in yeast (1, 48). Studies carried out with the Drosophila embryo have also demonstrated that specific TAF-activator interactions are required for activation of selected genes in vivo (41).

hTAFII130 is a human homolog of Drosophila TAFII110 (dTAFII110), the first TAF demonstrated to possess coactivator activity (6, 20). Unlike other TAFs, hTAFII130 and dTAFII110 display limited sequence similarities (26, 45). hTAFII130 is also unique among TAFs in that no apparent homolog exists in yeast. Furthermore, hTAFII130 may be the product of a member of a gene family, since at least one additional related but distinct gene product, hTAFII105, has been found in the TFIID complex purified from differentiated B cells (11).

Protein-protein interaction assays as well as in vitro transcription assays have provided evidence for direct interaction of activators with one or more TAFs in the TFIID complex (6, 17, 20, 21). Significantly, such studies have suggested that different activators may interact selectively with specific TAF proteins. For example, glutamine-rich activation domains of Sp1 and the cyclic AMP-responsive transcription factor CREB bind hTAFII130 (45) and dTAFII110 (14, 20), the activation domains of VP16 and p53 bind hTAFII32 (23, 24) and dTAFII40 (17, 23, 24, 46), the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product binds hTAFII250 (42), and the estrogen receptor interacts with hTAFII30 that is present in a subset of TFIID complex (21). These interactions are thought to participate in the recruitment and/or stabilization of the preinitiation complex at the promoter, leading to increased levels of transcription. TAFs may also play a role in positioning TFIID onto promoter DNA, in conjunction with TFIIA. In the context of promoter-bound TFIID, site-specific photo-cross-linking of hTAFII130 to the adenovirus major late promoter was observed (31). Furthermore, Drosophila TAFII60 was shown to bind to the conserved downstream core promoter element (2), while a recent study indicated that yeast TAFII145 functions to recognize selected core promoters (43). It is evident from these studies that TAFs serve multiple functions as a coactivator and a promoter selectivity factor. In addition, a regulatory function has been suggested for TAFs, as recent findings indicate that TAFII250 contains protein kinase (10) and histone acetyltransferase (28) activities. As integral components of the preinitiation complex, TAFs also participate in protein-protein interactions with components of the general transcription machinery (3).

As a step towards understanding the function of hTAFII130, we have identified the regions of several activators that interact with hTAFII130. We then compared and contrasted these activator-TAF interactions by using individual activators and deletions of hTAFII130. This analysis of TAF-activator interactions should provide an understanding of how multiple activators cooperate to activate transcription by targeting the same TAF protein in the general transcription machinery.

The human transcription factor Sp1 contains glutamine-rich activation domains, A and B (9). Using protein-protein interaction assays in yeast, we have determined the regions within hTAFII130 required for interaction with the A and B activation domains of Sp1 as well as the N-terminal activation domain of CREB. The deletion analyses suggest that different activation domains interact with distinct subdomains of hTAFII130. Furthermore, transient expression of the central portion of hTAFII130 reveals domain-specific inhibition of Sp1-mediated transcription in HeLa cells. We also show that Sp1B mutants that fail to interact with hTAFII130 in the yeast two-hybrid assay display reduced transcription in transient-transfection assays in cultured cells. These results suggest that hTAFII130 is likely to serve as a target for multiple activators in mammalian cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of C-terminal and N-terminal deletion derivatives of hTAFII130.

All hTAFII130 derivatives used in this study were cloned into the pEG202 vector downstream of the LexA DNA binding domain (DBD) (18) and in frame with the introduced hemagglutinin antigen (HA) tag. For construction of C-terminal deletion derivatives, pAS-hTAFII130 (residues 270 to 947) was linearized at the 3′ end of the hTAFII130 cDNA sequence and digested with nuclease Bal 31 at 30°C for different times as described previously (37). Each deletion pool was then digested with EcoRI (upstream of the HA tag in pAS [12]), and the DNA fragments were purified and ligated to pEG202 digested with EcoRI and BamHI (blunt ended). For construction of N-terminal deletion derivatives, pAS-hTAFII130N/C (residues 270 to 700) (45) was linearized with EcoRI at the 5′ end of the insert sequence and digested with nuclease Bal 31 at 25°C, followed by digestion with SalI. The DNA fragments were gel purified and subcloned into NcoI (blunt ended) and SalI sites in pEG202 downstream of the LexA DBD and the introduced HA tag sequence. All constructs were sequenced across the cloning junction to select for the deletions that were in frame with the LexA DBD.

Yeast two-hybrid methods.

The pEG202-hTAFII130 deletion derivatives and the pJG4-5 vector (18) constructs encoding the B42 transcriptional activation domain fused to Sp1A (residues 83 to 262), Sp1B (residues 263 to 542) (a gift of Grace Gill, Harvard Medical School), or CREB-N (residues 3 to 296) were cotransformed into yeast strain EGY48 as described previously (20). Mutants of the Sp1B and Sp1B-c (residues 421 to 542) activation domains, cloned into the pGAD vector (16) (gifts of G. Gill), were cotransformed into yeast strain W303 with pEG202-hTAFII130N/C (residues 270 to 700) as described previously (45). The transformed yeast cells were grown on a selection medium containing X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) for qualitative detection of the β-galactosidase activity. For quantitative β-galactosidase assays, transformed yeast cells were grown in a liquid selection medium for 24 to 36 h before induction (overnight), and β-galactosidase activity was measured in triplicate as described previously (15). Each experiment was repeated a minimum of three times. The expression of the fusion proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody.

Transient-transfection assays with cultured mammalian cells.

The pSG424 vector (36) constructs carrying the Gal4 DBD (residues 1 to 147) fused to Sp1A/B (residues 83 to 621), Sp1B (residues 263 to 542), Sp1B-c (residues 421 to 542), and their mutant derivatives were generous gifts of G. Gill (16). COS cells were transfected with a Gal4-Sp1 fusion construct and a UASp59RLG reporter plasmid (a gift of David Ron, New York University Medical Center) containing two copies of the Gal4 binding site upstream of the minimal angiotensinogen promoter (35), using the DEAE-dextran method as described previously (37). Transient transfections in HeLa cells were performed by using Lipofectamine (Life Technologies, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. Quantities of the cytomegalovirus (CMV)-driven expression plasmid DNA containing subdomains of HA-ΔNhTAFII130 (amino acids 1 to 947) (45) were optimized for comparable levels of protein expression (see Fig. 5) as determined by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody and an ECL chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Life Science). Each transfection in HeLa cells included a fixed amount of CMVhTAFII130 derivative and/or empty CMV vector as well as CMVlacZ (0.15 μg), 5xGal4-E1b-luciferase reporter (44) (0.5 to 0.75 μg), and one of the following activators in the pSG424 vector: Gal4-Sp1A/B (0.25 μg), Gal4-Sp1B (0.25 μg), or Gal4-VP16 (0.05 μg). The HA-tagged CMVhTAFII130 derivatives utilized were as follows: wild-type hTAFII130 (residues 1 to 947) (2 μg), hTAFII130N/C (residues 270 to 700) (1.25 to 3 μg), derivative 4 (residues 270 to 700/Δ454-525) (3 μg), derivative 10 (residues 270 to 409) (0.25 μg), derivative 13 (residues 270 to 350) (2 μg), N334 (residues 1 to 334) (0.1 μg), N288 (residues 1 to 288) (0.09 μg), and N297 (residues 1 to 297) (0.075 μg). At 40 h posttransfection, cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline and harvested in 1× Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega). Luciferase activity was quantified in a reaction mixture containing 25 mM glycylglycine (pH 7.8), 15 mM MgSO4, 1 mM ATP, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. A Lumat LB 9507 luminometer (EG&G Berthold) was used to measure activity with 1 mM d-luciferin (Analytical Luminescence Laboratory) as the substrate. All transfections were performed in duplicate a minimum of three times.

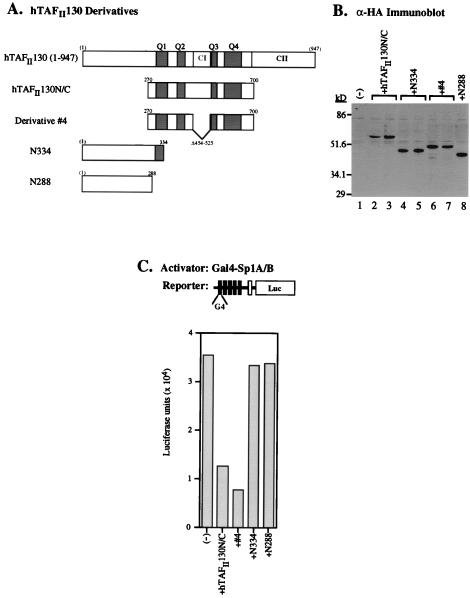

FIG. 5.

Expression of the central domain of hTAFII130 results in domain-specific inhibition of Gal4-Sp1-mediated transcriptional activation in HeLa cells. (A) Plasmid constructs that express subdomains of hTAFII130 (tagged with HA) are depicted schematically. Derivative 4 contains the same hTAFII130 sequence as in Fig. 1. Constructs N334 and N288 contain the N-terminal 334 and 288 amino acids of hTAFII130, respectively. (B) A representative anti-HA (α-HA) Western immunoblot of cell lysates used in the luciferase assay, demonstrating comparable levels of protein expression of transfected HA-hTAFII130 derivatives. Lysates of HeLa cells transfected with no hTAFII130 derivative (lane 1), hTAFII130N/C (lanes 2 and 3), N334 (lanes 4 and 5), derivative 4 (lanes 6 and 7), and N288 (lane 8) are shown. (C) Luciferase activity in the lysates of HeLa cells (as shown in panel B) transfected with the reporter construct, the indicated hTAFII130 derivative, and Gal4-Sp1A/B (residues 83 to 621).

RESULTS

The first glutamine-rich domain (Q1) within the central region of hTAFII130 is sufficient for interaction with activation domain B of Sp1.

Using the yeast two-hybrid system, we previously found that the central region (residues 270 to 700) of hTAFII130 (designated hTAFII130N/C) was sufficient to interact with activation domain B of Sp1 (Sp1B) (45). To further define subregions of the hTAFII130 central domain for interaction with Sp1B, we generated a series of N-terminal and C-terminal deletions of hTAFII130. Deletion mutants of hTAFII130 were subcloned into a yeast plasmid downstream of the LexA DBD/HA tag sequence and tested for their ability to interact with the Sp1B domain.

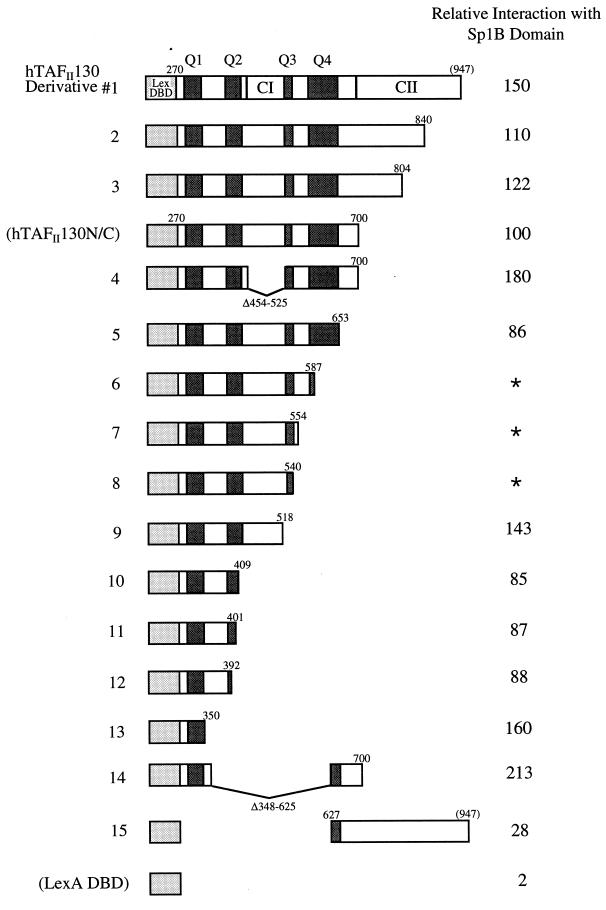

The central region of hTAFII130 contains four glutamine-rich regions (designated Q1 to Q4) (see the legend to Fig. 1). Figure 1 shows the results of the interaction assay with Sp1B and the C-terminal deletion mutants of hTAFII130. Surprisingly, the hTAFII130 C-terminal deletion mutants lacking the Q2, Q3, and Q4 glutamine-rich regions had little effect on the interaction with Sp1B (derivatives 1 to 12). hTAFII130 containing only the Q1 region (derivative 13) was found to be sufficient for interaction with Sp1B. Deletion of Q1 (derivative 15) reduced the interaction to 28%. The central region of hTAFII130 contains a sequence (CI, residues 449 to 528) that has a high degree of similarity with dTAFII110 (45). We tested a derivative lacking most of the CI sequence (derivative 4) and found that the conserved sequence CI was not required for interaction of hTAFII130 with Sp1B. Although derivatives 6 to 8 were found to be weakly active in the absence of Sp1B, they still showed significant interactions with Sp1B, as the β-galactosidase activity measured was significantly enhanced over the basal levels in the presence of Sp1B (data not shown). The expression of all mutant hTAFII130 proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting of the yeast cell lysates with anti-HA antibody (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Carboxyl-terminal deletion analysis of hTAFII130 reveals the Q1 region to be important for interaction with Sp1B. Derivatives of hTAFII130 fused to the LexA DBD in pEG202 are shown schematically. Yeast (EGY48) was transformed with pEG202-hTAFII130 fusion constructs and an Sp1B (residues 263 to 542) fusion construct in pJG4-5 along with the reporter plasmid. The percent β-galactosidase activity relative to that of hTAFII130N/C in each transformant is represented at the right. Asterisks indicate hTAFII130 derivatives that activate weakly in the absence of Sp1B. All assays were done in triplicate. Expression of hTAFII130 deletion mutants and Sp1B was confirmed by immunoblotting (data not shown). Q1, residues 300 to 347, 25% glutamine content; Q2, residues 388 to 419, 25% glutamine content; Q3, residues 528 to 550, 30% glutamine content; Q4, residues 580 to 651, 19% glutamine content. The numbering of the amino acid residues is as in reference 45.

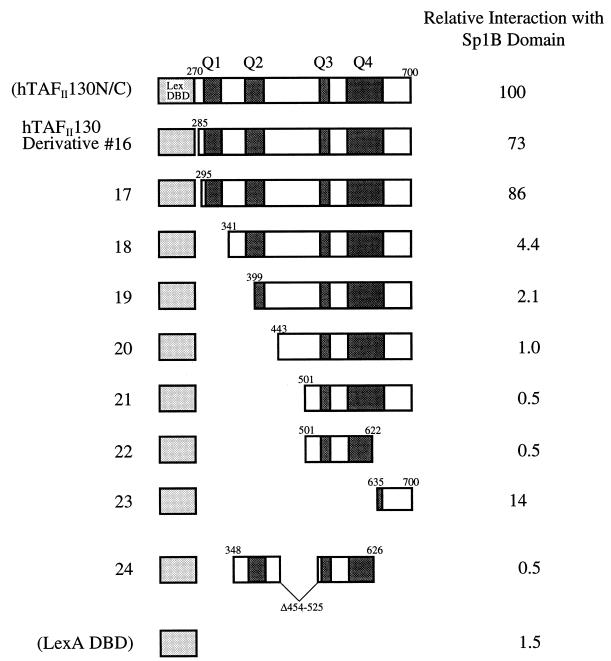

To test whether other glutamine-rich regions of hTAFII130 (Q2, Q3, and Q4) could functionally substitute for Q1, we tested a series of N-terminal deletion mutants of hTAFII130 in the yeast two-hybrid system. As shown in Fig. 2, deletion of a region containing Q1 (derivative 18) severely decreased (to 4.4%) the ability of hTAFII130 to interact with Sp1B even in the presence of other glutamine-rich regions. These results suggest that a domain within amino acids 270 to 350 of hTAFII130 (derivative 13) contains the sequences important for interaction with Sp1B and that the other domains (Q2, Q3, and Q4) cannot functionally substitute for Q1.

FIG. 2.

Amino-terminal deletion analysis of hTAFII130, showing that the Q1 region of hTAFII130 is essential for interaction with Sp1B. The pEG202 plasmids expressing the N-terminal deletions of hTAFII130N/C were cotransformed with pJG4-5-Sp1B into yeast (EGY48) as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The β-galactosidase activity relative to that of hTAFII130N/C (set to 100%) is shown at the right.

Different activators interact with distinct regions of hTAFII130.

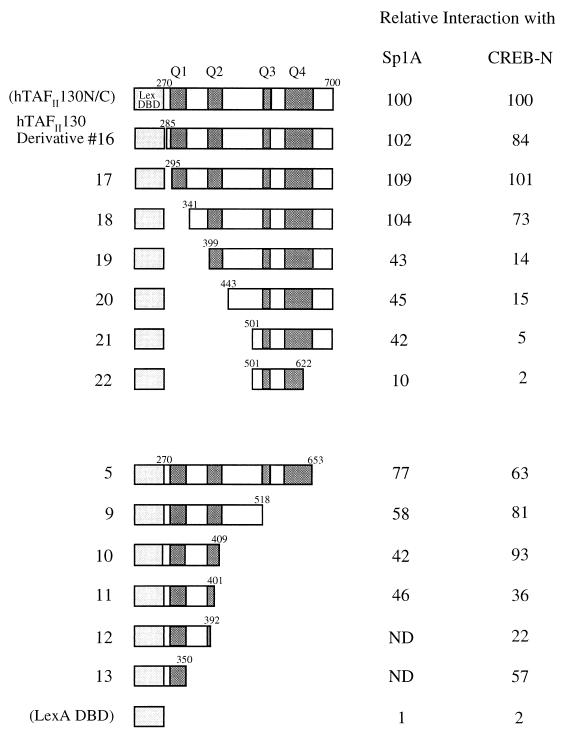

The central portion of hTAFII130, like dTAFII110, also interacts with activation domain A of Sp1 (Sp1A) and the N-terminal activation domain of CREB (CREB-N) (14, 20, 45). We wanted to test whether these activators interacted with a common region or distinct regions within hTAFII130. The hTAFII130 deletion mutants described above were tested for their interaction with Sp1A and CREB-N by using the yeast two-hybrid system. As shown in Fig. 3, deletion of a region containing Q1 (derivative 18) of hTAFII130 did not impair its interaction with Sp1A. This is in contrast to the result obtained with Sp1B (compare results with derivative 18 in Fig. 2 and 3), where deletion of Q1 virtually eliminated interaction. hTAFII130 lacking Q1 and a portion of Q2 (derivative 19) retained 43% of the activity with Sp1A, whereas the same construct interacted poorly with Sp1B (2.1%) (derivative 19 in Fig. 2). Interestingly, derivative 10 (Fig. 3), containing Q1 and Q2, interacted with Sp1A (42%) as well as derivative 21 (Fig. 3), which contained Q3 and Q4 (42%). This finding suggests that unlike Sp1B, Sp1A makes multiple contacts with hTAFII130. We also observed that Sp1A interacted more strongly with hTAFII130 than did Sp1B (30 to 60% higher activity) (data not shown). Sp1A was also shown to interact with the N-terminal 308 amino acids of dTAFII110, which exclude most of the highly conserved domain CI (20). Thus, dTAFII110 and hTAFII130 may have additional structural similarities, not apparent in the primary amino acid sequence, that permit their interactions with Sp1A.

FIG. 3.

Different activators interact with distinct regions within hTAFII130. pEG202-hTAFII130 derivatives were cotransformed into yeast with pJG4-5 plasmids expressing either Sp1A (residues 83 to 262) or CREB-N (residues 3 to 296) along with the reporter plasmid. All other conditions were as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The hTAFII130 derivatives shown have the same numbers as in Fig. 1 and 2. The β-galactosidase activity of hTAFII130N/C measured with pJG4-5–activator fusions was taken as 100%. ND, not determined.

The N-terminal glutamine-rich activation domain of CREB, on the other hand, preferentially interacted with a region encompassing Q1 and Q2 of hTAFII130. Unlike the case for Sp1B, deletion of Q1 did not impair the interaction of hTAFII130 with CREB-N (compare results with derivative 18 in Fig. 2 and 3); however, deletion of the sequences between Q1 and Q2 (derivative 19; Fig. 3) reduced the activity with CREB-N to 14%. Furthermore, derivatives 11 to 13, which contained Q1 and a partial Q2, interacted with CREB-N at reduced levels, suggesting additional interactions between Q2 and CREB-N. Interestingly, the C-terminal half of hTAFII130, containing Q3 and Q4, did not interact efficiently with CREB-N, unlike with Sp1A (derivatives 20 and 21 in Fig. 3). Based on the hTAFII130 N-terminal (derivatives 18 and 19) and C-terminal (derivatives 10 and 12) deletion constructs, a region involved in interaction with CREB-N appeared to encompass Q1 and Q2. This is in contrast to the interactions of Sp1A with hTAFII130 (Q1 to Q4) and of Sp1B with hTAFII130 (Q1). Thus, different activation domains appear to interact with distinct subdomains of hTAFII130.

The ability of mutants of Sp1B to interact with hTAFII130 correlates with their ability to activate transcription in mammalian cells.

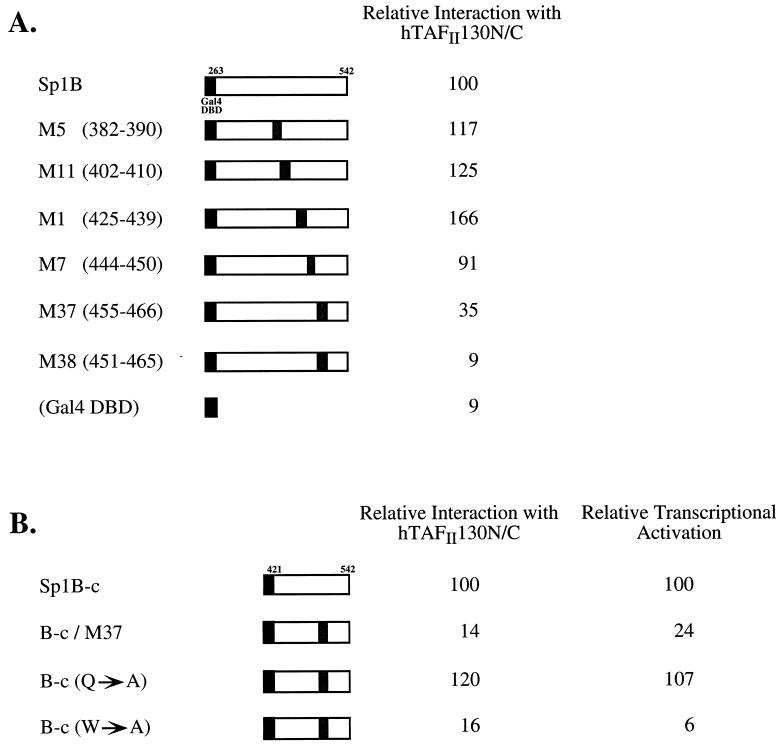

To demonstrate that Sp1B-hTAFII130 interaction correlates with Sp1’s ability to activate transcription, we tested previously characterized mutants of Sp1B (16) in the yeast two-hybrid system with hTAFII130 (Fig. 4). Linker substitution mutations in the carboxyl-terminal half of the Sp1B domain (M37 and M38) resulted in a 65 to 91% decrease in the ability of Sp1B to interact with hTAFII130 (Fig. 4A). Although the C-terminal subdomain of Sp1B (Sp1B-c) was sufficient to interact with hTAFII130, substitution mutants B-c/M37 and B-c(W→A) interacted poorly with hTAFII130 (Fig. 4B), supporting the above-described finding that the C-terminal half of Sp1B contains the sequences required for interaction with hTAFII130. As with dTAFII110 (16), the replacement of two glutamines and one asparagine with alanine residues did not affect the interaction of the mutant B-c(Q→A) with hTAFII130.

FIG. 4.

The C-terminal subdomain of Sp1B interacts with hTAFII130 and activates transcription in mammalian cells. (A) Linker substitution mutants of Sp1B (16) were tested for interaction with hTAFII130 in the yeast two-hybrid assay. Yeast (W303) was cotransformed with pEG202-hTAFII130N/C and Sp1B mutants in pGAD. The percent β-galactosidase activity was measured relative to that of the wild-type Sp1B. (B) Substitution mutants of Sp1B-c were tested for interaction with hTAFII130 in the yeast two-hybrid assay. Sp1B-c mutants in pGAD were transformed into yeast along with pEG202-hTAFII130N/C. The percent β-galactosidase activity was measured relative to that of the wild-type Sp1B-c. To determine the transcriptional activities of these Sp1B-c mutants, plasmids expressing the indicated Sp1B mutants fused to the Gal4 DBD were transfected into COS cells along with a Gal4-driven luciferase reporter gene and assayed for activation of transcription. The resulting luciferase activity was expressed relative to the activity of the wild-type Sp1B-c domain. All assays were done in triplicate.

To correlate the ability of the Sp1B derivatives to interact with hTAFII130 with their ability to activate transcription in mammalian cells, we tested the expression of a luciferase reporter gene containing the Gal4 binding sites by cotransfection of plasmids expressing Gal4–Sp1B-c or its mutant derivatives into COS cells. Gal4–Sp1B-c efficiently activated the reporter gene (90 to 100% of the activation by Gal4-Sp1B [data not shown]), whereas Gal4-DBD showed 5 to 10% of the activity of Gal4–Sp1B-c (data not shown). The linker substitution mutation significantly compromised the activation of the reporter gene (Sp1B-c/M37) (24%), as did the W→A substitution mutation in Sp1B-c (6%) (Fig. 4B). By contrast, Sp1B-c bearing the Q→A mutation retained activity close to that of the wild type. Thus, Sp1B-c mutants that interacted poorly with hTAFII130 in the yeast two-hybrid assay also failed to direct efficient transcription of the reporter gene in mammalian cells.

Transient expression of the hTAFII130 central domain selectively interferes with Sp1-mediated activation of the reporter gene in HeLa cells.

To further demonstrate the role of hTAFII130 in mediating transcriptional activation by Sp1, we performed transient-transfection assays in HeLa cells with Sp1-responsive luciferase reporter constructs. HeLa cells were cotransfected with the expression plasmids carrying HA-tagged subdomains of hTAFII130 as shown schematically in Fig. 5A. The amount of DNA transfected was adjusted so as to achieve comparable levels of protein expression, as shown in the representative anti-HA immunoblot (Fig. 5B). Cotransfection of a reporter construct bearing five Gal4 binding sites with a plasmid expressing the Gal4-Sp1A/B activator directed a high level of luciferase activity, which was decreased three- to fourfold in the presence of two hTAFII130 subdomains, hTAFII130N/C and derivative 4 (Fig. 5C). By contrast, constructs N334 and N288, expressing the N-terminal subdomains of hTAFII130, had no detectable effect on Gal4-Sp1A/B-mediated transcription. The finding that a deletion of the conserved region CI (derivative 4) did not affect the ability of the hTAFII130 central domain to inhibit transcription is in agreement with the result from the yeast two-hybrid system in which the ΔCI construct remained capable of interacting with Sp1 (derivative 4 in Fig. 1). Additionally, construct N334, expressing a portion of Q1, did not inhibit activation by Sp1A/B, suggesting that additional Q regions are necessary for full inhibition of Sp1A/B.

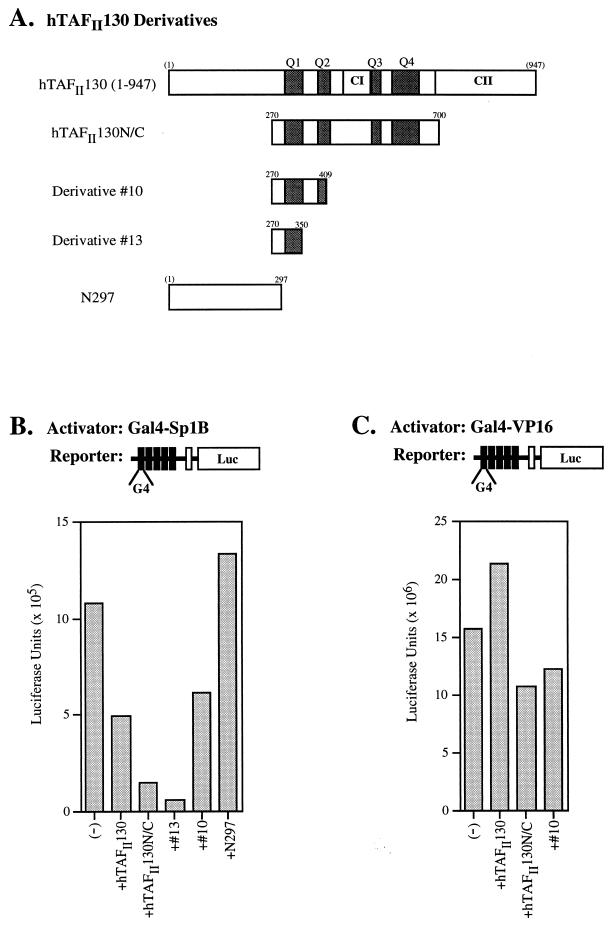

We next tested the effects of transiently expressing the wild-type hTAFII130 cDNA (amino acids 1 to 947) as well as derivatives carrying a subset of Q-rich regions (Fig. 6A) on the reporter gene activated by Gal4-Sp1B. Derivatives 10 and 13 contain the same hTAFII130 sequences as those shown to interact with Sp1B in the yeast two-hybrid system (derivatives 10 and 13 in Fig. 1). We found that wild-type hTAFII130 (amino acids 1 to 947), as well as derivatives 10 and 13, decreased Gal4-Sp1B-mediated reporter gene activity but that the N-terminal subdomain N297 did not (Fig. 6B). To demonstrate that the squelching effect was specific for Sp1B, the Gal4-driven reporter gene was cotransfected with a plasmid expressing Gal4-VP16. Figure 6C shows that coexpression of hTAFII130 subdomains had little effect on the Gal4-VP16-mediated activation of transcription, suggesting that the hTAFII130 central domain had a specific effect on Sp1-mediated transcription. In these experiments, hTAFII130N/C, derivative 10, and N297 were expressed at comparable levels, whereas hTAFII130 (amino acids 1 to 947) and derivative 13 were expressed at lower levels (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with different concentrations of activator proteins; thus, domain-specific transcriptional inhibition by hTAFII130 was observed over a broad range of the reporter gene activity (data not shown). Taken together, the TAF-activator interaction studies carried out with yeast and cultured mammalian cells indicate that different activators bind distinct subdomains of hTAFII130 and suggest a mechanism for coordinated action of multiple promoter-bound activators on the general transcription machinery.

FIG. 6.

Wild-type hTAFII130 and subdomains of hTAFII130 that interact with Sp1B domain inhibit transcriptional activation by Gal4-Sp1B (residues 263 to 542) but not by Gal4-VP16 in HeLa cells. (A) Schematic representation of hTAFII130 derivatives used in the experiment. hTAFII130 (1-947), wild-type hTAFII130 carrying amino acids 1 to 947. Derivatives 10 and 13 contain the same hTAFII130 sequences as those tested in the yeast two-hybrid assay (depicted in Fig. 1). (B and C) Luciferase activity in the lysates of HeLa cells transfected with the reporter construct, the indicated hTAFII130 derivative, and Gal4-Sp1B (B) or Gal4-VP16 (C) was determined. Although not shown in panel C, N297 was also tested with Gal4-VP16 in a separate experiment, and like other hTAFII130 derivatives, it was found to have no significant effect on the transcriptional activation by Gal4-VP16.

DISCUSSION

Interactions between multiple activation domains and hTAFII130.

Recent studies on transcriptional activators that bind to enhancers to form a stereospecific enhanceosome complex have revealed multiple protein-protein contacts between DNA-bound activators, as well as between activators and their target proteins. It has been proposed that such extended networks of protein-protein interactions contribute to transcriptional synergy (reviewed in reference 4). For example, transcriptional activators bound to beta interferon enhancer appear to contact multiple regions of their target protein CBP (CREB-binding protein) or components of the basal transcriptional machinery to enhance transcription (22, 27). A previous study has already established that interactions between activators with multiple members of the general transcription machinery lead to synergistic transcription (7). It has also been shown with the Drosophila hunchback promoter that specific activator-TAF interactions are sufficient for simple as well as synergistic activation by multiple enhancer factors (38, 39). Thus, transcriptional synergy may be achieved by multiple protein-protein interactions between single or multiple domains of activators and single or multiple surfaces of their target proteins.

The results presented in this paper suggest that distinct subdomains of hTAFII130 might also serve as targets for multiple transcriptional activation domains. Using N- and C-terminal deletion mutants of the hTAFII130 central domain, we demonstrate that specific regions within this domain are required for interaction with the glutamine-rich activation domains A and B of Sp1 and CREB. The central domain of hTAFII130 contains four glutamine-rich sequences (Q1 to Q4) flanking region CI, a sequence highly conserved between dTAFII110 and hTAFII130. CI is not required for interactions with these activation domains, suggesting that structural determinants within the nonconserved segment of hTAFII130 mediate TAF-activator interactions. Interestingly, calculation of the percent glutamine content for the central domain (Q1 to Q4) of hTAFII130 reveals 17% glutamine outside region CI and 5% within region CI. For dTAFII110, similar analysis reveals a 12.5% glutamine content outside region CI and 6% within region CI, whereas hTAFII105 maintains a rather low (6%) glutamine content throughout the entire central domain, including region CI. Previous work with dTAFII110 has shown that the amino-terminal 308 amino acid residues that exclude most of region CI are also sufficient to interact with Sp1A (20), in agreement with our finding that the conserved region is not required for TAF-Sp1 interactions. We are currently generating point mutations within the hTAFII130 central domain to further dissect these TAF-activator interactions.

Although the majority of hTAFII130 derivatives fused to the LexA DBD were transcriptionally inactive in yeast, C-terminal truncations that fell between residues 540 and 587 (Fig. 1) were found to be weakly active in the absence of Sp1. Interestingly, further removal of part of the highly conserved CI sequence from the truncated hTAFII130 derivatives abolished self-activation (derivative 9 [Fig. 1]), suggesting that self-activation might have been caused by unmasking of the intact CI sequence. Although the function of CI is yet to be determined, the C-terminal conserved region CII in dTAFII110 is required for interaction with dTAFII250, dTAFII30α, and TFIIA-L (41, 45, 49), suggesting that CI might also serve a conserved function. Perhaps unmasking of the hTAFII130 CI sequence in yeast may have permitted interaction(s) with a conserved domain of a yeast TAF or a general transcription factor, leading to tethering of the transcription machinery to the promoter and activation of the reporter gene (34).

Functional significance of the Sp1-hTAFII130 interactions.

We have also observed that Sp1A interacted more strongly with hTAFII130 than did Sp1B in the yeast two-hybrid assay and in vitro binding assay (data not shown), similar to the observations made with dTAFII110 (20). Perhaps multiple contacts made between Sp1A and subdomains of hTAFII130 may explain why Sp1A functions as a more potent activator than Sp1B in transient-transfection studies (9). Since distinct regions of hTAFII130 are targeted by Sp1A and B domains, these two domains in full-length Sp1 are likely to interact cooperatively with hTAFII130 in vivo. Indeed, it has been shown that domains A and B, in addition to the carboxyl-terminal domain D, are all required for synergistic activation by Sp1 (33). Interestingly, the carboxyl-terminal domain of Sp1 that includes the zinc finger DBD and domain D has been shown to interact with hTAFII55 (8). Thus, binding of Sp1 to different TAFs as well as different regions of the same TAF could result in cooperative interactions between Sp1 and TFIID and strong activation of transcription by the full-length Sp1 protein. It is worth noting that CREB also possesses two discrete activation domains, the kinase-inducible domain and the glutamine-rich activation domain Q2, both of which have been shown to be required for signal-dependent activation of transcription in vitro (30). The phosphorylation-dependent kinase-inducible domain has been shown to interact with RNA polymerase II via the coactivator CBP, and the Q2 activation domain appears to recruit TFIID via hTAFII130. These experiments suggest that multiple interactions between an activator and the components of the transcriptional machinery are required for full activity of CREB.

It has been demonstrated that the carboxyl-terminal half of the Sp1B domain (Sp1B-c) is sufficient for interaction of Sp1B with dTAFII110 and that mutants of Sp1B-c that failed to interact with dTAFII110 also activated transcription at reduced levels in Drosophila Schneider cells (16). We have shown in the present study that the same mutants of Sp1B-c interacted poorly with hTAFII130 and were compromised for their ability to activate transcription in mammalian cells. Thus, both in insect cells and in mammalian cells we find a correlation between the ability of Sp1 to interact with hTAFII130 or dTAFII110 and its ability to activate transcription. Moreover, despite the differences in the primary amino acid sequences between the hTAFII130 central domain and the amino terminus of dTAFII110, both proteins appear to interact with Sp1B in an analogous manner, suggesting a functional conservation between the two TAF proteins. It remains to be seen whether the interacting surfaces have similar structural characteristics.

Effects of transiently expressing hTAFII130 in cultured cells.

We have found that transient expression of the central domain of hTAFII130 containing Q1 to Q4 (hTAFII130N/C) as well as of subdomains of hTAFII130 containing Q1 alone (derivative 13) or Q1 and Q2 (derivative 10) decreased transcriptional activation of the reporter gene by Gal4-Sp1B, consistent with the finding that Sp1B interacted strongly with Q1 in the yeast two-hybrid study. In the same transient-transfection assay, we also found that wild-type hTAFII130 (amino acids 1 to 947) inhibited transcription by Gal4-Sp1B (Fig. 6B). It was previously reported that transient expression of full-length dTAFII110 did not affect transcriptional activation by Sp1 in insect cells (13). It is possible that overexpression of dTAFII110 was not sufficient to block activation by the full-length Sp1 used in that experiment, since full-length Sp1 has multiple potential targets within TFIID, including hTAFII55, as discussed above. By contrast, in another study, transient expression of the full-length as well as the C-terminal portions of hTAFII130 was reported to significantly enhance transcription of the reporter genes driven by the AF-2 activation domains of the retinoic acid, vitamin D3, and thyroid hormone receptors (26). The authors of that study found hTAFII130 to be limiting in vivo in some cell lines and thus speculated that overexpression might result in an increase in TFIID available for recruitment to promoters driven by AF-2. Interestingly, unlike the glutamine-rich activation domains described in this paper, AF-2 domains of selected nuclear receptors did not directly contact hTAFII130. The authors proposed that hTAFII130 might contact a common intermediary protein(s) that binds AF-2 domains in a subset of nuclear receptors. Finally, the conserved C-terminal 105 amino acids of hTAFII130 have been reported to interact with the CR3 activation domain of E1A. In that study, the C-terminal fragment of hTAFII130 was shown to specifically inhibit E1A-mediated transcriptional activation when transiently expressed in mammalian cells (25).

Although TAFs are present as integral components of the general transcription machinery, individual TAFs might be required by only a subset of activators in a eukaryotic cell. It is possible that short stretches of amino acid residues may be sufficient to provide specific points of contact between a given activator and a TAF. Thus, it is reasonable to envision 8 to 12 TAFs in the TFIID complex providing enough surface for interaction with a large number of activators present in a eukaryotic cell. Posttranslational modifications, differential splicing, and tissue-specific expression of TAFs may further add to the specificity of activator-TAF interactions. Indeed, the recent discovery of a new complex composed of TRF (TBP-related factor) and novel TAF subunits further increases the repertoire of TAFs required for coactivator function in different cell types (19). Binding of different activators to different TAFs or to distinct subdomains within the same TAF may allow TFIID to respond to multiple signals from activators bound upstream of the transcriptional initiation site, resulting in the coordinated expression of genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Grace Gill of Harvard Medical School for her help and generous gifts of the yeast and mammalian plasmids carrying Sp1 derivatives and to Michael Garabedian of New York University Medical Center for many valuable discussions. We thank Kelly Vogel and Amy Kun for technical assistance, Eileen Rojo-Niersbach and Stavros Giannakopoulos for their help with the project, Muktar Mahajan for advice on the yeast two-hybrid assay, Sobha Pisharody for assistance with cell culture, and David Ron for the gift of the reporter plasmid. Critical reading of the manuscript by Michael Garabedian and Grace Gill was greatly appreciated.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01-BM51314). D.S. was supported by a National Institutes of Health Training Grant (5T32 AI07180), and N.T. was supported in part by The Irma T. Hirschl Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apone L M, Virbasius C A, Reese J C, Green M R. Yeast TAFII90 is required for cell-cycle progression through G2/M but not for general transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2368–2380. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke T W, Kadonaga J T. The downstream core promoter element, DPE, is conserved from Drosophila to humans and is recognized by TAFII60 of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3020–3031. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burley S K, Roeder R G. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID) Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:769–799. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey M. The enhanceosome and transcriptional synergy. Cell. 1998;92:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang M, Jaehning J A. A multiplicity of mediators: alternative forms of transcription complexes communicate with transcriptional regulators. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4861–4865. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J L, Attardi L D, Verrijzer C P, Yokomori K, Tjian R. Assembly of recombinant TFIID reveals differential coactivator requirements for distinct transcriptional activators. Cell. 1994;79:93–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chi T, Lieberman P, Ellwood K, Carey M. A general mechanism for transcriptional synergy by eukaryotic activators. Nature. 1995;377:254–257. doi: 10.1038/377254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang C-M, Roeder R G. Cloning of an intrinsic human TFIID subunit that interacts with multiple transcriptional activators. Science. 1995;267:531–536. doi: 10.1126/science.7824954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courey A J, Tjian R. Analysis of Sp1 in vivo reveals multiple transcription domains, including a novel glutamine-rich activation motif. Cell. 1988;55:887–898. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dikstein R, Ruppert S, Tjian R. TAFII250 is a bipartite protein kinase that phosphorylates the basal transcription factor RAP74. Cell. 1996;66:563–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dikstein R, Zhou S, Tjian R. Human TAFII105 is a cell type specific TFIID subunit related to hTAFII130. Cell. 1996;87:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durfee T, Becherer K, Chen P-L, Yeh S-H, Yang Y, Kilburn A E, Lee W-H, Elledge S J. The retinoblastoma protein associates with the protein phosphatase type 1 catalytic subunit. Genes Dev. 1993;7:555–569. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farmer G, Colgan J, Nakatani Y, Manley J, Prives C. Functional interaction between p53, the TATA-binding protein (TBP), and TBP-associated factors in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4295–4304. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreri K, Gill G, Montminy M. The cAMP-regulated transcription factor CREB interacts with a component of the TFIID complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1210–1213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garabedian M J. Genetic approaches to mammalian nuclear receptor function in yeast. Methods Companion Methods Enzymol. 1993;5:138–146. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill G, Pascal E, Tseng Z H, Tjian R. A glutamine-rich hydrophobic patch in transcription factor Sp1 contacts the dTAFII110 component of the Drosophila TFIID complex and mediates transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:192–196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodrich J A, Hoey T, Thut C J, Admon A, Tjian R. Drosophila TAFII40 interacts with both a VP16 activation domain and the basal transcription factor TFIIB. Cell. 1993;75:519–530. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gyuris J, Golemis E A, Chertkov H, Brent R. Cdi 1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell. 1993;75:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90498-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen S K, Takada S, Jacobson R H, Lis J T, Tjian R. Transcription properties of a cell type-specific TATA-binding protein, TRF. Cell. 1997;91:71–83. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoey T, Weinzierl R O, Gill G, Chen J L, Dynlacht B D, Tjian R. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of Drosophila TAF110 reveal properties expected of coactivators. Cell. 1993;72:247–260. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90664-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacq X, Brou C, Lutz Y, Davidson I, Chambon P, Tora L. Human TAFII30 is present in a distinct TFIID complex and is required for transcriptional activation by the estrogen receptor. Cell. 1994;79:107–117. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim T K, Maniatis T. The mechanism of transcriptional synergy of an in vitro assembled interferon-β enhanceosome. Mol Cell. 1998;1:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klemm R D, Goodrich J A, Zhou S, Tjian R. Molecular cloning and expression of the 32-kDa subunit of human TFIID reveals interactions with VP16 and TFIIB that mediate transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5788–5792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu H, Levine A. Human TAF31 protein is a transcriptional coactivator of the p53 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5154–5158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazzarelli J M, Mengus G, Davidson I, Ricciardi R P. The transactivation domain of adenovirus E1A interacts with the C terminus of human TAFII135. J Virol. 1997;71:7978–7983. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7978-7983.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mengus G, May M, Carre L, Chambon P, Davidson I. Human TAFII135 potentiates transcriptional activation by the AF-2s of the retinoic acid, vitamin D3, and thyroid hormone receptors in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1381–1395. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merika M, Williams A J, Chen G, Collins T, Thanos D. Recruitment of CBP/p300 by the IFNβ enhanceosome is required for synergistic activation of transcription. Mol Cell. 1998;1:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizzen C A, Yang X-J, Kokubo T, Brownell J E, Bannister A J, Owen-Hughes T, Workman J, Wang L, Berger S L, Kouzarides T, Nakatani Y, Allis C D. The TAFII250 subunit of TFIID has histone acetyltransferase activity. Cell. 1996;87:1261–1270. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81821-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moqtaderi Z, Bai Y, Poon D, Weil P A, Struhl K. TBP-associated factors are not generally required for transcriptional activation in yeast. Nature. 1996;383:188–191. doi: 10.1038/383188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakajima T, Uchida C, Anderson S F, Parvin J D, Montminy M. Analysis of a cAMP-responsive activator reveals a two-component mechanism for transcriptional induction via signal-dependent factors. Genes Dev. 1997;11:738–747. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oelgeschlager T, Chiang C-M, Roeder R G. Topology and reorganization of a human TFIID-promoter complex. Nature. 1996;382:735–738. doi: 10.1038/382735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pascal E, Tjian R. Different activation domains of Sp1 govern formation of multimers and mediate transcriptional synergism. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1646–1656. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ptashne M, Gann A. Transcriptional activation by recruitment. Nature. 1997;386:569–577. doi: 10.1038/386569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ron D, Habener J F. CHOP, a novel developmentally regulated nuclear protein that dimerizes with transcription factors C/EBP and LAP and functions as a dominant-negative inhibitor of gene transcription. Genes Dev. 1992;6:439–453. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadowski I, Ma J, Triezenberg S, Ptashne M. GAL4-VP16 is an unusually potent transcriptional activator. Nature. 1988;335:563–564. doi: 10.1038/335563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sauer F, Hansen S K, Tjian R. DNA templates and activator-coactivator requirements for transcriptional synergism by Drosophila Bicoid. Science. 1995;270:1825–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sauer F, Hansen S K, Tjian R. Multiple TAFIIs directing synergistic activation of transcription. Science. 1995;270:1783–1788. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sauer F, Tjian R. Mechanisms of transcriptional activation: differences and similarities between yeast, Drosophila, and man. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:176–181. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sauer F, Wassarman D A, Rubin G M, Tjian R. TAFIIs mediate activation of transcription in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1996;87:1271–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81822-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shao Z, Ruppert S, Robbins P D. The retinoblastoma-susceptibility gene product binds directly to the human TATA-binding protein-associated factor TAFII250. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3115–3119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen W-C, Green M R. Yeast TAFII145 functions as a core promoter selectivity factor, not a general coactivator. Cell. 1997;90:615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80523-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun P, Enslen H, Myung P S, Maurer R A. Differential activation of CREB by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases type II and type IV involves phosphorylation of a site that negatively regulates activity. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2527–2539. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanese N, Saluja D, Vassallo M F, Chen J-L, Admon A. Molecular cloning and analysis of two subunits of the human TFIID complex: hTAFII130 and hTAFII100. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13611–13616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thut C J, Chen J L, Klemm R, Tjian R. p53 transcriptional activation mediated by coactivators TAFII40 and TAFII60. Science. 1995;267:100–104. doi: 10.1126/science.7809597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walker S S, Reese J C, Apone L M, Green M R. Transcriptional activation in cells lacking TAFIIs. Nature. 1996;383:185–188. doi: 10.1038/383185a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker S S, Shen W-C, Reese J C, Apone L M, Green M R. Yeast TAFII145 required for transcription of G1/S cyclin genes and regulated by the cellular growth state. Cell. 1997;90:607–614. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yokomori K, Chen J L, Admon A, Zhou S, Tjian R. Molecular cloning and characterization of dTAFII30 α and dTAFII30 β: two small subunits of Drosophila TFIID. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2587–2597. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]