Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death globally for men and women. Premenopausal women have a lower incidence of hypertension and other cardiovascular events than men of the same age, but diminished sex differences after menopause implicates 17-beta-estradiol (E2) as a protective agent. The cardioprotective effects of E2 are mediated by nuclear estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) and a G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER). This review summarizes both established as well as emerging estrogen-mediated mechanisms that underlie sex differences in the vasculature during hypertension and CVD. In addition, remaining knowledge gaps inherent in the association of sex differences and E2 are identified, which may guide future clinical trials and experimental studies in this field.

Keywords: sex differences, arterial stiffness, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, circadian rhythms, obesity, salt-sensitive

1. Introduction

Hypertension poses a major public health concern, both due to the volume of diagnoses and the associated comorbidities. These conditions primarily include other cardiovascular diseases (CVD) such as stroke, coronary artery disease, heart failure, arrhythmias, and peripheral vascular disease. Overall, deaths caused by hypertension or diseases stemming from this condition rose by 65.3% from 2009 to 2019 in the United States1. The incidence of hypertension increases dramatically during the lifespan in both men and women, with diagnosis in women surpassing men after midlife. Premenopausal women experience less hypertension and cardiovascular incidents than men of the same age1, but this cardioprotection is lost after menopause. In fact, postmenopausal women have a higher risk for hypertension and CVD than age-matched men, suggesting that 17β-estradiol (E2) is a protective factor.

During the female reproductive years, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels rise during the follicular phase and then decrease as E2 levels rise in the mid-to-late follicular phase2. When women reach menopause at the average age of 52 years, endogenous E2 levels rapid decline by more than 60% while FSH/LH levels rise and promote an abundance of androgen2–4. The oscillations in circulating E2 and androgens during the menopausal transition (usually lasting between 2–7 years) promotes vasomotor symptoms including hot flashes, night sweats, weight gain, and sleep deprivation and may influence the regulation blood pressure (BP)5,6. Recent data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) shows that a menopause-induced increase in blood pressure occurs only in a subset of women and is associated with age at menopause and levels of follicle-stimulating hormone7. Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) effectively reduces these symptoms of menopause but has been linked to adverse effects such as stroke and coronary heart disease8. While these conditions are dangerous, these adverse effects are dramatically reduced when therapy is initiated within 5 years of the menopausal transition9.

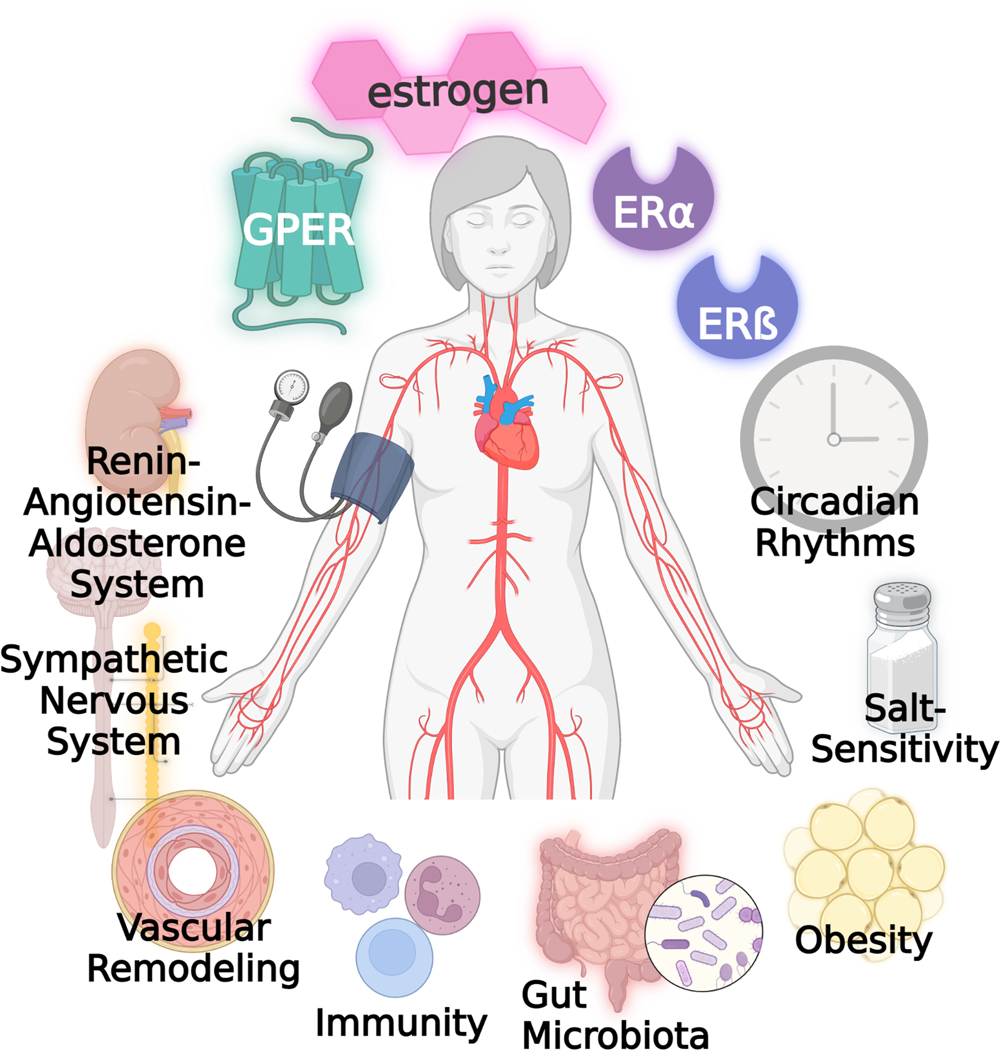

In contrast to the somewhat conflicting results in clinical studies, animal data strongly support the favorable effect of E2 on cardiovascular health. Female rodents are protected from increased BP, vascular injury, and heart failure compared to males, but this cardioprotection is abolished after ovariectomy (OVX) and rescued by estrogen treatment10–12. Additionally, women who undergo oophorectomy are more likely to be diagnosed with hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and stroke due to the sudden loss of endogenous estrogen13–15. These are clear indicators that estrogen plays a significant role in the sex differences in hypertension and CVD. Here, we provide a comprehensive overview of the literature regarding the direct mechanisms of estrogen receptors in the cardiovascular system and their interactions with hypertensive mechanisms (Figure). Furthermore, we identify remaining knowledge gaps, which may guide future clinical trials and experimental studies in this field.

Figure:

The protective cardiovascular actions of estrogen are mediated by nuclear receptors ERα and ERβ as well as the membrane G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER). In addition to the direct actions of these estrogen receptors on vascular tone, estrogen interacts with a plethora of other systems and conditions that promote hypertension including the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, sympathetic nervous system, vascular remodeling, obesity, immunity, gut microbiota, salt-sensitivity, and circadian rhythms.

2. Cardiovascular estrogen receptors and direct signaling mechanisms

E2 is a sex hormone associated with female and male reproduction as well as other functions in the vascular, neuroendocrine, and immune systems. Pioneering work by Edward Doisy and Alfred Butenandt led to the discovery of estrone, followed by E216. Elwood Jensen discovered a binding site for E2 in female reproductive tissues, later identified as estrogen receptor alpha (ERα)17,18. The second nuclear estrogen receptor was cloned by Jan-Åke Gustafsson in the mid-1980’s and named estrogen receptor beta (ERβ). Original characterization of E2 signaling revealed binding in the cytosol, receptor dimerization, and nuclear translocation. The ligand-receptor complexes then bind estrogen response elements in the DNA to regulate gene transcription19. Estrogen receptor complexes also interact with coactivators and corepressors to enhance or impede gene transcription, allowing the clinical development of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), which activate nuclear estrogenic signaling in a tissue-specific manner20. Estrogen receptors are localized in the cytosol, nucleus, and membrane compartments of many cell types including cardiovascular tissues such as the vasculature and heart21–23. Studies have also revealed E2 binding and receptor localization in plasma membranes24–26 and caveola27,28, suggesting that estrogen receptors also elicit nongenomic signaling.

2.1. Cardiovascular mechanisms of ERα in females

ERα is abundant in the uterus, followed by the kidney, and is similarly expressed in female and male tissues22. Although growth and development are possible in the absence of ERα, reproductive function is heavily compromised29. In the vasculature, ERα is localized in both endothelial and smooth cells, but expression may vary with sex, age, and vascular bed21,22,30,31. ERα expression varies with circulating estrogen levels throughout the menstrual cycle and is significantly decreased after menopause32. ERα activation plays critical role in cardiovascular protection against hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, arteriosclerosis, heart failure, and ischemia/injury in the myocardium33,34.

ERα deletion and aging increase the propensity for hypertension35. In rodents, ERα RNA expression is reduced in the aortas of middle-aged female mice compared with young females21. OVX in female rats decreases endothelial ERα and disrupts its ability to induce nitric oxide signaling. Moreover, the reintroduction of E2 is unable to rescue endothelial dysfunction four months post-OVX36,37. The selective ERα agonist Cpd1471 improves endothelial dysfunction after OVX in spontaneously hypertensive rats38. In angiotensin II-induced hypertension, female ERα knockout (αERKO) mice have higher mean arterial pressure (MAP) than wildtype, which is also exacerbated by a loss of ovarian hormones39.

Both membrane and nuclear mechanisms are implicated in the protective effects of ERα on vascular function in females. There are three identified ERα isoforms (ERα66, ERα46, and ERα36)40 which induce endothelial nitric oxide signaling to provide protection against hypertension28. ERα also augments the release of other vasodilator agents such as prostacyclin and decreases the production of vasoconstrictors such as angiotensin II (Ang II) and endothelin41. However, studies in mice lacking the nuclear activating function AF2 indicate that nuclear ERα signaling underlies the ability of estrogen to mitigate Ang II-induced hypertension35. Recently, the H2NESKI mouse line was generated to investigate only non-genomic signaling due to the lack of a nuclear export signal in ERα. The phenotype of H2NESKI mice is very similar to αERKO mice except for enhanced reendothelialization, which interestingly occurs even in the absence of endogenous estrogen42. Taken together, these studies indicate a role for ERα in estrogen’s protective effects, especially with regards to endothelial function.

2.2. Cardiovascular mechanisms of ERα in males

Limited or conflicting data is available regarding the cardioprotective properties of E2 in males. The primary source of E2 in men is from aromatization of testosterone. An imbalance in androgen metabolites and low levels of E2 are associated with an increased risk of CVD and mortality among men43–45. In humans, a single nucleotide polymorphism in ERα contributes to SBP regulation in men but not in women46. ERα is also expressed in male smooth muscle and endothelial cells47,48. E2 inhibits proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells with similar responses in both males and females48. Chronic supplementation of E2 in aged men does not change flow-mediated vasodilation in the brachial artery or impact nitric oxide metabolites in the blood compared with aged-matched women49. In contrast, long-term E2 enhances flow-mediated dilation in the brachial artery of age-matched men, male-to-female transexuals, and premenopausal women50. Low dose E2 treatment in hypogonadal men (mean age 68 years old) reduces SBP and DBP, mitigates vasoconstriction in response to Ang II and norepinephrine, and enhances nitric oxide release51. E2 supplementation has beneficial effects on the vasculature and ameliorates cardiac dysfunction in male mice with myocardial infarction52, and deletion of membrane ERα induces similar endothelial dysfunction as seen in aged mesenteric arteries53. Although these findings demonstrate potential cardiovascular protection by E2 in males, there is no evidence that estrogen supplementation in older men is associated with a reduced risk of hypertension or CVD.

2.3. Cardiovascular mechanisms of ERβ

The expression of ERβ in peripheral cardiovascular tissues is debatable, with some studies showing no or little expression in the heart, kidney, and aorta22,23. However, studies from female ERβ knockout mice or administration of an ERβ agonist suggests this receptor provides protection against ischemia/reperfusion injury through upregulation of cardioprotective genes and activation of nitric oxide54,55. Since ERβ expression is significantly increased in male rats following vascular injury56, the receptor may be inducible by disease. ERβ is expressed at higher levels in the brain22, where its signaling in the paraventricular nucleus is important for counteracting Ang II-induced hypertension in perimenopausal mice57. In rats, ERβ activation in the brainstem is protective against aldosterone-induced hypertension58.

A variant of ERβ is associated with hypertension in women, although men were not included in the study59. It remains to be explored whether the single nucleotide polymorphism of ERβ in hypertensive young women interacts with ovarian hormones. Justin and colleagues established a role for the ERβ variant in DBP regulation in men46. However, Ogawa et al. showed single nucleotide polymorphism in Erβ is associated with SBP in Japanese women60. The ERβ genetic variation is also associated with salt-sensitive hypertension in premenopausal women but not in men or postmenopausal women61. While the role of ERβ is not as clear as the other nuclear estrogen receptor, its ability to protect in specific tissues and diseases may prove to be beneficial when designing unique therapies to target this pathway.

2.4. Cardiovascular mechanisms of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER)

Discovery of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) transformed the classical concept of estrogen receptors signaling via nuclear mechanisms62. GPER is localized to the plasma membrane and/or the endoplasmic reticulum and is activated by E2 rapidly to turn on non-genomic signaling26,62. GPER activates second messengers including cyclic AMP to induce vasorelaxation but also has downstream influences on gene transcription63,64. Other vascular signaling mechanisms of GPER include intracellular calcium mobilization and phosphorylation of ERK1/265,66. GPER is ubiquitously expressed, with highest levels detected in brain22, and is regulated in cardiovascular tissues in a sex- and age-specific manner21,22.

GPER induces beneficial effects in a variety of cardiometabolic conditions including hypertension67–69, arterial stiffening64,70, stroke71, vascular oxidative stress64,72, and obesity and diabetes65,73,74. Our laboratory and others demonstrate that the GPER agonist G-1 induces rapid non-genomic signaling which is particularly desirable in endothelial-mediated vasorelaxation and the regulation of SBP65,67,75. GPER decreases with aging and is associated with a decline in the vascular response to E221,76. A single nucleotide variant of GPER is associated with higher MAP, SBP, and DBP in young women77. In OVX rats, GPER plays a cardioprotective role particularly with regards to diastolic function78,79, presumably through its ability to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress80–82. They mechanisms may also be involved in GPER-mediated protection against atherosclerosis41 and kidney damage83,84.

These explorations of GPER throughout the cardiovascular system identify this receptor as a plausible target for treating female CVD, but the potential in males is less clear72,85. Acute administration of E2 attenuates vasoconstriction in coronary arteries from women but not men86. In contrast, intravenous administration of conjugated E2 enhances male coronary blood flow in response to acetylcholine after 15 minutes of intervation87–89. These findings indicate discrepancies regarding the nongenomic effect of E2 and the potential actions of GPER in male vascular cells.

3. Interactions of estrogen with other hypertensive mechanisms

In addition to direct actions of E2 on cardiovascular tissues through nuclear and non-nuclear receptors, this predominant female sex hormone has a plethora of interactions with other hormone systems as well as physiological processes known or hypothesized to impact the regulation of blood pressure. E2 alters the expression of hormone receptors and growth factors and protects from injuries or disorders that promote hypertension. Therefore, this section will explore these interactions with other mechanisms that may be related to the development of hypertension and are potential therapeutic targets.

3.1. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS) system

The RAAS and sympathetic nervous system play crucial roles in the regulation of BP, and imbalances in these systems contribute to hypertension. Both contain vasoconstrictor and vasodepressor mechanisms, and the resulting output is related to the relative expression and activity of the components of each arm of the system. In the RAAS, the vasoconstrictor components include the preprohormone angiotensinogen, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), the peptide angiotensin II (Ang II), and the Ang II type 1 receptor (AT1R)90. Components of the RAAS which counteract increased BP include angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the Ang II type 2 receptor (AT2R), and the Ang II metabolite Ang-(1–7) as well as its receptor (MasR). Similarly, the sympathetic nervous system contains both alpha adrenergic receptors (αAR) that promote vasoconstriction and beta-adrenergic receptors (βAR) that promote vasorelaxation. In both systems, females are associated with enhanced vasodepressor mechanisms while males have higher activity of vasoconstrictor components91,92.

Numerous studies on animal models of RAAS activation suggest that estrogen augments the ACE2-Ang(1–7)-MasR/AT2R pathways to induce cardiovascular protection while testosterone upregulates the ACE-AngII-AT1R axis91. In the spontaneously hypertensive rat model, Ang II-induced vasoconstriction is enhanced in OVX female arteries and associated with greater AT1R (vasoconstrictor) and lower AT2R (vasodilator) expression93. Moreover, these alterations are reversed by in vivo E2 replacement. In the mRen2.Lewis congenic rat, a model of renin overexpression, OVX increases SBP in female rats to a similar level as observed in males and elevates circulating Ang II and ACE activity while reducing Ang-(1–7)94,95. Interestingly, these protective effects of estrogen on the RAAS and SBP occur despite the fact that the angiotensinogen gene contains an estrogen response element which upregulates expression of this preprohormone96. The ability of estrogen to impact tissue expression of other components of the RAAS is not associated with direct ER binding to its response element and also shows tissue-specificity, with the greater regulation in kidney versus lung or heart97,98. Clinical studies confirm that estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women increases angiotensinogen but suppresses other vasoconstrictor components such as renin and ACE99,100. Importantly, differences in RAAS components may lead to varying therapeutic efficacy for antihypertensive medications in men versus women or pre- versus postmenopausal women101. ACE inhibitors, for example, reduce cardiovascular risk to a greater extent in elderly male versus female hypertensive patients, perhaps due to greater activity of this enzyme102.

3.2. Sympathetic nervous system

Reproductive hormones also modulate sympathetic nervous system activity. In response to a mental stressor, postmenopausal women display enhanced SBP and norepinephrine responses, while E2 administration in perimenopausal women attenuates the vasoconstriction to norepinephrine103,104. Animal studies show that greater contraction in male versus female arteries in response to αAR stimulation, while the opposite is found for βAR responses105,106. Some but not all studies correlate these findings with estrogenic regulation of adrenergic receptors, where βAR are enhanced while αAR are downregulated105,107,108. In fact, hot flashes are a symptom of estrogen loss during perimenopause that are associated with increased αAR activation109. While men have overall higher levels of muscle sympathetic nerve activity, the role of hormones in this sex difference is made evident by changes across the menstrual cycle110,111. However, women on oral contraceptives display a paradoxical vasodilation in response to this stressor compared with non-users112. Baroreceptor dysfunction also contributes to hypertension, and an impact of estrogen on this reflex is observed in both animal and human studies113. In anesthetized rats, baroreflex sensitivity is increased by OVX and restored by E2 treatment. In postmenopausal women, sensitivity and heart rate variability are both higher in women taking menopausal hormone therapy versus controls114. Taken together, these data indicate interactions between E2 and sympathetic function in women that may underlie increases in hypertension.

3.3. Vascular remodeling

In the vasculature, aging is a complex molecular mechanism process, and sex hormones and genetic factors contribute to the vascular aging phenotype. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play an essential role in vascular remodeling, cell growth, and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation and are localized to most vascular cell types115. Female sex hormone fluctuations lead to cyclic changes in MMPs that help to regulate tissue remodeling116. Additionally, sex differences noted in many MMPs and other CVD biomarkers find that large differences between men and premenopausal women are minimized after menopause117. In aging rodents, E2 administration decreases vascular wall thickness and distensibility and is associated with increased MMP-2 activity118. The role of nuclear ER in these effects are not clear, as activation of either ERα or ERβ with selective agonists counteract vascular collagen deposition due to aldosterone infusion119. More recent studies suggest that nuclear E2 signaling via ERα may be detrimental to vascular remodeling while activation of GPER is protective120.

Another less understood mechanism associated with vascular remodeling is cellular senescence during natural aging. Telomere shortening occurs with each successive division until cells reach replicative senescence. This process occurs earlier in men despite similar length telomeres when age matched and prevents cellular repair, which may account for some sex differences seen in vascular aging although the reason behind this difference is yet to be uncovered121. Vascular aging is also associated with calcification and stiffening of blood vessel walls. Studies consistently show that aging and menopause both increase arterial stiffness, but the impact of menopausal hormone therapy is mixed122–124. Therefore, factors such as timing and age may impact the ability of estrogen to reverse vascular remodeling during aging.

Using a rodent model, our group finds lower pulse wave velocity (PWV; a measure of arterial stiffness) in females, but this protection is lost during hypertension and aging70,125. Moreover, global deletion of GPER increases PWV in young, healthy female mice125. Interestingly, others show a detrimental role for ERα in arterial stiffness, as endothelial cell-specific deletion of this receptor is protective in both male and female mice fed a western diet126,127. The mineralocorticoid system most likely contributes to sex differences, as aging-induced arterial stiffening occurs earlier in male versus female mice but is blunted by deletion of the mineralocorticoid receptor from smooth muscle cells128. Moreover, patients with primary aldosteronism have increased carotid intima-media thickness and endothelial dysfunction in comparison with hypertensive patients129. Further information is still needed to identify the mechanisms that contribute to arterial stiffening and the impact of hormone therapies.

3.4. Obesity

Obesity is a major risk factor for hypertension and other CVD130. Currently, 42% of adults in the United States are obese, with both higher rates and more severe obesity in women than men131. Even though females are protected from CVD before menopause, obese premenopausal women lose this protection and have a higher risk for CVD than men, suggesting that obesity may dampen or negate the cardioprotection provided by E2 during the reproductive years130. Conversely, loss of E2 during the menopausal transition also promotes obesity, through changes in fat distribution, body composition, and food intake contribute to weight gain132. Data from animal models support a direct role for estrogen receptors in metabolism, feeding behavior, adiposity, and physical activity133,134. Women have higher levels of leptin than men even after controlling for body weight, which stimulates aldosterone release from the adrenal gland and promotes endothelial dysfunction135,136. Data thus far does not support a role for E2 in regulation of circulating levels of leptin137,138. However, aldosterone levels in response to an Ang II challenge are significantly lower in E2-treated versus OVX rats139. Interestingly, obese middle-aged women have higher plasma aldosterone levels than obese men, and aldosterone blockade is more effective for CVD in women. These studies indicate that the aldosterone-mineralocorticoid receptor pathway may impact the negative effect of obesity on CVD risk in females.

3.5. Immunity

While women are protected from CVD due to E2, they have an increased risk of autoimmune diseases140. Many autoimmune diseases fluctuate in degree of severity during a woman’s lifetime based upon variations in hormone levels141. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), both of which are more common in women, worsen during pregnancy while estrogen levels are high142. High levels of E2 have an inhibitory effect on the immune system143,144 which is likely regulated by estrogen receptors expressed at high levels on activated T cells and other immune cells145. In healthy women, circulating CD4+ T cells produce more of the anti-inflammatory phenotype marker, IFNγ, while in men more IL-17, a pro-inflammatory marker, is produced146. Interestingly, SLE is characterized by increased Th17 cells147 and SLE and RA are both associated with increased hypertension risk148. Therefore, increased expression of inflammatory cytokines most likely play a crucial role in hypertension risk. The protective effect of female sex on hypertension is maintained in premenopausal but not postmenopausal Rag1−/− mice, which lack T and B cells149,150. Moreover, the increased hypertension in postmenopausal Rag1−/− mice is dependent on the presence of CD3+ T cells. These data identify an important role for T cells as well as other immune cells in the protective effects of estrogen in hypertension.

3.6. Gut microbiota

Evolving research shows that gut microbiota may play a larger role in CVD than previously understood. Several metabolites produced in the gut are associated with adverse phenotypes, including specific oral and gut bacterial phylotypes such as Chrysemonas which are found in atherosclerotic plaques151,152. A direct connection between the gut microbiome and hypertension is shown by the development of high SBP, DBP and MAP in mice after fecal transplants from hypertensive human donors153. It has yet to be determined if obesity drives gut microbiota dysfunction or vice versa. Some human studies indicate that higher caloric intake is associated with decreased variability of healthy gut bacteria and can be rescued by weight loss154,155.

E2 and its receptors play a significant role in the gastrointestinal tract156. A study of 35 postmenopausal women showed that hormone therapy increases duodenal microbial biodiversity, lowers fasting glucose, and decreases bacteria associated with cardiovascular risk157. Estrogen deficiency also changes the gut microbiota to promote abnormal lipid metabolism and nonalcoholic fatty liver, a disease that is more prevalent in postmenopausal women and associated with clinical CVD158,159. Thus, it is essential to consider gut microbial composition when considering the impact of E2 on CVD risk.

3.7. Salt-sensitive hypertension

The consumption of high dietary salt in modern society contributes to chronic kidney diseases, hypertension, and CVD. Some individuals experience a greater than 10% increase in BP, while others are resistant to the effects of salt160. Salt sensitivity is elevated in hypertensive subjects compared with normotensive postmenopausal women161. In salt-sensitive subjects, the kidneys retain most of the salt due to abnormal overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system and failure to adequately suppress the RAAS160. Sex differences exist in renal function, with females having greater ability to excrete salt due to distinct expressions of sodium transporters in different segments of the kidneys162. Estrogen loss improves salt sensitivity in female Dahl salt-sensitive rats, indicating that E2 protects against kidney damage and the development of hypertension163. E2 mediates pressure natriuresis by regulating the RAAS and the endothelin system in the kidneys164 and attenuates kidney injury in hypertensive mRen2 rats fed a high salt diet10,83,84. Of note, salt sensitivity is a complex disease associated with a strong genetic predisposition, which is crucial for the development of hypertension160. Whether the protection against kidney damage mediated by E2 in high salt conditions is lost after menopause has not been fully understood, and in fact some animal studies show unexpected results in female models of aging and OVX165. Therefore, further investigation is necessary to address the essential health outcomes of a high salt diet in the renal system and the impact of sex hormones.

3.8. Circadian rhythms

Blood pressure follows a circadian pattern that repeats every 24 hours in healthy individuals, with a BP reduction of 10–20% from day to night. Healthy individuals with this normal decline in nocturnal BP are known as dippers, while those with a blunted fall in nighttime BP (<10%) are considered non-dippers166. A blunted or absent nocturnal fall in BP increases the risk for vascular complications, kidney damage, cerebrovascular events, and cardiovascular mortality167. Impaired autonomic dysfunction may promote non-dipping BP in addition to its negative effect on natriuresis166,168,169. RAAS components including renin and ACE follow circadian rhythms and may also contribute to disturbances in circadian BP170. The presence of diseases such as diabetes, metabolic disorders, salt sensitivity, chronic kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and heart failure are all associated with disrupted circadian rhythms and a non-dipping BP phenotype.

Emerging evidence reveals that elevated nighttime BP is a greater predictor of cardiovascular events in middle-aged women versus men171,172. In a meta-analysis of 9357 patients from 11 population, women have a greater risk for stroke, cardiac, and coronary complications with disturbances in 24-hour and nocturnal SBP in comparison with men171. Furthermore, non-dipping BP is associated with higher left ventricular mass in hypertensive women but not men173. These findings provide evidence of sex-specific risk factors in aging women, especially as cardiovascular risk increases after menopause. In a cross-sectional study, postmenopausal hypertensive women have a higher incidence of non-dipping BP174, and a randomized double-blind study of 12 postmenopausal non-dippers found that transdermal E2 restored the expected nocturnal SBP and DBP pattern175,176. However, more studies are needed to investigate the impact of estrogen replacement on non-dipping BP in postmenopausal women.

3.9. Estrogen paradox

Despite the large quantity of evidence supporting the benefits of estrogen, it is essential to recognize that not all health conditions are positively affected by this sex hormone. A prime example is pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), a disease targeting the pulmonary circulation and right heart function that carries a devastating 3-year survival rate of <60%177,178. While women are diagnosed at a 4:1 rate compared with men, female sex is linked to greater survival rates and right ventricular (RV) function178,179. Loss of E2 via OVX in animal models or menopause in women is sometimes shown to exacerbate the disease, contradicting the sexual dimorphism favoring men and called the “estrogen paradox”180. Data from animal models indicate this protection by E2 may be associated with a reduction in endothelin-1 and enhanced angiogenesis in the lung and heart181,182. On the other hand, some clinical studies show a higher rates of menopausal hormone user in pulmonary hypertension patients, and estrogen inhibition prevented and improved disease in mice, suggesting that estrogen may not be protective in all cases183,184. In conclusion, it is mechanistically unclear why prevalence rates are higher in females and why E2 sometimes exerts protective or detrimental effects. More research on these paradoxical finding may reveal new therapeutic targets.

4. Clinical Perspectives

4.1. Sociocultural factors

Biological differences in males and females are not the only causes of the disparity rates of hypertension and CVD among Americans. The social construction of men and women are determinant factors of lifestyle and health outcomes185. Gender factors such as education, marriage status, low socioeconomic status, social environment, experience of racial discrimination, traumatic stress, exposure to hazardous, inadequate medical care, and cultural factors are strongly associated with hypertension and ischemic heart diseases186,187. Gender differences exist in hypertension awareness, and women are more prone to visit primary care services and have their blood pressure levels taken than men187,188. Even though women are more aware of high BP and appear to respond better to anti-hypertensive drugs189,190, women in developing countries are more often self-medicated because of several tasks and limited time to take care of their health191. There is a continuous association between low education/economic status and hypertension prevalence in both genders living in rural zones and small center urban, thus intensifying the CVD in these areas191. A similar trend was also observed in different cohorts of developing countries192,193. Despite growing evidence showing the importance of gender disparities in health and illness, the complex interactions of sex and gender are not taken into account in clinical trials and management of hypertension treatment.

4.2. Diversity in clinical trials

The effect of E2 on vascular remodeling and hypertension has been widely studied in male models. Because of hormonal oscillations and pregnancy, women were excluded from most clinical research before 1993194,195. A male model for diagnosis, guidelines, and regimen treatment were simplified and followed for all patients with heart disease191,196. Until recently, cohorts with females have been advanced and included in clinical research but are still scarce in many cardiovascular studies.

In addition to sex differences, hypertension in the United States is characterized by significant racial disparities. Blacks are more likely to develop hypertension, coronary artery disease, and chronic kidney disease in comparison with White, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic counterparts1. Various factors such as body mass index, social/environmental factors, doctor-patient trust and communication, and lack of access to treatment all contribute to CVD management and control197. In addition, Black and Hispanic women have a higher likelihood of comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, or obesity during acute cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction1. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies may be inconclusive with regards to whether menopause is associated with hypertension due to heterogeneity in the studied populations7,198. Although sex, racial, and ethnic disparities have been documented for many years, prospective and longitudinal studies addressing underlying mechanisms triggering menopause-associated CVD risk in non-white populations are unfortunately limited. Recently, data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation revealed distinct trajectories of BP rise as well as patterns of estradiol decline and FSH rise among different races during the menopausal transition7. These results highlight the complexity of menopausal transition among women from different backgrounds. The inclusion of different racial and ethnic groups will provide a novel understanding of health disparities and new therapeutic options to improve the management of CVD risk in all women.

5. Conclusions

Animal studies show a favorable effect of E2 on protection against hypertension, coronary diseases, stroke, and heart failure. However, there are gaps in knowledge about the exact influence of each estrogen receptor in this protection. Indeed, the combination of age, sex hormones, genetic background, and unhealthy lifestyles all contribute to the onset of hypertension and CVD risk in postmenopausal women. Even though premenopausal women are protected, a wide array of evidence suggests that females may be more susceptible to the effects of lifestyle behaviors on changes in BP, particularly during the menopausal transition. Since females are still underrepresented in clinical trials and experimental studies, the mechanisms underlying the increased vulnerability of women to harmful effects remain elusive. Clinical studies should be inclusive and heterogeneous and designed to address outcomes by sex. The future of medicine is highly personalized, and clinicians must consider the various contributors to sex hormones and how they play a role in disease management and therapeutic strategies to preserve cardiovascular health.

Sources of Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL133619 and AG071746 to SHL; HL155841 to BOO), the American Heart Association (829713 to BV; 827812 to IKD), and the Tulane Center of Excellence in Sex-Based Biology & Medicine.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022; 145(8): e153–e639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tepper PG, Randolph JF Jr., McConnell DS, Crawford SL, El Khoudary SR, Joffe H et al. Trajectory clustering of estradiol and follicle-stimulating hormone during the menopausal transition among women in the Study of Women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(8): 2872–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y, Ding J, Bush TL, Longenecker JC, Nieto FJ, Golden SH et al. Relative androgen excess and increased cardiovascular risk after menopause: a hypothesized relation. Am J Epidemiol 2001; 154(6): 489–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rannevik G, Jeppsson S, Johnell O, Bjerre B, Laurell-Borulf Y, Svanberg L. A longitudinal study of the perimenopausal transition: altered profiles of steroid and pituitary hormones, SHBG and bone mineral density. Maturitas 1995; 21(2): 103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang N, Shao H, Chen Y, Xia F, Chi C, Li Q et al. Follicle-Stimulating Hormone, Its Association with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors, and 10-Year Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Postmenopausal Women. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson EA, El Khoudary SR, Crawford SL, Matthews K, Joffe H, Chae C et al. Hot Flash Frequency and Blood Pressure: Data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016; 25(12): 1204–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samargandy S, Matthews KA, Brooks MM, Barinas-Mitchell E, Magnani JW, Thurston RC et al. Trajectories of Blood Pressure in Midlife Women: Does Menopause Matter? Circ Res 2022; 130(3): 312–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Jama 2002; 288(3): 321–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, Wu L, Barad D, Barnabei VM et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. Jama 2007; 297(13): 1465–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chappell MC, Yamaleyeva LM, Westwood BM. Estrogen and salt sensitivity in the female mRen(2). Lewis rat. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology 2006; 291(5): R1557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Z, Wang H, Jessup JA, Lindsey SH, Chappell MC, Groban L. Role of estrogen in diastolic dysfunction. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2014; 306(5): H628–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oparil S, Chen SJ, Chen YF, Durand JN, Allen L, Thompson JA. Estrogen attenuates the adventitial contribution to neointima formation in injured rat carotid arteries. Cardiovascular research 1999; 44(3): 608–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Li X, Zhang D. Impact of hysterectomy on cardiovascular disease and different subtypes: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2022; 305(5): 1255–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingelsson E, Lundholm C, Johansson AL, Altman D. Hysterectomy and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J 2011; 32(6): 745–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howard BV, Kuller L, Langer R, Manson JE, Allen C, Assaf A et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease by hysterectomy status, with and without oophorectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Circulation 2005; 111(12): 1462–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson E, Santen RJ. Celebrating 75 years of oestradiol. Journal of molecular endocrinology 2015; 55(3): T1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen EV, Desombre ER, Kawashima T, Suzuki T, Kyser K, Jungblut PW. Estrogen-binding substances of target tissues. Science 1967; 158(3800): 529–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green S, Walter P, Kumar V, Krust A, Bornert JM, Argos P et al. Human oestrogen receptor cDNA: sequence, expression and homology to v-erb-A. Nature 1986; 320(6058): 134–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein-Hitpass L, Schorpp M, Wagner U, Ryffel GU. An estrogen-responsive element derived from the 5’ flanking region of the Xenopus vitellogenin A2 gene functions in transfected human cells. Cell 1986; 46(7): 1053–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tee MK, Rogatsky I, Tzagarakis-Foster C, Cvoro A, An J, Christy RJ et al. Estradiol and selective estrogen receptor modulators differentially regulate target genes with estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Mol Biol Cell 2004; 15(3): 1262–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurrala R, Kilanowski-Doroh IM, Hutson DD, Ogola BO, Zimmerman MA, Katakam PVG et al. Alterations in the estrogen receptor profile of cardiovascular tissues during aging. GeroScience 2021; 43(1): 433–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutson DD, Gurrala R, Ogola BO, Zimmerman MA, Mostany R, Satou R et al. Estrogen receptor profiles across tissues from male and female Rattus norvegicus. Biol Sex Differ 2019; 10(1): 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pugach EK, Blenck CL, Dragavon JM, Langer SJ, Leinwand LA. Estrogen receptor profiling and activity in cardiac myocytes. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 2016; 431: 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ropero AB, Eghbali M, Minosyan TY, Tang G, Toro L, Stefani E. Heart estrogen receptor alpha: distinct membrane and nuclear distribution patterns and regulation by estrogen. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2006; 41(3): 496–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haynes MP, Sinha D, Russell KS, Collinge M, Fulton D, Morales-Ruiz M et al. Membrane estrogen receptor engagement activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase via the PI3-kinase-Akt pathway in human endothelial cells. Circ Res 2000; 87(8): 677–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science 2005; 307(5715): 1625–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung TH, Wang SM, Liang JY, Yang SH, Wu JC. The interaction of estrogen receptor alpha and caveolin-3 regulates connexin43 phosphorylation in metabolic inhibition-treated rat cardiomyocytes. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2009; 41(11): 2323–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chambliss KL, Yuhanna IS, Mineo C, Liu P, German Z, Sherman TS et al. Estrogen receptor alpha and endothelial nitric oxide synthase are organized into a functional signaling module in caveolae. Circ Res 2000; 87(11): E44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Couse JF, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocrine reviews 1999; 20(3): 358–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendelsohn ME. Genomic and nongenomic effects of estrogen in the vasculature. The American journal of cardiology 2002; 90(1A): 3F–6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodges YK, Tung L, Yan XD, Graham JD, Horwitz KB, Horwitz LD. Estrogen receptors alpha and beta: prevalence of estrogen receptor beta mRNA in human vascular smooth muscle and transcriptional effects. Circulation 2000; 101(15): 1792–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Somani YB, Pawelczyk JA, De Souza MJ, Kris-Etherton PM, Proctor DN. Aging women and their endothelium: probing the relative role of estrogen on vasodilator function. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2019; 317(2): H395–H404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khalil RA. Estrogen, vascular estrogen receptor and hormone therapy in postmenopausal vascular disease. Biochem Pharmacol 2013; 86(12): 1627–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy E. Estrogen signaling and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 2011; 109(6): 687–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guivarc’h E, Favre J, Guihot AL, Vessieres E, Grimaud L, Proux C et al. Nuclear Activation Function 2 Estrogen Receptor alpha Attenuates Arterial and Renal Alterations Due to Aging and Hypertension in Female Mice. J Am Heart Assoc 2020; 9(5): e013895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinna C, Cignarella A, Sanvito P, Pelosi V, Bolego C. Prolonged ovarian hormone deprivation impairs the protective vascular actions of estrogen receptor alpha agonists. Hypertension 2008; 51(4): 1210–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Connelly PJ, Casey H, Montezano AC, Touyz RM, Delles C. Sex steroids receptors, hypertension, and vascular ageing. Journal of human hypertension 2022; 36(2): 120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Widder J, Pelzer T, von Poser-Klein C, Hu K, Jazbutyte V, Fritzemeier KH et al. Improvement of endothelial dysfunction by selective estrogen receptor-alpha stimulation in ovariectomized SHR. Hypertension 2003; 42(5): 991–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xue B, Pamidimukkala J, Lubahn DB, Hay M. Estrogen receptor-alpha mediates estrogen protection from angiotensin II-induced hypertension in conscious female mice. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2007; 292(4): H1770–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Irsik DL, Carmines PK, Lane PH. Classical estrogen receptors and ERalpha splice variants in the mouse. PloS one 2013; 8(8): e70926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aryan L, Younessi D, Zargari M, Banerjee S, Agopian J, Rahman S et al. The Role of Estrogen Receptors in Cardiovascular Disease. International journal of molecular sciences 2020; 21(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arao Y, Gruzdev A, Scott GJ, Ray MK, Donoghue LJ, Neufeld TI et al. A Novel Mouse Model to Analyze Non-Genomic ERα Physiological Actions. Journal of the Endocrine Society 2022; 6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jankowska EA, Biel B, Majda J, Szklarska A, Lopuszanska M, Medras M et al. Anabolic deficiency in men with chronic heart failure: prevalence and detrimental impact on survival. Circulation 2006; 114(17): 1829–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jankowska EA, Rozentryt P, Ponikowska B, Hartmann O, Kustrzycka-Kratochwil D, Reczuch K et al. Circulating estradiol and mortality in men with systolic chronic heart failure. JAMA 2009; 301(18): 1892–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeap BB, Hyde Z, Almeida OP, Norman PE, Chubb SA, Jamrozik K et al. Lower testosterone levels predict incident stroke and transient ischemic attack in older men. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2009; 94(7): 2353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ellis JA, Infantino T, Harrap SB. Sex-dependent association of blood pressure with oestrogen receptor genes ERalpha and ERbeta. Journal of hypertension 2004; 22(6): 1127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim-Schulze S, McGowan KA, Hubchak SC, Cid MC, Martin MB, Kleinman HK et al. Expression of an estrogen receptor by human coronary artery and umbilical vein endothelial cells. Circulation 1996; 94(6): 1402–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dai-Do D, Espinosa E, Liu G, Rabelink TJ, Julmy F, Yang Z et al. 17 beta-estradiol inhibits proliferation and migration of human vascular smooth muscle cells: similar effects in cells from postmenopausal females and in males. Cardiovasc Res 1996; 32(5): 980–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawano H, Motoyama T, Kugiyama K, Hirashima O, Ohgushi M, Fujii H et al. Gender difference in improvement of endothelium-dependent vasodilation after estrogen supplementation. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30(4): 914–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.New G, Timmins KL, Duffy SJ, Tran BT, O’Brien RC, Harper RW et al. Long-term estrogen therapy improves vascular function in male to female transsexuals. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 29(7): 1437–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Komesaroff PA, Fullerton M, Esler MD, Dart A, Jennings G, Sudhir K. Low-dose estrogen supplementation improves vascular function in hypogonadal men. Hypertension 2001; 38(5): 1011–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cavasin MA, Sankey SS, Yu AL, Menon S, Yang XP. Estrogen and testosterone have opposing effects on chronic cardiac remodeling and function in mice with myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003; 284(5): H1560–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Favre J, Vessieres E, Guihot AL, Grimaud L, Proux C, Loufrani L et al. Early Inactivation of Membrane Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERalpha) Recapitulates the Endothelial Dysfunction of Aged Mouse Resistance Arteries. International journal of molecular sciences 2022; 23(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin J, Steenbergen C, Murphy E, Sun J. Estrogen receptor-beta activation results in S-nitrosylation of proteins involved in cardioprotection. Circulation 2009; 120(3): 245–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gabel SA, Walker VR, London RE, Steenbergen C, Korach KS, Murphy E. Estrogen receptor beta mediates gender differences in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 2005; 38(2): 289–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Makela S, Savolainen H, Aavik E, Myllarniemi M, Strauss L, Taskinen E et al. Differentiation between vasculoprotective and uterotrophic effects of ligands with different binding affinities to estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1999; 96(12): 7077–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Milner TA, Contoreggi NH, Yu F, Johnson MA, Wang G, Woods C et al. Estrogen Receptor beta Contributes to Both Hypertension and Hypothalamic Plasticity in a Mouse Model of Peri-Menopause. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2021; 41(24): 5190–5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xue B, Zhang Z, Beltz TG, Johnson RF, Guo F, Hay M et al. Estrogen receptor-beta in the paraventricular nucleus and rostroventrolateral medulla plays an essential protective role in aldosterone/salt-induced hypertension in female rats. Hypertension 2013; 61(6): 1255–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lehrer S, Rabin J, Kalir T, Schachter BS. Estrogen receptor variant and hypertension in women. Hypertension 1993; 21(4): 439–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ogawa S, Emi M, Shiraki M, Hosoi T, Ouchi Y, Inoue S. Association of estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) gene polymorphism with blood pressure. J Hum Genet 2000; 45(6): 327–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manosroi W, Tan JW, Rariy CM, Sun B, Goodarzi MO, Saxena AR et al. The Association of Estrogen Receptor-beta Gene Variation With Salt-Sensitive Blood Pressure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017; 102(11): 4124–4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J. Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 2005; 146(2): 624–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindsey SH, Liu L, Chappell MC. Vasodilation by GPER in mesenteric arteries involves both endothelial nitric oxide and smooth muscle cAMP signaling. Steroids 2014; 81: 99–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ogola BO, Zimmerman MA, Sure VN, Gentry KM, Duong JL, Clark GL et al. G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor Protects From Angiotensin II-Induced Increases in Pulse Pressure and Oxidative Stress. Frontiers in endocrinology 2019; 10: 586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haas E, Bhattacharya I, Brailoiu E, Damjanovic M, Brailoiu GC, Gao X et al. Regulatory role of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor for vascular function and obesity. Circ Res 2009; 104(3): 288–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ogola B, Zhang Y, Iyer L, Thekkumkara T. 2-Methoxyestradiol causes matrix metalloproteinase 9-mediated transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor and angiotensin type 1 receptor downregulation in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 2018; 314(5): C554–C568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lindsey SH, Cohen JA, Brosnihan KB, Gallagher PE, Chappell MC. Chronic treatment with the G protein-coupled receptor 30 agonist G-1 decreases blood pressure in ovariectomized mRen2.Lewis rats. Endocrinology 2009; 150(8): 3753–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alencar AK, Montes GC, Montagnoli T, Silva AM, Martinez ST, Fraga AG et al. Activation of GPER ameliorates experimental pulmonary hypertension in male rats. Eur J Pharm Sci 2017; 97: 208–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dinh QN, Vinh A, Kim HA, Saini N, Broughton BRS, Chrissobolis S et al. Aldosterone-induced hypertension is sex-dependent, mediated by T cells and sensitive to GPER activation. Cardiovascular research 2021; 117(3): 960–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ogola BO, Clark GL, Abshire CM, Harris NR, Gentry KL, Gunda SS et al. Sex and the G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor Impact Vascular Stiffness. Hypertension 2021; 78(1): e1–e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Broughton BR, Brait VH, Kim HA, Lee S, Chu HX, Gardiner-Mann CV et al. Sex-dependent effects of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor activity on outcome after ischemic stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation 2014; 45(3): 835–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meyer MR, Fredette NC, Daniel C, Sharma G, Amann K, Arterburn JB et al. Obligatory role for GPER in cardiovascular aging and disease. Science signaling 2016; 9(452): ra105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bian C, Bai B, Gao Q, Li S, Zhao Y. 17beta-Estradiol Regulates Glucose Metabolism and Insulin Secretion in Rat Islet beta Cells Through GPER and Akt/mTOR/GLUT2 Pathway. Frontiers in endocrinology 2019; 10: 531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharma G, Hu C, Staquicini DI, Brigman JL, Liu M, Mauvais-Jarvis F et al. Preclinical efficacy of the GPER-selective agonist G-1 in mouse models of obesity and diabetes. Sci Transl Med 2020; 12(528). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lindsey SH, da Silva AS, Silva MS, Chappell MC. Reduced vasorelaxation to estradiol and G-1 in aged female and adult male rats is associated with GPR30 downregulation. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism 2013; 305(1): E113–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yu X, Nguyen P, Burns NC, Heaps CL, Stallone JN, Sohrabji F et al. Activation of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor fine-tunes age-related decreased vascular activities in the aortae of female and male rats. Steroids 2022; 183: 108997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Feldman RD, Gros R, Ding Q, Hussain Y, Ban MR, McIntyre AD et al. A common hypofunctional genetic variant of GPER is associated with increased blood pressure in women. British journal of clinical pharmacology 2014; 78(6): 1441–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jessup JA, Lindsey SH, Wang H, Chappell MC, Groban L. Attenuation of salt-induced cardiac remodeling and diastolic dysfunction by the GPER agonist G-1 in female mRen2.Lewis rats. PloS one 2010; 5(11): e15433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang H, Jessup JA, Lin MS, Chagas C, Lindsey SH, Groban L. Activation of GPR30 attenuates diastolic dysfunction and left ventricle remodelling in oophorectomized mRen2.Lewis rats. Cardiovascular research 2012; 94(1): 96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang H, Sun X, Chou J, Lin M, Ferrario CM, Zapata-Sudo G et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) leads to left ventricular dysfunction and adverse remodeling: A sex-specific gene profiling analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017; 1863(8): 1870–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang H, Sun X, Chou J, Lin M, Ferrario CM, Zapata-Sudo G et al. Inflammatory and mitochondrial gene expression data in GPER-deficient cardiomyocytes from male and female mice. Data in brief 2017; 10: 465–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang H, Sun X, Lin MS, Ferrario CM, Van Remmen H, Groban L. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) deficiency induces cardiac remodeling through oxidative stress. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine 2018; 199: 39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lindsey SH, Yamaleyeva LM, Brosnihan KB, Gallagher PE, Chappell MC. Estrogen receptor GPR30 reduces oxidative stress and proteinuria in the salt-sensitive female mRen2.Lewis rat. Hypertension 2011; 58(4): 665–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gohar EY, Almutlaq RN, Daugherty EM, Butt MK, Jin C, Pollock JS et al. Activation of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 ameliorates proximal tubular injury and proteinuria in Dahl salt-sensitive female rats. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology 2021; 320(3): R297–R306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Delgado NTB, Rouver WDN, Freitas-Lima LC, Vieira-Alves I, Lemos VS, Dos Santos RL. Sex Differences in the Vasodilation Mediated by G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor (GPER) in Hypertensive Rats. Front Physiol 2021; 12: 659291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Collins P, Rosano GM, Sarrel PM, Ulrich L, Adamopoulos S, Beale CM et al. 17 beta-Estradiol attenuates acetylcholine-induced coronary arterial constriction in women but not men with coronary heart disease. Circulation 1995; 92(1): 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Blumenthal RS, Heldman AW, Brinker JA, Resar JR, Coombs VJ, Gloth ST et al. Acute effects of conjugated estrogens on coronary blood flow response to acetylcholine in men. The American journal of cardiology 1997; 80(8): 1021–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reis SE, Holubkov R, Zell KA, Smith AJ, Cohen HA, Feldman MD et al. Estrogen acutely abolishes abnormal cold-induced coronary constriction in men. Chest 1998; 114(6): 1556–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reis SE, Bhoopalam V, Zell KA, Counihan PJ, Smith AJ, Pham S et al. Conjugated estrogens acutely abolish abnormal cold-induced coronary vasoconstriction in male cardiac allografts. Circulation 1998; 97(1): 23–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chappell MC. Biochemical evaluation of the renin-angiotensin system: the good, bad, and absolute? American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2016; 310(2): H137–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Medina D, Mehay D, Arnold AC. Sex differences in cardiovascular actions of the renin-angiotensin system. Clin Auton Res 2020; 30(5): 393–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoo JK, Fu Q. Impact of sex and age on metabolism, sympathetic activity, and hypertension. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2020; 34(9): 11337–11346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Silva-Antonialli MM, Tostes RC, Fernandes L, Fior-Chadi DR, Akamine EH, Carvalho MH et al. A lower ratio of AT1/AT2 receptors of angiotensin II is found in female than in male spontaneously hypertensive rats. Cardiovascular research 2004; 62(3): 587–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pendergrass KD, Pirro NT, Westwood BM, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB, Chappell MC. Sex differences in circulating and renal angiotensins of hypertensive mRen(2). Lewis but not normotensive Lewis rats. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2008; 295(1): H10–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chappell MC, Gallagher PE, Averill DB, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB. Estrogen or the AT1 antagonist olmesartan reverses the development of profound hypertension in the congenic mRen2. Lewis rat. Hypertension 2003; 42(4): 781–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhao YY, Zhou J, Narayanan CS, Cui Y, Kumar A. Role of C/A polymorphism at −20 on the expression of human angiotensinogen gene. Hypertension 1999; 33(1): 108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brosnihan KB, Hodgin JB, Smithies O, Maeda N, Gallagher P. Tissue-specific regulation of ACE/ACE2 and AT1/AT2 receptor gene expression by oestrogen in apolipoprotein E/oestrogen receptor-alpha knock-out mice. Experimental physiology 2008; 93(5): 658–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang H, Jessup JA, Zhao Z, Da Silva J, Lin M, MacNamara LM et al. Characterization of the cardiac renin angiotensin system in oophorectomized and estrogen-replete mRen2.Lewis rats. PloS one 2013; 8(10): e76992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schunkert H, Danser AH, Hense HW, Derkx FH, Kurzinger S, Riegger GA. Effects of estrogen replacement therapy on the renin-angiotensin system in postmenopausal women. Circulation 1997; 95(1): 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Proudler AJ, Ahmed AI, Crook D, Fogelman I, Rymer JM, Stevenson JC. Hormone replacement therapy and serum angiotensin-converting-enzyme activity in postmenopausal women. Lancet 1995; 346(8967): 89–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mauvais-Jarvis F, Berthold HK, Campesi I, Carrero JJ, Dakal S, Franconi F et al. Sex- and Gender-Based Pharmacological Response to Drugs. Pharmacological reviews 2021; 73(2): 730–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wing LM, Reid CM, Ryan P, Beilin LJ, Brown MA, Jennings GL et al. A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin-converting--enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly. The New England journal of medicine 2003; 348(7): 583–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sung BH, Ching M, Izzo JL Jr., Dandona P, Wilson MF. Estrogen improves abnormal norepinephrine-induced vasoconstriction in postmenopausal women. Journal of hypertension 1999; 17(4): 523–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sudhir K, Elser MD, Jennings GL, Komesaroff PA. Estrogen supplementation decreases norepinephrine-induced vasoconstriction and total body norepinephrine spillover in perimenopausal women. Hypertension 1997; 30(6): 1538–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li Z, Duckles SP. Influence of gender on vascular reactivity in the rat. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 1994; 268(3): 1426–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.El-Mas MM, El-Gowilly SM, Gohar EY, Ghazal AR. Sex and hormonal influences on the nicotine-induced attenuation of isoprenaline vasodilations in the perfused rat kidney. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology 2009; 87(7): 539–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Riedel K, Deussen AJ, Tolkmitt J, Weber S, Schlinkert P, Zatschler B et al. Estrogen determines sex differences in adrenergic vessel tone by regulation of endothelial beta-adrenoceptor expression. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2019; 317(2): H243–H254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hajagos-Toth J, Bota J, Ducza E, Csanyi A, Tiszai Z, Borsodi A et al. The effects of estrogen on the alpha2-adrenergic receptor subtypes in rat uterine function in late pregnancy in vitro. Croat Med J 2016; 57(2): 100–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Freedman RR. Menopausal hot flashes: mechanisms, endocrinology, treatment. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 2014; 142: 115–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Usselman CW, Gimon TI, Nielson CA, Luchyshyn TA, Coverdale NS, Van Uum SH et al. Menstrual cycle and sex effects on sympathetic responses to acute chemoreflex stress. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2015; 308(6): H664–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Minson CT, Halliwill JR, Young TM, Joyner MJ. Influence of the menstrual cycle on sympathetic activity, baroreflex sensitivity, and vascular transduction in young women. Circulation 2000; 101(8): 862–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jacob DW, Voshage AM, Harper JL, Limberg JK. Effect of oral hormonal contraceptive pill use on the hemodynamic response to the cold pressor test. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 113.Mohamed MK, El-Mas MM, Abdel-Rahman AA. Estrogen enhancement of baroreflex sensitivity is centrally mediated. The American journal of physiology 1999; 276(4): R1030–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Huikuri HV, Pikkujamsa SM, Airaksinen KE, Ikaheimo MJ, Rantala AO, Kauma H et al. Sex-related differences in autonomic modulation of heart rate in middle-aged subjects. Circulation 1996; 94(2): 122–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang X, Khalil RA. Matrix Metalloproteinases, Vascular Remodeling, and Vascular Disease. Adv Pharmacol 2018; 81: 241–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Powell BS, Dhaher YY, Szleifer IG. Review of the Multiscale Effects of Female Sex Hormones on Matrix Metalloproteinase-Mediated Collagen Degradation. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 2015; 43(5–6): 401–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lau ES, Paniagua SM, Guseh JS, Bhambhani V, Zanni MV, Courchesne P et al. Sex Differences in Circulating Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 74(12): 1543–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhang Y, Stewart KG, Davidge ST. Estrogen replacement reduces age-associated remodeling in rat mesenteric arteries. Hypertension 2000; 36(6): 970–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Arias-Loza PA, Hu K, Dienesch C, Mehlich AM, Konig S, Jazbutyte V et al. Both estrogen receptor subtypes, alpha and beta, attenuate cardiovascular remodeling in aldosterone salt-treated rats. Hypertension 2007; 50(2): 432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gros R, Hussain Y, Chorazyczewski J, Pickering JG, Ding Q, Feldman RD. Extent of Vascular Remodeling Is Dependent on the Balance Between Estrogen Receptor α and G-Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor. Hypertension 2016; 68(5): 1225–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dela Justina V, Miguez JSG, Priviero F, Sullivan JC, Giachini FR, Webb RC. Sex Differences in Molecular Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Aging. Front Aging 2021; 2: 725884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Laakkonen EK, Karppinen JE, Lehti S, Lee E, Pesonen E, Juppi HK et al. Associations of Sex Hormones and Hormonal Status With Arterial Stiffness in a Female Sample From Reproductive Years to Menopause. Frontiers in endocrinology 2021; 12: 765916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Nagai Y, Earley CJ, Kemper MK, Bacal CS, Metter EJ. Influence of age and postmenopausal estrogen replacement therapy on carotid arterial stiffness in women. Cardiovascular research 1999; 41(1): 307–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Samargandy S, Matthews KA, Brooks MM, Barinas-Mitchell E, Magnani JW, Janssen I et al. Arterial Stiffness Accelerates Within 1 Year of the Final Menstrual Period: The SWAN Heart Study. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2020; 40(4): 1001–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ogola BO, Abshire CM, Visniauskas B, Kiley JX, Horton AC, Clark GL et al. Sex Differences in Vascular Aging and Impact of GPER Deletion. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 126.Manrique C, Lastra G, Ramirez-Perez FI, Haertling D, DeMarco VG, Aroor AR et al. Endothelial Estrogen Receptor-alpha Does Not Protect Against Vascular Stiffness Induced by Western Diet in Female Mice. Endocrinology 2016; 157(4): 1590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Manrique-Acevedo C, Ramirez-Perez FI, Padilla J, Vieira-Potter VJ, Aroor AR, Barron BJ et al. Absence of Endothelial ERalpha Results in Arterial Remodeling and Decreased Stiffness in Western Diet-Fed Male Mice. Endocrinology 2017; 158(6): 1875–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.DuPont JJ, Kim SK, Kenney RM, Jaffe IZ. Sex differences in the time course and mechanisms of vascular and cardiac aging in mice: role of the smooth muscle cell mineralocorticoid receptor. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2021; 320(1): H169–H180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Demirkiran A, Everaars H, Elitok A, van de Ven PM, Smulders YM, Dreijerink KM et al. Hypertension with primary aldosteronism is associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness and endothelial dysfunction. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2019; 21(7): 932–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Despres JP, Gordon-Larsen P, Lavie CJ et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021; 143(21): e984–e1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll MD, Chen T, Davy O, Fink S et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports 2021; 158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lovre D, Lindsey SH, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Effect of menopausal hormone therapy on components of the metabolic syndrome. Therapeutic advances in cardiovascular disease 2016; 11(1): 33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Law J, Bloor I, Budge H, Symonds ME. The influence of sex steroids on adipose tissue growth and function. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2014; 19(1): 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sharma G, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Prossnitz ER. Roles of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER in metabolic regulation. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 2018; 176: 31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hellstrom L, Wahrenberg H, Hruska K, Reynisdottir S, Arner P. Mechanisms behind gender differences in circulating leptin levels. J Intern Med 2000; 247(4): 457–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Huby AC, Otvos L Jr., Belin de Chantemele EJ. Leptin Induces Hypertension and Endothelial Dysfunction via Aldosterone-Dependent Mechanisms in Obese Female Mice. Hypertension 2016; 67(5): 1020–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Haffner SM, Mykkanen L, Stern MP. Leptin concentrations in women in the San Antonio Heart Study: effect of menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 146(7): 581–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Salbach B, Nawroth PP, Kubler W, von Holst T, Salbach PB. Serum leptin levels and body weight in postmenopausal women under transdermal hormone replacement therapy. Eur J Med Res 2000; 5(2): 63–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Roesch DM, Tian Y, Zheng W, Shi M, Verbalis JG, Sandberg K. Estradiol attenuates angiotensin-induced aldosterone secretion in ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology 2000; 141(12): 4629–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ngo ST, Steyn FJ, McCombe PA. Gender differences in autoimmune disease. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology 2014; 35(3): 347–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Desai MK, Brinton RD. Autoimmune Disease in Women: Endocrine Transition and Risk Across the Lifespan. Frontiers in endocrinology 2019; 10: 265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Castro-Gutierrez A, Young K, Bermas BL. Pregnancy and Management in Women with Rheumatoid Arthritis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, and Obstetric Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2022; 48(2): 523–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Cutolo M, Brizzolara R, Atzeni F, Capellino S, Straub RH, Puttini PC. The immunomodulatory effects of estrogens: clinical relevance in immune-mediated rheumatic diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010; 1193: 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Verthelyi D. Sex hormones as immunomodulators in health and disease. Int Immunopharmacol 2001; 1(6): 983–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Lewis PA, O’Sullivan MM, Rumfeld WR, Coles EC, Jessop JD. Significant changes in Ritchie scores. Br J Rheumatol 1988; 27(1): 32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zhang MA, Rego D, Moshkova M, Kebir H, Chruscinski A, Nguyen H et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)alpha and -gamma regulate IFNgamma and IL-17A production by human T cells in a sex-specific way. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012; 109(24): 9505–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Yang J, Chu Y, Yang X, Gao D, Zhu L, Yang X et al. Th17 and natural Treg cell population dynamics in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60(5): 1472–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Wolf VL, Ryan MJ. Autoimmune Disease-Associated Hypertension. Current hypertension reports 2019; 21(1): 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Pollow DP, Uhrlaub J, Romero-Aleshire M, Sandberg K, Nikolich-Zugich J, Brooks HL et al. Sex differences in T-lymphocyte tissue infiltration and development of angiotensin II hypertension. Hypertension 2014; 64(2): 384–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Pollow DP Jr., Uhlorn JA, Sylvester MA, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Uhrlaub JL, Lindsey ML et al. Menopause and FOXP3(+) Treg cell depletion eliminate female protection against T cell-mediated angiotensin II hypertension. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2019; 317(2): H415–H423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Witkowski M, Weeks TL, Hazen SL. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res 2020; 127(4): 553–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Koren O, Spor A, Felin J, Fak F, Stombaugh J, Tremaroli V et al. Human oral, gut, and plaque microbiota in patients with atherosclerosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2011; 108 Suppl 1: 4592–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, Chen J, Tao J, Tian G et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome 2017; 5(1): 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Jumpertz R, Le DS, Turnbaugh PJ, Trinidad C, Bogardus C, Gordon JI et al. Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 94(1): 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005; 102(31): 11070–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Chen C, Gong X, Yang X, Shang X, Du Q, Liao Q et al. The roles of estrogen and estrogen receptors in gastrointestinal disease. Oncol Lett 2019; 18(6): 5673–5680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Leite G, Barlow GM, Parodi G, Pimentel ML, Chang C, Hosseini A et al. Duodenal microbiome changes in postmenopausal women: effects of hormone therapy and implications for cardiovascular risk. Menopause 2022; 29(3): 264–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Liu L, Fu Q, Li T, Shao K, Zhu X, Cong Y et al. Gut microbiota and butyrate contribute to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in premenopause due to estrogen deficiency. PloS one 2022; 17(2): e0262855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Kasper P, Martin A, Lang S, Kutting F, Goeser T, Demir M et al. NAFLD and cardiovascular diseases: a clinical review. Clinical research in cardiology : official journal of the German Cardiac Society 2021; 110(7): 921–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Balafa O, Kalaitzidis RG. Salt sensitivity and hypertension. Journal of human hypertension 2021; 35(3): 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Colafella KMM, Denton KM. Sex-specific differences in hypertension and associated cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2018; 14(3): 185–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Veiras LC, Girardi ACC, Curry J, Pei L, Ralph DL, Tran A et al. Sexual Dimorphic Pattern of Renal Transporters and Electrolyte Homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28(12): 3504–3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Dahl LK, Knudsen KD, Ohanian EV, Muirhead M, Tuthill R. Role of the gonads in hypertension-prone rats. The Journal of experimental medicine 1975; 142(3): 748–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Kittikulsuth W, Sullivan JC, Pollock DM. ET-1 actions in the kidney: evidence for sex differences. Br J Pharmacol 2013; 168(2): 318–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Yamaleyeva LM, Pendergrass KD, Pirro NT, Gallagher PE, Groban L, Chappell MC. Ovariectomy is protective against renal injury in the high-salt-fed older mRen2. Lewis rat. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2007; 293(4): H2064–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Douma LG, Gumz ML. Circadian clock-mediated regulation of blood pressure. Free Radic Biol Med 2018; 119: 108–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]