ABSTRACT

Amikacin is an FDA-approved aminoglycoside antibiotic that is commonly used. However, validated dosage regimens that achieve clinically relevant exposure profiles in mice are lacking. We aimed to design and validate humanized dosage regimens for amikacin in immune-competent murine bloodstream and lung infection models of Acinetobacter baumannii. Plasma and lung epithelial lining fluid (ELF) concentrations after single subcutaneous doses of 1.37, 13.7, and 137 mg/kg of body weight were simultaneously modeled via population pharmacokinetics. Then, humanized amikacin dosage regimens in mice were designed and prospectively validated to match the peak, area, trough, and range of plasma concentration profiles in critically ill patients (clinical dose: 25–30 mg/kg of body weight). The pharmacokinetics of amikacin were linear, with a clearance of 9.93 mL/h in both infection models after a single dose. However, the volume of distribution differed between models, resulting in an elimination half-life of 48 min for the bloodstream and 36 min for the lung model. The drug exposure in ELF was 72.7% compared to that in plasma. After multiple q6h dosing, clearance decreased by ~80% from the first (7.35 mL/h) to the last two dosing intervals (~1.50 mL/h) in the bloodstream model. Likewise, clearance decreased by 41% from 7.44 to 4.39 mL/h in the lung model. The humanized dosage regimens were 117 mg/kg of body weight/day in mice [administered in four fractions 6 h apart (q6h): 61.9%, 18.6%, 11.3%, and 8.21% of total dose] for the bloodstream and 96.7 mg/kg of body weight/day (given q6h as 65.1%, 16.9%, 10.5%, and 7.41%) for the lung model. These validated humanized dosage regimens and population pharmacokinetic models support translational studies with clinically relevant amikacin exposure profiles.

KEYWORDS: amikacin, lung epithelial lining fluid, bloodstream infection, lung infection, population pharmacokinetics, model-based humanized dosage regimen design, S-ADAPT, aminoglycoside, mouse/mice, murine infection model

INTRODUCTION

Amikacin is an FDA-approved aminoglycoside antibiotic that is commonly used for the treatment of infections by Gram-negative bacteria. Once-daily dosing of 15–30 mg/kg of body weight has been recommended to maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity in critically ill patients (1). The high amikacin peak concentrations following once-daily dosing can achieve rapid and extensive bacterial killing against susceptible isolates. Likewise, once daily dosing provides better safety since it saturates and, therefore, minimizes the uptake of aminoglycosides into renal tubular cells more than twice or three times daily dosing. Thus, once-daily dosing is recommended by clinical guidelines (2, 3).

For 15 mg amikacin/kg of body weight once daily, the terminal half-life in adult healthy volunteers is 2.4 ± 0.5 h, the peak concentration is 76.6 ± 14.4 mg/L, and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) 154 ± 29 mg·h/L (4). The terminal half-life is ~5 h in elderly patients (4, 5) and 6.8 h in critically ill patients with normal renal function (6). In humans, amikacin plasma concentrations decline bi-exponentially with a rapid α- and a slower β-phase arising from a two-compartment model. In patients, the β-phase contributes ~90% of the total AUC (6, 7), whereas the α-phase contributes ≥95% of the total AUC in infected mice. The α-phase has a half-life of ~24–32 min in mouse plasma and lung epithelial lining fluid (ELF; Fig. S1) (8, 9). At higher doses, mice display a β-phase with a 3.1–4.4 h half-life, but this phase only accounts for ≤5% of the total AUC (Fig. S1). Thus, the half-life associated with the predominant portion of the AUC in plasma is ~15 times shorter in infected mice (~28 min) than in critically ill patients (6.8 h).

For aminoglycosides, the AUC/MIC and peak concentration by MIC (Cmax/MIC) ratios best predict clinical outcomes in patients (10, 11). High Cmax and low trough concentrations for once-daily dosing are clinically beneficial (2, 3). To mirror the time course of clinical drug concentration profiles in mice, it is important to account for the substantially shorter half-life in mice. Such humanization has been originally proposed for imipenem in mice via frequent dosing over 6 or 12 h (12). Subsequently, AUC-matched dosage regimens were proposed for levofloxacin (13). Recently, humanized dosage regimens that match the plasma concentration-time profiles, including the peak and trough concentrations, as well as the AUC, between mice and humans, have been proposed for polymyxin B (14). A pharmacokinetic (PK) modeling-based approach was used to account for the short half-life in infected mice [~4 vs ~12 h in patients (15)] and for bi-exponential PK of polymyxin B in humans and mono-exponential PK in mice (14).

Matching the peak concentrations between mice and humans is important since bacterial killing by aminoglycosides is concentration dependent (16, 17). Thus, overly high peak concentrations in mice may result in rapid killing. Likewise, amikacin trough concentrations in critically ill patients at 24 h usually range from 1 to 20 mg/L, depending on renal function (6, 7). Due to the shorter half-life in mice (~24–32 min), amikacin concentrations decline below 1 mg/L within 2–4 h, depending on the dose (8, 9).

This study aimed to define and prospectively validate the first humanized amikacin dosage regimens for two infection models in immune-competent mice with bloodstream or lung infections due to Acinetobacter baumannii. Second, we sought to develop a new algorithm to match the peak, area, trough, and range of plasma concentrations (“PATR-matching”) between mice and man. Optimal design and population PK analyses based on single-dose PK data were used to design humanized dosage regimens, which were prospectively validated by multiple-dose PK studies. These regimens provided clinically relevant amikacin concentration-time profiles in mice to support translation to patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Amikacin (pharmaceutical grade) for animal PK studies was purchased from Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. (North Wales, PA, USA). For bioanalysis, amikacin reference standards were obtained from Sagent (Schaumburg, IL, USA), and the internal standard tobramycin from US Pharmacopeia (Rockville, MD, USA). Urea (purity > 99%) and its stable isotope-labeled internal standard urea-15N2 (purity > 98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Acetonitrile, methanol, formic acid, phosphoric acid, and other reagents used in the bioanalysis were LC/MS grade and purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

The A. baumannii clinical isolate HUMC1 was isolated from Los Angeles County, CA, USA (18, 19), which demonstrated an amikacin MIC of 128 mg/L and was further resistant to carbapenems (14). The strain was cultured in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth, and log-phase culture was diluted for use in animal infection models. Specific pathogen-free, healthy male (8 weeks) or female (10 weeks), immune-competent C3HeB/FeJ mice (Jackson Laboratory, stock no. 000658) were used. Age differed slightly to match the weight between both sexes. Food and water were provided ad libitum.

PK dose range studies with single doses

Two murine infection models were used for all PK studies. The bloodstream infection model was developed by challenging via the intravenous route (2 × 107 CFU), while the lung infection model by challenging via the oral aspiration route (4.7 × 108 CFU) both with HUMC1. To identify informative sampling times for blood and ELF, a population PK model was developed based on an in-house data set for amikacin with single and multiple intravenous dosing in infected mice (results not shown). Additionally, information on ELF penetration was borrowed from a population PK analysis of plasma and ELF concentrations for tobramycin in infected mice (20). Subsequently, optimal design analyses were performed in the PopED lite software (21) to identify informative sampling times across the different studied dose levels.

Optimal and robust sampling times were identified to be 0.17, 1, 2.5, 3.5, 4.5, and 5.5 h. Six mice (three female and three male) were studied at each of these six sampling times. The single-dose PK studies employed a fully factorial design with doses of 1.37, 13.7, or 137 mg/kg of body weight in the intravenous and lung infection models. With six mice each at six time points, this yielded 216 mice in total (Fig. S2). Amikacin solutions (300 µL, adjusted based on weight) were subcutaneously dosed starting at 2 h post-infection.

At these scheduled times, animals were anesthetized and at least 500 µL of blood was collected for each animal in the two infection models using destructive sampling (i.e., one sampling time per mouse). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was collected specifically for the lung infection model using 1 mL of PBS for lavage via the trachea. All PK samples were immediately placed on ice, centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C, and aliquoted. Samples were stored below −70°C and shipped on dry ice to the University of Florida for bioanalysis.

Bioanalysis

Plasma and BAL samples were analyzed by validated ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) methods. After thawing and vortex mixing, samples (10 µL for plasma and 20 µL for BAL) were spiked with 5 µL of internal standard solution (tobramycin, 10 mg/L for plasma and 25 mg/L for BAL) and 5% trichloroacetic acid (10 µL for plasma and 20 µL for BAL) and vortexed for 45 s. Samples were centrifuged at 16,100 g for 10 min. Supernatants (30 µL) were transferred to 96-well plates, diluted with 100 µL of H2O, vortexed, and subjected to analysis (injection volume: 1 µL for plasma and 10 µL for BAL).

Amikacin and the internal standard tobramycin were resolved using an Acquity I-Class UPLC system with a Phenomenex Kinetex C18 column (50 × 3 mm, internal diameter: 2.6 µm). The mobile phase contained 0.02% heptafluorobutyric acid in water and acetonitrile in a gradient method. The flow rate was 0.400 mL/min and the column temperature was 40°C. An API-5000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer from Sciex (Foster City, CA, USA) equipped with a TurboIonSpray source was operated in positive-ion mode. The multiple reaction monitoring method was used for quantification and analysis in the Analyst software (v1.6.2). The monitored mass/charge (m/z) transitions were m/z 586 → 163 for amikacin 1, m/z 586 → 425 for amikacin 2, m/z 586 → 264 for amikacin 3, m/z 586 → 247 for amikacin 4, and m/z 468 → 163 for tobramycin. To calculate concentrations for amikacin in ELF, the urea method was used, which employed plasma and BAL concentrations of amikacin and urea (14, 22, 23).

Population PK modeling

Population PK models were initially developed separately for the bloodstream and the lung infection model data after a single dose. Subsequently, all amikacin plasma and ELF concentrations after a single dose from both infection models were simultaneously modeled (Fig. S2). The model included one central compartment plus a lung ELF compartment with linear elimination from the central compartment. Absorption after subcutaneous dosing was described by a first-order process. The ELF volume was fixed to a small value (0.1 mL) that did not noticeably affect the overall time course of plasma concentrations, as shown by a sensitivity analysis (Fig. S3). This allowed us to estimate the equilibration half-life (t1/2,eq) between the ELF and the central compartment, while the plasma concentrations displayed a mono-exponential decline (24–26). Additionally, the ratio (FELF) of the amikacin AUC in ELF and plasma was estimated to characterize the average extent of ELF penetration. When we modeled all plasma and ELF concentrations after a single dose simultaneously, clearance (CL), the volume of distribution of the central compartment (V1), or both were estimated with the same or different values between both infection models.

Competing models were evaluated based on estimation- and simulation-based diagnostic plots and by assessing the plausibility of parameter estimates (27, 28). All estimations were performed with the importance sampling algorithm (pmethod = 4) in the S-ADAPT software (version 1.57) along with the SADAPT-TRAN facilitator package (29–31). A combined additive plus proportional residual error model was used to describe the plasma and ELF concentrations. Monte Carlo simulations were performed in the Berkeley Madonna software (version 8.3.18, University of California).

Model-based humanized dosage regimens

Clinical PK studies for amikacin were reviewed to provide the targeted range of plasma concentrations in critically ill patients to be mirrored by giving humanized dosage regimens in mice. At a clinical daily dose of 25–30 mg/kg of body weight, Cmax in patients ranged from ~30 to 100 mg/L and the trough concentrations from ~1 to 20 mg/L (1, 6, 7, 32). Based on 60 plasma concentration-time profiles (6), we obtained the range (i.e., the ~10th–90th percentiles) for the concentrations in patients by digitizing published data via the WebPlotDigitizer software (version 4.1, by Ankit Rohatgi, Pacifica, CA, USA).

The typical amikacin plasma concentration profiles in infected mice were simulated for the bloodstream and lung infection models based on the developed population PK models in mice (Berkeley Madonna simulation code provided in the supplemental material). We considered humanized dosage regimens in mice with up to five amikacin doses per day for feasibility reasons and aimed to match the plasma AUC between mice and critically ill patients. Additionally, at each of these individual doses, the peak of the mouse plasma concentration was targeted to reach and not exceed the 90th percentile of the interpolated plasma concentrations in patients. Amikacin protein binding in human plasma was reported as 17.5% ± 8.6% and 18.0% ± 3.64% (33, 34), which is comparable to the recently published protein binding of amikacin in mouse plasma of 24% (8). Thus, protein binding was not considered for humanizing dosage regimens.

Validation of humanized dosage regimens with multiple dosing

Multiple-dose PK validation studies were performed to prospectively validate the humanized dosage regimens. Peak concentrations at 1, 7, 13, and 19 h as well as trough concentrations at 5.5, 11.5, 17.5, and 24 h were determined and compared to the targeted plasma and ELF concentrations predicted based on the single-dose data. These times were selected since they are pharmacologically important to reflect antibacterial efficacy and safety. A fully factorial design was employed for these prospective validation studies with eight (i.e., four female and four male) mice studied at each of these eight time points in the bloodstream and the lung infection models, yielding 128 mice in total (Fig. S2).

We then developed population PK models for the multiple-dose data sets of the bloodstream and the lung infection models (Fig. S2). The bloodstream and to some degree also the lung infection model displayed increasingly more variable and higher plasma concentrations after the doses at 12 and 18 h. Therefore, models with different CL (e.g., CL0-6h, CL6-12h, CL12-18h, and CL18-24h), different V1 (e.g., V10-6h, V16-12h, V112-18h, and V118-24h), or both different CL and V1 were considered for each 6 h dosing interval. The AUC0-24h, AUC0-6h, AUC6-12h, AUC12-18h, and AUC18-24h in the multiple-dose studies were calculated via numerical integration of the plasma and ELF concentration profiles based on the individual fitted mouse concentration-time profiles (and PK parameters).

RESULTS

The overall flow of experimental and modeling studies started with identifying optimal sampling times at relevant amikacin doses based on in-house data sets (Fig. S2). Then, single-dose PK data on amikacin were generated and first modeled separately for each infection model, followed by simultaneous modeling of all single-dose PK data from both infection models. Based on these single-dose results, this combined population PK model was used to generate humanized dosage regimens, which were prospectively validated via multiple-dose PK studies (Fig. S2). Finally, the latter were modeled separately for the bloodstream and lung infection models, as detailed below.

Infected animals showed multiple signs of infections as reported in our natural history study (19). For bioanalysis, the linear range for amikacin concentrations was 0.25–250 mg/L or 0.01–100 mg/L in plasma (different assay variants) and 0.001–5.00 mg/L in BAL samples (equivalent to approximately 0.02–100 mg/L for ELF). Retention times of the amikacin in plasma and BAL were 2.17 and 2.44 min. Accuracy and precision for both methods were within ±20%.

Population PK modeling of dose range studies after a single dose

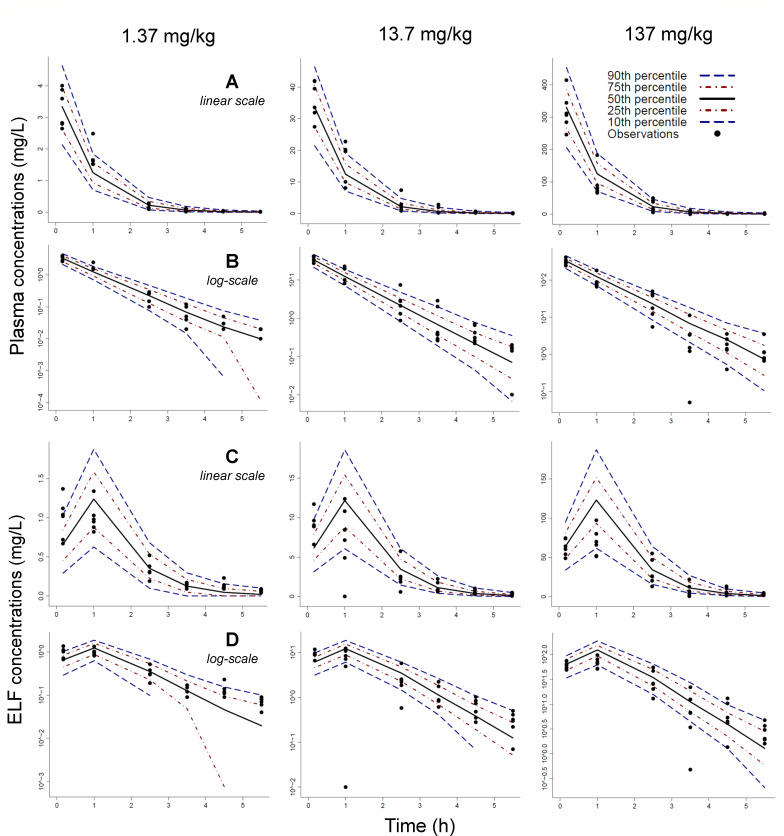

The PK of amikacin in plasma and ELF was linear and displayed a mono-exponential decline for single doses of 1.37, 13.7, and 137 mg/kg of body weight. These plasma profiles were well explained by a linear one-compartment PK model (Fig. 1). For the lung infection model, we included an ELF compartment with a small, non-influential volume (Fig. S3). The ELF to plasma concentration ratios showed system hysteresis with ratios below 1.0 during the first hour and ratios above 1.0 thereafter (Fig. S4); this was captured by the ELF to plasma equilibration half-life (t1/2,eq: 21.9 min; Table 1). The estimated ratio of AUCs in ELF and plasma (FELF) was 0.727 (Table 1), indicating considerable ELF penetration in infected mice. This model yielded unbiased and reasonably precise fits (Fig. S5 and S6). While the fitted peak concentrations in ELF (at 1 h) were slightly too high (Fig. 3), models with a saturable distribution clearance from the central into the ELF compartment did not improve these curve fits.

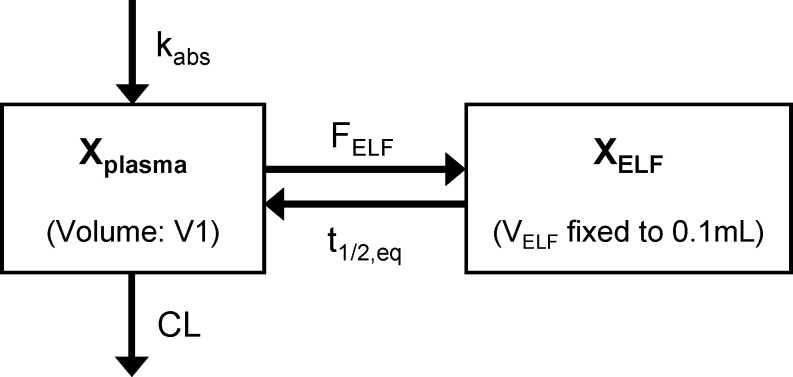

Fig 1.

Population PK model structure for amikacin describing the plasma and lung ELF concentrations in immune-competent murine models with bloodstream or lung infection. The kabs is the first-order absorption rate constant from the subcutaneous injection site, V1 is the volume of distribution of the central compartment, and CL is the total body clearance. The Xplasma represents the amount of amikacin in the central compartment, XELF is the amount in the ELF compartment, and FELF is the AUC in ELF divided by the AUC in plasma. The volume of distribution of the ELF compartment (VELF) was fixed to a small value, which only minimally affected the plasma concentrations. The t1/2,eq is the equilibration half-life between the ELF and the plasma compartment.

TABLE 1.

| Symbol | Parameter | Unit | Population mean, CVa (RSE)b |

Between subject variability, CVa (RSE)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t1/2,abs (B) | Absorption half-life for the bloodstream infection model | min | 1.75 (12.1%) | 0.1 (fixed) |

| t1/2,abs (L) | Absorption half-life for the lung infection model | min | 1.01 (34.9%) | 0.1 (fixed) |

| CL | Clearance | mL/h | 9.93 (7.85%) | 0.185 (54.8%) |

| V1 (B) | Volume of distribution for the central compartment in the bloodstream infection model | mL | 11.4 (14.1%) | 0.1 (fixed) |

| V1 (L) | V1 in the lung infection model | mL | 8.56 (9.8%) | 0.1 (fixed) |

| F ELF | Ratio of AUCs in ELF and plasma | 0.727 (16.9%) | 0.1 (fixed) | |

| t 1/2,eq | Equilibration half-life between the ELF and the central compartment | min | 21.9 (8.1%) | 0.1 (fixed) |

| V ELF | Volume of distribution for the ELF compartment | mL | 0.1 (fixed) |

Coefficient of variation, CV%.

Relative standard errors, RSE.

The additive residual error standard deviations for plasma concentrations were fixed to 0.01 mg/L (equivalent to 1× the lower limit of quantification in plasma) for the bloodstream and the lung infection. The additive residual error standard deviation for ELF concentrations was estimated to be 0.0502 mg/L (RSE: 26.8%).

The proportional residual errors for plasma concentrations were estimated to be 0.331 (22.2%) for the bloodstream infection model, and 0.274 (24.0%) for the lung infection model. The proportional residual error for ELF concentrations was estimated to be 0.350 (11.2%).

All amikacin plasma and ELF concentrations from the bloodstream and lung infection models were fit simultaneously. The same clearance but different volumes of distribution (V1) were used for the bloodstream and lung infection models for the single-dose data sets. This model and parameter estimates were used to design humanized dosing regimens.

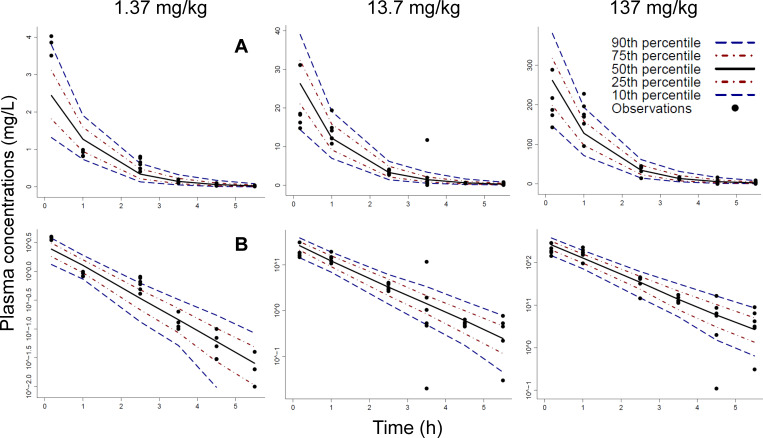

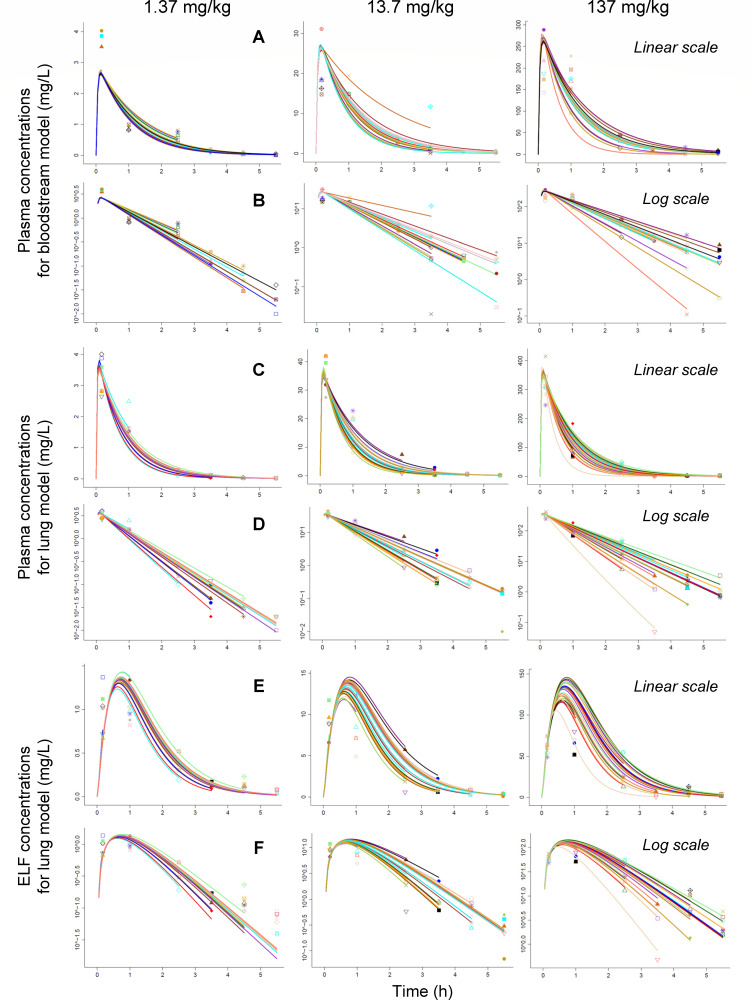

The model captured the central tendency and variability of the observations after a single dose reasonably well (Fig. 2 and 3). For the bloodstream model, peak concentrations were under-predicted at the low dose, and better predicted at higher doses. Absorption from the subcutaneous injection site was rapid, with half-lives of 1.75 min for the bloodstream and 1.01 min for the lung infection model (Table 1). Both infection models shared the same clearance estimate (9.93 mL/h) for the single-dose data sets. However, the volume of distribution was 25% larger (11.4 mL) for the bloodstream compared to that of the lung infection model (8.56 mL). Consequently, the bloodstream model had a longer typical elimination half-life (48 vs 36 min for the lung model) and lower peak concentrations (Fig. 4; simulation code provided in the supplemental material).

Fig 2.

Visual predictive check for the population PK analysis of the bloodstream infection model for the PK dose ranging studies using single doses of 1.37, 13.7, and 137 mg/kg of body weight. Plasma concentrations were plotted on linear scale (row A) and log scale (row B). The observations (markers) were plotted along with the 50th percentile (i.e., the median; black line), the 80% prediction interval (10th–90th percentile), and the interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of the model predictions. Ideally, the median should reflect the central tendency of the observations, and 10% of observations should fall outside the 80% prediction interval on either side.

Fig 3.

Visual predictive check for the population PK analysis of the lung infection model for the PK dose ranging studies using single doses of 1.37, 13.7, and 137 mg/kg of body weight. Plasma concentrations were plotted on linear scale (row A) and log scale (row B). Likewise, ELF concentrations were plotted on linear scale (row C) and log scale (row D). The observations (markers) were plotted along with the 50th percentile (i.e., the median; black line), the 80% prediction interval (10th–90th percentile), and the interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of the model predictions.

Fig 4.

Individual fits for the single-dose PK dose range studies (1.37, 13.7, and 137 mg/kg of body weight). Plasma concentrations from the bloodstream and lung infection models are shown in rows A and C on linear scale, as well as in rows B and D on log scale, respectively. The ELF concentrations from the lung infection model are plotted in row E on linear scale and in row F on log scale. Markers are observations and curves are individual fits.

The population mean parameter estimates were reasonably precise with relative standard errors (RSE) below 20% (except for an RSE of 34.9% for the rapid absorption half-life of the lung model; Table 1). The between subject variability (BSV) was relatively small with a CV of 18.5% for clearance. For the other PK parameters, BSV was estimated to be small and eventually fixed to a small and non-influential CV of 10%. Additional analyses that fitted the bloodstream and the lung infection models separately yielded consistent parameter estimates (results not shown), suggesting that simultaneous modeling of both data sets after single dosing was reasonable (Fig. S2).

Model-based humanized dosage regimen design

At a dose of 30 mg/kg of body weight, adult healthy volunteers had an AUC0-24h of ~308 mg·h/L in plasma (4). This estimate fell into the range of AUC0-24h observed in patients with ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (VABP) of ~179–851 mg·h/L (10th–90th percentile). Thus, we targeted an AUC0-24h of 308 mg·h/L for the humanized dosage regimens in mice. We then calculated the daily dose in mice as the product of the targeted human AUC0-24h and the clearance in mice (9.93 mL/h; Table 1), which yielded a daily dose of 3,058 µg (equivalent to 122 mg/kg of body weight in a 25 g mouse). Owing to the shorter half-life in mice compared to that in patients, the daily dose was split into four smaller doses given at 0, 6, 12, and 18 h. The individual doses at each time point were adjusted so that the predicted peak concentration in mice would reach, but not exceed, the 90th percentile of the plasma concentrations in patients (Fig. 5). The latter criterion resulted in slightly smaller daily doses that were predicted to achieve an AUC0-24h of 296 mg·h/L for the bloodstream and an AUC0-24h of 244 mg·h/L for the lung infection model (with an AUC0-24h in ELF of 177 mg·h/L; Fig. S3). This difference was caused by the smaller volume of distribution and shorter half-life for the lung compared to those of the bloodstream infection model. However, both these AUC0-24h values fell well within the range of AUC0-24h in patients at a daily dose of 30 mg/kg of body weight.

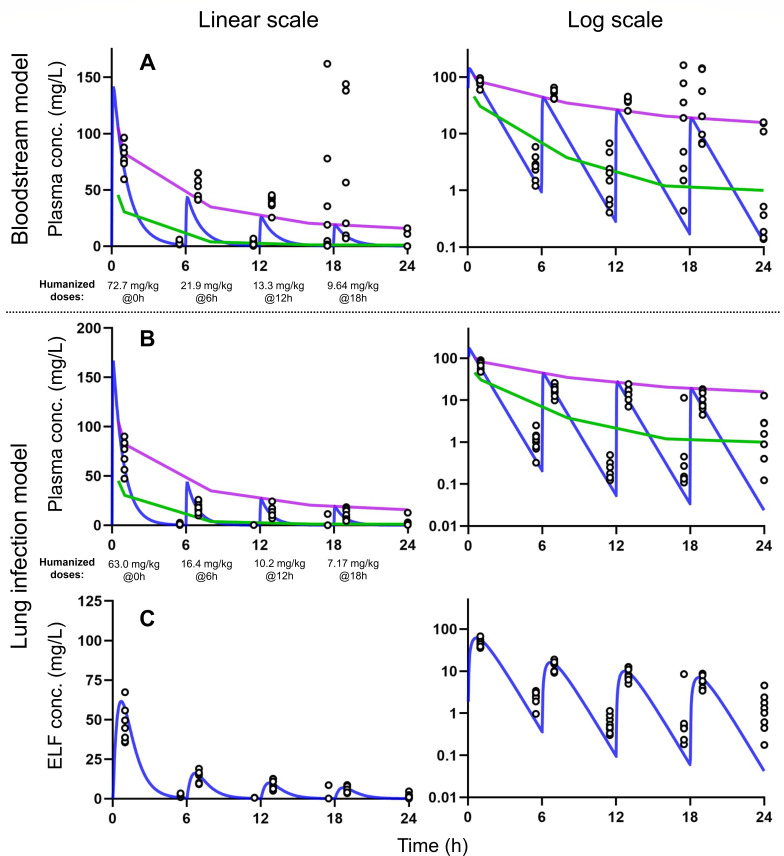

Fig 5.

Prospective validation of humanized dosage regimens for amikacin after multiple dosing in murine models with bloodstream infection (row A) and lung infection (rows B and C) at linear scale (left column) and log scale (right column). The green line is the 10th percentile, and the purple line is the 90th percentile of the amikacin plasma concentrations in critically ill patients. The blue line is the typical simulated PK profile for amikacin in mice based on the established model after a single dose (Table 1). The dots are observed concentrations. The humanized dosage regimens used q6h dosing for the bloodstream infection model (61.9% at 0 h, 18.6% at 6 h, 11.3% at 12 h, and 8.21% at 18 h, 117 mg/kg of body weight/day in total) and the lung infection model (65.1% at 0 h, 16.9% at 6 h, 10.5% at 12 h, and 7.41% at 18 h, 96.72 mg/kg of body weight/day in total).

The resulting humanized dosage regimen contained a daily dose of 117 mg/kg of body weight/day with individual doses of 72.7 mg/kg of body weight at 0 h, 21.9 mg/kg of body weight at 6 h, 13.3 mg/kg of body weight at 12 h, and 9.64 mg/kg of body weight at 18 h for the bloodstream infection model. For the lung model, the daily dose was 96.7 mg/kg of body weight/day, with individual doses of 63.0, 16.4, 10.2, and 7.17 mg/kg of body weight. These humanized dosage regimens were subsequently tested in two PK validation studies. For these dosage regimens, the simulated mouse plasma concentration reached the 90th percentile but declined below the 10th percentile due to the short half-life in mice (Fig. 5).

Prospective validation of humanized dosage regimens via multiple-dose PK studies

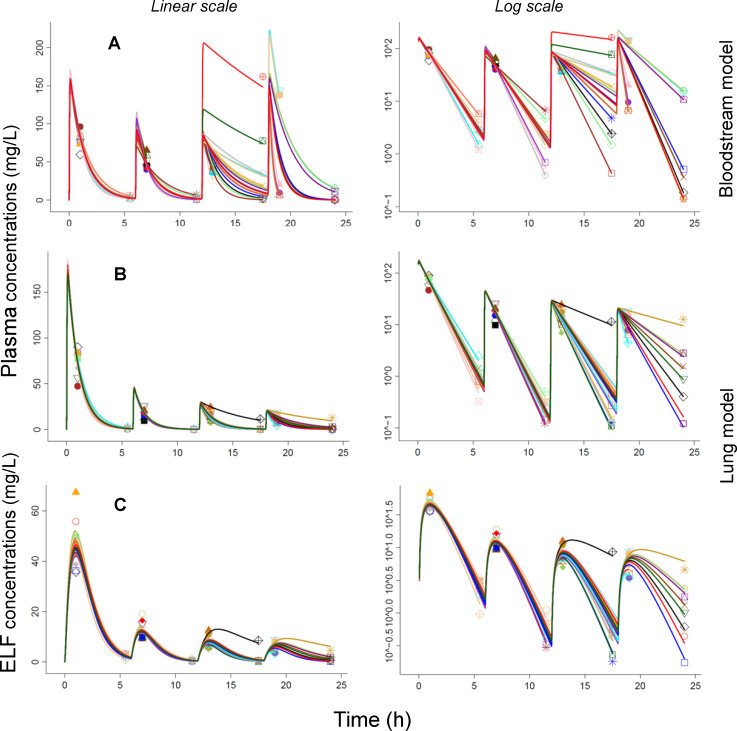

These predictions based on the single-dose PK model in mice were prospectively validated by multiple-dose PK studies (Fig. S2). For the bloodstream infection model, the observed plasma concentrations matched the predicted profiles reasonably well during the first 6 h. However, during the later dosing intervals, the observed peak and trough concentrations were increasingly higher compared to the predicted concentrations, despite the lower doses at 6, 12, and 18 h. The observed variability was extensive, especially for the last two dosing intervals (Fig. 5; Fig. S7). This suggested a change in the systemic disposition parameter(s) over time likely due to the increasing severity of infection. When estimating the PK data for the bloodstream infection model, clearance decreased by ~80% over time (i.e., from 7.35 mL/h for the first dosing interval to ~1.5 mL/h for the last two dosing intervals). Likewise, the estimated volume of distribution decreased between the dosing intervals (Table 2). The typical half-life was ~56 min during the first two dosing intervals, and the half-life was more variable thereafter (Fig. 6).

TABLE 2.

Population PK parameter estimates for the multiple-dose PK validation study (with humanized dosage regimens at 0, 6, 12, and 18 h)a

| Symbol | Parameter | Unit | Population mean (RSE) | Between subject variability (RSE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloodstream infection model | ||||

| t1/2,abs | Absorption half-life | min | 1.00 (21.2%) | 0.115 (146%) |

| CL0-6h | Clearance for the first dosing interval | mL/h | 7.35 (6.8%) | 0.10 (fixed) |

| CL6-12h | CL for the second dosing interval | mL/h | 3.81 (6.5%) | 0.155 (68.5%) |

| CL12-18h | CL for the third dosing interval | mL/h | 1.39 (25.1%) | 1.07 (29.9%) |

| CL18-24h | CL for the fourth dosing interval | mL/h | 1.60 (23.5%) | 0.779 (47.4%) |

| V10-6h | Volume of distribution for the first dosing interval |

mL | 9.75 (14.7%) | 0.10 (fixed) |

| V16-12h | V1 for the second dosing interval | mL | 5.24 (10.4%) | 0.250 (72.4%) |

| V112-18h | V1 for the third dosing interval | mL | 3.50 (28.3%) | 0.430 (80.9%) |

| V118-24h | V1 for the fourth dosing interval | mL | 1.51 (18.6%) | 0.195 (147%) |

| Lung infection model | ||||

| t1/2, abs | Absorption half-life | min | 1.12 (24.7%) | 0.10 (fixed) |

| CL0-6h | Clearance for the first dosing interval | mL/h | 7.44 (5.5%) | 0.10 (fixed) |

| CL6-12h | CL for the second dosing interval | mL/h | 7.69 (4.9%) | 0.10 (fixed) |

| CL12-18h | CL for the third dosing interval | mL/h | 5.92 (13.1%) | 0.500 (42.3%) |

| CL18-24h | CL for the fourth dosing interval | mL/h | 4.39 (17.6%) | 0.656 (39.7%) |

| V1 | Volume of distribution | mL | 7.69 (6.4%) | 0.10 (fixed) |

| FELF | Ratio of AUCs in ELF and plasma | 0.604 (4.9%) | 0.10 (fixed) | |

| t1/2, ELF | Equilibration half-life between the ELF and the central compartment | min | 36.4 (4.4%) | 0.10 (fixed) |

| VELF | Volume of distribution for ELF compartment | mL | 0.10 (fixed) | |

For the bloodstream infection model, clearance and volume of distribution were modeled separately for each dosing interval. For the lung infection model, volume of distribution was constant, but clearance was estimated separately for each dosing interval. The changes in clearance and volume of distribution over time likely reflected the impact of disease progression on PK for each infection model.

Fig 6.

Individual fitting plots for the population PK analysis of the PK validation study with humanized dosing. Row A represents the plasma concentrations from the bloodstream infection model. Rows B and C show the plasma and ELF concentrations of the lung infection model.

For the lung infection model, the predicted peak concentrations in plasma after multiple dosing matched the observed concentrations well, suggesting that the volume of distribution was constant over time. However, the trough concentrations were slightly under-predicted, especially at 24 h, suggesting that the elimination half-life increased over time. Thus, clearance was estimated to decrease by 41% (i.e., from 7.44 mL/h for the first to 4.39 mL/h for the last dosing interval; Table 2). The resulting elimination half-life estimate of ~42 min during the first two dosing intervals increased to 54 min during the third and to 73 min during the last dosing interval (Fig. 5 and 6). The extent of ELF penetration (FELF: 0.604 for the multiple-dose PK validation study, Table 2) was comparable to that of the single dose PK study (0.727, Table 1). The BSV of both clearance (and volume of distribution) was considerably larger for the third and fourth dosing intervals of the PK validation study, compared to the BSV for the first and second dosing intervals (Table 2). This suggested that disease severity also caused a larger BSV.

The individual achieved AUC in the multiple-dose validation studies was (slightly) larger than the targeted AUC0-24h of 244 mg·h/L for the lung infection model (Table 3). Due to the smaller clearance and the decrease in clearance over time, the median (5th–95th percentile) of the AUC0-24h was 345 (308–411) mg·h/L in plasma and 208 (185–245) mg·h/L in ELF. For the bloodstream infection model, the targeted AUC0-24h was 296 mg·h/L, and the AUC0-6h of 244 (220–264) mg·h/L was comparable to the expected value. However, the decrease in clearance over time led to larger AUC0-6h, AUC6-12h, and AUC18-24h as well as a larger AUC0-24h of 741 (557–1,607) mg·h/L in plasma (Table 3). All median AUC0-24h in mice fell, however, within the 10th–90th percentiles of AUC0-24h in VABP patients (~179–851 mg·h/L, at a daily dose of 20 mg/kg of body weight) (6), equivalent to 224–1,064 mg·h/L at a daily dose of 25 mg/kg of body weight.

TABLE 3.

Amikacin area under the curve in the prospective validation studies for the bloodstream and the lung infection modele

| Matrix | Dose (mg/kg) | Parameter | Average ± SD (mg·h/L) |

CV | Median (5th–95th percentile) (mg·h/L) |

Predicted based on single-dose PK (mg·h/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloodstream infection model | ||||||

| Plasma | 117 (daily) | AUC0-24h | 857 ± 304a | 36%a | 741 (557–1,607)a | 296 |

| 72.7 at 0 h | AUC0-6h | 243 ± 14.6 | 6.0% | 244 (220–264) | 182d | |

| 21.9 at 6 h | AUC6-12h | 146b ± 14.1 | 9.7% | 141b (132–170) | 55.8b | |

| 13.3 at 12 h | AUC12-18h | 244b ± 274 | 112% | 136b (98.0–743) | 33.6b | |

| 9.64 at 18 h | AUC18-24h | 224b ± 153 | 68% | 162b (55.5–442) | 24.3b | |

| Lung infection model | ||||||

| Plasma | 96.7 (daily) | AUC0-24h | 350 ± 31.4a | 9.0%a | 345 (308–411)a | 244 |

| 63.0 at 0 h | AUC0-6h | 210 ± 9.02 | 4.3% | 210 (197–224) | 159d | |

| 16.4 at 6 h | AUC6-12h | 53.7c ± 3.03 | 5.6% | 53.8 (49.7–58.3) | 41.4 | |

| 10.2 at 12 h | AUC12-18h | 44.4c ± 22.3 | 50% | 37.1 (27.0–82.9) | 25.7 | |

| 7.17 at 18 h | AUC18-24h | 41.4c ± 21.4 | 52% | 38.1 (18.7–70.4) | 18.1 | |

| ELF | AUC0-24h | 210 ± 18.2a | 8.7%a | 208 (185–245)a | 177 | |

| AUC0-6h | 126 ± 7.53 | 6.0% | 126 (117–136) | 115d | ||

| AUC6-12h | 33.8c ± 3.18 | 9.4% | 33.3c (30.2–38.8) | 30.3 | ||

| AUC12-18h | 26.6c ± 12.7 | 48% | 22.0c (16.2–48.9) | 18.7 | ||

| AUC18-24h | 24.1c ± 11.2 | 46% | 23.0c (11.2–39.7) | 13.2 | ||

Summary statistics for the AUC0-24h were calculated based on a fully factorial evaluation (of all ~65,000 possible combinations) of the individual AUC0-6h, AUC6-12h, AUC12-18h, and AUC18-24h. During these four time intervals, 16 mice each contributed an observation, whereas the remaining 48 mice had no observation and thus contributed no information. Therefore, only 16 mice in each time interval contributed to the between-subject variability, and data from the respective 16 mice during each time interval were used for calculating the AUC0-24h. The latter was the sum of the four individual AUCs. By evaluating the summary statistics over all possible combinations, this approach provided realistic variability estimates.

The supplement doses at 6, 12, and 18 h were smaller than the initial dose at 0 h. Due to the decreasing clearance over time, the AUC6-12h, AUC12-18h, and AUC18-24h were higher than expected, especially for the bloodstream model.

The decrease in clearance over time was present but less extensive for the lung infection model compared to that of the bloodstream infection model. Therefore, the AUC6-12h, AUC12-18h, and AUC18-24h for the lung infection model were smaller than those in the bloodstream infection model.

The AUC0-6h was slightly smaller for the predictions based on the single-dose PK data compared to those of the multiple-dose PK data since the clearance after a single dose (9.93 mL/h, Table 1) was larger than the clearances from 0 to 6 h after multiple dosing (~7.4 mL/h, Table 2).

The last column shows the predicted AUC based on the single-dose PK data (Table 1; Fig. S3). As reference, the 10th–90th percentile of the AUC0-24h in plasma of VABP patients (at a dose of 20 mg/kg of body weight/day) is ~179–851 mg·h/L (6), equivalent to 224–1,064 mg·h/L at 25 mg/kg of body weight/day. SD, standard deviation; CV, coefficient of variation; ELF, lung epithelial lining fluid; and AUCX-Y, area under the concentration-time curve from time X to time Y.

DISCUSSION

This study defined and prospectively validated the first humanized amikacin dosage regimens for two infection models in immune-competent mice. We developed a new algorithm to match the peak, area, trough, and range of plasma concentrations. Population modeling showed that the PK in plasma and ELF was linear and that both infection models had the same clearance of 9.93 mL/h after single dosing. However, the volume of distribution was larger in the bloodstream compared to that in the lung infection model, resulting in a 25% longer half-life for the bloodstream model (Table 1). In the prospective validation of the humanized dosage regimens via multiple-dose PK studies, clearance was similar during the first 6-h dosing interval (7.35 mL/h for the bloodstream vs 7.44 mL/h for the lung model). However, clearance and volume of distribution decreased substantially (by ~80%) from the first to the last dosing interval due to the extensive severity of infection in the bloodstream model. In contrast, the volume of distribution was constant, and clearance only decreased by 41% between dosing intervals in the lung model (Table 2). In both models, the PK became more variable during the later dosing intervals (Table 3).

We have previously described that the severity of infection differs between both models. The bloodstream infection model progresses to moribund condition within 24 h (19), and mice become moribund due to sepsis. In contrast, mice infected using the lung model become moribund due to respiratory failure (19). Thus, differences in disease progression did seem to influence the extent of PK changes over 24 h (Table 2).

When attempting to match the drug exposures and concentration-time profiles between mice and patients, considering the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) parameter(s) that best predict efficacy is important. For aminoglycosides, the fAUC/MIC and fCmax/MIC best predict bacterial killing at 24 h in mice and outcomes in patients (10, 11). Consequently, the first step of matching the PK is to achieve the same unbound AUC in mice and patients. Lepak et al. (8) showed that the protein binding of amikacin in mice (24% bound) was similar to that in humans (~18% bound) (33, 34). Matching the fAUC/MIC has been done previously by giving 293 mg amikacin/kg of body weight every 6 h (q6h) in mice (daily dose: 1,172 mg/kg of body weight) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (9), and by giving daily doses of 6.25, 25, 100, 400, or 1,600 mg/kg of body weight/day via q6h dosing against A. baumannii (8). At sufficient daily doses, using the same dose at 0, 6, 12, and 18 h provides effective drug concentrations throughout a human 24-h dosing interval. However, it does not match the shape of the plasma concentration-time profiles (i.e., the peak-trough falloff over 24 h) for q24h dosing in patients. Dosing q6h in mice is better than q24h dosing for antibiotics with a short half-life (e.g., <1 h), as q24h dosing would result in a long duration of sub-therapeutic concentrations, which likely leads to bacterial regrowth (35).

To improve this AUC-matching algorithm, the first studies employing humanized dosing aimed to match the human plasma concentration-time profiles at every single time point in mice, rats, and rabbits (12, 36–38). Computer-controlled infusion pumps were used in rats and rabbits for aminoglycosides and β-lactams (36–38). In mice, matching was accomplished by injecting decreasing, fractionated imipenem doses subcutaneously at 15-min intervals (12). These approaches are powerful but injecting every 15 min may cause animal welfare issues and is resource intensive. Thus, there is a need to develop more practical and efficient humanized dosage regimens.

We aimed to match the shape of the plasma concentration-time profiles after q24h dosing of amikacin in patients. This was accomplished by giving a larger initial dose at 0 h and smaller doses at 6, 12, and 18 h in mice (Fig. 5), like prior studies on tobramycin and plazomicin (20, 39). After determining the population PK in mice, this was achieved by simulating murine plasma concentrations and comparing them with the median, 10th, and 90th percentiles of plasma concentrations in critically ill patients (Fig. 5) (6, 7). Thereby, we aimed to match the AUC, the peak, and trough concentrations, as well as the peak-to-trough falloff during a 24-h dosing interval in humans. We further considered the range of plasma concentrations and aimed to have the typical concentrations in mice not exceed the 90th–95th percentile of the human concentrations. Thereby, the present study proposes a novel approach to match all four criteria [i.e., the peak, area (AUC), trough, and range of plasma concentrations].

The proposed model-based PATR-matching algorithm provides a stepwise framework of how to humanize dosage regimens to the extent feasible in mice. This approach mirrors the features of the plasma concentration-time profiles in patients that are most critical for the efficacy of the studied antibiotics at their clinical dosage regimens. By matching these four features of human PK profiles, the developed humanized dosage regimens are expected to yield clinically relevant predictions in future efficacy studies of amikacin combination dosage regimens. Future research is needed to evaluate whether glomerular filtration, tubular secretion, and re-absorption are affected by the infection to a similar degree for aminoglycosides and antibiotics used in combination (e.g., β-lactams).

Employing optimal design methodology allows one to identify the most informative sampling times across a range of doses (and given the sensitivity of the available bioanalytical assay) for precise estimation of PK parameters. This integrated translational model-based approach can efficiently provide feasible study designs for mouse PK validation and efficacy studies. Thereby, this algorithm robustly characterizes the PK, while minimizing the number of animals used.

Amikacin had considerably shorter half-lives in mice compared to those in patients. Within the constraints of q6h dosing, the short half-life in mice caused the trough concentrations to be lower than the 10th percentile of plasma concentrations in patients (Fig. 5). This could be improved by giving five or six doses over 24 h but may cause animal welfare issues. With clearance decreasing over time (Table 2), the observed trough concentrations in mice at 18 and 24 h were higher than the predicted troughs (Fig. 5), and the AUC12-18h and AUC18-24h were larger (Table 3). The 36–48 min terminal amikacin half-life in mice (Table 1) was 6–11 times shorter than the 5–6.8 h half-life in patients (4–6).

Earlier studies reported a half-life of 45–56 min and clearance of 5.8 mL/h in infected mice (40, 41), as well as a half-life of 17–52 min and clearance of 5.3–35 mL/h in non-infected mice (assuming a weight of 25 g) (42–45). Craig et al. reported half-lives of 18.5–32.5 min and clearances of 11.7–25.0 mL/h in infected, neutropenic mice with normal renal function. For renally impaired mice, the half-life was longer (93.3–121 min) and clearance was smaller (2.93–5.06 mL/h) (46). Therefore, our PK results in infected mice (Tables 1 and 2) fell within the range of half-lives and clearances reported previously.

It is further important to consider the extent and rate of ELF penetration in mice and patients (Fig. S4). A non-compartmental PK analysis by Lepak et al. (8) showed an ELF-to-plasma AUC0-24h ratio in infected mice of 0.8 ± 0.14 (average ± SD) independent of dose. We estimated a ratio (FELF) of 0.727 via population PK modeling for the single dose range study (Table 1) and a ratio of 0.604 for the sparse sampling PK validation study with multiple dosing (Table 2). Previously, an ELF-to-plasma AUC ratio of 0.49 has been reported in normal rats (without infection) and a ratio of 0.27 in rats with pulmonary fibrosis (47). A recent population PK modeling analysis of the time course of ELF penetration in neonates and adult patients (Fig. S4) (48–50) estimated an ELF-to-plasma equilibration half-life of 5.8 h, which was substantially (~12-fold) longer than that in mice (21.9–36.4 min; Tables 1 and 2). Thus, system hysteresis was more pronounced in patients than in mice (Fig. S3 and S4) (48, 49, 51, 52). However, the mean ELF-to-plasma AUC ratio (FELF) is 0.502 in patients (48, 49), which was comparable to that in infected mice [0.727 and 0.604, Tables 1 and 2; and 0.8 ± 0.14 by Lepak et al. (8)]. These estimates were consistent with mouse ELF penetration results for three other aminoglycosides (with AUC ratios of 0.60–0.88) (50). Thus, the ELF peak concentrations were blunted [Fig. 4 and results by Tayman et al. (48)], but the overall drug exposure and the extent of penetration in ELF were comparable between mice and humans.

As limitations of the present study, we did not quantify the protein binding of amikacin in mouse plasma, which was similar to that in humans (8, 33, 34). Furthermore, we only studied one isolate that had a high amikacin MIC (128 mg/L); studying more isolates would strengthen the conclusions about the impact of infection on PK. The later dosing intervals of our PK validation study displayed extensive variability with a decrease of clearance and volume of distribution over time (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 5 and 6; Fig. S7). Future research is warranted to validate the decrease of renal clearance over time (e.g., using creatinine or other markers). This was likely caused by an increasing severity of infection, especially for the bloodstream model. However, it is less clear whether the high concentrations (e.g., from 18 to 24 h, Table 3) contribute to antibacterial efficacy or whether the infection has already progressed too far for these late, high drug exposures to contribute to antibacterial efficacy and mouse survival. Future research is further warranted to compare mouse dosage regimens that are humanized based on single-dose PK data or that consider the change of PK parameters over time due to progressive disease severity. In the present study, we humanized based on single-dose PK and observed disease-related changes in the multiple-dose PK validation studies.

In summary, this study provides the first prospectively validated humanized amikacin dosage regimens in immune-competent murine bloodstream and lung infection models. We developed a new PATR-matching algorithm, which considers the peak, area, trough, and range of plasma concentrations in patients. This algorithm accounted for the 6–11 times shorter half-lives in mice compared to those in patients based on population PK modeling. Clearance and volume of distribution decreased extensively over 24 h due to the increasing severity of infection in the bloodstream infection model. The extent of ELF penetration characterized by the ELF-to-plasma AUC ratio in mice (60%–80%) was similar to that in patients (50%) (50). This study enhanced our understanding of the amikacin PK in two murine infection models. Future research is warranted to evaluate a range of bacterial isolates that can cause infections in patients as well as their impact on the PK and efficacy using different infection models. Such studies should assess a selection of isolates with a wide range of amikacin MICs that capture the clinically most important and prevalent resistance mechanisms for A. baumannii and other pathogens (53–55). The developed population PK models, PATR-matching approach, and prospectively validated humanized dosage regimens will benefit further translational research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their critical review and feedback: Drs. John Farley, Thushi Amini, James Byrne, Simone Shurland, Abhay Joshi, and Ursula Waack.

This study was supported by contract HHSF223201710199C (to B.M.L., B.S., J.B.B., G.L.D, A.L., and R.A.B.) from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the FDA or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Presented at: Parts of the present work have been presented at the FDA workshop on “Advancing Animal Models for Antibacterial Drug Development Workshop,” FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in Silver Spring, MD, USA on 5 March 2020.

Contributor Information

Brian M. Luna, Email: brian.luna@usc.edu.

Jürgen B. Bulitta, Email: jbulitta@cop.ufl.edu.

James E. Leggett, Providence Portland Med Ctr, Portland, Oregon, USA

ETHICS APPROVAL

All animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol 20810) at the University of Southern California.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01394-23.

Supplementary materials, model diagnostics figures, and simulation code.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zavascki AP, Klee BO, Bulitta JB. 2017. Aminoglycosides against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the critically ill: the pitfalls of aminoglycoside susceptibility. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 15:519–526. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2017.1316193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barclay ML, Kirkpatrick CM, Begg EJ. 1999. Once daily aminoglycoside therapy. Is it less toxic than multiple daily doses and how should it be monitored? Clin Pharmacokinet 36:89–98. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199936020-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Tulkens PM. 1999. Aminoglycosides: nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:1003–1012. doi: 10.1128/AAC.43.5.1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van der Auwera P. 1991. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of single daily dose amikacin. J Antimicrob Chemother 27 Suppl C:63–71. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.suppl_c.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duong A, Simard C, Wang YL, Williamson D, Marsot A. 2021. Aminoglycosides in the intensive care unit: what is new in population PK modeling? Antibiotics (Basel) 10:507. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10050507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burdet C, Pajot O, Couffignal C, Armand-Lefèvre L, Foucrier A, Laouénan C, Wolff M, Massias L, Mentré F. 2015. Population pharmacokinetics of single-dose amikacin in critically ill patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s00228-014-1766-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Delattre IK, Musuamba FT, Nyberg J, Taccone FS, Laterre PF, Verbeeck RK, Jacobs F, Wallemacq PE. 2010. Population pharmacokinetic modeling and optimal sampling strategy for Bayesian estimation of amikacin exposure in critically ill septic patients. Ther Drug Monit 32:749–756. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181f675c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lepak AJ, Trang M, Hammel JP, Sader HS, Bhavnani SM, VanScoy BD, Pogue JM, Ambrose PG, Andes DR, Antimicrobial Susceptibility T. 2023. Development of modernized Acinetobacter baumannii susceptibility test interpretive criteria for recommended antimicrobial agents using pharmacometric approaches. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 67:e0145222. doi: 10.1128/aac.01452-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Warawa JM, Duan X, Anderson CD, Sotsky JB, Cramer DE, Pfeffer TL, Guo H, Adcock S, Lepak AJ, Andes DR, Slone SA, Stromberg AJ, Gabbard JD, Severson WE, Lawrenz MB. 2022. Validated preclinical mouse model for therapeutic testing against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0269322. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02693-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bland CM, Pai MP, Lodise TP. 2018. Reappraisal of contemporary pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles for informing aminoglycoside dosing. Pharmacotherapy 38:1229–1238. doi: 10.1002/phar.2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ambrose PG, Bhavnani SM, Rubino CM, Louie A, Gumbo T, Forrest A, Drusano GL. 2007. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial therapy: it's not just for mice anymore. Clin Infect Dis 44:79–86. doi: 10.1086/510079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flückiger U, Segessenmann C, Gerber AU. 1991. Integration of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of imipenem in a human-adapted mouse model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 35:1905–1910. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.9.1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deziel MR, Heine H, Louie A, Kao M, Byrne WR, Basset J, Miller L, Bush K, Kelly M, Drusano GL. 2005. Effective antimicrobial regimens for use in humans for therapy of Bacillus anthracis infections and postexposure prophylaxis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:5099–5106. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.5099-5106.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiao Y, Yan J, Vicchiarelli M, Sutaria DS, Lu P, Reyna Z, Spellberg B, Bonomo RA, Drusano GL, Louie A, Luna BM, Bulitta JB. 2023. Individual components of polymyxin B modeled via population pharmacokinetics to design humanized dosage regimens for a bloodstream and lung infection model in immune-competent mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 67:e0019723. doi: 10.1128/aac.00197-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sandri AM, Landersdorfer CB, Jacob J, Boniatti MM, Dalarosa MG, Falci DR, Behle TF, Bordinhão RC, Wang J, Forrest A, Nation RL, Li J, Zavascki AP. 2013. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous polymyxin B in critically ill patients: implications for selection of dosage regimens. Clin Infect Dis 57:524–531. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Craig WA. 1998. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis 26:1–10. doi: 10.1086/516284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bulitta JB, Ly NS, Landersdorfer CB, Wanigaratne NA, Velkov T, Yadav R, Oliver A, Martin L, Shin BS, Forrest A, Tsuji BT. 2015. Two mechanisms of killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by tobramycin assessed at multiple inocula via mechanism-based modeling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2315–2327. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04099-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. El-Shazly S, Dashti A, Vali L, Bolaris M, Ibrahim AS. 2015. Molecular epidemiology and characterization of multiple drug-resistant (MDR) clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Infect Dis 41:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luna BM, Yan J, Reyna Z, Moon E, Nielsen TB, Reza H, Lu P, Bonomo R, Louie A, Drusano G, Bulitta J, She R, Spellberg B. 2019. Natural history of Acinetobacter baumannii infection in mice. PLoS One 14:e0219824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Louie A, Liu W, Fikes S, Brown D, Drusano GL. 2013. Impact of meropenem in combination with tobramycin in a murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2788–2792. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02624-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aoki Y, Sundqvist M, Hooker AC, Gennemark P. 2016. PopED lite: an optimal design software for preclinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 127:126–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. He J, Gao S, Hu M, Chow D-L, Tam VH. 2013. A validated ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for the quantification of polymyxin B in mouse serum and epithelial lining fluid: application to pharmacokinetic studies. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1104–1110. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bowen CL, Licea-Perez H. 2013. Development of a sensitive and selective LC-MS/MS method for the determination of urea in human epithelial lining fluid. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 917–918:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Landersdorfer CB, Bulitta JB, Kinzig M, Holzgrabe U, Sörgel F. 2009. Penetration of antibacterials into bone: pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and bioanalytical considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet 48:89–124. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Landersdorfer CB, Kinzig M, Bulitta JB, Hennig FF, Holzgrabe U, Sörgel F, Gusinde J. 2009. Bone penetration of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid evaluated by population pharmacokinetics and Monte Carlo simulation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:2569–2578. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01119-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Landersdorfer CB, Kinzig M, Hennig FF, Bulitta JB, Holzgrabe U, Drusano GL, Sörgel F, Gusinde J. 2009. Penetration of moxifloxacin into bone evaluated by Monte Carlo simulation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:2074–2081. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01056-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bulitta JB, Duffull SB, Kinzig-Schippers M, Holzgrabe U, Stephan U, Drusano GL, Sörgel F. 2007. Systematic comparison of the population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of piperacillin in cystic fibrosis patients and healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:2497–2507. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01477-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bulitta JB, Okusanya OO, Forrest A, Bhavnani SM, Clark K, Still JG, Fernandes P, Ambrose PG. 2013. Population pharmacokinetics of fusidic acid: rationale for front-loaded dosing regimens due to autoinhibition of clearance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:498–507. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01354-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bulitta JB, Bingölbali A, Shin BS, Landersdorfer CB. 2011. Development of a new pre- and post-processing tool (SADAPT-TRAN) for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling in S-ADAPT. AAPS J 13:201–211. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9257-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bulitta JB, Landersdorfer CB. 2011. Performance and robustness of the Monte Carlo importance sampling algorithm using parallelized S-ADAPT for basic and complex mechanistic models. AAPS J 13:212–226. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9258-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bauer RJ, Guzy S, Ng C. 2007. A survey of population analysis methods and software for complex pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic models with examples. AAPS J 9:E60–83. doi: 10.1208/aapsj0901007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marsot A, Guilhaumou R, Riff C, Blin O. 2017. Amikacin in critically ill patients: a review of population pharmacokinetic studies. Clin Pharmacokinet 56:127–138. doi: 10.1007/s40262-016-0428-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Segal JL, Brunnemann SR, Eltorai IM. 1990. Pharmacokinetics of amikacin in serum and in tissue contiguous with pressure sores in humans with spinal cord injury. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 34:1422–1428. doi: 10.1128/AAC.34.7.1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brunnemann SR, Segal JL. 1991. Amikacin serum protein binding in spinal cord injury. Life Sci 49:L1–5. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90030-f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leggett JE, Fantin B, Ebert S, Totsuka K, Vogelman B, Calame W, Mattie H, Craig WA. 1989. Comparative antibiotic dose-effect relations at several dosing intervals in murine pneumonitis and thigh-infection models. J Infect Dis 159:281–292. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.2.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bugnon D, Potel G, Caillon J, Baron D, Drugeon HB, Feigel P, Kergueris MF. 1998. In vivo simulation of human pharmacokinetics in the rabbit. Bull Math Biol 60:545–567. doi: 10.1006/bulm.1997.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Woodnutt G, Berry V, Mizen L. 1992. Simulation of human serum pharmacokinetics of cefazolin, piperacillin, and BRL 42715 in rats and efficacy against experimental intraperitoneal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 36:1427–1431. doi: 10.1128/AAC.36.7.1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Woodnutt G, Catherall EJ, Kernutt I, Mizen L. 1988. Temocillin efficacy in experimental Klebsiella pneumoniae meningitis after infusion into rabbit plasma to simulate antibiotic concentrations in human serum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 32:1705–1709. doi: 10.1128/AAC.32.11.1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Drusano GL, Liu W, Fikes S, Cirz R, Robbins N, Kurhanewicz S, Rodriquez J, Brown D, Baluya D, Louie A. 2014. Interaction of drug- and granulocyte-mediated killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a murine pneumonia model. J Infect Dis 210:1319–1324. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Máthé A, Szabó D, Anderlik P, Rozgonyi F, Nagy K. 2007. The effect of amikacin and imipenem alone and in combination against an extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strain. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 58:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Joly-Guillou ML, Wolff M, Farinotti R, Bryskier A, Carbon C. 2000. In vivo activity of levofloxacin alone or in combination with imipenem or amikacin in a mouse model of Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother 46:827–830. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.5.827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Szabó D, Máthé A, Filetóth Z, Anderlik P, Rókusz L, Rozgonyi F. 2001. In vitro and in vivo activities of amikacin, cefepime, amikacin plus cefepime, and imipenem against an SHV-5 extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:1287–1291. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1287-1291.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Renneberg J, Walder M. 1989. Postantibiotic effects of imipenem, norfloxacin, and amikacin in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 33:1714–1720. doi: 10.1128/AAC.33.10.1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lipski S, Gasiewski A, Chaś J. 1992. Pharmacokinetics of amikacin in gamma-irradiated mice. Pol J Pharmacol Pharm 44:469–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hosokawa H, Nyu S, Nakamura K, Mifune K, Nakano S. 1993. Circadian variation in amikacin clearance and its effects on efficacy and toxicity in mice with and without immunosuppression. Chronobiol Int 10:259–270. doi: 10.1080/07420529309059708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Craig WA, Redington J, Ebert SC. 1991. Pharmacodynamics of amikacin in vitro and in mouse thigh and lung infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 27 Suppl C:29–40. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.suppl_c.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ni W, Yang D, Mei H, Zhao J, Liang B, Bai N, Chai D, Cui J, Wang R, Liu Y. 2017. Penetration of ciprofloxacin and amikacin into the alveolar epithelial lining fluid of rats with pulmonary fibrosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01936-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01936-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tayman C, El-Attug MN, Adams E, Van Schepdael A, Debeer A, Allegaert K, Smits A. 2011. Quantification of amikacin in bronchial epithelial lining fluid in neonates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3990–3993. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00277-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Najmeddin F, Shahrami B, Azadbakht S, Dianatkhah M, Rouini MR, Najafi A, Ahmadi A, Sharifnia H, Mojtahedzadeh M. 2020. Evaluation of epithelial lining fluid concentration of amikacin in critically ill patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Intensive Care Med 35:400–404. doi: 10.1177/0885066618754784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shin E, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Lang Y, Sayed ARM, Werkman C, Jiao Y, Kumaraswamy M, Bulman ZP, Luna BM, Bulitta JB. 2024. Improved characterization of aminoglycoside penetration into human lung epithelial lining fluid via population pharmacokinetics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. doi: 10.1128/aac.01393-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rodvold KA, George JM, Yoo L. 2011. Penetration of anti-infective agents into pulmonary epithelial lining fluid: focus on antibacterial agents. Clin Pharmacokinet 50:637–664. doi: 10.2165/11594090-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Drwiega EN, Rodvold KA. 2022. Penetration of antibacterial agents into pulmonary epithelial lining fluid: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet 61:17–46. doi: 10.1007/s40262-021-01061-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Soon RL, Ly NS, Rao G, Wollenberg L, Yang K, Tsuji B, Forrest A. 2013. Pharmacodynamic variability beyond that explained by MICs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1730–1735. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01224-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bruhn KW, Pantapalangkoor P, Nielsen T, Tan B, Junus J, Hujer KM, Wright MS, Bonomo RA, Adams MD, Chen W, Spellberg B. 2015. Host fate is rapidly determined by innate effector-microbial interactions during Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia. J Infect Dis 211:1296–1305. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Talyansky Y, Nielsen TB, Yan J, Carlino-Macdonald U, Di Venanzio G, Chakravorty S, Ulhaq A, Feldman MF, Russo TA, Vinogradov E, Luna B, Wright MS, Adams MD, Spellberg B. 2021. Capsule carbohydrate structure determines virulence in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS Pathog 17:e1009291. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials, model diagnostics figures, and simulation code.