Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV) is a single-stranded RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family that is primarily transmitted by mosquitoes. WNV is a leading cause of viral encephalitis in the United States with up to 1% of infected individuals developing neuroinvasive disease. A nondiagnostic rash, frequently described as morbilliform, develops in up to half of patients with WNV fever. Although mouse models and cultured primary human keratinocytes have implicated the skin as a site of viral replication,1 there has been no direct evidence for the presence of WNV proteins in the skin of patients. We report a case of neuroinvasive WNV in a 67-year-old male patient who presented with an unexpected vesicular rash in the skin. Immunohistochemistical (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF) studies revealed WNV proteins to be present in the patient’s affected skin lesions. This case expands the reported cutaneous manifestations of WNV infection. In addition, it raises the possibility that IF or IHC studies on skin biopsies could be used as an adjunct test patients suspected to have WNV infection, especially when serologic tests are delayed or unavailable. Finally, we review the diagnosis and clinical features of WNV and other neuroinvasive flaviviruses.

Case report

In the late fall, a 67-year-old man presented with 4 days of fever, malaise, and headache. He had no known immunosuppression and his past medical history was notable only for the successful surgical excision of prostate cancer and melanoma in situ. His only medication before admission was solifenacin for hyperactive bladder. He had traveled to California and South Carolina 1 week before presentation. No animal or arthropod exposures were reported, although the patient took daily walks in the woods near his home in north Texas. Upon admission, he was febrile to 39.5 °C, tachycardic to 102 beats/min, but was not hypotensive. The remainder of his physical examination, including neurologic, was unremarkable at presentation.

Initial blood count and metabolic panel were notable only for mild anemia (red blood cell count, 3.47 (×106/microL); hemoglobin, 10.6 (g/dL); and hematocrit, 31.3%). Urine and blood cultures showed no growth, and nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), parainfluenza, adenovirus, Bordetella pertussis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, and enterovirus were negative. Serologic screens for HIV, Cryptococcus neoformans, Rickettsia typhi, Rickettsia rickettsii, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Treponema pallidum were negative. Chest X-ray, computed tomography imaging of the chest, abdomen, brain, and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain did not identify any acute processes or infection. Initial attempts at lumbar puncture were not successful and assistance from interventional radiology was requested. Given the concern for meningitis, the patient was started on empiric intravenous acyclovir, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, and vancomycin, with subsequent addition of oral doxycycline for coverage of rickettsial diseases. On day 3, tremulousness, hyperreflexia, and myoclonus developed in the patient. Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) obtained via interventional radiology–assisted lumbar puncture revealed lymphocytic pleocytosis with 40 nucleated cells/mm3, 14% neutrophils, 64% lymphocytes, and 20% monocytes. CSF total protein was elevated (50 [range, 15-45] mg/dL) and glucose was normal. CSF evaluation including bacterial culture, VDRL, herpes simplex virus-1/2, and enterovirus PCR and cryptococcal antigen testing were negative.

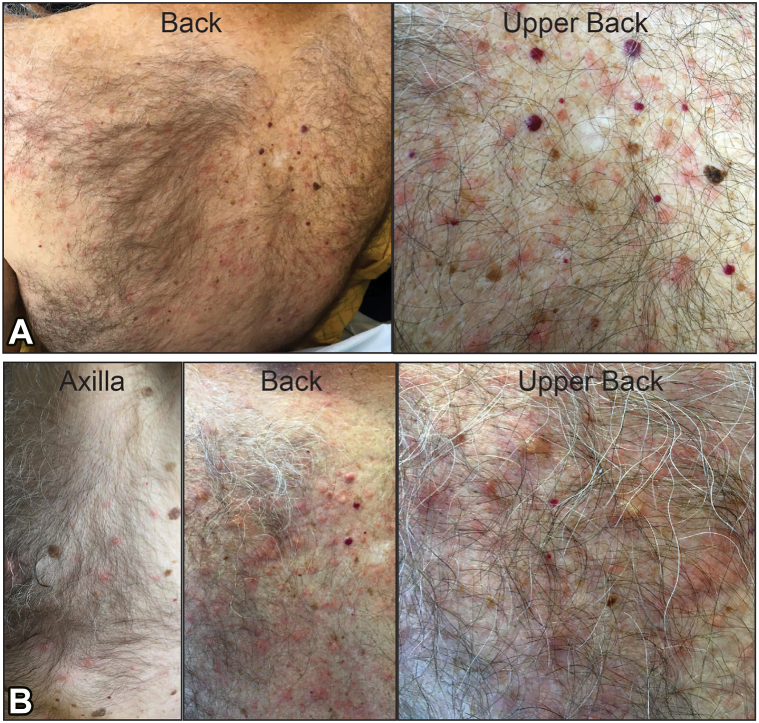

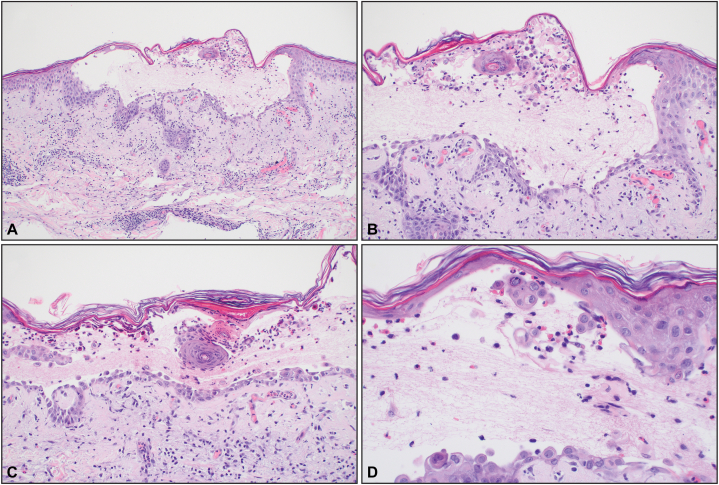

On day 4, an asymptomatic rash developed on the upper portion of the patient’s back. The rash began as pink macules and papules that evolved into vesicles on the back, chest, and abdomen (Fig 1). The patient did not report any itching or symptoms from the rash and no topical therapies were required despite its evolution to vesicles. Swabs of the vesicles were negative for HSV-1/2 and varicella-zoster virus by PCR. There were no signs of skin pain, mucosal involvement, or other features suggestive of a severe drug reaction. The vesicles were biopsied, and microscopy revealed an intraepidermal vesicle with focal dyskeratosis and a mixed infiltrate in the papillary dermis (Fig 2). Direct IF studies did not reveal in situ deposits of IgG, IgA, IgM, C3c, and fibrinogen in the skin, making an autoimmune-mediated blistering dermatosis less likely. On day 6, both serum (WNV) IgM and IgG (drawn on day 2), and CSF WNV IgM (drawn on day 3) resulted as positive, rendering a diagnosis of WNV infection. The patient received supportive care and was hospitalized for 7 days with marked clinical improvement by discharge. His rash had largely resolved and only small areas corresponding to the healing vesicles were still visible.

Fig 1.

Clinical presentation of (A) initial day 4 and (B) evolving day 6 skin lesions in patient diagnosed with West Nile virus encephalitis. Early lesions were pink macules and papules on the back and chest. Late lesions included erythematous papules and vesicles on the back, chest, and extremities.

Fig 2.

Biopsy revealed an acantholytic intraepidermal vesicle with focal dyskeratosis and a mixed infiltrate in the papillary dermis. (Original magnifications: A, ×100; B, ×200; C, ×200; D, ×400).

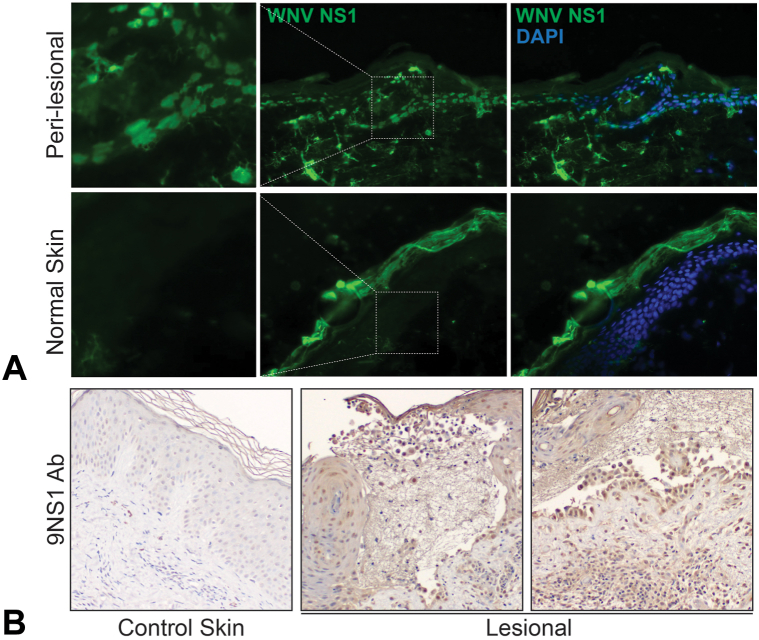

Studies on the skin biopsies revealed the presence of abundant WNV nonstructural glycoprotein (NS1) by IF and IHC (Fig 3). Biopsy from perilesional skin revealed intracellular and fibrillar IF, whereas normal tissue showed only nonspecific fluorescence of the corneal layer. IHC staining of WNV NS1 protein revealed strong intracellular staining of keratinocytes in a lesional biopsy from the patient, which was absent in normal-appearing skin.

Fig 3.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for West Nile virus (WNV) NS1 glycoprotein. A, Biopsies were incubated with an antibody against WNV nonstructural glycoprotein NS1 (9NS1) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), which highlights nuclei. Biopsy from perilesional skin from a vesicle revealed a intracellular and fibrillar staining pattern from patient with WNV which was absent in normal-appearing skin obtained from a tissue repository. B, IHC staining of WNV NS1 protein revealed robust intracellular staining of keratinocytes in lesional biopsy from patient with WNV which was absent in normal-appearing skin obtained from a tissue repository.

Discussion

The transmission cycle of WNV involves infected mosquitoes as vectors and birds as primary hosts. Humans are dead-end hosts. The vast majority of WNV infections in humans are secondary to bites from infected mosquitoes. Outbreaks of WNV infection initially presented as mild febrile illness, with rare reports of neurologic symptoms.2 In 1996, a large WNV outbreak in Romania resulted in 352 cases of encephalitis and 17 deaths, and increased rates of neurologic disease have persisted.3 First detected in New York City in 1999, WNV has expanded across North America and has the greatest geographic spread among arboviruses.4

Approximately 75% to 80% of WNV infections in humans are asymptomatic, whereas 20% to 25% experience West Nile fever.5 Symptoms of West Nile fever are described as flu-like and typically include myalgia, headache, chills, vomiting, fatigue, and rash.5 Fever may be absent in up to 40% of symptomatic cases.6 Full recovery is typical, but fatigue and muscle weakness may persist.7 Less than 1% of WNV infections progress to severe neuroinvasive disease.5 The common manifestations of WNV neuroinvasive disease are encephalitis, meningitis, or acute flaccid paralysis. WNV neuroinvasive disease is associated with symptoms of headache, neck stiffness, seizures, tremors, paralysis, and confusion.5 Advanced age and immunosuppression are associated with increased risk of neuroinvasive disease.8

Suggestive clinical symptoms and confirmatory laboratory testing are necessary to diagnose WNV infection. Presentation of symptoms during mosquito season and travel to known areas of transmission should increase suspicion for WNV. Clinical symptoms and routine blood tests do not offer specific signs of WNV infection. Computed tomography imaging is often normal, but magnetic resonance imaging may show abnormalities in approximately one-third of WNV encephalitis cases. WNV infection is diagnosed by the presence of WNV-specific IgM antibodies in the serum or CSF. Detection of WNV IgM in the CSF indicates central nervous system involvement. CSF analysis may also show increased protein levels, normal glucose, and lymphocytic pleocytosis. Detection of WNV antigen in formalin-fixed central nervous system tissues by immunohistochemistry or reverse transcription-PCR has been reported as an adjunctive measure.9

Patients infected with WNV may present with a morbilliform eruption affecting the trunk and extremities, but reported rates are variable (25%-50%).6,10 A vesicular eruption associated with WNV has not been previously reported. WNV-associated rash commonly appears 3 to 7 days after symptom onset and typically lasts up to 7 days. Rash onset frequently coincides with defervescence. WNV-associated rashes may be associated with tingling, burning, and pruritus.11 Analysis of large-scale WNV outbreaks revealed an inverse association between rash and risk of encephalitis and death, after adjusting for age.12 The pathomechanisms underlying the improved prognosis of patients with WNV-associated rash is unclear, but its presence may represent a stronger host immune response against the virus. Rare histologic characterizations of WNV-associated rash have reported histopathologic features similar to those seen in viral exanthem, including superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.13 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time WNV proteins have been sought by IHC and/or IF on a WNV related rash, and these studies revealed strong WNV NS1 intracellular staining in keratinocytes by both IF and IHC. The presence of WNV NS1 protein in lesional skin raises the possibility that that the cutaneous eruptions in WNV infections may be mediated by an immune response against viral proteins present in the skin.

Most patients infected with WNV recover without intervention. Supportive treatment for headaches, nausea, and vomiting may be helpful in severe cases. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatment should be initiated in suspected cases of WNV meningoencephalitis, until other infectious causes have been excluded. Although corticosteroids, ribavirin, interferon alfa, and intravenous immunoglobulin have been used to treat neuroinvasive WNV, the efficacy of these treatments has not been confirmed in clinical trials.5 No vaccine candidates have reached the final stages of clinical development.14 Current prevention methods are largely focused on mosquito control through the reduction of breeding areas and insecticide treatments and reducing exposure to infected mosquitoes.

Other neurotropic flaviviruses continue to pose a significant global health threat because of their potential to cause serious central nervous system injury and long-standing morbidity (Table I).15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 In addition to WNV, flavivirus-induced neurotropic disease is caused by Japanese encephalitis virus and tick-borne encephalitis virus. In addition to the classically neurotropic flaviviruses, emerging neurotropic viruses such as Zika, St. Louis encephalitis, Powassan, Usutu, Ilheus, and Rocio viruses are being recognized for their epidemic potential.

Table I.

Flavivirus-induced neurotropic disease and possible cutaneous manifestations

| Flavivirus | Clinical presentation | Cutaneous presentation | Frequency of rash or cutaneous eruption | Insect vector | Geographic distribution | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese encephalitis virus | Fever, headache, acute encephalitis, aseptic encephalitis, seizures, acute flaccid paralysis | No known associated rash | Not applicable | Mosquito | Asia, Western Pacific, Australia | Solomon et al15 |

| West Nile virus | Fever, fatigue, memory impairment, weakness, neuroinvasive disease, meningitis, encephalitis, acute flaccid paralysis | Typically erythematous and morbilliform | 20%-50% | Mosquito | North America, Africa, Europe, Australia, Middle East | Watson et al10; Gorsche and Tilley16 |

| Zika virus | Fever, conjunctivitis, congenital microcephaly, Guillain-Barré syndrome, encephalitis, myelitis | Pruritic morbilliform eruption | 90% | Mosquito | South America, Central America, North America, Africa, Asia | de Oliveira et al17; Musso and Gubler18; Wolford and Schaefer19 |

| Tick-borne encephalitis | Fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, fatigue, malaise, anorexia, nausea, meningitis, encephalitis, myelitis | Rash uncommon, 1 reported case | Unknown | Tick | Europe, Asia | Charrel et al20; Mease et al21; Bogovic and Strle22 |

| Powassan virus | Fever, headache, vomiting, weakness, encephalitis, meningitis, confusion, loss of coordination, problems with speech, seizures | Rash, erythema migrans | 3 of 18 cases (17%), 6 of 14 cases (43%) | Tick | North America, Eastern Europe | Piantadosi et al23; El Khoury et al24; Kemenesi and Bányai25 |

| St. Louis Encephalitis virus | Often asymptomatic, fever, headache, meningitis, encephalitis | Rash uncommon, 1 reported case | Unknown | Mosquito | North America, South America | Brinker et al26; Venkat et al27; Simon et al28 |

| Usutu virus | Fever, myalgia, headache, arthralgia, asthenia, encephalitis, meningitis, acute flaccid paralysis | Rash, not specific, jaundice | 2 of 8 cases (25%) | Mosquito | Europe, Africa, Middle East | Pauli et al29; Nikolay et al30; Gaibani and Rossini31; Pacenti et al32 |

| Ilheus virus | Fever, encephalitis | Rash, not specified, vesicular rash (1 case) | Unknown | Mosquito | Central America, South America | Johnson et al33; Milhim et al34; Venegas et al35 |

| Rocio virus | Fever, encephalitis, headache, lower-extremity weakness, conjunctivitis, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, myalgia | No known associated rash | Not applicable | Mosquito | South America | Saivish et al36 |

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Acknowledgments

Control skin tissue specimens were provided by the Fresh and Archived and Skin Tissue Repository (FASTeR) in the Department of Dermatology. We thank M. Diamond (Washington University) for providing the NS1 (9NS1) antibody.

Footnotes

Funding source: Supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R21AI168698) to R.C.W.

Patient consent: The authors obtained written consent from patients for their photographs and medical information to be published in print and online and with the understanding that this information may be publicly available. Patient consent forms were not provided to the journal but are retained by the authors.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Lim P.Y., Behr M.J., Chadwick C.M., Shi P.Y., Bernard K.A. Keratinocytes are cell targets of West Nile virus in vivo. J Virol. 2011;85(10):5197–5201. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02692-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIntosh B., Jupp P., Dos Santos I., Meenehan G. Epidemics of West Nile and Sindbis viruses in South Africa with Culex (Culex) univittatus Theobald as vector. S Afr J Sci. 1976;72:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murgue B., Murri S., Triki H., Deubel V., Zeller H.G. West Nile in the Mediterranean basin: 1950-2000. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;951:117–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zehender G., Ebranati E., Bernini F., et al. Phylogeography and epidemiological history of West Nile virus genotype 1a in Europe and the Mediterranean basin. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11(3):646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sejvar J.J. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of West Nile virus infection. Viruses. 2014;6(2):606–623. doi: 10.3390/v6020606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou S., Foster G.A., Dodd R.Y., Petersen L.R., Stramer S.L. West Nile fever characteristics among viremic persons identified through blood donor screening. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(9):1354–1361. doi: 10.1086/656602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel H., Sander B., Nelder M.P. Long-term sequelae of West Nile virus-related illness: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(8):951–959. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes E.B., Komar N., Nasci R.S., Montgomery S.P., O’Leary D.R., Campbell G.L. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(8):1167–1173. doi: 10.3201/eid1108.050289a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatnagar J., Guarner J., Paddock C.D., et al. Detection of West Nile virus in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human tissues by RT-PCR: a useful adjunct to conventional tissue-based diagnostic methods. J Clin Virol. 2007;38(2):106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson J.T., Pertel P.E., Jones R.C., et al. Clinical characteristics and functional outcomes of West Nile Fever. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(5):360–365. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-5-200409070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson D.D., Gershman K., LeBailly A., Petersen L.R. Characteristics of the rash associated with West Nile virus fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(8):1204–1207. doi: 10.1086/444506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huhn G.D., Dworkin M.S. Rash as a prognostic factor in West Nile virus disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(3):388–389. doi: 10.1086/505606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson R.C., Horn K.B., Hoang M.P., Gottlieb E., Bennin B. Punctate exanthem of West Nile Virus infection: report of 3 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(5):820–823. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulbert S. West Nile virus vaccines – current situation and future directions. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(10):2337–2342. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1621149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solomon T., Dung N.M., Kneen R., Gainsborough M., Vaughn D.W., Khanh V.T. Japanese encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(4):405–415. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.4.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorsche R., Tilley P. The rash of West Nile virus infection. CMAJ. 2005;172(11):1440. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Oliveira W.K., Carmo E.H., Henriques C.M., et al. Zika virus infection and associated neurologic disorders in Brazil. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1591–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1608612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musso D., Gubler D.J. Zika virus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29(3):487–524. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00072-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolford R.W., Schaefer T.J. StatPearls; 2022. Zika Virus. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charrel R.N., Attoui H., Butenko A.M., et al. Tick-borne virus diseases of human interest in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(12):1040–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mease L.E., Maddox S.A., Noss M.R., Whitman S. Case report: tick-borne encephalitis virus infection in beneficiaries of the U.S. military healthcare system in southern Germany. MSMR. 2019;26(11):12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogovic P., Strle F. Tick-borne encephalitis: a review of epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3(5):430–441. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i5.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piantadosi A., Rubin D.B., McQuillen D.P., et al. Emerging cases of Powassan virus encephalitis in New England: clinical presentation, imaging, and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(6):707–713. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El Khoury M.Y., Camargo J.F., White J.L., et al. Potential role of deer tick virus in Powassan encephalitis cases in Lyme disease-endemic areas of New York, U.S.A. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(12):1926–1933. doi: 10.3201/eid1912.130903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kemenesi G., Bányai K. Tick-borne flaviviruses, with a focus on Powassan virus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32(1):e00106–e00117. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00106-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brinker K.R., Paulson G., Monath T.P., Wise G., Fass R.J. St Louis encephalitis in Ohio, September 1975: clinical and EEG studies in 16 cases. Arch Intern Med. 1979;139(5):561–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venkat H., Krow-Lucal E., Kretschmer M., et al. Comparison of characteristics of patients with West Nile virus or St. Louis encephalitis virus neuroinvasive disease during concurrent outbreaks, Maricopa County, Arizona, 2015. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2020;20(8):624–629. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2019.2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon LV, Kong EL, Graham C. St. Louis Encephalitis. StatPearls; 2022. [PubMed]

- 29.Pauli G., Bauerfeind U., Blümel J., et al. Usutu virus. Transfus Med Hemother. 2014;41(1):73–82. doi: 10.1159/000357106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikolay B., Diallo M., Boye C.S., Sall A.A. Usutu virus in Africa. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11(11):1417–1423. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaibani P., Rossini G. An overview of Usutu virus. Microbes Infect. 2017;19(7-8):382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pacenti M., Sinigaglia A., Martello T., et al. Clinical and virological findings in patients with Usutu virus infection, northern Italy, 2018. Euro Surveill. 2019;24(47) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.47.1900180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson B.W., Cruz C., Felices V., et al. Ilheus virus isolate from a human, Ecuador. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(6):956–958. doi: 10.3201/eid1306.070118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milhim B.H.G.A., Estofolete C.F., Rocha L.C.D., et al. Fatal outcome of Ilheus virus in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient diagnosed with encephalitis. Viruses. 2020;12(9):957. doi: 10.3390/v12090957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venegas E.A., Aguilar P.V., Cruz C., et al. Ilheus virus infection in human, Bolivia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(3):516–518. doi: 10.3201/eid1803.111486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saivish M.V., Gomes da Costa V., de Lima Menezes G., et al. Rocio virus: an updated view on an elusive Flavivirus. Viruses. 2021;13(11):2293. doi: 10.3390/v13112293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]